Sinking Of HMS Victoria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The sinking of HMS ''Victoria'' took place at approximately 15:30 on 22 June 1893, after , the

He ordered speed to be increased to and at about 15:00 ordered a signal to be flown from ''Victoria'' to have the ships in each column turn in succession by 180° inwards towards the other column so that the fleet would reverse its course. However, the normal "tactical" turning circle of the ships had a

He ordered speed to be increased to and at about 15:00 ordered a signal to be flown from ''Victoria'' to have the ships in each column turn in succession by 180° inwards towards the other column so that the fleet would reverse its course. However, the normal "tactical" turning circle of the ships had a

By the time that both captains had ordered the engines on their respective ships reversed, it was too late, and ''Camperdown''s

By the time that both captains had ordered the engines on their respective ships reversed, it was too late, and ''Camperdown''s  Of the crew, 357 were rescued and 358 died. was that day responsible for providing a steam launch for the fleet, so her launch was ready and away within a minute of ''Camperdown'' and ''Victoria'' disengaging. Captain Jenkins had ignored Tryon's order for the rescue boats to turn back, and picked up the greatest number of the survivors. Six bodies were recovered immediately after the sinking, but although a search was instituted during the night and the following days, no more were found. Turkish cavalry searched the beaches, but no bodies were found there, either. The six were buried the following day in a plot of land provided by the Sultan of Turkey just outside Tripoli. 173 injured officers and men were transferred to the cruisers and ''Phaeton'' and taken to Malta. Commander John Jellicoe, the

Of the crew, 357 were rescued and 358 died. was that day responsible for providing a steam launch for the fleet, so her launch was ready and away within a minute of ''Camperdown'' and ''Victoria'' disengaging. Captain Jenkins had ignored Tryon's order for the rescue boats to turn back, and picked up the greatest number of the survivors. Six bodies were recovered immediately after the sinking, but although a search was instituted during the night and the following days, no more were found. Turkish cavalry searched the beaches, but no bodies were found there, either. The six were buried the following day in a plot of land provided by the Sultan of Turkey just outside Tripoli. 173 injured officers and men were transferred to the cruisers and ''Phaeton'' and taken to Malta. Commander John Jellicoe, the

flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the f ...

of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

's Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

, collided with while on fleet manoeuvres in the Eastern Mediterranean

Eastern Mediterranean is a loose definition of the eastern approximate half, or third, of the Mediterranean Sea, often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea.

It typically embraces all of that sea's coastal zones, referring to comm ...

. The collision caused significant damage to ''Victoria''s bow, with a large hole produced causing the ship to rapidly capsize

Capsizing or keeling over occurs when a boat or ship is rolled on its side or further by wave action, instability or wind force beyond the angle of positive static stability or it is upside down in the water. The act of recovering a vessel fr ...

. ''Victoria'' took approximately fifteen minutes to sink, with 358 members of the crew, including Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon, lost in the disaster.

Background

In 1893, theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

saw the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

as a vital sea route between Britain and India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

, under constant threat from the navies of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. The impressive naval force that the British concentrated to protect these sealanes made Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

one of the most powerful in the world. On 22 June 1893, the bulk of the fleet, eleven ironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

s (eight battleships and three large cruisers), were on their annual summer exercises off Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in t ...

in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

(now Lebanon).

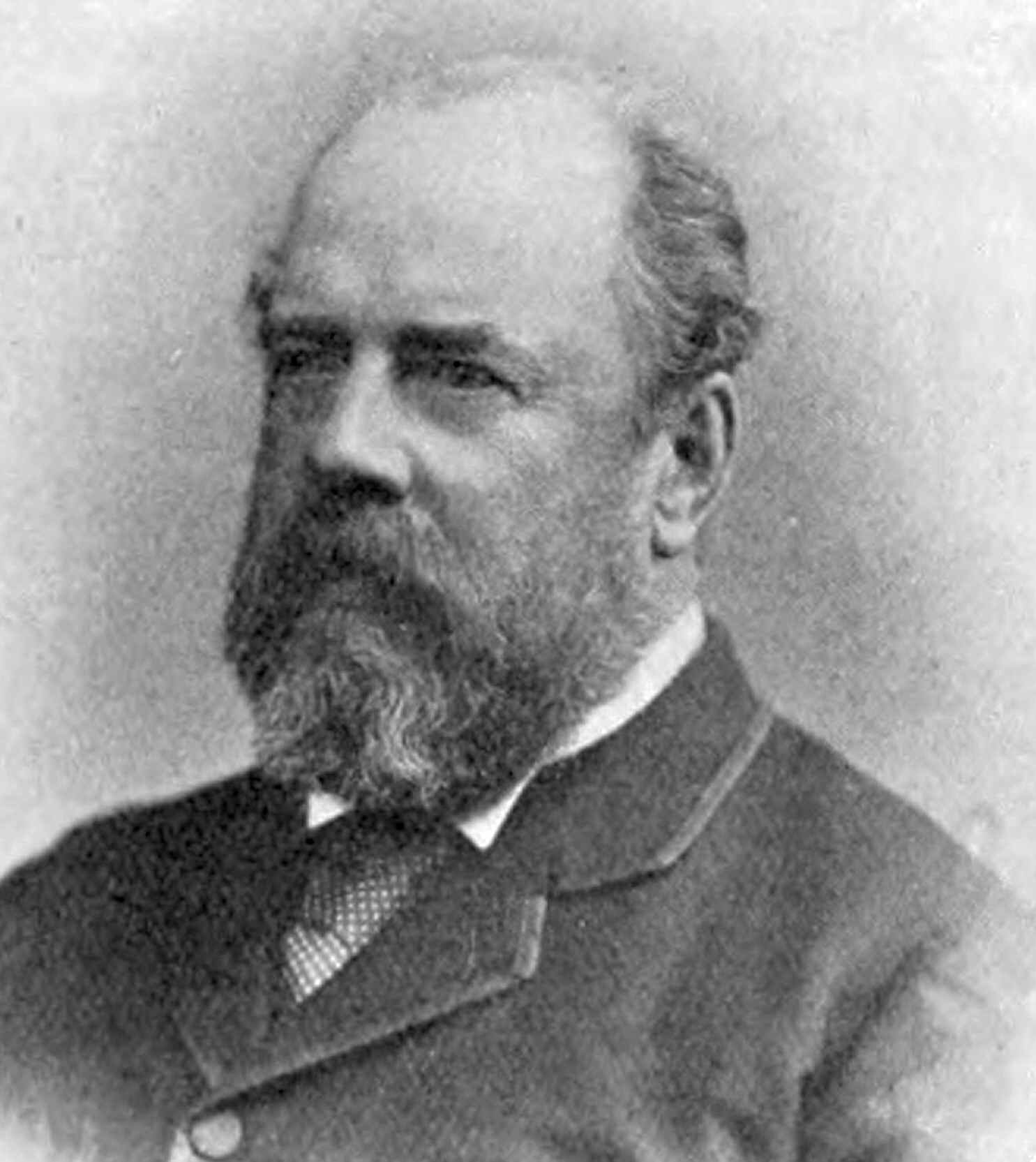

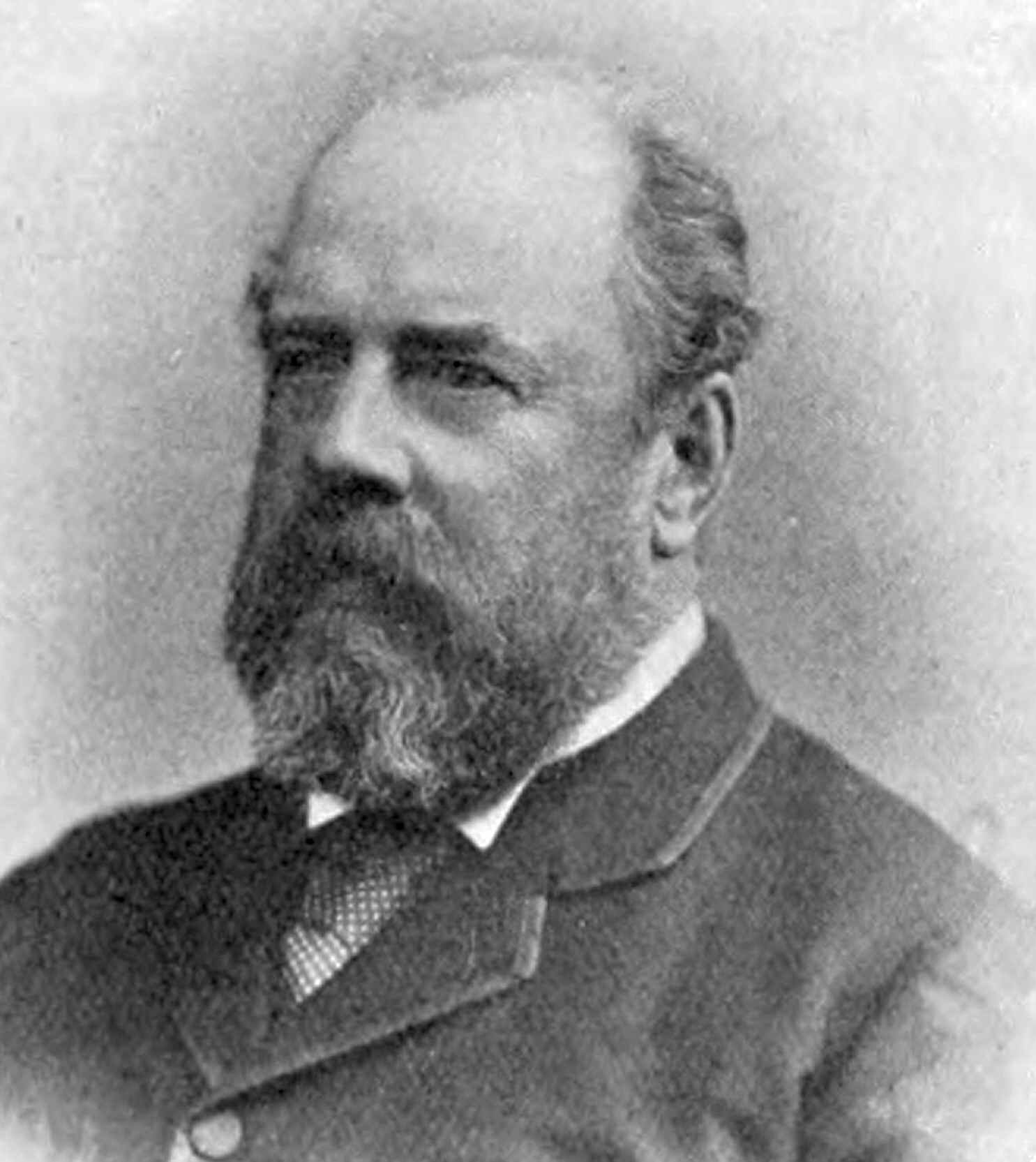

Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon, the commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, was a strict disciplinarian who believed that the best way to keep his crews taut and efficient was by continuous fleet

Fleet may refer to:

Vehicles

*Fishing fleet

*Naval fleet

* Fleet vehicles, a pool of motor vehicles

* Fleet Aircraft, the aircraft manufacturing company

Places

Canada

* Fleet, Alberta, Canada, a hamlet

England

*The Fleet Lagoon, at Chesil Beac ...

evolutions, which before the invention of wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The mos ...

were signalled by signal flags

International maritime signal flags are various flags used to communicate with ships. The principal system of flags and associated codes is the International Code of Signals. Various navies have flag systems with additional flags and codes, and ...

, semaphore

Semaphore (; ) is the use of an apparatus to create a visual signal transmitted over distance. A semaphore can be performed with devices including: fire, lights, flags, sunlight, and moving arms. Semaphores can be used for telegraphy when ar ...

and signal lamp

Signal lamp training during World War II

A signal lamp (sometimes called an Aldis lamp or a Morse lamp) is a semaphore system using a visual signaling device for optical communication, typically using Morse code. The idea of flashing dots and d ...

. He had devised a new system of ship handling intended to depart from the system of flag signalling, which was limited in what could be imparted by whatever was in the existing signal book. His specialty was the "TA" system, which took its name from the signal that would indicate it was in operation. Tryon developed the "TA" system as a means for complex manoeuvres to be handled by only a few simple signals, but which required his ships' captains to use their initiative; upon his flying the flag signal "TA", all ships in the formation were to follow the movements of the flagship without the need to wait for or acknowledge any other signals. However, initiative was a quality that had become blunted by decades of naval peace since Trafalgar, and which was unwelcome in a hierarchical navy that deified Admiral Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought ...

while misunderstanding what he had stood for. A taciturn and difficult man to his subordinate officers, Tryon habitually avoided explaining his intentions to them, to accustom them to handle unpredictable situations.

The collision

In June 1893, the bulk of the Mediterranean Fleet departed Malta for the Eastern Mediterranean to take part in the annual exercises. On 23 June, having anchored atBeirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, the fleet weighed anchor and headed for sea, with the eleven major ships split into two columns, led by the flagships of the fleet commander and his deputy.Disposition of the fleet

Tryon led one column of six ships, which formed the first division of his fleet, in his flagship ''Victoria'' travelling at . His deputy –Rear-Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often regar ...

Albert Hastings Markham

Admiral (Royal Navy), Admiral Sir Albert Hastings Markham (11 November 1841 – 28 October 1918) was a British List of polar explorers, explorer, author, and officer in the Royal Navy. In 1903 he was invested as a Knight Commander of the Orde ...

– was in the lead ship of the second division of five ships, the ''Camperdown''. Markham's normal divisional flagship – – was being refitted. Unusually for Tryon, he had discussed his plans for anchoring the fleet with some of his officers. The two columns were to turn inwards in succession by 180 °, thus closing to and reversing their direction of travel. After travelling a few miles in this formation, the whole fleet would slow and simultaneously turn 90° to port and drop their anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal , used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ''ancora'', which itself comes from the Greek ...

s for the night. The officers had observed that was much too close and suggested that the columns should start at least apart; even this would leave insufficient margin for safety. The normal turning circles of the ships involved would have meant that a gap between the two columns of would be needed to leave a space between the columns of on completion of the manoeuvre. Tryon had confirmed that eight cables

Cable may refer to:

Mechanical

* Nautical cable, an assembly of three or more ropes woven against the weave of the ropes, rendering it virtually waterproof

* Wire rope, a type of rope that consists of several strands of metal wire laid into a hel ...

should be needed for the manoeuvre the officers expected, but had later signalled for the columns to close to six cables . Two of his officers gingerly queried whether the order was what he intended, and he brusquely confirmed that it was.

He ordered speed to be increased to and at about 15:00 ordered a signal to be flown from ''Victoria'' to have the ships in each column turn in succession by 180° inwards towards the other column so that the fleet would reverse its course. However, the normal "tactical" turning circle of the ships had a

He ordered speed to be increased to and at about 15:00 ordered a signal to be flown from ''Victoria'' to have the ships in each column turn in succession by 180° inwards towards the other column so that the fleet would reverse its course. However, the normal "tactical" turning circle of the ships had a diameter

In geometry, a diameter of a circle is any straight line segment that passes through the center of the circle and whose endpoints lie on the circle. It can also be defined as the longest chord of the circle. Both definitions are also valid fo ...

of around each (and a minimum of , although standing orders required "tactical rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw a ...

" to be used in fleet manoeuvres), so if they were less than apart then a collision was likely.

As there was no pre-determined code in the signal book for the manoeuvre he wished to order, Tryon sent separate orders to the two divisions. They were:

"Second division alter course in succession 16 points to starboard preserving the order of the fleet."

"First division alter course in succession 16 points to port preserving the order of the fleet."

The phrase "preserving the order of the fleet" would imply that on conclusion of the manoeuvre the starboard column at the start would still be the starboard at the finish. This theory was propounded in 'The Royal Navy' Vol VII pages 415–426.

It is suggested here that Tryon intended that one division should turn outside the other; as the two columns began apart, turning outside the other, with a turning circle of would have left them at apart. This manoeuvre would have required that the two columns turn at separate times and/or with different speeds, rather than simultaneously with the same speed.

Tryon's flag-lieutenant was Lord Gillford, and it was he who received the fatal order to signal to the two divisions to turn sixteen points (a half circle) inwards, the leading ships first, the others of course following in succession.

Although some of his officers knew what Tryon was planning, they did not raise an objection. Markham, at the head of the other column, was confused by the dangerous order and delayed raising the flag signal indicating that he had understood it. Tryon queried the delay in carrying out his orders, as the fleet was now heading for the shore and needed to turn soon. He ordered a semaphore signal be sent to Markham, asking, "What are you waiting for?" Stung by this public rebuke from his commander, Markham immediately ordered his column to start turning. Various officers on the two flagships confirmed later that they had either assumed or hoped that Tryon would order some new manoeuvre at the last minute.

However, the columns continued to turn towards each other and only moments before the collision did the captains of the two ships appreciate that this was not going to happen. Even then, they still waited for permission to take the action that might have prevented the collision. Tryon's flag captain

In the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime en ...

, Maurice Bourke

Captain Maurice Archibald Bourke (22 December 1853 – 16 September 1900) was a Royal Navy officer who became Naval Secretary.

Naval career

Born the son of Richard Bourke, 6th Earl of Mayo, Bourke joined the Royal Navy in 1867 and advanced to co ...

, asked Tryon three times for permission to order the engines astern; he acted only after he had received that permission. At the last moment, Tryon shouted across to Markham, "Go astern! Go astern!"

''Camperdown'' strikes ''Victoria''

By the time that both captains had ordered the engines on their respective ships reversed, it was too late, and ''Camperdown''s

By the time that both captains had ordered the engines on their respective ships reversed, it was too late, and ''Camperdown''s ram

Ram, ram, or RAM may refer to:

Animals

* A male sheep

* Ram cichlid, a freshwater tropical fish

People

* Ram (given name)

* Ram (surname)

* Ram (director) (Ramsubramaniam), an Indian Tamil film director

* RAM (musician) (born 1974), Dutch

...

struck the starboard side of ''Victoria'' about below the waterline and penetrated into it. The engines were left turning astern, and this caused the ram to be withdrawn and to let in more seawater before all the watertight doors on ''Victoria'' had been closed. Two minutes after the collision, the ships were moving apart.

It was a hot afternoon, and a Thursday, which was traditionally a rest time for the crew. All hatches and means of ventilation were open to cool the ship. There was a hole in the side of the ship open to the sea, but initially, Tryon and his navigation officer, Staff Commander Thomas Hawkins-Smith, did not believe the ship would sink, as the damage was forward and had not affected the engine room or ship's power. Tryon gave orders to turn the ship and head for the shore away so she could be beached. Some of the surrounding ships had launched boats for a rescue, but he signalled for them to turn back. Just two minutes after ''Camperdown'' backed out of the hole she had created, water was advancing over the deck and spilling into the open hatches. A party under Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

Herbert Heath

Admiral Sir Herbert Leopold Heath, (27 December 1861 – 22 October 1954) was a senior officer in the Royal Navy who served as Second Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Personnel from 1917 to 1919.

Military career

Born the son of Vice Admiral Sir Le ...

attempted to unroll a collision mat down the side of the ship to patch the hole and slow the inrush of water, but by the time they could manhandle it into position they were standing in water, and had to abandon the attempt. Five minutes after the collision, the bow had already sunk , the ship was listing heavily to starboard and water was coming through the gun ports in the large forward turret. The foredeck became submerged, with the top of the gun turret forming a small island. Although the engine room was still manned and the engines running, hydraulic power for the helm failed so the ship could not be turned and there was no power to launch the ship's boats. Eight minutes after the collision, the entire fore end of the ship was under water, and the water was lapping the main deck. The stern had risen so that the screws were nearly out of the water.

Immediately after the collision, Captain Bourke had gone below to investigate the damage and close the watertight doors. The engine room was dry, but forward in the ship men were struggling to secure bulkheads even as water washed in around them. Already men had been washed away by incoming water or had been trapped behind closed doors. Yet still there had not been sufficient time to close up the ship to stop the water spreading. He returned on deck and gave orders for the men to fall in. The assembled ranks of sailors were ordered to turn to face the side, and then to abandon ship.

''Victoria'' capsized just 13 minutes after the collision, rotating to starboard with a terrible crash as her boats and anything free fell to the side and as water entering through the funnels caused explosions when it reached the boilers. With her keel uppermost, she slipped into the water bow first, propellers still rotating and threatening anyone near them. Most of the crew managed to abandon ship, although those in the engine room never received orders to leave their posts and were drowned. The ship's chaplain, Rev S. D. Morris RN, was last seen trying to rescue the sick: "In the hour of danger and of death, when all were acting bravely, he was conspicuous for his self-denying and successful efforts to save the sick and to maintain discipline. Nobly forgetful of his own safety, he worked with others to the end, and went down with the vessel ... seeing escape impossible he folded his arms upon his breast, and looking up to heaven, his lips moving in prayer, he died." The area around the wreck became a "widening circle of foaming bubbles, like a giant saucepan of boiling milk", which the rescue boats did not dare enter. Onlookers could only watch as the number of live men in the water steadily diminished. Gunner Frederick Johnson reported being sucked down three times, and said that while originally there were 30–40 people around him, afterwards there were only three or four. Lieutenant Lorin, one of the survivors, stated: "All sorts of floating articles came up with tremendous force, and the surface of the water was one seething mass. We were whirled round and round, and half choked with water, and dashed about amongst the wreckage until half senseless."

''Camperdown'' was also in a serious condition, with her ram nearly wrenched off. Hundreds of tons of water flooded into her bows, and her foredeck went underwater. Her crew had to construct a cofferdam

A cofferdam is an enclosure built within a body of water to allow the enclosed area to be pumped out. This pumping creates a dry working environment so that the work can be carried out safely. Cofferdams are commonly used for construction or re ...

across the main deck to stop the flooding. As with ''Victoria'', the watertight doors had not been closed in time, allowing the ship to flood. After 90 minutes, divers managed to reach and close a bulkhead door so that the flooding could be contained. The ship returned to Tripoli at one quarter speed with seven compartments flooded.

The other ships had more time to take evasive action, and avoided colliding with each other. was already turning to follow ''Victoria'' when the collision happened and came to within of her as she tried to turn away. Some of the surviving witnesses claimed the distance was even less. Similarly, ''Edinburgh'' narrowly avoided running into ''Camperdown'' from behind. ended up stopped some from ''Victoria'', and ''Nile'' away.

Of the crew, 357 were rescued and 358 died. was that day responsible for providing a steam launch for the fleet, so her launch was ready and away within a minute of ''Camperdown'' and ''Victoria'' disengaging. Captain Jenkins had ignored Tryon's order for the rescue boats to turn back, and picked up the greatest number of the survivors. Six bodies were recovered immediately after the sinking, but although a search was instituted during the night and the following days, no more were found. Turkish cavalry searched the beaches, but no bodies were found there, either. The six were buried the following day in a plot of land provided by the Sultan of Turkey just outside Tripoli. 173 injured officers and men were transferred to the cruisers and ''Phaeton'' and taken to Malta. Commander John Jellicoe, the

Of the crew, 357 were rescued and 358 died. was that day responsible for providing a steam launch for the fleet, so her launch was ready and away within a minute of ''Camperdown'' and ''Victoria'' disengaging. Captain Jenkins had ignored Tryon's order for the rescue boats to turn back, and picked up the greatest number of the survivors. Six bodies were recovered immediately after the sinking, but although a search was instituted during the night and the following days, no more were found. Turkish cavalry searched the beaches, but no bodies were found there, either. The six were buried the following day in a plot of land provided by the Sultan of Turkey just outside Tripoli. 173 injured officers and men were transferred to the cruisers and ''Phaeton'' and taken to Malta. Commander John Jellicoe, the executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, ...

of ''Victoria'', who had been bedridden with "Malta fever" for several days, was assisted in the water by Midshipman Philip Roberts-West, and shared the captain's cabin on ''Edgar'' after being rescued.

Tryon himself stayed on the top of the chart-house as the ship sank, accompanied by Hawkins-Smith. Hawkins-Smith survived, but described the force of the sinking and being entangled in the ship's rigging. He thought it doubtful Tryon could have survived, being less fit than himself.

Public response

The news of the accident caused a sensation and appalled the British public at a time when the Royal Navy occupied a prime position in the national consciousness. News was initially scarce, and a crowd of thousands of friends and relatives laid siege to the Admiralty building awaiting news of relatives. Markham's initial telegram to the Admiralty had only named the 22 officers who had drowned, and further details were slow to arrive. Many immediately laid blame on Tryon, as the obvious "scapegoat". Later, as more information reached England, more considered questions arose as to how experienced officers could have carried out such dangerous orders. An appeal was launched in London – championed byAgnes Weston

Dame Agnes Elizabeth Weston, GBE (26 March 1840 – 23 October 1918), also known as Aggie Weston, was an English philanthropist noted for her work with the Royal Navy. For over twenty years, she lived and worked among the sailors of the Royal Na ...

of the Royal Sailors' Rest – which raised £50,000 in three weeks to help the dependants of sailors who had lost their lives.

Of immediate concern was why one of Britain's first-class battleships – one of many of similar design – had sunk from a relatively modest injury when rammed at low speed. Although it was vital to determine exactly what had happened, conducting an inquiry in public was seen as risking the exposure of weaknesses in British ships to enemy navies. (Despite these misgivings, members of the press were eventually permitted to attend the subsequent court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of me ...

.) Although the ram as a weapon of war had already been discontinued by the French and was then under debate as to its effectiveness, it was officially pronounced to be an effective and powerful weapon.

Court martial

A court martial was begun on the deck of atMalta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

on 17 July 1893 to investigate the sinking of ''Victoria'', and to try the conduct of her surviving crew, chief amongst them Captain Bourke. All the crew (except three excused for illness) were required to appear as prisoners before the court. Members of Admiral Tryon's personal staff were not part of the ship's crew and so were not amongst the accused. The court martial was conducted by the new admiral appointed to command the Mediterranean fleet, Sir Michael Culme-Seymour. Seymour had been carefully chosen for the job both of restoring the confidence of the squadron, and as a safe pair of hands to conduct the enquiry. He was a respected admiral at the end of his career and had not expected further appointments. He came from a family which included several naval officers, was related to the First Lord of the Admiralty, his father had been Queen Victoria's chaplain, and he was recommended for the job by his friend Prince Alfred, who was concerned for his other friend Captain Bourke. Prince Alfred also recommended he take on as secretary his own former secretary, Staff Paymaster Henry Hosking Rickard, who was also appointed Deputy Judge Advocate. He had served the same role in previous courts martial, which was to advise on points of law and to impartially sum up the prosecution and defence cases. Captain Alfred Leigh Winsloe, an expert on signals and fleet manoeuvres, was appointed as prosecutor and had travelled out to Malta with the new admiral and his staff. Vice-Admiral Tracey, superintendent of the Malta Dockyard

Malta Dockyard was an important naval base in the Grand Harbour in Malta in the Mediterranean Sea. The infrastructure which is still in operation is now operated by Palumbo Shipyards.

History Pre-1800

The Knights of Malta established dockyard ...

, plus seven of the fleet captains made up the court. A shorthand writer had to be obtained from Central News. Captain Bourke immediately objected that four of the judges were captains of ships which took part in the incident, including the captain of ''Camperdown'', and these were replaced by other officers.

A widespread theory at the time was that Tryon had mistaken the radius of the ship's turning circle for its diameter, and thus had allowed only two cables space instead of four, plus a safety margin of a further two cables between the two columns of ships. Bourke was questioned about this and stated that this explanation had not occurred to him at the time. However, he also begged the court to allow him not to discuss a conversation with Tryon, where he had pointed out before the collision that ''Victoria''s and ''Camperdown''s turning circles were each about , whereas the admiral had ordered the ships to be spaced only apart. Despite Bourke's request not to discuss this point, he raised the matter himself in the court, which had not asked about it. Bourke reported that Tryon had instructed the distance between the ships should remain at six cables, but explained his own inaction in the face of this apparent threat to the ships by saying that he expected Tryon to produce some solution to this apparent mistake at the last minute. Bourke was questioned about Tryon's TA signalling and how this customarily operated. He replied that the admiral would normally go forward during TA, leaving the ships officers aft, whereas otherwise he would remain aft. On this occasion, Tryon had gone forward.

Gillford was called to give evidence, and once again reluctantly told the court that after the collision Tryon had said within his hearing, "It was all my fault". Hawkins-Smith confirmed this, saying he had been on the bridge with Tryon and Gillford after the collision, and had heard Tryon say, "It is entirely my doing, entirely my fault". Hawkins-Smith confirmed to the court that no one believed ''Victoria'' could sink as rapidly as she did. No one was asked whether it might have been wiser for the two ships to have remained wedged together, at least until all watertight doors had been properly secured, before separating them and thereby opening the holes in both ships.

After two more witnesses, Markham was invited to answer questions as a witness, although his status as a potential future defendant meant the court allowed him later to suggest questions to be put to other witnesses. He explained his confusion when he first received the order to turn, and his refusal to signal compliance because he could not see how the manoeuvre could safely be carried out. He observed that he was aware the ships were passing the point at which they should have turned and a response was urgently required. He stated that he had finally complied, after Tryon had queried his delay, having decided that Tryon must intend to turn slowly, outside ''Camperdown''s turn, so the two lines would pass side by side in opposite directions. The two lines would then have reversed, "preserving the order of the fleet" as it had been before the turn. Markham was then read a memorandum circulated by Tryon just before the fleet had sailed which included the instruction: "When the literal obedience to any order, however given, would entail a collision with a friend...paramount orders direct that the danger is to be avoided, while the object of the order should be attained if possible." Markham observed that while he had not been thinking precisely of the memorandum, he had been thinking of the safety of his ship. When it became apparent that he was on a collision course he could not turn further starboard, nor turn to port as this would have broken "the rule of the road", so that the only thing he could do was full reverse. By mischance, only three-quarters reverse had been signalled. It was put to him that he might have turned harder to starboard, thereby avoiding the collision, but he responded again that this would have gone against 'the rule of the road'. When further questioned, he agreed that "the rule of the road" did not apply during manoeuvres. He also confirmed that throughout the turn he had been closely watching ''Victoria''s helm signals, which indicated how sharply she was turning.

Markham's flag captain, Charles Johnstone, was next to be questioned. He initially confirmed that he had only accepted the order to turn once Markham had produced his explanation of how it might be carried out. Later, however, he admitted that at the time he commenced the turn he still did not understand how it might be concluded successfully. He confirmed that ''Camperdown'' had used only 28° of helm instead of the full possible 34°, and had not attempted to turn faster by reversing one of the screws as he might have done. The failure finally to use full reverse in the face of certain collision also remained unexplained. Lieutenant Alexander Hamilton and Lieutenant Barr were both questioned as to what they had heard of conversations amongst the senior officers, making it apparent that confusion continued over what to do at least up to the moment the order to turn was put into effect. Evidence was taken from many other witnesses.

Admiralty technical report

In September 1893 a report was published by the Director of Naval Construction, W. H. White, on how the ship had sunk, and it was submitted to parliament in November. It combined evidence from the survivors with the known design details of the ship. ''Camperdown'' struck approximately from the stem of ''Victoria'' at an angle of approximately 80°, just ahead of one of the main transverse bulkheads. ''Camperdown'' was travelling at about , so the blow roughly equated with the energy of a shell from one of the guns then in service, the 45-ton breech-loading rifle (BLR). It pushed ''Victoria''s bow sideways . ''Camperdown'' was most probably held back from driving further into ''Victoria'' by coming up against the protective armoured deck running across ''Victoria'' below water level. ''Camperdown''s stem penetrated approximately into ''Victoria''s side, while the underwater ram penetrated about , below water level. Had ''Camperdown'' been travelling more slowly, then it was likely the damage from her stem would have been lessened, but the underwater ram might instead have torn a hole along ''Victoria''s relatively thin lower plating as she continued to move forward. A similar thing had happened in a collision between theGerman

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

warships and , causing the latter to sink. This did not happen because the two ships became locked together, although the momentum caused ''Camperdown'' to rotate relative to ''Victoria'', tearing the hole wider.''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ...

'', The Loss of HMS Victoria, 2 November 1893, page 4, issue 34098, column A. (Admiralty minutes confirming the court martial verdict and technical report on the sinking).

After ''Camperdown'' disengaged, the initial inflow of water was limited not by the size of the hole but by the rate at which water could flow out of the immediately affected compartments into adjacent ones. It was noted that there had been insufficient time to close watertight doors, a process which took three or four minutes even when men were on duty and already prepared. The collision was followed by steady sinking of the bow and increasing list to starboard for about 10 minutes, by which time the bow had sunk from its normal height. Approximately half the length of the ship was submerged and the tip of the port propeller was raised above water level instead of below. The ship was heeled over sideways by about 20°. There was then a sudden lurch to starboard and the ship turned over. This was ascribed to water reaching open ports and doors on the gun turret and sides of the ship, which now started to flood new compartments on the starboard side. The ship started to capsize, slowly at first but with increasing speed, accompanied by increasing noise audible on the nearby ships as anything loose fell towards the low side, worsening the process. The ship was still underway at this time trying to reach shore. This tended to force the bow down and more water into the ship, while the rudder jammed hard to starboard tended to increase the heel.

It was estimated from survivor reports that initially twelve watertight compartments were affected, causing a buoyance loss of some at the fore end of the ship, mostly concentrated below the level of the armoured deck. Water then spread to other areas, eventually rising to fill the space below the main deck. There were no significant longitudinal bulkheads in the affected areas, which might have had the effect of keeping water out of the port side and thereby accentuating the heel, but the water naturally flooded the holed side first causing the imbalance. No water entered the stokeholds or engine rooms. It was determined that had the gunports and doors at deck level been closed so that water was prevented from entering this way, then the ship would not have capsized. These doors would customarily be closed if the ship was travelling in heavy seas, but were not part of normal procedure for closure in a collision. She might not have foundered at all, but this would have depended on whether various bulkhead doors had been closed or not, which was unclear. Had all doors been closed initially so that only the breached compartments were flooded, then the ship's deck would have likely remained just above water level with a heel of around 9° and ''Victoria'' would have been able to continue under her own power.

The report denied that had ''Victoria''s side armour extended as far forward as the point of impact that it could have reduced the damage and saved the ship. It denied that automatic bulkhead doors would have helped, although these were shortly fitted to capital ships throughout the navy. It denied the ship was insufficiently stable, although modifications were then undertaken to the bulkhead arrangement of her sister ''Sans Pareil''.

Outcomes

The court produced five findings: *That the collision was due to an order by Admiral Tryon. *That following the accident everything possible had been done to save the ship and preserve life. *No blame attached to Captain Bourke or any other member of his crew. *'The court strongly feel that although it is much to be regretted that Rear Admiral Albert H. Markham did not carry out his first intention of semaphoring to the Commander-in-Chief his doubts as to the signal, it would be fatal to the interests of the service to say that he was to blame for carrying out the directions of the Commander-in-Chief present in person.' *The court was not able to say why ''Victoria'' had capsized. It was established that the ship would have been in no danger had her watertight doors been closed in time. Bourke was found blameless, since the collision was due to Admiral Tryon's explicit order but the judgement carried an implied criticism of Rear-Admiral Markham. Winsloe complained afterwards that he had not been permitted to properly make his case, and that there was more than enough evidence to convict Markham and others of his crew of negligence. Back in England, confusion reigned in the press as to whether the findings about Markham were an indictment or not, and whether or not it was the duty of an officer to disobey a dangerous order. The ''Saturday Review'' commented, "the court has evaded the real point with a slipperiness (for we cannot say dexterity) not wholly worthy of the candour we expect from officers and gentlemen." Captain Gerald Noel of ''Nile'', who had given evidence critical of ''Camperdown''s actions, wrote to Markham observing that things might have turned out better had he been on any ship other than ''Camperdown'', and that in his opinion Captain Johnstone was incompetent.Charles Beresford

Admiral Charles William de la Poer Beresford, 1st Baron Beresford, (10 February 1846 – 6 September 1919), styled Lord Charles Beresford between 1859 and 1916, was a British admiral and Member of Parliament.

Beresford was the second son of ...

and Admiral of the Fleet Sir Geoffrey Phipps Hornby published a joint letter in the ''United Service Gazette'' that: "Admiral Markham might have refused to perform the evolution ordered, and the ''Victoria'' might have been saved. Admiral Markham, however, would have been tried by court-martial, and no one would have sympathised with him as it would not have been realized that he had averted a catastrophe. Unconditional obedience is, in brief, the only principle on which those in service must act." This contrasted with a statement contained in the official signal book; "Although it is the duty of every ship to preserve as correctly as possible the station assigned to her, this duty is not to be held as freeing the captain from the responsibility of taking such steps as may be necessary to avoid any danger to which she is exposed, when immediate action is imperative and time or circumstance do not admit of the Admiral's permission being obtained."

The verdict of the court had to be confirmed by the Admiralty Board in London. They found themselves in a difficulty; although naval opinion seemed to have reached consensus that Markham was significantly to blame, and that it was not acceptable to allow a precedent which any officer causing a disaster by blindly following orders could cite in his defence, it was also felt impossible to severely criticise Markham without blaming Bourke for also failing to take action. As a compromise, a rider was added to the verdict, to the effect that Markham had no justification for his belief that ''Victoria'' would circle around him, and thus he should have taken action much sooner to avoid collision. Captain Johnstone was also criticised, both for failing in his own independent responsibility to safeguard the ships, and for failing to expeditiously carry out orders when the collision was imminent.

Markham and Johnstone both continued to feel aggrieved by the verdict, seeking to take the matter to a further court-martial to clear their names. It fell to Seymour to convince them that they had been dealt with lightly, and any further case could only go against them. Markham completed the remaining months of his posting in the Mediterranean, but was then placed on half pay Half-pay (h.p.) was a term used in the British Army and Royal Navy of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries to refer to the pay or allowance an officer received when in retirement or not in actual service.

Past usage United Kingdom

In the En ...

without a command. He received minor postings and achieved the rank of admiral before retiring aged 65 in 1906.Hough p. 171.

Tryon's TA system – and with it his attempt to restore Nelsonian initiative into the Victorian-era Royal Navy – died with him. Whether or not Tryon had intended the system to be in effect at the time of the accident, traditionalist enemies of the new system used the collision as an excuse to discredit and bury it. To some extent, this was mitigated by the introduction of wireless communication some six years later. Heavy reliance upon detailed signalling – and the ethos of reliance upon precise orders – continued within the navy right through to the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

. Several incidents occurred where reliance upon specific orders or signal failures allowed lucky escapes by the enemy in that war, so that had the sinking not occurred and Tryon survived to continue his campaign, there might have been a significant improvement in British performance.

Five years after the incident, only ''Camperdown'' was still in active service, the rest of the then front-line battleships all having been relegated to guard duties as obsolete.

There is a legend that Tryon's wife was giving a large social party in their London home at the time his ship collided with ''Camperdown'', and that Admiral Tryon was seen descending the staircase by some of the guests.

There is a memorial to the crew killed in the disaster in Victoria Park, Portsmouth

Victoria Park is a public park located just to the north of Portsmouth Guildhall, adjacent to Portsmouth and Southsea railway station and close to the city centre in Portsmouth, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial ...

. It was originally erected in the town's main square, but at the request of survivors was moved to the park in 1903 where it would be better protected.

A scale section of ''Victoria'' – a popular exhibit on display at the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The centerpiece of the Fair, h ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

at the time of the accident – was subsequently draped in black cloth as a tribute to the loss.

In 1908, and were given orders that might have led to a collision, but Rear-Admiral Percy Scott

Admiral Sir Percy Moreton Scott, 1st Baronet, (10 July 1853 – 18 October 1924) was a British Royal Navy officer and a pioneer in modern naval gunnery. During his career he proved to be an engineer and problem solver of some considerable ...

implemented a different course than was ordered, ensuring no risk of collision.

Tryon's intentions

No definite conclusion has ever been reached as to what Tryon intended to happen during the manoeuvre. Two possible explanations have been proposed. The first is that Tryon was mistaken in the orders which he gave. It has variously been suggested that he might have been ill or indisposed in some way, supported by his curt comments to officers who queried him at the time, and his apparent inattention to the results when the manoeuvre commenced. Alternatively, that he was of sound mind, but mistook the turning circle of the ships involved. It has been suggested that a much more frequent manoeuvre was a turn of 90°, for which a space allowance of two cables per ship would have been correct. On this basis, the ships would have completed their turns inwards at a spacing of two cables, then re-traced their course to the correct point to turn to their final anchor positions. Whatever the possible reason for the initial mistake, some confirmation of this explanation comes from the reported statement of Lieutenant Charles Collins, who had been officer of the watch on ''Victoria'' at the time of the incident. Memoirs written by Mark Kerr related that Collins had confirmed to him that Tryon had admitted on the bridge that this was the mistake he had made. Onehistorian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

has gone so far as to suggest that Tryon's incomprehensible letters to Lord Charles Beresford

Admiral Charles William de la Poer Beresford, 1st Baron Beresford, (10 February 1846 – 6 September 1919), styled Lord Charles Beresford between 1859 and 1916, was a British admiral and Member of Parliament.

Beresford was the second son of ...

indicate that he "was suffering from some deterioration of the brain; that his fatal error was no mental aberration such as is to be expected of the young and inexperienced, but the consequence of a disease which at times clouded and confused his judgement and ideas."

The second possibility is that Tryon fully intended the order which he gave and – understanding the objections raised by his officers – still chose to put it into effect. Tryon had ordered an identical manoeuvre during different exercises in 1890, but on that occasion the turn was cancelled because the commander concerned declined to signal an acceptance of the order before it became too late to carry it out (in fact the man who had been in Markham's position on that occasion was Vice-Admiral Tracey, who now sat on the panel). Markham came up with his own suggestion as to how it might be possible to carry out the order, with one line of ships turning outside the other. However, he insisted that he believed Tryon intended to turn outside Markham's ships, despite the navigation signals being flown by ''Victoria'' that she was turning at maximum helm. It has been suggested that unlike Markham's assessment, Tryon intended to take a tight curve and leave it to Markham to avoid him, by taking the outside position around the curve.

Support for this came initially from a journalist and naval historian William Laird Clowes

Sir William Laird Clowes (1 February 1856 – 14 August 1905) was a British journalist and historian whose principal work was ''The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900'', a text that is still in print. He also wrote numerous ...

who suggested that Queen's Regulations

The ''King's Regulations'' (first published in 1731 and known as the ''Queen's Regulations'' when the monarch is female) is a collection of orders and regulations in force in the Royal Navy, British Army, Royal Air Force, and Commonwealth Realm ...

required "If two ships under steam are crossing so as to involve risk of collision, the ship which has the other on its starboard side shall keep out of the way of the other," which would place the onus upon ''Camperdown'' to take avoiding action. Clowes also maintained that in any contention between a ship carrying the commander and another, it was the responsibility of the other ship to keep clear from the path of his commander. Although this particular form of turn was not included in the official manoeuvering book, it was mentioned in other standard texts of seamanship.Hough p. 164. This view has been taken by others, who have added to the argument Tryon's behaviour, which was consistent with his having set a TA problem for his subordinate to solve and therefore followed his normal habit of not explaining his intentions or intervening until afterwards. Others have argued that the witnesses' accounts suggest Tryon accepted having made a mistake, and that had one column of ships passed outside the other instead of both turning inwards, they would then have been in the wrong formation to approach their normal positions at the anchorage. Debate has also centred upon whether the flag signals instructions "...preserving the order of the fleet" imply that afterwards the ships should be in two columns as before (i.e. ''Camperdown'' in the starboard column) or whether the signals only meant that each division should still be in one column with the same order of ships, but that it could have swapped sides with the other column.

Wreck site

After a search that lasted ten years, the wreck was discovered on 22 August 2004 in of water by the Lebanese-Austrian diver Christian Francis, aided by the British diver Mark Ellyatt. She stands vertically with herbow

Bow often refers to:

* Bow and arrow, a weapon

* Bowing, bending the upper body as a social gesture

* An ornamental knot made of ribbon

Bow may also refer to:

* Bow (watercraft), the foremost part of a ship or boat

* Bow (position), the rower ...

and some 30 metres of her length buried in the mud and her stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

pointing directly upwards towards the surface. This position is not unique among shipwrecks as first thought, as the Russian monitor

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West ...

also rests like this. The unusual attitude of this wreck is thought to have been due to the heavy single turret forward containing the main armament coupled with the still-turning propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

s driving the wreck downwards.

The 1949 Ealing comedy

The Ealing comedies is an informal name for a series of comedy films produced by the London-based Ealing Studios during a ten-year period from 1947 to 1957. Often considered to reflect Britain's post-war spirit, the most celebrated films in the ...

''Kind Hearts and Coronets

''Kind Hearts and Coronets'' is a 1949 British crime black comedy film. It features Dennis Price, Joan Greenwood, Valerie Hobson and Alec Guinness; Guinness plays nine characters. The plot is loosely based on the novel ''Israel Rank: The Auto ...

'' features a satire of the accident, in which Alec Guinness

Sir Alec Guinness (born Alec Guinness de Cuffe; 2 April 1914 – 5 August 2000) was an English actor. After an early career on the stage, Guinness was featured in several of the Ealing comedies, including '' Kind Hearts and Coronets'' (1 ...

plays Admiral Lord Horatio D'Ascoyne, who orders a manoeuvre that causes his flagship to be rammed and sunk by another ship in his fleet. Guinness noted that his portrayal of the admiral was based on an officer he knew during his training during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.References

Bibliography

* * Andrew Gordon, ''The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command'', John Murray. *Richard Hough, ''Admirals in Collision'', Hamish Hamilton, London. Copyright 1959. {{1893 shipwrecks Maritime incidents in 1893 June 1893 events Ships sunk in collisionsVictoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...