Sakhalin Husky Jiro on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

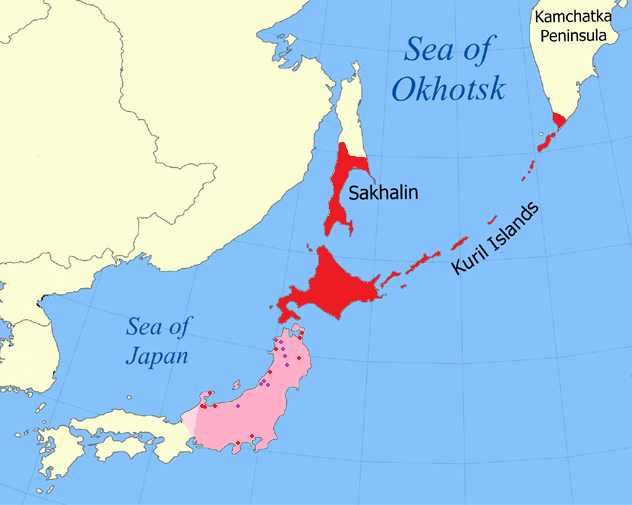

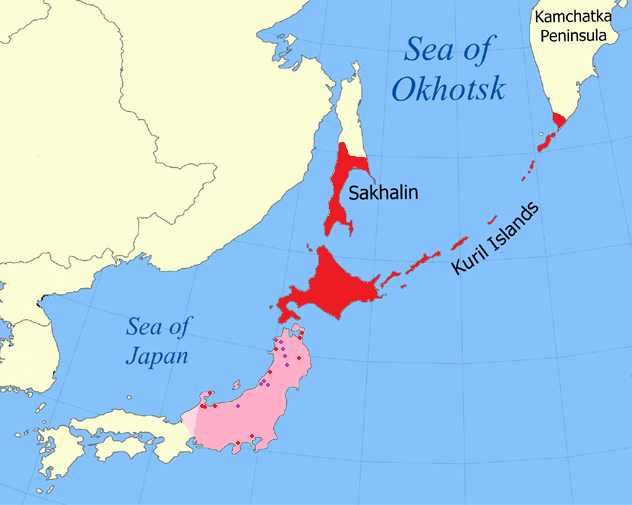

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, p=səxɐˈlʲin) is an island in

Humans lived on Sakhalin in the

Humans lived on Sakhalin in the

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped Cape Patience and Cape Aniva on the island's east coast in 1643. The

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped Cape Patience and Cape Aniva on the island's east coast in 1643. The

On the basis of its belief that it was an extension of Hokkaido, both geographically and culturally, Japan again proclaimed sovereignty over the whole island (as well as the

On the basis of its belief that it was an extension of Hokkaido, both geographically and culturally, Japan again proclaimed sovereignty over the whole island (as well as the

Japanese forces invaded and occupied Sakhalin in the closing stages of the

Japanese forces invaded and occupied Sakhalin in the closing stages of the

On 1 September 1983,

On 1 September 1983,

– an article in the ''

File:Sakhalin and her surroundings English ver.png, Sakhalin and its surroundings

File:Кекуры Мыса Великан 3.jpg, Velikan Cape, Sakhalin

File:Хребет Жданко и бухта Тихая.jpg, Zhdanko Mountain Ridge

According to the 1897 census, Sakhalin had a population of 28,113, of which 56.2% were Russians, 8.4%

According to the 1897 census, Sakhalin had a population of 28,113, of which 56.2% were Russians, 8.4%

The whole of the island is covered with dense

The whole of the island is covered with dense

File:Sakhalin Train.jpg, A passenger train in

The economy of Sakhalin relies primarily on

The economy of Sakhalin relies primarily on

Northeast Asia

Northeast Asia or Northeastern Asia is a geographical Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia. Its northeastern landmass and islands are bounded by the Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean.

The term Northeast Asia was popularized during the 1930s by Ame ...

. Its north coast lies off the southeastern coast of Khabarovsk Krai

Khabarovsk Krai (, ) is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject (a krai) of Russia. It is located in the Russian Far East and is administratively part of the Far Eastern Federal District. The administrative centre of the krai is the types of ...

in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, while its southern tip lies north of the Japanese island of Hokkaido

is the list of islands of Japan by area, second-largest island of Japan and comprises the largest and northernmost prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own list of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō fr ...

. An island of the West Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, Sakhalin divides the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk; Historically also known as , or as ; ) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands on the southeast, Japan's island of Hokkaido on the sou ...

to its east from the Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it ...

to its southwest. It is administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast

Sakhalin Oblast ( rus, Сахали́нская о́бласть, r=Sakhalinskaya oblastʹ, p=səxɐˈlʲinskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast) comprising the island of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in the Russian ...

and is the largest island of Russia, with an area of . The island has a population of roughly 500,000, the majority of whom are Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

. The indigenous peoples

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

of the island are the Ainu, Oroks

Oroks (''Ороки'' in Russian; self-designation: ''Ulta, Ulcha''), sometimes called Uilta, are a people in the Sakhalin Oblast (mainly the eastern part of the island) in Russia. The Orok language belongs to the Southern group of the Tungus ...

, and Nivkhs

The Nivkh, or Gilyak (also Nivkhs or Nivkhi, or Gilyaks; ethnonym: Нивхгу, ''Nʼivxgu'' (Amur) or Ниғвңгун, ''Nʼiɣvŋgun'' (E. Sakhalin) "the people"), are an indigenous ethnic group inhabiting the northern half of Sakhalin Islan ...

, who are now present in very small numbers.

The island's name is derived from the Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic peoples, Tungusic East Asian people, East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized Ethnic minorities in China, ethnic minority in China and the people from wh ...

word ''Sahaliyan'' (), which was the name of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

city of Aigun

Aigun ( zh, s=瑷珲, t=璦琿, p=Ài Hún; Manchu: ''aihūn''; ) was a historic Chinese town in northern Manchuria, situated on the right bank of the Amur River, some south (downstream) from the central urban area of Heihe (which is across the ...

. The Ainu people of Sakhalin paid tribute to the Yuan, Ming

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of China ruled by the Han people, t ...

, and Qing

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

dynasties and accepted official appointments from them. Sometimes the relationship was forced but control from dynasties in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

was loose for the most part.

The ownership of the island has been contested during the past millienium, with China, Russia, and Japan all making claims on the territory at different times. Over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries it was Russia and Japan, and the disputes sometimes involved military conflicts and divisions of the island between the two powers. In 1875, Japan ceded its claims to Russia in exchange for the northern Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands are a volcanic archipelago administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the Russian Far East. The islands stretch approximately northeast from Hokkaido in Japan to Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, separating the ...

. In 1897 more than half of the population were Russians and other European and Asian minorities. In 1905, following the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

, the island was divided, with Southern Sakhalin going to Japan. After the Siberian intervention, Japan invaded the northern parts of Sakhalin, and ruled the entire island from 1918 to 1925. Russia has held all of the island since seizing

Seizings are a class of stopping knots used to semi-permanently bind together two ropes, two parts of the same rope, or rope and another object. Akin to lashings, they use string or small-stuff to produce friction and leverage to immobilize lar ...

the Japanese portion in the final days of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in 1945, as well as all of the Kurils. Japan no longer claims any of Sakhalin, although it does still claim the southern Kuril Islands. Most Ainu on Sakhalin moved to Hokkaido, to the south across the La Pérouse Strait

La Pérouse Strait (), or , is a strait dividing the southern part of the Russian island of Sakhalin from the northern part of the Japanese island of Hokkaidō, and connecting the Sea of Japan on the west with the Sea of Okhotsk on the east.

...

, when Japanese civilians were displaced from the island in 1949.

Etymology

Sakhalin has several names including ( ), ( zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島), ( mnc, ), (), (Nivkh

Nivkh or Amuric or Gilyak may refer to:

* Nivkh people (''Nivkhs'') or Gilyak people (''Gilyaks'')

* Nivkh languages or Gilyak languages

* Gilyak class gunboat, ''Gilyak'' class gunboat, such as the Russian gunboat Korietz#Second gunboat, second R ...

: ).

The Manchus

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) an ...

called it . , the word that has been borrowed in the form of "Sakhalin", means "black" in Manchu, means "river" and is the proper Manchu name of the Amur River

The Amur River () or Heilong River ( zh, s=黑龙江) is a perennial river in Northeast Asia, forming the natural border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China (historically the Outer and Inner Manchuria). The Amur ''proper'' is ...

.

The island was also called "Kuye Fiyaka". The word "Kuye" used by the Qing is "most probably related to ''kuyi'', the name given to the Sakhalin Ainu by their Nivkh and Nanai neighbors." When the Ainu migrated onto the mainland, the Chinese described a "strong Kui (or Kuwei, Kuwu, Kuye, Kugi, ''i.e.'' Ainu) presence in the area otherwise dominated by the Gilemi or Jilimi (Nivkh and other Amur peoples)." Related names were in widespread use in the region, for example the Kuril Ainu called themselves .

The origins of the traditional Japanese name, (), are unclear and multiple competing explanations have been proposed. These include:

* A borrowing of Mongolian ''karahoton'', meaning "distant fortress".

* A modification of ''Karahito'', meaning "Chinese person", from the presence of Chinese traders on the island.

* A derivation from dialect words meaning "prawns" or "many herring".

* An aphetic form of (''kamuy kar put ya mosir'') "The island created by God at the estuary".

The Japanese form 樺太 equates to ''Hwangt'ae'', an earlier name for the island now superseded by the transcription 사할린 ''Sahallin''.

The island was also historically referred to as "Tschoka" by European travelers in the late 18th century, such as Lapérouse and Langsdorff. This name is believed to derive from an obsolete endonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

used by Sakhalin Ainu

The Ainu in Russia are an Indigenous people of Siberia located in Sakhalin Oblast, Khabarovsk Krai and Kamchatka Krai. The Russian Ainu people (''Aine''; ), also called ''Kurile'' (курилы, ''kurily''), ''Kamchatka's Kurile'' (кам� ...

, possibly based on the word ' (, "we") in Sakhalin Ainu language

Sakhalin Ainu is an extinct Ainu language, or perhaps several Ainu languages, that was or were spoken on the island of Sakhalin, now part of Russia.

History and present situation

The Ainu of Sakhalin appear to have been present on Sakhalin ...

.

History

Early history

Humans lived on Sakhalin in the

Humans lived on Sakhalin in the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

Stone Age. Flint implements such as those found in Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

have been found at Dui and Kusunai

Ilyinskoye (, until 1946 Kusunai or is a rural locality ( selo) in Tomarinsky District, Sakhalin Oblast, Russia.

A settlement on the western coast of Sakhalin Island, by the mouth of the Kusunai River was founded in 1853 by Dmitry Orlov, howe ...

in great numbers, as well as polished stone hatchets similar to European examples, primitive pottery with decorations like those of the Olonets

Olonets (; , ; ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Olonetsky District of the Republic of Karelia, Russia, located on the Olonka River to the east of Lake Ladoga.

Geography

Olonets is located ...

, and stone weights used with fishing nets. A later population familiar with bronze left traces in earthen walls and kitchen-midden

A midden is an old dump for domestic waste. It may consist of animal bones, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and ecofacts associated with past human oc ...

s on Aniva Bay

Aniva Bay (Russian: Залив Анива (''Zaliv Aniva''), Japanese: 亜庭湾, Aniwa Bay, or Aniva Gulf) is located at the southern end of Sakhalin Island, Russia, north of the island of Hokkaidō, Japan. The largest city on the bay is Korsako ...

.

Indigenous people

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

of Sakhalin include the Ainu in the southern half, the Oroks

Oroks (''Ороки'' in Russian; self-designation: ''Ulta, Ulcha''), sometimes called Uilta, are a people in the Sakhalin Oblast (mainly the eastern part of the island) in Russia. The Orok language belongs to the Southern group of the Tungus ...

in the central region, and the Nivkhs

The Nivkh, or Gilyak (also Nivkhs or Nivkhi, or Gilyaks; ethnonym: Нивхгу, ''Nʼivxgu'' (Amur) or Ниғвңгун, ''Nʼiɣvŋgun'' (E. Sakhalin) "the people"), are an indigenous ethnic group inhabiting the northern half of Sakhalin Islan ...

in the north.

Yuan and Ming tributaries

After theMongols

Mongols are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, China ( Inner Mongolia and other 11 autonomous territories), as well as the republics of Buryatia and Kalmykia in Russia. The Mongols are the principal member of the large family o ...

conquered the Jin dynasty (1234), they suffered raids by the Nivkh

Nivkh or Amuric or Gilyak may refer to:

* Nivkh people (''Nivkhs'') or Gilyak people (''Gilyaks'')

* Nivkh languages or Gilyak languages

* Gilyak class gunboat, ''Gilyak'' class gunboat, such as the Russian gunboat Korietz#Second gunboat, second R ...

and Udege people

The Udege (; or , or Udihe, Udekhe, and Udeghe correspondingly) are a native people of the Primorsky Krai and Khabarovsk Krai regions in Russia. They live along the tributaries of the Ussuri, Amur, Khungari, and Anyuy Rivers. The Udege spea ...

s. In response, the Mongols established an administration post at Nurgan (present-day Tyr, Russia

Tyr () is a settlement in Ulchsky District of Khabarovsk Krai, Russia, located on the right bank of the Amur River, near the mouth of the Amgun River, about upstream from Nikolayevsk-on-Amur.

Tyr has been known as a historically Nivkh ...

) at the junction of the Amur

The Amur River () or Heilong River ( zh, s=黑龙江) is a perennial river in Northeast Asia, forming the natural border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China (historically the Outer Manchuria, Outer and Inner Manchuria). The Amur ...

and Amgun

The Amgun () is a river in Khabarovsk Krai, Russia that flows northeast and joins the river Amur from the left, 146 km upstream from its outflow into sea. The length of the river is . The area of its drainage basin, basin is . The Amgun is f ...

rivers in 1263, and forced the submission of the two peoples.

From the Nivkh perspective, their surrender to the Mongols essentially established a military alliance against the Ainu who had invaded their lands. According to the ''History of Yuan

The ''History of Yuan'' (), also known as the ''Yuanshi'', is one of the official Chinese historical works known as the '' Twenty-Four Histories'' of China. Commissioned by the court of the Ming dynasty, in accordance to political tradition, t ...

'', a group of people known as the ''Guwei'' ( zh, labels=no, t=骨嵬, p=Gǔwéi, the Nivkh name for Ainu) from Sakhalin invaded and fought with the Jilimi (Nivkh people) every year. On 30 November 1264, the Mongols attacked the Ainu. The Ainu resisted the Mongol invasions but by 1308 had been subdued. They paid tribute to the Mongol Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

at posts in Wuliehe, Nanghar, and Boluohe.

The Chinese Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

(1368–1644) placed Sakhalin under its "system for subjugated peoples" (''ximin tizhi''). From 1409 to 1411 the Ming established an outpost called the Nurgan Regional Military Commission

The Nurgan Regional Military Commission () was a Chinese administrative seat established in Manchuria (including Northeast China and Outer Manchuria) during the Ming dynasty, located on the banks of the Amur River, about 100 km from the sea ...

near the ruins of Tyr on the Siberian mainland, which continued operating until the mid-1430s. There is some evidence that the Ming eunuch Admiral Yishiha

Yishiha (; also Išiqa or Isiha; Jurchen: ) ( fl. 1409–1451) was a Jurchen eunuch of the Ming dynasty of China. He served the Ming emperors who commissioned several expeditions down the Songhua and Amur Rivers during the period of Ming rul ...

reached Sakhalin in 1413 during one of his expeditions to the lower Amur, and granted Ming titles to a local chieftain. Link is to partial text.

The Ming recruited headmen from Sakhalin for administrative posts such as commander ( zh, labels=no, p=zhǐhuīshǐ, c=指揮使), assistant commander ( zh, labels=no, p=zhǐhuī qiānshì, t=指揮僉事), and "official charged with subjugation" ( zh, labels=no, p=wèizhènfǔ, t=衛鎮撫). In 1431, one such assistant commander, Alige, brought marten

A marten is a weasel-like mammal in the genus ''Martes'' within the subfamily Guloninae, in the family Mustelidae. They have bushy tails and large paws with partially retractile claws. The fur varies from yellowish to dark brown, depending on ...

pelts as tribute to the Wuliehe post. In 1437, four other assistant commanders (Zhaluha, Sanchiha, Tuolingha, and Alingge) also presented tribute. According to the ''Ming Veritable Records

The ''Ming Veritable Records'' or ''Ming Shilu'' (), contains the imperial annals of the emperors of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). It is the single largest historical source of information on the dynasty. According to modern historians, it "p ...

'', these posts, like the position of headman, were hereditary and passed down the patrilineal line. During these tributary missions, the headmen would bring their sons, who later inherited their titles. In return for tribute, the Ming awarded them with silk uniforms.

Nivkh

Nivkh or Amuric or Gilyak may refer to:

* Nivkh people (''Nivkhs'') or Gilyak people (''Gilyaks'')

* Nivkh languages or Gilyak languages

* Gilyak class gunboat, ''Gilyak'' class gunboat, such as the Russian gunboat Korietz#Second gunboat, second R ...

women in Sakhalin married Han Chinese Ming officials when the Ming took tribute from Sakhalin and the Amur river region.

Qing tributary

The ManchuQing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

, which came to power in China in 1644, called Sakhalin "Kuyedao" () or "Kuye Fiyaka" ( ). The Manchus

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) an ...

called it "Sagaliyan ula angga hada" (Island at the Mouth of the Black River). The Qing first asserted influence over Sakhalin after the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk

The Treaty of Nerchinsk of 1689 was the first treaty between the Tsardom of Russia and the Qing dynasty of China after the defeat of Russia by Qing China at the Siege of Albazin in 1686. The Russians gave up the area north of the Amur River as ...

, which defined the Stanovoy Mountains

The Stanovoy Range (, ''Stanovoy khrebet''; ) is a mountain range located in the Sakha Republic and Amur Oblast, Far Eastern Federal District. It is also known as Sükebayatur and Sükhbaatar in Mongolian, or the Stanovoy Mountains or Outer K ...

as the border between the Qing and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

s. In the following year the Qing sent forces to the Amur

The Amur River () or Heilong River ( zh, s=黑龙江) is a perennial river in Northeast Asia, forming the natural border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China (historically the Outer Manchuria, Outer and Inner Manchuria). The Amur ...

estuary and demanded that the residents, including the Sakhalin Ainu, pay tribute. This was followed by several further visits to the island as part of the Qing effort to map the area. To enforce its influence, the Qing sent soldiers and mandarins across Sakhalin, reaching most parts of the island except the southern tip. The Qing imposed a fur-tribute system on the region's inhabitants.

The Qing dynasty established an office in Ningguta

Ning'an () is a city located approximately southwest of Mudanjiang, in the southeast of Heilongjiang province, China, bordering Jilin province to the south. It is located on the Mudanjiang River (formerly known as Hurka River), which flows north, ...

, situated midway along the Mudan River

The Mudan River (; IPA: ; ) is a river in Heilongjiang province in China. It is a right tributary of the Sunggari River.

Its modern Chinese name can be translated as the "Peony River". In the past it was also known as the Hurka or Hurha River ...

, to handle fur from the lower Amur and Sakhalin. Tribute was supposed to be brought to regional offices, but the lower Amur and Sakhalin were considered too remote, so the Qing sent officials directly to these regions every year to collect tribute and to present awards. By the 1730s, the Qing had appointed senior figures among the indigenous communities as "clan chief" (''hala-i-da'') or "village chief" (''gasan-da'' or ''mokun-da''). In 1732, 6 ''hala'', 18 ''gasban'', and 148 households were registered as tribute bearers in Sakhalin. Manchu officials gave tribute missions rice, salt, other necessities, and gifts during the duration of their mission. Tribute missions occurred during the summer months. During the reign of the Qianlong Emperor

The Qianlong Emperor (25 September 17117 February 1799), also known by his temple name Emperor Gaozong of Qing, personal name Hongli, was the fifth Emperor of China, emperor of the Qing dynasty and the fourth Qing emperor to rule over China pr ...

(r. 1735–95), a trade post existed at Delen, upstream of Kiji (Kizi) Lake, according to Rinzo Mamiya. There were 500–600 people at the market during Mamiya's stay there.

Local native Sakhalin chiefs had their daughters taken as wives by Manchu officials as sanctioned by the Qing dynasty when the Qing exercised jurisdiction in Sakhalin and took tribute from them.

Japanese exploration and colonization

In 1635,Matsumae Kinhiro

, was the second ''daimyō'' of Matsumae Domain in Ezo, Ezo-chi, (Hokkaidō), Japan, in the early Edo period. Holding this position from 1617 until his death in 1641, he was successor to Matsumae Yoshihiro and followed by Matsumae Ujihiro.

Name ...

, the second daimyō of Matsumae Domain

file:Matsumae Nagahiro.jpg, 270px, Matsumae Nagahiro, final daimyo of Matsumae Domain

The Matsumae Domain (松前藩), a prominent domain during the Edo period, was situated in Matsumae, Matsumae Island (Ishijima), which is currently known as M ...

in Hokkaidō, sent Satō Kamoemon and Kakizaki Kuroudo on an expedition to Sakhalin. One of the Matsumae explorers, Kodō Shōzaemon, stayed on the island in the winter of 1636 and sailed along the east coast to Taraika (now Poronaysk

Poronaysk (; ; Ainu: ''Sistukari'' or ''Sisi Tukari'') is a town and the administrative center of Poronaysky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia, located on the Poronay River north of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk. Population:

History

It was founded i ...

) in the spring of 1637.

In an early colonization attempt, a Japanese settlement was established at Ōtomari on Sakhalin's southern end in 1679. Cartographers of the Matsumae clan

The was a Japanese aristocratic family who were daimyo of Matsumae Domain, in present-day Matsumae, Hokkaidō, from the Azuchi–Momoyama period until the Meiji Restoration. They were given the domain as a march fief in 1590 by Toyotomi ...

drew a map of the island and called it "Kita-Ezo" (Northern Ezo, Ezo

is the Japanese term historically used to refer to the people and the lands to the northeast of the Japanese island of Honshu. This included the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido, which changed its name from "Ezo" to "Hokkaidō" in 1869, Nu ...

being the old Japanese name for the islands north of Honshu

, historically known as , is the largest of the four main islands of Japan. It lies between the Pacific Ocean (east) and the Sea of Japan (west). It is the list of islands by area, seventh-largest island in the world, and the list of islands by ...

).

In the 1780s, the influence of the Japanese Tokugawa Shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868.

The Tokugawa shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, ending the civil wars ...

on the Ainu of southern Sakhalin increased significantly. By the beginning of the 19th century, the Japanese economic zone extended midway up the east coast, to Taraika. With the exception of the Nayoro Ainu located on the west coast in close proximity to China, most Ainu stopped paying tribute to the Qing dynasty. The Matsumae clan

The was a Japanese aristocratic family who were daimyo of Matsumae Domain, in present-day Matsumae, Hokkaidō, from the Azuchi–Momoyama period until the Meiji Restoration. They were given the domain as a march fief in 1590 by Toyotomi ...

was nominally in charge of Sakhalin, but they neither protected nor governed the Ainu there. Instead they extorted the Ainu for Chinese silk, which they sold in Honshu

, historically known as , is the largest of the four main islands of Japan. It lies between the Pacific Ocean (east) and the Sea of Japan (west). It is the list of islands by area, seventh-largest island in the world, and the list of islands by ...

as Matsumae's special product. To obtain Chinese silk, the Ainu fell into debt, owing much fur to the Santan (Ulch people

The Ulch people, also known as Olcha, Olchi or Ulchi, (, obsolete ольчи; Ulch: , nani) are an Indigenous people of the Russian Far East, who speak a Tungusic language known as Ulch. Over 90% of Ulchis live in Ulchsky District of Khabar ...

), who lived near the Qing office. The Ainu also sold the silk uniforms (''mangpao'', ''bufu'', and ''chaofu'') given to them by the Qing, which made up the majority of what the Japanese knew as ''nishiki'' and ''jittoku''. As dynastic uniforms, the silk was of considerably higher quality than that traded at Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

, and enhanced Matsumae prestige as exotic items. Eventually the Tokugawa government, realizing that they could not depend on the Matsumae, took control of Sakhalin in 1807.

Japan proclaimed sovereignty over Sakhalin in 1807; in 1809, Mamiya Rinzō

was a Japanese Exploration, explorer of the late Edo period. He is best known for his exploration of Karafuto, now known as Sakhalin. He mapped areas of northeast Asia then unknown to Japanese.

Biography

Mamiya was born in 1775 in Tsukuba Dist ...

claimed that it was an island.

European exploration

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped Cape Patience and Cape Aniva on the island's east coast in 1643. The

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped Cape Patience and Cape Aniva on the island's east coast in 1643. The Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

captain, however, was unaware that it was an island, and 17th-century maps usually showed these points (and often Hokkaido as well) as part of the mainland. As part of a nationwide Sino-French cartographic program, Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

Jean-Baptiste Régis

Jean-Baptiste Régis (11 June 1663 or 29 January 1664 – 24 November 1738) was a French Jesuit missionary and geographer in imperial China.

Biography and works

Régis was born at Istres, in Provence. He was received into the Society of Jesus o ...

, Pierre Jartoux, and Xavier Ehrenbert Fridelli joined a Chinese team visiting the lower Amur

The Amur River () or Heilong River ( zh, s=黑龙江) is a perennial river in Northeast Asia, forming the natural border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China (historically the Outer Manchuria, Outer and Inner Manchuria). The Amur ...

(known to them under its Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic peoples, Tungusic East Asian people, East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized Ethnic minorities in China, ethnic minority in China and the people from wh ...

name, Sahaliyan Ula, "the Black River"), in 1709, and learned of the existence of the nearby offshore island from the Nanai natives of the lower Amur.

The Jesuits did not have a chance to visit the island, and the geographical information provided by the Nanai people and Manchus who had been to the island was insufficient to allow them to identify it as the land visited by de Vries in 1643. As a result, many 17th-century maps showed a rather strangely shaped Sakhalin, which included only the northern half of the island (with Cape Patience), while Cape Aniva, discovered by de Vries, and the "Black Cape" (Cape Crillon) were thought to form part of the mainland.

Only with the 1787 expedition of Jean-François de La Pérouse

Jean-François () is a French given name. Notable people bearing the given name include:

* Jean-François Carenco (born 1952), French politician

* Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832), French Egyptologist

* Jean-François Clervoy (born 1958), ...

did the island began to resemble something of its true shape on European maps. Though unable to pass through its northern "bottleneck" due to contrary winds, La Perouse charted most of the Strait of Tartary

Strait of Tartary or Gulf of Tartary (; ; ; ) is a strait in the Pacific Ocean dividing the Russian island of Sakhalin from mainland Asia (South-East Russia), connecting the Sea of Okhotsk ( Nevelskoy Strait) on the north with the Sea of Japan ...

, and islanders he encountered near today's Nevelskoy Strait told him that the island was called "Tchoka" (or at least that is how he recorded the name in French), and "Tchoka" appears on some maps thereafter.

19th century

Russo-Japanese rivalry

On the basis of its belief that it was an extension of Hokkaido, both geographically and culturally, Japan again proclaimed sovereignty over the whole island (as well as the

On the basis of its belief that it was an extension of Hokkaido, both geographically and culturally, Japan again proclaimed sovereignty over the whole island (as well as the Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands are a volcanic archipelago administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the Russian Far East. The islands stretch approximately northeast from Hokkaido in Japan to Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, separating the ...

chain) in 1845, in the face of competing claims from Russia. In 1849, however, the Russian navigator Gennady Nevelskoy

Gennady Ivanovich Nevelskoy (; in Drakino, Soligalichsky Uyezd, Kostroma Governorate – in St. Petersburg) was a Russian navigator and naval officer.

In 1829 he joined the Naval Cadet Corps and in 1846 was given the rank of ...

recorded the existence and navigability of the strait later given his name, and Russian settlers began establishing coal mines, administration facilities, schools, and churches on the island. In 1853–54, Nikolay Rudanovsky

Nikolay Vasilyevich Rudanovsky (, 1819 — 1882) was a Russian marine officer and explorer, notable for leading several expeditions in 1853–54 to survey and to map the southern part of Sakhalin. In particular, he became the first cartographer wh ...

surveyed and mapped the island.

In 1855, Russia and Japan signed the Treaty of Shimoda

The Treaty of Shimoda (下田条約, ''Shimoda Jouyaku'') (formally Treaty of Commerce and Navigation between Japan and Russia 日露和親条約, ''Nichi-Ro Washin Jouyaku'') of February 7, 1855, was the first treaty between the Russian Empire, a ...

, which declared that nationals of both countries could inhabit the island: Russians in the north, and Japanese in the south, without a clearly defined boundary between. Russia also agreed to dismantle its military base at Ootomari. Following the Second Opium War

The Second Opium War (), also known as the Second Anglo-Chinese War or ''Arrow'' War, was fought between the United Kingdom, France, Russia, and the United States against the Qing dynasty of China between 1856 and 1860. It was the second major ...

, Russia forced China to sign the Treaty of Aigun

The Treaty of Aigun was an 1858 treaty between the Russian Empire and Yishan, official of the Qing dynasty of China. It established much of the modern border between the Russian Far East and China by ceding much of Manchuria (the ancestral h ...

(1858) and the Convention of Peking

The Convention of Peking or First Convention of Peking is an agreement comprising three distinct unequal treaties concluded between the Qing dynasty of China and Great Britain, France, and the Russian Empire in 1860.

Background

On 18 October ...

(1860), under which China lost to Russia all claims to territories north of Heilongjiang

Heilongjiang is a province in northeast China. It is the northernmost and easternmost province of the country and contains China's northernmost point (in Mohe City along the Amur) and easternmost point (at the confluence of the Amur and Us ...

(Amur

The Amur River () or Heilong River ( zh, s=黑龙江) is a perennial river in Northeast Asia, forming the natural border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China (historically the Outer Manchuria, Outer and Inner Manchuria). The Amur ...

) and east of Ussuri

The Ussuri ( ; ) or Wusuli ( ) is a river that runs through Khabarovsk and Primorsky Krais, Russia and the southeast region of Northeast China in the province of Heilongjiang. It rises in the Sikhote-Alin mountain range, flowing north and formi ...

.

In 1857, the Russians established a penal colony, or ''katorga

Katorga (, ; from medieval and modern ; and Ottoman Turkish: , ) was a system of penal labor in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union (see Katorga labor in the Soviet Union).

Prisoners were sent to remote penal colonies in vast uninhabited a ...

'', on Sakhalin. The island remained under shared sovereignty until the signing of the 1875 Treaty of Saint Petersburg, in which Japan surrendered its claims in Sakhalin to Russia. In 1890, the author Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; ; 29 January 1860 – 15 July 1904) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer, widely considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his b ...

visited the penal colony on Sakhalin. He spent three months there interviewing thousands of convicts and settlers for a census and published his memoir ''Sakhalin Island

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, p=səxɐˈlʲin) is an island in Northeast Asia. Its north coast lies off the southeastern coast of Khabarovsk Krai in Russia, while its southern tip lies north of the Japanese island of Hokkaido. An islan ...

'' () of his journey.

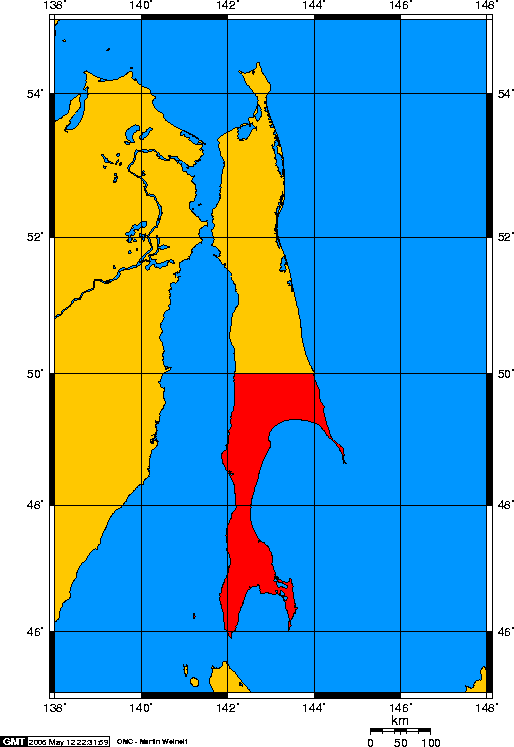

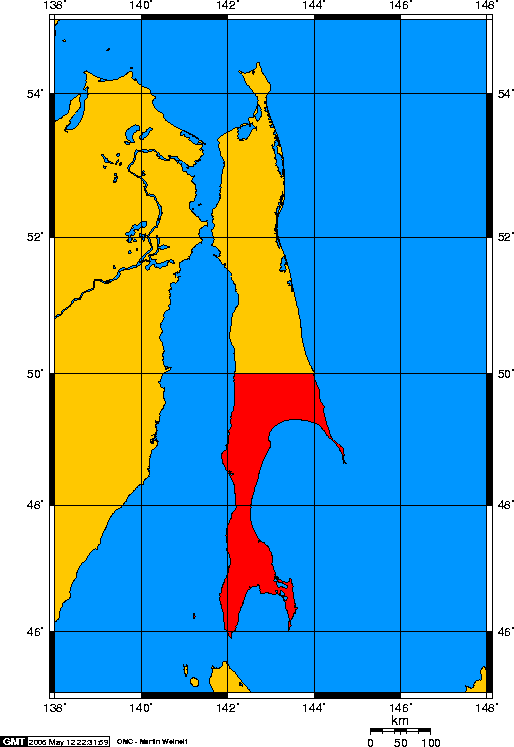

Division along 50th parallel

Japanese forces invaded and occupied Sakhalin in the closing stages of the

Japanese forces invaded and occupied Sakhalin in the closing stages of the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

. In accordance with the Treaty of Portsmouth

The Treaty of Portsmouth is a treaty that formally ended the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War. It was signed on September 5, 1905, after negotiations from August 6 to 30, at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, United States. U.S. P ...

of 1905, the southern part of the island below the 50th parallel north

Following are circles of latitude between the 45th parallel north and the 50th parallel north:

46th parallel north

The 46th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 46 degree (angle), degrees true north, north of the Earth, Earth's equat ...

reverted to Japan, while Russia retained the northern three-fifths.

South Sakhalin was administered by Japan as Karafuto Prefecture

, was established by the Empire of Japan in 1907 to govern the southern part of Sakhalin. This territory became part of the Empire of Japan in 1905 after the Russo-Japanese War, when the portion of Sakhalin south of 50°N was ceded by the R ...

(), with the capital at Toyohara (today's Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk

Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk (, , ) is a city and the administrative center of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. It is located on Sakhalin Island in the Russian Far East, north of Japan. Gas and oil extraction as well as processing are amongst the main industries on ...

). A large number of migrants were brought in from Korea.

The northern, Russian, half of the island formed Sakhalin Oblast

Sakhalin Oblast ( rus, Сахали́нская о́бласть, r=Sakhalinskaya oblastʹ, p=səxɐˈlʲinskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast) comprising the island of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in the Russian ...

, with the capital at Aleksandrovsk-Sakhalinsky. In response to the United States opening of Japan by Commodore Matthew C. Perry in 1853 and, later, the subsequent signing of the Convention of Kanagawa

The Convention of Kanagawa, also known as the or the , was a treaty signed between the United States and the Tokugawa Shogunate on March 31, 1854. Unequal treaty#Japan, Signed under threat of force, it effectively meant the end of Japan's 220-ye ...

on March 31, 1854, Tsar Nicholas I

Nicholas I, group=pron (Russian language, Russian: Николай I Павлович; – ) was Emperor of Russia, List of rulers of Partitioned Poland#Kings of the Kingdom of Poland, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 18 ...

, who was personally involved in the "Sakhalin issue", in April 1853 ordered the Russian-American Company

The Russian-American Company Under the High Patronage of His Imperial Majesty was a state-sponsored chartered company formed largely on the basis of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, United American Company. Emperor Paul I of Russia chartered the c ...

(RAC) to immediately occupy the Sakhalin Island and begin colonization by constructing two redoubts armed with cannons on the western and southern coasts of the island. On September 20, 1853, the RAC ship " Emperor Nikolai I" () under the command of skipper Martin Fyodorovich Klinkowström () and under the general guidance of Captain Nevelskoy arrived at Tomari-Aniva on Aniva Bay

Aniva Bay (Russian: Залив Анива (''Zaliv Aniva''), Japanese: 亜庭湾, Aniwa Bay, or Aniva Gulf) is located at the southern end of Sakhalin Island, Russia, north of the island of Hokkaidō, Japan. The largest city on the bay is Korsako ...

, not far from the main Japanese settlement on the island, and put ashore men and materials to form a military outpost.

At the oldest stettlement on Sakhlin Island, Sakhalin Oblast had a Czarist era penal colony named Due () on Cape Douai which had the 1853 established Makaryevka () coal mine, which was supported by both the Muravyovsky post (), now known as Korsakov (), at Aniva Bay (), which was named after Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky

Count Nikolay Nikolayevich Muravyov-Amursky (also spelled as Nikolai Nikolaevich Muraviev-Amurskiy; ; – ) was a Russian general, statesman and diplomat, who played a major role in the expansion of the Russian Empire into the Amur River basin a ...

who had sponsored the expedition

''The Expedition'' is the first live album by American power metal band Kamelot, released in October 2000 through Noise Records. The last three tracks are rare studio recordings: "We Three Kings" (instrumental) and "One Day" are additional mat ...

commanded by Gennady Nevelskoy

Gennady Ivanovich Nevelskoy (; in Drakino, Soligalichsky Uyezd, Kostroma Governorate – in St. Petersburg) was a Russian navigator and naval officer.

In 1829 he joined the Naval Cadet Corps and in 1846 was given the rank of ...

that explored the coast of Sakhalin Island from 1849 to 1853, and the Russian-American Company

The Russian-American Company Under the High Patronage of His Imperial Majesty was a state-sponsored chartered company formed largely on the basis of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, United American Company. Emperor Paul I of Russia chartered the c ...

, and hosted its first prisoner beginning in 1876. On April 18, 1869, Tsar Alexander II

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland fro ...

approved the "Regulations of the Committee on the Arrangement of Hard Labor" () which formed the legal basis for Sakhalin Island to be a penal colony.

In 1920, during the Siberian Intervention, Japan again occupied the northern part of the island, returning it to the Soviet Union in 1925 after the Treaty of Beijing

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by international law. A treaty may also be known as an international agreement, protocol, covenant, conventio ...

was signed on January 20, 1925. However, Japan formed the state owned firm North Sakhalin Oil () which extracted oil from the OKHA Oil Field () near Okha on North Sakhalin from 1926 to 1944.

Whaling

Between 1848 and 1902,American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

whaleship

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

s hunted whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully Aquatic animal, aquatic placental mammal, placental marine mammals. As an informal and Colloquialism, colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea ...

s off Sakhalin. They cruised for bowhead and gray whale

The gray whale (''Eschrichtius robustus''), also known as the grey whale,Britannica Micro.: v. IV, p. 693. is a baleen whale that migrates between feeding and breeding grounds yearly. It reaches a length of , a weight of up to and lives between ...

s to the north and right whale

Right whales are three species of large baleen whales of the genus ''Eubalaena'': the North Atlantic right whale (''E. glacialis''), the North Pacific right whale (''E. japonica'') and the southern right whale (''E. australis''). They are class ...

s to the east and south.

On June 7, 1855, the ship ''Jefferson'' (396 tons), of New London, was wrecked on Cape Levenshtern

Cape Levenshtern (Russian: ''Mys Levenshterna'') is a cape on the northeast coast of Sakhalin Island in the western Sea of Okhotsk. It is rounded and rugged. It lies 37 km (about 23 mi) to the south-southeast of Cape Elizabeth, the northern point ...

, on the northeastern side of the island, during a fog. All hands were saved as well as 300 barrels of whale oil

Whale oil is oil obtained from the blubber of whales. Oil from the bowhead whale was sometimes known as train-oil, which comes from the Dutch word ''traan'' ("tear drop").

Sperm oil, a special kind of oil used in the cavities of sperm whales, ...

.

Second World War

In August 1945, after repudiating theSoviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact

The , also known as the , was a non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan signed on April 13, 1941, two years after the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese Border War. The agreement meant that for most of World War II, ...

, the Soviet Union invaded southern Sakhalin, an action planned secretly at the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (), held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. The three sta ...

. The Soviet attack started on August 11, 1945, a few days before the surrender of Japan. The Soviet 56th Rifle Corps, part of the 16th Army, consisting of the 79th Rifle Division, the 2nd Rifle Brigade, the 5th Rifle Brigade and the 214 Armored Brigade, attacked the Japanese 88th Infantry Division. Although the Soviet Red Army outnumbered the Japanese by three to one, they advanced only slowly due to strong Japanese resistance. It was not until the 113th Rifle Brigade and the 365th Independent Naval Infantry Rifle Battalion from Sovetskaya Gavan landed on Tōro, a seashore village of western Karafuto, on August 16 that the Soviets broke the Japanese defense line. Japanese resistance grew weaker after this landing. Actual fighting continued until August 21. From August 22 to August 23, most remaining Japanese units agreed to a ceasefire. The Soviets completed the conquest of Karafuto on August 25, 1945, by occupying the capital of Toyohara.

Of the approximately 400,000 people – mostly Japanese and Korean – who lived on South Sakhalin in 1944, about 100,000 were evacuated to Japan during the last days of the war. The remaining 300,000 stayed behind, some for several more years.

While the vast majority of Sakhalin Japanese and Koreans were gradually repatriated between 1946 and 1950, tens of thousands of Sakhalin Koreans

Sakhalin Koreans (; ) are Russian citizens and residents of Korean descent living on Sakhalin Island, who can trace their roots to the immigrants from the Gyeongsang Province, Gyeongsang and Jeolla Province, Jeolla provinces of Korea during th ...

(and a number of their Japanese spouses) remained in the Soviet Union.

No final peace treaty has been signed and the status of four neighboring islands remains disputed

Controversy (, ) is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usually concerning a matter of conflicting opinion or point of view. The word was coined from the Latin ''controversia'', as a composite of ''controversus'' – "turned in an oppo ...

. Japan renounced its claims of sovereignty over southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in the Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war, military occupation and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and inclu ...

(1951), but maintains that the four offshore islands of Hokkaido

is the list of islands of Japan by area, second-largest island of Japan and comprises the largest and northernmost prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own list of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō fr ...

currently administered by Russia were not subject to this renunciation. Japan granted mutual exchange visas for Japanese and Ainu families divided by the change in status. Recently, economic and political cooperation has gradually improved between the two nations despite disagreements.

Recent history

On 1 September 1983,

On 1 September 1983, Korean Air Flight 007

Korean Air Lines Flight 007 (KE007/KAL007)In aviation, two types of airline designators are used. The flight number KAL 007, with the ICAO code for Korean Air Lines, was used by air traffic control. In ticketing, however, IATA codes are us ...

, a South Korean civilian airliner, flew over Sakhalin and was shot down by the Soviet Union, just west of Sakhalin Island, near the smaller Moneron Island

Moneron Island, (, , , Ainu: ) is a small island off Sakhalin Island. It is a part of the Russian Federation.

Description

Moneron has an area of about and a highest point of . It is approximately long (N/S axis) by wide, and is located ...

. The Soviet Union claimed it was a spy plane; however, commanders on the ground realized it was a commercial aircraft. All 269 passengers and crew died, including a U.S. Congressman, Larry McDonald

Lawrence Patton McDonald (April 1, 1935 – September 1, 1983) was an American physician, politician and a member of the United States House of Representatives, representing Georgia's 7th congressional district as a Democrat from 1975 until ...

.

On 27 May 1995, the 7.0 Neftegorsk earthquake shook the former Russian settlement of Neftegorsk with a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (''Violent''). Total damage was $64.1–300 million, with 1,989 deaths and 750 injured. The settlement was not rebuilt.

Geography

Sakhalin is separated from the mainland by the narrow and shallowStrait of Tartary

Strait of Tartary or Gulf of Tartary (; ; ; ) is a strait in the Pacific Ocean dividing the Russian island of Sakhalin from mainland Asia (South-East Russia), connecting the Sea of Okhotsk ( Nevelskoy Strait) on the north with the Sea of Japan ...

, which often freezes in winter in its narrower part, and from Hokkaido

is the list of islands of Japan by area, second-largest island of Japan and comprises the largest and northernmost prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own list of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō fr ...

, Japan, by the Soya Strait or La Pérouse Strait

La Pérouse Strait (), or , is a strait dividing the southern part of the Russian island of Sakhalin from the northern part of the Japanese island of Hokkaidō, and connecting the Sea of Japan on the west with the Sea of Okhotsk on the east.

...

. Sakhalin is the largest island in Russia, being long, and wide, with an area of . It lies at similar latitudes to England, Wales and Ireland.

Its orography

Orography is the study of the topographic relief of mountains, and can more broadly include hills, and any part of a region's elevated terrain. Orography (also known as ''oreography'', ''orology,'' or ''oreology'') falls within the broader disci ...

and geological structure are imperfectly known. One theory is that Sakhalin arose from the Sakhalin Island Arc. Nearly two-thirds of Sakhalin is mountainous. Two parallel ranges of mountains traverse it from north to south, reaching . The Western Sakhalin Mountains peak in Mount Ichara, , while the Eastern Sakhalin Mountains's highest peak, Mount Lopatin , is also the island's highest mountain. Tym-Poronaiskaya Valley separates the two ranges. Susuanaisky and Tonino-Anivsky ranges traverse the island in the south, while the swampy Northern-Sakhalin plain occupies most of its north.Ivlev, A. M. Soils of Sakhalin. New Delhi: Indian National Scientific Documentation Centre, 1974. Pages 9–28.

Crystalline rocks crop out at several capes; Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

s, containing an abundant and specific fauna of gigantic ammonite

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

s, occur at Dui on the west coast; and Tertiary

Tertiary (from Latin, meaning 'third' or 'of the third degree/order..') may refer to:

* Tertiary period, an obsolete geologic period spanning from 66 to 2.6 million years ago

* Tertiary (chemistry), a term describing bonding patterns in organic ch ...

conglomerates, sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

s, marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, Clay minerals, clays, and silt. When Lithification, hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

M ...

s, and clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

s, folded by subsequent upheavals, are found in many parts of the island. The clays, which contain layers of good coal and abundant fossilized vegetation, show that during the Miocene period, Sakhalin formed part of a continent which comprised north Asia, Alaska, and Japan, and enjoyed a comparatively warm climate. The Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, ...

s was probably broader than it is now.

Main rivers: The Tym, long and navigable by rafts and light boats for , flows north and northeast with numerous rapids and shallows, and enters the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk; Historically also known as , or as ; ) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands on the southeast, Japan's island of Hokkaido on the sou ...

.Тымь– an article in the ''

Great Soviet Encyclopedia

The ''Great Soviet Encyclopedia'' (GSE; , ''BSE'') is one of the largest Russian-language encyclopedias, published in the Soviet Union from 1926 to 1990. After 2002, the encyclopedia's data was partially included into the later ''Great Russian Enc ...

''. (In Russian, retrieved 21 June 2020.) The Poronay

The Poronay (, ) is the longest river on the island of Sakhalin in Russia. It flows in a southerly direction through Tym, Smirnykhovsky and Poronaysky Districts.

Geography

The river begins on Mt. Nevel in the East Sakhalin Mountains, flows sout ...

flows south-southeast to the Gulf of Patience

Gulf of Patience is a large body of water off the southeastern coast of Sakhalin, Russia.

Geography

The Gulf of Patience is located in the southern Sea of Okhotsk, between the main body of Sakhalin Island in the west and Cape Patience in the e ...

or Shichiro Bay, on the southeastern coast. Three other small streams enter the wide semicircular Aniva Bay

Aniva Bay (Russian: Залив Анива (''Zaliv Aniva''), Japanese: 亜庭湾, Aniwa Bay, or Aniva Gulf) is located at the southern end of Sakhalin Island, Russia, north of the island of Hokkaidō, Japan. The largest city on the bay is Korsako ...

or Higashifushimi Bay at the southern extremity of the island.

The northernmost point of Sakhalin is Cape Elizabeth

Cape Elizabeth is a town in Cumberland County, Maine, United States. The town is part of the Portland– South Portland–Biddeford, Maine, metropolitan statistical area. As of the 2020 census, Cape Elizabeth had a population of 9,535 ...

on the Schmidt Peninsula, while Cape Crillon

Cape Crillon (, "Nishinotoro-misaki" (Cape Nishinotoro in Japanese), ) is the southernmost point of Sakhalin. The cape was named by Frenchman Jean-François de La Pérouse, who was the first European to discover it. Cape Sōya, in Japan, is loca ...

is the southernmost point of the island. The Khalpili Islands are off Cape Khalpili.

Sakhalin has two smaller islands associated with it, Moneron Island

Moneron Island, (, , , Ainu: ) is a small island off Sakhalin Island. It is a part of the Russian Federation.

Description

Moneron has an area of about and a highest point of . It is approximately long (N/S axis) by wide, and is located ...

and Ush Island

Ush Island (Остров Уш; Ostrov Ush) is an island in the northern coast of Sakhalin. Ush Island is located between a shallow bay and the Sea of Okhotsk, at the mouth of the Sakhalin Gulf.

Ush Island stretches roughly from east to west. I ...

. Moneron, the only land mass in the Tatar strait, long and wide, is about west from the nearest coast of Sakhalin and from the port city of Nevelsk. Ush Island is an island off of the northern coast of Sakhalin.

Demographics

According to the 1897 census, Sakhalin had a population of 28,113, of which 56.2% were Russians, 8.4%

According to the 1897 census, Sakhalin had a population of 28,113, of which 56.2% were Russians, 8.4% Ukrainians

Ukrainians (, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the List of contemporary eth ...

, 7.0% Nivkh

Nivkh or Amuric or Gilyak may refer to:

* Nivkh people (''Nivkhs'') or Gilyak people (''Gilyaks'')

* Nivkh languages or Gilyak languages

* Gilyak class gunboat, ''Gilyak'' class gunboat, such as the Russian gunboat Korietz#Second gunboat, second R ...

, 5.8% Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

, 5.4% Tatars

Tatars ( )Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

, 5.1% Ainu, 2.82% in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

Oroks

Oroks (''Ороки'' in Russian; self-designation: ''Ulta, Ulcha''), sometimes called Uilta, are a people in the Sakhalin Oblast (mainly the eastern part of the island) in Russia. The Orok language belongs to the Southern group of the Tungus ...

, 0.95% Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

, 0.81% Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

, with the non-indigenous people living mainly from agriculture, or being convicts or exiles. The majority of Nivkh, Ainu and Japanese lived from fishing or hunting, whereas the Oroks lived mainly by livestock (reindeer

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, taiga, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only re ...

) breeding. The Ainu, Japanese and Koreans

Koreans are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Korean Peninsula. The majority of Koreans live in the two Korean sovereign states of North and South Korea, which are collectively referred to as Korea. As of 2021, an estimated 7.3 m ...

lived almost exclusively in the southern part of the island. Since 1925, many Poles fled Soviet Russian persecution in the north to the then Japanese south.

The 400,000 Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

inhabitants of Sakhalin (including the Japanized indigenous Ainu) who had not already been evacuated during the war were deported following the invasion of the southern portion of the island by the Soviet Union in 1945 at the end of World War II.

In 2010, the island's population was recorded at 497,973, 83% of whom were ethnic Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

, followed by about 30,000 Koreans

Koreans are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Korean Peninsula. The majority of Koreans live in the two Korean sovereign states of North and South Korea, which are collectively referred to as Korea. As of 2021, an estimated 7.3 m ...

(5.5%). Smaller minorities were the Ainu, Ukrainians

Ukrainians (, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the List of contemporary eth ...

, Tatars

Tatars ( )Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

, in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

Sakhas

The Yakuts or Sakha (, ; , ) are a Turkic ethnic group native to North Siberia, primarily the Republic of Sakha in the Russian Federation. They also inhabit some districts of the Krasnoyarsk Krai. They speak Yakut, which belongs to the Sib ...

and Evenks

The Evenki, also known as the Evenks and formerly as the Tungus, are a Tungusic peoples, Tungusic people of North Asia. In Russia, the Evenki are recognised as one of the Indigenous peoples of the Russian North, indigenous peoples of the Russi ...

. The native inhabitants currently consist of some 2,000 Nivkhs

The Nivkh, or Gilyak (also Nivkhs or Nivkhi, or Gilyaks; ethnonym: Нивхгу, ''Nʼivxgu'' (Amur) or Ниғвңгун, ''Nʼiɣvŋgun'' (E. Sakhalin) "the people"), are an indigenous ethnic group inhabiting the northern half of Sakhalin Islan ...

and 750 Oroks

Oroks (''Ороки'' in Russian; self-designation: ''Ulta, Ulcha''), sometimes called Uilta, are a people in the Sakhalin Oblast (mainly the eastern part of the island) in Russia. The Orok language belongs to the Southern group of the Tungus ...

. The Nivkhs in the north support themselves by fishing and hunting.

The administrative center of the oblast, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk

Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk (, , ) is a city and the administrative center of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. It is located on Sakhalin Island in the Russian Far East, north of Japan. Gas and oil extraction as well as processing are amongst the main industries on ...

, a city of about 175,000, has a large Korean minority, typically referred to as Sakhalin Koreans

Sakhalin Koreans (; ) are Russian citizens and residents of Korean descent living on Sakhalin Island, who can trace their roots to the immigrants from the Gyeongsang Province, Gyeongsang and Jeolla Province, Jeolla provinces of Korea during th ...

, who were forcibly brought by the Japanese during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

to work in the coal mines. Most of the population lives in the southern half of the island, centered mainly around Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk and two ports, Kholmsk

Kholmsk (), known until 1946 as Maoka (), is a port town and the administrative center of Kholmsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. It is located on the southwest coast of the Sakhalin Island, on coast of the gulf of Nevelsky in the Strait o ...

and Korsakov (population about 40,000 each). In 2008 there were 6,416 births and 7,572 deaths.

Climate

The Sea of Okhotsk ensures that Sakhalin has a cold and humid climate, ranging fromhumid continental

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation, dew, or fog to be present.

Humidity depe ...

(Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (1951–2014), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author ...

''Dfb'') in the south to subarctic

The subarctic zone is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic, north of hemiboreal regions and covering much of Alaska, Canada, Iceland, the north of Fennoscandia, Northwestern Russia, Siberia, and the Cair ...

(''Dfc'') in the centre and north. The maritime influence makes summers much cooler than in similar-latitude inland cities such as Harbin

Harbin, ; zh, , s=哈尔滨, t=哈爾濱, p=Hā'ěrbīn; IPA: . is the capital of Heilongjiang, China. It is the largest city of Heilongjiang, as well as being the city with the second-largest urban area, urban population (after Shenyang, Lia ...

or Irkutsk

Irkutsk ( ; rus, Иркутск, p=ɪrˈkutsk; Buryat language, Buryat and , ''Erhüü'', ) is the largest city and administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. With a population of 587,891 Irkutsk is the List of cities and towns in Russ ...

, but makes the winters much snowier and a few degrees warmer than in interior East Asian cities at the same latitude. Summers are foggy with little sunshine.

Precipitation is heavy, owing to the strong onshore winds in summer and the high frequency of North Pacific storms affecting the island in the autumn. It ranges from around on the northwest coast to over in southern mountainous regions. In contrast to interior east Asia with its pronounced summer maximum, onshore winds ensure Sakhalin has year-round precipitation with a peak in the autumn.

Flora and fauna

The whole of the island is covered with dense

The whole of the island is covered with dense forest

A forest is an ecosystem characterized by a dense ecological community, community of trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, ...

s, mostly conifer

Conifers () are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a sin ...

ous. The Yezo (or Yeddo) spruce (''Picea jezoensis''), the Sakhalin fir (''Abies sachalinensis''), the Dahurian larch

''Larix gmelinii'', the Dahurian larch or East Siberian larch, is a species of larch native to eastern Siberia and adjacent northeastern Mongolia, northeastern China (Heilongjiang), South Korea and North Korea.

Description

''Larix gmelinii'' ...

(''Larix gmelinii''), and ''Picea glehnii

''Picea glehnii'', the Sakhalin spruce or Glehn's spruce, is a species of conifer in the family Pinaceae. It was named after a Russian botanist, taxonomist, Sakhalin and Amur river regions explorer, geographer and hydrographer Peter von Glehn (1 ...

'' are the chief trees; on the upper parts of the mountains are the Siberian dwarf pine

''Pinus pumila'', commonly known as the Siberian dwarf pine, dwarf Siberian pine, dwarf stone pine, Japanese stone pine, or creeping pine, is a tree in the family Pinaceae native plant, native to northeastern Asia and the Japan, Japanese isles. ...

(''Pinus pumila'') and the Kurile bamboo (''Sasa kurilensis''). Birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech- oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 3 ...

es, both Siberian silver birch (''Betula platyphylla

''Betula platyphylla'', the Asian white birch or Japanese white birch, is a tree species in the family Betulaceae. It can be found in subarctic and temperate Asia in Japan, China, Korea, Mongolia, the Russian Far East, and Siberia

Siber ...

'') and Erman's birch

''Betula ermanii'', or Erman's birch, is a species of birch tree belonging to the family Betulaceae. It is an extremely variable species and can be found in Northeast China, Korea, Japan, and Russian Far East (Kuril Islands, Sakhalin, Kamchatka ...

(''B. ermanii''), poplar, elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus ''Ulmus'' in the family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical- montane regions of North America and Eurasia, ...

(''Ulmus laciniata

''Ulmus laciniata'' (Trautv.) Mayr, known variously as the Manchurian, cut-leaf, or lobed elm, is a deciduous tree native to the humid ravine forests of Japan, Korea, northern China, eastern Siberia and Sakhalin, growing alongside ''Cercidiphyllu ...

''), bird cherry

Bird cherry is a common name for the Eurasian plant ''Prunus padus''.

Bird cherry may also refer to:

* Prunus subg. Padus, ''Prunus'' subg. ''Padus'', a group of species closely related to ''Prunus padus''

* ''Prunus avium'', the cultivated cherry ...

(''Prunus padus''), Japanese yew (''Taxus cuspidata''), and several willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, of the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 350 species (plus numerous hybrids) of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions.

Most species are known ...

s are mixed with the conifers; while farther south the maple

''Acer'' is a genus of trees and shrubs commonly known as maples. The genus is placed in the soapberry family Sapindaceae.Stevens, P. F. (2001 onwards). Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Version 9, June 2008 nd more or less continuously updated si ...

, rowan

The rowans ( or ) or mountain-ashes are shrubs or trees in the genus ''Sorbus'' of the rose family, Rosaceae. They are native throughout the cool temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, with the highest species diversity in the Himalaya ...

and oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

, as also the Japanese '' Kalopanax septemlobus'', the Amur cork tree

''Phellodendron amurense'' is a species of tree in the family Rutaceae, commonly called the Amur cork tree. It is a major source of '' huáng bò'' ( or 黄 檗), one of the 50 fundamental herbs used in traditional Chinese medicine. The Ainu peo ...

(''Phellodendron amurense''), the spindle

Spindle may refer to:

Textiles and manufacturing

* Spindle (textiles), a straight spike to spin fibers into yarn

* Spindle (tool), a rotating axis of a machine tool

Biology

* Common spindle and other species of shrubs and trees in genus ''Euonym ...

('' Euonymus macropterus'') and the vine (''Vitis thunbergii

''Vitis ficifolia'' is a species of liana in the grape family native to the Asian temperate climate zone. It is found in mainland China (Hebei, Henan, Jiangsu, Shaanxi, Shandong and Shanxi provinces), Japan (prefectures of Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyu ...

'') make their appearance. The underwoods abound in berry-bearing plants (e.g. cloudberry

''Rubus chamaemorus'' is a species of flowering plant in the rose family. Its English common names include cloudberry, Nordic berry, bakeapple (in Newfoundland and Labrador), knotberry and knoutberry (in England), aqpik or low-bush salmonberry ...

, cranberry

Cranberries are a group of evergreen dwarf shrubs or trailing vines in the subgenus ''Oxycoccus'' of the genus ''Vaccinium''. Cranberries are low, creeping shrubs or vines up to long and in height; they have slender stems that are not th ...

, crowberry

''Empetrum nigrum'', crowberry, black crowberry, mossberry, or, in western Alaska, Labrador, etc., blackberry, is a flowering plant species in the heather family Ericaceae with a near circumboreal distribution in the Northern Hemisphere.

Desc ...

, red whortleberry

''Vaccinium vitis-idaea'' is a small evergreen shrub in the heath family, Ericaceae. It is known colloquially as the lingonberry, partridgeberry, foxberry, mountain cranberry, or cowberry. It is native to boreal forest and Arctic tundra through ...

), red-berried elder (''Sambucus racemosa

''Sambucus racemosa'' is a species of elder known by the common names red-berried elder and red elderberry. It is native across much of the Northern Hemisphere.

Description

''Sambucus racemosa'' is medium-sized shrub growing (rarely ) tall. Th ...

''), wild raspberry

The raspberry is the edible fruit of several plant species in the genus ''Rubus'' of the Rosaceae, rose family, most of which are in the subgenus ''Rubus#Modern classification, Idaeobatus''. The name also applies to these plants themselves. Ras ...

, and Spiraea