Stanley Forman Reed on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

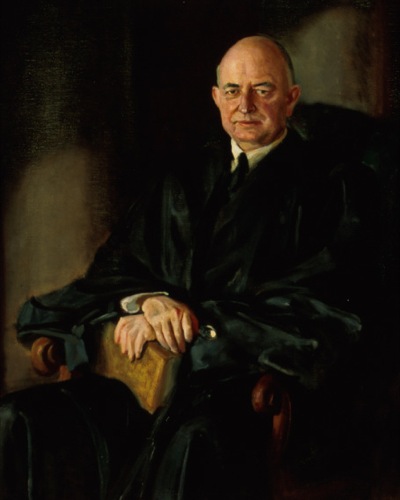

Stanley Forman Reed (December 31, 1884 – April 2, 1980) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an

Associate Justice

An associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some ...

of the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

from 1938 to 1957. He also served as U.S. Solicitor General from 1935 to 1938.

Born in Mason County, Kentucky

Mason County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 17,120. Its county seat is Maysville. The county was created from Bourbon County, Virginia in 1788 and named for George Mason, a Vir ...

, Reed established a legal practice in Maysville, Kentucky

Maysville is a "Home rule in the United States, home rule" class city in Mason County, Kentucky, Mason County, Kentucky, United States, and is the county seat of Mason County. The population was 8,873 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 ...

, and won election to the Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a ...

. He attended law school but did not graduate, making him the latest-serving Supreme Court Justice who did not graduate from law school. After serving in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Reed emerged as a prominent corporate attorney and took positions with the Federal Farm Board

The Federal Farm Board was established by the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1929 from the Federal Farm Loan Board established by the Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916, with a revolving fund of half a billion dollarsReconstruction Finance Corporation

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) was an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States federal government that served as a lender of last resort to US banks and businesses. Established in ...

. He took office as Solicitor General in 1935, and defended the constitutionality of several New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

policies.

After the retirement of Associate Justice George Sutherland

George Alexander Sutherland (March 25, 1862July 18, 1942) was a British-born American jurist and politician. He served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court between 1922 and 1938. As a member of the Republican Party, he also repre ...

, President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

successfully nominated Reed to the Supreme Court. Reed served until his retirement in 1957, and was succeeded by Charles Evans Whittaker. Reed wrote the majority opinion in cases such as '' Smith v. Allwright,'' '' Gorin v. United States,'' and '' Adamson v. California''. He authored dissenting opinions in cases such as '' Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education.''

Early life and education

Reed was born in the small town of Minerva inMason County, Kentucky

Mason County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 17,120. Its county seat is Maysville. The county was created from Bourbon County, Virginia in 1788 and named for George Mason, a Vir ...

on December 31, 1884, the son of wealthy physician John Reed and Frances (Forman) Reed. The Reeds and Formans traced their history to the earliest colonial period in America, and these family heritages were impressed upon young Stanley at an early age. At the age of 10, Reed moved with his family to Maysville, Kentucky

Maysville is a "Home rule in the United States, home rule" class city in Mason County, Kentucky, Mason County, Kentucky, United States, and is the county seat of Mason County. The population was 8,873 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 ...

where his father practiced medicine. The family resided downtown in a prominent home known as Phillips' Folly.

Reed attended Kentucky Wesleyan College and received a B.A. degree in 1902. He then attended Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

as an undergraduate, and obtained a second B.A. in 1906. He studied law at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his The Lawn, Academical Village, a World H ...

(where he was a member of St. Elmo Hall) and Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

, but did not obtain a law degree. Reed married the former Winifred Elgin in May 1908. The couple had two sons, John A. and Stanley Jr., who both became attorneys. In 1909 he traveled to France and studied at the Sorbonne as an auditeur bénévole.

Career

After his studies in France, Reed returned to Kentucky. He was admitted to the bar in 1910 and practiced in Maysville for nine years. He was elected as a Democratic member of theKentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a ...

in 1911 and reelected in 1913. He was defeated for a third term in 1915 by Republican candidate Harry P. Purnell. After the United States entered World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in April 1917, Reed joined the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

and was commissioned a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

in the intelligence division. When the war ended in 1918, Reed returned to his private law practice and became a well-known corporate attorney. He represented the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis Potter Huntington, it reached from Virginia's capital city of Rich ...

and the Kentucky Burley Tobacco Growers Association, among other large corporations. Stanley Reed was very active in the Sons of the American Revolution

The Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), formally the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (NSSAR), is a federally chartered patriotic organization. The National Society, a nonprofit corporation headquartered in Louisvi ...

and Society of Colonial Wars

The General Society of Colonial Wars is a patriotic society composed of men who trace their descents from forebears who, in military, naval, or civil positions of high trust and responsibility, by acts or counsel, assisted in the establishment, d ...

, while his wife was a national officer in the Daughters of the American Revolution

The National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (often abbreviated as DAR or NSDAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a patriot of the American Revolutionary War.

A non-p ...

. The Reeds settled on a farm near Maysville, where Stanley Reed raised prize-winning Holstein

Holstein (; ; ; ; ) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider (river), Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost States of Germany, state of Germany.

Holstein once existed as the German County of Holstein (; 8 ...

cattle in his spare time. After the war, Reed practiced as a partner in the Maysville firm of Worthington, Browning and Reed.

Federal Farm Bureau

Reed's work for a number of large agricultural interests in Kentucky made him a nationally known authority on the law of agriculturalcooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomy, autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned a ...

s. It was this reputation which brought him to the attention of federal officials.

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

had been elected President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

in November 1928, and took office in March 1929. The agricultural industry in the United States was heading for a depression. Unlike his predecessor, Hoover agreed to provide some federal support for agriculture, and in June 1929 Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

passed the Agriculture Marketing Act

The Agricultural Marketing Act of 1929, under the administration of Herbert Hoover, established the Federal Farm Board from the Federal Farm Loan Board established by the Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916 with a revolving fund of half a billion do ...

. The act established and was administered by the Federal Farm Board

The Federal Farm Board was established by the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1929 from the Federal Farm Loan Board established by the Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916, with a revolving fund of half a billion dollars The crash of the

Among Reed's more notable decisions are:

*'' United States v. Rock Royal Co-Op'', – This was one of the first cases in which Reed wrote the majority opinion. The case was especially important to Reed because of his prior career as an attorney for agricultural cooperatives (Rock Royal was a milk producers co-op). Reed stuck closely to the facts in the case, quoting at length from the statute, regulations and agency order.

*'' Gorin v. United States'', – Upheld several aspects of the

Among Reed's more notable decisions are:

*'' United States v. Rock Royal Co-Op'', – This was one of the first cases in which Reed wrote the majority opinion. The case was especially important to Reed because of his prior career as an attorney for agricultural cooperatives (Rock Royal was a milk producers co-op). Reed stuck closely to the facts in the case, quoting at length from the statute, regulations and agency order.

*'' Gorin v. United States'', – Upheld several aspects of the

Stanley F. Reed Oral History Project

Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries

Stanley F. Reed papers. Manuscript Collection, Special Collections, William T. Young Library, University of Kentucky.

* , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Reed, Stanley Forman 1884 births 1980 deaths American Protestants Columbia Law School alumni Kentucky Democrats Democratic Party members of the Kentucky House of Representatives Kentucky lawyers Kentucky Wesleyan College alumni People from Mason County, Kentucky Reconstruction Finance Corporation Members of the Sons of the American Revolution United States federal judges appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt Solicitors general of the United States Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States University of Virginia School of Law alumni 20th-century members of the Kentucky General Assembly

stock market

A stock market, equity market, or share market is the aggregation of buyers and sellers of stocks (also called shares), which represent ownership claims on businesses; these may include ''securities'' listed on a public stock exchange a ...

in late October 1929 led the Federal Farm Board's general counsel to resign. Although Reed was a Democrat, his reputation as a corporate agricultural lawyer led President Hoover to appoint him the new general counsel of the Federal Farm Board on November 7, 1929. Reed served as general counsel until December 1932.

Reconstruction Finance Corporation

In December 1932, the general counsel of theReconstruction Finance Corporation

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) was an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States federal government that served as a lender of last resort to US banks and businesses. Established in ...

(RFC) resigned, and Reed was appointed the agency's new general counsel. Since 1930, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve

The chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is the head of the Federal Reserve, and is the active executive officer of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The chairman presides at meetings of the Board.

...

, Eugene Meyer, had pressed Hoover to take a more active approach to ameliorating the Great Depression. Hoover finally relented and submitted legislation. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation Act was signed into law on January 22, 1932, but its operations were kept secret for five months. Hoover feared both political attacks from Republicans and that publicity about which corporations were receiving RFC assistance might disrupt the agency's attempts to keep companies financially viable. When Congress passed legislation in July 1932 forcing the RFC to make public the companies that received loans, the resulting political embarrassment led to the resignation of the RFC's president and his successor as well as other staff turnover at the agency. Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's election as president in November 1932 led to further staff changes. On December 1, 1932, the RFC's general counsel resigned, and Hoover appointed Reed to the position. Roosevelt, impressed with Reed's work and needing someone who knew the agency, its staff and its operations, kept Reed on. Reed mentored and protected the careers of a number of young lawyers at RFC, many of whom became highly influential in the Roosevelt administration: Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official who was accused of espionage in 1948 for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. The statute of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjur ...

, Robert H. Jackson, Thomas Gardiner Corcoran

Thomas Gardiner Corcoran (December 29, 1900 – December 6, 1981) was an Irish-American legal scholar. He was one of several advisors in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's brain trust during the New Deal, and later, a close friend and advisor ...

, Charles Edward Wyzanski Jr. (later an important federal district court judge), and David Cushman Coyle.

During his tenure at the RFC, Reed influenced two major national policies. First, Reed was instrumental in setting up the Commodity Credit Corporation

The Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) is a wholly owned United States government corporation that was created in 1933 to "stabilize, support, and protect farm income and prices" (federally chartered by the CCC Charter Act of 1948 (P.L. 80-806) ...

. In early October 1933, President Roosevelt ordered RFC president Jesse Jones to establish a program to strengthen cotton prices. On October 16, 1933, Jones met with Reed and together they created the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). President Roosevelt issued Executive Order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of the ...

6340 the next day, which legally established the CCC. The brilliance of the CCC was that the government would hold surplus cotton as security for the loan. If cotton prices rose above the value of the loan, farmers could redeem their cotton, pay off the loan and make a profit. If prices stayed low, the farmer still had enough money to live as well as plant next year. The plan worked so well that it became the basis for the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

's entire agricultural program.Schlesinger, ''The Age of Roosevelt: The Coming of the New Deal, 1933–1935'', 1958.

Second, Reed helped to successfully defend the administration's gold policy, saving the nation's monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to affect monetary and other financial conditions to accomplish broader objectives like high employment and price stability (normally interpreted as a low and stable rat ...

as well. Deflation

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0% and becomes negative. While inflation reduces the value of currency over time, deflation increases i ...

had caused the value of the United States dollar

The United States dollar (Currency symbol, symbol: Dollar sign, $; ISO 4217, currency code: USD) is the official currency of the United States and International use of the U.S. dollar, several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introdu ...

to fall nearly 60 percent. But federal law still permitted Americans and foreign citizens to redeem paper money and coins in gold at its pre-Depression value, causing a run on the gold reserves of the United States. Taking the United States off the gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

would stop the run. It would also further devalue the dollar, making American goods less expensive and more attractive to foreign buyers. In a series of moves, Roosevelt took the nation off the gold standard in March and April 1933, causing the dollar's value to sink. But additional deflation was needed. One way to do this was to raise the price of gold, but federal law required the Treasury to buy gold at its high, pre-Depression price. President Roosevelt asked the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to buy gold above the market price to further devalue the dollar. Although Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. believed the government lacked the authority to buy gold, Reed joined with Treasury general counsel Herman Oliphant to provide critical legal support for the plan.

The additional deflation helped stabilize the economy during a critical period where bank run

A bank run or run on the bank occurs when many Client (business), clients withdraw their money from a bank, because they believe Bank failure, the bank may fail in the near future. In other words, it is when, in a fractional-reserve banking sys ...

s were common."Stanley Reed Named Solicitor General," ''The New York Times'', March 19, 1935.Butkiewicz, "The Reconstruction Finance Corporation, the Gold Standard and the Banking Panic of 1933," ''Southern Economic Journal'', 1999; Eichengreen, ''Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939'', 1992; Wicker, ''The Banking Panics of the Great Depression'', 1996.

Reed's help with Roosevelt's gold policies was not yet finished. On June 5, 1933, Congress passed a joint resolution (48 Stat. 112) voiding clauses in all public and private contracts permitting redemption in gold. Hundreds of angry creditors sued to overturn the law. The case finally reached the U.S. Supreme Court. United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general is the head of the United States Department of Justice and serves as the chief law enforcement officer of the Federal government of the United States, federal government. The attorney general acts as the princi ...

Homer Stille Cummings asked Reed to join him in writing the government's brief for the Court and assisting him during oral argument. Reed's help was critical, for the high court was resolutely conservative when it came to the sanctity of contracts.

On February 2, 1935, the Supreme Court made the unprecedented announcement that it was delaying its ruling by a week. The court shocked the nation again by announcing a second delay on February 9. Finally, on February 18, 1935, the Supreme Court held in '' Norman v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co.'', , that the government had the power to abrogate private contracts but not public ones. However, the majority said that since there had been no showing that contractors with the federal government had been harmed, no payments would be made.

Solicitor General

Reed's invaluable assistance in defending the federal government's interests in "the Gold Clause Cases" led Roosevelt to appoint him Solicitor General. J. Crawford Biggs, the incumbent Solicitor General, was generally considered ineffective if not incompetent (he had lost 10 of the 17 cases he argued in his first five months in office). Biggs resigned on March 14, 1935. Reed was named his replacement on March 18 and confirmed by theSenate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

on March 25. He was confronted by an office in chaos. Several major challenges to the National Industrial Recovery Act

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) was a US labor law and consumer law passed by the 73rd US Congress to authorize the president to regulate industry for fair wages and prices that would stimulate economic recovery. It als ...

—considered the cornerstone of the New Deal—were reaching the Supreme Court, and Reed was forced to drop the appeals because the Office of the Solicitor General was unprepared to argue them. Reed worked quickly to restore order, and subsequent briefs were noted for their strong legal argument and extensive research. Reed soon brought before the high court appeals of the constitutionality of the Agricultural Adjustment Act

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was a United States federal law of the New Deal era designed to boost agricultural prices by reducing surpluses. The government bought livestock for slaughter and paid farmers Subsidy, subsidies not to plant ...

, Securities Act of 1933

The Securities Act of 1933, also known as the 1933 Act, the Securities Act, the Truth in Securities Act, the Federal Securities Act, and the '33 Act, was enacted by the United States Congress on May 27, 1933, during the Great Depression and afte ...

, Social Security Act

The Social Security Act of 1935 is a law enacted by the 74th United States Congress and signed into law by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on August 14, 1935. The law created the Social Security (United States), Social Security program as ...

, National Labor Relations Act

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, is a foundational statute of United States labor law that guarantees the right of private sector employees to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, an ...

, Bankhead Cotton Control Act, Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, Guffey Coal Control Act, Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935 and the enabling act for the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...

, and revived the battle over the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). The press of appeals was so great that Reed argued six major cases before the Supreme Court in two weeks. On December 10, 1935, he collapsed from exhaustion during oral argument before the Court. Reed lost a number of these cases, including '' Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States'', (invalidating the National Industrial Recovery Act) and '' United States v. Butler'', (invalidating the Agricultural Adjustment Act).Schlesinger, ''The Age of Roosevelt: The Politics of Upheaval, 1935–1936'', 1960.Hoffer, Hoffer, Hull and Hull, ''The Supreme Court: An Essential History'', 2007.Jost, ''The Supreme Court A-Z'', 1998.

1937 proved to be a banner year for the Solicitor General. Reed argued and won such major cases as '' West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish'', (upholding minimum wage laws), '' National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation'', (upholding the National Labor Relations Act), and '' Steward Machine Company v. Davis'', (upholding the taxing power of the Social Security Act). By the end of 1937, Reed was winning most of his economic cases and had a reputation as being one of the strongest Solicitors General since the creation of the office in 1870.

Supreme Court

Nomination and confirmation

On January 15, 1938, President Roosevelt nominated Reed as anassociate justice

An associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some ...

on the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

to succeed retiring justice George Sutherland

George Alexander Sutherland (March 25, 1862July 18, 1942) was a British-born American jurist and politician. He served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court between 1922 and 1938. As a member of the Republican Party, he also repre ...

. Many in the nation's capital worried about the nomination fight. Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter (April 17, 1859 – February 8, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1911 to 1937. He was a staunch conservative and was regarded as a part of the Four ...

, one of the Court's conservative " Four Horsemen," had retired the previous summer. Roosevelt had nominated Senator Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, ass ...

as his replacement, and Black's nomination battle proved to be a long (seven days) and bitter one. To the relief of many, Reed's nomination was swift and generated little debate in the Senate. He was confirmed on January 25, 1938, and sworn into office on January 31. His successor as Solicitor General was Robert H. Jackson. Reed is the last person to serve as a Supreme Court Justice without possessing a law degree.

Stanley Reed spent 19 years on the Supreme Court. Within two years, he was joined on the bench by his mentor, Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

, and his protégé, Robert H. Jackson. Reed and Jackson held very similar views on national security issues and often voted together. Reed and Frankfurter also held similar views, and Frankfurter usually concurred with Reed. However, the two had significantly different writing styles, as Frankfurter offered lengthy, professorial discussions of the law, whereas Reed wrote terse opinions keeping to the facts of the case.Fassett, "The Buddha and the Bumblebee: The Saga of Stanley Reed and Felix Frankfurter," ''Journal of Supreme Court History'', July 2003.

Reed was considered a moderate and often provided the critical fifth vote in split rulings. He authored more than 300 opinions, and Chief Justice Warren Burger

Warren Earl Burger (September 17, 1907 – June 25, 1995) was an American attorney who served as the 15th chief justice of the United States from 1969 to 1986.

Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Burger graduated from the St. Paul College of Law i ...

said "he wrote with clarity and firmness...." Reed was an economic progressive, and generally supported racial desegregation, civil liberties, trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

rights and economic regulation. On free speech, national security and certain social issues, however, Reed was generally a conservative. He often approved of federal (but not state or local) restrictions on civil liberties. Reed also opposed applying the Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

to the states via the 14th Amendment.

Opinions

Among Reed's more notable decisions are:

*'' United States v. Rock Royal Co-Op'', – This was one of the first cases in which Reed wrote the majority opinion. The case was especially important to Reed because of his prior career as an attorney for agricultural cooperatives (Rock Royal was a milk producers co-op). Reed stuck closely to the facts in the case, quoting at length from the statute, regulations and agency order.

*'' Gorin v. United States'', – Upheld several aspects of the

Among Reed's more notable decisions are:

*'' United States v. Rock Royal Co-Op'', – This was one of the first cases in which Reed wrote the majority opinion. The case was especially important to Reed because of his prior career as an attorney for agricultural cooperatives (Rock Royal was a milk producers co-op). Reed stuck closely to the facts in the case, quoting at length from the statute, regulations and agency order.

*'' Gorin v. United States'', – Upheld several aspects of the Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code ( ...

*'' Smith v. Allwright'', – In 1935, a unanimous Supreme Court in '' Grovey v. Townsend'', , had held that political parties in Texas did not violate the constitutional rights of African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

citizens by denying them the right to vote in a primary election

Primary elections or primaries are elections held to determine which candidates will run in an upcoming general election. In a partisan primary, a political party selects a candidate. Depending on the state and/or party, there may be an "open pr ...

. But in ''Smith v. Allwright'', the issue came before the Court again. This time, the plaintiff alleged that the state, not the political party, had denied black citizens the right to vote. In an 8-to-1 decision authored by Reed, the Supreme Court overruled ''Grovey'' as wrongly decided. In ringing terms, Reed dismissed the state action question and declared that "the Court throughout its history has freely exercised its power to reexamine the basis of its constitutional decisions." The lone dissenter was Justice Roberts, who had written the majority opinion nine years earlier in ''Grovey.''

*'' Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia'', – In a 7-to-1 ruling, Reed applied the undue burden standard

The undue burden standard is a constitutional test fashioned by the Supreme Court of the United States. The test, first developed in the late 20th century, is widely used in American constitutional law. In short, the undue burden standard states t ...

to a Virginia law which required separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protectio ...

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

in public transportation. Reed found that the law created an undue burden because uniformity of law was essential in certain interstate activities, such as transportation.

*'' Adamson v. California'', – Adamson was charged with murder but chose not to testify because he knew the prosecutor would ask him about his prior criminal record. Adamson argued that, because the prosecutor had drawn attention to his refusal to testify, Adamson's freedom against self-incrimination had been violated. Reed wrote that the rights guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment did not extend the protections of the Fifth Amendment to state courts. Reed felt that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment did not intend to apply the Bill of Rights to states without limitation.

*'' Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education'', – Reed said he was proudest of his dissent in ''Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education.'' The ruling was the first to declare that a state had violated the Establishment Clause

In United States law, the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, together with that Amendment's Free Exercise Clause, form the constitutional right of freedom of religion. The ''Establishment Clause'' an ...

. Reed disliked the phrase "wall of separation between church and state," and his dissent contains his famous dictum about the phrase: "A rule of law should not be drawn from a figure of speech."

*'' Pennekamp v. Florida'', – Reed authored this majority opinion for a court which confronted the issue of whether judges could censor newspapers for impugning the reputation of the courts. The ''Miami Herald

The ''Miami Herald'' is an American daily newspaper owned by McClatchy, The McClatchy Company and headquartered in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Founded in 1903, it is the fifth-largest newspaper in Florida, serving Miami-Dade, Broward County, Fl ...

'' newspaper had published two editorials and a cartoon criticizing a Florida court's actions in a pending trial. The judge cited the publisher and editors for contempt

In colloquial usage, contempt usually refers to either the act of despising, or having a general lack of respect for something. This set of emotions generally produces maladaptive behaviour. Other authors define contempt as a negative emotio ...

, claiming that the published material maligned the integrity of the court and thereby interfered with the fair administration of justice. Hewing closely to the facts in the case, Reed used the clear and present danger

''Clear and Present Danger'' is a political thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and published on August 17, 1989. A sequel to '' The Cardinal of the Kremlin'' (1988), main character Jack Ryan becomes acting Deputy Director of Intelligence i ...

test to come down firmly on the side of freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

.

*'' Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', – This was recognized as a critical case even before it reached the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Earl Warren, realizing how controversial the case would be for the public, very much wanted to avoid any dissents in the case, but Reed was the lone hold-out. Other members of the Supreme Court worried about Reed's commitment to civil rights, as he was a member of the (then) all-white Burning Tree Club in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and his Kentucky home had an all-white restrictive covenant

A covenant, in its most general and covenant (historical), historical sense, is a solemn promise to engage in or refrain from a specified action. Under historical English common law, a covenant was distinguished from an ordinary contract by the ...

(a covenant which had led Reed to recuse himself from a civil rights case in 1948). Nonetheless, Reed had written the majority decision in '' Smith v. Allwright'' and joined the majority in '' Sweatt v. Painter'', , which barred separate but equal racial segregation in law schools. Reed originally planned to write a dissent in ''Brown'', but joined the majority before a decision was issued. Many observers, including Chief Justice Warren, believed a unanimous decision in ''Brown'' was necessary to win public acceptance for the decision. Reed reportedly cried during the reading of the opinion.

Hiss case

Reed's fame and notoriety did not stem solely from his judicial rulings, however. In 1949, Reed was caught up in theAlger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official who was accused of espionage in 1948 for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. The statute of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjur ...

case. Hiss, one of Reed and Frankfurter's protégés, was accused of espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

in August 1948. Hiss was tried in June 1949. Hiss's attorneys subpoenaed both Reed and Frankfurter. Although Reed ethically objected to having a sitting Associate Justice of the Supreme Court testify in a legal proceeding, he agreed to do so once he was subpoenaed. A number of observers strongly denounced Reed for refusing to disobey the subpoena.

Dissents and retirement

By the mid-1950s, Justice Reed was dissenting more and more frequently from court rulings. His first full dissent had come in 1939, nearly a year after his tenure on the court began. Initially, his dissents "were only when, with Hughes, Brandeis, Stone or Roberts—like himself, lawyers of deep experience—he could not go along with what he considered the judge-made amendments of the Constitution implicit in the opinions ofHugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, ass ...

, Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

, William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 to 1975. Douglas was known for his strong progressive and civil libertari ...

and Frank Murphy, whom Roosevelt had sent to follow Black and Reed on the court." But by 1955, Reed was dissenting much more frequently. Reed began to feel that the Court's jurisprudential center had shifted too far away from him and that he was losing his effectiveness.

Retirement

Stanley Reed retired from the Supreme Court on February 25, 1957, citing old age. He was 73 years old. Charles Evans Whittaker was appointed his successor. Reed led a fairly active retirement. In November 1957, PresidentDwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

asked Reed to chair the newly formed United States Commission on Civil Rights

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (CCR) is a bipartisan, independent commission of the United States federal government, created by the Civil Rights Act of 1957 during the Eisenhower administration, that is charged with the responsibility f ...

. Eisenhower announced the nomination on November 7, but Reed turned down the nomination on December 3. Reed cited the impropriety of having a former Associate Justice sit on such a political body. But some media reports indicated that his appointment would have been opposed by civil rights activists, who felt Reed was not sufficiently progressive.

Reed did, however, continue to serve the federal judiciary in a number of ways. For several years, he served as a temporary judge on a number of lower federal courts, particularly in the District of Columbia

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

. He also served in special capacities where judicial experience was needed, such as boundary disputes between states.

In 1958 he was elected as a hereditary member of the New Jersey Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a lineage society, fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of milita ...

by right of his descent from Colonel David Forman.

Death

Increasingly frail and often ill, Stanley Reed and his wife lived at the Hilaire Nursing Home inHuntington, New York

Huntington is one of ten Administrative divisions of New York#Town, towns in Suffolk County, New York, Suffolk County, New York (state), New York, United States. The town's population was 204,127 at the time of the 2020 census, making it the 11 ...

for the last few years of their lives.

Reed died there on April 2, 1980. He was survived by his wife and sons. He was interred in Maysville, Kentucky

Maysville is a "Home rule in the United States, home rule" class city in Mason County, Kentucky, Mason County, Kentucky, United States, and is the county seat of Mason County. The population was 8,873 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 ...

.

Although he retired eighteen years before William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 to 1975. Douglas was known for his strong progressive and civil libertari ...

, Reed outlived him by two months and was the last living Justice appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, and the last living justice to have served on the Hughes Court, Stone Court and Vinson Court.

Legacy

An extensive collection of Reed's personal and official papers, including his Supreme Court files, is archived at theUniversity of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a Public University, public Land-grant University, land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky, United States. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical ...

in Lexington, where they are open for research.

Quotations

*"The United States is a constitutional democracy. Its organic law grants to all citizens a right to participate in the choice of elected officials without restriction by any state because of race." – ''Smith v. Allwright'', 321 U.S. 649 (1944) *"There is a recognized abstract principle, however, that may be taken as a postulate for testing whether particular state legislation in the absence of action by Congress is beyond state power. This is that the state legislation is invalid if it unduly burdens that commerce in matters where uniformity is necessary—necessary in the constitutional sense of useful in accomplishing a permitted purpose." – ''Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia'', 328 U.S. 373 (1946) *"Freedom of discussion should be given the widest possible range compatible with the essential requirement of the fair and orderly administration of justice. ... That a judge might be influenced by a desire to placate the accusing newspaper to retain public esteem and secure reelection at the cost of unfair rulings against an accused is too remote a possibility to be considered aclear and present danger

''Clear and Present Danger'' is a political thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and published on August 17, 1989. A sequel to '' The Cardinal of the Kremlin'' (1988), main character Jack Ryan becomes acting Deputy Director of Intelligence i ...

to justice." – ''Pennekamp v. Florida'', 328 U.S. 331 (1946)

*"A rule of law should not be drawn from a figure of speech." – ''Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education'', 333 U.S. 203 (1948) (commenting on the phrase "wall of separation between church and state")

*"Philosophers and poets, thinkers of high and low degree from every age and race have sought to expound the meaning of virtue, but each teaches his own conception of the moral excellence that satisfies standards of good conduct. Are the tests of the Puritan or the Cavalier to be applied, those of the city or the farm, the Christian or non-Christian, the old or the young? Does the Bill of Rights permit Illinois to forbid any reflection on the virtue of racial or religious classes which a jury or a judge may think exposes them to derision or obloquy, words themselves of quite uncertain meaning as used in the statute? I think not." – ''Beauharnais v. Illinois'', 343 U.S. 250 (1952)

Law clerks

* David M. Becker, SEC General CounselSee also

* List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States * List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 6) *List of United States federal judges by longevity of service

These are lists of Article III United States federal judges by longevity of service. Senate confirmation along with presidential appointment to an Article III court entails a lifelong appointment, unless the judge is impeached, resigns, retires, ...

* List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

A total of 116 people have served on the Supreme Court of the United States, the highest judicial body in the United States, since it was established in 1789. Supreme Court justices have life tenure, meaning that they serve until they die, resig ...

* United States Supreme Court cases during the Hughes Court

* United States Supreme Court cases during the Stone Court

* United States Supreme Court cases during the Vinson Court

* United States Supreme Court cases during the Warren Court

* Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official who was accused of espionage in 1948 for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. The statute of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjur ...

Notes

References

Sources

*"Bogue Quits as R.F.C. Counsel." ''New York Times.'' December 2, 1932. *Butkiewicz, James L. "The Reconstruction Finance Corporation, the Gold Standard and the Banking Panic of 1933." ''Southern Economic Journal.'' 1999. *Conklin, William R. "Frankfurter, Reed Testify to Loyalty, Integrity of Hiss." ''New York Times.'' June 23, 1949. *Dinwoodey, Dean. "New NRA Test Case Covers Basic Issues." ''New York Times.'' April 7, 1935. *Eichengreen, Barry J. ''Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939.'' New ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. *"Ex-Justice Reed to Hear Case." ''New York Times.'' March 4, 1958. *"Farm Board Counsel to Retire." ''New York Times.'' November 8, 1929. *Fassett, John D. "The Buddha and the Bumblebee: The Saga of Stanley Reed and Felix Frankfurter." ''Journal of Supreme Court History.'' 28:2 (July 2003). *Fassett, John D. ''New Deal Justice: The Life of Stanley Reed of Kentucky.'' New York: Vantage Press, 1994. *"Federal Judge in Missouri Named to Supreme Court." ''New York Times.'' March 3, 1957. *Goodman Jr., George. "Ex-Justice Stanley Reed, 95, Dead." ''New York Times.'' April 4, 1980. *"High Court Holds Challenge of NLRB Must Await Board Order Against Company." ''New York Times.'' February 1, 1938. *Hoffer, Peter Charles; Hoffer, William James Hull; and Hull, N.E.H. ''The Supreme Court: An Essential History.'' Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 2007. *Huston, Luther A. "High Court Bars Trials By States In Sedition Cases." ''New York Times.'' April 3, 1956. *Huston, Luther A. "High Court Upholds Deportation And Denial of Bail to Alien Reds." ''New York Times.'' March 11, 1952. *Huston, Luther A. "Justice Reed, 72, to Retire From the Supreme Court." ''New York Times.'' February 1, 1957. *"Jackson Is Named Solicitor General." ''New York Times.'' January 28, 1938. *Jost, Kenneth. ''The Supreme Court A-Z.'' 1st ed. New York: Routledge, 1998. *"Justice Reed Retires From Supreme Court." ''New York Times.'' February 26, 1957. *"Justices on Stand Called 'Degrading'." ''Associated Press.'' July 18, 1949. *Kennedy, David M. ''Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. 0195038347 *Kluger, Richard. ''Simple Justice.'' Paperback ed. New York: Vantage Press, 1977. *Krock, Arthur. "Reed's Views Reflect Changing High Court." ''New York Times.'' February 3, 1957. *Lewis, Anthony. "Eisenhower Picks Civil Rights Unit." ''New York Times.'' November 8, 1957. *Lewis, Anthony. "Reed Turns Down Civil Rights Post." ''New York Times.'' December 4, 1957. *"Map Legal Battle for AAA Program." ''Associated Press.'' September 23, 1935. *Mason, Joseph R. "The Political Economy of Reconstruction Finance Corporation Assistance During the Great Depression." ''Explorations in Economic History.'' 40:2 (April 2003). *"Murphy, Jackson Inducted Together." ''New York Times.'' January 19, 1940. *Nash, Gerald D. "Herbert Hoover and the Origins of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation." ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review.'' December 1959. *"New Deal Pleas Won Reed Fame." ''New York Times.'' January 16, 1938. *Olson, James S. ''Saving Capitalism: The Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the New Deal, 1933–1940.'' Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1988. *"Potomac Pact Delayed." ''New York Times.'' November 22, 1960. *"Reed Given Court Task." ''United Press International.'' October 29, 1957. *"Reed In Collapse." ''New York Times.'' December 11, 1935. *Schlesinger, Arthur M. ''The Age of Roosevelt: The Coming of the New Deal, 1933–1935.'' Paperback ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1958. *Schlesinger, Arthur M. ''The Age of Roosevelt: The Crisis of the Old Order, 1919–1933.'' Paperback ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1957. *Schlesinger, Arthur M. ''The Age of Roosevelt: The Politics of Upheaval, 1935–1936.'' Paperback ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1960. *"Senate Quickly Confirms Reed Nomination." ''New York Times.'' January 26, 1938. *"Stanley Reed Goes to Supreme Court." ''New York Times.'' January 16, 1938. *"Stanley Reed Named Solicitor General." ''New York Times.'' March 19, 1935. *Stark, Louis. "Belcher Test Case of Validity of NRA to Be Abandoned." ''New York Times.'' March 26, 1935. *Stark, Louis. "High Court Affirms Non-Red Taft Oath." ''New York Times.'' May 9, 1950. *"3 Justice Step Out of 'Covenants' Case." ''Associated Press.'' January 16, 1948. *Tomlins, Christopher, ed. ''The United States Supreme Court: The Pursuit of Justice.'' New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2005. *"Urges High Court to Give 7A Ruling." ''New York Times.'' April 12, 1935. *Urofsky, Melvin I. ''Division & Discord: The Supreme Court Under Stone and Vinson, 1941–1953.'' New ed. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1998. *Walz, Jay. "Decision Is 6 to 2." ''New York Times.'' June 5, 1951. *Wicker, Elmus. ''The Banking Panics of the Great Depression.'' New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. *Wood, Lewis. "High Court Rules Negroes Can Vote In Texas Primary." ''New York Times.'' April 4, 1944. *Wood, Lewis. "Sutherland Quits Supreme Court." ''New York Times.'' January 6, 1938.Further reading

*Abraham, Henry J., ''Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court. 3d. ed.'' (New York:Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 1992). .

*Cushman, Clare, ''The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies,1789–1995'' (2nd ed.) ( Supreme Court Historical Society), (Congressional Quarterly

''Congressional Quarterly'', or ''CQ'', is an American publication that is part of the privately owned publishing company CQ Roll Call, which covers the United States Congress. ''CQ'' was formerly acquired by the U.K.-based Economist Group and ...

Books, 2001) ; .

*Frank, John P., ''The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions'' (Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, editors) ( Chelsea House Publishers: 1995) , .

*Martin, Fenton S. and Goehlert, Robert U., ''The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography'', (Congressional Quarterly Books, 1990). .

*Urofsky, Melvin I., ''The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary'' (New York: Garland Publishing

Garland Science was a publishing group that specialized in developing textbook

A textbook is a book containing a comprehensive compilation of content in a branch of study with the intention of explaining it. Textbooks are produced to meet t ...

1994). 590 pp. ; .

External links

Stanley F. Reed Oral History Project

Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries

Stanley F. Reed papers. Manuscript Collection, Special Collections, William T. Young Library, University of Kentucky.

* , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Reed, Stanley Forman 1884 births 1980 deaths American Protestants Columbia Law School alumni Kentucky Democrats Democratic Party members of the Kentucky House of Representatives Kentucky lawyers Kentucky Wesleyan College alumni People from Mason County, Kentucky Reconstruction Finance Corporation Members of the Sons of the American Revolution United States federal judges appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt Solicitors general of the United States Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States University of Virginia School of Law alumni 20th-century members of the Kentucky General Assembly