Sara Branham Matthews on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

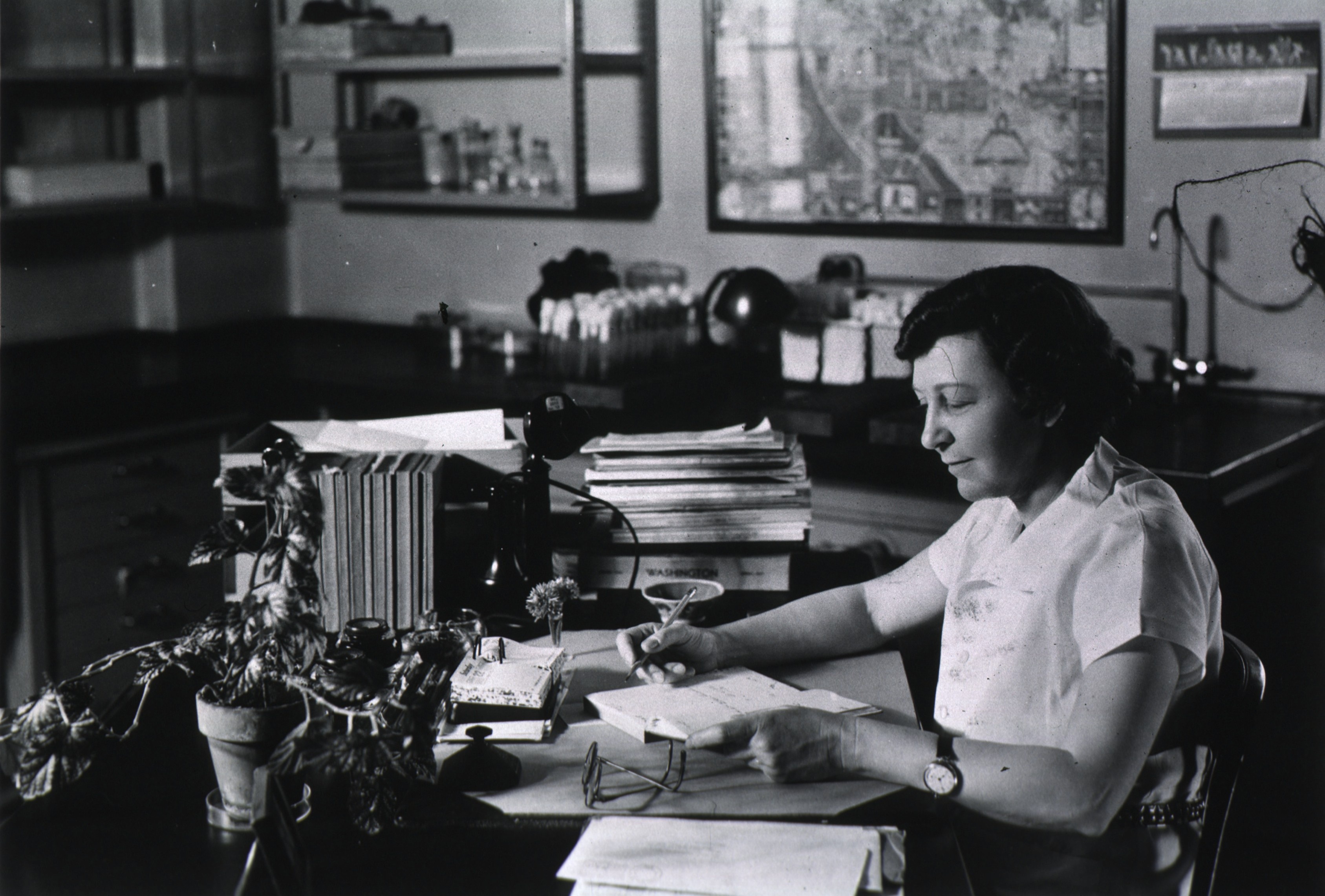

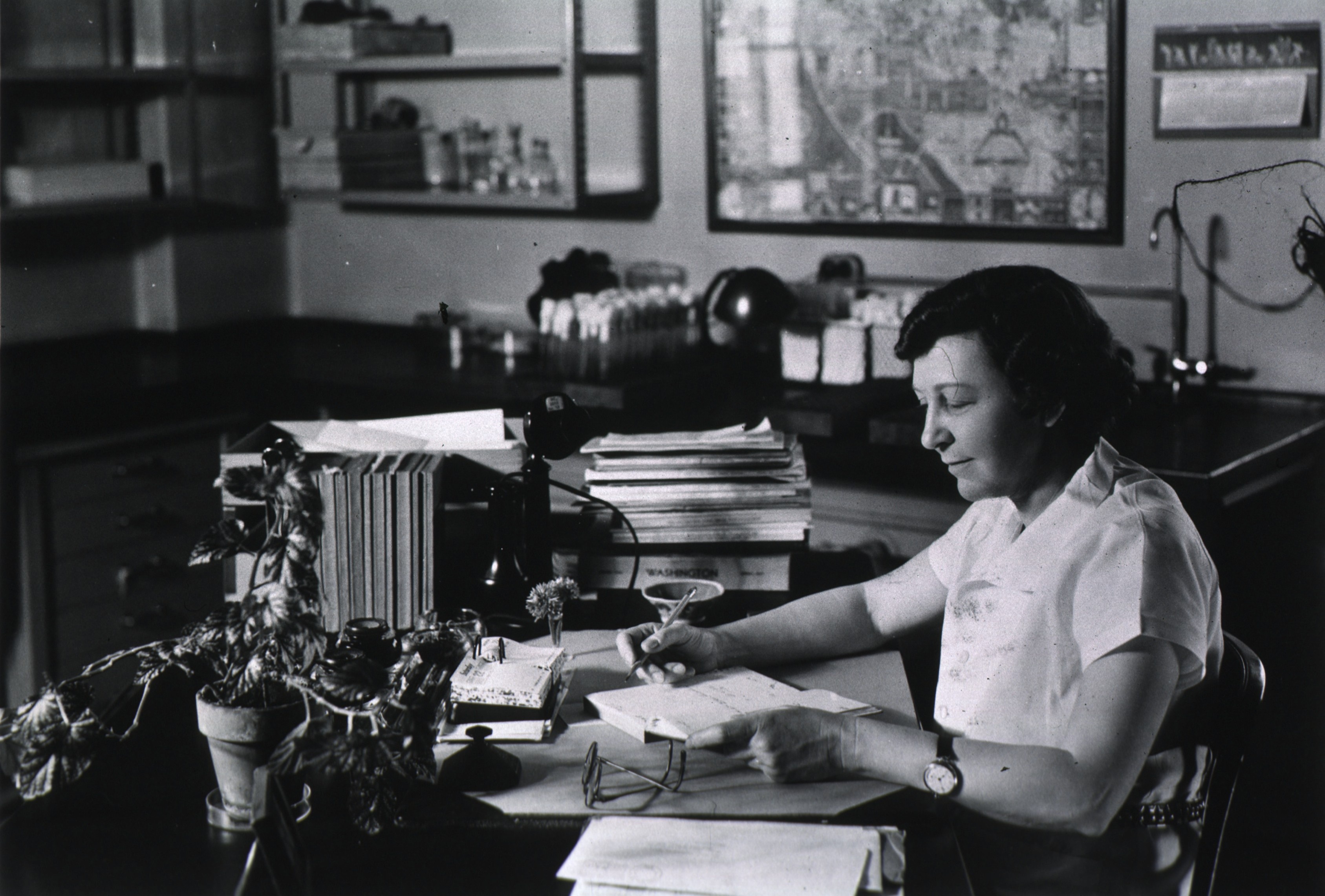

Sara Elizabeth Branham Matthews (1888–1962) was an American

Sara Elizabeth Branham Matthews (1888–1962) was an American

Sara Elizabeth Branham Matthews (1888–1962) was an American

Sara Elizabeth Branham Matthews (1888–1962) was an American microbiologist

A microbiologist (from Greek ) is a scientist who studies microscopic life forms and processes. This includes study of the growth, interactions and characteristics of microscopic organisms such as bacteria, algae, fungi, and some types of par ...

and physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

best known for her research into the isolation and treatment of ''Neisseria meningitidis

''Neisseria meningitidis'', often referred to as meningococcus, is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause meningitis and other forms of meningococcal disease such as meningococcemia, a life-threatening sepsis. The bacterium is referred to as ...

'', a causative organism of meningitis.

Biography

Branham was born July 25, 1888, inOxford, Georgia

Oxford is a city in Newton County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 2,134. It is the location of Oxford College of Emory University.

Much of the city is part of the National Parks-designated Oxford Historic ...

to mother Sarah ("Sallie") Stone and father Junius Branham. Although education of women was not commonplace at the time, members of Sara Branham's family were firm believers in the value of education for women. Following in the footsteps of her mother (Amanda Stone Branham, 1885 graduate) and grandmother (Elizabeth Flournoy Stone, 1840 graduate), she attended Wesleyan College

Wesleyan College is a private, liberal arts women's college in Macon, Georgia. Founded in 1836, Wesleyan was the first college in the world chartered to grant degrees to women.

History

The school was chartered on December 23, 1836, as the G ...

in Macon, Georgia and graduated with a B.S. degree in biology in 1907 as a third generation alumna. She was a member of Alpha Delta Pi

Alpha Delta Pi (), commonly known as ADPi (pronounced "ay-dee-pye"), is an International Panhellenic sorority founded on May 15, 1851, at Wesleyan College in Macon, Georgia. It is the oldest secret society for women.

Alpha Delta Pi is a mem ...

. With few professional opportunities offered to women with an education then, she became a schoolteacher, working for ten years in Georgia's public school system in Sparta, Decatur, and finally at Atlanta's Girls' High School. In the summer of 1917, Sara began taking classes at the University of Colorado

The University of Colorado (CU) is a system of public universities in Colorado. It consists of four institutions: University of Colorado Boulder, University of Colorado Colorado Springs, University of Colorado Denver, and the University o ...

to expand her education, but within a few weeks, she was hired by the University of Colorado in 1917 as a bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classific ...

teacher, since there was a shortage of men from the department during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. She remarked on the change of roles: "When I had had about six weeks of bacteriology, they offered me a job to teach it!" She completed a second B.S. degree at the university in 1919, majoring in chemistry and zoology, and stated that "When the war was over, I was too deep in bacteriology to ever get out again."

After finishing her degree in Colorado in 1919, she went to Chicago during the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 with a desire to enter the field of medical research. She enrolled at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

where she would eventually complete, all with honors, a M.S. degree, a Ph.D.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is a ...

degree in bacteriology, and a M.D.

Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated M.D., from the Latin ''Medicinae Doctor'') is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the M.D. denotes a professional degree. T ...

degree. Her advisor at the university suggested that she study the etiology of influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

for her thesis. Therefore, in pursuit of her degrees at the University of Chicago, she studied filterable agents (virus

A virus is a wikt:submicroscopic, submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and ...

es), and published over a dozen papers on the topic. This work eventually earned Branham a position as instructor in the Department of Hygiene and Bacteriology.

In 1927, Branham left Chicago and began working as an associate at the University of Rochester School of Medicine

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase ''universitas magistrorum et scholarium'', which ...

under Stanhope Bayne-Jones. Shortly thereafter, the outbreak of meningococcus

''Neisseria meningitidis'', often referred to as meningococcus, is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause meningitis and other forms of meningococcal disease such as meningococcemia, a life-threatening sepsis. The bacterium is referred to as a ...

arrived in California from China. Because of this, Branham's career shifted paths, and she began working for what is now the National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health, commonly referred to as NIH (with each letter pronounced individually), is the primary agency of the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U ...

(NIH) (then, known as the Hygienic Laboratory of the United States Public Health Service) in Bethesda, Maryland

Bethesda () is an unincorporated, census-designated place in southern Montgomery County, Maryland. It is located just northwest of Washington, D.C. It takes its name from a local church, the Bethesda Meeting House (1820, rebuilt 1849), which ...

as a senior bacteriologist, in order to study meningococcus. Branham stayed at the NIH for the rest of her career. She remained in the role for over 25 years until she was promoted to the Chief of Bacterial Toxins of the Division of Biological Standards in 1955.

Branham married retired businessman Philip S. Matthews in 1945. Matthews died four years later. Branham retired from the NIH in 1958 at the age of seventy from the position of Chief of the Section on Bacterial Toxins, and died November 16, 1962 after a sudden heart attack. She is buried in Oxford, Georgia in her family's plot.

Broadly, Sara Branham's research was based in the field of infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable d ...

s, including influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

, salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of rod-shaped (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and '' Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' is the type species and is fur ...

, shigella

''Shigella'' is a genus of bacteria that is Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, non-spore-forming, nonmotile, rod-shaped, and genetically closely related to '' E. coli''. The genus is named after Kiyoshi Shiga, who first discovered it in 189 ...

, diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

, dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complication ...

, and psittacosis

Psittacosis—also known as parrot fever, and ornithosis—is a zoonotic infectious disease in humans caused by a bacterium called ''Chlamydia psittaci'' and contracted from infected parrots, such as macaws, cockatiels, and budgerigars, and from ...

. She studied the toxins produced by Shigella dysenteriae

''Shigella dysenteriae'' is a species of the rod-shaped bacterial genus ''Shigella''. ''Shigella'' species can cause shigellosis (bacillary dysentery). Shigellae are Gram-negative, non-spore-forming, facultatively anaerobic, nonmotile bacteria ...

. The main focus of Branham's work at the NIH, however, was meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion ...

. This focus was Branham responding to what was quickly becoming a health crisis: an untreatable form of meningitis had arrived in the United States and began spreading quickly. She is credited with the discovery and isolation of ''Neisseria meningitidis

''Neisseria meningitidis'', often referred to as meningococcus, is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause meningitis and other forms of meningococcal disease such as meningococcemia, a life-threatening sepsis. The bacterium is referred to as ...

''. Neisseria is a common causative organism of meningitis, and its taxonomy is well characterized by Branham throughout her work. She also discovered that the infection could be treated with sulfa drugs rather than antiserums that were used at the time, but that were ineffective in treating this strain. Branham was considered an international expert on the strain of disease: due to her great contributions to the knowledge about it, Neisseria catarrhalis was renamed Branhamella caterrhalis in 1970, years after Branham's death. The new name was officially accepted in the 1974 edition of Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology

''Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology'' is the main resource for determining the identity of prokaryotic organisms, emphasizing bacterial species, using every characterizing aspect.

The manual was published subsequent to the ''Bergey's Manu ...

. Branham's studies in infectious disease were nationally known, and she came to be considered as one of the "grand ladies of microbiology". In a biographical article about Branham published in the Atlanta Constitution, the huge impact of her work was summarized in the exclamation: "She killed millions of killers!"

Alongside her busy professional life, Sara Branham played an active role in the community. She is regarded as a very influential woman that inspired those who worked with her throughout her career. She gave back to her alma mater by being an active alumna and supporter, returning for reunions and serving as alumna trustee from 1936 to 1939. She was a featured speaker for several events and gave many lectures, including two in 1960 just a couple years before she died. She was also active in many scientific societies. She contributed to what is now the American Society for Microbiology

The American Society for Microbiology (ASM), originally the Society of American Bacteriologists, is a professional organization for scientists who study viruses, bacteria, fungi, algae, and protozoa as well as other aspects of microbiology. It w ...

(then, known as the Society of American Bacteriologists). She was a delegate at the First and Second International Congresses in Microbiology in 1930 (Paris) and 1936 (London). She served as a diplomat on both the American Board of Pathology in the field of Clinical Microbiology and the National Board of Medical Examiners

The National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME), founded in 1915, is a United States non-profit which develops and manages assessments of health care professionals. Known for its role in developing the United States Medical Licensing Examination (U ...

. One of Branham's colleagues remarked that Branham was equally comfortable entertaining in a chiffon dress and in a lab coat. She was known to be meticulous about her home and lawn, and was an avid ornithologist and gardener.

Awards and honors

Branham was awarded the Howard Taylor Ricketts Prize in 1924 from the University of Chicago. Wesleyan College's Alumnae Association began recognizing the distinguished achievement of their individual alumnae in 1950. In the inaugural year, Branham was honored with Wesleyan College's first Distinguished Service Award in 1950. She later received a similar award from the University of Chicago Medical School Alumni Association. She was also awarded an honorary doctor of science from the University of Colorado, which would be the last of six total degrees she earned in her life. In 1959, she was honored as theAmerican Medical Women's Association

The American Medical Women's Association (AMWA) is a professional advocacy and educational organization of women physicians and medical students. Founded in 1915 by Bertha Van Hoosen, the AMWA works to advance women in medicine and to serve as a v ...

's Medical Woman of the Year. In a similar fashion as the honor from Wesleyan, Branham was honored in Georgia Women of Achievement's first class of inductees in 1992.

Over the course of her career, she published eighty papers and helped with the composition of many textbooks. Her papers are held at the National Library of Medicine

The United States National Library of Medicine (NLM), operated by the United States federal government, is the world's largest medical library.

Located in Bethesda, Maryland, the NLM is an institute within the National Institutes of Health. It ...

.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Branham Matthews, Sara American bacteriologists American microbiologists American medical researchers 1888 births 1962 deaths American women biologists Women medical researchers Women microbiologists National Institutes of Health people Wesleyan College alumni University of Colorado alumni Pritzker School of Medicine alumni People from Newton County, Georgia Physicians from Georgia (U.S. state) 20th-century American physicians 20th-century American biologists 20th-century American women scientists 20th-century American women physicians University of Colorado faculty