Scottish Catholics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Catholic Church in Scotland, overseen by the Scottish Bishops' Conference, is part of the worldwide

Christianity may have been introduced to what is now Scotland by soldiers of the

Christianity may have been introduced to what is now Scotland by soldiers of the

During the reign of King Malcolm III, the Scottish church underwent a series of reforms and transformations. Through the influence of his Hungarian-born wife,

During the reign of King Malcolm III, the Scottish church underwent a series of reforms and transformations. Through the influence of his Hungarian-born wife,

Even so, the remaining domestic clergy played a relatively small role and the initiative was often left to lay leaders. Wherever Noblesse, noble families, local lairds, or

Even so, the remaining domestic clergy played a relatively small role and the initiative was often left to lay leaders. Wherever Noblesse, noble families, local lairds, or

Numbers probably reduced in the seventeenth century and organisation deteriorated.J. T. Koch, ''Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5'' (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), , pp. 416–7.

The Pope appointed Thomas Joseph Nicolson, Thomas Nicolson as the first Vicar Apostolic over the mission in 1694.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 365. The country was organised into districts and by 1703 there were thirty-three Catholic clergy. In 1733 it was divided into two vicariates, one for the Highland and one for the Lowland, each under a bishop. In the Highland District, which had largely been looked after by Ulster Irish-speaking missionary priests, a minor seminary was founded by Bishop James Gordon (vicar apostolic), James Gordon to train native-born priests at Eilean Bàn in

Numbers probably reduced in the seventeenth century and organisation deteriorated.J. T. Koch, ''Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5'' (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), , pp. 416–7.

The Pope appointed Thomas Joseph Nicolson, Thomas Nicolson as the first Vicar Apostolic over the mission in 1694.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 365. The country was organised into districts and by 1703 there were thirty-three Catholic clergy. In 1733 it was divided into two vicariates, one for the Highland and one for the Lowland, each under a bishop. In the Highland District, which had largely been looked after by Ulster Irish-speaking missionary priests, a minor seminary was founded by Bishop James Gordon (vicar apostolic), James Gordon to train native-born priests at Eilean Bàn in

From the 1980s the UK government passed several acts that had provisions concerning sectarian violence. These included the Public Order Act 1986, which introduced offences relating to the incitement of racial hatred, and the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, which introduced offences of pursuing a racially aggravated course of conduct that amounts to harassment of a person. The 1998 Act also required courts to take into account where offences are racially motivated, when determining sentence. In the twenty-first century the Scottish Parliament legislated against sectarianism. This included provision for religiously aggravated offences in the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003. The Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 strengthened statutory aggravations for both racially and religiously motivated hate crimes. The Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012, criminalised behaviour which is threatening, hateful, or otherwise offensive at a regulated football match including offensive singing or chanting. It also criminalised the communication of threats of serious violence and threats intended to incite religious hatred.

57% of the Catholic community belong to the manual working class, working-class.Gilfillan, P. (2015) Nation and culture in the renewal of Scottish Catholicism. Open House, 252, page 9: 'Professor David McCrone reported that 57% of Scotland's Catholics were manual working class, while only 48% of the general population were classified as working class.' Though structural disadvantage had largely eroded by the 1980s, Scottish Catholics are more likely to experience poverty and deprivation than their Protestant counterparts. Many more Catholics can now be found in what were called the professions, with some occupying posts in the judiciary or in national politics. In 1999, the Rt Hon John Reid, Baron Reid of Cardowan, John Reid MP became the first Catholic to hold the office of Secretary of State for Scotland. His succession by the Rt Hon Helen Liddell MP in 2001 attracted considerably more media comment that she was the first woman to hold the post than that she was the second Catholic. Also notable was the appointment of Louise Richardson to the University of St. Andrews as its principal and vice-chancellor. St Andrews is the third oldest university in the Anglosphere. Richardson, a Catholic, was born in Ireland and is a naturalised United States citizen. She is the first woman to hold that office and first Catholic to hold it since the Scottish Reformation.

The Catholic Church recognises the separate identities of Scotland and England and Wales. The church in Scotland is governed by its own hierarchy and bishops' conference, not under the control of English bishops. In more recent years, for example, there have been times when it was especially the Scottish bishops who took the floor in the United Kingdom to argue for Catholic social and moral teaching. The presidents of the bishops' conferences of England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland meet formally to discuss "mutual concerns", though they are separate national entities. "Closer cooperation between the presidents can only help the Church's work", a spokesman noted.

Scottish Catholics strongly supported the Scottish Labour, Labour Party in the past, and Labour politicians openly courted Catholic voters and accused their opponents such as the Scottish National Party of opposing the existence of Catholic schools. Scottish Catholics increasingly started identifying with Scottish nationalism in the 1970s and 1980s, and switched to the SNP as their preferred party. Scottish Catholics also emerged as a staunchly pro-independence group – according to a 2020 poll, 70% of Scottish Catholics supported Scottish independence. In 2013, Scottish sociologist Michael Rosie noted that "Catholics were actually the religious sub-group most likely to support an independent Scotland in 1999. This remains true in 2012."Gilfillan, P. (2015) Nation and culture in the renewal of Scottish Catholicism. Open House, 252, pp. 8-10. Scottish Catholics are also more likely to be in favour of Scottish independence and to support SNP than non-religious voters.

From the 1980s the UK government passed several acts that had provisions concerning sectarian violence. These included the Public Order Act 1986, which introduced offences relating to the incitement of racial hatred, and the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, which introduced offences of pursuing a racially aggravated course of conduct that amounts to harassment of a person. The 1998 Act also required courts to take into account where offences are racially motivated, when determining sentence. In the twenty-first century the Scottish Parliament legislated against sectarianism. This included provision for religiously aggravated offences in the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003. The Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 strengthened statutory aggravations for both racially and religiously motivated hate crimes. The Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012, criminalised behaviour which is threatening, hateful, or otherwise offensive at a regulated football match including offensive singing or chanting. It also criminalised the communication of threats of serious violence and threats intended to incite religious hatred.

57% of the Catholic community belong to the manual working class, working-class.Gilfillan, P. (2015) Nation and culture in the renewal of Scottish Catholicism. Open House, 252, page 9: 'Professor David McCrone reported that 57% of Scotland's Catholics were manual working class, while only 48% of the general population were classified as working class.' Though structural disadvantage had largely eroded by the 1980s, Scottish Catholics are more likely to experience poverty and deprivation than their Protestant counterparts. Many more Catholics can now be found in what were called the professions, with some occupying posts in the judiciary or in national politics. In 1999, the Rt Hon John Reid, Baron Reid of Cardowan, John Reid MP became the first Catholic to hold the office of Secretary of State for Scotland. His succession by the Rt Hon Helen Liddell MP in 2001 attracted considerably more media comment that she was the first woman to hold the post than that she was the second Catholic. Also notable was the appointment of Louise Richardson to the University of St. Andrews as its principal and vice-chancellor. St Andrews is the third oldest university in the Anglosphere. Richardson, a Catholic, was born in Ireland and is a naturalised United States citizen. She is the first woman to hold that office and first Catholic to hold it since the Scottish Reformation.

The Catholic Church recognises the separate identities of Scotland and England and Wales. The church in Scotland is governed by its own hierarchy and bishops' conference, not under the control of English bishops. In more recent years, for example, there have been times when it was especially the Scottish bishops who took the floor in the United Kingdom to argue for Catholic social and moral teaching. The presidents of the bishops' conferences of England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland meet formally to discuss "mutual concerns", though they are separate national entities. "Closer cooperation between the presidents can only help the Church's work", a spokesman noted.

Scottish Catholics strongly supported the Scottish Labour, Labour Party in the past, and Labour politicians openly courted Catholic voters and accused their opponents such as the Scottish National Party of opposing the existence of Catholic schools. Scottish Catholics increasingly started identifying with Scottish nationalism in the 1970s and 1980s, and switched to the SNP as their preferred party. Scottish Catholics also emerged as a staunchly pro-independence group – according to a 2020 poll, 70% of Scottish Catholics supported Scottish independence. In 2013, Scottish sociologist Michael Rosie noted that "Catholics were actually the religious sub-group most likely to support an independent Scotland in 1999. This remains true in 2012."Gilfillan, P. (2015) Nation and culture in the renewal of Scottish Catholicism. Open House, 252, pp. 8-10. Scottish Catholics are also more likely to be in favour of Scottish independence and to support SNP than non-religious voters.

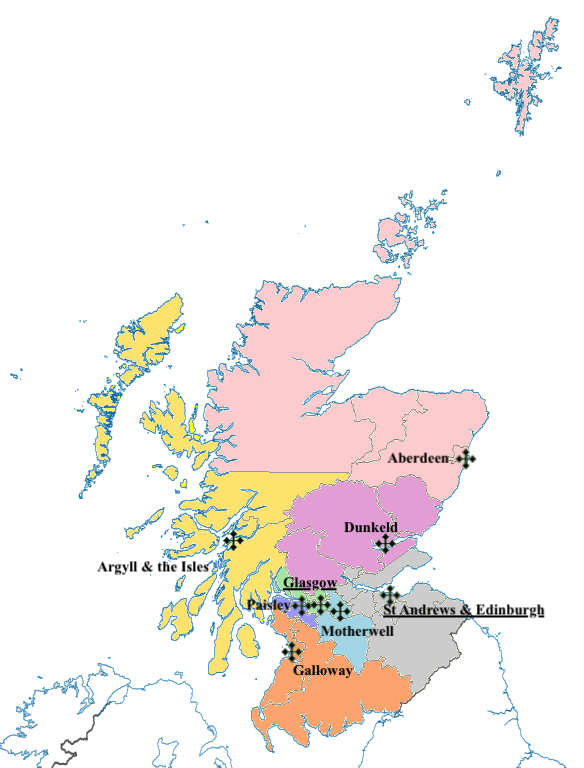

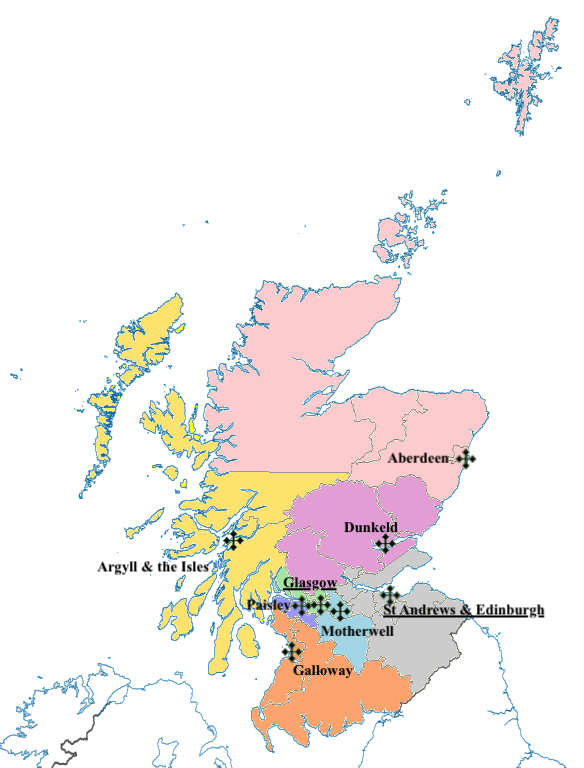

There are four entities that encompass Scotland, England, and Wales.

* The Military Ordinariate for Great-Britain, Bishopric of the Forces serves all members of the British Armed Forces throughout the world, including those stationed on bases in Scotland.

* The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham is a jurisdiction equivalent to a diocese for former Anglicans received into full communion with the Catholic Church. It has faculty to celebrate a distinct variant of the Roman Rite based on both the Tridentine Mass and the Sarum Rite, but with a dialect of Elizabethan English, based on the Book of Common Prayer, being used as their

There are four entities that encompass Scotland, England, and Wales.

* The Military Ordinariate for Great-Britain, Bishopric of the Forces serves all members of the British Armed Forces throughout the world, including those stationed on bases in Scotland.

* The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham is a jurisdiction equivalent to a diocese for former Anglicans received into full communion with the Catholic Church. It has faculty to celebrate a distinct variant of the Roman Rite based on both the Tridentine Mass and the Sarum Rite, but with a dialect of Elizabethan English, based on the Book of Common Prayer, being used as their

Between 1982 and 2010, the proportion of Scottish Catholics dropped 18%, baptisms dropped 39%, and Catholic church marriages dropped 63%. The number of priests also dropped. Between the 2001 United Kingdom census, 2001 UK Census and the 2011 United Kingdom census, 2011 UK Census, the proportion of Catholics remained steady while that of other Christians denominations, notably the Church of Scotland dropped.

In 2001, Catholics were a minority in each of Scotland's 32 council areas but in a few parts of the country their numbers were close to those of the official Church of Scotland. The most Catholic part of the country is composed of the western Central Belt council areas near Glasgow. In Inverclyde, 38.3% of persons responding to the 2001 UK Census reported themselves to be Catholic compared to 40.9% as adherents of the Church of Scotland. North Lanarkshire also already had a large Catholic minority at 36.8% compared to 40.0% in the Church of Scotland. Following in order were West Dunbartonshire (35.8%), Glasgow City Council, Glasgow City (31.7%), Renfrewshire (24.6%), East Dunbartonshire (23.6%), South Lanarkshire (23.6%) and East Renfrewshire (21.7%).

In 2011, Catholics outnumbered adherents of the Church of Scotland in several council areas, including North Lanarkshire, Inverclyde, West Dunbartonshire, and the most populous one: Glasgow City.

Between the two censuses, numbers in Glasgow with no religion rose significantly while those noting their affiliation to the Church of Scotland dropped significantly so that the latter fell below those that identified with an affiliation to the Catholic Church.

At a smaller geographic scale, one finds that the two most Catholic parts of Scotland are: (1) the southernmost islands of the Western Isles, especially Barra and South Uist, populated by Gaelic-speaking Scots of long-standing; and (2) the eastern suburbs of Glasgow, especially around Coatbridge, populated mostly by the descendants of Irish Catholic immigrants.

According to the 2011 UK Census, Catholics comprise 16% of the overall population, making it the second-largest church after the Church of Scotland (32%).

Along ethnic or racial lines, Scottish Catholicism was in the past, and has remained at present, predominantly White or light-skinned in membership, as have always been other branches of Christianity in Scotland. Among respondents in the 2011 UK Census who identified as Catholic, 81% are White Scots, 17% are Other White (mostly other British or Irish), 1% is either Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British, and an additional 1% is either mixed-race or from multiple ethnicities; African; Caribbean or black; or from other ethnic groups.

In recent years the Catholic Church in Scotland has experienced negative publicity in the mainstream media due to statements made by bishops in defence of traditional

Between 1982 and 2010, the proportion of Scottish Catholics dropped 18%, baptisms dropped 39%, and Catholic church marriages dropped 63%. The number of priests also dropped. Between the 2001 United Kingdom census, 2001 UK Census and the 2011 United Kingdom census, 2011 UK Census, the proportion of Catholics remained steady while that of other Christians denominations, notably the Church of Scotland dropped.

In 2001, Catholics were a minority in each of Scotland's 32 council areas but in a few parts of the country their numbers were close to those of the official Church of Scotland. The most Catholic part of the country is composed of the western Central Belt council areas near Glasgow. In Inverclyde, 38.3% of persons responding to the 2001 UK Census reported themselves to be Catholic compared to 40.9% as adherents of the Church of Scotland. North Lanarkshire also already had a large Catholic minority at 36.8% compared to 40.0% in the Church of Scotland. Following in order were West Dunbartonshire (35.8%), Glasgow City Council, Glasgow City (31.7%), Renfrewshire (24.6%), East Dunbartonshire (23.6%), South Lanarkshire (23.6%) and East Renfrewshire (21.7%).

In 2011, Catholics outnumbered adherents of the Church of Scotland in several council areas, including North Lanarkshire, Inverclyde, West Dunbartonshire, and the most populous one: Glasgow City.

Between the two censuses, numbers in Glasgow with no religion rose significantly while those noting their affiliation to the Church of Scotland dropped significantly so that the latter fell below those that identified with an affiliation to the Catholic Church.

At a smaller geographic scale, one finds that the two most Catholic parts of Scotland are: (1) the southernmost islands of the Western Isles, especially Barra and South Uist, populated by Gaelic-speaking Scots of long-standing; and (2) the eastern suburbs of Glasgow, especially around Coatbridge, populated mostly by the descendants of Irish Catholic immigrants.

According to the 2011 UK Census, Catholics comprise 16% of the overall population, making it the second-largest church after the Church of Scotland (32%).

Along ethnic or racial lines, Scottish Catholicism was in the past, and has remained at present, predominantly White or light-skinned in membership, as have always been other branches of Christianity in Scotland. Among respondents in the 2011 UK Census who identified as Catholic, 81% are White Scots, 17% are Other White (mostly other British or Irish), 1% is either Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British, and an additional 1% is either mixed-race or from multiple ethnicities; African; Caribbean or black; or from other ethnic groups.

In recent years the Catholic Church in Scotland has experienced negative publicity in the mainstream media due to statements made by bishops in defence of traditional

Bishops' Conference of ScotlandFacts about Catholics in ScotlandScottish Catholic ObserverNational Library of Scotland: SCOTTISH SCREEN ARCHIVE

(selection of archive films relating to Catholicism in Scotland) {{DEFAULTSORT:Catholic Church in Scotland Catholic Church in Scotland, Catholic Church by country, Scotland

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

headed by the Pope. Christianity first arrived in Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman province of ''Britannia'' after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

Julius Caes ...

and was strengthened by the conversion of the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

through both the Hiberno-Scottish mission

The Hiberno-Scottish mission was a series of expeditions in the 6th and 7th centuries by Gaels, Gaelic Missionary, missionaries originating from Ireland that spread Celtic Christianity in Scotland, Wales, History of Anglo-Saxon England, England a ...

and Iona Abbey

Iona Abbey is an abbey located on the island of Iona, just off the Isle of Mull on the West Coast of Scotland.

It is one of the oldest History of early Christianity, Christian religious centres in Western Europe. The abbey was a focal point ...

. After being firmly established in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

for nearly a millennium and contributing enormously to Scottish literature

Scottish literature is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers. It includes works in English, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, Brythonic, French, Latin, Norn or other languages written within the modern boundaries of Scotland.

The e ...

and culture, the Catholic Church was outlawed by the Scottish Reformation Parliament

The Scottish Reformation Parliament was the assembly elected in 1560 that passed legislation leading to the establishment of the Church of Scotland. These included the Confession of Faith Ratification Act 1560; and Papal Jurisdiction Act 1560. The ...

in 1560. Multiple uprisings in the interim failed to reestablish Catholicism or to legalise its existence. Even today, the Papal Jurisdiction Act 1560

The Papal Jurisdiction Act 1560 (c. 2) is an Act of the Parliament of Scotland which is still in force. It declares that the Pope has no jurisdiction in Scotland and prohibits any person from seeking any title or right to be exercised in Scotlan ...

, while no longer enforced, still remains on the books.

Throughout the nearly three centuries of religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic oppression of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religion, religious beliefs or affiliations or their irreligion, lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within socie ...

and disenfranchisement

Disfranchisement, also disenfranchisement (which has become more common since 1982) or voter disqualification, is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing someo ...

between 1560 and 1829, many students for the priesthood went abroad to study while others remained in Scotland and, in what is now termed underground education

Underground education or clandestine education refers to various practices of teaching carried out at times and places where such educational activities were deemed illegal.

Examples of places where widespread clandestine education practices took ...

, attended illegal seminaries. An early seminary upon Eilean Bàn in Loch Morar

Loch Morar () is a freshwater loch in the Rough Bounds of Lochaber, Highland (council area), Highland, Scotland. It is the fifth-largest loch by surface area in Scotland, at , and the deepest freshwater body in the British Isles with a maximum ...

was moved during the Jacobite rising of 1715

The Jacobite rising of 1715 ( ;

or 'the Fifteen') was the attempt by James Francis Edward Stuart, James Edward Stuart (the Old Pretender) to regain the thrones of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland ...

and reopened as Scalan seminary

The Scalan was a Scottish Catholic seminary and one of the few places where underground education by the Catholic Church in Scotland was kept alive during the anti-Catholic persecutions of the 16th-19th century.

History

The island in Loch Mo ...

in Glenlivet

Glenlivet () is a glen in the Highlands of Scotland through which the River Livet flows.

The river rises high in the Ladder Hills and flows past several distileries and hamlets and then onto the Bridgend before joining the River Avon, one of ...

. After multiple arson

Arson is the act of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, watercr ...

attacks by government troops, Scalan was rebuilt in the 1760s by Bishop John Geddes, who later became Vicar Apostolic of the Lowland District, a close friend of national poet

A national poet or national bard is a poet held by tradition and popular acclaim to represent the identity, beliefs and principles of a particular national culture. The national poet as culture hero is a long-standing symbol, to be distinguished ...

Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

, and a well-known figure in the Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

during the Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment (, ) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century, Scotland had a network of parish schools in the Sco ...

.

The successful campaign that resulted in Catholic emancipation in 1829 helped Catholics regain both freedom of religion and civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

. In 1878, the Catholic hierarchy was formally restored. As the Church was slowly rebuilding its presence in the Gàidhealtachd

The (; English: ''Gaeldom'') usually refers to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and especially the Scottish Gaelic-speaking culture of the area. The similar Irish language word refers, however, solely to Irish-speaking areas.

The ter ...

, the bishop

A bishop is a Christian cleric of authority.

Bishop, Bishops, Bishop's, or The Bishop may also refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Bishop Peak (Antarctica)

* Mount Bishop (Antarctica)

Australia

* Bishop Island (Queensland), an island

Canada

* Bisho ...

and priests of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Argyll and the Isles

The Diocese of Argyll and the Isles () is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Scotland, in the Province of Saint Andrews and Edinburgh.

Overview

The diocese covers an area of 31,080 km² and has a C ...

, inspired by the Irish Land War

The Land War () was a period of agrarian agitation in rural History of Ireland (1801–1923), Ireland (then wholly part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom) that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the firs ...

, became the ringleaders of a direct action

Direct action is a term for economic and political behavior in which participants use agency—for example economic or physical power—to achieve their goals. The aim of direct action is to either obstruct a certain practice (such as a governm ...

resistance campaign by their parishioners to the Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances ( , the "eviction of the Gaels") were the evictions of a significant number of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands, mostly in two phases from 1750 to 1860.

The first phase resulted from Scottish Agricultural R ...

, rackrenting Rack-rent denotes two different concepts:

# an excessive rent.

# the full rent of a property, including both land and improvements as if it were subject to an immediate open-market rental review.

The second definition is equivalent to the economi ...

, religious discrimination

Religious discrimination is treating a person or group differently because of the particular religion they align with or were born into. This includes instances when adherents of different religions, denominations or non-religions are treate ...

, and other acts widely seen as abuses of power by Anglo-Scottish

Anglo is a prefix indicating a relation to, or descent from England, English culture, the English people or the English language, such as in the term ''Anglosphere''. It is often used alone, somewhat loosely, to refer to people of British de ...

landlords and their estate factors.

Many Scottish Roman Catholics in the heavily populated Lowlands are the descendants of Irish immigrants

The Irish diaspora () refers to ethnic Irish people and their descendants who live outside the island of Ireland.

The phenomenon of migration from Ireland is recorded since the Early Middle Ages,Flechner, Roy; Meeder, Sven (2017). The Irish ...

and of Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

-speaking migrants from the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland, and the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).

The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act o ...

who both moved into Scotland's cities and industrial towns during the 19th century, especially during the Highland Clearances, the Highland Potato Famine

The Highland Potato Famine () was a period of 19th-century Scottish Highland history (1846 to roughly 1856) over which the agricultural communities of the Hebrides and the western Scottish Highlands () saw their potato crop (upon which they ha ...

, and the similar famine in Ireland. However, there are also significant numbers of Scottish Catholics of Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

, Lithuanian

Lithuanian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Lithuania, a country in the Baltic region in northern Europe

** Lithuanian language

** Lithuanians, a Baltic ethnic group, native to Lithuania and the immediate geographical region

** L ...

, Ukrainian, and Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

descent, with more recent immigrants again boosting the numbers. Owing to immigration (overwhelmingly white European

European, or Europeans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe and other West ...

), it is estimated that, in 2009, there were about 850,000 Catholics in the country of 5.1 million.

The Gàidhealtachd

The (; English: ''Gaeldom'') usually refers to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and especially the Scottish Gaelic-speaking culture of the area. The similar Irish language word refers, however, solely to Irish-speaking areas.

The ter ...

has been both Catholic and Protestant in modern times. A number of Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

-speaking areas, including Barra

Barra (; or ; ) is an island in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland, and the second southernmost inhabited island there, after the adjacent island of Vatersay to which it is connected by the Vatersay Causeway.

In 2011, the population was 1,174. ...

, Benbecula

Benbecula ( ; or ) is an island of the Outer Hebrides in the Atlantic Ocean off the west coast of Scotland. In the 2011 census, it had a resident population of 1,283 with a sizable percentage of Roman Catholics. It is in a zone administered by ...

, South Uist

South Uist (, ; ) is the second-largest island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. At the 2011 census, it had a usually resident population of 1,754: a decrease of 64 since 2001. The island, in common with the rest of the Hebrides, is one of the ...

, Eriskay

Eriskay (), from the Old Norse for "Eric's Isle", is an island and community council area of the Outer Hebrides in northern Scotland with a population of 143, as of the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 census. It lies between South Uist and Bar ...

, and Moidart

Moidart ( ; ) is part of the remote and isolated area of Scotland, west of Fort William, Highland, Fort William, known as the Rough Bounds. Moidart itself is almost surrounded by bodies of water. Loch Shiel cuts off the eastern boundary of the ...

, are mainly Catholic. For this reason, Catholicism has had a very heavy influence upon Post-Reformation Scottish Gaelic literature

Scottish Gaelic literature refers to literary works composed in the Scottish Gaelic language, which is, like Irish and Manx, a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic languages. Gaelic literature was also composed in Gàidhealtachd communities ...

and the recent Scottish Gaelic Renaissance

The Scottish Gaelic Renaissance () is a continuing movement concerning the revival of the Scottish Gaelic language and its literature. Although the Scottish Gaelic language had been facing gradual decline in the number of speakers since the late ...

; particularly through Iain Lom, Sìleas na Ceapaich

Sìleas na Ceapaich (also known as Cicely Macdonald of Keppoch, Silis of Keppoch, Sìleas MacDonnell or Sìleas Nic Dhòmhnail na Ceapaich) was a Scottish poet whose surviving verses remain an immortal contribution to Scottish Gaelic literature ...

, Alasdair Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair

Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair (c. 1698–1770), legal name Alexander MacDonald, or, in Gaelic Alasdair MacDhòmhnaill, was a Scottish war poet, satirist, lexicographer, and memoirist.

He was born at Dalilea into the Noblesse, Scottish nobili ...

, Allan MacDonald

Allan Macdonald (November 21, 1794 White Plains, Westchester County, New York – January 1862) was an American politician from New York.

Life

He was the son of Dr. Archibald Macdonald (d. 1813), a native of Scotland.

Allan Macdonald was Postm ...

, Ailean a' Ridse MacDhòmhnaill

Allan The Ridge MacDonald (1794 Allt an t-Srathain, Lochaber, Scotland – 1 April 1868 Antigonish County, Nova Scotia, Canada) was a bard, traditional singer, and '' seanchaidh'' who emigrated from the Gàidhealtachd of Scotland to Nova Scotia in ...

, John Lorne Campbell

John Lorne Campbell FRSE LLD OBE () (1 October 1906 – 25 April 1996) was a Scotland, Scottish historian, farmer, environmentalist and folklorist, and recognized literary scholar, scholar of both Celtic studies and Scottish Gaelic literature. Al ...

, Margaret Fay Shaw

Margaret Fay Shaw (9 November 1903 – 11 December 2004) was a pioneering Scottish-American ethnomusicologist, photographer, folklorist, and scholar of Celtic studies. She is best known for her meticulous work as a folk song and folklore collect ...

, Dòmhnall Iain Dhonnchaidh

Donald John MacDonald, () (lit. "Donald Ian Duncan", fig. "Donald Ian, son of Duncan") legally Dòmhnaill Iain MacDhòmhnaill (7 February 1919 in Peninerine, South Uist, Scotland – 2 October 1986 in Glasgow, Scotland) was a Scottish people, Scott ...

, and Angus Peter Campbell

Angus Peter Campbell (; born 1952) is a Scottish award-winning poet, novelist, journalist, broadcaster and actor. Campbell's works, which are written mainly in Scottish Gaelic, draw heavily upon both Hebridean mythology and folklore and the ma ...

.

In the 2011 census, 16% of the population of Scotland

Population is a set of humans or other organisms in a given region or area. Governments conduct a census to quantify the resident population size within a given jurisdiction. The term is also applied to non-human animals, microorganisms, and pl ...

described themselves as being Catholic, compared with 32% affiliated with the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

. Between 1994 and 2002, Catholic attendance in Scotland declined 19% to just over 200,000. By 2008, the Catholic Bishops' Conference of Scotland estimated that 184,283 attended Mass regularly. Mass attendance has not recovered to the numbers prior to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

, though there was a dramatic rise between 2022 and 2023.

History

Establishment

Christianity may have been introduced to what is now Scotland by soldiers of the

Christianity may have been introduced to what is now Scotland by soldiers of the Roman Legions

The Roman legion (, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of Roman citizens serving as legionaries. During the Roman Republic the manipular legion comprised 4,200 infantry and 300 cavalry. After the Marian reforms in 1 ...

stationed in the far north of the province of Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

. Even after the 383 withdrawal of the Roman garrisons by Magnus Maximus

Magnus Maximus (; died 28 August 388) was Roman emperor in the West from 383 to 388. He usurped the throne from emperor Gratian.

Born in Gallaecia, he served as an officer in Britain under Theodosius the Elder during the Great Conspiracy ...

, it is well documented in sources about Saint Mungo

Kentigern (; ), known as Mungo, was a missionary in the Brittonic Kingdom of Strathclyde in the late sixth century, and the founder and patron saint of the city of Glasgow.

Name

In Wales and England, this saint is known by his birth and baptis ...

, St Ninian

Ninian is a Christian saint, first mentioned in the 8th century as being an early missionary among the Pictish peoples of what is now Scotland. For this reason, he is known as the Apostle to the Southern Picts, and there are numerous dedicatio ...

, and in locally composed works of early Welsh-language literature

Welsh-language literature () has been produced continuously since the emergence of Welsh from Brythonic as a distinct language in around the 5th century AD. The earliest Welsh literature was poetry, which was extremely intricate in form from ...

, like ''Y Gododdin

''Y Gododdin'' () is a medieval Welsh poem consisting of a series of elegies to the men of the Brittonic kingdom of Gododdin and its allies who, according to the conventional interpretation, died fighting the Angles of Deira and Bernicia ...

'', the ''Book of Taliesin

The Book of Taliesin () is one of the most famous of Middle Welsh manuscripts, dating from the first half of the 14th century though many of the fifty-six poems it preserves are taken to originate in the 10th century or before.

The volume cont ...

'', and the ''Book of Aneirin

The Book of Aneirin () is a late 13th century Welsh manuscript containing Old and Middle Welsh poetry attributed to the late 6th century Northern Brythonic poet, Aneirin, who is believed to have lived in present-day Scotland.

The manuscript is ...

'', that Christianity survived among the Proto-Welsh-speaking kingdoms in Scotland, which are still referred to in Modern Welsh

The history of the Welsh language () spans over 1400 years, encompassing the stages of the language known as Primitive Welsh, Old Welsh, Middle Welsh, and Modern Welsh.

Origins

Welsh evolved from British (Common Brittonic), the Celtic languag ...

as the Hen Ogledd

Hen Ogledd (), meaning the Old North, is the historical region that was inhabited by the Celtic Britons, Brittonic people of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages, now Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands, alongside the fello ...

(lit. "the Old North"). Like it's faithful, however, Christianity was slowly driven westward with refugee

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

s from the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain

The settlement of Great Britain by Germanic peoples from continental Europe led to the development of an Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon cultural identity and a shared Germanic language—Old English—whose closest known relative is Old Frisian, s ...

. The Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

, Anglo-Saxons, and Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ; ; ) are an Insular Celts, Insular Celtic ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. They are associated with the Goidelic languages, Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languages comprising ...

of modern Scotland, who were traditionally tribal peoples, were mainly evangelized and converted between the fifth and seventh centuries by Irish missionaries such as Sts Columba

Columba () or Colmcille (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is today Scotland at the start of the Hiberno-Scottish mission. He founded the important abbey ...

and Baithéne, the founders and first two abbots of Iona Abbey

Iona Abbey is an abbey located on the island of Iona, just off the Isle of Mull on the West Coast of Scotland.

It is one of the oldest History of early Christianity, Christian religious centres in Western Europe. The abbey was a focal point ...

, St Donnán of Eigg

Eigg ( ; ) is one of the Small Isles in the Scotland, Scottish Inner Hebrides. It lies to the south of the island of Isle of Skye, Skye and to the north of the Ardnamurchan peninsula. Eigg is long from north to south, and east to west. With ...

, and St Máel Ruba

Máel Ruba ( 642–722) is an Irish saint of the Celtic Church who was active in the Christianisation of the Picts and Gaels of Scotland. Originally a monk from Bangor Abbey, County Down, Gaelic Ireland, he founded the monastic community of A ...

, a monk from Bangor Abbey

Bangor Abbey was established by Saint Comgall in 558 in Bangor, County Down, Northern Ireland and was famous for its learning and austere rule. It is not to be confused with the slightly older abbey in Wales on the site of Bangor Cathedral.

Hi ...

who became the founder of Applecross

Applecross ( , 'The Sanctuary', historically anglicized as 'Combrich') is a peninsula in Wester Ross, in the Scottish Highlands. It is bounded by Loch Kishorn to the south, Loch Torridon to the north, and Glen Shieldaig to the east. On its wes ...

Abbey in Wester Ross

Wester Ross () is an area of the Northwest Highlands of Scotland in the council area of Highland. The area is loosely defined, and has never been used as a formal administrative region in its own right, but is generally regarded as lying to th ...

. These missionaries tended to found monastic

Monasticism (; ), also called monachism or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual activities. Monastic life plays an important role in many Christian churches, especially ...

institutions, which expanded to include schools, libraries, and collegiate churches whose priests both evangelized and served large areas. Partly as a result of these factors, some scholars have identified a distinctive Celtic Church

Celtic Christianity is a form of Christianity that was common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages. The term Celtic Church is deprecated by many historians as it implies a unified and identifiab ...

, to which Catholics, Protestants, Miaphysite

Miaphysitism () is the Christological doctrine that holds Jesus, the Incarnate Word, is fully divine and fully human, in one nature (''physis'', ). It is a position held by the Oriental Orthodox Churches. It differs from the Dyophysitism of the ...

Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

, and Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

, have all claimed in historical debates to be the only legitimate heirs. In the Celtic Church, attitudes towards clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because thes ...

were more relaxed, a differing form of monastic tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

was used, the use of prayer beads known as the Pater Noster cord

The Pater Noster cord (also spelled Paternoster Cord and called Paternoster beads) is a set of Christian prayer beads used to recite the 150 Psalms, as well as the Lord's Prayer. As such, Paternoster cords traditionally consist of 150 beads that ...

as a means of "prayer without ceasing" preceded the invention of the rosary

The Rosary (; , in the sense of "crown of roses" or "garland of roses"), formally known as the Psalter of Jesus and Mary (Latin: Psalterium Jesu et Mariae), also known as the Dominican Rosary (as distinct from other forms of rosary such as the ...

by St Dominic

Saint Dominic, (; 8 August 1170 – 6 August 1221), also known as Dominic de Guzmán (), was a Castilian Catholic priest and the founder of the Dominican Order. He is the patron saint of astronomers and natural scientists, and he and his orde ...

, and the lunar method was used for calculating the date of Easter. During the 1960s, Frank O'Connor

Frank O'Connor (born Michael Francis O'Donovan; 17 September 1903 – 10 March 1966) was an Irish author and translator. He wrote poetry (original and translations from Irish), dramatic works, memoirs, journalistic columns and features on as ...

explained that the reason why, on both sides of the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea is a body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland in the north by the North Ch ...

, abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from ''abba'', the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ''ab'', and means "father". The female equivale ...

s were often more significant than bishops is because a Church governed by an Episcopal polity

An episcopal polity is a hierarchical form of church governance in which the chief local authorities are called bishops. The word "bishop" here is derived via the British Latin and Vulgar Latin term ''*ebiscopus''/''*biscopus'', . It is the ...

, "in a tribal society was a contradiction in terms. No tribe, however small or weak, would accept the authority of a bishop from another tribe; but with a monastic organisation, each tribe could have its own monastery, and the larger ones could have as many as they wished."

Also, despite a shared belief in the Real Presence

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, sometimes shortened Real Presence'','' is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

Th ...

in the Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

, the veneration of the Blessed Virgin

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

, and shared use of the Ecclesiastical Latin

Ecclesiastical Latin, also called Church Latin or Liturgical Latin, is a form of Latin developed to discuss Christian theology, Christian thought in Late antiquity and used in Christianity, Christian liturgy, theology, and church administration ...

liturgical language

A sacred language, liturgical language or holy language is a language that is cultivated and used primarily for religious reasons (like church service) by people who speak another, primary language in their daily lives.

Some religions, or part ...

, as is documented by primary source

In the study of history as an academic discipline, a primary source (also called an original source) is an Artifact (archaeology), artifact, document, diary, manuscript, autobiography, recording, or any other source of information that was cre ...

s such as the Stowe Missal

The Stowe Missal (sometimes known as the Lorrha Missal), which is, strictly speaking, a sacramentary rather than a missal, is a small Irish illuminated manuscript written mainly in Latin with some Old Irish in the late eighth or early ninth centu ...

, there were often significant differences between the Celtic Rite

The term "Celtic Rite" is applied to the various liturgical rites used in Celtic Christianity in Britain, Ireland and Brittany and the monasteries founded by St. Columbanus and Saint Catald in France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy during the ...

and the mainstream Roman Rite

The Roman Rite () is the most common ritual family for performing the ecclesiastical services of the Latin Church, the largest of the ''sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. The Roman Rite governs Rite (Christianity) ...

C. Evans, "The Celtic Church in Anglo-Saxon times", in J. D. Woods, D. A. E. Pelteret, ''The Anglo-Saxons, synthesis and achievement'' (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1985), , pp. 77–89. and evidence of a distinctive form of Celtic chant

Celtic chant is the liturgical plainchant repertory of the Celtic rite of the Catholic Church performed in Celtic Britain, Gaelic Ireland, and Brittany. It is related to, but distinct from the Gregorian chant of the Sarum use of the Roman rite whic ...

in Latin, which is most closely related to Gallican chant

Gallican chant refers to the liturgical plainchant repertory of the Gallican rite of the Roman Catholic Church in Gaul, prior to the introduction and development of elements of the Roman rite from which Gregorian chant evolved. Although the music ...

, also survives in liturgical music manuscripts dating from the period. The Culdees

The Culdees (; ) were members of ascetic Christian monastic and eremitical communities of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England in the Middle Ages. Appearing first in Ireland and then in Scotland, subsequently attached to cathedral or collegiate ...

, an eremitical

A hermit, also known as an eremite (adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a Chr ...

order from Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland () was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late Prehistory of Ireland, prehistoric era until the 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Norman invasi ...

, also spread to Scotland, where their presence continued at least into the 11th-century. In his life of Saint Margaret of Scotland

Saint Margaret of Scotland (; , ), also known as Margaret of Wessex, was Queen of Alba from 1070 to 1093 as the wife of King Malcolm III. Margaret was sometimes called "The Pearl of Scotland". She was a member of the House of Wessex and was b ...

, Turgot of Durham

Thorgaut or Turgot (c. 1050–1115) (sometimes, Thurgot) was Archdeacon and Prior of Durham, and Bishop of Saint Andrews.

Biography

Early life and prior at Durham

Turgot came from the Lindsey in Lincolnshire. After the Norman Conquest he w ...

, Bishop of St Andrews

The Bishop of St. Andrews (, ) was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews (), the Archdiocese of St Andrews.

The name St Andrews is not the town or ...

, wrote of the Culdees, "At that time in the Kingdom of the Scots there were many living, shut up in cells in places set apart, by a life of great strictness, in the flesh but not according to the flesh, communing, indeed, with angels upon earth."

At the same time, the erenagh

The medieval Irish office of erenagh (Old Irish: ''airchinnech'', Modern Irish: ''airchinneach'', Latin: '' princeps'') was responsible for receiving parish revenue from tithes and rents, building and maintaining church property and overseeing t ...

system in Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland () was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late Prehistory of Ireland, prehistoric era until the 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Norman invasi ...

of hereditary lay administration of Church lands by family branches deliberately appointed from within the derbhfine

The derbfine ( ; , from 'real' + 'group of persons of the same family or kindred', thus literally 'true kin'electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language s.vderbḟine/ref>) was a term for patrilineal groups and power structures defined in the fi ...

of local Irish clan chiefs led to notorious abuses; like monasteries warring against each other and the infamous Irish "royal-abbot" of Cork and Clonfert Abbeys, Fedelmid mac Crimthainn

Fedelmid mac Crimthainn was the Kings of Munster, King of Munster between 820 and 846. He was numbered as a member of the Culdee, Céli Dé, an abbot of Cork Abbey and Clonfert, Clonfert Abbey, and possibly a bishop. After his death, he was late ...

, who personally led armies into battle against other Irish clan

Irish clans are traditional kinship groups sharing a common surname and heritage and existing in a lineage-based society, originating prior to the 17th century. A clan (or in Irish, plural ) included the chief and his patrilineal relatives; howe ...

s and abbeys and routinely sacked and burned other monasteries. Due to the close ties between the Church in both countries, the erenagh system also spread to Gaelic Scotland, with at least some similar results. For example, during the 11th-century reign of the Scottish High King Macbeth

''The Tragedy of Macbeth'', often shortened to ''Macbeth'' (), is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, estimated to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the physically violent and damaging psychological effects of political ambiti ...

, which was later fictionalized by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, the High King's greatest domestic foe by far proved to be his own uncle, Crínán of Dunkeld

Crínán of Dunkeld, also called Crinan the Thane (c. 975–1045), was the erenagh, or hereditary lay-abbot, of Dunkeld Abbey and, similarly to Irish "royal- and warrior-abbots" of the same period like the infamous case of Fedelmid mac Crimthai ...

, the warrior-abbot of Dunkeld Abbey, Mormaer of Atholl

In early medieval Scotland, a mormaer was the Gaelic name for a regional or provincial ruler, theoretically second only to the King of Scots, and the senior of a '' Toísech'' (chieftain). Mormaers were equivalent to English earls or Continental ...

, the legitimately married father of the late High King Duncan I

Donnchad mac Crinain (; anglicised as Duncan I, and nicknamed An t-Ilgarach, "the Diseased" or "the Sick"; – 14 August 1040)Broun, "Duncan I (d. 1040)". was king of Scotland (''Alba'') from 1034 to 1040. He is the historical basis of the "K ...

, the grandfather of King Malcolm III of Scotland

Malcolm III (; ; –13 November 1093) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Alba from 1058 to 1093. He was later nicknamed "Canmore" (, , understood as "great chief"). Malcolm's long reign of 35 years preceded the beginning of the Scoto-Norma ...

, and progenitor of the Scottish Royal House of Dunkeld

The House of Dunkeld (in or "of the Caledonians") is a historiographical and genealogical construct to illustrate the clear succession of Scottish kings from 1034 to 1040 and from 1058 to 1286. The line is also variously referred to by historian ...

.

Despite the ongoing religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic oppression of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religion, religious beliefs or affiliations or their irreligion, lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within socie ...

and expulsion from their monasteries and convents of "Romanists" like St Mo Chota, who opposed how much the Celtic Church had been, "absorbed by the tribal system" and lost its independence from control by local secular rulers, at least some of these issues had been resolved on both sides of the Irish Sea by the mid-seventh century.C. Evans, "The Celtic Church in Anglo-Saxon times", in J. D. Woods, D. A. E. Pelteret, ''The Anglo-Saxons, synthesis and achievement'' (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1985), , pp. 77–89. After the conversion, successful war for political independence from Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, and increasing Gaelicisation

Gaelicisation, or Gaelicization, is the act or process of making something Gaels, Gaelic or gaining characteristics of the ''Gaels'', a sub-branch of Celticisation. The Gaels are an ethno-linguistic group, traditionally viewed as having spread fro ...

of Scandinavian Scotland

Scandinavian Scotland was the period from the 8th to the 15th centuries during which Vikings and Norse settlers, mainly Norwegians and to a lesser extent other Scandinavians, and their descendants colonised parts of what is now the periphery of ...

and the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

under Somerled

Somerled (died 1164), known in Middle Irish as Somairle, Somhairle, and Somhairlidh, and in Old Norse as Sumarliði , was a mid-12th-century Norse-Gaelic lord who, through marital alliance and military conquest, rose in prominence to create the ...

and his heirs, the Roman Rite Diocese of the Isles

The Diocese of the Isles, also known as the Diocese of Suðreyar, or the Diocese of Sodor, was one of the dioceses of medieval Norway. After the mid-13th-century Treaty of Perth, the diocese was accounted as one of the 13 dioceses of Scotland. ...

under bishops appointed by the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

became the dominant religion.A. Macquarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , pp. 67–8.

Medieval era and Renaissance

St Margaret of Scotland

Saint Margaret of Scotland (; , ), also known as Margaret of Wessex, was Queen of Alba from 1070 to 1093 as the wife of King Malcolm III. Margaret was sometimes called "The Pearl of Scotland". She was a member of the House of Wessex and was b ...

, a clearly defined hierarchy of diocesan bishops and parochial structure for local churches, in line with the queen's experiences in Continental Europe, was developed.A. Macquarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , pp. 109–117. Following the 1286 extinction of the Royal House of Dunkeld

The House of Dunkeld (in or "of the Caledonians") is a historiographical and genealogical construct to illustrate the clear succession of Scottish kings from 1034 to 1040 and from 1058 to 1286. The line is also variously referred to by historian ...

and the subsequent invasion of Scotland by Edward Longshanks, the political purge

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertaking such an ...

of Scottish clergy from the hierarchy, religious orders, and parishes, and their replacement by English clergy was one of the root causes of the Scottish Wars of Independence

The Wars of Scottish Independence were a series of military campaigns fought between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England in the late 13th and 14th centuries.

The First War (1296–1328) began with the English invasion of Scotla ...

and is part of why so many of the Scottish clergy defied the pro-English policy of Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII (, , ; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death, in December 1334. He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Papacy, Avignon Pope, elected by ...

and signed the Declaration of Arbroath

The Declaration of Arbroath (; ; ) is the name usually given to a letter, dated 6 April 1320 at Arbroath, written by Scottish barons and addressed to Pope John XXII. It constituted King Robert I's response to his excommunication for disobey ...

. Following the Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn ( or ) was fought on 23–24 June 1314, between the army of Robert the Bruce, King of Scots, and the army of King Edward II of England, during the First War of Scottish Independence. It was a decisive victory for Ro ...

, large numbers of new foundations, which introduced Continental European forms of reformed monasticism, began to predominate as the Scottish church re-established its independence from England and developed a clearer diocesan structure, becoming a "special daughter of the see of Rome" but lacking leadership in the form of archbishops.P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, ''A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry'' (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), , pp. 26–9. During the Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

, similar to in other European countries, the Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy or Investiture Contest (, , ) was a conflict between church and state in medieval Europe, the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture), abbots of monasteri ...

and the Great Schism of the West allowed the Scottish Crown, like Scottish clan chief

The Scottish Gaelic word means children. In early times, and possibly even today, Scottish clan members believed themselves to descend from a common ancestor, the founder of the clan, after whom the clan is named. The clan chief (''ceannard ci ...

s using the erenagh

The medieval Irish office of erenagh (Old Irish: ''airchinnech'', Modern Irish: ''airchinneach'', Latin: '' princeps'') was responsible for receiving parish revenue from tithes and rents, building and maintaining church property and overseeing t ...

system during the time of the Celtic Church

Celtic Christianity is a form of Christianity that was common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages. The term Celtic Church is deprecated by many historians as it implies a unified and identifiab ...

, to gain greater influence over senior appointments to the hierarchy and two archbishoprics had accordingly been established by the end of the fifteenth century.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 76–87. While some historians have discerned a decline of monasticism in the Late Middle Ages, the mendicant

A mendicant (from , "begging") is one who practices mendicancy, relying chiefly or exclusively on alms to survive. In principle, Mendicant orders, mendicant religious orders own little property, either individually or collectively, and in many i ...

orders of friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders in the Catholic Church. There are also friars outside of the Catholic Church, such as within the Anglican Communion. The term, first used in the 12th or 13th century, distinguishes the mendi ...

s grew, particularly in the expanding burgh

A burgh ( ) is an Autonomy, autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots language, Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when David I of Scotland, King David I created ...

s, to meet the spiritual needs of the population. New saints and cults of religious devotion also proliferated. Despite problems over the number and quality of clergy after the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

in the fourteenth century, and the efforts of Hussite

file:Hussitenkriege.tif, upright=1.2, Battle between Hussites (left) and Crusades#Campaigns against heretics and schismatics, Catholic crusaders in the 15th century

file:The Bohemian Realm during the Hussite Wars.png, upright=1.2, The Lands of the ...

emissary Pavel Kravař

Pavel Kravař ( – 23 July 1433), or Paul Crawar, Paul Craw, was a Hussite emissary from Bohemia who was burned at the stake for heresy at St Andrews in Scotland on 23 July 1433. He was the first of a succession of religious reformers who were m ...

to spread doctrines considered heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

; the Renaissance in Scotland

The Renaissance in Scotland was a cultural, intellectual and artistic movement in Scotland, from the late fifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth century. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded ...

also saw wider availability of books, including the Classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

and newer works of early modern Scottish literature, due to Androw Myllar and Walter Chepman's introduction

Introduction, The Introduction, Intro, or The Intro may refer to:

General use

* Introduction (music), an opening section of a piece of music

* Introduction (writing), a beginning section to a book, article or essay which states its purpose and g ...

of the Gutenberg Revolution

The Gutenberg Bible, also known as the 42-line Bible, the Mazarin Bible or the B42, was the earliest major book printed in Europe using mass-produced metal movable type. It marked the start of the " Gutenberg Revolution" and the age of printed ...

to Scotland in 1507. The printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

also helped spread the " New Learning" known as Renaissance humanism, which was also embraced and spread by many Catholic clergy. This is not to say that everything was perfect, however.

The tradition of Crown-appointed "lay abbots" was reintroduced during the reign of James III of Scotland

James III (10 July 1451/May 1452 – 11 June 1488) was King of Scots from 1460 until his death at the Battle of Sauchieburn in 1488. He inherited the throne as a child following the death of his father, King James II, at the siege of Roxburg ...

, with similar results to the time of the Celtic Church. King James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV a ...

even appointed five of his illegitimate sons, with the assent of the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

, to the wealthiest abbacies in the Kingdom. According to George Scott-Moncrieff, "Such men were naturally opposed to administrative reform and as naturally enthusiastic for a revolution that would make them absolute possessors of property to which otherwise they would only claim the life-rent..." For this and similar reasons, many Scottish Catholic priests and monks who were also Renaissance humanists, such as Archbishop Andrew Forman

Andrew Forman (11 March 1521) was a Scottish diplomat and prelate who became Bishop of Moray in 1501, Archbishop of Bourges in France, in 1513, Archbishop of St Andrews in 1514 as well as being Commendator of several monasteries.

Early life

He ...

, Quintin Kennedy, and Ninian Winzet, "felt bitterly the failure of their fellow clergy to live the life they proclaimed", and called for an internal restoration of Christian morality

Christian ethics, also known as moral theology, is a multi-faceted ethical system. It is a Virtue ethics, virtue ethic, which focuses on building moral character, and a Deontological ethics, deontological ethic which emphasizes duty according ...

, that would later be dubbed the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

. Similar critiques and calls also appear in the Middle Scots

Middle Scots was the Anglic language of Lowland Scotland in the period from 1450 to 1700. By the end of the 15th century, its phonology, orthography, accidence, syntax and vocabulary had diverged markedly from Early Scots, which was virtual ...

poetry of Makar

A makar () is a term from Scottish literature for a poet or bard, often thought of as a royal court poet.

Since the 19th century, the term ''The Makars'' has been specifically used to refer to a number of poets of fifteenth and sixteenth cen ...

s William Dunbar

William Dunbar (1459 or 1460 – by 1530) was a Scottish makar, or court poet, active in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. He was closely associated with the court of King James IV and produced a large body of work in Scots d ...

and Robert Henryson

Robert Henryson (Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the Scots language, Scots ''makars'', he lived in the royal burgh of Dunfermline and is a distinctive voice in th ...

. Therefore, the Church in Scotland remained relatively strong and stable until the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

Fr ...

in the sixteenth century.

Scottish Reformation

Scotland remained a Catholic country until the arrival ofProtestant theology

Protestant theology refers to the doctrines held by various Protestant traditions, which share some things in common but differ in others. In general, Protestant theology, as a subset of Christian theology, holds to faith in the Christian Bible, t ...

in books smuggled from abroad, beginning in the early 16th century. As often happens in cases of religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic oppression of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religion, religious beliefs or affiliations or their irreligion, lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within socie ...

of any kind, efforts by the Hierarchy of the Church to enforce the traditional principle of Canon law that "error

An error (from the Latin , meaning 'to wander'Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “error (n.), Etymology,” September 2023, .) is an inaccurate or incorrect action, thought, or judgement.

In statistics, "error" refers to the difference between t ...

has no rights" and treat Protestantism as a criminal offense triggered a widespread public backlash. Particularly due to the greater availability and affordability of paper and books, the trials and executions of Protestant martyrs were widely publicized by the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

and helped spread Protestantism even further. In particular, after he was sentenced to death for his belief in Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

following an Ecclesiastical trial presided over by Archbishop James Beaton

James Beaton (or Bethune) ( – 15 February 1539) was a Roman Catholic Scottish church leader, the uncle of David Cardinal Beaton and the Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland.

Life

James Beaton was the sixth and youngest son of John Beaton ...

and burned at the stake

Death by burning is an list of execution methods, execution, murder, or suicide method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a puni ...

at St. Andrews in 1528, it was said that the "reek hat is, smoke

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

of Master Patrick Hamilton infected as many as it blew upon". Other similar cases had very similar results.

Despite also facing considerable popular opposition, the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

Fr ...

was effectively completed when the Scottish Parliament broke with the papacy and established a Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

confession by law in 1560. At that point, the offering or attending of the Mass