Robert Leckie (aviator) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Air Marshal Robert Leckie, (16 April 1890 – 31 March 1975) was an

Leckie's first success came on 14 May 1917, as pilot of Curtiss Model H-12 'Large America' No. 8666, under the command of Flight Lieutenant Christopher John Galpin. The aircraft left Great Yarmouth on patrol at 03.30 a.m. in poor weather with heavy rain and low cloud. The weather cleared as she approached the

Leckie's first success came on 14 May 1917, as pilot of Curtiss Model H-12 'Large America' No. 8666, under the command of Flight Lieutenant Christopher John Galpin. The aircraft left Great Yarmouth on patrol at 03.30 a.m. in poor weather with heavy rain and low cloud. The weather cleared as she approached the  On 1 April 1918, the Royal Naval Air Service was merged with the Army's

On 1 April 1918, the Royal Naval Air Service was merged with the Army's

Canada's 25 Most Renowned Military Leaders

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Leckie, Robert 1890 births 1975 deaths Royal Canadian Air Force officers Military personnel from Glasgow Scottish airmen Scottish emigrants to Canada Canadian Expeditionary Force officers Royal Naval Air Service aviators Canadian World War I pilots Canadian military personnel of World War II Royal Air Force air marshals of World War II Royal Canadian Air Force air marshals of World War II Canadian Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Canadian Companions of the Order of the Bath Canadian recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Grand Officers of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Grand Officers of the Order of the White Lion Graduates of the Royal Naval College, Greenwich Grand Crosses of the Order of Polonia Restituta Commanders of the Legion of Merit Recipients of the King Haakon VII Freedom Cross Canadian recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Presidents of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society Canadian people of Scottish descent

air officer

An air officer is an air force officer of the rank of air commodore or higher. Such officers may be termed "officers of air rank". While the term originated in the Royal Air Force, air officers are also to be found in many Commonwealth of Natio ...

in the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

and later in the Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; ) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environmental commands within the unified Can ...

, and served as Chief of the Air Staff of the Royal Canadian Air Force from 1944 to 1947. He initially served in the Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty (United Kingdom), Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British ...

during the First World War, where he became known as one of "the Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp. 155â ...

killers from Canada", after shooting down two airships. During the inter-war period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

he served as a Royal Air Force squadron and station commander, eventually becoming the RAF's Director of Training in 1935, and was Air Officer Commanding RAF Mediterranean from 1938 until after the beginning of the Second World War. In 1940 he returned to Canada where he was primarily responsible for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), often referred to as simply "The Plan", was a large-scale multinational military aircrew training program created by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand during the Second Wo ...

, transferring to the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1942.

Early life and background

Leckie was born inGlasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, Scotland, where his father and grandfather were weavers

Weaver or Weavers may refer to:

Activities

* A person who engages in weaving fabric

Animals

* Various birds of the family Ploceidae

* Crevice weaver spider family

* Orb-weaver spider family

* Weever (or weever-fish)

Arts and entertainment

...

. In 1909 his family emigrated to Canada, where he worked for his uncle John Leckie while living in West Toronto

West Toronto was a federal electoral district represented in the House of Commons of Canada from 1867 to 1904. It was located in the city of Toronto, in the province of Ontario. The district was created by the British North America Act 1867 a ...

.

First World War

Leckie was initially commissioned into the 1st Central Ontario Regiment, and in late 1915 paidCan$

The Canadian dollar (currency symbol, symbol: $; ISO 4217, code: CAD; ) is the currency of Canada. It is abbreviated with the dollar sign $. There is no standard disambiguating form, but the abbreviations Can$, CA$ and C$ are frequently used f ...

600 to begin flying training at the Curtiss Flying School

A Curtiss Jenny on a training flight

Curtiss Flying School at North Island, San Diego, California in 1911

The Curtiss Flying School was started by Glenn Curtiss to compete against the Wright Flying School of the Wright brothers. The first exam ...

on Toronto Island

The Toronto Islands are a chain of 15 small islands in Lake Ontario, south of mainland Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Comprising the only group of islands in the western part of Lake Ontario, the Toronto Islands are located just offshore from the ...

. However, he had completed only three hours of training in the Curtiss Model F flying boat

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy.

Though ...

at Hanlan's Point, when the school was forced to close for the winter. At the urging of Sir Charles Kingsmill, the Chief of the Naval Staff of the Royal Canadian Navy, the Royal Navy agreed to accept half of the class, and Leckie was sent to England. On 6 December 1915, he was commissioned as a probationary temporary flight sub-lieutenant in the Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty (United Kingdom), Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British ...

, and posted to Royal Navy Air Station Chingford

Chingford is a suburban town in east London, England, within the London Borough of Waltham Forest. The centre of Chingford is north-east of Charing Cross, with Waltham Abbey to the north, Woodford Green and Buckhurst Hill to the east, Walt ...

, for training. On 10 May 1916, having accumulated 33 hours and 3 minutes flying time, he was granted Royal Aero Club

The Royal Aero Club (RAeC) is the national co-ordinating body for air sport in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1901 as the Aero Club of Great Britain, being granted the title of the "Royal Aero Club" in 1910.

History

The Aero Club was foun ...

Aviator's Certificate No. 2923, and was then sent to RNAS Felixstowe for further training in flying boats. He was confirmed in his rank of flight sub-lieutenant in June, and in August was posted to RNAS Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth ( ), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside resort, seaside town which gives its name to the wider Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. Its fishing industry, m ...

to fly patrols over the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

.

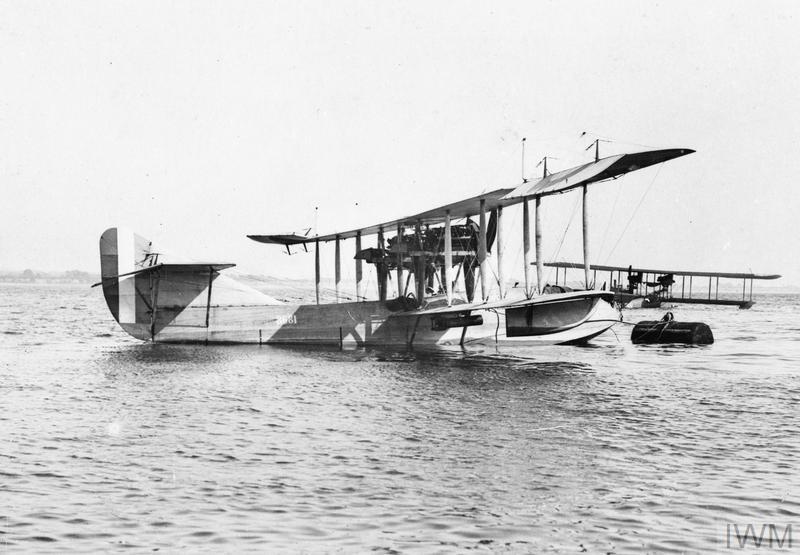

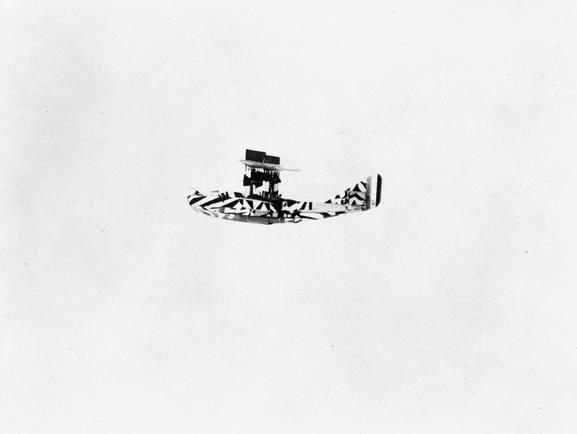

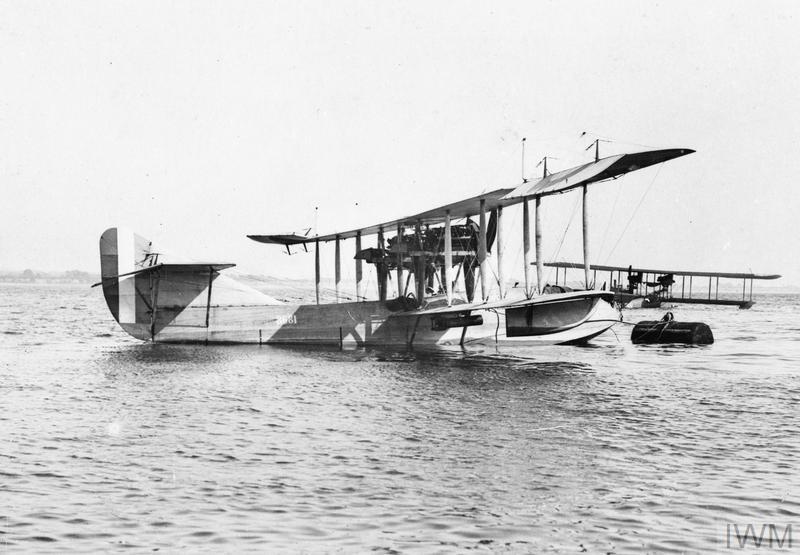

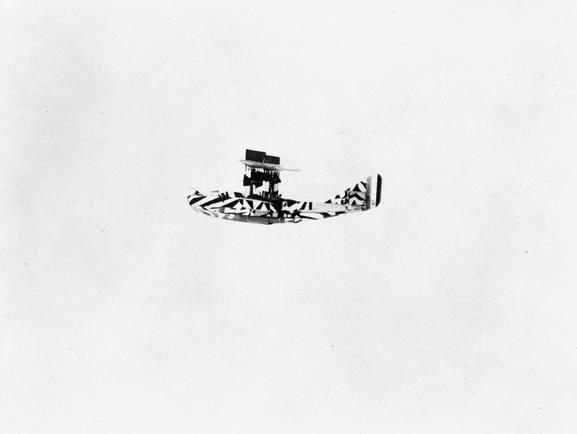

Leckie's first success came on 14 May 1917, as pilot of Curtiss Model H-12 'Large America' No. 8666, under the command of Flight Lieutenant Christopher John Galpin. The aircraft left Great Yarmouth on patrol at 03.30 a.m. in poor weather with heavy rain and low cloud. The weather cleared as she approached the

Leckie's first success came on 14 May 1917, as pilot of Curtiss Model H-12 'Large America' No. 8666, under the command of Flight Lieutenant Christopher John Galpin. The aircraft left Great Yarmouth on patrol at 03.30 a.m. in poor weather with heavy rain and low cloud. The weather cleared as she approached the Texel

Texel (; Texels dialect: ) is a municipality and an island with a population of 13,643 in North Holland, Netherlands. It is the largest and most populated island of the West Frisian Islands in the Wadden Sea. The island is situated north of Den ...

, and at 4:45 a.m. she spotted the Terschelling

Terschelling (; ; Terschelling dialect: ''Schylge'') is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and an island in the northern Netherlands, one of the West Frisian Islands. It is situated between the islands of Vlieland and Ameland.

...

Light Vessel, and a few minutes later Zeppelin ''L 22'' about 10–15 miles away. The Curtiss increased speed and gained height, and Leckie took over the controls as Galpin manned the twin Lewis guns mounted in the bow. The Curtiss managed to approach to within half a mile before she was spotted, and the Zeppelin attempted to evade, but by then it was too late. The aircraft dived down alongside and Galpin fired an entire drum of incendiary bullets at a range of about 50 yards. The ''L 22'' rapidly caught fire, and crashed into the sea. The Curtiss returned to Great Yarmouth by 7:50 a.m., and they found only two bullet holes, in the left upper wing and the hull amidships, where the Germans had returned fire. On 22 June, for his part in downing the ''L 22'', Leckie was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, while Galpin received the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

. On 30 June Leckie was promoted to flight lieutenant.

Another memorable patrol began for Leckie at 10.35 a.m. on 5 September 1917, again flying Curtiss H-12 No. 8666 from Great Yarmouth, under Squadron Commander Vincent Nicholl. They were accompanied by a de Havilland DH.4 biplane, and were again heading for Terschelling. However, they were only part-way to their destination when they unexpectedly encountered the Zeppelins ''L 44'' and ''L 46'' accompanied by support ships. The British aircraft were hit by enemy fire, but pressed their attack on the ''L 44''. Nicholl noted several hits on the Zeppelin from his guns, but it did not catch fire. Leckie then turned the aircraft to attack the ''L 46'', but it had turned rapidly away and was out of range, as was the ''L 44'' by the time he turned back. Both British aircraft had been hit, and the DH.4's engine soon failed. The Curtiss had also been hit in one engine and one wing was badly damaged. The DH.4 was forced to ditch into the sea, and Nicholl ordered Leckie to put the aircraft down to rescue the two crew. However, now with six men aboard, damaged, and in heavy seas Leckie was unable to take off again. Some 75 miles from the English coast, the aircraft began to taxi towards home. Their radio was waterlogged, but they did have four homing pigeon

The homing pigeon is a variety of domestic pigeon (''Columba livia domestica''), selectively bred for its ability to find its way home over extremely long distances. Because of this skill, homing pigeons were used to carry messages, a practice ...

s. Nicholl attached messages to the birds giving their position and course and sent them off at intervals. After four hours the aircraft ran out of fuel, and began to drift, so they improvised a sea anchor

A sea anchor (also known as a parachute anchor, drift anchor, drift sock, para-anchor or boat brake) is a device that is streamed from a boat in heavy weather. Its purpose is to stabilize the vessel and to limit progress through the water. Rathe ...

from empty fuel cans to steady it. That night the damaged wing tip broke off, and each man then had to spend two hours at a time outside balanced on the opposite wing to keep the broken wing from filling with water and dragging the aircraft under. After three days at sea, the six men were suffering badly. They had no food and only two gallons of drinking water, gained from draining the radiators of their water-cooled engines. Finally, at dawn on 8 September, as search operations were about to be called off, one of the pigeons was found, dead from exhaustion, by the coastguard station at Walcot, and shortly after midday they were rescued by the torpedo gunboat

In the late 19th century, torpedo gunboats were a form of gunboat armed with torpedoes and designed for hunting and destroying smaller torpedo boats. By the end of the 1890s torpedo gunboats were superseded by their more successful contemporaries, ...

. Pigeon No. N.U.R.P./17/F.16331 was preserved, and originally kept in the officers' mess

The mess (also called a mess deck aboard ships) is a designated area where military personnel socialize, eat and (in some cases) live. The term is also used to indicate the groups of military personnel who belong to separate messes, such as the o ...

at RNAS Yarmouth, but is now on display at the RAF Museum Hendon. A brass plate on the display case bears the inscription "A very gallant gentleman".

On 31 December 1917 Leckie was appointed a flight commander

A flight commander is the leader of a constituent portion of an aerial squadron in aerial operations, often into combat. That constituent portion is known as a flight, and usually contains six or fewer aircraft, with three or four being a common ...

. While on patrol on 20 February 1918, Leckie spotted an enemy submarine on the surface, and attacked it with bombs, seeing one strike the vessel as it dived, leaving a large oil slick. Leckie was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

on 17 May 1918, only learning much later that he had not actually sunk it.

On 1 April 1918, the Royal Naval Air Service was merged with the Army's

On 1 April 1918, the Royal Naval Air Service was merged with the Army's Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

to form the Royal Air Force, and Leckie transferred to the new service with the rank of lieutenant (temporary captain), though on 8 April he was promoted to the temporary rank of major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

.

On 4 June 1918 Leckie led an offensive patrol of four Felixstowe F.2A flying boats and a Curtiss H.12 towards the Haaks Light Vessel off the Dutch coast. They saw no enemy aircraft until one of the F.2A's, number N.4533, was forced down with a broken fuel feed-pipe. Five enemy seaplanes appeared, but seemed more interested in attacking the crippled F.2A. The remaining aircraft circled N.4533 as it taxied towards to the Dutch coast (where the crew eventually burned their aircraft before being interned), until ten more German seaplanes appeared. Leckie promptly led his small force into a head on attack, and a dogfight ensued which lasted for 40 minutes. Despite further mechanical difficulties – two other F2A's also had problems with their fuel pipes and had to effect makeshift repairs while in the middle of the action – two German aircraft were shot down, and four badly damaged before the Germans broke off the action, for the loss of one F.2A and the Curtiss (its crew survived to be interned by the Dutch), and one man killed. Leckie's force returned to Great Yarmouth, and in his report he bitterly remarked "...these operations were robbed of complete success entirely through faulty petrol pipes... It is obvious that our greatest foes are not the enemy..."

On the afternoon of 5 August 1918 a squadron of five Zeppelins took off from Friedrichshafen

Friedrichshafen ( or ; Low Alemannic: ''Hafe'' or ''Fridrichshafe'') is a city on the northern shoreline of Lake Constance (the ''Bodensee'') in Southern Germany, near the borders of both Switzerland and Austria. It is the district capital (''K ...

. They headed for the east coast of England, timing their flight to arrive off the coast just after dark. The leading airship, '' L 70'' was commanded by ''Kapitänleutnant'' Johann von Lossnitzer, but also had ''Fregattenkapitän

() is the middle ranking senior officer in a number of Germanic-speaking navies.

Austro-Hungary

Belgium

Germany

, short: FKpt / in lists: FK, is the middle Senior officer military rank, rank () in the German Navy.

It is the equivalent o ...

'' Peter Strasser, the ''Führer der Luftschiffe'' ("Leader of Airships"), the commander of the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for ...

's airship force, on board. However, the airship squadron was spotted while out at sea by the Lenman Tail lightship which signalled their course and position to the Admiralty. Responding to the report Major Egbert Cadbury

Major (Honorary Air Commodore) Sir Egbert "Bertie" Cadbury (20 April 1893 – 12 January 1967) was a British businessman, a member of the Cadbury family, who as a First World War pilot shot down two Zeppelins over the North Sea: '' L.21'' on 28 ...

jumped into the pilot's seat of the only aircraft available, a DH.4, while Leckie occupied the observer/gunner's position. After about an hour they spotted the ''L 70'' and attacked, with Leckie firing eighty rounds of incendiary bullets into her. Fire rapidly consumed the airship as it plummeted into the sea. Cadbury and Leckie, and another pilot Lieutenant Ralph Edmund Keys, then attacked and damaged another Zeppelin, which promptly turned tail and headed for home. All three received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

A few days later, on 11 August 1918 Leckie took part in another operation over the North Sea. Zeppelins often shadowed British naval ships, while carefully operating at higher altitudes than anti-aircraft guns or flying boats could achieve, and out of range of land based aircraft, so the Harwich Light Cruiser Force set out with a Sopwith Camel

The Sopwith Camel is a British First World War single-seat biplane fighter aircraft that was introduced on the Western Front in 1917. It was developed by the Sopwith Aviation Company as a successor to the Sopwith Pup and became one of the b ...

lashed to a decked lighter

A lighter is a portable device which uses mechanical or electrical means to create a controlled flame, and can be used to ignite a variety of flammable items, such as cigarettes, butane gas, fireworks, candles, or campfires. A lighter typic ...

towed by the destroyer HMS ''Redoubt''. When Leckie's reconnaissance flight reported an approaching Zeppelin, the ''Redoubt'' steamed at full speed into the wind, allowing the Camel's pilot Lieutenant Culley to take off with only a five-yard run. Culley climbed to 18,800 feet, approached the ''L 53'' out of the sun, and attacked with his twin Lewis guns, setting the airship on fire.

On 20 August 1918 Leckie was appointed commander of the newly formed No. 228 Squadron, flying the Curtis H-12 and Felixstowe F.2A out of Great Yarmouth. Within three months the armistice brought the fighting to an end.

Inter-war career

Leckie remained with the RAF until 31 March 1919 when he was transferred to the unemployed list, and simultaneously seconded to the Canadian Air Force with the temporary rank of lieutenant colonel, to command the 1st Wing, Canadian Air Force. This unit comprised No. 81 Squadron (No. 1 Canadian), flying S.E.5 andSopwith Dolphin

The Sopwith 5F.1 Dolphin was a British fighter aircraft manufactured by the Sopwith Aviation Company. It was used by the Royal Flying Corps and its successor, the Royal Air Force, during the First World War. The Dolphin entered service on the ...

fighters, and No. 123 Squadron (No. 2 Canadian), flying Airco DH.9A

The Airco DH.9A is a British single-engined light bomber that was designed and first used shortly before the end of the First World War. It was a development of the unsuccessful Airco DH.9 bomber, featuring a strengthened structure and, cruciall ...

bombers, and was based at RAF Shoreham

Brighton City Airport , also commonly known as Shoreham Airport, is located in Lancing near Shoreham by Sea in West Sussex, England. It has a CAA Public Use Aerodrome Licence that allows flights for the public transport of passengers or for ...

, Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

. The Canadian Wing had been formed in August 1918 at RAF Upper Heyford

Royal Air Force Upper Heyford or more simply RAF Upper Heyford is a former Royal Air Force station located north-west of Bicester near the village of Upper Heyford, Oxfordshire, Upper Heyford, Oxfordshire, England. In the World War II, Second W ...

, Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire ( ; abbreviated ''Oxon'') is a ceremonial county in South East England. The county is bordered by Northamptonshire and Warwickshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the east, Berkshire to the south, and Wiltshire and Glouceste ...

, but never saw active service, and was eventually disbanded when the Canadian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF; French: ''Corps expéditionnaire canadien'') was the expeditionary warfare, expeditionary field force of Canada during the First World War. It was formed on August 15, 1914, following United Kingdom declarat ...

returned home.

On 1 August 1919 Leckie was granted a permanent commission in the Royal Air Force with the rank of major (later squadron leader), relinquishing his commission in the 1st Central Ontario Regiment of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada on the 31st.

On 15 December 1919 he was seconded for duty with the Canadian Air Board serving as Superintendent of Flying Operations. In this role he played a central role in the development of Canadian civil aviation, organizing and taking part in the first trans-Canada flight between Halifax and Vancouver

Vancouver is a major city in Western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the cit ...

. Leckie and Major Basil Hobbs flew from Halifax to Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. It is centred on the confluence of the Red River of the North, Red and Assiniboine River, Assiniboine rivers. , Winnipeg h ...

between 7 and 10 October 1920, before other pilots and aircraft took over, finally arriving in Vancouver on the 17th.

Leckie's secondment ended on 27 May 1922, and he returned to Britain to be posted to the No. 1 School of Technical Training

No. 1 School of Technical Training (No. 1 S of TT) is the Royal Air Force, Royal Air Force's aircraft engineering school. It was based at RAF Halton from 1919 to 1993, as the Home of the Aircraft Apprentice scheme. The Aircraft Apprentice s ...

at RAF Halton

Royal Air Force Halton, or more simply RAF Halton, is one of the largest Royal Air Force stations in the United Kingdom. It is located near the village of Halton near Wendover, Buckinghamshire. The site has been in use since the First World ...

on 8 June. On 25 September he was posted the RAF Depot (Inland Area) as a supernumerary officer, in order to attend the Royal Navy Staff College. On 5 July 1923 he was posted to the Headquarters of RAF Coastal Area.

On 1 January 1926 Leckie was promoted to wing commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr or W/C) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Wing commander is immediately se ...

, and on 16 March was posted to Headquarters, Mediterranean, where on 30 March he joined the aircraft carrier to serve as Senior Air Force Officer. He returned to the depot at RAF Uxbridge

RAF Uxbridge was a Royal Air Force (RAF) station in Uxbridge, within the London Borough of Hillingdon, occupying a site that originally belonged to the Hillingdon House estate. The British Government purchased the estate in 1915, three years b ...

on 11 May 1927, and on 26 August was posted to Headquarters, Coastal Area, while he waited for to be commissioned. Following the completion of her conversion to an aircraft carrier ''Courageous'' was commissioned at Devonport on 14 February 1928, and on 21 February Leckie joined her as Senior Air Force Officer.

Leckie returned to dry land on 5 September 1929, when he was appointed commander of RAF Bircham Newton, Norfolk. On 11 April 1931 he became commander of No. 210 Squadron RAF, initially based at Felixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town and civil parish in the East Suffolk District, East Suffolk district, in the county of Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest Containerization, containe ...

, and then RAF Pembroke Dock, flying the Supermarine Southampton

The Supermarine Southampton was a flying boat of the interwar period designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Supermarine. It was one of the most successful flying boats of the era.

The Southampton was derived from the expe ...

Mk. II. On 1 January 1933 Leckie was promoted to group captain

Group captain (Gp Capt or G/C) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many Commonwealth of Nations, countries that have historical British influence.

Group cap ...

, and on 30 January he was appointed both Superintendent of the RAF Reserve and commander of RAF Hendon

Hendon is an urban area in the London Borough of Barnet, northwest London northwest of Charing Cross. Hendon was an ancient manor and parish in the county of Middlesex and a former borough, the Municipal Borough of Hendon; it has been part of ...

. On 21 August 1935 Leckie was also appointed an additional Air Aide-de-Camp

An air aide-de-camp is a senior honorary aide-de-camp appointment for air officers in the Royal Air Force, the Royal Australian Air Force and the Indian Air Force. Normally the recipient is appointed as an air aide-de-camp to the head of state. ...

to King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

, attending the King's funeral in that capacity on 28 January 1936, and was appointed Air Aide-de-Camp to King Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire, and Emperor of India, from 20 January ...

on 1 July 1936. Leckie was appointed Director of Training at the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force and civil aviation that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the ...

on 5 October 1936, taking over from Air Commodore Arthur Tedder

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Arthur William Tedder, 1st Baron Tedder, (11 July 1890 – 3 June 1967) was a British Royal Air Force officer and peer. He was a pilot and squadron commander in the Royal Flying Corps in the First World War and h ...

, and was promoted to air commodore

Air commodore (Air Cdre or Air Cmde) is an air officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is also used by the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence and it is sometimes ...

on 1 January 1937, handing over the post as Air Aide-de-Camp to the King to Group Captain Keith Park

Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Rodney Park, (15 June 1892 – 6 February 1975) was a New Zealand-born officer of the Royal Air Force (RAF). During the Second World War, his leadership of the RAF's No. 11 Group RAF, No. 11 Group was pivotal to t ...

the same day. Leckie's tenure as Director of Training ended on 28 November 1938, and on 2 December 1938 he was appointed Air Officer Commanding, RAF Mediterranean, based at Malta.

Second World War

In 1940, Leckie was seconded to theRoyal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; ) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environmental commands within the unified Can ...

to establish the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), often referred to as simply "The Plan", was a large-scale multinational military aircrew training program created by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand during the Second Wo ...

(BCATP) in Canada. By the end of the war BCATP had trained 131,553 air crew from 11 countries. On 5 August 1941 he was promoted to the acting rank

An acting rank is a designation that allows military personnel to assume a higher military rank, which is usually temporary. They may assume that rank either with or without the pay and allowances appropriate to that grade, depending on the natu ...

of air vice-marshal

Air vice-marshal (Air Vce Mshl or AVM) is an air officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is also used by the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence and it is sometime ...

, and served as Member of the Air Council for Training. On 6 April 1942 Leckie was placed on the RAF retired list on accepting a commission in the Royal Canadian Air Force. On 2 June 1943 he was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

(CB). From 1 January 1944 until 31 August 1947 Leckie served as Chief of Staff, RCAF with the rank of air marshal.

For his service during the Second World War Leckie received the Order of Polonia Restituta

The Order of Polonia Restituta (, ) is a Polish state decoration, state Order (decoration), order established 4 February 1921. It is conferred on both military and civilians as well as on alien (law), foreigners for outstanding achievements in ...

(1st class) from the President of the Republic of Poland on 1 May 1945, and was also made a Commander of the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States military, military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievemen ...

by the United States, and a Grand Officer of both the Belgian Order of the Crown and the Czechoslovakian Order of the White Lion

The Order of the White Lion () is the highest order of the Czech Republic. It continues a Czechoslovak order of the same name created in 1922 as an award for foreigners (Czechoslovakia having no civilian decoration for its citizens in the 192 ...

. In July 1948 he was awarded the King Haakon VII Freedom Cross by the King of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty king ...

"in recognition of distinguished services rendered in the cause of the Allies".

Post-war career

Leckie retired from the Royal Canadian Air Force on 1 September 1947, though he continued to take an interest in aviation, serving as a special consultant to the Air Cadet League. Air Marshal Leckie died on 31 March 1975, the last surviving wartime Chief of the Air Staff, aged 84. He was survived by his widow, Bernice, and two sons. Leckie was inducted into the Canadian Aviation Hall of Fame in 1988.Footnotes

References

External links

*Canada's 25 Most Renowned Military Leaders

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Leckie, Robert 1890 births 1975 deaths Royal Canadian Air Force officers Military personnel from Glasgow Scottish airmen Scottish emigrants to Canada Canadian Expeditionary Force officers Royal Naval Air Service aviators Canadian World War I pilots Canadian military personnel of World War II Royal Air Force air marshals of World War II Royal Canadian Air Force air marshals of World War II Canadian Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Canadian Companions of the Order of the Bath Canadian recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Grand Officers of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Grand Officers of the Order of the White Lion Graduates of the Royal Naval College, Greenwich Grand Crosses of the Order of Polonia Restituta Commanders of the Legion of Merit Recipients of the King Haakon VII Freedom Cross Canadian recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Presidents of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society Canadian people of Scottish descent