Scillies on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Isles of Scilly ( ; ) are a small

At the turn of the 14th century, the Abbot and convent of Tavistock Abbey petitioned the king,

William le Poer, coroner of Scilly, is recorded in 1305 as being worried about the extent of wrecking in the islands, and sending a petition to the King. The names provide a wide variety of origins, e.g. Robert and Henry Sage (English), Richard de Tregenestre (Cornish), Ace de Veldre (French), Davy Gogch (possibly Welsh, or Cornish), and Adam le Fuiz Yaldicz (possibly Spanish).

It is not known at what point the islanders stopped speaking the

At the turn of the 14th century, the Abbot and convent of Tavistock Abbey petitioned the king,

William le Poer, coroner of Scilly, is recorded in 1305 as being worried about the extent of wrecking in the islands, and sending a petition to the King. The names provide a wide variety of origins, e.g. Robert and Henry Sage (English), Richard de Tregenestre (Cornish), Ace de Veldre (French), Davy Gogch (possibly Welsh, or Cornish), and Adam le Fuiz Yaldicz (possibly Spanish).

It is not known at what point the islanders stopped speaking the

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago of five inhabited islands (six if

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago of five inhabited islands (six if

Education is available on the islands up to age 16. There is one school, the Five Islands Academy, which provides primary schooling at sites on St Agnes, St Mary's, St Martin's and Tresco, and secondary schooling at a site on St Mary's, with secondary students from outside St Mary's living at a school boarding house (Mundesley House) during the week. Sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds are entitled to a free sixth form place at a state school or sixth form college on the mainland, and are provided with free flights and a grant towards accommodation.

Education is available on the islands up to age 16. There is one school, the Five Islands Academy, which provides primary schooling at sites on St Agnes, St Mary's, St Martin's and Tresco, and secondary schooling at a site on St Mary's, with secondary students from outside St Mary's living at a school boarding house (Mundesley House) during the week. Sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds are entitled to a free sixth form place at a state school or sixth form college on the mainland, and are provided with free flights and a grant towards accommodation.

Today, tourism is estimated to account for 85% of the islands' income. The islands have been successful in attracting this investment due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient co-ordination of tourism providers and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities.''Isles of Scilly Local Plan: A 2020 Vision'', Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2004''Isles of Scilly 2004, imagine...'', Isles of Scilly Tourist Board, 2004

The islands' economy is highly dependent on tourism, even by the standards of other island communities. "The concentration [on] a small number of sectors is typical of most similarly sized UK island communities. However, it is the degree of concentration, which is distinctive along with the overall importance of tourism within the economy as a whole and the very limited manufacturing base that stands out".

Tourism is also a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation, and the lower number of tourists in winter results in a significant constriction of the islands' commercial activities. However, the tourist season benefits from an extended period of business in October when many birding, birdwatchers ("twitchers") arrive.

Today, tourism is estimated to account for 85% of the islands' income. The islands have been successful in attracting this investment due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient co-ordination of tourism providers and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities.''Isles of Scilly Local Plan: A 2020 Vision'', Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2004''Isles of Scilly 2004, imagine...'', Isles of Scilly Tourist Board, 2004

The islands' economy is highly dependent on tourism, even by the standards of other island communities. "The concentration [on] a small number of sectors is typical of most similarly sized UK island communities. However, it is the degree of concentration, which is distinctive along with the overall importance of tourism within the economy as a whole and the very limited manufacturing base that stands out".

Tourism is also a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation, and the lower number of tourists in winter results in a significant constriction of the islands' commercial activities. However, the tourist season benefits from an extended period of business in October when many birding, birdwatchers ("twitchers") arrive.

Council of the Isles of Scilly

/u> Source 2

Isles of Scilly Council Tax

/u>

St Mary's is the only island with a significant road network and the only island with classified roads - the A3110, A3111 and A3112. St Agnes and St Martin's also have public highways adopted by the local authority. In 2005 there were 619 registered vehicles on the island. The island also has taxicab, taxis and a tour bus. Vehicles on the islands are exempt from annual MOT tests.

Fixed-wing aircraft services, operated by Isles of Scilly Skybus, operate from Land's End Airport, Land's End, Newquay Cornwall Airport, Newquay and Exeter International Airport, Exeter to St Mary's Airport. A scheduled helicopter service has operated from a new Penzance Heliport to both St Mary's Airport, Isles of Scilly, St Mary's Airport and Tresco Heliport since 2020. The helicopter is the only direct flight to the island of

St Mary's is the only island with a significant road network and the only island with classified roads - the A3110, A3111 and A3112. St Agnes and St Martin's also have public highways adopted by the local authority. In 2005 there were 619 registered vehicles on the island. The island also has taxicab, taxis and a tour bus. Vehicles on the islands are exempt from annual MOT tests.

Fixed-wing aircraft services, operated by Isles of Scilly Skybus, operate from Land's End Airport, Land's End, Newquay Cornwall Airport, Newquay and Exeter International Airport, Exeter to St Mary's Airport. A scheduled helicopter service has operated from a new Penzance Heliport to both St Mary's Airport, Isles of Scilly, St Mary's Airport and Tresco Heliport since 2020. The helicopter is the only direct flight to the island of

Council of the Isles of Scilly

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Scilly, Isles of Isles of Scilly, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty in England Birdwatching sites in England Important Bird Areas of England Important Bird Areas of Atlantic islands Celtic Sea Dark-sky preserves in the United Kingdom Duchy of Cornwall Hundreds of Cornwall, Isles of Scilly Local government districts in Cornwall, Isles of Scilly Natural regions of England Nature Conservation Review sites NUTS 2 statistical regions of the European Union, Isles of Scilly Ramsar sites in England Special Protection Areas in England Former civil parishes in Cornwall, Isles of Scilly Car-free islands of Europe

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

off the southwestern tip of Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, is over farther south than the most southerly point of the British mainland at Lizard Point, and has the southernmost inhabited settlement in England, Troy Town.

The total population of the islands at the 2021 United Kingdom census

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number, Numeral (linguistics), numeral, and glyph. It is the first and smallest Positive number, positive integer of the infinite sequence of natural numbers. This fundamental property has led to its unique uses in o ...

was 2,100 (rounded to the nearest 100). A majority live on one island, St Mary's, and close to half live in Hugh Town

Hugh Town ( or ) is the largest settlement on the Isles of Scilly and its administrative centre. The town is situated on the island of St Mary's, Isles of Scilly, St Mary's, the largest and most populous island in the archipelago, and is located ...

; the remainder live on four inhabited "off-islands". Scilly forms part of the ceremonial county

Ceremonial counties, formally known as ''counties for the purposes of the lieutenancies'', are areas of England to which lord-lieutenant, lord-lieutenants are appointed. A lord-lieutenant is the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, monarch's repres ...

of Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, and some services are combined with those of Cornwall. However, since 1890, the islands have had a separate local authority. Since the passing of the Isles of Scilly Order 1930, this authority has held the status of county council

A county council is the elected administrative body governing an area known as a county. This term has slightly different meanings in different countries.

Australia

In the Australian state of New South Wales, county councils are special purpose ...

, and today it is known as the Council of the Isles of Scilly.

The adjective "Scillonian" is sometimes used for people or things related to the archipelago. The Duchy of Cornwall

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important difference between "sovereign ...

owns most of the freehold land on the islands. Tourism

Tourism is travel for pleasure, and the Commerce, commercial activity of providing and supporting such travel. World Tourism Organization, UN Tourism defines tourism more generally, in terms which go "beyond the common perception of tourism as ...

is a major part of the local economy along with agriculture, particularly the production of cut flowers

Cut flowers are flowers and flower buds (often with some Plant stem, stem and leaf) that have been cut from the plant bearing it. It is removed from the plant for decorative use. Cut greens are leaves with or without stems added to the cut flow ...

.

Name

Scilly was known to the Romans as ''Sil(l)ina'', a Latinisation of a Brittonic name represented by Cornish ''Sillan''. The name is of unknown origin, but has been speculatively linked to the goddessSulis

In the localised Celtic polytheism practised in Great Britain, Sulis was a deity worshiped at the thermal spring of Bath. She was worshiped by the Romano-British as Sulis Minerva, whose votive objects and inscribed lead tablets suggest that she ...

. The English name ''Scilly'' first appears in 1176, in the form ''Sully''. The unetymological ''c'' was added in the 16th century in order to distinguish the name from the word "silly", whose meaning was shifting at this time from "happy" to "foolish".

The islands are known in the Standard Written Form

The Standard Written Form or SWF () of the Cornish language is an orthography standard that is designed to "provide public bodies and the educational system with a universally acceptable, inclusive, and neutral orthography". It was the outcome of ...

of Cornish as or . In French, they are called the ''Sorlingues'', from Old Norse ''Syllingar'' (incorporating the suffix -''ingr''). Mercator __NOTOC__

Mercator (Latin for "merchant") often refers to the Mercator projection, a cartographic projection named after its inventor, Gerardus Mercator.

Mercator may refer to:

People

* Marius Mercator (c. 390–451), a Catholic ecclesiastica ...

used this name on his 1564 map of Britain, causing it to spread to several European languages.

History

Early history

The islands may correspond to theCassiterides

The Cassiterides (, meaning "tin place", from κασσίτερος, ''kassíteros'' " tin") are an ancient geographical name used to refer to a group of islands whose precise location is unknown or may be fictitious, but which was believed to b ...

("Tin Isles"), believed by some to have been visited by the Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns and mentioned by the Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

. While Cornwall is an ancient tin-mining region, there is no evidence of this having taken place substantially on the islands.

During the Late Roman Empire

In historiography, the Late or Later Roman Empire, traditionally covering the period from 284 CE to 641 CE, was a time of significant transformation in Roman governance, society, and religion. Diocletian's reforms, including the establishment of t ...

, the islands may have been a place of exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

. At least one person, one Tiberianus from Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

, is known to have been condemned c. 385 to banishment on the isles, as well as the bishop Instantius, as part of the prosecution of the Priscillianist

Priscillianism was a Christian sect developed in the Roman province of Hispania in the 4th century by Priscillian. It is derived from the Gnostic doctrines taught by Marcus, an Egyptian from Memphis. Priscillianism was later considered a heresy b ...

s.

The isles were off the coast of the Brittonic Celtic kingdom of Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for a Brythonic kingdom that existed in Sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries CE in the more westerly parts of present-day South West England. It was centred in the area of modern Devon, ...

(and its future offshoot of ''Kernow'', or Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

). Later, c. 570, when the modern Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefor ...

—and, in 577, the Severn Valley

The Severn Valley is a rural area of the West Midlands region of England, through which the River Severn runs and the Severn Valley Railway steam heritage line operates, starting at its northernmost point in Bridgnorth, Shropshire and runnin ...

—fell to Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

control, the remaining Britons were split into three separate regions: the West (Cornwall), Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

and Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial county in North West England. It borders the Scottish council areas of Dumfries and Galloway and Scottish Borders to the north, Northumberland and County Durham to the east, North Yorkshire to the south-east, Lancash ...

– (Strathclyde

Strathclyde ( in Welsh language, Welsh; in Scottish Gaelic, Gaelic, meaning 'strath

).

The islands may have been a part of these alley

An alley or alleyway is a narrow lane, footpath, path, or passageway, often reserved for pedestrians, which usually runs between, behind, or within buildings in towns and cities. It is also a rear access or service road (back lane), or a path, w ...

of the River Clyde') was one of nine former Local government in Scotland, local government Regions and districts of Scotland, regions of Scotland cre ...polities

A polity is a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of political institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources.

A polity can be any group of people organized for governance ...

until a short-lived conquest, by the English, in the 10th century was cut short by the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

.

It is likely that, until relatively recent times, the islands were much larger, and perhaps conjoined into one island named Ennor. Rising sea levels

The sea level has been rising from the end of the last ice age, which was around 20,000 years ago. Between 1901 and 2018, the average sea level rose by , with an increase of per year since the 1970s. This was faster than the sea level had e ...

flooded the central plain around 400–500 AD, forming the current 55 islands and islets (if an island is defined as "land surrounded by water at high tide and supporting land vegetation"). Originally written by Ernest Lyon Bowley and published in 1945 by W. P. Kennedy. The word is a contraction of the Old Cornish

Cornish ( Standard Written Form: or , ) is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. Along with Welsh and Breton, Cornish descends from Common Brittonic, a language once spoken widely across Great Britain. For much o ...

(, mutated

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA replication, DNA or viral rep ...

to ), meaning 'the land' or 'the great island'.

Evidence for the older, large island includes:

* A description, written during Ancient Roman times, designates Scilly "" in the singular

Singular may refer to:

* Singular, the grammatical number that denotes a unit quantity, as opposed to the plural and other forms

* Singular or sounder, a group of boar, see List of animal names

* Singular (band), a Thai jazz pop duo

*'' Singula ...

, indicating either a single island or an island much bigger than any of the others.

* Remains of a prehistoric farm have been found on Nornour (now a small, rocky skerry

A skerry ( ) is a small rocky island, or islet, usually too small for human habitation. It may simply be a rocky reef. A skerry can also be called a low stack (geology), sea stack.

A skerry may have vegetative life such as moss and small, ...

far too small for farming). includes a description of over 250 Roman fibulae found at the site. There once was an Iron Age British community here that continued into Roman times. This community was likely formed by immigrants from Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

—probably the Veneti—who were active in the tin trade that originated in mining activity in Cornwall and Devon.

* At certain low tides, the sea becomes shallow enough for people to walk between some of the islands. This is possibly one of the sources for stories of "drowned lands", e.g. Lyonesse

Lyonesse ( /liːɒˈnɛs/ ''lee-uh-NESS'') is a kingdom which, according to legend, consisted of a long strand of land stretching from Land's End at the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England, to what is now the Isles of Scilly in the Celtic ...

.

* Ancient field walls are visible below the high tideline

A tideline refers to where two currents in the ocean converge. Driftwood, floating seaweed, foam, and other floating debris may accumulate, forming sinuous lines called tidelines (although they generally have nothing to do with the tide).

There ...

off some of the islands, such as Samson

SAMSON (Software for Adaptive Modeling and Simulation Of Nanosystems) is a computer software platform for molecular design being developed bOneAngstromand previously by the NANO-D group at the French Institute for Research in Computer Science an ...

.

* Some of the Cornish-language place names also appear to reflect historical shorelines and former land areas.

* The whole of southern England

Southern England, also known as the South of England or the South, is a sub-national part of England. Officially, it is made up of the southern, south-western and part of the eastern parts of England, consisting of the statistical regions of ...

has been steadily sinking, in opposition to post-glacial rebound

Post-glacial rebound (also called isostatic rebound or crustal rebound) is the rise of land masses after the removal of the huge weight of ice sheets during the last glacial period, which had caused isostatic depression. Post-glacial rebound an ...

in Scotland: this has caused the ria

A ria (; , feminine noun derived from ''río'', river) is a coastal inlet formed by the partial submergence of an unglaciated river valley. It is a drowned river valley that remains open to the sea.

Definitions

Typically rias have a dendriti ...

s (drowned river valleys) on the southern Cornish coast, e.g. River Fal

The River Fal () flows through Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordere ...

and the Tamar Estuary

Tamar may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Tamar'' (album), by Tamar Braxton, 2000

* ''Tamar'' (novel), by Mal Peet, 2005

* ''Tamar'' (poem), an epic poem by Robinson Jeffers

* ''Tamar'' (painting), an 1847 painting by Francesco Ha ...

.

Offshore, midway between Land's End

Land's End ( or ''Pedn an Wlas'') is a headland and tourist and holiday complex in western Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, on the Penwith peninsula about west-south-west of Penzance at the western end of the A30 road. To the east of it is ...

and the Isles of Scilly, is the supposed location of the mythical lost land of Lyonesse

Lyonesse ( /liːɒˈnɛs/ ''lee-uh-NESS'') is a kingdom which, according to legend, consisted of a long strand of land stretching from Land's End at the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England, to what is now the Isles of Scilly in the Celtic ...

, referred to in Arthurian

According to legends, King Arthur (; ; ; ) was a king of Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a leader of the post-Ro ...

literature (of which Tristan

Tristan (Latin/ Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; ; ), also known as Tristran or Tristram and similar names, is the folk hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. While escorting the Irish princess Iseult to wed Tristan's uncle, King Mark of ...

is said to have been a prince). This may be a folk memory

Folk memory, also known as folklore or myths, refers to past events that have been passed orally from generation to generation. The events described by the memories may date back hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of years and often ha ...

of inundated lands, but this legend is also common among the Brythonic peoples; the legend of Ys is a parallel and cognate legend in Brittany, as is that of in Wales.

Norse and Norman period

In 995,Olaf Tryggvason

Olaf Tryggvason (960s – 9 September 1000) was King of Norway from 995 to 1000. He was the son of Tryggvi Olafsson, king of Viken ( Vingulmark, and Rånrike), and, according to later sagas, the great-grandson of Harald Fairhair, first King ...

became King Olaf I of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

. Born 960, Olaf had raided various European cities and fought in several wars. In 986 he met a Christian seer

A seer is a person who practices divination.

Seer(s) or SEER may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Seer (band), an Austrian music band

* Seer (game series), a Chinese video game and cartoon series

** ''Seer'' (film), 2011, based on the ...

on the Isles of Scilly. He was probably a follower of Priscillian

Priscillian (in Latin: ''Priscillianus''; Gallaecia, – Augusta Treverorum, Gallia Belgica, ) was a wealthy nobleman of Roman Hispania who promoted a strict form of Christian asceticism. He became bishop of Ávila in 380. Certain practices of his ...

and part of the tiny Christian community that was exiled here from Spain by Emperor Maximus

Magnus Maximus (; died 28 August 388) was Roman emperor in the West from 383 to 388. He usurped the throne from emperor Gratian.

Born in Gallaecia, he served as an officer in Britain under Theodosius the Elder during the Great Conspiracy. I ...

for Priscillianism

Priscillianism was a Christianity, Christian sect developed in the Roman province of Hispania in the 4th century by Priscillian. It is derived from the Gnosticism, Gnostic doctrines taught by Marcus, an Ægyptus, Egyptian from Memphis, Egypt, Memp ...

. In Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson ( ; ; 1179 – 22 September 1241) was an Icelandic historian, poet, and politician. He was elected twice as lawspeaker of the Icelandic parliament, the Althing. He is commonly thought to have authored or compiled portions of th ...

's ''Royal Sagas of Norway'', it is stated that this seer told him:

The legend continues that, as the seer foretold, Olaf was attacked by a group of mutineers

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, bu ...

upon returning to his ships. As soon as he had recovered from his wounds, he let himself be baptised. He then stopped raiding Christian cities, and lived in England and Ireland. In 995, he used an opportunity to return to Norway. When he arrived, the Haakon Jarl

Haakon Sigurdsson ( , ; 937–995), known as Haakon Jarl (Old Norse: ''Hákon jarl''), was the '' de facto'' ruler of Norway from about 975 to 995. Sometimes he is styled as Haakon the Powerful (), though the '' Ágrip'' and ''Historia Norwe ...

was facing a revolt. Olaf Tryggvason persuaded the rebels to accept him as their king, and Jarl Haakon was murdered by his own slave, while he was hiding from the rebels in a pig sty.

With the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

, the Isles of Scilly came more under centralised Norman control. About 20 years later, the Domesday survey

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

was conducted. The islands would have formed part of the "Exeter

Exeter ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and the county town of Devon in South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter w ...

Domesday" circuit, which included Cornwall, Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

, Dorset, Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

, and Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

.

In the mid-12th century, there was reportedly a Viking attack on the Isles of Scilly, called by the Norse, recorded in the —Sweyn Asleifsson

Sweyn Asleifsson or Sveinn Ásleifarson ( 1115 – 1171) was a 12th-century Viking who appears in the '' Orkneyinga Saga''.

Early career

Sweyn was born in Caithness in the early twelfth century, to Olaf Hrolfsson and his wife Åsleik. According t ...

"went south, under Ireland, and seized a barge belonging to some monks in Syllingar and plundered it." (Chap LXXIII)

"" literally means "Mary's Harbour/Haven". The name does not make it clear if it referred to a harbour on a larger island than today's St Mary's, or a whole island.

It is generally considered that Cornwall, and possibly the Isles of Scilly, came under the dominion of the English Crown for a period until the Norman conquest, late in the reign of Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ; ; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his first wife, Ecgwynn. Modern histori ...

( 924–939). In early times one group of islands was in the possession of a confederacy of hermits. King Henry I (r. 1100–1135) gave it to the abbey of Tavistock who established a priory on Tresco Tresco may refer to:

* Tresco, Elizabeth Bay, a historic residence in New South Wales, Australia

* Tresco, Isles of Scilly, an island off Cornwall, England, United Kingdom

* Tresco, Victoria, a town in Victoria, Australia

* a nickname referring t ...

, which was abolished at the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

.

Later Middle Ages and early modern period

At the turn of the 14th century, the Abbot and convent of Tavistock Abbey petitioned the king,

William le Poer, coroner of Scilly, is recorded in 1305 as being worried about the extent of wrecking in the islands, and sending a petition to the King. The names provide a wide variety of origins, e.g. Robert and Henry Sage (English), Richard de Tregenestre (Cornish), Ace de Veldre (French), Davy Gogch (possibly Welsh, or Cornish), and Adam le Fuiz Yaldicz (possibly Spanish).

It is not known at what point the islanders stopped speaking the

At the turn of the 14th century, the Abbot and convent of Tavistock Abbey petitioned the king,

William le Poer, coroner of Scilly, is recorded in 1305 as being worried about the extent of wrecking in the islands, and sending a petition to the King. The names provide a wide variety of origins, e.g. Robert and Henry Sage (English), Richard de Tregenestre (Cornish), Ace de Veldre (French), Davy Gogch (possibly Welsh, or Cornish), and Adam le Fuiz Yaldicz (possibly Spanish).

It is not known at what point the islanders stopped speaking the Cornish language

Cornish (Standard Written Form: or , ) is a Southwestern Brittonic language, Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. Along with Welsh language, Welsh and Breton language, Breton, Cornish descends from Common Brittonic, ...

, but the language seems to have gone into decline in Cornwall beginning in the Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

; it was still dominant between the islands and Bodmin at the time of the Reformation, but it suffered an accelerated decline thereafter. The islands appear to have lost the old Brythonic (Celtic P) language before parts of Penwith

Penwith (; ) is an area of Cornwall, England, located on the peninsula of the same name. It is also the name of a former Non-metropolitan district, local government district, whose council was based in Penzance. The area is named after one ...

on the mainland, in contrast to its Welsh sister language. Cornish is not directly linked to Irish or Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

which falls into the Celtic Q group of languages.

During the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, the Parliamentarians captured the isles, only to see their garrison mutiny and return the isles to the Royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gover ...

. By 1651 the Royalist governor, Sir John Grenville, was using the islands as a base for privateering

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since Piracy, robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sover ...

raids on Commonwealth and Dutch shipping. The Dutch admiral Maarten Tromp

Maarten Harpertszoon Tromp or Maarten van Tromp (23 April 1598 – 31 July 1653) was an army general and admiral in the Dutch navy during much of the Eighty Years' War and throughout the First Anglo-Dutch War. Son of a ship's captain, Tromp spe ...

sailed to the isles and on arriving on 30 May 1651 demanded compensation. In the absence of compensation or a satisfactory reply, he declared war on England in June. It was during this period that the disputed Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years' War

The Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years' War ( ; ) was an alleged state of war between the Netherlands and the Isles of Scilly (located off the southwest coast of Great Britain). It is said to have been extended by the lack of a peace treaty ...

started between the isles and the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

.

In June 1651, Admiral Robert Blake recaptured the isles for the Parliamentarians. Blake's initial attack on Old Grimsby

Old Grimsby () is a coastal settlement on the island of Tresco in the Isles of Scilly, England.Ordnance Survey mapping It is located on the east side of the island and there is a quay. At the southern end of the harbour bay is the Blockhouse, a ...

failed, but the next attacks succeeded in taking Tresco Tresco may refer to:

* Tresco, Elizabeth Bay, a historic residence in New South Wales, Australia

* Tresco, Isles of Scilly, an island off Cornwall, England, United Kingdom

* Tresco, Victoria, a town in Victoria, Australia

* a nickname referring t ...

and Bryher

Bryher () is one of the smallest inhabited islands of the Isles of Scilly, with a population of 84 in 2011, spread across . Bryher exhibits a procession of prominent hills connected by low-lying necks and sandy bars. Landmarks include Hell Bay, ...

. Blake placed a battery on Tresco to fire on St Mary's, but one of the guns exploded, killing its crew and injuring Blake. A second battery proved more successful. Subsequently, Grenville and Blake negotiated terms that permitted the Royalists to surrender honourably. The Parliamentary forces then set to fortifying the islands. They built Cromwell's Castle

Cromwell's Castle is an artillery fort overlooking New Grimsby harbour on the island of Tresco, Isles of Scilly, Tresco in the Isles of Scilly. It comprises a tall, circular gun tower and an adjacent gun platform, and was designed to prevent en ...

—a gun platform on the west side of Tresco—using materials scavenged from an earlier gun platform further up the hill. Although this poorly sited earlier platform dated back to the 1550s, it is now referred to as King Charles's Castle.

The Isles of Scilly served as a place of exile during the English Civil War. Among those exiled there was Unitarian Jon Biddle.

During the night of 22 October 1707, the isles were the scene of one of the worst maritime disasters in British history, when out of a fleet of 21 Royal Navy ships headed from Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

to Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

, six were driven onto the cliffs. Four of the ships sank or capsized, with at least 1,450 dead, including the commanding admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Sir Cloudesley Shovell

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Cloudesley Shovell ( – 22/23 October 1707) was an Royal Navy officer and politician. As a junior officer he saw action at the Battle of Solebay and Battle of Texel during the Third Anglo-Dutch War. As a captain he fo ...

.

There is evidence of inundation by the tsunami caused by the 1755 Lisbon earthquake

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, also known as the Great Lisbon earthquake, impacted Portugal, the Iberian Peninsula, and Northwest Africa on the morning of Saturday, 1 November, All Saints' Day, Feast of All Saints, at around 09:40 local time. In ...

.

Geography

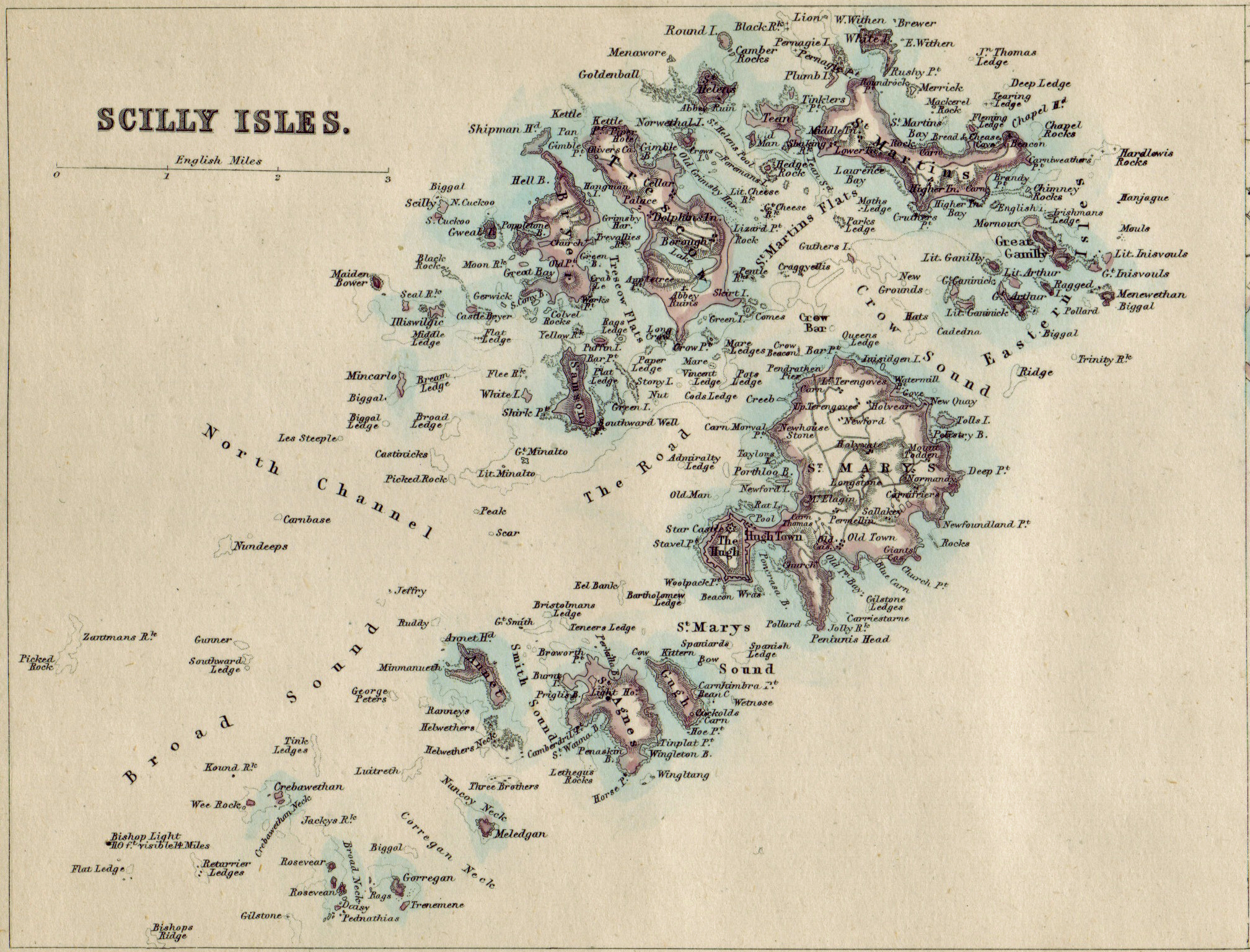

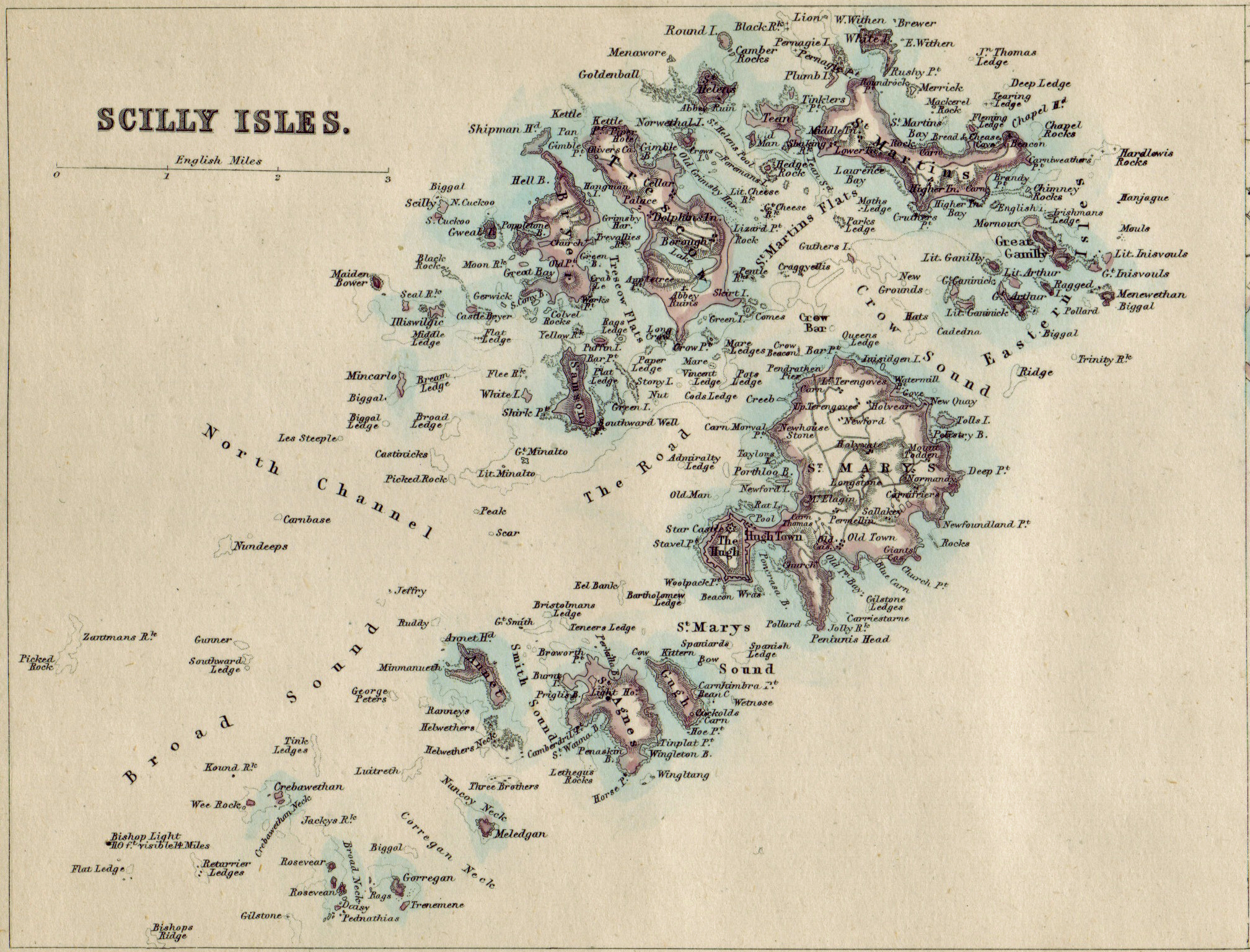

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago of five inhabited islands (six if

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago of five inhabited islands (six if Gugh

Gugh ( ; ) could be described as the sixth inhabited island of the Isles of Scilly, but is usually included with St Agnes with which it is joined by a sandy tombolo known as "The Bar" when exposed at low tide. The island is only about long a ...

is counted separately from St Agnes) and numerous other small rocky islet

An islet ( ) is generally a small island. Definitions vary, and are not precise, but some suggest that an islet is a very small, often unnamed, island with little or no vegetation to support human habitation. It may be made of rock, sand and/ ...

s (around 140 in total) lying off Land's End

Land's End ( or ''Pedn an Wlas'') is a headland and tourist and holiday complex in western Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, on the Penwith peninsula about west-south-west of Penzance at the western end of the A30 road. To the east of it is ...

. Troy Town Farm on St Agnes is the southernmost settlement of the United Kingdom.

The islands' position produces a place of great contrast; the ameliorating effect of the sea, greatly influenced by the North Atlantic Current

The North Atlantic Current (NAC), also known as North Atlantic Drift and North Atlantic Sea Movement, is a powerful warm western boundary current within the Atlantic Ocean that extends the Gulf Stream northeastward.

Characteristics

The NAC ...

, means they rarely have frost or snow, which allows local farmers to grow flowers well ahead of those in mainland Britain. The chief agricultural product is cut flowers, mostly daffodil

''Narcissus'' is a genus of predominantly spring flowering perennial plants of the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae. Various common names including daffodil,The word "daffodil" is also applied to related genera such as '' Sternbergia'', '' ...

s. Exposure to Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

winds also means that spectacular winter gales lash the islands from time to time. This is reflected in the landscape, most clearly seen on Tresco where the lush Abbey Gardens on the sheltered southern end of the island contrast with the low heather and bare rock sculpted by the wind on the exposed northern end.

Natural England

Natural England is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. It is responsible for ensuring that England's natural environment, including its land, flora and fauna, ...

has designated the Isles of Scilly as National Character Area

A National Character Area (NCA) is a natural subdivision of England based on a combination of landscape, biodiversity, geodiversity and economic activity. There are 159 National Character Areas and they follow natural, rather than administrative, b ...

158. As part of a 2002 marketing campaign, the plant conservation charity Plantlife

Plantlife is a wild plant conservation charity. , it manages 24 nature reserves around the United Kingdom. HM King Charles III is patron of the charity.

History

Plantlife was founded in 1989. Its first president was Professor David Bellamy ...

chose sea thrift (''Armeria maritima

''Armeria maritima'', the thrift, sea thrift or sea pink, is a species of flowering plant in the family Plumbaginaceae. It is a compact evergreen perennial which grows in low clumps and sends up long stems that support globes of bright pink flow ...

'') as the "county flower

In 2002 Plantlife conducted a "County Flowers" public survey to assign flowers to each of the counties of the United Kingdom and the Isle of Man. The results of this campaign designated a single plant species to a "county or metropolitan area" in ...

" of the islands.

(1) Inhabited until 1855.

In 1975 the islands were designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB; , AHNE) is one of 46 areas of countryside in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland that has been designated for conservation due to its significant landscape value. Since 2023, the areas in England an ...

. The designation covers the entire archipelago, including the uninhabited islands and rocks, and is the smallest such area in the UK. The islands of Annet and Samson have large tern

Terns are seabirds in the family Laridae, subfamily Sterninae, that have a worldwide distribution and are normally found near the sea, rivers, or wetlands. Terns are treated in eleven genera in a subgroup of the family Laridae, which also ...

eries and the islands are well populated by seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

. The Isles of Scilly are the only British habitat of the lesser white-toothed shrew

The lesser white-toothed shrew (''Crocidura suaveolens'') is a small species of shrew with a widespread distribution in Africa, Asia and Europe. Its preferred habitat is scrub and gardens and it feeds on insects, arachnids, worms, gastropods, n ...

(''Crocidura suaveolens''), where it is known locally as a "''teak''" or "''teke''".

Tidal influx

The tidal range at the Isles of Scilly is high for an open sea location; the maximum for St Mary's is . Additionally, the inter-island waters are mostly shallow, which atspring tides

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables c ...

allows for dry land walking between several of the islands. Many of the northern islands can be reached from Tresco, including Bryher, Samson and St Martin's (requires very low tides). From St Martin's White Island, Little Ganilly and Great Arthur are reachable. Although the sound between St Mary's and Tresco, The Road, is fairly shallow, it never becomes totally dry, but according to some sources it should be possible to wade at extreme low tides. Around St Mary's several minor islands become accessible, including Taylor's Island on the west coast and Tolls Island on the east coast. From Saint Agnes, Gugh becomes accessible at each low tide, via a tombolo

A tombolo is a sandy or shingle isthmus. It is a deposition landform by which an island becomes attached to the mainland by a narrow piece of land such as a spit or bar. Once attached, the island is then known as a tied island. The word ''t ...

.

Climate

The Isles of Scilly have aoceanic climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate or maritime climate, is the temperate climate sub-type in Köppen climate classification, Köppen classification represented as ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of co ...

(Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (1951–2014), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author ...

: ''Cfb''). The average annual temperature is , the warmest place in the British Isles. Winters are, by far, the warmest in the UK due to the moderating effects of the North Atlantic Drift

The North Atlantic Current (NAC), also known as North Atlantic Drift and North Atlantic Sea Movement, is a powerful warm western boundary current within the Atlantic Ocean that extends the Gulf Stream northeastward.

Characteristics

The NAC ...

of the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

. Despite being on exactly the same latitude as Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. It is centred on the confluence of the Red River of the North, Red and Assiniboine River, Assiniboine rivers. , Winnipeg h ...

in Canada, snow and frost are extremely rare. The maximum snowfall was on 12 January 1987.

The climate has mild winters and cool summers, moderated by the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

, thus summer temperatures are not as warm as on the mainland. However, the Isles are one of the sunniest areas in the southwest with an average of seven hours per day in May. The lowest temperature ever recorded was and the highest was . The isles have never recorded a temperature below freezing in the months from May to November inclusive. Precipitation (the overwhelming majority of which is rain) averages about per year. The wettest months are from October to January, while April and May are the driest months.

Geology

All the islands of Scilly are all composed ofgranite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

rock of Early Permian 01 or 01 may refer to:

* The year 2001, or any year ending with 01

* The month of January

* 1 (number)

Music

* '01 (Richard Müller album), ''01'' (Richard Müller album), 2001

* 01 (Urban Zakapa album), ''01'' (Urban Zakapa album), 2011

* ''01011 ...

age, an exposed part of the Cornubian batholith

The Cornubian batholith is a large mass of granite rock, formed about 280 million years ago, which lies beneath much of Cornwall and Devon in the South West Peninsula of England. The main exposed masses of granite are seen at Dartmoor, Bodmin M ...

. The Irish Sea Glacier

The British-Irish Ice Sheet (BIIS), a component of which was the Irish Sea Glacier was an ice sheet during the Pleistocene Ice Age that, probably on more than one occasion, flowed southwards from its source areas in Scotland and Ireland and ac ...

terminated just to the north of the Isles of Scilly during the last ice age.

Ancient monuments and historic buildings

Historic sites on the Isles of Scilly include: *Bant's Carn

Bant's Carn is a Bronze Age entrance grave located on a steep slope on the island of St Mary's in the Isles of Scilly, England. The tomb is one of the best examples of a Scillonian entrance grave. Below Bant's Carn, lies the remains of the Iro ...

, a Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

entrance grave

* Halangy Down Ancient Village

* Porth Hellick Down Burial Chamber

* Innisidgen Lower and Upper Burial Chambers

* The Old Blockhouse

* King Charles's Castle

* Harry's Walls

Harry's Walls are the remains of an unfinished artillery fort, started in 1551 by the government of Edward VI of England, Edward VI to defend the island of St Mary's, Isles of Scilly, St Mary's in the Isles of Scilly. Constructed to defend the ...

, an unfinished artillery fort

* Garrison Tower

* Cromwell's Castle

Cromwell's Castle is an artillery fort overlooking New Grimsby harbour on the island of Tresco, Isles of Scilly, Tresco in the Isles of Scilly. It comprises a tall, circular gun tower and an adjacent gun platform, and was designed to prevent en ...

Flora

The Isles of Scilly have been a famous location for flower farming for centuries, and in that timehorticultural flora

A horticultural flora, also known as a garden flora, is a plant identification aid structured in the same way as a native plants flora. It serves the same purpose: to facilitate plant identification; however, it only includes plants that are under ...

has become a mainstay of the Scillonian economy.

Due to the oceanic climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate or maritime climate, is the temperate climate sub-type in Köppen climate classification, Köppen classification represented as ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of co ...

found on the Isles of Scilly the isles have the unique ability to grow a multitude of plants found around the world.

Perhaps the most prominently grown flower on the Isles are the scented Narcissi or Narcissus

Narcissus may refer to:

Biology

* ''Narcissus'' (plant), a genus containing daffodils and others

People

* Narcissus (mythology), Greek mythological character

* Narcissus (wrestler) (2nd century), assassin of the Roman emperor Commodus

* Tiberius ...

, commonly known as the daffodil. There are flower farms on the isles of St. Agnes, St. Mary's, as well as St. Martin's and Bryher. The scented Narcissi are grown October through April, scented pinks or Dianthus

''Dianthus'' ( ) is a genus of about 340 species of flowering plants in the family Caryophyllaceae, native mainly to Europe and Asia, with a few species in north Africa and in southern Africa, and one species (''D. repens'') in arctic North Am ...

are the second most notably grown flower on the isles which are in full bloom from May through September. Summer time on the Isles provides the temperate conditions for the blossom of many more types of plant. Bermuda Buttercup or Oxalis pes-caprae

''Oxalis pes-caprae'', commonly known as African wood-sorrel, Bermuda buttercup, Bermuda sorrel, buttercup oxalis, Cape sorrel, English weed, goat's-foot, sourgrass, soursob or soursop; ; (حميضة), is a species of tristylous yellow-floweri ...

are very often found growing in bulb fields. In early summer, Digitalis

''Digitalis'' ( or ) is a genus of about 20 species of herbaceous perennial plants, shrubs, and Biennial plant, biennials, commonly called foxgloves.

''Digitalis'' is native to Europe, Western Asia, and northwestern Africa. The flowers are ...

colloquially known as foxgloves grow amongst hedgerows and bramble

''Rubus'' is a large and diverse genus of flowering plants in the rose family, Rosaceae, subfamily Rosoideae, most commonly known as brambles. Fruits of various species are known as raspberries, blackberries, dewberries, and bristleberries. I ...

.

Other common sprouting plants throughout the summer season include:

*''Ixia maculata

''Ixia maculata'' is a species of flowering plant in the family Iridaceae known by the common name spotted African corn lily. It is native to the Cape Provinces of South Africa, but it is grown widely as an ornamental plant. It can also be found ...

''

*''Iris pseudacorus

''Iris pseudacorus'', the yellow flag, yellow iris, or water flag, is a species of flowering plant in the family Iridaceae. It is native to Europe, western Asia and northwest Africa. Its specific epithet ''pseudacorus'' means "false acorus", r ...

''

*''Lythrum salicaria

''Lythrum salicaria'' or purple loosestrifeFlora of NW Europe''Lythrum salicaria'' is a flowering plant belonging to the family Lythraceae. It should not be confused with other plants sharing the name loosestrife that are members of the family Pr ...

''

*''Oenanthe crocata

''Oenanthe crocata'', hemlock water-dropwort (sometimes known as dead man's fingers) is a flowering plant in the Apiaceae, carrot family, native to Europe, North Africa and western Asia. It grows in damp grassland and wet woodland, often along ri ...

''

In saturated areas you might observe:

*''Lysimachia tenella

''Lysimachia tenella'', synonym ''Anagallis tenella'', known in Britain as the bog pimpernel, is a low growing perennial plant found in a variety of damp habitats from calcareous dune slacks to boggy and peaty heaths in western and southern Eur ...

'', syn. ''Anagallis tenella''

*''Mentha aquatica

''Mentha aquatica'' (water mint; syn. ''Mentha hirsuta'' Huds.Euro+Med Plantbase Project''Mentha aquatica'') is a perennial flowering plant in the mint family, Lamiaceae. It grows in moist places and is native to much of Europe, northwest Africa ...

''

*''Stellaria alsine''

*''Triadenum''

Hedgerows were planted a century ago as windbreaks to protect the crop fields and to survive battering from storms and sea spray. To thrive there, plants need sturdy roots and the ability to withstand salt and gusty winds.

A many species of exotic plants have been brought in over the years including some trees; however there are still few remaining native tree species on the Isles of Scilly: these include elm, Elder tree, elder, Crataegus monogyna, hawthorn and grey sallow.

Fauna

Scilly is situated far into theAtlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

, so many North American vagrant birds will make first European landfall in the archipelago. Scilly is responsible for many firsts for Britain, and is particularly good at producing vagrant American passerines. If an extremely rare bird turns up, the island will see a significant increase in numbers of birders. The islands are famous among birdwatching, birdwatchers for the large variety of rare and migratory birds that visit the islands. The peak time of year for sightings is generally in the autumn.

Important Bird Area

The archipelago has been designated an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports breeding populations of several species of seabirds, including European storm-petrels, European shags, lesser black-backed gull, lesser and great black-backed gulls, and common terns. Ruddy turnstones visit in winter.Government

Governors of Scilly

Historically, the Isles of Scilly were primarily ruled by a Proprietor/Governor. The governor was a military Commission (document), commission made by the monarch in consultation with the Admiralty (United Kingdom), Admiralty in recognition of the islands' strategic position. The office of Governor was pre-eminent in military law but not in Civil law (common law), civil law, where the Magistrates' court (England and Wales), magistracy was vested in the Proprietor, who had a leasehold from theDuchy of Cornwall

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important difference between "sovereign ...

of the islands' land area. Usually the Proprietor served as Governor, although, according to Robert Heath (mathematician), Robert Heath, a Major Bennett was Governor for a short time before Proprietor Francis Godolphin, 2nd Earl of Godolphin was commissioned on 7 July 1733. The Proprietor/Governor was non-resident, delegating the military functions to a Lieutenant-Governor and the civil functions to a Council of twelve residents.

An early governor of Scilly was Thomas Godolphin, whose son Francis Godolphin (1540–1608), Francis received a lease on the Isles in 1568. The Godolphins and their Osborne relatives held this position until 1831, when George Osborne, 6th Duke of Leeds, George Osbourne, 6th Duke of Leeds surrendered the lease to the islands, with them then returning to direct rule from the Duchy of Cornwall

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important difference between "sovereign ...

. In 1834 Augustus Smith (politician), Augustus Smith acquired the lease from the Duchy for £20,000, and created the title ''Lord Proprietor of the Isles of Scilly''. The lease remained in his family until it expired for most of the Isles in 1920 when ownership reverted to back to the Duchy of Cornwall. Today, the Dorrien-Smith family still holds the lease for the island of Tresco Tresco may refer to:

* Tresco, Elizabeth Bay, a historic residence in New South Wales, Australia

* Tresco, Isles of Scilly, an island off Cornwall, England, United Kingdom

* Tresco, Victoria, a town in Victoria, Australia

* a nickname referring t ...

.

National government

Politically, the islands are part of England, one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. They are represented in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, UK Parliament as part of the St Ives (UK Parliament constituency), St Ives constituency. As part of the United Kingdom, the islands Brexit, were part of the European Union and were represented in the European Parliament as part of the multi-member South West England (European Parliament constituency), South West England constituency.Local government

Historically, the Isles of Scilly were administered as one of the hundreds of Cornwall, although the Cornwall quarter sessions had limited jurisdiction there. For judicial purposes, High Sheriff, shrievalty purposes, and Lord Lieutenant, lieutenancy purposes, the Isles of Scilly are "deemed to form part of the county of Cornwall". The Local Government Act 1888 allowed the Local Government Board to establish in the Isles of Scilly "councils and other local authorities separate from those of the county of Cornwall"... "for the application to the islands of any act touching local government." Accordingly, in 1890 the ''Isles of Scilly Rural District Council'' (the RDC) was formed as a ''sui generis'' Unitary Authority, unitary authority, outside the administrative county of Cornwall. Cornwall County Council provided some services to the Isles, for which the RDC made financial contributions. The Isles of Scilly Order 1930 granted the council the "powers, duties and liabilities" of acounty council

A county council is the elected administrative body governing an area known as a county. This term has slightly different meanings in different countries.

Australia

In the Australian state of New South Wales, county councils are special purpose ...

. Section 265 of the Local Government Act 1972 allowed for the continued existence of the RDC, but renamed as the ''Council of the Isles of Scilly''. This unusual status also means that much administrative law (for example relating to the functions of local authorities, the health service and other public bodies) that applies in the rest of England applies in modified form in the islands.

With a total population of just over 2,000, the council represents fewer inhabitants than many English parish councils in England, parish councils, and is by far the smallest English unitary council. , 130 people are employed full-time equivalent, full-time by the council to provide local services (including water supply and air traffic control). These numbers are significant, in that almost 10% of the adult population of the islands is directly linked to the council, as an employee or a councillor.

The Council consists of 16 elected councillors, 12 of whom are returned by the Wards and electoral divisions of the United Kingdom, ward of St Mary's, and one from each of four "off-island" wards (St Martin's, St Agnes, Bryher, and Tresco). The 2021 Council of the Isles of Scilly election, latest elections took place on 6 May 2021; all 15 councillors elected were Independent (politician), independents. One seat, for the island of Bryher, received no nominations and remained vacant until filled by a further independent councillor on 28 May.

The council is headquartered at Town Hall, by The Parade park in Hugh Town

Hugh Town ( or ) is the largest settlement on the Isles of Scilly and its administrative centre. The town is situated on the island of St Mary's, Isles of Scilly, St Mary's, the largest and most populous island in the archipelago, and is located ...

, and also performs the administrative functions of the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, AONB Partnership and the Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority.

Some aspects of local government are shared with Cornwall, including Healthcare in Cornwall, health, and the Council of the Isles of Scilly together with Cornwall Council form a Local Enterprise Partnership. In July 2015 a devolution in the United Kingdom, devolution deal was announced by the Second Cameron ministry, government under which Cornwall Council and the Council of the Isles of Scilly are to create a plan to bring health and social care services together under local control. The Local Enterprise Partnership is also to be bolstered.

Flags

Two flags are used to represent Scilly, The Scillonian Cross, selected by readers of ''Scilly News'' in a 2002 vote and then registered with the Flag Institute as the flag of the islands, and the flag of the Council of the Isles of Scilly, which incorporates the council's logo and represents the council. An adapted version of the old Board of Ordnance flag has also been used, after it was left behind when munitions were removed from the isles. The "Cornish Ensign" (the Cornish cross with the Union Jack in the canton) has also been used.Emergency services

The Isles of Scilly form part of the Devon and Cornwall Police force area. There is a police station inHugh Town

Hugh Town ( or ) is the largest settlement on the Isles of Scilly and its administrative centre. The town is situated on the island of St Mary's, Isles of Scilly, St Mary's, the largest and most populous island in the archipelago, and is located ...

.

The Cornwall Air Ambulance helicopter provides cover to the islands.

The islands have their own independent fire brigade – the Isles of Scilly Fire and Rescue Service – which is staffed entirely by retained firefighters on all the inhabited islands.

The emergency ambulance service is provided by the South Western Ambulance Service with full-time paramedics employed to cover the islands working with Ambulance attendant, emergency care attendants.

Administration

The Isles of Scilly altogether is a Districts of England, local government district, administered by a sui generis Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority, Council of the Isles of Scilly, which is independent from Cornwall Council.Education

Education is available on the islands up to age 16. There is one school, the Five Islands Academy, which provides primary schooling at sites on St Agnes, St Mary's, St Martin's and Tresco, and secondary schooling at a site on St Mary's, with secondary students from outside St Mary's living at a school boarding house (Mundesley House) during the week. Sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds are entitled to a free sixth form place at a state school or sixth form college on the mainland, and are provided with free flights and a grant towards accommodation.

Education is available on the islands up to age 16. There is one school, the Five Islands Academy, which provides primary schooling at sites on St Agnes, St Mary's, St Martin's and Tresco, and secondary schooling at a site on St Mary's, with secondary students from outside St Mary's living at a school boarding house (Mundesley House) during the week. Sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds are entitled to a free sixth form place at a state school or sixth form college on the mainland, and are provided with free flights and a grant towards accommodation.

Economy

Historical context

Since the mid-18th century the Scillonian economy has relied on trade with the mainland and beyond as a means of sustaining its population. Over the years the nature of this trade has varied, due to wider economic and political factors that have seen the rise and fall of industries, such as kelp harvesting, harbour pilot, pilotage, smuggling, fishing, shipbuilding and, latterly floriculture, flower farming. In a 1987 study of the Scillonian economy, Neate found that many farms on the islands were struggling to remain profitable due to increasing costs and strong competition from overseas producers, with resulting diversification into tourism. Statistics suggest that agriculture on the islands now represents less than 2% of all employment.''Isles of Scilly Integrated Area Plan 2001–2004'', Isles of Scilly Partnership 2001Tourism

Today, tourism is estimated to account for 85% of the islands' income. The islands have been successful in attracting this investment due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient co-ordination of tourism providers and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities.''Isles of Scilly Local Plan: A 2020 Vision'', Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2004''Isles of Scilly 2004, imagine...'', Isles of Scilly Tourist Board, 2004

The islands' economy is highly dependent on tourism, even by the standards of other island communities. "The concentration [on] a small number of sectors is typical of most similarly sized UK island communities. However, it is the degree of concentration, which is distinctive along with the overall importance of tourism within the economy as a whole and the very limited manufacturing base that stands out".

Tourism is also a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation, and the lower number of tourists in winter results in a significant constriction of the islands' commercial activities. However, the tourist season benefits from an extended period of business in October when many birding, birdwatchers ("twitchers") arrive.

Today, tourism is estimated to account for 85% of the islands' income. The islands have been successful in attracting this investment due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient co-ordination of tourism providers and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities.''Isles of Scilly Local Plan: A 2020 Vision'', Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2004''Isles of Scilly 2004, imagine...'', Isles of Scilly Tourist Board, 2004

The islands' economy is highly dependent on tourism, even by the standards of other island communities. "The concentration [on] a small number of sectors is typical of most similarly sized UK island communities. However, it is the degree of concentration, which is distinctive along with the overall importance of tourism within the economy as a whole and the very limited manufacturing base that stands out".

Tourism is also a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation, and the lower number of tourists in winter results in a significant constriction of the islands' commercial activities. However, the tourist season benefits from an extended period of business in October when many birding, birdwatchers ("twitchers") arrive.

Ornithology

Because of its position, Scilly is the first landing for many migrant birds, including extreme rarities from North America and Siberia. Scilly is situated far into the Atlantic Ocean, so many American vagrant birds will make first European landfall in the archipelago. If an extremely rare bird turns up, the island will see a significant increase in numbers of birdwatchers. This type of birding, chasing after rare birds, is called "Birdwatching#Birding, birdwatching and twitching, twitching". The islands are home to ornithologist Will Wagstaff.Employment

The predominance of tourism means that "tourism is by far the main sector throughout each of the individual islands, in terms of employment... [and] this is much greater than other remote and rural areas in the United Kingdom". Tourism accounts for approximately 63% of all employment. Businesses dependent on tourism, with the exception of a few hotels, tend to be small enterprises typically employing fewer than four people; many of these are family run, suggesting an entrepreneurial culture among the local population. However, much of the work generated by this, with the exception of management, is low skilled and thus poorly paid, especially for those involved in cleaning, catering and retail. Because of the seasonality of tourism, many jobs on the islands are seasonal and part-time, so work cannot be guaranteed throughout the year. Some islanders take up other temporary jobs 'out of season' to compensate for this. Due to a lack of local casual labour at peak holiday times, many of the larger employers accommodate guest workers.Taxation

The islands were not subject to Income Tax, income tax until 1954, and there was no motor vehicle excise duty levied until 1971. The Council Tax is set by the Local Authority in order to meet their budget requirements. The Valuation Office Agency values properties for the purpose of council tax. The amount of council tax paid depends on the band of the property as shown below. The Valuation (finance), valuation is based on what the property would have been worth in 1991. Source 1Council of the Isles of Scilly

/u> Source 2

Isles of Scilly Council Tax

/u>

Transport

St Mary's is the only island with a significant road network and the only island with classified roads - the A3110, A3111 and A3112. St Agnes and St Martin's also have public highways adopted by the local authority. In 2005 there were 619 registered vehicles on the island. The island also has taxicab, taxis and a tour bus. Vehicles on the islands are exempt from annual MOT tests.

Fixed-wing aircraft services, operated by Isles of Scilly Skybus, operate from Land's End Airport, Land's End, Newquay Cornwall Airport, Newquay and Exeter International Airport, Exeter to St Mary's Airport. A scheduled helicopter service has operated from a new Penzance Heliport to both St Mary's Airport, Isles of Scilly, St Mary's Airport and Tresco Heliport since 2020. The helicopter is the only direct flight to the island of

St Mary's is the only island with a significant road network and the only island with classified roads - the A3110, A3111 and A3112. St Agnes and St Martin's also have public highways adopted by the local authority. In 2005 there were 619 registered vehicles on the island. The island also has taxicab, taxis and a tour bus. Vehicles on the islands are exempt from annual MOT tests.

Fixed-wing aircraft services, operated by Isles of Scilly Skybus, operate from Land's End Airport, Land's End, Newquay Cornwall Airport, Newquay and Exeter International Airport, Exeter to St Mary's Airport. A scheduled helicopter service has operated from a new Penzance Heliport to both St Mary's Airport, Isles of Scilly, St Mary's Airport and Tresco Heliport since 2020. The helicopter is the only direct flight to the island of Tresco Tresco may refer to:

* Tresco, Elizabeth Bay, a historic residence in New South Wales, Australia

* Tresco, Isles of Scilly, an island off Cornwall, England, United Kingdom

* Tresco, Victoria, a town in Victoria, Australia

* a nickname referring t ...

.

By sea, the Isles of Scilly Steamship Company provides a passenger and cargo service from Penzance to St Mary's, which is currently operated by the ''Scillonian III'' passenger ferry, supported until summer 2017 by the ''Gry Maritha'' cargo vessel and now by the ''Mali Rose''. The other islands are linked to St. Mary's by a network of inter-island launch (boat), launches. St Mary's Harbour is the principal harbour of the Isles of Scilly, and is located in Hugh Town.

Tenure

A majority of the freehold (law), freehold land of the islands is the property of theDuchy of Cornwall

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important difference between "sovereign ...

, with a few exceptions, including much of Hugh Town

Hugh Town ( or ) is the largest settlement on the Isles of Scilly and its administrative centre. The town is situated on the island of St Mary's, Isles of Scilly, St Mary's, the largest and most populous island in the archipelago, and is located ...

on St Mary's, which was sold to the inhabitants in 1949. The duchy also holds as duchy property, part of the duchy's landholding. All the uninhabited islands, islets and rocks and much of the untenanted land on the inhabited islands is managed by the Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust, which leases these lands from the Duchy for the rent of one daffodil per year.

Limited housing availability is a contentious yet critical issue for the Isles of Scilly, especially as it affects the feasibility of residency on the islands. Few properties are privately owned, with many units being let by the Duchy of Cornwall, the council and a few by housing associations. The management of these subsequently affects the possibility of residency on the islands.Martin D, 'Heaven and Hell', in ''Inside Housing'', 31 October 2004