Socialist Movement For Integration Politicians on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Socialism is an

The fundamental objective of socialism is to attain an advanced level of material production and therefore greater productivity, efficiency and rationality as compared to capitalism and all previous systems, under the view that an expansion of human productive capability is the basis for the extension of freedom and equality in society. Many forms of socialist theory hold that human behaviour is largely shaped by the social environment. In particular, socialism holds that social

The fundamental objective of socialism is to attain an advanced level of material production and therefore greater productivity, efficiency and rationality as compared to capitalism and all previous systems, under the view that an expansion of human productive capability is the basis for the extension of freedom and equality in society. Many forms of socialist theory hold that human behaviour is largely shaped by the social environment. In particular, socialism holds that social

Marx and Engels held the view that the consciousness of those who earn a wage or salary (the working class in the broadest Marxist sense) would be moulded by their conditions of

Marx and Engels held the view that the consciousness of those who earn a wage or salary (the working class in the broadest Marxist sense) would be moulded by their conditions of

In ''

In ''

Socialist economics starts from the premise that "individuals do not live or work in isolation but live in cooperation with one another. Furthermore, everything that people produce is in some sense a social product, and everyone who contributes to the production of a good is entitled to a share in it. Society as whole, therefore, should own or at least control property for the benefit of all its members".

The original conception of socialism was an economic system whereby production was organised in a way to directly produce goods and services for their utility (or use-value in classical and

Socialist economics starts from the premise that "individuals do not live or work in isolation but live in cooperation with one another. Furthermore, everything that people produce is in some sense a social product, and everyone who contributes to the production of a good is entitled to a share in it. Society as whole, therefore, should own or at least control property for the benefit of all its members".

The original conception of socialism was an economic system whereby production was organised in a way to directly produce goods and services for their utility (or use-value in classical and

A self-managed, decentralised economy is based on autonomous self-regulating economic units and a decentralised mechanism of resource allocation and decision-making. This model has found support in notable classical and neoclassical economists including

A self-managed, decentralised economy is based on autonomous self-regulating economic units and a decentralised mechanism of resource allocation and decision-making. This model has found support in notable classical and neoclassical economists including  One such system is the cooperative economy, a largely free

One such system is the cooperative economy, a largely free

Social democrats advocate a peaceful, evolutionary transition of the economy to socialism through progressive social reform. It asserts that the only acceptable constitutional form of government is

Social democrats advocate a peaceful, evolutionary transition of the economy to socialism through progressive social reform. It asserts that the only acceptable constitutional form of government is

Ethical socialism appeals to socialism on ethical and moral grounds as opposed to economic, egoistic, and consumeristic grounds. It emphasizes the need for a morally conscious economy based upon the principles of altruism, cooperation, and social justice while opposing possessive individualism. Ethical socialism has been the official philosophy of mainstream socialist parties.

Liberal socialism incorporates liberal principles to socialism. It has been compared to

Ethical socialism appeals to socialism on ethical and moral grounds as opposed to economic, egoistic, and consumeristic grounds. It emphasizes the need for a morally conscious economy based upon the principles of altruism, cooperation, and social justice while opposing possessive individualism. Ethical socialism has been the official philosophy of mainstream socialist parties.

Liberal socialism incorporates liberal principles to socialism. It has been compared to

Blanquism is a conception of revolution named for

Blanquism is a conception of revolution named for

Libertarian socialism, sometimes called

Libertarian socialism, sometimes called

"I1. Isn't libertarian socialism an oxymoron" in

An Anarchist FAQ It emphasises

Socialist feminism is a branch of

Socialist feminism is a branch of

What remains of socialism?

', in Patrick Riordan (dir.), Values in Public life: aspects of common goods (Berlin, LIT Verlag, 2007), pp. 11–34. * * * * * * * * * *

Socialism

– entry at the ''

economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

and political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

encompassing diverse economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

and social system

In sociology, a social system is the patterned network of relationships constituting a coherent whole that exist between individuals, groups, and institutions. It is the formal Social structure, structure of role and status that can form in a smal ...

s characterised by social ownership

Social ownership is a type of property where an asset is recognized to be in the possession of society as a whole rather than individual members or groups within it. Social ownership of the means of production is the defining characteristic of ...

of the means of production

In political philosophy, the means of production refers to the generally necessary assets and resources that enable a society to engage in production. While the exact resources encompassed in the term may vary, it is widely agreed to include the ...

, as opposed to private ownership

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental Capacity (law), legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from Collective ownership ...

. It describes the economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

, political

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

, and social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

theories and movements

Movement may refer to:

Generic uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Movement (sign language), a hand movement when signing

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

* Movement (music), a division of a larger c ...

associated with the implementation of such systems. Social ownership can take various forms, including public

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociology, sociological concept of the ''Öf ...

, community

A community is a social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place, set of norms, culture, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given g ...

, collective

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an e ...

, cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomy, autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned a ...

, or employee

Employment is a relationship between two party (law), parties Regulation, regulating the provision of paid Labour (human activity), labour services. Usually based on a employment contract, contract, one party, the employer, which might be a cor ...

.: "Just as private ownership defines capitalism, social ownership defines socialism. The essential characteristic of socialism in theory is that it destroys social hierarchies, and therefore leads to a politically and economically egalitarian society. Two closely related consequences follow. First, every individual is entitled to an equal ownership share that earns an aliquot part of the total social dividend ... Second, in order to eliminate social hierarchy in the workplace, enterprises are run by those employed, and not by the representatives of private or state capital. Thus, the well-known historical tendency of the divorce between ownership and management is brought to an end. The society — i.e. every individual equally — owns capital and those who work are entitled to manage their own economic affairs." As one of the main ideologies on the political spectrum

A political spectrum is a system to characterize and classify different Politics, political positions in relation to one another. These positions sit upon one or more Geometry, geometric Coordinate axis, axes that represent independent political ...

, socialism is the standard left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

ideology in most countries. Types of socialism vary based on the role of markets and planning in resource allocation

In economics, resource allocation is the assignment of available resources to various uses. In the context of an entire economy, resources can be allocated by various means, such as markets, or planning.

In project management, resource allocatio ...

, and the structure of management in organizations.

Socialist systems are divided into non-market and market

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

*Marketing, the act of sat ...

forms. A non-market socialist system seeks to eliminate the perceived inefficiencies, irrationalities, unpredictability, and crises

A crisis (: crises; : critical) is any event or period that will lead to an unstable and dangerous situation affecting an individual, group, or all of society. Crises are negative changes in the human or environmental affairs, especially when ...

that socialists traditionally associate with capital accumulation

Capital accumulation is the dynamic that motivates the pursuit of profit, involving the investment of money or any financial asset with the goal of increasing the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the form ...

and the profit

Profit may refer to:

Business and law

* Profit (accounting), the difference between the purchase price and the costs of bringing to market

* Profit (economics), normal profit and economic profit

* Profit (real property), a nonpossessory inter ...

system. Market socialism

Market socialism is a type of economic system involving social ownership of the means of production within the framework of a market economy. Various models for such a system exist, usually involving cooperative enterprises and sometimes a mix ...

retains the use of monetary prices, factor markets and sometimes the profit motive

In economics, the profit motive is the motivation of firms that operate so as to maximize their profits. Mainstream microeconomic theory posits that the ultimate goal of a business is "to make money" - not in the sense of increasing the firm ...

. As a political force, socialist parties and ideas exercise varying degrees of power and influence, heading national governments in several countries. Socialist politics have been internationalist and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

; organised through political parties and opposed to party politics; at times overlapping with trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

s and other times independent and critical of them, and present in industrialised and developing nations. Social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

originated within the socialist movement, supporting economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

and social interventions to promote social justice

Social justice is justice in relation to the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society where individuals' rights are recognized and protected. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has of ...

. While retaining socialism as a long-term goal, in the post-war period social democracy embraced a mixed economy

A mixed economy is an economic system that includes both elements associated with capitalism, such as private businesses, and with socialism, such as nationalized government services.

More specifically, a mixed economy may be variously de ...

based on Keynesianism

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomics, macroeconomic theories and Economic model, models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongl ...

within a predominantly developed capitalist market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production, and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand. The major characteristic of a mark ...

and liberal democratic

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal democracy are: ...

polity that expands state intervention to include income redistribution

Redistribution of income and wealth is the transfer of income and wealth (including physical property) from some individuals to others through a social mechanism such as taxation, welfare, public services, land reform, monetary policies, ...

, regulation

Regulation is the management of complex systems according to a set of rules and trends. In systems theory, these types of rules exist in various fields of biology and society, but the term has slightly different meanings according to context. Fo ...

, and a welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

.

The socialist political movement

A political movement is a collective attempt by a group of people to change government policy or social values. Political movements are usually in opposition to an element of the status quo, and are often associated with a certain ideology. Some t ...

includes political philosophies that originated in the revolutionary movements of the mid-to-late 18th century and out of concern for the social problems

A social issue is a problem that affects many people within a society. It is a group of common problems in present-day society that many people strive to solve. It is often the consequence of factors extending beyond an individual's control. Soc ...

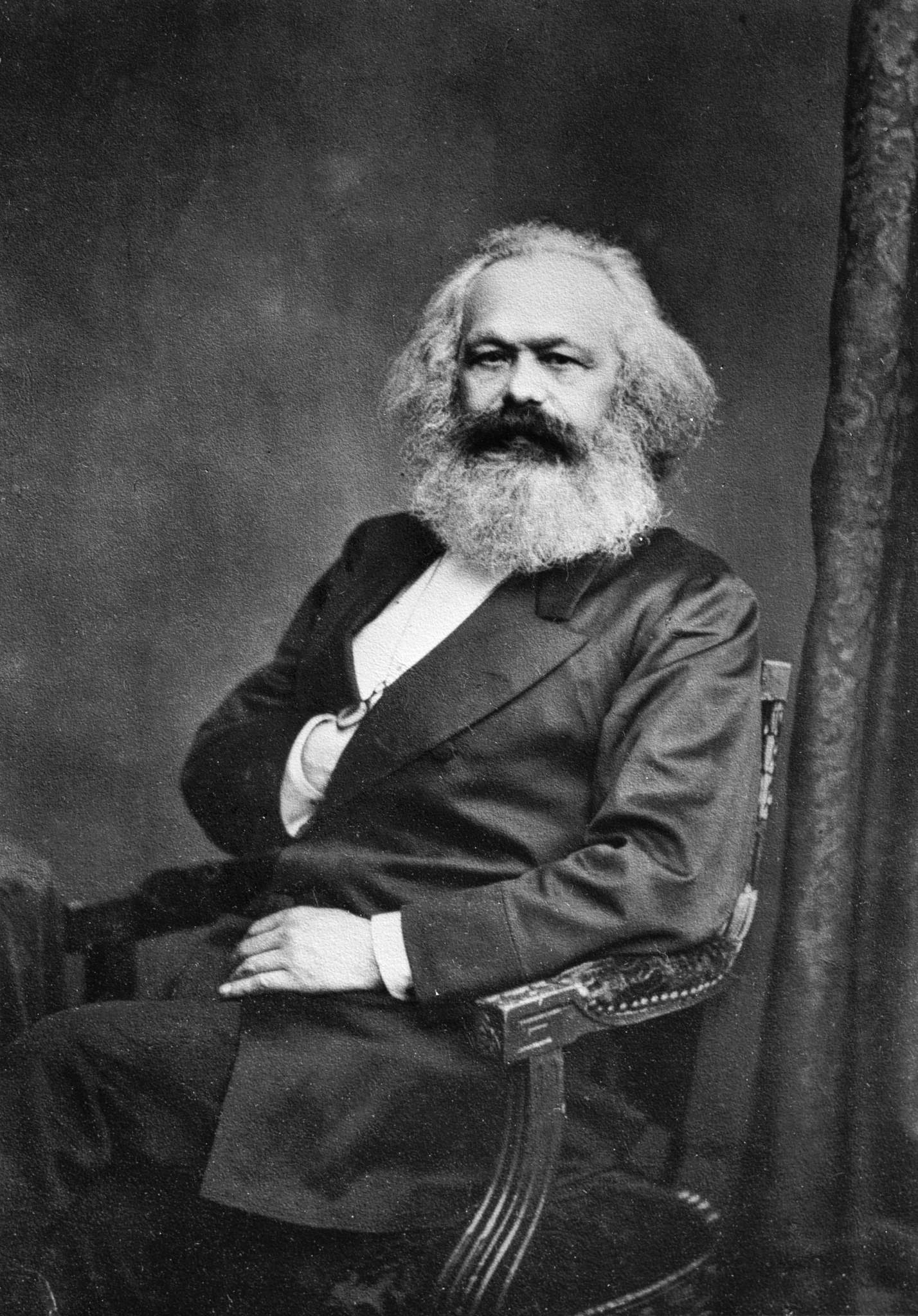

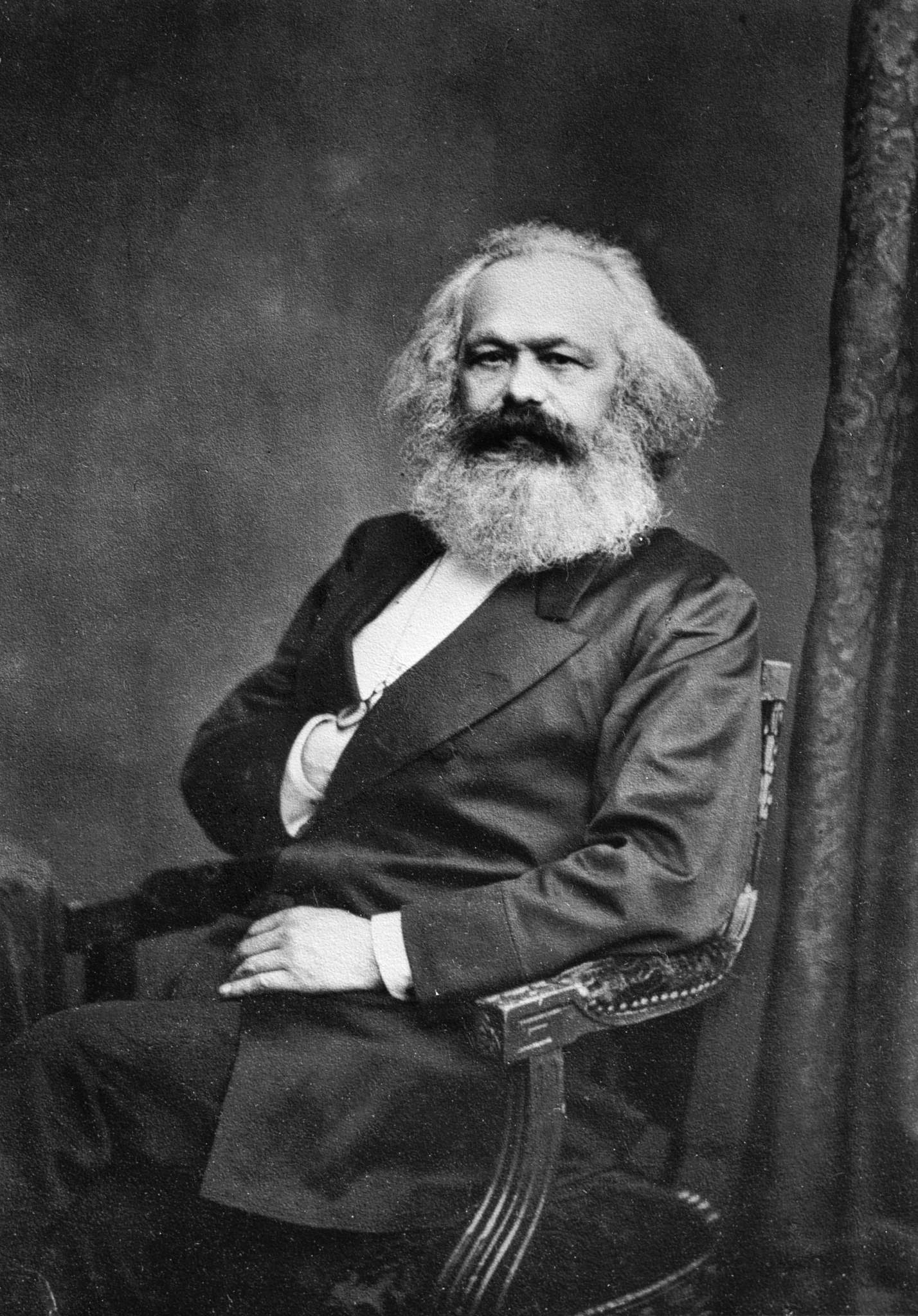

that socialists associated with capitalism. By the late 19th century, after the work of Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and his collaborator Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.anti-capitalism Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. Anti-capitalists seek to combat the worst effects of capitalism and to eventually replace capitalism with an alternati ...

and advocacy for a post-capitalist system based on some form of social ownership of the means of production. By the early 1920s, ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.anti-capitalism Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. Anti-capitalists seek to combat the worst effects of capitalism and to eventually replace capitalism with an alternati ...

communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

and social democracy had become the two dominant political tendencies within the international socialist movement, with socialism itself becoming the most influential secular movement of the 20th century. Many socialists also adopted the causes of other social movements, such as feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

, environmentalism

Environmentalism is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement about supporting life, habitats, and surroundings. While environmentalism focuses more on the environmental and nature-related aspects of green ideology and politics, ecolog ...

, and progressivism

Progressivism is a Left-right political spectrum, left-leaning political philosophy and Reformism, reform political movement, movement that seeks to advance the human condition through social reform. Adherents hold that progressivism has unive ...

.

Although the emergence of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

as the world's first socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. This article is about states that refer to themselves as socialist states, and not specifically ...

led to the widespread association of socialism with the Soviet economic model, it has since shifted in favour of democratic socialism

Democratic socialism is a left-wing economic ideology, economic and political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and wor ...

. Academics sometimes recognised the mixed economies

A mixed economy is an economic system that includes both elements associated with capitalism, such as private businesses, and with socialism, such as nationalized government services.

More specifically, a mixed economy may be variously de ...

of several Western European and Nordic countries as "democratic socialist", although the system of these countries, with only limited social ownership (generally in the form of state ownership), is more usually described as social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

. Following the revolutions of 1989

The revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, were a revolutionary wave of liberal democracy movements that resulted in the collapse of most Communist state, Marxist–Leninist governments in the Eastern Bloc and other parts ...

, many of these countries moved away from socialism as a neoliberal

Neoliberalism is a political and economic ideology that advocates for free-market capitalism, which became dominant in policy-making from the late 20th century onward. The term has multiple, competing definitions, and is most often used pej ...

consensus replaced the social democratic consensus in the advanced capitalist world. In parallel, many former socialist politicians and political parties embraced "Third Way

The Third Way is a predominantly centrist political position that attempts to reconcile centre-right and centre-left politics by advocating a varying synthesis of Right-wing economics, right-wing economic and Left-wing politics, left-wing so ...

" politics, remaining committed to equality and welfare while abandoning public ownership and class-based politics. Socialism experienced a resurgence in popularity in the 2010s.

Etymology

According to Andrew Vincent, " e word 'socialism' finds its root in the Latin , which means to combine or to share. The related, more technical term in Roman and then medieval law was . This latter word could mean companionship and fellowship as well as the more legalistic idea of a consensual contract between freemen". Initial use of ''socialism'' was claimed byPierre Leroux

Pierre Henri Leroux (; 7 April 1797 – 12 April 1871) was a French philosopher and political economy, political economist. He was born at Bercy, now a part of Paris, France, Paris, the son of an artisan.

Life

His education was interrupted by ...

, who alleged he first used the term in the Parisian journal in 1832. Leroux was a follower of Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon (; ; 17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), better known as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on po ...

, one of the founders of what would later be labelled utopian socialism

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

. Socialism contrasted with the liberal doctrine of individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

that emphasized the moral worth of the individual while stressing that people act or should act as if they are in isolation from one another. The original utopian socialists condemned this doctrine of individualism for failing to address social concerns during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, including poverty, oppression, and vast wealth inequality

The distribution of wealth is a comparison of the wealth of various members or groups in a society. It shows one aspect of economic inequality or economic heterogeneity.

The distribution of wealth differs from the income distribution in that ...

. They viewed their society as harming community life by basing society on competition. They presented socialism as an alternative to liberal individualism based on the shared ownership of resources. Saint-Simon proposed economic planning

Economic planning is a resource allocation mechanism based on a computational procedure for solving a constrained maximization problem with an iterative process for obtaining its solution. Planning is a mechanism for the allocation of resources ...

, scientific administration and the application of scientific understanding to the organisation of society. By contrast, Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist, political philosopher and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement, co-operative movement. He strove to ...

proposed to organise production and ownership via cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomy, autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned a ...

s. ''Socialism'' is also attributed in France to Marie Roch Louis Reybaud while in Britain it is attributed to Owen, who became one of the fathers of the cooperative movement

The history of the cooperative movement concerns the origins and history of cooperatives across the world. Although cooperative arrangements, such as mutual insurance, and principles of cooperation existed long before, the cooperative movement bega ...

.

The definition and usage of ''socialism'' settled by the 1860s, with the term ''socialist'' replacing ''associationist

Associationism is the idea that mental processes operate by the association of one mental state with its successor states. It holds that all mental processes are made up of discrete psychological elements and their combinations, which are believ ...

'', ''co-operative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democr ...

'', '' mutualist'' and ''collectivist

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and groups. Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, struct ...

'', which had been used as synonyms, while the term ''communism'' fell out of use during this period. An early distinction between ''communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

'' and ''socialism'' was that the latter aimed to only socialise production while the former aimed to socialise both production

Production may refer to:

Economics and business

* Production (economics)

* Production, the act of manufacturing goods

* Production, in the outline of industrial organization, the act of making products (goods and services)

* Production as a stat ...

and consumption

Consumption may refer to:

* Eating

*Resource consumption

*Tuberculosis, an infectious disease, historically known as consumption

* Consumer (food chain), receipt of energy by consuming other organisms

* Consumption (economics), the purchasing of n ...

(in the form of free access to final goods). By 1888, Marxists

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, and ...

employed ''socialism'' in place of ''communism'' as the latter had come to be considered an old-fashioned synonym for ''socialism''. It was not until after the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. It was led by Vladimir L ...

that ''socialism'' was appropriated by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

to mean a stage between capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

and communism. He used it to defend the Bolshevik program from Marxist criticism that Russia's productive forces

Productive forces, productive powers, or forces of production ( German: ''Produktivkräfte'') is a central idea in Marxism and historical materialism.

In Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' own critique of political economy, it refers to the combin ...

were not sufficiently developed for communism. The distinction between ''communism'' and ''socialism'' became salient in 1918 after the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

renamed itself to the All-Russian Communist Party, interpreting ''communism'' specifically to mean socialists who supported the politics and theories of Bolshevism

Bolshevism (derived from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Leninist and later Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined p ...

, Leninism

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

and later that of Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism () is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the History of communism, communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most communist gov ...

, although communist parties continued to describe themselves as socialists dedicated to socialism. According to ''The Oxford Handbook of Karl Marx'', "Marx used many terms to refer to a post-capitalist society—positive humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

, socialism, communism, realm of free individuality, free association of producers

Free association, also known as free association of producers, is a relationship among individuals where there is no private ownership of the means of production. A key feature of socialist economics, it has been defined differently by different s ...

, etc. He used these terms completely interchangeably. The notion that 'socialism' and 'communism' are distinct historical stages is alien to his work and only entered the lexicon of Marxism after his death".

In Christian Europe

The terms Christendom or Christian world commonly refer to the global Christian community, Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christen ...

, communists were believed to have adopted atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the Existence of God, existence of Deity, deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the ...

. In Protestant England, ''communism'' was too close to the Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

communion rite

Mass is the main Eucharistic liturgical service in many forms of Western Christianity. The term ''Mass'' is commonly used in the Catholic Church, Western Rite Orthodoxy, Old Catholicism, and Independent Catholicism. The term is also used in ma ...

, hence ''socialist'' was the preferred term. Engels wrote that in 1848, when ''The Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'' (), originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (), is a political pamphlet written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London in 1848. The ...

'' was published, socialism was respectable in Europe while communism was not. The Owenites

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative ...

in England and the Fourierists

Fourierism () is the systematic set of economic, political, and social beliefs first espoused by French intellectual Charles Fourier (1772–1837). It is based on a belief in the inevitability of communal associations of people who work and live t ...

in France were considered respectable socialists while working-class movements that "proclaimed the necessity of total social change" denoted themselves ''communists''. This branch of socialism produced the communist work of Étienne Cabet

Étienne Cabet (; January 1, 1788 – November 9, 1856) was a philosopher and utopian socialist who founded the Icarian movement. Cabet became the most popular socialist advocate of his day, with a special appeal to artisans who were being under ...

in France and Wilhelm Weitling

Wilhelm Christian Weitling (; October 5, 1808 – January 25, 1871) was a German tailor, inventor, radical political activist and one of the first theorists of communism. Weitling gained fame in Europe as a social theorist before he immigrated to ...

in Germany. British moral philosopher John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

discussed a form of economic socialism within free market. In later editions of his ''Principles of Political Economy

''Principles of Political Economy'' (1848) by John Stuart Mill was one of the most important economics or political economy textbooks of the mid-nineteenth century. It was revised until its seventh edition in 1871, shortly before Mill's death ...

'' (1848), Mill posited that "as far as economic theory was concerned, there is nothing in principle in economic theory that precludes an economic order based on socialist policies" and promoted substituting capitalist businesses with worker cooperative

A worker cooperative is a cooperative owned and Workers' self-management, self-managed by its workers. This control may mean a Company, firm where every worker-owner participates in decision-making in a democratic fashion, or it may refer to one ...

s. While democrats looked to the Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

as a democratic revolution

Democratic Revolution () was a Chilean centre-left to left-wing political party, founded in 2012 by some of the leaders of the 2011 Chilean student protests, most notably the current Deputy Giorgio Jackson, who is also the most popular public ...

which in the long run ensured liberty, equality, and fraternity, Marxists denounced it as a betrayal of working-class ideals by a bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

indifferent to the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian or a . Marxist ph ...

.

History

The history of socialism has its origins in theAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

and the 1789 French Revolution, along with the changes that brought, although it has precedents in earlier movements and ideas. ''The Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'' (), originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (), is a political pamphlet written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London in 1848. The ...

'' was written by Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Revolutions of 1848 The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

swept Europe, expressing what they termed ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Revolutions of 1848 The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

scientific socialism

Scientific socialism in Marxism is the application of historical materialism to the development of socialism, as not just a practical and achievable outcome of historical processes, but the only possible outcome. It contrasts with utopian social ...

. In the last third of the 19th century parties dedicated to Democratic socialism

Democratic socialism is a left-wing economic ideology, economic and political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and wor ...

arose in Europe, drawing mainly from Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

. For a duration of one week in December 1899, the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also known as the Labor Party or simply Labor, is the major Centre-left politics, centre-left List of political parties in Australia, political party in Australia and one of two Major party, major parties in Po ...

formed the first socialist government in the world when it was elected into power in the Colony of Queensland

The Colony of Queensland was a colony of the British Empire from 1859 to 1901, when it became a State in the federal Australia, Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901. At its greatest extent, the colony included the present-day Queensland, ...

with Premier Anderson Dawson

Andrew Dawson (16 July 1863 – 20 July 1910), usually known as Anderson Dawson, was an Australian politician and unionist who served as the 14th premier of Queensland for one week from the 1 to the 7 of December 1899. This short-lived premier ...

as its leader.

In the first half of the 20th century, the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and the communist parties of the Third International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internation ...

around the world, came to represent socialism in terms of the Soviet model of economic development and the creation of centrally planned economies

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, pa ...

directed by a state that owns all the means of production

In political philosophy, the means of production refers to the generally necessary assets and resources that enable a society to engage in production. While the exact resources encompassed in the term may vary, it is widely agreed to include the ...

, although other trends condemned what they saw as the lack of democracy. The establishment of the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

in 1949, saw socialism introduced. China experienced land redistribution and the Anti-Rightist Movement

The Anti-Rightist Campaign () in the People's Republic of China, which lasted from 1957 to roughly 1959, was a political campaign to purge alleged " Rightists" within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the country as a whole. The campaign wa ...

, followed by the disastrous Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward was an industrialization campaign within China from 1958 to 1962, led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Party Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to transform the country from an agrarian society into an indu ...

. In the UK, Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the Cabinet as a member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Minist ...

said that "socialism is what the Labour government does" whereas Aneurin Bevan

Aneurin "Nye" Bevan Privy Council (United Kingdom), PC (; 15 November 1897 – 6 July 1960) was a Welsh Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician, noted for spearheading the creation of the British National Health Service during his t ...

argued socialism requires that the "main streams of economic activity are brought under public direction", with an economic plan and workers' democracy. Some argued that capitalism had been abolished. Socialist governments established the mixed economy

A mixed economy is an economic system that includes both elements associated with capitalism, such as private businesses, and with socialism, such as nationalized government services.

More specifically, a mixed economy may be variously de ...

with partial nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

s and social welfare.

By 1968, the prolonged Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

gave rise to the New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

, socialists who tended to be critical of the Soviet Union and social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

. Anarcho-syndicalists

Anarcho-syndicalism is an anarchism, anarchist organisational model that centres trade unions as a vehicle for class conflict. Drawing from the theory of libertarian socialism and the practice of syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalism sees trade uni ...

and some elements of the New Left and others favoured decentralised

Decentralization or decentralisation is the process by which the activities of an organization, particularly those related to planning and decision-making, are distributed or delegated away from a central, authoritative location or group and gi ...

collective ownership

Collective ownership is the ownership of private property by all members of a group. The breadth or narrowness of the group can range from a whole society to a set of coworkers in a particular enterprise (such as one collective farm). In the la ...

in the form of cooperatives

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democr ...

or workers' councils

A workers' council, also called labour council, is a type of council in a workplace or a locality made up of workers or of temporary and instantly revocable delegates elected by the workers in a locality's workplaces. In such a system of poli ...

. In 1989, the Soviet Union saw the end of communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, marked by the Revolutions of 1989

The revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, were a revolutionary wave of liberal democracy movements that resulted in the collapse of most Communist state, Marxist–Leninist governments in the Eastern Bloc and other parts ...

across Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

, culminating in the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Socialists have adopted the causes of other social movements such as environmentalism

Environmentalism is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement about supporting life, habitats, and surroundings. While environmentalism focuses more on the environmental and nature-related aspects of green ideology and politics, ecolog ...

, feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

and progressivism

Progressivism is a Left-right political spectrum, left-leaning political philosophy and Reformism, reform political movement, movement that seeks to advance the human condition through social reform. Adherents hold that progressivism has unive ...

.

Early 21st century

In 1990, theSão Paulo Forum

São Paulo Forum (FSP), also known as the Foro de São Paulo, is a conference of left-wing political parties and organizations from the Americas, primarily Latin America and the Caribbean. It was launched by the Workers' Party () of Brazil in 19 ...

was launched by the Workers' Party (Brazil)

The Workers' Party (, PT) is a Centre-left politics, centre-left List of political parties in Brazil, political party in Brazil that is currently the country's ruling party. Some scholars classify its ideology in the 21st century as social demo ...

, linking left-wing socialist parties in Latin America. Its members were associated with the Pink tide

The pink tide (; ; ), or the turn to the left (; ; ), is a political wave and turn towards left-wing governments in Latin America throughout the 21st century. As a term, both phrases are used in political analysis in the news media and elsewhe ...

of left-wing governments on the continent in the early 21st century. Member parties ruling countries included the Front for Victory

The Front for Victory (, FPV) was a centre-left Peronist electoral alliance in Argentina, and is formally a faction of the Justicialist Party. Former presidents Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner were elected as representatives ...

in Argentina, the PAIS Alliance

The Revolutionary and Democratic Ethical Green Movement (, MOVER) was a centre to centre-right neoliberal political party in Ecuador. In 2016, it had 979,691 members. Until 2021 it was known as the PAIS Alliance (Proud and Sovereign Homeland) (P ...

in Ecuador, Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front

The Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (, abbreviated FMLN) is a Salvadoran political party and former guerrilla rebel group.

The FMLN was formed as an umbrella group on 10 October 1980, from five leftist guerrilla organizations; ...

in El Salvador, Peru Wins

Peru Wins (, GP) was a leftist electoral alliance in Peru formed for the 2011 general election. It was dominated by the Peruvian Nationalist Party and led by successful presidential candidate Ollanta Humala Tasso.

Constituent parties

*Peruvia ...

in Peru, and the United Socialist Party of Venezuela

The United Socialist Party of Venezuela (, PSUV, ) is a Socialism, socialist political party which has been the ruling party of Venezuela since 2007. It was formed from a merger of some of the political and social forces that support the Bolivar ...

, whose leader Hugo Chávez

Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías (; ; 28 July 1954 – 5 March 2013) was a Venezuelan politician, Bolivarian Revolution, revolutionary, and Officer (armed forces), military officer who served as the 52nd president of Venezuela from 1999 until De ...

initiated what he called "Socialism of the 21st century

Socialism of the 21st century (; ; ) is an interpretation of socialist principles first advocated by German sociologist and political analyst Heinz Dieterich and taken up by a number of Latin American leaders. Dieterich argued in 1996 that ...

".

Many mainstream democratic socialist and social democratic parties continued to drift right-wards. On the right of the socialist movement, the Progressive Alliance

The Progressive Alliance (PA) is a political international of progressive and social democratic political parties and organisations founded on 22 May 2013 in Leipzig, Germany. The alliance was formed as an alternative to the existing Socia ...

was founded in 2013 by current or former members of the Socialist International

The Socialist International (SI) is a political international or worldwide organisation of political parties which seek to establish democratic socialism, consisting mostly of Social democracy, social democratic political parties and Labour mov ...

. The organisation states the aim of becoming the global network of "the progressive, democratic, social-democratic

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, socia ...

, socialist and labour movement

The labour movement is the collective organisation of working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It can be considere ...

". Mainstream social democratic and socialist parties are also networked in Europe in the Party of European Socialists

The Party of European Socialists (PES) is a Social democracy, social democratic European political party.

The PES comprises national-level political parties from all the European Economic Area, European economic area states (EEA) plus the Unit ...

formed in 1992. Many of these parties lost large parts of their electoral base in the early 21st century. This phenomenon is known as Pasokification

Pasokification is the decline of centre-left, social-democratic political parties in European and other Western countries during the 2010s, often accompanied by the rise of nationalist, left-wing and right-wing populist alternatives. In Europe, ...

from the Greek party PASOK

The Panhellenic Socialist Movement (, ), known mostly by its acronym PASOK (; , ), is a social democracy, social-democratic List of political parties in Greece, political party in Greece. Until 2012 it was Two-party system, one of the two major ...

, which saw a declining share of the vote in national elections—from 43.9% in 2009 to 13.2% in May 2012, to 12.3% in June 2012 and 4.7% in 2015—due to its poor handling of the Greek government-debt crisis

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

** Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kn ...

and implementation of harsh austerity

In economic policy, austerity is a set of Political economy, political-economic policies that aim to reduce government budget deficits through Government spending, spending cuts, tax increases, or a combination of both. There are three prim ...

measures.

In Europe, the share of votes for such socialist parties was at its 70-year lowest in 2015. For example, the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

, after winning the 2012 French presidential election

Presidential elections in France, Presidential elections were held in France on 22 April 2012 (or 21 April in some overseas departments and territories), with a second round Two-round system, run-off held on 6 May (or 5 May for those same territ ...

, rapidly lost its vote share, the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany ( , SPD ) is a social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany. Saskia Esken has been the party's leader since the 2019 leadership election together w ...

's fortunes declined rapidly from 2005 to 2019, and outside Europe the Israeli Labor Party

The Israeli Labor Party (), commonly known in Israel as HaAvoda (), was a Social democracy, social democratic political party in Israel. The party was established in 1968 by a merger of Mapai, Ahdut HaAvoda and Rafi (political party), Rafi. Unt ...

fell from being the dominant force in Israeli politics to 4.43% of the vote in the April 2019 Israeli legislative election

Early legislative elections were held in Israel on 9 April 2019 to elect the 120 members of the 21st Knesset. Elections had been due in November 2019, but were brought forward following a dispute between members of the current government over a ...

, and the Peruvian Aprista Party

The Peruvian Aprista Party (, PAP) () is a Peruvian social-democratic political party and a member of the Socialist International. The party was founded as the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (, APRA) by Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre ...

went from ruling party in 2011 to a minor party. The decline of these mainstream parties opened space for more radical and populist left parties in some countries, such as Spain's Podemos, Greece's Syriza

The Coalition of the Radical Left – Progressive Alliance (), best known by the syllabic abbreviation SYRIZA ( ; ; a pun on the Greek adverb , meaning "from the roots" or "radically"), is a Centre-left politics, centre-left to Left-wing politi ...

(in government, 2015–19), Germany's Die Linke

Die Linke (; ), also known as the Left Party ( ), is a democratic socialist political party in Germany. The party was founded in 2007 as the result of the merger of the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) and Labour and Social Justice – The ...

, and France's La France Insoumise

La France Insoumise (LFI or FI; , ) is a left-wing political party in France. It was launched in 2016 by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, then a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) and former co-president of the Left Party (PG). It aims to implement th ...

. In other countries, left-wing revivals have taken place within mainstream democratic socialist and centrist parties, as with Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who has been Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) for Islington North (UK Parliament constituency), Islington North since 1983. Now an Independent ...

in the United Kingdom and Bernie Sanders

Bernard Sanders (born September8, 1941) is an American politician and activist who is the Seniority in the United States Senate, senior United States Senate, United States senator from the state of Vermont. He is the longest-serving independ ...

in the United States. Few of these radical left parties have won national government in Europe, while some more mainstream socialist parties have managed to, such as Portugal's Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

.

Bhaskar Sunkara

Bhaskar Sunkara (born June 1989) is an American political writer. He is the founding editor of ''Jacobin,'' the president of ''The Nation,'' and publisher of ''Catalyst: A Journal of Theory and Strategy''. He is a former vice-chair of the Democr ...

, the founding editor of the American socialist magazine ''Jacobin'', argued that the appeal of socialism persists due to the inequality and "tremendous suffering" under current global capitalism, the use of wage labor "which rests on the exploitation and domination of humans by other humans," and ecological crises, such as climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

. In contrast, Mark J. Perry of the conservative American Enterprise Institute

The American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, known simply as the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), is a center-right think tank based in Washington, D.C., that researches government, politics, economics, and social welfare ...

(AEI) argued that despite socialism's resurgence, it is still "a flawed system based on completely faulty principles that aren't consistent with human behavior and can't nurture the human spirit.", adding that "While it promised prosperity, equality, and security, it delivered poverty, misery, and tyranny." Some in the scientific community have suggested that a contemporary radical response to social and ecological problems could be seen in the emergence of movements associated with degrowth

Degrowth is an Academic research, academic and social Social movement, movement critical of the concept of economic growth, growth in Real gross domestic product, gross domestic product as a measure of Human development (economics), human and econ ...

, eco-socialism

Eco-socialism (also known as green socialism, socialist ecology, ecological materialism, or revolutionary ecology) is an ideology merging aspects of socialism with that of green politics, ecology and alter-globalization or anti-globalization. E ...

and eco-anarchism

Green anarchism, also known as ecological anarchism or eco-anarchism, is an anarchist school of thought that focuses on ecology and environmental issues. It is an anti-capitalism, anti-capitalist and anti-authoritarianism, anti-authoritarian form ...

.

Social and political theory

Early socialist thought took influences from a diverse range of philosophies such as civicrepublicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

, Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the Epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to ot ...

, romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

, forms of materialism

Materialism is a form of monism, philosophical monism according to which matter is the fundamental Substance theory, substance in nature, and all things, including mind, mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. Acco ...

, Christianity (both Catholic and Protestant), natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

and natural rights theory, utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

and liberal political economy. Another philosophical basis for a great deal of early socialism was the emergence of positivism

Positivism is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positivemeaning '' a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. Gerber, ''Soci ...

during the European Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

. Positivism held that both the natural and social worlds could be understood through scientific knowledge and be analysed using scientific methods.

The fundamental objective of socialism is to attain an advanced level of material production and therefore greater productivity, efficiency and rationality as compared to capitalism and all previous systems, under the view that an expansion of human productive capability is the basis for the extension of freedom and equality in society. Many forms of socialist theory hold that human behaviour is largely shaped by the social environment. In particular, socialism holds that social

The fundamental objective of socialism is to attain an advanced level of material production and therefore greater productivity, efficiency and rationality as compared to capitalism and all previous systems, under the view that an expansion of human productive capability is the basis for the extension of freedom and equality in society. Many forms of socialist theory hold that human behaviour is largely shaped by the social environment. In particular, socialism holds that social mores

Mores (, sometimes ; , plural form of singular , meaning "manner, custom, usage, or habit") are social norms that are widely observed within a particular society or culture. Mores determine what is considered morally acceptable or unacceptable ...

, values, cultural traits and economic practices are social creations and not the result of an immutable natural law. The object of their critique is thus not human avarice or human consciousness, but the material conditions and man-made social systems (i.e. the economic structure of society) which give rise to observed social problems and inefficiencies. Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, often considered to be the father of analytic philosophy, identified as a socialist. Russell opposed the class struggle aspects of Marxism, viewing socialism solely as an adjustment of economic relations to accommodate modern machine production to benefit all of humanity through the progressive reduction of necessary work time.

Socialists view creativity as an essential aspect of human nature and define freedom as a state of being where individuals are able to express their creativity unhindered by constraints of both material scarcity and coercive social institutions. The socialist concept of individuality is intertwined with the concept of individual creative expression. Karl Marx believed that expansion of the productive forces and technology was the basis for the expansion of human freedom and that socialism, being a system that is consistent with modern developments in technology, would enable the flourishing of "free individualities" through the progressive reduction of necessary labour time. The reduction of necessary labour time to a minimum would grant individuals the opportunity to pursue the development of their true individuality and creativity.

Criticism of capitalism

Socialists argue that the accumulation of capital generates waste throughexternalities

In economics, an externality is an indirect cost (external cost) or indirect benefit (external benefit) to an uninvolved third party that arises as an effect of another party's (or parties') activity. Externalities can be considered as unpriced ...

that require costly corrective regulatory measures. They also point out that this process generates wasteful industries and practices that exist only to generate sufficient demand for products such as high-pressure advertisement to be sold at a profit, thereby creating rather than satisfying economic demand. Socialists argue that capitalism consists of irrational activity, such as the purchasing of commodities only to sell at a later time when their price appreciates, rather than for consumption, even if the commodity cannot be sold at a profit to individuals in need and therefore a crucial criticism often made by socialists is that "making money", or accumulation of capital, does not correspond to the satisfaction of demand (the production of use-value

Use value () or value in use is a concept in classical political economy and Marxist economics. It refers to the tangible features of a Commodity (Marxism), commodity (a tradeable object) which can satisfy some human requirement, want or need, o ...

s). The fundamental criterion for economic activity in capitalism is the accumulation of capital for reinvestment in production, but this spurs the development of new, non-productive industries that do not produce use-value and only exist to keep the accumulation process afloat (otherwise the system goes into crisis), such as the spread of the financial industry

Financial services are service (economics), economic services tied to finance provided by financial institutions. Financial services encompass a broad range of tertiary sector of the economy, service sector activities, especially as concerns finan ...

, contributing to the formation of economic bubbles. Such accumulation and reinvestment, when it demands a constant rate of profit, causes problems if the earnings in the rest of society do not increase in proportion.

Socialists view private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental Capacity (law), legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from Collective ownership ...

relations as limiting the potential of productive forces

Productive forces, productive powers, or forces of production ( German: ''Produktivkräfte'') is a central idea in Marxism and historical materialism.

In Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' own critique of political economy, it refers to the combin ...

in the economy. According to socialists, private property becomes obsolete when it concentrates into centralised, socialised institutions based on private appropriation of revenue''—''but based on cooperative work and internal planning in allocation of inputs—until the role of the capitalist becomes redundant. With no need for capital accumulation

Capital accumulation is the dynamic that motivates the pursuit of profit, involving the investment of money or any financial asset with the goal of increasing the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the form ...

and a class of owners, private property in the means of production is perceived as being an outdated form of economic organisation that should be replaced by a free association of individuals based on public or common ownership

Common ownership refers to holding the assets of an organization, enterprise, or community indivisibly rather than in the names of the individual members or groups of members as common property. Forms of common ownership exist in every economi ...

of these socialised assets. Private ownership imposes constraints on planning, leading to uncoordinated economic decisions that result in business fluctuations, unemployment and a tremendous waste of material resources during crisis of overproduction

In economics, overproduction, oversupply, excess of supply, or glut refers to excess of supply over demand of products being offered to the market. This leads to lower prices and/or unsold goods along with the possibility of unemployment.

T ...

.

Excessive disparities in income distribution lead to social instability and require costly corrective measures in the form of redistributive taxation, which incurs heavy administrative costs while weakening the incentive to work, inviting dishonesty and increasing the likelihood of tax evasion while (the corrective measures) reduce the overall efficiency of the market economy. These corrective policies limit the incentive system of the market by providing things such as minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. List of countries by minimum wage, Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation b ...

s, unemployment insurance

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is the proportion of people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work du ...

, taxing profits and reducing the reserve army of labour

Reserve army of labour is a concept in Karl Marx's critique of political economy. It refers to the unemployed and underemployed in capitalist society. It is synonymous with "industrial reserve army" or "relative surplus population", except tha ...

, resulting in reduced incentives for capitalists to invest in more production. In essence, social welfare policies cripple capitalism and its incentive system and are thus unsustainable in the long run. Marxists argue that the establishment of a socialist mode of production

The socialist mode of production, also known as socialism or communism, is a specific historical phase of economic development and its corresponding set of social relations that emerge from capitalism in the schema of historical materialism wit ...

is the only way to overcome these deficiencies. Socialists and specifically Marxian socialists argue that the inherent conflict of interests between the working class and capital prevent optimal use of available human resources and leads to contradictory interest groups (labour and business) striving to influence the state to intervene in the economy in their favour at the expense of overall economic efficiency. Early socialists (utopian socialists

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is oft ...

and Ricardian socialists

Ricardian socialism is a branch of classical economic thought based upon the work of the economist David Ricardo (1772–1823). Despite Ricardo being a capitalist economist, the term is used to describe economists in the 1820s and 1830s who dev ...

) criticised capitalism for concentrating power

Power may refer to:

Common meanings

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power, a type of energy

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

Math ...

and wealth within a small segment of society. In addition, they complained that capitalism does not use available technology and resources to their maximum potential in the interests of the public.

Marxism

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.productive forces Productive forces, productive powers, or forces of production ( German: ''Produktivkräfte'') is a central idea in Marxism and historical materialism. In Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' own critique of political economy, it refers to the combin ...