During World War II, the United States forcibly relocated and

incarcerated

Imprisonment or incarceration is the restraint of a person's liberty for any cause whatsoever, whether by authority of the government, or by a person acting without such authority. In the latter case it is considered "false imprisonment". Impris ...

about 120,000 people of

Japanese descent in ten

concentration camps

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploit ...

operated by the

War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was t ...

(WRA), mostly in the

western interior of the country. About two-thirds were

U.S. citizens. These actions were initiated by

Executive Order 9066

Executive Order 9066 was a President of the United States, United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. "This order authorized the fo ...

, issued by President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

on February 19, 1942, following the outbreak of war with the

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as┬Āthe Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From JapanŌĆōKor ...

in December 1941. About 127,000 Japanese Americans then lived in the

continental U.S., of which about 112,000 lived on the

West Coast. About 80,000 were ''

Nisei

is a Japanese language, Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the nikkeijin, ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants, or . The , or Second generation imm ...

'' ('second generation'; American-born Japanese with U.S. citizenship) and ''

Sansei

is a Japanese and North American English term used in parts of the world (mainly in South America and North America) to refer to the children of children born to ethnically Japanese emigrants (''Issei'') in a new country of residence, outside o ...

'' ('third generation', the children of ''Nisei''). The rest were ''

Issei

are Japanese immigrants to countries in North America and South America. The term is used mostly by ethnic Japanese. are born in Japan; their children born in the new country are (, "two", plus , "generation"); and their grandchildren are ...

'' ('first generation') immigrants born in Japan, who were ineligible for citizenship. In

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

, where more than 150,000 Japanese Americans comprised more than one-third of the

territory's population, only 1,200 to 1,800 were incarcerated.

Internment was intended to mitigate a security risk which Japanese Americans were believed to pose. The scale of the incarceration in proportion to the size of the Japanese American population far surpassed similar measures undertaken

against German and

Italian Americans

Italian Americans () are Americans who have full or partial Italians, Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeastern United States, Northeast and industrial Midwestern United States, Midwestern ...

who numbered in the millions and of whom some thousands were interned, most of these non-citizens. Following the executive order, the entire West Coast was designated a military exclusion area, and all Japanese Americans living there were taken to assembly centers before being sent to

concentration camp

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploitati ...

s in California, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, and Arkansas. Similar actions were taken

against individuals of Japanese descent in Canada. Internees were prohibited from taking more than they could carry into the camps, and many were forced to sell some or all of their property, including their homes and businesses. At the camps, which were surrounded by

barbed wire

Roll of modern agricultural barbed wire

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire or bob wire (in the Southern and Southwestern United States), is a type of steel fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the ...

fences and patrolled by armed guards, internees often lived in overcrowded barracks with minimal furnishing.

In its 1944 decision ''

Korematsu v. United States

''Korematsu v. United States'', 323 U.S. 214 (1944), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that upheld the internment of Japanese Americans from the West Coast Military Area during World War II. The decision has been widely ...

'', the

U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

upheld the constitutionality of the removals under the

Due Process Clause

A Due Process Clause is found in both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, which prohibit the deprivation of "life, liberty, or property" by the federal and state governments, respectively, without due proces ...

of the

Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifth Amendment (Amendment V) to the United States Constitution creates several constitutional rights, limiting governmental powers focusing on United States constitutional criminal procedure, criminal procedures. It was ratified, along with ...

. The Court limited its decision to the validity of the exclusion orders, avoiding the issue of the incarceration of U.S. citizens without due process, but ruled on the same day in ''

Ex parte Endo

''Ex parte Mitsuye Endo'', 323 U.S. 283 (1944), was a United States Supreme Court '' ex parte'' decision handed down on December 18, 1944, in which the Court unanimously ruled that the U.S. government could not continue to detain a citizen who ...

'' that a loyal citizen could not be detained, which began their release. On December 17, 1944, the exclusion orders were rescinded, and nine of the ten camps were shut down by the end of 1945. Japanese Americans were initially barred from U.S. military service, but by 1943, they were allowed to join, with 20,000 serving during the war. Over 4,000 students were allowed to leave the camps to attend college. Hospitals in the camps recorded 5,981 births and 1,862 deaths during incarceration.

In the 1970s, under mounting pressure from the

Japanese American Citizens League

The is an Asian American civil rights charity, headquartered in San Francisco, with regional chapters across the United States.

The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) describes itself as the oldest and largest Asian American civil rights ...

(JACL) and

redress organizations, President

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

appointed the

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians

The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) was a group of nine people appointed by the U.S. Congress in 1980 to conduct an official governmental study into the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Pro ...

(CWRIC) to investigate whether the internment had been justified. In 1983, the commission's report, ''Personal Justice Denied,'' found little evidence of Japanese disloyalty and concluded that internment had been the product of

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

. It recommended that the government pay

reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Reparation (theology), the theological concept of corrective response to God and the associated prayers for repairing the damages of sin

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for re ...

to the detainees. In 1988, President

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 ŌĆō June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

signed the

Civil Liberties Act of 1988

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (, title I, August 10, 1988, , et seq.) is a United States federal law that granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been wrongly interned by the United States government during World War II and to "di ...

, which officially apologized and authorized a payment of $20,000 () to each former detainee who was still alive when the act was passed. The legislation admitted that the government's actions were based on "race prejudice, war

hysteria

Hysteria is a term used to mean ungovernable emotional excess and can refer to a temporary state of mind or emotion. In the nineteenth century, female hysteria was considered a diagnosable physical illness in women. It is assumed that the bas ...

, and a failure of political leadership." By 1992, the U.S. government eventually disbursed more than $1.6 billion (equivalent to $ billion in ) in reparations to 82,219 Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated.

Background

Prior use of internment camps in the United States

The United States Government had previously employed civilian

internment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without Criminal charge, charges or Indictment, intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects ...

policies in a variety of circumstances. During the 1830s, civilians of the indigenous

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; , or ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern ...

nation were evicted from their homes and detained in "emigration depots" in

Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

and

Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

prior to the deportation to

Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

following the passage of the

Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States president Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, ...

in 1830. Similar internment policies were carried out by U.S. territorial authorities against the

Dakota

Dakota may refer to:

* Dakota people, a sub-tribe of the Sioux

** Dakota language, their language

Dakota may also refer to:

Places United States

* Dakota, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Dakota, Illinois, a town

* Dakota, Minnesota ...

and

Navajo

The Navajo or Din├® are an Indigenous people of the Southwestern United States. Their traditional language is Din├® bizaad, a Southern Athabascan language.

The states with the largest Din├® populations are Arizona (140,263) and New Mexico (1 ...

peoples during the

American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, was a conflict initially fought by European colonization of the Americas, European colonial empires, the United States, and briefly the Confederate States o ...

in the 1860s. In 1901, during the

PhilippineŌĆōAmerican War

The PhilippineŌĆōAmerican War, known alternatively as the Philippine Insurrection, FilipinoŌĆōAmerican War, or Tagalog Insurgency, emerged following the conclusion of the SpanishŌĆōAmerican War in December 1898 when the United States annexed th ...

, General

J. Franklin Bell

James Franklin Bell (January 9, 1856 ŌĆō January 8, 1919) was an officer in the United States Army who served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army from 1906 to 1910.

Bell was a Major general (United States), major general in the Regular ...

ordered the detainment of Filipino civilians in the provinces of

Batangas

Batangas, officially the Province of Batangas ( ), is a first class province of the Philippines located in the southwestern part of Luzon in the Calabarzon region. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 2,908,494 people, making ...

and

Laguna into U.S. Army-run concentration camps in order to prevent them from collaborating with Filipino General

Miguel Malvar

Miguel Malvar y Carpio (September 27, 1865 ŌĆō October 13, 1911) was a Filipino general who served during the Philippine Revolution and, subsequently, during the PhilippineŌĆōAmerican War. He assumed command of the Philippine revolutionary forc ...

's guerrillas; over 11,000 people died in the camps from malnutrition and disease.

After the United States entered

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 ŌĆō 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in 1917, roughly 6,300 German-born residents of the United States were arrested, with 2,048 of those residents being incarcerated at two U.S. Army bases, where they remained interned until 1920. However, these policies only targeted a small fraction of German-born Americans and did not apply to

German-American

German Americans (, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry.

According to the United States Census Bureau's figures from 2022, German Americans make up roughly 41 million people in the US, which is approximately 12% of the pop ...

U.S. citizens.

Japanese Americans before World War II

Due in large part to socio-political changes which stemmed from the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

ŌĆöand a

recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction that occurs when there is a period of broad decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be tr ...

which was caused by the abrupt

opening of Japan

]

The Perry Expedition (, , "Arrival of the Black Ships") was a diplomatic and military expedition in two separate voyages (1852ŌĆō1853 and 1854ŌĆō1855) to the Tokugawa shogunate () by warships of the United States Navy. The goals of this expedit ...

's economy to the

world economy

The world economy or global economy is the economy of all humans in the world, referring to the global economic system, which includes all economic activities conducted both within and between nations, including production (economics), producti ...

ŌĆöpeople emigrated from the

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as┬Āthe Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From JapanŌĆōKor ...

after 1868 in search of employment.

[Anderson, Emily.]

Immigration

" ''Densho Encyclopedia''. Retrieved August 14, 2014. From 1869 to 1924, approximately 200,000 Japanese immigrated to the islands of Hawaii, mostly laborers expecting to work on the

islands' sugar plantations. Some 180,000 went to the U.S. mainland, with the majority of them settling on the West Coast and establishing farms or small businesses.

Most arrived before 1908, when the

Gentlemen's Agreement

A gentlemen's agreement, or gentleman's agreement, is an informal and legally non-binding wikt:agreement, agreement between two or more parties. It is typically Oral contract, oral, but it may be written or simply understood as part of an unspok ...

between Japan and the United States banned the immigration of unskilled laborers. A loophole allowed the wives of men who were already living in the US to join their husbands. The practice of women marrying by proxy and immigrating to the U.S. resulted in a large increase in the number of "

picture bride

The term picture bride refers to the practice in the early 20th century of immigrant workers (chiefly Japanese, Okinawan, and Korean) in Hawaii and the West Coast of the United States and Canada, as well as Brazil selecting brides from their nat ...

s."

[Nakamura, Kelli Y.]

" ''Densho Encyclopedia''. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

As the Japanese American population continued to grow,

European Americans

European Americans are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes both people who descend from the first European settlers in the area of the present-day United States and people who descend from more recent European arrivals. Since th ...

who lived on the West Coast resisted the arrival of this ethnic group, fearing competition, and making the exaggerated claim that hordes of Asians would take over white-owned farmland and businesses. Groups such as the

Asiatic Exclusion League

The Asiatic Exclusion League (often abbreviated AEL) was an organization formed in the early 20th century in the United States and Canada that aimed to prevent immigration of people of Asian origin.

United States

In May 1905, a mass meeting was ...

, the

California Joint Immigration Committee

The California Joint Immigration Committee (CJIC) was a nativist lobbying organization active in the early to mid-twentieth century that advocated exclusion of Asian and Mexican immigrants to the United States.

Background

The CJIC was a suc ...

, and the

Native Sons of the Golden West

The Native Sons of the Golden West (NSGW) is a fraternity, fraternal service organization founded in the U.S. state of California in 1875, dedicated to historic preservation and documentation of the state's historic structures and places, the pla ...

organized in response to the rise of this "

Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror, the Yellow Menace, and the Yellow Specter) is a Racism, racist color terminology for race, color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East Asia, East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the ...

." They successfully lobbied to restrict the property and citizenship rights of Japanese immigrants, just as similar groups had previously organized against Chinese immigrants.

[Anderson, Emily.]

Anti-Japanese exclusion movement

" ''Densho Encyclopedia''. Retrieved August 14, 2014. Beginning in the late 19th century, several laws and treaties which attempted to slow immigration from Japan were introduced. The

Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or JohnsonŌĆōReed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from every count ...

, which followed the example of the 1882

Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was a United States Code, United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law made exceptions for travelers an ...

, effectively banned all immigration from Japan and other "undesirable" Asian countries.

The 1924 ban on immigration produced unusually well-defined generational groups within the Japanese American community. The ''

Issei

are Japanese immigrants to countries in North America and South America. The term is used mostly by ethnic Japanese. are born in Japan; their children born in the new country are (, "two", plus , "generation"); and their grandchildren are ...

'' were exclusively those Japanese who had immigrated before 1924; some of them desired to return to their homeland. Because no more immigrants were permitted, all Japanese Americans who were born after 1924 were, by definition, born in the U.S. and by law, they were automatically considered U.S. citizens. The members of this ''

Nisei

is a Japanese language, Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the nikkeijin, ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants, or . The , or Second generation imm ...

'' generation constituted a cohort which was distinct from the cohort which their parents belonged to. In addition to the usual generational differences, Issei men were typically ten to fifteen years older than their wives, making them significantly older than the younger children in their often large families.

U.S. law prohibited Japanese immigrants from becoming naturalized citizens, making them dependent on their children whenever they rented or purchased property. Communication between English-speaking children and parents who mostly or completely spoke in Japanese was often difficult. A significant number of older Nisei, many of whom were born prior to the immigration ban, had married and already started families of their own by the time the US entered World War II.

Despite racist legislation which prevented Issei from becoming naturalized citizens (or

owning property, voting, or running for political office), these Japanese immigrants established communities in their new hometowns. Japanese Americans contributed to the agriculture of California and other Western states, by introducing irrigation methods which enabled them to cultivate fruits, vegetables, and flowers on previously inhospitable land.

In both rural and urban areas, ''kenjinkai,'' community groups for immigrants from the same

Japanese prefecture, and ''

fujinkai,'' Buddhist women's associations, organized community events and did charitable work, provided loans and financial assistance and built

Japanese language schools for their children. Excluded from setting up shop in white neighborhoods,

nikkei-owned small businesses thrived in the ''

Nihonmachi

is a term used to refer to historical Japanese communities in Southeast and East Asia. The term has come to also be applied to several modern-day communities, though most of these are called simply " Japantown", in imitation of the common term " ...

,'' or Japantowns of urban centers, such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and

Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

.

In the 1930s, the

Office of Naval Intelligence

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) is the military intelligence agency of the United States Navy. Established in 1882 primarily to advance the Navy's modernization efforts, it is the oldest member of the U.S. Intelligence Community and serv ...

(ONI), concerned as a result of Imperial Japan's rising military power in Asia, began to conduct surveillance in Japanese American communities in Hawaii. Starting in 1936, at the behest of President Roosevelt, the ONI began to compile a "special list of those Japanese Americans who would be the first to be placed in a

concentration camp

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploitati ...

in the event of trouble" between Japan and the United States. In 1939, again by order of the President, the ONI,

Military Intelligence Division

The Military Intelligence Division was the military intelligence branch of the United States Army and United States Department of War from May 1917 (as the Military Intelligence Section, then Military Intelligence Branch in February 1918, then ...

, and

FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

began working together to compile a larger

Custodial Detention Index.

[Kashima, Tetsuden.]

Custodial detention / A-B-C list

" ''Densho Encyclopedia''. Retrieved August 14, 2014. Early in 1941, Roosevelt commissioned

Curtis Munson to conduct an investigation on Japanese Americans living on the West Coast and in Hawaii. After working with FBI and ONI officials and interviewing Japanese Americans and those familiar with them, Munson determined that the "Japanese problem" was nonexistent. His final report to the President, submitted November 7, 1941, "certified a remarkable, even extraordinary degree of loyalty among this generally suspect ethnic group." A subsequent report by

Kenneth Ringle (ONI), delivered to the President in January 1942, also found little evidence to support claims of Japanese American disloyalty and argued against mass incarceration.

[Niiya, Brian.]

Kenneth Ringle

" ''Densho Encyclopedia''. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

Roosevelt's racial attitudes toward Japanese Americans

Roosevelt's decision to intern Japanese Americans was consistent with Roosevelt's long-time racial views. During the 1920s, for example, he had written articles in the

Macon Telegraph

''The Telegraph'', frequently called The Macon Telegraph, is the primary print news organ in Middle Georgia. It is the third-largest newspaper in the State of Georgia (after the ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' and ''Augusta Chronicle''). Founde ...

opposing white-Japanese intermarriage for fostering "the mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood" and praising California's ban on land ownership by the first-generation Japanese. In 1936, while president, he privately wrote that, regarding contacts between Japanese sailors and the local Japanese American population in the event of war, "every

Japanese citizen or non-citizen on the Island of Oahu who meets these Japanese ships or has any connection with their officers or men should be secretly but definitely identified and his or her name placed on a special list of those who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp."

[Beito, p. 165-173.]

After Pearl Harbor

In the weeks immediately following the

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

the president disregarded the advice of advisors, notably

John Franklin Carter

John Franklin Carter a.k.a. Jay Franklin a.k.a. Diplomat a.k.a. Unofficial Observer (1897ŌĆō1967) was an American journalist, columnist, biographer and novelist. He notably wrote the syndicated column, "We the People", under his pen name Jay ...

, who urged him to speak out in defense of the rights of Japanese Americans.

The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, led military and political leaders to suspect that

Imperial Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as┬Āthe Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From JapanŌĆōKor ...

was preparing a

full-scale invasion of the United States West Coast. Due to Japan's

rapid military conquest of a large portion of Asia and the Pacific including a small portion of the U.S. West Coast (i.e.,

Aleutian Islands Campaign

The Aleutian Islands campaign () was a military campaign fought between 3 June 1942 and 15 August 1943 on and around the Aleutian Islands in the American theater (World War II), American Theater of World War II during the Pacific War. It was t ...

) between 1937 and 1942, some Americans feared that its military forces were unstoppable.

American public opinion initially stood by the large population of Japanese Americans living on the West Coast, with the ''

Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'' characterizing them as "good Americans, born and educated as such." Many Americans believed that their loyalty to the United States was unquestionable. Though some in the administration (including Attorney General

Francis Biddle

Francis Beverley Biddle (May 9, 1886 ŌĆō October 4, 1968) was an American lawyer and judge who was the United States Attorney General during World War II. He also served as the primary American judge during Nuremberg trials following World War I ...

and FBI Director

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 ŌĆō May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

) dismissed all rumors of Japanese American espionage on behalf of the Japanese war effort, pressure mounted upon the administration as the tide of public opinion turned against Japanese Americans.

A survey of the Office of Facts and Figures on February 4 (two weeks prior to the president's order) reported that a majority of Americans expressed satisfaction with existing governmental controls on Japanese Americans. Moreover, in his autobiography in 1962, Biddle, who opposed incarceration, downplayed the influence of public opinion in prompting the president's decision. He even considered it doubtful "whether, political and special group press aside, public opinion even on the West Coast supported evacuation." Support for harsher measures toward Japanese Americans increased over time, however, in part since Roosevelt did little to use his office to calm attitudes. According to a March 1942 poll conducted by the

American Institute of Public Opinion

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

, after incarceration was becoming inevitable, 93% of Americans supported the relocation of Japanese non-citizens from the

Pacific Coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas North America

Countries on the western side of North America have a Pacific coast as their western or south-western border. One of th ...

while only 1% opposed it. According to the same poll, 59% supported the relocation of Japanese people who were born in the country and were United States citizens, while 25% opposed it.

The incarceration and imprisonment measures taken against Japanese Americans after the attack falls into a broader trend of anti-Japanese attitudes on the West Coast of the United States. To this end, preparations had already been made in the collection of names of Japanese American individuals and organizations, along with other foreign nationals such as Germans and Italians, that were to be removed from society in the event of a conflict. The December 7th attack on Pearl Harbor, bringing the United States into the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 ŌĆō 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, enabled the implementation of the dedicated government policy of incarceration, with the action and methodology having been extensively prepared before war broke out despite multiple reports that had been consulted by Roosevelt expressing the notion that Japanese Americans posed little threat.

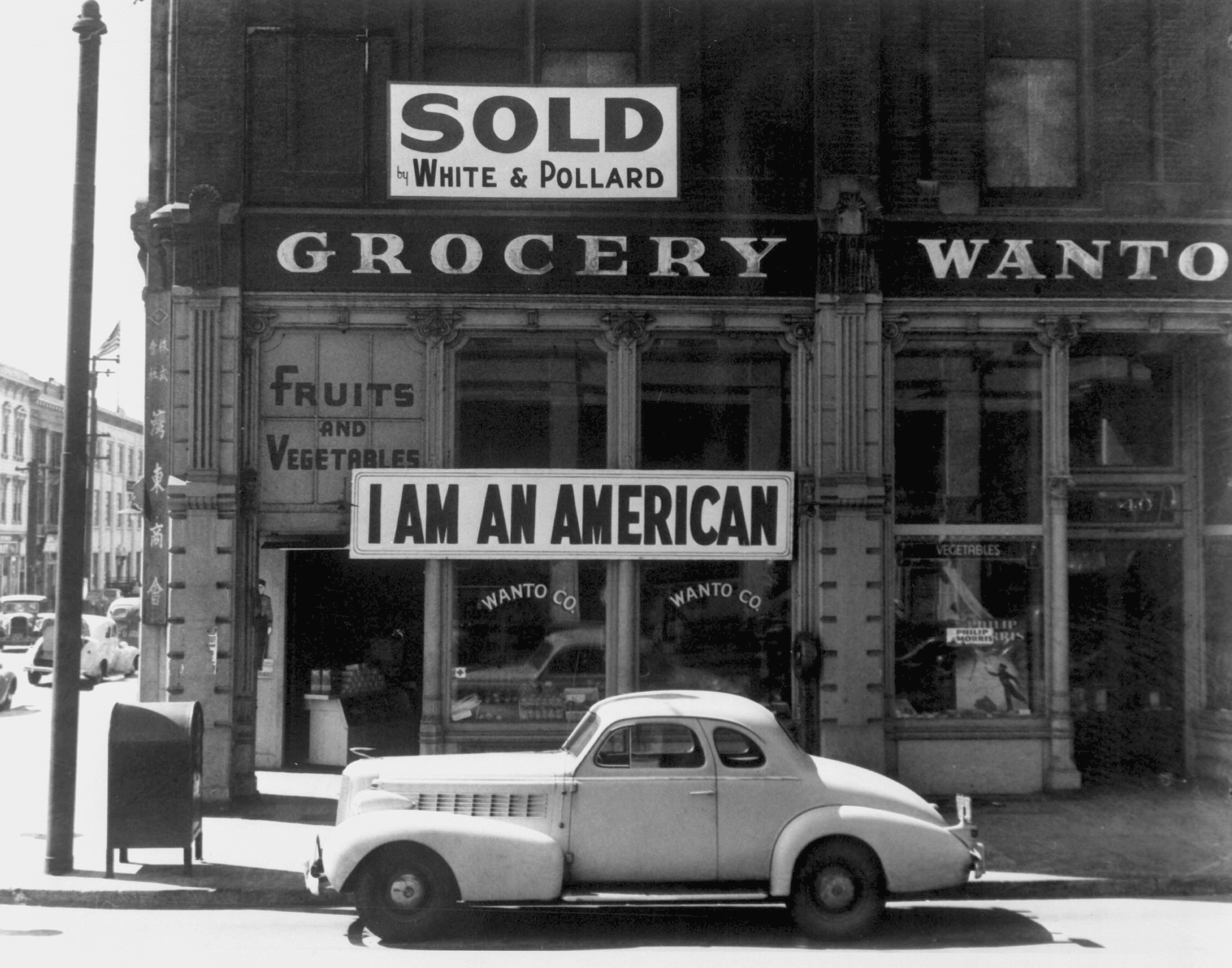

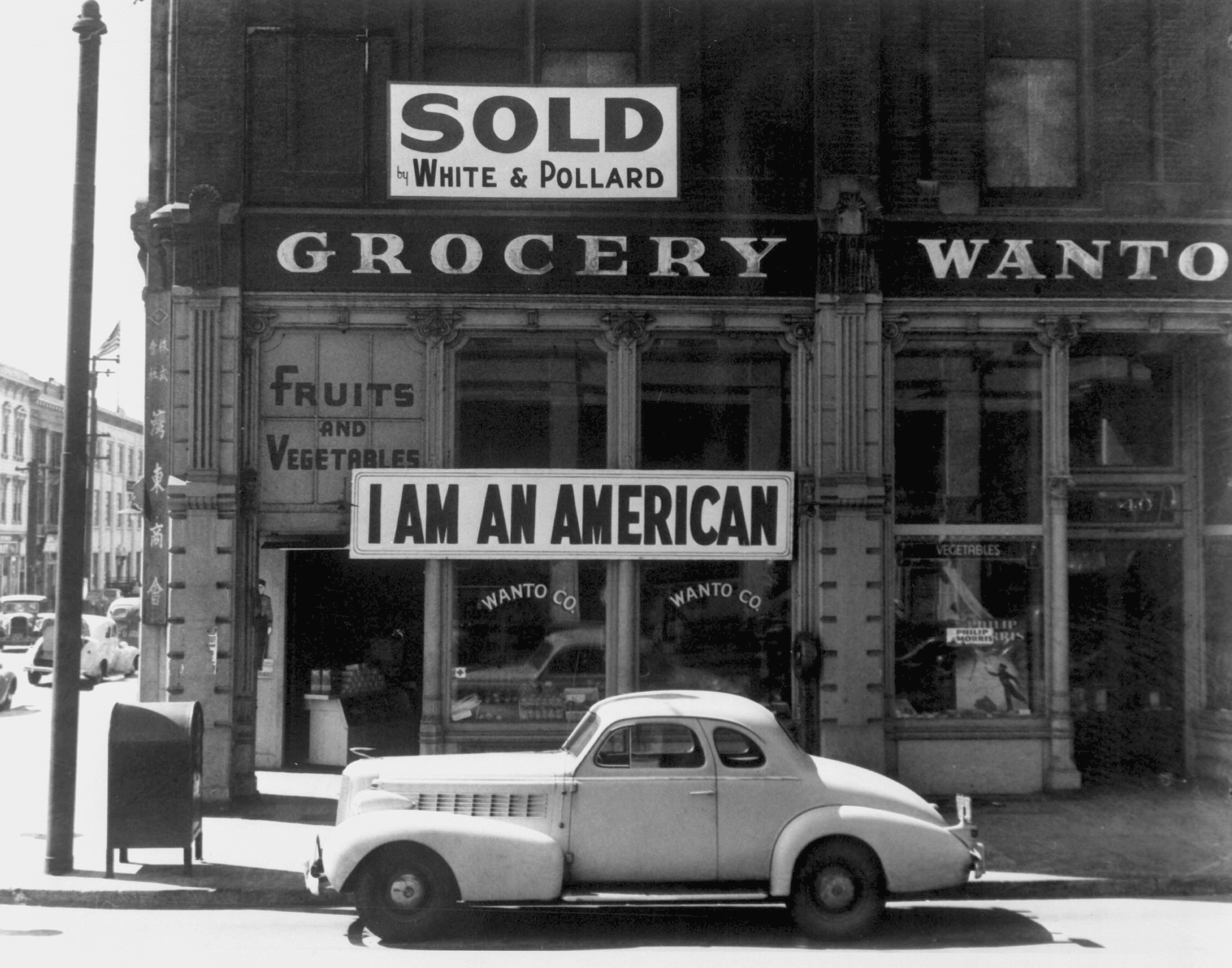

Additionally, the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II led to severe economic consequences. Numerous Japanese Americans had to leave their homes, businesses, and possessions since they were relocated to the internment camps. This also led to the collapse of many family-owned businesses, real estate, and their savings since they had been escorted to the camps. "Camp residents lost some $400 million in property during their incarceration. Congress provided $38 million in reparations in 1948 and, forty years later, paid an additional $20,000 to each surviving individual who had been detained in the camps". Additionally, Japanese American farmers suffered greatly due to their forced relocation. In 1942, the managing secretary of the Western Growers Protective Association reported that the removal of Japanese Americans led to significant profits for growers and shippers. These losses were tragic, which ended up affecting a multitude of Japanese Americans and resulted in many losses of properties, businesses, and more. This also resulted in limited compensation, and far less than what they had originally lost. The economic outcomes of the Japanese imprisonments were disastrous and serve as a reminder of the lasting cost of cultural discrimination.

Niihau incident

Although the impact on US authorities is controversial, the

Niihau incident

The Ni╩╗ihau incident occurred on December 7ŌĆō13, 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service pilot crash-landed on the Territory of Hawaii, Hawaiian island of Niihau, Ni╩╗ihau after participating in the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Impe ...

immediately followed the attack on Pearl Harbor, when Ishimatsu Shintani, an Issei, and Yoshio Harada, a Nisei, and his Issei wife Irene Harada on the island of Ni'ihau violently freed a downed and captured Japanese naval airman, attacking their fellow Ni'ihau islanders in the process.

Roberts Commission

Several concerns over the loyalty of ethnic Japanese seemed to stem from

racial prejudice

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race or ethnicity over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination ...

rather than any evidence of malfeasance. The

Roberts Commission

The Roberts Commission is one of two presidentially-appointed commissions. One related to the circumstances of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and another related to the protection of cultural resources during and after World War II. Both were ...

report, which investigated the Pearl Harbor attack, was released on January 25 and accused persons of Japanese ancestry of espionage leading up to the attack.

[ Although the report's key finding was that General ]Walter Short

Walter Campbell Short (March 30, 1880 – September 3, 1949) was a lieutenant general (temporary rank) and major general of the United States Army and the U.S. military commander responsible for the defense of U.S. military installations in ...

and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel had been derelict in their duties during the attack on Pearl Harbor, one passage made vague reference to "Japanese consular agents and other... persons having no open relations with the Japanese foreign service" transmitting information to Japan. It was unlikely that these "spies" were Japanese American, as Japanese intelligence agents were distrustful of their American counterparts and preferred to recruit "white persons and Negroes." However, despite the fact that the report made no mention of Americans of Japanese ancestry, national and West Coast media nevertheless used the report to vilify Japanese Americans and inflame public opinion against them.[Niiya, Brian.]

" ''Densho Encyclopedia''. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

Questioning loyalty

Major Karl Bendetsen and Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt

John Lesesne DeWitt (9 January 1880 ŌĆō 20 June 1962) was a four-star general in the United States Army. He was best known for overseeing the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanes ...

, head of the Western Defense Command

Western Defense Command (WDC) was established on 17 March 1941 as the command formation of the United States Army responsible for coordinating the defense of the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast region of the United States during Wo ...

, questioned Japanese American loyalty. DeWitt said:

He further stated in a conversation with California's governor, Culbert L. Olson:

"A Jap's a Jap"

DeWitt, who administered the incarceration program, repeatedly told newspapers that "A Jap

''Jap'' is an English abbreviation of the word " Japanese". In the United States, some Japanese Americans have come to find the term offensive because of the internment they suffered during World War II. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, ''Jap ...

's a Jap" and testified to Congress:

DeWitt also sought approval to conduct search and seizure operations which were aimed at preventing alien Japanese from making radio transmissions to Japanese ships.[Andrew E. Taslitz, "Stories of Fourth Amendment Disrespect: From Elian to the Internment," 70 ''Fordham Law Review''. 2257, 2306ŌĆō07 (2002).] The Justice Department declined, stating that there was no probable cause

In United States criminal law, probable cause is the legal standard by which police authorities have reason to obtain a warrant for the arrest of a suspected criminal and for a court's issuing of a search warrant. One definition of the standar ...

to support DeWitt's assertion, as the FBI concluded that there was no security threat.Emperor of Japan

The emperor of Japan is the hereditary monarch and head of state of Japan. The emperor is defined by the Constitution of Japan as the symbol of the Japanese state and the unity of the Japanese people, his position deriving from "the will of ...

; the manifesto contended that Japanese language schools were bastions of racism which advanced doctrines of Japanese racial superiority.American Legion

The American Legion, commonly known as the Legion, is an Voluntary association, organization of United States, U.S. war veterans headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. It comprises U.S. state, state, Territories of the United States, U.S. terr ...

, which in January demanded that all Japanese with dual citizenship

Multiple citizenship (or multiple nationality) is a person's legal status in which a person is at the same time recognized by more than one sovereign state, country under its nationality law, nationality and citizenship law as a national or cit ...

be placed in concentration camps.Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 ŌĆō July 9, 1974) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 30th governor of California from 1943 to 1953 and as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presid ...

, the Attorney General of California

The attorney general of California is the state attorney general of the government of California. The officer must ensure that "the laws of the state are uniformly and adequately enforced" ( Constitution of California, Article V, Section 13). ...

(and a future Chief Justice of the United States), had begun his efforts to persuade the federal government to remove all people of Japanese ethnicity from the West Coast.

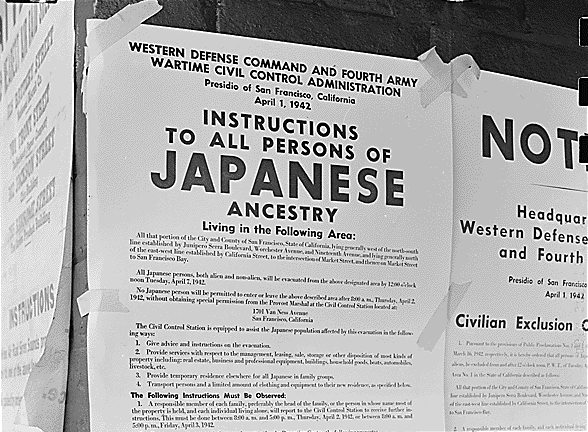

Presidential Proclamations

Upon the bombing of Pearl Harbor and pursuant to the Alien Enemies Act, Presidential Proclamations 2525, 2526 and 2527 were issued designating Japanese, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

and Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

nationals as enemy aliens. Information gathered by US officials over the previous decade was used to locate and incarcerate thousands of Japanese American community leaders in the days immediately following Pearl Harbor (see section elsewhere in this article " Other concentration camps"). In Hawaii, under the auspices of martial law, both "enemy aliens" and citizens of Japanese and "German" descent were arrested and interned (incarcerated if they were a US citizen).

Presidential Proclamation 2537 (codified a

7 Fed. Reg. 329

was issued on January 14, 1942, requiring "alien enemies" to obtain a certificate of identification and carry it "at all times".Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 ŌĆō October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and Demo ...

with replying. A conference on February 17 of Secretary Stimson with assistant secretary John J. McCloy

John Jay McCloy (March 31, 1895 ŌĆō March 11, 1989) was an American lawyer, diplomat, banker, and high-ranking bureaucrat. He served as United States Assistant Secretary of War, Assistant Secretary of War during World War II under Henry L. Stims ...

, Provost Marshal General Allen W. Gullion, Deputy chief of Army Ground Forces

The Army Ground Forces were one of the three autonomous components of the Army of the United States during World War II, the others being the Army Air Forces and Army Service Forces. Throughout their existence, Army Ground Forces were the la ...

Mark W. Clark

Mark Wayne Clark (1 May 1896 ŌĆō 17 April 1984) was a United States Army officer who fought in World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. He was the youngest four-star general in the U.S. Army during World War II.

During World War I, he wa ...

, and Colonel Bendetsen decided that General DeWitt should be directed to commence evacuations "to the extent he deemed necessary" to protect vital installations. Throughout the war, interned Japanese Americans protested against their treatment and insisted that they be recognized as loyal Americans. Many sought to demonstrate their patriotism by trying to enlist in the armed forces. Although early in the war Japanese Americans were barred from military service, by 1943 the army had begun actively recruiting Nisei to join new all-Japanese American units.

Development

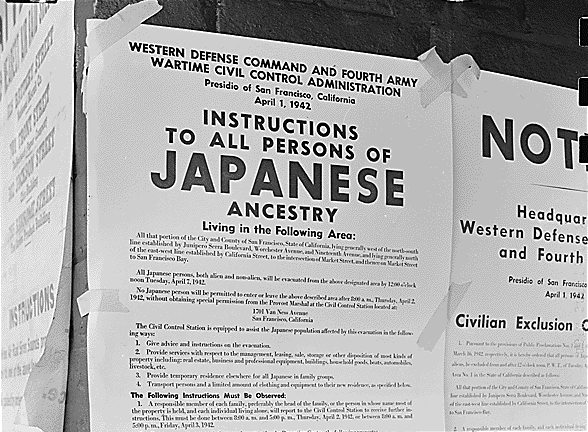

Executive Order 9066 and related actions

Executive Order 9066, signed by Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, authorized military commanders to designate "military areas" at their discretion, "from which any or all persons may be excluded." These "exclusion zones," unlike the "alien enemy" roundups, were applicable to anyone that an authorized military commander might choose, whether citizen or non-citizen. Eventually such zones would include parts of both the East and West Coasts, totaling about 1/3 of the country by area. Unlike the subsequent deportation and incarceration programs that would come to be applied to large numbers of Japanese Americans, detentions and restrictions directly under this Individual Exclusion Program were placed primarily on individuals of German or Italian ancestry, including American citizens.Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

and the military exclusion zones from all of California and parts of Oregon, Washington, and Arizona, with the exception of those inmates who were being held in government camps. On March 2, 1942, General John DeWitt, commanding general of the Western Defense Command, publicly announced the creation of two military restricted zones.

On March 2, 1942, General John DeWitt, commanding general of the Western Defense Command, publicly announced the creation of two military restricted zones.[ Japanese Americans were free to go anywhere outside of the exclusion zone or inside Area 2, with arrangements and costs of relocation to be borne by the individuals. The policy was short-lived; DeWitt issued another proclamation on March 27 that prohibited Japanese Americans from leaving Area 1.]Minidoka War Relocation Center

Minidoka National Historic Site is a National Historic Site in the western United States. It commemorates the more than 13,000 Japanese Americans who were imprisoned at the Minidoka War Relocation Center during the Second World War. in Southern Idaho

Southern Idaho is a generic geographical term roughly analogous with the areas of the U.S. state of Idaho located in the Mountain Time Zone

The Mountain Time Zone of North America keeps time by subtracting seven hours from Coordinated Unive ...

.Bainbridge Island, Washington

Bainbridge Island is a city and island in Kitsap County, Washington, United States. It is located in Puget Sound. The population was 24,825 at the 2020 census, making Bainbridge Island the second largest city in Kitsap County.

The island is s ...

six days to prepare for their "evacuation" directly to Manzanar.Ralph Lawrence Carr

Ralph Lawrence Carr (December 11, 1887September 22, 1950) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 29th Governor of Colorado from 1939 to 1943. During World War II, he defended the rights of American citizens of Japanese desce ...

was the only elected official to publicly denounce the incarceration of American citizens (an act that cost his reelection, but gained him the gratitude of the Japanese American community, such that a statue of him was erected in the Denver

Denver ( ) is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Consolidated city and county, consolidated city and county, the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Colorado, most populous city of the U.S. state of ...

Japantown's Sakura Square).

Support and opposition

Non-military advocates of exclusion, removal, and detention

The deportation and incarceration of Japanese Americans was popular among many white farmers who resented the Japanese American farmers. "White American farmers admitted that their self-interest required the removal of the Japanese."

The deportation and incarceration of Japanese Americans was popular among many white farmers who resented the Japanese American farmers. "White American farmers admitted that their self-interest required the removal of the Japanese."The Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine published six times a year. It was published weekly from 1897 until 1963, and then every other week until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely circulated and influ ...

'' in 1942:

The Leadership of the Japanese American Citizens League

The is an Asian American civil rights charity, headquartered in San Francisco, with regional chapters across the United States.

The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) describes itself as the oldest and largest Asian American civil rights ...

did not question the constitutionality of the exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Instead, arguing it would better serve the community to follow government orders without protest, the organization advised the approximately 120,000 affected to go peacefully.Roberts Commission

The Roberts Commission is one of two presidentially-appointed commissions. One related to the circumstances of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and another related to the protection of cultural resources during and after World War II. Both were ...

Report, prepared at President Franklin D. Roosevelt's request, has been cited as an example of the fear and prejudice informing the thinking behind the incarceration program.Hearst newspapers Hearst may refer to:

Places

* Hearst, former name of Hacienda, California, United States

* Hearst, Ontario, town in Northern Ontario, Canada

* Hearst, California, an unincorporated community in Mendocino County, United States

* Hearst Island, a ...

, reflected the growing public sentiment that was fueled by this report:

Other California newspapers also embraced this view. According to a ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'' editorial,

U.S. Representative Leland Ford ( R- CA) of Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

joined the bandwagon, who demanded that "all Japanese, whether citizens or not, be placed in nland

NLand Surf Park is an inland surfing destination near Austin, Texas, located ten minutes from AustinŌĆōBergstrom International Airport, Austin-Bergstrom International Airport at 4836 East Highway 71, Del Valle, Texas 78617. The park offers surfi ...

concentration camps."Bracero Program

The Bracero Program (from the Spanish term ''bracero'' , meaning " manual laborer" or "one who works using his arms") was a temporary labor initiative between the United States and Mexico that allowed Mexican workers to be employed in the U.S. ...

. Many Japanese detainees were temporarily released from their camps ŌĆō for instance, to harvest Western beet crops ŌĆō to address this wartime labor shortage.

Non-military advocates who opposed exclusion, removal, and detention

Like many white American farmers, the white businessmen of Hawaii had their own motives for determining how to deal with the Japanese Americans, but they opposed their incarceration. Instead, these individuals gained the passage of legislation which enabled them to retain the freedom of the nearly 150,000 Japanese Americans who would have otherwise been sent to concentration camps which were located in Hawaii. As a result, only 1,200[Ogawa, Dennis M. and Fox, Jr., Evarts C. ''Japanese Americans, from Relocation to Redress''. 1991, p. 135.] to 1,800 Japanese Americans in Hawaii were incarcerated.[Takaki, Ronald T. "A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America". Boston: Little, Brown 1993. Print, p. 379.] The Japanese represented "over 90 percent of the carpenters, nearly all of the transportation workers, and a significant portion of the agricultural laborers" on the islands.Delos Carleton Emmons

Delos Carleton Emmons (January 17, 1889 ŌĆō October 3, 1965) was a lieutenant general in the United States Army. He was the military governor of Hawaii in the aftermath of the Attack on Pearl Harbor and administered the replacement of normal Feder ...

, the military governor of Hawaii, also argued that Japanese labor was "'absolutely essential' for rebuilding the defenses destroyed at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

."Nisei

is a Japanese language, Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the nikkeijin, ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants, or . The , or Second generation imm ...

. He turned against the Japanese by mid-February 1942, days before the executive order was issued, but he later regretted this decision and he attempted to atone for it for the rest of his life.Orange County Register

''The Orange County Register'' is a paid daily List of newspapers in California, newspaper published in California. The ''Register'', published in Orange County, California, is owned by the private equity firm Alden Global Capital via its Digit ...

'', argued during the war that the incarceration was unethical and unconstitutional:

It would seem that convicting people of disloyalty to our country without having specific evidence against them is too foreign to our way of life and too close akin to the kind of government we are fighting.... We must realize, as Henry Emerson Fosdick so wisely said, 'Liberty is always dangerous, but it is the safest thing we have.'

Members of some Christian religious groups (such as Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

), particularly those who had formerly sent missionaries to Japan, were among opponents of the incarceration policy. Some Baptist and Methodist churches, among others, also organized relief efforts to the camps, supplying inmates with supplies and information.

Statement of military necessity as a justification of incarceration

Niihau Incident

The Niihau Incident occurred in December 1941, just after the Imperial Japanese Navy's attack on Pearl Harbor. The Imperial Japanese Navy had designated the Hawaiian island of Niihau

Niihau (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ), anglicized as Niihau ( ), is the seventh largest island in Hawaii and the westernmost of the main islands. It is southwest of Kauai, Kauai across the Channels of the Hawaiian Islands#Kaulakahi Channel, Ka ...

as an uninhabited island for damaged aircraft to land and await rescue. Three Japanese Americans on Niihau assisted a Japanese pilot, Shigenori Nishikaichi, who crashed there. Despite the incident, the Territorial Governor of Hawaii Joseph Poindexter

Joseph Boyd Poindexter (April 14, 1869 – December 3, 1951) was the eighth Territorial Governor of Hawaii and served from 1934 to 1942.

Early life

Joseph Boyd Poindexter was born in Canyon City, Oregon to Thomas W. and Margaret (Pipkin) P ...

rejected calls for the mass incarceration of the Japanese Americans living there.

Cryptography

In ''Magic: The Untold Story of U.S. Intelligence and the Evacuation of Japanese Residents from the West Coast During World War II'', David Lowman, a former National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is an intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the director of national intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collection, and proces ...

operative, argues that Magic

Magic or magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

** ''Magick'' (with ''-ck'') can specifically refer to ceremonial magic

* Magic (illusion), also known as sta ...

(the code-name for American code-breaking efforts) intercepts posed "frightening specter of massive espionage nets", thus justifying incarceration. Lowman contended that incarceration served to ensure the secrecy of U.S. code-breaking efforts, because effective prosecution of Japanese Americans might necessitate disclosure of secret information. If U.S. code-breaking technology was revealed in the context of trials of individual spies, the Japanese Imperial Navy would change its codes, thus undermining U.S. strategic wartime advantage.

Some scholars have criticized or dismissed Lowman's reasoning that "disloyalty" among some individual Japanese Americans could legitimize "incarcerating 120,000 people, including infants, the elderly, and the mentally ill". Lowman's reading of the contents of the ''Magic'' cables has also been challenged, as some scholars contend that the cables demonstrate that Japanese Americans were not heeding the overtures of Imperial Japan to spy against the United States. According to one critic, Lowman's book has long since been "refuted and discredited".

The controversial conclusions drawn by Lowman were defended by conservative commentator Michelle Malkin

Michelle Malkin (; Maglalang; born October 20, 1970) is an American conservative political commentator. She was a Fox News contributor and in May 2020 joined Newsmax TV. Malkin has written seven books and founded the conservative commentary ...

in her book '' In Defense of Internment: The Case for 'Racial Profiling' in World War II and the War on Terror'' (2004). Malkin's defense of Japanese incarceration was due in part to reaction to what she describes as the "constant alarmism from Bush-bashers who argue that every counter-terror measure in America is tantamount to the internment". She criticized academia's treatment of the subject, and suggested that academics critical of Japanese incarceration had ulterior motives. Her book was widely criticized, particularly with regard to her reading of the Magic cables. Daniel Pipes

Daniel Pipes (born September 9, 1949) is an American former professor and commentator on foreign policy and the Middle East. He is the president of the Middle East Forum, and publisher of its ''Middle East Quarterly'' journal. His writing focus ...

, also drawing on Lowman, has defended Malkin, and said that Japanese American incarceration was "a good idea" which offers "lessons for today".

Black and Jewish reactions to the Japanese American incarceration

The American public overwhelmingly approved of the Japanese American incarceration measures and as a result, they were seldom opposed, particularly by members of minority groups who felt that they were also being chastised within America. Morton Grodzins writes that "The sentiment against the Japanese was not far removed from (and it was interchangeable with) sentiments against Negroes and Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

."

Occasionally, the NAACP and the NCJW spoke out but few were more vocal in opposition to incarceration than George S. Schuyler, an associate editor of the Pittsburgh Courier

The ''Pittsburgh Courier'' was an African American weekly newspaper published in Pittsburgh from 1907 until October 22, 1966. By the 1930s, the ''Courier'' was one of the leading black newspapers in the United States.

It was acquired in 1965 by ...

, perhaps the leading black newspaper in the U.S., who was increasingly critical of the domestic and foreign policy of the Roosevelt administration. He dismissed accusations that Japanese Americans presented any genuine national security threat. Schuyler warned African Americans that "if the Government can do this to American citizens of Japanese ancestry, then it can do this to American citizens of ANY ancestry...Their fight is our fight."

The shared experience of racial discrimination has led some modern Japanese American leaders to come out in support of HR 40, a bill which calls for reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Reparation (theology), the theological concept of corrective response to God and the associated prayers for repairing the damages of sin

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for re ...

to be paid to African-Americans because they are affected by slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and subsequent discrimination. Cheryl Greenberg adds "Not all Americans endorsed such racism. Two similarly oppressed groups, African Americans and Jewish Americans

American Jews (; ) or Jewish Americans are Americans, American citizens who are Jews, Jewish, whether by Jewish culture, culture, ethnicity, or Judaism, religion. According to a 2020 poll conducted by Pew Research, approximately two thirds of Am ...

, had already organized to fight discrimination and bigotry." However, due to the justification of concentration camps by the US government, "few seemed tactile to endorse the evacuation; most did not even discuss it." Greenberg argues that at the time, the incarceration was not discussed because the government's rhetoric hid the motivations for it behind a guise of military necessity, and a fear of seeming "un-American" led to the silencing of most civil rights groups until years into the policy.

United States District Court's opinions

A letter by DeWitt and Bendetsen expressing racist bias against Japanese Americans was circulated and then hastily redacted in 1943ŌĆō1944. DeWitt's final report stated that, because of their race, it was impossible to determine the loyalty of Japanese Americans, thus necessitating incarceration.

A letter by DeWitt and Bendetsen expressing racist bias against Japanese Americans was circulated and then hastily redacted in 1943ŌĆō1944. DeWitt's final report stated that, because of their race, it was impossible to determine the loyalty of Japanese Americans, thus necessitating incarceration. In 1980, a copy of the original ''Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast ŌĆō 1942'' was found in the

In 1980, a copy of the original ''Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast ŌĆō 1942'' was found in the National Archives

National archives are the archives of a country. The concept evolved in various nations at the dawn of modernity based on the impact of nationalism upon bureaucratic processes of paperwork retention.

Conceptual development

From the Middle Ages i ...

, along with notes which show the numerous differences which exist between the original version and the redacted version. This earlier, racist and inflammatory version, as well as the FBI and Office of Naval Intelligence

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) is the military intelligence agency of the United States Navy. Established in 1882 primarily to advance the Navy's modernization efforts, it is the oldest member of the U.S. Intelligence Community and serv ...

(ONI) reports, led to the ''coram nobis

A writ of ''coram nobis'' (also writ of error ''coram nobis'', writ of ''coram vobis'', or writ of error ''coram vobis'') is a legal order allowing a court to correct its original judgment upon discovery of a fundamental error that did not appear ...

'' retrials which overturned the convictions of Fred Korematsu

was an American civil rights activist who resisted the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Shortly after the Imperial Japanese Navy launched its attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Ord ...

, Gordon Hirabayashi

was an American sociologist, best known for his principled resistance to the Japanese American internment during World War II, and the court case which bears his name, ''Hirabayashi v. United States''.

Early life

Hirabayashi was born in Seattle ...

and Minoru Yasui

was an American lawyer from Oregon. Born in Hood River, Oregon, he earned both an undergraduate degree and his law degree at the University of Oregon. He was one of the few Japanese Americans after the bombing of Pearl Harbor who fought laws th ...

on all charges related to their refusal to submit to exclusion and incarceration.Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

, which proved that there was no military necessity for the exclusion and incarceration of Japanese Americans. In the words of Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice, is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

officials writing during the war, the justifications were based on "willful historical inaccuracies and intentional falsehoods".

The Ringle Report

In May 2011, U.S. Solicitor General Neal Katyal, after a year of investigation, found Charles Fahy

Charles Fahy (August 27, 1892 ŌĆō September 17, 1979) was an American lawyer and judge who served as the 26th Solicitor General of the United States from 1941 to 1945 and later served as a United States circuit judge of the United States Court o ...

had intentionally withheld ''The Ringle Report'' drafted by the Office of Naval Intelligence, in order to justify the Roosevelt administration's actions in the cases of '' Hirabayashi v. United States'' and ''Korematsu v. United States

''Korematsu v. United States'', 323 U.S. 214 (1944), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that upheld the internment of Japanese Americans from the West Coast Military Area during World War II. The decision has been widely ...

''. The report would have undermined the administration's position of the military necessity for such action, as it concluded that most Japanese Americans were not a national security threat, and that allegations of communication espionage had been found to be without basis by the FBI and Federal Communications Commission

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is an independent agency of the United States government that regulates communications by radio, television, wire, internet, wi-fi, satellite, and cable across the United States. The FCC maintains j ...

.

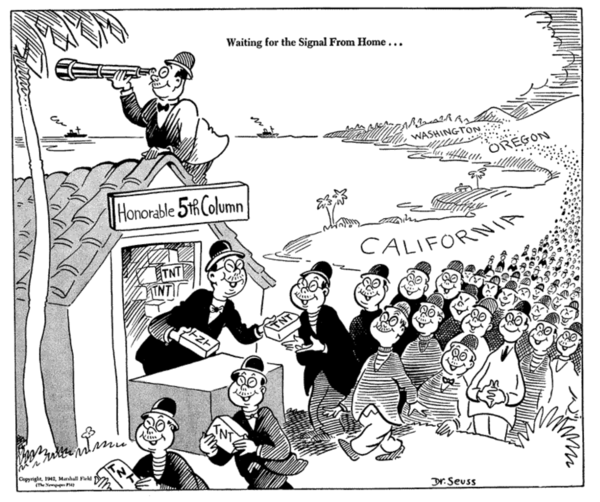

Newspaper editorials

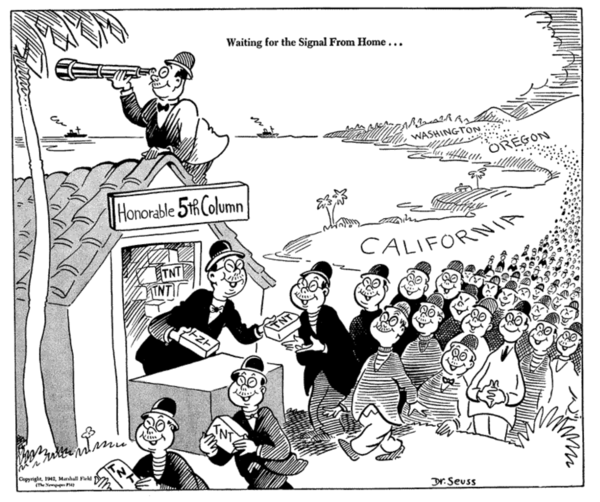

Editorials from major newspapers at the time were generally supportive of the incarceration of the Japanese by the United States.

A ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'' editorial dated February 19, 1942, stated that:

Since Dec. 7 there has existed an obvious menace to the safety of this region in the presence of potential saboteurs and fifth columnists close to oil refineries and storage tanks, airplane factories, Army posts, Navy facilities, ports and communications systems. Under normal sensible procedure not one day would have elapsed after Pearl Harbor before the government had proceeded to round up and send to interior points all Japanese aliens and their immediate descendants for classification and possible incarceration.

This dealt with aliens, and the unassimilated. Going even farther, an ''Atlanta Constitution

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' (''AJC'') is an American daily newspaper based in Atlanta metropolitan area, metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Jo ...

'' editorial dated February 20, 1942, stated that:

The time to stop taking chances with Japanese aliens and Japanese-Americans has come. . . . While Americans have an inate 'sic''distaste for stringent measures, every one must realize this is a total war, that there are no Americans running loose in Japan or Germany or Italy and there is absolutely no sense in this country running even the slightest risk of a major disaster from enemy groups within the nation.

A ''Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'' editorial dated February 22, 1942, stated that:

There is but one way in which to regard the Presidential order empowering the Army to establish "military areas" from which citizens or aliens may be excluded. That is to accept the order as a necessary accompaniment of total defense.

A ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'' editorial dated February 28, 1942, stated that:

As to a considerable number of Japanese, no matter where born, there is unfortunately no doubt whatever. They are for Japan; they will aid Japan in every way possible by espionage, sabotage and other activity; and they need to be restrained for the safety of California and the United States. And since there is no sure test for loyalty to the United States, all must be restrained. Those truly loyal will understand and make no objection.

A ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'' editorial dated December 8, 1942, stated that:

The Japs in these centers in the United States have been afforded the very best of treatment, together with food and living quarters far better than many of them ever knew before, and a minimum amount of restraint. They have been as well fed as the Army and as well as or better housed. . . . The American people can go without milk and butter, but the Japs will be supplied.

A ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'' editorial dated April 22, 1943, stated that:

As a race, the Japanese have made for themselves a record for conscienceless treachery unsurpassed in history. Whatever small theoretical advantages there might be in releasing those under restraint in this country would be enormously outweighed by the risks involved.

Facilities

The

The Works Projects Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to c ...

(WPA) played a key role in the construction and staffing of the camps in the initial period. From March to

the end of November 1942, that agency spent $4.47 million on removal

and incarceration, which was even more than the Army devoted to that purpose during that period. The WPA was instrumental in creating such features of the camps as guard towers and barbed wire fencing.[Beito, p. 182-183.]

The government operated several different types of camps holding Japanese Americans. The best known facilities were the military-run Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) ''Assembly Centers'' and the civilian-run War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was t ...

(WRA) ''Relocation Centers,'' which are generally (but unofficially) referred to as "internment camps". Many employees of the WRA had earlier worked for the WPA during the initial period of removal and construction.[ page 13] Another argument for using the label "concentration camps" is that President Roosevelt himself applied that terminology to them, including at a press conference in November 1944.

The Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice, is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

(DOJ) operated camps officially called ''Internment Camps'', which were used to detain those suspected of crimes or of "enemy sympathies". The government also operated camps for a number of German Americans

German Americans (, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry.

According to the United States Census Bureau's figures from 2022, German Americans make up roughly 41 million people in the US, which is approximately 12% of the pop ...

and Italian Americans

Italian Americans () are Americans who have full or partial Italians, Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeastern United States, Northeast and industrial Midwestern United States, Midwestern ...

, who sometimes were assigned to share facilities with the Japanese Americans. The WCCA and WRA facilities were the largest and the most public. The WCCA Assembly Centers were temporary facilities that were first set up in horse racing tracks, fairgrounds, and other large public meeting places to assemble and organize inmates before they were transported to WRA Relocation Centers by truck, bus, or train. The WRA Relocation Centers were semi-permanent camps that housed persons removed from the exclusion zone after March 1942, or until they were able to relocate elsewhere in the United States outside the exclusion zone.

DOJ and Army incarceration camps

Eight U.S. Department of Justice Camps (in Texas, Idaho, North Dakota, New Mexico, and Montana) held Japanese Americans, primarily non-citizens and their families.Immigration and Naturalization Service

The United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) was a United States federal government agency under the United States Department of Labor from 1933 to 1940 and under the United States Department of Justice from 1940 to 2003.

Refe ...

, under the umbrella of the DOJ, and guarded by Border Patrol

A border guard of a country is a national security agency that ensures border security. Some of the national border guard agencies also perform coast guard (as in Germany, Italy or Ukraine) and rescue service duties.

Name and uniform

In diffe ...

agents rather than military police. The population of these camps included approximately 3,800 of the 5,500 Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...