Scottish Literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Scottish literature is literature written in

Scottish literature is literature written in

After the collapse of Roman authority in the early fifth century, four major circles of political and cultural influence emerged in Northern Britain. In the east were the

After the collapse of Roman authority in the early fifth century, four major circles of political and cultural influence emerged in Northern Britain. In the east were the

Beginning in the later eighth century,

Beginning in the later eighth century,

''Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature''

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), . It is possible that more Middle Irish literature was written in medieval Scotland than is often thought, but has not survived because the Gaelic literary establishment of eastern Scotland died out before the fourteenth century. Thomas Owen Clancy has argued that the '' Lebor Bretnach'', the so-called "Irish Nennius", was written in Scotland, and probably at the monastery in Abernethy, but this text survives only from manuscripts preserved in Ireland. Other literary work that has survived includes that of the prolific poet Gille Brighde Albanach. About 1218, Gille Brighde wrote a poem—''Heading for Damietta''—on his experiences of the

In the late Middle Ages, early Scots, often simply called English, became the dominant language of the country. It was derived largely from Old English, with the addition of elements from Gaelic and French. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late fourteenth century onwards.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 60–7. It began to be adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French. By the fifteenth century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I onwards. As a result, Gaelic, once dominant north of the

In the late Middle Ages, early Scots, often simply called English, became the dominant language of the country. It was derived largely from Old English, with the addition of elements from Gaelic and French. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late fourteenth century onwards.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 60–7. It began to be adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French. By the fifteenth century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I onwards. As a result, Gaelic, once dominant north of the

Having extolled the virtues of Scots "poesie", following his accession to the English throne, James VI increasingly favoured the language of southern England. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the English

Having extolled the virtues of Scots "poesie", following his accession to the English throne, James VI increasingly favoured the language of southern England. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the English

After the Union in 1707 and the shift of political power to England, the use of Scots was discouraged by many in authority and education. Nevertheless, Scots remained the vernacular of many rural communities and the growing number of urban working-class Scots. Literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) was the most important literary figure of the era, often described as leading a "vernacular revival". He laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, publishing ''The Ever Green'' (1724), a collection that included many major poetic works of the Stewart period. He led the trend for

After the Union in 1707 and the shift of political power to England, the use of Scots was discouraged by many in authority and education. Nevertheless, Scots remained the vernacular of many rural communities and the growing number of urban working-class Scots. Literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) was the most important literary figure of the era, often described as leading a "vernacular revival". He laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, publishing ''The Ever Green'' (1724), a collection that included many major poetic works of the Stewart period. He led the trend for  James Macpherson was the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation, claiming to have found poetry written by

James Macpherson was the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation, claiming to have found poetry written by

Literary Style

". Retrieved 24 September 2010. Burns was skilled in writing not only in the Scots language but also in the

hae meat

. Retrieved 24 September 2010. His themes included

to the Kibble

" Retrieved 24 September 2010. Other major literary figures connected with Romanticism include the poets and novelists Drama was pursued by Scottish playwrights in London such as Catherine Trotter (1679–1749), born in London to Scottish parents and later moving to Aberdeen. Her plays and included the verse-tragedy ''Fatal Friendship'' (1698), the comedy ''Love at a Loss'' (1700) and the history ''The Revolution in Sweden'' (1706). David Crawford's (1665–1726) plays included the Restoration comedy, Restoration comedies ''Courtship A-la-Mode'' (1700) and ''Love at First Sight'' (1704). These developed the character of the stage Scot, often a clown, but cunning and loyal. Newburgh Hamilton (1691–1761), born in Ireland of Scottish descent, produced the comedies ''The Petticoat-Ploter'' (1712) and ''The Doating Lovers'' or ''The Libertine'' (1715). He later wrote the libretto for Handel's ''Samson (Handel), Samson'' (1743), closely based on John Milton's ''Samson Agonistes''. James Thomson's plays often dealt with the contest between public duty and private feelings, included ''Sophonisba'' (1730), ''Agamemnon'' (1738) and ''Tancrid and Sigismuda'' (1745), the last of which was an international success. David Mallet (writer), David Mallet's (c. 1705–65) ''Eurydice'' (1731) was accused of being a coded Jacobite play and his later work indicates opposition to the Robert Walpole, Walpole administration. The opera ''Masque of Alfred'' (1740) was a collaboration between Thompson, Mallet and composer Thomas Arne, with Thompson supplying the lyrics for his most famous work, the patriotic song "Rule, Britannia!".I. Brown, "Public and private performance: 1650–1800", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), , pp. 30–1.

In Scotland performances were largely limited to performances by visiting actors, who faced hostility from the Kirk. The Edinburgh Company of Players were able to perform in Dundee, Montrose, Aberdeen and regular performances at the Taylor's Hall in Edinburgh under the protection of a Royal Patent. Ramsay was instrumental in establishing them in a small theatre in Carruber's Close in Edinburgh,G. Garlick, "Theatre outside London, 1660–1775", in J. Milling, P. Thomson and J. Donohue, eds, ''The Cambridge History of British Theatre, Volume 2'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), , pp. 170–1. but the passing of the Licensing Act 1737, 1737 Licensing Act made their activities illegal and the theatre soon closed. A new theatre was opened at Cannongate in 1747 and operated without a licence into the 1760s. In the later eighteenth century, many plays were written for and performed by small amateur companies and were not published and so most have been lost. Towards the end of the century there were "closet dramas", primarily designed to be read, rather than performed, including work by Hogg, Galt and Joanna Baillie (1762–1851), often influenced by the ballad tradition and Gothic literature, Gothic Romanticism.I. Brown, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 229–30.

Drama was pursued by Scottish playwrights in London such as Catherine Trotter (1679–1749), born in London to Scottish parents and later moving to Aberdeen. Her plays and included the verse-tragedy ''Fatal Friendship'' (1698), the comedy ''Love at a Loss'' (1700) and the history ''The Revolution in Sweden'' (1706). David Crawford's (1665–1726) plays included the Restoration comedy, Restoration comedies ''Courtship A-la-Mode'' (1700) and ''Love at First Sight'' (1704). These developed the character of the stage Scot, often a clown, but cunning and loyal. Newburgh Hamilton (1691–1761), born in Ireland of Scottish descent, produced the comedies ''The Petticoat-Ploter'' (1712) and ''The Doating Lovers'' or ''The Libertine'' (1715). He later wrote the libretto for Handel's ''Samson (Handel), Samson'' (1743), closely based on John Milton's ''Samson Agonistes''. James Thomson's plays often dealt with the contest between public duty and private feelings, included ''Sophonisba'' (1730), ''Agamemnon'' (1738) and ''Tancrid and Sigismuda'' (1745), the last of which was an international success. David Mallet (writer), David Mallet's (c. 1705–65) ''Eurydice'' (1731) was accused of being a coded Jacobite play and his later work indicates opposition to the Robert Walpole, Walpole administration. The opera ''Masque of Alfred'' (1740) was a collaboration between Thompson, Mallet and composer Thomas Arne, with Thompson supplying the lyrics for his most famous work, the patriotic song "Rule, Britannia!".I. Brown, "Public and private performance: 1650–1800", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), , pp. 30–1.

In Scotland performances were largely limited to performances by visiting actors, who faced hostility from the Kirk. The Edinburgh Company of Players were able to perform in Dundee, Montrose, Aberdeen and regular performances at the Taylor's Hall in Edinburgh under the protection of a Royal Patent. Ramsay was instrumental in establishing them in a small theatre in Carruber's Close in Edinburgh,G. Garlick, "Theatre outside London, 1660–1775", in J. Milling, P. Thomson and J. Donohue, eds, ''The Cambridge History of British Theatre, Volume 2'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), , pp. 170–1. but the passing of the Licensing Act 1737, 1737 Licensing Act made their activities illegal and the theatre soon closed. A new theatre was opened at Cannongate in 1747 and operated without a licence into the 1760s. In the later eighteenth century, many plays were written for and performed by small amateur companies and were not published and so most have been lost. Towards the end of the century there were "closet dramas", primarily designed to be read, rather than performed, including work by Hogg, Galt and Joanna Baillie (1762–1851), often influenced by the ballad tradition and Gothic literature, Gothic Romanticism.I. Brown, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 229–30.

Scottish poetry is often seen as entering a period of decline in the nineteenth century,L. Mandell, "Nineteenth-century Scottish poetry", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 301–07. with a descent of into infantalism as exemplified by the highly popular Whistle Binkie anthologies (1830–90).G. Carruthers, ''Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), , pp. 58–9. However, Scotland continued to produce talented and successful poets, including weaver-poet William Thom (poet), William Thom (1799–1848), Lady Margaret Maclean Clephane Compton Northampton (d. 1830), William Edmondstoune Aytoun (1813–65) and Thomas Campbell (poet), Thomas Campbell (1777–1844), whose works were extensively reprinted in the period 1800–60. Among the most influential poets of the later nineteenth century were James Thomson (B.V.), James Thomson (1834–82) and John Davidson (poet), John Davidson (1857–1909), whose work would have a major impact on modernist poets including Hugh MacDiarmid, Wallace Stevens and T. S. Eliot.M. Lindsay and L. Duncan, ''The Edinburgh Book of Twentieth-century Scottish Poetry'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), , pp. xxxiv–xxxv. The Highland Clearances and widespread emigration significantly weakened Gaelic language and culture and had a profound impact on the nature of Gaelic poetry. The best poetry in this vein contained a strong element of protest, including Uilleam Mac Dhun Lèibhe's (William Livingstone, 1808–70) protest against the Islay and Seonaidh Phàdraig Iarsiadair's (John Smith, 1848–81) condemnation of those responsible for the clearances. The best known Gaelic poet of the era was Màiri Mhòr nan Óran (Mary MacPherson, 1821–98), whose evocation of place and mood has made her among the most enduring Gaelic poets.

Walter Scott began as a poet and also collected and published Scottish ballads. His first prose work, ''Waverley (novel), Waverley'' in 1814, is often called the first historical novel. It launched a highly successful career, with other historical novels such as ''Rob Roy (novel), Rob Roy'' (1817), ''The Heart of Midlothian'' (1818) and ''Ivanhoe'' (1820). Scott probably did more than any other figure to define and popularise Scottish cultural identity in the nineteenth century.

Scottish "national drama" emerged in the early 1800s, as plays with specifically Scottish themes began to dominate the Scottish stage.

The existing repertoire of Scottish-themed plays included John Home's ''Douglas (play), Douglas'' (1756) and Ramsay's ''The Gentle Shepherd'' (1725), with the last two being the most popular plays among amateur groups.I. Brown, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , p. 231. Scott was keenly interested in drama, becoming a shareholder in the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh, Theatre Royal, Edinburgh. Baillie's Highland themed ''The Family Legend'' was first produced in Edinburgh in 1810 with the help of Scott, as part of a deliberate attempt to stimulate a national Scottish drama. Scott also wrote five plays, of which ''Hallidon Hill'' (1822) and ''MacDuff's Cross'' (1822), were patriotic Scottish histories.I. Brown, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 185–6. Adaptations of the Waverley novels, largely first performed in minor theatres, rather than the larger Patent theatres, included ''The Lady in the Lake'' (1817), ''The Heart of Midlothian'' (1819), and ''Rob Roy'', which underwent over 1,000 performances in Scotland in this period. Also adapted for the stage were ''Guy Mannering'', ''The Bride of Lammermoor'' and ''The Abbot''. These highly popular plays saw the social range and size of the audience for theatre expand and helped shape theatre-going practices in Scotland for the rest of the century.

Scotland was also the location of two of the most important literary magazines of the era, ''The Edinburgh Review'', founded in 1802 and ''Blackwood's Magazine'', founded in 1817. Together they had a major impact on the development of British literature and drama in the era of Romanticism.

Thomas Carlyle, in such works as ''Sartor Resartus'' (1833–34), ''The French Revolution: A History'' (1837) and ''On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History'' (1841), profoundly influenced philosophy and literature of the age.

In the late 19th century, a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations.

Scottish poetry is often seen as entering a period of decline in the nineteenth century,L. Mandell, "Nineteenth-century Scottish poetry", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 301–07. with a descent of into infantalism as exemplified by the highly popular Whistle Binkie anthologies (1830–90).G. Carruthers, ''Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), , pp. 58–9. However, Scotland continued to produce talented and successful poets, including weaver-poet William Thom (poet), William Thom (1799–1848), Lady Margaret Maclean Clephane Compton Northampton (d. 1830), William Edmondstoune Aytoun (1813–65) and Thomas Campbell (poet), Thomas Campbell (1777–1844), whose works were extensively reprinted in the period 1800–60. Among the most influential poets of the later nineteenth century were James Thomson (B.V.), James Thomson (1834–82) and John Davidson (poet), John Davidson (1857–1909), whose work would have a major impact on modernist poets including Hugh MacDiarmid, Wallace Stevens and T. S. Eliot.M. Lindsay and L. Duncan, ''The Edinburgh Book of Twentieth-century Scottish Poetry'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), , pp. xxxiv–xxxv. The Highland Clearances and widespread emigration significantly weakened Gaelic language and culture and had a profound impact on the nature of Gaelic poetry. The best poetry in this vein contained a strong element of protest, including Uilleam Mac Dhun Lèibhe's (William Livingstone, 1808–70) protest against the Islay and Seonaidh Phàdraig Iarsiadair's (John Smith, 1848–81) condemnation of those responsible for the clearances. The best known Gaelic poet of the era was Màiri Mhòr nan Óran (Mary MacPherson, 1821–98), whose evocation of place and mood has made her among the most enduring Gaelic poets.

Walter Scott began as a poet and also collected and published Scottish ballads. His first prose work, ''Waverley (novel), Waverley'' in 1814, is often called the first historical novel. It launched a highly successful career, with other historical novels such as ''Rob Roy (novel), Rob Roy'' (1817), ''The Heart of Midlothian'' (1818) and ''Ivanhoe'' (1820). Scott probably did more than any other figure to define and popularise Scottish cultural identity in the nineteenth century.

Scottish "national drama" emerged in the early 1800s, as plays with specifically Scottish themes began to dominate the Scottish stage.

The existing repertoire of Scottish-themed plays included John Home's ''Douglas (play), Douglas'' (1756) and Ramsay's ''The Gentle Shepherd'' (1725), with the last two being the most popular plays among amateur groups.I. Brown, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , p. 231. Scott was keenly interested in drama, becoming a shareholder in the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh, Theatre Royal, Edinburgh. Baillie's Highland themed ''The Family Legend'' was first produced in Edinburgh in 1810 with the help of Scott, as part of a deliberate attempt to stimulate a national Scottish drama. Scott also wrote five plays, of which ''Hallidon Hill'' (1822) and ''MacDuff's Cross'' (1822), were patriotic Scottish histories.I. Brown, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 185–6. Adaptations of the Waverley novels, largely first performed in minor theatres, rather than the larger Patent theatres, included ''The Lady in the Lake'' (1817), ''The Heart of Midlothian'' (1819), and ''Rob Roy'', which underwent over 1,000 performances in Scotland in this period. Also adapted for the stage were ''Guy Mannering'', ''The Bride of Lammermoor'' and ''The Abbot''. These highly popular plays saw the social range and size of the audience for theatre expand and helped shape theatre-going practices in Scotland for the rest of the century.

Scotland was also the location of two of the most important literary magazines of the era, ''The Edinburgh Review'', founded in 1802 and ''Blackwood's Magazine'', founded in 1817. Together they had a major impact on the development of British literature and drama in the era of Romanticism.

Thomas Carlyle, in such works as ''Sartor Resartus'' (1833–34), ''The French Revolution: A History'' (1837) and ''On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History'' (1841), profoundly influenced philosophy and literature of the age.

In the late 19th century, a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations.

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by modernism and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure in the movement was Hugh MacDiarmid (the pseudonym of Christopher Murray Grieve). MacDiarmid attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature in poetic works including "A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle" (1936), developing a form of Synthetic Scots that combined different regional dialects and archaic terms. Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poets Edwin Muir and William Soutar, the novelists Neil Gunn, George Blake (novelist), George Blake, Nan Shepherd, A. J. Cronin, Naomi Mitchison, Eric Linklater and Lewis Grassic Gibbon, and the playwright James Bridie. All were born within a fifteen-year period (1887–1901) and, although they cannot be described as members of a single school they all pursued an exploration of identity, rejecting nostalgia and parochialism and engaging with social and political issues. This period saw the emergence of a tradition of popular or working class theatre. Hundreds of amateur groups were established, particularly in the growing urban centres of the Lowlands. Amateur companies encouraged native playwrights, including Robert McLellan.

Some writers that emerged after the Second World War followed MacDiarmid by writing in Scots, including Robert Garioch and Sydney Goodsir Smith. Others demonstrated a greater interest in English language poetry, among them Norman MacCaig, George Bruce and Maurice Lindsay (broadcaster), Maurice Lindsay. George Mackay Brown from Orkney, and Iain Crichton Smith from Lewis, wrote both poetry and prose fiction shaped by their distinctive island backgrounds. The Glaswegian poet Edwin Morgan became known for translations of works from a wide range of European languages. He was also the first Scots Makar (the official national poet), appointed by the inaugural Scottish government in 2004. The shift to drama that focused on working class life in the post-war period gained momentum with Robert McLeish's ''The Gorbals Story'' and the work of Ena Lamont Stewart, Robert Kemp (playwright), Robert Kemp and George Munro.J. MacDonald, "Theatre in Scotland" in B. Kershaw and P. Thomson, ''The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), , p. 208. Many major Scottish post-war novelists, such as Muriel Spark, James Kennaway, Alexander Trocchi, Jessie Kesson and Robin Jenkins spent much or most of their lives outside Scotland, but often dealt with Scottish themes, as in Spark's Edinburgh-set ''The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (novel), The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie'' (1961) and Kennaway's script for the film ''Tunes of Glory'' (1956). Successful mass-market works included the action novels of Alistair MacLean, and the historical fiction of Dorothy Dunnett. A younger generation of novelists that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s included Shena Mackay, Alan Spence, Allan Massie and the work of William McIlvanney.

From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers focused around meetings in the house of critic, poet and teacher Philip Hobsbaum. Also important in the movement was Peter Kravitz, editor of Birlinn (publisher), Polygon Books. Members of the group that would come to prominence as writers included James Kelman, Alasdair Gray, Liz Lochhead, Tom Leonard (poet), Tom Leonard and Aonghas MacNeacail. In the 1990s major, prize winning, Scottish novels that emerged from this movement included

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by modernism and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure in the movement was Hugh MacDiarmid (the pseudonym of Christopher Murray Grieve). MacDiarmid attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature in poetic works including "A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle" (1936), developing a form of Synthetic Scots that combined different regional dialects and archaic terms. Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poets Edwin Muir and William Soutar, the novelists Neil Gunn, George Blake (novelist), George Blake, Nan Shepherd, A. J. Cronin, Naomi Mitchison, Eric Linklater and Lewis Grassic Gibbon, and the playwright James Bridie. All were born within a fifteen-year period (1887–1901) and, although they cannot be described as members of a single school they all pursued an exploration of identity, rejecting nostalgia and parochialism and engaging with social and political issues. This period saw the emergence of a tradition of popular or working class theatre. Hundreds of amateur groups were established, particularly in the growing urban centres of the Lowlands. Amateur companies encouraged native playwrights, including Robert McLellan.

Some writers that emerged after the Second World War followed MacDiarmid by writing in Scots, including Robert Garioch and Sydney Goodsir Smith. Others demonstrated a greater interest in English language poetry, among them Norman MacCaig, George Bruce and Maurice Lindsay (broadcaster), Maurice Lindsay. George Mackay Brown from Orkney, and Iain Crichton Smith from Lewis, wrote both poetry and prose fiction shaped by their distinctive island backgrounds. The Glaswegian poet Edwin Morgan became known for translations of works from a wide range of European languages. He was also the first Scots Makar (the official national poet), appointed by the inaugural Scottish government in 2004. The shift to drama that focused on working class life in the post-war period gained momentum with Robert McLeish's ''The Gorbals Story'' and the work of Ena Lamont Stewart, Robert Kemp (playwright), Robert Kemp and George Munro.J. MacDonald, "Theatre in Scotland" in B. Kershaw and P. Thomson, ''The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), , p. 208. Many major Scottish post-war novelists, such as Muriel Spark, James Kennaway, Alexander Trocchi, Jessie Kesson and Robin Jenkins spent much or most of their lives outside Scotland, but often dealt with Scottish themes, as in Spark's Edinburgh-set ''The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (novel), The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie'' (1961) and Kennaway's script for the film ''Tunes of Glory'' (1956). Successful mass-market works included the action novels of Alistair MacLean, and the historical fiction of Dorothy Dunnett. A younger generation of novelists that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s included Shena Mackay, Alan Spence, Allan Massie and the work of William McIlvanney.

From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers focused around meetings in the house of critic, poet and teacher Philip Hobsbaum. Also important in the movement was Peter Kravitz, editor of Birlinn (publisher), Polygon Books. Members of the group that would come to prominence as writers included James Kelman, Alasdair Gray, Liz Lochhead, Tom Leonard (poet), Tom Leonard and Aonghas MacNeacail. In the 1990s major, prize winning, Scottish novels that emerged from this movement included

The Spread of Scottish Printing

digitised items between 1508 and 1900 {{DEFAULTSORT:Scottish Literature Scottish literature, European literature

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

or by Scottish writers

This list of Scottish writers is an incomplete alphabetical list of Scottish writers who have a Wikipedia page. Those on the list were born and/or brought up in Scotland. They include writers of all genres, writing in English, Scots language, Lowl ...

. It includes works in English, Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

, Scots, Brythonic, French, Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, Norn or other languages written within the modern boundaries of Scotland.

The earliest extant literature written in what is now Scotland, was composed in Brythonic speech in the sixth century and has survived as part of Welsh literature

Welsh literature is any literature originating from Wales or by Welsh writers:

*Welsh-language literature

Welsh-language literature () has been produced continuously since the emergence of Welsh from Brythonic as a distinct language in a ...

. In the following centuries there was literature in Latin, under the influence of the Catholic Church, and in Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

, brought by Anglian settlers. As the state of Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English-language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kingd ...

developed into the kingdom of Scotland from the eighth century, there was a flourishing literary elite who regularly produced texts in both Gaelic and Latin, sharing a common literary culture with Ireland and elsewhere. After the Davidian Revolution

The Davidian Revolution is a name given by many scholars to the changes which took place in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of David I (1124–1153). These included his foundation of burghs, implementation of the ideals of Gregoria ...

of the thirteenth century a flourishing French language culture predominated, while Norse literature was produced from areas of Scandinavian settlement. The first surviving major text in Early Scots literature is the fourteenth-century poet John Barbour's epic '' Brus'', which was followed by a series of vernacular versions of medieval romances. These were joined in the fifteenth century by Scots prose works.

In the early modern era royal patronage supported poetry, prose and drama. James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV a ...

's court saw works such as Sir David Lindsay of the Mount's '' The Thrie Estaitis''. In the late sixteenth century James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

became patron and member of a circle of Scottish court poets and musicians known as the Castalian Band. When he acceded to the English throne in 1603 many followed him to the new court, but without a centre of royal patronage the tradition of Scots poetry subsided. It was revived after union with England in 1707 by figures including Allan Ramsay and James Macpherson. The latter's Ossian

Ossian (; Irish Gaelic/Scottish Gaelic: ''Oisean'') is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as ''Fingal'' (1761) and ''Temora (poem), Temora'' (1763), and later c ...

Cycle made him the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation. He helped inspire Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

, considered by many to be the national poet, and Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

, whose Waverley Novels

The Waverley novels are a long series of novels by Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832). For nearly a century, they were among the most popular and widely read novels in Europe.

Because Scott did not publicly acknowledge authorship until 1827, the se ...

did much to define Scottish identity in the nineteenth century. Towards the end of the Victorian era a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations, including Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll ...

, Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

, J. M. Barrie

Sir James Matthew Barrie, 1st Baronet, (; 9 May 1860 19 June 1937) was a Scottish novelist and playwright, best remembered as the creator of Peter Pan. He was born and educated in Scotland and then moved to London, where he wrote several succe ...

and George MacDonald.

In the twentieth century there was a surge of activity in Scottish literature, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure, Hugh MacDiarmid, attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature. Members of the movement were followed by a new generation of post-war poets including Edwin Morgan, who would be appointed the first Scots Makar by the inaugural Scottish government in 2004. From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with writers including James Kelman and Irvine Welsh

Irvine Welsh (born 27 September 1958) is a Scottish novelist and short story writer. His 1993 novel ''Trainspotting (novel), Trainspotting'' was made into a Trainspotting (film), film of the same name. He has also written plays and screenplays, ...

. Scottish poets who emerged in the same period included Carol Ann Duffy

Dame Carol Ann Duffy (born 23 December 1955) is a Scottish poet and playwright. She is a professor of contemporary poetry at Manchester Metropolitan University, and was appointed Poet Laureate in May 2009, and her term expired in 2019. She wa ...

, who was named as the first Scot to be UK Poet Laureate in May 2009.

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

After the collapse of Roman authority in the early fifth century, four major circles of political and cultural influence emerged in Northern Britain. In the east were the

After the collapse of Roman authority in the early fifth century, four major circles of political and cultural influence emerged in Northern Britain. In the east were the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

, whose kingdoms eventually stretched from the river Forth to Shetland. In the west were the Gaelic (Goidelic

The Goidelic ( ) or Gaelic languages (; ; ) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from Ireland through the Isle o ...

)-speaking people of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

, who had close links with Ireland, from where they brought with them the name Scots. In the south were the British ( Brythonic-speaking) descendants of the peoples of the Roman-influenced kingdoms of " The Old North", the most powerful and longest surviving of which was the Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde (, "valley of the River Clyde, Clyde"), also known as Cumbria, was a Celtic Britons, Brittonic kingdom in northern Britain during the Scotland in the Middle Ages, Middle Ages. It comprised parts of what is now southern Scotland an ...

. Finally, there were the English or "Angles", Germanic invaders who had overrun much of southern Britain and held the Kingdom of Bernicia

Bernicia () was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was approximately equivalent to the modern English cou ...

(later the northern part of Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

), which reached into what are now the Lothians and the Scotiish Borders in the south-east. To these Christianisation, particularly from the sixth century, added Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

as an intellectual and written language. Modern scholarship, based on surviving placenames and historical evidence, indicates that the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

spoke a Brythonic language, but none of their literature seems to have survived into the modern era. However, there is surviving literature from what would become Scotland in Brythonic, Gaelic, Latin and Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

.

Much of the earliest Welsh literature

Welsh literature is any literature originating from Wales or by Welsh writers:

*Welsh-language literature

Welsh-language literature () has been produced continuously since the emergence of Welsh from Brythonic as a distinct language in a ...

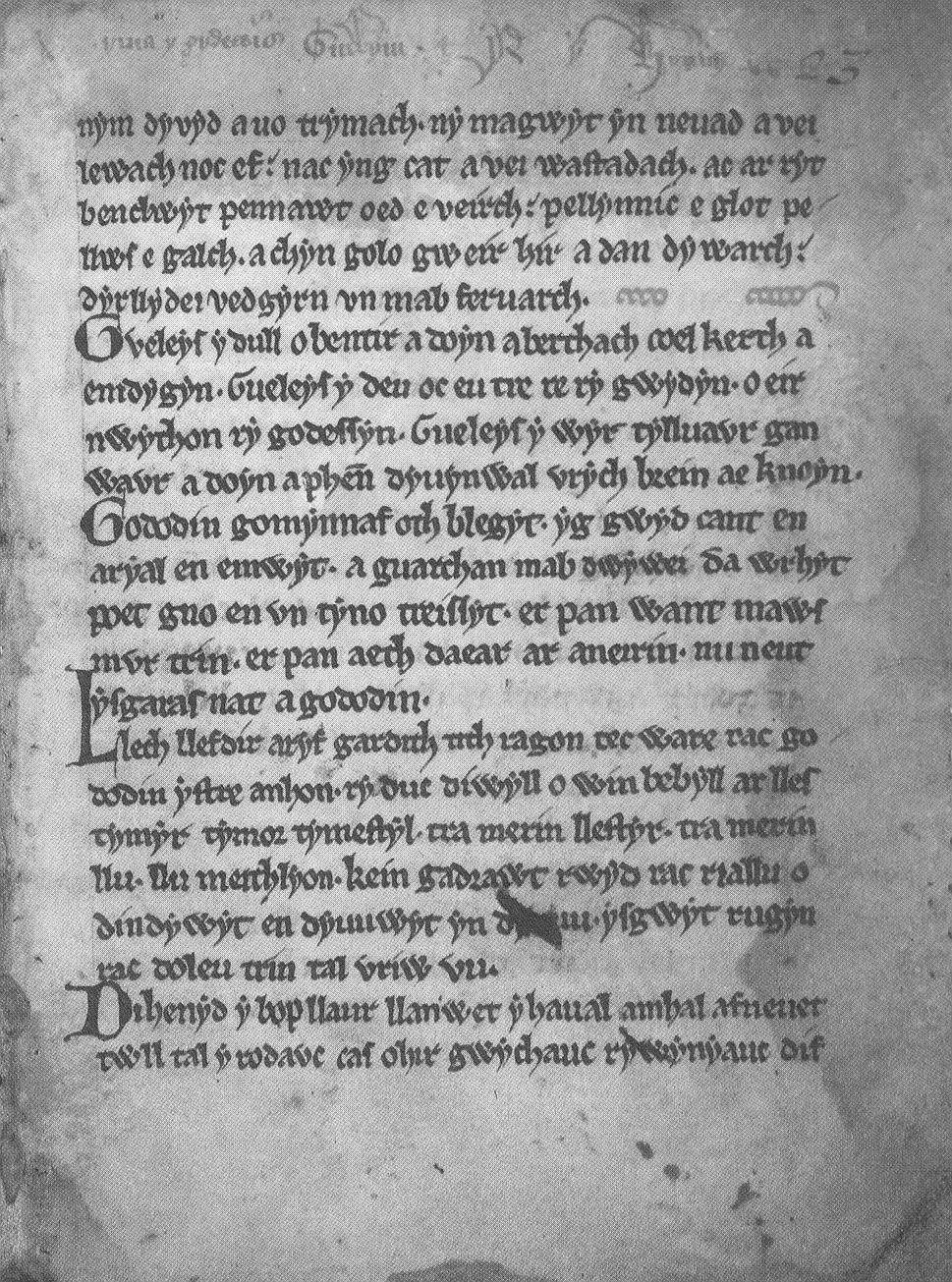

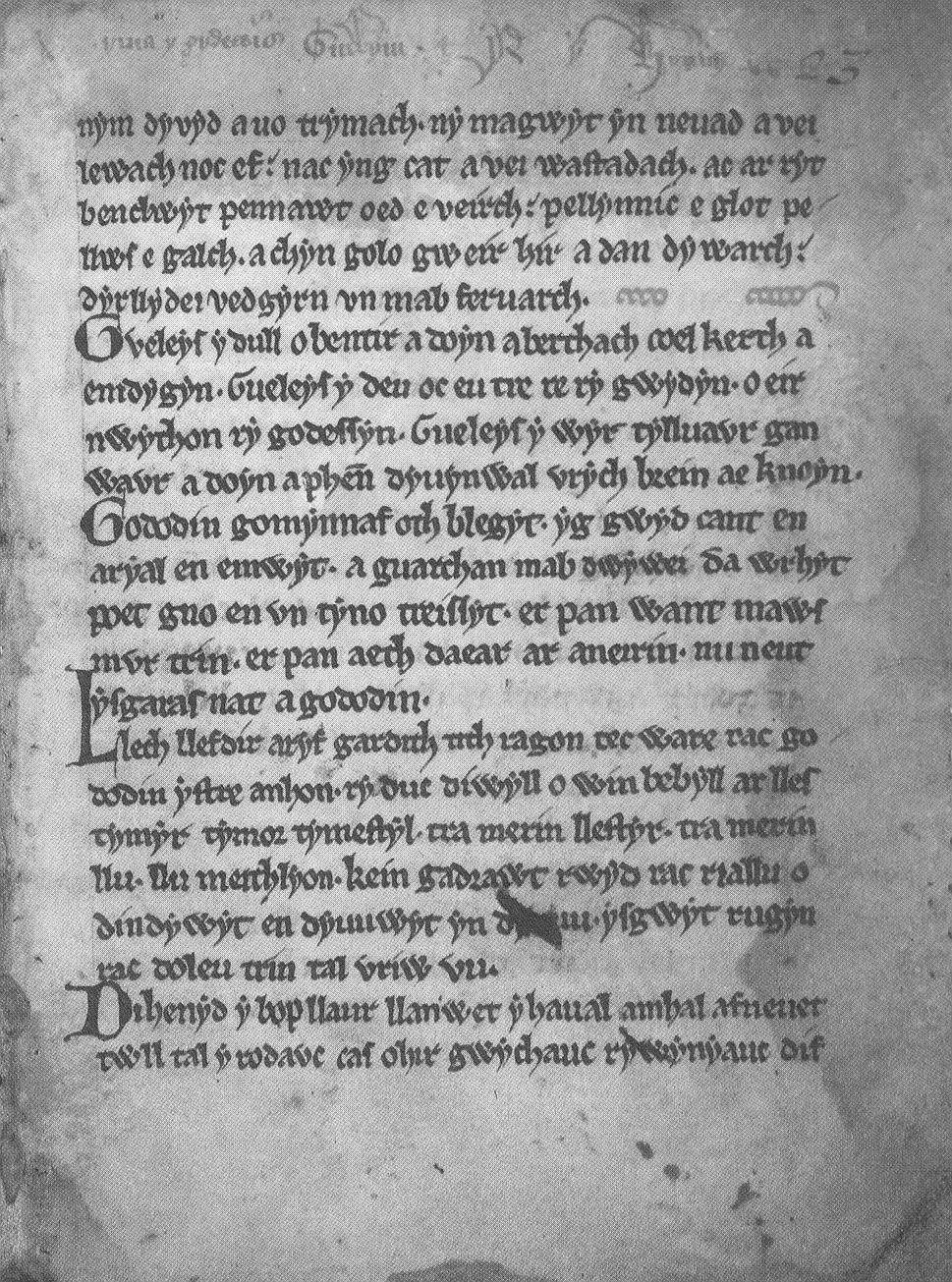

was actually composed in or near the country we now call Scotland, in the Brythonic speech, from which Welsh would be derived, which was not then confined to Wales and Cornwall, although it was only written down in Wales much later. These include ''The Gododdin

The Gododdin () were a Brittonic people of north-eastern Britannia, the area known as the Hen Ogledd or Old North (modern south-east Scotland and north-east England), in the sub-Roman period. Descendants of the Votadini, they are best known ...

'', considered the earliest surviving verse from Scotland, which is attributed to the bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is an oral repository and professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's a ...

Aneirin

Aneirin (), also rendered as Aneurin or Neirin and Aneurin Gwawdrydd, was an early Medieval Brythonic war poet who lived during the 6th century. He is believed to have been a bard or court poet in one of the Cumbric kingdoms of the Hen Ogledd ...

, said to have been resident in Brythonic kingdom of Gododdin in the sixth century. It is a series of elegies to the men of the Gododdin killed fighting at the ''Battle of Catraeth

The Battle of Catraeth was fought around AD 600 between a force raised by the Gododdin, a Brythonic people of the ''Hen Ogledd'' or "Old North" of Britain, and the Angles of Bernicia and Deira. It was evidently an assault by the Gododdin ...

'' around 600 AD. Similarly, the '' Battle of Gwen Ystrad'' is attributed to Taliesin

Taliesin ( , ; 6th century AD) was an early Britons (Celtic people), Brittonic poet of Sub-Roman Britain whose work has possibly survived in a Middle Welsh manuscript, the ''Book of Taliesin''. Taliesin was a renowned bard who is believed to ...

, traditionally thought to be a bard at the court of Rheged

Rheged () was one of the kingdoms of the ('Old North'), the Brittonic-speaking region of what is now Northern England and southern Scotland, during the post-Roman era and Early Middle Ages. It is recorded in several poetic and bardic sources, ...

in roughly the same period.

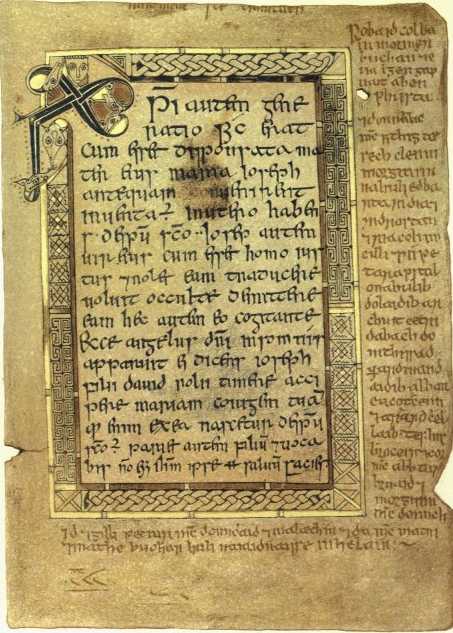

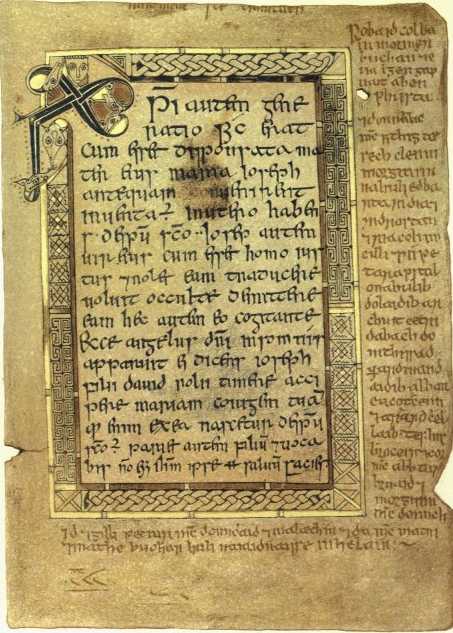

There are religious works in Gaelic including the ''Elegy for St Columba

Columba () or Colmcille (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is today Scotland at the start of the Hiberno-Scottish mission. He founded the important abbey ...

'' by Dallan Forgaill, c. 597 and "In Praise of St Columba" by Beccan mac Luigdech of Rum, c. 677. In Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

they include a "Prayer for Protection" (attributed to St Mugint), c. mid-sixth century and '' Altus Prosator'' ("The High Creator", attributed to St Columba), c. 597. What is arguably the most important medieval work written in Scotland, the '' Vita Columbae'', by Adomnán

Adomnán or Adamnán of Iona (; , ''Adomnanus''; 624 – 704), also known as Eunan ( ; from ), was an abbot of Iona Abbey ( 679–704), hagiographer, statesman, canon jurist, and Christian saint, saint. He was the author of the ''Life ...

, abbot of Iona (627/8–704), was also written in Latin. The next most important piece of Scottish hagiography, the verse '' Life of St. Ninian'', was written in Latin in Whithorn

Whithorn (; ), is a royal burgh in the historic county of Wigtownshire in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, about south of Wigtown. The town was the location of the first recorded Christian church in Scotland, "White/Shining House", built by ...

in the eighth century.

In Old English there is ''The Dream of the Rood

''The'' ''Dream of the Rood'' is one of the Christian poems in the corpus of Old English literature and an example of the genre of dream poetry. Like most Old English poetry, it is written in alliterative verse. The word ''Rood'' is derived f ...

'', from which lines are found on the Ruthwell Cross, making it the only surviving fragment of Northumbrian Old English from early Medieval Scotland. It has also been suggested on the basis of ornithological references that the poem '' The Seafarer'' was composed somewhere near the Bass Rock in East Lothian.

High Middle Ages

Beginning in the later eighth century,

Beginning in the later eighth century, Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

raids and invasions may have forced a merger of the Gaelic and Pictish crowns that culminated in the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s, which brought to power the House of Alpin

The House of Alpin, also known as the Alpinid dynasty, Clann Chináeda, and Clann Chinaeda meic Ailpín, was the kin-group which ruled in Pictland, possibly Dál Riata, and then the kingdom of Alba from Constantine II (Causantín mac Áeda) ...

and the creation of the Kingdom of Alba

The Kingdom of Alba (; ) was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286. The latter's death led indirectly to an invasion of Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 and the First War of Scotti ...

.B. Yorke, ''The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c.600–800'' (Pearson Education, 2006), , p. 54. Historical sources, as well as place name evidence, indicate the ways in which the Pictish language in the north and Cumbric languages in the south were overlaid and replaced by Gaelic, Old English and later Norse. The Kingdom of Alba was overwhelmingly an oral society dominated by Gaelic culture. Our fuller sources for Ireland of the same period suggest that there would have been filidh, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge and culture in Gaelic to the next generation.R. A. Houston, ''Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), , p. 76.

From the eleventh century French, Flemish and particularly English became the main languages of Scottish burgh

A burgh ( ) is an Autonomy, autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots language, Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when David I of Scotland, King David I created ...

s, most of which were located in the south and east. At least from the accession of David I (r. 1124–53), as part of a Davidian Revolution

The Davidian Revolution is a name given by many scholars to the changes which took place in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of David I (1124–1153). These included his foundation of burghs, implementation of the ideals of Gregoria ...

that introduced French culture and political systems, Gaelic ceased to be the main language of the royal court and was probably replaced by French. After this " gallicisation" of the Scottish court, a less highly regarded order of bards took over the functions of the filidh and they would continue to act in a similar role in the Highlands and Islands into the eighteenth century. They often trained in bardic schools, of which a few, like the one run by the MacMhuirich dynasty, who were bards to the Lord of the Isles

Lord of the Isles or King of the Isles

( or ; ) is a title of nobility in the Baronage of Scotland with historical roots that go back beyond the Kingdom of Scotland. It began with Somerled in the 12th century and thereafter the title was ...

, existed in Scotland and a larger number in Ireland, until they were suppressed from the seventeenth century. Members of bardic schools were trained in the complex rules and forms of Gaelic poetry. Much of their work was never written down and what survives was only recorded from the sixteenth century.R. Crawford''Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature''

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), . It is possible that more Middle Irish literature was written in medieval Scotland than is often thought, but has not survived because the Gaelic literary establishment of eastern Scotland died out before the fourteenth century. Thomas Owen Clancy has argued that the '' Lebor Bretnach'', the so-called "Irish Nennius", was written in Scotland, and probably at the monastery in Abernethy, but this text survives only from manuscripts preserved in Ireland. Other literary work that has survived includes that of the prolific poet Gille Brighde Albanach. About 1218, Gille Brighde wrote a poem—''Heading for Damietta''—on his experiences of the

Fifth Crusade

The Fifth Crusade (September 1217 - August 29, 1221) was a campaign in a series of Crusades by Western Europeans to reacquire Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land by first conquering Egypt, ruled by the powerful Ayyubid sultanate, led by al- ...

.

In the thirteenth century, French flourished as a literary language

Literary language is the Register (sociolinguistics), register of a language used when writing in a formal, academic writing, academic, or particularly polite tone; when speaking or writing in such a tone, it can also be known as formal language. ...

, and produced the ''Roman de Fergus

The ''Roman de Fergus'' is an Arthurian romance written in Old French probably at the very beginning of the 13th century, by a very well educated author who named himself Guillaume le Clerc (William the Clerk). The main character is Fergus, ...

'', the earliest piece of non-Celtic vernacular

Vernacular is the ordinary, informal, spoken language, spoken form of language, particularly when perceptual dialectology, perceived as having lower social status or less Prestige (sociolinguistics), prestige than standard language, which is mor ...

literature to survive from Scotland. Many other stories in the Arthurian Cycle

The Matter of Britain (; ; ; ) is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. The 12th-century writer Geoffr ...

, written in French and preserved only outside Scotland, are thought by some scholars including D. D. R. Owen, to have been written in Scotland. There is some Norse literature from areas of Scandinavian settlement, such as the Northern Isles

The Northern Isles (; ; ) are a chain (or archipelago) of Island, islands of Scotland, located off the north coast of the Scottish mainland. The climate is cool and temperate and highly influenced by the surrounding seas. There are two main is ...

and the Western Isles

The Outer Hebrides ( ) or Western Isles ( , or ), sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island (), is an island chain off the west coast of mainland Scotland.

It is the longest archipelago in the British Isles. The islands form part ...

. The famous ''Orkneyinga Saga

The ''Orkneyinga saga'' (Old Norse: ; ; also called the ''History of the Earls of Orkney'' and ''Jarls' Saga'') is a narrative of the history of the Orkney and Shetland islands and their relationship with other local polities, particularly No ...

'' however, although it pertains to the Earldom of Orkney

The Earldom of Orkney was a Norse territory ruled by the earls (or ''jarls'') of Orkney from the ninth century until 1472. It was founded during the Viking Age by Viking raiders and settlers from Scandinavia (see Scandinavian Scotland). In ...

, was written in Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

. In addition to French, Latin too was a literary language, with works that include the "Carmen de morte Sumerledi", a poem which exults triumphantly the victory of the citizens of Glasgow over Somairle mac Gilla Brigte and the "Inchcolm Antiphoner", a hymn in praise of St. Columba.

Late Middle Ages

In the late Middle Ages, early Scots, often simply called English, became the dominant language of the country. It was derived largely from Old English, with the addition of elements from Gaelic and French. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late fourteenth century onwards.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 60–7. It began to be adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French. By the fifteenth century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I onwards. As a result, Gaelic, once dominant north of the

In the late Middle Ages, early Scots, often simply called English, became the dominant language of the country. It was derived largely from Old English, with the addition of elements from Gaelic and French. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late fourteenth century onwards.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 60–7. It began to be adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French. By the fifteenth century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I onwards. As a result, Gaelic, once dominant north of the River Tay

The River Tay (, ; probably from the conjectured Brythonic ''Tausa'', possibly meaning 'silent one' or 'strong one' or, simply, 'flowing' David Ross, ''Scottish Place-names'', p. 209. Birlinn Ltd., Edinburgh, 2001.) is the longest river in Sc ...

, began a steady decline. Lowland writers began to treat Gaelic as a second class, rustic and even amusing language, helping to frame attitudes towards the highlands and to create a cultural gulf with the lowlands.

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour's '' Brus'' (1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of Robert I's actions before the English invasion until the end of the war of independence. The work was extremely popular among the Scots-speaking aristocracy and Barbour is referred to as the father of Scots poetry, holding a similar place to his contemporary Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He ...

in England. In the early fifteenth century these were followed by Andrew of Wyntoun's verse ''Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland'' and Blind Harry's '' The Wallace'', which blended historical romance

Historical romance is a broad category of mass-market fiction focusing on romantic relationships in historical periods, which Lord Byron, Byron helped popularize in the early 19th century. The genre often takes the form of the novel.

Varieties

...

with the verse chronicle. They were probably influenced by Scots versions of popular French romances that were also produced in the period, including '' The Buik of Alexander'', '' Launcelot o the Laik'' and ''The Porteous of Noblenes'' by Gilbert Hay.

Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court, which included James I (who wrote ''The Kingis Quair

''The Kingis Quair'' ("The King's Book") is a fifteenth-century Early Scots poem attributed to James I of Scotland. It is semi-autobiographical in nature, describing the King's capture by the English in 1406 on his way to France and his subsequ ...

''). Many of the makars had university education and so were also connected with the Kirk

Kirk is a Scottish and former Northern English word meaning 'church'. The term ''the Kirk'' is often used informally to refer specifically to the Church of Scotland, the Scottish national church that developed from the 16th-century Reformation ...

. However, Dunbar's '' Lament for the Makaris'' (c.1505) provides evidence of a wider tradition of secular writing outside of Court and Kirk now largely lost. Before the advent of printing in Scotland, writers such as Robert Henryson

Robert Henryson (Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the Scots language, Scots ''makars'', he lived in the royal burgh of Dunfermline and is a distinctive voice in th ...

, William Dunbar, Walter Kennedy and Gavin Douglas have been seen as leading a golden age in Scottish poetry.

In the late fifteenth century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. Although there are earlier fragments of original Scots prose, such as the ''Auchinleck Chronicle'', the first complete surviving work includes John Ireland's ''The Meroure of Wyssdome'' (1490). There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s, including ''The Book of the Law of Armys'' and the ''Order of Knychthode'' and the treatise '' Secreta Secretorum'', an Arabic work believed to be Aristotle's advice to Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

. The establishment of a printing press under royal patent in 1507 would begin to make it easier to disseminate Scottish literature and was probably aimed at bolstering Scottish national identity.P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, ''A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry'' (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), , pp. 26–9. The first Scottish press was established in Southgait in Edinburgh by the merchant Walter Chepman (c. 1473–c. 1528) and the bookseller Andrew Myllar (f. 1505–08). Although the first press was relatively short lived, beside law codes and religious works, the press also produced editions of the work of Scottish makars before its demise, probably about 1510. The next recorded press was that of Thomas Davidson (f. 1532–42), the first in a long line of "king's printers", who also produced editions of works of the makars.A. MacQuarrie, "Printing and publishing", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 491–3. The landmark work in the reign of James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

'', the '' Eneados'', which was the first complete translation of a major classical text in the Scots language and the first successful example of its kind in any Anglic language. It was finished in 1513, but overshadowed by the disaster at Flodden.

Early modern era

Sixteenth century

As a patron of poets and authorsJames V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV a ...

(r. 1513–42) supported William Stewart and John Bellenden

John Bellenden or Ballantyne ( 1533–1587?) of Moray (why Moray, a lowland family) was a Scottish writer of the 16th century.

Life

He was born towards the close of the 15th century, and educated at St. Andrews and Paris.

At the request of ...

, who translated the Latin ''History of Scotland'' compiled in 1527 by Hector Boece

Hector Boece (; also spelled Boyce or Boise; 1465–1536), known in Latin as Hector Boecius or Boethius, was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and the first Ancient university governance in Scotland, Principal of King's College, Aberdeen, ...

, into verse and prose. David Lyndsay (c. 1486–1555), diplomat and the head of the Lyon Court, was a prolific poet. He wrote elegiac narratives, romances and satires.T. van Heijnsbergen, "Culture: 9 Renaissance and Reformation: poetry to 1603", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 129–30. George Buchanan

George Buchanan (; February 1506 – 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth-century Scotland produced." His ideology of re ...

(1506–82) had a major influence as a Latin poet, founding a tradition of neo-Latin poetry that would continue in to the seventeenth century.R. Mason, "Culture: 4 Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1660): general", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 120–3. Contributors to this tradition included royal secretary John Maitland (1537–95), reformer Andrew Melville (1545–1622), John Johnston (1570?–1611) and David Hume of Godscroft (1558–1629).

From the 1550s, in the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

(r. 1542–67) and the minority of her son James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

(r. 1567–1625), cultural pursuits were limited by the lack of a royal court and by political turmoil. The Kirk, heavily influenced by Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

, also discouraged poetry that was not devotional in nature. Nevertheless, poets from this period included Richard Maitland

Sir Richard Maitland of Lethington and Thirlstane (1496 – 1 August 1586) was a Senator of the College of Justice, an Ordinary Lord of Session from 1561 until 1584, and notable Scottish poet. He was served heir to his father, Sir William Mai ...

of Lethington (1496–1586), who produced meditative and satirical verses in the style of Dunbar; John Rolland (fl. 1530–75), who wrote allegorical satires in the tradition of Douglas and courtier and minister Alexander Hume (c. 1556–1609), whose corpus of work includes nature poetry and epistolary verse. Alexander Scott's (?1520–82/3) use of short verse designed to be sung to music, opened the way for the Castilan poets of James VI's adult reign.

In the 1580s and 1590s James VI strongly promoted the literature of the country of his birth in Scots. His treatise, '' Some Rules and Cautions to be Observed and Eschewed in Scottish Prosody'', published in 1584 when he was aged 18, was both a poetic manual and a description of the poetic tradition in his mother tongue, to which he applied Renaissance principles. He became patron and member of a loose circle of Scottish Jacobean court poets and musicians, later called the Castalian Band, which included William Fowler (c. 1560–1612), John Stewart of Baldynneis (c. 1545–c. 1605), and Alexander Montgomerie

Alexander Montgomerie (Scottish Gaelic: Alasdair Mac Gumaraid) (c. 1550?–1598) was a Scottish Jacobean courtier and poet, or makar, born in Ayrshire. He was a Scottish Gaelic speaker and a Scots speaker from Ayrshire, an area which w ...

(c. 1550–98). They translated key Renaissance texts and produced poems using French forms, including sonnet

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

s and short sonnets, for narrative, nature description, satire and meditations on love. Later poets that followed in this vein included William Alexander (c. 1567–1640), Alexander Craig (c. 1567–1627) and Robert Ayton (1570–1627). By the late 1590s the king's championing of his native Scottish tradition was to some extent diffused by the prospect of inheriting of the English throne.

Lyndsay produced an interlude at Linlithgow Palace

The ruins of Linlithgow Palace are located in the town of Linlithgow, West Lothian, Scotland, west of Edinburgh. The palace was one of the principal residences of the monarchs of Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland in the 15th and 16th ce ...

for the king and queen thought to be a version of his play '' The Thrie Estaitis'' in 1540, which satirised the corruption of church and state, and which is the only complete play to survive from before the Reformation.I. Brown, T. Owen Clancy, M. Pittock, S. Manning, eds, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union, until 1707'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 256–7. Buchanan was major influence on Continental theatre with plays such as ''Jepheths'' and ''Baptistes'', which influenced Pierre Corneille

Pierre Corneille (; ; 6 June 1606 – 1 October 1684) was a French tragedian. He is generally considered one of the three great 17th-century French dramatists, along with Molière and Racine.

As a young man, he earned the valuable patronage ...

and Jean Racine

Jean-Baptiste Racine ( , ; ; 22 December 1639 – 21 April 1699) was a French dramatist, one of the three great playwrights of 17th-century France, along with Molière and Corneille, as well as an important literary figure in the Western tr ...

and through them the neo-classical tradition in French drama, but his impact in Scotland was limited by his choice of Latin as a medium.I. Brown, "Introduction: a lively tradition and collective amnesia", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), , pp. 1–3. The anonymous ''The Maner of the Cyring of ane Play'' (before 1568) and ''Philotus'' (published in London in 1603), are isolated examples of surviving plays. The latter is a vernacular Scots comedy of errors, probably designed for court performance for Mary, Queen of Scots or James VI.S. Carpenter, "Scottish drama until 1650", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), , p. 15. The same system of professional companies of players and theatres that developed in England in this period was absent in Scotland, but James VI signalled his interest in drama by arranging for a company of English players to erect a playhouse and perform in 1599.S. Carpenter, "Scottish drama until 1650", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), , p. 21.

Seventeenth century

Having extolled the virtues of Scots "poesie", following his accession to the English throne, James VI increasingly favoured the language of southern England. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the English

Having extolled the virtues of Scots "poesie", following his accession to the English throne, James VI increasingly favoured the language of southern England. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the English Authorised King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version (AV), is an Early Modern English Bible translations, Early Modern English translation of the Christianity, Christian Bible for the Church of England, wh ...

of the Bible. In 1617 interpreters were declared no longer necessary in the port of London because Scots and Englishmen were now "not so far different bot ane understandeth ane uther". Jenny Wormald, describes James as creating a "three-tier system, with Gaelic at the bottom and English at the top".J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 192–3. The loss of the court as a centre of patronage in 1603 was a major blow to Scottish literature. A number of Scottish poets, including William Alexander, John Murray and Robert Aytoun accompanied the king to London, where they continued to write,K. M. Brown, "Scottish identity", in B. Bradshaw and P. Roberts, eds, ''British Consciousness and Identity: The Making of Britain, 1533–1707'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), , pp. 253–3. but they soon began to anglicise their written language. James's characteristic role as active literary participant and patron in the English court made him a defining figure for English Renaissance poetry and drama, which would reach a pinnacle of achievement in his reign, but his patronage for the high style in his own Scottish tradition largely became sidelined. The only significant court poet to continue to work in Scotland after the king's departure was William Drummond of Hawthornden

William Drummond (13 December 15854 December 1649), called "of Hawthornden", was a Scottish poet.

Life

Drummond was born at Hawthornden Castle, Midlothian, to John Drummond, the first laird of Hawthornden, and Susannah Fowler, sister of the ...

(1585–1649).

As the tradition of classical Gaelic poetry declined, a new tradition of vernacular Gaelic poetry began to emerge. While Classical poetry used a language largely fixed in the twelfth century, the vernacular continued to develop. In contrast to the Classical tradition, which used syllabic metre, vernacular poets tended to use stressed metre. However, they shared with the Classic poets a set of complex metaphors and role, as the verse was still often panegyric. A number of these vernacular poets were women, such as Mary MacLeod of Harris (c. 1615–1707).J. MacDonald, "Gaelic literature" in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 255–7.

The tradition of neo-Latin poetry reached its fruition with the publication of the anthology of the ''Deliciae Poetarum Scotorum'' (1637), published in Amsterdam by Arthur Johnston (c. 1579–1641) and Sir John Scott of Scotstarvet (1585–1670) and containing work by the major Scottish practitioners since Buchanan. This period was marked by the work of the first named female Scottish poets.T. van Heijnsbergen, "Culture: 7 Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1660): literature", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 127–8. Elizabeth Melville

Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross (c.1578–c.1640) was a Scottish people, Scottish poet. In 1603 she became the earliest known Scottish woman writer to see her work in print, when the Edinburgh publisher Robert Charteris issued the first edition ...

's (f. 1585–1630) ''Ane Godlie Dream'' (1603) was a popular religious allegory and the first book published by a woman in Scotland. Anna Hume, daughter of David Hume of Godscroft, adapted Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

's ''Triumphs

''Triumphs'' ( Italian: ''I Trionfi'') is a 14th-century Italian series of poems, written by Petrarch in the Tuscan language. The poem evokes the Roman ceremony of triumph, where victorious generals and their armies were led in procession by the ...

'' as ''Triumphs of Love: Chastitie: Death'' (1644).

This was the period when the ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and song of Great Britain and Ireland from the Late Middle Ages until the 19th century. They were widely used across Eur ...

emerged as a significant written form in Scotland. Some ballads may date back to the late medieval era and deal with events and people that can be traced back as far as the thirteenth century, including " Sir Patrick Spens" and "Thomas the Rhymer

Sir Thomas de Ercildoun, better remembered as Thomas the Rhymer (fl. c. 1220 – 1298), also known as Thomas Learmont or True Thomas, was a Scottish laird and reputed prophet from Earlston (then called "Erceldoune") in the Borders. Tho ...

", but which are not known to have existed until the eighteenth century. They were probably composed and transmitted orally and only began to be written down and printed, often as broadsides and as part of chapbooks, later being recorded and noted in books by collectors including Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

and Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

. From the seventeenth century they were used as a literary form by aristocratic authors including Robert Sempill (c. 1595–c. 1665), Lady Elizabeth Wardlaw (1627–1727) and Lady Grizel Baillie

Lady Grizel Baillie (''Birth name, née'' Hume, 25 December 1665 – 6 December 1746) was a Scotland, Scottish gentlewoman and songwriter. Her accounting ledgers, in which she kept details about her household for more than 50 years, provide in ...

(1645–1746).

The loss of a royal court also meant there was no force to counter the kirk's dislike of theatre, which struggled to survive in Scotland. However, it was not entirely extinguished. The kirk used theatre for its own purposes in schools and was slow to suppress popular folk dramas. Surviving plays for the period include William Alexander's ''Monarchicke Tragedies'', written just before his departure with the king for England in 1603. They were closet drama

A closet drama is a play (theatre), play that is not intended to be performed onstage, but read by a solitary reader. The earliest use of the term recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary is in 1813. The literary historian Henry Augustin Beers, H ...

s, designed to be read rather than performed, and already indicate Alexander's preference for southern English over the Scots language. There were some attempts to revive Scottish drama. In 1663 Edinburgh lawyer William Clerke wrote ''Marciano or the Discovery'', a play about the restoration of a legitimate dynasty in Florence after many years of civil war. It was performed at the Tennis-Court Theatre at Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly known as Holyrood Palace, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinburgh Castle, Holyrood has s ...

before the parliamentary high commissioner John Leslie, Earl of Rothes. Thomas Sydsurf's ''Tarugo's Wiles or the Coffee House'', was first performed in London in 1667 and then in Edinburgh the year after and drew on Spanish comedy. A relative of Sydsurf, physician Archibald Pitcairne (1652–1713) wrote ''The Assembly or Scotch Reformation'' (1692), a ribald satire on the morals of the Presbyterian kirk, circulating in manuscript, but not published until 1722, helping to secure the association between Jacobitism

Jacobitism was a political ideology advocating the restoration of the senior line of the House of Stuart to the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British throne. When James II of England chose exile after the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, ...

and professional drama that discouraged the creation of professional theatre.I. Brown, "Public and private performance: 1650–1800", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), , pp. 28–30.

Eighteenth century

After the Union in 1707 and the shift of political power to England, the use of Scots was discouraged by many in authority and education. Nevertheless, Scots remained the vernacular of many rural communities and the growing number of urban working-class Scots. Literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) was the most important literary figure of the era, often described as leading a "vernacular revival". He laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, publishing ''The Ever Green'' (1724), a collection that included many major poetic works of the Stewart period. He led the trend for