Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an

associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is a Justice (title), justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the J ...

. She was

nominated by President

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

on May 26, 2009, and has served since August 8, 2009. She is the third woman, the first Hispanic, and the first Latina to serve on the Supreme Court.

Sotomayor was born in

the Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, New York City,

to Puerto Rican-born parents. Her father died when she was nine, and she was subsequently raised by her mother. Sotomayor graduated ''

summa cum laude'' from

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

in 1976 and received her

Juris Doctor

A Juris Doctor, Doctor of Jurisprudence, or Doctor of Law (JD) is a graduate-entry professional degree that primarily prepares individuals to practice law. In the United States and the Philippines, it is the only qualifying law degree. Other j ...

from

Yale Law School

Yale Law School (YLS) is the law school of Yale University, a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was established in 1824. The 2020–21 acceptance rate was 4%, the lowest of any law school in the United ...

in 1979, where she was an editor of the ''

Yale Law Journal

''The Yale Law Journal'' (YLJ) is a student-run law review affiliated with the Yale Law School. Published continuously since 1891, it is the most widely known of the eight law reviews published by students at Yale Law School. The journal is one ...

''.

She worked as an

assistant district attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, county prosecutor, state attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or solicitor is the chief prosecutor or chief law enforcement officer represe ...

in New York for four and a half years before entering private practice in 1984. She played an active role on the boards of directors for the

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, the

State of New York Mortgage Agency, and the

New York City Campaign Finance Board.

Sotomayor was nominated to the

U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York by President

George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

in 1991; confirmation followed in 1992. In 1997, she was nominated by President

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

to the

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Her appointment to the court of appeals was slowed by the

Republican majority in the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

because of their concerns that the position might lead to a Supreme Court nomination, but she was confirmed in 1998. On the Second Circuit, Sotomayor heard appeals in more than 3,000 cases and wrote about 380 opinions. Sotomayor has taught at the

New York University School of Law and

Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School (CLS) is the Law school in the United States, law school of Columbia University, a Private university, private Ivy League university in New York City.

The school was founded in 1858 as the Columbia College Law School. The un ...

.

In May 2009, President

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

nominated Sotomayor to the Supreme Court following the retirement of Justice

David Souter. Her nomination was confirmed by the Senate in August 2009 by a vote of 68–31. While on the Court, Sotomayor has supported the informal liberal bloc of justices when they divide along the commonly perceived ideological lines. During her Supreme Court tenure, Sotomayor has been identified with concern for the rights of criminal defendants and criminal justice reform, as demonstrated in majority opinions such as ''

J. D. B. v. North Carolina''. She is also known for her impassioned dissents on issues of race and ethnic identity, including in ''

Schuette v. BAMN'', ''

Utah v. Strieff'', and ''

Trump v. Hawaii

''Trump v. Hawaii'', No. 17-965, 585 U.S. 667 (2018), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case involving Presidential Proclamation 9645 signed by President Donald Trump, which restricted travel into the United States by people from seve ...

''.

Early life

Sotomayor was born in the New York City

borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English language, English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

...

of

the Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

.

Her father was Juan Sotomayor (c. 1921–1964),

from the area of

Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico

Santurce (, meaning Saint George from Basque language, Basque ''Santurtzi'') is the largest and most populated Barrios of San Juan, Puerto Rico, barrio of the Municipalities of Puerto Rico, municipality of San Juan, Puerto Rico, San Juan, the cap ...

,

and her mother was Celina Báez (1927–2021),

an orphan

from

Santa Rosa in

Lajas, a rural area on Puerto Rico's southwest coast.

The two left Puerto Rico separately, met, and married during World War II after Celina served in the

Women's Army Corps.

Juan Sotomayor had a third-grade education, did not speak English, and worked as a

tool and die worker;

Celina Báez worked as a

telephone operator and then a

practical nurse.

Sonia's younger brother, Juan Sotomayor (born c. 1957), later became a physician and university professor in the

Syracuse, New York

Syracuse ( ) is a City (New York), city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, United States. With a population of 148,620 and a Syracuse metropolitan area, metropolitan area of 662,057, it is the fifth-most populated city and 13 ...

, area.

Sotomayor was raised a Catholic

and grew up in Puerto Rican communities in the

South Bronx

The South Bronx is an area of the Boroughs of New York City, New York City borough of the Bronx. The area comprises neighborhoods in the southern part of the Bronx, such as Concourse, Bronx, Concourse, Mott Haven, Bronx, Mott Haven, Melrose, B ...

and

East Bronx; she calls herself a "

Nuyorican".

The family lived in a South Bronx

tenement

A tenement is a type of building shared by multiple dwellings, typically with flats or apartments on each floor and with shared entrance stairway access. They are common on the British Isles, particularly in Scotland. In the medieval Old Town, E ...

before moving in 1957 to the well-maintained, racially and ethnically mixed, working-class Bronxdale Houses

housing project in

Soundview (which has over time been thought as part of both the East Bronx and South Bronx).

In 2010, the

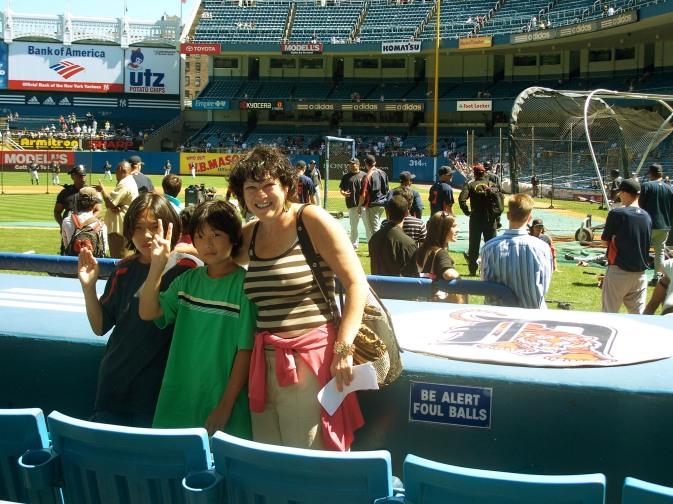

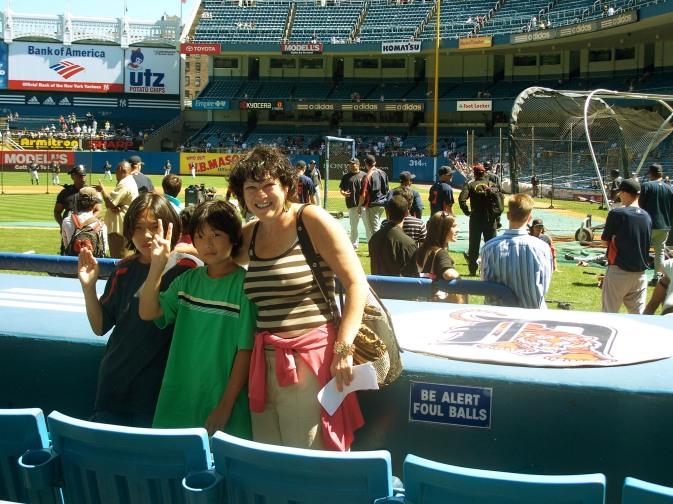

Bronxdale Houses were renamed in her honor. Her relative proximity to

Yankee Stadium

Yankee Stadium is a baseball stadium located in the Bronx in New York City. It is the home field of Major League Baseball’s New York Yankees and New York City FC of Major League Soccer.

The stadium opened in April 2009, replacing the Yankee S ...

led to her becoming a lifelong fan of the

New York Yankees

The New York Yankees are an American professional baseball team based in the Boroughs of New York City, New York City borough of the Bronx. The Yankees compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Am ...

.

The extended family got together frequently

and regularly visited Puerto Rico during summers.

Sotomayor grew up with an

alcoholic father and a mother who was emotionally distant; she felt closest to her grandmother, who she later said was a source of "protection and purpose".

Sotomayor was diagnosed with

type 1 diabetes at age seven

and began taking daily

insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

injections.

Her father died of heart problems at age 42, when she was nine years old.

After that, she became fluent in English.

Celina Sotomayor put great stress on the value of education; she bought the ''

Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

'' for her children, something unusual in the housing projects.

Despite the distance between the two, which became greater after her father's death and which was not fully reconciled until decades later,

Sotomayor has credited her mother with being her "life inspiration".

Education

For grammar school, Sotomayor attended

Blessed Sacrament School in

Soundview, where she was

valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the class rank, highest-performing student of a graduation, graduating class of an academic institution in the United States.

The valedictorian is generally determined by an academic institution's grade poin ...

and had a near-perfect attendance record.

Although underage, Sotomayor worked at a local retail store and a hospital. Sotomayor has said that she was first inspired by the strong-willed children's book detective character

Nancy Drew, but, after her diabetes diagnosis led her doctors to suggest a different career path, she was inspired to pursue a legal career and become a judge by watching the ''

Perry Mason'' television series.

She reflected in 1998: "I was going to college and I was going to become an attorney, and I knew that when I was ten. Ten. That's no jest."

Sotomayor passed the entrance tests for and then attended

Cardinal Spellman High School in the Bronx.

At Cardinal Spellman, Sotomayor was on the

forensics team and was elected to the

student government.

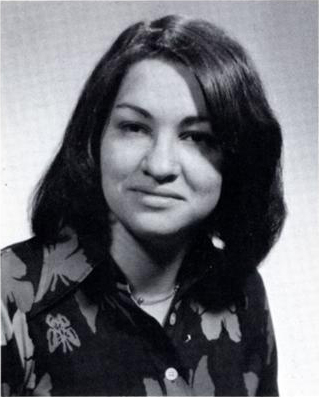

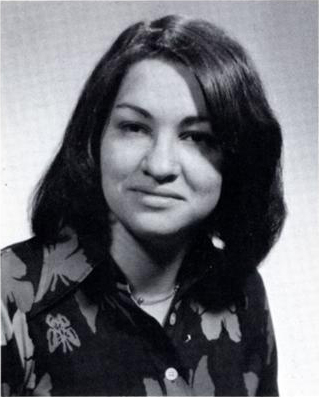

She graduated as valedictorian in 1972.

Meanwhile, the Bronxdale Houses had fallen victim to increasing heroin use, crime, and the emergence of the

Black Spades gang.

In 1970, the family found refuge by moving to

Co-op City in the Northeast Bronx.

College and law school

Sotomayor attended

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

. She has said she was admitted in part due to her achievements in high school and in part because

affirmative action

Affirmative action (also sometimes called reservations, alternative access, positive discrimination or positive action in various countries' laws and policies) refers to a set of policies and practices within a government or organization seeking ...

made up for her standardized test scores, which she described as "not comparable to her colleagues at Princeton and Yale."

She would later say that there are cultural biases built into such testing

and praised affirmative action for fulfilling "its purpose: to create the conditions whereby students from disadvantaged backgrounds could be brought to the starting line of a race many were unaware was even being run."

Sotomayor described her time at Princeton as life-changing.

Initially, she felt like "a visitor landing in an alien country"

coming from the Bronx and Puerto Rico.

Princeton had few female students and fewer Latinos (about 20).

She was too intimidated to ask questions during her freshman year;

her writing and vocabulary skills were weak and she lacked knowledge in the

classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

.

She put in long hours in the library and worked over summers with a professor outside of class, and gained skills, knowledge and confidence.

She became a moderate student activist

and co-chair of the ''Acción Puertorriqueña'' organization, which served as a social and political hub and sought more opportunities for Puerto Rican students.

She worked in the admissions office, traveling to high schools and lobbying on behalf of her best prospects.

As a student activist, Sotomayor focused on faculty hiring and curriculum, since Princeton did not have a single full-time Latino professor nor any class on

Latin American studies

Latin American studies (LAS) is an academic and research field associated with the study of Latin America. The interdisciplinary study is a subfield of area studies, and can be composed of numerous disciplines such as economics, sociology, histor ...

.

A meeting with university president

William G. Bowen in her sophomore year saw no results,

with Sotomayor telling a ''

New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' reporter at the time that "Princeton is following a policy of benign neutrality and is not making substantive efforts to change."

She also wrote

opinion pieces for the ''

Daily Princetonian'' addressing the same issues.

Acción Puertorriqueña filed a formal letter of complaint in April 1974 with the

Department of Health, Education and Welfare, saying the school discriminated in its hiring and admission practices.

The university began to hire Latino faculty,

and Sotomayor established an ongoing dialogue with Bowen.

Sotomayor also successfully persuaded professor

Peter Winn, who specialized in

Latin American history, to create a

seminar

A seminar is a form of academic instruction, either at an academic institution or offered by a commercial or professional organization. It has the function of bringing together small groups for recurring meetings, focusing each time on some part ...

on

Puerto Rican history and politics.

Sotomayor joined the governance board of Princeton's

Third World Center and served on the university's student–faculty Discipline Committee, which issued rulings on student infractions.

She also ran an

after-school program

After-school activities, also known as after-school programs or after-school care, started in the early 1900s mainly just as supervision of students after the final school bell. Today, after-school programs do much more. There is a focus on helping ...

for local children,

and volunteered as an interpreter for Latino patients at

Trenton Psychiatric Hospital.

Academically, Sotomayor stumbled her first year at Princeton,

but later received almost all A grades in her final two years of college.

Sotomayor wrote her

senior thesis on

Luis Muñoz Marín, the first democratically elected

governor of Puerto Rico

The governor of Puerto Rico () is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States. Elected to a 4 year-term through popular vote by the residents of the archipelago and island, ...

, and on the territory's struggles for economic and political self-determination.

The 178-page work, "La Historia Ciclica de Puerto Rico: The Impact of the Life of Luis Muñoz Marin on the Political and Economic History of Puerto Rico, 1930–1975", won honorable mention for the Latin American Studies Thesis Prize.

As a senior, Sotomayor won the Pyne Prize, the top award for undergraduates, which reflected both strong grades and extracurricular activities.

In 1976, she was elected to

Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

and graduated ''

summa cum laude'' with an A.B. in history.

She was influenced by

critical race theory

Critical race theory (CRT) is an academic field focused on the relationships between Social constructionism, social conceptions of Race and ethnicity in the United States census, race and ethnicity, Law in the United States, social and political ...

, which would be reflected in her later speeches and writings.

Sotomayor entered

Yale Law School

Yale Law School (YLS) is the law school of Yale University, a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was established in 1824. The 2020–21 acceptance rate was 4%, the lowest of any law school in the United ...

in the fall of 1976.

While she believes she again benefited from affirmative action to compensate for relatively low standardized test scores,

a former dean of admissions at Yale has said that given her record at Princeton, it probably had little effect.

At Yale she fit in well

although she found there were few Latino students.

She was known as a hard worker but she was not considered among the star students in her class.

Yale General Counsel and professor

José A. Cabranes acted as an early mentor to her to successfully transition and work within "the system".

Sotomayor became an editor of the ''

Yale Law Journal

''The Yale Law Journal'' (YLJ) is a student-run law review affiliated with the Yale Law School. Published continuously since 1891, it is the most widely known of the eight law reviews published by students at Yale Law School. The journal is one ...

'',

and was also

managing editor

A managing editor (ME) is a senior member of a publication's management team. Typically, the managing editor reports directly to the editor-in-chief and oversees all aspects of the publication.

United States

In the United States, a managing edi ...

of the student-run ''

Yale Studies in World Public Order'' publication (later known as the ''

Yale Journal of International Law'').

She published a law review note on the effect of possible

Puerto Rican statehood on the island's mineral and ocean rights.

She was a semi-finalist in the Barristers Union mock trial competition.

She served as the co-chair of a group for Latin, Asian, and Native American students, and continued to advocate for the hiring of more Hispanic faculty.

Following her second year, she gained a job as a summer associate with the prominent New York law firm

Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison.

By her own later evaluation, her performance there was lacking.

[Sotomayor, ''My Beloved World'', pp. 182–183.] She did not receive an offer for a full-time position, an experience that she later described as a "kick in the teeth" and one that would bother her for years.

In her third year, she filed a formal complaint against the established Washington, D.C., law firm of

Shaw, Pittman, Potts & Trowbridge for suggesting during a recruiting dinner that she was at Yale only via affirmative action.

Sotomayor refused to be interviewed by the firm further and filed her complaint with a faculty–student tribunal, which ruled in her favor.

Her action triggered a campus-wide debate,

and news of the firm's subsequent December 1978 apology made ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

''.

In 1979, Sotomayor was awarded a

Juris Doctor

A Juris Doctor, Doctor of Jurisprudence, or Doctor of Law (JD) is a graduate-entry professional degree that primarily prepares individuals to practice law. In the United States and the Philippines, it is the only qualifying law degree. Other j ...

from Yale Law School.

She was admitted to the

New York Bar the following year.

Early legal career

On the recommendation of Cabranes, Sotomayor was hired out of law school as an

assistant district attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, county prosecutor, state attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or solicitor is the chief prosecutor or chief law enforcement officer represe ...

under

New York County District Attorney

Robert Morgenthau starting in 1979.

She said at the time that she did so with conflicted emotions: "There was a tremendous amount of pressure from my community, from the third world community, at Yale. They could not understand why I was taking this job. I'm not sure I've ever resolved that problem."

It was a time of crisis-level crime rates and drug problems in New York, Morgenthau's staff was overburdened with cases, and like other rookie prosecutors, Sotomayor was initially fearful of appearing before judges in court.

Working in the trial division,

she handled heavy caseloads as she prosecuted everything from

shoplifting and prostitution to

robberies, assaults, and murders.

She also worked on cases involving

police brutality

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or Public order policing, a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, b ...

.

She was not afraid to venture into tough neighborhoods or endure squalid conditions in order to interview witnesses.

In the courtroom, she was effective at cross examination and at simplifying a case in ways to which a jury could relate.

In 1983, she helped convict

Richard Maddicks (known as the "Tarzan Murderer" who acrobatically entered apartments, robbed them, and shot residents for no reason).

She felt lower-level crimes were largely products of socioeconomic environment and poverty, but she had a different attitude about serious felonies: "No matter how liberal I am, I'm still outraged by crimes of violence. Regardless of whether I can sympathize with the causes that lead these individuals to do these crimes, the effects are outrageous."

Hispanic-on-Hispanic crime was of particular concern to her: "The saddest crimes for me were the ones that my own people committed against each other."

In general, she showed a passion for bringing law and order to the streets of New York, displaying special zeal in pursuing

child pornography

Child pornography (also abbreviated as CP, also called child porn or kiddie porn, and child sexual abuse material, known by the acronym CSAM (underscoring that children can not be deemed willing participants under law)), is Eroticism, erotic ma ...

cases, unusual for the time.

She worked 15-hour days and gained a reputation for being driven and for her preparedness and fairness.

One of her job evaluations labelled her a "potential superstar".

Morgenthau later described her as "smart, hard-working,

nd havinga lot of common sense,"

and as a "fearless and effective prosecutor."

She stayed a typical length of time in the post

and had a common reaction to the job: "After a while, you forget there are decent, law-abiding people in life."

Sotomayor and her husband, Kevin Edward Noonan, whom she had married in 1976, divorced amicably in 1983;

they did not have children.

She has said that the pressures of her working life were a contributing factor, but not the major factor, in the breakup.

From 1983 to 1986, Sotomayor had an informal solo practice, dubbed Sotomayor & Associates, located in her Brooklyn apartment.

She performed legal consulting work, often for friends or family members.

In 1984, she entered private practice, joining the commercial litigation practice group of Pavia & Harcourt in Manhattan as an associate.

One of 30 attorneys in the law firm,

she specialized in intellectual property litigation,

international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

, and

arbitration

Arbitration is a formal method of dispute resolution involving a third party neutral who makes a binding decision. The third party neutral (the 'arbitrator', 'arbiter' or 'arbitral tribunal') renders the decision in the form of an 'arbitrati ...

.

She later said, "I wanted to complete myself as an attorney."

Although she had no

civil litigation experience, the firm recruited her heavily, and she learned quickly on the job.

She was eager to try cases and argue in court, rather than be part of a larger law firm.

Her clients were mostly international corporations doing business in the United States;

much of her time was spent tracking down and suing counterfeiters of

Fendi

Fendi Srl () is an Culture of Italy, Italian luxury goods, luxury fashion house producing fur, ready-to-wear, leather goods, shoes, fragrances, eyewear, timepieces and accessories. Founded in Rome in 1925 by fashion designers Edoardo Fendi and ...

goods.

In some cases, Sotomayor went on-site with the police to

Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

or

Chinatown to have illegitimate merchandise seized, in the latter instance pursuing a fleeing culprit while riding on a motorcycle.

She said at the time that Pavia & Harcourt's efforts were run "much like a drug operation", and the successful rounding up of thousands of counterfeit accessories in 1986 was celebrated by "Fendi Crush", a destruction-by-garbage-truck event at

Tavern on the Green.

At other times, she dealt with dry legal issues such as grain export contract disputes.

In a 1986 appearance on ''

Good Morning America

''Good Morning America'', often abbreviated as ''GMA'', is an American breakfast television, morning television program that is broadcast on American Broadcasting Company, ABC. It debuted on November 3, 1975, and first expanded to weekends wit ...

'' that profiled women ten years after college graduation, she said that the bulk of law work was drudgery, and that while she was content with her life, she had expected greater things of herself coming out of college.

In 1988 she became a partner at the firm;

she was paid well but not extravagantly.

She left in 1992 when she became a judge.

In addition to her law firm work, Sotomayor found visible public service roles.

She was not connected to the party bosses that typically picked people for such jobs in New York, and indeed she was registered as an

independent.

Instead, District Attorney Morgenthau, an influential figure, served as her patron.

In 1987,

Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor ...

Mario Cuomo appointed Sotomayor to the board of the

State of New York Mortgage Agency, which she served on until 1992.

As part of one of the largest urban rebuilding efforts in American history,

the agency helped low-income people get home mortgages and to provide insurance coverage for housing and

hospices for sufferers of AIDS.

Despite being the youngest member of a board composed of strong personalities, she involved herself in the details of the operation and was effective.

She was vocal in supporting the right to affordable housing, directing more funds to lower-income home owners, and in her skepticism about the effects of

gentrification

Gentrification is the process whereby the character of a neighborhood changes through the influx of more Wealth, affluent residents (the "gentry") and investment. There is no agreed-upon definition of gentrification. In public discourse, it has ...

, although in the end she voted in favor of most of the projects.

Sotomayor was appointed by Mayor

Ed Koch in 1988 as one of the founding members of the

New York City Campaign Finance Board, where she served for four years.

There she took a vigorous role

in the board's implementation of a voluntary scheme wherein local candidates received public matching funds in exchange for limits on contributions and spending and agreeing to greater financial disclosure.

Sotomayor showed no patience with candidates who failed to follow regulations and was more of a stickler for making campaigns follow those regulations than some of the other board members.

She joined in rulings that fined, audited, or reprimanded the mayoral campaigns of Koch,

David Dinkins

David Norman Dinkins (July 10, 1927 – November 23, 2020) was an American politician, lawyer, and author who served as the 106th mayor of New York City from 1990 to 1993.

Dinkins was among the more than 20,000 Montford Point Marine Associa ...

, and

Rudy Giuliani

Rudolph William Louis Giuliani ( , ; born May 28, 1944) is an American politician and Disbarment, disbarred lawyer who served as the 107th mayor of New York City from 1994 to 2001. He previously served as the United States Associate Attorney ...

.

Based upon another recommendation from Cabranes,

Sotomayor was a member of the board of directors of the

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund from 1980 to 1992.

There she was a top policy maker

who worked actively with the organization's lawyers on issues such as New York City hiring practices, police brutality, the death penalty, and voting rights.

The group achieved its most visible triumph when it successfully blocked a city primary election on the grounds that

New York City Council

The New York City Council is the lawmaking body of New York City in the United States. It has 51 members from 51 council districts throughout the five boroughs.

The council serves as a check against the mayor in a mayor-council government mod ...

boundaries diminished the power of minority voters.

During 1985 and 1986, Sotomayor served on the board of the

Maternity Center Association, a Manhattan-based non-profit group which focused on improving the quality of maternity care.

Federal district judge

Nomination and confirmation

Sotomayor had wanted to become a judge since she was in elementary school, and in 1991 she was recommended for a spot by Democratic New York senator

Daniel Patrick Moynihan

Daniel Patrick Moynihan (; March 16, 1927 – March 26, 2003) was an American politician, diplomat and social scientist. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he represented New York (state), New York in the ...

.

Moynihan had an unusual bipartisan arrangement with his fellow New York senator, Republican

Al D'Amato, whereby he would get to choose roughly one out of every four New York district court seats even though a Republican was in the White House.

Moynihan also wanted to fulfill a public promise he had made to get a Hispanic judge appointed for New York.

When Moynihan's staff recommended her to him, they said "Have we got a judge for you!"

Moynihan identified with her socio-economic and academic background and became convinced she would become the first Hispanic Supreme Court justice.

D'Amato became an enthusiastic backer of Sotomayor,

who was seen as politically centrist at the time.

Of the impending drop in salary from private practice, Sotomayor said: "I've never wanted to get adjusted to my income because I knew I wanted to go back to public service. And in comparison to what my mother earns and how I was raised, it's not modest at all."

Sotomayor was thus nominated on November 27, 1991, by President

George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

to a seat on the

U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York vacated by

John M. Walker Jr.Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally known as the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the United States Departm ...

hearings, led by a friendly Democratic majority, went smoothly for her in June 1992, with her pro bono activities winning praise from Senator

Ted Kennedy and her getting unanimous approval from the committee.

Then a Republican senator blocked her nomination and that of three others for a while in retaliation for an unrelated block Democrats had put on another nominee.

D'Amato objected strongly;

some weeks later, the block was dropped, and Sotomayor was confirmed by

unanimous consent

In parliamentary procedure, unanimous consent, also known as general consent, or in the case of the parliaments under the Westminster system, leave of the house (or leave of the senate), is a situation in which no member present objects to a propo ...

of the full

United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

on August 11, 1992, and received her commission the next day.

Sotomayor became the youngest judge in the Southern District

and the first Hispanic federal judge in New York State. She became the first Puerto Rican woman to serve as a judge in a U.S. federal court. She was one of seven women among the district's 58 judges.

She moved from

Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, back to the Bronx in order to live within her district.

Judgeship

Sotomayor generally kept a low public profile as a district court judge.

She showed a willingness to take anti-government positions in a number of cases, and during her first year in the seat, she received high ratings from liberal public-interest groups.

Other sources and organizations regarded her as a centrist during this period.

In criminal cases, she gained a reputation for tough sentencing and was not viewed as a pro-defense judge.

A

Syracuse University

Syracuse University (informally 'Cuse or SU) is a Private university, private research university in Syracuse, New York, United States. It was established in 1870 with roots in the Methodist Episcopal Church but has been nonsectarian since 1920 ...

study found that in such cases, Sotomayor generally handed out longer sentences than her colleagues, especially when

white-collar crime

The term "white-collar crime" refers to financially motivated, nonviolent or non-directly violent crime committed by individuals, businesses and government professionals. The crimes are believed to be committed by middle- or upper-class indivi ...

was involved. Fellow district judge

Miriam Goldman Cedarbaum was an influence on Sotomayor in adopting a narrow, "just the facts" approach to judicial decision-making.

As a trial judge, she garnered a reputation for being well-prepared in advance of a case and moving cases along a tight schedule.

Lawyers before her court viewed her as plain-spoken, intelligent, demanding, and sometimes somewhat unforgiving; one said, "She does not have much patience for people trying to snow her. You can't do it."

Notable rulings

On March 30, 1995, in ''Silverman v. Major League Baseball Player Relations Committee, Inc.'', Sotomayor issued a preliminary injunction against

Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball league composed of 30 teams, divided equally between the National League (baseball), National League (NL) and the American League (AL), with 29 in the United States and 1 in Canada. MLB i ...

, preventing it from unilaterally implementing a new

collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and labour rights, rights for ...

agreement and using

replacement players. Her ruling ended the

1994 baseball strike after 232 days, the day before the new season was scheduled to begin. The Second Circuit upheld Sotomayor's decision and denied the owners' request to stay the ruling.

The decision raised her profile,

won her the plaudits of baseball fans,

and had a lasting effect on the game. In the preparatory phase of the case, Sotomayor informed the lawyers of both sides that, "I hope none of you assumed ... that my lack of knowledge of any of the intimate details of your dispute meant I was not a baseball fan. You can't grow up in the South Bronx without knowing about baseball."

In ''Dow Jones v. Department of Justice'' (1995), Sotomayor sided with the ''

Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' (''WSJ''), also referred to simply as the ''Journal,'' is an American newspaper based in New York City. The newspaper provides extensive coverage of news, especially business and finance. It operates on a subscriptio ...

'' in its efforts to obtain and publish a photocopy of the last note left by former

Deputy White House Counsel Vince Foster. Sotomayor ruled that the public had "a substantial interest" in viewing the note and enjoined the

U.S. Justice Department

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a United States federal executive departments, federal executive department of the U.S. government that oversees the domestic enforcement of Law of the Unite ...

from blocking its release.

In ''

New York Times Co. v. Tasini'' (1997), freelance journalists sued the

New York Times Company for copyright infringement for ''The New York Times'' inclusion in an electronic archival database (

LexisNexis

LexisNexis is an American data analytics company headquartered in New York, New York. Its products are various databases that are accessed through online portals, including portals for computer-assisted legal research (CALR), newspaper searc ...

) of the work of freelancers it had published. Sotomayor ruled that the publisher had the right to license the freelancers' work. This decision was reversed on appeal, and the Supreme Court upheld the reversal; two dissenters (

John Paul Stevens

John Paul Stevens (April 20, 1920 – July 16, 2019) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1975 to 2010. At the time of his retirement, he was the second-oldes ...

and

Stephen Breyer) took Sotomayor's position.

In ''

Castle Rock Entertainment, Inc. v. Carol Publishing Group'' (also in 1997), Sotomayor ruled that a book of trivia from the television program ''

Seinfeld

''Seinfeld'' ( ) is an American television sitcom created by Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld that originally aired on NBC from July 5, 1989, to May 14, 1998, with a total of nine seasons consisting of List of Seinfeld episodes, 180 episodes. It ...

'' infringed on the copyright of the show's producer and did not constitute legal

fair use

Fair use is a Legal doctrine, doctrine in United States law that permits limited use of copyrighted material without having to first acquire permission from the copyright holder. Fair use is one of the limitations to copyright intended to bal ...

. The

United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (in case citations, 2d Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. Its territory covers the states of Connecticut, New York (state), New York, and Vermont, and it has ap ...

upheld Sotomayor's ruling.

Court of Appeals judge

Nomination and confirmation

On June 25, 1997, Sotomayor was nominated by President

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

to a seat on the

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which was vacated by

J. Daniel Mahoney.

Her nomination was initially expected to have smooth sailing,

with the

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary association, voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students in the United States; national in scope, it is not specific to any single jurisdiction. Founded in 1878, the ABA's stated acti ...

Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary giving her a "well qualified" professional assessment.

However, as ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' described, "

t became

T, or t, is the twentieth Letter (alphabet), letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the English alphabet, modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is English alphab ...

embroiled in the sometimes tortured judicial politics of the Senate."

Some in the Republican majority believed Clinton was eager to name the first Hispanic Supreme Court justice and that an easy confirmation to the appeals court would put Sotomayor in a better position for a possible Supreme Court nomination (despite there being no vacancy at the time nor any indication the Clinton administration was considering nominating her or any Hispanic). Therefore, the Republican majority decided to slow her confirmation.

Radio commentator

Rush Limbaugh

Rush Hudson Limbaugh III ( ; January 12, 1951 – February 17, 2021) was an American Conservatism in the United States, conservative political commentator who was the host of ''The Rush Limbaugh Show'', which first aired in 1984 and was nati ...

weighed in that Sotomayor was an ultraliberal who was on a "rocket ship" to the highest court.

During her September 1997 hearing before the

Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally known as the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the United States Departm ...

, Sotomayor parried strong questioning from some Republican members about

mandatory sentencing

Mandatory sentencing requires that people convicted of certain crimes serve a predefined term of imprisonment, removing the discretion of judges to take issues such as extenuating circumstances and a person's likelihood of rehabilitation into co ...

,

gay rights, and her level of respect for Supreme Court Justice

Clarence Thomas.

After a long wait, she was approved by the committee in March 1998, with only two dissensions.

However, in June 1998, the influential ''

Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' (''WSJ''), also referred to simply as the ''Journal,'' is an American newspaper based in New York City. The newspaper provides extensive coverage of news, especially business and finance. It operates on a subscriptio ...

'' editorial page opined that the Clinton administration intended to "get her on to the Second Circuit, then elevate her to the Supreme Court as soon as an opening occurs"; the editorial criticized two of her district court rulings and urged further delay of her confirmation. The Republican block continued.

Ranking Democratic committee member

Patrick Leahy

Patrick Joseph Leahy ( ; born March 31, 1940) is an American politician and attorney who represented Vermont in the United States Senate from 1975 to 2023. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he also was the pr ...

objected to Republican use of a

secret hold to slow down the Sotomayor nomination, and Leahy attributed that anonymous tactic to GOP reticence about publicly opposing a female Hispanic nominee.

The prior month, Leahy had triggered a procedural delay in the confirmation of fellow Second Circuit nominee

Chester J. Straub—who, although advanced by Clinton and supported by Senator Moynihan, was considered much more acceptable by Republicans—in an unsuccessful effort to force earlier consideration of the Sotomayor confirmation.

During 1998, several Hispanic organizations organized a petition drive in New York State, generating hundreds of signatures from New Yorkers to try to convince New York Republican senator

Al D'Amato to push the Senate leadership to bring Sotomayor's nomination to a vote.

D'Amato, a backer of Sotomayor to begin with and additionally concerned about being up for re-election that year,

helped move Republican leadership.

Her nomination had been pending for over a year when

Majority Leader Trent Lott

Chester Trent Lott Sr. (born October 9, 1941) is an American lobbyist, lawyer, author, and politician who represented Mississippi in the United States House of Representatives from 1973 to 1989 and in the United States Senate from 1989 to 2007. ...

scheduled the vote.

With complete Democratic support, and support from 25 Republican senators including Judiciary chair

Orrin Hatch,

Sotomayor was confirmed on October 2, 1998, by a 67–29 vote. She received her commission on October 7.

The confirmation experience left Sotomayor somewhat angry; she said shortly afterwards that during the hearings, Republicans had assumed her political beliefs based on her being a Latina: "That series of questions, I think, were symbolic of a set of expectations that some people had

hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

I must be liberal. It is stereotyping, and stereotyping is perhaps the most insidious of all problems in our society today."

Judgeship

Over her 10 years on the Second Circuit, Sotomayor heard appeals in more than 3,000 cases and wrote about 380 opinions when she was in the majority.

The Supreme Court reviewed five of those, reversing three and affirming two

—not high numbers for an appellate judge of that many years

and a typical percentage of reversals.

Sotomayor's circuit court rulings led to her being considered a political

centrist by the ''

ABA Journal''

and other sources and organizations.

Several lawyers, legal experts, and news organizations identified her as someone with liberal inclinations.

The Second Circuit's caseload typically skewed more toward business and securities law rather than hot-button social or constitutional issues.

Sotomayor tended to write narrow, practiced rulings that relied on close application of the law to the facts of a case rather than import general philosophical viewpoints.

A

Congressional Research Service

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) is a public policy research institute of the United States Congress. Operating within the Library of Congress, it works primarily and directly for members of Congress and their committees and staff on a ...

analysis found that Sotomayor's rulings defied easy ideological categorization, but did show an adherence to precedent and an avoidance of overstepping the circuit court's judicial role. Unusually, Sotomayor read through all the supporting documents of cases under review; her lengthy rulings explored every aspect of a case and tended to feature leaden, ungainly prose. Some legal experts have said that Sotomayor's attention to detail and re-examination of the facts of a case came close to overstepping the traditional role of appellate judges.

Across some 150 cases involving business and civil law, Sotomayor's rulings were generally unpredictable and not consistently pro-business or anti-business. Sotomayor's influence in the federal judiciary, as measured by the number of citations of her rulings by other judges and in law review articles, increased significantly during the length of her appellate judgeship and was greater than that of some other prominent federal appeals court judges. Two academic studies showed that the percentage of Sotomayor's decisions that overrode policy decisions by elected branches was the same as or lower than that of other circuit judges.

Sotomayor was a member of the Second Circuit Task Force on Gender, Racial and Ethnic Fairness in the Courts.

In October 2001, she presented the annual Judge Mario G. Olmos Memorial Lecture at

UC Berkeley School of Law

The University of California, Berkeley School of Law (Berkeley Law) is the Law school in the United States, law school of the University of California, Berkeley. The school was commonly referred to as "Boalt Hall" for many years, although it was ...

;

titled "A Latina Judge's Voice"; it was published in the ''

Berkeley La Raza Law Journal'' the following spring.

In the speech, she discussed the characteristics of her Latina upbringing and culture and the history of minorities and women ascending to the federal bench.

She said the low number of minority women on the federal bench at that time was "shocking".

She then discussed at length how her own experiences as a Latina might affect her decisions as a judge.

In any case, her background in activism did not necessarily influence her rulings: in a study of 50 racial discrimination cases brought before her panel, 45 were rejected, with Sotomayor never filing a dissent.

An expanded study showed that Sotomayor decided 97 cases involving a claim of discrimination and rejected those claims nearly 90 percent of the time. Another examination of Second Circuit split decisions on cases that dealt with race and discrimination showed no clear ideological pattern in Sotomayor's opinions.

In the Court of Appeals seat, Sotomayor gained a reputation for vigorous and blunt behavior toward lawyers appealing before her, sometimes to the point of brusque and curt treatment or testy interruptions.

She was known for extensive preparation for oral arguments and for running a "hot bench", where judges ask lawyers plenty of questions.

Unprepared lawyers suffered the consequences, but the vigorous questioning was an aid to lawyers seeking to tailor their arguments to the judge's concerns.

The 2009 ''Almanac of the Federal Judiciary'', which collected anonymous evaluations of judges by lawyers who appear before them, contained a wide range of reactions to Sotomayor.

Comments also diverged among lawyers willing to be named. Attorney Sheema Chaudhry said, "She's brilliant and she's qualified, but I just feel that she can be very, how do you say, temperamental."

Defense lawyer

Gerald B. Lefcourt said, "She used her questioning to make a point, as opposed to really looking for an answer to a question she did not understand."

In contrast, Second Circuit Judge

Richard C. Wesley said that his interactions with Sotomayor had been "totally antithetical to this perception that has gotten some traction that she is somehow confrontational."

Second Circuit Judge and former teacher

Guido Calabresi said his tracking showed that Sotomayor's questioning patterns were no different from those of other members of the court and added, "Some lawyers just don't like to be questioned by a woman.

he criticismwas sexist, plain and simple."

Sotomayor's

law clerk

A law clerk, judicial clerk, or judicial assistant is a person, often a lawyer, who provides direct counsel and assistance to a lawyer or judge by Legal research, researching issues and drafting legal opinions for cases before the court. Judicial ...

s regarded her as a valuable and strong mentor, and she said that she viewed them like family.

In 2005, Senate Democrats suggested Sotomayor, among others, to President

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

as an acceptable nominee to fill the seat of retiring Supreme Court Justice

Sandra Day O'Connor.

Notable rulings

Abortion

In the 2002 decision ''

Center for Reproductive Law and Policy v. Bush'',

['' Center for Reproductive Law and Policy v. Bush'']

304 F.3d 183

(2d Cir. 2002) Sotomayor upheld the

Bush administration's implementation of the

Mexico City Policy, which states that "the United States will no longer contribute to separate nongovernmental organizations which perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning in other nations." Sotomayor held that the policy did not constitute a violation of

equal protection

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "nor shall any State... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal pr ...

, as "the government is free to favor the anti-abortion position over the pro-choice position, and can do so with public funds."

First Amendment rights

In ''

Pappas v. Giuliani'' (2002), Sotomayor dissented from her colleagues' ruling that the

New York Police Department

The City of New York Police Department, also referred to as New York City Police Department (NYPD), is the primary law enforcement agency within New York City. Established on May 23, 1845, the NYPD is the largest, and one of the oldest, munic ...

could terminate from his desk job an employee who sent racist materials through the mail. Sotomayor argued that the

First Amendment protected speech by the employee "away from the office, on

isown time", even if that speech was "offensive, hateful, and insulting", and that therefore the employee's First Amendment claim should have gone to trial rather than being dismissed on summary judgment.

In 2005, Sotomayor wrote the opinion for ''United States v. Quattrone''.

[''United States v. Quattrone'']

402 F.3d 304

(2d Cir. 2005). Frank Quattrone had been on trial on charges of obstructing investigations related to technology IPOs. After the first trial ended in a deadlocked jury and a mistrial, some members of the media had wanted to publish the names of the jurors deciding Quattrone's case, and a district court had issued an order barring the publication, even though their names had previously been disclosed in open court. In ''United States v. Quattrone'', Sotomayor wrote the opinion for the Second Circuit panel striking down this order on First Amendment grounds, stating that the media should be free to publish the names of the jurors. Sotomayor held that although it was important to protect the fairness of the retrial, the district court's order was an unconstitutional prior restraint on free speech and violated the right of the press "to report freely on events that transpire in an open courtroom".

In 2008, Sotomayor was on a three-judge panel in ''

Doninger v. Niehoff''

['' Doninger v. Niehoff'']

Doninger v. Niehoff, 527 F.3d 41

(2d Cir. 2008). that unanimously affirmed, in an opinion written by Second Circuit Judge

Debra Livingston, the district court's judgment that

Lewis S. Mills High School did not violate the First Amendment rights of a student when it barred her from running for student government after she called the superintendent and other school officials "douchebags" in a blog post written while off-campus that encouraged students to call an administrator and "piss her off more".

Judge Livingston held that the district judge did not abuse her discretion in holding that the student's speech "foreseeably create

a risk of substantial disruption within the school environment", which is the precedent in the Second Circuit for when schools may regulate off-campus speech.

Although Sotomayor did not write this opinion, she has been criticized by some who disagree with it.

Second Amendment rights

Sotomayor was part of the three-judge Second Circuit panel that affirmed the district court's ruling in ''Maloney v. Cuomo'' (2009).

[''Maloney v. Cuomo'', 554 F.3d 56 (2d Cir. 2009)] Maloney was arrested for possession of

nunchucks, which at the time were illegal in New York; Maloney argued that this law violated his

Second Amendment right to bear arms. The Second Circuit's ''

per curiam'' opinion noted that the Supreme Court has not, so far, ever held that the Second Amendment is binding against state governments. On the contrary, in ''

Presser v. Illinois'' (1886), the Supreme Court held that the Second Amendment "is a limitation only upon the power of Congress and the national government, and not upon that of the state".

With respect to the ''Presser v. Illinois'' precedent, the panel stated that only the Supreme Court has "the prerogative of overruling its own decisions,"

and the recent Supreme Court case of ''

District of Columbia v. Heller'' (which struck down the District's gun ban as unconstitutional) did "not invalidate this longstanding principle".

The panel upheld the lower court's decision dismissing Maloney's challenge to New York's law against possession of nunchucks. On June 2, 2009, a

Seventh Circuit panel, including the prominent and heavily cited judges

Richard Posner

Richard Allen Posner (; born January 11, 1939) is an American legal scholar and retired United States circuit judge who served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit from 1981 to 2017. A senior lecturer at the University of Chicag ...

and

Frank Easterbrook, unanimously agreed with ''Maloney v. Cuomo'', citing the case in their decision turning back a challenge to Chicago's gun laws and noting the Supreme Court precedents remain in force until altered by the Supreme Court itself.

Fourth Amendment rights

In ''N.G. & S.G. ex rel. S.C. v. Connecticut'' (2004),

[''N.G. & S.G. ex rel. S.C. v. Connecticut'']

382 F.3d. 225

(2d Cir. 2004). Sotomayor dissented from her colleagues' decision to uphold a series of strip searches of "troubled adolescent girls" in juvenile detention centers. While Sotomayor agreed that some of the strip searches at issue in the case were lawful, she would have held that due to "the severely intrusive nature of strip searches",

they should not be allowed "in the absence of individualized suspicion, of adolescents who have never been charged with a crime".

She argued that an "individualized suspicion" rule was more consistent with Second Circuit precedent than the majority's rule.

In ''Leventhal v. Knapek'' (2001),

[''Leventhal v. Knapek'']

266 F.3d 64

(2d Cir. 2001). Sotomayor rejected a

Fourth Amendment challenge by a

U.S. Department of Transportation employee whose employer searched his office computer. She held that, "Even though

he employeehad some expectation of privacy in the contents of his office computer, the investigatory searches by the DOT did not violate his Fourth Amendment rights"

because here "there were reasonable grounds to believe" that the search would reveal evidence of "work-related misconduct".

Alcohol in commerce

In 2004, Sotomayor was part of the judge panel that ruled in ''

Swedenburg v. Kelly'' that New York's law prohibiting out-of-state wineries from shipping directly to consumers in New York was constitutional even though in-state wineries were allowed to. The case, which invoked the

21st Amendment, was appealed and attached to another case. The case reached the Supreme Court later on as ''Swedenburg v. Kelly'' and was overruled in a 5–4 decision that found the law was discriminatory and unconstitutional.

Employment discrimination

Sotomayor was involved in the high-profile case ''

Ricci v. DeStefano'' that initially upheld the right of the

City of New Haven to throw out its test for firefighters and start over with a new test, because the city believed the test had a "disparate impact"

on minority firefighters. (No black firefighters qualified for promotion under the test, whereas some had qualified under tests used in previous years.) The city was concerned that minority firefighters might sue under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The city chose not to certify the test results and a lower court had previously upheld the city's right to do this. Several white firefighters and one Hispanic firefighter who had passed the test, including the lead plaintiff who has dyslexia and had put extra effort into studying, sued the City of New Haven, claiming that their rights were violated. A Second Circuit panel that included Sotomayor first issued a brief, unsigned

summary order (not written by Sotomayor) affirming the lower court's ruling. Sotomayor's former mentor

José A. Cabranes, by now a fellow judge on the court, objected to this handling and requested that the court hear it

en banc

In law, an ''en banc'' (; alternatively ''in banc'', ''in banco'' or ''in bank''; ) session is when all the judges of a court sit to hear a case, not just one judge or a smaller panel of judges.

For courts like the United States Courts of Appeal ...

.

Sotomayor voted with a 7–6 majority not to rehear it and a slightly expanded ruling was issued, but a strong dissent by Cabranes led to the case reaching the Supreme Court in 2009.

There it was overruled in a 5–4 decision that found the white firefighters had been victims of racial discrimination when they were denied promotion.

Business

In ''

Clarett v. National Football League'' (2004), Sotomayor upheld the

National Football League

The National Football League (NFL) is a Professional gridiron football, professional American football league in the United States. Composed of 32 teams, it is divided equally between the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National ...

's eligibility rules requiring players to wait three full seasons after high school graduation before entering the NFL draft.

Maurice Clarett challenged these rules, which were part of the collective bargaining agreement between the NFL and its players, on antitrust grounds. Sotomayor held that Clarett's claim would upset the established "federal labor law favoring and governing the collective bargaining process".

In ''

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. v. Dabit'' (2005), Sotomayor wrote a unanimous opinion that the

Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act of 1998 did not preempt

class action

A class action is a form of lawsuit.

Class Action may also refer to:

* ''Class Action'' (film), 1991, starring Gene Hackman and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio

* Class Action (band), a garage house band

* "Class Action" (''Teenage Robot''), a 2002 e ...

claims in state courts by stockbrokers alleging misleading inducement to buy or sell stocks.

The Supreme Court handed down an 8–0 decision stating that the Act did preempt such claims, thereby overruling Sotomayor's decision.

In ''

Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp.'' (2001), she ruled that the license agreement of Netscape's Smart Download software did not constitute a binding contract because the system did not give "sufficient notice" to the user.

Civil rights

In ''

Correctional Services Corp. v. Malesko'' (2000), Sotomayor, writing for the court, supported the right of an individual to sue a private corporation working on behalf of the federal government for alleged violations of that individual's constitutional rights. Reversing a lower court decision, Sotomayor found that the ''

Bivens'' doctrine—which allows suits against individuals working for the federal government for constitutional rights violations—could be applied to the case of a former prisoner seeking to sue the private company operating the federal halfway house facility in which he resided. The Supreme Court reversed Sotomayor's ruling in a 5–4 decision, saying that the ''Bivens'' doctrine could not be expanded to cover private entities working on behalf of the federal government. Justices Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer dissented, siding with Sotomayor's original ruling.

In ''Gant v. Wallingford Board of Education'' (1999), the parents of a black student alleged that he had been harassed due to his race and had been discriminated against when he was transferred from a first grade class to a kindergarten class without parental consent, while similarly situated white students were treated differently. Sotomayor agreed with the dismissal of the harassment claims due to lack of evidence, but would have allowed the discrimination claim to go forward. She wrote in dissent that the grade transfer was "contrary to the school's established policies" as well as its treatment of white students, which "supports the inference that race discrimination played a role".

Property rights

In ''Krimstock v. Kelly'' (2002), Sotomayor wrote an opinion halting New York City's practice of seizing the motor vehicles of drivers accused of driving while intoxicated and some other crimes and holding those vehicles for "months or even years" during criminal proceedings. Noting the importance of cars to many individuals' livelihoods or daily activities, she held that it violated individuals' due process rights to hold the vehicles without permitting the owners to challenge the city's continued possession of their property.

In ''Brody v. Village of Port Chester'' (2003 and 2005), a takings case, Sotomayor first ruled in 2003 for a unanimous panel that a property owner in

Port Chester, New York

Port Chester is a administrative divisions of New York#Village, village in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York and the largest part of the town of Rye (town), New York, Rye in Westchester County, New York, Westchester County by populati ...

was permitted to challenge the state's Eminent Domain Procedure Law. A district court subsequently rejected the plaintiff's claims and upon appeal the case found itself again with the Second Circuit. In 2005, Sotomayor ruled with a panel majority that the property owner's due process rights had been violated by lack of adequate notice to him of his right to challenge a village order that his land should be used for a redevelopment project. However, the panel supported the village's taking of the property for public use.

In ''Didden v. Village of Port Chester'' (2006), an unrelated case brought about by the same town's actions, Sotomayor joined a unanimous panel's summary order to uphold a trial court's dismissal—due to a statute of limitations lapse—of a property owner's objection to his land being condemned for a redevelopment project. The ruling further said that even without the lapse, the owner's petition would be denied due to application of the Supreme Court's recent ''

Kelo v. City of New London'' ruling. The Second Circuit's reasoning drew criticism from

libertarian commentators.

Supreme Court justice

Nomination and confirmation

Following

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

's

2008 presidential election victory, speculation arose that Sotomayor could be a leading candidate for a Supreme Court seat.

New York Senators

Charles Schumer and

Kirsten Gillibrand

Kirsten Elizabeth Gillibrand (; ; born December 9, 1966) is an American lawyer and politician serving as the Seniority in the United States Senate, junior United States Senate, United States senator from New York (state), New York since 2009 ...

wrote a joint letter to Obama urging him to appoint Sotomayor, or alternatively Interior Secretary

Ken Salazar, to the Supreme Court if a vacancy should arise during his term.

The White House first contacted Sotomayor on April 27, 2009, about the possibility of her nomination.

On April 30, 2009, Justice

David Souter's retirement plans leaked to the press, and Sotomayor received early attention as a possible nominee for Souter's seat to be vacated in June 2009.

In May 2009, however, Harvard Law Professor

Laurence Tribe urged Obama not to appoint Sotomayor, writing that "she's not nearly as smart as she seems to think she is," and that "her reputation for being something of a bully could well make her liberal impulses backfire and simply add to the fire power of the Roberts/Alito/Scalia/Thomas wing of the court."

On May 25, Obama informed Sotomayor of his choice; she later said, "I had my

andover my chest, trying to calm my beating heart, literally." On May 26, 2009, Obama nominated her. She became only the second jurist to be nominated to three different judicial positions by three different presidents. The selection appeared to closely match Obama's presidential campaign promise that he would nominate judges who had "the heart, the empathy, to recognize what it's like to be a teenage mom. The empathy to understand what it's like to be poor, or African-American, or gay, or disabled, or old."

Sotomayor's nomination won praise from Democrats and liberals, and Democrats appeared to have sufficient votes to confirm her.

The strongest criticism of her nomination came from conservatives and some Republican senators regarding a line she had used in similar forms in a number of her speeches, particularly in a 2001

Berkeley Law lecture:

"I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn't lived that life."

Sotomayor had made similar remarks in other speeches between 1994 and 2003, including one she submitted as part of her confirmation questionnaire for the Court of Appeals in 1998, but they had attracted little attention at the time. The remark now became widely known.

The rhetoric quickly became inflamed, with radio commentator

Rush Limbaugh

Rush Hudson Limbaugh III ( ; January 12, 1951 – February 17, 2021) was an American Conservatism in the United States, conservative political commentator who was the host of ''The Rush Limbaugh Show'', which first aired in 1984 and was nati ...

and former Republican

Speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich

Newton Leroy Gingrich (; né McPherson; born June 17, 1943) is an American politician and author who served as the List of speakers of the United States House of Representatives, 50th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1 ...

calling Sotomayor a "racist" (although the latter later backtracked from that claim), while

John Cornyn and other Republican senators denounced such attacks but said that Sotomayor's approach was troubling.

Backers of Sotomayor offered a variety of explanations in defense of the remark, and

White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs stated that Sotomayor's word choice in 2001 had been "poor".

Sotomayor subsequently clarified her remark through

Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally known as the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the United States Departm ...

chair

Patrick Leahy

Patrick Joseph Leahy ( ; born March 31, 1940) is an American politician and attorney who represented Vermont in the United States Senate from 1975 to 2023. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he also was the pr ...

, saying that while life experience shapes who one is, "ultimately and completely" a judge follows the law regardless of personal background.

Of her cases, the Second Circuit rulings in ''

Ricci v. DeStefano'' received the most attention during the early nomination discussion,

motivated by the Republican desire to focus on the reverse racial discrimination aspect of the case.

In the midst of her confirmation process the Supreme Court overturned that ruling on June 29.

A third line of Republican attack against Sotomayor was based on her ruling in ''Maloney v. Cuomo'' and was motivated by gun ownership advocates concerned about her interpretation of Second Amendment rights.

[Coyle, ''The Roberts Court'', pp. 254–255.] Some of the fervor with which conservatives and Republicans viewed the Sotomayor nomination was due to their grievances over the history of federal judicial nomination battles going back to the 1987

Robert Bork Supreme Court nomination.

A

Gallup poll released a week after the nomination showed 54% of Americans in favor of Sotomayor's confirmation compared with 28% in opposition. A June 12

Fox News

The Fox News Channel (FNC), commonly known as Fox News, is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conservatism in the United States, conservative List of news television channels, news and political commentary Television stati ...

poll showed 58% of the public disagreeing with her "wise Latina" remark but 67% saying the remark should not disqualify her from serving on the Supreme Court.

The

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary association, voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students in the United States; national in scope, it is not specific to any single jurisdiction. Founded in 1878, the ABA's stated acti ...

gave her a unanimous "well qualified" assessment, its highest mark for professional qualification.

Following the ''Ricci'' overruling,

Rasmussen Reports and

CNN/

Opinion Research polls showed that the public was now sharply divided, largely along partisan and ideological lines, as to whether Sotomayor should be confirmed.

Sotomayor's confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee began on July 13, 2009, during which she backed away from her "wise Latina" remark, declaring it "a rhetorical flourish that fell flat" and stating that "I do not believe that any ethnic, racial or gender group has an advantage in sound judgment."