The history of the Southern United States spans back thousands of years to the first evidence of human occupation. The

Paleo-Indians

Paleo-Indians were the first peoples who entered and subsequently inhabited the Americas towards the end of the Late Pleistocene period. The prefix ''paleo-'' comes from . The term ''Paleo-Indians'' applies specifically to the lithic period in ...

were the

first peoples

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

to inhabit the Americas and what would become the

Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

. By the time Europeans arrived in the 15th century, the region was inhabited by the

Mississippian people. European history in the region would begin with the earliest days of the exploration. Spain, France, and especially England explored and claimed parts of the region.

Starting in the 17th century, the history of the Southern United States developed unique characteristics that came from its economy based primarily on

plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

agriculture and the ubiquitous and prevalent

institution of slavery. Millions of enslaved Africans were imported to the United States primarily but not exclusively for forced labor in the south. While the great majority of Whites did not own slaves, slavery was nevertheless the foundation of the region's economy and social order. Questions of Southern slavery directly impacted the

struggle for American independence throughout the South and gave the region additional power in Congress.

As industrial technologies including the

cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); ...

made slavery even more profitable, Southern states refused to ban slavery- perpetuating the division of the United States between

free and slave states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave s ...

.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

's election in 1860 caused South Carolina to secede which was soon followed by all other states in the region with the exception of the 'border states'. The breakaway states formed the

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

. Lincoln's

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

brought freedom to Black slaves living in rebellious areas as soon as the US Army arrived. With a smaller economy, smaller population and (in some cases) widespread dissent among its white population the Confederate States of America was unable to carry on a protracted struggle with the national government. The

13th

In music or music theory, a thirteenth is the Musical note, note thirteen scale degrees from the root (chord), root of a chord (music), chord and also the interval (music), interval between the root and the thirteenth. The thirteenth is m ...

and

14th amendments gave freedom, citizenship and civil rights to Black Americans all across the United States. The

15th Amendment and

Radical reconstruction

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

laws gave Black men the vote, and for a few years they shared power in the South, despite violent attacks by the Ku Klux Klan. Reconstruction attempted to uplift the former enslaved but this crusade was abandoned in the

Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement, the Tilden-Hayes Compromise, the Bargain of 1877, or Corrupt bargain, the Corrupt Bargain, was a speculated unwritten political deal in the United States to settle the intense dispute ...

and Conservative white Southerners calling themselves

Redeemers

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction era of the United States, Reconstruction Era that followed the American Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party (Unite ...

took control. Even though the Ku Klux Klan was suppressed new White Supremacist organizations

continued to terrorize Black Americans.

After the dissolving of a

Populist movement in the 1890s that attempted to unite working-class blacks and whites

Segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of human ...

laws were implemented all across the region by 1900. Compared to the North, the Southern United States lost its previous political and economic power and fell behind the rest of the United States for decades. Its agricultural economy was often based on

Sharecropping

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement in which a landowner allows a tenant (sharecropper) to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land. Sharecropping is not to be conflated with tenant farming, providing the tenant a ...

practices.

The New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression, which had started in 1929. Roosevel ...

and

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

brought about a generation of Liberal Southerners within the

Democratic Party that looked to accelerate development.

Black Americans and their allies resisted Jim Crow and Segregation, initially with the

Great Migration and later the

civil rights movement. From a political and legal standpoint, many of these aims were realized by the Supreme Court's ruling on

Brown v. Board and the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. Civil Rights coupled with the collapse of Black Belt agriculture has led some historians to postulate that a 'New South' based on Free Trade, Globalization, and cultural diversity has emerged. Meanwhile, the South has influenced the rest of the United States in a process called

Southernization

In the culture of the United States, the idea of Southernization came from the observation that Southern values and beliefs had become more central to political success, reaching an apogee in the 1990s, with a Democratic President and Vice Pre ...

. The legacy of Slavery and Jim Crow continue to impact the region, which by the 21st century was the most populous area of the United States.

Native American civilizations until 1730

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an

ethnographic

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

classification for Native Americans who have traditionally inhabited the area now part of the Southeastern United States and the northeastern border of Mexico, that share common

cultural

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

traits. The concept of a southeastern cultural region was developed by anthropologists, beginning with

Otis Mason and

Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the mov ...

in 1887. The boundaries of the region are defined more by shared cultural traits than by geographic distinctions.

Paleo-Indians

Around 20,000 years ago during the

Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Last Glacial Coldest Period, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period where ice sheets were at their greatest extent between 26,000 and 20,000 years ago.

Ice sheets covered m ...

and its aftermath the first humans likely arrived in the Southern United States.

Overall the region was not only colder but much drier. On average the coastline extended at least 50 miles out into the ocean, most of which would have had a patchy maritime Boreal forest adapted to colder conditions. Meanwhile much of the interior South had a taiga forest comparable to the Canadian Yukon and the Northwest Territories. The Floridian peninsula was much larger and was mostly a temperate savanna. Further west almost the whole of Texas consisted of a tropical desert.

There is debate among archeologists and historians over the exact when the

peopling of the Americas

It is believed that the peopling of the Americas began when Paleolithic hunter-gatherers (Paleo-Indians) entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and we ...

and by extension the American Southeast took place. Cactus Hill near Richmond, Virginia may be one of the oldest archaeological sites in the Americas. If proven to have been inhabited 16,000 to 20,000 years ago, it would provide supporting evidence for pre-Clovis occupation of the Americas.

The first well-dated evidence of human occupation in the south United States occurs around 9500 BC with the appearance of the earliest documented Americans, who are now referred to as

Paleo-Indians

Paleo-Indians were the first peoples who entered and subsequently inhabited the Americas towards the end of the Late Pleistocene period. The prefix ''paleo-'' comes from . The term ''Paleo-Indians'' applies specifically to the lithic period in ...

. Paleoindians were hunter-gatherers that roamed in bands and frequently hunted

megafauna

In zoology, megafauna (from Ancient Greek, Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and Neo-Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") are large animals. The precise definition of the term varies widely, though a common threshold is approximately , this lower en ...

including Wooly Mammoth and Giant short-faced bears.

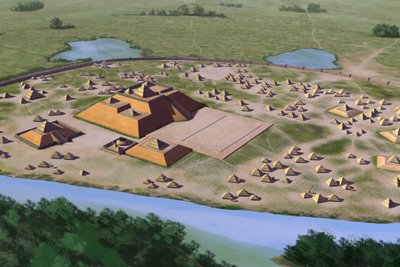

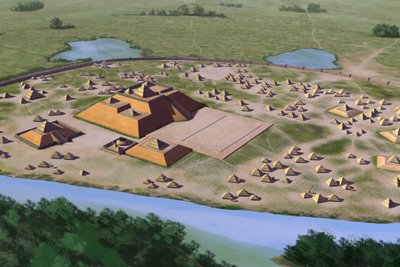

Mound builders

Several cultural stages, such as Archaic (–1000 BC),

Poverty Point

Poverty Point State Historic Site/Poverty Point National Monument (; 16 WC 5) is a prehistoric earthwork constructed by the Poverty Point culture, located in present-day northeastern Louisiana. Evidence of the Poverty Point culture extends ...

, and the Woodland ( – AD 1000), preceded what the Europeans found at the end of the 15th century the

Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a collection of Native American societies that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building la ...

.

Many

pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European col ...

cultures in North America were collectively termed "Mound Builders", but the term has no formal meaning. It does not refer to specific people or archaeological culture but refers to the characteristic

mound

A mound is a wikt:heaped, heaped pile of soil, earth, gravel, sand, rock (geology), rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded ...

earthworks that indigenous peoples erected for an extended period of more than 5,000 years.

Mound builders were originally thought to be exclusively agricultural however early mounds found in Louisiana preceded such cultures and were products of hunter-gatherers. The first mound building was an early marker of political and social complexity among the cultures in the Eastern United States.

Watson Brake

Watson Brake is an archaeological site in present-day Ouachita Parish, Louisiana, from the Archaic period. Dated to about 5400 years ago (approx. 3500 BCE), Watson Brake is considered the oldest earthwork mound complex in North America. It is o ...

in Louisiana, constructed about 3500 BCE during the

Middle Archaic period, is the oldest known and dated mound complex in North America. It is one of 11 mound complexes from this period found in the Lower Mississippi Valley.

The namesake cultural trait of the Mound Builders was the building of mounds and other earthworks, typically

flat-topped pyramids or

platform mound

A platform mound is any earthwork or mound intended to support a structure or activity. It typically refers to a flat-topped mound, whose sides may be pyramidal.

In Eastern North America

The indigenous peoples of North America built substru ...

s. They were generally built as part of complex villages. These cultures generally had developed hierarchical societies that had an elite. These commanded hundreds or even thousands of workers to dig up tons of earth with the hand tools available, move the soil long distances, and finally, workers to create the shape with layers of soil as directed by the builders.

By the 15th century, much of the area had been home to several regional variants of the

Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a collection of Native American societies that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building la ...

for centuries, an agrarian culture that flourished in the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States. The Mississippian way of life began to develop around the 10th century in the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

Valley (for which it is named). The Mississippian culture was a complex,

Native American

Native Americans or Native American usually refers to Native Americans in the United States.

Related terms and peoples include:

Ethnic groups

* Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the pre-Columbian peoples of North, South, and Central America ...

culture that flourished in what is now the Southeastern United States from approximately 800 AD to 1500 AD.

Among these cities

Cahokia

Cahokia Mounds ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from present-day St. Louis. The state archaeology park lies in south-western Illinois between East St. L ...

by

St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

, was significant and the trading network was extensive;

Etowah was a large walled city built close to the location of modern-day

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

. Natives had elaborate and lengthy trading routes connecting their main residential and ceremonial centers extending through the river valleys and from the East Coast to the Great Lakes, however the vast majority of mounds were concentrated in what would later become known as the

Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

. Prior to European contact, some Mississippian cultures were experiencing severe social stress as warfare increased and mound construction slowed or in other cases stopped completely, the societal decline was possibly caused by the Little Ice Age.

Post contact

The Mississippian shatter zone describes the period from 1540 to 1730 in the southeastern part of the present United States. During that time, the interaction between European explorers and colonists transformed the

Native American

Native Americans or Native American usually refers to Native Americans in the United States.

Related terms and peoples include:

Ethnic groups

* Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the pre-Columbian peoples of North, South, and Central America ...

cultures of that region. In 1540 dozens of

chiefdom

A chiefdom is a political organization of people representation (politics), represented or government, governed by a tribal chief, chief. Chiefdoms have been discussed, depending on their scope, as a stateless society, stateless, state (polity) ...

s and several

paramount chiefdoms were scattered throughout the southeast. Chiefdoms featured a noble class ruling a large number of commoners and were characterized by villages and towns with large earthen mounds and complex religious practices. Some noted explorers who encountered and described the culture, by then in decline, included

Pánfilo de Narváez

Pánfilo de Narváez (; born 1470 or 1478, died 1528) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' and soldier in the Americas. Born in Spain, he first sailed to the island of Jamaica (then Santiago) in 1510 as a soldier. Pánfilo participated in the conque ...

(1528),

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1497 – 21 May 1542) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, ...

(1540), and

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

(1699).

The chiefdoms all disappeared by 1730. The most important factor in their gradual disappearance was the chaos induced by slave raids and the enslavement of tens of thousands of Indians. Other factors included epidemics of diseases of European origin and wars among themselves and with European colonists. Indian slaves usually ended up working on plantations in the U.S. or were exported to islands in the

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

. The city of

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

was the most important slave market. The Indian population in the southeast decreased from an estimated 500,000 in 1540 to 90,000 in 1730. The chiefdoms were replaced by simpler coalescent tribes and confederacies made up of survivors and refugees from the fragmenting nations.

Native American descendants of the mound-builders include

Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

,

Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,Bobby ...

,

Caddo

The Caddo people comprise the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Binger, Oklahoma. They speak the Caddo language.

The Caddo Confederacy was a network of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, who ...

,

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; , or ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern ...

,

Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, United States. Their traditional territory was in northern Mississippi, northwestern and northern Alabama, western Tennessee and southwestern Kentucky. Their language is ...

,

Choctaw

The Choctaw ( ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States, originally based in what is now Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. The Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choct ...

,

Creek

A creek in North America and elsewhere, such as Australia, is a stream that is usually smaller than a river. In the British Isles it is a small tidal inlet.

Creek may also refer to:

* Creek people, a former name of Muscogee, Native Americans

* C ...

,

Guale

Guale was a historic Native American chiefdom of Mississippian culture peoples located along the coast of present-day Georgia and the Sea Islands. Spanish Florida established its Roman Catholic missionary system in the chiefdom in the late 16th ...

,

Hitchiti

Hitchiti ( ) was a tribal town in what is now the Southeast United States. It was one of several towns whose people spoke the Hitchiti language. It was first known as part of the Apalachicola Province, an association of tribal towns along the ...

,

Houma, and

Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

peoples, all of whom still reside in the South. Other peoples whose ancestral links to the Mississippian culture are less clear but were clearly in the region before the European incursion include the

Catawba

Catawba may refer to:

*Catawba people, a Native American tribe in the Carolinas

*Catawba language, a language in the Catawban languages family

*Catawban languages

Botany

*Catalpa, a genus of trees, based on the name used by the Catawba and other ...

and the

Powhatan

Powhatan people () are Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who belong to member tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, or Tsenacommacah. They are Algonquian peoples whose historic territories were in eastern Virginia.

Their Powh ...

.

Spanish and French colonization (1519–1821)

Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de León ( – July 1521) was a Spanish explorer and ''conquistador'' known for leading the first official European expedition to Puerto Rico in 1508 and Florida in 1513. He was born in Santervás de Campos, Valladolid, Spain, in ...

was the first European to come to the South when he landed in Florida in 1513.

Alonso Álvarez de Pineda

Alonso Álvarez de Pineda (; 1494–1520) was a Spanish conquistador and cartography, cartographer who was the first to prove the insularity of the Gulf of Mexico by sailing around its coast. In doing so he created the first map to depict what i ...

was the first European to see the Mississippi river, in 1519 when he sailed twenty miles up the river from the Gulf of Mexico.

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1497 – 21 May 1542) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, ...

, a Spanish explorer and ''

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (; ; ) were Spanish Empire, Spanish and Portuguese Empire, Portuguese colonizers who explored, traded with and colonized parts of the Americas, Africa, Oceania and Asia during the Age of Discovery. Sailing ...

'' led the first European expedition deep into the territory in the 1540s, searching for gold, and a passage to China. A vast undertaking, de Soto's North American expedition ranged across parts of the modern states of Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas.

Early settlement attempts largely failed.

Tristán de Luna y Arellano

Tristán de Luna y Arellano (1510 – September 16, 1573) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador of the 16th century.Herbert Ingram Priestley, Tristan de Luna: Conquistador of the Old South: A Study of Spanish Imperial Strategy (1936). http://pa ...

's colony in what is now

Pensacola

Pensacola ( ) is a city in the Florida panhandle in the United States. It is the county seat and only city in Escambia County. The population was 54,312 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Pensacola metropolitan area, which ha ...

failed in 1559. The first French settlement in the Southern United States was

Fort Caroline

Fort Caroline was an attempted French colonial settlement in Florida, located on the banks of the St. Johns River in present-day Duval County. It was established under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière on 22 June 1564, follow ...

, located in what is now

Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville ( ) is the most populous city proper in the U.S. state of Florida, located on the Atlantic coast of North Florida, northeastern Florida. It is the county seat of Duval County, Florida, Duval County, with which the City of Jacksonv ...

, in 1562. It was established as a haven for the

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

s but was destroyed by the Spanish in 1565, demonstrating the competitive nature of European colonization efforts.

More successful was

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (; ; 15 February 1519 – 17 September 1574) was a Spanish admiral, explorer and conquistador from Avilés, in Asturias, Spain. He is notable for planning the first regular trans-oceanic convoys, which became known as ...

's

St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

, founded in 1565. St. Augustine remains the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the continental United States. Spain used Florida as a strategic base to protect its treasure fleets and to counter other European powers' expansion attempts.

By the late 1600s, French explorers arrived from the north. Having built a fur trading network with Indians in the

Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

area, they began to explore the Mississippi River. The French called their territory

Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, in honor of their

King Louis King Louis may refer to:

Kings

* Louis I (disambiguation), multiple kings with the name

* Louis II (disambiguation), multiple kings with the name

* Louis III (disambiguation), multiple kings with the name

* Louis IV (disambiguation), multiple king ...

. The most important French settlements were established at

New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

and

Mobile. Only a few settlers came from France directly, with others arriving from

Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

and

Acadia

Acadia (; ) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. The population of Acadia included the various ...

.

Competition between European powers intensified in the early 18th century. Spanish Texas was one of the

interior provinces of the colonial

Viceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

from 1519 until 1821, but the first Spanish settlers did not arrive until 1716. They operated several

mission

Mission (from Latin 'the act of sending out'), Missions or The Mission may refer to:

Geography Australia

*Mission River (Queensland)

Canada

*Mission, British Columbia, a district municipality

* Mission, Calgary, Alberta, a neighbourhood

* ...

s and a

presidio

A presidio (''jail, fortification'') was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire mainly between the 16th and 18th centuries in areas under their control or influence. The term is derived from the Latin word ''praesidium'' meaning ''pr ...

to maintain a buffer between Spanish territory and the

Louisiana district of New France.

San Antonio

San Antonio ( ; Spanish for " Saint Anthony") is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in Greater San Antonio. San Antonio is the third-largest metropolitan area in Texas and the 24th-largest metropolitan area in the ...

was founded in 1719 and became the capital and largest settlement of Spanish ''Tejas''.

France claimed Texas and set up several short-lived forts there, such as the one in

Red River County, built in 1718, directly challenging Spanish territorial claims. Both Spanish and French colonists faced constant threats from Native American groups. The

Lipan Apache

Lipan Apache are a band of Apache, a Southern Athabaskan languages, Southern Athabaskan Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous people, who have lived in the Oasisamerica, Southwest and Southern Plains for centuries. At the time of European ...

menaced the newly founded Spanish colony until 1749 when the Spanish and Lipan concluded a peace treaty. Both the Spanish and Lipan were then threatened by

Comanche

The Comanche (), or Nʉmʉnʉʉ (, 'the people'), are a Tribe (Native American), Native American tribe from the Great Plains, Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the List of federally recognized tri ...

raids until 1785 when the Spanish and Comanche negotiated a peace agreement.

The competition for control of the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast continued throughout this period, with each European power seeking to establish trade networks and military alliances with Native American tribes.

Most of the Spanish left Florida when it was turned over to Britain in 1763 following the Seven Years' War. However, Spain regained Florida in 1783 and continued to control it until transferring it to the United States in 1821. Spain also colonized parts of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas throughout this period.

By 1821, most European colonial claims in the South had been transferred to the United States or Mexico, setting the stage for American territorial expansion and the development of distinctly Southern institutions.

British colonial era (1585–1775)

Early attempts and first permanent settlements (1585–1650)

In 1585, an expedition organized by

Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebell ...

established the first English settlement in the New World, on

Roanoke Island

Roanoke Island () is an island in Dare County, bordered by the Outer Banks of North Carolina. It was named after the historical Roanoke, a Carolina Algonquian people who inhabited the area in the 16th century at the time of English colonizat ...

in

North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

. The colony failed to prosper, however, and the colonists were retrieved the following year by English ships. In 1587, Raleigh again sent out a group of colonists to Roanoke. From this colony, the first recorded European birth in North America, a child named

Virginia Dare

Virginia Dare (born August 18, 1587; date of death unknown) was the first English people, English child born in an Americas, American English overseas possessions, English colony.

What became of Virginia and the other colonists remains a mystery ...

, was reported. That group of colonists disappeared and is known as the "Lost Colony". Many people theorize that they were either killed or taken in by local tribes.

Like

New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

, the South was originally settled by English

Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

. The English established their first permanent colony in America in

Jamestown, Virginia

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent British colonization of the Americas, English settlement in the Americas. It was located on the northeast bank of the James River, about southwest of present-day Willia ...

, in 1607. Settlement of

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

was driven by a desire to obtain precious metals, specifically gold. The colony was technically still within Spanish territorial claims, yet far enough from most Spanish settlements to avoid colonial clashes. Early in the history of the colony, it became clear that the claims of gold deposits were vastly exaggerated. Referred to as the "Starving Time" of the Jamestown colony, the years from the time of landing in 1607 until 1609 were rife with famine and instability. However, Native American support, in addition to reinforcements from Britain, sustained the small colony. Due to continued political and economic instability, however, the charter of the

Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia was a British Empire, British colonial settlement in North America from 1606 to 1776.

The first effort to create an English settlement in the area was chartered in 1584 and established in 1585; the resulting Roanoke Colo ...

was revoked in 1624. The primary cause of this revocation was the revelation that hundreds of settlers were dead or missing following an attack in 1622 by Native American tribes led by

Opechancanough

Opechancanough ( ; – ) was a sachem (or paramount chief) of the Powhatan Confederacy in present-day Virginia from 1618 until his death. He had been a leader in the confederacy formed by his older brother Powhatan, from whom he inherited t ...

. A royal charter was established for Virginia, yet the

House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses () was the lower house of the Virginia General Assembly from 1619 to 1776. It existed during the colonial history of the United States in the Colony of Virginia in what was then British America. From 1642 to 1776, the Hou ...

, formed in 1619, was allowed to continue as political leadership for the colony in conjunction with a royal governor.

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore (; 1580 – 15 April 1632) was an English politician. He achieved domestic political success as a member of parliament and later Secretary of State under King James I. He lost much of his political power a ...

, applied to

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

for a

royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

for what was to become the

Province of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an Kingdom of England, English and later British colonization of the Americas, British colony in North America from 1634 until 1776, when the province was one of the Thirteen Colonies that joined in supporting the A ...

. After Calvert died in April 1632, the charter for "Maryland Colony" (in

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''Terra Mariae'') was granted to his son,

Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore

Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore (8 August 1605 – 30 November 1675) was an English politician and lawyer who was the first proprietor of Maryland. Born in Kent, England in 1605, he inherited the proprietorship of overseas colonies in Avalo ...

, on June 20, 1632. Maryland soon became one of the few predominantly Catholic regions among the English colonies in North America. Maryland was also one of the key destinations where the government sent tens of thousands of English convicts punished by sentences of transportation.

Colonial society and economy in the 17th century (1650–1700)

A key figure in the region's political and cultural development was

William Berkeley, who served, with some interruptions, as governor of Virginia from 1645 until 1675. His desire for an elite immigration to Virginia led to the "Second Sons" policy, in which younger sons of

English aristocrats were recruited to emigrate to Virginia. Berkeley also emphasized the

headright

: '' Osage headrights is a specific and distinct topic. This article is about the general topic of headrights.''

A headright refers to a legal grant of land given to settlers during the period of European colonization in the Americas. A "headright" ...

system, the offering of large tracts of land to those arriving in the colony. This early immigration by an elite contributed to the development of an aristocratic political and social structure in the South.

English colonists, especially young

indentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of Work (human activity), labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as paymen ...

s, continued to arrive along the southern Atlantic coast. Virginia became a prosperous English colony. During this period,

life expectancy

Human life expectancy is a statistical measure of the estimate of the average remaining years of life at a given age. The most commonly used measure is ''life expectancy at birth'' (LEB, or in demographic notation ''e''0, where '' ...

was often low, and indentured servants came from overpopulated European areas. With the lower price of servants compared to slaves, and the high mortality of the servants, planters often found it much more economical to use servants initially.

From the introduction of tobacco in 1613, its cultivation began to form the basis of the early Southern economy. In 1640, the Virginia General Court recorded the earliest documentation of lifetime slavery when it sentenced

John Punch to lifetime servitude under

Hugh Gwyn for running away.

Bacon's Rebellion

Bacon's Rebellion was an armed rebellion by Virginia settlers that took place from 1676 to 1677. It was led by Nathaniel Bacon against Colonial Governor William Berkeley, after Berkeley refused Bacon's request to drive Native American India ...

was an unsuccessful armed rebellion by some Virginia settlers that took place from 1676 to 1677, led by

Nathaniel Bacon. Thousands of Virginians from all races and classes (including those in indentured servitude) rose up in arms against Berkeley, chasing him from

Jamestown and ultimately torching the settlement.

Edmund S. Morgan

Edmund Sears Morgan (January 17, 1916 – July 8, 2013) was an American historian and an authority on early American history. He was the Sterling Professor of History at Yale University, where he taught from 1955 to 1986. He specialized in Americ ...

's 1975 classic connected the threat of Bacon's Rebellion with the colony's transition over to slavery. This marked a crucial turning point as the South began its transition from indentured servitude to race-based slavery.

Expansion of slavery and plantation agriculture (1670–1740)

The

Province of North Carolina

The Province of North Carolina, originally known as the Albemarle Settlements, was a proprietary colony and later royal colony of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776.(p. 80) It was one of the five Southern col ...

developed differently from

South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

almost from the beginning. In the 1650s and 1660s, settlers (mostly English) moved south from

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, in addition to runaway servants and fur trappers. They settled chiefly in the

Albemarle borderlands region. In 1665, the Crown issued a second charter to resolve territorial questions, and the division of the province into North and South became official in 1712.

By the late 17th century and early 18th century, slaves became economically viable sources of labor for the growing tobacco culture in the Chesapeake and rice cultivation in South Carolina. Much of the slave trade was conducted as part of the "

triangular trade

Triangular trade or triangle trade is trade between three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. It has been used to offset ...

", a three-way exchange of slaves, rum, and sugar. The plantations of

South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

often were modeled on Caribbean plantations, with enslaved Africans bringing crucial knowledge of rice cultivation that made the colony prosperous. The

Barbados Slave Code

The Barbados Slave Code of 1661, officially titled as An Act for the better ordering and governing of Negroes, was a law passed by the Parliament of Barbados to provide a legal basis for slavery in the English colony of Barbados and, ostensibly, ...

served as the basis for the slave codes adopted in

Carolina (1696),

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, and other colonies.

Slavery in the Colonial period was not without resistance. The most notable rebellion in the Southern Colonies was the

Stono Rebellion

The Stono Rebellion (also known as Cato's Conspiracy or Cato's Rebellion) was a slave revolt that began on 9 September 1739, in the colony of South Carolina. It was the largest slave rebellion in the Southern Colonial era, with 25 colonists an ...

of 1739. Portuguese-speaking Angolans in South Carolina, with prior military training, attempted to escape to Catholic Spanish Florida. The rebellion was intercepted by the South Carolina militia and almost all participants were executed. The rebellion profoundly changed slavery in South Carolina—the

Negro Act of 1740 The Negro Act of 1740 was passed in the Province of South Carolina, on May 10, 1740, during colonial Governor William Bull's time in office, in response to the Stono Rebellion in 1739.

The comprehensive act made it illegal for enslaved African ...

placed harsh regulations on slaves, including a provision that allowed any White colonist to inspect any slave for any reason.

Mature colonial South (1740–1775)

By the mid-18th century, the economies of the Southern colonies were firmly tied to agriculture and slave labor. The great

plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

s were formed by wealthy colonists who accumulated vast wealth from their land. Tobacco dominated in the upper colonies (Maryland, Virginia, and portions of North Carolina), while rice and indigo cultivation focused in the lower colonies of South Carolina and Georgia. Cotton did not become a mainstay until much later, after the

cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); ...

of 1794 greatly increased its profitability.

The plantation owners built an aristocratic lifestyle, but they represented only a small portion of Southern society. The majority were small

yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of Serfdom, servants in an Peerage of England, English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in Kingdom of England, mid-1 ...

farmers who worked small tracts of land to feed themselves and trade locally. They developed a political activism in response to the growing

oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

of the plantation owners, with many politicians from this era being yeoman farmers speaking out to protect their rights as free men.

Charleston became a booming trade town for the southern colonies. The abundance of

pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as cu ...

trees in the area provided raw materials for shipyards to develop, and the harbor provided a safe port for English ships. The colonists exported tobacco, indigo and rice and imported tea, sugar, and slaves. After the late 17th century, the economies of the North and the South began to diverge, with the Southern emphasis on export production contrasting with the Northern emphasis on food production.

The last major colonial experiment was

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, envisioned by British General

James Oglethorpe

Lieutenant-General James Edward Oglethorpe (22 December 1696 – 30 June 1785) was a British Army officer, Tory politician and colonial administrator best known for founding the Province of Georgia in British North America. As a social refo ...

as a colony which would serve as a haven for English subjects who had been

imprisoned for debt and "the worthy poor." Originally designed as a buffer against Spanish Florida and initially prohibiting slavery, Georgia's ban on slavery was lifted by 1751 and the colony became a

royal colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by England, and then Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English and later British Empire. There was usually a governor to represent the Crown, appointed by the British monarch on ...

by 1752.

By 1775, the Southern colonies had developed a distinctive society based on plantation agriculture, slave labor, and hierarchical social structures. This economic and social system would play a crucial role in the tensions leading to the American Revolution.

American Revolution (1775–1789)

Some southern colonies, led by Virginia, gave support for the

Patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot(s) or The Patriot(s) may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American R ...

cause. Georgia, the newest, smallest, most exposed and militarily most vulnerable colony, hesitated briefly before joining the other 12 colonies in Congress. South Carolina meanwhile had the largest loyalist support of any state. As soon as news arrived of the

Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775 were the first major military actions of the American Revolutionary War between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Patriot (American Revolution), Patriot militias from America's Thirteen Co ...

in April 1775, Patriot forces took control of every colony. After the combat began,

Governor Dunmore

John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore (1730 – 25 February 1809) was a British colonial administrator who served as the governor of Virginia from 1771 to 1775. Dunmore was named governor of New York in 1770. He succeeded to the same position in th ...

of Virginia was forced to flee to a British warship off the coast. In late 1775 he issued a

proclamation offering freedom to slaves who fought for the British Army. Over 1,000 volunteered and served in British uniforms, chiefly in the

Ethiopian Regiment

The Royal Ethiopian Regiment, also known as Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment, was a British military unit formed of "indentured servants, negros or others" organized after the April 1775 outbreak of the American Revolution by the Earl of Dunmor ...

. However, they were defeated in the

Battle of Great Bridge

The Battle of Great Bridge was fought December 9, 1775, in the area of Great Bridge, Virginia, early in the American Revolutionary War. The refusal by colonial Virginia militia forces led to the departure of Royal Governor Lord Dunmore and any ...

, and most of them died of disease. The

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

took Dunmore and other officials home in August 1776, and also carried to freedom 300 surviving former slaves.

Thomas Jefferson wrote the first draft of the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

, condemning the United Kingdom for bringing slaves to North America despite being a slaveowner himself. Other delegates insisted on removal of any mention of slavery from the document. South Carolina's delegation ensured the continuance of the institution of slavery. Delegate Thomas Lynch threatened to break away from the country if congress entertained any discussion on slavery, indicating that for South Carolina preserving slavery was more important than American nationhood. Meanwhile

Edward Rutledge

Edward Rutledge (November 23, 1749 – January 23, 1800) was an American Founding Father and politician who signed the Continental Association and was the youngest signatory of the Declaration of Independence. He later served as the 39th govern ...

tried unsuccessfully to expel black soldiers from the

Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

After their defeat at

Saratoga in 1777 and the entry of the French into the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, the British turned their attention to the South. With fewer regular troops at their disposal, the British commanders developed a "southern strategy" that relied heavily on volunteer soldiers and militia from the

Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

element. Beginning in late December 1778, the British captured

Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) biome and ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach th ...

and controlled the

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

coastline. In 1780 they

seized Charleston, capturing a large American army. A significant victory at the

Battle of Camden

The Battle of Camden (August 16, 1780), also known as the Battle of Camden Court House, was a major victory for the Kingdom of Great Britain, British in the Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War. On August 16, 1780, British forces ...

meant that royal forces soon controlled most of Georgia and South Carolina. The British set up a network of forts inland, expecting the Loyalists would rally to the flag. Far too few Loyalists turned out however, and the British had to fight their way north into North Carolina and Virginia with a severely weakened army. Behind them most of the territory they had already captured dissolved into a chaotic

guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrorism ...

, fought predominantly between bands of Loyalist and Patriot militia, with the Patriots retaking the areas the British had previously gained. In January 1781, the

Battle of Cowpens

The Battle of Cowpens was a military engagement during the American Revolutionary War fought on January 17, 1781, near the town of Cowpens, South Carolina. American Patriot (American Revolution), Patriot forces, estimated at 2,000 militia and reg ...

near

Cowpens, South Carolina

Cowpens is a town in Spartanburg County, South Carolina, Spartanburg County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 2,162 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census. The town was chartered February 20, 1880, and was incorporated in 1 ...

, was a turning point in the American reconquest of South Carolina from the British.

The British army marched to

Yorktown, Virginia

Yorktown is a town in York County, Virginia, United States. It is the county seat of York County, one of the eight original shires formed in Colony of Virginia, colonial Virginia in 1682. Yorktown's population was 195 as of the 2010 census, while ...

, where they expected to be rescued by a British fleet. The fleet showed up but so did a larger French fleet, so the British fleet after the

Battle of the Chesapeake

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes or simply the Battle of the Capes, was a crucial naval battle in the American Revolutionary War that took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 5 September 1 ...

returned to New York for reinforcements, leaving

General Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805) was a British Army officer, Whig politician and colonial administrator. In the United States and United Kingdom, he is best known as one of the leading Britis ...

trapped by the much larger American and French armies under Washington. He surrendered. The most prominent Loyalists, especially those who joined Loyalist regiments, were evacuated by the Royal Navy.

After the upheaval of the American Revolution effectively came to an end at the

Siege of Yorktown

The siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown and the surrender at Yorktown, was the final battle of the American Revolutionary War. It was won decisively by the Continental Army, led by George Washington, with support from the Ma ...

(1781), the South became a major political force in the development of the United States. With the ratification of the

Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation, officially the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, was an agreement and early body of law in the Thirteen Colonies, which served as the nation's first Constitution, frame of government during the Ameri ...

, the South found political stability and a minimum of federal interference in state affairs. However, with this stability came a weakness in its design, and the inability of the Confederation to maintain economic viability eventually forced the creation of the

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

in Philadelphia in 1787. Importantly, Southerners of 1861 often believed their

secession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

ist efforts and the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

paralleled the American Revolution, as a military and ideological "replay" of the latter.

Southern leaders were able to protect their sectional interests during the

Constitutional Convention of 1787

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. While the convention was initially intended to revise the league of states and devise the first system of federal government under the Articles of Conf ...

, preventing the insertion of any explicit

anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

position in the Constitution. Moreover, they were able to force the inclusion of the "fugitive slave clause" and the "

Three-Fifths Compromise

The Three-fifths Compromise, also known as the Constitutional Compromise of 1787, was an agreement reached during the 1787 United States Constitutional Convention over the inclusion of slaves in counting a state's total population. This count ...

". Nevertheless,

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

retained the power to regulate the

slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

. Twenty years after the ratification of the Constitution, the law-making body prohibited the importation of slaves, effective January 1, 1808. While North and South were able to find common ground to gain the benefits of a strong Union, the unity achieved in the Constitution masked deeply rooted differences in economic and political interests.

In the South, agrarian laissez-faire formed the basis of political culture. Led by

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

and

James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

, this agrarian position is characterized by the

epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

on the grave of Jefferson. While including his "condition bettering" roles in the foundation of the

University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his The Lawn, Academical Village, a World H ...

, and the writing of the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

and the

Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom was drafted in 1777 by Thomas Jefferson in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and introduced into the Virginia General Assembly in Richmond in 1779. On January 16, 1786, the Assembly enacted the statute into the ...

, absent from the epitaph was his role as President of the United States. The development of Southern political thought thus focused on the ideal of the

yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of Serfdom, servants in an Peerage of England, English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in Kingdom of England, mid-1 ...

farmer; i.e., those who are tied to the land also have a vested interest in the stability and survival of the government.

The Revolution provided a shock to slavery in the South and other regions of the new country. Thousands of slaves took advantage of wartime disruption to find their own freedom, catalyzed by the British Governor Dunmore of Virginia's promise of freedom for service. Many others were removed by Loyalist owners and became slaves elsewhere in the British Empire. Between 1770 and 1790, there was a sharp decline in the percentage of blacks – from 61% to 44% in South Carolina and from 45% to 36% in Georgia. In addition, some slaveholders were inspired to free their slaves after the Revolution. In the

Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, economics, demographics, ...

, more than 10% of all blacks were free by 1810, a significant expansion from pre-war proportions of less than 1% free.

Antebellum era (1789–1861)

From a cultural and social standpoint, the "Old South" is used to describe the rural, agriculturally-based, slavery-reliant economy and society in the

Antebellum South

The ''Antebellum'' South era (from ) was a period in the history of the Southern United States that extended from the conclusion of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. This era was marked by the prevalent practic ...

, prior to the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

(1861–1865), in contrast to the "

New South

New South, New South Democracy or New South Creed is a slogan in the history of the American South first used after the American Civil War. Reformers used it to call for a modernization of society and attitudes, to integrate more fully with th ...

" of the post-

Reconstruction Era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

.

There were almost 700,000 enslaved persons in the U.S. in 1790, which equated to approximately 18 percent of the total population, or roughly one in every six people. This had persisted through the 17th and 18th centuries, but the invention of the

cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); ...

by

Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin in 1793, one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.

Whitney's ...

in the 1790s made slavery even more profitable and caused a larger plantation system developed. In the 15 years between the invention of the cotton gin and the passage of the

Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves

The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 (, enacted March 2, 1807) is a United States federal law that prohibited the importation of slaves into the United States. It took effect on January 1, 1808, the earliest date permitted by the U ...

, an increase in the slave trade occurred, furthering the slave system in the United States.

As the country expanded its territory and economy west,

New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

was the third largest American city in population by 1840. The success of the city was based on the growth of international trade associated with products being shipped to and from the interior of the country down the Mississippi River. New Orleans also had the largest slave market in the country, as traders brought slaves by ship and overland to sell to planters across the Deep South. The city was a cosmopolitan port with a variety of jobs that attracted more immigrants than other areas of the South. Because of lack of investment, however, construction of railroads to span the region lagged behind the North. People relied most heavily on river traffic for getting their crops to market and for transportation.

Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century

political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

in the United States that expanded

suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

to most

white men

White is a racial classification of people generally used for those of predominantly European ancestry. It is also a skin color specifier, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, ethnicity and point of view.

Desc ...

over the age of 21 and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh

U.S. president

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

,

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, it became the nation's dominant political worldview for a generation. This era, called the Jacksonian Era or

Second Party System

The Second Party System was the Political parties in the United States, political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to early 1854, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising leve ...

by

historians

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human species; as well as the ...

and

political scientists

The following is a list of notable political scientists. Political science is the scientific study of politics, a social science dealing with systems of governance and power.

A

* Robert Abelson – Yale University psychologist and political ...

, lasted roughly from Jackson's 1828 election as president until

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

became the dominant issue with the passage of the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

in 1854 and the political repercussions of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

dramatically reshaped American politics. It emerged when the long-dominant

Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

became factionalized around the

1824 United States presidential election

Presidential elections were held in the United States from October 26 to December 2, 1824. Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and William Crawford were the primary contenders for the presidency. The result of the election was in ...

. Jackson's supporters began to form the modern

Democratic Party.

Broadly speaking, the era was characterized by a

democratic spirit. It built upon Jackson's equal political policy, subsequent to ending what he termed a

monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek and ) is a market in which one person or company is the only supplier of a particular good or service. A monopoly is characterized by a lack of economic Competition (economics), competition to produce ...

of government by

elite