Sheba on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sheba, or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdom that existed in

Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

from to . Its inhabitants were the Sabaeans, who, as a people, were indissociable from the kingdom itself for much of the 1st millennium BCE. Modern historians agree that the heartland of the Sabaean civilization was located in the region around Marib

Marib (; Ancient South Arabian script, Old South Arabian: 𐩣𐩧𐩨/𐩣𐩧𐩺𐩨 ''Mryb/Mrb'') is the capital city of Marib Governorate, Yemen. It was the capital of the ancient kingdom of ''Saba’, Sabaʾ'' (), which some scholars beli ...

and Sirwah. In some periods, they expanded to much of modern Yemen and even parts of the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

, particularly Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

. The kingdom's native language was Sabaic

Sabaic, sometimes referred to as Sabaean, was a Old South Arabian, Sayhadic language that was spoken between c. 1000 BC and the 6th century AD by the Sabaeans. It was used as a written language by some other peoples of the ancient civilization of ...

, which was a variety of Old South Arabian

Ancient South Arabian (ASA; also known as Old South Arabian, Epigraphic South Arabian, Ṣayhadic, or Yemenite) is a group of four closely related extinct languages ( Sabaean/Sabaic, Qatabanic, Hadramitic, Minaic) spoken in the far southern ...

.Stuart Munro-Hay

Stuart Christopher Munro-Hay (21 April 1947 – 14 October 2004) was a British archaeologist, numismatist and Ethiopianist. He studied the culture and history of ancient Ethiopia, the Horn of Africa region and South Arabia, particularly their his ...

, ''Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity'', 1991.

Among South Arabians and Abyssinians, Sheba's name carried prestige, as it was widely considered to be the birthplace of South Arabian civilization as a whole. The first Sabaean kingdom lasted from the 8th century BCE to the 1st century BCE: this kingdom can be divided into the "mukarrib

Mukarrib (Old South Arabian: , romanized: ) is a title used by rulers in ancient South Arabia. It is attested as soon as continuous epigraphic evidence is available and it was used by the kingdoms of Saba, Hadhramaut, Qataban, and Awsan. The tit ...

" period, where it reigned supreme over all of South Arabia; and the "kingly" period, a long period of decline to the neighbouring kingdoms of Ma'in

Ma'in (; ) was an ancient South Arabian kingdom in modern-day Yemen. It was located along the strip of desert called Ramlat al-Sab'atayn, Ṣayhad by medieval Arab geographers, which is now known as Ramlat al-Sab'atayn. Wadd was the national ...

, Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah and Mahrah, Dhofar in southwestern Oman, and Sharurah in the Najran Province of Saudi A ...

, and Qataban

Qataban () was an ancient Yemenite kingdom in South Arabia that existed from the early 1st millennium BCE to the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.

It was one of the six ancient South Arabian kingdoms of ancient Yemen, along with Sabaʾ, Maʿīn ...

, ultimately ending when a newer neighbour, Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

, annexed them. Sheba was originally confined to the region of Marib (its capital city) and its surroundings. At its height, it encompassed much of the southwestern parts of the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

before eventually declining to the regions of Marib. However, it re-emerged from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE. During this time, a secondary capital was founded at Sanaa

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

, which is also the capital city of modern Yemen. Around 275 CE, the Sabaean civilization came to a permanent end in the aftermath of another Himyarite annexation.

The Sabaeans, like the other South Arabian kingdoms of their time, took part in the extremely lucrative spice trade

The spice trade involved historical civilizations in Asia, Northeast Africa and Europe. Spices, such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric, were known and used in antiquity and traded in t ...

, especially including frankincense

Frankincense, also known as olibanum (), is an Aroma compound, aromatic resin used in incense and perfumes, obtained from trees of the genus ''Boswellia'' in the family (biology), family Burseraceae. The word is from Old French ('high-quality in ...

and myrrh

Myrrh (; from an unidentified ancient Semitic language, see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a few small, thorny tree species of the '' Commiphora'' genus, belonging to the Burseraceae family. Myrrh resin has been used ...

. They left behind many inscriptions in the monumental Ancient South Arabian script

The Ancient South Arabian script (Old South Arabian: ; modern ) branched from the Proto-Sinaitic script in about the late 2nd millennium BCE, and remained in use through the late sixth century CE. It is an abjad, a writing system where only con ...

, as well as numerous documents in the related cursive Zabūr script. Their interaction with African societies in the Horn is attested by numerous traces, including inscriptions and temples dating back to the Sabaean presence in Africa.

The Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' King Solomon of Israel and a supposed

The origin of the Sabaean Kingdom is uncertain and is a point of disagreement among scholars, with estimates placing it around 1200 BCE,Kenneth A. Kitchen ''The World of "Ancient Arabia" Series''. Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I. Chronological Framework and Historical Sources p.110 by the 10th century BCE at the latest, or a period of flourishing that only begins from the 8th century BCE onwards. Once the polity had been established, Sabaean kings referred to themselves by the title

The origin of the Sabaean Kingdom is uncertain and is a point of disagreement among scholars, with estimates placing it around 1200 BCE,Kenneth A. Kitchen ''The World of "Ancient Arabia" Series''. Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I. Chronological Framework and Historical Sources p.110 by the 10th century BCE at the latest, or a period of flourishing that only begins from the 8th century BCE onwards. Once the polity had been established, Sabaean kings referred to themselves by the title

After the disintegration of the first Himyarite Kingdom, the Sabaean Kingdom reappeared and began to vigorously campaign against the Himyarites, and it flourished for another century and a half. This resurgent kingdom was different from the earlier one in many important respects. The most significant change with the earlier Sabaean period is that local power dynamics had shifted from the oasis cities on the desert margin, like Marib, to the highland tribes. The Almaqah temple at Marib returned to being a religious center. Saba inaugurated a new coinage and the remarkable

After the disintegration of the first Himyarite Kingdom, the Sabaean Kingdom reappeared and began to vigorously campaign against the Himyarites, and it flourished for another century and a half. This resurgent kingdom was different from the earlier one in many important respects. The most significant change with the earlier Sabaean period is that local power dynamics had shifted from the oasis cities on the desert margin, like Marib, to the highland tribes. The Almaqah temple at Marib returned to being a religious center. Saba inaugurated a new coinage and the remarkable

In the Kingdom of Saba,

In the Kingdom of Saba,  The Marib Dam was one of the most well-known architectural complexes from Yemen, and was even mentioned in the Quran (34:16), and this construction made it possible to irrigate the 10,000 hectares of the Marib oasis. The dam is located 10 km west of the main settlement. The dam successfully delegates and distributes water from the biannual monsoon rains into two main channels, which move away from the wadi and into fields through a highly dispersive system. This allowed the region to convert alluvial loads into fertile soils and so cultivate various crops. It took until the 6th century BCE for the full closure to be accomplished. The system required constant maintenance, and two major dam failures are reported from 454/455 and 547 CE. However, as political authority weakened over the course of the 6th century CE, maintenance efforts could not be sustained. The dam was therefore breached and the oasis was temporarily abandoned by the early seventh century.

The Marib Dam was one of the most well-known architectural complexes from Yemen, and was even mentioned in the Quran (34:16), and this construction made it possible to irrigate the 10,000 hectares of the Marib oasis. The dam is located 10 km west of the main settlement. The dam successfully delegates and distributes water from the biannual monsoon rains into two main channels, which move away from the wadi and into fields through a highly dispersive system. This allowed the region to convert alluvial loads into fertile soils and so cultivate various crops. It took until the 6th century BCE for the full closure to be accomplished. The system required constant maintenance, and two major dam failures are reported from 454/455 and 547 CE. However, as political authority weakened over the course of the 6th century CE, maintenance efforts could not be sustained. The dam was therefore breached and the oasis was temporarily abandoned by the early seventh century.

The second Sabaean urban center was Sirwah. The two cities are connected by an ancient road. A wall had been built around Sirwah by the 10th century BCE. Much smaller than Marib, the city of Sirwah is 3.8 hectares in size, but it is archaeologically well-understood. The main buildings at the site are administrative and sacred buildings. Some buildings demonstrate that Sirwah acted as a transshipment point for trade goods. Legal documents show that Sirwah engaged in trade with

The second Sabaean urban center was Sirwah. The two cities are connected by an ancient road. A wall had been built around Sirwah by the 10th century BCE. Much smaller than Marib, the city of Sirwah is 3.8 hectares in size, but it is archaeologically well-understood. The main buildings at the site are administrative and sacred buildings. Some buildings demonstrate that Sirwah acted as a transshipment point for trade goods. Legal documents show that Sirwah engaged in trade with

Limitations in the available evidence prevent a full reconstruction of the full religious world in Ancient South Arabian kingdoms. While many of the known inscriptions speak about gods, most only hand down the name of the divinity without describing its nature, function, or cult. It is not known, for example, if these kingdoms had a god of war or a god of the underworld. Familial relationships between the gods are frequently mentioned, however.

Limitations in the available evidence prevent a full reconstruction of the full religious world in Ancient South Arabian kingdoms. While many of the known inscriptions speak about gods, most only hand down the name of the divinity without describing its nature, function, or cult. It is not known, for example, if these kingdoms had a god of war or a god of the underworld. Familial relationships between the gods are frequently mentioned, however.

Saba had five gods of its pantheon: Almaqah, Athtar, Haubas, Dhat-Himyam, and Dhat-Badan. The first three are male, and the last two are female. The high god of the pantheon, and the national god of Saba, was Almaqah, whose worship was centered at the Temple of Awwam. Military victory helped spread this cult, such as when a temple to Almaqah was built in

Saba had five gods of its pantheon: Almaqah, Athtar, Haubas, Dhat-Himyam, and Dhat-Badan. The first three are male, and the last two are female. The high god of the pantheon, and the national god of Saba, was Almaqah, whose worship was centered at the Temple of Awwam. Military victory helped spread this cult, such as when a temple to Almaqah was built in

The name of Saba' is mentioned in the Qur'an in Surah 5:69, Surah 27:15-44 and Surah 34:15-17. Surah 34 is named ''Sabaʾ''. Their mention in Surah 5 refers to the area in the context of

The name of Saba' is mentioned in the Qur'an in Surah 5:69, Surah 27:15-44 and Surah 34:15-17. Surah 34 is named ''Sabaʾ''. Their mention in Surah 5 refers to the area in the context of  The Ottoman scholar Mahmud al-Alusi compared the religious practices of South Arabia to Islam in his ''Bulugh al-'Arab fi Ahwal al-'Arab''.

According to the medieval religious scholar al-Shahrastani, Sabaeans accepted both the sensible and intelligible world. They did not follow religious laws but centered their worship on spiritual entities.

The Ottoman scholar Mahmud al-Alusi compared the religious practices of South Arabia to Islam in his ''Bulugh al-'Arab fi Ahwal al-'Arab''.

According to the medieval religious scholar al-Shahrastani, Sabaeans accepted both the sensible and intelligible world. They did not follow religious laws but centered their worship on spiritual entities.

. '' King Solomon of Israel and a supposed

Queen of Sheba

The Queen of Sheba, also known as Bilqis in Arabic and as Makeda in Geʽez, is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she brings a caravan of valuable gifts for Solomon, the fourth King of Israel and Judah. This a ...

. This narrative is co-opted by the Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

(not to be confused with the Sabians

The Sabians, sometimes also spelled Sabaeans or Sabeans, are a religious group mentioned three times in the Quran (as , in later sources ), where it is implied that they belonged to the 'People of the Book' (). Their original identity, which ...

). However, the historicity of the Hebrew Bible's account has been challenged by some historians due to a lack of sufficient evidence, although recent research has indicated that the kingdom was involved in the incense trade route

The incense trade route was an ancient network of major land and sea trading routes linking the Mediterranean world with eastern and southern sources of incense, spices and other luxury goods, stretching from Mediterranean ports across the Levan ...

as early in its history as the time of Solomon's reign. Traditions concerning the legacy of the Queen of Sheba feature extensively in Ethiopian Christianity, particularly Orthodox Tewahedo, and among Yemenis

Yemenis or Yemenites () are the Citizenship, citizen population of Yemen.

Genetic studies

Yemen, located in the southwestern corner of the Arabian Peninsula, serves as a crossroads between Africa and Eurasia. The genomes of present-day Yem ...

today. She is left unnamed in Jewish tradition, but is known as ''Makeda'' in Ethiopian tradition and as ''Bilqis'' in Arab and Islamic tradition. According to the Jewish historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

, Sheba was the home of Princess Tharbis, a Cushite who is said to have been the wife of Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

before he married Zipporah

Zipporah is mentioned in the Book of Exodus as the wife of Moses, and the daughter of Jethro (biblical figure), Jethro, the priest and prince of Midian.

She is the mother of Moses' two sons: Eliezer and Gershom.

In the Book of Chronicles, two of ...

. Some Quranic exegetes identified Sheba with the People of Tubba.

Sources

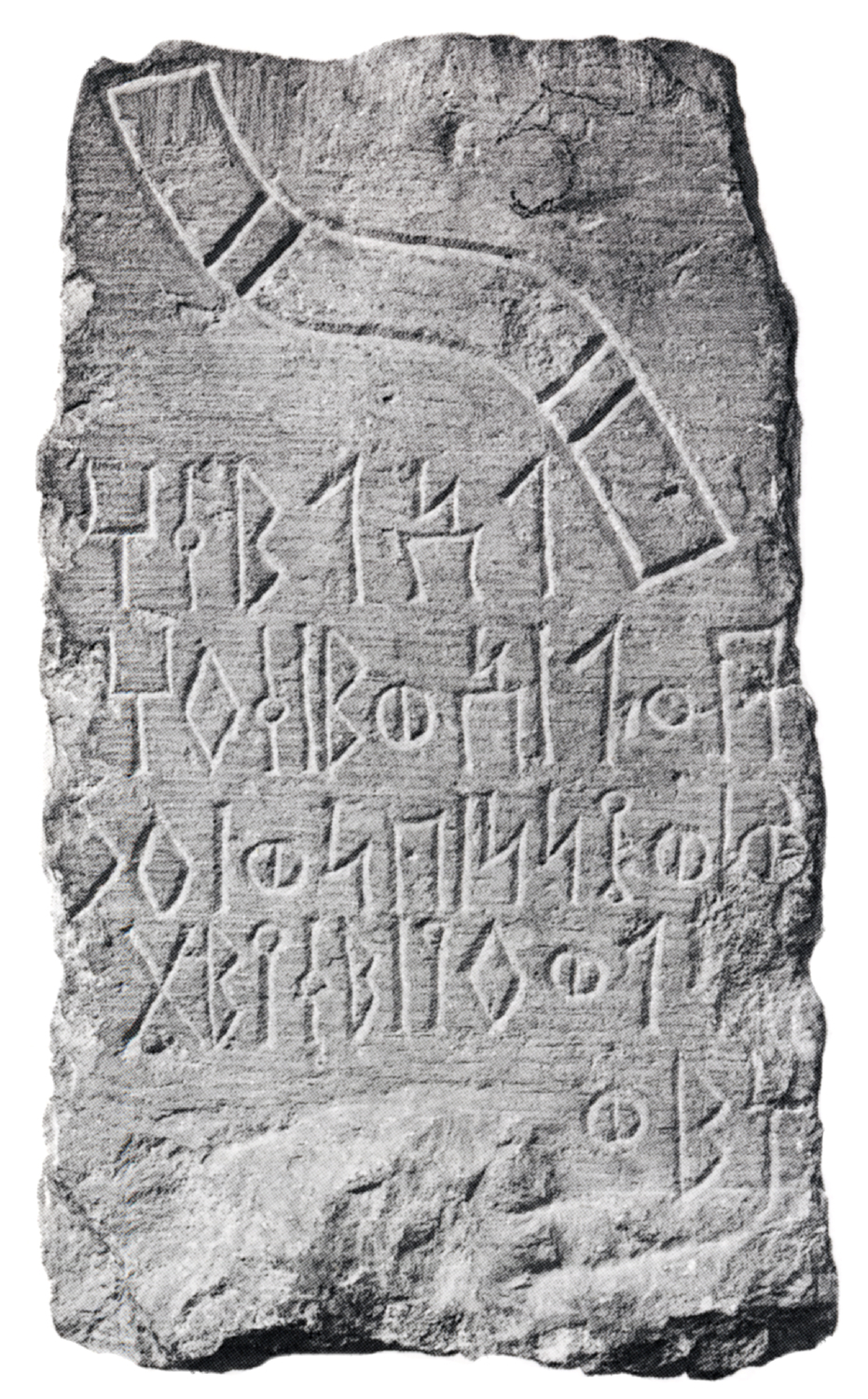

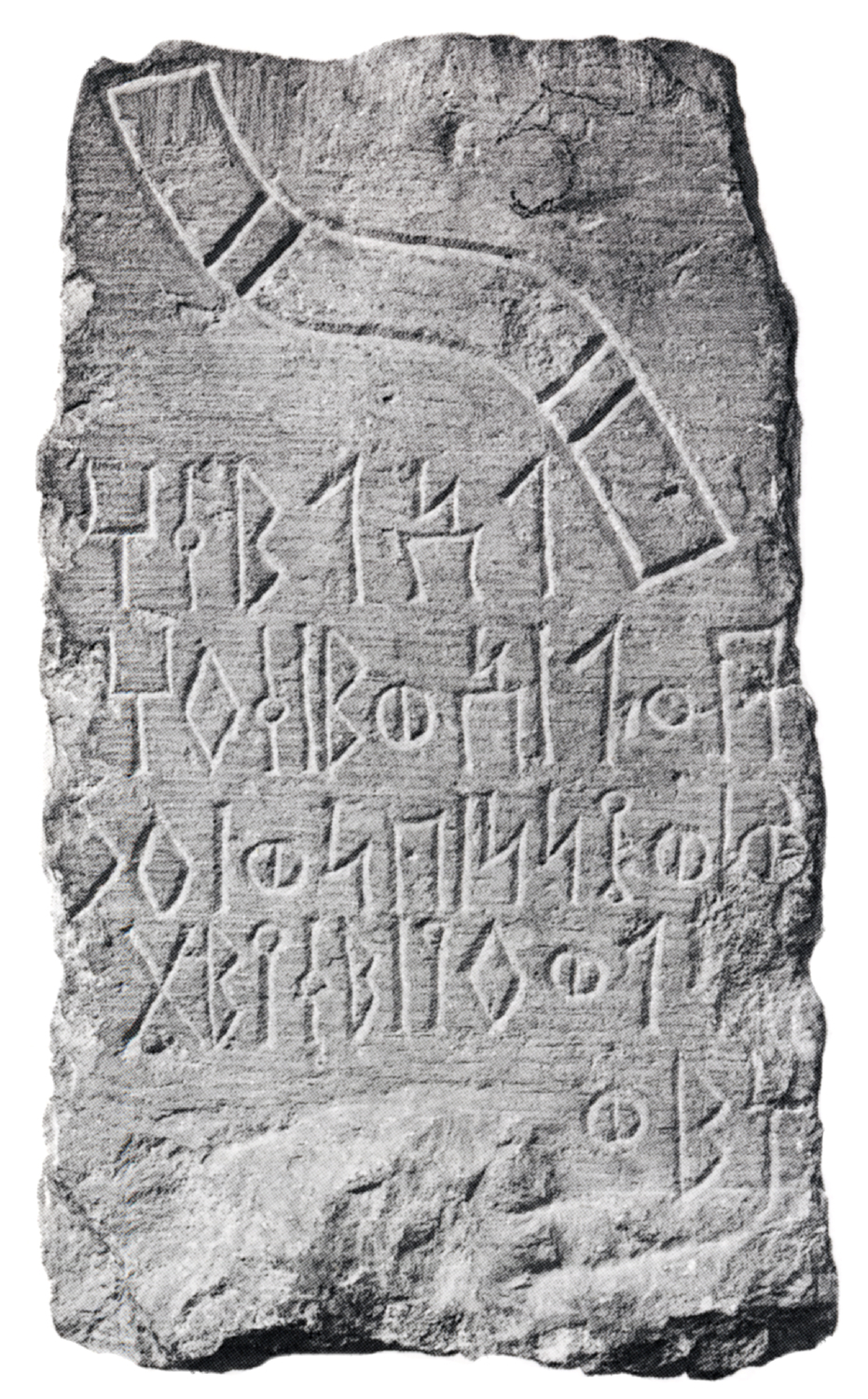

The Sabaic language was written down in the Sabaic script as early as the 11th or 10th centuries BCE. The Sabaic tradition has left behind a sizable epigraphic record. Of the 12,000 corresponding Ancient South Arabian inscriptions, 6,500 are in Sabaic. The region first sees a continuous record of epigraphic documentation in the 8th century BCE, which lasts until the 9th century CE, long after the fall of the Sabaean kingdom and covering a time range of about a millennium and a half and constituting the main source of information about the Sabaeans. South Arabian civilization may be the only civilization that can be reconstructed from epigraphic evidence. External information about the Sabaeans comes first fromAkkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform scripts are marked by and ...

texts starting in the 8th century BCE. Less important are brief reports from the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

about correspondence between Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

and the Queen of Sheba

The Queen of Sheba, also known as Bilqis in Arabic and as Makeda in Geʽez, is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she brings a caravan of valuable gifts for Solomon, the fourth King of Israel and Judah. This a ...

. While the story is of debatable historicity, knowledge of the Sabaeans as merchant peoples indicates that some level of trade between the regions was underway in this time. After the campaigns of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

, South Arabia became a hub of trade routes linking the broader geopolitical realm with India. As such, information about the region begins to appear among Greco-Roman observers and information becomes more concrete. The most important accounts about South Arabia are from Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; ; – ) was an Ancient Greek polymath: a Greek mathematics, mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theory, music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of A ...

, Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

, Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

, Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

, an anonymous first-century seafarming manual called the ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

The ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' (), also known by its Latin name as the , is a Greco-Roman world, Greco-Roman periplus written in Koine Greek that describes navigation and Roman commerce, trading opportunities from Roman Egyptian ports lik ...

'' concerning the politics and topography of South Arabian coasts, the ''Ecclesiastical History'' by Philostorgius, and Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea (; ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; ; – 565) was a prominent Late antiquity, late antique Byzantine Greeks, Greek scholar and historian from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman general Belisarius in Justinian I, Empe ...

.

History

Formative period

The formative phase of the Sabaeans, or the period prior to the emergence of urban cultures in South Arabia, can be placed the latter part of the 2nd millennium BCE, and was completed by the 10th century BCE, where a fully developed script appears in combination with the technological prowess to construct complex architectural complexes and cities. There is some debate as to the degree to which the movement out of the formative phase was channeled by endogenous processes, or the transfer or technologies from other centers, perhaps via trade and immigration. Originally, the Sabaeans were part of "communities" (called ''shaʿbs'') on the edge of the Sayhad desert. Very early, at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC, the political leaders of this tribal community managed to create a huge commonwealth of shaʿbs occupying most of South Arabian territory and took on the title "Mukarrib

Mukarrib (Old South Arabian: , romanized: ) is a title used by rulers in ancient South Arabia. It is attested as soon as continuous epigraphic evidence is available and it was used by the kingdoms of Saba, Hadhramaut, Qataban, and Awsan. The tit ...

of the Sabaeans".

Emergence

The origin of the Sabaean Kingdom is uncertain and is a point of disagreement among scholars, with estimates placing it around 1200 BCE,Kenneth A. Kitchen ''The World of "Ancient Arabia" Series''. Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I. Chronological Framework and Historical Sources p.110 by the 10th century BCE at the latest, or a period of flourishing that only begins from the 8th century BCE onwards. Once the polity had been established, Sabaean kings referred to themselves by the title

The origin of the Sabaean Kingdom is uncertain and is a point of disagreement among scholars, with estimates placing it around 1200 BCE,Kenneth A. Kitchen ''The World of "Ancient Arabia" Series''. Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I. Chronological Framework and Historical Sources p.110 by the 10th century BCE at the latest, or a period of flourishing that only begins from the 8th century BCE onwards. Once the polity had been established, Sabaean kings referred to themselves by the title Mukarrib

Mukarrib (Old South Arabian: , romanized: ) is a title used by rulers in ancient South Arabia. It is attested as soon as continuous epigraphic evidence is available and it was used by the kingdoms of Saba, Hadhramaut, Qataban, and Awsan. The tit ...

.

First Sabaean kingdom (8th – 1st centuries BCE)

Era of the ''mukarribs''

The first major phase of the Sabaean civilization lasted between the 8th and 1st centuries BCE. For centuries, Saba dominated the political landscape in South Arabia. The 8th century is when the first stone inscriptions appear, and when leaders are already being called by the titleMukarrib

Mukarrib (Old South Arabian: , romanized: ) is a title used by rulers in ancient South Arabia. It is attested as soon as continuous epigraphic evidence is available and it was used by the kingdoms of Saba, Hadhramaut, Qataban, and Awsan. The tit ...

("federator"). Due to this convention, this era can also be called the "Mukarrib period". The title ''mukarrib'' was more prestigious than that of ''mlk'' ("king") and was used to refer to someone that extended hegemony over other tribes and kingdoms.

Saba reached the height of its powers between the 8th and 6th centuries BCE. In particular, the great conquests of Karib'il Watar extended their territory to Najran

Najran ( '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is the capital of Najran Province. Today, the city of Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As of the 2022 census, the city population was 381,431, wi ...

in the north, the Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden (; ) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Channel, the Socotra Archipelago, Puntland in Somalia and Somaliland to the south. ...

in the southwest, and eastward from that point along the coast until the western foothills of the Hadhramaut plateau. Saba reigned supreme over South Arabia, and Karib'il established diplomatic contacts with the Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

. This territorial range by a South Arabian kingdom would not be seen again until Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

achieved it over 1,100 years later. Karib'il's success is reflected by the dynastic succession of four rulers from his lineage, including sons, grandson, and great-grandons, a rare occurrence in the face of the rarity of dynastic succession in ancient South Arabian culture. The next time this would be seen was six centuries later in Qataban.

Era of the kings

After the 6th century BCE, Saba was unable to maintain its supremacy over South Arabia in the face of the expanding adjacent powers ofQataban

Qataban () was an ancient Yemenite kingdom in South Arabia that existed from the early 1st millennium BCE to the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.

It was one of the six ancient South Arabian kingdoms of ancient Yemen, along with Sabaʾ, Maʿīn ...

and Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah and Mahrah, Dhofar in southwestern Oman, and Sharurah in the Najran Province of Saudi A ...

militarily, and Ma'in

Ma'in (; ) was an ancient South Arabian kingdom in modern-day Yemen. It was located along the strip of desert called Ramlat al-Sab'atayn, Ṣayhad by medieval Arab geographers, which is now known as Ramlat al-Sab'atayn. Wadd was the national ...

economically, leading it contract back to its core territory around Marib

Marib (; Ancient South Arabian script, Old South Arabian: 𐩣𐩧𐩨/𐩣𐩧𐩺𐩨 ''Mryb/Mrb'') is the capital city of Marib Governorate, Yemen. It was the capital of the ancient kingdom of ''Saba’, Sabaʾ'' (), which some scholars beli ...

and Sirwah. Sabaean leaders reverted to use of the title ''malik'' ("king") instead of ''mukarrib''. This decline began soon after the end of the reign of Karib'il Watar. While Karib'il established hegemony over the Jawf, his immediate successors only consolidated their power over some of its former city-states (including Nashq and Manhayat) whereas others (like Yathill

Barāqish or Barāgish or Aythel () is a town in north-western Yemen, 120 miles to the east of Sanaa in al Jawf Governorate on a high hill. It is located in Wādī Farda(h), a popular caravan route because of the presence of water. It was known ...

and the towns of Wadhi Raghwan) were absorbed into Ma'in. Qataban expanded into the Southern Highlands, formerly under Sabaean rule.

Economically, the first Sabaean period was dominated by a caravan economy that had market ties with the rest of the Near East. Its first major trading partners were at Khindanu and the Middle Euphrates. Later, this moved to Gaza during the Persian period, and finally, to Petra

Petra (; "Rock"), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu (Nabataean Aramaic, Nabataean: or , *''Raqēmō''), is an ancient city and archaeological site in southern Jordan. Famous for its rock-cut architecture and water conduit systems, P ...

in Hellenistic times. The South Arabian deserts gave rise to important aromatics which were exported in trade, especially frankincense

Frankincense, also known as olibanum (), is an Aroma compound, aromatic resin used in incense and perfumes, obtained from trees of the genus ''Boswellia'' in the family (biology), family Burseraceae. The word is from Old French ('high-quality in ...

and myrrh

Myrrh (; from an unidentified ancient Semitic language, see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a few small, thorny tree species of the '' Commiphora'' genus, belonging to the Burseraceae family. Myrrh resin has been used ...

. It also acted as an intermediary for overland trade with neighbours in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

and further off from India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

.

By the end of the 1st millennium BCE, several factors came together and brought about the decline of the Sabaean state and civilization. The biggest challenge came from the expansion of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

. The Republic conquered Syria in 63 BCE and Egypt in 30 BCE, diverting Saba's overland trade network. The Romans then attempted to conquer Saba around 26/25 BCE with an army sent out under the command of the governor Aelius Gallus, setting Marib to siege. Due to heat exhaustion, the siege had to be quickly given up. However, after conquering Egypt, the overland trade network was redirected to maritime routes, with an intermediary port chosen with Bir Ali (then called Qani). This port was part of the Kingdom of Hadhramaut

Ḥaḍramawt ( Ḥaḑramitic: , romanized: ; Sabaic, Minaic, Qatabānic: , romanized: ) was an ancient South Semitic-speaking kingdom of South Arabia ( ancient Yemen) which existed from the early 1st millennium BCE till the late 3rd centur ...

, far from Sabaean territory. Greatly economically weakened, the Kingdom of Saba was soon annexed by the Himyarite Kingdom

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qataban, Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According ...

, bringing this period to a close.

Second Sabaean kingdom (1st – 3rd centuries CE)

After the disintegration of the first Himyarite Kingdom, the Sabaean Kingdom reappeared and began to vigorously campaign against the Himyarites, and it flourished for another century and a half. This resurgent kingdom was different from the earlier one in many important respects. The most significant change with the earlier Sabaean period is that local power dynamics had shifted from the oasis cities on the desert margin, like Marib, to the highland tribes. The Almaqah temple at Marib returned to being a religious center. Saba inaugurated a new coinage and the remarkable

After the disintegration of the first Himyarite Kingdom, the Sabaean Kingdom reappeared and began to vigorously campaign against the Himyarites, and it flourished for another century and a half. This resurgent kingdom was different from the earlier one in many important respects. The most significant change with the earlier Sabaean period is that local power dynamics had shifted from the oasis cities on the desert margin, like Marib, to the highland tribes. The Almaqah temple at Marib returned to being a religious center. Saba inaugurated a new coinage and the remarkable Ghumdan Palace

Ghumdan Palace, also Qasir Ghumdan or Ghamdan Palace, is an ancient fortified palace in Sana'a, Yemen, going back to the ancient Kingdom of Saba. All that remains of the ancient site (Ar. ''khadd'') of Ghumdan is a field of tangled ruins opposite ...

was built at Sanaa

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

which, in this period, had its status elevated to that of a secondary capital next to Marib.

Despite liberating itself from Himyar by around 100 CE, leaders of Himyar continued calling themselves the "king of Saba", as they had been doing during the period in which they ruled the region, to assert their legitimacy over the territory. The Kingdom fell after a long but sporadic civil war between several Yemenite dynasties claiming kingship,Javad Ali, ''The Articulate in the History of Arabs before Islam,'' Volume 2, p. 420 and the late Himyarite Kingdom

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qataban, Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According ...

rose as victorious. Sabaean kingdom was finally permanently conquered by the Ḥimyarites around 275 CE. Saba lost its royal status and reverted to a normal tribe, limited to the citizens of Marib, who are named in the last time in South Arabian sources in CIH 541 in requesting assistance from the king in repairing a rupture in the Marib Dam.

Conquests

Conquests of Karib'il Watar

The major conquests in Saba were driven by the exploits of Karib'il Watar. Karib'il conquered all surrounding neighbours, including theAwsan

The Kingdom of Awsan, commonly known simply as Awsan (; ), was a kingdom in Ancient South Arabia, centered around a wadi called the Wadi Markha. The wadi remains archaeologically unexplored. The name of the capital of Awsan is unknown, but it is ...

, Qataban

Qataban () was an ancient Yemenite kingdom in South Arabia that existed from the early 1st millennium BCE to the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.

It was one of the six ancient South Arabian kingdoms of ancient Yemen, along with Sabaʾ, Maʿīn ...

, and Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah and Mahrah, Dhofar in southwestern Oman, and Sharurah in the Najran Province of Saudi A ...

. Karib'il's exploits largely unified Yemen.The conquests of Karib'il are documented in two lengthy inscriptions (RES 3945–3946) discovered at the Temple of Almaqah at Sirwah. These inscriptions describe a series of eight campaigns to show how Karib'il ultimately brought South Arabia under the control of Saba. The first campaign took place in the highlands west of Marib, where Karib'il declares that he had captured 8,000 and killed 3,000 enemies. The second campaign concerned the Kingdom of Awsan, which flourished in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. Up until the reign of Karib'il, it was a significant regional competitor with the Kingdom of Saba. However, Karib'il's campaign brought about the obliteration of the Kingdom of Awsan. The tribal elite leading Awsan were slaughtered, and the palace of Murattaʿ was destroyed, as well as their temples and inscriptions. The wadi was depopulated, which is reflected in the abandonment of the wadi. Sabaean inscriptions claim that 16,000 were killed and 40,000 prisoners were taken. This may not have been a significant exaggeration, as the Awsan kingdom disappeared as a political entity from the historical record for five or six centuries. The third and fourth campaigns involve attacks against tribes living in low-lying hills that geographically face the Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden (; ) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Channel, the Socotra Archipelago, Puntland in Somalia and Somaliland to the south. ...

. The fifth and sixth campaigns were against Nashshan

Nashshan ( Minaean: romanized: , ; modern day Kharbat Al-Sawda', ) is the name of an ancient South Arabian city in the northern al-Jawf region of present day Yemen, originally independent but later subsumed into the territory of the ancient Ki ...

. Nashshan was, like Awsan, one of Saba's most powerful competitors. However, against Karib'il, combined with the destruction of several towns and buildings and the imposition of a tribute on its people. Any dissidents were killed and the cult of Almaqah was imposed onto Nashshan, with Nashshan's leaders being required to build a temple for him. The final two campaigns were against the Tihamah

Tihamah or Tihama ( ') is the Red Sea coastal plain of the Arabian Peninsula from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Bab el Mandeb.

Etymology

Tihāmat is the Proto-Semitic language's term for 'sea'. Tiamat (or Tehom, in masculine form) was the ancient M ...

coastal region and the Najran

Najran ( '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is the capital of Najran Province. Today, the city of Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As of the 2022 census, the city population was 381,431, wi ...

region.

African conquests

Around 800 BCE, the Sabaeans conquered parts ofEritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

and the Tigray Region

The Tigray Region (or simply Tigray; officially the Tigray National Regional State) is the northernmost Regions of Ethiopia, regional state in Ethiopia. The Tigray Region is the homeland of the Tigrayan, Irob people, Irob and Kunama people. I ...

of Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

, triggering a Sabaean colonization event that created the Eri-Ethio-Sabaean Kingdom of Di'amat. Sabaean populations migrated to maintain the new polity, and link it with the mother country, including through managing trade between the two (ivory might have especially been a driver of the expansion). The capital of the new kingdom was Yeha, where a great temple was built for Almaqah, the national god of Saba. Four other Almaqah temples are also known from Di'amat (including the Temple of Meqaber Gaʿewa), and other inscriptions mention the complete remainder of the known Sabaean deities. The great Yeha temple was modelled by Sabaean masons off of the Almaqah Temple at Sirwah (a major urban center of Saba). Besides religion, Sabaean culture also diffused into Di'amat through the use of objects, architectural techniques, artistic styles, institutions, paleographical styles for writings inscriptions, and the use of abstract symbols. Leaders in Di'amat used the classical South Arabian title, the ''mukarrib

Mukarrib (Old South Arabian: , romanized: ) is a title used by rulers in ancient South Arabia. It is attested as soon as continuous epigraphic evidence is available and it was used by the kingdoms of Saba, Hadhramaut, Qataban, and Awsan. The tit ...

'', and one particular title that is seen is the "Mukarrib of Diʿamat and Saba" (''mkrb Dʿmt s-S1bʾ''). The exact timing of the collapse of Di'amat is not known: it happened around the mid-1st millennium BCE and involved a destruction of Yeha along with a number of adjacent sites. This also happened when Saba was beginning to lose its grip on power over South Arabia. Nevertheless, Sabaeans continued migrating to Ethiopia after this collapse and Ethiopia only established a position of power for itself when the Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum, or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom in East Africa and South Arabia from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, based in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, and spanning present-day Djibouti and Sudan. Emerging ...

arose in the 1st century CE.

Military warfare continued between Saba, Ethiopia, and Himyar during the second Sabaean period, with a dynamic and shifting array of alliances. Recently discovered evidence shows that these encounters took place, not only on the peninsula, but also on Ethiopian territory during expeditions launched by the Sabaeans.

Urban centers

Marib

In the Kingdom of Saba,

In the Kingdom of Saba, Marib

Marib (; Ancient South Arabian script, Old South Arabian: 𐩣𐩧𐩨/𐩣𐩧𐩺𐩨 ''Mryb/Mrb'') is the capital city of Marib Governorate, Yemen. It was the capital of the ancient kingdom of ''Saba’, Sabaʾ'' (), which some scholars beli ...

was an oasis and one of the main urban centers of the kingdom. It was by far the largest ancient city from ancient South Arabia, if not its only real city. Marib was located at the precise point that the wadi (of Wadi Dhana) emerges from the Yemeni highlands. It was located along what was called the Sayhad desert by medieval Arab geographers, but is now known as Ramlat al-Sab'atayn

Yemeni Desert.

The Ramlat al-Sab'atayn () is a desert region that corresponds with the northern deserts of modern Yemen ( Al-Jawf, Marib, Shabwah governorates) and southwestern Saudi Arabia (Najran province).

It comprises mainly transverse and s ...

. The city lies 135 km east of Sanaa

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

, which is the capital of Yemen today, found in the Wadi Dana delta, in the northwestern central Yemeni highlands. The oasis is about 10,000 hectares and the course of the wadi divides it into two: a northern and a southern half, which was already spoken of in records from the 8th century BCE, and this prominent feature may have been remembered as late as in the time of the Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

(34:15). A wall was built around Marib, and 4 km of that wall is still standing today. The wall, in some places, can be as much as 14 m thick. The wall encloses a 100-hectare area shaped like a trapezoid, and the settlement appears to have been created in the late second millennium BCE. Archaeological inquiries have uncovered a settlement plan that allocated different areas for different tasks. There is one residential division to the city. Another division containing sacred buildings but no residential development was probably a storage area for trade caravans and the shipment of goods. Immediately to the west was the great city temple Harun, dedicated to the national Sabaean god, Almaqah.

A processional road, known from inscriptions but not yet discovered, led from the Harun temple to the Temple of Awwam, 3.5 km to the southeast of Marib, which is both the main temple for the god Almaqah in the Kingdom of Saba and the largest temple complex known from South Arabia. Hundreds of inscriptions are known from the Awwam Temple, and these documents form the basis from which the political history of South Arabia thus far reconstructable from in the first few centuries of the Christian era. The enclosure was built in the 7th century BCE according to a monumental inscription from the time of Yada'il Darih. South of the temple wall is a 1.5-hectare necropolis, in which it is estimated that about 20,000 people have been buried over a time period covering about a millennium.

Shortly west of the Awwam Temple is another major temple in the southern oasis dedicated to Almaqah, which has been fully excavated and is the best studied temple to date from South Arabia: the Barran Temple. It is evident that predecessors to the Barran Temple went back to the 10th century BCE. The construction history is properly documented by inscriptions in the area. The temple was destroyed shortly before the beginning of the Christian eraddea. The exact cause is unknown, but it may have been linked to an (ultimately unsuccessful) siege of South Arabia by the Romans, under the leadership of the governor Aelius Gallus in 25/24 BCE. Inscriptions attest other temples dedicated to other gods but these have not yet been discovered archaeologically.

The Marib Dam was one of the most well-known architectural complexes from Yemen, and was even mentioned in the Quran (34:16), and this construction made it possible to irrigate the 10,000 hectares of the Marib oasis. The dam is located 10 km west of the main settlement. The dam successfully delegates and distributes water from the biannual monsoon rains into two main channels, which move away from the wadi and into fields through a highly dispersive system. This allowed the region to convert alluvial loads into fertile soils and so cultivate various crops. It took until the 6th century BCE for the full closure to be accomplished. The system required constant maintenance, and two major dam failures are reported from 454/455 and 547 CE. However, as political authority weakened over the course of the 6th century CE, maintenance efforts could not be sustained. The dam was therefore breached and the oasis was temporarily abandoned by the early seventh century.

The Marib Dam was one of the most well-known architectural complexes from Yemen, and was even mentioned in the Quran (34:16), and this construction made it possible to irrigate the 10,000 hectares of the Marib oasis. The dam is located 10 km west of the main settlement. The dam successfully delegates and distributes water from the biannual monsoon rains into two main channels, which move away from the wadi and into fields through a highly dispersive system. This allowed the region to convert alluvial loads into fertile soils and so cultivate various crops. It took until the 6th century BCE for the full closure to be accomplished. The system required constant maintenance, and two major dam failures are reported from 454/455 and 547 CE. However, as political authority weakened over the course of the 6th century CE, maintenance efforts could not be sustained. The dam was therefore breached and the oasis was temporarily abandoned by the early seventh century.

Sirwah

Qataban

Qataban () was an ancient Yemenite kingdom in South Arabia that existed from the early 1st millennium BCE to the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.

It was one of the six ancient South Arabian kingdoms of ancient Yemen, along with Sabaʾ, Maʿīn ...

to the southeast and the highlands around Sanaa to the west. Despite the urban area being limited, a significant portion of the space was allocated to sacred buildings. This has led some people to think that Sirwah acted as a religious center. The Great Temple of Almaqah is the most notable one, besides which, four other sacred buildings are known. One of these buildings was probably devoted to the female deity Atarsamain. Yada'il Darih, already a temple builder at the Awwam Temple in Marib, also fundamentally remodelled the Alwaqah Temple in the mid-7th century BCE. Inside the temple, in the area that is most cultically important, stands two parallel monumental inscriptions recording the lifetime achievements of two rulers: Yatha' Amar Watar

Yatha' Amr Watar bin Yakarib Malik (d. 710 BC) was one of the ancient Mukarrib of Saba, who ruled in the last two or three decades of the eighth century BC.

He is the author of the oldest and most important ancient historical documents related ...

and Karib'il Watar, who reigned in the late 8th and early 7th centuries BCE. The description in these records begins with comments on sacrifices made to the Sabaean deities, and then mostly delve into military campaigns in meticulous detail. At the end, the inscriptions record purchases of cities, landscapes, and fields.

Society

The gods

Limitations in the available evidence prevent a full reconstruction of the full religious world in Ancient South Arabian kingdoms. While many of the known inscriptions speak about gods, most only hand down the name of the divinity without describing its nature, function, or cult. It is not known, for example, if these kingdoms had a god of war or a god of the underworld. Familial relationships between the gods are frequently mentioned, however.

Limitations in the available evidence prevent a full reconstruction of the full religious world in Ancient South Arabian kingdoms. While many of the known inscriptions speak about gods, most only hand down the name of the divinity without describing its nature, function, or cult. It is not known, for example, if these kingdoms had a god of war or a god of the underworld. Familial relationships between the gods are frequently mentioned, however.

Saba had five gods of its pantheon: Almaqah, Athtar, Haubas, Dhat-Himyam, and Dhat-Badan. The first three are male, and the last two are female. The high god of the pantheon, and the national god of Saba, was Almaqah, whose worship was centered at the Temple of Awwam. Military victory helped spread this cult, such as when a temple to Almaqah was built in

Saba had five gods of its pantheon: Almaqah, Athtar, Haubas, Dhat-Himyam, and Dhat-Badan. The first three are male, and the last two are female. The high god of the pantheon, and the national god of Saba, was Almaqah, whose worship was centered at the Temple of Awwam. Military victory helped spread this cult, such as when a temple to Almaqah was built in Nashshan

Nashshan ( Minaean: romanized: , ; modern day Kharbat Al-Sawda', ) is the name of an ancient South Arabian city in the northern al-Jawf region of present day Yemen, originally independent but later subsumed into the territory of the ancient Ki ...

after being conquered by Saba. The mention of Almaqah in the Jawf also indicates the political role played by Saba in that valley. The nature of the god is not entirely clear, but Almaqah has been hypothesized to be a moon god

A lunar deity or moon deity is a deity who represents the Moon, or an aspect of it. These deities can have a variety of functions and traditions depending upon the culture, but they are often related. Lunar deities and Moon worship can be foun ...

by some researchers.

Athtar was not limited to Saba, but was instead the common god of the South Arabian pantheon during its polytheistic era. Athtar was also once the great god of the Sabaean pantheon, before being supplanted by Almaqah. Generally however, South Arabian deities are region-specific and lack parallel elsewhere in the Near East.

Anthropomorphic representations of the gods are lacking entirely from the Old Sabaean period, and only begin to appear with the onset of Hellenistic and Roman influences at the turn of the Christian era.

The king

Ancient South Arabian kings built great public works, had special ties with the gods legitimated through rites only they could perform, and led their armies during battle. They are represented as brave warriors, pious worshippers, and active builders. The fathers of the king is rarely attested independently. The function of the king was distinct from the role of the ''sheikh''. The ''Geographica

The ''Geographica'' (, ''Geōgraphiká''; or , "Strabo's 17 Books on Geographical Topics") or ''Geography'', is an encyclopedia of geographical knowledge, consisting of 17 'books', written in Greek in the late 1st century BC, or early 1st cen ...

'' by Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

claims that in the region, the succession of kings was not familial, a claim that is partly confirmed by inscriptions. South Arabian kings did not appeal to their genealogy or the accomplishments of their fathers to legitimate their own rule. Only late in Sabaean history, from the second half of the 2nd century CE, did a real dynastic succession from father to son appear, and it only lasted for two generations.

The Sabaean king was called the ''mukarrib

Mukarrib (Old South Arabian: , romanized: ) is a title used by rulers in ancient South Arabia. It is attested as soon as continuous epigraphic evidence is available and it was used by the kingdoms of Saba, Hadhramaut, Qataban, and Awsan. The tit ...

'' ("federator") more often than the ''malik'' ("king") between the 8th and 6th centuries BCE, to indicate their hegemony over their neighbours. When Saba declined after the 6th centuries BCE and Sabaean territory contracted to what it was prior to the conquests of Karib'il Watar, the title ''mukarrib'' is replaced by that of ''malik''.

In the early centuries of Saba, the title of the king was a combination of a name and an epithet. All titles were chosen from a combination of six possible names (Dhamar'ali, Karib'il, Sumhu'alay, Yada"il, Yakrubmalik and Yitha'amar) and four possible epithets (Bayan, Dharih, Watar and Yanu). The repetitiveness of names has caused difficulties for historians trying to determine the relative succession of kings (even when they are attested) and raises questions about what the personal names were of each king. A similar practice took place in the neighbouring Kingdom of Hadhramaut

Ḥaḍramawt ( Ḥaḑramitic: , romanized: ; Sabaic, Minaic, Qatabānic: , romanized: ) was an ancient South Semitic-speaking kingdom of South Arabia ( ancient Yemen) which existed from the early 1st millennium BCE till the late 3rd centur ...

. In the centuries leading up to the Christian era, this changed, kings began identifying with their real name, and reconstructions of Sabaean chronology become simpler.

Accession to the Sabaean throne required the consent of "the Sabaeans, the ''qayls'' and the army" in one inscription. The legislative body extended beyond the king, including other functionaries. The Sabaean monarchs did not implement taxes but derived their wealth from royal lands, war boody, and rent from clients. Military service could be compelled and financial requests could be made for the purpose of funding construction work. Any tithes on temple lands went to the temples themselves, not the monarch.

The king of Saba was not deified. The only known case of deification from ancient South Arabian cultures is from the Kingdom of Awsan during its resurgent phase.

The tribe

In the South Arabian tribal system, a fictitious shared ancestor was created and members of the tribe are referred to as the sons of the national god (in the case of Saba, they are "sons of Almaqah"). Allied states and tribes are called "brothers". Tribes were divided into lineages and sub-lineages, reflected by the names of members. The individual proper name appears along with the patronymic, the lineage name, and the name of the tribe, with the exception of funerary inscriptions, where the individual name is attested alone. In areas closer to the desert, the family name was more privileged and commonly mentioned, with the tribal name becoming less mentioned. Personal identity only went back to the name of the father, unlike in North Arabia in the same time period or the later Islamic period where a long sequence of ancestors is used to identify a figure. Identity was also in reference to the kingdom that one belonged to (Sabaeans, Qatabanians), not to a broader geographical construct (like "South Arabian").Culture

Language

Sabaic

Sabaic, sometimes referred to as Sabaean, was a Old South Arabian, Sayhadic language that was spoken between c. 1000 BC and the 6th century AD by the Sabaeans. It was used as a written language by some other peoples of the ancient civilization of ...

was the spoken language of the Kingdom of Saba. Geographically, Sabaic was spoken in Saba, just as Qatabanic was spoken in Qataban and Hadraumitic was spoken in Hadhramaut. The only exception to this is Minaic

The Minaean language (also Minaic, Madhabaic or Madhābic) was an Old South Arabian or Ṣayhadic language spoken in Yemen in the times of the Old South Arabian civilisation. The main area of its use may be located in the al-Jawf region of Nort ...

, which is attested well-beyond the geographical territory of its corresponding kingdom, Ma'in. These four languages share and are distinguished by a number of linguistic features. The documentation for Sabaic is the best of any language of Ancient South Arabian, attested in all phases of the history of Saba.

Writing schools

The South Arabian kingdoms had writing schools with a common cultural background, although each school also had distinct practices.Legacy

Bible

Saba appears in theHebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Queen of Sheba The Queen of Sheba, also known as Bilqis in Arabic and as Makeda in Geʽez, is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she brings a caravan of valuable gifts for Solomon, the fourth King of Israel and Judah. This a ...

, engaging in trade with . '' Queen of Sheba The Queen of Sheba, also known as Bilqis in Arabic and as Makeda in Geʽez, is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she brings a caravan of valuable gifts for Solomon, the fourth King of Israel and Judah. This a ...

Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

in goods of aromatics and gold. Historians have subjected this story to questions concerning its historicity. The Hebrew Bible links the Sabaean caravan trading network with other cities including Dedan, Tayma

Tayma (; Taymanitic: 𐪉𐪃𐪒, , vocalized as: ) or Tema is a large oasis with a long history of settlement, located in northwestern Saudi Arabia at the point where the trade route between Medina and Dumah (Sakakah) begins to cross the Na ...

, and Ra'mah.

Islamic tradition

The story of the visit of theQueen of Sheba

The Queen of Sheba, also known as Bilqis in Arabic and as Makeda in Geʽez, is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she brings a caravan of valuable gifts for Solomon, the fourth King of Israel and Judah. This a ...

to Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

story is discussed in Quran 27:15–44.

The name of Saba' is mentioned in the Qur'an in Surah 5:69, Surah 27:15-44 and Surah 34:15-17. Surah 34 is named ''Sabaʾ''. Their mention in Surah 5 refers to the area in the context of

The name of Saba' is mentioned in the Qur'an in Surah 5:69, Surah 27:15-44 and Surah 34:15-17. Surah 34 is named ''Sabaʾ''. Their mention in Surah 5 refers to the area in the context of Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

and the Queen of Sheba

The Queen of Sheba, also known as Bilqis in Arabic and as Makeda in Geʽez, is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she brings a caravan of valuable gifts for Solomon, the fourth King of Israel and Judah. This a ...

, whereas their mention in Surah 34 refers to the Flood of the Dam, in which the dam was ruined by flooding. There is also an epithet, ''Qawm Tubbaʿ'' or "People of Tubbaʿ" ( Surah 44:37, Surah 50:12-14) that some exegetes have identified as a reference to the kings of Saba'.

Muslim commentators such as al-Tabari

Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Jarīr ibn Yazīd al-Ṭabarī (; 839–923 CE / 224–310 AH), commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Sunni Muslim scholar, polymath, historian, exegete, jurist, and theologian from Amol, Tabaristan, present- ...

, al-Zamakhshari, al-Baydawi

Qadi Baydawi (also known as Naṣir ad-Din al-Bayḍawi, also spelled Baidawi, Bayzawi and Beyzavi; d. June 1319, Tabriz) was a jurist, theologian, and Quran commentator. He lived during the post-Seljuk Empire, Seljuk and early Mongol Empire, Mon ...

supplement the story at various points. The Queen's name is given as ''Bilqis'', probably derived from Greek παλλακίς or the Hebraised ''pilegesh'', "concubine". According to some he then married the Queen, while other traditions assert that he gave her in marriage to a tubba of Hamdan. According to the Islamic tradition as represented by al-Hamdani, the queen of Sheba was the daughter of Ilsharah Yahdib, the Himyarite king of Najran

Najran ( '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is the capital of Najran Province. Today, the city of Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As of the 2022 census, the city population was 381,431, wi ...

.

Although the Quran and its commentators have preserved the earliest literary reflection of the complete Bilqis legend, there is little doubt among scholars that the narrative is derived from a Jewish Midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

.

Bible stories of the Queen of Sheba and the ships of Ophir served as a basis for legends about the Israelites traveling in the Queen of Sheba's entourage when she returned to her country to bring up her child by Solomon. There is a Muslim tradition that the first Jews arrived in Yemen at the time of King Solomon, following the politico-economic alliance between him and the Queen of Sheba.. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

The Ottoman scholar Mahmud al-Alusi compared the religious practices of South Arabia to Islam in his ''Bulugh al-'Arab fi Ahwal al-'Arab''.

According to the medieval religious scholar al-Shahrastani, Sabaeans accepted both the sensible and intelligible world. They did not follow religious laws but centered their worship on spiritual entities.

The Ottoman scholar Mahmud al-Alusi compared the religious practices of South Arabia to Islam in his ''Bulugh al-'Arab fi Ahwal al-'Arab''.

According to the medieval religious scholar al-Shahrastani, Sabaeans accepted both the sensible and intelligible world. They did not follow religious laws but centered their worship on spiritual entities.

Ethiopian and Yemenite tradition

In the medieval Ethiopian cultural work called the Kebra Nagast, Sheba was located in Ethiopia. Some scholars therefore point to a region in the northernTigray

The Tigray Region (or simply Tigray; officially the Tigray National Regional State) is the northernmost Regions of Ethiopia, regional state in Ethiopia. The Tigray Region is the homeland of the Tigrayan, Irob people, Irob and Kunama people. I ...

and Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

which was once called Saba (later called Meroe), as a possible link with the biblical Sheba. Donald N. Levine links Sheba with Shewa

Shewa (; ; Somali: Shawa; , ), formerly romanized as Shua, Shoa, Showa, Shuwa, is a historical region of Ethiopia which was formerly an autonomous kingdom within the Ethiopian Empire. The modern Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa is located at it ...

(the province where modern Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; ,) is the capital city of Ethiopia, as well as the regional state of Oromia. With an estimated population of 2,739,551 inhabitants as of the 2007 census, it is the largest city in the country and the List of cities in Africa b ...

is located) in Ethiopia. Donald N. Levine, ''Wax and Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopia Culture'' (Chicago: University Press, 1972).

Traditional Yemenite genealogies also mention Saba, son of Qahtan

The Qahtanites (; ), also known as Banu Qahtan () or by their nickname ''al-Arab al-Ariba'' (), are the Arabs who originate from modern-day Yemen. The term "Qahtan" is mentioned in multiple Ancient South Arabian script, Ancient South Arabian ins ...

; Early Islamic historians identified Qahtan with the Yoqtan (Joktan

Joktan (also written as Yoktan; ; ) was the second of the two sons of Eber (Book of Genesis 10:25; 1 Chronicles 1:19) mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. He descends from Shem, son of Noah.

In the Book of Genesis 10:25 it reads: "And unto Eber were bo ...

) son of Eber

Eber (; ; ) is an ancestor of the Ishmaelites and the Israelites according to the Generations of Noah in the Book of Genesis () and the Books of Chronicles ().

Lineage

Eber (Hebrew: Ever) was a great-grandson of Noah's son Shem and the father ...

( Hūd) in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' James A. Montgomery finds it difficult to believe that Qahtan was the biblical

"Queen of Sheba mystifies at the Bowers"

– UC Irvine news article on Queen of Sheba exhibit at the Bowers Museum

from the ''Saudi Aramco World'' online – March/April 1978

Queen of Sheba Temple restored (2000, BBC)

*William Leo Hansberry, E. Harper Johnson

"Africa's Golden Past: Queen of Sheba's true identity confounds historical research"

''

S. Arabian "Inscription of Abraha" in the Sabaean language

, at Smithsonian/NMNH website

Saba'

(

. '' James A. Montgomery finds it difficult to believe that Qahtan was the biblical

Joktan

Joktan (also written as Yoktan; ; ) was the second of the two sons of Eber (Book of Genesis 10:25; 1 Chronicles 1:19) mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. He descends from Shem, son of Noah.

In the Book of Genesis 10:25 it reads: "And unto Eber were bo ...

based on etymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

.

See also

* Ancient South Arabian art * Landmarks of the Ancient Kingdom of Saba, Marib *List of rulers of Saba and Himyar

This is a list of rulers of Saba' and Himyar, ancient Arab kingdoms which are now part of present-day Yemen. The kingdom of Saba' became part of the Himyarite Kingdom in the late 3rd century CE.

The title Mukarrib (Old South Arabian: , romanize ...

* Azd

The Azd (Arabic: أَزْد), or Al-Azd (Arabic: ٱلْأَزْد), is an ancient Tribes of Arabia, Arabian tribe. The lands of Azd occupied an area west of Bisha and Al Bahah in what is today Saudi Arabia.

Land of Azd Pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre- ...

* Banu Hamdan

Banu Hamdan (; Ancient South Arabian script, Musnad: 𐩠𐩣𐩵𐩬) is an ancient, large, and prominent Arab tribe in northern Yemen.

Origins and location

The Hamdan stemmed from the eponymous progenitor Awsala (nickname Hamdan) whose descent ...

* Haubas

* Minaean Kingdom

* Old South Arabian

Ancient South Arabian (ASA; also known as Old South Arabian, Epigraphic South Arabian, Ṣayhadic, or Yemenite) is a group of four closely related extinct languages ( Sabaean/Sabaic, Qatabanic, Hadramitic, Minaic) spoken in the far southern ...

, a group of languages

* Qataban

Qataban () was an ancient Yemenite kingdom in South Arabia that existed from the early 1st millennium BCE to the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.

It was one of the six ancient South Arabian kingdoms of ancient Yemen, along with Sabaʾ, Maʿīn ...

* Rada'a

Rada'a is one of the cities of the Yemen, Republic of Yemen. It is situated in the southeastern region of the capital city of Sana'a, approximately 150 kilometers away from it, at an elevation of approximately 2100 meters above sea level. Geogra ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * *External links

"Queen of Sheba mystifies at the Bowers"

– UC Irvine news article on Queen of Sheba exhibit at the Bowers Museum

from the ''Saudi Aramco World'' online – March/April 1978

Queen of Sheba Temple restored (2000, BBC)

*William Leo Hansberry, E. Harper Johnson

"Africa's Golden Past: Queen of Sheba's true identity confounds historical research"

''

Ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus '' Diospyros'', which also includes the persimmon tree. A few ''Diospyros'' species, such as macassar and mun ebony, are dense enough to sink in water. Ebony is fin ...

'', April 1965, p. 136 — thorough discussion of previous scholars associating Biblical Sheba with Ethiopia.

S. Arabian "Inscription of Abraha" in the Sabaean language

, at Smithsonian/NMNH website

Saba'

(

Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

)

{{Authority control

275 disestablishments

States and territories established in the 10th century BC

States and territories disestablished in the 3rd century

Ancient peoples

Arabian Peninsula

Hebrew Bible places

Sabaeans

Quranic places

Book of Genesis

History of South Arabia

Former kingdoms

Ancient Arab peoples

Semitic-speaking peoples

Tribes of Arabia

Yemeni tribes