Rockefeller Fellow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American

On May 14, 1913, New York Governor

On May 14, 1913, New York Governor  Junior became the foundation chairman in 1917. Through the ''Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial'' (LSRM), established by Senior in 1918 and named after his wife, the Rockefeller fortune was for the first time directed to supporting research by social scientists. During its first few years of work, the LSRM awarded funds primarily to social workers, with its funding decisions guided primarily by Junior. In 1922, Beardsley Ruml was hired to direct the LSRM, and he most decisively shifted the focus of Rockefeller philanthropy into the

Junior became the foundation chairman in 1917. Through the ''Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial'' (LSRM), established by Senior in 1918 and named after his wife, the Rockefeller fortune was for the first time directed to supporting research by social scientists. During its first few years of work, the LSRM awarded funds primarily to social workers, with its funding decisions guided primarily by Junior. In 1922, Beardsley Ruml was hired to direct the LSRM, and he most decisively shifted the focus of Rockefeller philanthropy into the  C. Douglas Dillon, the

C. Douglas Dillon, the

The Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of

The Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of  During the late-1920s, the Rockefeller Foundation created the Medical Sciences Division, which emerged from the former Division of Medical Education. The division was led by Richard M. Pearce until his death in 1930, to which Alan Gregg succeeded him until 1945. During this period, the Division of Medical Sciences made contributions to research across several fields of psychiatry. In 1935 the foundation granted $100000 to the Institute for Psychoanalysis in Chicago. This grant was renewed in 1938, with payments extending into the early-1940s. This division funded women's contraception and the human reproductive system in general, but also was involved in funding controversial

During the late-1920s, the Rockefeller Foundation created the Medical Sciences Division, which emerged from the former Division of Medical Education. The division was led by Richard M. Pearce until his death in 1930, to which Alan Gregg succeeded him until 1945. During this period, the Division of Medical Sciences made contributions to research across several fields of psychiatry. In 1935 the foundation granted $100000 to the Institute for Psychoanalysis in Chicago. This grant was renewed in 1938, with payments extending into the early-1940s. This division funded women's contraception and the human reproductive system in general, but also was involved in funding controversial

The foundation also owns and operates the Bellagio Center in

The foundation also owns and operates the Bellagio Center in

A total of 100 cities across six continents were part of the 100 Resilient Cities program funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. In January 2016, the United States

A total of 100 cities across six continents were part of the 100 Resilient Cities program funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. In January 2016, the United States

, "

J. George Harrar

– 20 January 1961 – 3 October 1972; plant pathologist, "generally regarded as the father of 'the Green Revolution.'" * John Hilton Knowles – 3 October 1972 – 31 December 1979; physician, general director of the

online

* Birn, Anne-Emanuelle, and

online

* Brown, E. Richard, ''Rockefeller Medicine Men: Medicine and Capitalism in America'', Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979. * Chernow, Ron, ''Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller Sr.'', London: Warner Books, 1998

online

* Cotton, James. "Rockefeller, Carnegie, and the limits of American hegemony in the emergence of Australian international studies." ''International Relations of the Asia-Pacific'' 12.1 (2012): 161–192. [ * Dowie, Mark, ''American Foundations: An Investigative History'', Boston: The MIT Press, 2001. * Eckl, Julian. "The power of private foundations: Rockefeller and Gates in the struggle against malaria." ''Global Social Policy'' 14.1 (2014): 91–116. * Erdem, Murat, and W. ROSE Kenneth. "American Philanthropy ın Republican Turkey; The Rockefeller and Ford Foundations." ''The Turkish Yearbook of International Relations'' 31 (2000): 131–157

online

* Farley, John. ''To cast out disease: a history of the International Health Division of Rockefeller Foundation (1913-1951)'' (Oxford University Press, 2004). * Fisher, Donald, ''Fundamental Development of the Social Sciences: Rockefeller Philanthropy and the United States Social Science Research Council'', Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1993. * Fosdick, Raymond B., ''John D. Rockefeller Jr., A Portrait'', New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956. * Fosdick, Raymond B., ''The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation'' (1952

online

* Hauptmann, Emily. "From opposition to accommodation: How Rockefeller Foundation grants redefined relations between political theory and social science in the 1950s." ''American Political Science Review'' 100.4 (2006): 643–649

online

* Jonas, Gerald. ''The Circuit Riders: Rockefeller Money and the Rise of Modern Science''. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1989

online

* Kay, Lily, ''The Molecular Vision of Life: Caltech, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Rise of the New Biology'', New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. * Laurence, Peter L. "The death and life of urban design: Jane Jacobs, The Rockefeller Foundation and the new research in urbanism, 1955–1965." ''Journal of Urban Design'' 11.2 (2006): 145–172

online

* Lawrence, Christopher. ''Rockefeller Money, the Laboratory and Medicine in Edinburgh 1919–1930: New Science in an Old Country'', Rochester Studies in Medical History, University of Rochester Press, 2005. * Mathers, Kathryn Frances. ''Shared journey: The Rockefeller Foundation, human capital, and development in Africa'' (2013

online

* Nielsen, Waldemar, ''The Big Foundations'', New York: Cambridge University Press, 1973

online

* Nielsen, Waldemar A., ''The Golden Donors'', E. P. Dutton, 1985. Called Foundation "unimaginative ... lacking leadership....slouching toward senility.

online

* Ninkovich, Frank. "The Rockefeller Foundation, China, and Cultural Change." ''Journal of American History'' 70.4 (1984): 799–820

online

* Palmer, Steven,

Launching Global Health: The Caribbean Odyssey of the Rockefeller Foundation

'', Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010. * Perkins, John H. "The Rockefeller Foundation and the green revolution, 1941–1956." ''Agriculture and Human Values'' 7.3 (1990): 6–18

online

* Sachse, Carola. ''What Research, to What End? The Rockefeller Foundation and the Max Planck Gesellschaft in the Early Cold War'' (2009

online

* Shaplen, Robert, ''Toward the Well-Being of Mankind: Fifty Years of the Rockefeller Foundation'', New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964. * * Theiler, Max and Downs, W. G., ''The Arthropod-Borne Viruses of Vertebrates: An Account of The Rockefeller Foundation Virus Program, 1951–1970''. (1973) Yale University Press. New Haven and London. . * Uy, Michael Sy. ''Ask the Experts: How Ford, Rockefeller, and the NEA Changed American Music'', (Oxford University Press, 2020) 270pp. * Wood, Andrew Grant. "Sanitizing the State: The Rockefeller International Health Board and the Yellow Fever Campaign in Veracruz." ''Americas'' 6#1 Spring 2010 · * Youde, Jeremy. "The Rockefeller and Gates Foundations in global health governance." ''Global Society'' 27.2 (2013): 139–158

online

Rockefeller Foundation 990

100 Years: The International Health Board

The Rockefeller Foundation/Rockefeller Archive Center.

CFR Website – Continuing the Inquiry: The Council on Foreign Relations from 1921 to 1996

The history of the council by Peter Grose, a council member – mentions financial support from the Rockefeller foundation.

Foundation Center: Top 50 US Foundations by total giving

* ttps://www.sfgate.com/opinion/article/Eugenics-and-the-Nazis-the-California-2549771.php SFGate.com: "Eugenics and the Nazis: the California Connection"

Press for Conversion! magazine, Issue # 53: "Facing the Corporate Roots of American Fascism," Bryan Sanders, Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade, March 2004

Rockefeller Foundation website

including

timeline

Hookworm and malaria research in Malaya, Java, and the Fiji Islands; report of Uncinariasis commission to the Orient, 1915–1917

The Rockefeller foundation, International health board. New York 1920 * {{Coord, 40.75083, -73.98333, display=title Rockefeller family Institutions founded by the Rockefeller family 1913 establishments in New York (state) Eugenics organizations Foundations based in the United States Educational foundations based in the United States

private foundation

A private foundation is a Tax exemption, tax-exempt organization that does not rely on broad public support and generally claims to serve humanitarian purposes.

Unlike a Foundation (nonprofit), charitable foundation, a private foundation does no ...

and philanthropic

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

medical research

Medical research (or biomedical research), also known as health research, refers to the process of using scientific methods with the aim to produce knowledge about human diseases, the prevention and treatment of illness, and the promotion of ...

and arts funding

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major thoroughfare in the borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan in New York City. The avenue runs south from 143rd Street (Manhattan), West 143rd Street in Harlem to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. The se ...

, New York City. The foundation was created by Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

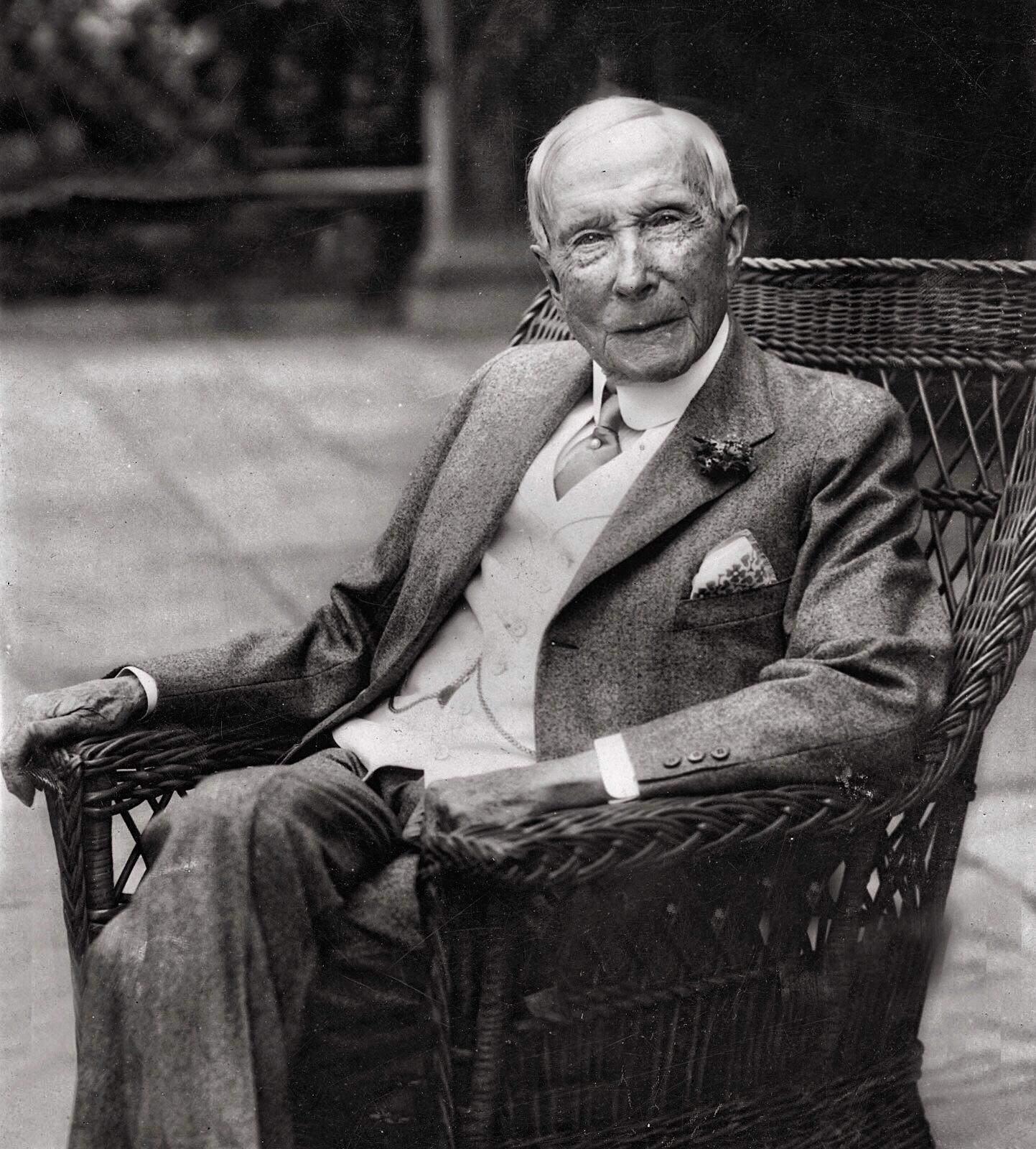

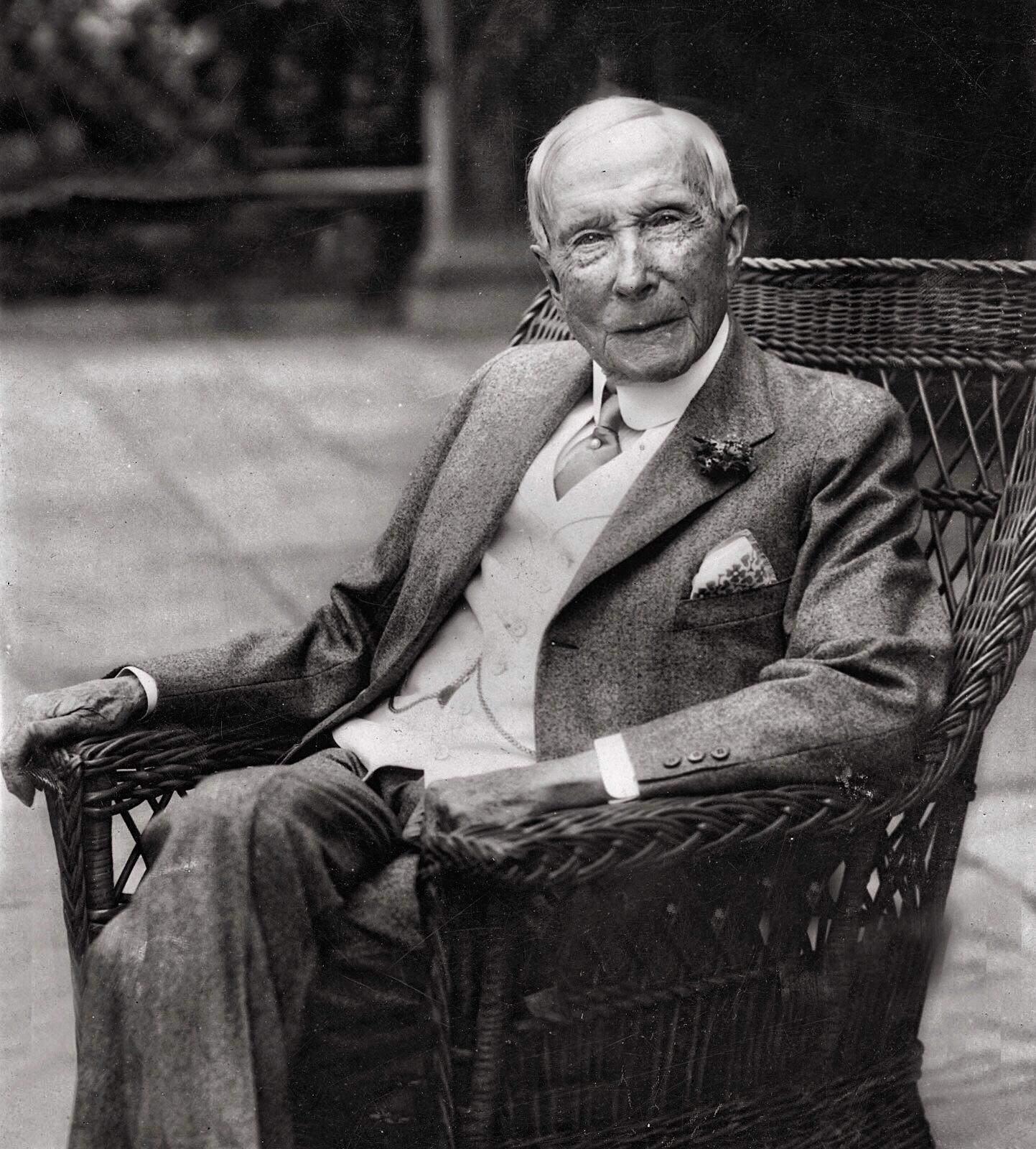

magnate John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

("Senior") and son " Junior", and their primary business advisor, Frederick Taylor Gates, on May 14, 1913, when its charter was granted by New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

. It is the second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America (after the Carnegie Corporation

The Carnegie Corporation of New York is a philanthropic fund established by Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to support education programs across the United States, and later the world.

Since its founding, the Carnegie Corporation has endowed or othe ...

) and ranks as the 30th largest foundation globally by endowment, with assets of over $6.3 billion in 2022.

The Rockefeller Foundation is legally independent from other Rockefeller entities, including the Rockefeller University

The Rockefeller University is a Private university, private Medical research, biomedical Research university, research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and pro ...

and Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a complex of 19 commerce, commercial buildings covering between 48th Street (Manhattan), 48th Street and 51st Street (Manhattan), 51st Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. The 14 original Art De ...

, and operates under the oversight of its own independent board of trustees, with its own resources and distinct mission. Since its inception, the foundation has donated billions of dollars to various causes, becoming the largest philanthropic enterprise in the world by the 1920s. The foundation has maintained an international reach since the 1930s and major influence on global non-governmental organization

A non-governmental organization (NGO) is an independent, typically nonprofit organization that operates outside government control, though it may get a significant percentage of its funding from government or corporate sources. NGOs often focus ...

s. The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

is modeled on the International Health Division of the foundation, which sent doctors abroad to study and treat human subjects. The National Science Foundation

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) is an Independent agencies of the United States government#Examples of independent agencies, independent agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that su ...

and National Institute of Health

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. It was founded in 1887 and is part of the United States Department of Health and Human Servic ...

are also modeled on the work funded by Rockefeller. It has also been a supporter of and influence on the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

.

In 2020, the foundation pledged that it would divest from fossil fuel

A fossil fuel is a flammable carbon compound- or hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the buried remains of prehistoric organisms (animals, plants or microplanktons), a process that occurs within geolog ...

, notable since the endowment was largely funded by Standard Oil. The foundation also has a controversial past, including support of eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

in the 1930s, as well as several scandals arising from their international field work. In 2021, the foundation's president committed to reckoning with their history, and to centering equity and inclusion.

History

John D. Rockefeller Sr. first conceived the idea of the foundation in 1901. In 1906, Rockefeller's business and philanthropic advisor, Frederick Taylor Gates, encouraged him toward "permanent corporate philanthropies for the good of Mankind" so that his heirs should not "dissipate their inheritances or become intoxicated with power." In 1909 Rockefeller signed over 73,000Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

shares worth $50 million, to his son, Gates and Harold Fowler McCormick

Harold Fowler McCormick (May 2, 1872 – October 16, 1941) was an American businessman. He was chairman of the board of International Harvester Company and a member of the McCormick family. Through his first wife, Edith Rockefeller, he became a ...

as the third inaugural trustee, in the first installment of a projected $100 million endowment.

The nascent foundation applied for a federal charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the ...

in the US Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

in 1910, with at one stage Junior even secretly meeting with President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

, through the aegis of Senator Nelson Aldrich

Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich (/Help:IPA/English, ˈɑldɹɪt͡ʃ/; November 6, 1841 – April 16, 1915) was a prominent American politician and a leader of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party in the United States Senate, where he r ...

, to hammer out concessions. However, because of the ongoing (1911) antitrust suit against Standard Oil at the time, along with deep suspicion in some quarters of undue Rockefeller influence on the spending of the endowment, the result was that Senior and Gates withdrew the bill from Congress in order to seek a state charter from New York.

On May 14, 1913, New York Governor

On May 14, 1913, New York Governor William Sulzer

William Sulzer (March 18, 1863 – November 6, 1941), nicknamed Plain Bill, was an American lawyer and politician. He was the 39th governor of New York serving for 10 months in 1913, and a long-serving U.S. representative from the same state. Su ...

approved a charter for the foundation with Junior becoming the first president. With its large-scale endowment, a large part of Senior's fortune was insulated from inheritance taxes. The first secretary of the foundation was Jerome Davis Greene, the former secretary of Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

, who wrote a "memorandum on principles and policies" for an early meeting of the trustees that established a rough framework for the foundation's work. It was initially located within the family office

A family office is a privately held company that handles investment management and wealth management for a wealthy family, generally one with at least $50–100 million in investable assets, with the goal being to effectively grow and transfer ...

at Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

's headquarters at 26 Broadway

26 Broadway, also known as the Standard Oil Building or Socony–Vacuum Building, is an office building adjacent to Bowling Green in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. The 31-story, structure was designed in the Renais ...

, later (in 1933) shifting to the GE Building

30 Rockefeller Plaza (officially the Comcast Building; formerly RCA Building and GE Building) is a skyscraper that forms the centerpiece of Rockefeller Center in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City, New York. Completed in 1933 ...

(then RCA

RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded in 1919 as the Radio Corporation of America. It was initially a patent pool, patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Westinghou ...

), along with the newly named family office, ''Room 5600'', at Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a complex of 19 commerce, commercial buildings covering between 48th Street (Manhattan), 48th Street and 51st Street (Manhattan), 51st Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. The 14 original Art De ...

; later it moved to the Time-Life Building

1271 Avenue of the Americas (formerly known as the Time & Life Building) is a 48-story skyscraper on Sixth Avenue (Avenue of the Americas), between 50th and 51st streets, in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Designed ...

in the center, before shifting to its current Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major thoroughfare in the borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan in New York City. The avenue runs south from 143rd Street (Manhattan), West 143rd Street in Harlem to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. The se ...

address.

In 1914, the trustees set up a new Department of Industrial Relations, inviting William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who was the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Liberal ...

to head it. He became a close and key advisor to Junior through the Ludlow Massacre, turning around his attitude to unions; however the foundation's involvement in IR was criticized for advancing the family's business interests. The foundation henceforth confined itself to funding responsible organizations involved in this and other controversial fields, which were beyond the control of the foundation itself.

Junior became the foundation chairman in 1917. Through the ''Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial'' (LSRM), established by Senior in 1918 and named after his wife, the Rockefeller fortune was for the first time directed to supporting research by social scientists. During its first few years of work, the LSRM awarded funds primarily to social workers, with its funding decisions guided primarily by Junior. In 1922, Beardsley Ruml was hired to direct the LSRM, and he most decisively shifted the focus of Rockefeller philanthropy into the

Junior became the foundation chairman in 1917. Through the ''Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial'' (LSRM), established by Senior in 1918 and named after his wife, the Rockefeller fortune was for the first time directed to supporting research by social scientists. During its first few years of work, the LSRM awarded funds primarily to social workers, with its funding decisions guided primarily by Junior. In 1922, Beardsley Ruml was hired to direct the LSRM, and he most decisively shifted the focus of Rockefeller philanthropy into the social science

Social science (often rendered in the plural as the social sciences) is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among members within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the ...

s, stimulating the founding of university research centers, and creating the Social Science Research Council

The Social Science Research Council (SSRC) is a US-based, independent, international nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing research in the social sciences and related disciplines. Established in Manhattan in 1923, it maintains a headqua ...

. In January 1929, LSRM funds were folded into the Rockefeller Foundation, in a major reorganization.

The Rockefeller family helped lead the foundation in its early years, but later limited itself to one or two representatives, to maintain the foundation's independence and avoid charges of undue family influence. These representatives have included the former president John D. Rockefeller III, and then his son John D. Rockefeller, IV, who gave up the trusteeship in 1981. In 1989, David Rockefeller

David Rockefeller (June 12, 1915 – March 20, 2017) was an American economist and investment banker who served as chairman and chief executive of Chase Bank, Chase Manhattan Corporation. He was the oldest living member of the third generation of ...

's daughter, Peggy Dulany, was appointed to the board for a five-year term. In October 2006, David Rockefeller Jr. joined the board of trustees, re-establishing the direct family link and becoming the sixth family member to serve on the board.

United States Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

under both Presidents John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

and Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

, served as chairman of the foundation.

Stock in the family's oil companies had been a major part of the foundation's assets, beginning with Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

and later with its corporate descendants, including ExxonMobil

Exxon Mobil Corporation ( ) is an American multinational List of oil exploration and production companies, oil and gas corporation headquartered in Spring, Texas, a suburb of Houston. Founded as the Successors of Standard Oil, largest direct s ...

. In December 2020, the foundation pledged to dump their fossil fuel holdings. With a $5 billion endowment, the Rockefeller Foundation was "the largest US foundation to embrace the rapidly growing divestment movement." CNN writer Matt Egan noted, "This divestment is especially symbolic because the Rockefeller Foundation was founded by oil money."

Public health

Public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the de ...

, health aid

In international relations, aid (also known as international aid, overseas aid, foreign aid, economic aid or foreign assistance) is – from the perspective of governments – a voluntary transfer of resources from one country to another. Th ...

, and medical research

Medical research (or biomedical research), also known as health research, refers to the process of using scientific methods with the aim to produce knowledge about human diseases, the prevention and treatment of illness, and the promotion of ...

are the most prominent areas of work of the foundation. On December 5, 1913, the Board made its first grant of $100,000 to the American Red Cross

The American National Red Cross is a Nonprofit organization, nonprofit Humanitarianism, humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. Clara Barton founded ...

to purchase property for its headquarters in Washington, D.C.

The foundation established the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and Harvard School of Public Health

The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health is the public health school at Harvard University, located in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. It was named after Hong Kong entrepreneur Chan Tseng-hsi in 2014 following a US$350 ...

, two of the first such institutions in the United States, and established the School of Hygiene at the University of Toronto in 1927, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a public university, public research university in Bloomsbury, central London, and a constituent college, member institution of the University of London that specialises in public hea ...

in the United Kingdom. they spent more than $25 million in developing other public health schools in the US and in 21 foreign countries. In 1913, it also began a 20-year support program of the ''Bureau of Social Hygiene'', whose mission was research and education on birth control, maternal health and sex education. In 1914, the foundation set up the China Medical Board, which established the first public health university in China, the Peking Union Medical College

Peking Union Medical College, also as Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, is a national public medical sciences research institution in Dongcheng, Beijing, Dongcheng, Beijing, China. Originally founded in 1906, it is affiliated with the Nationa ...

, in 1921; this was subsequently nationalized when the Communists took over the country in 1949. In the same year it began a program of international fellowships to train scholars at many of the world's universities at the post-doctoral level. The Foundation also maintained a close relationship with Rockefeller University

The Rockefeller University is a Private university, private Medical research, biomedical Research university, research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and pro ...

(also known as the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research) with many faculty holding overlapping positions between the institutions.

The Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of

The Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm

Hookworms are Gastrointestinal tract, intestinal, Hematophagy, blood-feeding, parasitic Nematode, roundworms that cause types of infection known as helminthiases. Hookworm infection is found in many parts of the world, and is common in areas with ...

Disease was a Rockefeller-funded campaign from 1909 to 1914 to study and treat hookworm disease in 11 Southern states. Hookworm was known as the "germ of laziness". In 1913, the foundation expanded its work with the Sanitary Commission abroad and set up the International Health Division (also known as International Health Board), which began the foundation's first international public health activities. The International Health Division conducted campaigns in public health and sanitation against malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

, yellow fever, and hookworm in areas throughout Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean including Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

, Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, and Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

, totaling fifty-two countries on six continents and twenty-nine islands. The first director was Wickliffe Rose

Wickliffe Rose (November 19, 1862 in Saulsbury, Tennessee – September 5, 1931 in British Columbia) was the first director of the International Health Board of the Rockefeller Foundation and won the Public Welfare Medal in 1931.

Rose became ...

, followed by F.F. Russell in 1923, Wilbur Sawyer in 1935, and George Strode in 1944. A number of notable physicians and field scientists worked on the international campaigns, including Lewis Hackett, Hideyo Noguchi

, also known as , was a prominent Japanese bacteriologist at the Rockefeller University, Rockefeller Institute known for his work on syphilis, serology, immunology, and contributing to the long term understanding of neurosyphilis.

Before the Ro ...

, Juan Guiteras, George C. Payne, Livingston Farrand

Livingston Farrand (June 14, 1867 – November 8, 1939) was an American physician, anthropologist, psychologist, public health advocate and academic administrator. He was president of Cornell University and the University of Colorado.

Earl ...

, Cornelius P. Rhoads, and William Bosworth Castle. In 1936, The Rockefeller Foundation received one of the first awarded Walter Reed Medals from The American Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene to recognize its study and control of Yellow Fever. The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

, seen as a successor to the IHD, was formed in 1948, and the IHD was subsumed by the larger Rockefeller Foundation in 1951, discontinuing its overseas work.

While the Rockefeller doctors working in tropical locales such as Mexico emphasized scientific neutrality, they had political and economic aims to promote the value of public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the de ...

to improve American relations with the host country. Although they claimed the banner of public health and humanitarian medicine, they often engaged with politics and business interests. Rhoads was involved in a racism whitewashing scandal in the 1930s during which he joked about injecting cancer cells into Puerto Rican patients, inspiring Puerto Rican nationalist and anti-colonialist leader Pedro Albizu Campos

Pedro Albizu Campos (June 29, 1893Luis Fortuño Janeiro. ''Album Histórico de Ponce (1692–1963).'' p. 290. Ponce, Puerto Rico: Imprenta Fortuño. 1963. – April 21, 1965) was a Puerto Rican attorney and politician, and a leading figure in ...

. Noguchi was also involved in an unethical human experimentation

Unethical human experimentation is human experimentation that violates the principles of medical ethics. Such practices have included denying patients the right to informed consent, using pseudoscientific frameworks such as race science, and tort ...

scandal. Susan Lederer, Elizabeth Fee

Elizabeth Fee (December 11, 1946 – October 17, 2018), also known as Liz Fee, was a historian of science, medicine and health. She was the Chief of the United States National Library of Medicine History of Medicine Division.

Early life and edu ...

, and Jay Katz

Jacob "Jay" Katz (October 20, 1922 – November 17, 2008) was an American physician and Yale Law School professor whose career was devoted to addressing complex issues of medical ethics and other ethical problems involving the overlaps of eth ...

are among the modern scholars who have researched this period. Researchers with the foundation including Noguchi developed the vaccine to prevent yellow fever. Rhoads later became a significant cancer researcher and director of Memorial Sloan-Kettering, though his eponymous award for oncological excellence was renamed after the scandal reemerged. During the late-1920s, the Rockefeller Foundation created the Medical Sciences Division, which emerged from the former Division of Medical Education. The division was led by Richard M. Pearce until his death in 1930, to which Alan Gregg succeeded him until 1945. During this period, the Division of Medical Sciences made contributions to research across several fields of psychiatry. In 1935 the foundation granted $100000 to the Institute for Psychoanalysis in Chicago. This grant was renewed in 1938, with payments extending into the early-1940s. This division funded women's contraception and the human reproductive system in general, but also was involved in funding controversial

During the late-1920s, the Rockefeller Foundation created the Medical Sciences Division, which emerged from the former Division of Medical Education. The division was led by Richard M. Pearce until his death in 1930, to which Alan Gregg succeeded him until 1945. During this period, the Division of Medical Sciences made contributions to research across several fields of psychiatry. In 1935 the foundation granted $100000 to the Institute for Psychoanalysis in Chicago. This grant was renewed in 1938, with payments extending into the early-1940s. This division funded women's contraception and the human reproductive system in general, but also was involved in funding controversial eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

research. Other funding went into endocrinology

Endocrinology (from ''endocrine system, endocrine'' + ''wikt:-logy#Suffix, -ology'') is a branch of biology and medicine dealing with the endocrine system, its diseases, and its specific secretions known as hormones. It is also concerned with the ...

departments in American universities, human heredity, mammalian biology, human physiology and anatomy, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, and the studies of human sexual behavior by Alfred Kinsey

Alfred Charles Kinsey (; June 23, 1894 – August 25, 1956) was an American sexologist, biologist, and professor of entomology and zoology who, in 1947, founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, now known as the Kinsey Insti ...

.

In the interwar years, the foundation funded public health, nursing, and social work in Eastern and Central Europe.

In 1950, the foundation expanded their international program of virus research, establishing field laboratories in Poona

Pune ( ; , ISO 15919, ISO: ), previously spelled in English as Poona (List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1978), is a city in the state of Maharashtra in the Deccan Plateau, Deccan plateau in Western ...

, India, Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger, more populous island of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, the country. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is the southernmost island in ...

, Belém

Belém (; Portuguese for Bethlehem; initially called Nossa Senhora de Belém do Grão-Pará, in English Our Lady of Bethlehem of Great Pará), often called Belém of Pará, is the capital and largest city of the state of Pará in the north of B ...

, Brazil, Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

, South Africa, Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

, Egypt, Ibadan

Ibadan (, ; ) is the Capital city, capital and most populous city of Oyo State, in Nigeria. It is the List of Nigerian cities by population, third-largest city by population in Nigeria after Lagos and Kano (city), Kano, with a total populatio ...

, Nigeria, and Cali

Santiago de Cali (), or Cali, is the capital of the Valle del Cauca department, and the most populous city in southwest Colombia, with 2,280,522 residents estimate by National Administrative Department of Statistics, DANE in 2023. The city span ...

, Colombia, among others. The foundation funded research into the identification of human viruses, techniques for virus identification, and arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

-borne viruses.

Bristol-Myers Squibb

The Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, doing business as Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), is an American multinational pharmaceutical company. Headquartered in Princeton, New Jersey, BMS is one of the world's largest pharmaceutical companies and consist ...

, Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

and the Rockefeller Foundation are currently the subject of a $1 billion lawsuit from Guatemala

Guatemala, officially the Republic of Guatemala, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico, to the northeast by Belize, to the east by Honduras, and to the southeast by El Salvador. It is hydrologically b ...

for "roles in a 1940s U.S. government experiment that infected hundreds of Guatemalans with syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

". A previous suit against the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

government was dismissed in 2011 for the Guatemala syphilis experiments

The Guatemala syphilis experiments were United States-led human experiments conducted in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948. The experiments were led by physician John Charles Cutler, who also participated in the late stages of the Tuskegee syphilis expe ...

when a judge determined that the U.S. government could not be held liable for actions committed outside of the U.S.

An experiment was conducted by Vanderbilt University in the 1940s where they gave 800 pregnant women radioactive iron, 751 of which were pills, without their consent. In a 1969 article published in the ''American Journal of Epidemiology

The American Journal of Epidemiology (''AJE'') is a peer-reviewed journal for empirical research findings, opinion pieces, and methodological developments in the field of epidemiological research. The current editor-in-chief is Enrique Schisterma ...

'', it was estimated that three children had died from the experiment.

Eugenics and World War II

John D. Rockefeller Jr. was an outspoken supporter of eugenics. Even as late as 1951, John D. Rockefeller III andJohn Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American politician, lawyer, and diplomat who served as United States secretary of state under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 until his resignation in 1959. A member of the ...

, who was chairman of the foundation at the time, established the Population Council

The Population Council is an international, nonprofit, non-governmental organization. The Council conducts research in biomedicine, social science, and public health and helps build research capacities in developing countries. One-third of its re ...

to advance family planning

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a person wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which they wish to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marit ...

, birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

, and population control

Population control is the practice of artificially maintaining the size of any population. It simply refers to the act of limiting the size of an animal population so that it remains manageable, as opposed to the act of protecting a species from ...

, and goals of the eugenics movement.

The Rockefeller Foundation, along with the Carnegie Institution

The Carnegie Institution for Science, also known as Carnegie Science and the Carnegie Institution of Washington, is an organization established to fund and perform scientific research in the United States. This institution is headquartered in Wa ...

, was the primary financier for the Eugenics Record Office

The Eugenics Record Office (ERO), located in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, United States, was a research institute that gathered biological and social information about the American population, serving as a center for eugenics and human heredity ...

, until 1939. The foundation also provided grants to Margaret Sanger

Margaret Sanger ( Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966) was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. She opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, founded Planned Parenthood, and was instr ...

and Alexis Carrel

Alexis Carrel (; 28 June 1873 – 5 November 1944) was a French surgeon and biologist who spent most of his scientific career in the United States. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1912 for pioneering vascular suturi ...

, who supported birth control, compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, refers to any government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually do ...

and eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

. Sanger went to Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

in 1922 and influenced the birth control movement there.

By 1926, Rockefeller had donated over $400,000, which would be almost $4 million adjusted for inflation in 2003, to hundreds of German researchers, including Ernst Rüdin and Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer

Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer (; 16 July 1896 – 8 August 1969) was a German-Dutch human biologist and geneticist, who was the Professor of Human Genetics at the University of Münster until he retired in 1965. A member of the Dutch noble Vers ...

, through funding the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics

The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics was a research institute founded in 1927 in Berlin, Germany. The Rockefeller Foundation partially funded the actual building of the Institute and helped keep the Institut ...

, (also known as the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research

The Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg, Germany, is a facility of the Max Planck Society for basic medical research. Since its foundation, six Nobel Prize laureates worked at the Institute: Otto Fritz Meyerhof (Physiology), ...

) which conducted eugenics experiments in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and influenced the development of Nazi racial scientific ideology. Rockefeller spent almost $3 million between 1925 and 1935, and also funded other German eugenicists, Herman Poll, Alfred Grotjahn, Eugen Fischer

Eugen Fischer (5 July 1874 – 9 July 1967) was a German professor of medicine, anthropology, and eugenics, and a member of the Nazi Party. He served as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, ...

, and Hans Nachsteim, continuing even after Hitler's ascent to power in 1933; Rüdin's work influenced compulsory sterilisation in Nazi Germany. Josef Mengele

Josef Mengele (; 16 March 19117 February 1979) was a Nazi German (SS) officer and physician during World War II at the Russian front and then at Auschwitz during the Holocaust, often dubbed the "Angel of Death" (). He performed Nazi hum ...

worked as an assistant in Verschuer's lab, though Rockefeller executives did not know of Mengele and stopped funding that specific research before World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

started in 1939.

The Rockefeller Foundation continued funding German eugenics research even after it was clear that it was being used to rationalize discrimination against Jewish people

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

and other groups, after the Nuremberg laws

The Nuremberg Laws (, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of the Nazi Party. The two laws were the Law ...

in 1935

Events

January

* January 7 – Italian premier Benito Mussolini and French Foreign Minister Pierre Laval conclude an agreement, in which each power agrees not to oppose the other's colonial claims.

* January 12 – Amelia Earhart ...

. In 1936, Rockefeller fulfilled pledges of $655,000 to Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, even though several distinguished Jewish scientists had been dropped from the institute at the time. The Rockefeller Foundation did not alert the world about the racist implications of Nazi ideology

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was freque ...

, but furthered and funded eugenic research through the 1930s. Even into the 1950s, Rockefeller continued to provide some funding for research borne out of German eugenics.

The foundation also funded the relocation of scholars threatened by the Nazis to America in the 1930s, known as the Refugee Scholar Program and the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars. Some of the notable figures relocated or saved, among a total of 303 scholars, were Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

, Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss ( ; ; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009) was a Belgian-born French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He held the chair o ...

and Leó Szilárd

Leo Szilard (; ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-born physicist, biologist and inventor who made numerous important discoveries in nuclear physics and the biological sciences. He conceived the nuclear ...

. The foundation helped The New School

The New School is a Private university, private research university in New York City. It was founded in 1919 as The New School for Social Research with an original mission dedicated to academic freedom and intellectual inquiry and a home for p ...

provide a haven for scholars threatened by the Nazis.

After World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

the foundation sent a team to West Germany to investigate how it could become involved in reconstructing the country. They focused on restoring democracy, especially regarding education and scientific research, with the long-term goal of reintegrating Germany into the Western world.

The foundation also supported the early initiatives of Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (May 27, 1923 – November 29, 2023) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 56th United States secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and the 7th National Security Advisor (United States), natio ...

, such as his directorship of Harvard's ''International Seminars'' (funded as well by the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

) and the early foreign policy magazine ''Confluence'', both established by him while he was still a graduate student.

In 2021, Rajiv J. Shah, president of the Rockefeller Foundation, released a statement condemning eugenics and supporting the anti-eugenics movement. He stated that

" ..we commend the Anti-Eugenics Project for their essential work to understand ..the harmful legacies of eugenicist ideologies. ..examine the role that philanthropies played in developing and perpetuating eugenics policies and practices. The Rockefeller Foundation is currently reckoning with our own history in relation to eugenics. This requires uncovering the facts and confronting uncomfortable truths, ..The Rockefeller Foundation is putting equity and inclusion at the center of all our work: ..confronting the hateful legacies of the past ..we understand that the work we engage in today does not absolve us of yesterday's mistakes. ..

Development of the United Nations

Although the United States never joined theLeague of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

, the Rockefeller Foundation was involved, and by the 1930s the foundations had changed the League from a "Parliament of Nations" to a modern think tank that used specialized expertise to provide in-depth impartial analysis of international issues. After the war, the foundation was involved in the establishment of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

.

Arts and philanthropy

Senate House (University of London)

Senate House is the administrative centre of the University of London, situated in the heart of Bloomsbury, London, immediately to the north of the British Museum.

The Art Deco building was constructed between 1932 and 1937 as the first phase ...

was built on donation from Rockefeller Foundation in 1926 and a foundation stone laid by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

George was born during the reign of his pa ...

in 1933. It is the headquarters of the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a collegiate university, federal Public university, public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The ...

since 1937.

In the arts, the Rockefeller Foundation has supported the Stratford Shakespeare Festival

The Stratford Festival is a Repertory theatre, repertory theatre organization that operates from April to October in the city of Stratford, Ontario, Canada. Founded by local journalist Tom Patterson (theatre producer), Tom Patterson in 1952, th ...

in Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

, Canada, and the American Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut

Stratford is a New England town, town in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. It is situated on Long Island Sound at the mouth of the Housatonic River. The town is part of the Greater Bridgeport Planning Region, Connecticut, Greater Bri ...

, Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., Karamu House

Karamu House in the Fairfax neighborhood on the east side of Cleveland, Ohio, United States, is the oldest producing Black Theatre in the United States opening in 1915. Many of Langston Hughes's plays were developed and premiered at the theate ...

in Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

, and Lincoln Center

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts (also simply known as Lincoln Center) is a complex of buildings in the Lincoln Square neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It has thirty indoor and outdoor facilities and is host to 5 ...

in New York. The foundation underwrote Spike Lee

Shelton Jackson "Spike" Lee (born March 20, 1957) is an American film director, producer, screenwriter, actor, and author. His work has continually explored race relations, issues within the black community, the role of media in contemporary ...

's documentary on New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, ''When the Levees Broke

''When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts'' is a 2006 documentary film directed by Spike Lee about the devastation of New Orleans, Louisiana following the failure of the levees during Hurricane Katrina. It was filmed in late August an ...

''. The film has been used as the basis for a curriculum on poverty, developed by the Teachers College at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

for their students.

The Cultural Innovation Fund is a pilot grant program that is overseen by the Lincoln Center

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts (also simply known as Lincoln Center) is a complex of buildings in the Lincoln Square neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It has thirty indoor and outdoor facilities and is host to 5 ...

. The grants are to be used towards art and cultural opportunities in the underserved areas of Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

and the South Bronx

The South Bronx is an area of the Boroughs of New York City, New York City borough of the Bronx. The area comprises neighborhoods in the southern part of the Bronx, such as Concourse, Bronx, Concourse, Mott Haven, Bronx, Mott Haven, Melrose, B ...

with three overarching goals.

The Rockefeller Foundation supported the art scene in Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

in 1948 and a literacy project with UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

.

Rusk was involved with funding the humanities and the social sciences during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

period, including study of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

In July 2022, the Rockefeller Foundation granted $1m to the Wikimedia Foundation

The Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. (WMF) is an American 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization headquartered in San Francisco, California, and registered there as foundation (United States law), a charitable foundation. It is the host of Wikipedia, th ...

.

Bellagio Center

The foundation also owns and operates the Bellagio Center in

The foundation also owns and operates the Bellagio Center in Bellagio, Italy

Bellagio (; ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Como in the Lombardy region of Italy. It is situated on Lake Como, known also by its Latin name ''Lario'', where the lake's two southern arms branch, creating the ''Triangolo larian ...

. The center has several buildings, spread across a property, on the peninsula between lakes Como

Como (, ; , or ; ) is a city and (municipality) in Lombardy, Italy. It is the administrative capital of the Province of Como. Nestled at the southwestern branch of the picturesque Lake Como, the city is a renowned tourist destination, ce ...

and Lecco

Lecco (, , ; ) is a city of approximately 47,000 inhabitants in Lombardy, Northern Italy, north of Milan. It lies at the end of the south-eastern branch of Lake Como (the branch is named ''Branch of Lecco'' / ''Ramo di Lecco''). The Bergamasqu ...

in Northern Italy

Northern Italy (, , ) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. The Italian National Institute of Statistics defines the region as encompassing the four Northwest Italy, northwestern Regions of Italy, regions of Piedmo ...

. The center is sometimes referred to as the " Villa Serbelloni", the property bequeathed to the foundation in 1959 under the presidency of Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States secretary of state from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving secretary of state after Cordell Hull from the ...

(who was later to become U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

Kennedy

Kennedy may refer to:

People

* Kennedy (surname), including any of several people with that surname

** Kennedy family, a prominent American political family that includes:

*** Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. (1888–1969), American businessman, investor, ...

's secretary of state).The Bellagio Center operates both a conference center and a residency program. Numerous Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

, Pulitzer winners, National Book Award

The National Book Awards (NBA) are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors. ...

recipients, Prince Mahidol Award

The Prince Mahidol Award () is an annual award for outstanding achievements in medicine and public health worldwide. The award is given by the Prince Mahidol Award Foundation, which was founded by the Thai Royal Family in 1992.

Prince Mahidol ...

winners, and MacArthur fellows

The MacArthur Fellows Program, also known as the MacArthur Fellowship and colloquially called the "Genius Grant", is a prize awarded annually by the MacArthur Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to typically between 20 and ...

, as well as several acting and former heads of state and government, have been in residence at Bellagio.

Agriculture

Agriculture was introduced to the Natural Sciences division of the foundation in the major reorganization of 1928. In 1941, the foundation gave a small grant toMexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

for maize research, in collaboration with the then new president, Manuel Ávila Camacho

Manuel Ávila Camacho (; 24 April 1897 – 13 October 1955) was a Mexican politician and military leader who served as the president of Mexico from 1940 to 1946. Despite participating in the Mexican Revolution and achieving a high rank, he cam ...

. This was done after the intervention of Vice President Henry Wallace and the involvement of Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

; the primary intention being to stabilise the Mexican Government and derail any possible communist infiltration, in order to protect the Rockefeller family's investments.The story of the Foundation and the Green Revolution – see Mark Dowie, ''American Foundations: An Investigative History'', Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2001, (pp. 105–140)

By 1943, this program, under the foundation's ''Mexican Agriculture Project'', had proved such a success with the science of corn propagation and general principles of agronomy

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants by agriculture for food, fuel, fiber, chemicals, recreation, or land conservation. Agronomy has come to include research of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and ...

that it was exported to other Latin American countries; in 1956, the program was then taken to India; again with the geopolitical imperative of providing an antidote to communism. It wasn't until 1959 that senior foundation officials succeeded in getting the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a $25,000 (about $550,000 in 2023) gift from Edsel Ford. ...

(and later USAID

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an agency of the United States government that has been responsible for administering civilian United States foreign aid, foreign aid and development assistance.

Established in 19 ...

, and later still, the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

) to sign on to the major philanthropic project, known now to the world as the Green Revolution

The Green Revolution, or the Third Agricultural Revolution, was a period during which technology transfer initiatives resulted in a significant increase in crop yields. These changes in agriculture initially emerged in Developed country , devel ...

. It was originally conceived in 1943 as CIMMYT

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (known – even in English – by its Spanish acronym CIMMYT for ''Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo'') is a non-profit research-for-development organization that develops ...

, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (known – even in English – by its Spanish acronym CIMMYT for ''Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo'') is a non-profit research-for-development organization that develops ...

in Mexico. It also provided significant funding for the International Rice Research Institute

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) is an international agricultural research and training organization with its headquarters in Los Baños, Laguna, in the Philippines, and offices in seventeen countries. IRRI is known for its w ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

. Part of the original program, the funding of the IRRI was later taken over by the Ford Foundation. The International Rice Research Institute

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) is an international agricultural research and training organization with its headquarters in Los Baños, Laguna, in the Philippines, and offices in seventeen countries. IRRI is known for its w ...

and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (known – even in English – by its Spanish acronym CIMMYT for ''Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo'') is a non-profit research-for-development organization that develops ...

are part of a consortium of agricultural research organizations known as CGIAR

CGIAR (formerly the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research) is a global partnership that unites international organizations engaged in research about food security. CGIAR research aims to reduce rural poverty, increase food ...

.

Costing around $600 million, over 50 years, the revolution brought new farming technology, increased productivity, expanded crop yields and mass fertilization to many countries throughout the world. Later it funded over $100 million of plant biotechnology

Biotechnology is a multidisciplinary field that involves the integration of natural sciences and Engineering Science, engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms and parts thereof for products and services. Specialists ...

research and trained over four hundred scientists from Asia, Africa and Latin America. It also invested in the production of transgenic

A transgene is a gene that has been transferred naturally, or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques, from one organism to another. The introduction of a transgene, in a process known as transgenesis, has the potential to change the ...

crops, including rice and maize. In 1999, the then president Gordon Conway addressed the Monsanto Company

The Monsanto Company () was an American agrochemical and agricultural biotechnology corporation founded in 1901 and headquartered in Creve Coeur, Missouri. Monsanto's best-known product is Roundup, a glyphosate-based herbicide, developed in ...

board of directors, warning of the possible social and environmental dangers of this biotechnology, and requesting them to disavow the use of so-called terminator genes; the company later complied.

In the 1990s, the foundation shifted its agriculture work and emphasis to Africa; in 2006, it joined with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

The Gates Foundation is an American private foundation founded by Bill Gates and Melinda French Gates. Based in Seattle, Washington, it was launched in 2000 and is reported to be the third largest charitable foundation in the world, holding $ ...

in a $150 million effort to fight hunger in the continent through improved agricultural productivity. In an interview marking the 100 year anniversary of the Rockefeller Foundation, Judith Rodin

Judith Rodin (born Judith Seitz, September 9, 1944) is an American research psychologist, executive, university president, and global thought-leader. She served as the 12th president of the Rockefeller Foundation from 2005 to 2017. From 1994 to 2 ...

explained to This Is Africa that Rockefeller has been involved in Africa since their beginning in three main areas – health, agriculture and education, though agriculture has been and continues to be their largest investment in Africa.

Urban development

A total of 100 cities across six continents were part of the 100 Resilient Cities program funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. In January 2016, the United States

A total of 100 cities across six continents were part of the 100 Resilient Cities program funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. In January 2016, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government. It administers federal housing and urban development laws. It is headed by the secretary of housing and u ...

announced winners of its National Disaster Resilience Competition (NDRC), awarding three 100RC member cities – New York, NY

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on New York Harbor, one of the world's largest natural harb ...

; Norfolk, VA

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. It had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in Virginia, third-most populous city ...

; and New Orleans, LA

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

– with more than $437 million in disaster resilience funding. The grant was the largest ever received by the city of Norfolk.

In April 2019, it was announced that the foundation would no longer be funding the 100 Resilient Cities program as a whole. Some elements of the initiative's work, most prominently the funding of several cities' Chief Resilience Officer roles, continues to be managed and funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, while other aspects of the program continue in the form of two independent organizations, Resilient Cities Catalyst (RCC) and the Global Resilient Cities Network (GRCN), founded by former 100RC leadership and staff.

People affiliated with the foundation

Board members and trustees

:On January 5, 2017, the board of trustees announced the selection of Rajiv Shah to serve as the 13th president of the foundation. Shah became the youngest person, at 43, and first Indian-American to serve as president of the foundation. He assumed the position March 1, succeedingJudith Rodin