Sir Robert Laird Borden on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Robert Laird Borden (June 26, 1854 – June 10, 1937) was a Canadian lawyer and Conservative politician who served as the eighth

The Liberal prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier, proposed the building of the

The Liberal prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier, proposed the building of the

Also in 1912, the provinces of

Also in 1912, the provinces of

Despite the threat of an economic collapse and the need for more revenue to fund the war effort, Borden's

Despite the threat of an economic collapse and the need for more revenue to fund the war effort, Borden's

Borden died on June 10, 1937, in Ottawa and is buried in the

Borden died on June 10, 1937, in Ottawa and is buried in the

''Canadian Constitutional Studies'' by Robert Borden at archive.org

''Comments on the Senate's rejection of the Naval Aid Bill '' by Robert Borden at archive.org

vol 1 online

als

vol 2 online

* Brown, Robert Craig, & Cook, Ramsay (1974). ''Canada: 1896–1921''. * Cook, George L. "Sir Robert Borden, Lloyd George and British Military Policy, 1917-1918." The Historical Journal 14.2 (1971): 371–395

online

* Cook, Tim. ''Warlords: Borden, Mackenzie King and Canada's World Wars'' (2012) 472p

online

* Cook, Tim. "Canada's Warlord: Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden's Leadership during the Great War." ''Journal of Military and Strategic Studies'' 13.3 (2011) pp 1–24

online

* Granatstein, J. L. & Hillmer, Norman (1999). ''Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada's Leaders''. HarperCollins ; pp. 61–74. *Levine, Allan. "Scrum Wars, The Prime Ministers and the Media." Dundurn, c1993. 69–101 * MacMillan, Margaret (2003). ''Peacemakers: Six Months that Changed the World''. London: John Murray (on the Paris Peace Conference of 1919) * Macquarrie, Heath. "Robert Borden and the Election of 1911." ''Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science,'' 1959, Vol. 25 Issue 3, pp. 271–28

in JSTOR

* Thornton, Martin. ''Churchill, Borden and Anglo-Canadian Naval Relations, 1911-14'' (Springer, 2013).

Sir Robert Borden fonds

at

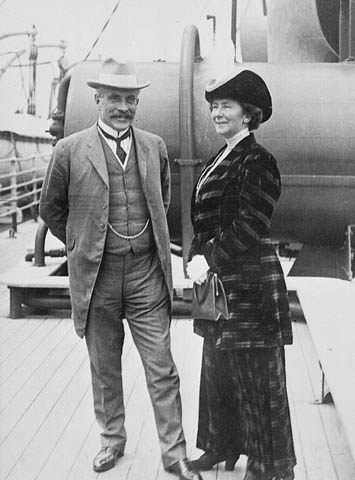

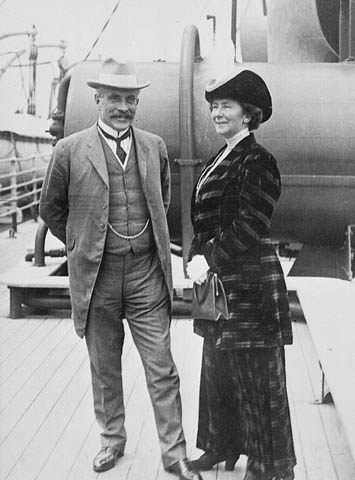

Comments on the Senate's rejection of the Naval Aid BillPhotograph:Robert L. Borden, 1905

- McCord Museum * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Borden, Robert Laird 1854 births 1937 deaths Canadian Anglicans Canadian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George 19th-century Canadian lawyers Canadian King's Counsel 20th-century Canadian memoirists Canadian people of English descent Chancellors of Queen's University at Kingston Cornell family Converts to Anglicanism from Presbyterianism Leaders of the opposition (Canada) Leaders of the Conservative Party of Canada (1867–1942) Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Nova Scotia Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Lawyers in Nova Scotia Politicians from Kings County, Nova Scotia People of New England Planter descent Prime ministers of Canada Unionist Party (Canada) MPs Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Canadian Secretaries of State for External Affairs Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Canadian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Canadian Freemasons Burials at Beechwood Cemetery (Ottawa) Presidents of the Canadian Historical Association 20th-century members of the House of Commons of Canada 19th-century members of the House of Commons of Canada

prime minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada () is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority of the elected House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons ...

from 1911 to 1920. He is best known for his leadership of Canada during World War I

The history of Canada in World War I began on August 4, 1914, when the United Kingdom entered the World War I, First World War (1914–1918) by declaring war on German Empire, Germany. The United Kingdom declaration of war upon Germany (1914), B ...

.

Borden was born in Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia

Grand-Pré () is a rural community in Kings County, Nova Scotia, Kings County, Nova Scotia, Canada. Its French name translates to "Great/Large Meadow" and the community lies at the eastern edge of the Annapolis Valley several kilometres east of t ...

. He worked as a schoolteacher for a period and then served his articles of clerkship

Articled clerk is a title used in Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries for one who is studying to be an accountant or a lawyer. In doing so, they are put under the supervision of someone already in the profession, now usually for two ye ...

at a Halifax law firm. He was called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in 1878 and soon became one of Nova Scotia's most prominent barristers. Borden was elected to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

in the 1896 federal election, representing the Conservative Party. He replaced Charles Tupper

Sir Charles Tupper, 1st Baronet (July 2, 1821 – October 30, 1915) was a Canadian Father of Confederation who served as the sixth prime minister of Canada from May 1 to July 8, 1896. As the premier of Nova Scotia from 1864 to 1867, he led ...

as party leader in 1901, but was defeated in two federal elections by Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier

Sir Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier (November 20, 1841 – February 17, 1919) was a Canadian lawyer, statesman, and Liberal politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Canada from 1896 to 1911. The first French Canadians, French ...

in 1904

Events

January

* January 7 – The distress signal ''CQD'' is established, only to be replaced 2 years later by ''SOS''.

* January 8 – The Blackstone Library is dedicated, marking the beginning of the Chicago Public Library system.

* ...

and 1908

This is the longest year in either the Julian or Gregorian calendars, having a duration of 31622401.38 seconds of Terrestrial Time (or ephemeris time), measured according to the definition of mean solar time.

Events

January

* January ...

. However, in the 1911 federal election, Borden led the Conservatives to victory after he claimed that the Liberals' proposed trade reciprocity treaty with the United States would lead to the US influencing Canadian identity and weaken ties with Great Britain.

Borden's early years as prime minister focused on strengthening relations with Britain. Halfway through his first term, World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out. To send soldiers overseas, he created the Canadian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF; French: ''Corps expéditionnaire canadien'') was the expeditionary warfare, expeditionary field force of Canada during the First World War. It was formed on August 15, 1914, following United Kingdom declarat ...

. He also became significantly interventionist by passing the ''War Measures Act

The ''War Measures Act'' (; 5 George V, Chap. 2) was a statute of the Parliament of Canada that provided for the declaration of war, invasion, or insurrection, and the types of emergency measures that could thereby be taken. The Act was brough ...

'' which gave the government extraordinary powers. To increase government revenue to fund the war effort, Borden's government issued victory bonds, raised tariffs, and introduced new taxes including the income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

. In 1917, facing what he believed to be a shortage in Canadian soldiers, Borden introduced conscription, angering French Canada

Francophone Canadians or French-speaking Canadians are citizens of Canada who speak French, and sometimes refers only to those who speak it as their first language. In 2021, 10,669,575 people in Canada or 29.2% of the total population spoke Fren ...

and sparking a national divide known as the Conscription Crisis. Despite this, his Unionist Party composed of Conservatives and pro-conscription Liberals was re-elected with an overwhelming majority

A majority is more than half of a total; however, the term is commonly used with other meanings, as explained in the "#Related terms, Related terms" section below.

It is a subset of a Set (mathematics), set consisting of more than half of the se ...

in the 1917 federal election. At the Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

, Borden sought to expand the autonomy of Canada and other Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

s. On the home front, Borden's government dealt with the consequences of the Halifax Explosion

On the morning of 6 December 1917, the French cargo ship collided with the Norwegian vessel in the harbour of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. ''Mont-Blanc'', laden with Explosive material, high explosives, caught fire and exploded, devastat ...

, introduced women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

for federal elections, nationalized

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

railways by establishing the Canadian National Railway

The Canadian National Railway Company () is a Canadian Class I freight railway headquartered in Montreal, Quebec, which serves Canada and the Midwestern and Southern United States.

CN is Canada's largest railway, in terms of both revenue a ...

, and controversially used the North-West Mounted Police

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was a Canadian paramilitary police force, established in 1873, to maintain order in the new Canadian North-West Territories (NWT) following the 1870 transfer of Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory to ...

to break up the 1919 Winnipeg general strike

The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 was one of the most famous and influential strikes in Canadian history. For six weeks, May 15 to June 26, more than 30,000 strikers brought economic activity to a standstill in Winnipeg, Manitoba, which at the ...

.

Borden retired from politics in 1920. In his retirement, he was Chancellor of Queen's University from 1924 to 1930 and was president of two financial institutions, the Barclays Bank

Barclays PLC (, occasionally ) is a British multinational universal bank, headquartered in London, England. Barclays operates as two divisions, Barclays UK and Barclays International, supported by a service company, Barclays Execution Services ...

of Canada and the Crown Life Insurance Company from 1928 until his death in 1937. Borden places above-average among historians and the public in rankings of prime ministers of Canada. Borden was the last prime minister born before Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

and the last prime minister to be knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

ed, having accepted a knighthood in 1914.

Early life and career (1854–1874)

Borden was born and educated inGrand-Pré, Nova Scotia

Grand-Pré () is a rural community in Kings County, Nova Scotia, Kings County, Nova Scotia, Canada. Its French name translates to "Great/Large Meadow" and the community lies at the eastern edge of the Annapolis Valley several kilometres east of t ...

, a farming community at the eastern end of the Annapolis Valley

The Annapolis Valley is a valley and region in the province of Nova Scotia, Canada. It is located in the western part of the Nova Scotia peninsula, formed by a Trough (geology), trough between two parallel mountain ranges along the shore of the B ...

. His great-grandfather, Perry Borden Sr. of Tiverton, Rhode Island

Tiverton is a town in Newport County, Rhode Island, United States. The population was 16,359 at the 2020 census.

Geography

Tiverton is located on the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay, across the Sakonnet River from Aquidneck Island (also ...

, had taken up Acadian

The Acadians (; , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Today, most descendants of Acadians live in either the Northern American region of Acadia, ...

land in this region in 1760 as one of the New England Planters

The New England Planters were settlers from the New England colonies who responded to invitations by the lieutenant governor (and subsequently governor) of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence, to settle lands left vacant by the Bay of Fundy Campaign ...

. The Borden family had immigrated from Headcorn, Kent, England, to New England in the 17th century. Also arriving in this group was a great-great-grandfather, Robert Denison, who had come from Connecticut at about the same time. Perry had accompanied his father, Samuel Borden, the chief surveyor chosen by the government of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

to survey the former Acadian land and draw up new lots for the Planters in Nova Scotia. Through the marriage of his patrilineal ancestor Richard Borden to Innocent Cornell, Borden is descendant from Thomas Cornell of Portsmouth, Rhode Island

Portsmouth is a town in Newport County, Rhode Island, United States. The population was 17,871 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census. Portsmouth is the second-oldest municipality in Rhode Island, after Providence Plantations, Provide ...

.

Borden's father, Andrew Borden, was judged by his son to be "a man of good ability and excellent judgement" and of a "calm, contemplative and philosophical" turn of mind, but "he lacked energy and had no great aptitude for affairs." His mother Eunice Jane Laird was more driven, possessing "very strong character, remarkable energy, high ambition and unusual ability". Her ambition was transmitted to her first-born child, who applied himself to his studies while assisting his parents with the farm work he found so disagreeable. Borden's cousin, Frederick Borden, was a prominent Liberal politician.

At age nine, Borden became a day student for the local private academy, Acacia Villa School. The school sought to "fit boys physically, morally, and intellectually, for the responsibilities of life." There, Borden developed an interest in the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, and Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

languages. At age 14, Borden became the assistant master for classical studies. In late 1873, Borden began working as a professor for classics and mathematics at the Glenwood Institute

Glenwood Institute was a private co-educational boarding school in Matawan, New Jersey.

The school was established in 1834 by William Little. William Cooley was the first principal of the school, which had only two students in its first year. ...

in Matawan, New Jersey

Matawan () is a Borough (New Jersey), borough in Monmouth County, New Jersey, Monmouth County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. A historic community located near the Raritan Bay in the much larger Raritan River, Raritan Valley region, Raritan ...

. Seeing no future in teaching, he returned to Nova Scotia in 1874.

Lawyer (1874–1896)

Despite having no formal university education, Borden went to serve hisarticles of clerkship

Articled clerk is a title used in Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries for one who is studying to be an accountant or a lawyer. In doing so, they are put under the supervision of someone already in the profession, now usually for two ye ...

for four years at a Halifax law firm. Borden also attended the School of Military Instruction in the city during the winter of 1878. In August 1878, Borden was called to the Nova Scotia Bar, placing first in the bar examinations. He went to Kentville, Nova Scotia

Kentville is an incorporated town in Nova Scotia. It is the most populous town in the Annapolis Valley. As of 2021, the town's population was 6,630. Its census agglomeration is 26,929.

History

Kentville owes its location to the Cornwallis Riv ...

, as the junior partner of the Conservative lawyer John P. Chipman. In 1880, Borden was inducted into the Freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

s St Andrew's lodge No. 1. In 1882, Borden, despite being a Liberal, accepted Wallace Graham's request to move to Halifax and join the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

law firm headed by Graham and Charles Hibbert Tupper. In 1886, Borden broke with the Liberal Party after he disagreed with Premier William Stevens Fielding

William Stevens Fielding, (24 November 1848 – 23 June 1929) was a Canadian Liberal politician, the seventh premier of Nova Scotia (1884–96), and the federal Minister of Finance from 1896 to 1911 and again from 1921 to 1925.

Early life

...

's campaign to withdraw Nova Scotia from Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

. In the autumn of 1889, when he was only 35, Borden became the senior partner following the departure of Graham and Tupper for the bench and politics, respectively.

His financial future guaranteed, on September 25, 1889, Borden married Laura Bond

Laura Borden, Lady Borden (née Bond; November 26, 1861 – September 7, 1940) was the wife of Sir Robert Laird Borden who was the eighth Prime Minister of Canada.

She was born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and married Borden in September 1889. Sh ...

, the daughter of a Halifax hardware merchant. They had no children. Bond later became president of the Local Council of Women of Halifax

The Local Council of Women of Halifax (LCWH) is an organization in Halifax, Nova Scotia devoted to improving the lives of women and children. One of the most significant achievements of the LCWH was its 24-year struggle for women's right to vote ...

, until her resignation in 1901. She also later became president of the Aberdeen Association, vice-president of the Women's Work Exchange in Halifax, and corresponding secretary of the Associated Charities of the United States. The Bordens spent several weeks vacationing in England and Europe in the summers of 1891 and 1893. In 1894, Borden bought a large property and home on the south side of Quinpool Road, which the couple called Pinehurst.

In 1893, Borden successfully argued the first of two cases which he took to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 August ...

. He represented many of the important Halifax businesses and sat on the boards of Nova Scotian companies, including the Bank of Nova Scotia

The Bank of Nova Scotia (), operating as Scotiabank (), is a Canadian multinational banking and financial services company headquartered in Toronto, Ontario. One of Canada's Big Five banks, it is the third-largest Canadian bank by deposits and ...

and the Crown Life Insurance Company. By the mid-1890s, Borden's firm was so prominent that it attracted notable clients, such as the Bank of Nova Scotia, Canada Atlantic Steamship, and the Nova Scotia Telephone Company. Borden had several court cases in Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

, and while in that city he frequently met with Prime Minister John Sparrow David Thompson

Sir John Sparrow David Thompson (November 10, 1845 – December 12, 1894) was a Canadian lawyer, judge and politician who served as the fourth prime minister of Canada from 1892 until his death in 1894. He had previously been fifth premier o ...

, a fellow Nova Scotian. In 1896, Borden became president of the Nova Scotia Barristers' Society and took the initiative in organizing the founding meetings of the Canadian Bar Association

The Canadian Bar Association (CBA), or Association du barreau canadien (ABC) in French, represents over 37,000 lawyers, judges, notaries, law teachers, and law students from across Canada.

History

The Association's first Annual Meeting was ...

in Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

.

On April 27, 1896, Borden went to Charles Tupper

Sir Charles Tupper, 1st Baronet (July 2, 1821 – October 30, 1915) was a Canadian Father of Confederation who served as the sixth prime minister of Canada from May 1 to July 8, 1896. As the premier of Nova Scotia from 1864 to 1867, he led ...

's home for a dinner party. Tupper, who was about to succeed Mackenzie Bowell

Sir Mackenzie Bowell (; December 27, 1823 – December 10, 1917) was a Canadian newspaper publisher and politician, who served as the fifth prime minister of Canada, in office from 1894 to 1896.

Bowell was born in Rickinghall, Suffolk, E ...

as prime minister, asked Borden to run for the federal electoral district of Halifax for the upcoming election. Borden accepted the request.

Early political career (1896–1901)

Campaigning in favour of his party'sNational Policy

The National Policy was a Canadian economic program introduced by John A. Macdonald's Conservative Party in 1876. After Macdonald led the Conservatives to victory in the 1878 Canadian federal election, he began implementing his policy in 1879. ...

, Borden was elected as a member of Parliament (MP) in the 1896 federal election as a Conservative. However, the Conservative Party as a whole was defeated by the Liberals led by Wilfrid Laurier

Sir Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier (November 20, 1841 – February 17, 1919) was a Canadian lawyer, statesman, and Liberal politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Canada from 1896 to 1911. The first French Canadians, French ...

.

Though an MP in Ottawa, Borden still practised law back in Halifax. He also remained loyal to Tupper. Borden participated in many House committees and over time emerged as a key figure in the party.

Leader of the Official Opposition (1901–1911)

Tupper announced his resignation as party leader after he led the Conservatives to their second consecutive defeat at the polls in 1900. Tupper, and his son Charles Hibbert Tupper (who was Borden's former colleague at the Halifax law firm) asked Borden to become leader, citing his work in Parliament and lack of enemies within the Conservative caucus. Borden at first was not keen to become leader, stating, "I have not either the experience or the qualifications which would enable me to successfully lead the party...It would be an absurdity for the party and madness for me." However, he later changed his position and on February 6, 1901, he was selected by the Conservative caucus as party leader. The Liberal prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier, proposed the building of the

The Liberal prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier, proposed the building of the Canadian Northern

The Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) was a historic Canadian transcontinental railway. At its 1923 merger into the Canadian National Railway , the CNoR owned a main line between Quebec City and Vancouver via Ottawa, Winnipeg, and Edmonton.

Mani ...

and Grand Trunk railways. Borden proposed for the railways to be government-owned and government-operated, stating the people would have a choice between "a government-owned railway or a railway-owned government." This position did not resonate with voters in the 1904 federal election; the Liberals won a slightly stronger majority

A majority is more than half of a total; however, the term is commonly used with other meanings, as explained in the "#Related terms, Related terms" section below.

It is a subset of a Set (mathematics), set consisting of more than half of the se ...

, while the Conservatives lost a few seats. Borden himself was defeated in his Halifax seat but re-entered the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

the next year via a by-election in Carleton (Ontario). In 1907, Borden announced the Halifax Platform. The Conservative Party's new policy called for reform of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and the civil service, a more selective immigration policy, free rural mail delivery, government regulation of telegraphs, telephones, and railways and eventually national ownership of telegraphs and telephones. In the 1908 federal election, Laurier's Liberals won for the fourth consecutive time. However, the Liberals experienced a drop in support as they won a slightly reduced majority. The Conservatives experienced a modest boost, gaining 10 seats.

In 1910 and 1911, Laurier proposed a reciprocity agreement with the United States. Borden opposed the treaty, stating that it would weaken ties with Britain, lead to Canadian identity being influenced by the US, and lead to American annexation of Canada. In the 1911 federal election, the Conservatives countered with a revised version of John A. Macdonald's National Policy

The National Policy was a Canadian economic program introduced by John A. Macdonald's Conservative Party in 1876. After Macdonald led the Conservatives to victory in the 1878 Canadian federal election, he began implementing his policy in 1879. ...

, campaigned on fears of American influence on Canada and disloyalty to Britain, and ran on the slogan "Canadianism or Continentalism". The Conservatives triumphed; they won a strong majority, ending over 15 years of Liberal rule.

Prime Minister (1911–1920)

Pre-war Canada

To aid the farmers who would have benefited had the reciprocity treaty been implemented, Borden's government passed the ''Canada Grain Act of 1912'' to establish a board of grain commissioners that would supervise grain inspection and regulate thegrain trade

The grain trade refers to the local and international trade in cereals such as wheat, barley, maize, rice, and other food grains. Grain is an important trade item because it is easily stored and transported with limited spoilage, unlike other agri ...

. This law would also allow the federal government to build or acquire and operate grain elevator

A grain elevator or grain terminal is a facility designed to stockpile or store grain. In the grain trade, the term "grain elevator" also describes a tower containing a bucket elevator or a pneumatic conveyor, which scoops up grain from a lowe ...

s at key points in the grain marketing and export system.

Also in 1912, the provinces of

Also in 1912, the provinces of Manitoba

Manitoba is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population ...

, Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

, and Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

were expanded through the ''Manitoba Boundaries Extension Act'', the ''Ontario Boundaries Extension Act'', and the ''Quebec Boundaries Extension Act''. These three provinces would take up the southern portion of the Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories is a federal Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada. At a land area of approximately and a 2021 census population of 41,070, it is the second-largest and the most populous of Provinces and territorie ...

.

In 1912 and 1913, Borden's government sought to pass a naval bill that would have sent $35 million for the construction of three dreadnought

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

s for the British Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. Laurier, now Opposition leader, argued that the bill would threaten Canadian autonomy. In May 1913, the bill was blocked by the Liberal-controlled Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

.

On June 22, 1914, Borden was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

ed; King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

awarded him the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III ...

.

First World War

In late July, Borden and his wife, Laura, went for a vacation to the Muskoka District Municipality. However, the trip was cut short afterWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out in Europe. On July 31, the Bordens were on a train for Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

. The next day, he returned to Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

. The British declaration of war on August 4, 1914, automatically brought Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

into the war.

Major reforms

On August 22, 1914, Parliament passed the controversial ''War Measures Act

The ''War Measures Act'' (; 5 George V, Chap. 2) was a statute of the Parliament of Canada that provided for the declaration of war, invasion, or insurrection, and the types of emergency measures that could thereby be taken. The Act was brough ...

'' (with support from both Conservatives and Liberals), which gave the government extraordinary and emergency powers, including the right to censor and suppress communications, the right to arrest, detain, and deport people without charges or trials, the right to control transportation, trade and manufacturing, and the right to seize private property during times of "war, invasion or insurrection". The act also allowed Borden to govern by order in council

An Order in Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom, this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' ...

, meaning that Cabinet was allowed to implement pieces of legislation without the need for a vote in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

and Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

.

Borden's government created the Canadian Patriotic Fund The Canadian Patriotic Fund (1914–1919) was a private fund-raising organization incorporated in 1914 by federal statute and headed by Montreal businessman and Conservative Party (Canada), Conservative Member of Parliament (Canada), Member of Parli ...

to give financial and social assistance to the families of soldiers. The government also raised tariffs on some high-demand consumer items to boost the economy.

In 1916, Borden's government established the National Research Council Canada

The National Research Council Canada (NRC; ) is the primary national agency of the Government of Canada dedicated to science and technology research and development. It is the largest federal research and development organization in Canada.

Th ...

for scientific and industrial research. In 1918, to gain information on Canada's population, social structure, and economy, the government established the Dominion Bureau of Statistics The Dominion Bureau of Statistics was a Canadian government organization responsible for conducting Census in Canada, censuses.

It was formed in 1918 by the Statistics Act, but was replaced by Statistics Canada in 1971.

The Dominion Statisticians w ...

through the ''Statistics Act

The ''Statistics Act'' () is an Act of the Parliament of Canada passed in 1918 which created the Dominion Bureau of Statistics, now called Statistics Canada since 1971.

The ''Statistics Act'' gives Statistics Canada the authority to "collect, c ...

''. It was renamed Statistics Canada

Statistics Canada (StatCan; ), formed in 1971, is the agency of the Government of Canada commissioned with producing statistics to help better understand Canada, its population, resources, economy, society, and culture. It is headquartered in ...

in 1971.

Borden's government set up the Canadian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF; French: ''Corps expéditionnaire canadien'') was the expeditionary warfare, expeditionary field force of Canada during the First World War. It was formed on August 15, 1914, following United Kingdom declarat ...

(CEF). The force posted several combat formations of the Western Front during the war. In December 1914, Borden stated, "there has not been, there will not be, compulsion or conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

." As the war dragged on, more troops for the CEF were deployed through the voluntary force. In July 1915, the number of CEF soldiers increased to 150,000 before being increased to 250,000 in October 1915 before doubling to 500,000 in January 1916. By mid-1916, the rate of volunteers enlisting started to slow down.

Economy

Despite the threat of an economic collapse and the need for more revenue to fund the war effort, Borden's

Despite the threat of an economic collapse and the need for more revenue to fund the war effort, Borden's finance minister

A ministry of finance is a ministry or other government agency in charge of government finance, fiscal policy, and financial regulation. It is headed by a finance minister, an executive or cabinet position .

A ministry of finance's portfoli ...

, William Thomas White

Sir William Thomas White (13 November 186611 February 1955), was a Canadian politician and Cabinet minister. He served as minister of finance from 1911 to 1919 under Prime Minister Robert Borden. As finance minister, White introduced the inc ...

, rejected calls for direct taxation on Canadian citizens in 1914, though this position would be shortly reversed. White cited his beliefs that taxation would cost too much to implement and would interfere with provincial taxation systems. Borden and White instead opted for "business as usual" with Britain by assuming that the country would cover the costs incurred by Canada. However, at the end of 1914, Britain was not able to lend money to Canada due to their own economic priorities. By 1917, Britain had become unable to pay for wartime shipments from Canada. During the war, Canada drastically increased imports of specialized metals and machinery needed for production of ammunition

Ammunition, also known as ammo, is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. The term includes both expendable weapons (e.g., bombs, missiles, grenades, land mines), and the component parts of oth ...

from the United States. This led Borden and White to successfully negotiate a $50 million loan in New York City in 1915. Canada also succeeded in negotiating larger bond issues in New York in 1916 and 1917. In 1918, a Victory Bond of $300 million brought in $660 million. Overall, Victory Bond campaigns raised around $2 billion. American investment in Canada significantly increased whereas British investment declined. By 1918, imports of goods from the United States were 1,000 percent of British exports to Canada.

In 1915, 1916, and 1917, Borden's government began to reverse their anti-taxation position, not least because of the need for more government revenue. The government introducing wartime savings bonds and raising import tariffs was not enough. In 1915, a luxury tax

A luxury tax is a tax on luxury goods: products not considered essential. A luxury tax may be modeled after a sales tax or VAT, charged as a percentage on all items of particular classes, except that it mainly directly affects the wealthy be ...

on tobacco and alcohol and taxes on transport tickets, telegrams, money orders, cheques, and patent medicines were introduced. By the end of the war, staple items were taxed. In a politically motivated move in 1916, the government introduced the Business Profits War Tax to address increasing concerns about businesses practising war profiteering

A war profiteer is any person or organization that derives unreasonable profit (economics), profit from warfare or by selling weapons and other goods to parties at war. The term typically carries strong negative connotations. General profiteerin ...

. The tax expired in 1920 but was brought back in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

In 1917, Borden's government introduced the income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

which came into effect on September 20, 1917. The tax exempted the first $1,500 of income for single people (unmarried persons and widows and widowers without dependent children); the tax exempted the first $3,000 for everyone else. Single people were taxed at four percent while the tax rate ranged from two to 22 percent for married Canadians with dependents and an annual income over $6,000. Due to its several exemptions, only two to eight percent of Canadians filed tax returns during the early days of the income tax. When the war ended in 1918, $8 million in income tax revenue had been recorded, which was a small fraction of the national net debt of $1.6 billion. Though Borden's government declared the income tax to be temporary, it has remained in place ever since.

In 1917, facing skyrocketing prices, Borden's government established the Board of Grain Supervisors of Canada to distance the marketing of crops grown in 1917 and 1918 away from the private grain companies. It was succeeded by the Canadian Wheat Board

The Canadian Wheat Board () was a marketing board for wheat and barley in Western Canada. Established by the Parliament of Canada on 5 July 1935, its operation was governed by the Canadian Wheat Board Act as a mandatory producer marketing syste ...

for the 1919 crop. The board was dissolved in 1920, despite the concept being popular among farm organizations.

Conscription, Unionist Party, and 1917 election

In Spring 1917, Borden visited Europe and attended theImperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

. There, he participated in discussions that included possible peace terms and helped spearhead the passage of ''Resolution IX'' which called for a post-war constitutional conference to "provide effective arrangements for continuous consultation in all important matters of common Imperial concern, and for such necessary concerted action, founded on consultation, as the several Governments may determine." He also assured leaders of the Allied countries that Canada was committed to the war. Also during his trip, Borden made visits to the hospital to meet wounded and shell shock

Shell shock is a term that originated during World War I to describe symptoms similar to those of combat stress reaction and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which many soldiers suffered during the war. Before PTSD was officially recogni ...

ed soldiers and became determined that the soldiers' sacrifices should not be in vain, and that therefore, the war must end. With volunteer enlistment slowing down, Borden believed that the war should finish through only one method: conscription. Reversing their pledge to not introduce the policy, Borden's government passed the '' Military Service Act'' to introduce conscription. The act became law on August 29, 1917.

The disputes over conscription triggered the Conscription Crisis of 1917

The Conscription Crisis of 1917 () was a political and military crisis in Canada during World War I. It was mainly caused by disagreement on whether men should be conscripted to fight in the war, but also brought out many issues regarding relatio ...

; most English Canadians

English Canadians (), or Anglo-Canadians (), refers to either Canadians of English people, English ethnic origin and heritage or to English-speaking or Anglophone Canadians of any ethnic origin; it is used primarily in contrast with French C ...

supported the policy whereas most French Canadians

French Canadians, referred to as Canadiens mainly before the nineteenth century, are an ethnic group descended from French colonists first arriving in France's colony of Canada in 1608. The vast majority of French Canadians live in the provi ...

opposed it, as seen by protests in Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

. In a bid to settle Quebec opposition towards the policy, Borden proposed forming a wartime coalition government

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an ...

composed of both Conservatives and Liberals. Despite Borden offering the Liberals equal seats in the Cabinet in exchange for Liberal support for conscription, the proposal was rejected by Liberal leader Laurier. In October, Borden formed the Unionist Party, a coalition of Conservatives and pro-conscription Liberals (known as Liberal–Unionists). Laurier, maintaining his anti-conscription position, refused to join the Unionist government and instead created the "Laurier Liberals

Prior to the 1917 Canadian federal election, 1917 federal election in Canada, the Liberal Party of Canada split into two factions. To differentiate the groups, historians tend to use two retrospective names:

* The Laurier Liberals, who opposed ...

", a party of Liberals opposed to conscription.

The 1917 federal election was held on December 17. The election was Canada's first in six years; it was supposed to be held in 1916 due to the constitutional requirement that Parliament last no longer than five years, but was delayed by one year due to the war. Months before the election was called, Borden's government introduced the ''Military Voters Act

The ''Military Voters Act'' () was a 1917 act of the Parliament of Canada. The legislation was passed in 1917 during World War I, giving the right to vote to all Canadian soldiers. The act was significant for swinging the newly enlarged militar ...

'' that allowed all 400,000 conscripted Canadian soldiers — including those who were underage and born in Britain, to vote. The act also allowed current and former Indigenous veterans to vote. In addition, the ''Wartime Elections Act

The Canadian ''Wartime Elections Act'' () was a bill passed on September 20, 1917, by the Conservative government of Robert Borden during the Conscription Crisis of 1917 and was instrumental in pushing Liberals to join the Conservatives in the for ...

'' allowed female relatives of soldiers (excluding Indigenous women) to vote. However, this law confiscated voting rights from German and Austrian immigrants (i.e. immigrants from "enemy nations") who moved to Canada during and after 1902 as well as those who exempted from the coming conscription draft, including conscientious objector

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–indu ...

s. Some believe that these laws put the Unionists in a favourable position.

The Unionist election campaign criticized French Canada for its low enlistment rate to fight in the war. Fearing the possible event of a Liberal victory, one of the Unionist pamphlets highlighted ethnic differences, stating, "the French Canadians who have shirked their duty in this war will be the dominating force in the government of this country. Are the English-speaking people prepared to stand for that?"

The Unionist campaign was an overwhelming success; the government won a powerful majority

A majority is more than half of a total; however, the term is commonly used with other meanings, as explained in the "#Related terms, Related terms" section below.

It is a subset of a Set (mathematics), set consisting of more than half of the se ...

(114 Conservatives and 39 Liberals), won the highest share of the popular vote in Canadian history, and won the largest percentage of seats in Canadian history at the time (at 65.1%). The Liberals on the other hand lost seats and won their smallest share of the popular vote since the 1882 federal election. The election revealed ethnic divides in the country; the Conservatives won over English Canadians whereas the Liberals swept French-Canadian-dominated Quebec.

The process of conscripting soldiers began in January 1918. Only 124,588 out of the 401,882 men who registered for conscription were drafted and only 24,132 actually fought in Europe. By spring 1918, the government removed certain exemptions. To suppress the anti-conscription "Easter Riots" that occurred in Quebec City

Quebec City is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Census Metropolitan Area (including surrounding communities) had a populati ...

between March 28 and April 1, Borden's government used the ''War Measures Act'', invoked martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

, and deployed more than 6,000 troops. The troops and rioters exchanged gunfire, resulting in four civilian deaths and as many as 150 casualties.

Ukrainian Canadian internment

Between 1914 and 1920, more than 8,500Ukrainian Canadians

Ukrainian Canadians are Canadian citizens of Ukrainian descent or Ukrainian-born people who immigrated to Canada.

In the late 19th century, the first Ukrainian immigrants arrived in the east coast of Canada. They were primarily farmers and l ...

were interned under the measures of the ''War Measures Act''. Some immigrated from the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

countries of the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. The internees faced intense labour; they worked in the national parks of Western Canada

Western Canada, also referred to as the Western provinces, Canadian West, or Western provinces of Canada, and commonly known within Canada as the West, is a list of regions of Canada, Canadian region that includes the four western provinces and t ...

, built roads, cleared bush, and cut trails. They also had their personal wealth and property confiscated and never returned by the Borden government. Overall, 107 internees died. Six were shot dead while trying to escape and others died from disease, work-related injuries, and suicide.

Another 80,000 Ukrainian Canadians were not imprisoned but were registered as "enemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any alien native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secur ...

s" and were compelled to report regularly to the police. Their freedom of speech, movement, and association were also restricted.

Borden and the Treaty of Versailles

Throughout the war, Borden stressed the need for Canada to participate in British decisions; in a January 1916 letter to the High Commissioner of Canada in the United Kingdom, George Perley, Borden wrote: On October 27, 1918, British Prime MinisterDavid Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

requested Borden to visit Britain for possible peace talks. Borden replied stating, "the press and the people of this country take it for granted that Canada will be represented at the Peace Conference." World War I ended shortly after on November 11, 1918. Borden told his wife, Laura, that "Canada got nothing out of the war except recognition."

Borden attended the 1919 Paris Peace Conference

Events

January

* January 1

** The Czechoslovak Legions occupy much of the self-proclaimed "free city" of Bratislava, Pressburg (later Bratislava), enforcing its incorporation into the new republic of Czechoslovakia.

** HMY Iolaire, HMY '' ...

, though boycotted the opening ceremony, protesting at the precedence given to William Lloyd, the prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

of the much smaller Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

, over Borden. Convinced that Canada had become a nation on the battlefields of Europe, Borden demanded that it have a separate seat at the Conference. This was initially opposed not only by Britain but also by the United States, which perceived such a delegation as an extra British vote. Borden responded by pointing out that since Canada had lost a far larger proportion of its men compared to the US in the war (although not more in absolute numbers), Canada at least had the right to the representation of a "minor" power. Lloyd George eventually relented, and convinced the reluctant Americans to accept the presence of separate Canadian, Indian, Australian, Newfoundland, New Zealand and South African delegations.MacMillan p.71 Not only did Borden's persistence allow him to represent Canada in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

as a nation, it also ensured that each of the dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

s could sign the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

in its own right and receive a separate membership in the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. Also during the conference, Borden tried to act as an intermediary between the United States and other members of the British Empire delegation, particularly Australia and New Zealand over the issue of the League of Nations Mandate

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing th ...

. Borden also discussed with Lloyd George the possibility of Canada taking over the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

but no agreement was reached.

On May 6, 1919, Borden issued a memorandum calling for Canada, as a member, to have the right to be elected to the League's council. This proposal was accepted by Lloyd George, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, and French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who was Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A physician turned journalist, he played a central role in the poli ...

. These three leaders also included Canada's right to contest for election to the governing body of the International Labour Organization

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is one of the firs ...

. Borden departed Paris on May 11; his Cabinet ministers Charles Doherty and Arthur Sifton

Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton (October 26, 1858 – January 21, 1921) was a Canadian lawyer, judge and politician who served as the second premier of Alberta from 1910 until 1917. He became a minister in the federal cabinet of Canada therea ...

signed the Treaty of Versailles on his behalf.

Domestic policies and post-war Canada

Halifax Explosion

Eleven days before Canadians went to the polls in the 1917 election, Canada experienced the largest domestic disaster in its history: theHalifax Explosion

On the morning of 6 December 1917, the French cargo ship collided with the Norwegian vessel in the harbour of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. ''Mont-Blanc'', laden with Explosive material, high explosives, caught fire and exploded, devastat ...

that killed nearly 1,800 people. The tragedy occurring in his own hometown, Borden pledged that the government would be "co-operating in every way to reconstruct the Port of Halifax: this was of utmost importance to the Empire". Borden helped set up the Halifax Relief Commission that spent $30 million on medical care, repairing infrastructure, and establishing pensions for injured survivors.

Women's suffrage

On May 24, 1918, female citizens 21 and over were granted the right to vote in federal elections. In 1920, Borden's government passed the '' Dominion Elections Act'' to allow women to run for theParliament of Canada

The Parliament of Canada () is the Canadian federalism, federal legislature of Canada. The Monarchy of Canada, Crown, along with two chambers: the Senate of Canada, Senate and the House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons, form the Bicameral ...

. However, these two laws prevented or discouraged Asian Canadian and Indigenous Canadian

Indigenous peoples in Canada (also known as Aboriginals) are the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples within the boundaries of Canada. They comprise the First Nations in Canada, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis#Métis people in ...

women and men from voting.

Nickle Resolution

Despite being knighted himself, Borden disapproved of the process by which Canadians were nominated forhonour

Honour (Commonwealth English) or honor (American English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) is a quality of a person that is of both social teaching and personal ethos, that manifests itself ...

s and in March 1917 drafted a policy stating that all names had to be vetted by the prime minister before the list was sent to Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

. In mid-1917, Borden agreed with MP William Folger Nickle

William Folger Nickle King's Counsel, KC (December 31, 1869 - November 15, 1957) was a Canadians, Canadian politician who served both as a member of the House of Commons of Canada and in the Ontario legislature where he rose to the position o ...

's proposal to abolish Hereditary title

Hereditary titles, in a general sense, are nobility titles, positions or styles that are hereditary and thus tend or are bound to remain in particular families.

Though both monarchs and nobles usually inherit their titles, the mechanisms often d ...

s in Canada. In addition to the abolition of the Hereditary titles, it was later learned that with the exception of military distinctions, honours would not be granted to residents of Canada without the approval or the advice of the Canadian prime minister.

Nationalization of railways

On June 6, 1919, through anorder in council

An Order in Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom, this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' ...

, Borden's government established the Canadian National Railway

The Canadian National Railway Company () is a Canadian Class I freight railway headquartered in Montreal, Quebec, which serves Canada and the Midwestern and Southern United States.

CN is Canada's largest railway, in terms of both revenue a ...

s (CN) as a Crown Corporation

Crown corporation ()

is the term used in Canada for organizations that are structured like private companies, but are directly and wholly owned by the government.

Crown corporations have a long-standing presence in the country, and have a sign ...

. The organization originally consisted of four railways: the Intercolonial Railway

The Intercolonial Railway of Canada , also referred to as the Intercolonial Railway (ICR), was a historic Canada, Canadian railway that operated from 1872 to 1918, when it became part of Canadian National Railways. As the railway was also compl ...

, the Canadian Northern Railway

The Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) was a historic Canada, Canadian transcontinental railway. At its 1923 merger into the Canadian National Railway , the CNoR owned a main line between Quebec City and Vancouver via Ottawa, Winnipeg, and Edmonto ...

, the National Transcontinental Railway

The National Transcontinental Railway (NTR) was a historic railway between Winnipeg, Manitoba, and Moncton, New Brunswick, in Canada. Much of the line is now operated by the Canadian National Railway.

The Grand Trunk partnership

The completion o ...

, and the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was a historic Canadian transcontinental railway running from Fort William, Ontario (now Thunder Bay) to Prince Rupert, British Columbia, a Pacific coast port. East of Winnipeg the line continued as the National ...

. In January 1923, a fifth one was added: the Grand Trunk Railway

The Grand Trunk Railway (; ) was a Rail transport, railway system that operated in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario and in the List of states and territories of the United States, American sta ...

. All five of these railways were financially struggling as a result of their inability to borrow from banks (mainly British) during the First World War.

1919 Winnipeg general strike

After the war, the working class experienced economic hardship. In a bid to address this problem, construction and metal trades workers inWinnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. It is centred on the confluence of the Red River of the North, Red and Assiniboine River, Assiniboine rivers. , Winnipeg h ...

, Manitoba, sought better wages and better working conditions by negotiating with their managers. In May 1919, as a result of talks between the workers and their managers breaking down, several strikes started; on May 15, the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council (WTLC) called for a general strike as a result of the negotiations collapsing. Within hours of the Winnipeg general strike

The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 was one of the most famous and influential strikes in Canadian history. For six weeks, May 15 to June 26, more than 30,000 strikers brought economic activity to a standstill in Winnipeg, Manitoba, which at the ...

breaking out, nearly 30,000 workers resigned.

Afraid that the strike would spark conflicts in other cities, Borden's government intervened. His Cabinet ministers Arthur Meighen

Arthur Meighen ( ; June 16, 1874 – August 5, 1960) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the ninth prime minister of Canada from 1920 to 1921 and from June to September 1926. He led the Conservative Party from 1920 to 1926 and ...

and Gideon Robertson

Gideon Decker Robertson, (August 26, 1874 – August 25, 1933) was a Canadian Senator and Canadian Cabinet minister.

Robertson was a telegrapher by profession and had links with conservatives in the labour movement. In January 1917, he was appo ...

met with the anti-strike Citizens’ Committee but refused to meet with the pro-strike Central Strike Committee. Taking the advice of the Citizens' Committee, Borden's government threatened to fire federal workers unless they returned to work immediately. The government also changed the ''Immigration Act'' to allow the deportation of British-born immigrants. On June 17, the government arrested 10 leaders of the Central Strike Committee and two members of the trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

, One Big Union. On June 21, Borden's government deployed troops from the North-West Mounted Police

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was a Canadian paramilitary police force, established in 1873, to maintain order in the new Canadian North-West Territories (NWT) following the 1870 transfer of Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory to ...

(NWMP) to the strike scene to maintain public order. As a result of the protestors beginning to riot, the NWMP charged at the protestors, beat them with clubs, and fired bullets. Two people were killed and the violent incident became known as " Bloody Saturday". Within days, the strike ended.

Retirement

With his doctors recommending that he should leave politics immediately, Borden told his cabinet on December 16, 1919, that he was going to resign. Some cabinet members begged him to stay in office and take a year-long vacation. Borden took a vacation for an unspecified amount of time and returned to Ottawa in May 1920. Borden announced his retirement to his Unionist caucus onDominion Day

Dominion Day was a day commemorating the granting of certain countries Dominion status — that is, "autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or externa ...

, July 1, 1920. Before he retired, the caucus asked him to choose his successor as leader and prime minister. Borden favoured his Finance Minister William Thomas White

Sir William Thomas White (13 November 186611 February 1955), was a Canadian politician and Cabinet minister. He served as minister of finance from 1911 to 1919 under Prime Minister Robert Borden. As finance minister, White introduced the inc ...

. With White refusing, Borden persuaded cabinet minister Arthur Meighen to succeed him. Meighen succeeded Borden on July 10, 1920. Borden retired from politics altogether in that same month.

After politics (1920–1937)

As a delegate, Borden attended the 1921–1922Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference (or the Washington Conference on the Limitation of Armament) was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, D.C., from November 12, 1921, to February 6, 1922.

It was conducted out ...

. Borden was the Chancellor of Queen's University from 1924 to 1930. He was Vice-President of The Champlain Society between 1923 and 1925 and was the Society's first Honorary President between 1925 and 1937. He also was president of the Canadian Historical Association

The Canadian Historical Association (CHA; , SHC) is a Canadian organization founded in 1922 for the purposes of promoting historical research and scholarship. It is a bilingual, not-for-profit, charitable organization, the largest of its kind in ...

in 1930–31. In 1928 Borden became president of two financial institutions: Barclays Bank

Barclays PLC (, occasionally ) is a British multinational universal bank, headquartered in London, England. Barclays operates as two divisions, Barclays UK and Barclays International, supported by a service company, Barclays Execution Services ...

of Canada and the Crown Life Insurance Company. In 1932 he became chairman of Canada's first mutual fund

A mutual fund is an investment fund that pools money from many investors to purchase Security (finance), securities. The term is typically used in the United States, Canada, and India, while similar structures across the globe include the SICAV in ...

, the Canadian Investment Fund. Even after he stepped down as prime minister, Borden kept in touch with Lloyd George; Borden once told him of his retirement, stating, "There is nothing that oppresses me...books, some business avocation, my wild garden, the birds and the flowers, a little golf, and a great deal of life in the open – these together make up the fullness of my days."

Borden died on June 10, 1937, in Ottawa and is buried in the

Borden died on June 10, 1937, in Ottawa and is buried in the Beechwood Cemetery

Beechwood Cemetery is the national cemetery of Canada, located in Vanier, Ottawa, Ontario. Over 82,000 people are buried in the cemetery, including Governor General Ramon Hnatyshyn, Prime Minister Robert Borden, and several members of Parlia ...

marked by a simple stone cross. In his funeral, a thousand World War I veterans lined the procession route.

Legacy

The Borden government's introduction of conscription, new taxes, and use of the North-West Mounted Police to break up the 1919 Winnipeg general strike are all examples of government intervention; with his emphasis on big government, he is remembered as aRed Tory

A Red Tory is an adherent of a Centre-right politics, centre-right or Paternalistic conservatism, paternalistic-conservative political philosophy derived from the Tory tradition. It is most predominant in Canada; however, it is also found in the ...

. The Canadian War Museum

The Canadian War Museum (CWM) () is a National museums of Canada, national museum on the military history of Canada, country's military history in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The museum serves as both an educational facility on Canadian military hist ...

wrote, "The pressures of war drove Borden’s government to unprecedented levels of involvement in the day-to-day lives of citizens."

Borden's use of conscription in the war remains controversial. While historian J. L. Granatstein wrote, "Canada's military couldn't have carried on without the controversial policy" and that " he conscriptsplayed a critical role in winning the war", he also wrote that "To achieve these ends, he almost broke the nation." In the 1917 federal election, in what was seen as a backlash against Borden and the Unionist Party's pro-conscription position, Quebec voted overwhelmingly in favour of the anti-conscription Laurier Liberals; the Unionists won only three seats. Historian Robert Craig Brown wrote, "The political cost f conscriptionwas enormous: the Conservative Party’s support in Quebec was destroyed and would not be recovered for decades to come."

Borden's opposition towards free trade and his government's reversal of a 1917 campaign promise to exempt the sons of farmers from conscription helped the agrarian Progressive Party grow in popularity, which was dissatisfied with Borden's positions on these issues. The Progressive Party was founded by Thomas Crerar

Thomas Alexander Crerar (17 June 1876 – 11 April 1975) was a western Canadian politician and a leader of the short-lived Progressive Party of Canada. He was born in Molesworth, Ontario, and moved to Manitoba at a young age.

Early career

C ...

, who was Borden's minister of agriculture

An agriculture ministry (also called an agriculture department, agriculture board, agriculture council, or agriculture agency, or ministry of rural development) is a ministry charged with agriculture. The ministry is often headed by a minister f ...

until 1919, when he resigned over his opposition towards high tariffs and his belief that the government's budget did not pay enough attention to farmer's issues. In the 1921 federal election that saw the Conservatives plummet to third place, the Progressives became the second-largest party and swept Western Canada

Western Canada, also referred to as the Western provinces, Canadian West, or Western provinces of Canada, and commonly known within Canada as the West, is a list of regions of Canada, Canadian region that includes the four western provinces and t ...