Sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

as a scholarly discipline emerged, primarily out of

Enlightenment thought, as a

positivist ''

science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

of

society

A society () is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. ...

'' shortly after the

French Revolution. Its genesis owed to various key movements in the

philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is the branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. Amongst its central questions are the difference between science and non-science, the reliability of scientific theories, ...

and the

philosophy of knowledge

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowledg ...

, arising in reaction to such issues as

modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular Society, socio-Culture, cultural Norm (social), norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the ...

,

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

,

urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation in British English) is the population shift from Rural area, rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. ...

,

rationalization,

secularization

In sociology, secularization () is a multilayered concept that generally denotes "a transition from a religious to a more worldly level." There are many types of secularization and most do not lead to atheism or irreligion, nor are they automatica ...

,

colonization

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

and

imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

.

[Harriss, John. 2000. "The Second Great Transformation? Capitalism at the End of the Twentieth Century." In ''Poverty and Development in the 21st Century'', edited by T. Allen and A. Thomas. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 325.]

During its nascent stages, within the late 19th century, sociological deliberations took particular interest in the emergence of the modern

nation state

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the State (polity), state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly ...

, including its constituent

institution

An institution is a humanly devised structure of rules and norms that shape and constrain social behavior. All definitions of institutions generally entail that there is a level of persistence and continuity. Laws, rules, social conventions and ...

s, units of

socialization

In sociology, socialization (also socialisation – see American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), spelling differences) is the process of Internalisation (sociology), internalizing the Norm (social), norm ...

, and its means of

surveillance

Surveillance is the monitoring of behavior, many activities, or information for the purpose of information gathering, influencing, managing, or directing. This can include observation from a distance by means of electronic equipment, such as ...

. As such, an emphasis on the concept of modernity, rather than

the Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

, often distinguishes sociological discourse from that of classical

political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

.

Likewise, social analysis in a broader sense has origins in the common stock of philosophy, therefore pre-dating the sociological field.

Various quantitative

social research

Social research is research conducted by social scientists following a systematic plan. Social research methodologies can be classified as quantitative and qualitative.

* Quantitative designs approach social phenomena through quantifiable ...

techniques have become common tools for governments, businesses, and organizations, and have also found use in the other social sciences. Divorced from theoretical explanations of social dynamics, this has given

social research

Social research is research conducted by social scientists following a systematic plan. Social research methodologies can be classified as quantitative and qualitative.

* Quantitative designs approach social phenomena through quantifiable ...

a degree of autonomy from the discipline of sociology. Similarly, ''"

social science

Social science (often rendered in the plural as the social sciences) is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among members within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the ...

"'' has come to be appropriated as an umbrella term to refer to various disciplines which study humans, interaction, society or culture.

As a

discipline

Discipline is the self-control that is gained by requiring that rules or orders be obeyed, and the ability to keep working at something that is difficult. Disciplinarians believe that such self-control is of the utmost importance and enforce a ...

, sociology encompasses a varying scope of conception based on each sociologist's understanding of the

nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

and scope of society and its constituents. Creating a merely linear definition of its science would be improper in rationalizing the aims and efforts of sociological study from different academic backgrounds.

Antecedent history

Scope of being "sociological"

The codification of sociology as a word, concept, and popular terminology is identified with

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès (3 May 174820 June 1836), usually known as the Abbé Sieyès (; ), was a French Catholic priest, ''abbé'', and political writer who was a leading political theorist of the French Revolution (1789–1799); he also held off ...

(see 18th century section) and succeeding figures from that point onward. It is important to be mindful of

presentism, of introducing ideas of the present into the past, around sociology. Below, we see figures that developed strong methods and critiques that reflect on what we know sociology to be today that situates them as important figures in knowledge development around sociology. However, the term of "sociology" did not exist in this period, requiring careful language to incorporate these earlier efforts into the wider history of sociology. A more apt term to use might be

proto-sociology that outlines that the rough ingredients of sociology were present, but had no defined shape or label to understand them as sociology as we concepualize it today.

Ancient Greeks

The sociological reasoning may be traced back at least as far as the

ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically re ...

,

[ ]Xenophanes

Xenophanes of Colophon ( ; ; – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and critic of Homer. He was born in Ionia and travelled throughout the Greek-speaking world in early classical antiquity.

As a poet, Xenophanes was known f ...

′ remark: "''if horses would adore gods, these gods would resemble horses''." whose characteristic trends in sociological thought can be traced back to their social environment. Given the rarity of extensive or highly-centralized political organization within states, the tribal spirit of localism and provincialism was in for deliberations on social phenomena, which would thus pervade much of Greek thought.

Proto-sociological observations can be seen in the founding texts of Western philosophy (e.g.

Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

,

Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

,

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

,

Polybius

Polybius (; , ; ) was a Greek historian of the middle Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , a universal history documenting the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean in the third and second centuries BC. It covered the period of 264–146 ...

, etc.). Similarly, the methodological

survey can trace its origins back to the

Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

ordered by King of England,

William the Conqueror

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was D ...

, in 1086.

13th century: studying social patterns

East Asia

Sociological perspectives can also be found among non-European thought of figures such as

Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

.

In the 13th century,

Ma Duanlin, a Chinese historian, first recognized patterns of ''

social dynamics

Social dynamics (or sociodynamics) is the study of the behavior of groups and of the interactions of individual group members, aiming to understand the emergence of complex social behaviors among microorganisms, plants and animals, including h ...

'' as an underlying component of historical development in his seminal encyclopedia, ().

14th century: early studies of social conflict and change

North Africa

There is evidence of

early Muslim sociology from the 14th century. In particular, some consider

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

ic scholar

Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732–808 Hijri year, AH) was an Arabs, Arab Islamic scholar, historian, philosopher and sociologist. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest social scientists of the Middle Ages, and cons ...

, a 14th-century

Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

from

Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

, to have been the first sociologist and, thus, the father of sociology. His ''

Muqaddimah

The ''Muqaddimah'' ( "Introduction"), also known as the ''Muqaddimah of Ibn Khaldun'' () or ''Ibn Khaldun's Introduction (writing), Prolegomena'' (), is a book written by the historian Ibn Khaldun in 1377 which presents a view of Universal histo ...

'' (later translated as ''Prolegomena'' in

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

), serving as an introduction to a seven-volume analysis of

universal history Universal history may refer to:

* Universal history (genre), a literary genre

**''Jami' al-tawarikh'', 14th-century work of literature and history, produced by the Mongol Ilkhanate in Persia

** Universal History (Sale et al), ''Universal History'' ...

, would perhaps be the first work to advance

social-scientific reasoning and

social philosophy

Social philosophy is the study and interpretation of society and social institutions in terms of ethical values rather than empirical relations. Social philosophers emphasize understanding the social contexts for political, legal, moral and cultur ...

in formulating theories of

social cohesion

Group cohesiveness, also called group cohesion, social harmony or social cohesion, is the degree or strength of bonds linking members of a social group to one another and to the group as a whole. Although cohesion is a multi-faceted process, it ...

and

social conflict

Social conflict is the struggle for agency or power in society.

Social conflict occurs when two or more people oppose each other in social interaction, and each exerts social power with reciprocity in an effort to achieve incompatible goals bu ...

.

[Mowlana, H. 2001. "Information in the Arab World." ''Cooperation South Journal'' 1.]

Concerning the discipline of sociology, Khaldun conceived a dynamic theory of history that involved conceptualizations of social conflict and social change. He developed the dichotomy of

sedentary life versus

nomadic life, as well as the concept of ''generation'', and the inevitable loss of power that occurs when desert warriors conquer a city. Following his Syrian contemporary,

Sati' al-Husri, the ''Muqaddimah'' may be read as a sociological work; six books of general sociology, to be specific. Topics dealt with in this work include politics, urban life, economics, and knowledge.

The work is based around Khaldun's central concept of ''

asabiyyah'', meaning "social cohesion", "group solidarity", or "tribalism". Khaldun suggests such cohesion arises spontaneously amongst tribes and other small kinship groups, which can then be intensified and enlarged through religious ideology. Khaldun's analysis observes how this cohesion carries groups to power while simultaneously containing within itself the—psychological, sociological, economic, political—seeds of the group's downfall, to be replaced by a new group, dynasty, or empire bound by an even stronger (or at least younger and more vigorous) cohesion.

18th century: European modern origins of sociology

The term "''sociologie''" was first coined by the French essayist

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès (3 May 174820 June 1836), usually known as the Abbé Sieyès (; ), was a French Catholic priest, ''abbé'', and political writer who was a leading political theorist of the French Revolution (1789–1799); he also held off ...

(1773–1799), derived the Latin ; joined with the suffix ''-ology'', 'the study of', itself from the Greek ''lógos'' ().

[Scott, John, and Gordon Marshall, eds. 2005. "Comte, Auguste." ''A Dictionary of Sociology'' (3rd ed.). Oxford: ]Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

. .

19th century: defining sociology

In 1838, the French scholar

Auguste Comte

Isidore Auguste Marie François Xavier Comte (; ; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher, mathematician and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the ...

ultimately gave ''sociology'' the definition that it holds today.

Comte had earlier expressed his work as "social physics", however that term would be appropriated by others such as Belgian statistician

Adolphe Quetelet

Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet FRSF or FRSE (; 22 February 1796 – 17 February 1874) was a Belgian- French astronomer, mathematician, statistician and sociologist who founded and directed the Brussels Observatory and was influential ...

.

European sociology: The Enlightenment and positivism

Henri de Saint-Simon

Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon (; ; 17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), better known as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on po ...

published ''Physiologie sociale'' in 1813, devoting much of his time to the prospect that human society could be steered toward progress if scientists would form an international assembly to influence its course. He argued that scientists could distract groups from war and strife, by focusing their attention to generally improving their societies living conditions. In turn, this would bring multiple cultures and societies together and prevent conflict. Saint-Simon took the idea that everyone had encouraged from the Enlightenment, which was the belief in science, and spun it to be more practical and hands-on for the society. Saint-Simon's main idea was that industrialism would create a new launch in history. He saw that people had been seeing progress as an approach for science, but he wanted them to see it as an approach to all aspects of life. Society was making a crucial change at the time since it was growing out of a declining feudalism. This new path could provide the basis for solving all the old problems society had previously encountered. He was more concerned with the participation of man in the workforce instead of which workforce man choose. His slogan became "All men must work", to which

communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

would add and supply its own slogan "Each according to his capacity."

Auguste Comte and followers

Writing after the original Enlightenment and influenced by the work of Saint-Simon,

political philosopher

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and legitimacy of political institutions, such as states. This field investigates different forms of government, ranging from de ...

of

social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

,

Auguste Comte

Isidore Auguste Marie François Xavier Comte (; ; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher, mathematician and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the ...

hoped to unify all studies of humankind through the scientific understanding of the social realm. His own sociological scheme was typical of the 19th-century humanists; he believed all human life passed through distinct historical stages and that, if one could grasp this progress, one could prescribe the remedies for social ills. Sociology was to be the "queen science" in Comte's schema; all basic physical sciences had to arrive first, leading to the most fundamentally difficult science of human society itself.

Comte has thus come to be viewed as the "Father of Sociology".

Comte delineated his broader philosophy of science in the ''

Course of Positive Philosophy

The ''Course of Positive Philosophy'' (''Cours de Philosophie Positive'') was a series of texts written by the French philosopher of science and founding sociologist, Auguste Comte, between 1830 and 1842. Within the work he unveiled the epistemol ...

'' (c. 1830–1842), whereas his

''A'' ''General View of Positivism'' (1848) emphasized the particular goals of sociology. Comte would be so impressed with his theory of positivism that he referred to it as "the great discovery of the year 1822."

Comte's system is based on the principles of knowledge as seen in three states. This law asserts that any kind of knowledge always begins in ''theological'' form. Here, the knowledge can be explained by a superior supernatural power such as

animism

Animism (from meaning 'breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and in ...

, spirits, or gods. It then passes to the metaphysical form, where the knowledge is explained by abstract philosophical speculation. Finally, the knowledge becomes ''positive'' after being explained scientifically through observation, experimentation, and comparison. The order of the laws was created in order of increasing difficulty.

Comte's description of the development of society is parallel to

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

's own theory of

historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

from capitalism to communism. The two would both be influenced by various

Utopian-socialist thinkers of the day, agreeing that some form of communism would be the climax of societal development.

In later life, Auguste Comte developed a "religion of humanity" to give positivist societies the unity and cohesiveness found through the traditional worship people were used to. In this new "religion", Comte referred to society as the "''Great Being''" and would promote a universal love and harmony taught through the teachings of his industrial system theory.

For his close associate,

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

, it was possible to distinguish between a "good Comte" (the one who wrote ''Course in Positive Philosophy'') and a "bad Comte" (the author of the secular-religious system). The system would be unsuccessful but met with the publication of

Darwin's ''

On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'' to influence the proliferation of various

secular humanist

Secular humanism is a philosophy, belief system, or life stance that embraces human reason, logic, secular ethics, and philosophical naturalism, while specifically rejecting religious dogma, supernaturalism, and superstition as the basi ...

organizations in the 19th century, especially through the work of secularists such as

George Holyoake

George Jacob Holyoake (13 April 1817 – 22 January 1906) was an English secularist, British co-operative movement, co-operator and newspaper editor. He coined the terms secularism in 1851 and "jingoism" in 1878. He edited a secularist paper, '' ...

and

Richard Congreve

Richard Congreve (4 September 1818 – 5 July 1899) was the first English philosopher to openly espouse the Religion of Humanity, the godless form of religious humanism that was introduced by Auguste Comte, as a distinct form of positivism. Con ...

.

Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist.Hill, Michael R. (2002''Harriet Martineau: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives'' Routledge. She wrote from a sociological, holism, holistic, religious and ...

undertook an English translation of ''Cours de Philosophie Positive'' that was published in two volumes in 1853 as ''The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte (freely translated and condensed by Harriet Martineau)''. Comte recommended her volumes to his students instead of his own. Some writers regard Martineau as the first female sociologist. Her introduction of Comte to the English-speaking world and the elements of sociological perspective in her original writings support her credit as a sociologist.

Marx and historical materialism

Both Comte and Marx intended to develop a new scientific ideology in the wake of European

secularization

In sociology, secularization () is a multilayered concept that generally denotes "a transition from a religious to a more worldly level." There are many types of secularization and most do not lead to atheism or irreligion, nor are they automatica ...

. Marx, in the tradition of

Hegelianism

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

, rejected the positivist method and was in turn rejected by the self-proclaimed sociologists of his day. However, in attempting to develop a comprehensive ''science of society'' Marx nevertheless became recognized as a founder of sociology by the mid 20th century.

Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

described Marx as the "true father" of modern sociology, "in so far as anyone can claim the title."

In the 1830s, Karl Marx was part of the

Young Hegelians in

Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, which discussed and wrote about the legacy of the philosopher,

George W. F. Hegel (whose seminal tome, ''

Science of Logic

''Science of Logic'' (), first published between 1812 and 1816, is the work in which Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel outlined his vision of logic. Hegel's logic is a system of ''dialectics'', i.e., a dialectical metaphysics: it is a development o ...

'' was published in 1816). Although, at first sympathetic with the group's strategy of attacking Christianity to undermine the Prussian establishment, he later formed divergent ideas and broke with the Young Hegelians, attacking their views in works such as ''

The German Ideology

''The German Ideology'' (German: ''Die deutsche Ideologie''), also known as ''A Critique of the German Ideology'', is a set of manuscripts written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels around April or early May 1846. Marx and Engels did not find a p ...

''. Witnessing the struggles of the laborers during the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, Marx concluded that religion (or the "ideal") is not the basis of the establishment's power, but rather ownership of capital (or the "material")- processes that employ technologies, land, money and especially human labor-power to create surplus-value—lie at the heart of the establishment's power. This "stood Hegel on his head" as he theorized that, at its core, the engine of history and the structure of society was fundamentally material rather than ideal. He theorized that both the realm of cultural production and political power created ideologies that perpetuated the oppression of the working class and the concentration of wealth within the capitalist class: the owners of the means of production. Marx predicted that the capitalist class would feel compelled to reduce wages or replace laborers with technology, which would ultimately increase wealth among the capitalists. However, as the workers were also the primary consumers of the goods produced, reducing their wages would result in an inevitable collapse in capitalism as a mode of economic production.

Marx also co-operated with

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;["Engels"](_blank)

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.[capitalist class

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted with ...]

of "social murder" for causing workers "life of toil and wretchedness" but with a response that "tales no further trouble in the matter".

This gives them the power over the workers' health and income, "which can degree his life or death".

His book ''

The Condition of the Working Class in England

''The Condition of the Working Class in England'' () is an 1845 book by the German philosopher Friedrich Engels, a study of the industrial working class in Victorian England. Engels' first book, it was originally written in German; an English t ...

'' (1844) studied the life of the proletariat in

Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

,

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

,

Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, and

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

.

Durkheim and French sociology

Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim (; or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French Sociology, sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern soci ...

's work had importance as he was concerned with how societies could maintain their

integrity and coherence in

modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular Society, socio-Culture, cultural Norm (social), norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the ...

, an era in which traditional social and religious ties are no longer assumed, and in which new social

institutions

An institution is a humanly devised structure of rules and norms that shape and constrain social behavior. All definitions of institutions generally entail that there is a level of persistence and continuity. Laws, rules, social conventions and ...

have come into being. Durkheim's first major sociological work was ''

The Division of Labour in Society

''The Division of Labour in Society'' () is the doctoral dissertation of the French sociologist Émile Durkheim, published in 1893. It was influential in advancing sociological theories and thought, with ideas which in turn were influenced by Aug ...

'' (1893). In 1895, he published ''

The Rules of Sociological Method

''The Rules of Sociological Method'' () is a book by Émile Durkheim, first published in 1895. It is recognized as being the direct result of Durkheim's own project of establishing sociology as a positivist social science. Durkheim is seen as on ...

'' and set up the first European department of sociology at what became in 1896 the University of Bordeaux, where he taught from 1887 to 1902; he became France's first professor of sociology.

In 1898, he established the journal ''

L'Année Sociologique''. Durkheim's seminal monograph, ''

Suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

'' (1897), a study of

suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

rates in Catholic and Protestant populations, pioneered modern

social research

Social research is research conducted by social scientists following a systematic plan. Social research methodologies can be classified as quantitative and qualitative.

* Quantitative designs approach social phenomena through quantifiable ...

and served to distinguish social science from

psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

and

political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

. ''

The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life

''The Elementary Forms of Religious Life'' (), published by the French sociologist Émile Durkheim in 1912, is a book that analyzes religion as a social phenomenon. Durkheim attributes the development of religion to the emotional security attain ...

'' (1912) presented a theory of religion, comparing the social and cultural lives of aboriginal and modern societies. Durkheim was deeply preoccupied with the acceptance of sociology as a legitimate

science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

. He refined the

positivism

Positivism is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positivemeaning '' a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. Gerber, ''Soci ...

originally set forth by

Auguste Comte

Isidore Auguste Marie François Xavier Comte (; ; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher, mathematician and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the ...

, promoting what could be considered as a form of

epistemological

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowled ...

realism, as well as the use of the

hypothetico-deductive model

The hypothetico-deductive model or method is a proposed description of the scientific method. According to it, scientific inquiry proceeds by formulating a hypothesis in a form that can be falsifiable, using a test on observable data where the o ...

in social science. For him, sociology was the science of

institution

An institution is a humanly devised structure of rules and norms that shape and constrain social behavior. All definitions of institutions generally entail that there is a level of persistence and continuity. Laws, rules, social conventions and ...

s, if this term is understood in its broader meaning as "beliefs and modes of behaviour instituted by the

collectivity" and its aim was to discover structural

social fact

In sociology, social facts are values, cultural norms, and social structures that transcend the individual and can exercise social control. The French sociologist Émile Durkheim defined the term, and argued that the discipline of sociology shoul ...

s. Durkheim was a major proponent of

structural functionalism

Structural functionalism, or simply functionalism, is "a framework for building theory that sees society as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability".

This approach looks at society through a macro-level o ...

, a foundational perspective in both sociology and

anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

. In his view, social science should be purely

holistic

Holism is the interdisciplinary idea that systems possess properties as wholes apart from the properties of their component parts. Julian Tudor Hart (2010''The Political Economy of Health Care''pp.106, 258

The aphorism "The whole is greater than t ...

;

["The first and most fundamental rule is: Consider social facts as things."

Durkheim, Emile. 1895. '']The Rules of Sociological Method

''The Rules of Sociological Method'' () is a book by Émile Durkheim, first published in 1895. It is recognized as being the direct result of Durkheim's own project of establishing sociology as a positivist social science. Durkheim is seen as on ...

''. p. 14. that is, sociology should study phenomena attributed to society at large, rather than being limited to the specific actions of individuals. He remained a dominant force in French intellectual life until his death in 1917, presenting numerous lectures and published works on a variety of topics, including the

sociology of knowledge

The sociology of knowledge is the study of the relationship between human thought, the social context within which it arises, and the effects that prevailing ideas have on societies. It is not a specialized area of sociology. Instead, it deals w ...

,

morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

,

social stratification

Social stratification refers to a society's categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and political ...

,

religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

,

law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

,

education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

, and

deviance. Durkheimian terms such as "

collective consciousness

Collective consciousness, collective conscience, or collective conscious () is the set of shared beliefs, ideas, and moral attitudes which operate as a unifying force within society.''Collins Dictionary of Sociology'', p93. In general, it doe ...

" have since entered the popular lexicon.

German sociology: Tönnies, the Webers, Simmel

Ferdinand Tönnies

Ferdinand Tönnies (; 26 July 1855 – 8 April 1936) was a German sociologist, economist, and philosopher. He was a significant contributor to sociological theory and field studies, best known for distinguishing between two types of social gro ...

argued that

Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft were the two

normal type

Normal type (in German: ''Normaltyp'') is a typological term in sociology coined by the German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies (1855–1936). It can be considered both as a forerunner of, and a challenge to, the rather better known concept of ...

s of human association. The former was the traditional kind of community with strong social bonds and shared beliefs, while the latter was the modern society in which individualism and rationality had become more dominant.

He also drew a sharp line between the realm of conceptuality and the reality of

social action

In sociology, social action, also known as Weberian social action, is an act which takes into account the actions and reactions of individuals (or ' agents'). According to Max Weber, "Action is 'social' insofar as its subjective meaning takes acc ...

: the first must be treated axiomatically and in a deductive way ('pure' sociology), whereas the second empirically and in an inductive way ('applied' sociology). His ideas were further developed by

Max Weber

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German Sociology, sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economy, political economist who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the social sc ...

, another early German sociologist.

Weber argued for the study of

social action

In sociology, social action, also known as Weberian social action, is an act which takes into account the actions and reactions of individuals (or ' agents'). According to Max Weber, "Action is 'social' insofar as its subjective meaning takes acc ...

through

interpretive (rather than purely

empiricist

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

) means, based on understanding the purpose and

meaning that individuals attach to their own actions. Unlike Durkheim, he did not believe in

monocausal explanations and rather proposed that for any outcome there can be multiple causes. Weber's main intellectual concern was understanding the processes of

rationalisation,

secularisation

In sociology, secularization () is a multilayered concept that generally denotes "a transition from a religious to a more worldly level." There are many types of secularization and most do not lead to atheism or irreligion, nor are they automatica ...

, and "

disenchantment

In social science, disenchantment () is the cultural rationalization and devaluation of religion apparent in modern society. The term was borrowed from Friedrich Schiller by Max Weber to describe the character of a modernized, bureaucratic, ...

", which he associated with the rise of capitalism and

modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular Society, socio-Culture, cultural Norm (social), norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the ...

.

[ Habermas, Jürgen, '']The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity

''The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Twelve Lectures'' () is a 1985 book by the philosopher Jürgen Habermas, in which the author reconstructs and deals in depth with a number of philosophical approaches to the critique of modern reason and ...

'' (originally published in German in 1985), Polity Press (1990), , p. 2. Weber is also known for his thesis combining

economic sociology

Economic sociology is the study of the social cause and effect of various economic phenomena. The field can be broadly divided into a classical period and a contemporary one, known as "new economic sociology".

The classical period was concerned ...

and the

sociology of religion

Sociology of religion is the study of the beliefs, practices and organizational forms of religion using the tools and methods of the discipline of sociology. This objective investigation may include the use both of Quantitative research, quantit ...

, elaborated in his book ''

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism'' () is a book written by Max Weber, a German sociologist, economist, and politician. First written as a series of essays, the original German text was composed in 1904 and 1905, and was trans ...

'', in which he proposed that

ascetic

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

was one of the major "elective affinities" associated with the rise in the Western world of

market

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

*Marketing, the act of sat ...

-driven capitalism and the

rational-legal nation-state

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly or ideally) con ...

. He argued that it was in the basic tenets of Protestantism to boost capitalism. Thus, it can be said that the spirit of capitalism is inherent to Protestant religious values. Against Marx's

historical materialism

Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of Class society, class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods.

Karl Marx stated that Productive forces, techno ...

, Weber emphasised the importance of cultural influences embedded in religion as a means for understanding the genesis of capitalism.

[Weber's references to "Superstructure" and "base" on pages 19 and 35 are unambiguous references to Marxism's base/superstructure theory. (''The Protestant Ethic'' 1905).] The ''Protestant Ethic'' formed the earliest part in Weber's broader investigations into world religion. In another major work, "

Politics as a Vocation

"Politics as a Vocation" () is an essay by German economist and sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920). It originated in the second lecture of a series (the first was '' Science as a Vocation'') he gave in Munich to the "Free (i.e. Non- incorporated ...

", Weber defined the

state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

as an entity that successfully claims a "

monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory". He was also the first to categorise social authority into distinct forms, which he labelled as

charismatic

Charisma () is a personal quality of magnetic charm, persuasion, or appeal.

In the fields of sociology and political science, psychology, and management, the term ''charismatic'' describes a type of leadership.

In Christian theology, the term ...

,

traditional

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examp ...

, and

rational-legal. His analysis of

bureaucracy

Bureaucracy ( ) is a system of organization where laws or regulatory authority are implemented by civil servants or non-elected officials (most of the time). Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments ...

emphasised that modern state institutions are increasingly based on rational-legal authority.

Weber´s wife,

Marianne Weber also became a sociologist in her own right writing about women´s issues. She wrote ''Wife and Mother in the Development of Law'' which was devoted to the analysis of the institution of marriage. Her conclusion was that marriage is "a complex and ongoing negotiation over power and intimacy, in which money, women's work, and sexuality are key issues".

[Lengermann and Jill Niebrugge-Brantley, 204] Another theme in her work was that women's work could be used to "map and explain the construction and reproduction of the social person and the social world".

[Lengermann and Jill Niebrugge-Brantley, 207] Human work creates cultural products ranging from small, daily values such as cleanliness and honesty to larger, more abstract phenomena like philosophy and language.

Georg Simmel

Georg Simmel (; ; 1 March 1858 – 26 September 1918) was a German sociologist, philosopher, and critic. Simmel was influential in the field of sociology. Simmel was one of the first generation of German sociologists: his neo-Kantian approach ...

was one of the first generation of German sociologists: his

neo-Kantian

In late modern philosophy, neo-Kantianism () was a revival of the 18th-century philosophy of Immanuel Kant. The neo-Kantians sought to develop and clarify Kant's theories, particularly his concept of the thing-in-itself and his moral philosophy ...

approach laid the foundations for sociological

antipositivism

In social science, antipositivism (also interpretivism, negativism or antinaturalism) is a theoretical stance which proposes that the social realm cannot be studied with the methods of investigation utilized within the natural sciences, and th ...

, asking 'What is society?' in a direct allusion to Kant's question 'What is nature?',

[Levine, Donald (ed) (1971) ''Simmel: On individuality and social forms''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 6, .] presenting pioneering analyses of social individuality and fragmentation. For Simmel, culture referred to "the cultivation of individuals through the agency of external forms which have been objectified in the course of history".

[ Simmel discussed social and cultural phenomena in terms of "forms" and "contents" with a transient relationship; form becoming content, and vice versa, dependent on the context. In this sense he was a forerunner to structuralist styles of reasoning in the ]social sciences

Social science (often rendered in the plural as the social sciences) is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of society, societies and the Social relation, relationships among members within those societies. The term was former ...

. With his work on the metropolis

A metropolis () is a large city or conurbation which is a significant economic, political, and cultural area for a country or region, and an important hub for regional or international connections, commerce, and communications.

A big city b ...

, Simmel was a precursor of urban sociology

Urban sociology is the sociological study of cities and urban life. One of the field’s oldest sub-disciplines, urban sociology studies and examines the social, historical, political, cultural, economic, and environmental forces that have shaped ...

, symbolic interactionism

Symbolic interactionism is a sociological theory that develops from practical considerations and alludes to humans' particular use of shared language to create common symbols and meanings, for use in both intra- and interpersonal communication.

...

and social network

A social network is a social structure consisting of a set of social actors (such as individuals or organizations), networks of Dyad (sociology), dyadic ties, and other Social relation, social interactions between actors. The social network per ...

analysis. Simmel's most famous works today are ''The Problems of the Philosophy of History'' (1892), ''The Philosophy of Money

''The Philosophy of Money'' (1900; )Simmel, Georg. 2004 900br>''The Philosophy of Money'' (3rd enlarged ed.) edited by D. Frisby, translated by D. Frisby and T. Bottomore. London: Routledge. – via Eddie Jackson. is a book on economic sociolog ...

'' (1900), ''The Metropolis and Mental Life

"The Metropolis and Mental Life" ( German: "Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben") is a 1903 essay by the German sociologist, Georg Simmel.

Overview

One of Simmel's most widely read works, "The Metropolis and Mental Life" was originally pro ...

'' (1903), ''Soziologie'' (1908, inc. ''The Stranger'', ''The Social Boundary'', ''The Sociology of the Senses'', ''The Sociology of Space'', and ''On The Spatial Projections of Social Forms''), and ''Fundamental Questions of Sociology'' (1917).

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

(1820–1903), the English philosopher, was one of the most popular and influential 19th-century sociologists, although his work has largely fallen out of favor in contemporary sociology. The early sociology of Spencer came about broadly as a reaction to Comte and Marx; writing before and after the Darwinian revolution in biology, Spencer attempted to reformulate the discipline in socially Darwinistic terms. In fact, his early writings show a coherent theory of general evolution several years before Darwin published anything on the subject.Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim (; or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French Sociology, sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern soci ...

, defined their ideas in relation to his. Durkheim's '' Division of Labour in Society'' is to a large extent an extended debate with Spencer from whose sociology Durkheim borrowed extensively.biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

, Spencer coined the term "survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

" as a basic mechanism by which more effective socio-cultural forms progressed. This means that the strongest members of society should not help the weaker members of society. An example is that the richest should remain rich and the poor should also remain poor, as the rich people would not help the poor.

In the 20th century, Spencer's work became less influential in sociology because of his social Darwinist

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economic ...

views on race, which are widely considered a form of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

. For example, in his ''Social Statics'' (1850), he argued that imperialism had served civilization by clearing the inferior races off the earth: "The forces which are working out the great scheme of perfect happiness, taking no account of incidental suffering, exterminate such sections of mankind as stand in their way. … Be he human or be he brute – the hindrance must be got rid of." Largely because of his work on race, Spencer is now described in the academy as "of all the great Victorian thinkers... he onewhose reputation has fallen the farthest."

North American sociology

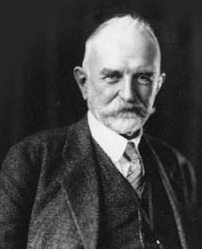

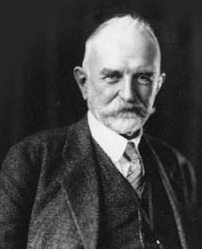

Lester Frank Ward

A contemporary of Spencer, Lester Frank Ward is often described as a father of American sociology and served as the first president of the American Sociological Association

The American Sociological Association (ASA) is a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the discipline and profession of sociology. Founded in December 1905 as the American Sociological Society at Johns Hopkins University by a group of fi ...

in 1905 and served as such until 1907. He published ''Dynamic Sociology'' in 1883; ''Outlines of Sociology'' in 1898; ''Pure Sociology'' in 1903; and ''Applied Sociology'' in 1906. Also in 1906, at the age of 65 he was appointed as professor of sociology at Brown University

Brown University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Providence, Rhode Island, United States. It is the List of colonial colleges, seventh-oldest institution of higher education in the US, founded in 1764 as the ' ...

.

W. E. B. Du Bois

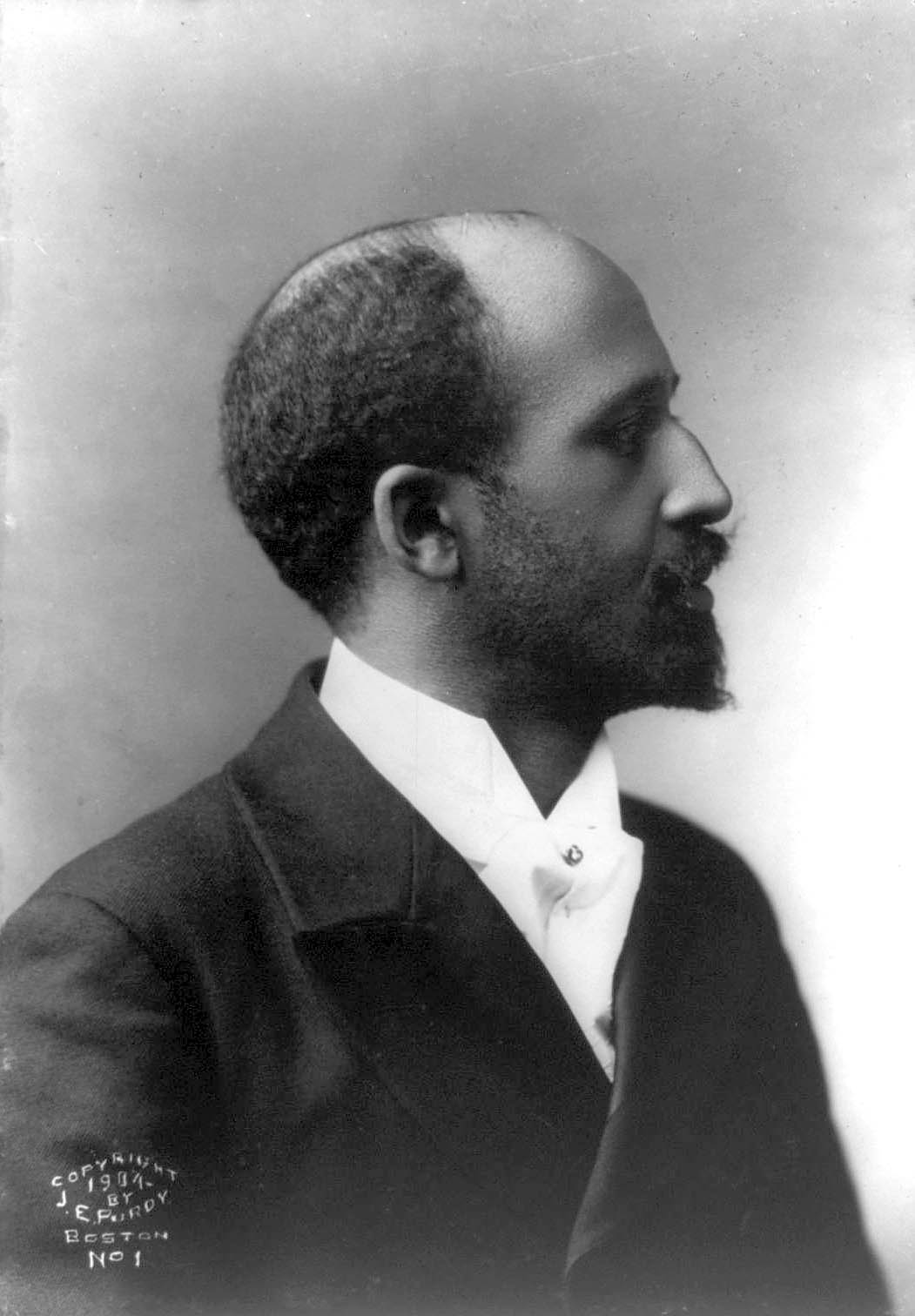

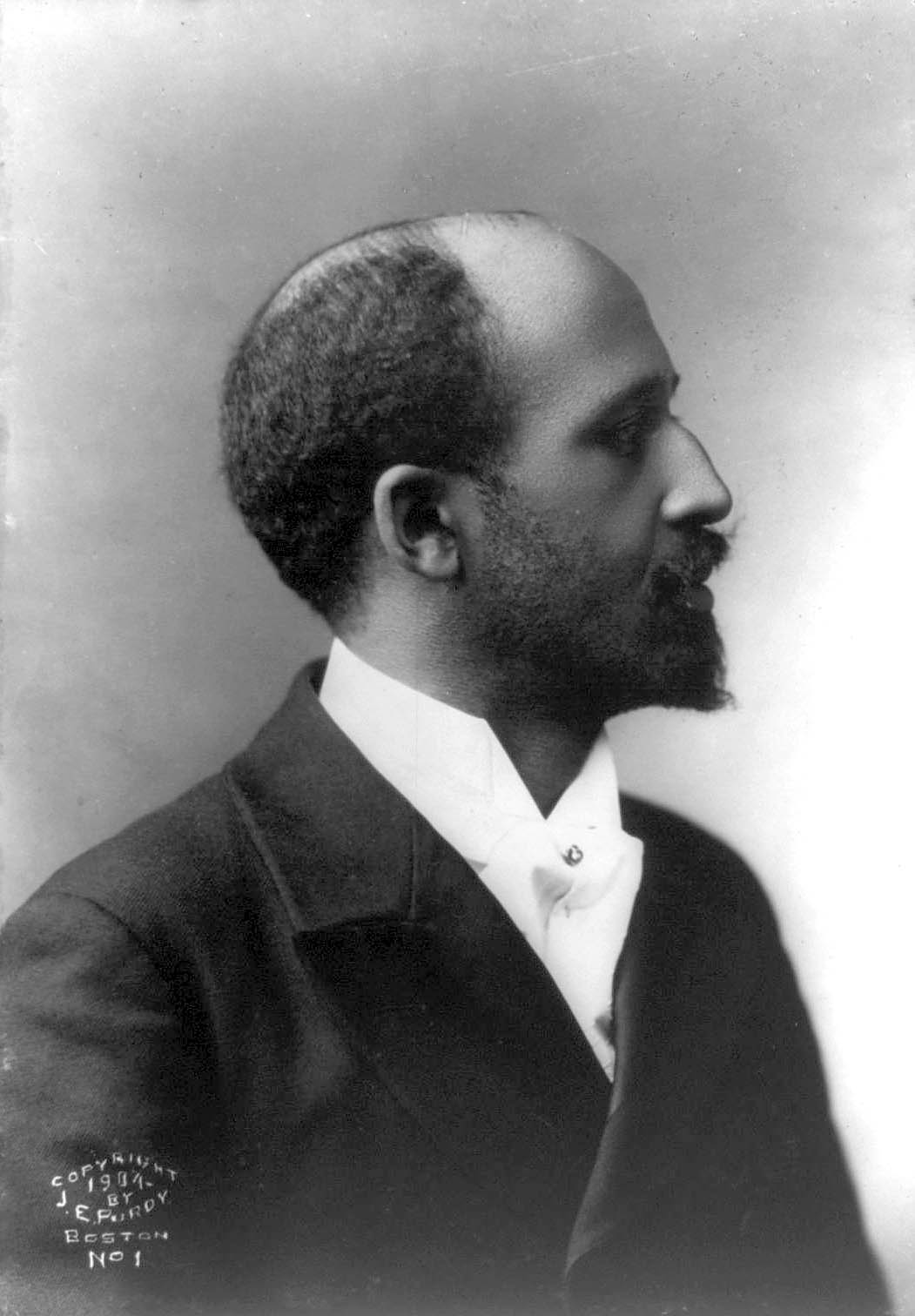

In July 1897,

In July 1897, W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

produced his first major ''The Philadelphia Negro

''The Philadelphia Negro'' is a sociology, sociological and social epidemiology, epidemiological study of African Americans in Philadelphia that was written by W. E. B. Du Bois, commissioned by the University of Pennsylvania and published in 18 ...

'' (1899), a detailed and comprehensive sociological study of the African-American people of Philadelphia, based on the field work he did in 1896–1897. The work was a breakthrough in scholarship because it was the first scientific study of African Americans and a significant contribution to early scientific sociology in the U.S.["''The Philadelphia Negro'' stands as a classic in (urban) sociology and African American studies because it was the first scientific study of the Negro and the first scientific sociological study in the United States."

Donaldson, Shawn. 2001.]

The Philadelphia Negro

" Pp. 164–65 in ''W.E.B. Du Bois: An Encyclopedia'', edited by G. Horne and M. Young. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 165.["The pioneering studies of African cultures and Afro-American realities and history initiated by W. E. B. Du Bois from 1894 until 1915 stand not only as the first studies of black people on a firm scientific basis altogetherwhether classified among the social or historical sciencesbut they also represent the earliest ethnographies of Afro-America as well as a major contribution to the earliest corpus of social scientific literature from the United States." (Lange 1983).] In the study, Du Bois coined the phrase "the submerged tenth" to describe the black underclass. Later in 1903 he popularized the term, the "Talented Tenth

The talented tenth is a term that designated a leadership class of African Americans in the early 20th century. Although the term was created by white Northern philanthropists, it is primarily associated with W. E. B. Du Bois, who used it as the ...

", applied to society's elite class.[Lewis, p. 148.] Du Bois's terminology reflected his opinion that the elite of a nation, both black and white, were critical to achievements in culture and progress.The Souls of Black Folk

''The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches'' is a 1903 work of American literature by W. E. B. Du Bois. It is a seminal work in the history of sociology and a cornerstone of African-American literature.

The book contains several essays on ...

'' (1903), a collection of 14 essays. The introduction famously proclaimed that "the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line." A major theme of the work was the double consciousness

Double consciousness is the dual self-perception experienced by Hierarchy, subordinated or Colonization, colonized groups in an Oppression, oppressive society. The term and the idea were first published in W. E. B. Du Bois, W. E. B. Du Bois's Aut ...

faced by African Americans: being both American and black. This was a unique identity which, according to Du Bois, had been a handicap in the past, but could be a strength in the future, "Henceforth, the destiny of the race could be conceived as leading neither to assimilation nor separatism but to proud, enduring hyphenation."

Other precursors

Many other philosophers and academics were influential in the development of sociology, not least the Enlightenment theorists of social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

, and historians such as Adam Ferguson

Adam Ferguson, (Scottish Gaelic: ''Adhamh MacFhearghais''), also known as Ferguson of Raith (1 July N.S. /20 June O.S. 1723 – 22 February 1816), was a Scottish philosopher and historian of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Ferguson was sympath ...

(1723–1816). For his theory on social interaction

A social relation is the fundamental unit of analysis within the social sciences, and describes any voluntary or involuntary interpersonal relationship between two or more conspecifics within and/or between groups. The group can be a language or ...

, Ferguson has himself been described as "the father" of modern sociology. Ferguson argued that capitalism was diminishing social bonds that traditionally held communities together. Other early works to appropriate the term 'sociology' included ''A Treatise on Sociology, Theoretical and Practical'' by the North American lawyer Henry Hughes and ''Sociology for the South, or the Failure of Free Society'' by the American lawyer George Fitzhugh. Both books were published in 1854, in the context of the debate over slavery in the antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern US

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum architectu ...

US. Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist.Hill, Michael R. (2002''Harriet Martineau: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives'' Routledge. She wrote from a sociological, holism, holistic, religious and ...

, a Whig social theorist and the English translator of many of Comte's works, has been cited as the first female sociologist.United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, she noted how the theoretical ideal of equality apparent in the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

were not reflected in the social reality of the country, which marginalised women and practiced slavery.Robert Michels

Robert Michels (; 9 January 1876 – 3 May 1936) was a German-born Italian sociologist who contributed to elite theory by describing the political behavior of intellectual elites.

He belonged to the Italian school of elitism. He is best kno ...

(1876–1936), Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (29 July 180516 April 1859), was a French Aristocracy (class), aristocrat, diplomat, political philosopher, and historian. He is best known for his works ''Democracy in America'' (appearing in t ...

(1805–1859), Vilfredo Pareto

Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto (; ; born Wilfried Fritz Pareto; 15 July 1848 – 19 August 1923) was an Italian polymath, whose areas of interest included sociology, civil engineering, economics, political science, and philosophy. He made severa ...

(1848–1923) and Thorstein Veblen

Thorstein Bunde Veblen (; July 30, 1857 – August 3, 1929) was an American Economics, economist and Sociology, sociologist who, during his lifetime, emerged as a well-known Criticism of capitalism, critic of capitalism.

In his best-known book ...

(1857–1926). The classical sociological texts broadly differ from political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

in the attempt to remain scientific, systematic, structural, or dialectic

Dialectic (; ), also known as the dialectical method, refers originally to dialogue between people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to arrive at the truth through reasoned argument. Dialectic resembles debate, but the ...

al, rather than purely moral, normative

Normativity is the phenomenon in human societies of designating some actions or outcomes as good, desirable, or permissible, and others as bad, undesirable, or impermissible. A Norm (philosophy), norm in this sense means a standard for evaluatin ...

or subjective. The new class relations associated with the development of Capitalism are also key, further distinguishing sociological texts from the political philosophy of the Renaissance and Enlightenment eras.

19th century: institutionalization

Rise as an academic discipline

Europe

Formal institutionalization of sociology as an academic discipline began when Emile Durkheim founded the first French department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux

The University of Bordeaux (, ) is a public research university based in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in southwestern France.

It has several campuses in the cities and towns of Bordeaux, Dax, Gradignan, Périgueux, Pessac, and Talence. There are al ...

in 1895. In 1896, he established the journal '' L'Année Sociologique''.

A course entitled "sociology" was taught for the first time in the United States in 1875 by William Graham Sumner

William Graham Sumner (October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910) was an American clergyman, social scientist, and neoclassical liberal. He taught social sciences at Yale University, where he held the nation's first professorship in sociology and bec ...

, drawing upon the thought of Comte and Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

rather than the work of Durkheim. In 1890, the oldest continuing sociology course in the United States began at the University of Kansas

The University of Kansas (KU) is a public research university with its main campus in Lawrence, Kansas, United States. Two branch campuses are in the Kansas City metropolitan area on the Kansas side: the university's medical school and hospital ...

, lectured by Frank Blackmar. The Department of History and Sociology at the University of Kansas was established in 1891 and the first full-fledged independent university department of sociology was established in 1892 at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

by Albion W. Small (1854–1926), who in 1895 founded the ''American Journal of Sociology

The ''American Journal of Sociology'' is a peer-reviewed bi-monthly academic journal that publishes original research and book reviews in the field of sociology and related social sciences. It was founded in 1895 as the first journal in its disci ...

''. American sociology arose on a broadly independent trajectory to European sociology. George Herbert Mead

George Herbert Mead (February 27, 1863 – April 26, 1931) was an American philosopher, Sociology, sociologist, and psychologist, primarily affiliated with the University of Chicago. He was one of the key figures in the development of pragmatis ...

and Charles H. Cooley were influential in the development of symbolic interactionism

Symbolic interactionism is a sociological theory that develops from practical considerations and alludes to humans' particular use of shared language to create common symbols and meanings, for use in both intra- and interpersonal communication.

...

and social psychology

Social psychology is the methodical study of how thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others. Although studying many of the same substantive topics as its counterpart in the field ...

at the University of Chicago, while Lester Ward emphasized the central importance of the scientific method with the publication of ''Dynamic Sociology'' in 1883.

The first sociology department in the United Kingdom was founded at the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), established in 1895, is a public research university in London, England, and a member institution of the University of London. The school specialises in the social sciences. Founded ...

in 1904. In 1919 a sociology department was established in Germany at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich, LMU or LMU Munich; ) is a public university, public research university in Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Originally established as the University of Ingolstadt in 1472 by Duke ...

by Max Weber, who had established a new antipositivist

In social science, antipositivism (also interpretivism, negativism or antinaturalism) is a theoretical stance which proposes that the social realm cannot be studied with the methods of investigation utilized within the natural sciences, and th ...

sociology. The "Institute for Social Research" at the University of Frankfurt (later to become the "Frankfurt School" of critical theory) was founded in 1923. 9Critical theory would take on something of a life of its own after WW2, influencing literary theory and the "Birmingham School" of cultural studies.

The University of Frankfurt's advances along with the close proximity to the research institute for sociology made Germany a powerful force in leading sociology at that time. In 1918, Frankfurt received the funding to create sociology's first department chair. The Germany's groundbreaking work influenced its government to add the position of Minister of Culture to advance the country as a whole. The remarkable collection of men who were contributing to the sociology department at Frankfurt were soon getting worldwide attention and began being referred to as the "Frankfurt school." Here they studied new perspectives on Marx' theories, and went into depth in the works of Weber and Freud. Most of these men would soon be forced out of Germany by the Nazis, moving to America. In the United States they had a significant influence on social research. This forced relocation of sociologists enabled sociology in America to rise up to the standards of European studies of sociology by planting some of Europe's greatest sociologists in America.

North America

In 1905 the

In 1905 the American Sociological Association

The American Sociological Association (ASA) is a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the discipline and profession of sociology. Founded in December 1905 as the American Sociological Society at Johns Hopkins University by a group of fi ...

, the world's largest association of professional sociologists, was founded, and Lester F. Ward was selected to serve as the first President of the new society.