Royal Necropolis Of Byblos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The royal necropolis of Byblos is a group of nine

Byblos (Jbeil) is one of the oldest continuously populated cities in the world. It has taken many names over the ages; it appears as Kebny in 4th-dynasty

Byblos (Jbeil) is one of the oldest continuously populated cities in the world. It has taken many names over the ages; it appears as Kebny in 4th-dynasty

Ancient texts and manuscripts hinted at the location of Gebal, which was lost to history until its rediscovery in the mid-19th century. In 1860, French biblical scholar and orientalist

Ancient texts and manuscripts hinted at the location of Gebal, which was lost to history until its rediscovery in the mid-19th century. In 1860, French biblical scholar and orientalist

During the period of the

During the period of the

On 16 February 1922, heavy rain triggered a landslide on the seaside cliff of Jbeil which exposed an underground man-made cavity. The next day the administrative advisor of

On 16 February 1922, heavy rain triggered a landslide on the seaside cliff of Jbeil which exposed an underground man-made cavity. The next day the administrative advisor of

The sarcophagus was placed in a north–south orientation. A rock-cut opening is present at a height of on the north wall of Tomb I's chamber, directly facing the sarcophagus. The opening leads to a high and to wide corridor that joins the south side of the shaft of Tomb II. The same corridor is joined by a passageway emerging from the northwestern angle of Tomb I's shaft. Midway between Tomb I and the shaft of Tomb II the S-shaped corridor opens, to its north side, onto a small nondescript hole giving access to a roughly cut round cavity housing an archaic tomb.

A coarsely built wall separated the chamber of Tomb I from its shaft. The shaft was filled to its brim with stones and mortar. The same material was used to build a platform around the shaft, on top of which were laid the foundations of a ''

The sarcophagus was placed in a north–south orientation. A rock-cut opening is present at a height of on the north wall of Tomb I's chamber, directly facing the sarcophagus. The opening leads to a high and to wide corridor that joins the south side of the shaft of Tomb II. The same corridor is joined by a passageway emerging from the northwestern angle of Tomb I's shaft. Midway between Tomb I and the shaft of Tomb II the S-shaped corridor opens, to its north side, onto a small nondescript hole giving access to a roughly cut round cavity housing an archaic tomb.

A coarsely built wall separated the chamber of Tomb I from its shaft. The shaft was filled to its brim with stones and mortar. The same material was used to build a platform around the shaft, on top of which were laid the foundations of a ''

File:BAH 11 Montet, Pierre - Byblos et l'Egypte Quatre campagnes de fouilles à Gebeil 1921-1922-1923-1924 Atlas (1929) LR 0117.jpg, alt=Sketch showing two burial shaft burial structures, Context plan of tombs I and II

File:BAH 11 Montet, Pierre - Byblos et l'Egypte Quatre campagnes de fouilles à Gebeil 1921-1922-1923-1924 Atlas (1929) LR 0118.jpg, alt=A group of four sketches showing burial wells and tomb structures,

The sarcophagus of Tomb I measures , and is tall. The side walls of the sarcophagus are thick; the bottom of the sarcophagus body is thick. The rim of the Sarcophagus I lid is beveled; it is cut from below so as to enter a few centimeters into the sarcophagus body. The back of the lid is rounded and striated with lengthwise irregularly sized

The sarcophagus of Tomb I measures , and is tall. The side walls of the sarcophagus are thick; the bottom of the sarcophagus body is thick. The rim of the Sarcophagus I lid is beveled; it is cut from below so as to enter a few centimeters into the sarcophagus body. The back of the lid is rounded and striated with lengthwise irregularly sized

The main scene on the front of the sarcophagus depicts the king on a throne holding a wilted lotus flower. A table full of offerings stands in front of the throne, followed by a procession of seven male figures. Two scenes of a funerary procession of four mourning women occupy the two small sides of the sarcophagus. Two of the women on each of the sides bare their chests, and the two others are depicted hitting their heads with their hands. The scene on the back side of the sarcophagus shows a procession of men and women bearing offerings.

The lid of the sarcophagus is slightly

The main scene on the front of the sarcophagus depicts the king on a throne holding a wilted lotus flower. A table full of offerings stands in front of the throne, followed by a procession of seven male figures. Two scenes of a funerary procession of four mourning women occupy the two small sides of the sarcophagus. Two of the women on each of the sides bare their chests, and the two others are depicted hitting their heads with their hands. The scene on the back side of the sarcophagus shows a procession of men and women bearing offerings.

The lid of the sarcophagus is slightly

More than 260 items were recovered from the royal necropolis of Byblos.

More than 260 items were recovered from the royal necropolis of Byblos.

] The names of some of the sarcophagi occupants are known from archeological finds. Tombs I belonged to King Abishemu (also Romanization, romanized as "Abishemou" and "Abichemou") who received gifts from Pharaoh Amenemhat III, and Tomb II belonged to his son Ip-Shemu-Abi (also romanized as "Ypchemouabi") who received similar gifts from the son of Amenemhat IV. These gifts suggest that the reigns of Abishemu and Ip-Shemu-Abi were contemporaneous with those of late Twelfth Dynasty rulers. The names of both Gebalite kings were inscribed on the ''khopesh'' staff found in Tomb II. A passageway linked the chamber of Tomb I to the shaft of Tomb II. Montet posited that Ip-Shemu-Abi had this tunnel dug to remain in constant communication with his father.

Montet proposed that Tomb IV was made for a vassal king of Egyptian origin, whom he believes was appointed by Egypt, thus interrupting the Gebalite dynastic suite. This theory was put forward based on Montet's discovery of an Egyptian scarab inscribed with the Egyptian name Medjed-Tebit-Atef.

The sarcophagus of Tomb V belongs to Ahiram; it stands apart from the other sarcophagi for its rich decoration and reliefs. Ahiram's sarcophagus was found in the chamber of Tomb V with two other plain sarcophagi. The lid of the sarcophagus features the effigies of the deceased, and that of his successor. The sarcophagus' funerary inscription identifies the names of the deceased king, and his son and successor Pilsibaal.

Earthenware fragments discovered in Tomb IX bore the name of Abishemu in Egyptian hieroglyphs. This led scholars to attribute the sarcophagus to Abishemu, the second of that name, who could be the grandson of the elder. This assumption is based on the Phoenician custom of naming a prince after his grandfather.

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

underground shaft and chamber tomb

A shaft and chamber tomb is a type of chamber tomb used by some ancient peoples for burial of the dead. They consist of a shaft dug into the outcrops of rock with a square or round chamber excavated at the bottom where the dead were placed. The ...

s housing the sarcophagi

A sarcophagus (: sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a coffin, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek σάρξ ' meaning "flesh", and φ� ...

of several kings of the city. Byblos

Byblos ( ; ), also known as Jebeil, Jbeil or Jubayl (, Lebanese Arabic, locally ), is an ancient city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. The area is believed to have been first settled between 8800 and 7000BC and continuously inhabited ...

(modern Jbeil) is a coastal city in Lebanon, and one of the oldest continuously populated cities in the world. The city established major trade links with Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

during the Bronze Age, resulting in a heavy Egyptian influence on local culture and funerary practices. The location of ancient Byblos was lost to history, but was rediscovered in the late 19th century by the French biblical scholar and Orientalist Ernest Renan

Joseph Ernest Renan (; ; 27 February 18232 October 1892) was a French Orientalist and Semitic scholar, writing on Semitic languages and civilizations, historian of religion, philologist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and critic. He wrote wo ...

. The remains of the ancient city sat on top of a hill in the immediate vicinity of the modern city of Jbeil. Exploratory trenches and minor digs were undertaken by the French mandate

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (; , also referred to as the Levant States; 1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate founded in the aftermath of the First World War and the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, concerning the territori ...

authorities, during which reliefs inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined Ideogram, ideographic, logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 1,000 distinct char ...

were excavated. The discovery stirred the interest of western scholars, leading to systematic surveys of the site.

On 16 February 1922, heavy rains triggered a landslide in the seaside cliff of Jbeil, exposing an underground tomb containing a massive stone sarcophagus. The grave was explored by the French epigrapher

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

and archeologist Charles Virolleaud

Jean Charles Gabriel Virolleaud (2 July 1879 – 17 December 1968) was a French archaeologist, one of the excavators of Ugarit.

Virolleaud was the author of ''La légende du Christ'' (1908) and was an advocate of the Christ myth theory. He also ...

. Intensive digs were carried out around the site of the tomb by the French Egyptologist

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , ''-logia''; ) is the scientific study of ancient Egypt. The topics studied include ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end ...

Pierre Montet

Jean Pierre Marie Montet (27 June 1885 – 19 June 1966) was a French Egyptologist.

Biography

Montet was born in Villefranche-sur-Saône, Rhône, and began his studies under Victor Loret at the University of Lyon.

He excavated at Byblos i ...

, who unearthed eight additional shaft and chamber tombs. Each of the tombs consisted of a vertical shaft connected to a horizontal burial chamber at its bottom. Montet categorized the graves into two groups. The tombs of the first group date back to the Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, specifically the 19th century BC; some were unspoiled, and contained a multitude of often valuable items, including royal gifts from Middle Kingdom pharaohs Amenemhat III

:''See Amenemhat, for other individuals with this name.''

Amenemhat III (Ancient Egyptian: ''Ỉmn-m-hꜣt'' meaning 'Amun is at the forefront'), also known as Amenemhet III, was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the sixth king of the Twelfth Dyn ...

and Amenemhat IV

:''See Amenemhat, for other individuals with this name.''

Amenemhat IV (also known as Amenemhet IV) was the seventh and penultimateJürgen von Beckerath: ''Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen'', Münchner ägyptologische Studien, Heft 49, ...

, locally made Egyptian-style jewelry, and various serving vessels. The graves of the second group were all robbed in antiquity, making precise dating problematic, but the artifacts indicate that some of the tombs were used into the Late Bronze Age (16th to 11th centuries BC).

In addition to grave goods, seven stone sarcophagi were discovered—the burial chambers that did not contain stone sarcophagi appear to have housed wooden ones which disintegrated over time. The stone sarcophagi were undecorated, save the Ahiram sarcophagus

The Ahiram sarcophagus (also spelled Ahirom; Phoenician: ) was the sarcophagus of a Phoenician King of Byblos (c. 1000 BC), discovered in 1923 by the French excavator Pierre Montet in tomb V of the royal necropolis of Byblos.

The sarcophagus ...

. This sarcophagus is famed for its Phoenician inscription

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions, are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the societies and histories of the ancient Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic inscriptions may ...

, one of five epigraphs known as the Byblian royal inscriptions

The Byblian royal inscriptions are five inscriptions from Byblos written in an early type of Phoenician script, in the order of some of the kings of Byblos, all of which were discovered in the early 20th century.

They constitute the largest corp ...

; it is considered to be the earliest known example of the fully developed Phoenician alphabet

The Phoenician alphabet is an abjad (consonantal alphabet) used across the Mediterranean civilization of Phoenicia for most of the 1st millennium BC. It was one of the first alphabets, attested in Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions fo ...

. Montet compared the function of the Byblos tombs to that of Egyptian ''mastabas'', where the soul of the deceased was believed to fly from the burial chamber, through the funerary shaft, to the ground-level chapel where priests would officiate.

Historical background

Byblos (Jbeil) is one of the oldest continuously populated cities in the world. It has taken many names over the ages; it appears as Kebny in 4th-dynasty

Byblos (Jbeil) is one of the oldest continuously populated cities in the world. It has taken many names over the ages; it appears as Kebny in 4th-dynasty Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

hieroglyphic

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined ideographic, logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 1,000 distinct characters. ...

records, and as Gubla () in the Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

Amarna letters of 18th-dynasty-Egypt. In the second millennium BC, its name appeared in Phoenician inscriptions, such as the Ahiram sarcophagus

The Ahiram sarcophagus (also spelled Ahirom; Phoenician: ) was the sarcophagus of a Phoenician King of Byblos (c. 1000 BC), discovered in 1923 by the French excavator Pierre Montet in tomb V of the royal necropolis of Byblos.

The sarcophagus ...

epitaph, as Gebal (, ), which derives from (, "well

A well is an excavation or structure created on the earth by digging, driving, or drilling to access liquid resources, usually water. The oldest and most common kind of well is a water well, to access groundwater in underground aquifers. The ...

"), and (, "god

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

"). The name thus seems to have meant the "Well of the God". Another interpretation of the name Gebal is "mountain town", derived from the Canaanite Gubal. "Byblos" is a much later Greek exonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

, possibly a corruption of Gebal. The ancient settlement sat on a plateau next to the sea that has been continuously inhabited since as early as 7000–8000 BC. Simple, circular and rectangular habitation units and jar burial

Jar burial is a human burial custom where the corpse is placed into a large earthenware container and then interred. Jar burials are a repeated pattern at a site or within an archaeological culture. When an anomalous burial is found in which a co ...

s dating from the Chalcolithic

The Chalcolithic ( ) (also called the Copper Age and Eneolithic) was an archaeological period characterized by the increasing use of smelted copper. It followed the Neolithic and preceded the Bronze Age. It occurred at different periods in di ...

were unearthed in Byblos. The village grew during the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, and became a major center for trade with Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, and Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

.

Egypt sought to maintain favorable relations with Byblos because of its need for lumber, abundant in the mountains of Lebanon. During the Old Kingdom of Egypt

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning –2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth Dynasty ...

(–), Byblos was under the Egyptian sphere of influence. The city was destroyed by the Amorites

The Amorites () were an ancient Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic-speaking Bronze Age people from the Levant. Initially appearing in Sumerian records c. 2500 BC, they expanded and ruled most of the Levant, Mesopotamia and parts of Eg ...

around 2150 BC, in the aftermath of the power vacuum that ensued after the fall of the Old Kingdom. However, with the emergence of Egypt's Middle Kingdom (–), Byblos' defensive walls and temples were rebuilt, and it came once more allied to Egypt. In 1725 BC, Egypt's Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

and the coastal cities of Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

fell to the Hyksos

The Hyksos (; Egyptian language, Egyptian ''wikt:ḥqꜣ, ḥqꜣ(w)-wikt:ḫꜣst, ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''heqau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands"), in modern Egyptology, are the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt ( ...

as the Middle Kingdom disintegrated. A century and a half later, Egypt expelled the Hyksos and returned Phoenicia under its fold, and effectively defended it against the Mitanni

Mitanni (–1260 BC), earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, ; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat in Assyrian records, or in Ancient Egypt, Egyptian texts, was a Hurrian language, Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria (region), Syria an ...

and Hittite invasions. During this period, Gebalite trade flourished, and the first phonetic

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that studies how humans produce and perceive sounds or, in the case of sign languages, the equivalent aspects of sign. Linguists who specialize in studying the physical properties of speech are phoneticians ...

alphabet

An alphabet is a standard set of letter (alphabet), letters written to represent particular sounds in a spoken language. Specifically, letters largely correspond to phonemes as the smallest sound segments that can distinguish one word from a ...

was developed in Byblos. It consisted of 22 consonant grapheme

In linguistics, a grapheme is the smallest functional unit of a writing system.

The word ''grapheme'' is derived from Ancient Greek ('write'), and the suffix ''-eme'' by analogy with ''phoneme'' and other emic units. The study of graphemes ...

s that were simple enough for common traders to use.

Relations with Egypt dwindled again in the mid-14th century, as attested in the Amarna correspondence with the Gebalite king Rib-Hadda

Rib-Hadda (also rendered Rib-Addi, Rib-Addu, Rib-Adda) was king of Byblos during the mid fourteenth century BCE. He is the author of some sixty of the Amarna letters all to Akhenaten. His name is Akkadian in form and may invoke the Northwest Se ...

. The letters reveal the inability of Egypt to defend Byblos and its territories against Hittite incursion. During the time of Ramses II

Ramesses II (sometimes written Ramses or Rameses) (; , , ; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was an Pharaoh, Egyptian pharaoh. He was the third ruler of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Nineteenth Dynasty. Along with Thutmose III of th ...

, Egyptian hegemony over Byblos was restored; nevertheless, the city was destroyed soon after by the Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples were a group of tribes hypothesized to have attacked Ancient Egypt, Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean regions around 1200 BC during the Late Bronze Age. The hypothesis was proposed by the 19th-century Egyptology, Egyptologis ...

around 1195 BC. Egypt was weakened during this time, and consequently, Phoenicia experienced a period of prosperity and independence. The ''Story of Wenamun

The Story of Wenamun (alternately known as the Report of Wenamun, The Misadventures of Wenamun, Voyage of Unamūn, or nformallyas just Wenamun) is a literary text written in hieratic in the Late Egyptian language. It is only known from one incom ...

'', which is contemporaneous to this period, shows the continued, yet tepid relations between the Gebalite ruler and the Egyptians.

Longstanding relations with Egypt heavily influenced local culture and funerary practices. It is during the period of Egyptian overlordship that the practice of Egypt-inspired shaft burials appeared.

Excavation history

The search for the ancient city

Ancient texts and manuscripts hinted at the location of Gebal, which was lost to history until its rediscovery in the mid-19th century. In 1860, French biblical scholar and orientalist

Ancient texts and manuscripts hinted at the location of Gebal, which was lost to history until its rediscovery in the mid-19th century. In 1860, French biblical scholar and orientalist Ernest Renan

Joseph Ernest Renan (; ; 27 February 18232 October 1892) was a French Orientalist and Semitic scholar, writing on Semitic languages and civilizations, historian of religion, philologist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and critic. He wrote wo ...

carried out an archeological mission in Lebanon and Syria during the French expedition in the area. Renan had relied on ancient Greek historian and geographer Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

's writing in his attempt to locate the city. Strabo identified Byblos as a city situated on a hill some distance away from the sea. This description misled scholars, including Renan who thought that the city lay in the neighboring Qassouba (Kassouba), but he concluded that this hill was too small to have housed a grand ancient city.

Renan correctly posited that the ancient Byblos must have been located atop the circular hill dominated by the Crusader

Crusader or Crusaders may refer to:

Military

* Crusader, a participant in one of the Crusades

* Convair NB-36H Crusader, an experimental nuclear-powered bomber

* Crusader tank, a British cruiser tank of World War II

* Crusaders (guerrilla), a C ...

citadel of Jbeil, at the immediate outskirts of the modern city. He based his assumption on the reverse of a Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, 204 – 13 March 222), better known by his posthumous nicknames Elagabalus ( ) and Heliogabalus ( ), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short r ...

-era coin depicting a representation of the city with a river running at its feet, and theorized that the river in question was the stream that skirts the citadel hill. Starting from the citadel, he had two long trenches dug; the trenches revealed ancient artifacts demonstrating that Jbeil is the same as the ancient city of Gebal/Byblos.

Early archeological works

French Mandate

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (; , also referred to as the Levant States; 1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate founded in the aftermath of the First World War and the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, concerning the territori ...

, High Commissioner General Henri Gouraud

Henri Gouraud (17 November 1867 - 16 September 1946) was a French army general. He played a central role in the colonization of French Africa and the Levant. During World War I, he fought in major battles such as those of the Argonne, the Dard ...

established the Service of Antiquities in Lebanon; he appointed French archeologist Joseph Chamonard

Joseph Chamonard (11 November 1866 in Lyon – 29 November 1936 in Gières) was a French archaeologist.

Biography

A student of the École normale supérieure (1887), he became a member of the French School at Athens in 1890. In 1892 and 1893, he ...

to head the newly created service. Chamonard was succeeded by French epigrapher and archeologist Charles Virolleaud

Jean Charles Gabriel Virolleaud (2 July 1879 – 17 December 1968) was a French archaeologist, one of the excavators of Ugarit.

Virolleaud was the author of ''La légende du Christ'' (1908) and was an advocate of the Christ myth theory. He also ...

as of 1 October 1920. The service prioritized archeological surveys in the town of Jbeil where Renan had found ancient remains.

On 16 March 1921, Pierre Montet

Jean Pierre Marie Montet (27 June 1885 – 19 June 1966) was a French Egyptologist.

Biography

Montet was born in Villefranche-sur-Saône, Rhône, and began his studies under Victor Loret at the University of Lyon.

He excavated at Byblos i ...

, the Egyptology professor at the University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers. Founded in the 16th century by Johannes Sturm, it was a center of intellectual life during ...

, addressed a letter to the French archeologist Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau

Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau (19 February 1846 – 15 February 1923) was a noted French Orientalist and archaeologist.

Biography

Clermont-Ganneau was born in Paris, the son of Simon Ganneau, a sculptor and mystic who died in 1851 when Clerm ...

describing Egyptian-inscribed relief

Relief is a sculpture, sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''wikt:relief, relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give ...

s he had discovered during a 1919 archeological mission in Jbeil. The fascinated Clermont-Ganneau personally funded the methodological survey of the site, which he believed contained an Egyptian temple. Montet was selected to head the excavations, and arrived at Beirut on 17 October 1921. Excavation works in Jbeil were inaugurated on 20 October 1921 by the French mandate authorities. They consisted of annual campaigns of three months each.

Discovery of the royal necropolis

On 16 February 1922, heavy rain triggered a landslide on the seaside cliff of Jbeil which exposed an underground man-made cavity. The next day the administrative advisor of

On 16 February 1922, heavy rain triggered a landslide on the seaside cliff of Jbeil which exposed an underground man-made cavity. The next day the administrative advisor of Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon (, ; , ; ) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It is about long and averages above in elevation, with its peak at . The range provides a typical alpine climate year-round.

Mount Lebanon is well-known for its snow-covered mountains, ...

informed the Service of Antiquities of the landslide and announced the discovery of an ancient underground tomb containing a large unopened sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (: sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a coffin, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:σάρξ, σάρξ ...

. To keep treasure hunters at bay, the perimeter was secured by the '' Mudir'' of Jbeil Sheikh Wadih Hobeiche. Virolleaud arrived at the site to clear and make an inventory of the contents of the unearthed tomb; he continued to supervise the digs and opened the discovered sarcophagus on 26 February 1922. A second tomb (named Tomb II) was discovered by Montet in October 1923; the discovery triggered a systematic survey of the surrounding area in late 1923. Montet headed the excavation of ancient Byblos until 1924; during this period, he uncovered seven other tombs, bringing the total number to nine. French archeologist Maurice Dunand

Maurice Dunand (4 March 1898 – 23 March 1987) was a prominent French archaeologist specializing in the ancient Near East, who served as director of the Mission Archéologique Française in Lebanon. Dunand excavated Byblos from 1924 to 1975, and ...

succeeded Montet in 1925 and continued his predecessor's work on the archeological tell for another forty years.

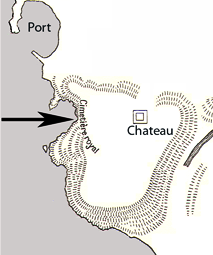

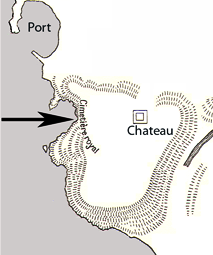

Location

Located north ofBeirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

, ancient Byblos/Gebal (modern name: Jbeil/Gebeil) lays south of the city's medieval center. It sits on a seaside promontory consisting of two hills separated by a dell

Dell Inc. is an American technology company that develops, sells, repairs, and supports personal computers (PCs), Server (computing), servers, data storage devices, network switches, software, computer peripherals including printers and webcam ...

. A deep well provided the settlement with fresh water. The highly defensible archeological tell of Byblos is flanked by two harbors that were used for sea trade. The royal necropolis of Byblos is a semicircular burial ground located on the promontory summit, on a spur overlooking both seaports of the city, within the walls of ancient Byblos.

Description

Montet assigned numbers to the royal tombs and categorized them into two groups: the first, northern group included tombs I to IV; these were of an older construction date and were meticulously built. Tombs III and IV had been emptied of their contents by ancient looters, while the other two remained undisturbed. The second group of tombs is located at the southern side of the necropolis, it includes tombs V to IX. Tombs V to VIII were of inferior construction quality compared to northern ones, and were dug in clay instead of rock at a later period of time. Only Tomb IX retained evidence of careful construction reminiscent of the earlier tombs. Earthenware fragments discovered in this tomb, bearing the name of Abishemu in Egyptian hieroglyphs, suggest that its construction date was closer to that of the northern group. Ancient looters had broken into all the tombs of the second group.Tombs I and II

Tomb I consists of a wide by deep square vertical shaft giving access to an underground burial chamber carved partly from solid rock and partly fromclay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

. The west wall, which isolated it from the exterior seaside cliff, had collapsed during the 1922 landslide. The grave goods

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are items buried along with a body.

They are usually personal possessions, supplies to smooth the deceased's journey into an afterlife, or offerings to gods. Grave goods may be classed by researche ...

were not affected by the landslide; inside the burial chamber the excavators discovered several pottery jars in the damp clay, and a large white limestone sarcophagus with three protruding lugs on its lid by which it could be manipulated.

The sarcophagus was placed in a north–south orientation. A rock-cut opening is present at a height of on the north wall of Tomb I's chamber, directly facing the sarcophagus. The opening leads to a high and to wide corridor that joins the south side of the shaft of Tomb II. The same corridor is joined by a passageway emerging from the northwestern angle of Tomb I's shaft. Midway between Tomb I and the shaft of Tomb II the S-shaped corridor opens, to its north side, onto a small nondescript hole giving access to a roughly cut round cavity housing an archaic tomb.

A coarsely built wall separated the chamber of Tomb I from its shaft. The shaft was filled to its brim with stones and mortar. The same material was used to build a platform around the shaft, on top of which were laid the foundations of a ''

The sarcophagus was placed in a north–south orientation. A rock-cut opening is present at a height of on the north wall of Tomb I's chamber, directly facing the sarcophagus. The opening leads to a high and to wide corridor that joins the south side of the shaft of Tomb II. The same corridor is joined by a passageway emerging from the northwestern angle of Tomb I's shaft. Midway between Tomb I and the shaft of Tomb II the S-shaped corridor opens, to its north side, onto a small nondescript hole giving access to a roughly cut round cavity housing an archaic tomb.

A coarsely built wall separated the chamber of Tomb I from its shaft. The shaft was filled to its brim with stones and mortar. The same material was used to build a platform around the shaft, on top of which were laid the foundations of a ''mastaba

A mastaba ( , or ), also mastabah or mastabat) is a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides, constructed out of mudbricks or limestone. These edifices marked the burial sites ...

''-like building. Little remains of the Egyptian-inspired structure because it was replaced by a Roman period bath. Unlike the shaft of Tomb I, the shaft of Tomb II was not closed off with stones and cement, but only with earth. A thick slab of five to six rows of blocks covered the shaft opening and provided a foundation for a construction from which only a few masonry blocks remain.

The shaft of Tomb II is shallower than that of Tomb I; a single course wall separated it from the burial chamber. Tomb II did not contain any burial receptacles upon its discovery. A number of pottery jars and other artifacts sank in a thick layer of clay, with some of the jars damaged by falling rock fragments from the chamber's ceiling. The ceiling of Tomb II's burial chamber is high at the center of the room; it slopes down to a height of only at its northern wall. Four stones were found at the center of the chamber, they supported a wooden coffin that had disintegrated, leaving rich grave goods scattered in the clay.

Montet demonstrated that Tombs I and II were not broken into before their discovery in 1922–1923, contrary to what his predecessor Virolleaud reported. Virolleaud had found shards of glass lodged in the Tomb I chamber wall and assumed they dated from Roman times.

Tombs III and IV

The shafts of Tombs III and IV are west of Tombs I and II, adjacent to the northern wall of the Roman baths. The shaft opening of Tomb III measures ; it was covered by a heavy layer of cement covering a masonry course sealed with ash, and vertically pierced close to its south-west angle by a square conduit reminiscent in function to that of Egyptian ''mastabas''Tomb V (King Ahiram's Tomb)

The semicircular shape of Tomb V, known as King Ahiram's tomb, is unique within the necropolis. It was found half-filled with mud, with three tombs inside; a large plain one close to the wall, the finely carved Ahiram sarcophagus at the center, and a smaller plain sarcophagus. It was also the only tomb to have an inscription within its shaft. This Phoenician inscription, dubbed theByblos Necropolis graffito

The Byblos Necropolis graffito is a Phoenician inscription situated in the Royal necropolis of Byblos.

The graffito of Ahiram's tomb was found on the south wall of the shaft leading to the hypogeum, about three meters from the opening.

The th ...

, is found at a depth of on the south wall of the shaft; it warns looters from entering the grave. French epigrapher René Dussaud

René Dussaud (; December 24, 1868 – March 17, 1958) was a French Orientalism, Orientalist, archaeology, archaeologist, and epigraphy, epigrapher. Among his major works are studies on the religion of the Hittites, the Hurrians, the Phoenicians a ...

interpreted the inscription as "Avis, voici ta perte (est) ci-dessous" eware, here is your loss (is) below

The shaft of Ahiram's tomb is located midway between the northern tombs group (Tombs I, II, III, and IV) and the southern group (Tombs VI, VII, VIII, and IX). It is flanked on the west by a two course wall and column bases that were part of the tomb's superstructure. The soil on top of the shaft was very compacted; a conduit similar to the ones found in tombs III and IV measuring was found in the northeast corner of the shaft. Molded fragments and marble plates, and numerous shards of pottery, which were markedly different from the ceramic fragments collected in the other tombs, were mixed with the earth used to fill the shaft. Two levels of four square slots are carved at depths of and respectively on both of the shaft's east and west walls. These four rows of slots used to hold two rows of wooden vertical beams and floors spanning the width of the shaft. According to Montet, the builders of the tomb did not consider that the king's corpse was sufficiently protected by the shaft's surface paving slabs and by the wall built at the entrance to the chamber halfway up the shaft, so they laid wooden beams which acted as a third obstacle. The looters removed the paving and dug out the wooden structures; as they emptied the shaft, they could not have missed seeing the warning spell on their way down to the royal grave.

Below the beam slots no additional pottery shards were found, but near the bottom, against the eastward entrance to the burial chamber, several fragments of alabaster vases that had been cast out of the chamber had collected. One of these fragments bore the name of Ramses II. The excavators found that the wall that closed off the burial chamber had partly collapsed, and the content of the room was disorderly and half-filled with muddy clay. A huge block of rock, fallen from the vault, rested atop the decorated sarcophagus of Ahiram that occupied the center of the chamber. All of the three chamber sarcophagi were looted and only contained human bones.

Tombs VI, VII, VIII, and IX

This group of tombs is located east of the necropolis cliffside and south of shaft IV; they are built in a part of the hill with a heavysedimentary deposit

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock formed by the cementation of sediments—i.e. particles made of minerals (geological detritus) or organic matter (biological detritus)—that have been accumulated or deposited at Earth's surface. Sedimentat ...

. The shafts of these tombs are less well-preserved than the shafts of the first group. The shaft of Tomb VIII was still covered with a layer of pavement, while Tombs VI and VII had lost most of their surface cover. The burial chambers of Tombs VI, VII, VIII, and IX are completely dug in muddy soil. Grave robbers were able to burrow from one tomb to the next through the soft clay.

The shaft of Tomb VI is the deepest of the all the necropolis' shafts. An ashlar

Ashlar () is a cut and dressed rock (geology), stone, worked using a chisel to achieve a specific form, typically rectangular in shape. The term can also refer to a structure built from such stones.

Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, a ...

wall supported the shaft down to a depth of ; beyond this depth the shaft continues through the muddy soil, without any masonry retaining wall. Like the rest of this tomb group, Tomb VI was robbed of its content except for a few artifacts that lay in, and at the entrance of the chamber. There were no stone sarcophagi in this tomb.

Tomb VII has the largest of the burial shafts, with sides measuring each. The chamber of Tomb VII was dug like that of Tomb VI through hard rock and the underlying clay, and was found two-thirds filled with clay and pebbles. At the time of its excavation, the cambered lid of a stone sarcophagus rose through the layer of clay. The stone sarcophagus laid on a layer of stone pavement, and courses of stone that were in a relatively good state of conservation supported the walls of the chamber. The body of the sarcophagus of Tomb VII is roughly cut and is of simple rectangular shape. Two large lugs jut from each of the extremities of the concave lid that, like those of the sarcophagus of Tomb I, were used to manipulate the heavy cover. This tomb contained a good number of precious artifacts and jewels that appear to have been missed by looters.

Tomb VIII is characterized by a rhomboid

Traditionally, in two-dimensional geometry, a rhomboid is a parallelogram in which adjacent sides are of unequal lengths and angles are non-right angled.

The terms "rhomboid" and "parallelogram" are often erroneously conflated with each oth ...

shaped opening, which evens into a square at the bottom. The thin wall separating Tomb VIII from Tomb VI is perforated in its center, and Montet assumed that it was due to a quarrying accident. The shaft also reaches the layer of clay underlying the hard rock upper layer, and the tomb chamber was found filled with clay and gravel. The chamber had retaining walls, most of which had collapsed, and small pebbles covered the floor. A simple stone sarcophagus, a few fragments of alabaster vases, and other earthenware items were found in the tomb. No precious artifacts were recovered, except for gold foils that were mixed with the tomb's muddy soil.

The shaft of Tomb IX cuts through of rock. The wall closing off the chamber was not broken into, the looters had burrowed instead through the clay layer to access the chambers of Tomb V, VIII, and IX. The roof of Tomb IX had collapsed, and it was found filled to the brim with mud and ceiling rock shards. The chamber floor was covered by paving stones, and its walls were sturdy and in good condition. The looters almost completely emptied the contents of the tomb except for alabaster, malachite

Malachite () is a copper Carbonate mineral, carbonate hydroxide mineral, with the chemical formula, formula Basic copper carbonate, Cu2CO3(OH)2. This opaque, green-banded mineral crystallizes in the monoclinic crystal system, and most often for ...

, and pottery receptacle fragments. Among the finds were terracotta artifacts bearing the names of two Gebalite kings, Abi (possibly a name contraction) and Abishemu.

Section

Section, Sectioning, or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especially of a chapter, in books and documents

** Section sig ...

view of tombs I and II

File:BAH 11 Montet, Pierre - Byblos et l'Egypte Quatre campagnes de fouilles à Gebeil 1921-1922-1923-1924 Atlas (1929) LR 0119.jpg, alt=A group of two sketches of a burial shaft and chamber, Plan and section of Tomb III

File:BAH 11 Montet, Pierre - Byblos et l'Egypte Quatre campagnes de fouilles à Gebeil 1921-1922-1923-1924 Atlas (1929) LR 0116.jpg, alt=A sketch of a cross-section of a number of shaft tombs, Section views of tombs I, III and IV

File:BAH 11 Montet, Pierre - Byblos et l'Egypte Quatre campagnes de fouilles à Gebeil 1921-1922-1923-1924 Atlas (1929) LR 0168 (cropped).jpg, alt=A group of three sketches showing a burial chamber with three rectangles representing sarcophagi, and two burial shafts, Plan of Ahiram's tomb and shaft section view

File:BAH 11 Montet, Pierre - Byblos et l'Egypte Quatre campagnes de fouilles à Gebeil 1921-1922-1923-1924 Atlas (1929) LR 0120.jpg, alt=A group of four sketches showing burial shafts and chambers, Plan and section view of tombs IV, VII, and VIII

Finds

Sarcophagi

In total, seven stone sarcophagi were discovered in the royal necropolis of Byblos; a single sarcophagus in each of tombs I, IV, VII, VIII and three in Ahiram's tomb (Tomb V). The other burial chambers are believed to have housed wooden caskets that have disintegrated over time. Tomb II housed a wooden casket that has rotted away, leaving a wealth of objects laying on the burial chamber floor. The stone sarcophagi found in tombs I and IV are of fine white limestone sourced from the nearby Lebanese mountains; the walls of both sarcophagi are thick, well-polished, and undecorated. Moreover, the sarcophagi found in tombs I, IV, V, and VII share the same morphology which resembles the common stone sarcophagi of Egypt. One difference is that the lids of these Gebalite sarcophagi retain the lid lugs which allowed workmen to maneuver them. These features, along with a number of tomb contents including similarly shaped alabaster containers, suggest that the entire group can be attributed to a restricted time period. The sarcophagus of Tomb I measures , and is tall. The side walls of the sarcophagus are thick; the bottom of the sarcophagus body is thick. The rim of the Sarcophagus I lid is beveled; it is cut from below so as to enter a few centimeters into the sarcophagus body. The back of the lid is rounded and striated with lengthwise irregularly sized

The sarcophagus of Tomb I measures , and is tall. The side walls of the sarcophagus are thick; the bottom of the sarcophagus body is thick. The rim of the Sarcophagus I lid is beveled; it is cut from below so as to enter a few centimeters into the sarcophagus body. The back of the lid is rounded and striated with lengthwise irregularly sized flutes

The flute is a member of a family of musical instruments in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, producing sound with a vibrating column of air. Flutes produce sound when the player's air flows across an opening. In th ...

. The central flute is the widest; it is flanked by five successively smaller flutes on each side. Three lugs protrude obliquely from the lid's exterior close to its corners; the lug at the northwestern corner and an entire corner section of the lid have broken off at the foot of the sarcophagus. The sarcophagus was opened on 26 February 1922.

The sarcophagus of Tomb IV measures and is tall. The body of the sarcophagus is slightly more sophisticated as both of its long sides are beveled at the top and bottom. The small sides have a bench-like protrusion at the base. Montet ascertained that the sarcophagus never had a stone lid; he found blackish traces on the rim of the sarcophagus body that show that it was covered by a curved wooden lid.

The sarcophagi of tombs IV, V and VII were extracted during the fifth campaign, which lasted from 8 March 1926 until 26 June 1926.

The Ahiram sarcophagus

Thesandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

sarcophagus of Ahiram was found in Tomb V and is so called for its bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

carvings, and its Phoenician inscription

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions, are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the societies and histories of the ancient Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic inscriptions may ...

that attributes it to King Ahiram. The inscription with 38 words is one of five known Byblian royal inscriptions

The Byblian royal inscriptions are five inscriptions from Byblos written in an early type of Phoenician script, in the order of some of the kings of Byblos, all of which were discovered in the early 20th century.

They constitute the largest corp ...

. It is written in Old Phoenician dialect, and is considered to be the earliest known example of the fully developed Phoenician alphabet discovered to date. For some scholars, the Ahiram sarcophagus inscription represents the ''terminus post quem

A ''terminus post quem'' ('limit after which', sometimes abbreviated TPQ) and ''terminus ante quem'' ('limit before which', abbreviated TAQ) specify the known limits of dating for events or items..

A ''terminus post quem'' is the earliest date t ...

'' of the transmission of the alphabet to Europe. The sarcophagus measures long by wide and is tall, lid included.

The top of the sarcophagus body is ringed by a frieze of inverted lotus flowers

''Nelumbo nucifera'', also known as the pink lotus, sacred lotus, Indian lotus, or simply lotus, is one of two extant species of aquatic plant in the family Nelumbonaceae. It is sometimes colloquially called a water lily, though this more oft ...

. The flowers alternate between closed buds and open flowers. A motif of thick rope frames the top of the main bas-relief scene, and corner pillars decorate all four sides of the sarcophagus. The body of the sarcophagus rests on four lions on all four sides. The heads and front legs of the lions protrude outside the sarcophagus tank, while the rest of the lions' bodies appear in bas-relief on the long sides.

The main scene on the front of the sarcophagus depicts the king on a throne holding a wilted lotus flower. A table full of offerings stands in front of the throne, followed by a procession of seven male figures. Two scenes of a funerary procession of four mourning women occupy the two small sides of the sarcophagus. Two of the women on each of the sides bare their chests, and the two others are depicted hitting their heads with their hands. The scene on the back side of the sarcophagus shows a procession of men and women bearing offerings.

The lid of the sarcophagus is slightly

The main scene on the front of the sarcophagus depicts the king on a throne holding a wilted lotus flower. A table full of offerings stands in front of the throne, followed by a procession of seven male figures. Two scenes of a funerary procession of four mourning women occupy the two small sides of the sarcophagus. Two of the women on each of the sides bare their chests, and the two others are depicted hitting their heads with their hands. The scene on the back side of the sarcophagus shows a procession of men and women bearing offerings.

The lid of the sarcophagus is slightly convex

Convex or convexity may refer to:

Science and technology

* Convex lens, in optics

Mathematics

* Convex set, containing the whole line segment that joins points

** Convex polygon, a polygon which encloses a convex set of points

** Convex polytop ...

, like those of the neighboring sarcophagi. It has only one lug at each end, which are shaped like lion heads. The bodies of the lions are carved in bas-relief on the flat part of the lid. Two bearded effigies measuring each are carved on either side of the lions; one of the figures bears a wilted lotus flower, the other a live one. Montet posited that they both represent the deceased king. Lebanese archeologist and museum curator Maurice Chehab

Emir Maurice Hafez Chehab (27 December 1904 – 24 December 1994) was a Lebanese archaeologist and museum curator. He was the head of the Antiquities Service in Lebanon and curator of the National Museum of Beirut from 1942 to 1982. He was ...

, who later demonstrated the presence of traces of red paint on the sarcophagus, interpreted the two figures as the deceased king and his son.

The sarcophagus inscription is composed of 38 words distributed in two parts, the shorter of which is found on the sarcophagus body, in the space of the narrow band above the row of lotus flowers. The longer inscription is carved on the front, long edge of the lid. The inscription is cautionary and conjures calamities on whoever desecrates the tomb.

Grave goods

More than 260 items were recovered from the royal necropolis of Byblos.

More than 260 items were recovered from the royal necropolis of Byblos.

Egyptian royal gifts

Tomb I contained a highobsidian

Obsidian ( ) is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock. Produced from felsic lava, obsidian is rich in the lighter element ...

vase and lid set with gold, engraved with the enthronement name of Amenemhat III

:''See Amenemhat, for other individuals with this name.''

Amenemhat III (Ancient Egyptian: ''Ỉmn-m-hꜣt'' meaning 'Amun is at the forefront'), also known as Amenemhet III, was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the sixth king of the Twelfth Dyn ...

in hieroglyphic characters. The same grave also produced two alabaster vases.

Two royal Egyptian gifts were found in Tomb II. The first is a rectangular, long obsidian box and lid set with gold. The box rests on four legs, and its lid bears a perfectly preserved Egyptian hieroglyphic cartouche

upalt=A stone face carved with coloured hieroglyphics. Two cartouches - ovoid shapes with hieroglyphics inside - are visible at the bottom., Birth and throne cartouches of Pharaoh KV17.html" ;"title="Seti I, from KV17">Seti I, from KV17 at the ...

containing the enthronement name and epithet

An epithet (, ), also a byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) commonly accompanying or occurring in place of the name of a real or fictitious person, place, or thing. It is usually literally descriptive, as in Alfred the Great, Suleima ...

s of Amenemhat IV

:''See Amenemhat, for other individuals with this name.''

Amenemhat IV (also known as Amenemhet IV) was the seventh and penultimateJürgen von Beckerath: ''Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen'', Münchner ägyptologische Studien, Heft 49, ...

. It is not clear what the contents of the box may have been; similarly shaped receptacles were often depicted on Egyptian tomb friezes and called "''pr 'nti''" which translate to "house of incense". The second gift is a stone vase carved with the name of Amenemhat IV; the cartouche reads: "Long live The Good God, son of Ra, Amenemhat, living forever".

Jewelry and precious objects

The tombs contained royal jewelry made from gold, silver and gemstones, some of which bear a heavy Egyptian influence. Each of tombs I, II and III contained chiseled gold Egyptian-influenced pectorals. Tomb II contained an Egyptian-style, locally produced gem-encrusted gold pectoral with its chain and a shell-shapedcloisonné

Cloisonné () is an ancient technology, ancient technique for decorating metalwork objects with colored material held in place or separated by metal strips or wire, normally of gold. In recent centuries, vitreous enamel has been used, but inla ...

pendant bearing the name of King Ip-Shemu-Abi. Two grand silver hand mirrors were recovered in tombs I and II; all of the three tombs contained bracelets and rings in gold and amethyst, silver sandals and intricately decorated and inscribed ''khopesh

The ''khopesh'' ('; also vocalized khepesh) is an Egyptian sickle-shaped sword that developed from battle axes. The sword style originated in Western Asia during the Bronze Age and was introduced in the Second Intermediate Period.Lloyd, Alan B. ...

'' arms made from bronze and gold. The ''khopesh'' of tomb II bears the name of its owner, King Ip-Shemu-Abi and his father Abishemu. Other grave goods include a silver knife decorated with niello

Niello is a black mixture, usually of sulphur, copper, silver, and lead, used as an inlay on engraved or etched metal, especially silver. It is added as a powder or paste, then fired until it melts or at least softens, and flows or is push ...

and gold, several bronze trident

A trident (), () is a three- pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm. As compared to an ordinary spear, the three tines increase the chance that a fish will be struck and decrease the chance that a fish will b ...

s, finely decorated teapot-shaped silver vases and various other vessels made of gold, silver, bronze, alabaster and terracotta.

Tomb I contained a rare find consisting of a fragment of a silver vase with spiral decorative patterns which French art history expert Edmond Pottier

Edmond François Paul Pottier (13 August 1855, Saarbrücken – 4 July 1934, Paris) was an art historian and archaeologist who was instrumental in establishing the Corpus vasorum antiquorum. He was a pioneering scholar in the study of Pottery of A ...

likened to those of the gold oenochoe

An oenochoe, also spelled ''oinochoe'' (; from , ''oînos'', "wine", and , ''khéō'', , sense "wine pourer"; : ''oinochoai''; Neo-Latin: ''oenochoë'', : ''oenochoae''; English : oenochoes or oinochoes), is a wine jug and a key form of ancient ...

from Tomb IV of Mycenae. This silver vase demonstrates either Aegean artistic influence on local Gebalite art or could be proof of trade with Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; ; or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines, Greece, Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos, Peloponnese, Argos; and sou ...

.

Dating

French priest and archeologist Father Louis-Hugues Vincent, Pierre Montet, and other early scholars believed the tombs belonged to the Kings of Byblos of the Middle and Late Bronze Age, based on the characteristics of the painted pottery shards.Tomb I, II, and III

According to Virolleaud and Montet, the lavish Tombs I, II and III date back to theMiddle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, specifically the Twelfth Dynasty

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is a series of rulers reigning from 1991–1802 BC (190 years), at what is often considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom (Dynasties XI–XIV). The dynasty periodically expanded its terr ...

of Middle Kingdom Egypt (19th century BC). Montet based his dating on grave goods and royal Egyptian gifts found in the three tombs. Tomb I housed an ointment jar etched with the cartouche of Amenemhat III, and Tomb II contained an obsidian box bearing the name of his son and successor Amenemhat IV.

Tomb V to IX

Montet matched the style of the pottery shards that he uncovered in the shaft of Tomb V to the vases found by EnglishEgyptologist

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , ''-logia''; ) is the scientific study of ancient Egypt. The topics studied include ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end ...

Flinders Petrie

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie ( – ), commonly known as simply Sir Flinders Petrie, was an English people, English Egyptology, Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and the preservation of artefacts. ...

in the ruins of the palace of Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton ( ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning 'Effective for the Aten'), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eig ...

at Amarna

Amarna (; ) is an extensive ancient Egyptian archaeological site containing the ruins of Akhetaten, the capital city during the late Eighteenth Dynasty. The city was established in 1346 BC, built at the direction of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, and a ...

. Both featured large brown or black painted bands, which divide the body of the receptacles into several parts, each of which contained vertical lines and circular motifs. The small vase handles are of identical shape. These similarities lead Montet to conclude that the Gebalite pottery shards were contemporary with the New Kingdom of Egypt

The New Kingdom, also called the Egyptian Empire, refers to ancient Egypt between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC. This period of History of ancient Egypt, ancient Egyptian history covers the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth, ...

( –).

The other graves of the second group (tombs VI to IX) were all robbed in antiquity, making precise dating problematic. Some signs point to a range spanning from the end of the Middle Bronze Age to the Late Bronze Age.

Attribution

Scholars, following the French art history expert Edmond Pottier, have noted the similarity of the spiral decorative patterns found in Tomb I to those of the goldoenochoe

An oenochoe, also spelled ''oinochoe'' (; from , ''oînos'', "wine", and , ''khéō'', , sense "wine pourer"; : ''oinochoai''; Neo-Latin: ''oenochoë'', : ''oenochoae''; English : oenochoes or oinochoes), is a wine jug and a key form of ancient ...

found in Tomb IV in Mycenae.Compare

Comparison or comparing is the act of evaluating two or more things by determining the relevant, comparable characteristics of each thing, and then determining which characteristics of each are similar to the other, which are different, and t ...

Function

Montet likened the Byblos tombs to ''mastabas'' and explained that inancient Egyptian funerary texts

The literature that makes up the ancient Egyptian funerary texts is a collection of religious documents that were used in ancient Egypt, usually to help the spirit of the concerned person to be preserved in the afterlife.

They evolved over time, ...

, the soul of the deceased was believed to fly from the burial chamber, through the funerary shaft, to the ground-level chapel where priests would officiate. He likened the tunnel connecting Tombs I and II to the tomb of Aba the son of Zau, a high official contemporaneous with Pharaoh Pepi II

Pepi II Neferkare ( 2284 BC – 2214 BC) was a pharaoh, king of the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt, Sixth Dynasty in Egypt's Old Kingdom. His second name, Neferkare (''Nefer-ka-Re''), means "Beautiful is the Ka (Egyptian soul), Ka of Re (Egyptian religi ...

, who was buried in Deir el-Gabrawi in the same tomb as his father. Aba left an inscription detailing how he chose to share the tomb of his father to "be with him in the same place".

See also

* * *Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Cite book , last=Wilkinson , first=Toby , url=https://books.google.com/books?id=L-mWx_EM9tEC , title=The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt , publisher=A&C Black , year=2011 , isbn=9780679604297 , location=New York , page= , oclc=710823381 , author-link=Toby Wilkinson 1922 archaeological discoveries Ancient cemeteries in Lebanon Archaeological parks Archaeological sites in Lebanon Bronze Age sites in Lebanon History of Byblos Necropoleis Phoenician funerary practices Phoenician sites in Lebanon