Senator Ted Kennedy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a

Kennedy was admitted to the

Kennedy was admitted to the

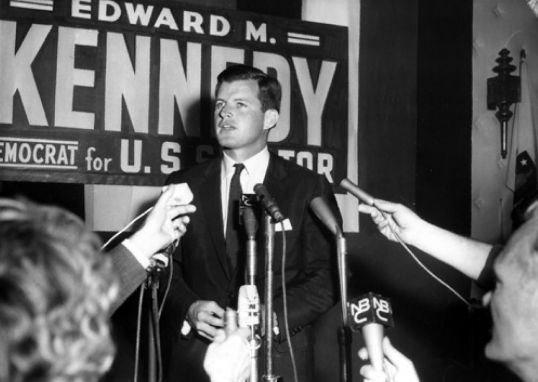

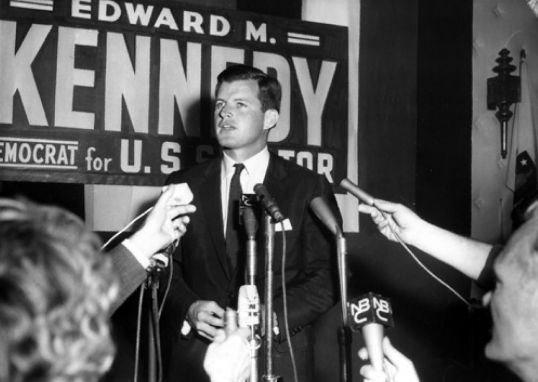

In the 1962 U.S. Senate special election in Massachusetts, Kennedy initially faced a Democratic Party primary challenge from

In the 1962 U.S. Senate special election in Massachusetts, Kennedy initially faced a Democratic Party primary challenge from

On June 19, 1964, Kennedy was a passenger in a private

On June 19, 1964, Kennedy was a passenger in a private  At the chaotic August

At the chaotic August

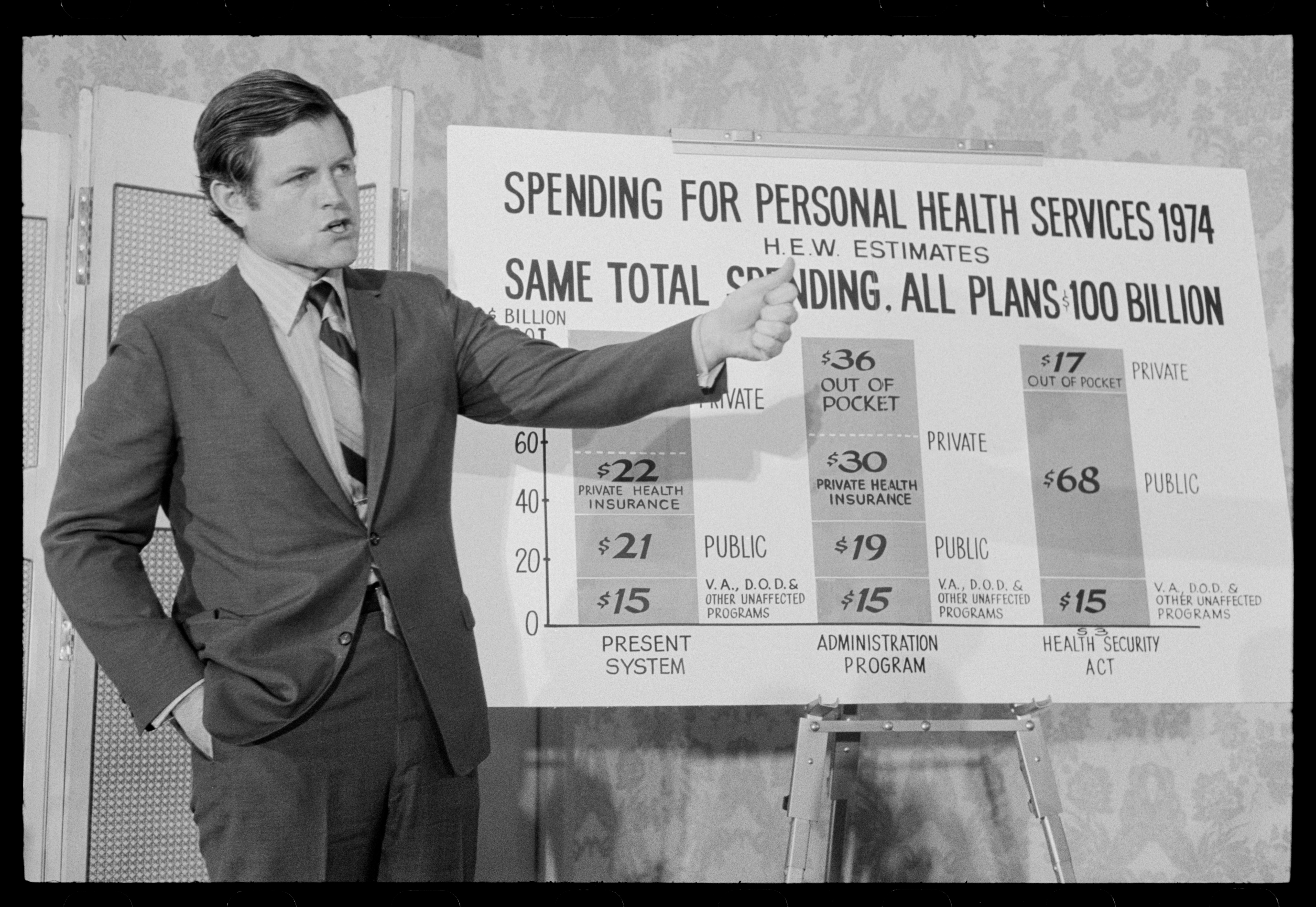

At the end of 1968, Kennedy had joined the new Committee for National Health Insurance at the invitation of its founder,

At the end of 1968, Kennedy had joined the new Committee for National Health Insurance at the invitation of its founder,  In January 1971, Kennedy lost his position as

In January 1971, Kennedy lost his position as

The 1980 election saw the Republicans capture not just the presidency but control of the Senate as well, and Kennedy was in the minority party for the first time in his career. Kennedy did not dwell upon his presidential loss, but instead reaffirmed his public commitment to American liberalism.Clymer, ''A Biography'', pp. 321–322. He chose to become the ranking member of the

The 1980 election saw the Republicans capture not just the presidency but control of the Senate as well, and Kennedy was in the minority party for the first time in his career. Kennedy did not dwell upon his presidential loss, but instead reaffirmed his public commitment to American liberalism.Clymer, ''A Biography'', pp. 321–322. He chose to become the ranking member of the  After again considering a candidacy for the 1988 presidential election, in December 1985 Kennedy publicly cut short any talk that he might run. This decision was influenced by his personal difficulties, family concerns, and content with remaining in the Senate. He added: "I know this decision means I may never be president. But the pursuit of the presidency is not my life. Public service is." Kennedy used his legislative skills to achieve passage of the COBRA Act, which extended employer-based health benefits after leaving a job. Following the 1986 congressional elections, the Democrats regained control of the Senate, and Kennedy became chair of the Labor and Public Welfare Committee. By now Kennedy had become what colleague, future

After again considering a candidacy for the 1988 presidential election, in December 1985 Kennedy publicly cut short any talk that he might run. This decision was influenced by his personal difficulties, family concerns, and content with remaining in the Senate. He added: "I know this decision means I may never be president. But the pursuit of the presidency is not my life. Public service is." Kennedy used his legislative skills to achieve passage of the COBRA Act, which extended employer-based health benefits after leaving a job. Following the 1986 congressional elections, the Democrats regained control of the Senate, and Kennedy became chair of the Labor and Public Welfare Committee. By now Kennedy had become what colleague, future

In the

In the

In 1996, Kennedy secured an increase in the

In 1996, Kennedy secured an increase in the

Kennedy had an easy time with his re-election to the Senate in 2000, as Republican lawyer and entrepreneur Jack E. Robinson III was sufficiently damaged by his past personal record that Republican state party officials refused to endorse him. Kennedy got 73 percent of the general election vote, with Robinson splitting the rest with

Kennedy had an easy time with his re-election to the Senate in 2000, as Republican lawyer and entrepreneur Jack E. Robinson III was sufficiently damaged by his past personal record that Republican state party officials refused to endorse him. Kennedy got 73 percent of the general election vote, with Robinson splitting the rest with  In reaction to the attacks, Kennedy was a supporter of the American-led 2001 overthrow of the

In reaction to the attacks, Kennedy was a supporter of the American-led 2001 overthrow of the

United States senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and p ...

from Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

and the prominent political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studi ...

Kennedy family

The Kennedy family is an American political family that has long been prominent in American politics, public service, entertainment, and business. In 1884, 35 years after the family's arrival from Ireland, Patrick Joseph "P. J." Kennedy be ...

, he was the second most senior member of the Senate when he died. He is ranked fifth in United States history for length of continuous service as a senator. Kennedy was the younger brother of President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

and U.S. attorney general and U.S. senator Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, a ...

. He was the father of Congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivale ...

Patrick J. Kennedy.

After attending Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

and earning his law degree from the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with College admission ...

, Kennedy began his career as an assistant district attorney in Suffolk County, Massachusetts. Kennedy was 30 years old when he first entered the Senate, winning a November 1962 special election in Massachusetts to fill the vacant seat previously held by his brother John, who had taken office as the US president. He was elected to a full six-year term in 1964 and was later re-elected seven more times. The Chappaquiddick incident

The Chappaquiddick incident occurred on Chappaquiddick Island in Massachusetts some time around midnight between July 18 and 19, 1969, when Senator Edward M. "Ted" Kennedy negligently drove his car off a narrow bridge, causing it to overturn ...

in 1969 resulted in the death of his automobile passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne

Mary Jo Kopechne (; July 26, 1940 – July 18 or 19, 1969) was an American secretary, and one of the campaign workers for U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy's 1968 presidential campaign, a close team known as the " Boiler Room Girls". In 1969, she ...

. He pleaded guilty to a charge of leaving the scene of an accident and later received a two-month suspended sentence

A suspended sentence is a sentence on conviction for a criminal offence, the serving of which the court orders to be deferred in order to allow the defendant to perform a period of probation. If the defendant does not break the law during that ...

. The incident and its aftermath hindered his chances of ever becoming president. He ran in 1980 in the Democratic primary campaign for president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

, but lost to the incumbent president, Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 19 ...

.

Kennedy was known for his oratorical skills. His 1968 eulogy for his brother Robert and his 1980 rallying cry for modern American liberalism

Modern liberalism in the United States, often simply referred to in the United States as liberalism, is a form of social liberalism found in American politics. It combines ideas of civil liberty and equality with support for social justice an ...

were among his best-known speeches. He became recognized as "The Lion of the Senate" through his long tenure and influence. Kennedy and his staff wrote more than 300 bills that were enacted into law. Unabashedly liberal, Kennedy championed an interventionist government that emphasized economic

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with t ...

and social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, Equal opportunity, opportunities, and Social privilege, privileges within a society. In Western Civilization, Western and Culture of Asia, Asian cultures, the concept of social ...

, but he was also known for working with Republicans to find compromises. Kennedy played a major role in passing many laws, including the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act and more recently as the 1965 Immigration Act, is a federal law passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The la ...

, the National Cancer Act of 1971

The "war on cancer" is the effort to find a cure for cancer by increased research to improve the understanding of cancer biology and the development of more effective cancer treatments, such as targeted drug therapies. The aim of such efforts is t ...

, the COBRA health insurance provision, the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986

The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 was a law enacted by the United States Congress. The law imposed sanctions against South Africa and stated five preconditions for lifting the sanctions that would essentially end the system of apar ...

, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 or ADA () is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination based on disability. It affords similar protections against discrimination to Americans with disabilities as the Civil Rights Act of 196 ...

, the Ryan White AIDS Care Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1991

The Civil Rights Act of 1991 is a United States labor law, passed in response to United States Supreme Court decisions that limited the rights of employees who had sued their employers for discrimination. The Act represented the first effort since ...

, the Mental Health Parity Act

The Mental Health Parity Act (MHPA) is legislation signed into United States law on September 26, 1996 that requires annual or lifetime dollar limits on mental health benefits to be no lower than any such dollar limits for medical and surgical be ...

, the S-CHIP children's health program, the No Child Left Behind Act

The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) was a U.S. Act of Congress that reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act; it included Title I provisions applying to disadvantaged students. It supported standards-based educati ...

, and the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act. During the 2000s, he led several unsuccessful immigration reform

Immigration reform is change to the current immigration policy of a country. In its strict definition, ''reform'' means "to change into an improved form or condition, by amending or removing faults or abuses". In the political sense, "immigration ...

efforts. Over the course of his Senate career, Kennedy made efforts to enact universal health care

Universal health care (also called universal health coverage, universal coverage, or universal care) is a health care system in which all residents of a particular country or region are assured access to health care. It is generally organized ar ...

, which he called the "cause of my life". By the later years of his life, Kennedy had come to be viewed as a major figure and spokesman for American progressivism

Progressivism in the United States is a political philosophy and reform movement in the United States advocating for policies that are generally considered left-wing, left-wing populist, libertarian socialist, social democratic, and environmentali ...

.

On August 25, 2009, Kennedy died of a malignant

Malignancy () is the tendency of a medical condition to become progressively worse.

Malignancy is most familiar as a characterization of cancer. A ''malignant'' tumor contrasts with a non-cancerous ''benign'' tumor in that a malignancy is not s ...

brain tumor

A brain tumor occurs when abnormal cells form within the brain. There are two main types of tumors: malignant tumors and benign (non-cancerous) tumors. These can be further classified as primary tumors, which start within the brain, and secon ...

(glioblastoma

Glioblastoma, previously known as glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), is one of the most aggressive types of cancer that begin within the brain. Initially, signs and symptoms of glioblastoma are nonspecific. They may include headaches, personality cha ...

) at his home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts

Hyannis Port (or Hyannisport) is a small residential village located in Barnstable, Massachusetts, United States. It is an affluent summer community on Hyannis Harbor, 1.4 miles (2.3 km) to the south-southwest of Hyannis.

Community

It has ...

, at the age of 77. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

near his brothers John and Robert.

Early life

Kennedy was born on February 22, 1932, at St. Margaret's Hospital in the Dorchester section ofBoston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

. He was the youngest of the nine children of Joseph Patrick Kennedy and Rose Fitzgerald

Rose Elizabeth Fitzgerald Kennedy (July 22, 1890 – January 22, 1995) was an American philanthropist, socialite, and matriarch of the Kennedy family. She was deeply embedded in the " lace curtain" Irish American community in Boston. Her father ...

, members of prominent Irish American

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

families in Boston. They constituted one of the wealthiest families in the nation after their marriage. His eight siblings were Joseph Jr., John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Seco ...

, Rosemary

''Salvia rosmarinus'' (), commonly known as rosemary, is a shrub with fragrant, evergreen, needle-like leaves and white, pink, purple, or blue flowers, native to the Mediterranean region. Until 2017, it was known by the scientific name ''Rosma ...

, Kathleen, Eunice

Eunice is a feminine given name, from the Greek Εὐνίκη, ''Euníkē'', from "eu", good, and "níkē", victory. Eunice is also a relatively rare last name, found in Nigeria and the Southeastern United States, chiefly Louisiana and Georgia.

Pe ...

, Patricia

Patricia is a female given name of Latin origin. Derived from the Latin word ''patrician'', meaning "noble"; it is the feminine form of the masculine given name Patrick. The name Patricia was the second most common female name in the United State ...

, Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, h ...

, and Jean

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* Jean ...

. His older brother John asked to be the newborn's godfather, a request his parents honored, though they did not agree to his request to name the baby George Washington Kennedy (Ted was born on President George Washington's 200th birthday). They named the boy after their father's assistant.

As a child, Ted was frequently uprooted by his family's moves among Bronxville, New York; Hyannis Port, Massachusetts

Hyannis Port (or Hyannisport) is a small residential village located in Barnstable, Massachusetts, United States. It is an affluent summer community on Hyannis Harbor, 1.4 miles (2.3 km) to the south-southwest of Hyannis.

Community

It has ...

; Palm Beach, Florida

Palm Beach is an incorporated town in Palm Beach County, Florida. Located on a barrier island in east-central Palm Beach County, the town is separated from several nearby cities including West Palm Beach and Lake Worth Beach by the Intraco ...

; and the Court of St. James's

The Court of St James's is the royal court for the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. All ambassadors to the United Kingdom are formally received by the court. All ambassadors from the United Kingdom are formally accredited from the court – &n ...

, in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, England. His formal education started at Gibbs School in Kensington, London. He had attended ten schools by the age of eleven; these disruptions that interfered with his academic success. He was an altar boy

An altar server is a laity, lay assistant to a member of the clergy during a Christian liturgy. An altar server attends to supporting tasks at the altar such as fetching and carrying, ringing the altar bell, helps bring up the gifts, brings up t ...

at the St. Joseph's Church and was seven when he received his First Communion

First Communion is a ceremony in some Christian traditions during which a person of the church first receives the Eucharist. It is most common in many parts of the Latin Church tradition of the Catholic Church, Lutheran Church and Anglican Communi ...

from Pope Pius XII in the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

. He spent sixth and seventh grades at the Fessenden School

The Fessenden School is an independent day (Pre-K – Grade 9) and boarding school (Grades 5 – 9) for boys, founded in 1903 by Frederick J. Fessenden as a school for the intellectually gifted, and located at 250 Waltham Street, West Newton, ...

, where he was a mediocre student, and eighth grade at Cranwell Preparatory School; both schools located in Massachusetts. He was the youngest child and his parents were affectionate toward him, but they also compared him unfavorably with his older brothers.

Between the ages of eight and sixteen, Ted suffered the traumas of his sister Rosemary's failed lobotomy

A lobotomy, or leucotomy, is a form of neurosurgical treatment for psychiatric disorder or neurological disorder (e.g. epilepsy) that involves severing connections in the brain's prefrontal cortex. The surgery causes most of the connections t ...

and the deaths of two siblings: Joseph Jr. in World War II and Kathleen in an airplane crash. Ted's affable maternal grandfather, John F. Fitzgerald

John Francis "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald (February 11, 1863 – October 2, 1950) was an American Democratic politician from Boston, Massachusetts. He served as a U.S. Representative and Mayor of Boston. He also made unsuccessful runs for the United ...

, was the Mayor of Boston

The mayor of Boston is the head of the municipal government in Boston, Massachusetts. Boston has a mayor–council government. Boston's mayoral elections are nonpartisan (as are all municipal elections in Boston), and elect a mayor to a four- ...

, a U.S. Congressman, and an early political and personal influence. Ted spent his four high-school years at Milton Academy

Milton Academy (also known as Milton) is a highly selective, coeducational, University-preparatory school, independent preparatory, boarding and day school in Milton, Massachusetts consisting of a grade 9–12 Upper School and a grade K–8 Lowe ...

, a preparatory school in Milton, Massachusetts

Milton is a town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States and an affluent suburb of Boston. The population was 28,630 at the 2020 census. Milton is the birthplace of former U.S. President George H. W. Bush, and architect Buckminster Fuller ...

, where he received B and C grades. In 1950, he finished 36th in a graduating class of 56. He did well at football there, playing on the varsity in his last two years; the school's headmaster later described his play as "absolutely fearless ... he would have tackled an express train to New York if you asked ... he loved contact sports". Kennedy also played on the tennis team and was in the drama, debate, and glee clubs.

College, military service, and law school

Like his father and brothers before him, Ted graduated fromHarvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher ...

. In his spring semester, he was assigned to the athlete-oriented Winthrop House

John Winthrop House (commonly Winthrop House) is one of twelve undergraduate residential Houses at Harvard University. It is home to approximately 400 upperclass undergraduates.

Winthrop house consists of two buildings, Standish Hall and Gore ...

, where his brothers had also lived. He was an offensive and defensive end on the freshman football team; his play was characterized by his large size and fearless style. In his first semester, Kennedy and his classmates arranged to copy answers from another student during the final examination for a science class. At the end of his second semester in May 1951, Kennedy was anxious about maintaining his eligibility for athletics for the next year, and he had a classmate take his place at a Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

** Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Ca ...

exam. The ruse was immediately discovered, and both students were expelled for cheating. In a standard Harvard treatment for serious disciplinary cases, they were told they could apply for readmission within a year or two if they demonstrated good behavior during that time.

In June 1951, Kennedy enlisted in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

and signed up for an optional four-year term that was shortened to the minimum of two years after his father intervened. Following basic training

Military recruit training, commonly known as basic training or boot camp, refers to the initial instruction of new military personnel. It is a physically and psychologically intensive process, which resocializes its subjects for the unique deman ...

at Fort Dix

Fort Dix, the common name for the Army Support Activity (ASA) located at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, is a United States Army post. It is located south-southeast of Trenton, New Jersey. Fort Dix is under the jurisdiction of the Air Force A ...

in New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York (state), New York; on the ea ...

, he requested assignment to Fort Holabird

Fort Holabird was a United States Army post in the city of Baltimore, Maryland, active from 1918 to 1973.

History

Fort Holabird was located in the southeast corner of Baltimore and northwest of the suburban developments of Dundalk, Maryland, in s ...

in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; ...

for Army Intelligence training, but was dropped without explanation after a few weeks. He went to Camp Gordon

Fort Gordon, formerly known as Camp Gordon, is a United States Army installation established in October 1941. It is the current home of the United States Army Signal Corps, United States Army Cyber Command, and the Cyber Center of Excellence. It ...

in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to t ...

for training in the Military Police Corps. In June 1952, Kennedy was assigned to the honor guard

A guard of honour ( GB), also honor guard ( US), also ceremonial guard, is a group of people, usually military in nature, appointed to receive or guard a head of state or other dignitaries, the fallen in war, or to attend at state ceremonials, ...

at SHAPE

A shape or figure is a graphical representation of an object or its external boundary, outline, or external surface, as opposed to other properties such as color, texture, or material type.

A plane shape or plane figure is constrained to lie on ...

headquarters in Paris, France. His father's political connections ensured that he was not deployed to the ongoing Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top: ...

. While stationed in Europe, Kennedy traveled extensively on weekends and climbed the Matterhorn

The (, ; it, Cervino, ; french: Cervin, ; rm, Matterhorn) is a mountain of the Alps, straddling the main watershed and border between Switzerland and Italy. It is a large, near-symmetric pyramidal peak in the extended Monte Rosa area of th ...

in the Pennine Alps

The Pennine Alps (german: Walliser Alpen, french: Alpes valaisannes, it, Alpi Pennine, la, Alpes Poeninae), also known as the Valais Alps, are a mountain range in the western part of the Alps. They are located in Switzerland (Valais) and Italy ...

. After 21 months, he was discharged in March 1953 as a private first class.

Kennedy re-entered Harvard in the summer of 1953 and improved his study habits. His brother John was a U.S. Senator and the family was attracting more public attention. Ted joined The Owl final club

Harvard College has several types of social clubs. These are split between gender-inclusive clubs recognized by the college, and unrecognized single-gender clubs which are subject to College sanctions. The Hasty Pudding Club holds claim as the old ...

in 1954 and was also chosen for the Hasty Pudding Club

The Hasty Pudding Club, often referred to simply as the Pudding, is a social club at Harvard University, and one of three sub-organizations that comprise the Hasty Pudding - Institute of 1770. The club's motto, ''Concordia Discors'' (discordant h ...

and the Pi Eta fraternity. Kennedy was on athletic probation during his sophomore year, and he returned as a second-string two-way end for the Crimson football team during his junior year. He barely missed earning his varsity letter

A varsity letter (or monogram) is an award earned in the United States for excellence in school activities. A varsity letter signifies that its recipient was a qualified varsity team member, awarded after a certain standard was met.

Description ...

. He received a recruiting feeler from Green Bay Packers

The Green Bay Packers are a professional American football team based in Green Bay, Wisconsin. The Packers compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member club of the National Football Conference (NFC) North division. It is the th ...

head coach Lisle Blackbourn

Lisle William "Liz" Blackbourn (June 3, 1899 – June 14, 1983) was an American football coach in Wisconsin, most notably as the third head coach of the Green Bay Packers, from 1954 through 1957, and the final head coach at Marquette University ...

, who asked him about his interest in playing professional football. Kennedy demurred, saying he had plans to attend law school and to "go into another contact sport, politics." In his senior season of 1955, Kennedy started at end for the Harvard football team and worked hard to improve his blocking and tackling to complement his , size. In the season-ending Harvard-Yale game in the snow at the Yale Bowl

The Yale Bowl Stadium is a college football stadium in the northeast United States, located in New Haven, Connecticut, on the border of West Haven, about 1½ miles (2½ km) west of the main campus of Yale University. The home of the American fo ...

on November 19 (which Yale won 21–7), Kennedy caught a pass to score Harvard's only touchdown; the team finished the season with a 3–4–1 record. Academically, Kennedy received mediocre grades for his first three years, improved to a B average for his senior year, and finished barely in the top half of his class. Kennedy graduated from Harvard at age 24 in 1956 with an AB in history and government.

Due to his low grades, Kennedy was not accepted by Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each class ...

. He instead followed his brother Bobby and enrolled in the University of Virginia School of Law

The University of Virginia School of Law (Virginia Law or UVA Law) is the law school of the University of Virginia, a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson as part of his "academical v ...

in 1956. That acceptance was controversial among faculty and alumni, who judged Kennedy's past cheating episodes at Harvard to be incompatible with the University of Virginia's honor code; it took a full faculty vote to admit him. Kennedy also attended The Hague Academy of International Law

The Hague Academy of International Law (french: Académie de droit international de La Haye) is a center for high-level education in both public and private international law housed in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands. Courses are taug ...

during one summer. At Virginia, Kennedy felt that he had to study "four times as hard and four times as long" as other students to keep up with them. He received mostly C grades and was in the middle of the class ranking, but won the prestigious William Minor Lile Moot Court Competition. He was elected head of the Student Legal Forum and brought many prominent speakers to the campus via his family connections. While there, his questionable automotive practices were curtailed when he was charged with reckless driving

In United States law, reckless driving is a major moving traffic violation that generally consists in driving a vehicle with willful or wanton disregard for the safety of persons or property. It is usually a more serious offense than careless ...

and driving without a license

A driver's license is a legal authorization, or the official document confirming such an authorization, for a specific individual to operate one or more types of motorized vehicles—such as motorcycles, cars, trucks, or buses—on a public r ...

. While attending law school, he was officially named as manager of his brother John's 1958 Senate re-election campaign; Ted's ability to connect with ordinary voters on the street helped bring a record-setting victory margin that gave credibility to John's presidential aspirations. Ted graduated from law school in 1959.

Family and early career

In October 1957 (early in his second year of law school), Kennedy metJoan Bennett

Joan Geraldine Bennett (February 27, 1910 – December 7, 1990) was an American stage, film, and television actress. She came from a show-business family, one of three acting sisters. Beginning her career on the stage, Bennett appeared in more t ...

at Manhattanville College

Manhattanville College is a private university in Purchase, New York. Founded in 1841 at 412 Houston Street in lower Manhattan, it was initially known as Academy of the Sacred Heart, then after 1847 as Manhattanville College of the Sacred Hea ...

; they were introduced after a dedication speech for a gymnasium that his family had donated at the campus. Bennett was a senior at Manhattanville and had worked as a model and won beauty contests, but she was unfamiliar with the world of politics. After the couple became engaged, she grew nervous about marrying someone she did not know that well, but Joe Kennedy insisted that the wedding should proceed. The couple was married by Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**'' Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**'' Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, ...

Francis Spellman

Francis Joseph Spellman (May 4, 1889 – December 2, 1967) was an American bishop and cardinal of the Catholic Church. From 1939 until his death in 1967, he served as the sixth Archbishop of New York; he had previously served as an auxiliar ...

on November 29, 1958, at St. Joseph's Church in Bronxville, New York, with the reception being held at the nearby Siwanoy Country Club

Siwanoy Country Club is a country club located in Bronxville, New York. The club hosted the first PGA Championship in 1916, which was won by Jim Barnes.

History

The Club was incorporated on May 20, 1901 at the Westchester County Clerk's office ...

. Ted and Joan had three children: Kara

Kara or KARA may refer to:

Geography Localities

* Kara, Chad, a sub-prefecture

* Kára, Hungary, a village

* Kara, Uttar Pradesh, India, a township

* Kara, Iran, a village in Lorestan Province

* Kara, Republic of Dagestan, a rural locality in D ...

(1960–2011), Ted Jr. (b. 1961) and Patrick (b. 1967). By the 1970s, the marriage was in trouble due to Ted's infidelity

Infidelity (synonyms include cheating, straying, adultery, being unfaithful, two-timing, or having an affair) is a violation of a couple's emotional and/or sexual exclusivity that commonly results in feelings of anger, sexual jealousy, and ri ...

and Joan's growing alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomina ...

.

Kennedy was admitted to the

Kennedy was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar

The Massachusetts Bar Association (MBA) is a voluntary, non-profit bar association in Massachusetts with a headquarters on West Street in Boston's Downtown Crossing. The MBA also has a Western Massachusetts office.

The purpose of the MBA is t ...

in 1959. In 1960, his brother John announced his candidacy for President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

and Ted managed his campaign in the Western states. Ted learned to fly and during the Democratic primary campaign he barnstormed around the western states, meeting with delegates and bonding with them by trying his hand at ski jumping

Ski jumping is a winter sport in which competitors aim to achieve the farthest jump after sliding down on their skis from a specially designed curved ramp. Along with jump length, competitor's aerial style and other factors also affect the fin ...

and bronc riding

Bronc riding, either bareback bronc or saddle bronc competition, is a rodeo event that involves a rodeo participant riding a bucking horse (sometimes called a ''bronc'' or ''bronco'') that attempts to throw or buck off the rider. Originally ba ...

. The seven weeks he spent in Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

helped his brother win the first contested primary of the season there and a similar time spent in Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the sou ...

was rewarded when a unanimous vote from that state's delegates put his brother over the top at the 1960 Democratic National Convention

The 1960 Democratic National Convention was held in Los Angeles, California, on July 11–15, 1960. It nominated Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts for president and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas for vice president.

...

.

Following his victory in the presidential election, John resigned from his seat as U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, but Ted was not eligible to fill the vacancy until his thirtieth birthday on February 22, 1962. Ted initially wanted to stay out west and do something other than run for office right away; he said, "The disadvantage of my position is being constantly compared with two brothers of such superior ability." Ted's brothers were not in favor of his running immediately, but Ted ultimately coveted the Senate seat as an accomplishment to match his brothers, and their father overruled them. Therefore, John asked Massachusetts Governor Foster Furcolo

John Foster Furcolo (July 29, 1911 – July 5, 1995) was an American lawyer, writer, and Democratic Party politician from Massachusetts. He was the state's 60th governor, and also represented the state as a member of the United States House of ...

to name Kennedy family friend Ben Smith as interim senator for John's unexpired term, which he did in December 1960. This kept the seat available for Ted.

Meanwhile, Ted started work in February 1961 as an assistant district attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a l ...

for Suffolk County, Massachusetts (for which he took a nominal $1 salary), where he first developed a hard-nosed attitude towards crime. He took many overseas trips, billed as fact-finding tours with the goal of improving his foreign policy credentials. On a nine-nation Latin American

Latin Americans ( es, Latinoamericanos; pt, Latino-americanos; ) are the citizens of Latin American countries (or people with cultural, ancestral or national origins in Latin America). Latin American countries and their diasporas are multi-et ...

trip in 1961, FBI reports from the time showed Kennedy meeting with Lauchlin Currie

Lauchlin Bernard Currie (October 8, 1902 – December 23, 1993) worked as White House economic adviser to President Franklin Roosevelt during World War II (1939–45). From 1949 to 1953, he directed a major World Bank mission to Colombia and r ...

, an alleged former Soviet spy, together with locals in each country whom the reports deemed left-wingers and Communist sympathizers. Reports from the FBI and other sources had Kennedy renting a brothel and opening up bordellos after hours during the tour. The Latin American trip helped to formulate Kennedy's foreign policy views, and in subsequent ''Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'' columns he warned that the region might turn to Communism if the U.S. did not reach out to it in a more effective way. Kennedy also began speaking to local political clubs and organizations.

In the 1962 U.S. Senate special election in Massachusetts, Kennedy initially faced a Democratic Party primary challenge from

In the 1962 U.S. Senate special election in Massachusetts, Kennedy initially faced a Democratic Party primary challenge from Edward J. McCormack Jr.

Edward Joseph McCormack Jr. (August 29, 1923 – February 27, 1997), was an American attorney and politician from Massachusetts. He was most notable for serving as Massachusetts Attorney General from 1959 through 1963.

Personal life and educat ...

, the state Attorney General

The state attorney general in each of the 50 U.S. states, of the federal district, or of any of the territories is the chief legal advisor to the state government and the state's chief law enforcement officer. In some states, the attorney gen ...

. Kennedy's slogan was "He can do more for Massachusetts", the same one John had used in his first campaign for the seat ten years earlier. McCormack had the support of many liberals and intellectuals, who thought Kennedy inexperienced and knew of his suspension from Harvard, a fact which later became public during the race. Kennedy also faced the notion that with one brother President and another U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

, "Don't you think that Teddy is one Kennedy too many?" But Kennedy proved to be an effective street-level campaigner. In a televised debate, McCormack said "The office of United States Senator should be merited, and not inherited," and said that if his opponent's name was Edward Moore, not Edward Moore Kennedy, his candidacy "would be a joke". Voters thought McCormack's performance overbearing, and with the family political machine's finally getting fully behind him, Kennedy won the September 1962 primary by a two-to-one margin. In the November special election, Kennedy defeated Republican George Cabot Lodge II

George Cabot Lodge II (born July 7, 1927) is an American professor and former politician. In 1962, he was the Republican nominee for a special election to succeed John F. Kennedy in the United States Senate, but was defeated by Ted Kennedy. He ...

, product of another noted Massachusetts political family, gaining 55 percent of the vote.

United States Senator

First years, brothers' assassinations

Kennedy was sworn into the Senate on November 7, 1962. He maintained a deferential attitude towards the older, seniority-laden Southern members when he first entered the Senate, avoiding publicity and focusing on committee work and local issues. Compared to his brothers in office, he lacked John's sophistication and Robert's intense, sometimes grating drive, but was more affable than either of them. He was favored by SenatorJames Eastland

James Oliver Eastland (November 28, 1904 February 19, 1986) was an American attorney, plantation owner, and politician from Mississippi. A Democrat, he served in the United States Senate in 1941 and again from 1943 until his resignation on Dece ...

, chair of the powerful Judiciary Committee. Vice President Lyndon Johnson, despite his feuds with John and Robert Kennedy, liked Ted and told close aides that he “had the potential to be the best politician in the whole family.”

On November 22, 1963, Kennedy was presiding over the Senate—a task given to junior members—when an aide rushed in to tell him that his brother, President Kennedy, had been shot. His brother Robert soon told him that the President was dead. Ted and his sister Eunice Kennedy Shriver

Eunice Mary Kennedy Shriver (July 10, 1921 – August 11, 2009) was an American philanthropist and a member of the Kennedy family. She was the founder of the Special Olympics, a sports organization for persons with physical and intellectual dis ...

immediately flew to the family home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts

Hyannis Port (or Hyannisport) is a small residential village located in Barnstable, Massachusetts, United States. It is an affluent summer community on Hyannis Harbor, 1.4 miles (2.3 km) to the south-southwest of Hyannis.

Community

It has ...

, to give the news to their invalid father, who had been afflicted by a stroke suffered two years earlier.

On June 19, 1964, Kennedy was a passenger in a private

On June 19, 1964, Kennedy was a passenger in a private Aero Commander 680

The Aero Commander 500 family is a series of light-twin piston-engined and turboprop aircraft originally built by the Aero Design and Engineering Company in the late 1940s, renamed the Aero Commander company in 1950, and a division of Rockwell ...

airplane that was flying in bad weather from Washington to Massachusetts. The plane crashed into an apple orchard in the western Massachusetts

Western Massachusetts, known colloquially as “Western Mass,” is a region in Massachusetts, one of the six U.S. states that make up the New England region of the United States. Western Massachusetts has diverse topography; 22 colleges and u ...

town of Southampton

Southampton () is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire, S ...

on the final approach

In aeronautics, the final approach (also called the final leg and final approach leg) is the last leg in an aircraft's approach to landing, when the aircraft is lined up with the runway and descending for landing.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of ...

to the Barnes Municipal Airport

Westfield-Barnes Regional Airport is a joint civil-military airport in Hampden County, Massachusetts, three miles (6 km) north of Westfield and northwest of Springfield. It was formerly Barnes Municipal Airport; the National Plan of Integ ...

in Westfield

Westfield may refer to:

Places Australia

* Westfield, Western Australia Canada

*Grand Bay-Westfield, New Brunswick

*Westfield, Nova Scotia

New Zealand

*Westfield, New Zealand United Kingdom England

* Westfield, Cumbria, a location

* Westfield, E ...

. The pilot and Edward Moss (one of Kennedy's aides) were killed. Kennedy was pulled from the wreckage by fellow Senator Birch Bayh

Birch Evans Bayh Jr. (; January 22, 1928 – March 14, 2019) was an American Democratic Party politician who served as U.S. Senator from Indiana from 1963 to 1981. He was first elected to office in 1954, when he won election to the Indiana ...

, and spent months in a hospital recovering from a severe back injury, a punctured lung

A pneumothorax is an abnormal collection of air in the pleural space between the lung and the chest wall. Symptoms typically include sudden onset of sharp, one-sided chest pain and shortness of breath. In a minority of cases, a one-way valve i ...

, broken ribs and internal bleeding. He suffered chronic back pain for the rest of his life as a result of the accident. Kennedy took advantage of his long convalescence to meet with academics and study issues more closely, and the hospital experience triggered his lifelong interest in the provision of health care

Health care or healthcare is the improvement of health via the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other physical and mental impairments in people. Health care is delivered by health ...

services. His wife Joan did the campaigning for him in the regular 1964 U.S. Senate election in Massachusetts, and he defeated his Republican opponent by a three-to-one margin.

Kennedy was walking with a cane when he returned to the Senate in January 1965. He employed a stronger and more effective legislative staff. He took on President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

and almost succeeded in amending the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The suffrage, Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of Federal government of the United States, federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President of the United ...

to explicitly ban the poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

at the state and local level (rather than just directing the Attorney General to challenge its constitutionality there), thereby gaining a reputation for legislative skill. He was a leader in pushing through the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act and more recently as the 1965 Immigration Act, is a federal law passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The la ...

, which ended a quota system based upon national origin. He also played a role in the creation of the National Teachers Corps

Teacher Corps, whose correct title was the National Teacher Corps, was a program established by the United States Congress in the Higher Education Act of 1965 to improve elementary and secondary teaching in predominantly low-income areas. Indiv ...

.

Following in the Cold Warrior path of his fallen brother, Kennedy initially said he had "no reservations" about the expanding U.S. role in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

and acknowledged that it would be a "long and enduring struggle". Kennedy held hearings on the plight of refugees in the conflict, which revealed that the U.S. government had no coherent policy for refugees. Kennedy also tried to reform "unfair" and "inequitable" aspects of the draft

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

. By the time of a January 1968 trip to Vietnam, Kennedy was disillusioned by the lack of U.S. progress, and suggested publicly that the U.S. should tell South Vietnam, "Shape up or we're going to ship out."

Ted initially advised his brother Robert against challenging the incumbent President Lyndon Johnson for the Democratic nomination in the 1968 presidential election. Once Eugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph McCarthy (March 29, 1916December 10, 2005) was an American politician, writer, and academic from Minnesota. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the United States Senate from 1959 to 1971. ...

's strong showing in the New Hampshire primary

The New Hampshire presidential primary is the first in a series of nationwide party primary elections and the second party contest (the first being the Iowa caucuses) held in the United States every four years as part of the process of choo ...

led to Robert's presidential campaign starting in March 1968, Ted recruited political leaders for endorsements to his brother in the western states. Ted was in San Francisco when his brother Robert won the crucial California primary on June 4, 1968, and then after midnight, Robert was shot in Los Angeles and died a day later. Ted Kennedy was devastated by his brother's death, as he was closest to Robert among those in the Kennedy family. Kennedy aide Frank Mankiewicz

Frank Fabian Mankiewicz II (May 16, 1924 – October 23, 2014) was an American journalist, political adviser, president of National Public Radio, and public relations executive.

Life and career

Frank Mankiewicz was born in New York City ...

said of seeing Ted at the hospital where Robert lay mortally wounded: "I have never, ever, nor do I expect ever, to see a face more in grief." At Robert's funeral, Kennedy eulogized his older brother:

At the chaotic August

At the chaotic August 1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus maki ...

, Mayor of Chicago Richard J. Daley

Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) was an American politician who served as the Mayor of Chicago from 1955 and the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party Central Committee from 1953 until his death. He has been ca ...

and some other party factions feared that Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing M ...

could not unite the party, and so encouraged Ted Kennedy to make himself available for a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a ves ...

. The 36-year-old Kennedy was seen as the natural heir to his brothers, and "Draft Ted" movements sprang up from various quarters and among delegates. Thinking that he was only being seen as a stand-in for his brother and that he was not ready for the job himself, and getting an uncertain reaction from McCarthy and a negative one from Southern delegates, Kennedy rejected any move to place his name before the convention as a candidate for the nomination. He also declined consideration for the vice-presidential spot. George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pre ...

remained the symbolic standard-bearer for Robert's delegates instead.

After the deaths of his brothers, Kennedy took on the role of a surrogate father for his 13 nephews and nieces. By some reports, he also negotiated the October 1968 marital contract between Jacqueline Kennedy

Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis ( ; July 28, 1929 – May 19, 1994) was an American socialite, writer, photographer, and book editor who served as first lady of the United States from 1961 to 1963, as the wife of President John F. Kennedy. A po ...

and Aristotle Onassis

Aristotle Socrates Onassis (, ; el, Αριστοτέλης Ωνάσης, Aristotélis Onásis, ; 20 January 1906 – 15 March 1975), was a Greek-Argentinian shipping magnate who amassed the world's largest privately-owned shipping fleet and was ...

.

Following Republican Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was t ...

's victory in November, Kennedy was widely assumed to be the front-runner for the 1972 Democratic nomination.Also published in the book ''The Last Lion: The Fall and Rise of Ted Kennedy'', Simon & Schuster, 2009, chapter 3.

In January 1969, Kennedy defeated Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a U.S. state, state in the Deep South and South Central United States, South Central regions of the United States. It is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 20th-smal ...

Senator Russell B. Long

Russell Billiu Long (November 3, 1918 – May 9, 2003) was an American Democratic politician and United States Senator from Louisiana from 1948 until 1987. Because of his seniority, he advanced to chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, servi ...

by a 31–26 margin to become Senate Majority Whip

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and members of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as the chief spokespersons for their respective political parties holding ...

, the youngest person to attain that position. While this further boosted his presidential image, he also appeared conflicted by the inevitability of having to run for the position; "Few who knew him doubted that in one sense he very much wanted to take that path", ''Time'' magazine reported, but "he had a fatalistic, almost doomed feeling about the prospect". The reluctance was in part due to the danger; Kennedy reportedly observed, "I know that I'm going to get my ass shot off one day, and I don't want to." Indeed, there were a constant series of death threats made against Kennedy for much of the rest of his career.

Chappaquiddick incident

On the night of July 18, 1969, Kennedy was atChappaquiddick Island

Chappaquiddick Island (Massachusett language: ''tchepi-aquidenet''; colloquially known as "Chappy"), a part of the town of Edgartown, Massachusetts, is a small peninsula and occasional island on the eastern end of Martha's Vineyard. Norton Poi ...

on the eastern end of Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the Northeastern United States, located south of Cape Cod in Dukes County, Massachusetts, known for being a popular, affluent summer colony. Martha's Vineyard includes th ...

. He was hosting a party for the Boiler Room Girls

The "Boiler Room Girls" was a nickname for a group of six women who worked as political advisors for Robert Kennedy's 1968 presidential campaign in a windowless work area in Kennedy's Washington, D.C. electoral offices. They were political strateg ...

, a group of young women who had worked on his brother Robert's ill-fated 1968 presidential campaign. Kennedy left the party with one of the women, 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne

Mary Jo Kopechne (; July 26, 1940 – July 18 or 19, 1969) was an American secretary, and one of the campaign workers for U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy's 1968 presidential campaign, a close team known as the " Boiler Room Girls". In 1969, she ...

.

Driving a 1967 Oldsmobile Delmont 88, he attempted to cross the Dike Bridge, which did not have a guardrail at that time. Kennedy lost control of his vehicle and crashed in the Poucha Pond

The Chappaquiddick incident occurred on Chappaquiddick Island in Massachusetts some time around midnight between July 18 and 19, 1969, when Senator Edward M. "Ted" Kennedy negligently drove his car off a narrow bridge, causing it to overturn i ...

inlet, which was a tidal channel on Chappaquiddick Island. Kennedy escaped from the overturned vehicle, and, by his description, dove below the surface seven or eight times, vainly attempting to reach and rescue Kopechne. Ultimately, he swam to shore and left the scene, with Kopechne still trapped inside the vehicle. Kennedy did not report the accident to authorities until the next morning, by which time Kopechne's body had already been discovered. Kennedy's cousin Joe Gargan later said that both he and Kennedy's friend Paul Markham

Paul Francis Markham (May 22, 1930 – July 13, 2019) was an American attorney who served as the United States Attorney for the District of Massachusetts from 1966 to 1969. He was one of two associates of Senator Edward M. Kennedy, in whom Kenn ...

, both of whom were at the party and came to the scene, had urged Kennedy to report it at the time.

A week after the incident, Kennedy pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident and was given a suspended sentence of two months in jail. That night, he gave a national broadcast in which he said, "I regard as indefensible the fact that I did not report the accident to the police immediately," but he denied driving under the influence of alcohol and also denied any immoral conduct between him and Kopechne. Kennedy asked the Massachusetts electorate whether he should stay in office or resign; after getting a favorable response in messages sent to him, Kennedy announced on July 30 that he would remain in the Senate and run for re-election the next year.

In January 1970, an inquest into Kopechne's death was held in Edgartown, Massachusetts

Edgartown is a tourist destination on the island of Martha's Vineyard in Dukes County, Massachusetts, United States, for which it is the county seat.

It was once a major whaling port, with historic houses that have been carefully preserved. To ...

. At the request of Kennedy's lawyers, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) is the highest court in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Although the claim is disputed by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, the SJC claims the distinction of being the oldest continuously functi ...

ordered the inquest to be conducted in secret. The presiding judge, James A. Boyle, concluded that some aspects of Kennedy's story of that night were not true, and that negligent driving "appears to have contributed" to the death of Kopechne. A grand jury

A grand jury is a jury—a group of citizens—empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a ...

on Martha's Vineyard conducted a two-day investigation in April 1970 but issued no indictment, after which Boyle made his inquest report public. Kennedy deemed its conclusions "not justified." Questions about the Chappaquiddick incident generated a large number of articles and books during the following years.

1970s

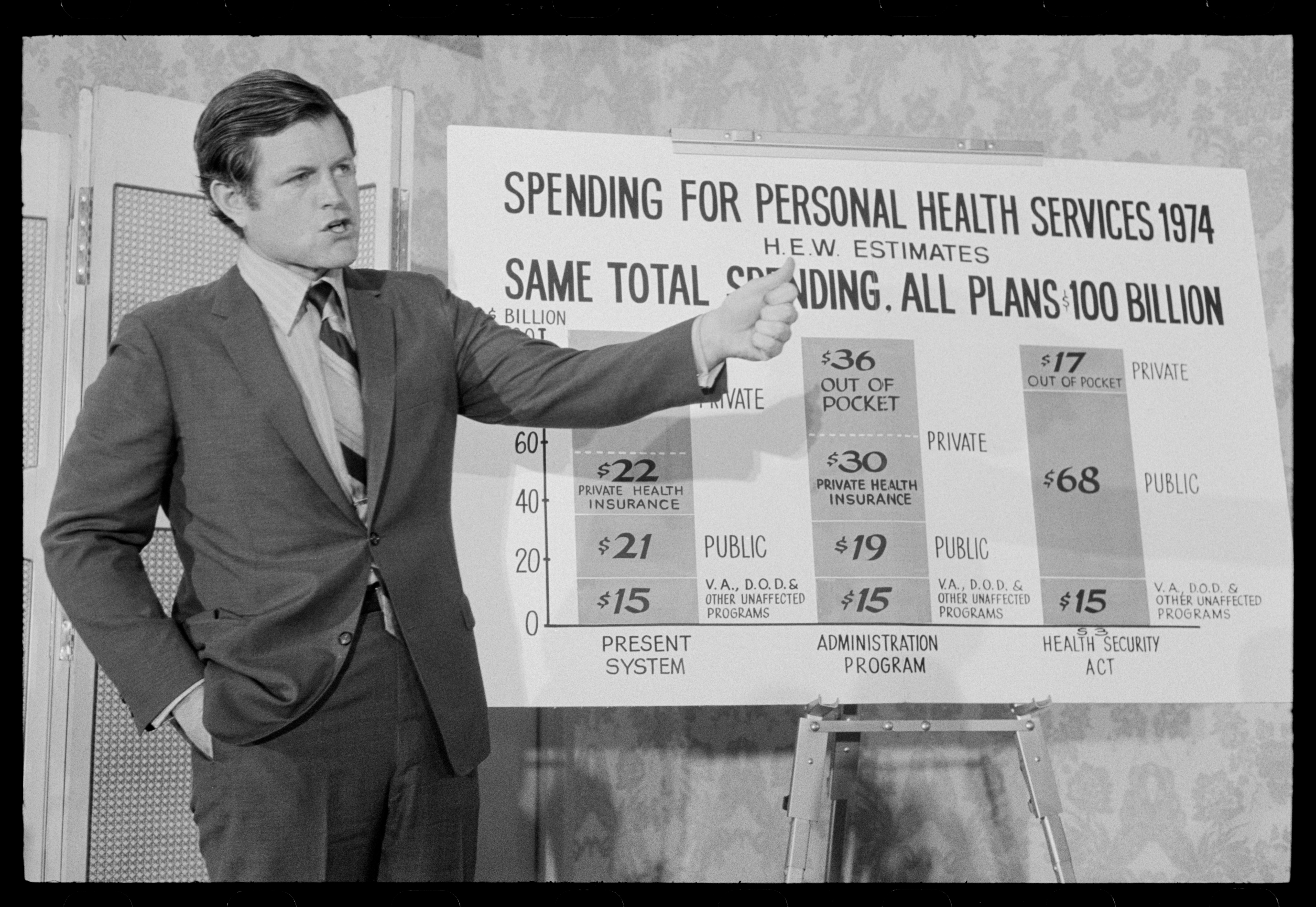

At the end of 1968, Kennedy had joined the new Committee for National Health Insurance at the invitation of its founder,

At the end of 1968, Kennedy had joined the new Committee for National Health Insurance at the invitation of its founder, United Auto Workers

The International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, better known as the United Auto Workers (UAW), is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico ...

president Walter Reuther

Walter Philip Reuther (; September 1, 1907 – May 9, 1970) was an American leader of organized labor and civil rights activist who built the United Automobile Workers (UAW) into one of the most progressive labor unions in American history. He ...

. In May 1970, Reuther died and Senator Ralph Yarborough

Ralph Webster Yarborough (June 8, 1903 – January 27, 1996) was an American politician and lawyer. He was a Texas Democratic politician who served in the United States Senate from 1957 to 1971 and was a leader of the progressive wing of his par ...

, chairman of the full Senate Labor and Public Welfare Committee and its Health subcommittee, lost his primary election, propelling Kennedy into a leadership role on the issue of national health insurance

National health insurance (NHI), sometimes called statutory health insurance (SHI), is a system of health insurance that insures a national population against the costs of health care. It may be administered by the public sector, the private secto ...

. Kennedy introduced a bipartisan bill in August 1970 for single-payer

Single-payer healthcare is a type of universal healthcare in which the costs of essential healthcare for all residents are covered by a single public system (hence "single-payer").

Single-payer systems may contract for healthcare services from ...

universal

Universal is the adjective for universe.

Universal may also refer to:

Companies

* NBCUniversal, a media and entertainment company

** Universal Animation Studios, an American Animation studio, and a subsidiary of NBCUniversal

** Universal TV, a ...

national health insurance with no cost sharing In health care, cost sharing occurs when patients pay for a portion of health care costs not covered by health insurance. The "out-of-pocket" payment varies among healthcare plans and depends on whether or not the patient chooses to use a healthcare ...

, paid for by payroll taxes and general federal revenue.

Despite the Chappaquiddick controversy of the previous year, Kennedy easily won re-election to another term in the Senate in November 1970 with 62 percent of the vote against underfunded Republican candidate Josiah Spaulding

Josiah Augustus "Si" Spaulding (December 21, 1922 – March 27, 1983) was an American businessman, attorney, and politician.

Education and military service

Spaulding graduated from the Hotchkiss School and Yale University in 1947, where he was ...

, although he received about 500,000 fewer votes than in 1964.

In January 1971, Kennedy lost his position as

In January 1971, Kennedy lost his position as Senate Majority Whip

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and members of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as the chief spokespersons for their respective political parties holding ...

to Senator Robert Byrd

Robert Carlyle Byrd (born Cornelius Calvin Sale Jr.; November 20, 1917 – June 28, 2010) was an American politician and musician who served as a United States senator from West Virginia for over 51 years, from 1959 until his death in 2010. A ...

of West Virginia, 31–24. He would later tell Byrd that the defeat was a blessing, as it allowed him to focus more on issues and committee work, where his best strengths lay and where he could exert influence independently from the Democratic party apparatus. He began a decade as chairman of the Subcommittee on Health and Scientific Research of the Senate Labor and Public Welfare Committee.

In February 1971, President Nixon proposed health insurance reform—an employer mandate to offer private health insurance if employees volunteered to pay 25 percent of premiums, federalization of Medicaid

Medicaid in the United States is a federal and state program that helps with healthcare

Health care or healthcare is the improvement of health via the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and ...

for the poor with dependent minor children, and support for health maintenance organization

In the United States, a health maintenance organization (HMO) is a medical insurance group that provides health services for a fixed annual fee. It is an organization that provides or arranges managed care for health insurance, self-funded he ...

s. Hearings on national health insurance were held in 1971, but no bill had the support of House Ways and Means and Senate Finance Committee chairmen Representative Wilbur Mills

Wilbur Daigh Mills (May 24, 1909 – May 2, 1992) was an American Democratic politician who represented in the United States House of Representatives from 1939 until his retirement in 1977. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee from ...

and Senator Russell Long

Russell Billiu Long (November 3, 1918 – May 9, 2003) was an American Democratic politician and United States Senator from Louisiana from 1948 until 1987. Because of his seniority, he advanced to chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, serving ...

. Kennedy sponsored and helped pass the limited Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973

The Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973 (Pub. L. 93-222 codified as 42 U.S.C. §300e) is a United States statute enacted on December 29, 1973. The Health Maintenance Organization Act, informally known as the federal HMO Act, is a federal l ...

. He also played a leading role, with Senator Jacob Javits

Jacob Koppel Javits ( ; May 18, 1904 – March 7, 1986) was an American lawyer and politician. During his time in politics, he represented the state of New York in both houses of the United States Congress. A member of the Republican Party, he al ...

, in the creation and passage of the National Cancer Act of 1971

The "war on cancer" is the effort to find a cure for cancer by increased research to improve the understanding of cancer biology and the development of more effective cancer treatments, such as targeted drug therapies. The aim of such efforts is t ...

.

In October 1971, Kennedy made his first speech about The Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. North ...

: he said that "Ulster is becoming Britain's Vietnam", advocating for the withdrawal of British troops from the six northern counties, called for a united Ireland

United Ireland, also referred to as Irish reunification, is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically; the sovereign Republic of Ireland has jurisdiction over the maj ...

, and declared that Ulster Unionists

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

who could not accept this "should be given a decent opportunity to go back to Britain" (a position he backed away from within a couple of years). Kennedy was sharply criticised by the British and Ulster unionists, and he formed a long political relationship with Social Democratic and Labour Party

The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) ( ga, Páirtí Sóisialta Daonlathach an Lucht Oibre) is a social-democratic and Irish nationalist political party in Northern Ireland. The SDLP currently has eight members in the Northern Ireland ...

founder John Hume

John Hume (18 January 19373 August 2020) was an Irish nationalist politician from Northern Ireland, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the recent political history of Ireland, as one of the architects of the Northern Irela ...

. In scores of anti-war speeches, Kennedy opposed President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was t ...

's policy of Vietnamization

Vietnamization was a policy of the Richard Nixon administration to end U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War through a program to "expand, equip, and train South Vietnamese forces and assign to them an ever-increasing combat role, at the same t ...

, calling it "a policy of violence hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mech ...

means more and more war". In December 1971, Kennedy strongly criticized the Nixon administration's support for Pakistan and its ignoring of "the brutal and systematic repression of East Bengal by the Pakistani army". He traveled to India and wrote a report on the plight of the 10 million Bengali refugees. In February 1972, Kennedy flew to Bangladesh and delivered a speech at the University of Dhaka

The University of Dhaka (also known as Dhaka University, or DU) is a public research university located in Dhaka, Bangladesh. It is the oldest university in Bangladesh. The university opened its doors to students on July 1st 1921. Currently i ...

, where a killing rampage had begun a year earlier.

The death of Mary Jo Kopechne in the Chappaquiddick incident had greatly hindered Kennedy's future presidential prospects, and shortly after the incident he declared that he would not be a candidate in the 1972 U.S. presidential election

The 1972 United States presidential election was the 47th quadrennial presidential election. It was held on Tuesday, November 7, 1972. Incumbent Republican President Richard Nixon defeated Democratic Senator George McGovern of South Dakota. U ...

. Nevertheless, polls in 1971 suggested he could win the nomination if he tried, and Kennedy gave some thought to running. In May of that year he decided not to, saying he needed "breathing time" to gain more experience and to take care of the children of his brothers and that in sum, "It feels wrong in my gut." Nevertheless, in November 1971, a Gallup Poll

Gallup, Inc. is an American analytics and advisory company based in Washington, D.C. Founded by George Gallup in 1935, the company became known for its public opinion polls conducted worldwide. Starting in the 1980s, Gallup transitioned its ...

still had him in first place in the Democratic nomination race with 28 percent. George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pre ...

was close to clinching the Democratic nomination in June 1972, when various anti-McGovern forces tried to get Kennedy to enter the contest at the last minute, but he declined. At the 1972 Democratic National Convention

The 1972 Democratic National Convention was the presidential nominating convention of the Democratic Party for the 1972 presidential election. It was held at Miami Beach Convention Center in Miami Beach, Florida, also the host city of the Rep ...