Sir Barnes Wallis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Barnes Neville Wallis (26 September 1887 – 30 October 1979) was an English

By the time he came to design the

By the time he came to design the

Early in 1942, Wallis began experimenting with skipping marbles over water tanks in his garden, leading to his April 1942 paper " Spherical Bomb – Surface Torpedo". The idea was that a bomb could skip over the water surface, avoiding

Early in 1942, Wallis began experimenting with skipping marbles over water tanks in his garden, leading to his April 1942 paper " Spherical Bomb – Surface Torpedo". The idea was that a bomb could skip over the water surface, avoiding  After the success of the bouncing bomb, Wallis was able to return to his huge bombs, producing first the Tallboy (6 tonnes) and then the Grand Slam (10 tonnes) deep-penetration

After the success of the bouncing bomb, Wallis was able to return to his huge bombs, producing first the Tallboy (6 tonnes) and then the Grand Slam (10 tonnes) deep-penetration

In the 1950s, Wallis developed an experimental rocket-propelled

In the 1950s, Wallis developed an experimental rocket-propelled

In April 1922, Wallis met his cousin-in-law, Molly Bloxam, at a family tea party. She was 17 and he was 34, and her father forbade them from courting. However, he allowed Wallis to assist Molly with her mathematics courses by correspondence, and they wrote some 250 letters, enlivening them with fictional characters such as "Duke Delta X". The letters gradually became personal, and Wallis proposed marriage on her 20th birthday. They were married on 23 April 1925, and remained so for 54 years until his death in 1979.

For 49 years, from 1930 until his death, Wallis lived with his family in

In April 1922, Wallis met his cousin-in-law, Molly Bloxam, at a family tea party. She was 17 and he was 34, and her father forbade them from courting. However, he allowed Wallis to assist Molly with her mathematics courses by correspondence, and they wrote some 250 letters, enlivening them with fictional characters such as "Duke Delta X". The letters gradually became personal, and Wallis proposed marriage on her 20th birthday. They were married on 23 April 1925, and remained so for 54 years until his death in 1979.

For 49 years, from 1930 until his death, Wallis lived with his family in

;Plaques and sculptures

* There is a statue to Wallis, created by American sculptor Tom White in 2008, in

;Plaques and sculptures

* There is a statue to Wallis, created by American sculptor Tom White in 2008, in

Examples of papers from RAF museum

The Papers of Sir Barnes Neville Wallis, Churchill Archives Centre

The Barnes Wallis Memorial Trust

Sir Barnes Wallis

Iain Murray

BBC history page on Barnes Wallis

HEYDAY torpedo

The Development of Rocket-propelled Torpedoes

, by Geoff Kirby (2000) includes HEYDAY.

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wallis, Barnes 1887 births 1979 deaths Military personnel from Derbyshire Burials in Surrey 20th-century English inventors Airship designers Alumni of University of London Worldwide Artists' Rifles soldiers British people of World War II Commanders of the Order of the British Empire English aerospace engineers Fellows of the Royal Aeronautical Society Fellows of the Royal Society Knights Bachelor People educated at Christ's Hospital People from Ripley, Derbyshire Royal Medal winners Scientists of the National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom) Weapons scientists and engineers Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel of World War I Royal Naval Air Service personnel of World War I Royal Navy officers of World War I

engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, build, maintain and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials. They aim to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while ...

and inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea, or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

. He is best known for inventing the bouncing bomb

A bouncing bomb is a bomb designed to bounce to a target across water in a calculated manner to avoid obstacles such as torpedo nets, and to allow both the bomb's speed on arrival at the target and the timing of its detonation to be predeterm ...

used by the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

in Operation Chastise

Operation Chastise, commonly known as the Dambusters Raid, was an attack on Nazi Germany, German dams carried out on the night of 16/17 May 1943 by No. 617 Squadron RAF, 617 Squadron RAF Bomber Command, later called the Dam Busters, using spe ...

(the "Dambusters" raid) to attack the dams of the Ruhr Valley

The Ruhr ( ; , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr Area, sometimes Ruhr District, Ruhr Region, or Ruhr Valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 1,160/km2 and a populatio ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

The raid was the subject of the 1955 film '' The Dam Busters'', in which Wallis was played by Michael Redgrave

Sir Michael Scudamore Redgrave (20 March 1908 – 21 March 1985) was an English actor and filmmaker. Beginning his career in theatre, he first appeared in the West End in 1937. He made his film debut in Alfred Hitchcock's ''The Lady Vanishes'' ...

. Among his other inventions were his version of the geodetic airframe

A geodetic airframe is a type of construction for the airframes of aircraft developed by British aeronautical engineer Barnes Wallis in the 1930s (who sometimes spelt it "geodesic"). Earlier, it was used by Prof. Schütte for the Schütte Lan ...

and the earthquake bomb

The earthquake bomb, or seismic bomb, was a concept that was invented by the British aeronautical engineer Barnes Wallis early in World War II and subsequently developed and used during the war against strategic targets in Europe. A seismic bomb ...

, including designs such as the Tallboy and Grand Slam bombs.

Early life and education

Barnes Wallis was born in Ripley,Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire to the north, Nottinghamshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south-east, Staffordshire to the south a ...

, to general practitioner

A general practitioner (GP) is a doctor who is a Consultant (medicine), consultant in general practice.

GPs have distinct expertise and experience in providing whole person medical care, whilst managing the complexity, uncertainty and risk ass ...

Charles George Wallis (1859–1945) and his wife Edith Eyre (1859–1911), daughter of Rev. John Ashby. The Wallis family subsequently moved to New Cross

New Cross is an area in south-east London, England, south-east of Charing Cross in the London Borough of Lewisham and the London_postal_district#List_of_London_postal_districts, SE14 postcode district. New Cross is near St Johns, London, St Jo ...

, south London, living in "straitened, genteel circumstances" after Charles Wallis was crippled by polio

Poliomyelitis ( ), commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 75% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe ...

in 1893. He was educated at Christ's Hospital

Christ's Hospital is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English Private schools in the United Kingdom, fee-charging boarding school for pupils aged 11–18) with a royal charter, located to the south of Horsham in West Sussex.

T ...

in Horsham

Horsham () is a market town on the upper reaches of the River Arun on the fringe of the Weald in West Sussex, England. The town is south south-west of London, north-west of Brighton and north-east of the county town of Chichester. Nearby to ...

and Haberdashers' Aske's Hatcham Boys' Grammar School in southeast London, leaving school at seventeen to start work in January 1905 at Thames Engineering Works at Blackheath, southeast London. He subsequently changed his apprenticeship to J. Samuel White

J. Samuel White was a British shipbuilding firm based in Cowes, taking its name from John Samuel White (1838–1915).

It came to prominence during the Victorian era. During the 20th century it built destroyers and other naval craft for both the ...

's, the shipbuilders based at Cowes

Cowes () is an England, English port, seaport town and civil parish on the Isle of Wight. Cowes is located on the west bank of the estuary of the River Medina, facing the smaller town of East Cowes on the east bank. The two towns are linked b ...

on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

. He originally trained as a marine engineer and in 1922 he took a degree in engineering via the University of London External Programme

The University of London Worldwide (previously called the University of London International Academy) is the central academic body that manages external study programmes within the collegiate university, federal University of London. All courses ...

.

Aircraft and geodetic construction

Wallis left J. Samuel White's in 1913 when an opportunity arose for him as anaircraft designer

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is s ...

, at first working on airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

s and later aeroplanes

An airplane (American English), or aeroplane (Commonwealth English), informally plane, is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, ...

. He joined Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in 18 ...

– later part of Vickers-Armstrongs

Vickers-Armstrongs Limited was a British engineering conglomerate formed by the merger of the assets of Vickers Limited and Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Company in 1927. The majority of the company was nationalised in the 1960s and 1970s, w ...

and then part of the British Aircraft Corporation

The British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) was a British aircraft manufacturer formed from the government-pressured merger of English Electric, English Electric Aviation Ltd., Vickers-Armstrongs, Vickers-Armstrongs (Aircraft), the Bristol Aeroplane ...

– and worked for them until his retirement in 1971. There he worked on the Admiralty's first rigid airship HMA No. 9r under H. B. Pratt, helping to nurse it though its political stop-go career and protracted development. The first airship of his own design, the R80, incorporated many technical innovations and flew in 1920.Morpurgo (1972).

By the time he came to design the

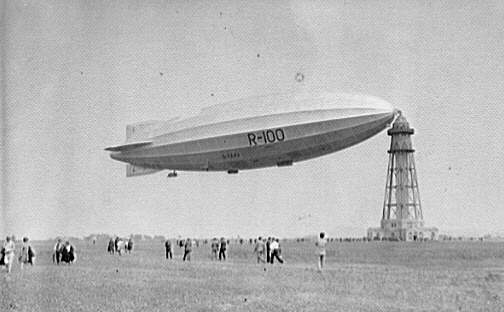

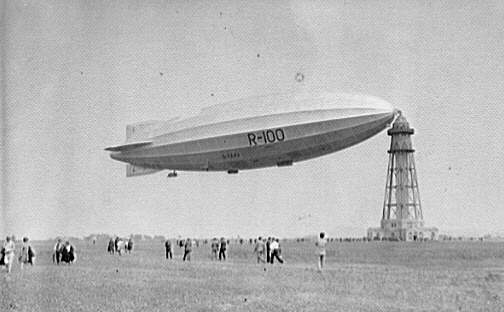

By the time he came to design the R100

His Majesty's Airship R100 was a privately designed and built British rigid airship made as part of a two-ship competition to develop a commercial airship service for use on British Empire routes as part of the Imperial Airship Scheme. The o ...

, the airship for which he is best known, in 1930 he had developed his revolutionary geodetic

Geodesy or geodetics is the science of measuring and representing the geometry, gravity, and spatial orientation of the Earth in temporally varying 3D. It is called planetary geodesy when studying other astronomical bodies, such as planets ...

construction (also known as geodesic), which he applied to the gasbag framing. He also pioneered, along with John Edwin Temple, the use of light alloy and production engineering in the structural design of the R100. Nevil Shute Norway

Nevil Shute Norway (17 January 189912 January 1960) was an English novelist and aeronautical engineer who spent his later years in Australia. He used his full name in his engineering career and Nevil Shute as his pen name to protect his enginee ...

, later to become a writer under the name of Nevil Shute, was the chief calculator for the project, responsible for calculating the stresses on the frame.

Despite a better-than-expected performance and a successful return flight to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

in 1930, the R100 was broken up following the crash near Beauvais

Beauvais ( , ; ) is a town and Communes of France, commune in northern France, and prefecture of the Oise Departments of France, département, in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, north of Paris.

The Communes of France, commune o ...

in northern France of its "sister" ship, the R101

R101 was one of a pair of British rigid airships completed in 1929 as part of the Imperial Airship Scheme, a British government programme to develop civil airships capable of service on long-distance routes within the British Empire. It was d ...

(which was designed and built by a team from the Government's Air Ministry). The later destruction of the ''Hindenburg'' led to the abandonment of airships as a mode of mass transport.

By the time of the R101 crash, Wallis had moved to the Vickers aircraft factory at the Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfields, ...

motor circuit and aerodrome between Byfleet

Byfleet is a village in Surrey, England. It is located in the far east of the borough of Woking, around east of West Byfleet, from which it is separated by the M25 motorway and the Wey Navigation.

The village is of medieval origin. Its win ...

and Weybridge

Weybridge () is a town in the Borough of Elmbridge, Elmbridge district in Surrey, England, around southwest of central London. The settlement is recorded as ''Waigebrugge'' and ''Weibrugge'' in the 7th century and the name derives from a cro ...

in Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

. The prewar aircraft designs of Rex Pierson

Reginald Kirshaw "Rex" Pierson CBE (9 February 1891 – 10 January 1948) was an English aircraft designer and chief designer at Vickers Limited later Vickers-Armstrongs Aircraft Ltd. He was responsible for the Vickers Vimy, a heavy bomber de ...

, the Wellesley, the Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

and the later Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon, Warwickshire, River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined wit ...

and Windsor all employed Wallis's geodetic design in the fuselage and wing structures.

The Wellington had one of the most robust airframes ever developed, and pictures of its skeleton largely shot away, but still sound enough to bring its crew home safely, are still impressive. The geodetic construction offered a light and strong airframe (compared to conventional designs), with clearly defined space within for fuel tanks, payload and so on. However the technique was not easily transferred to other aircraft manufacturers, nor was Vickers able to build other designs in factories tooled for geodetic work.

Bombs

After the outbreak of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in Europe in 1939, Wallis saw a need for strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a systematically organized and executed military attack from the air which can utilize strategic bombers, long- or medium-range missiles, or nuclear-armed fighter-bomber aircraft to attack targets deemed vital to the enemy' ...

to destroy the enemy's ability to wage war and he wrote a paper titled "A Note on a Method of Attacking the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

". Referring to the enemy's power supplies, he wrote (as Axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

3): "If their destruction or paralysis can be accomplished they offer a means of rendering the enemy utterly incapable of continuing to prosecute the war". As a means to do this, he proposed huge bombs that could concentrate their force and destroy targets which were otherwise unlikely to be affected. Wallis's first super-large bomb design came out at some ten tons, far more than any current bomber could carry. Rather than drop the idea, this led him to suggest a plane that could carry it – the "Victory Bomber

The British "Victory Bomber" was a Second World War design proposal by British inventor and aircraft designer Barnes Wallis while at Vickers-Armstrongs for a large strategic bomber. This aircraft was to have performed what Wallis referred to as ...

".

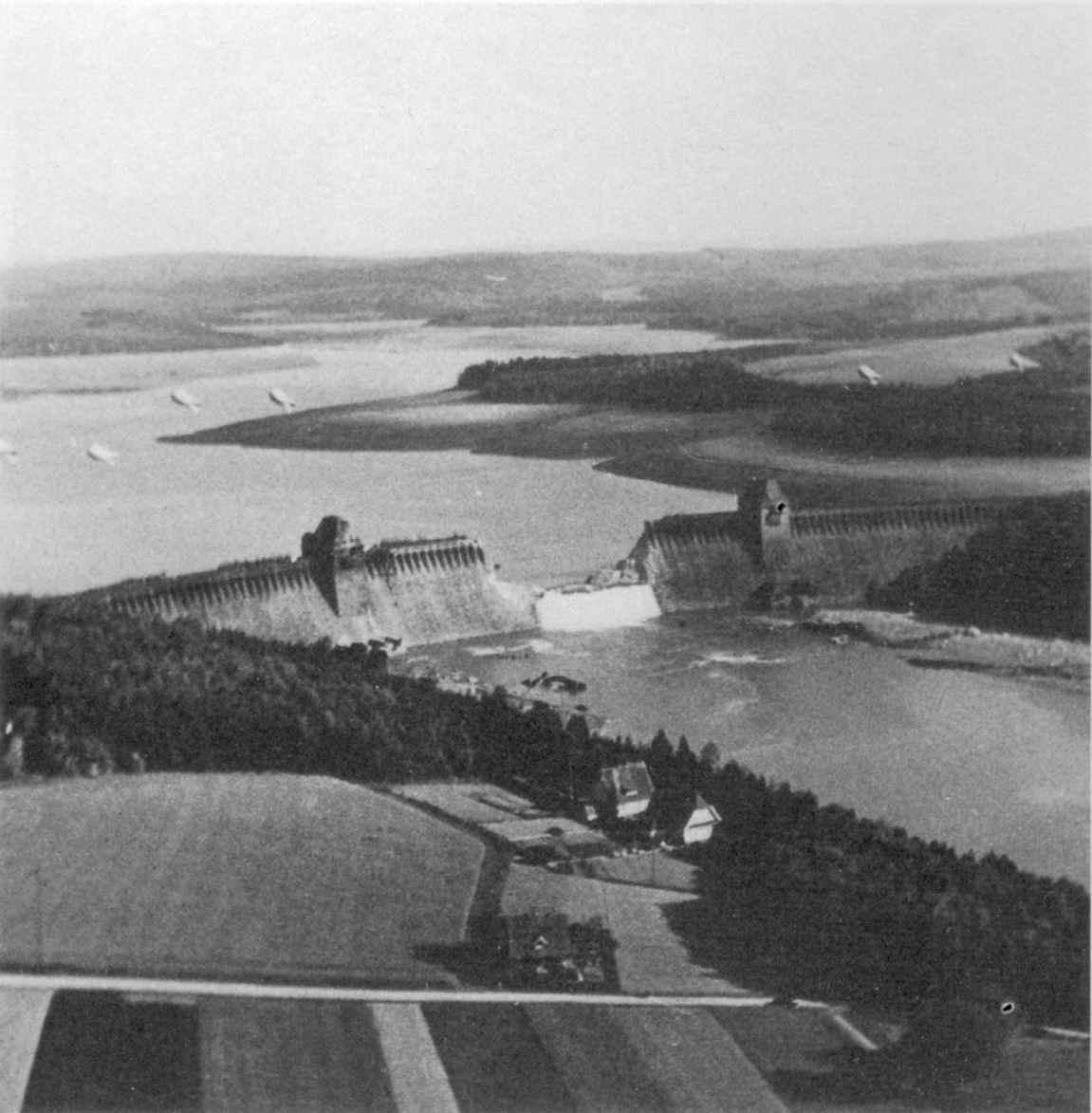

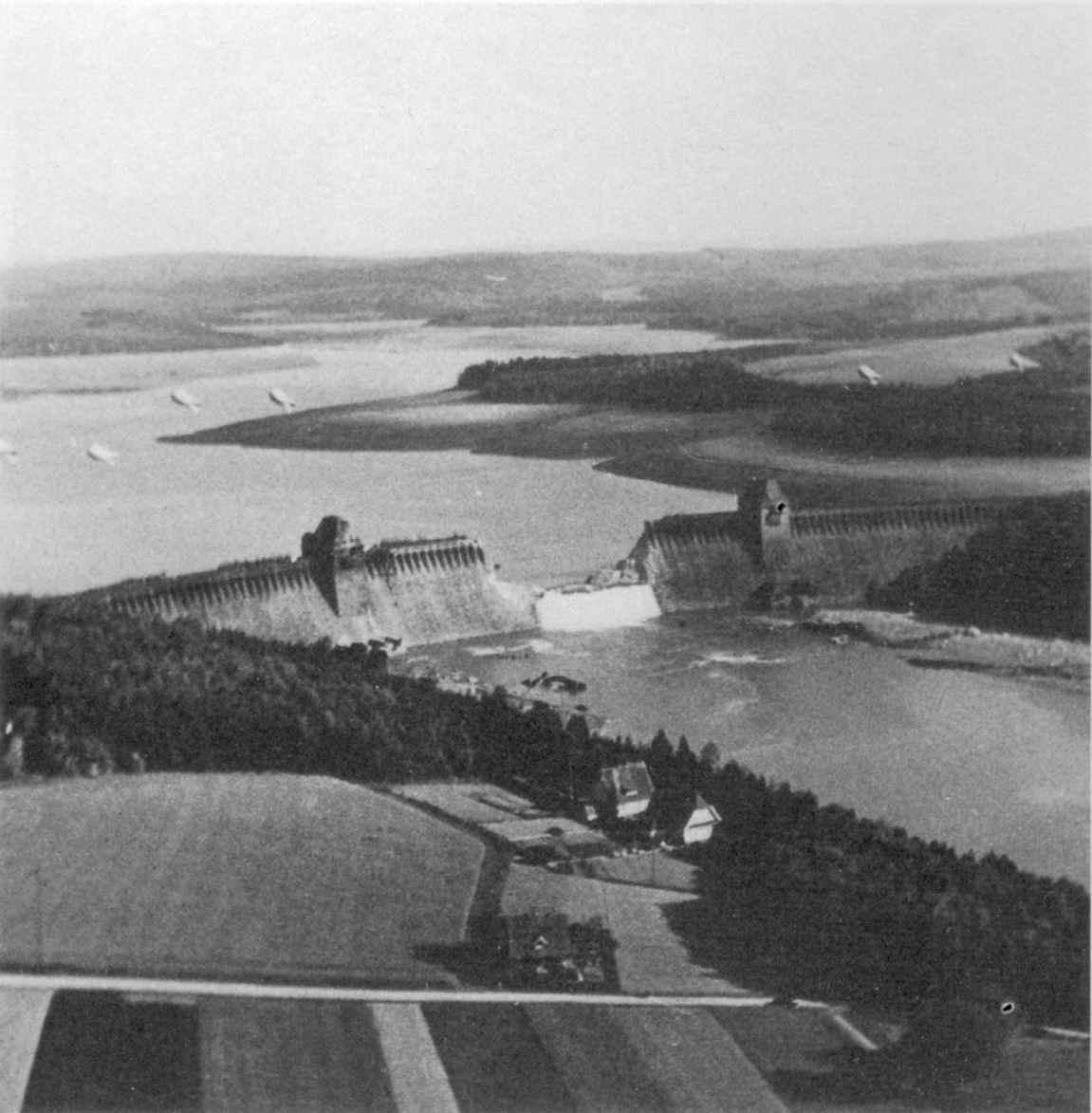

Early in 1942, Wallis began experimenting with skipping marbles over water tanks in his garden, leading to his April 1942 paper " Spherical Bomb – Surface Torpedo". The idea was that a bomb could skip over the water surface, avoiding

Early in 1942, Wallis began experimenting with skipping marbles over water tanks in his garden, leading to his April 1942 paper " Spherical Bomb – Surface Torpedo". The idea was that a bomb could skip over the water surface, avoiding torpedo nets

Torpedo nets were a passive ship defensive device against torpedoes. They were in common use from the 1890s until the World War II, Second World War. They were superseded by the anti-torpedo bulge and torpedo belts.

Origins

With the introduction ...

, and sink directly next to a battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

or dam wall as a depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon designed to destroy submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited ...

, with the surrounding water concentrating the force of the explosion on the target.

A crucial innovation was to spin the bomb. The spin direction determined the number of bounces/range of the bomb. A change to backspin (rather than top-spin), was put forward by another Vickers designer, George Edwards, based on his knowledge as a cricketer. Spin caused the bomb to trail behind the dropping aircraft (decreasing the chance of that aircraft being damaged by the force of the explosion below), increased the range of the bomb, and also prevented it from moving away from the target wall as it sank. After some initial scepticism, the Air Force accepted Wallis's bouncing bomb

A bouncing bomb is a bomb designed to bounce to a target across water in a calculated manner to avoid obstacles such as torpedo nets, and to allow both the bomb's speed on arrival at the target and the timing of its detonation to be predeterm ...

(codenamed ''Upkeep'') for attacks on the Möhne

The Möhne () is a river in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is a right tributary of the Ruhr. The Möhne passes the towns of Brilon, Rüthen

Rüthen () is a town in the district of Soest, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Geography

Rü ...

, Eder and Sorpe dams in the Ruhr area

The Ruhr ( ; , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr Area, sometimes Ruhr District, Ruhr Region, or Ruhr Valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 1,160/km2 and a populati ...

.

The raid on these dams in May 1943 (Operation ''Chastise'') was immortalised in Paul Brickhill

Paul Chester Jerome Brickhill (20 December 191623 April 1991) was an Australian fighter pilot, prisoner of war, and author who wrote '' The Great Escape'', '' The Dam Busters'', and ''Reach for the Sky''.

Early life

Brickhill was born in Melbou ...

's 1951 book '' The Dam Busters'' and the 1955 film of the same name. The Möhne and Eder dams were successfully breached, causing damage to German factories and disrupting hydro-electric power

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies 15% of the world's electricity, almost 4,210 TWh in 2023, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and also ...

.

After the success of the bouncing bomb, Wallis was able to return to his huge bombs, producing first the Tallboy (6 tonnes) and then the Grand Slam (10 tonnes) deep-penetration

After the success of the bouncing bomb, Wallis was able to return to his huge bombs, producing first the Tallboy (6 tonnes) and then the Grand Slam (10 tonnes) deep-penetration earthquake bomb

The earthquake bomb, or seismic bomb, was a concept that was invented by the British aeronautical engineer Barnes Wallis early in World War II and subsequently developed and used during the war against strategic targets in Europe. A seismic bomb ...

s. These were not the same as the 5-tonne " blockbuster" bomb, which was a conventional blast bomb.

Although there was still no aircraft capable of lifting these two bombs to their optimal release altitude, they could be dropped from a lower height, entering the earth at supersonic speed and penetrating to a depth of 20 metres before exploding. They were used on strategic German targets such as V-2

The V2 (), with the technical name '' Aggregat-4'' (A4), was the world's first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was developed during the Second World War in Nazi Germany as a " ven ...

rocket launch sites, the V-3 supergun bunker, submarine pen

A submarine pen (''U-Boot-Bunker'' in German) is a type of submarine base that acts as a bunker to protect submarines from air attack.

The term is generally applied to submarine bases constructed during World War II, particularly in Germany and ...

s and other reinforced structures, large civil constructions such as viaducts and bridges, as well as the German battleship ''Tirpitz''. They were the forerunners of modern bunker-busting bombs.

Post-war research

Aircraft design

Having been dispersed with the Design Office from Brooklands to the nearby Burhill Golf Club inHersham

Hersham is a suburban village in Surrey, within the M25 and the Greater London Built-up Area. It has a mixture of low and high rise housing and has four technology/trading estates. Hersham is contiguous with Walton-on-Thames, its post town, t ...

, after the Vickers factory was badly bombed in September 1940, Wallis returned to Brooklands in November 1945 as head of the Vickers-Armstrongs Research & Development Department which was based in the former motor circuit's 1907 clubhouse. Here he and his staff worked on many futuristic aerospace projects including supersonic flight and "swing-wing" technology (later used in the Panavia Tornado

The Panavia Tornado is a family of twin-engine, variable-sweep wing multi-role combat aircraft, jointly developed and manufactured by Italy, the United Kingdom and Germany. There are three primary #Variants, Tornado variants: the Tornado IDS ...

and other aircraft types). Following the high death toll of the aircrews involved in the Dambusters raid, he made a conscious effort never again to endanger the lives of his test pilots. His designs were extensively tested in model form, and consequently he became a pioneer in the remote control

A remote control, also known colloquially as a remote or clicker, is an consumer electronics, electronic device used to operate another device from a distance, usually wirelessly. In consumer electronics, a remote control can be used to operat ...

of aircraft.

A massive Stratosphere Chamber (which was the world's largest facility of its type) was designed and built beside the clubhouse by 1948. It became the focus for much R&D work under Wallis's direction in the 1950s and 1960s, including research into supersonic aerodynamics that contributed to the design of Concorde

Concorde () is a retired Anglo-French supersonic airliner jointly developed and manufactured by Sud Aviation and the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC).

Studies started in 1954, and France and the United Kingdom signed a treaty establishin ...

, before finally closing by 1980. This unique structure was restored at Brooklands Museum

Brooklands Museum is a motoring and aviation museum occupying part of the former Brooklands Motor Course in Weybridge, Surrey, England.

Formally opened in 1991, the museum is operated by the independent Brooklands Museum Trust Ltd, a private l ...

thanks to a grant from the AIM-Biffa fund in 2013 and was officially reopened by Mary Stopes-Roe, Barnes Wallis's daughter, on 13 March 2014.

Although he did not invent the concept, Wallis did much pioneering engineering work to make the swing-wing

A variable-sweep wing, colloquially known as a "swing wing", is an airplane wing, or set of wings, that may be modified during flight, swept back and then returned to its previous straight position. Because it allows the aircraft's shape to ...

functional. He developed the wing-controlled aerodyne, a concept for a tailless aeroplane controlled entirely by wing movement with no separate control surfaces. His " Wild Goose", designed in the late 1940s, was intended to use laminar flow

Laminar flow () is the property of fluid particles in fluid dynamics to follow smooth paths in layers, with each layer moving smoothly past the adjacent layers with little or no mixing. At low velocities, the fluid tends to flow without lateral m ...

, and alongside it he also worked on the Green Lizard cruise missile and the Heston JC.9 manned experimental aeroplane. The "Swallow

The swallows, martins, and saw-wings, or Hirundinidae are a family of passerine songbirds found around the world on all continents, including occasionally in Antarctica. Highly adapted to aerial feeding, they have a distinctive appearance. The ...

" was a supersonic development of Wild Goose, designed in the mid-1950s, which could have been developed for either military or civil applications. Both Wild Goose and Swallow were flight tested as large (30 ft span) flying scale models, based at Predannack in Cornwall. However, despite promising wind tunnel

A wind tunnel is "an apparatus for producing a controlled stream of air for conducting aerodynamic experiments". The experiment is conducted in the test section of the wind tunnel and a complete tunnel configuration includes air ducting to and f ...

and model work, his designs were not adopted. Government funding for "Swallow" was cancelled in the round of cuts following the Sandys Defence White Paper in 1957, although Vickers continued model trials with some support from the RAE.

An attempt to gain American funding led Wallis to initiate a joint NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

-Vickers study. NASA found aerodynamic problems with the Swallow and, informed also by their work on the Bell X-5

The Bell X-5 was the first Fixed-wing aircraft, aircraft capable of Variable-sweep wing, changing the sweep of its wings in flight. It was inspired by the untested wartime Messerschmitt P.1101, P.1101 design of the Germany, German Messerschmitt ...

, settled for a conventional tail which would eventually lead in turn to the TFX program

The United States Air Force and Navy were both seeking new aircraft when Robert McNamara was appointed U.S. Secretary of Defense in January 1961. The aircraft sought by the two armed services shared the need to carry heavy armament and fuel loads ...

me and the General Dynamics F-111

The General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark is a retired supersonic, medium-range, multirole combat aircraft. Production models of the F-111 had roles that included attack (e.g. interdiction), strategic bombing (including nuclear weapons capabiliti ...

. In the UK, Vickers submitted a wing-controlled aerodyne for specification OR.346 for a reconnaissance/strike-fighter-bomber, effectively the TSR-2

The British Aircraft Corporation TSR-2 is a cancelled Cold War strike and reconnaissance aircraft developed by the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC), for the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The TSR-2 was designed ...

specification with added fighter capability. When Maurice Brennan

Maurice Joseph Brennan BSC, MIMechE, FRAes (April 1913 – 18 January 1986) was a British aerospace engineer. His career encompassed the design and development of flying boats before the Second World War to rocket powered fighters after. He ha ...

left Vickers for Folland he worked on the FO.147, a variable-sweep development of the Gnat

GNAT is a free-software compiler for the Ada programming language which forms part of the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC). It supports all versions of the language, i.e. Ada 2012, Ada 2005, Ada 95 and Ada 83. Originally its ...

lightweight fighter-trainer, offering both tailed and tailless options. Wallis's ideas were ultimately passed over in the UK in favour of the fixed-wing BAC TSR-2 and Concorde. He was critical of both, believing that swing-wing designs would have been more appropriate. In the mid-1960s, TSR-2 was ignominiously scrapped in favour of the American F-111, which had swing-wings influenced by Wallis's work at NASA, although this order was also subsequently cancelled.

Other work

In the 1950s, Wallis developed an experimental rocket-propelled

In the 1950s, Wallis developed an experimental rocket-propelled torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

codenamed HEYDAY. It was powered by compressed air and hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscosity, viscous than Properties of water, water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usua ...

, and had an unusual streamlined shape designed to maintain laminar flow

Laminar flow () is the property of fluid particles in fluid dynamics to follow smooth paths in layers, with each layer moving smoothly past the adjacent layers with little or no mixing. At low velocities, the fluid tends to flow without lateral m ...

over much of its length. Tests were conducted from Portland Breakwater in Dorset. The only surviving example is on display in the Explosion Museum of Naval Firepower at Gosport

Gosport ( ) is a town and non-metropolitan district with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in Hampshire, England. At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 Census, the town had a population of 70,131 and the district had a pop ...

.

In 1955, Wallis agreed to act as a consultant to the project to build the Parkes Radio Telescope

Parkes Observatory is a radio astronomy observatory, located north of the town of Parkes, New South Wales, Australia. It hosts Murriyang, the 64 m CSIRO Parkes Radio Telescope also known as "The Dish", along with two smaller radio telescopes. T ...

in Australia. Some of the ideas he suggested are the same as or closely related to the final design, including the idea of supporting the dish at its centre, the geodetic structure of the dish and the master equatorial control system. Unhappy with the direction it had taken, Wallis left the project halfway into the design study and refused to accept his £1,000 consultant's fee.

In the 1960s, Wallis also proposed using large cargo submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s to transport oil and other goods, thus avoiding surface weather conditions. Moreover, Wallis's calculations indicated, the power requirements for an underwater vessel were lower than for a comparable conventional ship and they could be made to travel at a much higher speed. He also proposed a novel hull structure which would have allowed greater depths to be reached, and the use of gas turbine engines in a submarine, using liquid oxygen. In the end, nothing came of Wallis's submarine ideas.

During the 1960s and into his retirement, he developed ideas for an "all-speed" aircraft, capable of efficient flight at all speed ranges from subsonic to hypersonic

In aerodynamics, a hypersonic speed is one that exceeds five times the speed of sound, often stated as starting at speeds of Mach 5 and above.

The precise Mach number at which a craft can be said to be flying at hypersonic speed varies, since i ...

.

In the late 1950s, Wallis gave a lecture titled "The strength of England" at Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

, and continued to deliver versions of the talk into the early 1970s, presenting technology and automation as a way to restore Britain's dominance. He advocated nuclear-powered cargo submarines as a means of making Britain immune to future embargoes, and to make it a global trading power. He complained of the loss of aircraft design to the United States, and suggested that Britain could dominate air travel by developing a small supersonic airliner capable of short take-off and landing.

Honours and awards

Wallis became aFellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

in 1945, was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

in 1968, and received an Honorary Doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

from Heriot-Watt University

Heriot-Watt University () is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was established in 1821 as the School of Arts of Edinburgh, the world's first mechanics' institute, and was subsequently granted university status by roya ...

in 1969.

Charity work

Wallis was awarded £10,000 for his war work from theRoyal Commission on Awards to Inventors

A Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors is an occasional Royal Commission of the United Kingdom used to hear patent disputes.

On 6 October 1919 the Commission was convened to hear 11 claims for the invention of the tank; one of the eleven "claim ...

. His grief at the loss of so many airmen in the dams raid was such that Wallis donated the entire sum to his alma mater

Alma mater (; : almae matres) is an allegorical Latin phrase meaning "nourishing mother". It personifies a school that a person has attended or graduated from. The term is related to ''alumnus'', literally meaning 'nursling', which describes a sc ...

Christ's Hospital School

Christ's Hospital is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English Private schools in the United Kingdom, fee-charging boarding school for pupils aged 11–18) with a royal charter, located to the south of Horsham in West Sussex.

T ...

in 1951 to allow them to set up the RAF Foundationers' Trust, assisting the children of RAF personnel killed or injured in action to attend the school. Around this time he also became an almoner

An almoner () is a chaplain or church officer who originally was in charge of distributing money to the deserving poor. The title ''almoner'' has to some extent fallen out of use in English, but its equivalents in other languages are often used f ...

of Christ's Hospital. When he retired from aeronautical work in 1957, he was appointed Treasurer and Chairman of the Council of Almoners of Christ's Hospital, holding the post of Treasurer for nearly 13 years. During this time he oversaw its major reconstruction.

Wallis was an active member of the Royal Air Forces Association

The Royal Air Forces Association, also known as RAF Association or RAFA, is a British registered charity. It provides care and support to serving and retired members of the Air Forces of the British Commonwealth, and to their dependents.

The ...

, the charity that supports the RAF community.

Personal life

In April 1922, Wallis met his cousin-in-law, Molly Bloxam, at a family tea party. She was 17 and he was 34, and her father forbade them from courting. However, he allowed Wallis to assist Molly with her mathematics courses by correspondence, and they wrote some 250 letters, enlivening them with fictional characters such as "Duke Delta X". The letters gradually became personal, and Wallis proposed marriage on her 20th birthday. They were married on 23 April 1925, and remained so for 54 years until his death in 1979.

For 49 years, from 1930 until his death, Wallis lived with his family in

In April 1922, Wallis met his cousin-in-law, Molly Bloxam, at a family tea party. She was 17 and he was 34, and her father forbade them from courting. However, he allowed Wallis to assist Molly with her mathematics courses by correspondence, and they wrote some 250 letters, enlivening them with fictional characters such as "Duke Delta X". The letters gradually became personal, and Wallis proposed marriage on her 20th birthday. They were married on 23 April 1925, and remained so for 54 years until his death in 1979.

For 49 years, from 1930 until his death, Wallis lived with his family in Effingham, Surrey

Effingham is a village in the Borough of Guildford in Surrey, reaching from the gently sloping northern plain to the crest of the North Downs and with a medieval parish church. The village was the home of notable figures, such as Barnes Wallis ...

, and he is now buried at the local St. Lawrence Church together with his wife. His epitaph in Latin reads "Spernit Humum Fugiente Penna" (''Severed from the earth with fleeting wing''), a quotation from Horace Ode III.2.

They had four children – Barnes (1926–2008), Mary (1927–2019), Elisabeth (b. 1933) and Christopher (1935–2006) – and also adopted Molly's sister's children John and Robert McCormick when their parents were killed in an air raid.

His daughter Mary Eyre Wallis later married Harry Stopes-Roe, a son of Marie Stopes

Marie Charlotte Carmichael Stopes (15 October 1880 – 2 October 1958) was a British author, palaeobotanist and campaigner for Eugenic feminism, eugenics and women's rights. She made significant contributions to plant palaeontology and co ...

. His son Christopher Loudon Wallis was instrumental in the restoration of the watermill and its building on the Stanway Estate near Cheltenham

Cheltenham () is a historic spa town and borough adjacent to the Cotswolds in Gloucestershire, England. Cheltenham became known as a health and holiday spa town resort following the discovery of mineral springs in 1716, and claims to be the mo ...

, Gloucestershire.

Wallis was a vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the Eating, consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects as food, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slau ...

and an advocate of animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all Animal consciousness, sentient animals have Moral patienthood, moral worth independent of their Utilitarianism, utility to humans, and that their most basic interests—such as ...

. He became a vegetarian at age 73.

In film and fiction

In the 1955 film '' The Dam Busters'', Wallis was played byMichael Redgrave

Sir Michael Scudamore Redgrave (20 March 1908 – 21 March 1985) was an English actor and filmmaker. Beginning his career in theatre, he first appeared in the West End in 1937. He made his film debut in Alfred Hitchcock's ''The Lady Vanishes'' ...

. Wallis's daughter Elisabeth played the camera technician in the water tank sequence.

Wallis and his development of the bouncing bomb are mentioned by Charles Gray in the 1969 film ''Mosquito Squadron

''Mosquito Squadron'' is a 1969 British war film made by Oakmont Productions, directed by Boris Sagal and starring David McCallum. The raid echoes Operation Jericho, a combined RAF–Maquis (World War II), Maquis raid which freed French prison ...

''.

Wallis appears as a fictionalised character in Stephen Baxter's ''The Time Ships

''The Time Ships'' is a 1995 hard science fiction novel by Stephen Baxter. A canonical sequel to the 1895 novella ''The Time Machine'' by H. G. Wells, it was officially authorized by the Wells estate to mark the centenary of the original's publ ...

'' (though its birthdate is not the same, 1883 instead of 1887, since he says he was eight when the Time Traveller first used his machine), the authorised sequel to ''The Time Machine

''The Time Machine'' is an 1895 dystopian post-apocalyptic science fiction novella by H. G. Wells about a Victorian scientist known as the Time Traveller who travels to the year 802,701. The work is generally credited with the popularizati ...

''. He is portrayed as a British engineer in an alternate history

Alternate history (also referred to as alternative history, allohistory, althist, or simply A.H.) is a subgenre of speculative fiction in which one or more historical events have occurred but are resolved differently than in actual history. As ...

, where the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

does not end in 1918, and Wallis concentrates his energies on developing a machine for time travel

Time travel is the hypothetical activity of traveling into the past or future. Time travel is a concept in philosophy and fiction, particularly science fiction. In fiction, time travel is typically achieved through the use of a device known a ...

. As a consequence, it is the Germans who develop the bouncing bomb

A bouncing bomb is a bomb designed to bounce to a target across water in a calculated manner to avoid obstacles such as torpedo nets, and to allow both the bomb's speed on arrival at the target and the timing of its detonation to be predeterm ...

.

His character and the Second World War research lab are featured in the mystery British television series ''Foyle's War

''Foyle's War'' is a British detective drama television series set during and shortly after the Second World War, created by '' Midsomer Murders'' screenwriter and author Anthony Horowitz and commissioned by ITV after the long-running series ...

'' ( Series four, part 2).

In '' Scarlet Traces: The Great Game'' by Ian Edginton

Ian Edginton is a British comic book writer, known for his work on such titles as ''X-Force'', '' Scarlet Traces'', '' H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds'' and ''Leviathan''.

Career

Ian Edginton is known for his steampunk/alternate history work ...

, he is responsible for the development of the Cavorite

Cavorite is a fictional material first depicted by H. G. Wells in ''The First Men in the Moon'', a 1901 scientific romance. Developed by Cavor, a reclusive physicist, it has the ability to negate the force of gravity, enabling him and a businessma ...

weapon used to win the war on Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

after the departure of Cavor.

Memorials

;Plaques and sculptures

* There is a statue to Wallis, created by American sculptor Tom White in 2008, in

;Plaques and sculptures

* There is a statue to Wallis, created by American sculptor Tom White in 2008, in Herne Bay, Kent

Herne Bay is a seaside town on the north coast of Kent in South East England. It is north of Canterbury and east of Whitstable. It neighbours the ancient villages of Herne and Reculver and is part of the City of Canterbury local government ...

. It is a short distance from Reculver

Reculver is a village and coastal resort about east of Herne Bay on the north coast of Kent in south-east England.

It is in the Wards of the United Kingdom, ward of the same name, in the City of Canterbury district of Kent.

Reculver once o ...

where the bouncing bomb was tested.

* A Red Wheel heritage plaque commemorating Wallis's contribution as "Designer of airships, aeroplanes, the 'Bouncing Bomb' and swing-wing aircraft" was erected by the Transport Trust at Wallis's birthplace in Ripley, Derbyshire

Ripley is a market town and civil parish in the Amber Valley district of Derbyshire, England. It is northeast of Derby, northwest of Heanor, southwest of Alfreton and northeast of Belper. The town is continuous with Heanor, Eastwood, Nottingham ...

, on 31 May 2009.

* A Lewisham Council

Lewisham London Borough Council, also known as Lewisham Council, is the local authority for the London Borough of Lewisham in Greater London, England. It is a London borough council, one of 32 in London. The council has been under Labour major ...

plaque is located at 241 New Cross Road in New Cross, London, where Wallis lived from 1892 to 1909.

* A plaque by the main entrance to the former Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in 18 ...

(now BAE Systems

BAE Systems plc is a British Multinational corporation, multinational Aerospace industry, aerospace, military technology, military and information security company, based in London. It is the largest manufacturer in Britain as of 2017. It is ...

) works in Barrow in Furness

Barrow-in-Furness is a port town and civil parish (as just "Barrow") in the Westmorland and Furness district of Cumbria, England. Historic counties of England, Historically in the county of Lancashire, it was incorporated as a municipal borou ...

, where he was Chief Designer for Vickers Ltd Airship Department.

* A Hillingdon Council memorial is located in Moor Lane, Harmondsworth

Harmondsworth is a village in the London Borough of Hillingdon in the county of Greater London with a short border to the south onto Heathrow Airport, London Heathrow Airport and close to the Berkshire county border. The village has no railway st ...

, at the site where the Road Research Laboratory conducted tests on model dams to assist Barnes Wallis in his development of the bouncing bomb.

* Sculpted busts of Wallis are held by Brooklands Museum and the RAF Club at Piccadilly, London.

;Buildings

* The Student Union Building on the University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public university, public research university in Manchester, England. The main campus is south of Manchester city centre, Manchester City Centre on Wilmslow Road, Oxford Road. The University of Manchester is c ...

North Campus (previously UMIST

The University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST) was a university based in the centre of the city of Manchester in England. It specialised in technical and scientific subjects and was a major centre for Research univer ...

) is named in Wallis's honour; he was awarded lifetime membership of the Students' Union in 1967.

* Nottingham Trent University

Nottingham Trent University (NTU) is a public research university located in Nottingham, England. Its origins date back to 1843 with the establishment of the Nottingham School of Design, Nottingham Government School of Design, which still opera ...

also has a building named after Wallis, on Goldsmith Street.

* QinetiQ

QinetiQ ( as in '' kinetic'') is a British defence technology company headquartered in Farnborough, Hampshire. It operates primarily in the defence, security and critical national infrastructure markets and run testing and evaluation capabili ...

's site in Farnborough, Hampshire

Farnborough is a town located in the Rushmoor district of Hampshire, England. It has a population of around 57,486 as of the 2011 census and is an important centre of aviation, engineering and technology. The town is probably best known for it ...

, includes a building named in Wallis's honour, the former site of the Royal Aircraft Establishment

The Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) was a British research establishment, known by several different names during its history, that eventually came under the aegis of the Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), bef ...

.

* A public house named after Sir Barnes Wallis was located in the town of his birth, Ripley, Derbyshire, before being demolished in January 2022.

* A public house named The Barnes Wallis stood for many years near the railway station in Howden

Howden () is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It lies in the Vale of York to the north of the M62 motorway, M62, on the A614 road about south-east of York and north of Goole, ...

, East Riding of Yorkshire. Wallis was involved in airship work at the airship sheds near Howden in the early part of the 20th century. The building is now a private residence.

;Street names

* There is a Barnes Wallis Drive in Byfleet

Byfleet is a village in Surrey, England. It is located in the far east of the borough of Woking, around east of West Byfleet, from which it is separated by the M25 motorway and the Wey Navigation.

The village is of medieval origin. Its win ...

in Surrey within the former Brooklands aerodrome and motor circuit, also Barnes Wallis Close, Effingham, Surrey

Effingham is a village in the Borough of Guildford in Surrey, reaching from the gently sloping northern plain to the crest of the North Downs and with a medieval parish church. The village was the home of notable figures, such as Barnes Wallis ...

, not far from where he lived.

* Additionally, Barnes Wallis Close in Chickerell, Weymouth, which is within sight of the Fleet Lagoon bounded by Chesil Beach

Chesil Beach (also known as Chesil Bank) in Dorset, England, is one of three major shingle beach structures in Britain.A. P. Carr and M. W. L. Blackley, "Investigations Bearing on the Age and Development of Chesil Beach, Dorset, and the Associ ...

, where Wallis tested the bouncing bomb, and also a Barnes Road which is off Wallis Street in Bradford, West Yorkshire.

* There is a Barnes Wallis Close in Bowerhill, Melksham, Wiltshire.

* There is also a Barnes Wallis Drive in Apley in Telford

Telford () is a town in the Telford and Wrekin borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in Shropshire, England. The wider borough covers the town, its suburbs and surrounding towns and villages. The town is close to the county's eastern b ...

, Shropshire, and Segensworth in Hampshire.

* Barnes Wallis Avenue at Christ's Hospital

Christ's Hospital is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English Private schools in the United Kingdom, fee-charging boarding school for pupils aged 11–18) with a royal charter, located to the south of Horsham in West Sussex.

T ...

.

* Barnes Wallis Way in Churchdown

Churchdown is a large village in Gloucestershire, England, situated between Gloucester and Cheltenham in the south of the Tewkesbury Borough.

The village has two centres. The older (Brookfield or "village") centre is in Church Road near St An ...

, Gloucestershire.

* In Buckshaw Village

Buckshaw Village (often shortened to Buckshaw) is a 21st-century village and industrial area between the towns of Chorley and Leyland in Lancashire, England, developed on the site of the former Royal Ordnance Factory (ROF) Chorley. It had a ...

, Lancashire, a housing estate built on the site of an old Royal Ordnance Factory

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family or royalty

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal ...

, a road is named Barnes Wallis Way.

* A housing estate on the site of RFC Marske in the North Yorkshire village of Marske-by-the-Sea

Marske-by-the-Sea is a village in the civil parish of Saltburn, Marske and New Marske, North Yorkshire, England, between the seaside resorts of Redcar and Saltburn-by-the-Sea.

Marske comprises the wards of Longbeck (shared with New Marske) a ...

is named after Wallis.

;Other

* The Yorkshire Air Museum at Elvington near York has a permanent display of the Dambusters raid including a replica bouncing bomb and the catapult used to skim stones to test the bouncing bomb theory. A brief history of Wallis's work is also part of the display.

* The Scafell Hotel in Rosthwaite, Keswick, has a Barnes Wallis Suite; the hotel was a favourite holiday retreat of his.

* The RAF Manston History Museum, Kent, features a section on Operation Chastise (The Dams Raid) and includes one of the few recovered practice 'Bouncing Bombs' that were tested on a sea range near Herne Bay by Lancaster bombers temporarily based at RAF Manston Airfield.

Archives

TheScience Museum at Wroughton

The Science and Innovation Park is a research and cultural site near Swindon, England. Part of the Science Museum Group, the Park hosts a range of research and development activity, filming and photography projects, storage for culture sector ...

, near Swindon, holds 105 boxes of papers of Barnes Wallis. The papers comprise design notes, photographs, calculations, correspondence and reports relating to Wallis's work on airships, including the R100; geodetic construction of aircraft; the bouncing bomb and deep penetration bombs; the "Wild Goose" and "Swallow" swing-wing aircraft; hypersonic aircraft designs and various outside contracts.

Two boxes of records, containing copies of key aeronautical papers written between 1940 and 1958, are held at the Churchill Archives Centre

The Churchill Archives Centre (CAC) at Churchill College at the University of Cambridge is one of the largest repositories in the United Kingdom for the preservation and study of modern personal papers. It is best known for housing the papers ...

in Cambridge.

Other Barnes Wallis papers are also held at Brooklands Museum

Brooklands Museum is a motoring and aviation museum occupying part of the former Brooklands Motor Course in Weybridge, Surrey, England.

Formally opened in 1991, the museum is operated by the independent Brooklands Museum Trust Ltd, a private l ...

, the Imperial War Museum

The Imperial War Museum (IWM), currently branded "Imperial War Museums", is a British national museum. It is headquartered in London, with five branches in England. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, it was intended to record the civ ...

, London, Newark Air Museum and the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

Museum in Hendon, Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

, and Bristol, Leeds and Oxford universities.

The RAF Museum at Hendon also has a reconstruction of his postwar office at Brooklands.

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * Wood, Derek (1975). ''Project Cancelled''. London: Macdonald and Jane's.External links

Examples of papers from RAF museum

The Papers of Sir Barnes Neville Wallis, Churchill Archives Centre

The Barnes Wallis Memorial Trust

Sir Barnes Wallis

Iain Murray

BBC history page on Barnes Wallis

HEYDAY torpedo

Explosion! Museum of Naval Firepower

The Explosion Museum of Naval Firepower is situated in the former Royal Naval Armaments Depot at Priddy's Hard, in Gosport, Hampshire, England. It now forms part of the National Museum of the Royal Navy.

The museum includes a wide variety of ex ...

.

*The Development of Rocket-propelled Torpedoes

, by Geoff Kirby (2000) includes HEYDAY.

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wallis, Barnes 1887 births 1979 deaths Military personnel from Derbyshire Burials in Surrey 20th-century English inventors Airship designers Alumni of University of London Worldwide Artists' Rifles soldiers British people of World War II Commanders of the Order of the British Empire English aerospace engineers Fellows of the Royal Aeronautical Society Fellows of the Royal Society Knights Bachelor People educated at Christ's Hospital People from Ripley, Derbyshire Royal Medal winners Scientists of the National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom) Weapons scientists and engineers Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve personnel of World War I Royal Naval Air Service personnel of World War I Royal Navy officers of World War I