Spencer Baird on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

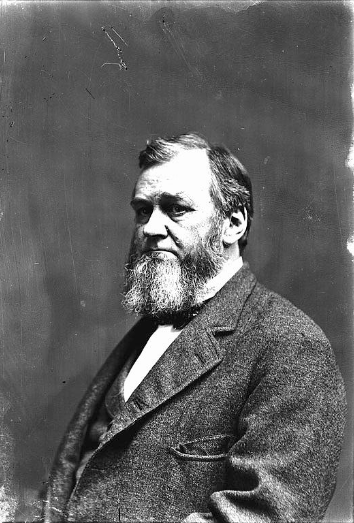

Spencer Fullerton Baird (; February 3, 1823 – August 19, 1887) was an American

Eventually, he became the Assistant Secretary, serving under

Eventually, he became the Assistant Secretary, serving under

Spencer Fullerton Baird died on August 19, 1887. Upon Baird's death, the Arts and Industries building was draped with a mourning cloth.

Spencer Fullerton Baird died on August 19, 1887. Upon Baird's death, the Arts and Industries building was draped with a mourning cloth.

Spencer F. Baird's Vision for a National Museum

online exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution Archives

from the

National Academy of Sciences Biographical MemoirSpencer Fullerton Baird Index of Corresondents, 1850s - 1870s

{{DEFAULTSORT:Baird, John Fullerton 1823 births 1887 deaths 19th-century American naturalists American taxonomists American ichthyologists American ornithologists Dickinson College alumni Secretaries of the Smithsonian Institution United States Fish Commission personnel People from Carlisle, Pennsylvania People from Reading, Pennsylvania Burials at Oak Hill Cemetery (Washington, D.C.) West Nottingham Academy alumni Columbia University alumni 19th-century American zoologists Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Members of the American Philosophical Society

naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

, ornithologist

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

, ichthyologist

Ichthyology is the branch of zoology devoted to the study of fish, including bony fish (Osteichthyes), cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes), and jawless fish (Agnatha). According to FishBase, 35,800 species of fish had been described as of March 2 ...

, herpetologist

Herpetology (from Ancient Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is a branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, salamanders, and caecilians (Gymnophiona)) and reptiles (in ...

, and museum curator

A curator (from , meaning 'to take care') is a manager or overseer. When working with cultural organizations, a curator is typically a "collections curator" or an "exhibitions curator", and has multifaceted tasks dependent on the particular ins ...

. Baird was the first curator to be named at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

. He eventually served as assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian from 1850 to 1878, and as Secretary from 1878 until 1887. He was dedicated to expanding the natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

collections of the Smithsonian which he increased from 6,000 specimens in 1850 to over 2 million by the time of his death. He also served as the U.S. Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries from 1871 to 1887 and published over 1,000 works during his lifetime.

Early life and education

Spencer Fullerton Baird was born inReading, Pennsylvania

Reading ( ; ) is a city in Berks County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. The city had a population of 95,112 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, fourth-most populous ...

in 1823. His mother was a member of the prominent Philadelphia Biddle family

The Biddle family of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania is an Old Philadelphians, Old Philadelphian family descended from English immigrants William Biddle (1630–1712) and Sarah Kempe (1634–1709), who arrived in the Province of New Jersey in 1681. ...

; he was a nephew of Speaker of the Pennsylvania Senate Charles B. Penrose and a first cousin, once removed, of U.S. Senator Boies Penrose and his distinguished brothers, Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language">Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'st ...

, Spencer, and Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

. He became a self-trained naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

as a young man, learning about the field from his brother, William, who was a birder

Birdwatching, or birding, is the observing of birds, either as a recreational activity or as a form of citizen science. A birdwatcher may observe by using their naked eye, by using a visual enhancement device such as binoculars or a telescope, ...

, and the likes of John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin, April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was a French-American Autodidacticism, self-trained artist, natural history, naturalist, and ornithology, ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornitho ...

, who instructed Baird on how to draw scientific illustrations of birds. His father was also a big influence on Baird's interest in nature, taking Baird on walks and gardening with him. He died of cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

when Baird was ten years old. As a young boy he attended Nottingham Academy in Port Deposit, Maryland and public school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Carlisle is a Borough (Pennsylvania), borough in and the county seat of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, United States. Carlisle is located within the Cumberland Valley, a highly productive agricultural region. As of the 2020 United States census ...

.

Baird attended Dickinson College

Dickinson College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, United States. Founded in 1773 as Carlisle Grammar School, Dickinson was chartered on September 9, 1783, ...

and earned his bachelor's and master's degrees, finishing the former in 1840. After graduation he moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

with an interest in studying medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

The Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (officially known as Columbia University Roy and Diana Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons) is the medical school of Columbia University, located at the Columbia University Irvin ...

. He returned to Carlisle two years later. He taught natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

at Dickinson starting in 1845. While at Dickinson, he did research, participated in collecting trips, did specimen exchanges with other naturalists, and traveled frequently. He married Mary Helen Churchill in 1846. In 1848, their daughter, Lucy Hunter Baird, was born. He was awarded a grant, in 1848, from the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

to explore bone caves and the natural history of southeastern Pennsylvania. In 1849 he was given $75 by the Smithsonian Institution to collect, pack and transport specimens for them. It was during this time that he met Smithsonian Secretary Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American physicist and inventor who served as the first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor ...

. The two became close friends and colleagues. Throughout the 1840s Baird traveled extensively throughout the northeastern and central United States. Often traveling by foot, Baird hiked more than 2,100 miles in 1842 alone.

Professional career

Starting at the Smithsonian

In 1850, Baird became the first curator at theSmithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

and the Permanent Secretary for the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is a United States–based international nonprofit with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsib ...

, the latter which he served for three years. Upon his arrival in Washington, he brought two railroad box cars worth of his personal collection. Baird created a museum program for the Smithsonian, requesting that the organization focus on natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

in the United States. His program also allowed him to create a network of collectors through an exchange system. He asked that members of the Army and Navy collect rare animals and plant specimens from west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

and the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

. In order to balance the collection, Baird sent duplicate specimens to other museums around the country, often exchanging the duplicates for specimens the Smithsonian needed. During the 1850s he described over 50 new species of reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s, some by himself, and others with his student Charles Frédéric Girard

Charles Frédéric Girard (; 8 March 1822 – 29 January 1895) was a French biologist specializing in ichthyology and herpetology.

Biography

Girard was born on 8 March 1822 in Mulhouse, France. He studied at the College of Neuchâtel, Switzerl ...

. Their 1853 catalog of the Smithsonian's snake collection is a benchmark work in North American herpetology. Baird also was a mentor to herpetologist Robert Kennicott who died prematurely, at which point Baird left the field of herpetology to focus on larger projects.

Eventually, he became the Assistant Secretary, serving under

Eventually, he became the Assistant Secretary, serving under Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American physicist and inventor who served as the first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor ...

. As assistant, Baird helped develop a publication and journal exchange, that provided scientists around the world with publications they would have a hard time accessing. He supported the work of William Stimpson

William Stimpson (February 14, 1832 – May 26, 1872) was an American scientist. He was interested particularly in marine biology. Stimpson became an important early contributor to the work of the Smithsonian Institution and later, director o ...

, Robert Kennicott, Henry Ulke and Henry Bryant. Between his start as Assistant Secretary and 1855, he worked with Joseph Henry to provide scientific equipment and needs to the United States and Mexican Boundary Survey

The United States and Mexican Boundary Survey was a Surveying, land survey that took play from 1848 to 1855 to determine the Mexico–United States border as defined in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the treaty that ended the Mexican–American ...

. In 1855, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

. He received his Ph.D. in physical science

Physical science is a branch of natural science that studies non-living systems, in contrast to life science. It in turn has many branches, each referred to as a "physical science", together is called the "physical sciences".

Definition

...

in 1856 from Dickinson College. In 1857 and 1852 he acquired the collection of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science

The National Institution for the Promotion of Science organization was established in Washington, D.C., in May 1840, and was heir to the mantle of the earlier ''Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences''. The National Institutio ...

. However, the objects did not join the permanent collection of the Smithsonian until 1858. Baird attended the funeral of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

in 1865, alongside Joseph Henry. In 1870, Baird was vacationing in Woods Hole, Massachusetts

Woods Hole is a census-designated place in the town of Falmouth in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States. It lies at the extreme southwestern corner of Cape Cod, near Martha's Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands. The population was 78 ...

, where he developed an interest in maritime research. He went on to lead expeditions in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

and New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

.

United States Fish Commission and United States National Museum

On February 25, 1871,Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

appointed Baird as the first Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries for the United States Fish Commission

The United States Fish Commission, formally known as the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries, was an agency of the United States government created in 1871 to investigate, promote, and preserve the Fishery, fisheries of the United St ...

. He served in this position until his death. With Baird as Commissioner, the commission sought opportunities to restock rivers with salmon

Salmon (; : salmon) are any of several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the genera ''Salmo'' and ''Oncorhynchus'' of the family (biology), family Salmonidae, native ...

and lakes with other food fish and the depletion of food fish

Many species of fish are caught by humans and consumed as food in virtually all regions around the world. Their meat has been an important dietary source of protein and other nutrients in the human diet.

The English language does not have a s ...

in coastal waters. Baird reported that humans were the reason for the decline of food fish in these coastal areas. Individuals with access to shoreline property used weirs, or nets, to capture large amounts of fish on the coast, which threatened the supply of fish on the coast. Baird used the U.S. Fish Commission to limit human impact through a compromise by prohibiting the capture of fish in traps from 6pm on Fridays until 6pm on Mondays. The ''Albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Paci ...

'' research vessel was launched during his tenure, in 1882. He was highly active in developing fishing and fishery

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life or, more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a., fishing grounds). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish far ...

policies for the United States, and was instrumental in making Woods Hole the research venue it is today.

Baird became the manager of the United States National Museum

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

in 1872. Baird told George Perkins Marsh

George Perkins Marsh (March 15, 1801July 23, 1882), an American diplomat and philologist, is considered by some to be America's first environmentalist and by recognizing the irreversible impact of man's actions on the earth, a precursor to the s ...

that he sought to be the director of the National Museum and that he had intentions to expand on the collections within the museum en masse. He was the primary writer of ''A History of North American Birds,'' which was published in 1874 and continues to be an important publication in ornithology

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

today. He created all of the United States federal exhibits in the Centennial Exposition

The Centennial International Exhibition, officially the International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine, was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from May 10 to November 10, 1876. It was the first official wo ...

, many of which won awards. When the exposition ended, Baird was successful in persuading other exhibitors to contribute the objects from their exhibits to the Smithsonian. In total, Baird left with sixty-two boxcar

A boxcar is the North American (Association of American Railroads, AAR) and South Australian Railways term for a Railroad car#Freight cars, railroad car that is enclosed and generally used to carry freight. The boxcar, while not the simpl ...

s filled with 4,000 cartons of objects. Owing to the large number of objects collected, in 1879, Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

approved construction for the first National Museum building, which is now the Arts and Industries Building

The Arts and Industries Building is the second oldest (after The Castle) of the Smithsonian museums on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Initially named the National Museum, it was built to provide the Smithsonian with its first proper faci ...

.

Second Secretary at the Smithsonian

Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American physicist and inventor who served as the first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor ...

died on May 13, 1878 and on May 17, Baird became the second Secretary of the Smithsonian. Baird was allowed to live, rent free, in the Smithsonian Institution Building, but declined and had the east wing converted into workspace. He also had telephone

A telephone, colloquially referred to as a phone, is a telecommunications device that enables two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most ...

s installed throughout the building. That year, he was made a member of the Order of St. Olav

The Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav (; or ''Sanct Olafs Orden'', the old Norwegian name) is a Norwegian order of chivalry instituted by King Oscar I on 21 August 1847. It is named after King Olav II, known to posterity as St. Olav.

Just be ...

by the King of Sweden. In 1880 Baird was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society

The American Antiquarian Society (AAS), located in Worcester, Massachusetts, is both a learned society and a national research library of pre-twentieth-century American history and culture. Founded in 1812, it is the oldest historical society in ...

He oversaw the building of the new National Museum building, which opened in 1881. In September 1883, he was unanimously declared a founding member of the American Ornithologists' Union

The American Ornithological Society (AOS) is an ornithological organization based in the United States. The society was formed in October 2016 by the merger of the American Ornithologists' Union (AOU) and the Cooper Ornithological Society. Its ...

even though his duties prevented him from attending their first convention. During the February 1887, Baird went on leave due to "intellectual exertion". Samuel P. Langley served as Acting Secretary.

Death and legacy

Spencer Fullerton Baird died on August 19, 1887. Upon Baird's death, the Arts and Industries building was draped with a mourning cloth.

Spencer Fullerton Baird died on August 19, 1887. Upon Baird's death, the Arts and Industries building was draped with a mourning cloth. John Wesley Powell

John Wesley Powell (March 24, 1834 – September 23, 1902) was an American geologist, U.S. Army soldier, explorer of the American West, professor at Illinois Wesleyan University, and director of major scientific and cultural institutions. He ...

spoke at Baird's funeral. Baird is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery.

Baird's sparrow, a migratory bird native to Canada, Mexico and the United States, is named after him. A medium-sized shorebird known as Baird's sandpiper

Baird's sandpiper (''Calidris bairdii'') is a small shorebird. It is among those calidrids which were formerly included in the genus ''Erolia'', which was wiktionary:subsume, subsumed into the genus ''Calidris'' in 1973. The genus name is from An ...

is also named after him.

Baird Auditorium in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History is named in his honor. It is located on the National Mall

The National Mall is a Landscape architecture, landscaped park near the Downtown, Washington, D.C., downtown area of Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. It contains and borders a number of museums of the Smithsonian Institu ...

side of the first floor of the museum.

Baird's wife, Mary, donated his stamp collection to the National Museum. His papers are held in the Smithsonian Institution Archives

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is an institutional archives and library system comprising 21 branch libraries serving the various Smithsonian Institution museums and research centers. The Libraries and Archives serve Smithsonian Institution ...

.

In 1946, Baird was one of four Smithsonian Secretaries featured in an exhibition about their lives and work curated by United States National Museum curator Theodore T. Belote. In 1922, the Baird Ornithological Club was founded and named after Baird. Spencer Baird Road in Woods Hole is named for him.

Eponymy

Natural world

*The genus '' Bairdiella'' of drumfishes was named after him byTheodore Gill

Theodore Nicholas Gill (March 21, 1837 – September 25, 1914) was an American ichthyologist, mammalogist, malacologist, and librarian.

Career

Born and educated in New York City under private tutors, Gill early showed interest in natural hist ...

in 1861.

* Baird's smooth-head, ''Alepocephalus bairdii'' Goode and Bean

A bean is the seed of some plants in the legume family (Fabaceae) used as a vegetable for human consumption or animal feed. The seeds are often preserved through drying (a ''pulse''), but fresh beans are also sold. Dried beans are traditi ...

, 1879.

* Lancer dragonet, ''Callionymus bairdi'' Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

, 1888

* Mottled sculpin, ''Cottus bairdii'' Girard, 1850.

* Bumphead damselfish, ''Microspathodon bairdii'' (Gill

A gill () is a respiration organ, respiratory organ that many aquatic ecosystem, aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow r ...

, 1862).

* Marlin-spike grenadier, ''Nezumia bairdii'' ( Goode & Bean

A bean is the seed of some plants in the legume family (Fabaceae) used as a vegetable for human consumption or animal feed. The seeds are often preserved through drying (a ''pulse''), but fresh beans are also sold. Dried beans are traditi ...

, 1877).

* Baird's beaked whale, ''Berardius bairdii'' Stejneger, 1883.

* Baird's pocket gopher, ''Geomys breviceps'' (Baird, 1855)

* Prairie deer mouse, ''Peromyscus maniculatus bairdii'' (Hoy and Kennicott, 1857)

* Baird's shrew, ''Sorex bairdi'' (Meriam, 1895)

*Baird's tapir

The Baird's tapir (''Tapirus bairdii''), also known as the Central American tapir, is a species of tapir native to Mexico, Central America, and northwestern South America. It is the largest of the three species of tapir native to the Americas, a ...

, ''Tapirus bairdii'' (Gill, 1865).

* Baird's sparrow, ''Ammodramus bairdii'' ( Audubon, 1844).

*Baird's sandpiper

Baird's sandpiper (''Calidris bairdii'') is a small shorebird. It is among those calidrids which were formerly included in the genus ''Erolia'', which was wiktionary:subsume, subsumed into the genus ''Calidris'' in 1973. The genus name is from An ...

, ''Calidris bairdii'' Coues, 1861.

* Cuban ivory-billed woodpecker, ''Campephilus bairdii'' (now ''C. principalis bairdii''), Cassin, 1863.

* Baird's flycatcher, ''Myiodynastes bairdii'' Gambell, 1847.

* Baird's trogon, ''Trogon bairdii'' Lawrence, 1868.

*Tanner crab

''Chionoecetes'' is a genus of crabs that live in the northern Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

Common names for crabs in this genus include "queen crab" (in Canada) and " spider crab". The generic name ''Chionoecetes'' means snow (, ') inhabitant ...

, ''Chionoecetes bairdi'' Rathbun, 1924.

* Red lobster, ''Eunephrops bairdii'' S. I. Smith, 1885.

* Baird's rat snake, ''Pantherophis bairdi'' (Yarrow

''Achillea millefolium'', commonly known as yarrow () or common yarrow, is a flowering plant in the family Asteraceae. Growing to tall, it is characterized by small whitish flowers, a tall stem of fernlike leaves, and a pungent odor.

The plan ...

, 1880).

*Baird's patch-nosed snake, '' Salvadora bairdi'' Jan, 1860.Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). ''The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. . ("Baird, S.F.", pp. 14-15).

Author abbreviation in zoology

* BairdSea vessel

*M.V. ''Spencer F. Baird'', Ocean-surveying ship.Locations

*The Lake Shasta Caverns were formerly named Baird Cave.References

Further reading

Publications by Spencer Fullerton Baird

*"Directions for Collecting, Preserving, and Transporting Specimens of Natural History." ''Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year 1856.'' p. 235-253. *with Robert Ridgway and Thomas Mayo Brewer. ''A History Of North American Birds''. *withCharles Frédéric Girard

Charles Frédéric Girard (; 8 March 1822 – 29 January 1895) was a French biologist specializing in ichthyology and herpetology.

Biography

Girard was born on 8 March 1822 in Mulhouse, France. He studied at the College of Neuchâtel, Switzerl ...

. ''Catalogue of North American Reptiles in the Museum of the Smithsonian Institution. Part I.—Serpents.'' Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution. xvi + 172 pp. (1853).

Publications about Baird

*Allard, Dean C. ''Spencer Fullerton Baird and the U. S. Fish Commission: A Study in the History of American Science''. Washington: The George Washington University (1967). *Belote, Theodore T. "The Secretarial Cases." ''Scientific Monthly''. 58 (1946): 366–370. *Cockerell, Theodore D.A. "Spencer Fullerton Baird." ''Popular Science Monthly''. 68 (1906): 63–83. *Dall, William Healey. "Spencer Fullerton Baird: a biography, including selections from his correspondence with Audubon, Agassiz, Dana, and others." Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company (1915). *Goode, G. Brown. ''The Published Writings of Spencer Fullerton Baird, 1843-1882''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office (1883). *Ripley, S. Dillon. "The View From the Castle: Take two freight cars of specimens, add time and energy--eventually you'll get a natural history museum." ''Smithsonian''. 1.11 (1971): 2. *Rivinus, Edward F. and Youssef, Elizabeth M. . ''Spencer F. Baird of the Smithsonian.'' Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press (1992).External links

* * *Spencer F. Baird's Vision for a National Museum

online exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution Archives

from the

National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. With 4.4 ...

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

{{DEFAULTSORT:Baird, John Fullerton 1823 births 1887 deaths 19th-century American naturalists American taxonomists American ichthyologists American ornithologists Dickinson College alumni Secretaries of the Smithsonian Institution United States Fish Commission personnel People from Carlisle, Pennsylvania People from Reading, Pennsylvania Burials at Oak Hill Cemetery (Washington, D.C.) West Nottingham Academy alumni Columbia University alumni 19th-century American zoologists Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Members of the American Philosophical Society