Saxon Garden on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Saxon Garden () is a 15.5–

The Saxon Garden was originally the site of

The Saxon Garden was originally the site of

* Saxon Palace. A vast palace complex according to

* Saxon Palace. A vast palace complex according to

sztuka.net

{{Parks in Warsaw Urban public parks Parks in Warsaw Gardens in Poland 1727 establishments in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Parks established in the 18th century Śródmieście Północne

hectare

The hectare (; SI symbol: ha) is a non-SI metric unit of area equal to a square with 100-metre sides (1 hm2), that is, square metres (), and is primarily used in the measurement of land. There are 100 hectares in one square kilometre. ...

public garden in central ('' Śródmieście'') Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, facing Piłsudski Square. It is the oldest public park in the city. Founded in the late 17th century, it was opened to the public in 1727 as one of the first publicly accessible parks in the world.

History

Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

fortification

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Lati ...

s, "Sigismund Sigismund (variants: Sigmund, Siegmund) is a German proper name, meaning "protection through victory", from Old High German ''sigu'' "victory" + ''munt'' "hand, protection". Tacitus latinises it ''Segimundus''. There appears to be an older form of ...

's Ramparts," and of a palace built in 1666 for the powerful aristocrat, Jan Andrzej Morsztyn. The garden was extended in the reign of King Augustus II, who attached it to the " Saxon Axis", a line of parks and palaces linking the western outskirts of Warsaw with the Vistula River

The Vistula (; ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest in Europe, at in length. Its drainage basin, extending into three other countries apart from Poland, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra ...

.

The park of the adjoining Saxon Palace was opened to the public on 27 May 1727. It became a public park before Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

(1791), the Pavlovsk Palace

Pavlovsk Palace () is an 18th-century Russian Imperial residence built by the order of Catherine the Great for her son Grand Duke Paul, in Pavlovsk, within Saint Petersburg. After his death, it became the home of his widow, Maria Fe ...

, Peterhof Palace

The Peterhof Palace ( rus, Петерго́ф, Petergóf, p=pʲɪtʲɪrˈɡof; an emulation of German "Peterhof", meaning "Peter's Court") is a series of palaces and gardens located in Petergof, Saint Petersburg, Russia, commissioned by Peter th ...

and Summer Garden

The Summer Garden () is a historic public garden that occupies an eponymous island between the Neva, Fontanka, Moika, and the Swan Canal in

downtown Saint Petersburg, Russia and shares its name with the adjacent Summer Palace of Peter th ...

(1918), Villa d'Este

The Villa d'Este is a 16th-century villa in Tivoli, Lazio, Tivoli, near Rome. It is a masterpiece of Italian architecture and garden design, famous for its terraced hillside Italian Renaissance garden and the ingenuity of its architectural featu ...

(1920), Kuskovo (1939), Stourhead

Stourhead () is a 1,072-hectare (2,650-acre) estate at the source of the River Stour in the southwest of the English county of Wiltshire, extending into Somerset.

The estate is about northwest of the town of Mere and includes a Grade I list ...

(1946), Sissinghurst

Sissinghurst is a small village in the borough of Tunbridge Wells in Kent, England. Originally called ''Milkhouse Street'' (also referred to as ''Mylkehouse''), Sissinghurst changed its name in the 1850s, possibly to avoid association with the s ...

(1967), Stowe (1990), Vaux-le-Vicomte

The Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte () or simply Vaux-le-Vicomte is a Baroque French château located in Maincy, near Melun, southeast of Paris in the Seine-et-Marne Departments of France, department of Île-de-France.

Built between 1658 and 1661 ...

(1990s), and most other world-famous parks and gardens.

Initially a Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

French-style park, in the 19th century it was turned into a Romantic English-style landscape park. Destroyed during and after the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising (; ), sometimes referred to as the August Uprising (), or the Battle of Warsaw, was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from ...

, it was partly reconstructed after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Features

18th century

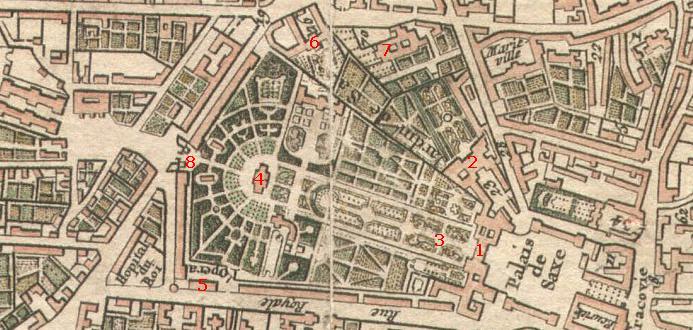

The garden was a typical example of the Baroque extension of formal vistas inspired by the park of Versailles. The park starts from the back façade of the palace, flanking a long alley with many sculptures. The central avenue lead directly to the palace, as was usual in French parks of the era. Following the completion of the Saxon Palace, the surroundings were included in the structure. The Brühl Palace and The Blue Palace, as well as the pavilion known as The Great Salon, were all raised or rebuilt during the initial construction of Saxon Establishment during the reign of Augustus II. A baroque flower garden with pieces ofturf

Sod is the upper layer of turf that is harvested for transplanting. Turf consists of a variable thickness of a soil medium that supports a community of turfgrasses.

In British and Australian English, sod is more commonly known as ''turf'', ...

, flower beds, hedges and trees was created. These gardens extended the central axis of a symmetrical building façade in rigorously symmetrical axial designs of patterned parterre

A ''parterre'' is a part of a formal garden constructed on a level substrate, consisting of symmetrical patterns, made up by plant beds, plats, low hedges or coloured gravels, which are separated and connected by paths. Typically it was the ...

s, gravel walks and formally planted bosquet

In the French formal garden, a ''bosquet'' (French, from Italian ''boschetto'', "grove, wood") is a formal plantation of trees in a wide variety of forms, some open at the bottom and others not. At a minimum a bosquet can be five trees of identi ...

s. The parterres were laid out from 1713 by Joachim Heinrich Schultze and Gothard Paul Thörl from 1735.

* Saxon Palace. A vast palace complex according to

* Saxon Palace. A vast palace complex according to Tylman van Gameren

Tylman van Gameren, also ''Tilman'' or ''Tielman'' and Tylman Gamerski, (Utrecht, 3 July 1632 – c. 1706, Warsaw) was a Dutch-born Polish architect and engineer who, at the age of 28, settled in Poland and worked for Queen Marie Casimire, ...

's design arose here between 1661 and 1664 for Jan Andrzej Morsztyn. In 1669 the palace was rebuilt and enlarged. The main break was enhanced and a two galleries ended with a double-storied pavillons were added to the palace's alcoves. In 1713 the building was purchased by King Augustus II, who started to repurchase surrounding freeholds and demolishing the buildings. Reconstruction of the palace establishment and creating of the Saxon Axis passed through three distinct stages – from 1713 to the 1720s according to Carl Friedrich Pöppelmann's and Joachim Daniel von Jauch's design, secondly to 1733 and completion in 1748 by Augustus III

Augustus III (; – "the Saxon"; ; 17 October 1696 5 October 1763) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1733 until 1763, as well as Elector of Saxony in the Holy Roman Empire where he was known as Frederick Augustus II ().

He w ...

"the Corpulent". The palace was remodeled in 1842. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the Saxon Palace was blown up by the Germans after the collapse of the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising (; ), sometimes referred to as the August Uprising (), or the Battle of Warsaw, was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from ...

in 1944.

* Brühl Palace, former palace of Jerzy Ossoliński, was rebuilt between 1681 and 1697 by Tylman van Gameren. Purchased by Heinrich von Brühl

Heinrich, Count von Brühl (, 13 August 170028 October 1763), was a Polish-Saxon statesman at the court of Electorate of Saxony, Saxony and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and a member of the powerful German von Brühl family. The incumbenc ...

in 1750, on his request it was reconstructed by Johann Friedrich Knöbel and Joachim Daniel von Jauch between 1754 and 1759. The two outbuildings were built in that time and put together with the palace. Later another two outbuildings were added and weaved together by an enclosure decorated with sculptures. The central limb of the building was enhanced and covered with a mansard roof

A mansard or mansard roof (also called French roof or curb roof) is a multi-sided gambrel-style hip roof characterised by two slopes on each of its sides, with the lower slope at a steeper angle than the upper, and often punctured by dormer wi ...

. During 1932–37 the palace was adapted for use as the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the new Polish Republic. It was deliberately destroyed by the Germans on December 18, 1944.

* Sandstone statues, a part of the rich collection of sculptures removed to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

after recapturing the city by Marshal Suvorov in 1794, and placed in the Summer Garden

The Summer Garden () is a historic public garden that occupies an eponymous island between the Neva, Fontanka, Moika, and the Swan Canal in

downtown Saint Petersburg, Russia and shares its name with the adjacent Summer Palace of Peter th ...

. According to the 1745 plan of the Saxon Garden there were 70 postuments in the garden, and in 1797 there were only 37 sculptures left; only 20 of them have been preserved until our times. Four of these sculptures were completely destroyed during the blowing up of the Saxon Palace in 1944, but they were later reconstructed. Included are groups of sculptures, including Arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

, Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, Bacchus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; ) is the god of wine-making, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, festivity, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre. He was also known as Bacchus ( or ; ) by the Gre ...

, Flora

Flora (: floras or florae) is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. The corresponding term for animals is ''fauna'', and for f ...

, Geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

, two sculptures identified as Glory, Instruct, Intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

, Intellect

Intellect is a faculty of the human mind that enables reasoning, abstraction, conceptualization, and judgment. It enables the discernment of truth and falsehood, as well as higher-order thinking beyond immediate perception. Intellect is dis ...

, Justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

, Medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, Military Architecture, Painting

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

, Poetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

, Rationality

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reason. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do, or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ab ...

, Science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, Sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

, Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

and Winter. They were generally made before 1745 by anonymous Warsaw sculptors under the direction of Johann Georg Plersch.

* The Great Salon, situated on the axis in the center of a Saxon Garden, was intended simply to provide a suitable end to the main garden axis. It was constructed after 1720 according to Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann's design. The building was opened to the garden by semicircular porte-fenêtres and oculi. A terrace above the ground level of the building was enclosed by an attic decorated with vases; also, two outhouses from both sides were added. The Great Salon was demolished in 1817.

* Operalnia, the 500-seat opera house, was opened in 1748. It was built under the architect Carl Friedrich Pöppelmann and modelled on the Small Theatre in Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

, built by Christoph Bayer in 1687. The interior was decorated in a heavy, sumptuous baroque style by the court artists. On November 19, 1765, in Operalnia, the actors of The Majesty put on the premiere of ’s ''Intruders'' (Natręci), a comedy which was a loose adaptation of a play by Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, ; ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the great writers in the French language and world liter ...

. Since the acting team had all the features of a fully professional and national group (they performed in Polish and earned their living through acting), November 19 is the anniversary of the establishment of the National Theatre. The National stage belonged to the elements of the educational and cultural reform programme in the falling Republic of Poland, prepared by King Stanisław August Poniatowski

Stanisław II August (born Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski; 17 January 1732 – 12 February 1798), known also by his regnal Latin name Stanislaus II Augustus, and as Stanisław August Poniatowski (), was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuani ...

. Over decades this theatre, taking care of the works of Polish playwrights, was the ground on which the cultural development of Polish people thrived. The building was demolished in 1772.

* The Blue Palace. It takes its name from the colour of the roof. the palace was purchased by King Augustus II for his daughter Anna Karolina Orzelska from bishop Teodor Andrzej Potocki

Teodor Andrzej Potocki (13 February 1664 – 12 December 1738) was a Polish nobleman (szlachcic), Primate of Poland, interrex in 1733.

Teodor was Rector of Przemyśl and canon of Kraków since 1687, Bishop of Chełmno since 1699 and Bishop ...

. The palace was rebuilt in 1726 by Joachim Daniel von Jauch and Johann Sigmund Deybel. The King wanted to offer it to Anna as a Christmas present. In six weeks, the palace was renovated by 300 masons and craftsmen working night and day. The courtyard, encompassed by a walled enclosure, had two gates. Column galleries were situated on both sides of the garden façade. A backside garden (integral part of the Saxon Garden) and a cascade fountain were designed by Carl Friedrich Pöppelmann. Since 1811, it has been the property of the Zamoyski family

The House of Zamoyski (plural: Zamoyscy) is an important Polish noble (''szlachta'') family belonging to the category of Polish magnates. They used the Jelita coat of arms. The surname "Zamoyski" literally means "of/from Zamość" and refle ...

which remodeled it in a late Neoclassical style. The palace was rebuilt after the war devastations.

* The Church of St. Anthony of Padua and Reformed Franciscan Monastery was founded in 1623 in gratitude for the capture of Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow.

First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It has been a regional capital for most of ...

on June 13, 1611 (Liturgical Feasts of Saint Anthony of Padua

Anthony of Padua, OFM, (; ; ) or Anthony of Lisbon (; ; ; born Fernando Martins de Bulhões; 15 August 1195 – 13 June 1231) was a Portuguese Catholic priest and member of the Order of Friars Minor.

Anthony was born and raised by a wealth ...

) by Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa (, ; 20 June 1566 – 30 April 1632

N.S.) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 to 1632 and, as Sigismund, King of Sweden from 1592 to 1599. He was the first Polish sovereign from the House of Vasa. Re ...

and dedicated on May 13, 1635. This church was heavily damaged during the Deluge

A deluge is a large downpour of rain, often a flood.

The Deluge refers to the flood narrative in the biblical book of Genesis.

Deluge or Le Déluge may also refer to:

History

*Deluge (history), the Swedish and Russian invasion of the Polish-L ...

by the Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

n army of George II Rákóczi

George II Rákóczi (30 January 1621 – 7 June 1660), was a Hungarian nobleman, Prince of Transylvania (1648-1660), the eldest son of George I and Zsuzsanna Lorántffy.

Early life

He was elected Prince of Transylvania during his father' ...

. The new church was founded by Castellan Stanisław Leszczyc-Skarszewski. Work began in 1668 following the plan of Józef Szymon Bellotti. In 1734, the church became the parish church of the royal court in the Saxon Palace. The king ordered a special loge for him and his wife to be built on the left side of the presbytery (1734–35), and the royal sculptor Johann Georg Plersch created the sculptures inside. The church was partly destroyed during the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising (; ), sometimes referred to as the August Uprising (), or the Battle of Warsaw, was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from ...

.

* The Iron Gate was a part of The Saxon Establishment, which itself had a shape of a pentagon covered an area of around 17 ha. The gate was constructed according to Joachim Daniel von Jauch's design after 1735, together with other buildings of the Saxon Axis border, like Mounted Crown Guards barracks, a wall with bastions from the south and west, or the Blue Palace. It was embellished with cartouches with Polish and Lithuanian coats of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the last two being outer garments), originating in Europe. The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic ac ...

. The gate was demolished in 1821.

View of The Saxon Establishment from the north painted by Bernardo Bellotto

Bernardo Bellotto (c. 1721/2 or 30 January 172117 November 1780), was an Italians, Italian urban Landscape art, landscape Painting, painter or ''vedutista'', and printmaker in etching famous for his Veduta, ''vedute'' of European cities – Dr ...

''il Canaletto'' of 1764 shows a main entrance to the palace from Wielopole with The Iron Gate and the 21 m-high garden gloriette

A gloriette (from the 12th-century French meaning "little room") is a building in a garden erected on a site that is elevated with respect to the surroundings. The structural execution and shape can vary greatly, often in the form of a pavili ...

, so-called Great Salon.

19th and 20th centuries

* Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, dedicated to the unknown soldiers who have given their lives for Poland. It is one of many such national tombs of unknowns that were erected afterWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, as well as the most important national symbols of bravery and heroism. In 1925, architect Stanisław Ostrowski produced a design to be located under the arcades of the Saxon Palace in Warsaw. The triple arch of the Tomb is the only remnant of the Saxon Palace colonnade. Here official delegations place wreaths and pay homage to the killed soldiers. The tomb has a change of guards every hour.

* Fountain, with an elaborately carved plaque resting on a shell form basin supported by a scrolled bracket, is often used by dating couples as their meeting place. It was established in 1855. The fountain is the centrepiece of gardens designed by the 19th-century designer Henryk Marconi and also one of the most precious urban symbols of Warsaw.

* Marble sundial, an 1863 horizontal sundial

A sundial is a horology, horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the position of the Sun, apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the ...

, is situated close to the big fountain in the centre of the park. It was established by the significant physicist and meteorologist Antoni Szeliga Magier (1762–1837).

* Water Tower, in the northwest part of the Saxon Garden, is situated by the ornamental lake surrounded by willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, of the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 350 species (plus numerous hybrids) of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions.

Most species are known ...

s. This classicist water tower in the shape of a Roman monopteros

A monopteros (Ancient Greek: , from: μόνος, 'only, single, alone', and , 'wing'), also called a monopteron or cyclostyle, is a circular colonnade supporting a roof but without any walls.Curl, James Stevens (2006). ''Oxford Dictionary of Archi ...

was modelled on the Temple of Vesta

The Temple of Vesta, or the aedes (Latin ''Glossary of ancient Roman religion#aedes, Aedes Vestae''; Italian language, Italian: ''Tempio di Vesta''), was an ancient edifice in Rome, Italy. It is located in the Roman Forum near the Regia and the H ...

in Tivoli. It was designed in 1852 by the architect Henryk Marconi.

* Summer Theatre, a popular summer variéte theatre, existed between 1870 and 1939. It was under Stanisław Moniuszko's "rule" at the Teatr Wielki that the wooden Summer Theatre was built in the Saxon Garden, between the Water Tower building and the Blue Palace by Aleksander Zabierzowski. From then on, summer performances from the Warsaw theatres were shown there every year. At the time, the Summer Theatre could seat an audience of 1,065. Helena Modjeska

Helena Modrzejewska (; born Jadwiga Helena Mizel; October 12, 1840 – April 8, 1909), known professionally in the United States as Helena Modjeska, was a Polish-American actress who specialized in Shakespearean and tragic roles.

She was success ...

and Pola Negri

Pola Negri (; born Barbara Apolonia Chałupiec ; 3 January 1897 – 1 August 1987) was a Polish stage and film actress and singer. She achieved worldwide fame during the silent and golden eras of Hollywood and European film for her tragedienn ...

made several appearance there. The theatre burned in September 1939 following a direct hit by an incendiary bomb and was never restored.

* Palm House

Palm house is a term sometimes used for large and high heated display greenhouses that specialise in growing arecaceae, palms and other tropical and subtropical plants. In Victorian era, Victorian Britain, several ornate glass and iron palm house ...

, modeled after Victorian glass and iron structures in England, was built in 1894. It was created specifically for the exotic palms being collected and introduced to Europe in the 19th century. The elegant design, with its unobstructed space for the spreading crowns of the tall palms, was a perfect marriage of form and function. The structure was destroyed during the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising (; ), sometimes referred to as the August Uprising (), or the Battle of Warsaw, was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from ...

and Planned destruction of Warsaw and was never restored.

* The Monument dedicated to Maria Konopnicka

Maria Konopnicka (; ; 23 May 1842 – 8 October 1910) was a Polish people, Polish poet, novelist, children's writer, translator, journalist, critic and activist for women's rights and for Polish independence. She used pseudonyms, including ''Jan ...

, famous Polish poet and writer mainly for children and youth, was unveiled in 1965.

* The Stefan Starzyński Monument, statue of city mayor, and leader of the defence efforcts during the Siege of Warsaw in 1939, was added in 1981, and removed in 2008

See also

* Saxon PalaceReferences

External links

*sztuka.net

{{Parks in Warsaw Urban public parks Parks in Warsaw Gardens in Poland 1727 establishments in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Parks established in the 18th century Śródmieście Północne