Stephen Crane on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stephen Crane (November 1, 1871 – June 5, 1900) was an American poet, novelist, and short story writer. Prolific throughout his short life, he wrote notable works in the Realist tradition as well as early examples of American Naturalism and

After two years, Crane left Pennington for Claverack College, a quasi-military school. He later looked back on his time at Claverack as "the happiest period of my life although I was not aware of it." A classmate remembered him as a highly literate but erratic student, lucky to pass examinations in math and science, and yet "far in advance of his fellow students in his knowledge of History and Literature", his favorite subjects.Davis, p. 24 While he held an impressive record on the drill field and baseball diamond, Crane generally did not excel in the classroom. Not having a middle name, as was customary among other students, he took to signing his name "Stephen T. Crane" in order "to win recognition as a regular fellow". Crane was seen as friendly, but also moody and rebellious. He sometimes skipped class to play baseball, a game in which he starred as

After two years, Crane left Pennington for Claverack College, a quasi-military school. He later looked back on his time at Claverack as "the happiest period of my life although I was not aware of it." A classmate remembered him as a highly literate but erratic student, lucky to pass examinations in math and science, and yet "far in advance of his fellow students in his knowledge of History and Literature", his favorite subjects.Davis, p. 24 While he held an impressive record on the drill field and baseball diamond, Crane generally did not excel in the classroom. Not having a middle name, as was customary among other students, he took to signing his name "Stephen T. Crane" in order "to win recognition as a regular fellow". Crane was seen as friendly, but also moody and rebellious. He sometimes skipped class to play baseball, a game in which he starred as  In mid-1888, Crane became his brother Townley's assistant at a New Jersey shore news bureau, working there every summer until 1892. Crane's first publication under his byline was an article on the explorer Henry M. Stanley's quest to find the Scottish missionary David Livingstone in Africa. It appeared in the February 1890 Claverack College ''Vidette''. Within a few months, Crane was persuaded by his family to forgo a military career and transfer to

In mid-1888, Crane became his brother Townley's assistant at a New Jersey shore news bureau, working there every summer until 1892. Crane's first publication under his byline was an article on the explorer Henry M. Stanley's quest to find the Scottish missionary David Livingstone in Africa. It appeared in the February 1890 Claverack College ''Vidette''. Within a few months, Crane was persuaded by his family to forgo a military career and transfer to

During the early part of his career, Crane was promoted by Elbert Hubbard, who commented on his works and featured them in his popular small magazine, ''The Philistine''. Crane was the guest of honor at the first annual meeting of the Society of Philistines in 1895 when he was relatively unknown. Although Crane was severely teased during the meeting, they remained friendly and their association proved mutually beneficial. Seven of Crane’s poems and a short story were published in the first issue of ''The Roycroft Quarterly'' (another of Hubbard’s magazines) which commemorated the event. In a concluding note, Hubbard commented, "to the mass, he is known, if at all, only as the author of ''The Black Riders'' in verse, and of the ''Red Badge of Courage'' in prose; efforts, both, that challenge study and baffle understanding rather than soothe superficiality or pander to the wishes of mental indolence."

Sources report that following an encounter with a male prostitute that spring, Crane began a novel on the subject entitled '' Flowers of Asphalt,'' which he later abandoned. The manuscript has never been recovered.

After discovering that ''McClure's'' could not afford to pay him, Crane took his war novel to Irving Bacheller of the Bacheller-Johnson Newspaper Syndicate, which agreed to publish ''The Red Badge of Courage'' in serial form. From December 3 to 9, ''The Red Badge of Courage'' was published in some half-dozen newspapers in the United States. Although it was greatly cut for syndication, Bacheller attested to its causing a stir, saying "its quality asimmediately felt and recognized." The lead editorial in the '' Philadelphia Press'' of December 7 said that Crane "is a new name now and unknown, but everybody will be talking about him if he goes on as he has begun".

During the early part of his career, Crane was promoted by Elbert Hubbard, who commented on his works and featured them in his popular small magazine, ''The Philistine''. Crane was the guest of honor at the first annual meeting of the Society of Philistines in 1895 when he was relatively unknown. Although Crane was severely teased during the meeting, they remained friendly and their association proved mutually beneficial. Seven of Crane’s poems and a short story were published in the first issue of ''The Roycroft Quarterly'' (another of Hubbard’s magazines) which commemorated the event. In a concluding note, Hubbard commented, "to the mass, he is known, if at all, only as the author of ''The Black Riders'' in verse, and of the ''Red Badge of Courage'' in prose; efforts, both, that challenge study and baffle understanding rather than soothe superficiality or pander to the wishes of mental indolence."

Sources report that following an encounter with a male prostitute that spring, Crane began a novel on the subject entitled '' Flowers of Asphalt,'' which he later abandoned. The manuscript has never been recovered.

After discovering that ''McClure's'' could not afford to pay him, Crane took his war novel to Irving Bacheller of the Bacheller-Johnson Newspaper Syndicate, which agreed to publish ''The Red Badge of Courage'' in serial form. From December 3 to 9, ''The Red Badge of Courage'' was published in some half-dozen newspapers in the United States. Although it was greatly cut for syndication, Bacheller attested to its causing a stir, saying "its quality asimmediately felt and recognized." The lead editorial in the '' Philadelphia Press'' of December 7 said that Crane "is a new name now and unknown, but everybody will be talking about him if he goes on as he has begun".

At the end of January 1895, Crane left on what he called "a very long and circuitous newspaper trip" to the west. While writing feature articles for the Bacheller syndicate, he traveled to

At the end of January 1895, Crane left on what he called "a very long and circuitous newspaper trip" to the west. While writing feature articles for the Bacheller syndicate, he traveled to

The ship sailed from Jacksonville with 27 or 28 men and supplies and ammunition for the Cuban rebels. On the

The ship sailed from Jacksonville with 27 or 28 men and supplies and ammunition for the Cuban rebels. On the

On March 20, they sailed first to England, where Crane was warmly received. They arrived in

On March 20, they sailed first to England, where Crane was warmly received. They arrived in

In December, the couple held an elaborate Christmas party at Brede, attended by Conrad,

In December, the couple held an elaborate Christmas party at Brede, attended by Conrad,

Written thirty years after the end of the Civil War and before Crane had any experience of battle, ''The Red Badge of Courage'' was innovative stylistically as well as psychologically. Often described as a

Written thirty years after the end of the Civil War and before Crane had any experience of battle, ''The Red Badge of Courage'' was innovative stylistically as well as psychologically. Often described as a

Crane wrote many different types of fictional pieces while indiscriminately applying to them terms such as "story", "tale" and "sketch". For this reason, critics have found clear-cut classification of Crane's work problematic. While "The Open Boat" and "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky" are often considered short stories, others are variously identified.

In an 1896 interview with Herbert P. Williams, a reporter for the ''

Crane wrote many different types of fictional pieces while indiscriminately applying to them terms such as "story", "tale" and "sketch". For this reason, critics have found clear-cut classification of Crane's work problematic. While "The Open Boat" and "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky" are often considered short stories, others are variously identified.

In an 1896 interview with Herbert P. Williams, a reporter for the ''

In four years, Crane published five novels, two volumes of poetry, three short story collections, two books of war stories, and numerous works of short fiction and reporting. Today he is mainly remembered for ''The Red Badge of Courage''. The novel has been adapted several times for the screen, including

In four years, Crane published five novels, two volumes of poetry, three short story collections, two books of war stories, and numerous works of short fiction and reporting. Today he is mainly remembered for ''The Red Badge of Courage''. The novel has been adapted several times for the screen, including

, ''Columbia University Record'', Vol. 21, No. 9, November 3, 1995, accessed July 5, 2014 Columbia University had an exhibit: '' 'The Tall Swift Shadow of a Ship at Night': Stephen and Cora Crane'', November 2, 1995 through February 16, 1996, about the lives of the couple, featuring letters and other documents and memorabilia.

''Great Battles of the World''

(1901) * ''The O'Ruddy'' (1903)

"Stephen Crane's Refrain."

ESQ, Vol. 54. 33–53. *Cazemajou, Jean. 1969. ''Stephen Crane''. Minneapolis:

"Stephen Crane and the Philistine."

American Literature, Vol. 15, No 3. 279287 Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. *Gibson, Donald B. 1988. ''The Red Badge of Courage: Redefining the Hero''. Boston: Twayne Publishers. . *Gibson, Donald B. 1968. ''The Fiction of Stephen Crane''. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. *Gullason, Thomas A. 1961. "Thematic Patterns in Stephen Crane's Early Novels". ''Nineteenth-Century Fiction'', Vol. 16, No. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. *Hoffman, Daniel. 1967. "Crane and Poetic Tradition". ''Stephen Crane: A Collection of Critical Essays''. Ed. Maurice Bassan. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc. *Hubbard, Elbert. 1896

Some Historical Documents

Roycroft Quarterly, Vol. 1, No 1. 3946 East Aurora, New York: Roycroft Printing Shop. *Katz, Joseph. 1972. "Introduction". ''The Complete Poems of Stephen Crane''. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. . *Knapp, Bettina L. 1987. ''Stephen Crane''. New York: Ungar Publishing Co. *Kwiat, Joseph J. 1987. "Stephen Crane, Literary-Reporter: Commonplace Experience and Artistic Transcendence". ''Journal of Modern Literature'', Vol. 8, No. 1. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. *Linson, Corwin K. 1958. ''My Stephen Crane''. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. *Nagel, James. 1980. ''Stephen Crane and Literary Impressionism''. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. . *Perosa, Sergio. “Naturalism and Impressionism in Stephen Crane's Fiction,” ''Stephen Crane: A Collection of Critical Essays'', ed. Maurice Bassan (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall 1966). *Robertson, Michael. 1997. ''Stephen Crane, Journalism, and the Making of Modern American Literature''. New York:

Finding aid to the Stephen Crane papers at Columbia University

* Stephen Crane's collected journalism a

The Stephen Crane Society

''The Red Badge of Courage'' Site

by Rick Burton

SS ''Commodore'' Wreck Site

*

Articles in ''Western American Literature'' on Stephen Crane

Article on Stephen Crane in May 1895 edition of ''The Bookman'' (New York)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Crane, Stephen 1871 births 1900 deaths 19th-century American journalists 19th-century American male writers 19th-century American novelists 19th-century American poets 19th-century American short story writers 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis American male journalists American male novelists American male poets American male short story writers American people of English descent American realism novelists American war correspondents American war novelists Burials at Evergreen Cemetery (Hillside, New Jersey) Claverack College alumni Crane family (New Jersey) Hearst Communications people Novelists from New Jersey The Pennington School alumni Shipwreck survivors Syracuse Orangemen baseball players Tuberculosis deaths in Germany War correspondents of the Spanish–American War Writers from Newark, New Jersey Delta Upsilon members

Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by visible brush strokes, open Composition (visual arts), composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage ...

. He is recognized by modern critics as one of the most innovative writers of his generation.

The ninth surviving child of Methodist parents, Crane began writing at the age of four and had several articles published by 16. Having little interest in university studies though he was active in a fraternity, he left Syracuse University

Syracuse University (informally 'Cuse or SU) is a Private university, private research university in Syracuse, New York, United States. It was established in 1870 with roots in the Methodist Episcopal Church but has been nonsectarian since 1920 ...

in 1891 to work as a reporter and writer. Crane's first novel

A debut novel is the first novel a novelist publishes. Debut novels are often the author's first opportunity to make an impact on the publishing industry, and thus the success or failure of a debut novel can affect the ability of the author to p ...

was the 1893 Bowery

The Bowery () is a street and neighbourhood, neighborhood in Lower Manhattan in New York City, New York. The street runs from Chatham Square at Park Row (Manhattan), Park Row, Worth Street, and Mott Street in the south to Cooper Square at 4th ...

tale '' Maggie: A Girl of the Streets'', generally considered by critics to be the first work of American literary Naturalism. He won international acclaim for his Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

novel '' The Red Badge of Courage'' (1895), considered a masterpiece by critics and writers.

In 1896, Crane endured a highly publicized scandal after appearing as a witness in the trial of a suspected prostitute

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-pe ...

, an acquaintance named Dora Clark. Late that year, he accepted an offer to travel to Cuba as a war correspondent

A war correspondent is a journalist who covers stories first-hand from a war, war zone.

War correspondence stands as one of journalism's most important and impactful forms. War correspondents operate in the most conflict-ridden parts of the wor ...

. As he waited in Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville ( ) is the most populous city proper in the U.S. state of Florida, located on the Atlantic coast of North Florida, northeastern Florida. It is the county seat of Duval County, Florida, Duval County, with which the City of Jacksonv ...

, for passage, he met Cora Taylor, with whom he began a lasting relationship. En route to Cuba, Crane's vessel, the SS ''Commodore'', sank off the coast of Florida, leaving him adrift for 30 hours in a dinghy

A dinghy is a type of small boat, often carried or Towing, towed by a Watercraft, larger vessel for use as a Ship's tender, tender. Utility dinghies are usually rowboats or have an outboard motor. Some are rigged for sailing but they diffe ...

. Crane described the ordeal in " The Open Boat". During the final years of his life, he covered conflicts in Greece (accompanied by Cora, recognized as the first woman war correspondent) and later lived in England with her. He was befriended by writers such as Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

and H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

. Plagued by financial difficulties and ill health, Crane died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

in a Black Forest

The Black Forest ( ) is a large forested mountain range in the States of Germany, state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is th ...

sanatorium in Germany at the age of 28.

At the time of his death, Crane was considered an important figure in American literature. After he was nearly forgotten for two decades, critics revived interest in his life and work. Crane's writing is characterized by vivid intensity, distinctive dialect

A dialect is a Variety (linguistics), variety of language spoken by a particular group of people. This may include dominant and standard language, standardized varieties as well as Vernacular language, vernacular, unwritten, or non-standardize ...

s, and irony

Irony, in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what, on the surface, appears to be the case with what is actually or expected to be the case. Originally a rhetorical device and literary technique, in modernity, modern times irony has a ...

. Common themes involve fear, spiritual crises and social isolation. Although recognized primarily for ''The Red Badge of Courage'', which has become an American classic, Crane is also known for his poetry, journalism, and short stories such as "The Open Boat", " The Blue Hotel", " The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky", and '' The Monster''. His writing made a deep impression on 20th-century writers, most prominent among them Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

, and is thought to have inspired the Modernists and the Imagists

Imagism was a movement in early-20th-century poetry that favored precision of imagery and clear, sharp language. It is considered to be the first organized literary modernism, modernist literary movement in the English language. Imagism has bee ...

.

Biography

Early years

Stephen Crane was born on November 1, 1871, inNewark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, most populous City (New Jersey), city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, the county seat of Essex County, New Jersey, Essex County, and a principal city of the New York metropolitan area. ...

, to Jonathan Townley Crane, a minister in the Methodist Episcopal church, and Mary Helen Peck Crane, daughter of a clergyman, George Peck. He was the fourteenth and last child born to the couple. At 45, Helen Crane had suffered the deaths of her previous four children in infancy. Nicknamed "Stevie" by the family, he joined eight surviving brothers and sisters—Mary Helen, George Peck, Jonathan Townley, William Howe, Agnes Elizabeth, Edmund Byran, Wilbur Fiske, and Luther.Davis, p. 10

The Cranes were descended from Jaspar Crane, a founder of New Haven Colony

New Haven Colony was an English colony from 1638 to 1664 that included settlements on the north shore of Long Island Sound, with outposts in modern-day New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. The colony joined Connecticut Colony in 16 ...

, who had migrated there from England in 1639. Stephen was named for a putative founder of Elizabethtown, New Jersey, who had, according to family tradition, come from England or Wales in 1665, as well as his great-great-grandfather Stephen Crane, a Revolutionary War patriot who served as New Jersey delegate to the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates of twelve of the Thirteen Colonies held from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia at the beginning of the American Revolution. The meeting was organized b ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

. Crane later wrote that his father "was a great, fine, simple mind", who had written numerous tracts on theology. Although his mother was a popular spokeswoman for the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and a highly religious woman, Crane wrote that he did not believe "she was as narrow as most of her friends or family." The young Stephen was raised primarily by his sister Agnes, 15 years his senior.Wertheim (1994), p. 1 The family moved to Port Jervis, New York, in 1876, where Dr. Crane became the pastor of Drew Methodist Church, a position that he retained until his death.

As a child, Crane was often sickly and afflicted by constant cold

Cold is the presence of low temperature, especially in the atmosphere. In common usage, cold is often a subjectivity, subjective perception. A lower bound to temperature is absolute zero, defined as 0.00K on the Kelvin scale, an absolute t ...

s. When the boy was almost two, his father wrote in his diary that his youngest son became "so sick that we are anxious about him." Despite his fragile nature, Crane was an intelligent child who taught himself to read before the age of four. At the age of three, while imitating his brother Townley's writing, he asked his mother, "how do you spell ''O''?" In December 1879, Crane wrote a poem about wanting a dog for Christmas. Entitled "I'd Rather Have –", it is his first surviving poem. Stephen was not regularly enrolled in school until January 1880, but he had no difficulty in completing two grades in six weeks. Recalling this feat, he wrote that it "sounds like the lie of a fond mother at a teaparty, but I do remember that I got ahead very fast and that father was very pleased with me."

Dr. Crane died on February 16, 1880, at the age of 60; Stephen was eight years old. Some 1,400 people attended his funeral, more than double the size of his congregation. After her husband's death, Mrs. Crane moved to Roseville, near Newark, leaving Stephen in the care of his older brother Edmund, with whom the young boy lived with cousins in Sussex County. He next lived with his brother William, a lawyer, in Port Jervis for several years.

His older sister Helen took him to Asbury Park

Asbury Park () is a beachfront city located on the Jersey Shore in Monmouth County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is part of the New York metropolitan area. As of the 2020 United States census, the city's population was 15,188, a dec ...

to be with their brother Townley and his wife, Fannie. Townley was a professional journalist; he headed the Long Branch department of both the ''New-York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' (from 1914: ''New York Tribune'') was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s ...

'' and the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

, and also served as editor of the ''Asbury Park Shore Press''. Agnes, another Crane sister, joined the siblings in New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

. She took a position at Asbury Park's intermediate school and moved in with Helen to care for the young Stephen.

Within a couple of years, the Crane family suffered more losses. First, Townley and his wife lost their two young children. His wife Fannie died of Bright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine. It was frequently accompanied ...

in November 1883. Agnes Crane became ill and died on June 10, 1884, of meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, intense headache, vomiting and neck stiffness and occasion ...

at the age of 28.

Schooling

Crane wrote his first known story, "Uncle Jake and the Bell Handle", when he was 14. In late 1885, he enrolled at Pennington Seminary, a ministry-focused coeducational boarding school north of Trenton. His father had been principal there from 1849 to 1858. Soon after her youngest son left for school, Mrs. Crane began suffering what the ''Asbury Park Shore Press'' reported as "a temporary aberration of the mind." She had apparently recovered by early 1886, but later that year, her son, 23-year-old Luther Crane, died after falling in front of an oncoming train while working as a railroad flagman. It was the fourth death in six years among Stephen's immediate family. After two years, Crane left Pennington for Claverack College, a quasi-military school. He later looked back on his time at Claverack as "the happiest period of my life although I was not aware of it." A classmate remembered him as a highly literate but erratic student, lucky to pass examinations in math and science, and yet "far in advance of his fellow students in his knowledge of History and Literature", his favorite subjects.Davis, p. 24 While he held an impressive record on the drill field and baseball diamond, Crane generally did not excel in the classroom. Not having a middle name, as was customary among other students, he took to signing his name "Stephen T. Crane" in order "to win recognition as a regular fellow". Crane was seen as friendly, but also moody and rebellious. He sometimes skipped class to play baseball, a game in which he starred as

After two years, Crane left Pennington for Claverack College, a quasi-military school. He later looked back on his time at Claverack as "the happiest period of my life although I was not aware of it." A classmate remembered him as a highly literate but erratic student, lucky to pass examinations in math and science, and yet "far in advance of his fellow students in his knowledge of History and Literature", his favorite subjects.Davis, p. 24 While he held an impressive record on the drill field and baseball diamond, Crane generally did not excel in the classroom. Not having a middle name, as was customary among other students, he took to signing his name "Stephen T. Crane" in order "to win recognition as a regular fellow". Crane was seen as friendly, but also moody and rebellious. He sometimes skipped class to play baseball, a game in which he starred as catcher

Catcher is a position in baseball and softball. When a batter takes their turn to hit, the catcher crouches behind home plate, in front of the (home) umpire, and receives the ball from the pitcher. In addition to this primary duty, the catc ...

. He was also greatly interested in the school's military training. He rose rapidly in the ranks of the student battalion. One classmate described him as "indeed physically attractive without being handsome", but he was aloof, reserved and not generally popular. Although academically weak, Crane gained experience at Claverack that provided background (and likely some anecdotes from the Civil War veterans on the staff) for ''The Red Badge of Courage''.

In mid-1888, Crane became his brother Townley's assistant at a New Jersey shore news bureau, working there every summer until 1892. Crane's first publication under his byline was an article on the explorer Henry M. Stanley's quest to find the Scottish missionary David Livingstone in Africa. It appeared in the February 1890 Claverack College ''Vidette''. Within a few months, Crane was persuaded by his family to forgo a military career and transfer to

In mid-1888, Crane became his brother Townley's assistant at a New Jersey shore news bureau, working there every summer until 1892. Crane's first publication under his byline was an article on the explorer Henry M. Stanley's quest to find the Scottish missionary David Livingstone in Africa. It appeared in the February 1890 Claverack College ''Vidette''. Within a few months, Crane was persuaded by his family to forgo a military career and transfer to Lafayette College

Lafayette College is a private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Easton, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1826 by James Madison Porter and other citizens in Easton, the college first held classes in 18 ...

in Easton, Pennsylvania

Easton is a city in and the county seat of Northampton County, Pennsylvania, United States. The city's population was 28,127 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Easton is located at the confluence of the Lehigh River and the Delawa ...

, to pursue a mining engineering degree. He registered at Lafayette on September 12; he promptly took up baseball again and joined the largest fraternity, Delta Upsilon. He also joined both rival literary societies, named for (George) Washington and (Benjamin) Franklin. Crane infrequently attended classes and ended the semester with grades for four of his seven courses.

After one semester, Crane transferred to Syracuse University

Syracuse University (informally 'Cuse or SU) is a Private university, private research university in Syracuse, New York, United States. It was established in 1870 with roots in the Methodist Episcopal Church but has been nonsectarian since 1920 ...

, where he enrolled as a non-degree candidate in the College of Liberal Arts. He roomed in the Delta Upsilon fraternity house and joined the baseball team. Attending just one class (English Literature) during the middle trimester, he remained in residence while taking no courses in the third.

Concentrating on his writing, Crane began to experiment with tone and style while trying out different subjects. He published his fictional story, "Great Bugs of Onondaga," simultaneously in the '' Syracuse Daily Standard'' and the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' (from 1914: ''New York Tribune'') was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s ...

''. Declaring college "a waste of time", Crane decided to become a full-time writer and reporter. He attended a Delta Upsilon chapter meeting on June 12, 1891, but shortly afterward left college for good.

Full-time writer

In the summer of 1891, Crane often camped with friends in the nearby area ofSullivan County, New York

Sullivan County is a county in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 78,624. The county seat is Monticello. The county's name honors Major General John Sullivan, who was labeled at the time as a hero in th ...

, where his brother Edmund occupied a house obtained as part of their brother William's Hartwood Club (Association) land dealings. He used this area as the geographic setting for several short stories, which were posthumously published in a collection under the title ''Stephen Crane: Sullivan County Tales and Sketches''. Crane showed two of these works to ''New York Tribune'' editor Willis Fletcher Johnson, a family friend, who accepted them for publication. "Hunting Wild Dogs" and "The Last of the Mohicans" were the first of fourteen unsigned Sullivan County sketches and tales published in the ''Tribune'' between February and July 1892. Crane also showed Johnson an early draft of his first novel, '' Maggie: A Girl of the Streets''.

Later that summer, Crane met and befriended author Hamlin Garland, who had been lecturing locally on American literature and arts. On August 17, Garland gave a talk on novelist William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells ( ; March 1, 1837 – May 11, 1920) was an American Realism (arts), realist novelist, literary critic, playwright, and diplomat, nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters". He was particularly known for his tenure as editor of ...

, which Crane wrote up for the ''Tribune''. Garland became a mentor for and champion of the young writer, whose intellectual honesty impressed him. Their relationship suffered in later years, however, because Garland disapproved of Crane's alleged immorality, related to his living with a woman married to another man.

Stephen moved into his brother Edmund's house in Lakeview, a suburb of Paterson, New Jersey

Paterson ( ) is the largest City (New Jersey), city in and the county seat of Passaic County, New Jersey, Passaic County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, writing and reporting, particularly on its impoverished tenement districts.Davis, p. 42 Crane focused particularly on The Bowery

The Bowery () is a street and neighbourhood, neighborhood in Lower Manhattan in New York City, New York. The street runs from Chatham Square at Park Row (Manhattan), Park Row, Worth Street, and Mott Street in the south to Cooper Square at 4th ...

, a small and once prosperous neighborhood in southern Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

. After the Civil War, Bowery shops and mansions had given way to saloons, dance halls, brothels and flophouses, all of which Crane frequented. He later said he did so for research. He was attracted to the human nature found in the slums, considering it "open and plain, with nothing hidden." Believing nothing honest and unsentimental had been written about the Bowery, Crane became determined to do so himself; this was the setting of his first novel. On December 7, 1891, Crane's mother died at the age of 64, and the 20-year-old appointed Edmund as his guardian.

In the spring of 1892, Crane began a romance with Lily Brandon Munroe, a married woman who was estranged from her husband. He did so despite being frail, undernourished, and suffering from a hacking cough – none of which prevented him from smoking cigarettes.Davis, p. 47 Although Munroe later said Crane "was not a handsome man," she admired his "remarkable almond-shaped gray eyes." He begged her to elope with him, but her family opposed the match because Crane lacked money and prospects, and she declined. Their last meeting likely occurred in April 1898.

Between July 2 and September 11, 1892, Crane published more than ten news reports on Asbury Park affairs. Although a ''Tribune'' colleague stated that Crane "was not highly distinguished above any other boy of twenty who had gained a reputation for saying and writing bright things," that summer his reporting took on a more skeptical, hypocrisy-deflating tone. A storm of controversy erupted over a report he wrote on the Junior Order of United American Mechanics' American Day Parade, titled "Parades and Entertainments." Published on August 21, the report juxtaposes the "bronzed, slope-shouldered, uncouth" marching men "begrimed with dust" and the spectators dressed in "summer gowns, lace parasols, tennis trousers, straw hats and indifferent smiles." Believing they were being ridiculed, some JOUAM marchers were outraged and wrote to the editor. The owner of the ''Tribune'', Whitelaw Reid, was that year's Republican vice-presidential candidate, and this likely increased the sensitivity of the paper's management to the issue. Although Townley wrote a piece for the ''Asbury Park Daily Press'' in his brother's defense, the ''Tribune'' quickly apologized to its readers, calling Stephen Crane's piece "a bit of random correspondence, passed inadvertently by the copy editor." Hamlin Garland and biographer John Barry attested that Crane told them he had been dismissed by the ''Tribune''. Although Willis Fletcher Johnson later denied this, the paper did not publish any of Crane's work after 1892.

Life in New York

Crane struggled to make a living as a freelance writer, contributing sketches and feature articles to various New York newspapers. In October 1892, he moved into a rooming house in Manhattan whose boarders were a group of medical students. During this time, he expanded or entirely reworked ''Maggie: A Girl of the Streets''. In the winter of 1893, Crane took the manuscript of ''Maggie'' to Richard Watson Gilder, who rejected it for publication in ''The Century Magazine

''The Century Magazine'' was an illustrated monthly magazine first published in the United States in 1881 by The Century Company of New York City, which had been bought in that year by Roswell Smith and renamed by him after the Century Associati ...

''.

Crane decided to publish it privately, with money he had inherited from his mother. The novella was published in late February or early March 1893 by a small printing shop that usually printed medical books and religious tracts. The typewritten title page for the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

copyright application read simply: "A Girl of the Streets, / A Story of New York. / —By—/Stephen Crane." The name "Maggie" was added to the title later. Crane used the pseudonym "Johnston Smith" for the novella's initial publication, later telling friend and artist Corwin Knapp Linson that the ''nom de plume'' was the "commonest name I could think of. I had an editor friend named Johnson, and put in the 't', and no one could find me in the mob of Smiths". Hamlin Garland reviewed the work in the June 1893 issue of '' The Arena'', calling it "the most truthful and unhackneyed study of the slums I have yet read, fragment though it is". Despite this early praise, Crane became depressed and destitute from having spent $869 for 1,100 copies of a novel that did not sell; he ended up giving a hundred copies away. He would later remember "how I looked forward to publication and pictured the sensation I thought it would make. It fell flat. Nobody seemed to notice it or care for it... Poor Maggie! She was one of my first loves."

In March 1893, Crane spent hours in Linson's studio having his portrait painted. He became fascinated with issues of the ''Century'' that were largely devoted to famous battles and military leaders from the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. Frustrated with the dryly written stories, Crane stated, "I wonder that some of those fellows don't tell how they ''felt'' in those scraps. They spout enough of what they ''did'', but they're as emotionless as rocks." Crane returned to these magazines during subsequent visits to Linson's studio, and eventually the idea of writing a war novel overtook him. He would later state that he "had been unconsciously working the detail of the story out through most of his boyhood" and had imagined "war stories ever since he was out of knickerbockers". This novel would ultimately become '' The Red Badge of Courage''.

Crane wished to show how it felt to be in a war by writing "a psychological portrayal of fear".Davis, p. 65 Conceiving his story from the point of view of a young private who is at first filled with boyish dreams of the glory of war and then quickly becomes disillusioned, Crane borrowed the private's surname, "Fleming", from his sister-in-law's maiden name. He later said that the first paragraphs came to him with "every word in place, every comma, every period fixed". He wrote from around midnight until four or five in the morning. Because he could not afford a typewriter, he wrote carefully in ink on legal-sized paper, seldom crossing through or interlining a word. If he did change something, he would rewrite the whole page.

While working on his second novel, Crane remained prolific, concentrating on publishing stories to stave off poverty; "An Experiment in Misery", based on Crane's experiences in the Bowery, was printed by the ''New York Press''. He also wrote five or six poems a day.Davis, p. 82 In early 1894, he showed some of his poems to Hamlin Garland, who said he read "some thirty in all" with "growing wonder". Although Garland and William Dean Howells encouraged him to submit his poetry for publication, Crane's free verse

Free verse is an open form of poetry which does not use a prescribed or regular meter or rhyme and tends to follow the rhythm of natural or irregular speech. Free verse encompasses a large range of poetic form, and the distinction between free ...

was too unconventional for most. After brief wrangling between poet and publisher, Copeland & Day accepted Crane's first book of poems, ''The Black Riders and Other Lines'', although it would not be published until after ''The Red Badge of Courage''. He received a 10 percent royalty and the publisher assured him that the book would be in a form "more severely classic than any book ever yet issued in America".

In the spring of 1894, Crane offered the finished manuscript of ''The Red Badge of Courage'' to ''McClure's Magazine

''McClure's'' or ''McClure's Magazine'' (1893–1929) was an American illustrated monthly periodical popular at the turn of the 20th century. The magazine is credited with having started the tradition of muckraking journalism ( investigative, wat ...

'', which had become the foremost magazine for Civil War literature. While ''McClure's'' delayed giving him an answer on his novel, they offered him an assignment writing about the Pennsylvania coal mine

Coal mining is the process of resource extraction, extracting coal from the ground or from a mine. Coal is valued for its Energy value of coal, energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to Electricity generation, generate electr ...

s. "In the Depths of a Coal Mine", a story with pictures by Linson, was syndicated by ''McClure's'' in a number of newspapers, heavily edited. Crane was reportedly disgusted by the cuts, asking Linson, "Why the hell did they send me up there then? Do they want the public to think the coal mines gilded ball-rooms with the miners eating ice-cream in boiled shirt-fronts?"

During the early part of his career, Crane was promoted by Elbert Hubbard, who commented on his works and featured them in his popular small magazine, ''The Philistine''. Crane was the guest of honor at the first annual meeting of the Society of Philistines in 1895 when he was relatively unknown. Although Crane was severely teased during the meeting, they remained friendly and their association proved mutually beneficial. Seven of Crane’s poems and a short story were published in the first issue of ''The Roycroft Quarterly'' (another of Hubbard’s magazines) which commemorated the event. In a concluding note, Hubbard commented, "to the mass, he is known, if at all, only as the author of ''The Black Riders'' in verse, and of the ''Red Badge of Courage'' in prose; efforts, both, that challenge study and baffle understanding rather than soothe superficiality or pander to the wishes of mental indolence."

Sources report that following an encounter with a male prostitute that spring, Crane began a novel on the subject entitled '' Flowers of Asphalt,'' which he later abandoned. The manuscript has never been recovered.

After discovering that ''McClure's'' could not afford to pay him, Crane took his war novel to Irving Bacheller of the Bacheller-Johnson Newspaper Syndicate, which agreed to publish ''The Red Badge of Courage'' in serial form. From December 3 to 9, ''The Red Badge of Courage'' was published in some half-dozen newspapers in the United States. Although it was greatly cut for syndication, Bacheller attested to its causing a stir, saying "its quality asimmediately felt and recognized." The lead editorial in the '' Philadelphia Press'' of December 7 said that Crane "is a new name now and unknown, but everybody will be talking about him if he goes on as he has begun".

During the early part of his career, Crane was promoted by Elbert Hubbard, who commented on his works and featured them in his popular small magazine, ''The Philistine''. Crane was the guest of honor at the first annual meeting of the Society of Philistines in 1895 when he was relatively unknown. Although Crane was severely teased during the meeting, they remained friendly and their association proved mutually beneficial. Seven of Crane’s poems and a short story were published in the first issue of ''The Roycroft Quarterly'' (another of Hubbard’s magazines) which commemorated the event. In a concluding note, Hubbard commented, "to the mass, he is known, if at all, only as the author of ''The Black Riders'' in verse, and of the ''Red Badge of Courage'' in prose; efforts, both, that challenge study and baffle understanding rather than soothe superficiality or pander to the wishes of mental indolence."

Sources report that following an encounter with a male prostitute that spring, Crane began a novel on the subject entitled '' Flowers of Asphalt,'' which he later abandoned. The manuscript has never been recovered.

After discovering that ''McClure's'' could not afford to pay him, Crane took his war novel to Irving Bacheller of the Bacheller-Johnson Newspaper Syndicate, which agreed to publish ''The Red Badge of Courage'' in serial form. From December 3 to 9, ''The Red Badge of Courage'' was published in some half-dozen newspapers in the United States. Although it was greatly cut for syndication, Bacheller attested to its causing a stir, saying "its quality asimmediately felt and recognized." The lead editorial in the '' Philadelphia Press'' of December 7 said that Crane "is a new name now and unknown, but everybody will be talking about him if he goes on as he has begun".

Travels and fame

At the end of January 1895, Crane left on what he called "a very long and circuitous newspaper trip" to the west. While writing feature articles for the Bacheller syndicate, he traveled to

At the end of January 1895, Crane left on what he called "a very long and circuitous newspaper trip" to the west. While writing feature articles for the Bacheller syndicate, he traveled to Saint Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

, Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

, New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, Galveston, Texas

Galveston ( ) is a Gulf Coast of the United States, coastal resort town, resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island (Texas), Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a pop ...

, and Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

. Irving Bacheller would later state that he "sent Crane to Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

for new color", which the author found in the form of Mexican slum life. Whereas he found the lower class in New York pitiful, he was impressed by the "superiority" of the Mexican peasants' contentment and "even refuse to pity them".

Returning to New York five months later, Crane joined the Lantern (alternately spelled "Lanthom" or "Lanthorne") Club organized by a group of young writers and journalists.Wertheim (1994), p. 132 The club, located on the roof of an old house on William Street near the Brooklyn Bridge

The Brooklyn Bridge is a cable-stayed suspension bridge in New York City, spanning the East River between the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn. Opened on May 24, 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was the first fixed crossing of the East River. It w ...

, served as a drinking establishment and was decorated to look like a ship's cabin. There Crane ate one good meal a day, although friends were troubled by his "constant smoking, too much coffee, lack of food and poor teeth", as Nelson Greene put it. Living in near-poverty and greatly anticipating the publication of his books, Crane began work on two more novels: ''The Third Violet'' and '' George's Mother''.

''The Black Riders'' was published by Copeland & Day shortly before his return to New York in May, but it received mostly negative criticism for the poems' unconventional style and use of free verse. A piece in the ''Bookman'' called Crane "the Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley ( ; 21 August 187216 March 1898) was an English illustrator and author. His black ink drawings were influenced by Woodblock printing in Japan, Japanese woodcuts, and depicted the grotesque, the decadent, and the erotic. ...

of poetry" and a commentator from the '' Chicago Daily Inter-Ocean'' stated that "there is not a line of poetry from the opening to the closing page. Whitman's ''Leaves of Grass

''Leaves of Grass'' is a poetry collection by American poet Walt Whitman. After self-publishing it in 1855, he spent most of his professional life writing, revising, and expanding the collection until his death in 1892. Either six or nine separa ...

'' were luminous in comparison. Poetic lunacy would be a better name for the book." In June, the ''New York Tribune'' dismissed the book as "so much trash". Crane was pleased that the book was "making some stir".

In contrast to the reception for Crane's poetry, ''The Red Badge of Courage'' was welcomed with acclaim after its publication by Appleton in September 1895. For the next four months, the book was in the top six on bestseller lists around the country. It arrived on the literary scene "like a flash of lightning out of a clear winter sky", according to H. L. Mencken, who was about 15 at the time.Davis, p. 129 The novel also became popular in Britain; Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

, a future friend of Crane, wrote that the novel "detonated... with the impact and force of a twelve-inch shell charged with a very high explosive". Appleton published two, possibly three, printings in 1895 and as many as eleven more in 1896. Although some critics considered the work overly graphic and profane, it was widely heralded for its realistic portrayal of war and unique writing style. The ''Detroit Free Press

The ''Detroit Free Press'' (commonly referred to as the ''Freep'') is a major daily newspaper in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest local newspaper owned by Gannett (the publisher of ''USA Today''), and is operated by the Detro ...

'' declared that ''The Red Badge'' would give readers "so vivid a picture of the emotions and the horrors of the battlefield that you will pray your eyes may never look upon the reality."

Wanting to capitalize on the success of ''The Red Badge'', McClure Syndicate offered Crane a contract to write a series on Civil War battlefields. Because it was a wish of his to "visit the battlefield—which I was to describe—at the time of year when it was fought", Crane agreed. Visiting battlefields in Northern Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, including Fredericksburg, he would later produce five more Civil War tales: "Three Miraculous Soldiers", "The Veteran", "An Indiana Campaign", "An Episode of War" and "The Little Regiment".

Scandal

At the age of 24, Crane, who was reveling in his success, became involved in a highly publicized case involving a suspected prostitute named Dora Clark. At 2 a.m. on September 16, 1896, he escorted two chorus girls and Clark from New York City's Broadway Garden, a popular "resort" where he had interviewed the women for a series he was writing. As Crane saw one woman safely to astreetcar

A tram (also known as a streetcar or trolley in Canada and the United States) is an urban rail transit in which vehicles, whether individual railcars or multiple-unit trains, run on tramway tracks on urban public streets; some include s ...

, a plainclothes policeman named Charles Becker arrested the other two for solicitation; Crane was threatened with arrest when he tried to interfere. One of the women was released after Crane confirmed her erroneous claim that she was his wife, but Clark was charged and taken to the precinct. Against the advice of the arresting sergeant, Crane made a statement confirming Dora Clark's innocence, stating that "I only know that while with me she acted respectably, and that the policeman's charge was false." On the basis of Crane's testimony, Clark was discharged. The media seized upon the story; news spread to Philadelphia, Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

and beyond, with papers focusing on Crane's courage. The "Stephen Crane story", as it became known, soon became a source for ridicule; the ''Chicago Dispatch'' quipped that "Stephen Crane is respectfully informed that association with women in scarlet is not necessarily a 'Red Badge of Courage.' "

A couple of weeks after her trial, Clark pressed charges of false arrest against the officer who had arrested her. The next day, the officer physically attacked Clark in the presence of witnesses. Crane, who initially went briefly to Philadelphia to escape the pressure of publicity, returned to New York to give testimony at Becker's trial despite advice given to him from Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, who was Police Commissioner

A police commissioner is the head of a police department, responsible for overseeing its operations and ensuring the effective enforcement of laws and maintenance of public order. They develop and implement policies, manage budgets, and coordinate ...

and a new acquaintance of Crane. The defense targeted Crane: police raided his apartment and interviewed people who knew him, trying to find incriminating evidence to lessen the effect of his testimony. A vigorous cross-examination sought to portray Crane as a man of dubious morals; while the prosecution proved that he frequented brothels, Crane claimed this was merely for research purposes. After the trial ended on October 16, the arresting officer was exonerated, and Crane's reputation was ruined.

Cora Taylor and the ''Commodore'' shipwreck

Given $700 in Spanish gold by the Bacheller-Johnson syndicate to work as a war correspondent inCuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

as the Spanish–American War was pending, the 25-year-old Crane left New York on November 27, 1896, on a train bound for Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville ( ) is the most populous city proper in the U.S. state of Florida, located on the Atlantic coast of North Florida, northeastern Florida. It is the county seat of Duval County, Florida, Duval County, with which the City of Jacksonv ...

. Upon arrival in Jacksonville, he registered at the St. James Hotel under the alias of Samuel Carleton to maintain anonymity while seeking passage to Cuba. He toured the city and visited the local brothel

A brothel, strumpet house, bordello, bawdy house, ranch, house of ill repute, house of ill fame, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in Human sexual activity, sexual activity with prostitutes. For legal or cultural reasons, establis ...

s. Within days he met 31-year-old Cora Taylor, proprietor of the downtown bawdy house Hotel de Dream. Born into a respectable Boston family, Taylor (whose legal name was Cora Ethel Stewart) had already had two brief marriages; her first husband, Vinton Murphy, divorced her on grounds of adultery. In 1889, she had married British Captain Donald William Stewart. She left him in 1892 for another man, but was still legally married. By the time Crane arrived, Taylor had been in Jacksonville for two years. She lived a bohemian lifestyle, owned a hotel of assignation, and was a respected local figure. The two spent much time together while Crane awaited his departure. He was finally cleared to leave for the Cuban port of Cienfuegos on New Year's Eve aboard the SS ''Commodore''.

The ship sailed from Jacksonville with 27 or 28 men and supplies and ammunition for the Cuban rebels. On the

The ship sailed from Jacksonville with 27 or 28 men and supplies and ammunition for the Cuban rebels. On the St. Johns River

The St. Johns River () is the longest river in the U.S. state of Florida and is the most significant one for commercial and recreational use. At long, it flows north and winds through or borders 12 counties. The drop in elevation from River s ...

and less than from Jacksonville, ''Commodore'' struck a sandbar

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material, and rises from the bed of a body of water close to the surface or ...

in a dense fog and damaged its hull. Although towed off the sandbar the following day, it was beached again in Mayport and again damaged. A leak began in the boiler room that evening and, as a result of malfunctioning water pumps, the ship came to a standstill about from Mosquito Inlet. As the ship took on more water, Crane described the engine room as resembling "a scene at this time taken from the middle kitchen of hades

Hades (; , , later ), in the ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, is the god of the dead and the king of the Greek underworld, underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea ...

." The ''Commodore''s lifeboats were lowered early on January 2, 1897, and the ship ultimately sank at 7 a.m. Crane was one of the last to leave in a dinghy

A dinghy is a type of small boat, often carried or Towing, towed by a Watercraft, larger vessel for use as a Ship's tender, tender. Utility dinghies are usually rowboats or have an outboard motor. Some are rigged for sailing but they diffe ...

. In an ordeal that he recounted in the short story " The Open Boat", Crane and three other men (including the captain) foundered off the coast of Florida for a day and a half before trying to land the dinghy at Daytona Beach. The small boat overturned in the surf, forcing the exhausted men to swim to shore; one died. Having lost the gold given to him for his journey, Crane wired Cora Taylor for help. She traveled to Daytona and returned to Jacksonville with Crane the next day, only four days after he had left on the ''Commodore''.

The disaster was reported on the front pages of newspapers across the country. Rumors that the ship had been sabotaged were widely circulated but never substantiated. Portrayed favorably and heroically by the press, Crane emerged from the ordeal with his reputation enhanced, if not restored. Meanwhile, Crane's affair with Taylor blossomed.

Archaeological investigations were conducted in 2002–2004 to examine and document the exposed remains of a wreck near Ponce Inlet, Florida, conjectured to be that of the SS ''Commodore''. The collected data, and other accumulated evidence, finally substantiated the identification of the ''Commodore''.

Greco-Turkish War

Despite contentment in Jacksonville and the need for rest after his ordeal, Crane became restless. He left Jacksonville on January 11 for New York City, where he applied for a passport to Cuba, Mexico and the West Indies. Spending three weeks in New York, he completed "The Open Boat" and periodically visited Port Jervis to see family. By this time, however, blockades had formed along the Florida coast as tensions rose with Spain, and Crane concluded that he would never be able to travel to Cuba. He sold "The Open Boat" to Scribner's for $300 in early March. Determined to work as a war correspondent, Crane signed on withWilliam Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher and politician who developed the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His extravagant methods of yellow jou ...

's ''New York Journal'' to cover the impending Greco-Turkish conflict. He brought along Taylor, who sold the Hotel de Dream.

On March 20, they sailed first to England, where Crane was warmly received. They arrived in

On March 20, they sailed first to England, where Crane was warmly received. They arrived in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

in early April; between April 17 (when Turkey declared war on Greece) and April 22, Crane wrote his first published report of the war, "An Impression of the 'Concert' ". When he left for Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

in the northwest, Taylor remained in Athens, where she became the war's first woman war correspondent. She wrote under the pseudonym "Imogene Carter" for the ''New York Journal'', a job that Crane had secured for her. They wrote frequently, traveling throughout the country separately and together. The first large battle that Crane witnessed was the Turks' assault on General Constantine Smolenski's Greek forces at Velestino. Crane wrote: "It is a great thing to survey the army of the enemy. Just where and how it takes hold upon the heart is difficult of description." During this battle, Crane encountered "a fat waddling puppy" that he immediately claimed, dubbing it "Velestino, the Journal dog". Greece and Turkey signed an armistice on May 20; Crane and Taylor left Greece for England, taking with them Velestino and two Greek brothers as servants.

Spanish–American War

After staying inLimpsfield

Limpsfield is a village and civil parish in Surrey, England, at the foot of the North Downs close to Oxted railway station and the A25 road, A25.Oxted

Oxted is a town and civil parish in the Tandridge District, Tandridge district of Surrey, England. It is at the foot of the North Downs, south-east of Croydon, west of Sevenoaks, and north of East Grinstead.

Oxted is a commuter town and Ox ...

. Referring to themselves as Mr. and Mrs. Crane, the couple lived openly in England, but Crane concealed the relationship from friends and family in the United States. Admired in England, Crane thought himself attacked back home: "There seem so many of them in America who want to kill, bury and forget me purely out of unkindness and envy and—my unworthiness, if you choose", he wrote. Velestino the dog sickened and died soon after their arrival in England, on August 1. Crane, who had a great love for dogs, wrote an emotional letter to a friend an hour after the dog's death, stating that "for eleven days we fought death for him, thinking nothing of anything but his life."Berryman, p. 188 The Limpsfield-Oxted area was home to members of the socialist Fabian Society

The Fabian Society () is a History of the socialist movement in the United Kingdom, British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in ...

and a magnet for writers such as Edmund Gosse

Sir Edmund William Gosse (; 21 September 184916 May 1928) was an English poet, author and critic. He was strictly brought up in a small Protestant sect, the Plymouth Brethren, but broke away sharply from that faith. His account of his childhood ...

, Ford Madox Ford

Ford Madox Ford (né Joseph Leopold Ford Hermann Madox Hueffer ( ); 17 December 1873 – 26 June 1939) was an English novelist, poet, critic and editor whose journals ''The English Review'' and ''The Transatlantic Review (1924), The Transatlant ...

and Edward Garnett. Crane also met the Polish-born novelist Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

in October 1897, with whom he would have what Crane called a "warm and endless friendship".Davis, p. 245

Although Crane was confident among peers, strong negative reviews of the recently published ''The Third Violet'' were causing his literary reputation to dwindle. Reviewers were also highly critical of Crane's war letters, deeming them self-centered. Although ''The Red Badge of Courage'' had by this time gone through fourteen printings in the United States and six in England, Crane was running out of money. To survive financially, he wrote prolifically for both the English and the American markets. He wrote in quick succession stories such as ''The Monster'', "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky", "Death and the Child" and "The Blue Hotel". Crane began to attach price tags to his new works of fiction, hoping that "The Bride", for example, would fetch $175.

As 1897 ended, Crane's money crisis worsened. Amy Leslie, a reporter from Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

and a former lover, sued him for $550. The ''New York Times'' reported that Leslie gave him $800 in November 1896 but that he had repaid only a quarter. In February, he was summoned to answer Leslie's claim. The claim was apparently settled out of court, because no record of adjudication exists. Meanwhile, Crane felt "heavy with troubles" and "chased to the wall" by expenses. He confided to his agent that he was $2,000 in debt but that he would "beat it" with more literary output.

Soon after the exploded in Havana Harbor

Havana Harbor is the port of Havana, the capital of Cuba, and it is the main port in Cuba. Other port cities in Cuba include Cienfuegos, Matanzas, Manzanillo, Cuba, Manzanillo, and Santiago de Cuba.

The harbor was created from the natural Havan ...

on February 15, 1898, under suspicious circumstances, Crane was offered a £60 advance by '' Blackwood's Magazine'' for articles "from the seat of war in the event of a war breaking out" between the United States and Spain. His health was failing, and it is believed that signs of his pulmonary tuberculosis, which he may have contracted in childhood, became apparent. With almost no money coming in from his finished stories, Crane accepted the assignment and left Oxted for New York. Taylor and the rest of the household stayed behind to fend off local creditors. Crane applied for a passport and left New York for Key West

Key West is an island in the Straits of Florida, at the southern end of the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it con ...

two days before Congress declared war. While the war idled, he interviewed people and produced occasional copy.

In early June, he observed the establishment of an American base in Cuba when Marines seized Guantánamo Bay

Guantánamo Bay (, ) is a bay in Guantánamo Province at the southeastern end of Cuba. It is the largest harbor on the south side of the island and it is surrounded by steep hills which create an enclave that is cut off from its immediate hint ...

. He went ashore with the Marines, planning "to gather impressions and write them as the spirit moved." Although he wrote honestly about his fear in battle, others observed his calmness and composure. He would later recall "this prolonged tragedy of the night" in the war tale "Marines Signaling Under Fire at Guantanamo". After showing a willingness to serve during fighting at Cuzco, Cuba, by carrying messages to company commanders, Crane was officially cited for his "material aid during the action".

He continued to report upon various battles and the worsening military conditions and praised Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders

The Rough Riders was a nickname given to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, one of three such regiments raised in 1898 for the Spanish–American War and the only one to see combat. The United States Army was small, understaffed, and diso ...

, despite past tensions with the Commissioner. In early July, Crane was sent to the United States for medical treatment for a high fever. He was diagnosed with yellow fever, then malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

. Upon arrival in Old Point Comfort

Old Point Comfort is a point of land located in the Independent city (United States), independent city of Hampton, Virginia. Previously known as Point Comfort, it lies at the extreme tip of the Virginia Peninsula at the mouth of Hampton Roads in ...

, Virginia, he spent a few weeks resting in a hotel. Although Crane had filed more than 20 dispatches in the three months he had covered the war, the ''Worlds business manager believed that the paper had not received its money's worth and fired him. In retaliation, Crane signed with Hearst's ''New York Journal'' with the wish to return to Cuba. He traveled first to Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

and then to Havana. In September, rumors began to spread that Crane, who was working anonymously, had either been killed or disappeared. He sporadically sent out dispatches and stories about the mood and conditions in Havana, but he was soon desperate for money again. Taylor, left alone in England, was also penniless. She became frantic with worry over her lover's whereabouts; they were not in direct communication until the end of the year. Crane left Havana and arrived in England on January 11, 1899.

Death

Rent on Ravensbrook had not been paid for a year. Crane secured a solicitor to act as guarantor for their debts, after which Crane and Taylor relocated to Brede Place. This manor in Sussex, which dated to the 14th century and had neither electricity nor indoor plumbing, was offered to them by friends at a modest rent. The relocation appeared to give Crane hope, but his money problems continued. Deciding that he could no longer afford to write for American publications, he concentrated on publishing in English magazines. Crane pushed himself to write feverishly during the first months at Brede; he told his publisher that he was "doing more work now than I have at any other period in my life". His health worsened, and by late 1899 he was asking friends about health resorts. ''The Monster and Other Stories'' was in production and ''War Is Kind'', his second collection of poems, was published in the United States in May. None of his books after ''The Red Badge of Courage'' had sold well, and he bought atypewriter

A typewriter is a Machine, mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of Button (control), keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an i ...

to spur output. ''Active Service'', a novella based on Crane's correspondence experience, was published in October. The ''New York Times'' reviewer questioned "whether the author of ''Active Service'' himself really sees anything remarkable in his newspapery hero."

In December, the couple held an elaborate Christmas party at Brede, attended by Conrad,

In December, the couple held an elaborate Christmas party at Brede, attended by Conrad, Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

, H. G. Wells, and other friends; it lasted several days. On December 29 Crane suffered a severe pulmonary hemorrhage. In January 1900, he had recovered sufficiently to work on a new novel, ''The O'Ruddy'', completing 25 of the 33 chapters. Plans were made for him to travel as a correspondent to Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

to write sketches from Saint Helena

Saint Helena (, ) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km ...

, the site of a Boer

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

prison, but in late March and early April, he suffered two more hemorrhages. Taylor took over most of Crane's correspondence while he was ill, writing to friends for monetary aid. The couple planned to travel on the continent but Conrad, upon visiting Crane for the last time, remarked that his friend's "wasted face was enough to tell me that it was the most forlorn of all hopes."

On May 28, the couple arrived at Badenweiler, Germany, a health spa on the edge of the Black Forest

The Black Forest ( ) is a large forested mountain range in the States of Germany, state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is th ...

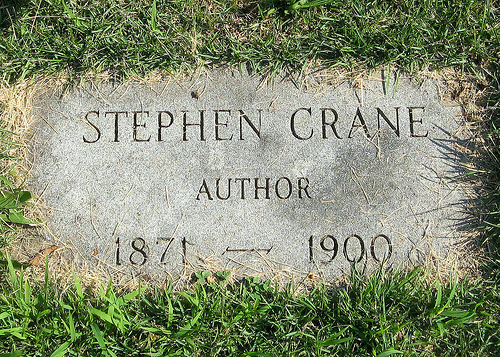

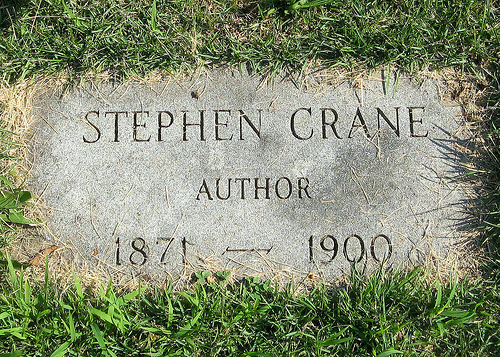

. Despite his weakened condition, Crane continued to dictate fragmentary episodes for the completion of ''The O'Ruddy''. He died on June 5, 1900, at the age of 28. In his will he left everything to Taylor, who took his body to New Jersey for burial. Crane was interred in Evergreen Cemetery in Hillside, New Jersey.

Fiction and poetry

Style and technique

Stephen Crane's fiction is typically categorized as representative of Naturalism,American realism