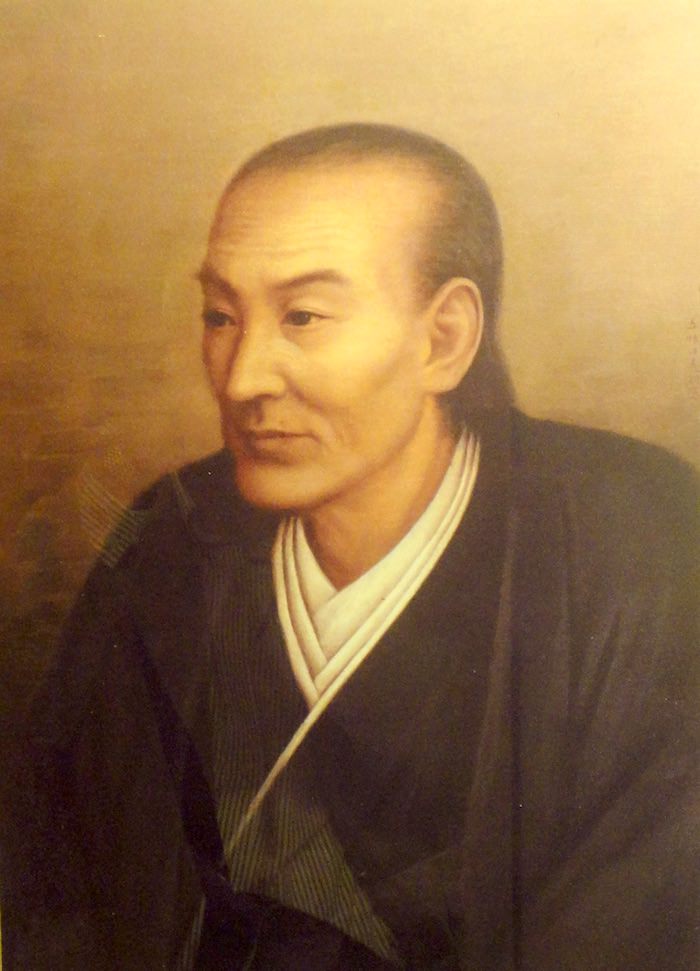

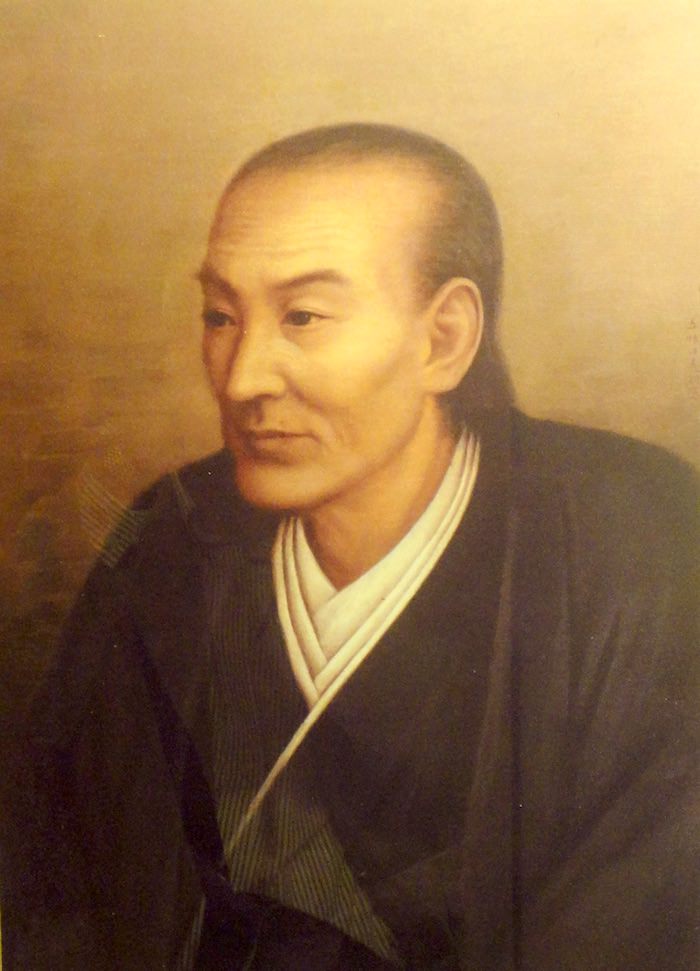

Samurai Hand Colored C1890 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in

Milites, Knights and Samurai: Military Terminology, Comparative History, and the Problem of Translation

” In ''The Normans and Their Adversaries at War'', ed. Richard Abels and Bernard Bachrach, 167–84. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2001. "Finally there is the term samurai. This noun derives from the verb saburau, to serve, and it is again a social marker, though it marks social function and not class, It means a retainer of a lord - usually, in the sixteenth century, the retainer of a daimyo, a leader of one of the essentially independent states of the Sengoku, or warring states period. It has no functional component - all sorts of soldiers, including pikemen, bowmen, musketeers and horsemen were samurai" In the Tokugawa period, the terms were roughly interchangeable, as the military class was legally limited to the retainers of the shogun or daimyo. However, strictly speaking samurai referred to higher ranking retainers, although the cut off between samurai and other military retainers varied from domain to domain. Also usage varied by class, with commoners referring to all sword carrying men as samurai, regardless of rank.

Costume Museum For lower-ranked samurai, the was introduced, the simplest style of armor that protected only the front of the torso and the sides of the abdomen. In the late Kamakura period, a new type of armor called appeared, in which the two ends of the were extended to the back to provide greater protection.

File:Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba e2.jpg, Samurai of the

Various samurai clans struggled for power during the  The thunderstorms of 1274 and the typhoon of 1281 helped the samurai defenders of Japan repel the Mongol invaders despite being vastly outnumbered. These winds became known as ''kami-no-Kaze'', which literally translates as "wind of the gods". This is often given a simplified translation as "divine wind". The ''kami-no-Kaze'' lent credence to the Japanese belief that their lands were indeed divine and under supernatural protection.

The thunderstorms of 1274 and the typhoon of 1281 helped the samurai defenders of Japan repel the Mongol invaders despite being vastly outnumbered. These winds became known as ''kami-no-Kaze'', which literally translates as "wind of the gods". This is often given a simplified translation as "divine wind". The ''kami-no-Kaze'' lent credence to the Japanese belief that their lands were indeed divine and under supernatural protection.

Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World. Issues of inheritance caused family strife as

''Daimyo'' who became more powerful as the shogunate's control weakened were called , and they often came from ''shugo daimyo'', , and . In other words, ''sengoku daimyo'' differed from ''shugo daimyo'' in that a ''sengoku daimyo'' was able to rule the region on his own, without being appointed by the shogun.

During this period, the traditional master-servant relationship between the lord and his vassals broke down, with the vassals eliminating the lord, internal clan and vassal conflicts over leadership of the lord's family, and frequent rebellion and puppetry by branch families against the lord's family. These events sometimes led to the rise of samurai to the rank of ''sengoku daimyo''. For example, Hōjō Sōun was the first samurai to rise to the rank of ''sengoku daimyo'' during this period.

''Daimyo'' who became more powerful as the shogunate's control weakened were called , and they often came from ''shugo daimyo'', , and . In other words, ''sengoku daimyo'' differed from ''shugo daimyo'' in that a ''sengoku daimyo'' was able to rule the region on his own, without being appointed by the shogun.

During this period, the traditional master-servant relationship between the lord and his vassals broke down, with the vassals eliminating the lord, internal clan and vassal conflicts over leadership of the lord's family, and frequent rebellion and puppetry by branch families against the lord's family. These events sometimes led to the rise of samurai to the rank of ''sengoku daimyo''. For example, Hōjō Sōun was the first samurai to rise to the rank of ''sengoku daimyo'' during this period.

Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken WorldArms for battle – spears, swords, bows.

Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken WorldKazuhiko Inada (2020), ''Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords''. p42. Although the had become even more obsolete, some ''sengoku daimyo'' dared to organize assault and kinsmen units composed entirely of large men equipped with to demonstrate the bravery of their armies.Kazuhiko Inada (2020), ''Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords''. p39. These changes in the aspect of the battlefield during the Sengoku period led to the emergence of the style of armor, which improved the productivity and durability of armor. In the history of Japanese armor, this was the most significant change since the introduction of the and in the Heian period. In this style, the number of parts was reduced, and instead armor with eccentric designs became popular.

Costume Museum By the end of the Sengoku period, allegiances between warrior vassals, also known as military retainers, and lords were solidified. Vassals would serve lords in exchange for material and intangible advantages, in keeping with

The Azuchi-Momoyama period refers to the period when

The Azuchi-Momoyama period refers to the period when

In 1592 and again in 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, aiming to invade China through Korea, mobilized an army of 160,000 peasants and samurai and Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), deployed them to Korea in one of the largest military endeavors in Eastern Asia until the late 19th century. Taking advantage of arquebus mastery and extensive wartime experience from the Sengoku period, Japanese samurai armies made major gains in most of Korea. A few of the famous samurai generals of this war were Katō Kiyomasa, Konishi Yukinaga, and Shimazu Yoshihiro. Katō Kiyomasa advanced to Orangkai territory (present-day Manchuria) bordering Korea to the northeast and crossed the border into northern China.

Kiyomasa withdrew back to Korea after retaliatory counterattacks from the Jurchen people, Jurchens in the area, whose castles his forces had raided. Shimazu Yoshihiro led some 7,000 samurai into battle, and despite being heavily outnumbered, defeated a host of allied Ming dynasty, Ming and Korean forces at the Battle of Sacheon (1598), Battle of Sacheon in 1598. Yoshihiro was feared as ''Oni-Shimazu'' ("Shimazu ogre") and his nickname spread across Korea and into China.

In 1592 and again in 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, aiming to invade China through Korea, mobilized an army of 160,000 peasants and samurai and Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), deployed them to Korea in one of the largest military endeavors in Eastern Asia until the late 19th century. Taking advantage of arquebus mastery and extensive wartime experience from the Sengoku period, Japanese samurai armies made major gains in most of Korea. A few of the famous samurai generals of this war were Katō Kiyomasa, Konishi Yukinaga, and Shimazu Yoshihiro. Katō Kiyomasa advanced to Orangkai territory (present-day Manchuria) bordering Korea to the northeast and crossed the border into northern China.

Kiyomasa withdrew back to Korea after retaliatory counterattacks from the Jurchen people, Jurchens in the area, whose castles his forces had raided. Shimazu Yoshihiro led some 7,000 samurai into battle, and despite being heavily outnumbered, defeated a host of allied Ming dynasty, Ming and Korean forces at the Battle of Sacheon (1598), Battle of Sacheon in 1598. Yoshihiro was feared as ''Oni-Shimazu'' ("Shimazu ogre") and his nickname spread across Korea and into China.

In spite of the superiority of Japanese land forces, the two expeditions ultimately failed after Hideyoshi's death, though the invasions did devastate the Korean peninsula. The causes of the failure included Korean naval superiority (which, led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin, harassed Japanese supply lines continuously throughout the wars, resulting in supply shortages on land), the commitment of sizable Ming forces to Korea, Korean guerrilla actions, wavering Japanese commitment to the campaigns as the wars dragged on, and the underestimation of resistance by Japanese commanders.

In the first campaign of 1592, Korean defenses on land were caught unprepared, under-trained, and under-armed. They were rapidly overrun, with only a limited number of successfully resistant engagements against the more experienced and battle-hardened Japanese forces. During the second campaign in 1597, Korean and Ming forces proved far more resilient and with the support of continued Korean naval superiority, managed to limit Japanese gains to parts of southeastern Korea. The final death blow to the Japanese campaigns in Korea came with Hideyoshi's death in late 1598 and the recall of all Japanese forces in Korea by the Council of Five Elders, established by Hideyoshi to oversee the transition from his regency to that of his son Hideyori.

In spite of the superiority of Japanese land forces, the two expeditions ultimately failed after Hideyoshi's death, though the invasions did devastate the Korean peninsula. The causes of the failure included Korean naval superiority (which, led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin, harassed Japanese supply lines continuously throughout the wars, resulting in supply shortages on land), the commitment of sizable Ming forces to Korea, Korean guerrilla actions, wavering Japanese commitment to the campaigns as the wars dragged on, and the underestimation of resistance by Japanese commanders.

In the first campaign of 1592, Korean defenses on land were caught unprepared, under-trained, and under-armed. They were rapidly overrun, with only a limited number of successfully resistant engagements against the more experienced and battle-hardened Japanese forces. During the second campaign in 1597, Korean and Ming forces proved far more resilient and with the support of continued Korean naval superiority, managed to limit Japanese gains to parts of southeastern Korea. The final death blow to the Japanese campaigns in Korea came with Hideyoshi's death in late 1598 and the recall of all Japanese forces in Korea by the Council of Five Elders, established by Hideyoshi to oversee the transition from his regency to that of his son Hideyori.

Before his death, Hideyoshi ordered that Japan be ruled by a council of the five most powerful ''sengoku daimyo'', , and Hideyoshi's five retainers, , until his only heir, the five-year-old Toyotomi Hideyori, reached the age of 16. However, having only the young Hideyori as Hideyoshi's successor weakened the Toyotomi regime. Today, the loss of all of Hideyoshi's adult heirs is considered the main reason for the downfall of the Toyotomi clan. Hideyoshi's younger brother, Toyotomi Hidenaga, who had supported Hideyoshi's rise to power as a leader and strategist, had already died of illness in 1591, and his nephew, Toyotomi Hidetsugu, who was Hideyoshi's only adult successor, was forced to commit seppuku in 1595 along with many other vassals on Hideyoshi's orders for suspected rebellion.

In this politically unstable situation, Maeda Toshiie, one of the ''Gotairō'', died of illness, and Tokugawa Ieyasu, one of the ''Gotairō'' who had been second in power to Hideyoshi but had not participated in the war, rose to power, and Ieyasu came into conflict with Ishida Mitsunari, one of the ''Go-Bukyō'' and others. This conflict eventually led to the Battle of Sekigahara, in which the led by Ieyasu defeated the led by Mitsunari, and Ieyasu nearly gained control of Japan.

Social mobility was high, as the ancient regime collapsed and emerging samurai needed to maintain a large military and administrative organizations in their areas of influence. Most of the samurai families that survived to the 19th century originated in this era, declaring themselves to be the blood of one of the four ancient noble clans: Minamoto, Taira, Fujiwara, and Tachibana clan (samurai), Tachibana. In most cases, however, it is difficult to prove these claims.

Before his death, Hideyoshi ordered that Japan be ruled by a council of the five most powerful ''sengoku daimyo'', , and Hideyoshi's five retainers, , until his only heir, the five-year-old Toyotomi Hideyori, reached the age of 16. However, having only the young Hideyori as Hideyoshi's successor weakened the Toyotomi regime. Today, the loss of all of Hideyoshi's adult heirs is considered the main reason for the downfall of the Toyotomi clan. Hideyoshi's younger brother, Toyotomi Hidenaga, who had supported Hideyoshi's rise to power as a leader and strategist, had already died of illness in 1591, and his nephew, Toyotomi Hidetsugu, who was Hideyoshi's only adult successor, was forced to commit seppuku in 1595 along with many other vassals on Hideyoshi's orders for suspected rebellion.

In this politically unstable situation, Maeda Toshiie, one of the ''Gotairō'', died of illness, and Tokugawa Ieyasu, one of the ''Gotairō'' who had been second in power to Hideyoshi but had not participated in the war, rose to power, and Ieyasu came into conflict with Ishida Mitsunari, one of the ''Go-Bukyō'' and others. This conflict eventually led to the Battle of Sekigahara, in which the led by Ieyasu defeated the led by Mitsunari, and Ieyasu nearly gained control of Japan.

Social mobility was high, as the ancient regime collapsed and emerging samurai needed to maintain a large military and administrative organizations in their areas of influence. Most of the samurai families that survived to the 19th century originated in this era, declaring themselves to be the blood of one of the four ancient noble clans: Minamoto, Taira, Fujiwara, and Tachibana clan (samurai), Tachibana. In most cases, however, it is difficult to prove these claims.

Following the passing of a law in 1629, samurai on official duty were required to wear Daishō, two swords. However, by the end of the Tokugawa era, samurai were aristocratic bureaucrats for their ''daishō'', becoming more of a symbolic emblem of power than a weapon used in daily life. They still had the legal right to cut down any commoner who did not show proper respect (''kiri-sute gomen''), but to what extent this right was used is unknown. When the central government forced ''daimyōs'' to cut the size of their armies, unemployed rōnin became a social problem.

Theoretical obligations between a samurai and his lord (usually a ''daimyō'') increased from the Genpei era to the Edo era, strongly emphasized by the teachings of Confucius and Mencius, required reading for the educated samurai class. The leading figures who introduced Confucianism in Japan in the early Tokugawa period were Fujiwara Seika (1561–1619), Hayashi Razan (1583–1657), and Matsunaga Sekigo (1592–1657).

Pederasty permeated the culture of samurai in the early seventeenth century. The relentless condemnation of pederasty by Jesuit missionaries also hindered attempts to convert Japan's governing elite to Christianity. Pederasty had become deeply institutionalized among the daimyo and samurai, prompting comparisons to ancient Pederasty in ancient Greece, Athens and Sparta. The Jesuits' strong condemnation of the practice alienated many of Japan's ruling class, creating further barriers to their acceptance of Christianity. Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shogun, was known for his interest in pederasty.

From the mid-Edo period, wealthy and farmers could join the samurai class by giving a large sum of money to an impoverished to be adopted into a samurai family and inherit the samurai's position and stipend. The amount of money given to a ''gokenin'' varied according to his position: 1,000 ''ryo'' for a and 500 ''ryo'' for an Some of their descendants were promoted to and held important positions in the shogunate. Some of the peasants' children were promoted to the samurai class by serving in the office. ''Kachi'' could change jobs and move into the lower classes, such as ''chōnin''. For example, Takizawa Bakin became a ''chōnin'' by working for Tsutaya Jūzaburō.

Following the passing of a law in 1629, samurai on official duty were required to wear Daishō, two swords. However, by the end of the Tokugawa era, samurai were aristocratic bureaucrats for their ''daishō'', becoming more of a symbolic emblem of power than a weapon used in daily life. They still had the legal right to cut down any commoner who did not show proper respect (''kiri-sute gomen''), but to what extent this right was used is unknown. When the central government forced ''daimyōs'' to cut the size of their armies, unemployed rōnin became a social problem.

Theoretical obligations between a samurai and his lord (usually a ''daimyō'') increased from the Genpei era to the Edo era, strongly emphasized by the teachings of Confucius and Mencius, required reading for the educated samurai class. The leading figures who introduced Confucianism in Japan in the early Tokugawa period were Fujiwara Seika (1561–1619), Hayashi Razan (1583–1657), and Matsunaga Sekigo (1592–1657).

Pederasty permeated the culture of samurai in the early seventeenth century. The relentless condemnation of pederasty by Jesuit missionaries also hindered attempts to convert Japan's governing elite to Christianity. Pederasty had become deeply institutionalized among the daimyo and samurai, prompting comparisons to ancient Pederasty in ancient Greece, Athens and Sparta. The Jesuits' strong condemnation of the practice alienated many of Japan's ruling class, creating further barriers to their acceptance of Christianity. Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shogun, was known for his interest in pederasty.

From the mid-Edo period, wealthy and farmers could join the samurai class by giving a large sum of money to an impoverished to be adopted into a samurai family and inherit the samurai's position and stipend. The amount of money given to a ''gokenin'' varied according to his position: 1,000 ''ryo'' for a and 500 ''ryo'' for an Some of their descendants were promoted to and held important positions in the shogunate. Some of the peasants' children were promoted to the samurai class by serving in the office. ''Kachi'' could change jobs and move into the lower classes, such as ''chōnin''. For example, Takizawa Bakin became a ''chōnin'' by working for Tsutaya Jūzaburō.

In the late 1500s, trade between Japan and Southeast Asia accelerated and increased exponentially when the Tokugawa shogunate was established in the early 1600s. The destinations of the trading ships, the red seal ships, were Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, etc. Many Japanese moved to Southeast Asia and established Japanese towns there. Many samurai, or rōnin, who had lost their masters after the Battle of Sekigahara, lived in the Japanese towns. The Spaniards in the Philippines, the Dutch of the Dutch East India Company, and the Thais of the Ayutthaya Kingdom saw the value of these samurai as mercenaries and recruited them. The most famous of these mercenaries was Yamada Nagamasa. He was originally a palanquin bearer who belonged to the lowest end of the samurai class, but he rose to prominence in the Ayutthaya Kingdom, now in southern Thailand, and became governor of the Nakhon Si Thammarat Kingdom. When the policy of national isolation (''sakoku'') was established in 1639, trade between Japan and Southeast Asia ceased, and records of Japanese activities in Southeast Asia were lost for many years after 1688.

In the late 1500s, trade between Japan and Southeast Asia accelerated and increased exponentially when the Tokugawa shogunate was established in the early 1600s. The destinations of the trading ships, the red seal ships, were Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, etc. Many Japanese moved to Southeast Asia and established Japanese towns there. Many samurai, or rōnin, who had lost their masters after the Battle of Sekigahara, lived in the Japanese towns. The Spaniards in the Philippines, the Dutch of the Dutch East India Company, and the Thais of the Ayutthaya Kingdom saw the value of these samurai as mercenaries and recruited them. The most famous of these mercenaries was Yamada Nagamasa. He was originally a palanquin bearer who belonged to the lowest end of the samurai class, but he rose to prominence in the Ayutthaya Kingdom, now in southern Thailand, and became governor of the Nakhon Si Thammarat Kingdom. When the policy of national isolation (''sakoku'') was established in 1639, trade between Japan and Southeast Asia ceased, and records of Japanese activities in Southeast Asia were lost for many years after 1688.

In 1582, three ''Kirishitan'' ''daimyō'', Ōtomo Sōrin, Ōmura Sumitada, and Arima Harunobu, sent a group of boys, their own blood relatives and retainers, to Europe as Tenshō embassy, Japan's first diplomatic mission to Europe. They had audiences with King Philip II of Spain, Pope Gregory XIII, and Pope Sixtus V. The mission returned to Japan in 1590, but its members were forced to renounce, be exiled, or be executed, due to the Tokugawa shogunate's suppression of Christianity.

In 1612, Hasekura Tsunenaga, a vassal of the ''daimyo'' Date Masamune, led a diplomatic mission and had an audience with King Philip III of Spain, presenting him with a letter requesting trade, and he also had an audience with Pope Paul V in Rome. He returned to Japan in 1620, but news of the Tokugawa shogunate's suppression of Christianity had already reached Europe, and trade did not take place due to the Tokugawa shogunate's policy of ''sakoku''. In the town of Coria del Rio in Spain, where the diplomatic mission stopped, there were 600 people with the surnames Japon or Xapon as of 2021, and they have passed on the folk tale that they are the descendants of the samurai who remained in the town.

At the end of the Edo period (Bakumatsu era), when Matthew C. Perry came to Japan in 1853 and the ''sakoku'' policy was abolished, six diplomatic missions were sent to the United States and European countries for diplomatic negotiations. The most famous were the Japanese Embassy to the United States, US mission in 1860 and the First Japanese Embassy to Europe (1862), European missions in 1862 and Second Japanese Embassy to Europe (1864), 1864. Fukuzawa Yukichi, who participated in these missions, is most famous as a leading figure in the modernization of Japan, and his portrait was selected for the 10,000 yen note.

In 1582, three ''Kirishitan'' ''daimyō'', Ōtomo Sōrin, Ōmura Sumitada, and Arima Harunobu, sent a group of boys, their own blood relatives and retainers, to Europe as Tenshō embassy, Japan's first diplomatic mission to Europe. They had audiences with King Philip II of Spain, Pope Gregory XIII, and Pope Sixtus V. The mission returned to Japan in 1590, but its members were forced to renounce, be exiled, or be executed, due to the Tokugawa shogunate's suppression of Christianity.

In 1612, Hasekura Tsunenaga, a vassal of the ''daimyo'' Date Masamune, led a diplomatic mission and had an audience with King Philip III of Spain, presenting him with a letter requesting trade, and he also had an audience with Pope Paul V in Rome. He returned to Japan in 1620, but news of the Tokugawa shogunate's suppression of Christianity had already reached Europe, and trade did not take place due to the Tokugawa shogunate's policy of ''sakoku''. In the town of Coria del Rio in Spain, where the diplomatic mission stopped, there were 600 people with the surnames Japon or Xapon as of 2021, and they have passed on the folk tale that they are the descendants of the samurai who remained in the town.

At the end of the Edo period (Bakumatsu era), when Matthew C. Perry came to Japan in 1853 and the ''sakoku'' policy was abolished, six diplomatic missions were sent to the United States and European countries for diplomatic negotiations. The most famous were the Japanese Embassy to the United States, US mission in 1860 and the First Japanese Embassy to Europe (1862), European missions in 1862 and Second Japanese Embassy to Europe (1864), 1864. Fukuzawa Yukichi, who participated in these missions, is most famous as a leading figure in the modernization of Japan, and his portrait was selected for the 10,000 yen note.

The dissolution of the ''daimyo'' class made the samurai defunct as a feudal retainer caste, so the Meiji government began repealing their special rights and privileges. In 1869, the government reclassified high-ranking samurai as ''shizoku'' (warriors) and lower status samurai as ''sotsuzoku'' (foot soldiers). In 1872, the ''sotsu'' rank was abolished and the ''sotsuzoku'' were reclassified as ''shizoku''. In 1871, the government banned the samurai topknot (the ''chonmage''). From 1873 to 1879, the government started taxing the stipends and transformed them into interest-bearing government bonds. The main goal was to provide enough financial liquidity to enable former samurai to invest in land and industry. In 1876, the government forbade anyone outside the military to wear swords even if they were of samurai lineage, and repealed the right of a samurai to strike an insolent commoner with potentially lethal force (''kiri-sute gomen'').

Most samurai accepted these reforms. In fact the Meiji leadership was composed mostly of samurai. Although they were no longer entitled to rule, many former samurai were offered positions in the new civilian government because they were typically well-educated. Others were offered teaching positions in the new public education system.

But some samurai could not be placated, leading to sporadic samurai rebellions. The largest of these was the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. Many disgruntled samurai flocked to Satsuma where the radical samurai Saigo Takamori had set up academies where he taught samurai the ways of modern war and his militant right-wing beliefs. The Meiji reforms of 1873 gave farmers ownership rights so that the government could tax them directly. This eliminated the traditional feudal role of the samurai landowners, of which Satsuma had an exceptionally high number. Saigo therefore found a lot of sympathetic samurai in Satsuma. The imperial government feared an insurrection and sent a task force to disarm Takamori's growing paramilitary force. In response, Takamori marched his army on Tokyo. The rebel samurai were defeated by the imperial army, which was composed mostly of commoners. Both armies were equipped with modern weapons. After this rebellion was quashed, the Meiji government faced no further challenges to its authority.

In 1947, the ''shizoku'' class was abolished.

The dissolution of the ''daimyo'' class made the samurai defunct as a feudal retainer caste, so the Meiji government began repealing their special rights and privileges. In 1869, the government reclassified high-ranking samurai as ''shizoku'' (warriors) and lower status samurai as ''sotsuzoku'' (foot soldiers). In 1872, the ''sotsu'' rank was abolished and the ''sotsuzoku'' were reclassified as ''shizoku''. In 1871, the government banned the samurai topknot (the ''chonmage''). From 1873 to 1879, the government started taxing the stipends and transformed them into interest-bearing government bonds. The main goal was to provide enough financial liquidity to enable former samurai to invest in land and industry. In 1876, the government forbade anyone outside the military to wear swords even if they were of samurai lineage, and repealed the right of a samurai to strike an insolent commoner with potentially lethal force (''kiri-sute gomen'').

Most samurai accepted these reforms. In fact the Meiji leadership was composed mostly of samurai. Although they were no longer entitled to rule, many former samurai were offered positions in the new civilian government because they were typically well-educated. Others were offered teaching positions in the new public education system.

But some samurai could not be placated, leading to sporadic samurai rebellions. The largest of these was the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. Many disgruntled samurai flocked to Satsuma where the radical samurai Saigo Takamori had set up academies where he taught samurai the ways of modern war and his militant right-wing beliefs. The Meiji reforms of 1873 gave farmers ownership rights so that the government could tax them directly. This eliminated the traditional feudal role of the samurai landowners, of which Satsuma had an exceptionally high number. Saigo therefore found a lot of sympathetic samurai in Satsuma. The imperial government feared an insurrection and sent a task force to disarm Takamori's growing paramilitary force. In response, Takamori marched his army on Tokyo. The rebel samurai were defeated by the imperial army, which was composed mostly of commoners. Both armies were equipped with modern weapons. After this rebellion was quashed, the Meiji government faced no further challenges to its authority.

In 1947, the ''shizoku'' class was abolished.

The translator of ''Hagakure'', William Scott Wilson, observed examples of warrior emphasis on death in clans other than Yamamoto's: "he (Takeda Shingen) was a strict disciplinarian as a warrior, and there is an exemplary story in the ''Hagakure'' relating his execution of two brawlers, not because they had fought, but because they had not fought to the death".

The translator of ''Hagakure'', William Scott Wilson, observed examples of warrior emphasis on death in clans other than Yamamoto's: "he (Takeda Shingen) was a strict disciplinarian as a warrior, and there is an exemplary story in the ''Hagakure'' relating his execution of two brawlers, not because they had fought, but because they had not fought to the death".

In general, samurai, aristocrats, and priests had a very high literacy rate in kanji. Recent studies have shown that literacy in kanji among other groups in society was somewhat higher than previously understood. For example, court documents, birth and death records and marriage records from the Kamakura period, submitted by farmers, were prepared in Kanji. Both the kanji literacy rate and skills in math improved toward the end of Kamakura period.Matsura, Yoshinori Fukuiken-shi 2 (Tokyo: Sanshusha, 1921)

Some samurai had ''buke bunko'', or "warrior library", a personal library that held texts on strategy, the science of warfare, and other documents that would have proved useful during the warring era of feudal Japan. One such library held 20,000 volumes. The upper class had ''Kuge bunko'', or "family libraries", that held classics, Buddhist sacred texts, and family histories, as well as genealogical records.

In general, samurai, aristocrats, and priests had a very high literacy rate in kanji. Recent studies have shown that literacy in kanji among other groups in society was somewhat higher than previously understood. For example, court documents, birth and death records and marriage records from the Kamakura period, submitted by farmers, were prepared in Kanji. Both the kanji literacy rate and skills in math improved toward the end of Kamakura period.Matsura, Yoshinori Fukuiken-shi 2 (Tokyo: Sanshusha, 1921)

Some samurai had ''buke bunko'', or "warrior library", a personal library that held texts on strategy, the science of warfare, and other documents that would have proved useful during the warring era of feudal Japan. One such library held 20,000 volumes. The upper class had ''Kuge bunko'', or "family libraries", that held classics, Buddhist sacred texts, and family histories, as well as genealogical records.

Maintaining the household was the main duty of women of the samurai class. This was especially crucial during early feudal Japan, when warrior husbands were often traveling abroad or engaged in clan battles. The wife, or ''okugatasama'' (meaning: one who remains in the home), was left to manage all household affairs, care for the children, and perhaps even defend the home forcibly. For this reason, many women of the samurai class were trained in wielding a polearm called a ''naginata'' or a special knife called the ''Kaiken (dagger), kaiken'' in an art called ''tantojutsu'' (lit. the skill of the knife), which they could use to protect their household, family, and honor if the need arose. There were women who actively engaged in battles alongside male samurai in Japan, although most of these female warriors were not formal samurai.

A samurai's daughter's greatest duty was political marriage. These women married members of enemy clans of their families to form diplomatic relationships. These alliances were stages for many intrigues, wars and tragedies throughout Japanese history. A woman could divorce her husband if he did not treat her well and also if he was a traitor to his wife's family. A famous case was that of Tokuhime (Oda), Oda Tokuhime (daughter of

Maintaining the household was the main duty of women of the samurai class. This was especially crucial during early feudal Japan, when warrior husbands were often traveling abroad or engaged in clan battles. The wife, or ''okugatasama'' (meaning: one who remains in the home), was left to manage all household affairs, care for the children, and perhaps even defend the home forcibly. For this reason, many women of the samurai class were trained in wielding a polearm called a ''naginata'' or a special knife called the ''Kaiken (dagger), kaiken'' in an art called ''tantojutsu'' (lit. the skill of the knife), which they could use to protect their household, family, and honor if the need arose. There were women who actively engaged in battles alongside male samurai in Japan, although most of these female warriors were not formal samurai.

A samurai's daughter's greatest duty was political marriage. These women married members of enemy clans of their families to form diplomatic relationships. These alliances were stages for many intrigues, wars and tragedies throughout Japanese history. A woman could divorce her husband if he did not treat her well and also if he was a traitor to his wife's family. A famous case was that of Tokuhime (Oda), Oda Tokuhime (daughter of

File:Kasuga no Tsubone (c. 1880).jpg, ''Lady Kasuga, Kasuga no Tsubone fighting robbers'' – Adachi Ginkō, Adachi Ginko ()

File:Hangaku Gozen by Yoshitoshi.jpg, Hangaku Gozen by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, Yoshitoshi,

File:Onodera Junai no tsuma 斧寺重内の妻 (No. 4, The Wife of Onodera Junai) (BM 2008,3037.15404).jpg, Japanese woman preparing for jigai, ritual suicide

File:Tomita Nobutaka and his wife Yuki no Kata defend Tsu Castle by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 1885.png, Yuki no Kata defending Tsu Castle. 18th century

File:Femme-samurai-p1000704.jpg, A samurai class woman

online

* Ansart, Olivier. "Lust, Commerce and Corruption: An Account of What I Have Seen and Heard by an Edo Samurai". ''Asian Studies Review'' 39.3 (2015): 529–530. * Benesch, Oleg. ''Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan'' (Oxford UP, 2014). * Benesch, Oleg. "Comparing Warrior Traditions: How the Janissaries and Samurai Maintained Their Status and Privileges During Centuries of Peace." ''Comparative Civilizations Review'' 55.55 (2006): 6:37–5

Online

* * Clements, Jonathan. ''A Brief History of the Samurai'' (Running Press, 2010) * * Cummins, Antony, and Mieko Koizumi. ''The Lost Samurai School'' (North Atlantic Books, 2016) 17th century Samurai textbook on combat; heavily illustrated. * * * Hubbard, Ben. ''The Samurai Warrior: The Golden Age of Japan's Elite Warriors 1560–1615'' (Amber Books, 2015). * Jaundrill, D. Colin. ''Samurai to Soldier: Remaking Military Service in Nineteenth-Century Japan'' (Cornell UP, 2016). * * Kinmonth, Earl H. ''Self-Made Man in Meiji Japanese Thought: From Samurai to Salary Man'' (1981) 385pp. * Ogata, Ken. "End of the Samurai: A Study of Deinstitutionalization Processes". ''Academy of Management Proceedings'' Vol. 2015. No. 1. * * Thorne, Roland. ''Samurai films'' (Oldcastle Books, 2010). * Turnbull, Stephen. ''The Samurai: A Military History'' (1996). * Kure, Mitsuo. ''Samurai: an illustrated history'' (2014). *

online

The Samurai Archives Japanese History page

History of the Samurai

– Japan: Memoirs of a Secret Empire

Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan

Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties {{Authority control Samurai, 12th-century establishments in Japan 1879 disestablishments in Japan Combat occupations Japanese caste system Japanese historical terms Japanese nobility Japanese warriors Noble titles Obsolete occupations

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court downsized the national army and delegated the security of the countryside to these privately trained warriors. Eventually the samurai clans grew so powerful that they became the ''de facto'' rulers of the country. In the aftermath of the Gempei War

The was a national civil war between the Taira and Minamoto clans during the late Heian period of Japan. It resulted in the downfall of the Taira and the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate under Minamoto no Yoritomo, who appointed himself ...

(1180-1185), Japan formally passed into military rule with the founding of the first shogunate

, officially , was the title of the military rulers of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, except during parts of the Kamak ...

.

The status of samurai became heredity by the mid-eleventh century. By the start of the Edo period, the shogun had disbanded the warrior-monk orders and peasant conscript system, leaving the samurai as the only men in the country permitted to carry weapons at all times. Because the Edo period was a time of peace, many samurai neglected their warrior training and focused on peacetime activities such as administration or art, but they were still required to wear their swords as a sign of their status.

In 1853, the United States forced Japan to open its borders to foreign trade under the threat of military action. Fearing an eventual invasion, the Japanese abandoned feudalism for capitalism so that they could industrialize and build a modern army to defend itself. The samurai were retainers to the ''daimyo'', so when the ''daimyo'' class was abolished and power was re-centralized at the imperial court, the samurai class in turn became defunct. The introduction of modern firearms rendered the traditional weapons of the samurai obsolete, and as firearms are easy enough for peasant conscripts to master, Japan had no more need for a specialist warrior caste. By 1876 their special rights and privileges had all been abolished.

Terminology

The proper term for Japanese warriors is , meaning 'warrior', but also could be interchangeable with , meaning 'military family', and later could refer to the whole class of professional warriors. Especially in the west, samurai is used synonymous with bushi, but they can have different meanings depending on context. The word "samurai" originally referred to domestic servants and did not have military connotations. As the term gained military connotations in the 12th century, it referred to landless foot soldiers. The samurai were subservient to gokenin who held land from which they took their name. According to Michael Wert, "a warrior of elite stature in pre-seventeenth-century Japan would have been insulted to be called a 'samurai'". According to Morillo, the term marked social function, and not military function.Morillo, Stephen. �Milites, Knights and Samurai: Military Terminology, Comparative History, and the Problem of Translation

” In ''The Normans and Their Adversaries at War'', ed. Richard Abels and Bernard Bachrach, 167–84. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2001. "Finally there is the term samurai. This noun derives from the verb saburau, to serve, and it is again a social marker, though it marks social function and not class, It means a retainer of a lord - usually, in the sixteenth century, the retainer of a daimyo, a leader of one of the essentially independent states of the Sengoku, or warring states period. It has no functional component - all sorts of soldiers, including pikemen, bowmen, musketeers and horsemen were samurai" In the Tokugawa period, the terms were roughly interchangeable, as the military class was legally limited to the retainers of the shogun or daimyo. However, strictly speaking samurai referred to higher ranking retainers, although the cut off between samurai and other military retainers varied from domain to domain. Also usage varied by class, with commoners referring to all sword carrying men as samurai, regardless of rank.

History

Rise of the warrior clans (700 - 1180 AD)

At the start of the 8th century AD, Japan's government was highly centralized at the imperial court, whose bureaucracy was inspired by T'ang dynasty China. All land at first belonged to the emperor, but in the middle of the 8th century, the government instituted a major reform which allowed individuals to claim private ownership of new farmland that they had reclaimed from swampland or forests. This spurred wealthy people to start reclaiming farmland, which was necessary to feed Japan's growing population. During the 11th and 12th centuries, samurai became conspicuously involved in land reclamation, thereby becoming a landowning class. Taxation during the 8th century was high but temples, monasteries, shrines, and certain aristocrats obtained tax exemptions through their connections to the imperial court. To evade taxes, many landowners in the countryside donated their lands to these tax-exempt entities. The land would be registered in the name of said noble or temple and would become part of their tax-exempt estate but would still be used by the same person who originally owned it. The former owner, now a steward on his lord's estate, had to pay his lord an annual tribute that was less than what he would have had to pay the emperor in tax had he been the landowner. There was usually an agreement that when the supervisor died, his children would inherit his position. If the temple or lord cheated the steward somehow, the farmer could retaliate by exposing the scheme, which might have cost the temple or noble its tax-exempt privilege. It deprived the emperor of tax revenue. The emperors found it harder to commission people from the capital to go out and suppress banditry and lawlessness in the countryside. In the Heian period it was the habit of emperors to keep harems, and consequently the imperial family got so large it burdened the treasury. In the early 9th century AD,Emperor Saga

was the 52nd emperor of Japan, Emperor Saga, Saganoyamanoe Imperial Mausoleum, Imperial Household Agency according to the traditional order of succession. Saga's reign lasted from 809 to 823.

Traditional narrative

Saga was the second son of ...

expelled several dozen members from the imperial family, who formed two new clans: the Minamoto clan

was a Aristocracy (class), noble surname bestowed by the Emperors of Japan upon members of the Imperial House of Japan, imperial family who were excluded from the List of emperors of Japan, line of succession and demoted into the ranks of Nobili ...

(814 AD) and the Taira clan

The was one of the four most important Japanese clans, clans that dominated Japanese politics during the Heian period, Heian period of History of Japan, Japanese history – the others being the Minamoto clan, Minamoto, the Fujiwara clan, Fuji ...

(825 AD). Many wealthy provincial families married into the Minamotos and Tairas in order to acquire aristocratic status, and so the Tairas and Minamotos became big and wealthy clans.

Up until the late 8th century AD, Japan had a national conscript army. As peace settled in, the imperial court began dismantling the system, eventually ending it by 792 AD. Conscripts were seen as unreliable and poorly trained, to be used only in emergencies such as when the Chinese invaded. Conscript footsoldiers proved to be particularly ineffective in the Japanese' war with the Emishi

The were a group of people who lived in parts of northern Honshū in present-day Japan, especially in the Tōhoku region.

The first mention of the Emishi in literature that can be corroborated with outside sources dates to the 5th century AD, ...

, an ethnic minority in the north that relied on mounted warriors and were thus highly mobile. The deciding factor in most battles had been professional mounted archers who came from the wealthy families. The government didn't bother training conscripts in horsemanship as it required years to produce a good cavalryman. So it instead recruited men who already had these skills, acquired through private training funded by his family's wealth.Karl Friday. ''Hired Swords'', p. 39: "...fighting from horseback was an extraordinarily complex skill to master, one that required years of training and practice. It was simply impossible to produce first-rate cavalrymen out of short-term, peasant conscripts. ..The government expended minimal effort training ordinary conscripts as horsemen, preferring instead to rely on the talents of those who had acquired skills in mounted archery before their induction." Similarly, soldiers in the imperial army were expected to provide most of their own equipment. Wealthy men who could afford horses and archery training were promoted to elite units, whereas the poor were consigned to being footsoldiers. One's position in the army depended on wealth and status. The poor disliked military service for this reason, and because their farms often fell into decay with their absence, so there was popular support for ending conscription.

Thus with the downsizing of the national army and the decline in tax revenue, the emperors delegated the matter of security in the countryside to the burgeoning class of landed warriors. They had a personal incentive to suppress lawlessness in their own lands as it directly impacted their revenue. War and law enforcement became increasingly privatized affairs.

Kamakura shogunate

Two leading samurai houses, theMinamoto clan

was a Aristocracy (class), noble surname bestowed by the Emperors of Japan upon members of the Imperial House of Japan, imperial family who were excluded from the List of emperors of Japan, line of succession and demoted into the ranks of Nobili ...

and the Taira clan

The was one of the four most important Japanese clans, clans that dominated Japanese politics during the Heian period, Heian period of History of Japan, Japanese history – the others being the Minamoto clan, Minamoto, the Fujiwara clan, Fuji ...

, had both gained court positions and became rivals. In the aftermath of the Heiji Rebellion in 1160, the Tairas ended up with even more influence in the imperial court. Their leader, Taira no Kiyomori

was a military leader and '' kugyō'' of the late Heian period of Japan. He established the first samurai-dominated administrative government in the history of Japan.

Early life

Kiyomori was born in Japan, in 1118 as the first son of Taira ...

, became the first samurai ever to be given a senior rank in the imperial court. Members of the Minamoto and Taira clans had fought on both sides of the rebellion, but the Minamoto loyalists received smaller rewards than the Taira loyalists, and the Minamoto rebels received worse punishments than the Taira rebels. All this angered the Minamotos, and consequently political factions in the imperial court began to reform around clan affiliations rather than personal allegiances.

In 1180, Taira no Kiyomori installed his two-year old grandson (Emperor Antoku

was the 81st emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. His reign spanned the years from 1180 through 1185. His death marked the end of the Heian period and the beginning of the Kamakura period.

During this time, the Im ...

) on the throne, pushing aside older male heirs whose mothers were from the Minamoto family. This sparked a rebellion by the Minamotos, leading to the Gempei War

The was a national civil war between the Taira and Minamoto clans during the late Heian period of Japan. It resulted in the downfall of the Taira and the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate under Minamoto no Yoritomo, who appointed himself ...

(1180-1185). Minamoto no Yoritomo

was the founder and the first shogun of the Kamakura shogunate, ruling from 1192 until 1199, also the first ruling shogun in the history of Japan.Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Minamoto no Yoriie" in . He was the husband of Hōjō Masako ...

promised lands and administrative rights to warriors who swore allegiance to him. The Minamotos won the war and the Taira clan was effectively destroyed. In April 1185, the controversial child emperor was drowned by his own grandmother, who then committed suicide.

The new emperor, Emperor Go-Toba

was the 82nd emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. His reign spanned the years from 1183 through 1198.

This 12th-century sovereign was named after Emperor Toba, and ''go-'' (後), translates literally as "later"; ...

, was of Fujiwara lineage on his mother's side. Minamoto no Yoritomo didn't overthrow this emperor, but instead took over most of his authority, reducing the emperor to a figurehead. Yoritomo found it more expedient to set up a military government, staffed by samurai who fought for him. Thus began the age of the shoguns and seven centuries of military rule.

In 1185, Yoritomo obtained the right to appoint ''shugo

, commonly translated as ' ilitarygovernor', 'protector', or 'constable', was a title given to certain officials in feudal Japan. They were each appointed by the shogun to oversee one or more of the provinces of Japan. The position gave way to th ...

'' and ''jitō

were medieval territory stewards in Japan, especially in the Kamakura and Muromachi shogunates. Appointed by the shōgun, ''jitō'' managed manors, including national holdings governed by the '' kokushi'' or provincial governor. There were als ...

'', and was allowed to organize soldiers and police, and to collect a certain amount of tax. Initially, their responsibility was restricted to arresting rebels and collecting needed army provisions and they were forbidden from interfering with '' kokushi'' officials, but their responsibility gradually expanded. Thus, the warrior class began to gradually gain political power.

In 1190 he visited Kyoto and in 1192 became '' Sei'i Taishōgun'', establishing the Kamakura shogunate, or ''Kamakura bakufu''. Instead of ruling from Kyoto, he set up the shogunate in Kamakura

, officially , is a city of Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan. It is located in the Kanto region on the island of Honshu. The city has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 people per km2 over the tota ...

, near his base of power. "Bakufu" means "tent government", taken from the encampments the soldiers lived in, in accordance with the Bakufu's status as a military government.

The Kamakura period

The is a period of History of Japan, Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura shogunate, officially established in 1192 in Kamakura, Kanagawa, Kamakura by the first ''shōgun'' Minamoto no Yoritomo after the conclusion of the G ...

(1185–1333) is seen by some as the rise of the samurai as they were "entrusted with the security of the estates" and were symbols of the ideal warrior and citizen. The shogunate had its powerbase in the east, but also had authority over its warrior vassals all over the country. This allowed a subset of warriors to collaborate instead of just competing against each other. This began a gradual process that weakened the central authority to the advantage of the samurai.

In the late Kamakura period, even the most senior samurai began to wear , as the heavy and elegant were no longer respected. Until then, the body was the only part of the that was protected, but for higher-ranking samurai, the also came with a (helmet) and shoulder guards.式正の鎧・大鎧Costume Museum For lower-ranked samurai, the was introduced, the simplest style of armor that protected only the front of the torso and the sides of the abdomen. In the late Kamakura period, a new type of armor called appeared, in which the two ends of the were extended to the back to provide greater protection.

Mongol invasions

Shōni clan

was a family of Japanese nobles descended from the Fujiwara family, many of whom held high government offices in Kyūshū. Prior to the Kamakura period (1185–1333), "Shōni" was originally a title and post within the Kyūshū ( Dazaifu) gover ...

gather to defend against Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder and first emperor of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China. He proclaimed the ...

's Mongolian army during the first Mongol invasion of Japan in 1274.

File:Battle of Yashima Folding Screens Kano School.jpg, Battle of Yashima

Battle of Yashima (屋島の戦い) was one of the battles of the Genpei War on March 22, 1185, in the Heian period. It occurred in Sanuki Province (Shikoku), which is now Takamatsu, Kagawa.

Background

Following a long string of defeats, th ...

folding screens

Kamakura shogunate

The was the feudal military government of Japan during the Kamakura period from 1185 to 1333. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Kamakura-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia'', p. 459.

The Kamakura shogunate was established by Minamoto no Yori ...

. Zen Buddhism

Zen (; from Chinese: '' Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka ph ...

spread among the samurai in the 13th century and helped shape their standards of conduct, particularly in overcoming the fear of death and killing. Among the general populace Pure Land Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism or the Pure Land School ( zh, c=淨土宗, p=Jìngtǔzōng) is a broad branch of Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhism focused on achieving rebirth in a Pure land, Pure Land. It is one of the most widely practiced traditions of East Asi ...

was favored however.

In 1274, the Mongol-founded Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

in China sent a force of some 40,000 men and 900 ships to invade Japan in northern Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's four main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands (i.e. excluding Okinawa and the other Ryukyu (''Nansei'') Islands). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regio ...

. Japan mustered a mere 10,000 samurai to meet this threat. The invading army was harassed by major thunderstorms throughout the invasion, which aided the defenders by inflicting heavy casualties. The Yuan army was eventually recalled, and the invasion was called off. The Mongol invaders used small bombs, which was likely the first appearance of bombs and gunpowder in Japan.

The Japanese defenders recognized the possibility of a renewed invasion and began construction of a great stone barrier around Hakata Bay

is a bay in the northwestern part of Fukuoka city, on the Japanese island of Kyūshū. It faces the Tsushima Strait, and features beaches and a port, though parts of the bay have been reclaimed in the expansion of the city of Fukuoka. The ba ...

in 1276. Completed in 1277, this wall stretched for 20 kilometers around the bay. It later served as a strong defensive point against the Mongols. The Mongols attempted to settle matters in a diplomatic way from 1275 to 1279, but every envoy sent to Japan was executed.

Leading up to the second Mongolian invasion, Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder and first emperor of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China. He proclaimed the ...

continued to send emissaries to Japan, with five diplomats sent in September 1275 to Kyūshū. Hōjō Tokimune

of the Hōjō clan was the eighth ''shikken'' (officially regent of the shōgun, but ''de facto'' ruler of Japan) of the Kamakura shogunate (reigned 1268–84), known for leading the Japanese people, Japanese forces against the Mongol invasions ...

, the shikken

The was a senior government post held by members of the Hōjō clan, officially a regent of the shogunate. From 1199 to 1333, during the Kamakura period, the ''shikken'' served as the head of the ''bakufu'' (shogun's government). This era was ref ...

of the Kamakura shogun, responded by having the Mongolian diplomats brought to Kamakura and then beheading them. The graves of the five executed Mongol emissaries exist to this day in Kamakura at Tatsunokuchi. On 29 July 1279, five more emissaries were sent by the Mongol empire, and again beheaded, this time in Hakata. This continued defiance of the Mongol emperor set the stage for one of the most famous engagements in Japanese history.

In 1281, a Yuan army of 140,000 men with 5,000 ships was mustered for another invasion of Japan. Northern Kyūshū was defended by a Japanese army of 40,000 men. The Mongol army was still on its ships preparing for the landing operation when a typhoon hit north Kyūshū island. The casualties and damage inflicted by the typhoon, followed by the Japanese defense of the Hakata Bay barrier, resulted in the Mongols again being defeated.

The thunderstorms of 1274 and the typhoon of 1281 helped the samurai defenders of Japan repel the Mongol invaders despite being vastly outnumbered. These winds became known as ''kami-no-Kaze'', which literally translates as "wind of the gods". This is often given a simplified translation as "divine wind". The ''kami-no-Kaze'' lent credence to the Japanese belief that their lands were indeed divine and under supernatural protection.

The thunderstorms of 1274 and the typhoon of 1281 helped the samurai defenders of Japan repel the Mongol invaders despite being vastly outnumbered. These winds became known as ''kami-no-Kaze'', which literally translates as "wind of the gods". This is often given a simplified translation as "divine wind". The ''kami-no-Kaze'' lent credence to the Japanese belief that their lands were indeed divine and under supernatural protection.

Nanboku-chō and Muromachi period

In 1336,Ashikaga Takauji

also known as Minamoto no Takauji was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Ashikaga shogunate."Ashikaga Takauji" in ''Encyclopædia Britannica, The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. ...

, who opposed Emperor Godaigo, established the Ashikaga shogunate with Emperor Kōgon. As a result, the southern court, descended from Emperor Godaigo, and the northern court, descended from Emperor Kogon, were established side by side. This period of coexistence of the two dynasties is called the Nanboku-chō period

The , also known as the Northern and Southern Courts period, was a period in Japanese history between 1336-1392 CE, during the formative years of the Ashikaga shogunate, Muromachi (Ashikaga) shogunate. Ideologically, the two courts fought for 50 ...

, which corresponds to the beginning of the Muromachi period

The , also known as the , is a division of Japanese history running from approximately 1336 to 1573. The period marks the governance of the Muromachi or Ashikaga shogunate ( or ), which was officially established in 1338 by the first Muromachi ...

. The Northern Court, supported by the Ashikaga shogunate, had six emperors, and in 1392 the Imperial Court was reunited by absorbing the Southern Court, although the modern Imperial Household Agency

The (IHA) is an agency of the government of Japan in charge of state matters concerning the Imperial House of Japan, Imperial Family, and the keeping of the Privy Seal of Japan, Privy Seal and State Seal of Japan. From around the 8th century ...

considers the Southern Court to be the legitimate emperor. The rule of Japan by the Ashikaga shogunate lasted until the Onin War, which broke out in 1467.

From 1346 to 1358 during the Nanboku-cho period, the Ashikaga shogunate gradually expanded the authority of the , the local military and police officials established by the Kamakura shogunate, giving the ''Shugo'' jurisdiction over land disputes between and allowing the ''Shugo'' to receive half of all taxes from the areas they controlled. The ''Shugo'' shared their newfound wealth with the local samurai, creating a hierarchical relationship between the ''Shugo'' and the samurai, and the first early , called , appeared.

During the Nanboku-chō period, many lower-class foot soldiers called began to participate in battles, and the popularity of increased. During the Nanboku-chō and Muromachi periods, and became the norm, and senior samurai also began to wear by adding (helmet), (face armor), and gauntlet.甲冑の歴史(南北朝時代~室町時代)Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World. Issues of inheritance caused family strife as

primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn Legitimacy (family law), legitimate child to inheritance, inherit all or most of their parent's estate (law), estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some childre ...

became common, in contrast to the division of succession designated by law before the 14th century. Invasions of neighboring samurai territories became common to avoid infighting, and bickering among samurai was a constant problem for the Kamakura and Ashikaga shogunates.

Sengoku period

The outbreak of the Onin War, which began in 1467 and lasted about 10 years, devastatedKyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

and brought down the power of the Ashikaga shogunate. This plunged the country into the warring states period

The Warring States period in history of China, Chinese history (221 BC) comprises the final two and a half centuries of the Zhou dynasty (256 BC), which were characterized by frequent warfare, bureaucratic and military reforms, and ...

, in which ''daimyo

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and nominally to ...

'' (feudal lords) from different regions fought each other. This period corresponds to the late Muromachi period. There are about nine theories about the end of the Sengoku Period, the earliest being the year 1568, when Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. He was the and regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan. He is sometimes referred as the "Demon Daimyō" and "Demo ...

marched on Kyoto, and the latest being the suppression of the Shimabara Rebellion

The , also known as the or , was an rebellion, uprising that occurred in the Shimabara Domain of the Tokugawa shogunate in Japan from 17 December 1637 to 15 April 1638.

Matsukura Katsuie, the ''daimyō'' of the Shimabara Domain, enforced unpo ...

in 1638. Thus, the Sengoku Period overlaps with the Muromachi, Azuchi–Momoyama, and Edo period

The , also known as the , is the period between 1600 or 1603 and 1868 in the history of Japan, when the country was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and some 300 regional ''daimyo'', or feudal lords. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengok ...

s, depending on the theory. In any case, the Sengoku period was a time of large-scale civil wars throughout Japan.

''Daimyo'' who became more powerful as the shogunate's control weakened were called , and they often came from ''shugo daimyo'', , and . In other words, ''sengoku daimyo'' differed from ''shugo daimyo'' in that a ''sengoku daimyo'' was able to rule the region on his own, without being appointed by the shogun.

During this period, the traditional master-servant relationship between the lord and his vassals broke down, with the vassals eliminating the lord, internal clan and vassal conflicts over leadership of the lord's family, and frequent rebellion and puppetry by branch families against the lord's family. These events sometimes led to the rise of samurai to the rank of ''sengoku daimyo''. For example, Hōjō Sōun was the first samurai to rise to the rank of ''sengoku daimyo'' during this period.

''Daimyo'' who became more powerful as the shogunate's control weakened were called , and they often came from ''shugo daimyo'', , and . In other words, ''sengoku daimyo'' differed from ''shugo daimyo'' in that a ''sengoku daimyo'' was able to rule the region on his own, without being appointed by the shogun.

During this period, the traditional master-servant relationship between the lord and his vassals broke down, with the vassals eliminating the lord, internal clan and vassal conflicts over leadership of the lord's family, and frequent rebellion and puppetry by branch families against the lord's family. These events sometimes led to the rise of samurai to the rank of ''sengoku daimyo''. For example, Hōjō Sōun was the first samurai to rise to the rank of ''sengoku daimyo'' during this period. Uesugi Kenshin

, later known as , was a Japanese ''daimyō'' (magnate). He was born in Nagao clan, and after adoption into the Uesugi clan, ruled Echigo Province in the Sengoku period of Japan. He was one of the most powerful ''daimyō'' of the Sengoku period ...

was an example of a ''Shugodai'' who became ''sengoku daimyo'' by weakening and eliminating the power of the lord.

This period was marked by the loosening of samurai culture, with people born into other social strata sometimes making a name for themselves as warriors and thus becoming '' de facto'' samurai. One such example is Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods and regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: ...

, a well-known figure who rose from a peasant background to become a samurai, ''sengoku daimyo'', and '' kampaku'' (Imperial Regent).

From this time on, infantrymen called , who were mobilized from the peasantry, were mobilized in even greater numbers than before, and the importance of the infantry, which had begun in the Nanboku-chō period, increased even more.''歴史人'' September 2020. pp.40–41. When matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of flammable cord or twine that is in contact with the gunpowder through a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or Tri ...

s were introduced from Portugal in 1543, Japanese swordsmiths immediately began to improve and mass-produce them. The Japanese matchlock was named after the Tanegashima island, which is believed to be the place where it was first introduced to Japan. By the end of the Sengoku Period, there were hundreds of thousands of arquebuses in Japan and a large army of nearly 100,000 men clashing with each other.

On the battlefield, began to fight in close formation, using (spear) and . As a result, , (bow), and became the primary weapons on the battlefield. The , which was difficult to maneuver in close formation, and the long, heavy fell into disuse and were replaced by the , which could be held short, and the short, light , which appeared in the Nanboku-cho period and gradually became more common. The was often cut off from the hilt and shortened to make a . The , which had become inconvenient for use on the battlefield, was transformed into a symbol of authority carried by high-ranking samurai.Basic knowledge of naginata and nagamaki.Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken WorldArms for battle – spears, swords, bows.

Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken WorldKazuhiko Inada (2020), ''Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords''. p42. Although the had become even more obsolete, some ''sengoku daimyo'' dared to organize assault and kinsmen units composed entirely of large men equipped with to demonstrate the bravery of their armies.Kazuhiko Inada (2020), ''Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords''. p39. These changes in the aspect of the battlefield during the Sengoku period led to the emergence of the style of armor, which improved the productivity and durability of armor. In the history of Japanese armor, this was the most significant change since the introduction of the and in the Heian period. In this style, the number of parts was reduced, and instead armor with eccentric designs became popular.

Costume Museum By the end of the Sengoku period, allegiances between warrior vassals, also known as military retainers, and lords were solidified. Vassals would serve lords in exchange for material and intangible advantages, in keeping with

Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius ...

ideas imported from China between the seventh and ninth centuries.

These independent vassals who held land were subordinate to their superiors, who may be local lords or, in the Edo period, the shogun.

A vassal or samurai could expect monetary benefits, including land or money, from lords in exchange for their military services.

Azuchi–Momoyama period

The Azuchi-Momoyama period refers to the period when

The Azuchi-Momoyama period refers to the period when Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. He was the and regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan. He is sometimes referred as the "Demon Daimyō" and "Demo ...

and Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods and regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: ...

were in power. The name "Azuchi-Momoyama" comes from the fact that Nobunaga's castle, Azuchi Castle, was located in Azuchi, Shiga, and Fushimi Castle, where Hideyoshi lived after his retirement, was located in Momoyama. There are several theories as to when the Azuchi–Momoyama period began: 1568, when Oda Nobunaga entered Kyoto in support of Ashikaga Yoshiaki; 1573, when Oda Nobunaga expelled Ashikaga Yoshiaki from Kyoto; and 1576, when the construction of Azuchi Castle began. In any case, the beginning of the Azuchii–Momoyama period marked the complete end of the rule of the Ashikaga shogunate, which had been disrupted by the Onin War; in other words, it marked the end of the Muromachi period.

Oda, Toyotomi, and Tokugawa

Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. He was the and regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan. He is sometimes referred as the "Demon Daimyō" and "Demo ...

was the well-known lord of the Nagoya area (once called Owari Province) and an exceptional example of a samurai of the Sengoku period. He came within a few years of, and laid down the path for his successors to follow, the reunification of Japan under a new ''bakufu'' (shogunate).

Oda Nobunaga made innovations in the fields of organization and war tactics, made heavy use of arquebuses, developed commerce and industry, and treasured innovation. Consecutive victories enabled him to end the Ashikaga Bakufu and disarm of the military powers of the Buddhist monks, which had inflamed futile struggles among the populace for centuries. Attacking from the "sanctuary" of Buddhist temples, they were constant headaches to any warlord and even the emperor, who tried to control their actions. He died in 1582 when one of his generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, turned upon him with his army.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods and regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: ...

and Tokugawa Ieyasu, who founded the Tokugawa shogunate, were loyal followers of Nobunaga. Hideyoshi began as a peasant and became one of Nobunaga's top generals, and Ieyasu had shared his childhood with Nobunaga. Hideyoshi defeated Mitsuhide within a month and was regarded as the rightful successor of Nobunaga by avenging the treachery of Mitsuhide. These two were able to use Nobunaga's previous achievements on which build a unified Japan and there was a saying: "The reunification is a rice cake; Oda made it. Hashiba shaped it. In the end, only Ieyasu tastes it." (Hashiba is the family name that Toyotomi Hideyoshi used while he was a follower of Nobunaga.)

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who became a grand minister in 1586, created a law that non-samurai were not allowed to carry weapons, which the samurai caste codified as permanent and hereditary, thereby ending the social mobility of Japan, which lasted until the dissolution of the Edo shogunate by the Meiji revolutionaries.

The distinction between samurai and non-samurai was so obscure that during the 16th century, most male adults in any social class (even small farmers) belonged to at least one military organization of their own and served in wars before and during Hideyoshi's rule. It can be said that an "all against all" situation continued for a century. The authorized samurai families after the 17th century were those that chose to follow Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu. Large battles occurred during the change between regimes, and a number of defeated samurai were destroyed, went ''rōnin'' or were absorbed into the general populace.

During the Azuchi–Momoyama period (late Sengoku period), "samurai" often referred to , the lowest-ranking ''bushi'', as exemplified by the provisions of the temporary law Separation Edict enacted by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1591. This law regulated the transfer of status classes:samurai (''wakatō''), , , and . These four classes and the ''ashigaru'' were and peasants employed by the ''bushi'' and fell under the category of . In times of war, samurai (''wakatō'') and ''ashigaru'' were fighters, while the rest were porters. Generally, samurai (''wakatō'') could take family names, while some ''ashigaru'' could, and only samurai (''wakatō'') were considered samurai class. ''Wakatō'', like samurai, had different definitions in different periods, meaning a young ''bushi'' in the Muromachi period and a rank below and above ''ashigaru'' in the Edo period.

Invasions of Korea

In 1592 and again in 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, aiming to invade China through Korea, mobilized an army of 160,000 peasants and samurai and Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), deployed them to Korea in one of the largest military endeavors in Eastern Asia until the late 19th century. Taking advantage of arquebus mastery and extensive wartime experience from the Sengoku period, Japanese samurai armies made major gains in most of Korea. A few of the famous samurai generals of this war were Katō Kiyomasa, Konishi Yukinaga, and Shimazu Yoshihiro. Katō Kiyomasa advanced to Orangkai territory (present-day Manchuria) bordering Korea to the northeast and crossed the border into northern China.

Kiyomasa withdrew back to Korea after retaliatory counterattacks from the Jurchen people, Jurchens in the area, whose castles his forces had raided. Shimazu Yoshihiro led some 7,000 samurai into battle, and despite being heavily outnumbered, defeated a host of allied Ming dynasty, Ming and Korean forces at the Battle of Sacheon (1598), Battle of Sacheon in 1598. Yoshihiro was feared as ''Oni-Shimazu'' ("Shimazu ogre") and his nickname spread across Korea and into China.

In 1592 and again in 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, aiming to invade China through Korea, mobilized an army of 160,000 peasants and samurai and Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), deployed them to Korea in one of the largest military endeavors in Eastern Asia until the late 19th century. Taking advantage of arquebus mastery and extensive wartime experience from the Sengoku period, Japanese samurai armies made major gains in most of Korea. A few of the famous samurai generals of this war were Katō Kiyomasa, Konishi Yukinaga, and Shimazu Yoshihiro. Katō Kiyomasa advanced to Orangkai territory (present-day Manchuria) bordering Korea to the northeast and crossed the border into northern China.

Kiyomasa withdrew back to Korea after retaliatory counterattacks from the Jurchen people, Jurchens in the area, whose castles his forces had raided. Shimazu Yoshihiro led some 7,000 samurai into battle, and despite being heavily outnumbered, defeated a host of allied Ming dynasty, Ming and Korean forces at the Battle of Sacheon (1598), Battle of Sacheon in 1598. Yoshihiro was feared as ''Oni-Shimazu'' ("Shimazu ogre") and his nickname spread across Korea and into China.