segregated south on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Facilities and services such as

Facilities and services such as  In the 1857

In the 1857

The legitimacy of laws requiring segregation of black people was upheld by the

The legitimacy of laws requiring segregation of black people was upheld by the

"Hollywood Loved Sammy Davis Jr. Until He Dated a White Movie Star"

'' Smithsonian'' Retrieved February 23, 2021. When former president In

In  The U.S. military was still very segregated in World War II. The Army Air Corps (forerunner of the

The U.S. military was still very segregated in World War II. The Army Air Corps (forerunner of the

BBC. Retrieved July 17, 2017 A contract for a 1965 Beatles concert at the

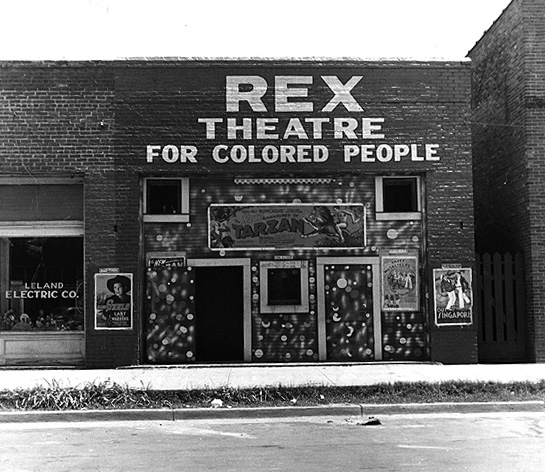

– Minnesota Public Radio Sometimes, as in Florida's Constitution of 1885, segregation was mandated by state constitutions. Racial segregation became the law in most parts of the * In theory the segregated facilities available for negroes were of the same quality as those available to whites, under the separate but equal doctrine. In practice this was rarely the case. For example, in

* In theory the segregated facilities available for negroes were of the same quality as those available to whites, under the separate but equal doctrine. In practice this was rarely the case. For example, in

The rapid influx of blacks during the Great Migration disturbed the racial balance within Northern and Western cities, exacerbating hostility between both blacks and whites in the two regions. Deed restrictions and restrictive covenants became an important instrument for enforcing racial segregation in most towns and cities, becoming widespread in the 1920s. Such covenants were employed by many real estate developers to "protect" entire subdivisions, with the primary intent to keep "

The rapid influx of blacks during the Great Migration disturbed the racial balance within Northern and Western cities, exacerbating hostility between both blacks and whites in the two regions. Deed restrictions and restrictive covenants became an important instrument for enforcing racial segregation in most towns and cities, becoming widespread in the 1920s. Such covenants were employed by many real estate developers to "protect" entire subdivisions, with the primary intent to keep " Within employment, economic opportunities for blacks were routed to the lowest-status and restrictive in potential mobility. In 1900 Reverend Matthew Anderson, speaking at the annual Hampton Negro Conference in Virginia, said that "...the lines along most of the avenues of wage earning are more rigidly drawn in the North than in the South. There seems to be an apparent effort throughout the North, especially in the cities to debar the colored worker from all the avenues of higher remunerative labor, which makes it more difficult to improve his economic condition even than in the South." In the 1930s, job discrimination ended for many African Americans in the North, after the

Within employment, economic opportunities for blacks were routed to the lowest-status and restrictive in potential mobility. In 1900 Reverend Matthew Anderson, speaking at the annual Hampton Negro Conference in Virginia, said that "...the lines along most of the avenues of wage earning are more rigidly drawn in the North than in the South. There seems to be an apparent effort throughout the North, especially in the cities to debar the colored worker from all the avenues of higher remunerative labor, which makes it more difficult to improve his economic condition even than in the South." In the 1930s, job discrimination ended for many African Americans in the North, after the

Racial segregation in

Racial segregation in

Prior to the 1930s, basketball saw a great deal of discrimination as well. Blacks and whites played mostly in different leagues and usually were forbidden from playing in inter-racial games. The popularity of the African American Harlem Globetrotters altered the American public's acceptance of African Americans in basketball. By the end of the 1930s, many northern colleges and universities allowed African Americans to play on their teams. In 1942, the color barrier for basketball was removed after Bill Jones and three other African American basketball players joined the Toledo Jim White Chevrolet NBL franchise and five Harlem Globetrotters joined the Chicago Studebakers.

In 1947, the

Prior to the 1930s, basketball saw a great deal of discrimination as well. Blacks and whites played mostly in different leagues and usually were forbidden from playing in inter-racial games. The popularity of the African American Harlem Globetrotters altered the American public's acceptance of African Americans in basketball. By the end of the 1930s, many northern colleges and universities allowed African Americans to play on their teams. In 1942, the color barrier for basketball was removed after Bill Jones and three other African American basketball players joined the Toledo Jim White Chevrolet NBL franchise and five Harlem Globetrotters joined the Chicago Studebakers.

In 1947, the

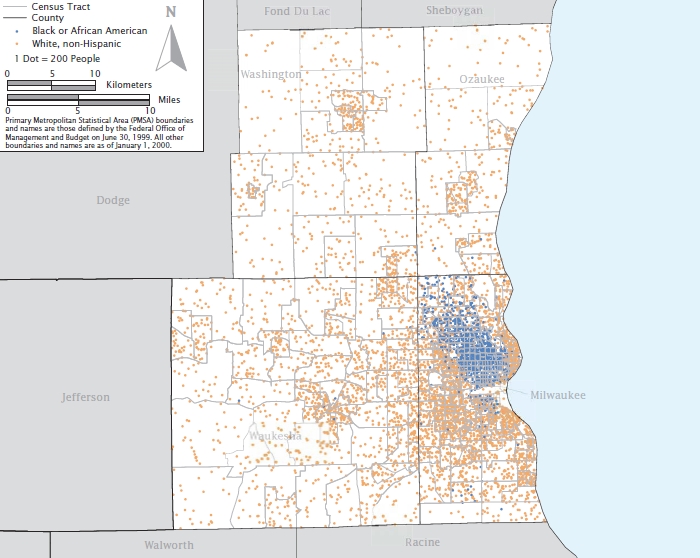

Racial segregation is most pronounced in housing. Although in the U.S. people of different races may work together, they are still very unlikely to live in integrated neighborhoods. This pattern differs only by degree in different metropolitan areas.

Residential segregation persists for a variety of reasons. Segregated neighborhoods may be reinforced by the practice of "

Racial segregation is most pronounced in housing. Although in the U.S. people of different races may work together, they are still very unlikely to live in integrated neighborhoods. This pattern differs only by degree in different metropolitan areas.

Residential segregation persists for a variety of reasons. Segregated neighborhoods may be reinforced by the practice of "

Apartheid America: Jonathan Kozol rails against a public school system that, 50 years after Brown v. Board of Education, is still deeply – and shamefully – segregated.

'' book review by Sarah Karnasiewicz for salon.com The words of "American apartheid" have been used in reference to the disparity between white and black schools in America. Those who compare this inequality to apartheid frequently point to unequal funding for predominantly black schools. In Chicago, by the academic year 2002–2003, 87 percent of public-school enrollment was black or Hispanic; less than 10 percent of children in the schools were white. In Washington, D.C., 94 percent of children were black or Hispanic; less than 5 percent were white.

School Diversity Based on Income Segregates Some

The New York Times, July 15, 2007. * Graham, Hugh. ''The Civil Rights Era: Origins and Development of National Policy, 1960–1972'' (1990) * Guyatt, Nicholas.

Bind Us Apart: How Enlightened Americans Invented Racial Segregation

'' New York: Basic Books, 2016. * Hanbury, Dallas. 2020. ''The Development of Southern Public Libraries and the African American Quest for Library Access 1898-1963.'' Lanham: Lexington Books. * Hannah-Jones, Nikole. "Worlds Apart". New York Times, New York Times Magazine, June 12, 2016, pp. 34–39 and 50–55. * Hatfield, Edward.

Segregation

" ''New Georgia Encyclopedia,'' June 1, 2007. * Hasday, Judy L. ''The Civil Rights Act of 1964: An End to Racial Segregation'' (2007). * Lands, LeeAnn

"A City Divided"

''Southern Spaces'', December 29, 2009. * Levy, Alan Howard.

Tackling Jim Crow: Racial Segregation in Professional Football

' (2003). * Massey, Douglas S., and Nancy Denton.

American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass

' (1993) * Merry, Michael S. (2012). "Segregation and Civic Virtue" Educational Theory Journal 62(4), pp. 465–486. * Myrdal, Gunnar.

An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy

' (1944). * Raffel, Jeffrey. ''Historical dictionary of school segregation and desegregation: The American experience'' (Bloomsbury, 1998

online

* Ritterhouse, Jennifer. ''Growing Up Jim Crow: The Racial Socialization of Black and White Southern Children, 1890–1940.'' (2006). * Sitkoff, Harvard. ''The Struggle for Black Equality'' (2008) * Tarasawa, Beth.

New Patterns of Segregation: Latino and African American Students in Metro Atlanta High Schools

, ''Southern Spaces'', January 19, 2009. * Woodward, C. Vann. ''The Strange Career :) of Jim Crow'' (1955). * Yellin, Eric S. ''Racism in the Nation's Service: Government Workers and the Color Line in Woodrow Wilson's America.'' Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. * *

Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity

File a housing discrimination complaint

"Remembering Jim Crow"

– Minnesota Public Radio (multi-media)

"Africans in America"

– PBS 4-Part Series

"the Rise and Fall of Jim Crow"

4-part series from PBS distributed by California Newsreel

African-American Collection from Rhode Island State Archives

*

Segregation Incorporated

, presented by Destination Freedom, written by Richard Durham in 1949 * {{DEFAULTSORT:Racial Segregation in the United States 1880s establishments in the United States 1965 disestablishments in the United States History of racial segregation in the United States, Anti-black racism in the United States African-American-related controversies Race-related controversies in the United States United States caste system, * Apartheid White supremacy in the United States

Facilities and services such as

Facilities and services such as housing

Housing refers to a property containing one or more Shelter (building), shelter as a living space. Housing spaces are inhabited either by individuals or a collective group of people. Housing is also referred to as a human need and right to ...

, healthcare

Health care, or healthcare, is the improvement or maintenance of health via the preventive healthcare, prevention, diagnosis, therapy, treatment, wikt:amelioration, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other disability, physic ...

, education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

, employment

Employment is a relationship between two party (law), parties Regulation, regulating the provision of paid Labour (human activity), labour services. Usually based on a employment contract, contract, one party, the employer, which might be a cor ...

, and transportation

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional Motion, movement of humans, animals, and cargo, goods from one location to another. Mode of transport, Modes of transport include aviation, air, land tr ...

have been systematically separated in the United States based on racial categorizations. Notably, racial segregation in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

was the legally and/or socially enforced separation of African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

from whites

White is a racial classification of people generally used for those of predominantly European ancestry. It is also a skin color specifier, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, ethnicity and point of view.

De ...

, as well as the separation of other ethnic minorities

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

from majority communities. While mainly referring to the physical separation and provision of separate facilities, it can also refer to other manifestations such as prohibitions against interracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different "Race (classification of human beings), races" or Ethnic group#Ethnicity and race, racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United Sta ...

(enforced with anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage sometimes, also criminalizing sex between members of different races.

In the United Stat ...

), and the separation of roles within an institution. The U.S. Armed Forces were formally segregated until 1948

Events January

* January 1

** The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is inaugurated.

** The current Constitutions of Constitution of Italy, Italy and of Constitution of New Jersey, New Jersey (both later subject to amendment) ...

, as black units were separated from white units but were still typically led by white officers.

In the 1857

In the 1857 Dred Scott

Dred Scott ( – September 17, 1858) was an enslaved African American man who, along with his wife, Harriet, unsuccessfully sued for the freedom of themselves and their two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, in the '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' case ...

case ('' Dred Scott v. Sandford''), the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

found that Black people were not and could never be U.S. citizens and that the U.S. Constitution and civil rights did not apply to them. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, sometimes called the Enforcement Act or the Force Act, was a United States federal law enacted during the Reconstruction era in response to civil rights violations against African Americans. The bill was passed by the ...

, but it was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1883 in the Civil Rights Cases

The ''Civil Rights Cases'', 109 U.S. 3 (1883), were a group of five landmark cases in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments did not empower Congress to outlaw racial discrimination by ...

. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of segregation in '' Plessy v. Ferguson'' (1896), so long as "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protectio ...

" facilities were provided, a requirement that was rarely met. The doctrine's applicability to public schools was unanimously overturned in ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the ...

'' (1954). In the following years, the court further ruled against racial segregation in several landmark cases including '' Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States'' (1964), which helped bring an end to the Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

.

Segregation was enforced across the U.S. for much of its history. Racial segregation follows two forms, ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

and de facto''. ''De jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'' segregation mandated the separation of races by law, and was the form imposed by U.S. states

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

in slave codes

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

Most slave codes were concerned with the rights and duties of free people in regards to ensla ...

before the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

and by Black Codes and Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

following the war, primarily in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

. ''De jure'' segregation was outlawed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

, the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights move ...

, and the Fair Housing Act

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 () is a Lists of landmark court decisions, landmark law in the United States signed into law by President of the United States, United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during the King assassination riots.

Titles ...

of 1968. '' De facto'' segregation, or segregation "in fact", is that which exists without sanction of the law. ''De facto'' segregation continues today in such closely related areas as residential segregation Residential segregation is a concept in urban sociology which refers to the voluntary or forced spatial separation of different socio-cultural, ethnic, or racial groups within residential areas. It is often associated with immigration, wealth ineq ...

and school segregation because of both contemporary behavior and the historical legacy of ''de jure'' segregation.

Antebellum era

Schools were segregated in the U.S., and educational opportunities for Black people were restricted. Efforts to establish schools for them were met with violent opposition from the public. The U.S. government established Indian boarding schools where Native Americans were sent. The African Free School was established in New York City in the 18th century.Education during the slave period in the United States

During the era of slavery in the United States, chattel slavery in the United States, the proper education of enslaved African Americans (with exception made for religious instruction) was highly discouraged, and eventually made illegal in most ...

was limited. Richard Humphreys, Samuel Powers Emlen Jr, and Prudence Crandall established schools for African Americans in the decades preceding the Civil War.

In 1832, Prudence Crandall admitted an African American girl to her all-white Canterbury Female Boarding School in Canterbury, Connecticut, resulting in public backlash and protests. She converted the boarding school to one for only African American girls, but Crandall was jailed for her efforts for violating a Black Law. In 1835, an anti-abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

mob attacked and destroyed Noyes Academy, an integrated school in Canaan, New Hampshire

Canaan is a town in Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 3,794 at the 2020 census. It is the location of Mascoma State Forest. Canaan is home to the Cardigan Mountain School, the town's largest employer.

The main ...

founded by abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

in New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. In the 1849 case '' Roberts v. City of Boston'', the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) is the highest court in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Although the claim is disputed by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, the SJC claims the distinction of being the oldest continuously fu ...

ruled that segregated schools were allowed under the Constitution of Massachusetts

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the fundamental governing document of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, one of the 50 individual states that make up the United States of America. It consists of a preamble, declaration ...

. Emlen Institution was a boarding school for African American and Native American orphans in Ohio and then Pennsylvania. Richard Humphreys bequeathed money to establish the Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia. Yale Law School co-founder, judge, and mayor of New Haven David Daggett was a leader in the fight against schools for African Americans and helped block plans for a college for African Americans in New Haven, Connecticut.

Civil rights after the Civil War

Black schools were established by some religious groups and philanthropists to educate African Americans. Oberlin Academy was one of the early schools to integrate. Lowell High School also accepted African American students. California passed a law prohibiting "Negroes, Mongolians and Indians" from attending public schools. It took ten or more minorities in a community to petition for a segregated school or these groups were denied access to public education. The state's superintendent of schools, Andrew Moulder, stated: "The great mass of our citizens will not associate in terms of equality with these inferior races, nor will they consent that their children do so." In Coloradohousing

Housing refers to a property containing one or more Shelter (building), shelter as a living space. Housing spaces are inhabited either by individuals or a collective group of people. Housing is also referred to as a human need and right to ...

and school segregation lasted into the 1960s.

In 1867, Portland, Oregon prevented a Black student from attending its public elementary schools and instead established a separate segregated school when it was sued. Portland's public schools were integrated in 1872.

Reconstruction

Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867,ratified

Ratification is a principal's legal confirmation of an act of its agent. In international law, ratification is the process by which a state declares its consent to be bound to a treaty. In the case of bilateral treaties, ratification is usuall ...

the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment (Amendment XV) to the United States Constitution prohibits the federal government and each state from denying or abridging a citizen's right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." It wa ...

in 1870, granting African Americans the right to vote, and it also enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1875

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, sometimes called the Enforcement Act or the Force Act, was a United States federal law enacted during the Reconstruction era in response to civil rights violations against African Americans. The bill was passed by the ...

forbidding racial segregation in accommodations. Federal occupation in the South helped allow many black people to vote and elect their own political leaders. The Reconstruction amendments

The , or the , are the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the United States Constitution, adopted between 1865 and 1870. The amendments were a part of the implementation of the Reconstruction of the American South which oc ...

asserted the supremacy of the national state and they also asserted that everyone within it was formally equal under the law. However, it did not prohibit segregation in schools.

When the Republicans came to power in the Southern states after 1867, they created the first system of taxpayer-funded public schools. Southern black people wanted public schools for their children, but they did not demand racially integrated schools. Almost all the new public schools were segregated, apart from a few in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

. After the Republicans lost power in the mid-1870s, Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States.

Before the American Civil War, Southern Democrats mostly believed in Jacksonian democracy. In the 19th century, they defended slavery in the ...

retained the public school systems but sharply cut their funding.

Almost all private academies and colleges in the South were strictly segregated by race. The American Missionary Association

The American Missionary Association (AMA) was a Protestant-based abolitionist group founded on in Albany, New York. The main purpose of the organization was abolition of slavery, education of African Americans, promotion of racial equality, and ...

supported the development and establishment of several historically black colleges including Fisk University

Fisk University is a Private university, private Historically black colleges and universities, historically black Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Nashville, Tennessee. It was founded in 1866 and its campus i ...

and Shaw University

Shaw University is a private historically black university in Raleigh, North Carolina. Founded on December 1, 1865, Shaw University is the oldest HBCU to begin offering courses in the Southern United States. The school had its origin in the fo ...

. In this period, a handful of northern colleges accepted black students. Northern denominations and especially their missionary associations established private schools across the South to provide secondary education. They provided a small amount of collegiate work. Tuition was minimal, so churches financially supported the colleges and also subsidized the pay of some teachers. In 1900, churches—mostly based in the North—operated 247 schools for black people across the South, with a budget of about $1 million. They employed 1600 teachers and taught 46,000 students. Prominent schools included Howard University

Howard University is a private, historically black, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and accredited by the Mid ...

, a private, federally chartered institution based in Washington, D.C.; Fisk University

Fisk University is a Private university, private Historically black colleges and universities, historically black Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Nashville, Tennessee. It was founded in 1866 and its campus i ...

in Nashville, Atlanta University, Hampton Institute in Virginia, and others.

By the early 1870s, the North lost interest in further reconstruction efforts, and, when federal troops were withdrawn in 1877, the Republican Party in the South splintered and lost support, leading to the conservatives (calling themselves "Redeemers

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction era of the United States, Reconstruction Era that followed the American Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party (Unite ...

") taking control of all the Southern states. 'Jim Crow' segregation began somewhat later, in the 1880s. Disfranchisement

Disfranchisement, also disenfranchisement (which has become more common since 1982) or voter disqualification, is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing someo ...

of black people began in the 1890s. Although the Republican Party had championed African-American rights during the Civil War and had become a platform for black political influence during Reconstruction, a backlash among white Republicans led to the rise of the lily-white movement

The Lily-White Movement was an anti-black political movement within the Republican Party in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a response to the political and socioeconomic gains made by African-Americans follo ...

to remove African Americans from leadership positions in the party and to incite riots to divide the party, with the ultimate goal of eliminating black influence. By 1910, segregation was firmly established across the South and most of the border region, and only a small number of black leaders were allowed to vote across the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

.

Jim Crow era

The legitimacy of laws requiring segregation of black people was upheld by the

The legitimacy of laws requiring segregation of black people was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

in the 1896 case of '' Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537. The Supreme Court sustained the constitutionality of a Louisiana statute that required railroad companies to provide "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protectio ...

" accommodations for white and black passengers and prohibited white people and black people from using railroad cars that were not assigned to their race.

''Plessy'' thus allowed segregation, which became standard throughout the southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

, and represented the institutionalization

In sociology, institutionalisation (or institutionalization) is the process of embedding some conception (for example a belief, norm, social role, particular value or mode of behavior) within an organization, social system, or society as a w ...

of the Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

period. Everyone was supposed to receive the same public services (schools, hospitals, prisons, etc.), but with separate facilities for each race. In practice, the services and facilities reserved for African Americans were almost always of lower quality than those reserved for white people, if they existed at all; for example, most African American schools received less public funding per student than nearby white schools. Segregation was not mandated by law in the Northern states, but a ''de facto'' system grew for schools, in which nearly all black students attended schools that were nearly all-black. In the South, white schools had only white pupils and teachers, while black schools had only black teachers and black students.

President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, a Southern Democrat, allowed individual government department heads impose segregation of federal workplaces in 1913.

Some streetcar

A tram (also known as a streetcar or trolley in Canada and the United States) is an urban rail transit in which vehicles, whether individual railcars or multiple-unit trains, run on tramway tracks on urban public streets; some include s ...

companies did not segregate voluntarily. It took 15 years for the government to break down their resistance.

On at least six occasions over nearly 60 years, the Supreme Court held, either explicitly or by necessary implication, that the "separate but equal" rule announced in Plessy was the correct rule of law, although, toward the end of that period, the Court began to focus on whether the separate facilities were in fact equal. The repeal of "separate but equal" laws was a major focus of the civil rights movement. In ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the ...

'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), the Supreme Court outlawed segregated public education facilities for black people and white people at the state level. The Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

superseded all state and local laws requiring segregation. Compliance with the new law came slowly, and it took years with many cases in lower courts to enforce it.

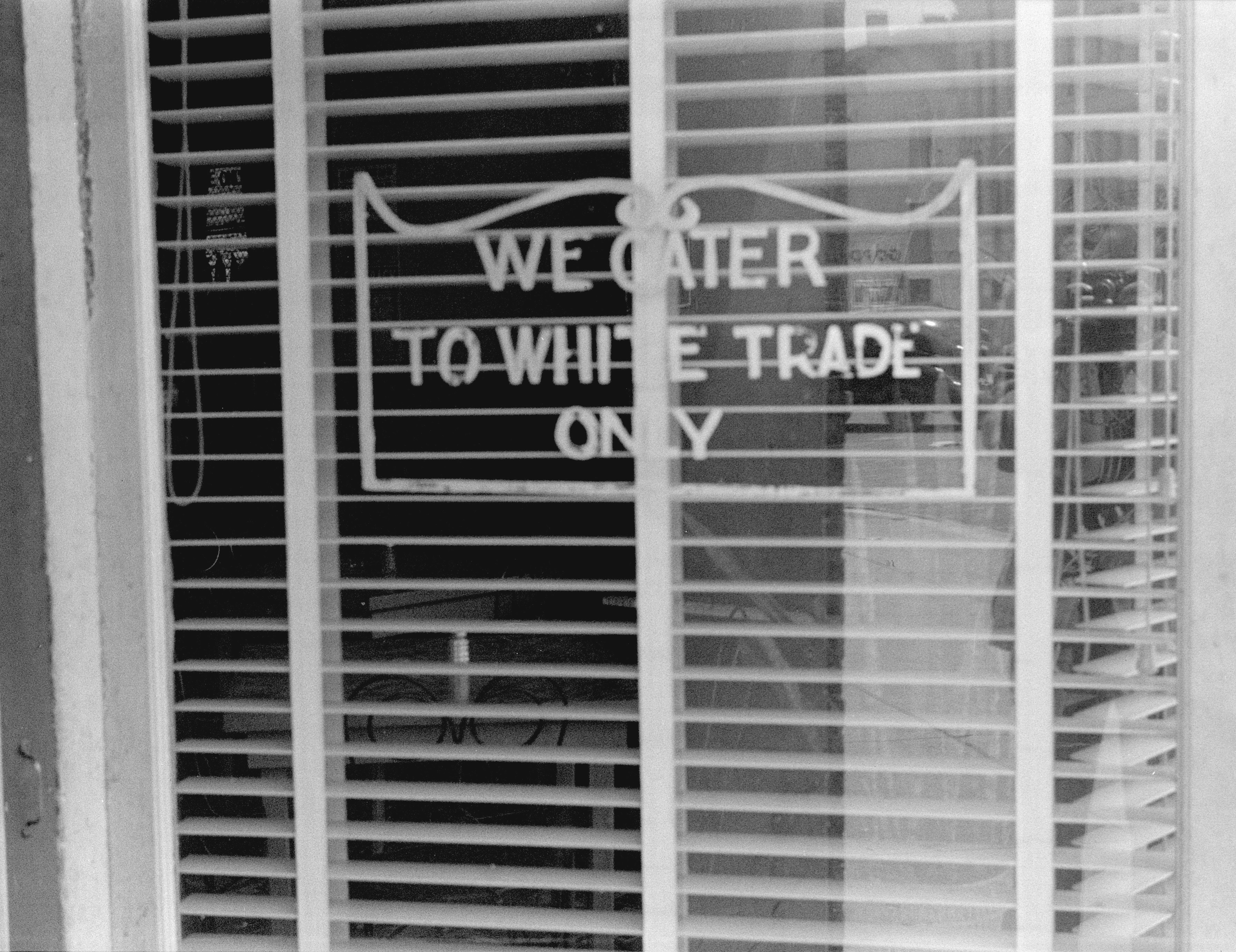

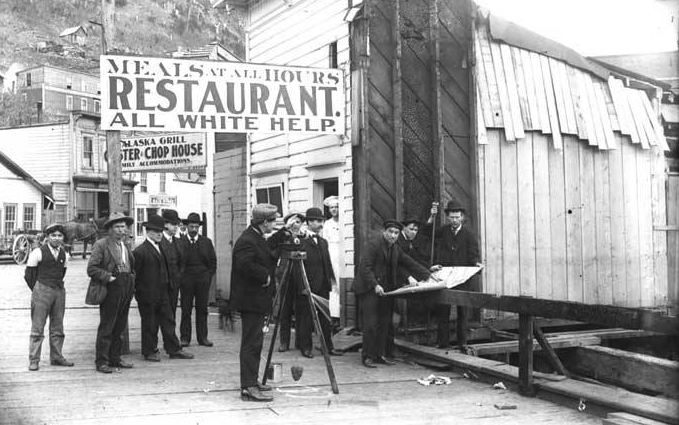

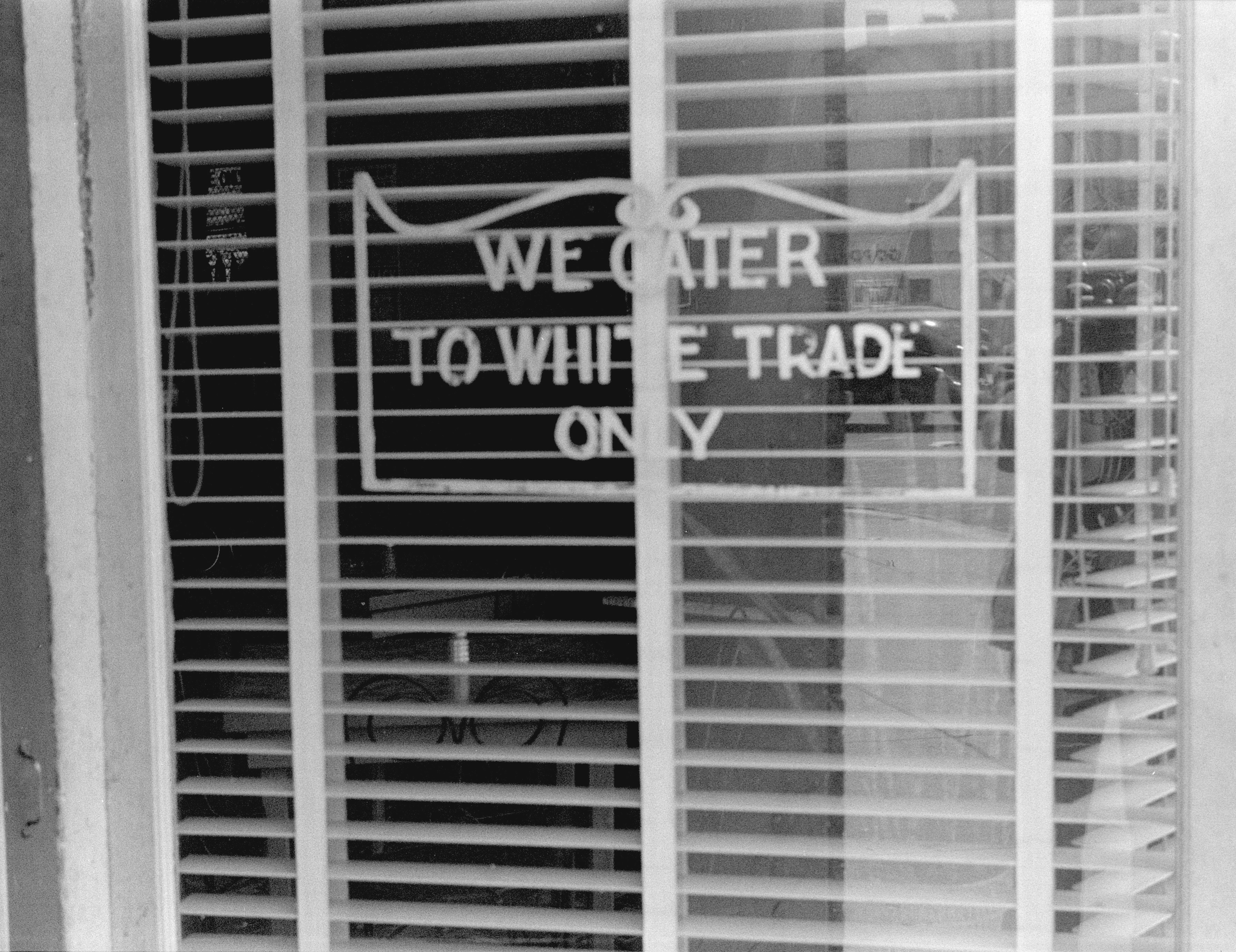

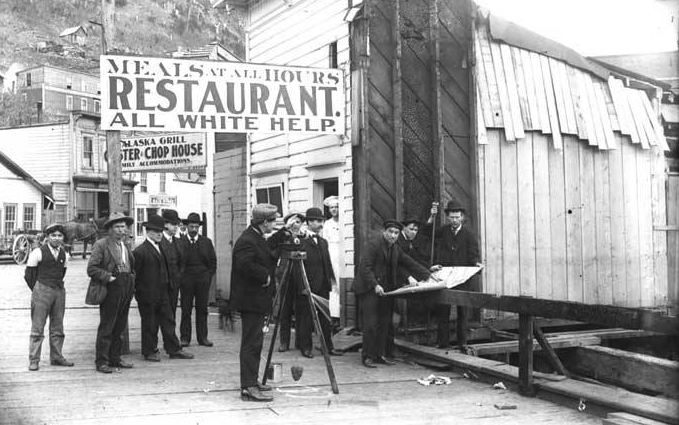

In parts of the United States, especially in the South, signs were used to indicate where African Americans could legally walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat.

New Deal era

With the passing ofNational Housing Act of 1934

The National Act of 1934, , , also called the Better Housing Program, was part of the New Deal passed during the Great Depression in order to make housing and home mortgages more affordable. It created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA ...

, the United States government began to make low-interest mortgages available to families through the Federal Housing Administration

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), also known as the Office of Housing within the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), is a Independent agencies of the United States government, United States government agency founded by Pr ...

(FHA).

Black families were explicitly denied these loans. While technically legally allowed these loans, in practice they were barred. This was because eligibility for federally backed loans was largely determined by redlining

Redlining is a Discrimination, discriminatory practice in which financial services are withheld from neighborhoods that have significant numbers of Race (human categorization), racial and Ethnic group, ethnic minorities. Redlining has been mos ...

maps created by the Home Owners' Loan Corporation

The Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) was a government-sponsored corporation created as part of the New Deal. The corporation was established in 1933 by the Home Owners' Loan Corporation Act under the leadership of President Franklin D. Roo ...

(HOLC).

Any neighborhood with "inharmonious racial groups" would either be marked red or yellow, depending on the proportion of Black residents. This was explicitly stated within the FHA underwriting manual that the HOLC used as for its maps.

For neighborhood building projects, a similar requirement existed. The federal government required them to be explicitly segregated to be federally backed. The federal government's financial backing also required the use of racially restrictive covenants, that banned white homeowners from reselling their house to any Black buyers, effectively locking Black Americans out of the housing market.

The government encouraged white families to move into suburbs by granting them loans, which were refused to Black Americans. Many established African American communities were disrupted by the routing of interstate highways

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, or the Eisenhower Interstate System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National H ...

through their neighborhoods. In order to build these elevated highways, the government destroyed tens of thousands of single-family homes. Because these properties were summarily declared to be "in decline", families were given pittances for their properties, and forced to move into federally-funded housing which was called " the projects". To build these projects, still more single-family homes were demolished.

The New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

of the 1930s as a whole was racially segregated; Black people rarely worked alongside whites in New Deal programs. The largest relief program by far was the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to car ...

(WPA); it operated segregated units, as did its youth affiliate, the National Youth Administration

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a New Deal agency sponsored by Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt during his presidency. It focused on providing work and education for Americans between the ages of 16 and 25. ...

(NYA). Black people were hired by the WPA as supervisors in the North; of 10,000 WPA supervisors in the South, only 11 were Black. Historian Anthony Badger argues "New Deal programs in the South routinely discriminated against black people and perpetuated segregation." In its first few weeks of operation, Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was ...

(CCC) camps in the North were integrated. By July 1935, practically all the CCC camps in the United States were segregated, and Black workers were strictly limited in their assigned supervisory roles. Philip Klinkner and Rogers Smith

Rogers M. Smith (born September 20, 1953) is an American political scientist and author noted for his research and writing on American constitutional and political development and political thought, with a focus on issues of citizenship and r ...

argue "even the most prominent racial liberals in the New Deal did not dare to criticize Jim Crow." Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes was one of the Roosevelt Administration's most prominent supporters of Black people and former president of the Chicago chapter of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

. In 1937, when Senator Josiah Bailey, a Democrat from North Carolina, accused him of trying to break down segregation laws, Ickes wrote him a rebuttal, saying:

:I think it is up to the states to work out their social problems if possible, and while I have always been interested in seeing that the Negro has a square deal, I have never dissipated my strength against the particular stone wall of segregation. I believe that wall will crumble when the Negro has brought himself to a high educational and economic status.... Moreover, while there are no segregation laws in the North, there is segregation in fact and we might as well recognize this.

The New Deal also provided federal benefits to Black Americans. This led many to become part of the New Deal coalition

The New Deal coalition was an American political coalition that supported the Democratic Party beginning in 1932. The coalition is named after President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, and the follow-up Democratic presidents. It was ...

from their base in Northern and Western cities where they could now vote, having in large numbers left the South during the Great Migration. Influenced in part by the " Black Cabinet" advisors and the March on Washington Movement, just prior to America's entry into World War II, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802

Executive Order 8802 was an Executive order (United States), executive order signed by President of the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 25, 1941. It prohibited ethnic or racial discrimination in the nation's defense indust ...

, the first anti-discrimination order at the federal level and established the Fair Employment Practices Committee. Roosevelt's successor, President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

appointed the President's Committee on Civil Rights

The President's Committee on Civil Rights was a United States Presidential Commission (United States), presidential commission established by President of the United States, President Harry Truman in 1946. The committee was created by Executive ...

, and issued Executive Order 9980 and Executive Order 9981 providing for desegregation throughout the federal government and the armed forces.

Hypersegregation

In an often-cited 1988 study,Douglas Massey

Douglas Steven Massey (born October 5, 1952) is an American sociologist. Massey is currently a professor of sociology at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University and is an adjunct professor of sociology ...

and Nancy Denton compiled 20 existing segregation measures and reduced them to five dimensions of residential segregation. Dudley L. Poston and Michael Micklin argue that Massey and Denton "brought conceptual clarity to the theory of segregation measurement by identifying five dimensions".

African Americans are considered to be racially segregated because of all five dimensions of segregation being applied to them within these inner cities across the U.S. These five dimensions are evenness, clustering, exposure, centralization and concentration.

''Evenness'' is the difference between the percentage of a minority group in a particular part of a city, compared to the city as a whole. ''Exposure'' is the likelihood that a minority and a majority party will come in contact with one another. ''Clustering'' is the gathering of different minority groups into a single space; clustering often leads to one big ghetto

A ghetto is a part of a city in which members of a minority group are concentrated, especially as a result of political, social, legal, religious, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished than other ...

and the formation of "hyperghettoization". ''Centralization'' measures the tendency of members of a minority group to be located in the middle of an urban area, often computed as a percentage of a minority group living in the middle of a city (as opposed to the outlying areas). ''Concentration'' is the dimension that relates to the actual amount of land a minority lives on within its particular city. The higher segregation is within that particular area, the smaller the amount of land a minority group will control.

In the 1980s, the rise of hypersegregation was distinctively large in Black neighborhoods. The extreme segregation of African Americans resulted in a different society lived by black and white residents. The isolation of the African American community was evident in living conditions, grocery markets, job applications, etc. As segregation shaped different lifestyles in those who live in the suburbs compare to areas with public housing, the ''Concentration'' dimension of segregation played a significant role. ''Concentration'' increased poverty in black neighborhoods by providing more expensive and less ideal living situations to African Americans. This rise of poverty created a disadvantage when it came to the job market, which led to a decrease in marriage rates in the black community due to the large number of men that weren't financially secure enough to take care of a family. Hypersegregation was prominent in creating an isolated community for African Americans in the United States. This pattern was consistent in making African American residents unstable financially which spread to other poor living conditions.

The pattern of hypersegregation began in the early 20th century. African Americans who moved to large cities often moved into the inner city in order to gain industrial jobs. The influx of new African American residents caused many white residents to move to the new suburbs (federally subsidized for white families only) in a case of white flight

The white flight, also known as white exodus, is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the Racism ...

. This was encouraged by the government, as many were white middle-class families who lived in segregated public housing first established in the 1930s. The US government heavily advertised the suburbs to them and the subsidized mortgages the government provided were typically cheaper than monthly rent. These same mortgages were not provided to Black Americans in public housing

Public housing, also known as social housing, refers to Subsidized housing, subsidized or affordable housing provided in buildings that are usually owned and managed by local government, central government, nonprofit organizations or a ...

, leading to overcrowding, while white public housing sat vacant.

As industry began to move out of the inner city, the African American residents lost the stable jobs that had brought them to the area. Many were unable to leave the inner city and became increasingly poor. This created the inner-city ghettos that make up the core of hypersegregation. Though the Civil Rights Act of 1968

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 () is a Lists of landmark court decisions, landmark law in the United States signed into law by President of the United States, United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during the King assassination riots.

Titles ...

banned discrimination in housing, housing patterns established earlier saw the perpetuation of hypersegregation. Data from the 2000 census shows that 29 metropolitan areas displayed black and white hypersegregation. Two areas—Los Angeles and New York City—displayed Hispanic-white hypersegregation. No metropolitan area

A metropolitan area or metro is a region consisting of a densely populated urban area, urban agglomeration and its surrounding territories which share Industry (economics), industries, commercial areas, Transport infrastructure, transport network ...

displayed hypersegregation for Asians or for Native Americans.

Racism

PresidentWoodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

removed many Blacks from public office. He did not oppose segregation practices by autonomous department heads of the federal civil service, according to Brian J. Cook in his work, ''Democracy And Administration: Woodrow Wilson's Ideas And The Challenges Of Public Management''. White and Black people

Black is a racial classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid- to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin and often additional phenotypical ...

were required to eat separately, attend separate schools, use separate public toilets, park benches, train, buses, and even use different water fountains. Stores and restaurants often refused to serve different races under the same roof.

Public segregation was challenged by individual citizens on rare occasions but had minimal impact on civil rights issues, until December 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an American civil rights activist. She is best known for her refusal to move from her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus, in defiance of Jim Crow laws, which sparke ...

refused to be moved to the back of a bus for a white passenger, sparking the Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social boycott, protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United ...

. Parks's act of defiance became an important symbol of the modern Civil Rights Movement and she became an international icon of resistance to racial segregation.

Segregation was also pervasive in housing. State constitutions (for example, that of California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

) had clauses giving local jurisdictions the right to regulate where members of certain races could live. In 1917, the Supreme Court in the case of '' Buchanan v. Warley'' ruled municipal resident segregation ordinances were unconstitutional. In response, whites resorted to the restrictive covenant

A covenant, in its most general and covenant (historical), historical sense, is a solemn promise to engage in or refrain from a specified action. Under historical English common law, a covenant was distinguished from an ordinary contract by the ...

, a formal deed restriction binding white property owners in a given neighborhood not to sell to Blacks. Whites who broke these agreements could be sued by "damaged" neighbors. In the 1948 case of '' Shelley v. Kraemer'', the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

ruled these covenants legally unenforceable. Residential segregation patterns had already become established in most American cities and have often persisted up to the present from the impact of white flight

The white flight, also known as white exodus, is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the Racism ...

and redlining

Redlining is a Discrimination, discriminatory practice in which financial services are withheld from neighborhoods that have significant numbers of Race (human categorization), racial and Ethnic group, ethnic minorities. Redlining has been mos ...

.

In most cities, the only way Blacks could relieve the pressure of crowding that resulted from increasing migration was to expand residential borders into surrounding previously white neighborhoods, a process that often resulted in harassment and attacks by white residents whose intolerant attitudes were intensified by fears that Black neighbors would cause property values to decline. Moreover, the increased presence of African Americans in cities, North and South, as well as their competition with whites for housing, jobs, and political influence sparked a series of race riots. In 1898 white citizens of Wilmington, North Carolina

Wilmington is a port city in New Hanover County, North Carolina, United States. With a population of 115,451 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, eighth-most populous city in the st ...

, resenting African Americans' involvement in local government and incensed by an editorial in an African American newspaper accusing white women of loose sexual behavior, rioted and killed dozens of Blacks. In the fury's wake, white supremacists overthrew the city government, expelling black and white officeholders, and instituted restrictions to prevent Blacks from voting. In Atlanta in 1906, newspaper accounts alleging attacks by black men on white women provoked an outburst of shooting and killing that left twelve Blacks dead and seventy injured. An influx of unskilled black strikebreakers into East St Louis, Illinois, heightened racial tensions in 1917. Rumors that Blacks were arming themselves for an attack on whites resulted in numerous attacks by white mobs on black neighborhoods. On July 1, Blacks fired back at a car whose occupants they believed had shot into their homes and mistakenly killed two policemen riding in a car. The next day, a full-scaled riot erupted which ended only after nine whites and thirty-nine blacks had been killed and over three hundred buildings were destroyed.

Anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage sometimes, also criminalizing sex between members of different races.

In the United Stat ...

(also known as miscegenation laws) prohibited whites and non-whites from marrying each other. The first ever anti-miscegenation law was passed by the Maryland General Assembly

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives, and the lower ...

in 1691, criminalizing interracial marriage. During one of his famous debates with Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a United States Senate, U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party (United States) ...

in Charleston, Illinois

Charleston is a city in and the county seat of Coles County, Illinois, United States. The population was 17,286, as of the 2020 census. The city is home to Eastern Illinois University and has close ties with its neighbor, Mattoon, Illinois, Ma ...

in 1858, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

stated,

By the late 1800s, 38 US states had anti-miscegenation statutes. By 1924, the ban on interracial marriage was still enforced in 29 states. While interracial marriage had been legal in California since 1948, in 1957 actor Sammy Davis Jr. faced a backlash for his involvement with white actress Kim Novak

Marilyn Pauline "Kim" Novak (born February 13, 1933) is an American retired actress and painter. Her contributions to cinema have been honored with two Golden Globe Awards, an Honorary Golden Bear, a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, and a s ...

. Harry Cohn

Harry Cohn (July 23, 1891 – February 27, 1958) was a co-founder, president, and production director of Columbia Pictures, Columbia Pictures Corporation.

Life and career

Cohn was born to a working-class Jewish family in New York City. His fath ...

, the president of Columbia Pictures (with whom Novak was under contract) gave in to his concerns that a racist backlash against the relationship could hurt the studio. Davis briefly married black dancer Loray White in 1958 to protect himself from mob violence. Inebriated at the wedding ceremony, Davis despairingly said to his best friend, Arthur Silber Jr., "Why won't they let me live my life?" The couple never lived together and commenced divorce proceedings in September 1958.Lanzendorfer, Joy (August 9, 2017"Hollywood Loved Sammy Davis Jr. Until He Dated a White Movie Star"

'' Smithsonian'' Retrieved February 23, 2021. When former president

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

was asked by a reporter in 1963 if interracial marriage would become widespread in the U.S., he responded, "I hope not; I don't believe in it", before asking a question often aimed at anyone advocating racial integration, "Would you want your daughter to marry a Negro? She won't love someone who isn't her color."

In 1958, officers in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

entered the home of Richard and Mildred Loving and dragged them out of bed for living together as an interracial couple, on the basis that "any white person intermarry with a colored person"— or vice versa—each party "shall be guilty of a felony" and face prison terms of five years. In 1965, Virginia trial court Judge Leon Bazile, who heard their original case, defended his decision:

In

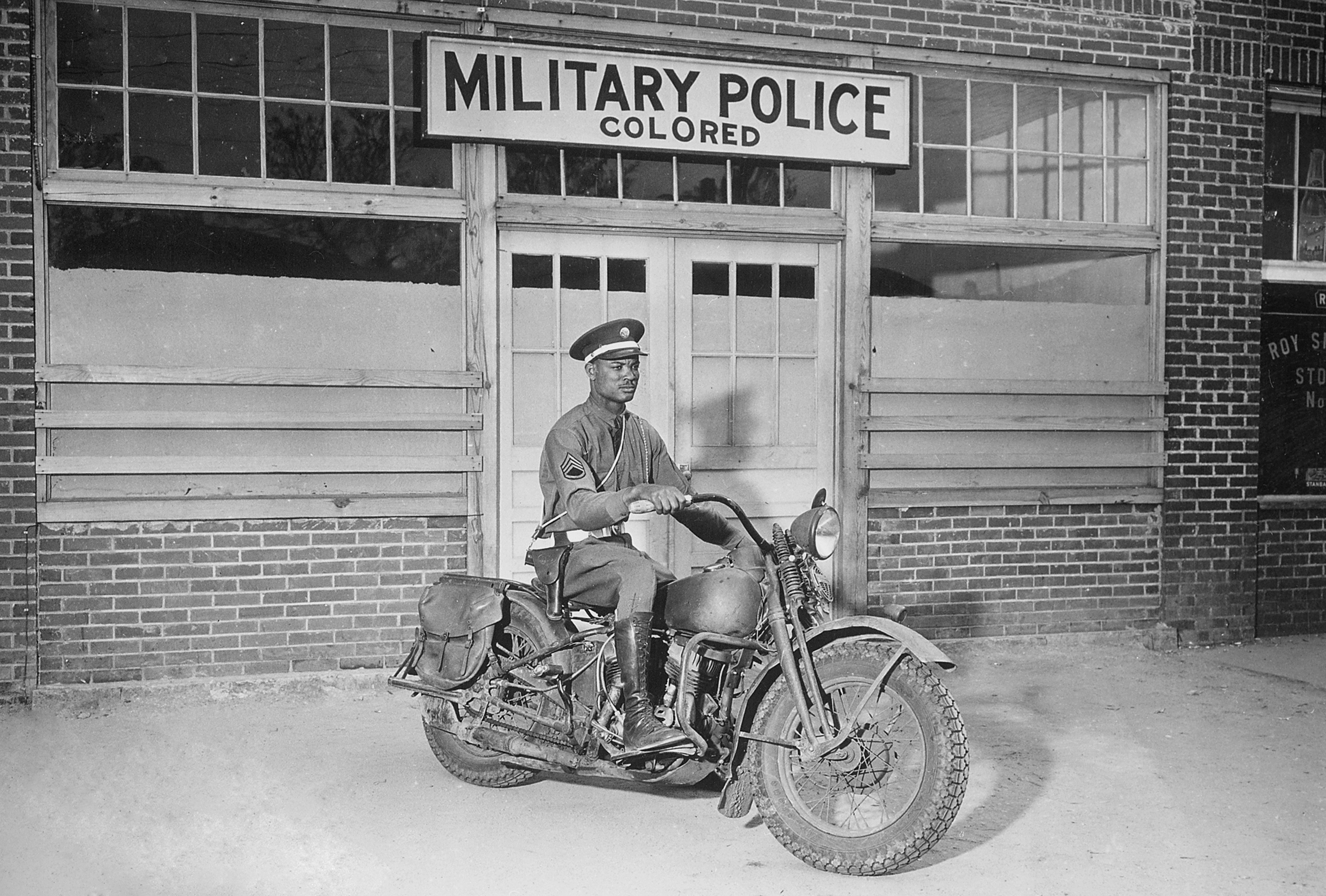

In World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, blacks served in the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

in segregated units. The 369th Infantry (formerly 15th New York National Guard) Regiment distinguished themselves and were known as the " Harlem Hellfighters".

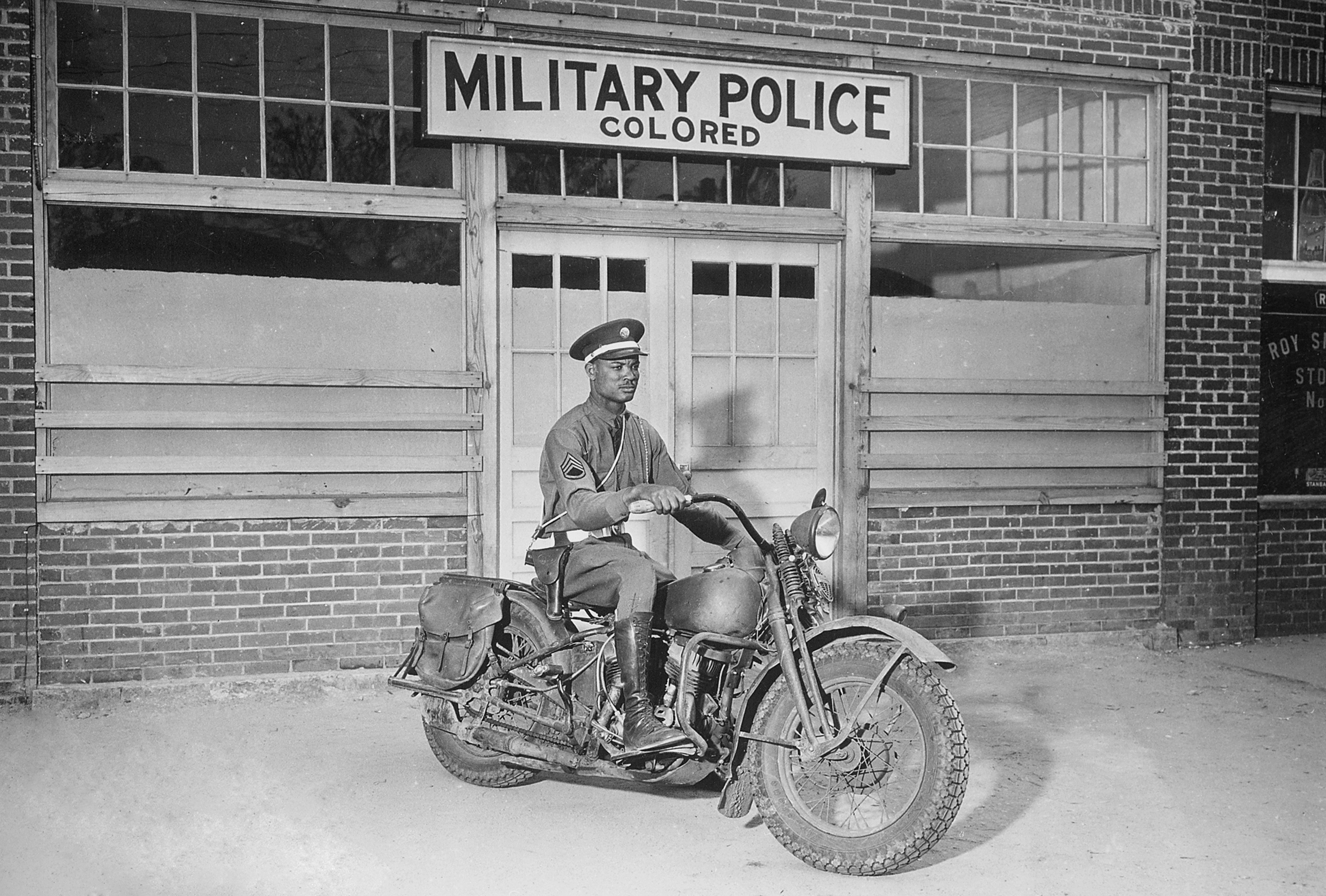

The U.S. military was still very segregated in World War II. The Army Air Corps (forerunner of the

The U.S. military was still very segregated in World War II. The Army Air Corps (forerunner of the Air Force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

) and the Marines

Marines (or naval infantry) are military personnel generally trained to operate on both land and sea, with a particular focus on amphibious warfare. Historically, the main tasks undertaken by marines have included Raid (military), raiding ashor ...

had no blacks enlisted in their ranks. There were blacks in the Navy Seabees

United States Naval Construction Battalions, better known as the Navy Seabees, form the U.S. Naval Construction Forces (NCF). The Seabee nickname is a heterograph of the initial letters "CB" from the words "Construction Battalion". Dependi ...

. Before the war, the army had only five African American officers. No African American received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

during the war, and they were mostly relegated to non-combat units. Black soldiers were sometimes forced to give up their seats in trains to Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

prisoners of war. World War II saw the first black military pilots in the U.S., the Tuskegee Airmen

The Tuskegee Airmen were a group of primarily African American military pilots (fighter and bomber) and airmen who fought in World War II. They formed the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Fighter Group, 477th Bombardment Group (Medium) of th ...

, 99th Fighter Squadron, and also saw the segregated 183rd Engineer Combat Battalion participate in the liberation of Jewish survivors at Buchenwald concentration camp

Buchenwald (; 'beech forest') was a German Nazi concentration camp established on Ettersberg hill near Weimar, Nazi Germany, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within the Altreich (pre-1938 ...

. Despite the institutional policy of racially segregated training for enlisted members and in tactical units; Army policy dictated that black and white soldiers train together in officer candidate school

An officer candidate school (OCS) is a military school which trains civilians and Enlisted rank, enlisted personnel in order for them to gain a Commission (document), commission as Commissioned officer, officers in the armed forces of a country. H ...

s (beginning in 1942). Thus, the Officer Candidate School

An officer candidate school (OCS) is a military school which trains civilians and Enlisted rank, enlisted personnel in order for them to gain a Commission (document), commission as Commissioned officer, officers in the armed forces of a country. H ...

became the Army's first formal experiment with integration – with all Officer Candidates, regardless of race, living and training together.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, 110,000 people of Japanese descent (whether citizens or not) were placed in internment camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without Criminal charge, charges or Indictment, intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects ...

s. Hundreds of people of German and Italian descent were also imprisoned (see German American internment and Italian American internment). While the government program of Japanese American internment

During World War II, the United States forcibly relocated and incarcerated about 120,000 people of Japanese descent in ten concentration camps operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), mostly in the western interior of the country. Abou ...

targeted all the Japanese in America as enemies, most German and Italian Americans were left in peace and were allowed to serve in the U.S. military.

Pressure to end racial segregation in the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

grew among African Americans and progressives after the end of World War II. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

signed Executive Order 9981, ending segregation in the United States Armed Forces.

A club central to the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics, and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the ti ...

in the 1920s, the Cotton Club in Harlem, New York City, was a whites-only establishment, with blacks (such as Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American Jazz piano, jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous Big band, jazz orchestra from 1924 through the rest of his life.

Born and raised in Washington, D ...

) allowed to perform, but to a white audience. The first black Oscar

Oscar, OSCAR, or The Oscar may refer to:

People and fictional and mythical characters

* Oscar (given name), including lists of people and fictional characters named Oscar, Óscar or Oskar

* Oscar (footballer, born 1954), Brazilian footballer ...

recipient Hattie McDaniel was not permitted to attend the premiere of ''Gone with the Wind Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* Gone with the Wind (novel), ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* Gone with the Wind (film), ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Wind ...

'' with Atlanta being racially segregated, and at the 12th Academy Awards ceremony at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

she was required to sit at a segregated table at the far wall of the room; the hotel had a no-blacks policy, but allowed McDaniel in as a favor. McDaniel's final wish to be buried in Hollywood Cemetery was denied because the graveyard was restricted to whites only.

On September 11, 1964, John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer-songwriter, musician and activist. He gained global fame as the founder, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of the Beatles. Lennon's ...

announced The Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band formed in Liverpool in 1960. The core lineup of the band comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are widely regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatle ...

would not play to a segregated audience in Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville ( ) is the most populous city proper in the U.S. state of Florida, located on the Atlantic coast of North Florida, northeastern Florida. It is the county seat of Duval County, Florida, Duval County, with which the City of Jacksonv ...

. City officials relented following this announcement."The Beatles banned segregated audiences, contract shows"BBC. Retrieved July 17, 2017 A contract for a 1965 Beatles concert at the

Cow Palace

The Cow Palace (originally the California State Livestock Pavilion) is an indoor arena and events center located in Daly City, California, situated on the city's northern border with neighboring San Francisco. Because the border passes through t ...

in Daly City, California

Daly City () is the second-most populous city in San Mateo County, California, United States. Located in the San Francisco Bay Area, and immediately south of San Francisco (sharing its northern border with almost all of San Francisco's southern ...

, specifies that the band "not be required to perform in front of a segregated audience".

Despite all the legal changes that have taken place since the 1940s and especially in the 1960s (see Desegregation), the United States remains, to some degree, a segregated society, with housing patterns, school enrollment, church membership, employment opportunities, and even college admissions all reflecting significant ''de facto'' segregation. Supporters of affirmative action

Affirmative action (also sometimes called reservations, alternative access, positive discrimination or positive action in various countries' laws and policies) refers to a set of policies and practices within a government or organization seeking ...

argue that the persistence of such disparities reflects either racial discrimination or the persistence of its effects.

'' Gates v. Collier'' was a case decided in federal court that brought an end to the trusty system and flagrant inmate abuse at the notorious Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, Mississippi. In 1972 federal judge

Federal judges are judges appointed by a federal level of government as opposed to the state/provincial/local level. United States

A U.S. federal judge is appointed by the U.S. president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate in accordance with Arti ...

, William C. Keady found that Parchman Farm violated modern standards of decency. He ordered an immediate end to all unconstitutional conditions and practices. Racial segregation of inmates was abolished. And the trusty system, which allowed certain inmates to have power and control over others, was also abolished.

More recently, the disparity between the racial compositions of inmates in the American prison system has led to concerns that the U.S. Justice system furthers a "new apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

".

Scientific racism

The intellectual roots of '' Plessy v. Ferguson'', the landmark United States Supreme Court decision which upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation, under the doctrine of "separate but equal", were partially tied to thescientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

of the era. The popular support of the decision was likely a result of the racist beliefs which were held by most whites at the time. Later, the court decision ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the ...

'' rejected the ideas of scientific racists about the need for segregation, especially in schools. Following that decision both scholarly and popular ideas of scientific racism played an important role in the attack and backlash that followed the court decision.

The ''Mankind Quarterly

''Mankind Quarterly'' is a pseudoscientific journal that covers physical and cultural anthropology, including human evolution, intelligence, ethnography, linguistics, mythology, archaeology, and biology. It has been described as a "cornersto ...

'' is a journal that has published scientific racism. It was founded in 1960, partly in response to the 1954 United States Supreme Court decision ''Brown v. Board of Education'', which ordered the desegregation of US schools. Many of the publication's contributors, publishers, and board of directors espouse academic hereditarianism. The publication is widely criticized for its extremist politics, antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

bent and its support for scientific racism.

In the South

After the end of Reconstruction and the withdrawal of federal troops, which followed from theCompromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement, the Tilden-Hayes Compromise, the Bargain of 1877, or Corrupt bargain, the Corrupt Bargain, was a speculated unwritten political deal in the United States to settle the intense dispute ...

, the Democratic governments in the South instituted state laws to separate black and white racial groups, submitting African Americans to ''de facto'' second-class citizenship and enforcing white supremacy

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine ...

. Collectively, these state laws were called the Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

system, after the name of a stereotypical 1830s black minstrel show

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of theater developed in the early 19th century. The shows were performed by mostly white actors wearing blackface makeup for the purpose of portraying racial stereotypes of Afr ...

character.Remembering Jim Crow– Minnesota Public Radio Sometimes, as in Florida's Constitution of 1885, segregation was mandated by state constitutions. Racial segregation became the law in most parts of the

American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is census regions United States Census Bureau. It is between the Atlantic Ocean and the ...

until the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. These laws, known as Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

, forced segregation of facilities and services, prohibited intermarriage, and denied suffrage. Impacts included:

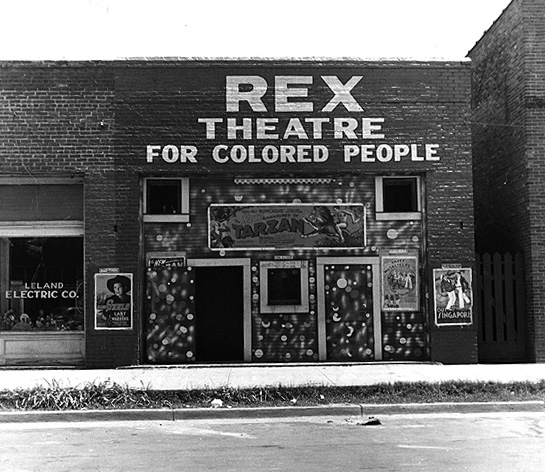

* Segregation of facilities included separate schools, hotels, bars, hospitals, toilets, parks, even telephone booths, and separate sections in libraries, cinemas, and restaurants, the latter often with separate ticket windows and counters.

** After Reconstruction, many southern states passed Jim Crow laws and followed the "separate but equal" doctrine created during the '' Plessy v. Ferguson'' case. Segregated libraries under this system existed in most parts of the south. The East Henry Street Carnegie library in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Brita ...

, built by African Americans during the segregation era in 1914 with help from the Carnegie foundation, is one example. Hundreds of segregated libraries existed across the United States prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. These libraries were often underfunded, understocked, and had fewer services than their white counterparts. Only during the landmark ''Brown v. Board of Education