Scuttling is the act of deliberately

sinking a ship by allowing water to flow into the hull, typically by its crew opening holes in its hull.

Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of

self-destruction to prevent the ship from being captured by an enemy force; as a

blockship to restrict navigation through a

channel or within a

harbor

A harbor (American English), or harbour (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be moored. The term ''harbor'' is often used interchangeably with ''port'', which is ...

; to provide an

artificial reef

An artificial reef (AR) is a human-created freshwater or marine benthic structure.

Typically built in areas with a generally featureless bottom to promote Marine biology#Reefs, marine life, it may be intended to control #Erosion prevention, erosio ...

for divers and marine life; or to alter the flow of rivers.

Notable historical examples

Skuldelev ships (around 1070)

The

Skuldelev ships, five

Viking ship

Viking ships were marine vessels of unique structure, used in Scandinavia throughout the Middle Ages.

The boat-types were quite varied, depending on what the ship was intended for, but they were generally characterized as being slender and flexi ...

s, were sunk to prevent attacks from the sea on the Danish city of

Roskilde

Roskilde ( , ) is a city west of Copenhagen on the Danish island of Zealand. With a population of 53,354 (), the city is a business and educational centre for the region and the 10th largest city in Denmark. It is governed by the administrative ...

. The scuttling blocked a major waterway, redirecting ships to a smaller one that required considerable local knowledge.

Cog near Kampen (early 15th century)

In 2012, a

cog preserved from the keel up to the decks in the silt was discovered alongside two smaller vessels in the river

IJssel

The IJssel (; ) is a Dutch distributary of the river Rhine that flows northward and ultimately discharges into the IJsselmeer (before the 1932 completion of the Afsluitdijk known as the Zuiderzee), a North Sea natural harbour. It more immediatel ...

in the city of

Kampen, in the

Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

. The ship, dating from the early 15th century, was suspected to have been deliberately sunk into the river to influence its current.

Hernán Cortés (1519)

The

Spanish conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (; ; ) were Spanish Empire, Spanish and Portuguese Empire, Portuguese colonizers who explored, traded with and colonized parts of the Americas, Africa, Oceania and Asia during the Age of Discovery. Sailing ...

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca (December 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions o ...

, who led the first expedition that resulted in the fall of the

Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire, also known as the Triple Alliance (, Help:IPA/Nahuatl, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ or the Tenochca Empire, was an alliance of three Nahuas, Nahua altepetl, city-states: , , and . These three city-states rul ...

, ordered his men to strip and scuttle his fleet to prevent the secretly planned return to

Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

by those loyal to Cuban Governor

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar. Their success would have halted his inland march and

conquest of the Aztec Empire.

HMS ''Sapphire'' (1696)

HMS ''Sapphire'' was a 32-gun,

fifth-rate sailing

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

of the Royal Navy in

Newfoundland Colony

Newfoundland was an English, and later British, colony established in 1610 on the island of Newfoundland. That followed decades of sporadic English settlement on the island, which was at first only seasonal. Newfoundland was made a Crown colony ...

to protect the English migratory fishery. The vessel was trapped in

Bay Bulls harbour by four French naval vessels led by Jacques-François de Brouillan. To avoid its capture, the English scuttled the vessel on 11 September 1696.

HMS ''Endeavour'' (1778)

HMS ''Endeavour'' was Captain

James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

's ship upon which he travelled to

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

. After being sold into private hands, she was finally scuttled in a blockade of

Narragansett Bay

Narragansett Bay is a bay and estuary on the north side of Rhode Island Sound covering , of which is in Rhode Island. The bay forms New England's largest estuary, which functions as an expansive natural harbor and includes a small archipelago. S ...

, Rhode Island in 1778.

Siege of Yorktown (1781)

The British sank one ship on 10 October 1781 to prevent it from being captured by the French fleet. Furthermore, the York River, while protected by the French Navy, also contained a few scuttled ships, which were meant to serve as a blockade should any British ships enter the river.

HMS ''Bounty'' (1790)

HMS ''Bounty'', after her crew mutinied, was scuttled by the mutineers in Bounty Bay off

Pitcairn Island on 23 January 1790.

Chesapeake Bay Flotilla (1814)

During the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, Commodore

Joshua Barney, of the U.S. Navy,

Chesapeake Bay Flotilla, sank all nineteen of his fighting vessels, to prevent them from being captured by the British, as he and his men marched, inland, in the

unsuccessful defense of Washington D.C.

Jan van Speijk (1831)

During the

Belgian war of independence, Dutch gunboat commander

Jan van Speijk

Jan Carel Josephus van Speyk (31 January 1802 – 5 February 1831) was a Royal Netherlands Navy officer who became a public hero in the Netherlands for his opposition to the Belgian Revolution.

Life

Early life

Born in Amsterdam in 1 ...

came under attack from a mob of Antwerp labourers. When they forced him and his crew to surrender, he ignited a barrel of gunpowder, thereby sinking his ship and killing himself and most of the crew. Van Speijk went on to become a national hero in the Netherlands.

Russian Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol (1854)

During the

Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

, in anticipation of the

siege of Sevastopol, the Russians scuttled ships of the

Black Sea Fleet

The Black Sea Fleet () is the Naval fleet, fleet of the Russian Navy in the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov and the Mediterranean Sea. The Black Sea Fleet, along with other Russian ground and air forces on the Crimea, Crimean Peninsula, are subordin ...

to protect the harbour, to use their naval cannon as additional artillery, and to free up the ships' crews as marines. Those ships that were deliberately sunk included ''Grand Duke Constantine'', ''City of Paris'' (both with

120 guns), ''Brave'', ''Empress Maria'', and ''Chesme.''

The Clotilda

The

Clotilda (slave ship) (often misspelled Clotilde) was the last known U.S.

slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting Slavery, slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea ( ...

to bring captives from Africa to the United States, arriving at

Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. T ...

, in autumn 1859 or on July 9, 1860, with 110 African men, women, and children. The ship was a two-masted

schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

, 86 feet (26 m) long with a beam of 23 ft (7.0 m).

U.S. involvement in the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

had been banned by Congress through the

Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves

The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 (, enacted March 2, 1807) is a United States federal law that prohibited the importation of slaves into the United States. It took effect on January 1, 1808, the earliest date permitted by the U ...

enacted on March 2, 1807 (effective January 1, 1808), but the practice continued illegally, especially through slave traders based in New York in the 1850s and early 1860. In the case of the Clotilda, the voyage's sponsors were based in the South and planned to buy Africans in

Kingdom of Whydah,

Dahomey

The Kingdom of Dahomey () was a West African List of kingdoms in Africa throughout history, kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. It developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in ...

. After the voyage, the ship was burned and scuttled in Mobile Bay in an attempt to destroy the evidence.

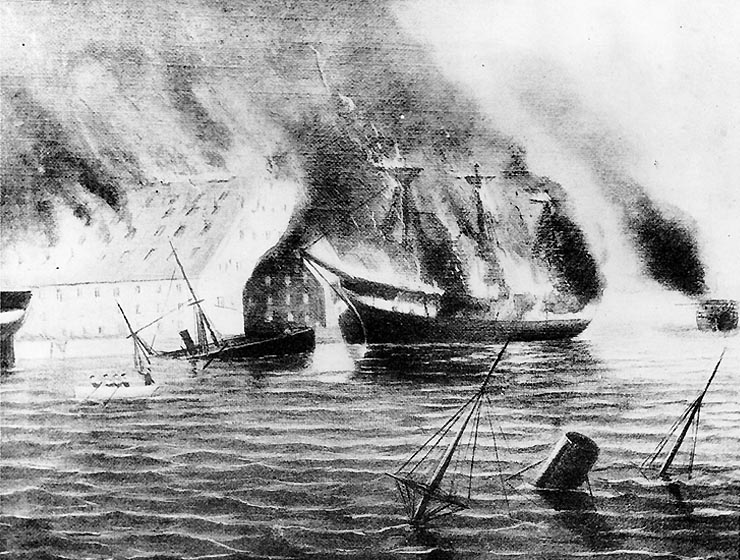

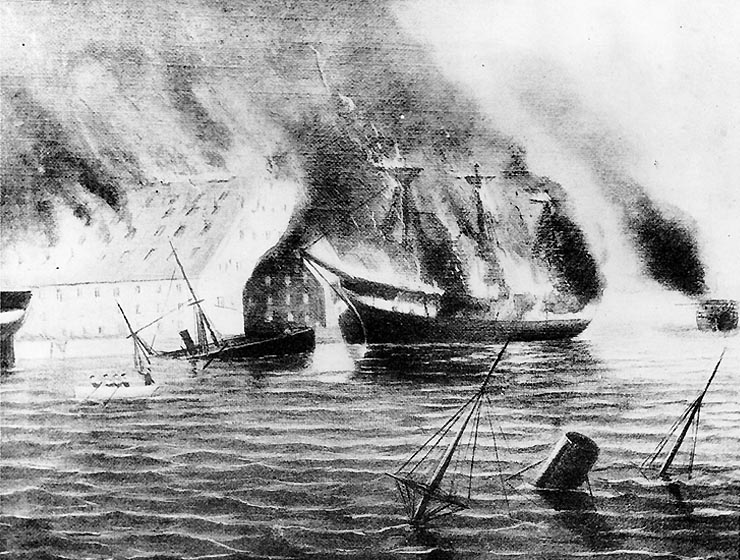

USS ''Merrimack''/CSS ''Virginia'' (1861)

In April 1861, the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

steam

Steam is water vapor, often mixed with air or an aerosol of liquid water droplets. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization. Saturated or superheated steam is inv ...

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

was among several ships

Union forces set afire or scuttled at the Gosport Navy Yard (now

Norfolk Naval Shipyard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling and repairing the Navy's ships. It is the oldest and largest industrial facility ...

) in

Portsmouth, Virginia

Portsmouth is an Independent city (United States), independent city in southeastern Virginia, United States. It lies across the Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth River from Norfolk, Virginia, Norfolk. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 ...

, to keep them from falling into

Confederate hands at the outbreak of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. The unsuccessful attempt at scuttling ''Merrimack'' enabled the

Confederate States Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

to raise and rebuild her as the

broadside ironclad CSS ''Virginia''. Shortly after her famous engagement with the U.S Navy

monitor

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, Wes ...

in the

Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Merrimack'' or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

The battle was fought over two days, March 8 and 9, 1862, in Hampton ...

in March 1862, the Confederates scuttled ''Virginia'' to keep her from being captured by Union forces.

Stone Fleet (1861–1862)

In December 1861 and January 1862,

Union forces scuttled a number of former

whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

s and other

merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

s in an attempt to block access to Confederate ports during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. Loaded with stone before being scuttled, the scuttled ships were known as the "

Stone Fleet". Those scuttled in December 1861 sometimes are called the "First Stone Fleet", while those sunk in January 1862 sometimes are termed the "Second Stone Fleet".

Peruvian fleet at El Callao (1881)

During the

War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific (), also known by War of the Pacific#Etymology, multiple other names, was a war between Chile and a Treaty of Defensive Alliance (Bolivia–Peru), Bolivian–Peruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought over Atacama Desert ...

, as Chilean troops entered

Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

and

El Callao, the Peruvian naval officer

Germán Astete ordered the whole Peruvian fleet to be scuttled to prevent capture by Chile.

USS ''Merrimac'' (1898)

During the

Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

, a volunteer crew of

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

personnel attempted to scuttle the

collier in the entrance to the harbor at

Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second-largest city in Cuba and the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province. It lies in the southeastern area of the island, some southeast of the Cuban capital of Havana.

The municipality extends over , and contains t ...

in

Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

on the night of 2–3 June 1898 in an attempt to trap the

Spanish Navy

The Spanish Navy, officially the Armada, is the Navy, maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation ...

squadron of

Vice Admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of Vice ...

Manuel de la Cámara y Libermoore in port there. The attempt failed when she came under fire by Spanish ships and fortifications and sank without blocking the entrance.

Port Arthur (1904–1905)

In 1904, during the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

, the

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

made three attempts to block the entrance to the

Imperial Russian Navy base at

Port Arthur,

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

,

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, by scuttling

transports. Although the Japanese scuttled five transports on 23 February, four on 27 March, and eight on 3 May, none of the attacks succeeded in blocking the entrance. The Russians also scuttled four

steamers

Steamer may refer to:

Transportation

* Steamboat, smaller, insular boat on lakes and rivers

* Steamship, ocean-faring ship

* Screw steamer, steamboat or ship that uses "screws" (propellers)

* Steam yacht, luxury or commercial yacht

* Paddle st ...

at the entrance in March 1904 in an attempt to defend the harbor from Japanese intrusion.

During the

siege of Port Arthur, the Russians scuttled the surviving ships of their

Pacific Squadron that were trapped in port at Port Arthur in late 1904 and early January 1905 to prevent their capture intact by the Japanese.

SMS ''Dresden'' (1915)

In December 1914, was the only German warship to escape destruction in the

Battle of the Falkland Islands

The Battle of the Falkland Islands was a First World War naval action between the British Royal Navy and Imperial German Navy on 8 December 1914 in the South Atlantic. The British, after their defeat at the Battle of Coronel on 1 November, ...

. She eluded her British pursuers for several more months, until she put into

Más a Tierra in March 1915. Her engines were worn out and she had almost no coal left for her boilers. There, she was trapped by British cruisers, which violated Chilean neutrality and opened fire on the ship. ''Dresden''s Executive Officer – the future Admiral

Wilhelm Canaris

Wilhelm Franz Canaris (1 January 1887 – 9 April 1945) was a admiral (Germany), German admiral and the chief of the ''Abwehr'' (the German military intelligence, military-intelligence service) from 1935 to 1944. Initially a supporter of Ad ...

– negotiated with the British and bought time for his crew to scuttle the ''Dresden''.

Zeebrugge Raid (1918)

The

Zeebrugge Raid involved three outdated British cruisers chosen to serve as

blockships in the German-held Belgian

port of Bruges-Zeebrugge from which German

U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

operations threatened British shipping.

''Thetis'',

''Intrepid'' and

''Iphigenia'' were filled with concrete then sent to block a critical canal. Heavy defensive fire caused the ''Thetis'' to scuttle prematurely; the other two cruisers sank themselves successfully in the narrowest part of the canal. Within three days, however, the Germans had broken through the western bank of the canal to create a shallow detour for their submarines to move past the blockships at high tide.

German fleet at Scapa Flow (1919)

In 1919, over 50 warships of the

German High Seas Fleet were scuttled by their crews at

Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and Hoy. Its sheltered waters have played an impor ...

in the north of

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, following the deliverance of the fleet as part of the terms of the German surrender. Rear Admiral

Ludwig von Reuter ordered the sinkings, denying the majority of the ships to the

Allies. Von Reuter was made a prisoner-of-war in Britain but his act of defiance was celebrated in Germany. Though most of the fleet was subsequently salvaged by engineer

Ernest Cox, a number of warships (including three battleships) remain, making the area very popular amongst undersea diving enthusiasts.

Washington Naval Treaty (1922)

Under the terms of the

Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting Navy, naval construction. It was negotiated at ...

of 1922, the great naval powers were required to limit the size of their battlefleets, resulting in the disposal of some older or incomplete

capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic i ...

s. During 1924 and 1925, the treaty resulted in the scuttling of the

Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the navy, naval branch of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (Australia), Chief of Navy (CN) Vice admiral (Australia), Vice Admiral Mark Hammond (admiral), Ma ...

battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

and the incomplete

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

''

Tosa'', while four old Japanese battleships, the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

battleship , and the incomplete

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

battleship all were disposed of as

targets

''Targets'' is a 1968 American crime thriller film directed by Peter Bogdanovich in his theatrical directorial debut, and starring Tim O'Kelly, Boris Karloff, Nancy Hsueh, Bogdanovich, James Brown, Arthur Peterson and Sandy Baron. The film ...

.

''Admiral Graf Spee'' (1939)

Following the

Battle of the River Plate the damaged German

pocket battleship sought refuge in the port of

Montevideo

Montevideo (, ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2023 census, the city proper has a population of 1,302,954 (about 37.2% of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

. On 17 December 1939, with the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

and

Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

cruisers , , and waiting in international waters outside the mouth of the

Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (; ), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda, Colonia, Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and ...

, Captain

Hans Langsdorff sailed ''Graf Spee'' just outside the harbour and scuttled the vessel to avoid risking the lives of his crew in what he expected would be a losing battle. Langsdorff shot himself three days later.

''San Giorgio'' at Tobruk (1941)

When British and Commonwealth land forces attacked

Tobruk

Tobruk ( ; ; ) is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near the border with Egypt. It is the capital of the Butnan District (formerly Tobruk District) and has a population of 120,000 (2011 est.)."Tobruk" (history), ''Encyclop� ...

on 21 January 1941, the Italian cruiser

''San Giorgio'' turned its guns against the attacking force, repelling an attack by tanks. As British forces were entering Tobruk, ''San Giorgio'' was scuttled at 4:15 AM on 22 January. ''San Giorgio'' was awarded the Gold Medal of Military Valor for her actions in the defence of Tobruk. The ship was salvaged in 1952, but while being towed to Italy, her tow rope failed and she sank in heavy seas.

Blockade of Massawa (1941)

As the Allies advanced toward

Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

during their

East African Campaign in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

,

Mario Bonetti—the Italian commander of the

Red Sea Flotilla based at

Massawa

Massawa or Mitsiwa ( ) is a port city in the Northern Red Sea Region, Northern Red Sea region of Eritrea, located on the Red Sea at the northern end of the Gulf of Zula beside the Dahlak Archipelago. It has been a historically important port for ...

—realized that the British would overrun his harbor. In the first week of April 1941, he began to destroy the harbor's facilities and ruin its usefulness to the Allies. Bonetti ordered the sinking of two large

floating dry docks and supervised the calculated scuttling of eighteen large commercial ships in the mouths of the north Naval Harbor, the central Commercial Harbor and the main South Harbor. This blocked navigation in and out. He also had a large floating crane scuttled. These actions rendered the harbor useless by 8 April 1941, when Bonetti surrendered it to the British. Scuttled ships included the German steamers

''Liebenfels'', ''Frauenfels'', , ''Crefeld'', ''Gera'' and ''Oliva''. Also scuttled were the Italian steamers ''Adua'', ''Brenta'', ''Arabia'', ''Romolo Gessi'', ''Vesuvio'', ''XXIII Marzo'', ''Antonia C.'', ''Riva Ligure'', ''Clelia Campenella'', ''Prometeo'' and the Italian tanker ''Giove''. The largest scuttled vessel was the 11,760-ton ''Colombo'', an Italian steamer. Thirteen coastal steamers and small naval vessels were also scuttled.

The British seized the harbor and initiated

marine salvage

Marine salvage is the process of recovering a ship and its cargo after a shipwreck or other maritime casualty. Salvage may encompass towing, lifting a vessel, or effecting repairs to a ship. Salvors are normally paid for their efforts. Howev ...

operations under Commander

Joseph Stenhouse to restore navigation in and out. Stenhouse was slowed by

heat exhaustion but his team refloated the oil tanker ''Giove''; he died in September 1941 when the salvage tug ''Tai Koo'' bearing him as a passenger was sunk by a naval mine in the Red Sea. His death left a civilian contractor to open a channel, but this crew made no progress. It was not until a year later that headway was made in the effort to return Massawa to military duties. U.S. Navy Commander

Edward Ellsberg arrived in April 1942 with a salvage crew and a small collection of specialized tools and began methodically correcting the damage. His salvage efforts yielded significant results in just 5½ weeks. American divers sealed the hulls underwater, and air was pumped in to float the hulls. The divers defused a

booby trap

A booby trap is a device or setup that is intended to kill, harm or surprise a human or an animal. It is triggered by the presence or actions of the victim and sometimes has some form of bait designed to lure the victim towards it. The trap may b ...

in ''Brenta'', which contained an armed

naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel mine, anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are ...

sitting on three torpedo warheads in the

hold. Another danger was ''

Regia Marina'' minelayer ''Ostia'', which had been sunk by the

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

with several of its mines still racked. On 8 May 1942, SS ''Koritza'', an armed Greek steamer, had drydocked for cleaning and minor hull repairs. Massawa's first major surface fleet "customer" was , which needed repairs to a heavily damaged stern in mid-August 1942, the beginning of a repair and maintenance period for the war-weary

15th Cruiser Squadron. Many of the harbor's sunken ships were patched by Ellsberg's divers, refloated, repaired and taken into service. ''Ostia'' and ''Brenta'' were successfully salvaged, despite their armed mines. All of this occurred while the British civil contractor struggled and failed to refloat one ship.

[

]

''Bismarck'' (1941)

In 1941, the battleship '' Bismarck'', heavily damaged by the Royal Navy, leaking fuel, listing, unable to steer and with no effective weapons, but still afloat and with engines running, was scuttled by its crew to avoid capture. This was supported by survivors' reports in ''Pursuit: the Sinking of the Bismarck'', by Ludovic Kennedy, 1974 and by a later examination of the wreck itself by Dr. Robert Ballard

Robert Duane Ballard (born June 30, 1942) is an American retired Navy officer and a professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island who is noted for his work in underwater archaeology (maritime archaeology and archaeology of ...

in 1989. A later, more advanced examination found torpedoes had penetrated the second deck, normally always above water and only possible on an already sinking ship, thus further supporting that scuttling had made the final torpedoing redundant.

Coral Sea and Midway (1942)

After the Battles of the Coral Sea

The Coral Sea () is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific off the northeast coast of Australia, and classified as an Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia, interim Australian bioregion. The Coral Sea extends down t ...

and Midway, the heavily damaged American aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

''Lexington'' and the Japanese carriers ''Hiryū'', ''Sōryū'', ''Akagi'', and ''Kaga'' were all scuttled to prevent their preservation and use by their respective enemies.

French fleet at Toulon (1942)

In November 1942, in an operation codenamed ''Case Anton

Case Anton () was the military occupation of Vichy France carried out by Germany and Italy in November 1942. It marked the end of the Vichy regime as a nominally independent state and the disbanding of its army (the severely-limited '' Armisti ...

'', Nazi German forces occupied the so-called " Free Zone" in response to the Allied landing in North Africa. On 27 November they reached Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

, where the majority of the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

was anchored. To avoid capture by the Nazis (Operation Lila), the French admirals-in-command ( Laborde and Marquis

A marquess (; ) is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German-language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman with the rank of a marquess or the wife (or wido ...

) decided to scuttle the 230,000 tonne fleet, most notably, the battleships '' Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg

Strasbourg ( , ; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est Regions of France, region of Geography of France, eastern France, in the historic region of Alsace. It is the prefecture of the Bas-Rhin Departmen ...

''. Eighty percent of the fleet was utterly destroyed, all of the capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic i ...

s proving impossible to repair. Legally, the scuttling of the fleet was allowed under the terms of the 1940 Armistice with Germany.

Danish fleet (1943)

Anticipating a German seizure of all units of the Danish Navy as part of Operation Safari, mostly in Copenhagen but also at other harbours and at sea in Danish waters, the Danish Admiralty had instructed its captains to resist, short of outright fighting, any German attempts to assume control over their vessels, by scuttling if escape to Sweden was not possible and suitable preparations were made. Of the fifty-two vessels in the Danish Navy on 29 August, two were in Greenland, thirty-two were scuttled, four reached Sweden and fourteen were taken undamaged by the Germans. Nine Danish sailors lost their lives and ten were wounded. Subsequently, major parts of the Naval personnel were interned for a period.

Allied landing in Normandy (1944)

Old ships code-named "Corn cobs" were sunk to form a protective reef for the Mulberry harbour

The Mulberry harbours were two temporary portable harbours developed by the Admiralty (United Kingdom), British Admiralty and War Office during the Second World War to facilitate the rapid offloading of cargo onto beaches during the Allies of ...

s at Arromanches and Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach was one of five beach landing sectors of the amphibious assault component of Operation Overlord during the Second World War.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies of World War II, Allies invaded German military administration in occupied Fra ...

for the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

. The sheltered waters created by these scuttled ships were called "Gooseberries" and protected the harbours so transport ships could unload without being hampered by waves.

Operation Deadlight (1945–1946)

Of the 156 German

Of the 156 German submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s ("U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s") surrendered to the Allies at the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, 116 were scuttled by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

in Operation Deadlight. Plans called for them to be scuttled in three areas in the North Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

west of Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, but 56 of the submarines sank before reaching the designated areas due to their poor material condition. Most of the submarines were sunk by gunfire rather than with explosive charges. The first sinking took place on 17 November 1945 and the last on 11 February 1946.[.]

Japanese submarines (1946)

To prevent a Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

inspection team from examining surrendered Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

submarines after World War II, the United States Navy conducted Operation Road's End, in which it scuttled 24 of the submarines in the East China Sea

The East China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean, located directly offshore from East China. China names the body of water along its eastern coast as "East Sea" (, ) due to direction, the name of "East China Sea" is otherwise ...

off Fukue Island

is the largest and southernmost of the Gotō Islands in Japan. It is part of the city of Gotō, Nagasaki, Gotō in Nagasaki Prefecture. Gotō-Fukue Airport is on this island. As of July 31, 2016, the population is 38,481.Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

near Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

in May and June 1946, and the Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the navy, naval branch of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (Australia), Chief of Navy (CN) Vice admiral (Australia), Vice Admiral Mark Hammond (admiral), Ma ...

sank six or seven (sources differ) surrendered Japanese submarines in the Seto Inland Sea

The , sometimes shortened to the Inland Sea, is the body of water separating Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, three of the four main islands of Japan. It serves as a waterway connecting the Pacific Ocean to the Sea of Japan. It connects to Osaka Ba ...

on 8 May 1946 in Operation Bottom.

Contemporary era

Today, ships (and other objects of similar size) are sometimes sunk to help form

Today, ships (and other objects of similar size) are sometimes sunk to help form artificial reef

An artificial reef (AR) is a human-created freshwater or marine benthic structure.

Typically built in areas with a generally featureless bottom to promote Marine biology#Reefs, marine life, it may be intended to control #Erosion prevention, erosio ...

s, as was done with the former in 2006. It is also common for military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

organizations to use old ships as targets

''Targets'' is a 1968 American crime thriller film directed by Peter Bogdanovich in his theatrical directorial debut, and starring Tim O'Kelly, Boris Karloff, Nancy Hsueh, Bogdanovich, James Brown, Arthur Peterson and Sandy Baron. The film ...

, in war games, or for various other experiments. As an example, the decommissioned aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

was subjected to surface and underwater explosions in 2005 as part of classified research to help design the next generation of carriers (the ), before being sunk with demolition charges.

Ships are increasingly being scuttled as a method of disposal. The economic benefit of scuttling a ship includes removal of ongoing operational expense to keep the vessel seaworthy. Controversy surrounds the practice. The USS ''Oriskany'' was scuttled with 700 pounds of PCBs remaining on board as a component in cable insulation, contravening the Stockholm Convention on safe disposal of persistent organic pollutant

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are organic compounds that are resistant to degradation through chemical, biological, and photolytic processes. They are toxic and adversely affect human health and the environment around the world. Because ...

s, which has zero tolerance for PCB dumping in marine environments. The planned scuttling of the Australian frigate at Avoca Beach, New South Wales in March 2010 was placed on hold after resident action groups aired concerns about possible impact on the area's tides and that the removal of dangerous substances from the ship was not thorough enough. Further cleanup work on the hulk was ordered, and despite further attempts to delay, ''Adelaide'' was scuttled on 13 April 2011.

Scuttled ships have been used as conveyance for dangerous materials. In the late 1960s, the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

scuttled SS ''Corporal Eric G. Gibson'' and SS ''Mormactern'' with VX nerve gas rockets aboard as part of Operation CHASE — "CHASE" being Pentagon shorthand for "Cut Holes and Sink 'Em." Other ships have been "chased" containing mustard agents, bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

s, land mine

A land mine, or landmine, is an explosive weapon often concealed under or camouflaged on the ground, and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets as they pass over or near it. Land mines are divided into two types: anti-tank mines, wh ...

s, and radioactive waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. It is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, nuclear decommissioning, rare-earth mining, and nuclear ...

.

In Somalian waters, pirate ships

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

captured are scuttled. Most nations have little interest in prosecuting the pirates, thus this is usually the only repercussion.

In March 2022, Ukraine scuttled the Ukrainian frigate Hetman Sahaidachny, a Krivak-class frigate, due to encroaching Russian offensive operations that threatened to capture the frigate.

In February 2023, the Brazilian Navy

The Brazilian Navy () is the navy, naval service branch of the Brazilian Armed Forces, responsible for conducting naval warfare, naval operations.

The navy was involved in War of Independence of Brazil#Naval action, Brazil's war of independence ...

scuttled the decommissioned aircraft carrier ''São Paulo'' into the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

, following the rejections of injunction

An injunction is an equitable remedy in the form of a special court order compelling a party to do or refrain from doing certain acts. It was developed by the English courts of equity but its origins go back to Roman law and the equitable rem ...

s from the Ministry of the Environment and the Federal Public Ministry.

In popular culture

The term "scuttling" is also used in science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may include information technology and robotics, biological manipulations, space ...

to describe intentionally destroying a spacecraft

A spacecraft is a vehicle that is designed spaceflight, to fly and operate in outer space. Spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including Telecommunications, communications, Earth observation satellite, Earth observation, Weather s ...

. For example, in ''The Expanse'', this is done by intentionally overloading the ship's fusion reactor

Fusion power is a proposed form of power generation that would generate electricity by using heat from nuclear fusion reactions. In a fusion process, two lighter atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, while releasing energy. Devices ...

.

References

Bibliography

*

{{Shiplife

Nautical terminology

Maritime history

Ship disposal

Artificial reefs

Scuttling is the act of deliberately sinking a ship by allowing water to flow into the hull, typically by its crew opening holes in its hull.

Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being captured by an enemy force; as a blockship to restrict navigation through a channel or within a

Scuttling is the act of deliberately sinking a ship by allowing water to flow into the hull, typically by its crew opening holes in its hull.

Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being captured by an enemy force; as a blockship to restrict navigation through a channel or within a  During the

During the  In April 1861, the

In April 1861, the  During the

During the  In 1919, over 50 warships of the German High Seas Fleet were scuttled by their crews at

In 1919, over 50 warships of the German High Seas Fleet were scuttled by their crews at  Of the 156 German

Of the 156 German  Today, ships (and other objects of similar size) are sometimes sunk to help form

Today, ships (and other objects of similar size) are sometimes sunk to help form