Somalia Division One on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Somalia, ,

Provisional Constitution

, (; ), is a

Somalia was likely one of the first lands to be settled by early humans due to its location. Hunter-gatherers who would later migrate out of Africa likely settled here before their migrations. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished here. The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BCE. The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterized in 1909 as important artifacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.

According to linguists, the first

Somalia was likely one of the first lands to be settled by early humans due to its location. Hunter-gatherers who would later migrate out of Africa likely settled here before their migrations. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished here. The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BCE. The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterized in 1909 as important artifacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.

According to linguists, the first

by James Talboys Wheeler, pg 1xvi, 315, 526 The Macrobians were warrior herders and seafarers. According to Herodotus' account, the After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab and Somali merchants agreed with the Romans to bar Indian ships from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula to protect the interests of Somali and Arab merchants in the lucrative commerce between the Red and Mediterranean Seas.. However, Indian merchants continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from Roman interference. For centuries, Indian merchants brought large quantities of cinnamon to Somalia and Arabia from

After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab and Somali merchants agreed with the Romans to bar Indian ships from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula to protect the interests of Somali and Arab merchants in the lucrative commerce between the Red and Mediterranean Seas.. However, Indian merchants continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from Roman interference. For centuries, Indian merchants brought large quantities of cinnamon to Somalia and Arabia from

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of Mecca fleeing prosecution during the first

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of Mecca fleeing prosecution during the first

Adal's headquarters were again relocated the following century, this time southward to

Adal's headquarters were again relocated the following century, this time southward to

In the late 19th century, after the

In the late 19th century, after the

Following World War II, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland as protectorates. In 1945, during the

Following World War II, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland as protectorates. In 1945, during the

Alongside Barre, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination was led by Lieutenant Colonel

Alongside Barre, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination was led by Lieutenant Colonel

''The New Communist Third World: an essay in political economy''

Taylor & Francis, p. 279 . The revolutionary army established large-scale public works programs and successfully implemented an urban and rural literacy campaign, which helped dramatically increase the literacy rate. In addition to a nationalization program of industry and land, the new regime's foreign policy placed an emphasis on Somalia's traditional and religious links with the Arab world, eventually joining the Arab League in February, 1974. That same year, Barre also served as chairman of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor of the

As the moral authority of Barre's government was gradually eroded, many Somalis became disillusioned with life under military rule. By the mid-1980s, resistance movements supported by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration had sprung up across the country. Barre responded by ordering punitive measures against those he perceived as locally supporting the guerrillas, especially in the northern regions. The clampdown included bombing of cities, with the northwestern administrative centre of

As the moral authority of Barre's government was gradually eroded, many Somalis became disillusioned with life under military rule. By the mid-1980s, resistance movements supported by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration had sprung up across the country. Barre responded by ordering punitive measures against those he perceived as locally supporting the guerrillas, especially in the northern regions. The clampdown included bombing of cities, with the northwestern administrative centre of  Many of the opposition groups subsequently began competing for influence in the power vacuum that followed the ouster of Barre's regime. In the south, armed factions led by USC commanders General Mohamed Farah Aidid and Ali Mahdi Mohamed, in particular, clashed as each sought to exert authority over the capital. In 1991, a multi-phased international conference on Somalia was held in neighbouring Djibouti. Aidid boycotted the first meeting in protest.

Owing to the legitimacy bestowed on Muhammad by the Djibouti conference, he was subsequently recognized by the international community as the new President of Somalia. Djibouti,

Many of the opposition groups subsequently began competing for influence in the power vacuum that followed the ouster of Barre's regime. In the south, armed factions led by USC commanders General Mohamed Farah Aidid and Ali Mahdi Mohamed, in particular, clashed as each sought to exert authority over the capital. In 1991, a multi-phased international conference on Somalia was held in neighbouring Djibouti. Aidid boycotted the first meeting in protest.

Owing to the legitimacy bestowed on Muhammad by the Djibouti conference, he was subsequently recognized by the international community as the new President of Somalia. Djibouti,

In 2006, the

In 2006, the

Between 31 May and 9 June 2008, representatives of Somalia's federal government and the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia (ARS) participated in peace talks in Djibouti brokered by the former United Nations Special Envoy to Somalia, Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah. The conference ended with a signed agreement calling for the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops in exchange for the cessation of armed confrontation. Parliament was subsequently expanded to 550 seats to accommodate ARS members, which then elected Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, as president.

Between 31 May and 9 June 2008, representatives of Somalia's federal government and the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia (ARS) participated in peace talks in Djibouti brokered by the former United Nations Special Envoy to Somalia, Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah. The conference ended with a signed agreement calling for the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops in exchange for the cessation of armed confrontation. Parliament was subsequently expanded to 550 seats to accommodate ARS members, which then elected Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, as president.

With the help of a small team of African Union troops, the TFG began a Somali Civil War (2009–present), counteroffensive in February 2009 to assume full control of the southern half of the country. To solidify its rule, the TFG formed an alliance with the Islamic Courts Union, other members of the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia, and Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a, a moderate Sufism, Sufi militia. Furthermore, Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam, the two main Islamist groups in opposition, began to fight amongst themselves in mid-2009. As a truce, in March 2009, the TFG announced that it would re-implement Shari'a as the nation's official judicial system. However, conflict continued in the southern and central parts of the co

With the help of a small team of African Union troops, the TFG began a Somali Civil War (2009–present), counteroffensive in February 2009 to assume full control of the southern half of the country. To solidify its rule, the TFG formed an alliance with the Islamic Courts Union, other members of the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia, and Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a, a moderate Sufism, Sufi militia. Furthermore, Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam, the two main Islamist groups in opposition, began to fight amongst themselves in mid-2009. As a truce, in March 2009, the TFG announced that it would re-implement Shari'a as the nation's official judicial system. However, conflict continued in the southern and central parts of the co

Osmanya script

The Osmanya script ( so, Farta Cismaanya 𐒍𐒖𐒇𐒂𐒖 𐒋𐒘𐒈𐒑𐒛𐒒𐒕𐒖), also known as Far Soomaali (𐒍𐒖𐒇 𐒘𐒝𐒈𐒑𐒛𐒘, "Somali writing") and, in Arabic, as ''al-kitābah al-ʿuthmānīyah'' (الكتا ...

: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constitution

, (; ), is a

country

A country is a distinct part of the world, such as a state, nation, or other political entity. It may be a sovereign state or make up one part of a larger state. For example, the country of Japan is an independent, sovereign state, whil ...

in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

. The country is bordered by Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the Er ...

to the west, Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, جيبوتي ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Re ...

to the northwest, the Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden ( ar, خليج عدن, so, Gacanka Cadmeed 𐒅𐒖𐒐𐒕𐒌 𐒋𐒖𐒆𐒗𐒒) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Chan ...

to the north, the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

to the east, and Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

to the southwest. Somalia has the longest coastline on Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

's mainland. Its terrain consists mainly of plateaus, plains, and highlands. Hot conditions prevail year-round, with periodic monsoon winds and irregular rainfall. Somalia has an estimated population of around million, of which over 2 million live in the capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

and largest city Mogadishu

Mogadishu (, also ; so, Muqdisho or ; ar, مقديشو ; it, Mogadiscio ), locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port connecting traders across the Indian Oc ...

, and has been described as Africa's most culturally homogeneous country. Around 85% of its residents are ethnic Somalis

The Somalis ( so, Soomaalida 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖, ar, صوماليون) are an ethnic group native to the Horn of Africa who share a common ancestry, culture and history. The Lowland East Cushitic Somali language is the shared mo ...

, who have historically inhabited the country's north. Ethnic minorities are largely concentrated in the south.. The official languages of Somalia are Somali

Somali may refer to:

Horn of Africa

* Somalis, an inhabitant or ethnicity associated with Greater Somali Region

** Proto-Somali, the ancestors of modern Somalis

** Somali culture

** Somali cuisine

** Somali language, a Cushitic language

** Soma ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

. Most people in the country are Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abra ...

, the majority of them Sunni..

In antiquity, Somalia was an important commercial center. It is among the most probable locations of the ancient Land of Punt

The Land of Punt ( Egyptian: ''pwnt''; alternate Egyptological readings ''Pwene''(''t'') /pu:nt/) was an ancient kingdom known from Ancient Egyptian trade records. It produced and exported gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory ...

. During the Middle Ages, several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade, including the Ajuran Sultanate

The Ajuran Sultanate ( so, Saldanadda Ajuuraan, ar, سلطنة الأجورانية), also natively referred-to as Ajuuraan, and often simply Ajuran, was a Somali Empire in the Middle Ages in the Horn of Africa that dominated the trade in th ...

, the Adal Sultanate

The Adal Sultanate, or the Adal Empire or the ʿAdal or the Bar Saʿad dīn (alt. spelling ''Adel Sultanate, ''Adal ''Sultanate'') () was a medieval Sunni Muslim Empire which was located in the Horn of Africa. It was founded by Sabr ad-Din ...

, and the Sultanate of the Geledi

The Sultanate of the Geledi ( so, Saldanadda Geledi, ar, سلطنة غلدي) also known as the Gobroon Dynasty Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years - Virginia Luling (2002) Page 229 was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of th ...

.

In the late 19th century, Somali Sultanates like the Isaaq Sultanate

The Isaaq Sultanate ( so, Saldanadda Isaaq, Wadaad: , ar, السلطنة الإسحاقية) was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries. It spanned the territories of the Isaaq clan in modern- ...

and the Majeerteen Sultanate

The Majeerteen Sultanate ( so, Suldanadda Majeerteen 𐒈𐒚𐒐𐒆𐒖𐒒𐒖𐒆𐒆𐒖 𐒑𐒖𐒃𐒜𐒇𐒂𐒜𐒒, lit=Boqortooyada Majerteen, ar, سلطنة مجرتين), also known as Majeerteen Kingdom or Majeerteenia and Migiu ...

were colonized by both the Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

and British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English ...

Empire. European colonists merged the tribal territories into two colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state' ...

, which were Italian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th cent ...

and the British Somaliland Protectorate

British Somaliland, officially the Somaliland Protectorate ( so, Dhulka Maxmiyada Soomaalida ee Biritishka), was a British protectorate in present-day Somaliland. During its existence, the territory was bordered by Italian Somalia, French S ...

. Meanwhile, in the interior, the Dervishes led by Mohammed Abdullah Hassan

Sayid Mohamed Abdullahi Hassan ( so, Sayid Maxamed Cabdulle Xasan; 1856–1920) was a Somali religious and military leader of the Dervish movement, which led a two-decade long confrontation with various colonial empires including the British, ...

engaged in a two-decade confrontation against Abyssinia, Italian Somaliland, and British Somaliland and were finally defeated in the 1920 Somaliland Campaign.Diiwaanka gabayadii, 1856–1921, Maxamad Cabdulle Xasan · 1999, PAGE 219 Italy acquired full control of the northeastern, central, and southern parts of the area after successfully waging the Campaign of the Sultanates against the ruling Majeerteen Sultanate

The Majeerteen Sultanate ( so, Suldanadda Majeerteen 𐒈𐒚𐒐𐒆𐒖𐒒𐒖𐒆𐒆𐒖 𐒑𐒖𐒃𐒜𐒇𐒂𐒜𐒒, lit=Boqortooyada Majerteen, ar, سلطنة مجرتين), also known as Majeerteen Kingdom or Majeerteenia and Migiu ...

and Sultanate of Hobyo

The Sultanate of Hobyo ( so, Saldanadda Hobyo, ar, سلطنة هوبيو), also known as the Sultanate of Obbia,''New International Encyclopedia'', Volume 21, (Dodd, Mead: 1916), p.283. was a 19th-century Somali kingdom in present-day northeaste ...

. In 1960, the two territories united to form the independent Somali Republic

The Somali Republic ( so, Jamhuuriyadda Soomaaliyeed; it, Repubblica Somala; ar, الجمهورية الصومالية, Jumhūriyyat aṣ-Ṣūmālīyyah) was a sovereign state composed of Somalia and Somaliland, following the unification ...

under a civilian government.''The Illustrated Library of The World and Its Peoples: Africa, North and East'', Greystone Press: 1967, p. 338.

Siad Barre

Mohamed Siad Barre ( so, Maxamed Siyaad Barre, Osmanya script: ; ar, محمد سياد بري; c. 1910 – 2 January 1995) was a Somali head of state and general who served as the 3rd president of the Somali Democratic Republic from 1969 to 1 ...

of the Supreme Revolutionary Council seized power in 1969 and established the Somali Democratic Republic

The Somali Democratic Republic ( so, Jamhuuriyadda Dimuqraadiya Soomaaliyeed; ar, الجمهورية الديمقراطية الصومالية, ; it, Repubblica Democratica Somala) was the name that the Socialism, socialist military government ...

, brutally attempting to squash the Somaliland War of Independence

The Somaliland War of Independence ( so, Dagaalkii Xoraynta Soomaaliland, lit=Somaliland Liberation War) was a rebellion waged by the Somali National Movement against the ruling military junta in Somalia led by General Siad Barre lasting from it ...

in the north of the country. The SRC subsequently collapsed 22 years later, in 1991, with the onset of the Somali Civil War

The Somali Civil War ( so, Dagaalkii Sokeeye ee Soomaaliya; ar, الحرب الأهلية الصومالية ) is an ongoing civil war that is taking place in Somalia. It grew out of resistance to the military junta which was led by Siad Ba ...

and Somaliland soon declared independence. Somaliland still controls the northwestern portion of Somalia representing just over 27% of its territory. Since this period most regions returned to customary and religious law

Religious law includes ethical and moral codes taught by religious traditions. Different religious systems hold sacred law in a greater or lesser degree of importance to their belief systems, with some being explicitly antinomian whereas other ...

. In the early 2000s, a number of interim federal administrations were created. The Transitional National Government

The Transitional National Government (TNG) was the internationally recognized central government of Somalia from 2000 to 2004.

Overview

The TNG was established in April–May 2000 at the Somalia National Peace Conference held in Arta, Djibouti. I ...

(TNG) was established in 2000, followed by the formation of the Transitional Federal Government

The Transitional Federal Government (TFG) ( so, Dowladda Federaalka Kumeelgaarka, ar, الحكومة الاتحادية الانتقالية) was internationally recognized as a provisional government of the Somalia, Republic of Somalia from 14 ...

(TFG) in 2004, which reestablished the Somali Armed Forces

The Somali Armed Forces are the military forces of the Federal Republic of Somalia. Headed by the president as commander-in-chief, they are constitutionally mandated to ensure the nation's sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity. C ...

.

In 2006, with a US backed Ethiopian intervention, the TFG assumed control of most of the nation's southern conflict zones from the newly formed Islamic Courts Union

The Islamic Courts Union ( so, Midowga Maxkamadaha Islaamiga) was a legal and political organization formed to address the lawlessness that had been gripping Somalia since the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991 during the Somali Civil War.

Th ...

(ICU). The ICU subsequently splintered into more radical groups, such as Al-Shabaab, which battled the TFG and its AMISOM

The African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) was a regional peacekeeping mission operated by the African Union with the approval of the United Nations Security Council. It was mandated to support transitional governmental structures, implem ...

allies for control of the region. By mid-2012, the insurgents had lost most of the territory they had seized, and a search for more permanent democratic institutions began. Despite this, insurgents still control much of central and southern Somalia, and wield influence in government-controlled areas, with the town of Jilib

Jilib (other names: Gilib, Gelib, Jillib, Jillio; ) is a city in Somalia, It is north of Kismaayo.

History

During the Middle Ages, Jilib and its surrounding area was part of the Ajuran Empire that governed much of southern Somalia and eastern Eth ...

acting as the insurgents' de facto capital. A new provisional constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

was passed in August 2012, reforming Somalia as a federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-govern ...

. The same month, the Federal Government of Somalia

The Government of Somalia (GS) ( so, Dowladda Soomaaliya, ar, حكومة الصومال الاتحادية) is the internationally recognised government of Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, ا� ...

was formed and a period of reconstruction began in Mogadishu

Mogadishu (, also ; so, Muqdisho or ; ar, مقديشو ; it, Mogadiscio ), locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port connecting traders across the Indian Oc ...

.

Somalia has maintained an informal economy

An informal economy (informal sector or grey economy) is the part of any economy that is neither taxed nor monitored by any form of government.

Although the informal sector makes up a significant portion of the economies in developing countrie ...

mainly based on livestock, remittances from Somalis working abroad, and telecommunications. It is a member of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

, the Arab League, African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of member states of the African Union, 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling fo ...

, Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

, and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

An organization or organisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is an entity—such as a company, an institution, or an association—comprising one or more people and having a particular purpose.

The word is derived fr ...

.

History

Prehistory

Somalia was likely one of the first lands to be settled by early humans due to its location. Hunter-gatherers who would later migrate out of Africa likely settled here before their migrations. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished here. The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BCE. The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterized in 1909 as important artifacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.

According to linguists, the first

Somalia was likely one of the first lands to be settled by early humans due to its location. Hunter-gatherers who would later migrate out of Africa likely settled here before their migrations. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished here. The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BCE. The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterized in 1909 as important artifacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.

According to linguists, the first Afroasiatic

The Afroasiatic languages (or Afro-Asiatic), also known as Hamito-Semitic, or Semito-Hamitic, and sometimes also as Afrasian, Erythraean or Lisramic, are a language family of about 300 languages that are spoken predominantly in the geographic su ...

-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several part ...

period from the family's proposed urheimat

In historical linguistics, the homeland or ''Urheimat'' (, from German '' ur-'' "original" and ''Heimat'', home) of a proto-language is the region in which it was spoken before splitting into different daughter languages. A proto-language is the r ...

("original homeland") in the Nile Valley

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest ri ...

, or the Near East.

The Laas Geel

Laas Geel ( so, Laas Geel), also spelled Laas Gaal, are cave formations on the rural outskirts of Hargeisa, Somaliland, situated in the Maroodi Jeex region of the country. They contain some of the earliest known cave paintings of domesticated Af ...

complex on the outskirts of Hargeisa

Hargeisa (; so, Hargeysa, ar, هرجيسا) is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Somaliland. It is located in the Maroodi Jeex region of the Horn of Africa. It succeeded Burco as the capital of the British Somaliland Protecto ...

in northwestern Somalia dates back approximately 5,000 years, and has rock art depicting both wild animals and decorated cows. Other cave painting

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are more than 40,00 ...

s are found in the northern Dhambalin

Dhambalin ("half, vertically cut mountain") is an archaeological site in the central Sahil province of Somaliland. The sandstone rock shelter contains rock art depicting various animals such as horned cattle and goats, as well as giraffes, an ani ...

region, which feature one of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback. The rock art is dated to 1,000 to 3,000 BCE. Additionally, between the towns of Las Khorey

Las Khorey ( so, Laasqoray, ar, لاسقُرَى ) is a historic coastal town in the Sanaag region of Somaliland.

History

The Las Khorey settlement is several centuries old. Between the town and El Ayo lies Karinhegane, a site containing nu ...

and El Ayo

El Ayo ( so, Ceelaayo, ar, عيلايو), also known as El Ayum, is a coastal town in the eastern Sanaag region of Somaliland, near the border with Somalia. There is a base of the Puntland Maritime Police Force, which is effectively controll ...

in northern Somalia lies Karinhegane

Karinhegane is an archaeological site in the eastern Sanaag region of Somaliland. It contains some unique polychrome rock art.

Overview

Karinhegane is situated between the towns of Las Khorey and El Ayo. It is the site of numerous cave paintin ...

, the site of numerous cave paintings of both real and mythical animals. Each painting has an inscription below it, which collectively have been estimated to be around 2,500 years old.

Antiquity and classical era

Ancientpyramid

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrila ...

ical structures, mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be con ...

s, ruined cities and stone walls, such as the Wargaade Wall

Wargaade Wall is an ancient stone construction in Wargaade, Somalia. It enclosed a large historic settlement in the region.

Overview

Graves and unglazed sherds of pottery dating from antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historica ...

, are evidence of an old civilization that once thrived in the Somali peninsula. This civilization enjoyed a trading relationship with ancient Egypt and Mycenaean Greece since the second millennium BCE, supporting the hypothesis that Somalia or adjacent regions were the location of the ancient Land of Punt

The Land of Punt ( Egyptian: ''pwnt''; alternate Egyptological readings ''Pwene''(''t'') /pu:nt/) was an ancient kingdom known from Ancient Egyptian trade records. It produced and exported gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory ...

. The Puntites native to the region, traded myrrh

Myrrh (; from Semitic, but see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus '' Commiphora''. Myrrh resin has been used throughout history as a perfume, incense and medicine. Myrrh mix ...

, spices, gold, ebony, short-horned cattle, ivory and frankincense with the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Babylonians, Indians, Chinese and Romans through their commercial ports. An Egyptian expedition sent to Punt by the 18th dynasty Queen Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut (; also Hatchepsut; Egyptian: '' ḥꜣt- špswt'' "Foremost of Noble Ladies"; or Hatasu c. 1507–1458 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh, af ...

is recorded on the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari

Deir el-Bahari or Dayr al-Bahri ( ar, الدير البحري, al-Dayr al-Baḥrī, the Monastery of the North) is a complex of mortuary temples and tombs located on the west bank of the Nile, opposite the city of Luxor, Egypt. This is a part of ...

, during the reign of the Puntite King Parahu and Queen Ati. In 2015, isotopic analysis of ancient baboon mummies from Punt that had been brought to Egypt as gifts indicated that the specimens likely originated from an area encompassing eastern Somalia and the Eritrea-Ethiopia corridor.

In the classical era

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, the Macrobians

The Macrobians (Μακροβίοι) were an ancient Proto-Somali tribal kingdom positioned in the Horn of Africa mentioned by Herodotus.Herodotus, the Histories book 3.114 They are one of the legendary peoples postulated at the extremity of the ...

, who may have been ancestral to Somalis, established a powerful tribal kingdom that ruled large parts of modern Somalia. They were reputed for their longevity and wealth, and were said to be the "tallest and handsomest of all men".The Geography of Herodotus: Illustrated from Modern Researches and Discoveriesby James Talboys Wheeler, pg 1xvi, 315, 526 The Macrobians were warrior herders and seafarers. According to Herodotus' account, the

Persian Emperor

This is a list of monarchs of Persia (or monarchs of the Iranian peoples, Iranic peoples, in present-day Iran), which are known by the royal title Shah or King of Kings#Iran, Shahanshah. This list starts from the establishment of the Medes aroun ...

Cambyses II

Cambyses II ( peo, 𐎣𐎲𐎢𐎪𐎡𐎹 ''Kabūjiya'') was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 530 to 522 BC. He was the son and successor of Cyrus the Great () and his mother was Cassandane.

Before his accession, Cambyse ...

, upon his conquest of Egypt in 525 BC, sent ambassadors to Macrobia, bringing luxury gifts for the Macrobian king to entice his submission. The Macrobian ruler, who was elected based on his stature and beauty, replied instead with a challenge for his Persian counterpart in the form of an unstrung bow: if the Persians could manage to draw it, they would have the right to invade his country; but until then, they should thank the gods that the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire.John Kitto, James Taylor, ''The popular cyclopædia of Biblical literature: condensed from the larger work'', (Gould and Lincoln: 1856), p.302. The Macrobians were a regional power reputed for their advanced architecture and gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

wealth, which was so plentiful that they shackled their prisoners in golden chains. The camel

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. ...

is believed to have been domesticated in the Horn region sometime between the 2nd and 3rd millennium BCE. From there, it spread to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

and the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

.

During the classical period, the Barbara

Barbara may refer to:

People

* Barbara (given name)

* Barbara (painter) (1915–2002), pseudonym of Olga Biglieri, Italian futurist painter

* Barbara (singer) (1930–1997), French singer

* Barbara Popović (born 2000), also known mononymously as ...

city-states also known as sesea

The Monumentum Adulitanum was an ancient bilingual inscription in Ge'ez and Greek depicting the military campaigns of an Adulite king. The original text was inscribed on a throne in Adulis ( Ge'ez: መንበር ''manbar'') written in Ge'ez in b ...

of Mosylon

Mosylon ( grc, Μοσυλλόν and Μόσυλον), also known as Mosullon, was an ancient proto-Somali trading center on or near the site that later became the city of Bosaso.

History

Mosylon was the most prominent emporium on the Red Sea coast ...

, Opone

Opone ( grc, Οπώνη) was an ancient proto-Somali city situated in the Horn of Africa. It is primarily known for its trade with the Ancient Egyptians, Romans, Greeks, Persians, and the states of ancient India. Through archaeological remains, ...

, Mundus, Isis

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic language, Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician language, Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major ancient Egyptian deities, goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughou ...

, Malao

Malao ( grc, Μαλαὼ) was an ancient proto-Somali port in present-day Somaliland. The town was situated on the site of what later became the city of Berbera. It was a key trading member involved in the Red Sea-Indian Ocean commerce in the ea ...

, Avalites

Avalites ( grc, Αὐαλίτης or ) was a small port in what is today Somalia that dominated trade in the Red Sea and Mediterranean.

Location

There has been a series of disputes as to the location of Avalites According to the ''Periplus of th ...

, Essina

Essina ( grc, Εσσίνα) was an ancient Proto-Somali emporium located on the southeastern coast of Somalia in the Horn of Africa.Ptolemy's Topography of Eastern Equatorial Africa, by Henry Schlichter Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Societ ...

, Nikon

(, ; ), also known just as Nikon, is a Japanese multinational corporation headquartered in Tokyo, Japan, specializing in optics and imaging products. The companies held by Nikon form the Nikon Group.

Nikon's products include cameras, camera ...

and Sarapion

Sarapion ( grc, Σαράπιον, also spelled Serapion) was an ancient proto-Somali port city in present-day Somalia. It was situated on a site that later became Mogadishu. Sarapion was briefly mentioned in Ptolemy's ''Geographia'' as one of the ...

developed a lucrative trade network, connecting with merchants from Ptolemaic Egypt, Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

, Parthian Persia, Saba Saba may refer to:

Places

* Saba (island), an island of the Netherlands located in the Caribbean Sea

* Şaba (Romanian for Shabo), a town of the Odesa Oblast, Ukraine

* Sabá, a municipality in the department of Colón, Honduras

* Saba (river) ...

, the Nabataean Kingdom

The Nabataean Kingdom ( Nabataean Aramaic: 𐢕𐢃𐢋𐢈 ''Nabāṭū''), also named Nabatea (), was a political state of the Arab Nabataeans during classical antiquity.

The Nabataean Kingdom controlled many of the trade routes of the region, ...

, and the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

. They used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the ''beden

The Beden, badan, or alternate type names Beden-seyed and Beden-safar, is a fast, ancient Somali single or double-masted maritime vessel and ship, typified by its towering stern-post and powerful rudder. It is also the longest surviving sewn bo ...

'' to transport their cargo.

After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab and Somali merchants agreed with the Romans to bar Indian ships from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula to protect the interests of Somali and Arab merchants in the lucrative commerce between the Red and Mediterranean Seas.. However, Indian merchants continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from Roman interference. For centuries, Indian merchants brought large quantities of cinnamon to Somalia and Arabia from

After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab and Somali merchants agreed with the Romans to bar Indian ships from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula to protect the interests of Somali and Arab merchants in the lucrative commerce between the Red and Mediterranean Seas.. However, Indian merchants continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from Roman interference. For centuries, Indian merchants brought large quantities of cinnamon to Somalia and Arabia from Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and the Spice Islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices a ...

. The source of the cinnamon and other spices is said to have been the best-kept secret of Arab and Somali merchants in their trade with the Roman and Greek world; the Romans and Greeks believed the source to have been the Somali peninsula. The collusive agreement among Somali and Arab traders inflated the price of Indian and Chinese cinnamon in North Africa, the Near East, and Europe, and made the cinnamon trade a very profitable revenue generator, especially for the Somali merchants through whose hands large quantities were shipped across sea and land routes.

Birth of Islam and the Middle Ages

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of Mecca fleeing prosecution during the first

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of Mecca fleeing prosecution during the first Hejira

The Hijrah or Hijra () was the journey of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina. The year in which the Hijrah took place is also identified as the epoch of the Lunar Hijri and Solar Hijri calendars; its dat ...

with Masjid al-Qiblatayn

The Masjid al-Qiblatayn ( ar, مسجد القبلتين, lit=Mosque of the Two Qiblas), also spelt Masjid al-Qiblatain, is a mosque in Medina believed by Muslims to be the place where the final Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet, ...

in Zeila

Zeila ( so, Saylac, ar, زيلع, Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila (or Hawilah) with the Bib ...

being built before the Qibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the s ...

h towards Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow val ...

. It is one of the oldest mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a Place of worship, place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers (sujud) ...

s in Africa. In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi

ʾAbū l-ʿAbbās ʾAḥmad bin ʾAbī Yaʿqūb bin Ǧaʿfar bin Wahb bin Waḍīḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (died 897/8), commonly referred to simply by his nisba al-Yaʿqūbī, was an Arab Muslim geographer and perhaps the first historian of world cult ...

wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Somali seaboard. He also mentioned that the Adal Kingdom

The Adal Sultanate, or the Adal Empire or the ʿAdal or the Bar Saʿad dīn (alt. spelling ''Adel Sultanate, ''Adal ''Sultanate'') () was a medieval Sunni Muslim Empire which was located in the Horn of Africa. It was founded by Sabr ad-Din ...

had its capital in the city. According to Leo Africanus

Joannes Leo Africanus (born al-Hasan Muhammad al-Wazzan, ar, الحسن محمد الوزان ; c. 1494 – c. 1554) was an Andalusian diplomat and author who is best known for his 1526 book ''Cosmographia et geographia de Affrica'', later ...

, the Adal Sultanate

The Adal Sultanate, or the Adal Empire or the ʿAdal or the Bar Saʿad dīn (alt. spelling ''Adel Sultanate, ''Adal ''Sultanate'') () was a medieval Sunni Muslim Empire which was located in the Horn of Africa. It was founded by Sabr ad-Din ...

was governed by local Somali

Somali may refer to:

Horn of Africa

* Somalis, an inhabitant or ethnicity associated with Greater Somali Region

** Proto-Somali, the ancestors of modern Somalis

** Somali culture

** Somali cuisine

** Somali language, a Cushitic language

** Soma ...

dynasties and its realm encompassed the geographical area between the Bab el Mandeb and Cape Guardafui. It was thus flanked to the south by the Ajuran Empire

The Ajuran Sultanate ( so, Saldanadda Ajuuraan, ar, سلطنة الأجورانية), also natively referred-to as Ajuuraan, and often simply Ajuran, was a Somali Empire in the Middle Ages in the Horn of Africa that dominated the trade in th ...

and to the west by the Abyssinian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historical ...

.

Throughout the Middle Ages, Arab immigrants arrived in Somaliland, a historical experience which would later lead to the legendary stories about Muslim sheikhs such as Daarood

The Darod ( so, Daarood, ar, دارود) is a Somali clan. The forefather of this clan was Sheikh Abdirahman bin Isma'il al-Jabarti, more commonly known as ''Darood''. The clan primarily settles the apex of the Horn of Africa and its peripherie ...

and Ishaaq bin Ahmed

Sheikh Ishaaq bin Ahmed bin Muhammad bin al-Hussein al-Hashimi, more commonly known as Sheikh Ishaaq or Sheikh Isaaq (, ) was the semi-legendary Arab forefather of the Somali Isaaq clan-family in the Horn of Africa, whose traditional territory i ...

(the purported ancestors of the Darod

The Darod ( so, Daarood, ar, دارود) is a Somali clan. The forefather of this clan was Sheikh Abdirahman bin Isma'il al-Jabarti, more commonly known as ''Darood''. The clan primarily settles the apex of the Horn of Africa and its peripherie ...

and Isaaq

The Isaaq (also Isaq, Ishaak, Isaac) ( so, Reer Sheekh Isxaaq, ar, بني إسحاق, Banī Isḥāq) is a Somali clan. It is one of the major Somali clans in the Horn of Africa, with a large and densely populated traditional territory. Pe ...

clans, respectively) travelling from Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

to Somalia and marrying into the local Dir clan.

In 1332, the Zeila-based King of Adal was slain in a military campaign aimed at halting Abyssinian emperor Amda Seyon I

Amda Seyon I ( gez, ዐምደ ፡ ጽዮን , am, አምደ ፅዮን , "Pillar of Zion"), throne name Gebre Mesqel (ገብረ መስቀል ) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1314 to 1344 and a member of the Solomonic dynasty.

He is best known i ...

's march toward the city. When the last Sultan of Ifat, Sa'ad ad-Din II

Sa'ad ad-Din II ( ar, سعد الدين زنكي), reigned – c. 1403 or c. 1414, was a Sultan of the Ifat Sultanate. He was the brother of Haqq ad-Din II, and the father of Mansur ad-Din, Sabr ad-Din II and Badlay ibn Sa'ad ad-Din. The histo ...

, was also killed by Emperor Dawit I

Dawit I ( gez, ዳዊት) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1382 to 6 October 1413, and a member of the Solomonic dynasty. He was the younger son of Newaya Krestos.

Reign

Taddesse Tamrat discusses a tradition that early in his reign, Dawit campaigne ...

in Zeila in 1410, his children escaped to Yemen, before returning in 1415. In the early 15th century, Adal's capital was moved further inland to the town of Dakkar, where Sabr ad-Din II

Sabr ad-Din III ( ar, الصبر الدين الثاني) (died 1422 or 1423) was a Sultan of Adal and the oldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II. Sabr ad-Din returned to the Horn of Africa from Yemen to reclaim his father's realm. He defeated the Ethiopi ...

, the eldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II, established a new base after his return from Yemen.

Adal's headquarters were again relocated the following century, this time southward to

Adal's headquarters were again relocated the following century, this time southward to Harar

Harar ( amh, ሐረር; Harari: ሀረር; om, Adare Biyyo; so, Herer; ar, هرر) known historically by the indigenous as Gey (Harari: ጌይ ''Gēy'', ) is a walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is also known in Arabic as the City of Sain ...

. From this new capital, Adal organised an effective army led by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi

Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi ( so, Axmed Ibraahim al-Qaasi or Axmed Gurey, Harari: አሕመድ ኢብራሂም አል-ጋዚ, ar, أحمد بن إبراهيم الغازي ; 1506 – 21 February 1543) was an imam and general of the Adal Sultana ...

(Ahmad "Gurey" or "Gran"; both meaning "the left-handed") that invaded the Abyssinian empire. This 16th-century campaign is historically known as the Conquest of Abyssinia (''Futuh al-Habash''). During the war, Imam Ahmad pioneered the use of cannons supplied by the Ottoman Empire, which he imported through Zeila and deployed against Abyssinian forces and their Portuguese allies led by Cristóvão da Gama

Cristóvão da Gama ( 1516 – 29 August 1542), anglicised as Christopher da Gama, was a Portuguese military commander who led a Portuguese army of 400 musketeers on a crusade in Ethiopia (1541–1543) against the Adal Muslim army of Imam Ahma ...

. Some scholars argue that this conflict proved, through their use on both sides, the value of firearms such as the matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of rope that is touched to the gunpowder by a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or trigger with his finger. Befo ...

musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket graduall ...

, cannon, and the arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbu ...

over traditional weapons.

During the Ajuran Sultanate

The Ajuran Sultanate ( so, Saldanadda Ajuuraan, ar, سلطنة الأجورانية), also natively referred-to as Ajuuraan, and often simply Ajuran, was a Somali Empire in the Middle Ages in the Horn of Africa that dominated the trade in th ...

period, the sultanates and republics of Merca

Merca ( so, Marka, Maay: ''Marky'', ar, مركة) is a historic port city in the southern Lower Shebelle province of Somalia. It is located approximately to the southwest of the nation's capital Mogadishu. Merca is the traditional home territory ...

, Mogadishu

Mogadishu (, also ; so, Muqdisho or ; ar, مقديشو ; it, Mogadiscio ), locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port connecting traders across the Indian Oc ...

, Barawa

Barawa ( so, Baraawe, Maay: ''Barawy'', ar, ﺑﺮﺍﻭة ''Barāwa''), also known as Barawe and Brava, is the capital of the South West State of Somalia.Pelizzari, Elisa. "Guerre civile et question de genre en Somalie. Les événements et le ...

, Hobyo

Hobyo (; so, Hobyo), is an ancient port city in Galmudug state in the north-central Mudug region of Somalia.

Hobyo was founded as a coastal outpost by the Ajuran Empire during the 13th century.Lee V. Cassanelli, ''The shaping of Somali society: ...

and their respective ports flourished and had a lucrative foreign commerce, with ships sailing to and coming from Arabia, India, Venetia, Persia, Egypt, Portugal, and as far away as China. Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (; ; c. 1460s – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.

His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses several storeys high and large palaces in its centre, in addition to many mosques with cylindrical minarets. The Harla

The Harla, also known as Harala, or Arla, are an extinct ethnic group that once inhabited Djibouti, Ethiopia and northern Somalia. They spoke the now-extinct Harla language, which belonged to either the Cushitic or Semitic branches of the Afroas ...

, an early Hamitic

Hamites is the name formerly used for some Northern and Horn of Africa peoples in the context of a now-outdated model of dividing humanity into different races which was developed originally by Europeans in support of colonialism and slavery. ...

group of tall stature who inhabited parts of Somalia, Tchertcher and other areas in the Horn, also erected various tumuli

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or '' kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones b ...

. These masons are believed to have been ancestral to ethnic Somalis.

In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa

Duarte Barbosa (c. 14801 May 1521) was a Portuguese writer and officer from Portuguese India (between 1500 and 1516). He was a Christian pastor and scrivener in a ''feitoria'' in Kochi, and an interpreter of the local language, Malayalam. Barbo ...

noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya in modern-day India sailed to Mogadishu with cloth and spices, for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants. Mogadishu, the center of a thriving textile industry known as ''toob benadir'' (specialized for the markets in Egypt, among other places), together with Merca and Barawa, also served as a transit stop for Swahili

Swahili may refer to:

* Swahili language, a Bantu language official in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda and widely spoken in the African Great Lakes

* Swahili people, an ethnic group in East Africa

* Swahili culture

Swahili culture is the culture of ...

merchants from Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of the British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital city status. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

and Malindi

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban cen ...

and for the gold trade from Kilwa

Kilwa Kisiwani (English: ''Kilwa Island'') is an island, national historic site, and hamlet community located in the township of Kilwa Masoko, the district seat of Kilwa District in the Tanzanian region of Lindi Region in southern Tanzania. K ...

. Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

merchants from the Hormuz brought their Indian textile and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit ( caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legu ...

and wood.

Trading relations were established with Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site s ...

in the 15th century, with cloth, ambergris and porcelain being the main commodities of the trade. Giraffes, zebras and incense were exported to the Ming Empire

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peop ...

of China, which established Somali merchants as leaders in the commerce between East Asia and the Horn. Hindu merchants from Surat

Surat is a city in the western Indian state of Gujarat. The word Surat literally means ''face'' in Gujarati and Hindi. Located on the banks of the river Tapti near its confluence with the Arabian Sea, it used to be a large seaport. It is no ...

and Southeast African merchants from Pate

Pate, pâté, or paté may refer to:

Foods Pâté 'pastry'

* Pâté, various French meat forcemeat pies or loaves

* Pâté haïtien or Haitian patty, a meat-filled puff pastry dish

* ''Pate'' or ''paté'' (anglicized spellings), the Virgin Isla ...

, seeking to bypass both the Portuguese India

The State of India ( pt, Estado da Índia), also referred as the Portuguese State of India (''Estado Português da Índia'', EPI) or simply Portuguese India (), was a state of the Portuguese Empire founded six years after the discovery of a s ...

blockade ( and later the Omani interference), used the Somali ports of Merca and Barawa (which were out of the two powers' direct jurisdiction) to conduct their trade in safety and without interference.

Early modern era and the scramble for Africa

In the early modern period, successor states to the Adal Sultanate and Ajuran Sultanate began to flourish in Somalia. These included theHiraab Imamate

The Hiraab Imamate ( so, Saldanadda Hiraab) also known as the Yacquubi Dynasty was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the late 17th century and 19th century until it was incorporated into Italian Somaliland. The Imamat ...

, the Sultanate of the Geledi

The Sultanate of the Geledi ( so, Saldanadda Geledi, ar, سلطنة غلدي) also known as the Gobroon Dynasty Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years - Virginia Luling (2002) Page 229 was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of th ...

(Gobroon dynasty), the Majeerteen Sultanate

The Majeerteen Sultanate ( so, Suldanadda Majeerteen 𐒈𐒚𐒐𐒆𐒖𐒒𐒖𐒆𐒆𐒖 𐒑𐒖𐒃𐒜𐒇𐒂𐒜𐒒, lit=Boqortooyada Majerteen, ar, سلطنة مجرتين), also known as Majeerteen Kingdom or Majeerteenia and Migiu ...

(Migiurtinia), and the Sultanate of Hobyo

The Sultanate of Hobyo ( so, Saldanadda Hobyo, ar, سلطنة هوبيو), also known as the Sultanate of Obbia,''New International Encyclopedia'', Volume 21, (Dodd, Mead: 1916), p.283. was a 19th-century Somali kingdom in present-day northeaste ...

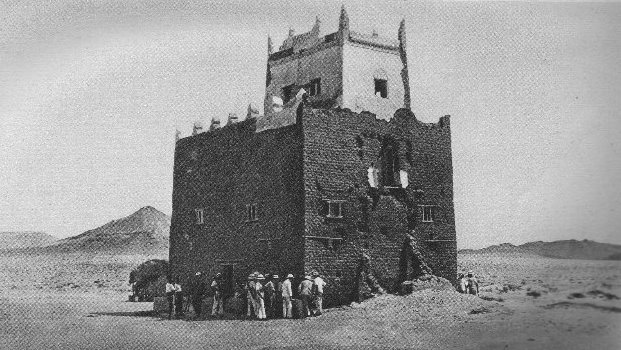

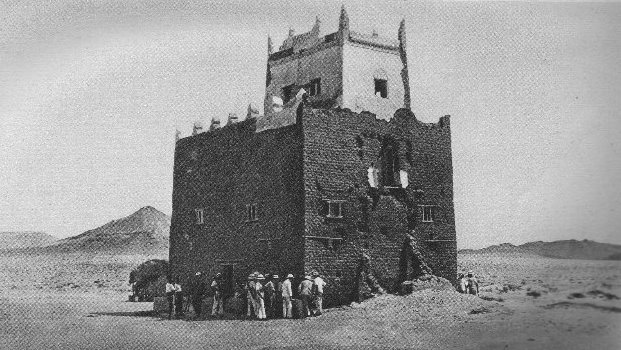

(Obbia). They continued the tradition of castle-building and seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires.

Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim

Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim ( so, Yuusuf Maxamuud Ibrahiim, ar, يوسف محمود ابراهيم) was a Somali ruler. He was the third and most powerful Sultan of the Geledi sultanate, reigning from 1798 to 1848. Under the reign of Sultan Yusuf, his ...

, the third Sultan of the House of Gobroon, started the golden age of the Gobroon Dynasty. His army came out victorious during the Bardheere Jihad, which restored stability in the region and revitalized the East African ivory trade

The ivory trade is the commercial, often illegal trade in the ivory tusks of the hippopotamus, walrus, narwhal, mammoth, and most commonly, African and Asian elephants.

Ivory has been traded for hundreds of years by people in Africa and ...

. He also received presents from and had cordial relations with the rulers of neighbouring and distant kingdoms such as the Omani, Witu and Yemeni Sultans.

Sultan Ibrahim's son Ahmed Yusuf succeeded him and was one of the most important figures in 19th-century East Africa, receiving tribute from Omani governors and creating alliances with important Muslim families on the East African coast. In Somalland, the Isaaq Sultanate

The Isaaq Sultanate ( so, Saldanadda Isaaq, Wadaad: , ar, السلطنة الإسحاقية) was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries. It spanned the territories of the Isaaq clan in modern- ...

was established in 1750. The Isaaq Sultanate was a Somali

Somali may refer to:

Horn of Africa

* Somalis, an inhabitant or ethnicity associated with Greater Somali Region

** Proto-Somali, the ancestors of modern Somalis

** Somali culture

** Somali cuisine

** Somali language, a Cushitic language

** Soma ...

kingdom that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

during the 18th and 19th centuries. It spanned the territories of the Isaaq

The Isaaq (also Isaq, Ishaak, Isaac) ( so, Reer Sheekh Isxaaq, ar, بني إسحاق, Banī Isḥāq) is a Somali clan. It is one of the major Somali clans in the Horn of Africa, with a large and densely populated traditional territory. Pe ...

clan, descendants of the Banu Hashim

)

, type = Qurayshi Arab clan

, image =

, alt =

, caption =

, nisba = al-Hashimi

, location = Mecca, Hejaz Middle East, North Africa, Horn of Africa

, descended = Hashim ibn Abd Manaf

, parent_tribe = Qur ...

clan,I. M. Lewis, ''A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa'', (LIT Verlag Münster: 1999), p. 157. in modern-day Somaliland and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the Er ...

. The sultanate was governed by the Rer Guled branch established by the first sultan, Sultan Guled Abdi

''TallBoyz'' is a Canadian television sketch comedy troupe best known for their 2019-2022 CBC Television sketch comedy series.

The series stars Guled Abdi, Vance Banzo, Tim Blair and Franco Nguyen, who have worked for several years in stage-based ...

, of the Eidagale

The Eidagale (Ciidagale), ar, عيدَغَلي, (which translates to "army joiner"), Full Name: Da'ud ibn Al-Qādhī Ismā'īl ibn ash-Shaykh Isḥāq ibn Aḥmad, is a major Somali clan and is a sub-division of the Garhajis clan of the Isaa ...

clan. The sultanate is the pre-colonial predecessor to the modern Republic of Somaliland

Somaliland,; ar, صوماليلاند ', ' officially the Republic of Somaliland,, ar, جمهورية صوماليلاند, link=no ''Jumhūrīyat Ṣūmālīlānd'' is a ''List of states with limited recognition, de facto'' sovereign s ...

.

According to oral tradition, prior to the Guled dynasty the Isaaq

The Isaaq (also Isaq, Ishaak, Isaac) ( so, Reer Sheekh Isxaaq, ar, بني إسحاق, Banī Isḥāq) is a Somali clan. It is one of the major Somali clans in the Horn of Africa, with a large and densely populated traditional territory. Pe ...

clan-family were ruled by a dynasty of the Tolje'lo branch starting from, descendants of Ahmed nicknamed Tol Je'lo, the eldest son of Sheikh Ishaaq's Harari wife. There were eight Tolje'lo rulers in total, starting with Boqor Harun () who ruled the Isaaq Sultanate for centuries starting from the 13th century. The last Tolje'lo ruler Garad

Garad ( Harari: ገራድ, , , Oromo: ''Garaada'') is a term used to refer to a clan leader or regional administrator. It was used primarily by Muslims in the Horn of Africa that were associated with Islamic states, most notably the Adal Sultanate ...

Dhuh Barar ( so, Dhuux Baraar) was overthrown by a coalition of Isaaq clans. The once strong Tolje'lo clan were scattered and took refuge amongst the Habr Awal

The Habr Awal, also contemporarily known as the Subeer Awal, and alternately romanized as the Zubeyr Awal ( so, Habar Awal, ar, هبر أول, Full Name: '' Zubeyr ibn Abd al-Raḥmān ibn ash- Shaykh Isḥāq ibn Aḥmad)'' is a major clan of ...

with whom they still mostly live.

In the late 19th century, after the

In the late 19th century, after the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergen ...

of 1884, European powers began the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during a short period known as New Imperialism ( ...

. In that year, a British protectorate was declared over part of Somalia, on the African coast opposite South Yemen.Langers Encyclopedia of World History, 594. Initially, this region was under the control of the Indian Office, and so administered as part of the Indian Empire; in 1898 it was transferred to control by London. In the 1880s, the protectorate and later colony of Italian Somalia

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centur ...

was established by Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

through various treaties; Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid

Yusuf Ali Kenadid ( so, Yuusuf Cali Keenadiid; 1837 - 14 August 1911) was a Somali Sultan. He was the founder of the Sultanate of Hobyo in April 1878. He was succeeded atop the throne by his son Ali Yusuf Kenadid.

Family

Yusuf Ali Kenadid was b ...

entered into a treaty with Italy in late 1888, making his Sultanate of Hobyo

The Sultanate of Hobyo ( so, Saldanadda Hobyo, ar, سلطنة هوبيو), also known as the Sultanate of Obbia,''New International Encyclopedia'', Volume 21, (Dodd, Mead: 1916), p.283. was a 19th-century Somali kingdom in present-day northeaste ...

an Italian protectorate.

The Dervish movement successfully repulsed the British Empire four times and forced it to retreat to the coastal region. The Darawiish defeated the Italian, British, Abyssinian colonial powers on numerous occasions, most notably, the 1903 victory at Cagaarweyne commanded by Suleiman Aden Galaydh Suleiman Aden Galaydh was the Darawiish military commander in the year 1903, when the Gumburu (Gumburka Cagaarweyne) and Daratoleh battles occurred. According to British sources, the number of military personnel he commanded stood at 2200, the high ...

, forcing the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

to retreat to the coastal region in the late 1900s. The Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920 by British airpower.

The dawn of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and th ...

in the early 1920s heralded a change of strategy for Italy, as the north-eastern sultanates were soon to be forced within the boundaries of ''La Grande Somalia'' ("''Greater Somalia

Greater Somalia ( so, Soomaaliweyn, ar, الصومال الكبرى ''As-Sūmal al-Kubra'') is a concept to unite all ethnic Somalis comprising the regions in or near the Horn of Africa in which ethnic Somalis live and have historically inhabited ...

''") according to the plan of Fascist Italy. With the arrival of Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi

Cesare Maria De Vecchi, 1st Conte di Val Cismon (14 November 1884 – 23 June 1959) was an Italian soldier, colonial administrator and Fascist politician.

Biography

De Vecchi was born in Casale Monferrato on 14 November 1884. After graduating ...

on 15 December 1923, things began to change for that part of Somaliland known as Italian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th cent ...

. The last piece of land acquired by Italy in Somalia was Oltre Giuba

Oltre Giuba or Trans-Juba ( ar, شرق جوبا الإيطالية) was an Italian colony in the territory of Jubaland in present-day southern Somalia. It lasted for one year, from 1924 until 1925, when it was absorbed into Italian Somaliland. '' ...

, present-day Jubaland

Jubaland ( so, Jubbaland, ar, , it, Oltregiuba), the Juba Valley ( so, Dooxada Jubba) or Azania ( so, Asaaniya, ar, ), is a Federal Member State in southern Somalia. Its eastern border lies east of the Jubba River, stretching from Gedo ...

region, in 1925.

The Italians began local infrastructure projects, including the construction of hospitals, farms and schools. Fascist Italy

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

, under Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

, attacked Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935, with an aim to colonize it. The invasion was condemned by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

, but little was done to stop it or to liberate occupied Ethiopia. In 1936, Italian Somalia was integrated into Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa ( it, Africa Orientale Italiana, AOI) was an Italian colony in the Horn of Africa. It was formed in 1936 through the merger of Italian Somalia, Italian Eritrea, and the newly occupied Ethiopian Empire, conquered in the Se ...

, alongside Eritrea and Ethiopia, as the Somalia Governorate

Somalia Governorate was one of the governorates of Italian East Africa, six governorates of Italian East Africa. It was formed from the previously separate colony of Italian Somalia, enlarged by the Ogaden region of the conquered Ethiopian Empire f ...

. On 3 August 1940, Italian troops, including Somali colonial units, crossed from Ethiopia to invade British Somaliland, and by 14 August, succeeded in taking Berbera

Berbera (; so, Barbara, ar, بربرة) is the capital of the Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of the British Somaliland protectorate before Hargeisa. It ...

from the British.

A British force, including troops from several African countries, launched the campaign in January 1941 from Kenya to liberate British Somaliland and Italian-occupied Ethiopia and conquer Italian Somaliland. By February most of Italian Somaliland was captured and, in March, British Somaliland was retaken from the sea. The forces of the British Empire operating in Somaliland comprised the three divisions of South African, West African, and East African troops. They were assisted by Somali forces led by Abdulahi Hassan with Somalis of the Isaaq

The Isaaq (also Isaq, Ishaak, Isaac) ( so, Reer Sheekh Isxaaq, ar, بني إسحاق, Banī Isḥāq) is a Somali clan. It is one of the major Somali clans in the Horn of Africa, with a large and densely populated traditional territory. Pe ...

, Dhulbahante

The Dhulbahante ( so, Dhulbahante, ar, دلبةنتئ) is a Somali clan family, part of the Harti clan which itself belongs to the largest Somali clan-family — the Darod. They are the traditional inhabitants of the physiographic Nugaal in i ...

, and Warsangali

The Warsangali ( so, Warsangeli, ar, قبيلة ورسنجلي) is a major Somali sub clan, part of the Harti clan which itself belongs to one of the largest Somali clan-families - the Darod. In the Somali language, the name Warsangali means ...

clans prominently participating. The number of Italian Somalis

Italian Somalis ( it, Italo-Somali) are Somali descendants from Italian colonists, as well as long-term Italian residents in Somalia.

History

In 1892, the Italian explorer Luigi Robecchi Bricchetti for the first time labeled as ''Somalia'' ...

began to decline after World War II, with fewer than 10,000 remaining in 1960.

Independence (1960–1969)

Following World War II, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland as protectorates. In 1945, during the

Following World War II, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland as protectorates. In 1945, during the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

, the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somaliland as the Trust Territory of Somaliland

The Trust Territory of Somaliland, officially the "Trust Territory of Somaliland under Italian administration" ( it, Amministrazione fiduciaria italiana della Somalia), was a United Nations Trust Territory situated in present-day Somalia. Its c ...

, on the condition first proposed by the Somali Youth League (SYL) and other nascent Somali political organizations, such as Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (HDMS) and the Somali National League (SNL)—that Somalia achieve independence within ten years. British Somaliland remained a protectorate of Britain until 1960.

To the extent that Italy held the territory by UN mandate, the trusteeship provisions gave the Somalis the opportunity to gain experience in Western political education and self-government. These were advantages that British Somaliland, which was to be incorporated into the new Somali state, did not have. Although in the 1950s British colonial officials attempted, through various administrative development efforts, to make up for past neglect, the protectorate stagnated in political administrative development. The disparity between the two territories in economic development and political experience would later cause serious difficulties integrating the two parts.

Meanwhile, in 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis, the British returned the Haud

The Haud (also Hawd) (, ), formerly known as the Hawd Reserve Area is a plateau situated in the Horn of Africa consisting of thorn-bush and grasslands. The region includes the southern part of Somaliland as well as the northern and eastern parts ...