Skolt Sámi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Skolt Sámi (, , ; or , , ) is a

On Finnish territory Skolt Sámi was spoken in four villages before the Second World War. In

On Finnish territory Skolt Sámi was spoken in four villages before the Second World War. In

The Children's TV series Binnabánnaš in Skolt Sámi

Nuõrttsää′mǩiõl alfabee′tt – koltankieliset aakkoset

�Skolt Saami alphabet by the Finnish Saami Parliament

Say it in Saami

Yle's colloquial Northern Saami-Inari Saami-Skolt Saami-English phrasebook online

Surrey Morphology Group – Skolt Saami

* Skolt Saami verb paradigm visualisations. Feist, Timothy, Matthew Baerman, Greville G. Corbett & Erich Round. 2019. Surrey Lexical Splits Visualisations (Skolt Saami). University of Surrey. https://lexicalsplits.surrey.ac.uk/skoltsaami.html

A very small Skolt Sámi – English vocabulary (< 500 words)

Skolt Sámi - Finnish/English/Russian dictionary

(robust finite-state, open-source)

Northern Sámi – Inari Sámi – Skolt Sámi – English dictionary

(requires a password nowadays)

Names of birds

found in

Sää′mjie′llem

Sámi Museum site on the history of the Skolt Sámi in Finland

A number of linguistic articles on Skolt Sámi.

Erkki Lumisalmi talks in Skolt Sámiarchive

(mp3)

The Palatalization Mark in Skolt Sámi.

Ranskalaisen tutkimusmatkailijan arkistot palautumassa kolttasaamelaisille – aineisto sisältää satoja dioja ja valokuvia (The French explorer's archives are being restored to the Koltsa Sámi - the material contains hundreds of slides and photographs)

Maailmankuulu tutkija tarkkaili kolttasaamelaisia 50 vuotta sitten ja jätti nyt ainutlaatuisen perinnön (A world-renowned researcher observed the Koltsa Sámi 50 years ago and now left a unique legacy)

Sámi language

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise ...

that is spoken by the Skolts

The Skolt Sámi or Skolts are a Sámi people, Sámi ethnic group. They currently live in and around the villages of Sevettijärvi, Keväjärvi, Nellim in the municipality of Inari, Finland, Inari, at several places in the Murmansk Oblast and in t ...

, with approximately 300 speakers in Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, mainly in Sevettijärvi

Sevettijärvi (Skolt Sámi: Čeʹvetjäuʹrr, and ) is a village in the municipality of Inari, Finland approximately north of downtown Inari. Neiden in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

and approximately 20–30 speakers of the (Notozero) dialect in an area surrounding Lake Notozero

The Verkhnetulomskoye Reservoir () is a large reservoir on the Kola Peninsula, Murmansk Oblast, Russia. It impounds the river Tuloma. It was constructed in 1964-1965, and has an area of 745 km².Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. In Norway, there are fewer than 15 that can speak Skolt Sámi (as of 2023);Ole Magnus Rapp. 2023-11-06. Klassekampen

(Lit. translation: ''"The Class Struggle"'') is a Norwegian daily newspaper in print and online. Its tagline is "The daily newspaper of the Left". The paper's net circulation was 33,265 in 2022, and it has around 111,000 daily readers on paper ...

. P.24 furthermore, the language is largely spoken in the Neiden area. It is written using a modified Roman orthography

An orthography is a set of convention (norm), conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, punctuation, Word#Word boundaries, word boundaries, capitalization, hyphenation, and Emphasis (typography), emphasis.

Most national ...

which was made official in 1973.

The term ''Skolt'' was coined by representatives of the majority culture and has negative connotation which can be compared to the term ''Lapp''. Nevertheless, it is used in cultural and linguistic studies. In 2024, Venke Törmänen, the leader of an NGO called Norrõs Skoltesamene, wrote in Ságat, a Sámi newspaper, saying that the term "Eastern Sámi" ("østsame" in Norwegian) should not be used to refer to the Skolt Sámi.

History

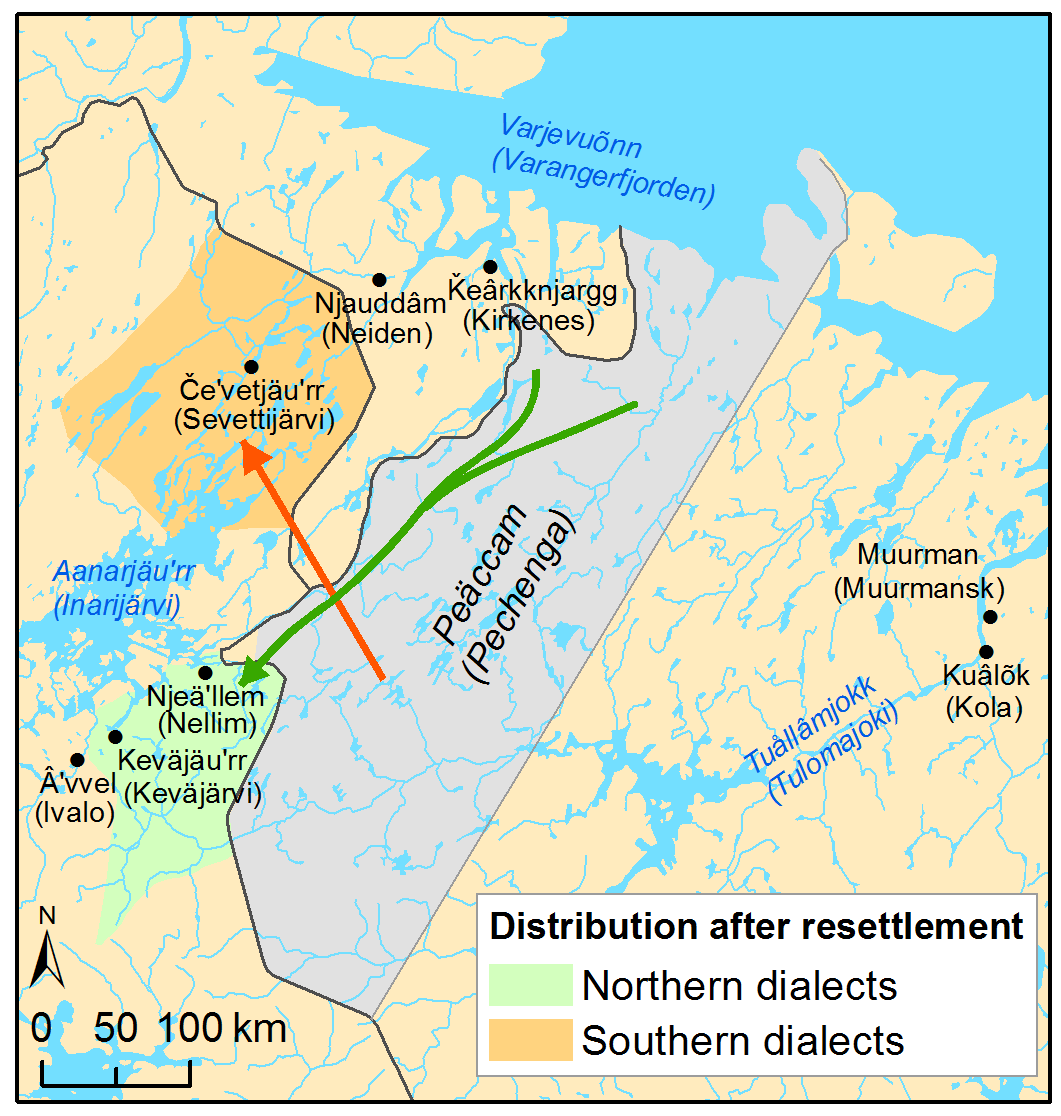

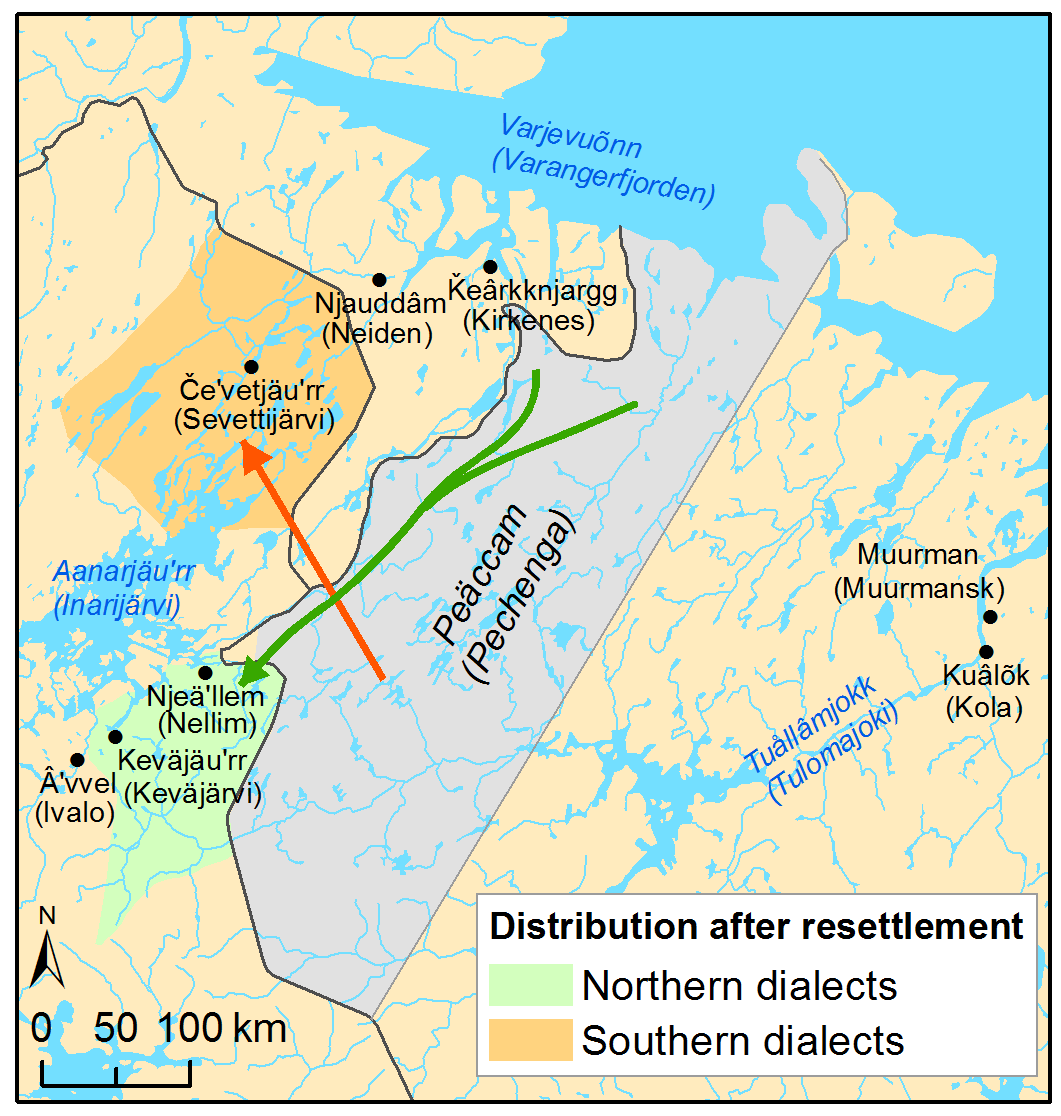

On Finnish territory Skolt Sámi was spoken in four villages before the Second World War. In

On Finnish territory Skolt Sámi was spoken in four villages before the Second World War. In Petsamo Petsamo may refer to:

* Petsamo Province, a province of Finland from 1921 to 1922

* Petsamo, Tampere, a district in Tampere, Finland

* Pechengsky District

Pechengsky District (; ; ; ; ) is an administrative district (raion), one of the six in Mur ...

, Skolt Sámi was spoken in Suonikylä and the village of Petsamo. This area was ceded to Russia in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, and the Skolts were evacuated to the villages of Inari, Sevettijärvi

Sevettijärvi (Skolt Sámi: Čeʹvetjäuʹrr, and ) is a village in the municipality of Inari, Finland approximately north of downtown Inari. Neiden in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

and Nellim

Nellim ( or '; ; ) is a village on the shore of Lake Inari in Inari, Finland that has three distinctly different cultures: Finns, the Inari Sámi and the Skolt Sámi

Skolt Sámi (, , ; or , , ) is a Sámi languages, Sámi language that is ...

in the Inari municipality.

On the Russian (then Soviet) side the dialect was spoken in the now defunct Sámi settlements of Motovsky, Songelsky, Notozero (hence its Russian name – the ''Notozersky'' dialect). Some speakers still may live in the villages of Tuloma and Lovozero.

In Norwegian territory, Skolt Sámi was spoken in the Sør-Varanger area with a cultural centre in the village of Neiden. The language is not spoken as mother tongue

A first language (L1), native language, native tongue, or mother tongue is the first language a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' or ''mother tongue'' refers ...

anymore in Norway.

Status

Finland

In Finland, Skolt Sámi is spoken by approximately 300 or 400 people. According to Finland's Sámi Language Act (1086/2003), Skolt Sámi is one of the three Sámi languages that the Sámi can use when conducting official business in Lapland. It is an official language in the municipality of Inari, and elementary schools there offer courses in the language, both for native speakers and for students learning it as a foreign language. Only a small number of youths learn the language and continue to use it actively. Skolt Sámi is thus a seriouslyendangered language

An endangered language or moribund language is a language that is at risk of disappearing as its speakers die out or shift to speaking other languages. Language loss occurs when the language has no more native speakers and becomes a " dead langua ...

, even more seriously than Inari Sámi Inari Sámi may refer to:

*Inari Sámi language

*Inari Sámi people

Inari or Aanaar Sámi (Inari Sámi language, Inari Sámi: ''anarâšah'') are a group of Sámi people who inhabit the area around Lake Inari, Finland. They speak the Inari Sámi l ...

, which has a nearly equal number of speakers and is even spoken in the same municipality

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having municipal corporation, corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality' ...

. In addition, there are a lot of Skolts living outside of this area, particularly in the capital region.

Use

Media

From 1978 to 1986, the Skolts had a quarterly called published in their own language. Since 2013, a new magazine called Tuõddri pee′rel has been published once a year. The Finnish news program featured a Skolt Sámi speaking newsreader for the first time on August 26, 2016. Otherwise Yle presents individual news stories in Skolt Sámi every now and then. In addition, there have been various TV programs in Skolt Sámi on YLE such as the children's TV series .Religion

The first book published in Skolt Sámi was anEastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

prayer book (, ''Prayerbook for the Orthodox'') in 1983. Translation of the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John () is the fourth of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "Book of Signs, signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the ...

was published () in 1988 and Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom

The Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom is the most celebrated divine liturgy in the Byzantine Rite. It is named after its core part, the anaphora attributed to Saint John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople in the 5th century.

History

The ...

(, ''Liturgy of our Holy Father John Chrysostom'') was published in 2002 Skolt Sámi is used together with Finnish in worship of the Lappi Orthodox Parish () at churches of Ivalo

Ivalo (, , , ) is a village in the municipality of Inari, Lapland, Finland, located on the Ivalo River south of Lake Inari in the Arctic Circle. It has a population of 3,998 and a small airport, located 11 kilometres (7 mi) southwest from Iv ...

, Sevettijärvi

Sevettijärvi (Skolt Sámi: Čeʹvetjäuʹrr, and ) is a village in the municipality of Inari, Finland approximately north of downtown Inari. Neiden in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

and Nellim

Nellim ( or '; ; ) is a village on the shore of Lake Inari in Inari, Finland that has three distinctly different cultures: Finns, the Inari Sámi and the Skolt Sámi

Skolt Sámi (, , ; or , , ) is a Sámi languages, Sámi language that is ...

.

Music

LikeInari Sámi Inari Sámi may refer to:

*Inari Sámi language

*Inari Sámi people

Inari or Aanaar Sámi (Inari Sámi language, Inari Sámi: ''anarâšah'') are a group of Sámi people who inhabit the area around Lake Inari, Finland. They speak the Inari Sámi l ...

, Skolt Sámi has recently borne witness to a new phenomenon, namely it is being used in rock songs sung by Tiina Sanila-Aikio, who has published two full-length CDs in Skolt Sámi to date.

Education

In 1993,language nest

A language nest is an immersion-based approach to language revitalization in early-childhood education. Language nests originated in New Zealand in the 1980s, as a part of the Māori-language revival in that country. The term "language nest" is ...

programs for children younger than 7 were created. For quite some time these programs received intermittent funding, resulting in some children being taught Skolt Sámi, while others were not. In spite of all the issues these programs faced, they were crucial in creating the youngest generations of Skolt Sámi speakers. In recent years, these programs have been reinstated.

In addition, 2005 was the first time that it was possible to use Skolt Sámi in a Finnish matriculation exam, albeit as a foreign language. In 2012, Ville-Riiko Fofonoff () was the first person to use Skolt Sámi for the mother tongue portion of the exam; for this, he won the Skolt of the Year Award the same year.

Writing system

In 1973, an official, standardized orthography for Skolt Sámi was introduced based on the dialect. Since then, it has been widely accepted with a few small modifications. The Skolt Sámi orthography uses theISO basic Latin alphabet

The ISO basic Latin alphabet is an international standard (beginning with ISO/IEC 646) for a Latin-script alphabet that consists of two sets (uppercase and lowercase) of 26 letters, codified in various national and international standards and u ...

with the addition of a few special characters:

Notes:

* The letters Q/q, W/w, X/x, Y/y and Ö/ö are also used, although only in foreign words or loans. As in Finnish and Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

Ü/ü is alphabetized as ''y'', not ''u''.

* No difference is made in the standard orthography between and . In dictionaries, grammars and other reference works, the letter is used to indicate .

* The diagraphs and indicate the consonants and respectively.

Additional marks are used in writing Skolt Sámi words:

* A prime symbol

The prime symbol , double prime symbol , triple prime symbol , and quadruple prime symbol are used to designate units and for other purposes in mathematics, science, linguistics and music.

Although the characters differ little in appearance fr ...

′ (U+02B9 MODIFIER LETTER PRIME) is added after the vowel of a syllable to indicate suprasegmental palatalization. Occasionally a standalone acute accent ´ or ˊ (U+00B4 ACUTE ACCENT or U+02CA MODIFIER LETTER ACUTE ACCENT) is used, but this is not correct.

* An apostrophe

The apostrophe (, ) is a punctuation mark, and sometimes a diacritical mark, in languages that use the Latin alphabet and some other alphabets. In English, the apostrophe is used for two basic purposes:

* The marking of the omission of one o ...

ʼ (U+02BC MODIFIER LETTER APOSTROPHE) is used in the combinations and to indicate that these are two separate sounds, not a single sound. It is also placed between identical consonants to indicate that they belong to separate prosodic feet, and should not be combined into a geminate. It distinguishes e.g. "to set free" from its causative "to cause to set free".

* A hyphen – is used in compound words when there are two identical consonants at the juncture between the parts of the compound, e.g. "mobile phone".

* A vertical line ˈ (U+02C8 MODIFIER LETTER VERTICAL LINE), typewriter apostrophe

The apostrophe (, ) is a punctuation mark, and sometimes a diacritical mark, in languages that use the Latin alphabet and some other alphabets. In English, the apostrophe is used for two basic purposes:

* The marking of the omission of one o ...

or other similar mark indicates that a geminate consonant is long, and the preceding diphthong is short. It is placed between a pair of identical consonants which are always preceded by a diphthong. This mark is not used in normal Skolt Sámi writing, but it appears in dictionaries, grammars and other reference works.

Phonology

Special features of this Sámi language include a highly complex vowel system and a suprasegmental contrast of palatalized vs. non-palatalized stress groups; palatalized stress groups are indicated by a "softener mark", represented by the modifier letter prime (′).Vowels

The system of vowel phonemes is as follows: Notes: * The open-mid front unrounded vowel // occurs only in non-palatalized words. * The vowels // and // occur in some loan words. Skolt Sámi hasvowel length

In linguistics, vowel length is the perceived or actual length (phonetics), duration of a vowel sound when pronounced. Vowels perceived as shorter are often called short vowels and those perceived as longer called long vowels.

On one hand, many ...

, but it co-occurs with contrasts in length of the following consonant(s). For example, ‘vessel’ vs. ‘vessels’.

The vowels can combine to form twelve opening diphthong

A diphthong ( ), also known as a gliding vowel or a vowel glide, is a combination of two adjacent vowel sounds within the same syllable. Technically, a diphthong is a vowel with two different targets: that is, the tongue (and/or other parts of ...

s:

Like the monophthongs, all diphthongs can be short or long, but this is not indicated in spelling. Short diphthongs are distinguished from long ones by both length and stress placement: short diphthongs have a stressed second component, whereas long diphthongs have stress on the first component.

Diphthongs may also have two variants depending on whether they occur in a plain or palatalized environment. This has a clearer effect with diphthongs whose second element is back or central. Certain inflectional forms, including the addition of the palatalizing suprasegmental, also trigger a change in diphthong quality.

Consonants

The inventory of consonant phonemes is the following: * Unvoiced stops and affricates are pronounced preaspirated after vowels andsonorant

In phonetics and phonology, a sonorant or resonant is a speech sound that is produced with continuous, non-turbulent airflow in the vocal tract; these are the manners of articulation that are most often voiced in the world's languages. Vowels a ...

consonants.

* Older speakers realize the palatal affricates as plosives .

* In younger speakers, merges into , into , and into .

* Younger speakers may also lenite into [], and into .

* The voiceless velar fricative /x/ has many allophones. It is realized as [h] in word-initial or stress group-initial environments, and as [] in intervocalic environments. Within palatalized stress groups, /x/ is realized as [].

* /f/ appears only in loanwords, but is nonetheless quite common.

* Voiced plosives , , and are not fully voiced, realized as [b̥], [d̥], and [g̥].

* Voiced fricatives /v/, /ð/, /z/, /ʒ/, /ʝ/, and /ɣ/ are only weakly voiced, and in unstressed syllables may be fully unvoiced.

Consonants may be phonemically short or long (geminate

In phonetics and phonology, gemination (; from Latin 'doubling', itself from '' gemini'' 'twins'), or consonant lengthening, is an articulation of a consonant for a longer period of time than that of a singleton consonant. It is distinct from ...

) both word-medially or word-finally; both are exceedingly common. Similarly to other Sámic languages, there exists a three-way contrast between weak, strong, and overlong consonants (In some reference works, these are referred to as weak, strong, and strong+, or transcribed as C, Cː, and CːC). Overlong consonants do not occur word-finally. Long and short consonants also contrast in consonant clusters, cf. 'to touch' : 'I touch'. A short period of voicelessness or ''h'', known as preaspiration, before geminate consonants is observed, much as in Icelandic, but this is not marked orthographically, e.g. 'to the river' is pronounced .

Suprasegmentals

There is one phonemicsuprasegmental

In linguistics, prosody () is the study of elements of speech, including intonation, stress, rhythm and loudness, that occur simultaneously with individual phonetic segments: vowels and consonants. Often, prosody specifically refers to such ele ...

, the palatalizing suprasegmental that affects the pronunciation of an entire syllable. In written language the palatalizing suprasegmental is indicated with a free-standing acute accent between a stressed vowel and the following consonant, as follows:

:: a̘ːrʲːe̥ 'mountain, hill' (suprasegmental palatalization present)

:: aːrːḁ'trip' (no suprasegmental palatalization)

The suprasegmental palatalization has three distinct phonetic effects:

* The stressed vowel is pronounced as slightly more fronted in palatalized syllables than in non-palatalized ones.

* When the palatalizing suprasegmental is present, the following consonant or consonant cluster is pronounced as weakly palatalized. Suprasegmental palatalization is independent of segmental palatals: inherently palatal consonants (i.e. consonants with palatal place of articulation

In articulatory phonetics, the place of articulation (also point of articulation) of a consonant is an approximate location along the vocal tract where its production occurs. It is a point where a constriction is made between an active and a pa ...

) such as the palatal glide , the palatal nasal (spelled ) and the palatal lateral approximant (spelled ) can occur both in non-palatalized and suprasegmentally palatalized syllables.

* If the word form is monosyllabic and ends in a consonant, a non-phonemic weakly voiced or unvoiced vowel is pronounced after the final consonant. This vowel is ''e''-colored if suprasegmental palatalization is present, but ''a''-colored if not.

Stress

Skolt Sámi has four different levels of stress for words: * Primary stress * Secondary stress * Tertiary stress * Zero stress The first syllable of any word is always the primary stressed syllable in Skolt Sámi as Skolt is a fixed-stress language. In words with two or more syllables, the final syllable is quite lightly stressed (tertiary stress) and the remaining syllable, if any, are stressed more heavily than the final syllable, but less than the first syllable (secondary stress). Using theabessive

In linguistics, abessive (abbreviated or ), caritive (abbreviated ) and privative (abbreviated ) is the grammatical case expressing the lack or absence of the marked noun. In English, the corresponding function is expressed by the preposition '' ...

and the comitative

In grammar, the comitative case (abbreviated ) is a grammatical case that denotes accompaniment. In English, the preposition "with", in the sense of "in company with" or "together with", plays a substantially similar role. Other uses of "with", l ...

singular

Singular may refer to:

* Singular, the grammatical number that denotes a unit quantity, as opposed to the plural and other forms

* Singular or sounder, a group of boar, see List of animal names

* Singular (band), a Thai jazz pop duo

*'' Singula ...

in a word appears to disrupt this system, however, in words of more than one syllable. The suffix, as can be expected, has tertiary stress, but the penultimate syllable also has tertiary stress, even though it would be expected to have secondary stress.

Zero stress can be said to be a feature of conjunctions, postpositions

Adpositions are a class of words used to express spatial or temporal relations (''in, under, towards, behind, ago'', etc.) or mark various semantic roles (''of, for''). The most common adpositions are prepositions (which precede their complemen ...

, particles

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscle in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

and monosyllabic pronouns.

Morphophonology

As in other Sámi and Finnic languages, Skolt Sámi has a system ofconsonant gradation

Consonant gradation is a type of consonant mutation (mostly lenition but also assimilation) found in some Uralic languages, more specifically in the Finnic, Samic and Samoyedic branches. It originally arose as an allophonic alternation ...

. In its origins, consonants occurring in the middle of words would change when they occurred in open vs closed syllables. As the language continued to undergo sound changes, some of the phonetic motivation for those changes have become obscure.

Qualitative gradation

In this subsystem, a consonant changes place of articulation, voicing or manner, and sometimes duration.Grammar

Skolt Sámi is asynthetic

Synthetic may refer to:

Science

* Synthetic biology

* Synthetic chemical or compound, produced by the process of chemical synthesis

* Synthetic elements, chemical elements that are not naturally found on Earth and therefore have to be created in ...

, highly inflected

In linguistic Morphology (linguistics), morphology, inflection (less commonly, inflexion) is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical category, grammatical categories such as grammatical tense, ...

language that shares many grammatical features with the other Uralic languages

The Uralic languages ( ), sometimes called the Uralian languages ( ), are spoken predominantly in Europe and North Asia. The Uralic languages with the most native speakers are Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian. Other languages with speakers ab ...

. However, Skolt Sámi is not a typical agglutinative language

An agglutinative language is a type of language that primarily forms words by stringing together morphemes (word parts)—each typically representing a single grammatical meaning—without significant modification to their forms ( agglutinations) ...

like many of the other Uralic languages are, as it has developed considerably into the direction of a fusional language

Fusional languages or inflected languages are a type of synthetic language, distinguished from agglutinative languages by their tendency to use single inflectional morphemes to denote multiple grammatical, syntactic, or semantic features.

For ...

, much like Estonian

Estonian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Estonia, a country in the Baltic region in northern Europe

* Estonians, people from Estonia, or of Estonian descent

* Estonian language

* Estonian cuisine

* Estonian culture

See also ...

. Therefore, cases and other grammatical features are also marked by modifications to the root and not just marked with suffixes. Many of the suffixes in Skolt Sámi are portmanteau morphemes that express several grammatical features at a time.

Umlaut

Umlaut is a pervasive phenomenon in Skolt Sámi, whereby the vowel in the second syllable affects the quality of the vowel in the first. The presence or absence of palatalisation can also be considered an umlaut effect, since it is also conditioned by the second-syllable vowel, although it affects the entire syllable rather than the vowel alone. Umlaut is complicated by the fact that many of the second-syllable vowels have disappeared in Skolt Sámi, leaving the umlaut effects as their only trace. The following table lists the Skolt Sámi outcomes of the Proto-Samic first-syllable vowel, for each second-syllable vowel. Some notes: * ''iẹ′'' and ''uẹ′'' appear before a quantity 2 consonant, ''eä′'' and ''uä′'' otherwise. As can be seen, palatalisation is present before original second-syllable ''*ē'' and ''*i'', and absent otherwise. Where they survive in Skolt Sámi, both appear as ''e'', so only the umlaut effect can distinguish them. The original short vowels ''*ë'', ''*u'' and ''*i'' have a general raising and backing effect on the preceding vowel, while the effect of original ''*ā'' and ''*ō'' is lowering. Original ''*ē'' is fronting (palatalising) without having an effect on height.Nouns

Cases

Skolt Sámi has 9 cases in the singular (7 of which also have a plural form), although the genitive and accusative are often the same. The following table shows the inflection of ('rotten snag') with the singlemorpheme

A morpheme is any of the smallest meaningful constituents within a linguistic expression and particularly within a word. Many words are themselves standalone morphemes, while other words contain multiple morphemes; in linguistic terminology, this ...

s marking noun stem, number, and case separated by hyphen

The hyphen is a punctuation mark used to join words and to separate syllables of a single word. The use of hyphens is called hyphenation.

The hyphen is sometimes confused with dashes (en dash , em dash and others), which are wider, or with t ...

s for better readability. The last morpheme marks for case, ''i'' marks the plural, and ''a'' is due to epenthesis

In phonology, epenthesis (; Greek ) means the addition of one or more sounds to a word, especially in the first syllable ('' prothesis''), the last syllable ('' paragoge''), or between two syllabic sounds in a word. The opposite process in whi ...

and does not have a meaning of its own.

=Nominative

= Like the otherUralic languages

The Uralic languages ( ), sometimes called the Uralian languages ( ), are spoken predominantly in Europe and North Asia. The Uralic languages with the most native speakers are Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian. Other languages with speakers ab ...

, the nominative

In grammar, the nominative case ( abbreviated ), subjective case, straight case, or upright case is one of the grammatical cases of a noun or other part of speech, which generally marks the subject of a verb, or (in Latin and formal variants of E ...

singular is unmarked and indicates the subject

Subject ( "lying beneath") may refer to:

Philosophy

*''Hypokeimenon'', or ''subiectum'', in metaphysics, the "internal", non-objective being of a thing

**Subject (philosophy), a being that has subjective experiences, subjective consciousness, or ...

or a predicate

Predicate or predication may refer to:

* Predicate (grammar), in linguistics

* Predication (philosophy)

* several closely related uses in mathematics and formal logic:

**Predicate (mathematical logic)

**Propositional function

**Finitary relation, o ...

. The nominative plural is also unmarked and always looks the same as the genitive

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can ...

singular.

=Genitive

= The ''genitive'' singular is unmarked and looks the same as thenominative

In grammar, the nominative case ( abbreviated ), subjective case, straight case, or upright case is one of the grammatical cases of a noun or other part of speech, which generally marks the subject of a verb, or (in Latin and formal variants of E ...

plural. The genitive plural is marked by an . The genitive is used:

* to indicate possession ( 'You have my book.' where is gen.)

* to indicate number, if said the number is between 2 and 6. ( 'My father's sister (my aunt) has two houses.', where is gen.)

* with prepositions ( ''+ EN': 'by something', 'beyond something')

* with most postpositions. ( 'They went to your grandmother's (house).', 'They went to visit your grandmother.', where is gen)

The genitive has been replacing the partitive for some time and is nowadays more commonly used in its place.

=Accusative

= Theaccusative

In grammar, the accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to receive the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: "me", "him", "her", " ...

is the direct object

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an a ...

case and it is unmarked in the singular. In the plural, its marker is , which is preceded by the plural marker , making it look the same as the plural illative

In grammar, the illative case (; abbreviated ; from "brought in") is a grammatical case used in the Finnish, Estonian, Lithuanian, Latvian and Hungarian languages. It is one of the locative cases, and has the basic meaning of "into (the inside ...

. The accusative is also used to mark some adjuncts, e.g. ('the entire winter').

=Locative

= Thelocative

In grammar, the locative case ( ; abbreviated ) is a grammatical case which indicates a location. In languages using it, the locative case may perform a function which in English would be expressed with such prepositions as "in", "on", "at", and " ...

marker in the singular is and in the plural. This case is used to indicate:

* where something is : ('“There is a book in the kota''”)''

* where it is coming from: (“The girls came home from Sevettijärvi”)

* who has possession of something: “'He/she has a lasso”

In addition, it is used with certain verbs:

* to ask someone s.t. : loc

LOC, L.O.C., Loc, LoC, or locs may refer to:

Places

* Lóc, a village in Sângeorgiu de Pădure, Mureș County, Romania

* Lócs, a village in Vas county, Hungary

* Line of Contact, meeting place of Western and Eastern Allied forces at the end ...

=Illative

= Theillative

In grammar, the illative case (; abbreviated ; from "brought in") is a grammatical case used in the Finnish, Estonian, Lithuanian, Latvian and Hungarian languages. It is one of the locative cases, and has the basic meaning of "into (the inside ...

marker actually has three different markers in the singular to represent the same case: , and . The plural illative marker is , which is preceded by the plural marker , making it look the same as the plural accusative

In grammar, the accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to receive the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: "me", "him", "her", " ...

. This case is used to indicate:

* where something is going

* who is receiving something

* the indirect object

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an a ...

=Comitative

= Thecomitative

In grammar, the comitative case (abbreviated ) is a grammatical case that denotes accompaniment. In English, the preposition "with", in the sense of "in company with" or "together with", plays a substantially similar role. Other uses of "with", l ...

is used to state “with whom” or “with what means” something is done. The case marker is -in in the singular and in the plural. T:

* “I left church with the children.”

* “I left church with my sister.”

* “The mouth is wiped with a piece of cloth.”

To form the comitative singular, use the genitive singular form of the word as the root

In vascular plants, the roots are the plant organ, organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often bel ...

and '. To form the comitative plural, use the plural genitive root and .

=Abessive

= The abessive case is used to state that someone is “without” something. Theabessive

In linguistics, abessive (abbreviated or ), caritive (abbreviated ) and privative (abbreviated ) is the grammatical case expressing the lack or absence of the marked noun. In English, the corresponding function is expressed by the preposition '' ...

marker is in both the singular and the plural. It always has a tertiary stress.

* “I left church without the children.”

* “They went in the house without the girl.”

* “They went in the house without the girls”.

=Essive

= The dual form of theessive

In grammar, the essive case, or similaris case, ( abbreviated ) is a grammatical case.O'Grady, William, John Archibald, Mark Aronoff, and Janie Rees-Miller. "Morphology: The Analysis of Word Structure." Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction. 6 ...

is still used with pronouns, but not with nouns and does not appear at all in the plural

In many languages, a plural (sometimes list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated as pl., pl, , or ), is one of the values of the grammatical number, grammatical category of number. The plural of a noun typically denotes a quantity greater than ...

.

=Partitive

= Thepartitive

In linguistics, a partitive is a word, phrase, or Grammatical case, case that indicates partialness. Nominal (linguistics), Nominal partitives are syntactic constructions, such as "some of the children", and may be classified semantically as either ...

is only used in the singular

Singular may refer to:

* Singular, the grammatical number that denotes a unit quantity, as opposed to the plural and other forms

* Singular or sounder, a group of boar, see List of animal names

* Singular (band), a Thai jazz pop duo

*'' Singula ...

and can be replaced by the genitive in most cases. The partitive marker is .

1. It appears after numbers larger than six:

* : 'eight lassos'

This can be replaced with .

2. It is also used with certain postpositions

Adpositions are a class of words used to express spatial or temporal relations (''in, under, towards, behind, ago'', etc.) or mark various semantic roles (''of, for''). The most common adpositions are prepositions (which precede their complemen ...

:

* : 'against a kota'

This can be replaced with

3. It can be used with the comparative

The degrees of comparison of adjectives and adverbs are the various forms taken by adjectives and adverbs when used to compare two entities (comparative degree), three or more entities (superlative degree), or when not comparing entities (positi ...

to express that which is being compared:

* : 'better than gold'

This would nowadays more than likely be replaced by

Pronouns

= Personal pronouns

= Thepersonal pronoun

Personal pronouns are pronouns that are associated primarily with a particular grammatical person – first person (as ''I''), second person (as ''you''), or third person (as ''he'', ''she'', ''it''). Personal pronouns may also take different f ...

s have three numbers: singular, plural and dual

Dual or Duals may refer to:

Paired/two things

* Dual (mathematics), a notion of paired concepts that mirror one another

** Dual (category theory), a formalization of mathematical duality

*** see more cases in :Duality theories

* Dual number, a nu ...

. The following table contains personal pronouns in the nominative and genitive/accusative cases.

The next table demonstrates the declension of a personal pronoun ''he/she'' (no gender distinction) in various cases:

Possessive markers

Next to number and case, Skolt Sámi nouns also inflect for possession. However, usage ofpossessive affix

In linguistics, a possessive affix (from ) is an affix (usually suffix or prefix) attached to a noun to indicate its possessor, much in the manner of possessive adjectives.

Possessive affixes are found in many languages of the world. The '' Wor ...

es seems to decrease among speakers. The following table shows possessive inflection

In linguistic Morphology (linguistics), morphology, inflection (less commonly, inflexion) is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical category, grammatical categories such as grammatical tense, ...

of the word ('tree').

Verbs

Skolt Sámi verbsinflect

In linguistic morphology, inflection (less commonly, inflexion) is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, a ...

(inflection of verbs is also referred to as conjugation

Conjugation or conjugate may refer to:

Linguistics

*Grammatical conjugation, the modification of a verb from its basic form

*Emotive conjugation or Russell's conjugation, the use of loaded language

Mathematics

*Complex conjugation, the change o ...

) for person

A person (: people or persons, depending on context) is a being who has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations suc ...

, mood, number

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The most basic examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers can ...

, and tense. A full inflection table of all person-marked forms of the verb ('to hear') is given below.

It can be seen that inflection involves changes to the verb stem as well as inflectional suffixes. Changes to the stem are based on verbs being categorized into several inflectional classes. The different inflectional suffixes are based on the categories listed below.

Person

Skolt Sámiverb

A verb is a word that generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual description of English, the basic f ...

s conjugate for four grammatical person

In linguistics, grammatical person is the grammatical distinction between deictic references to participant(s) in an event; typically, the distinction is between the speaker ( first person), the addressee ( second person), and others ( third p ...

s:

* first person

* second person

* third person

* fourth person

Within linguistics, obviative (abbreviated ) third person is a grammatical-person marking that distinguishes a referent that is less important to the discourse from one that is more important (proximate). The obviative is sometimes referred to a ...

, also called the indefinite person

Mood

Skolt Sámi has 5grammatical mood

In linguistics, grammatical mood is a grammatical feature of verbs, used for signaling modality. That is, it is the use of verbal inflections that allow speakers to express their attitude toward what they are saying (for example, a statement ...

s:

* indicative

A realis mood ( abbreviated ) is a grammatical mood which is used principally to indicate that something is a statement of fact; in other words, to express what the speaker considers to be a known state of affairs, as in declarative sentence

Dec ...

* imperative ( 'Come home soon!')

* conditional

* potential

Potential generally refers to a currently unrealized ability. The term is used in a wide variety of fields, from physics to the social sciences to indicate things that are in a state where they are able to change in ways ranging from the simple r ...

* optative

The optative mood ( or ; abbreviated ) is a grammatical mood that indicates a wish or hope regarding a given action. It is a superset of the cohortative mood and is closely related to the subjunctive mood but is distinct from the desiderative ...

Number

Skolt Sámiverb

A verb is a word that generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual description of English, the basic f ...

s conjugate for two grammatical number

In linguistics, grammatical number is a Feature (linguistics), feature of nouns, pronouns, adjectives and verb agreement (linguistics), agreement that expresses count distinctions (such as "one", "two" or "three or more"). English and many other ...

s:

* singular

Singular may refer to:

* Singular, the grammatical number that denotes a unit quantity, as opposed to the plural and other forms

* Singular or sounder, a group of boar, see List of animal names

* Singular (band), a Thai jazz pop duo

*'' Singula ...

* plural

In many languages, a plural (sometimes list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated as pl., pl, , or ), is one of the values of the grammatical number, grammatical category of number. The plural of a noun typically denotes a quantity greater than ...

Unlike other Sámi varieties further west, but in common with Kildin Saami, Skolt Sámi verbs do not inflect for dual

Dual or Duals may refer to:

Paired/two things

* Dual (mathematics), a notion of paired concepts that mirror one another

** Dual (category theory), a formalization of mathematical duality

*** see more cases in :Duality theories

* Dual number, a nu ...

number. Instead, verbs occurring with the dual personal pronouns appear in the corresponding plural form.

Tense

Skolt Sámi has 2simple tenses

Simple or SIMPLE may refer to:

*Simplicity, the state or quality of being simple

Arts and entertainment

* ''Simple'' (album), by Andy Yorke, 2008, and its title track

* "Simple" (Florida Georgia Line song), 2018

* "Simple", a song by John ...

:

* past

The past is the set of all Spacetime#Definitions, events that occurred before a given point in time. The past is contrasted with and defined by the present and the future. The concept of the past is derived from the linear fashion in which human ...

( 'I came to school yesterday.')

* non-past

The nonpast tense (also spelled non-past) ( abbreviated ) is a grammatical tense that distinguishes an action as taking place in times present or future. The nonpast tense contrasts with the past tense, which distinguishes an action as taking place ...

(. 'John is coming to my house today.')

and 2 compound tenses:

* perfect

Perfect commonly refers to:

* Perfection; completeness, and excellence

* Perfect (grammar), a grammatical category in some languages

Perfect may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''Perfect'' (1985 film), a romantic drama

* ''Perfect'' (20 ...

* pluperfect

The pluperfect (shortening of plusquamperfect), usually called past perfect in English, characterizes certain verb forms and grammatical tenses involving an action from an antecedent point in time. Examples in English are: "we ''had arrived''" ...

Non-finite verb forms

The verb forms given above are person-marked, also referred to asfinite

Finite may refer to:

* Finite set, a set whose cardinality (number of elements) is some natural number

* Finite verb, a verb form that has a subject, usually being inflected or marked for person and/or tense or aspect

* "Finite", a song by Sara Gr ...

. In addition to the finite forms, Skolt Sámi verbs have twelve participial and converb

In theoretical linguistics, a converb ( abbreviated ) is a nonfinite verb form that serves to express adverbial subordination: notions like 'when', 'because', 'after' and 'while'. Other terms that have been used to refer to converbs include ''adv ...

forms, as well as the infinitive

Infinitive ( abbreviated ) is a linguistics term for certain verb forms existing in many languages, most often used as non-finite verbs that do not show a tense. As with many linguistic concepts, there is not a single definition applicable to all ...

, which are non-finite. These forms are given in the table below for the verb ('to hear').

Auxiliary verbs

Skolt Sámi has twoauxiliary verb

An auxiliary verb ( abbreviated ) is a verb that adds functional or grammatical meaning to the clause in which it occurs, so as to express tense, aspect, modality, voice, emphasis, etc. Auxiliary verbs usually accompany an infinitive verb or ...

s, one of which is (glossed

A gloss is a brief notation, especially a marginalia, marginal or interlinear gloss, interlinear one, of the meaning of a word or wording in a text. It may be in the language of the text or in the reader's language if that is different.

A collec ...

as 'to be'), the other one is the negative auxiliary verb (see the following paragraph).

Inflection of is given below.

is used, for example, to assign tense to lexical verb In linguistics a lexical verb or main verb is a member of an open class of verbs that includes all verbs except auxiliary verbs. Lexical verbs typically express action, state, or other predicate meaning. In contrast, auxiliary verbs express gram ...

s in the conditional or potential mood

In linguistics, irrealis moods (abbreviated ) are the main set of grammatical moods that indicate that a certain situation or action is not known to have happened at the moment the speaker is talking. This contrasts with the realis moods. They ar ...

which are not marked for tense themselves:

*

(negation (1st P. Sg.) – then – 1st P. Sg. – even – ask (negated conditional) – if – 1st P. Sg. – know (1st P. Sg. conditional) – be (1st P. Sg. conditional) – soup – make (past participle, no tense marking) – before)

'I wouldn't even ask if I knew, if I had made soup before!'

=Negative verb

= Skolt Sámi, like Finnic and the other Sámi languages, has anegative verb

Dryer defined three different types of negative markers in language. Beside negative particles and negative affixes, negative verbs play a role in various languages. The negative verb is used to implement a clausal negation. The negative predic ...

. In Skolt Sámi, the negative verb conjugates according to mood (indicative, imperative and optative), person

A person (: people or persons, depending on context) is a being who has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations suc ...

(1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th) and number

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The most basic examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers can ...

(singular and plural).

Note that + is usually written as , , or + is usually written as or .

Unlike the Sámi languages further west, Skolt Sámi no longer has separate forms for the dual and plural of the negative verb and uses the plural forms for both instead.

Word order

Declarative clauses

The most frequent word order in simple,declarative sentence

Declarative may refer to:

* Declarative learning, acquiring information that one can speak about

* Declarative memory, one of two types of long term human memory

* Declarative programming

In computer science, declarative programming is a programm ...

s in Skolt Sámi is subject–verb–object (SVO). However, as cases are used to mark relations between different noun phrase

A noun phrase – or NP or nominal (phrase) – is a phrase that usually has a noun or pronoun as its head, and has the same grammatical functions as a noun. Noun phrases are very common cross-linguistically, and they may be the most frequently ...

s, and verb forms mark person and number of the subject, Skolt Sámi word order allows for some variation.

An example of an SOV sentence would be:

* (woman (Pl., Nominative) – protection (Sg., Nominative) + skirt (Pl., Accusative) – sew (3rd P. Pl., Past)) 'The women sewed protective skirts.'

Intransitive sentences follow the order subject-verb (SV):

* (lake (Pl., Nominative) – freeze (3rd P. Pl., Present)) 'The lakes freeze.'

An exception to the SOV word order can be found in sentences with an auxiliary verb

An auxiliary verb ( abbreviated ) is a verb that adds functional or grammatical meaning to the clause in which it occurs, so as to express tense, aspect, modality, voice, emphasis, etc. Auxiliary verbs usually accompany an infinitive verb or ...

. While in other languages, an OV word order has been found to correlate with the auxiliary verb coming after the lexical verb In linguistics a lexical verb or main verb is a member of an open class of verbs that includes all verbs except auxiliary verbs. Lexical verbs typically express action, state, or other predicate meaning. In contrast, auxiliary verbs express gram ...

, the Skolt Sámi auxiliary verb ('to be') precedes the lexical verb. This has been related to the verb-second (V2) phenomenon which binds the finite verb

A finite verb is a verb that contextually complements a subject, which can be either explicit (like in the English indicative) or implicit (like in null subject languages or the English imperative). A finite transitive verb or a finite intra ...

to at most the second position of the respective clause. However, in Skolt Sámi, this effect seems to be restricted to clauses with an auxiliary verb.

An example of a sentence with the auxiliary in V2 position:

* (northern light (Pl., Nominative) – be (3rd P. Pl., Past) – female reindeer (Sg., Accusative) – eat (Past Participle)) 'The northern lights had eaten the female reindeer.'

Interrogative clauses

= Polar questions

= In Skolt Sámi, polar questions, also referred to as yes–no questions, are marked in two different ways. Morphologically, aninterrogative

An interrogative clause is a clause whose form is typically associated with question-like meanings. For instance, the English sentence (linguistics), sentence "Is Hannah sick?" has interrogative syntax which distinguishes it from its Declarative ...

particle

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscle in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

, ''-a'', is added as an affix

In linguistics, an affix is a morpheme that is attached to a word stem to form a new word or word form. The main two categories are Morphological derivation, derivational and inflectional affixes. Derivational affixes, such as ''un-'', ''-ation' ...

to the first word of the clause. Syntactically

In linguistics, syntax ( ) is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure (constituency) ...

, the element which is in the scope of the question is moved to the beginning of the clause. If this element is the verb, subject and verb are inversed in comparison to the declarative SOV word order.

* (leave (2nd P. Pl., Present, Interrogative) – 2nd P. Dual Nominative – 1st P. Sg. Genitive – behalf – father (Sg. Genitive 1st P. Pl.) – grave (Sg. Genitive) – onto) 'Will the two of you go, on my behalf, to our father's grave?'

If an auxiliary verb is used, this is the one which is moved to the initial sentence position and also takes the interrogative affix.

* (be (2nd P. Sg., Present, Interrogative) – open (Past Participle) – that (Sg. Accusative) – door (Sg. Accusative)) 'Have you opened that door?'

* (be (2nd P. Sg., Interrogative) – 2nd P. Sg. Nominative – Jefremoff) 'Are you Mr. Jefremoff?'

A negated polar question, using the negative auxiliary verb, shows the same structure:

* (Negation 3rd P. Sg., Interrogative – middle – brother (Sg. Nominative, 2nd P. Sg.) – come (Past Participle)) 'Didn't your middle brother come?'

An example of the interrogative particle being added to something other than the verb, would be the following:

* (still (Interrogative) – be (3rd P. Sg., Present) – story (Pl., Nominative)) 'Are there still stories to tell?'

= Information questions

= Information questions in Skolt Sámi are formed with a question word in clause-initial position. There also is a gap in the sentence indicating the missing piece of information. This kind of structure is similar toWh-movement

In linguistics, wh-movement (also known as wh-fronting, wh-extraction, or wh-raising) is the formation of syntactic dependencies involving interrogative words. An example in English is the dependency formed between ''what'' and the object position ...

in languages such as English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

. There are mainly three question words corresponding to the English 'what', 'who', and 'which' (out of two). They inflect for number and case, except for the latter which only has singular forms. It is noteworthy that the illative form of ('what') corresponds to the English 'why'. The full inflectional paradigm of all three question words can be found below.

Some examples of information questions using one of the three question words:

* (what (Sg., Accusative) – cry (2nd P. Sg., Present)) 'What are you crying about?'

* (what (Sg., Illative) – come (2nd P. Sg., Past)) 'Why did you come?'

* (who (Sg., Nominative) – 2nd P. Sg., Locative – be (3rd P. Sg., Past) – godmother (Sg., Nominative) 'Who was your godmother?'

* (which (Sg., Nominative) – begin (3rd P. Sg., Present) – wrestle (Infinitive)) 'Which one of you will begin to wrestle?'

In addition to the above-mentioned, there are other question words which are not inflected, such as the following:

* : 'where', 'from where'

* : 'to where'

* : 'when'

* : 'how'

* : 'what kind'

An example sentence would be the following:

* (to where – leave (2nd P. Sg., Past)) 'Where did you go?'

Imperative clauses

The Skolt Sámi imperative generally takes a clause-initial position. Out of the five imperative forms (seeabove

Above may refer to:

*Above (artist)

Tavar Zawacki (b. 1981, California) is a Polish, Portuguese - American abstract artist and

internationally recognized visual artist based in Berlin, Germany. From 1996 to 2016, he created work under the ...

), those of the second person are most commonly used.

* (come (2nd P. Sg., Imperative) – 1st P. Pl., Genitive – way – on a visit) 'Come and visit us at our place!'

Imperatives in the first person form, which only exist as plurals, are typically used for hortative

In linguistics, hortative modalities (; abbreviated ) are verbal expressions used by the speaker to encourage or discourage an action. Different hortatives can be used to express greater or lesser intensity, or the speaker's attitude, for or a ...

constructions, that is for encouraging the listener (not) to do something. These imperatives include both the speaker and the listener.

* (start (1st P. Pl., Imperative) – wrestle (Infinitive)) 'Let's start to wrestle!'

Finally, imperatives in the third person are used in jussive

The jussive (abbreviated ) is a grammatical mood of verbs for issuing orders, commanding, or exhorting (within a subjunctive framework). English verbs are not marked for this mood. The mood is similar to the '' cohortative'' mood, which typically a ...

constructions, the mood used for orders and commands.

* (climb (3rd P. Pl., Imperative) – 3rd P. Pl., Nominative – hill (Sg., Genitive) – onto) 'Let them climb to the top of the hill!'v329–330

Lexicon

Kinship terms

Kinship terms

Kinship terminology is the system used in languages to refer to the persons to whom an individual is related through kinship. Different societies classify kinship relations differently and therefore use different systems of kinship terminology; ...

in Skolt Sámi mostly descend from proto-Uralic or proto-Samic. As in many Uralic languages, the word for “son” is a borrowing (''pä′rnn,'' from Germanic ''barna'').

For extended family members, Skolt Sámi distinguishes not only the relationship to ego, but also their gender, age and their own relationship to one's nuclear family.

Reindeer husbandry words

Traditionally, the Sámi arereindeer herders

Reindeer herding is when reindeer are herded by people in a limited area. Currently, reindeer are the only semi-domesticated animal which naturally belong to the North. Reindeer herding is conducted in nine countries: Norway, Finland, Sweden, Russ ...

, and as such, Sámi languages have developed a wide vocabulary with terms to describe both the animal and actions related to its husbandry

Animal husbandry is the branch of agriculture concerned with animals that are raised for meat, fibre, milk, or other products. It includes day-to-day care, management, production, nutrition, selective breeding, and the raising of livestock. ...

. These terms describe not only gender and age but also their color, their position in the herd, and others. Below are only some of the underived words, and many other possibilities exist in compounds, especially with -''puäʒʒ'' and -''čuä′rvv'' as head words: ''paaspuäʒʒ'' “an angry reindeer”, ''njä′bllpuäʒʒ,'' “a quiet reindeer”, ''koomčuäʹrvv'' ''“''a reindeer with curved antlers”, etc.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *External links

The Children's TV series Binnabánnaš in Skolt Sámi

Nuõrttsää′mǩiõl alfabee′tt – koltankieliset aakkoset

�Skolt Saami alphabet by the Finnish Saami Parliament

Say it in Saami

Yle's colloquial Northern Saami-Inari Saami-Skolt Saami-English phrasebook online

Surrey Morphology Group – Skolt Saami

* Skolt Saami verb paradigm visualisations. Feist, Timothy, Matthew Baerman, Greville G. Corbett & Erich Round. 2019. Surrey Lexical Splits Visualisations (Skolt Saami). University of Surrey. https://lexicalsplits.surrey.ac.uk/skoltsaami.html

A very small Skolt Sámi – English vocabulary (< 500 words)

Skolt Sámi - Finnish/English/Russian dictionary

(robust finite-state, open-source)

Northern Sámi – Inari Sámi – Skolt Sámi – English dictionary

(requires a password nowadays)

Names of birds

found in

Sápmi

is the cultural region traditionally inhabited by the Sámi people. Sápmi includes the northern parts of Fennoscandia, stretching over four countries: Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. Most of Sápmi lies north of the Arctic Circle, boun ...

in a number of languages, including Skolt Sámi and English. Search function only works with Finnish input though.

Sää′mjie′llem

Sámi Museum site on the history of the Skolt Sámi in Finland

A number of linguistic articles on Skolt Sámi.

Erkki Lumisalmi talks in Skolt Sámi

(mp3)

The Palatalization Mark in Skolt Sámi.

Ranskalaisen tutkimusmatkailijan arkistot palautumassa kolttasaamelaisille – aineisto sisältää satoja dioja ja valokuvia (The French explorer's archives are being restored to the Koltsa Sámi - the material contains hundreds of slides and photographs)

YLE

Yleisradio Oy (; ), abbreviated as Yle () (formerly styled in all uppercase until 2012), translated into English as the Finnish Broadcasting Company, is Finland's national public broadcasting company, founded in 1926. It is a joint-stock comp ...

.fi. 2024-07-22

Maailmankuulu tutkija tarkkaili kolttasaamelaisia 50 vuotta sitten ja jätti nyt ainutlaatuisen perinnön (A world-renowned researcher observed the Koltsa Sámi 50 years ago and now left a unique legacy)

YLE

Yleisradio Oy (; ), abbreviated as Yle () (formerly styled in all uppercase until 2012), translated into English as the Finnish Broadcasting Company, is Finland's national public broadcasting company, founded in 1926. It is a joint-stock comp ...

.fi. 2024-05-14

{{DEFAULTSORT:Skolt Sámi Language

Eastern Sámi languages

Indigenous languages of European Russia