Soviet Press on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a

The Supreme Soviet (successor of the

The Supreme Soviet (successor of the

During his rule, Stalin always made the final policy decisions. Otherwise, Soviet foreign policy was set by the commission on the Foreign Policy of the Central Committee of the

During his rule, Stalin always made the final policy decisions. Otherwise, Soviet foreign policy was set by the commission on the Foreign Policy of the Central Committee of the

The Marxist-Leninist leadership of the Soviet Union intensely debated foreign policy issues and changed directions several times. Even after Stalin assumed dictatorial control in the late 1920s, there were debates, and he frequently changed positions.

During the country's early period, it was assumed that Communist revolutions would break out soon in every major industrial country, and it was the Russian responsibility to assist them. The

The Marxist-Leninist leadership of the Soviet Union intensely debated foreign policy issues and changed directions several times. Even after Stalin assumed dictatorial control in the late 1920s, there were debates, and he frequently changed positions.

During the country's early period, it was assumed that Communist revolutions would break out soon in every major industrial country, and it was the Russian responsibility to assist them. The

Under the Military Law of September 1925, the

Under the Military Law of September 1925, the

The Soviet Union adopted a

The Soviet Union adopted a  By the early 1940s, the Soviet economy had become relatively self-sufficient; for most of the period until the creation of

By the early 1940s, the Soviet economy had become relatively self-sufficient; for most of the period until the creation of  From the 1930s until its dissolution in late 1991, the way the Soviet economy operated remained essentially unchanged. The economy was formally directed by

From the 1930s until its dissolution in late 1991, the way the Soviet economy operated remained essentially unchanged. The economy was formally directed by  Although statistics of the Soviet economy are notoriously unreliable and its economic growth difficult to estimate precisely, by most accounts, the economy continued to expand until the mid-1980s. During the 1950s and 1960s, it had comparatively high growth and was catching up to the West. However, after 1970, the growth, while still positive, Era of Stagnation, steadily declined much more quickly and consistently than in other countries, despite a rapid increase in the capital stock (the rate of capital increase was only surpassed by Japan).

Overall, the growth rate of per capita income in the Soviet Union between 1960 and 1989 was slightly above the world average (based on 102 countries). A 1986 study published in the ''American Journal of Public Health'' claimed that, citing World Bank data, the Soviet model provided a better quality of life and Human development (economics), human development than market economies at the same level of economic development in most cases. According to Stanley Fischer and William Easterly, growth could have been faster. By their calculation, per capita income in 1989 should have been twice higher than it was, considering the amount of investment, education and population. The authors attribute this poor performance to the low productivity of capital. Steven Rosefielde states that the standard of living declined due to Stalin's despotism. While there was a brief improvement after his death, it lapsed into stagnation.

In 1987,

Although statistics of the Soviet economy are notoriously unreliable and its economic growth difficult to estimate precisely, by most accounts, the economy continued to expand until the mid-1980s. During the 1950s and 1960s, it had comparatively high growth and was catching up to the West. However, after 1970, the growth, while still positive, Era of Stagnation, steadily declined much more quickly and consistently than in other countries, despite a rapid increase in the capital stock (the rate of capital increase was only surpassed by Japan).

Overall, the growth rate of per capita income in the Soviet Union between 1960 and 1989 was slightly above the world average (based on 102 countries). A 1986 study published in the ''American Journal of Public Health'' claimed that, citing World Bank data, the Soviet model provided a better quality of life and Human development (economics), human development than market economies at the same level of economic development in most cases. According to Stanley Fischer and William Easterly, growth could have been faster. By their calculation, per capita income in 1989 should have been twice higher than it was, considering the amount of investment, education and population. The authors attribute this poor performance to the low productivity of capital. Steven Rosefielde states that the standard of living declined due to Stalin's despotism. While there was a brief improvement after his death, it lapsed into stagnation.

In 1987,

The need for fuel declined in the Soviet Union from the 1970s to the 1980s, both per ruble of gross social product and per ruble of industrial product. At the start, this decline grew very rapidly but gradually slowed down between 1970 and 1975. From 1975 and 1980, it grew even slower, only 2.6%. David Wilson, a historian, believed that the gas industry would account for 40% of Soviet fuel production by the end of the century. His theory did not come to fruition because of the USSR's collapse. The USSR, in theory, would have continued to have an economic growth rate of 2–2.5% during the 1990s because of Soviet energy fields. However, the energy sector faced many difficulties, among them the country's high military expenditure and hostile relations with the First World.

In 1991, the Soviet Union had a pipeline network of for crude oil and another for natural gas. Petroleum and petroleum-based products, natural gas, metals, wood, agricultural products, and a variety of manufactured goods, primarily machinery, arms and military equipment, were exported. In the 1970s and 1980s, the USSR heavily relied on fossil fuel exports to earn hard currency. At its peak in 1988, it was the largest producer and second-largest exporter of crude oil, surpassed only by Saudi Arabia.

The need for fuel declined in the Soviet Union from the 1970s to the 1980s, both per ruble of gross social product and per ruble of industrial product. At the start, this decline grew very rapidly but gradually slowed down between 1970 and 1975. From 1975 and 1980, it grew even slower, only 2.6%. David Wilson, a historian, believed that the gas industry would account for 40% of Soviet fuel production by the end of the century. His theory did not come to fruition because of the USSR's collapse. The USSR, in theory, would have continued to have an economic growth rate of 2–2.5% during the 1990s because of Soviet energy fields. However, the energy sector faced many difficulties, among them the country's high military expenditure and hostile relations with the First World.

In 1991, the Soviet Union had a pipeline network of for crude oil and another for natural gas. Petroleum and petroleum-based products, natural gas, metals, wood, agricultural products, and a variety of manufactured goods, primarily machinery, arms and military equipment, were exported. In the 1970s and 1980s, the USSR heavily relied on fossil fuel exports to earn hard currency. At its peak in 1988, it was the largest producer and second-largest exporter of crude oil, surpassed only by Saudi Arabia.

The Soviet Union placed great emphasis on Science and technology in the Soviet Union, science and technology. Lenin believed the USSR would never overtake the developed world if it remained as technologically backward as it was upon its founding. Soviet authorities proved their commitment to Lenin's belief by developing massive networks and research and development organizations. In the early 1960s, 40% of chemistry PhDs in the Soviet Union were attained by women, compared with only 5% in the United States. By 1989, Soviet scientists were among the world's best-trained specialists in several areas, such as energy physics, selected areas of medicine, mathematics, welding, space technology, and military technologies. However, due to rigid state planning and Nomenklatura, bureaucracy, the Soviets remained far behind the First World in chemistry, biology, and computer science. Under Stalin, the Soviet government persecuted geneticists in favour of Lysenkoism, a pseudoscience rejected by the scientific community in the Soviet Union and abroad but supported by Stalin's inner circles. Implemented in the USSR and China, it resulted in reduced crop yields and is widely believed to have contributed to the Great Chinese Famine. In the 1980s, the Soviet Union had more scientists and engineers relative to the world's population than any other major country, owing to strong levels of state support. Some of its most remarkable technological achievements, such as launching the Sputnik 1, world's first space satellite, were achieved through military research.

Under the Reagan administration, Project Socrates determined that the Soviet Union addressed the acquisition of science and technology in a manner radically different to the United States. The US prioritized indigenous research and development in both the public and private sectors. In contrast, the USSR placed greater emphasis on acquiring foreign technology, which it did through both Industrial espionage, covert and overt means. However, centralized state planning kept Soviet technological development greatly inflexible. This was exploited by the US to undermine the strength of the Soviet Union and thus foster its reform.

The Soviet Union placed great emphasis on Science and technology in the Soviet Union, science and technology. Lenin believed the USSR would never overtake the developed world if it remained as technologically backward as it was upon its founding. Soviet authorities proved their commitment to Lenin's belief by developing massive networks and research and development organizations. In the early 1960s, 40% of chemistry PhDs in the Soviet Union were attained by women, compared with only 5% in the United States. By 1989, Soviet scientists were among the world's best-trained specialists in several areas, such as energy physics, selected areas of medicine, mathematics, welding, space technology, and military technologies. However, due to rigid state planning and Nomenklatura, bureaucracy, the Soviets remained far behind the First World in chemistry, biology, and computer science. Under Stalin, the Soviet government persecuted geneticists in favour of Lysenkoism, a pseudoscience rejected by the scientific community in the Soviet Union and abroad but supported by Stalin's inner circles. Implemented in the USSR and China, it resulted in reduced crop yields and is widely believed to have contributed to the Great Chinese Famine. In the 1980s, the Soviet Union had more scientists and engineers relative to the world's population than any other major country, owing to strong levels of state support. Some of its most remarkable technological achievements, such as launching the Sputnik 1, world's first space satellite, were achieved through military research.

Under the Reagan administration, Project Socrates determined that the Soviet Union addressed the acquisition of science and technology in a manner radically different to the United States. The US prioritized indigenous research and development in both the public and private sectors. In contrast, the USSR placed greater emphasis on acquiring foreign technology, which it did through both Industrial espionage, covert and overt means. However, centralized state planning kept Soviet technological development greatly inflexible. This was exploited by the US to undermine the strength of the Soviet Union and thus foster its reform.

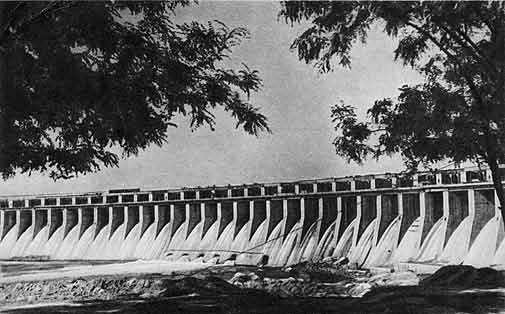

Transport was a vital component of the country's economy. The First five-year plan (Soviet Union), economic centralization of the late 1920s and 1930s led to the development of infrastructure on a massive scale, most notably the establishment of Aeroflot, an aviation enterprise. The country had a wide variety of modes of transport by land, water and air. However, due to inadequate maintenance, much of the road, water and Soviet civil aviation transport were outdated and technologically backward compared to the First World.

Soviet rail transport was the largest and most intensively used in the world; it was also better developed than most of its Western counterparts. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Soviet economists were calling for the construction of more roads to alleviate some of the burdens from the railways and to improve the Soviet

Transport was a vital component of the country's economy. The First five-year plan (Soviet Union), economic centralization of the late 1920s and 1930s led to the development of infrastructure on a massive scale, most notably the establishment of Aeroflot, an aviation enterprise. The country had a wide variety of modes of transport by land, water and air. However, due to inadequate maintenance, much of the road, water and Soviet civil aviation transport were outdated and technologically backward compared to the First World.

Soviet rail transport was the largest and most intensively used in the world; it was also better developed than most of its Western counterparts. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Soviet economists were calling for the construction of more roads to alleviate some of the burdens from the railways and to improve the Soviet

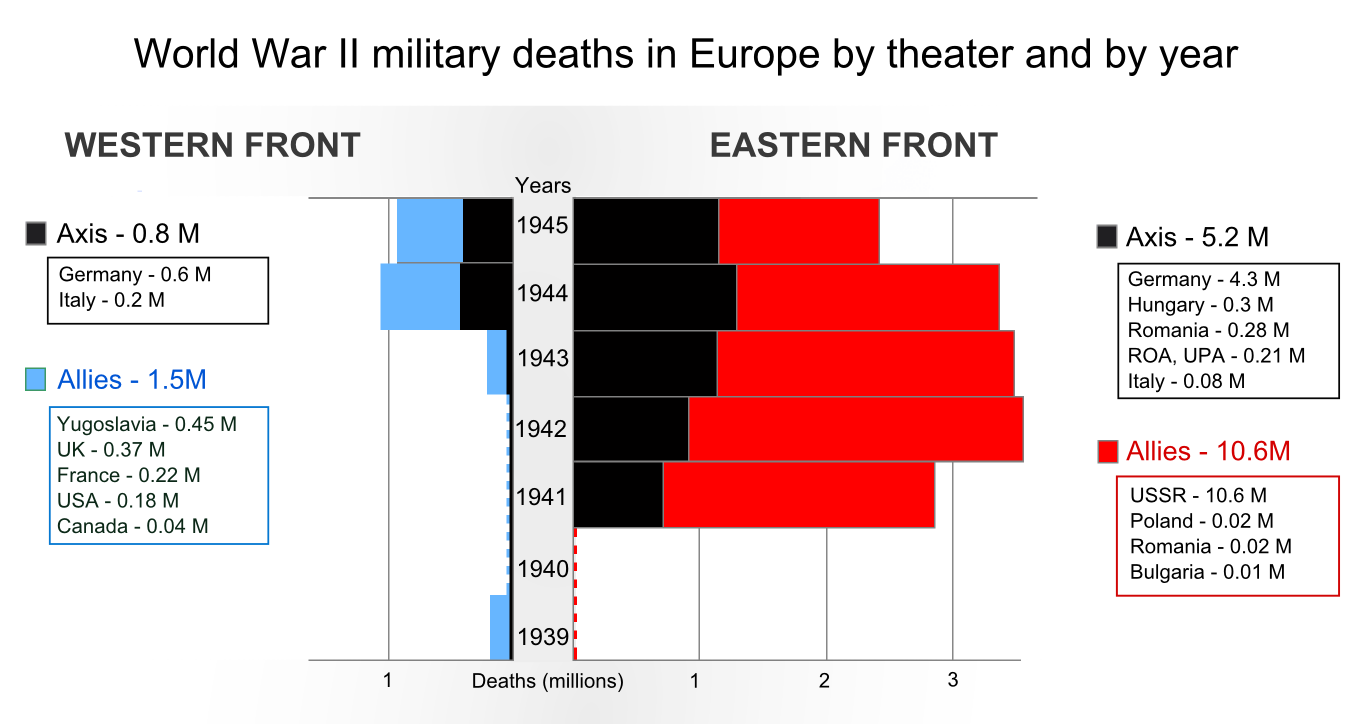

Excess deaths throughout World War I and the

Excess deaths throughout World War I and the

The Soviet Union imposed heavy control on city growth, preventing some cities from reaching their full potential while promoting others.

For the entirety of its existence, the most populous cities were

The Soviet Union imposed heavy control on city growth, preventing some cities from reaching their full potential while promoting others.

For the entirety of its existence, the most populous cities were

Under Lenin, the state made explicit commitments to promote the equality of men and women. Many early Russian feminists and ordinary Russian working women actively participated in the Revolution, and many more were affected by the events of that period and the new policies. Beginning in October 1918, Lenin's government liberalized divorce and abortion laws, decriminalized homosexuality (re-criminalized in 1932), permitted cohabitation, and ushered in a host of reforms. However, without birth control, the new system produced many broken marriages, as well as countless out-of-wedlock children. The epidemic of divorces and extramarital affairs created social hardships when Soviet leaders wanted people to concentrate their efforts on growing the economy. Giving women control over their fertility also led to a precipitous decline in the birth rate, perceived as a threat to their country's military power. By 1936, Stalin reversed most of the liberal laws, ushering in a Natalism, pronatalist era that lasted for decades.

By 1917, Russia became the first great power to grant women the right to vote. After heavy casualties in World Wars I and II, women outnumbered men in Russia by a 4:3 ratio; this contributed to the larger role women played in Russian society compared to other great powers at the time.

Under Lenin, the state made explicit commitments to promote the equality of men and women. Many early Russian feminists and ordinary Russian working women actively participated in the Revolution, and many more were affected by the events of that period and the new policies. Beginning in October 1918, Lenin's government liberalized divorce and abortion laws, decriminalized homosexuality (re-criminalized in 1932), permitted cohabitation, and ushered in a host of reforms. However, without birth control, the new system produced many broken marriages, as well as countless out-of-wedlock children. The epidemic of divorces and extramarital affairs created social hardships when Soviet leaders wanted people to concentrate their efforts on growing the economy. Giving women control over their fertility also led to a precipitous decline in the birth rate, perceived as a threat to their country's military power. By 1936, Stalin reversed most of the liberal laws, ushering in a Natalism, pronatalist era that lasted for decades.

By 1917, Russia became the first great power to grant women the right to vote. After heavy casualties in World Wars I and II, women outnumbered men in Russia by a 4:3 ratio; this contributed to the larger role women played in Russian society compared to other great powers at the time.

Anatoly Lunacharsky became the first People's Commissar for Education of Soviet Russia. In the beginning, the Soviet authorities placed great emphasis on the Likbez, elimination of illiteracy. All left-handed children were forced to write with their right hand in the Soviet school system. Literate people were automatically hired as teachers. For a short period, quality was sacrificed for quantity. By 1940, Stalin could announce that illiteracy had been eliminated. Throughout the 1930s, social mobility rose sharply, which has been attributed to reforms in education. In the aftermath of World War II, the country's educational system expanded dramatically, which had a tremendous effect. In the 1960s, nearly all children had access to education, the only exception being those living in remote areas.

Anatoly Lunacharsky became the first People's Commissar for Education of Soviet Russia. In the beginning, the Soviet authorities placed great emphasis on the Likbez, elimination of illiteracy. All left-handed children were forced to write with their right hand in the Soviet school system. Literate people were automatically hired as teachers. For a short period, quality was sacrificed for quantity. By 1940, Stalin could announce that illiteracy had been eliminated. Throughout the 1930s, social mobility rose sharply, which has been attributed to reforms in education. In the aftermath of World War II, the country's educational system expanded dramatically, which had a tremendous effect. In the 1960s, nearly all children had access to education, the only exception being those living in remote areas.

The Soviet Union was an ethnically diverse country, with more than 100 distinct ethnic groups. The total population of the country was estimated at 293 million in 1991. According to a 1990 estimate, the majority of the population were

The Soviet Union was an ethnically diverse country, with more than 100 distinct ethnic groups. The total population of the country was estimated at 293 million in 1991. According to a 1990 estimate, the majority of the population were

File:Ethnic map USSR 1930.jpg, Ethnographic map of the USSR, 1930

File:European Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) Ethnic Groups (Before 1939) - DPLA - 9820cc06b72e7b131366b861f5ee351a.jpg, European Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) Ethnic Groups, before 1939

File:Ethnic map USSR 1941.jpg, Ethnographic map of the Soviet Union, 1941

File:U.S. S.R. - Ethnic Compositions - DPLA - 754227d4ec980a6b169104b656de499a.jpg, Ethnic composition of the Soviet Union in 1949

File:Map of the ethnic groups of the Soviet Union.png, Ethnographic map of the Soviet Union, 1970

File:French map of the ethnic groups living in USSR.png, Map of the ethnic groups living in USSR, 1970

File:Ethnic Groups in the Soviet Union - DPLA - d7a6475bd436c74e2b67e621a6b2afad.jpg, Ethnic Groups in the Soviet Union, 1979

File:Comparative Soviet Nationalities by Republic, 1989 - DPLA - 23930ee870e66bd2efa5417463128b28.jpg, Comparative Soviet Nationalities by Republic, 1989

In 1917, before the revolution, health conditions were significantly behind those of developed countries. As Lenin later noted, "Either the lice will defeat socialism, or socialism will defeat the lice". The Soviet health care system was conceived by the People's Commissariat for Health in 1918. Under the Semashko model, health care was to be controlled by the state and would be provided to its citizens free of charge, a revolutionary concept at the time. Article 42 of the 1977 Soviet Constitution gave all citizens the right to health protection and free access to any health institutions in the USSR. Before

In 1917, before the revolution, health conditions were significantly behind those of developed countries. As Lenin later noted, "Either the lice will defeat socialism, or socialism will defeat the lice". The Soviet health care system was conceived by the People's Commissariat for Health in 1918. Under the Semashko model, health care was to be controlled by the state and would be provided to its citizens free of charge, a revolutionary concept at the time. Article 42 of the 1977 Soviet Constitution gave all citizens the right to health protection and free access to any health institutions in the USSR. Before

Christianity and Islam had the highest number of adherents among the religious citizens. Eastern Christianity predominated among Christians, with Russia's traditional Russian Orthodox Church being the largest Christian denomination. About 90% of the Soviet Union's Muslims were Sunnis, with Shias being concentrated in the Azerbaijan SSR. Smaller groups included Roman Catholics, Jews, Buddhists, and a variety of Protestant denominations (especially Baptists and Lutherans).

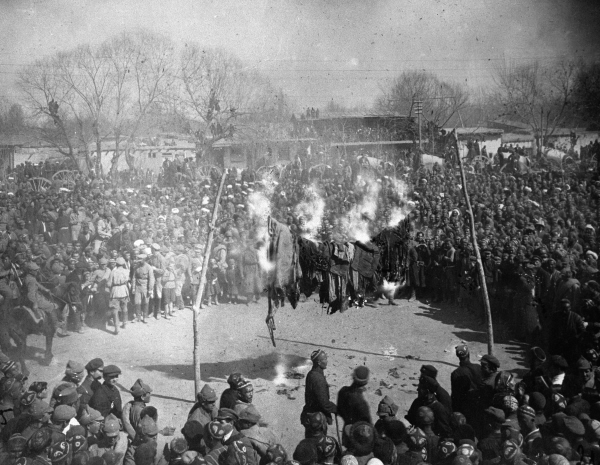

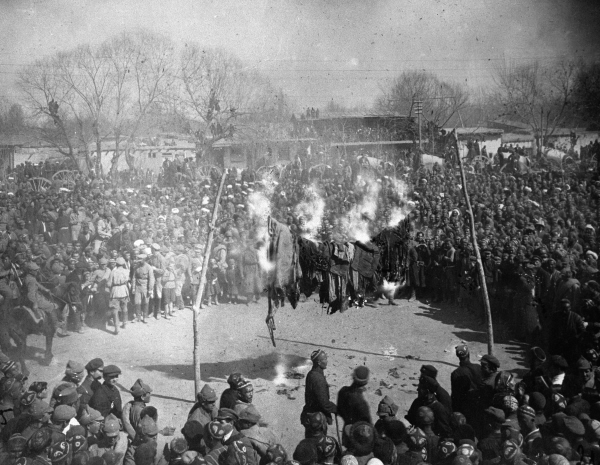

Religious influence had been strong in the Russian Empire. The Russian Orthodox Church enjoyed a privileged status as the church of the monarchy and took part in carrying out official state functions. The immediate period following the establishment of the Soviet state included a struggle against the Orthodox Church, which the revolutionaries considered an ally of the former ruling classes.

In Soviet law, the 'freedom to hold religious services' was constitutionally guaranteed, although the ruling Communist Party regarded religion as incompatible with the Marxist spirit of scientific materialism. In practice, the Soviet system subscribed to a narrow interpretation of this right, and in fact used a range of official measures to discourage religion and curb the activities of religious groups.

The 1918 Council of People's Commissars decree establishing the Russian SFSR as a secular state also decreed that 'the teaching of religion in all [places] where subjects of general instruction are taught, is forbidden. Citizens may teach and may be taught religion privately.' Among further restrictions, those adopted in 1929 included express prohibitions on a range of church activities, including meetings for organized Bible study (Christian), Bible study. Both Christian and non-Christian establishments were shut down by the thousands in the 1920s and 1930s. By 1940, as many as 90% of the churches, synagogues, and mosques that had been operating in 1917 were closed; the majority of them were demolished or re-purposed for state needs with little concern for their historic and cultural value.

More than 85,000 Orthodox priests were shot in 1937 alone. Only a twelfth of the Russian Orthodox Church's priests were left functioning in their parishes by 1941. In the period between 1927 and 1940, the number of Orthodox Churches in Russia fell from 29,584 to less than 500 (1.7%).

The Soviet Union was officially a secular state, but a 'government-sponsored program of forced conversion to Marxist-Leninist atheism, atheism' was conducted under the doctrine of state atheism. The government targeted religions based on state interests, and while most organized religions were never outlawed, religious property was confiscated, believers were harassed, and religion was ridiculed while atheism was propagated in schools. In 1925, the government founded the League of Militant Atheists to intensify the propaganda campaign. Accordingly, although personal expressions of religious faith were not explicitly banned, a strong sense of social stigma was imposed on them by the formal structures and mass media, and it was generally considered unacceptable for members of certain professions (teachers, state bureaucrats, soldiers) to be openly religious. While persecution accelerated following Stalin's rise to power, a revival of Orthodoxy was fostered by the government during World War II and the Soviet authorities sought to control the Russian Orthodox Church rather than liquidate it. During the first five years of Soviet power, the Bolsheviks executed 28 Russian Orthodox bishops and over 1,200 Russian Orthodox priests. Many others were imprisoned or exiled. Believers were harassed and persecuted. Most seminaries were closed, and the publication of most religious material was prohibited. By 1941, only 500 churches remained open out of about 54,000 in existence before World War I.

Convinced that religious anti-Sovietism had become a thing of the past, and with the looming threat of war, the Stalin administration began shifting to a more moderate religion policy in the late 1930s. Soviet religious establishments overwhelmingly rallied to support the war effort during World War II. Amid other accommodations to religious faith after the German invasion, churches were reopened. Radio Moscow began broadcasting a religious hour, and a historic meeting between Stalin and Orthodox Church leader Patriarch Sergius of Moscow was held in 1943. Stalin had the support of the majority of the religious people in the USSR even through the late 1980s. The general tendency of this period was an increase in religious activity among believers of all faiths.

Under

Christianity and Islam had the highest number of adherents among the religious citizens. Eastern Christianity predominated among Christians, with Russia's traditional Russian Orthodox Church being the largest Christian denomination. About 90% of the Soviet Union's Muslims were Sunnis, with Shias being concentrated in the Azerbaijan SSR. Smaller groups included Roman Catholics, Jews, Buddhists, and a variety of Protestant denominations (especially Baptists and Lutherans).

Religious influence had been strong in the Russian Empire. The Russian Orthodox Church enjoyed a privileged status as the church of the monarchy and took part in carrying out official state functions. The immediate period following the establishment of the Soviet state included a struggle against the Orthodox Church, which the revolutionaries considered an ally of the former ruling classes.

In Soviet law, the 'freedom to hold religious services' was constitutionally guaranteed, although the ruling Communist Party regarded religion as incompatible with the Marxist spirit of scientific materialism. In practice, the Soviet system subscribed to a narrow interpretation of this right, and in fact used a range of official measures to discourage religion and curb the activities of religious groups.

The 1918 Council of People's Commissars decree establishing the Russian SFSR as a secular state also decreed that 'the teaching of religion in all [places] where subjects of general instruction are taught, is forbidden. Citizens may teach and may be taught religion privately.' Among further restrictions, those adopted in 1929 included express prohibitions on a range of church activities, including meetings for organized Bible study (Christian), Bible study. Both Christian and non-Christian establishments were shut down by the thousands in the 1920s and 1930s. By 1940, as many as 90% of the churches, synagogues, and mosques that had been operating in 1917 were closed; the majority of them were demolished or re-purposed for state needs with little concern for their historic and cultural value.

More than 85,000 Orthodox priests were shot in 1937 alone. Only a twelfth of the Russian Orthodox Church's priests were left functioning in their parishes by 1941. In the period between 1927 and 1940, the number of Orthodox Churches in Russia fell from 29,584 to less than 500 (1.7%).

The Soviet Union was officially a secular state, but a 'government-sponsored program of forced conversion to Marxist-Leninist atheism, atheism' was conducted under the doctrine of state atheism. The government targeted religions based on state interests, and while most organized religions were never outlawed, religious property was confiscated, believers were harassed, and religion was ridiculed while atheism was propagated in schools. In 1925, the government founded the League of Militant Atheists to intensify the propaganda campaign. Accordingly, although personal expressions of religious faith were not explicitly banned, a strong sense of social stigma was imposed on them by the formal structures and mass media, and it was generally considered unacceptable for members of certain professions (teachers, state bureaucrats, soldiers) to be openly religious. While persecution accelerated following Stalin's rise to power, a revival of Orthodoxy was fostered by the government during World War II and the Soviet authorities sought to control the Russian Orthodox Church rather than liquidate it. During the first five years of Soviet power, the Bolsheviks executed 28 Russian Orthodox bishops and over 1,200 Russian Orthodox priests. Many others were imprisoned or exiled. Believers were harassed and persecuted. Most seminaries were closed, and the publication of most religious material was prohibited. By 1941, only 500 churches remained open out of about 54,000 in existence before World War I.

Convinced that religious anti-Sovietism had become a thing of the past, and with the looming threat of war, the Stalin administration began shifting to a more moderate religion policy in the late 1930s. Soviet religious establishments overwhelmingly rallied to support the war effort during World War II. Amid other accommodations to religious faith after the German invasion, churches were reopened. Radio Moscow began broadcasting a religious hour, and a historic meeting between Stalin and Orthodox Church leader Patriarch Sergius of Moscow was held in 1943. Stalin had the support of the majority of the religious people in the USSR even through the late 1980s. The general tendency of this period was an increase in religious activity among believers of all faiths.

Under

In summer of 1923 in Moscow was established the Dynamo Sports Club, Proletarian Sports Society "Dynamo" as a sports organization of Soviet secret police Cheka.

On 13 July 1925 the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) adopted a statement "About the party's tasks in sphere of physical culture". In the statement was determined the role of physical culture in Soviet society and the party's tasks in political leadership of physical culture movement in the country.

The Soviet Olympic Committee formed on 21 April 1951, and the IOC recognized the new body in its List of IOC meetings, 45th session. In the same year, when the Soviet representative Konstantin Andrianov became an IOC member, the USSR officially joined the Olympic Movement. The 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki thus became first Olympic Games for Soviet athletes. The Soviet Union was the biggest rival to the United States at the Summer Olympics, winning Soviet Union at the Olympics#Medals by Summer Games, six of its nine appearances at the games and also topping the medal tally at the Winter Olympics six times. The Soviet Union's Olympics success has been attributed to its large investment in sports to demonstrate its superpower image and political influence on a global stage.

The Soviet Union national ice hockey team won nearly every Ice Hockey World Championships, world championship and Ice hockey at the Olympic Games, Olympic tournament between 1954 and 1991 and never failed to medal in any International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) tournament in which they competed.

Soviet Olympic team was notorious for skirting the edge of amateur rules. All Soviet athletes held some nominal jobs, but were in fact state-sponsored and trained full-time. According to many experts, that gave the Soviet Union a huge advantage over the

In summer of 1923 in Moscow was established the Dynamo Sports Club, Proletarian Sports Society "Dynamo" as a sports organization of Soviet secret police Cheka.

On 13 July 1925 the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) adopted a statement "About the party's tasks in sphere of physical culture". In the statement was determined the role of physical culture in Soviet society and the party's tasks in political leadership of physical culture movement in the country.

The Soviet Olympic Committee formed on 21 April 1951, and the IOC recognized the new body in its List of IOC meetings, 45th session. In the same year, when the Soviet representative Konstantin Andrianov became an IOC member, the USSR officially joined the Olympic Movement. The 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki thus became first Olympic Games for Soviet athletes. The Soviet Union was the biggest rival to the United States at the Summer Olympics, winning Soviet Union at the Olympics#Medals by Summer Games, six of its nine appearances at the games and also topping the medal tally at the Winter Olympics six times. The Soviet Union's Olympics success has been attributed to its large investment in sports to demonstrate its superpower image and political influence on a global stage.

The Soviet Union national ice hockey team won nearly every Ice Hockey World Championships, world championship and Ice hockey at the Olympic Games, Olympic tournament between 1954 and 1991 and never failed to medal in any International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) tournament in which they competed.

Soviet Olympic team was notorious for skirting the edge of amateur rules. All Soviet athletes held some nominal jobs, but were in fact state-sponsored and trained full-time. According to many experts, that gave the Soviet Union a huge advantage over the

The legacy of the USSR remains a controversial topic. The socio-economic nature of

The legacy of the USSR remains a controversial topic. The socio-economic nature of  Western academicians published various analyses of the post-Soviet states' development, claiming that the dissolution was followed by a severe drop in economic and social conditions in these countries, including a rapid increase in poverty, crime, corruption, unemployment, homelessness, rates of disease, infant mortality and domestic violence, as well as demographic losses, income inequality and the rise of an Russian oligarchs, oligarchical class, along with decreases in calorie intake, life expectancy, adult literacy, and income. Between 1988 and 1989 and 1993–1995, the Gini ratio increased by an average of 9 points for all former Soviet republics. According to Western analysis, the economic shocks that accompanied wholesale privatization were associated with sharp increases in mortality, Russia, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia saw a tripling of unemployment and a 42% increase in male death rates between 1991 and 1994, and in the following decades, only five or six of the post-communist states are on a path to joining the wealthy capitalist West while most are falling behind, some to such an extent that it will take over fifty years to catch up to where they were before the fall of the Soviet Bloc. However, virtually all the former Soviet republics were able to turn their economies around and increase GDP to multiple times what it was under the USSR, though with large wealth disparities, and many post-soviet economies described as oligarchic.

Since the

Western academicians published various analyses of the post-Soviet states' development, claiming that the dissolution was followed by a severe drop in economic and social conditions in these countries, including a rapid increase in poverty, crime, corruption, unemployment, homelessness, rates of disease, infant mortality and domestic violence, as well as demographic losses, income inequality and the rise of an Russian oligarchs, oligarchical class, along with decreases in calorie intake, life expectancy, adult literacy, and income. Between 1988 and 1989 and 1993–1995, the Gini ratio increased by an average of 9 points for all former Soviet republics. According to Western analysis, the economic shocks that accompanied wholesale privatization were associated with sharp increases in mortality, Russia, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia saw a tripling of unemployment and a 42% increase in male death rates between 1991 and 1994, and in the following decades, only five or six of the post-communist states are on a path to joining the wealthy capitalist West while most are falling behind, some to such an extent that it will take over fifty years to catch up to where they were before the fall of the Soviet Bloc. However, virtually all the former Soviet republics were able to turn their economies around and increase GDP to multiple times what it was under the USSR, though with large wealth disparities, and many post-soviet economies described as oligarchic.

Since the

Impressions of Soviet Russia

by John Dewey

A Country Study: Soviet Union

(PDF) {{Authority control Soviet Union, States and territories established in 1922 States and territories disestablished in 1991 20th century in Russia Early Soviet republics, Communism in Russia Former countries in Europe Former countries in West Asia Former countries in Central Asia Former socialist republics Historical transcontinental empires Countries and territories where Russian is an official language

transcontinental country

This is a list of countries with territory that straddles more than one continent, known as transcontinental states or intercontinental states.

Contiguous transcontinental countries are states that have one continuous or immediately-adjacent pie ...

that spanned much of Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

from 1922 until it dissolved in 1991. During its existence, it was the largest country by area, extending across eleven time zones and sharing borders with twelve countries, and the third-most populous country. An overall successor to the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, it was nominally organized as a federal union

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governing status of the co ...

of national republics, the largest and most populous of which was the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

. In practice, its government and economy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

were highly centralized. As a one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

governed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

(CPSU), it was a flagship communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state in which the totality of the power belongs to a party adhering to some form of Marxism–Leninism, a branch of the communist ideology. Marxism–Leninism was ...

. Its capital and largest city was Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

.

The Soviet Union's roots lay in the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

of 1917. The new government, led by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, established the Russian SFSR, the world's first constitutionally communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state in which the totality of the power belongs to a party adhering to some form of Marxism–Leninism, a branch of the communist ideology. Marxism–Leninism was ...

. The revolution was not accepted by all within the Russian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federative Republic in the 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territory of the former Russian Empire after its proclamation by the Rus ...

, resulting in the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

. The Russian SFSR and its subordinate republics were merged into the Soviet Union in 1922. Following Lenin's death in 1924, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

came to power, inaugurating rapid industrialization and forced collectivization that led to significant economic growth but contributed to a famine between 1930 and 1933 that killed millions. The Soviet forced labour camp system of the Gulag

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

was expanded. During the late 1930s, Stalin's government conducted the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

to remove opponents, resulting in mass death, imprisonment, and deportation. In 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

signed a non-aggression pact, but in 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along a ...

in the largest land invasion in history, opening the Eastern Front of World War II

The Eastern Front, also known as the Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and its successor states, and the German–Soviet War in modern Germany and Ukraine, was a theatre of World War II fought between the European Axis powers and Al ...

. The Soviets played a decisive role in defeating the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

, suffering an estimated 27 million casualties, which accounted for most Allied losses. In the aftermath of the war, the Soviet Union consolidated the territory occupied by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

, forming satellite states

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting a larger ob ...

, and undertook rapid economic development which cemented its status as a superpower

Superpower describes a sovereign state or supranational union that holds a dominant position characterized by the ability to Sphere of influence, exert influence and Power projection, project power on a global scale. This is done through the comb ...

.

Geopolitical tensions with the United States led to the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. The American-led Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Capitalist Bloc, the Freedom Bloc, the Free Bloc, and the American Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War (1947–1991). While ...

coalesced into NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

in 1949, prompting the Soviet Union to form its own military alliance, the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

, in 1955. Neither side engaged in direct military confrontation, and instead fought on an ideological basis and through proxy war

In political science, a proxy war is an armed conflict where at least one of the belligerents is directed or supported by an external third-party power. In the term ''proxy war'', a belligerent with external support is the ''proxy''; both bel ...

s. In 1953, following Stalin's death

Joseph Stalin, second leader of the Soviet Union, died on 5 March 1953 at his Kuntsevo Dacha after suffering a stroke, at age 74. He was given a state funeral in Moscow on 9 March, with four days of national mourning declared. On the day of t ...

, the Soviet Union undertook a campaign of de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

under Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

, which saw reversals and rejections of Stalinist policies. This campaign caused tensions with Communist China. During the 1950s, the Soviet Union expanded its efforts in space exploration and took a lead in the Space Race

The Space Race (, ) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between t ...

with the first artificial satellite

Sputnik 1 (, , ''Satellite 1''), sometimes referred to as simply Sputnik, was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program ...

, the first human spaceflight, the first space station, and the first probe to land on another planet. In 1985, the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

, sought to reform the country through his policies of ''glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

'' and ''perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

''. In 1989, various countries of the Warsaw Pact overthrew their Soviet-backed regimes, and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

and separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, regional, governmental, or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seekin ...

movements erupted across the Soviet Union. In 1991, amid efforts to preserve the country as a renewed federation, an attempted coup against Gorbachev by hardline communists prompted the largest republics—Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus—to secede. On 26 December, Gorbachev officially recognized the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

. Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin (1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician and statesman who served as President of Russia from 1991 to 1999. He was a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) from 1961 to ...

, the leader of the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

, oversaw its reconstitution into the Russian Federation

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, which became the Soviet Union's successor state; all other republics emerged as fully independent post-Soviet states

The post-Soviet states, also referred to as the former Soviet Union or the former Soviet republics, are the independent sovereign states that emerged/re-emerged from the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Prior to their independence, they ...

.

During its existence, the Soviet Union produced many significant social and technological achievements and innovations. It had the world's second-largest economy and largest standing military. An NPT-designated state, it wielded the largest arsenal of nuclear weapons in the world. As an Allied nation, it was a founding member of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

as well as one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

. Before its dissolution, the Soviet Union was one of the world's two superpowers through its hegemony in Eastern Europe, global diplomatic and ideological influence (particularly in the Global South

Global North and Global South are terms that denote a method of grouping countries based on their defining characteristics with regard to socioeconomics and politics. According to UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the Global South broadly com ...

), military and economic strengths, and scientific

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

accomplishments.

Etymology

The word ''soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

'' is derived from the Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

word (), meaning 'council', 'assembly', 'advice', ultimately deriving from the proto-Slavic

Proto-Slavic (abbreviated PSl., PS.; also called Common Slavic or Common Slavonic) is the unattested, reconstructed proto-language of all Slavic languages. It represents Slavic speech approximately from the 2nd millennium BC through the 6th ...

verbal stem of ('to inform'), related to Slavic ('news'), English ''wise''. The word ''sovietnik'' means 'councillor'. Some organizations in Russian history were called ''council'' (). In the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, the State Council, which functioned from 1810 to 1917, was referred to as a Council of Ministers.

The soviets as workers' council

A workers' council, also called labour council, is a type of council in a workplace or a locality made up of workers or of temporary and instantly revocable delegates elected by the workers in a locality's workplaces. In such a system of polit ...

s first appeared during the 1905 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, th ...

. Although they were quickly suppressed by the Imperial army, after the February Revolution of 1917

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of two revolutions which took place in Russia in 1917.

The main ...

, workers' and soldiers' soviets emerged throughout the country and shared power with the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Empire and Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II on 2 March, O.S. New_Style.html" ;"title="5 ...

. The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, demanded that all power be transferred to the soviets, and gained support from the workers and soldiers. After the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, in which the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

seized power from the Provisional Government in the name of the soviets, Lenin proclaimed the formation of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic (RSFSR).

During the Georgian Affair of 1922, Lenin called for the Russian SFSR and other national soviet republics to form a greater union which he initially named as the Union of Soviet Republics of Europe and Asia (). Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

initially resisted Lenin's proposal but ultimately accepted it, and with Lenin's agreement he changed the name to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), although all republics began as ''socialist soviet'' and did not change to the other order until 1936

Events January–February

* January 20 – The Prince of Wales succeeds to the throne of the United Kingdom as King Edward VIII, following the death of his father, George V, at Sandringham House.

* January 28 – Death and state funer ...

. In addition, in the regional languages of several republics, the word ''council'' or ''conciliar'' in the respective language was only quite late changed to an adaptation of the Russian ''soviet'' and never in others, e.g. Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

.

(in the Latin alphabet: ''SSSR'') is the abbreviation of the Russian-language cognate of USSR, as written in Cyrillic letters

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian and Iranic-speaking countries in Southeastern Europe, Easte ...

. The soviets used this abbreviation so frequently that audiences worldwide became familiar with its meaning. After this, the most common Russian initialization is (transliteration: ) which essentially translates to ''Union of SSRs'' in English. In addition, the Russian short form name (transliteration: , which literally means ''Soviet Union'') is also commonly used, but only in its unabbreviated form. Since the start of the Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front, also known as the Great Patriotic War (term), Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and its successor states, and the German–Soviet War in modern Germany and Ukraine, was a Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II ...

at the latest, abbreviating the Russian name of the Soviet Union as has been taboo, the reason being that as a Russian Cyrillic abbreviation is associated with the infamous of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, as ''SS'' is in English.

In English-language media, the state was referred to as the Soviet Union or the USSR. The Russian SFSR dominated the Soviet Union to such an extent that, for most of the Soviet Union's existence, it was colloquially, but incorrectly, referred to as Russia.

History

The history of the Soviet Union began with the ideals of theBolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. It was led by Vladimir L ...

and ended in dissolution amidst economic collapse and political disintegration. Established in 1922 following the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, the Soviet Union quickly became a one-party state under the Communist Party. Its early years under Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

were marked by the implementation of socialist policies and the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

(NEP), which allowed for market-oriented reforms.

The rise of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

in the late 1920s ushered in an era of intense centralization and totalitarianism. Stalin's rule was characterized by the forced collectivization of agriculture, rapid industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

, and the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

, which eliminated perceived enemies of the state. The Soviet Union played a crucial role in the Allied victory in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, but at a tremendous human cost, with millions of Soviet citizens perishing in the conflict.

The Soviet Union emerged as one of the world's two superpowers, leading the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

in opposition to the Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Capitalist Bloc, the Freedom Bloc, the Free Bloc, and the American Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War (1947–1991). While ...

during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. This period saw the USSR engage in an arms race, the Space Race

The Space Race (, ) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between t ...

, and proxy wars

In political science, a proxy war is an armed conflict where at least one of the belligerents is directed or supported by an external third-party power. In the term ''proxy war'', a belligerent with external support is the ''proxy''; both bel ...

around the globe. The post-Stalin leadership, particularly under Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

, initiated a de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

process, leading to a period of liberalization and relative openness known as the Khrushchev Thaw

The Khrushchev Thaw (, or simply ''ottepel'')William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, London: Free Press, 2004 is the period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s when Political repression in the Soviet Union, repression and Censorship in ...

. However, the subsequent era under Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

, referred to as the Era of Stagnation

The "Era of Stagnation" (, or ) is a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev in order to describe the negative way in which he viewed the economic, political, and social policies of the Soviet Union that began during the rule of Leonid Brezhnev (1964 ...

, was marked by economic decline, political corruption, and a rigid gerontocracy

A gerontocracy is a form of rule in which an entity is ruled by leaders who are substantially older than most of the adult population.

In many political structures, power within the ruling class accumulates with age, making the oldest individu ...

. Despite efforts to maintain the Soviet Union's superpower status, the economy struggled due to its centralized nature, technological backwardness, and inefficiencies. The vast military expenditures and burdens of maintaining the Eastern Bloc, further strained the Soviet economy.

In the 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

's policies of Glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

(openness) and Perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

(restructuring) aimed to revitalize the Soviet system but instead accelerated its unraveling. Nationalist movements gained momentum across the Soviet republics

In the Soviet Union, a Union Republic () or unofficially a Republic of the USSR was a constituent federated political entity with a system of government called a Soviet republic, which was officially defined in the 1977 constitution as " ...

, and the control of the Communist Party weakened. The failed coup attempt in August 1991 against Gorbachev by hardline communists hastened the end of the Soviet Union, which formally dissolved on 26 December 1991, ending nearly seven decades of Soviet rule.

Geography

With an area of , the Soviet Union was the world's largest country, a status that is retained by theRussian Federation

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. Covering a sixth of Earth's land surface, its size was comparable to that of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

. Two other successor states, Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

and Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, rank among the top 10 countries by land area, and the largest country entirely in Europe, respectively. The Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an portion accounted for a quarter of the country's area and was the cultural and economic center. The eastern part in Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

extended to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

to the east and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

to the south, and, except some areas in Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

, was much less populous. It spanned over east to west across 11 time zone

A time zone is an area which observes a uniform standard time for legal, Commerce, commercial and social purposes. Time zones tend to follow the boundaries between Country, countries and their Administrative division, subdivisions instead of ...

s, and over north to south. It had five climate zones: tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

, taiga

Taiga or tayga ( ; , ), also known as boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces, and larches. The taiga, or boreal forest, is the world's largest land biome. In North A ...

, steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without closed forests except near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the tropical and subtropica ...

s, desert

A desert is a landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions create unique biomes and ecosystems. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About one-third of the la ...

and mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher t ...

s.

The USSR, like Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, had the world's longest border

Borders are generally defined as geography, geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by polity, political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other administrative divisio ...

, measuring over , or circumferences of Earth. Two-thirds of it was a coast

A coast (coastline, shoreline, seashore) is the land next to the sea or the line that forms the boundary between the land and the ocean or a lake. Coasts are influenced by the topography of the surrounding landscape and by aquatic erosion, su ...

line. The country bordered Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

, the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

, North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, and Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

from 1945 to 1991. The Bering Strait