Schistosoma Mansoni on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A paired couple of ''Schistosoma mansoni''.

''Schistosoma mansoni'' is a water-borne parasite of humans, and belongs to the group of blood flukes (''Schistosoma''). The adult lives in the blood vessels ( mesenteric veins) near the human intestine. It causes intestinal

PDF

In Africa, ''B. glabratra'', ''B. pfeifferi'', ''B. choanomphala'' and '' B. sudanica'' act as the hosts; but in Egypt, the main snail host is ''B. alexandrina''. Miracidia directly penetrate the soft tissue of snail. Inside the snail, they lose their cilia and develop into mother sporocysts. The sporocysts rapidly multiply by asexual reproduction, each forming numerous daughter sporocysts. The daughter sporocysts move to the liver and gonads of the snail, where they undergo further growth. Within 2–4 weeks, they undergo metamorphosis and give rise to fork-tailed cercariae. Stimulated by light, hundreds of cercariae penetrate out of the snail into water.

.

Disease info at CDCSpecies profile at Animal Diversity WebProfile at WormBase

{{Authority control Diplostomida Parasitic helminths of humans Waterborne diseases Animals described in 1907 Helminthiases

schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis, also known as snail fever, bilharzia, and Katayama fever is a neglected tropical helminthiasis, disease caused by parasitism, parasitic Schistosoma, flatworms called schistosomes. It affects both humans and animals. It affects ...

(similar to '' S. japonicum'', '' S. mekongi'', ''S. guineensis'', and '' S. intercalatum''). Clinical symptoms are caused by the eggs. As the leading cause of schistosomiasis in the world, it is the most prevalent parasite in humans. It is classified as a neglected tropical disease

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a diverse group of tropical infections that are common in low-income populations in developing regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. They are caused by a variety of pathogens, such as viruses, bacteri ...

. As of 2021, the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

reports that 251.4 million people have schistosomiasis and most of it is due to ''S. mansoni''. It is found in Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, Brazil, Venezuela and Suriname.

Unlike other flukes (trematodes

Trematoda is a class of flatworms known as trematodes, and commonly as flukes. They are obligate internal parasites with a complex life cycle requiring at least two hosts. The intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs, is a moll ...

) in which sexes are not separate (monoecious

Monoecy (; adj. monoecious ) is a sexual system in seed plants where separate male and female cones or flowers are present on the same plant. It is a monomorphic sexual system comparable with gynomonoecy, andromonoecy and trimonoecy, and contras ...

), schistosomes are unique in that adults are divided into males and females, thus, gonochoric. However, a permanent male-female pair, a condition called ''in copula,'' is required to become adults; for this, they are considered as hermaphrodites

A hermaphrodite () is a sexually reproducing organism that produces both male and female gametes. Animal species in which individuals are either male or female are gonochoric, which is the opposite of hermaphroditic.

The individuals of many ...

.

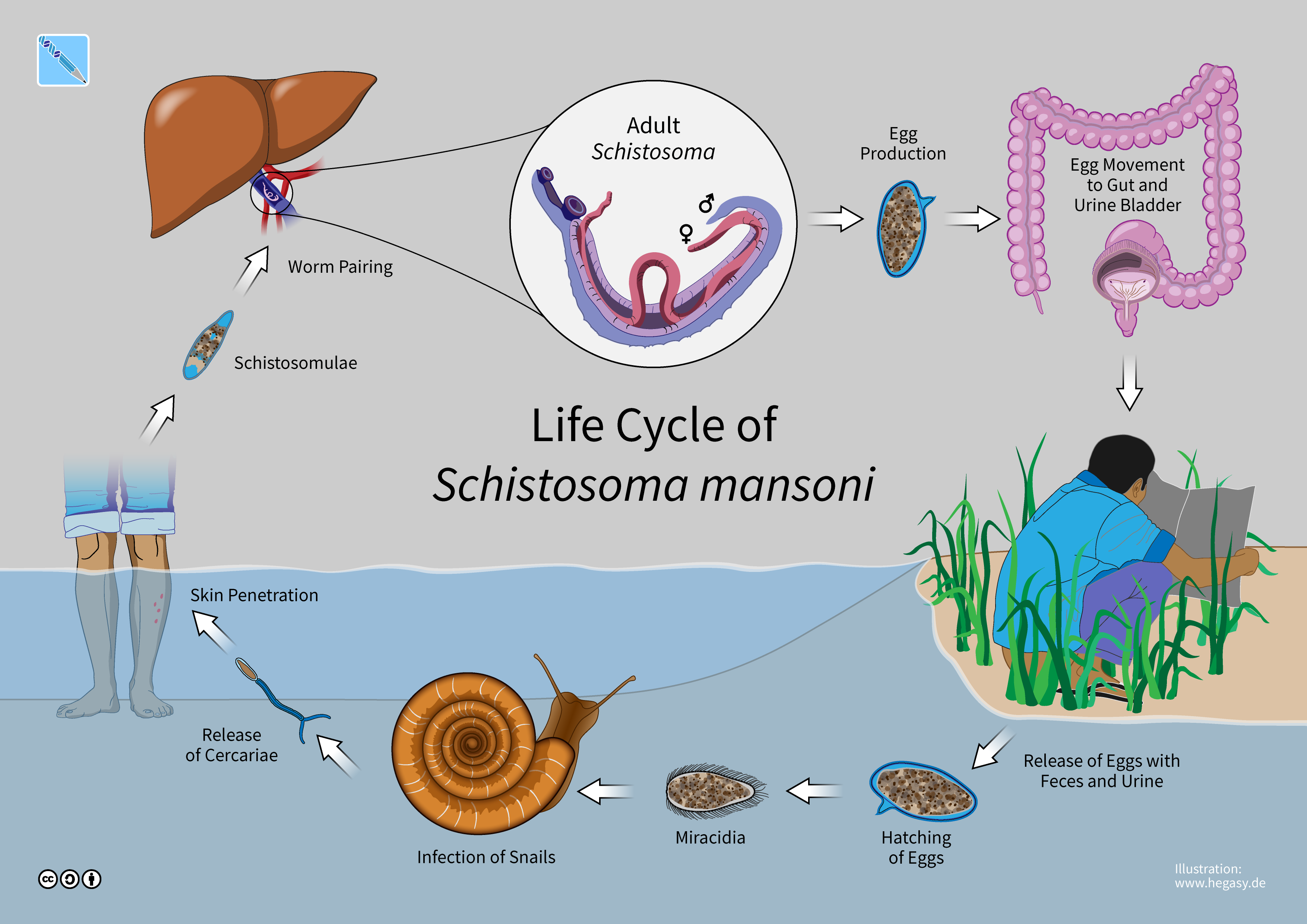

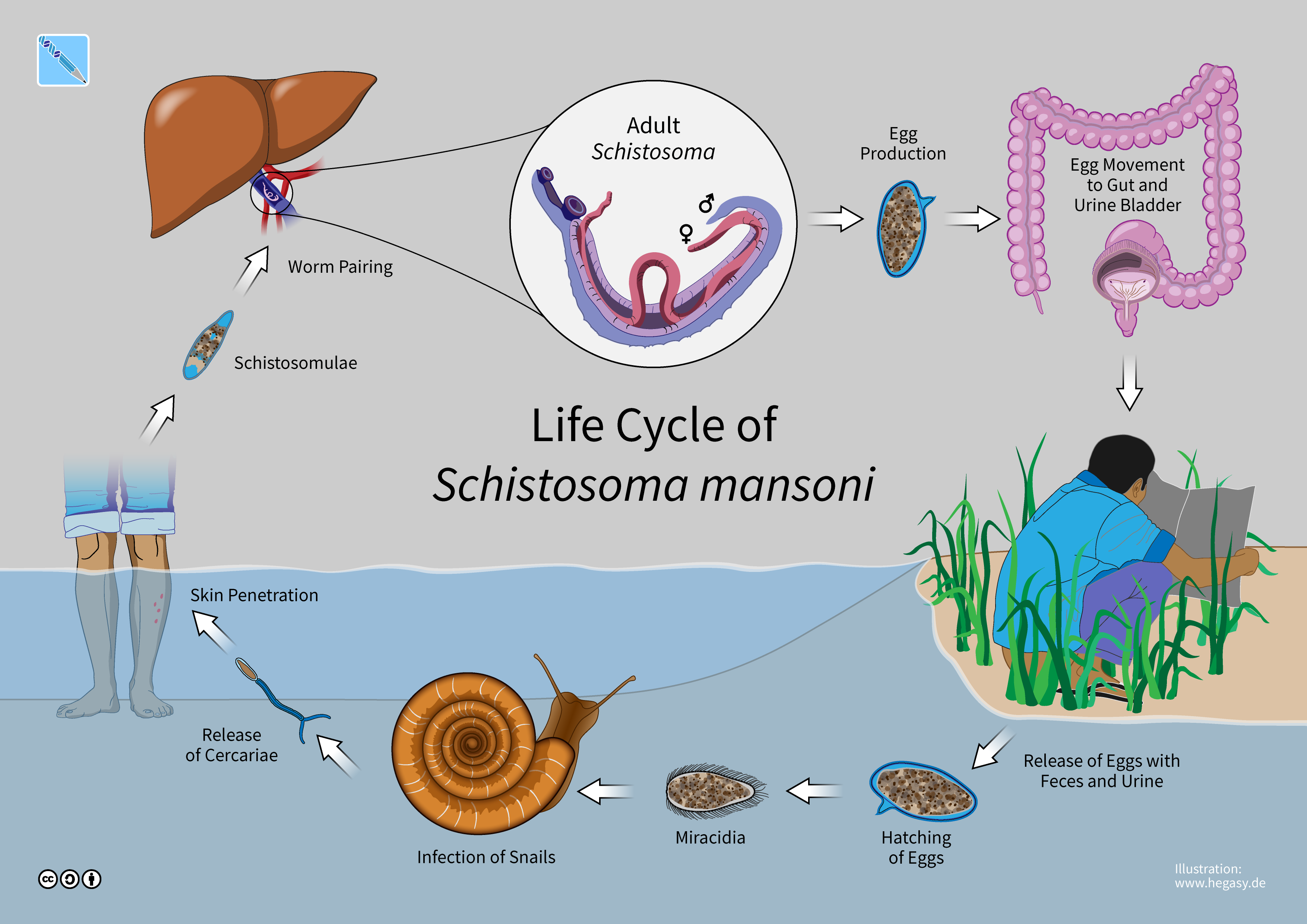

The life cycle of schistosomes includes two hosts: humans as definitive hosts, where the parasite undergoes sexual reproduction, and snails as intermediate hosts, where a series of asexual reproduction takes place. ''S. mansoni'' is transmitted through water, where freshwater snails of the genus '' Biomphalaria'' act as intermediate hosts. The larvae are able to live in water and infect the hosts by directly penetrating the skin. Prevention of infection is done by improved sanitation and killing the snails. Infection is treated with praziquantel

Praziquantel, sold under the brandname Biltricide among others, is a medication used to treat a number of types of parasitic worm infections in mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish. In humans specifically, it is used to treat schist ...

.

''S. mansoni'' was first noted by Theodor Maximillian Bilharz in Egypt in 1851, while discovering '' S. haematobium''. Sir Patrick Manson

Sir Patrick Manson (3 October 1844 – 9 April 1922) was a Scottish physician who made important discoveries in parasitology, and was a founder of the field of tropical medicine.

He graduated from the University of Aberdeen with degrees in Ma ...

identified it as unique species in 1902. Louis Westenra Sambon gave the name ''Schistosomum mansoni'' in 1907 in honour of Manson.

Structure

Adult

Schistosomes, unlike other trematodes, are long and cylindrical worms and aresexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

. The male ''S. mansoni'' is approximately 1 cm long (0.6–1.1 cm) and is 0.1 cm wide. It is white, and it has a funnel-shaped oral sucker at its anterior end followed by a second pediculated ventral sucker. The external part of the worm is composed of a double bilayer, which is continuously renewed as the outer layer, known as the membranocalyx, and is shed continuously. The tegument bears a large number of small tubercules. The suckers have small thorns in their inner part as well as in the buttons around them. The male genital apparatus is composed of six to nine testicular masses, situated dorsally. There is one deferent canal beginning at each testicle, which is connected to a single deferent that dilates into a reservatory, the seminal vesicle, located at the beginning of the gynaecophoric canal. The copula happens through the coaptation of the male and female genital orifices.

The female has a cylindrical body, longer and thinner than the male's (1.2 to 1.6 cm long by 0.016 cm wide). It has the general appearance of a roundworm. The female parasite is darker, and it looks gray. The darker color is due to the presence of a pigment (hemozoin

Haemozoin is a disposal product formed from the digestion of blood by some blood-feeding parasites. These hematophagy, hematophagous organisms such as malaria parasites (''Plasmodium spp.''), ''Rhodnius'' and ''Schistosoma'' digest haemoglobin an ...

) in its digestive tube. This pigment is derived from the digestion of blood. The ovary

The ovary () is a gonad in the female reproductive system that produces ova; when released, an ovum travels through the fallopian tube/ oviduct into the uterus. There is an ovary on the left and the right side of the body. The ovaries are end ...

is elongated and slightly lobulated and is located on the anterior half of the body. A short oviduct conducts to the ootype, which continues with the uterine tube. In this tube it is possible to find one to two eggs (rarely three to four) but only one egg is observed in the ootype at any one time. The genital pore opens ventrally. The posterior two-thirds of the body contains the vitelline glands and their winding canal, which unites with the oviduct

The oviduct in vertebrates is the passageway from an ovary. In human females, this is more usually known as the fallopian tube. The eggs travel along the oviduct. These eggs will either be fertilized by spermatozoa to become a zygote, or will dege ...

a little before it reaches the ootype.

The digestive tube begins at the anterior extremity of the worm, at the bottom of the oral sucker. The digestive tube is composed of an esophagus

The esophagus (American English), oesophagus (British English), or œsophagus (Œ, archaic spelling) (American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, see spelling difference) all ; : ((o)e)(œ)sophagi or ((o)e)(œ)sophaguses), c ...

, which divides in two branches (right and left) and that reunite in a single cecum

The cecum ( caecum, ; plural ceca or caeca, ) is a pouch within the peritoneum that is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It is typically located on the right side of the body (the same side of the body as the appendix (a ...

. The intestines end blindly, meaning that there is no anus

In mammals, invertebrates and most fish, the anus (: anuses or ani; from Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is the external body orifice at the ''exit'' end of the digestive tract (bowel), i.e. the opposite end from the mouth. Its function is to facil ...

.

Sex

''S. mansoni'' and other schistosomes are the only flukes orflatworms

Platyhelminthes (from the Greek πλατύ, ''platy'', meaning "flat" and ἕλμινς (root: ἑλμινθ-), ''helminth-'', meaning "worm") is a phylum of relatively simple bilaterian, unsegmented, soft-bodied invertebrates commonly called ...

that exhibit sex separation as they exist as male and female individuals as in dioecious

Dioecy ( ; ; adj. dioecious, ) is a characteristic of certain species that have distinct unisexual individuals, each producing either male or female gametes, either directly (in animals) or indirectly (in seed plants). Dioecious reproduction is ...

animals. However, they are not truly dioecious since the adults live in permanent male-female pairs, a condition called ''in copula''. Although they can be physically separated, isolated females cannot grow into sexually-mature adults. ''In copula'' starts in the liver only after which they can move to their final habitation, the inferior mesenteric veins. Individual females cannot enter the mesenteric veins. Sex organs, the gonads, are also incompletely separated and are interdependent between sexes. An egg-making organ, the vitelline gland, does not develop in females in the absence of a male. Male gametes, spermatozoa, are present in the oviduct. In males, there are rudimentary ovaries, oviduct, and oocytes (developing female gametes), as well as vitelline cells. Males also possess the genes for hermaphroditism in flukes. Thus, they are technically hermaphrodites.

Eggs

The eggs are oval-shaped, measuring 115–175 μm long and 45–47 μm wide, and ~150 μm diameter on average. They have pointed spines towards the broader base on one side, i.e. lateral spines. This is an important diagnostic tool because co-infection with ''S. haematobium'' (having terminal-spined eggs) is common, and they are hard to distinguish. When the eggs are released into the water, a lot of them are immature and unfertilised so that they do not hatch. When the eggs are larger than 160 μm in diameter, they also fail to hatch.Larva

The miracidium (from the Greek word μειράκιον, ''meirakion'', meaning youth) is pear-shaped, and gradually elongates as it ages. It measures about 136 μm long and 55 μm wide. The body is covered by anucleate epidermal plates separated by epidermal ridges. The epidermal cells give off numerous hair-likecilia

The cilium (: cilia; ; in Medieval Latin and in anatomy, ''cilium'') is a short hair-like membrane protrusion from many types of eukaryotic cell. (Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea.) The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike proj ...

on the body surface. There are 17–22 epidermal cells. Epidermal plate is absent only at the extreme anterior called apical papilla, or terebratorium, which contains numerous sensory organelles. Its internal body is almost fully filled with glycogen particles and vesicles.

The cercaria has a characteristic bifurcated tail, classically called furcae (Latin for fork); hence, the name (derived from a Greek word κέρκος, ''kerkos'', meaning tail). The tail is highly flexible and its beating propels the cercaria in water. It is about 0.2 mm long and 47 μm wide, somewhat loosely attached to the main body. The body is pear-shaped and measures 0.24 mm in length and 0.1 mm in width. Its tegument is fully covered with spine. A conspicuous oral sucker is at the apex. As a non-feeding larva, there are no elaborate digestive organs, only oesophagus

The esophagus (American English), oesophagus (British English), or œsophagus ( archaic spelling) ( see spelling difference) all ; : ((o)e)(œ)sophagi or ((o)e)(œ)sophaguses), colloquially known also as the food pipe, food tube, or gullet, ...

is distinct. There are three pairs of mucin glands connected to laterally to the oral sucker at the region of the ventral sucker.

Physiology

Feeding and nutrition

Developing ''Schistosoma mansoni'' worms that have infected their definitive hosts, prior to the sexual pairing of males and females, require a nutrient source in order to properly develop from cercariae to adults. The developing parasites lyse host red blood cells to gain access to nutrients and also makes its own fungi from its waste it is hard to detect; the hemoglobin and amino acids the blood cells contain can be used by the worm to form proteins. While hemoglobin is digested intracellularly, initiated by salivary gland enzymes, iron waste products cannot be used by the worms, and are typically discarded via regurgitation. Kasschau et al. (1995) tested the effect of temperature and pH on the ability of developing ''S. mansoni'' to lyse red blood cells. The researchers found that the parasites were best able to destroy red blood cells for their nutrients at a pH of 5.1 and a temperature of 37 °C.Locomotion

''Schistosoma mansoni'' is locomotive in primarily two stages of its life cycle: as cercariae swimming freely through a body of freshwater to locate the epidermis of their human hosts, and as developing and fully-fledged adults, migrating throughout their primary host upon infection. Cercariae are attracted to the presence of fatty acids on the skin of their definitive host, and the parasite responds to changes in light and temperature in their freshwater medium to navigate towards the skin. Ressurreicao et al. (2015) tested the roles of various protein kinases in the ability of the parasite to navigate its medium and locate a penetrable host surface. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and protein kinase C both respond to changes in medium temperature and light levels, and the stimulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, associated with recognition of parasite host surface, results in a glandular secretion that deteriorates the host epidermis, and allows the parasite to burrow into its host. The parasite's nervous system contains bilobed ganglia and several nerve cords which splay out to every surface of the body; serotonin is a transmitter distributed widely throughout the nervous system and plays an important role in nervous reception, and stimulating mobility.Life cycle

Intermediate host

After the eggs of the human-dwelling parasite are emitted in the faeces and into the water, the ripe miracidium hatches out of the egg. The hatching happens in response to temperature, light and dilution of faeces with water. The miracidium searches for a suitablefreshwater snail

Freshwater snails are gastropod mollusks that live in fresh water. There are many different families. They are found throughout the world in various habitats, ranging from ephemeral pools to the largest lakes, and from small seeps and springs t ...

belonging to the genus ''Biomphalaria''. In South America, the principal intermediate host is '' Biomphalaria glabrata'', while '' B. straminea'' and '' B. tenagophila'' are less common. A land snail ''Achatina fulica

''Lissachatina fulica'' is a species of large land snail that belongs in the subfamily Achatininae of the family Achatinidae. It is also known as the giant African land snail. It shares the common name "giant African snail" with other species of ...

'' was reported in 2010 to act as a host in Venezuela. Libora M., Morales G., Carmen S., Isbelia S. & Luz A. P. (2010). "Primer hallazgo en Venezuela de huevos de ''Schistosoma mansoni'' y de otros helmintos de interés en salud pública, presentes en heces y secreción mucosa del molusco terrestre ''Achatina fulica'' (Bowdich, 1822). irst finding in Venezuela of ''Schistosoma mansoni'' eggs and other helminths of interest in public health found in faeces and mucous secretion of the mollusc ''Achatina fulica'' (Bowdich, 1822) '' Zootecnia Tropical'' 28: 383–394In Africa, ''B. glabratra'', ''B. pfeifferi'', ''B. choanomphala'' and '' B. sudanica'' act as the hosts; but in Egypt, the main snail host is ''B. alexandrina''. Miracidia directly penetrate the soft tissue of snail. Inside the snail, they lose their cilia and develop into mother sporocysts. The sporocysts rapidly multiply by asexual reproduction, each forming numerous daughter sporocysts. The daughter sporocysts move to the liver and gonads of the snail, where they undergo further growth. Within 2–4 weeks, they undergo metamorphosis and give rise to fork-tailed cercariae. Stimulated by light, hundreds of cercariae penetrate out of the snail into water.

Definitive host

The cercaria emerge from the snail during daylight and they propel themselves in water with the aid of their bifurcated tail, actively seeking out their final host. In water, they can live for up to 12 hours, and their maximum infectivity is between 1 and 9 hours after emergence. When they recognise humanskin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

, they penetrate it within a very short time. This occurs in three stages, an initial attachment to the skin, followed by the creeping over the skin searching for a suitable penetration site, often a hair follicle

The hair follicle is an organ found in mammalian skin. It resides in the dermal layer of the skin and is made up of 20 different cell types, each with distinct functions. The hair follicle regulates hair growth via a complex interaction betwee ...

, and finally penetration of the skin into the epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermal layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

using cytolytic

Cytolysis, or osmotic lysis, occurs when a cell bursts due to an osmotic imbalance that has caused excess water to diffuse into the cell. Water can enter the cell by diffusion through the cell membrane or through selective membrane channels ...

secretions from the cercarial post-acetabular, then pre-acetabular glands

A gland is a Cell (biology), cell or an Organ (biology), organ in an animal's body that produces and secretes different substances that the organism needs, either into the bloodstream or into a body cavity or outer surface. A gland may also funct ...

. On penetration, the head of the cercaria transforms into an endoparasitic larva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

, the schistosomule. Each schistosomule spends a few days in the skin and then enters the circulation starting at the dermal lymphatics and venule

A venule is a very small vein in the microcirculation that allows blood to return from the capillary beds to drain into the venous system via increasingly larger veins. Post-capillary venules are the smallest of the veins with a diameter of ...

s. Here, they feed on blood, regurgitating the haem as hemozoin

Haemozoin is a disposal product formed from the digestion of blood by some blood-feeding parasites. These hematophagy, hematophagous organisms such as malaria parasites (''Plasmodium spp.''), ''Rhodnius'' and ''Schistosoma'' digest haemoglobin an ...

. The schistosomule migrates to the lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of the heart. Their function in the respiratory syste ...

(5–7 days post-penetration) and then moves via circulation through the left side of the heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

to the hepatoportal circulation (>15 days) where, if it meets a partner of the opposite sex, it develops into a sexually mature adult and the pair migrate to the mesenteric veins. Such pairings are monogamous

Monogamy ( ) is a relationship of two individuals in which they form a mutual and exclusive intimate partnership. Having only one partner at any one time, whether for life or serial monogamy, contrasts with various forms of non-monogamy (e.g. ...

.

Male schistosomes undergo normal maturation and morphological development in the presence or absence of a female, although behavioural, physiological and antigenic differences between males from single-sex, as opposed to bisex, infections have been reported. On the other hand, female schistosomes do not mature without a male. Female schistosomes from single-sex infections are underdeveloped and exhibit an immature reproductive system. Although the maturation of the female worm seems to be dependent on the presence of the mature male, the stimuli for female growth and for reproductive development seem to be independent from each other.

The adult female worm resides within the adult male worm's gynaecophoric canal, which is a modification of the ventral surface of the male, forming a groove. The paired worms move against the flow of blood to their final niche in the mesenteric circulation, where they begin egg production (>32 days). The ''S. mansoni'' parasites are found predominantly in the small inferior mesenteric blood vessels surrounding the large intestine and caecal region of the host. Each female lays approximately 300 eggs a day (one egg every 4.8 minutes), which are deposited on the endothelial

The endothelium (: endothelia) is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the res ...

lining of the venous capillary

A capillary is a small blood vessel, from 5 to 10 micrometres in diameter, and is part of the microcirculation system. Capillaries are microvessels and the smallest blood vessels in the body. They are composed of only the tunica intima (the inn ...

walls. Most of the body mass of female schistosomes is devoted to the reproductive system. The female converts the equivalent of almost her own body dry weight into eggs each day. The eggs move into the lumen of the host's intestines

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. ...

and are released into the environment with the faeces.

Genome

''Schistosoma mansoni'' has eight pairs ofchromosomes

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most importa ...

(2n = 16): seven autosomal pairs and one sex pair. The female schistosome is heterogametic, or ZW, and the male is homogametic, or ZZ. Sex is determined in the zygote

A zygote (; , ) is a eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes.

The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individ ...

by a chromosomal mechanism. The genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

is approximately 270 MB with a GC content of 34%, 4–8% highly repetitive sequence, 32–36% middle repetitive sequence and 60% single copy sequence. Numerous highly or moderately repetitive elements are identified, with at least 30% repetitive DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

. Chromosomes range in size from 18 to 73 MB and can be distinguished by size, shape, and C banding.

In 2000, the first BAC library of Schistosome was constructed. In June 2003, a ~5x whole genome shotgun sequencing

In genetics, shotgun sequencing is a method used for sequencing random DNA strands. It is named by analogy with the rapidly expanding, quasi-random shot grouping of a shotgun.

The Sanger sequencing#Method, chain-termination method of DNA sequencin ...

project was initiated at the Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Sanger Institute, previously known as The Sanger Centre and Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, is a non-profit organisation, non-profit British genomics and genetics research institute, primarily funded by the Wellcome Trust.

It is l ...

. Also in 2003, 163,000 ESTs (expressed sequence tag

In genetics, an expressed sequence tag (EST) is a short sub-sequence of a cDNA sequence. ESTs may be used to identify gene transcripts, and were instrumental in gene discovery and in gene-sequence determination. The identification of ESTs has pro ...

s) were generated (by a consortium

A consortium () is an association of two or more individuals, companies, organizations, or governments (or any combination of these entities) with the objective of participating in a common activity or pooling their resources for achieving a ...

headed by the University of São Paulo

The Universidade de São Paulo (, USP) is a public research university in the Brazilian state of São Paulo, and the largest public university in Brazil.

The university was founded on 25 January 1934, regrouping already existing schools in ...

) from six selected developmental stages of this parasite, resulting in 31,000 assembled sequences and an estimated 92% of the 14,000-gene complement.

In 2009 the genomes of both ''S. mansoni'' and ''S. japonicum'' were published, with each describing 11,809 and 13,469 genes, respectively. ''S. mansoni'' genome has increased protease families and deficiencies in lipid anabolism; which are attributed to its parasitic adaptation. Proteases included the invadolysin (host penetration) and cathepsin (blood-feeding) gene families.

In 2012, an improved version of the ''S. mansoni'' genome was published, which consisted of only 885 scaffolds and more than 81% of the bases organised into chromosomes.

In 2019, Ittiprasert, Brindley and colleagues employed programmed CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of the gene encoding the T2 ribonuclease of the egg of ''Schistosoma mansoni'', advancing functional genomics and reverse genetics in the study of schistosomes, and platyhelminths generally Pathology

Schistosome eggs, which may become lodged within the host's tissues, are the major cause of pathology in schistosomiasis. Some of the deposited eggs reach the outside environment by passing through the wall of the intestine; the rest are swept into the circulation and are filtered out in the periportal tracts of the liver, resulting in periportal fibrosis. Onset of egg laying in humans is sometimes associated with an onset of fever (Katayama fever). This "acute schistosomiasis" is not, however, as important as the chronic forms of the disease. For ''S. mansoni'' and '' S. japonicum'', these are "intestinal" and "hepatic schistosomiasis", associated with formation of granulomas around trapped eggs lodged in the intestinal wall or in the liver, respectively. The hepatic form of the disease is the most important, granulomas here giving rise tofibrosis

Fibrosis, also known as fibrotic scarring, is the development of fibrous connective tissue in response to an injury. Fibrosis can be a normal connective tissue deposition or excessive tissue deposition caused by a disease.

Repeated injuries, ch ...

of the liver and hepatosplenomegaly in severe cases. Symptoms and signs depend on the number and location of eggs trapped in the tissues. Initially, the inflammatory reaction is readily reversible. In the latter stages of the disease, the pathology is associated with collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

deposition and fibrosis, resulting in organ damage that may be only partially reversible.

Granuloma formation is initiated by antigens secreted by the miracidium through microscopic pores within the rigid egg shell, and the immune response to granuloma, rather than the direct action of egg antigens, causes the symptoms. The granulomas formed around the eggs impair blood flow in the liver and, as a consequence, induce portal hypertension

Portal hypertension is defined as increased portal venous pressure, with a hepatic venous pressure gradient greater than 5 mmHg. Normal portal pressure is 1–4 mmHg; clinically insignificant portal hypertension is present at portal pressures 5� ...

. With time, collateral circulation

Collateral circulation is the alternate Circulatory system, circulation around a blocked blood vessel, artery or vein via another path, such as nearby minor vessels. It may occur via preexisting vascular redundancy (analogous to redundancy (engi ...

is formed and the eggs disseminate into the lungs, where they cause more granulomas, pulmonary arteritis and, later, cor pulmonale. A contributory factor to portal hypertension is Symmers' fibrosis, which develops around branches of the portal veins. This fibrosis occurs only many years after the infection and is presumed to be caused in part by soluble egg antigens and various immune cells that react to them.

Recent research has shown that granuloma size is consistent with levels of IL-13, which plays a prominent role in granuloma formation and granuloma size. IL-13 receptor α 2 (IL-13Rα2) binds IL-13 with high affinity and blocks the effects of IL-13. Thus, this receptor is essential in preventing the progression of schistosomiasis from the acute to the chronic (and deadly) stage of disease. Synthetic IL-13Rα2 given to mice has resulted in significant decreases in granuloma size, implicating IL-13Rα2 as an important target in schistosomiasis.

''S. mansoni'' infection often occurs alongside those of viral hepatitis, either hepatitis B virus

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a partially double-stranded DNA virus, a species of the genus '' Orthohepadnavirus'' and a member of the '' Hepadnaviridae'' family of viruses. This virus causes the disease hepatitis B.

Classification

Hepatitis B ...

(HBV) or hepatitis C virus

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a small (55–65 nm in size), enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus of the family ''Flaviviridae''. The hepatitis C virus is the cause of hepatitis C and some cancers such as liver cancer ( hepatoc ...

(HCV). This is due to high prevalence of schistosomiasis in areas where chronic viral hepatitis is prevalent. One important factor was the development of large reservoir of infection due to extensive schistosomiasis control programs that used intravenously

Intravenous therapy (abbreviated as IV therapy) is a medical technique that administers fluids, medications and nutrients directly into a person's vein. The intravenous route of administration is commonly used for rehydration or to provide nutr ...

administered tartar emetic since the 1960s. Co-infection is known to cause earlier liver deterioration and more severe illness.

Evasion of host immunity

Adult and larval worms migrate through the host's blood circulation avoiding the host's immune system. The worms have many tools that help in this evasion, including the tegument, antioxidant proteins, and defenses against host membrane attack complex (MAC). The tegument coats the worm and acts as a physical barrier to host antibodies and complement. Host immune defenses are capable of producing superoxide, but these are counterattacked by antioxidant proteins produced by the parasite. Schistosomes have four superoxide dismutases, and levels of these proteins increase as the schistosome grows. Antioxidant pathways were first recognised as a chokepoints for schistosomes, and later extended to other trematodes and cestodes. Targeting of this pathway with different inhibitors of the central antioxidant enzyme thioredoxin glutathione reductase (TGR) results in reduced viability of worms. Decay accelerating factor (DAF) protein is present on the parasite tegument and protects host cells by blocking formation of MAC. In addition, schistosomes have six homologues of human CD59 which are strong inhibitors of MAC.Diagnosis

The presence of ''S. mansoni'' is detected by microscopic examination of parasite eggs in stool. A staining method called Kato-Katz technique is used for stool examination. It involvesmethylene blue

Methylthioninium chloride, commonly called methylene blue, is a salt used as a dye and as a medication. As a medication, it is mainly used to treat methemoglobinemia. It has previously been used for treating cyanide poisoning and urinary trac ...

-stained cellophane

Cellophane is a thin, transparent sheet made of regenerated cellulose. Its low permeability to air, oils, greases, bacteria, and liquid water makes it useful for food packaging. Cellophane is highly permeable to water vapour, but may be coate ...

soaked in glycerine or glass slides. A costlier technique called formalin-ether concentration technique (FECT) is often used in combination with the direct faecal smear for higher accuracy. Serological

Serology is the scientific study of serum and other body fluids. In practice, the term usually refers to the diagnostic identification of antibodies in the serum. Such antibodies are typically formed in response to an infection (against a given mi ...

and immunological tests are also available. Antibodies and antigens can be detected in the blood using ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

to identify infection. Adult worm antigens can be detected by indirect haemagglutination assays (IHAs). Polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample rapidly, allowing scientists to amplify a very small sample of DNA (or a part of it) sufficiently to enable detailed st ...

(PCR) is also used for detecting the parasite DNA. Circulating cathodic antigen (CCA) in urine can be tested with lateral flow immune-chromatographic reagent strip and point-of-care (POC) tests.

Egg detection and immunologic tests are not particularly sensitive. Polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample rapidly, allowing scientists to amplify a very small sample of DNA (or a part of it) sufficiently to enable detailed st ...

(PCR) based testing is accurate and rapid. However, this is not frequently used in countries where the disease is common due to the cost of the equipment and the technical expertise required to run them. Using a microscope to detect eggs costs about US$0.40 per test while PCR is about $US7 per test as of 2019. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) is being studied as it is lower cost. LAMP testing is not commercially available as of 2019.

Treatment

The standard drug for ''S. mansoni'' infection is praziquantel at a dose of 40 mg/kg. Oxamniquine is also used.Epidemiology

As of 2021, 251.4 million people worldwide are having schistosomiasis due to different species of ''Schistosoma''. More than 75 million people were given medical treatment. ''S. mansoni'' is the major species causing an annual death of about 130,000. It is endemic in 55 countries and most prevalent in Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, Brazil, Venezuela and Suriname. About 80-85% of schistosomiasis is found in sub-Saharan Africa, where ''S. haematobium'', ''S. intercalatum'' and ''S. mansoni'' are endemic. Approximately 393 million Africans are at risk of infection from ''S. mansoni'', of which about 55 million are infected at any moment. Annual death due to ''S. mansoni'' is about 130,000. The prevalence rate in different countries of Africa are: 73.9% in northern Ethiopia, 37.9% in western Ethiopia, 56% in Nigeria, 60.5% in Kenya, 64.3% in Tanzania, 19.8% in Ghana, and 53.8% in Côte d'Ivoire. In Egypt, 60% of the population in the Northern and Eastern parts of the Nile Delta and only 6% in the Southern part are infected. ''S. mansoni'' is commonly found in places with poorsanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation systems ...

. Because of the parasite's fecal-oral transmission, bodies of water that contain human waste can be infectious. Water that contains large populations of the intermediate host snail species is more likely to cause infection. Young children living in these areas are at greatest risk because of their tendency to swim and bathe in cercaria

A cercaria (plural cercariae) is a larval form of the trematode class of parasites. It develops within the germinal cells of the Trematode life cycle stages, sporocyst or redia. A cercaria has a tapering head with large penetration glands. It may ...

-infected waters longer than adults

. Anyone travelling to the areas described above, and who is exposed to contaminated water, is at risk of schistosomiasis.

History

The intermediate hosts ''Biomphalaria'' snails are estimated to originate in South America 95–110 million years ago. But the parasites ''Schistosoma'' originated in Asia. In Africa, the progenitor species evolved into modern ''S. mansoni'' and ''S. haematobium'' around 2–5 million years ago. A German physician Theodor Maximillian Bilharz was the first to discover the parasite in 1851, while working at Kasr el-Aini Hospital, a medical school in Cairo. Bilharz recovered them from autopsies of dead soldiers, and noticed two distinct parasites. He described one of them as ''Distomum haematobium'' (now ''S. haematobium'') in 1852, but failed to identify the other. In one of his letters to his mentor Karl Theordor von Siebold, he mentioned some of the eggs were different in having terminal spines while some had lateral spines. Terminal-spined eggs are unique to ''S. haematobium'', while lateral spines are found only in ''S. mansoni''. Bilharz also noted that the adult flukes were different in anatomy and number of eggs they produced. He introduced the terms bilharzia and bilharziasis for the name of the infection in 1856. A German zoologistDavid Friedrich Weinland

David Friedrich Weinland (30 August 1829 in Grabenstetten – 19 September 1915 in Bad Urach, Hohenwittlingen) was a German zoologist and novelist.

The son of a pastor, Weinland attended the Protestant Seminary in Maulbronn from 1843 to 1847. ...

corrected the genus name to ''Schistosoma'' in 1858; and introduced the disease name as schistosomiasis.

The species distinction was first recognised by Patrick Manson

Sir Patrick Manson (3 October 1844 – 9 April 1922) was a Scottish physician who made important discoveries in parasitology, and was a founder of the field of tropical medicine.

He graduated from the University of Aberdeen with degrees in Ma ...

at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a public research university in Bloomsbury, central London, and a member institution of the University of London that specialises in public health and tropical medicine. The institu ...

. Manson identified lateral-spined eggs in the faeces of a colonial officer earlier posted to the West Indies, and concluded that there were two species of ''Schistosoma''. An Italian-British physician Louis Westenra Sambon gave the new names ''Schistosomum haematobium'' and ''Schistosomum mansoni'' in 1907, the latter to honour Manson. Sambon only gave partial description using a male worm. In 1908, a Brazilian physician Manuel Augusto Pirajá da Silva gave a complete description of male and female worms, including the lateral-spined eggs. Pirajá da Silva obtained specimens from three necropsies and eggs from 20 stool examinations in Bahia

Bahia () is one of the 26 Federative units of Brazil, states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo (state), São Paulo, Mina ...

. He gave the name ''S. americanum''. The species identity was confirmed in 1907 by British parasitologist Robert Thomson Leiper, identifying the specific snail host, and distinguishing the egg structure, thereby establishing the life cycle.

References

External links

*Disease info at CDC

{{Authority control Diplostomida Parasitic helminths of humans Waterborne diseases Animals described in 1907 Helminthiases