Rise Of Nationalism In The Ottoman Empire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The rise of the

Arab nationalism is a

Arab nationalism is a

The rise of national conscience in Bulgaria led to the Bulgarian revival movement. Unlike Greece and

The rise of national conscience in Bulgaria led to the Bulgarian revival movement. Unlike Greece and

With the decline of the

With the decline of the

While the Ottoman Empire became a safe space for Jews, parts of Europe saw increased violence and anti-semitism against Jews. Violent uprisings against Jews took place all over Eastern Europe in the Late 19th century, and the civil rights of Jews were extremely limited.

Zionism is an international

While the Ottoman Empire became a safe space for Jews, parts of Europe saw increased violence and anti-semitism against Jews. Violent uprisings against Jews took place all over Eastern Europe in the Late 19th century, and the civil rights of Jews were extremely limited.

Zionism is an international

The Jewish National Fund functioned similarly. It was a fund directed for land purchasing in Palestine. By 1921, around 25,000 acres had been purchased by the Fund in Palestine. Immigration of Jewish people into Palestine in 4 periods or Aliyahs. The first took place between 1881 and 1903, resulting in around 25,000 immigrating. The second took place between 1904 and 1914, resulting in around 35,000 Jews immigrating.

The increased Jewish population and Jewish land in Israel furthered the formation of a Jewish national identity. As the population and property owned by Jews increased in Palestine, support and backing continued to grow. However, so did tensions with other groups, especially Muslim Arabs. Arabs saw the massive Jewish immigration and financial interest in the region as threatening.

The Jewish National Fund functioned similarly. It was a fund directed for land purchasing in Palestine. By 1921, around 25,000 acres had been purchased by the Fund in Palestine. Immigration of Jewish people into Palestine in 4 periods or Aliyahs. The first took place between 1881 and 1903, resulting in around 25,000 immigrating. The second took place between 1904 and 1914, resulting in around 35,000 Jews immigrating.

The increased Jewish population and Jewish land in Israel furthered the formation of a Jewish national identity. As the population and property owned by Jews increased in Palestine, support and backing continued to grow. However, so did tensions with other groups, especially Muslim Arabs. Arabs saw the massive Jewish immigration and financial interest in the region as threatening.

An important aspect of forming a national Jewish identity, especially based on religion, was the construction of Synagogues. The Jewish houses of worship allowed Jews to congregate in worship and share their ideas and beliefs. Many synagogues were constructed or rebuilt during Ottoman rule. The Bet Yaakov Synagogue was constructed in Istanbul in 1878. The Ahrida Synagogue is an extremely notable one built in Istanbul in the 1430s. It is located in the Balat area of Istanbul, a formerly vibrant Jewish area. These synagogues were able to function as the cultural center within their own communities.

An important aspect of forming a national Jewish identity, especially based on religion, was the construction of Synagogues. The Jewish houses of worship allowed Jews to congregate in worship and share their ideas and beliefs. Many synagogues were constructed or rebuilt during Ottoman rule. The Bet Yaakov Synagogue was constructed in Istanbul in 1878. The Ahrida Synagogue is an extremely notable one built in Istanbul in the 1430s. It is located in the Balat area of Istanbul, a formerly vibrant Jewish area. These synagogues were able to function as the cultural center within their own communities.

The

The

The Serbian national movement represents one of the first examples of successful national resistance against the Ottoman rule. It culminated in two mass uprisings at the beginning of the 19th century, leading to national liberation and establishment of the

The Serbian national movement represents one of the first examples of successful national resistance against the Ottoman rule. It culminated in two mass uprisings at the beginning of the 19th century, leading to national liberation and establishment of the

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

notion of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

eventually caused the breakdown of the Ottoman ''millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most millets belong to the tribe Paniceae.

Millets are important crops in the Semi-arid climate, ...

'' system. The concept of nationhood, which was different from the preceding religious community concept of the millet system, was a key factor in the decline of the Ottoman Empire.

Background

In theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, the Islamic faith was the official religion, with members holding all rights, as opposed to Non-Muslims, who were restricted. Non-Muslim ('' dhimmi'') ethno-religious legal groups were identified as different '' millets'', which means "nations".

Ideas of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

emerged in Europe in the 19th century at a time when most of the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

were still under Ottoman rule. The Christian peoples of the Ottoman Empire, starting with Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of Serbia, history, and Serbian lan ...

and Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

, but later spreading to Montenegrins

Montenegrins (, or ) are a South Slavic ethnic group that share a common ancestry, culture, history, and language, identified with the country of Montenegro.

Montenegrins are mostly Orthodox Christians; however, the population also includes ...

and Bulgarians

Bulgarians (, ) are a nation and South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and its neighbouring region, who share a common Bulgarian ancestry, culture, history and language. They form the majority of the population in Bulgaria, ...

, began to demand autonomy in a series of armed revolts beginning with the Serbian Revolution

The Serbian Revolution ( / ') was a national uprising and constitutional change in Serbia that took place between 1804 and 1835, during which this territory evolved from an Sanjak of Smederevo, Ottoman province into a Revolutionary Serbia, reb ...

(1804–17) and the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

(1821–29), which established the Principality of Serbia

The Principality of Serbia () was an autonomous, later sovereign state in the Balkans that came into existence as a result of the Serbian Revolution, which lasted between 1804 and 1817. Its creation was negotiated first through an unwritten agre ...

and Hellenic Republic

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. The first revolt in the Ottoman Empire fought under a nationalist ideology was the Serbian Revolution. Later the Principality of Montenegro

The Principality of Montenegro () was a principality in Southeastern Europe that existed from 13 March 1852 to 28 August 1910. It was then proclaimed a Kingdom of Montenegro, kingdom by Nikola I of Montenegro, Nikola I, who then became King of M ...

was established through the Montenegrin secularization

In sociology, secularization () is a multilayered concept that generally denotes "a transition from a religious to a more worldly level." There are many types of secularization and most do not lead to atheism or irreligion, nor are they automatica ...

and the Battle of Grahovac. The Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

was established through the process of the Bulgarian National Revival

The Bulgarian Revival (, ''Balgarsko vazrazhdane'' or simply: Възраждане, ''Vazrazhdane'', and ), sometimes called the Bulgarian National Revival, was a period of socio-economic development and national integration among Bulgarian pe ...

, and the subsequent National awakening of Bulgaria, establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (; ) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) ...

, the April Uprising of 1876

The April Uprising () was an insurrection organised by the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire from April to May 1876. The rebellion was suppressed by irregular military, irregular Ottoman bashi-bazouk units that engaged in indiscriminate slaught ...

, and the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

The Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) was a conflict between the Ottoman Empire and a coalition led by the Russian Empire which included United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, Romania, Principality of Serbia, Serbia, and Principality of ...

.

The radical elements of the Young Turk movement in the early 20th century had grown disillusioned with what they perceived to be the failures of 19th-century Ottoman reformers, who had not managed to stop the advance of European expansionism or the spread of nationalist movements in the Balkans. These sentiments were shared by the Kemalists. These groups decided to abandon the idea of '' Ittihad-i anasır'' ("Unity of the Ethnic Elements") that had been a fundamental principle of the reform generation, and take up instead the mantle of Turkish nationalism

Turkish nationalism () is nationalism among the people of Turkey and individuals whose national identity is Turkish. Turkish nationalism consists of political and social movements and sentiments prompted by a love for Turkish culture, Turkish ...

.

Michael Hechter argues that the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire was the result of a backlash against Ottoman attempts to institute more direct and central forms of rule over populations which had previously had greater autonomy.

Albanians

The 1877–78 Russo-Turkish War dealt a decisive blow to Ottoman power in theBalkan Peninsula

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, leaving the empire with only a precarious hold on Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

and the Albanian-populated lands. The Albanians' fear that the lands they inhabited would be partitioned among Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

, Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, and Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

fueled the rise of Albanian nationalism

Albanian nationalism is a general grouping of nationalism, nationalist ideas and concepts generated by ethnic Albanians that were first formed in the 19th century during the Albanian National Awakening (). Albanian nationalism is also associated w ...

. The Albanians wanted to affirm their Albanian nationality. The first postwar treaty, the abortive Treaty of San Stefano signed on March 3, 1878, assigned Albanian-populated lands to Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria. The Albanian movements had mainly been against taxes and central policies. However, with the Treaty of San Stefano the movements became nationalistic. Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

and the United Kingdom blocked the arrangement because it awarded Russia a predominant position in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

and thereby upset the European balance of power. A peace conference to settle the dispute was held later in the year in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, known as the Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

. A memorandum

A memorandum (: memorandums or memoranda; from the Latin ''memorandum'', "(that) which is to be remembered"), also known as a briefing note, is a Writing, written message that is typically used in a professional setting. Commonly abbreviation, ...

in the name of all Albanians was addressed to Lord Beaconsfield from Great Britain not even a week after the opening of the Congress of Berlin. The reason why this memorandum was addressed to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

was that the Albanians

The Albanians are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, Albanian culture, culture, Albanian history, history and Albanian language, language. They are the main ethnic group of Albania and Kosovo, ...

could not represent themselves, because they were still under Ottoman rule. Another reason why Great Britain was in the best position to represent the Albanians, because Great Britain did not want to replace the Turkish Empire. This memorandum had to define the land belonging to the Albanians and create an independent Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

.

Arabs

Arab nationalism is a

Arab nationalism is a nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

ideology that arose in the 20th centuryCharles Smith, The Arab-Israeli Conflict, in ''International Relations in the Middle East'' by Louise Fawcett, p. 220. It is based on the premise that nations from Morocco to the Arabian peninsula are united by their common linguistic, cultural and historical heritage. Pan-Arabism

Pan-Arabism () is a Pan-nationalism, pan-nationalist ideology that espouses the unification of all Arabs, Arab people in a single Nation state, nation-state, consisting of all Arab countries of West Asia and North Africa from the Atlantic O ...

is a related concept, which calls for the creation of a single Arab state, but not all Arab nationalists are also Pan-Arabists. In the 19th century in response to Western influences, a radical change took shape. Conflict erupted between Muslims and Christians in different parts of the empire in a challenge to that hierarchy. This marked the beginning of the tensions which have to a large extent inspired the nationalist and religious rhetoric in the empire's successor states throughout the 20th century.

A sentiment of Arab tribal solidarity ('' asabiyya''), underlined by claims of Arab tribal descent and the continuance of classical Arabic

Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic () is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, e ...

exemplified in the Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

, preserved, from the rise of Islam, a vague sense of Arab identity among Arabs. However, this phenomenon had no political manifestations (the 18th-century Wahhabi

Wahhabism is an exonym for a Salafi revivalist movement within Sunni Islam named after the 18th-century Hanbali scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. It was initially established in the central Arabian region of Najd and later spread to other ...

movement in Arabia was a religious-tribal movement, and the term "Arab" was used mainly to describe the inhabitants of Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

and nomads) until the late 19th century, when the revival of Arabic literature

Arabic literature ( / ALA-LC: ''al-Adab al-‘Arabī'') is the writing, both as prose and poetry, produced by writers in the Arabic language. The Arabic word used for literature is ''Adab (Islam), Adab'', which comes from a meaning of etiquett ...

was followed in the Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

n provinces of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

in Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

and Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

by a discussion of Arab cultural identity and demands for greater autonomy for Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

. This movement, however, was confined almost exclusively to certain Christian Arabs, and had little support. After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 in Turkey, these demands were taken up by some Syrian and Lebanese Muslim Arabs and various public or secret societies (the Beirut Reform Society led by Salim Ali Salam, 1912; the Ottoman Administrative Decentralization Party, 1912; al-Qahtaniyya, 1909; al-Fatat, 1911; and al-Ahd, 1912) were formed to advance demands ranging from autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

to independence for the Ottoman Arab provinces. Members of some of these groups came together at the request of al-Fatat to form the Arab Congress of 1913 in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, where desired reforms were discussed.

Armenians

Until theTanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...

reforms were established, the Armenian millet was under the supervision of an Ethnarch

Ethnarch (pronounced , also ethnarches, ) is a term that refers generally to political leadership over a common ethnic group or homogeneous kingdom. The word is derived from the Greek language, Greek words (''Ethnic group, ethnos'', "tribe/nation ...

('national' leader), the Armenian Apostolic Church

The Armenian Apostolic Church () is the Autocephaly, autocephalous national church of Armenia. Part of Oriental Orthodoxy, it is one of the most ancient Christianity, Christian churches. The Armenian Apostolic Church, like the Armenian Catholic ...

. The Armenian millet had a great deal of power - they set their own laws and collected and distributed their own taxes. During the Tanzimat period, a series of constitutional reforms provided a limited modernization of the Ottoman Empire also to the Armenians. In 1856, the " Reform Edict" promised equality for all Ottoman citizens irrespective of their ethnicity and confession, widening the scope of the 1839 Edict of Gülhane.

To deal with the Armenian national awakening, the Ottomans gradually gave more rights to its Armenian and other Christian citizens. In 1863 the Armenian National Constitution was the Ottoman-approved form of the "Code of Regulations" composed of 150 articles drafted by the "Armenian intelligentsia", which defined the powers of the Armenian Patriarch and the newly formed " Armenian National Assembly". The reformist period peaked with the Ottoman constitution of 1876, written by members of the Young Ottomans

The Young Ottomans (; ) were a secret society established in 1865 by a group of Ottoman intellectuals who were dissatisfied with the '' Tanzimat'' reforms in the Ottoman Empire, which they believed did not go far enough. The Young Ottomans soug ...

, which was promulgated on 23 November 1876. It established freedom of belief and equality of all citizens before law. The Armenian National Assembly formed a "governance in governance" to eliminate the aristocratic

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense economic, political, and social influence. In Western Christian co ...

dominance of the Armenian nobility by the development of the political strata among the Armenian society.

Aromanians

A distinct Aromanian consciousness was not developed until the 19th century, and was influenced by the rise of other national movements in the Balkans. Until then, the Aromanians, as Eastern Orthodox Christians, were subsumed with other ethnic groups into the wider ethnoreligious group of the "Romans" (in Greek '' Rhomaioi'', after the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire), which in Ottoman times formed the distinct '' Rum millet''. The ''Rum millet'' was headed by the Greek-dominatedPatriarchate of Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (, ; ; , "Roman Orthodox Patriarchate, Ecumenical Patriarchate of Istanbul") is one of the fifteen to seventeen autocephalous churches that together compose the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is headed ...

, and the Greek language was used as a ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, link language or language of wider communication (LWC), is a Natural language, language systematically used to make co ...

'' among Balkan Orthodox Christians throughout the 17th–19th centuries. As a result, wealthy, urbanized Aromanians were culturally Hellenized and played a major role in the dissemination of Greek language and culture; indeed, the first book written in Aromanian was written in the Greek alphabet

The Greek alphabet has been used to write the Greek language since the late 9th or early 8th century BC. It was derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet, and is the earliest known alphabetic script to systematically write vowels as wel ...

and aimed at spreading Greek among Aromanian-speakers.

By the early 19th century, however, the distinct Latin-derived nature of the Aromanian language began to be studied in a series of grammars and language booklets. In 1815, the Aromanians of Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

requested permission to use their language in liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

, but it was turned down by the local metropolitan.

The establishment of a distinct Aromanian national consciousness, however, was hampered by the tendency of the Aromanian upper classes to be absorbed in the dominant surrounding ethnicities, and espouse their respective national causes as their own. So much did they become identified with the host nations that Balkan national historiographies portray the Aromanians as the "best Albanians", "best Greeks" and "best Bulgarians", leading to researchers calling them the "chameleon

Chameleons or chamaeleons (Family (biology), family Chamaeleonidae) are a distinctive and highly specialized clade of Old World lizards with 200 species described as of June 2015. The members of this Family (biology), family are best known for ...

s of the Balkans". Consequently, many Aromanians played a prominent role in the modern history of the Balkan nations: the revolutionary Pitu Guli, Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Kolettis, Greek magnate Georgios Averoff, Greek Defence Minister Evangelos Averoff, Serbian Prime Minister Vladan Đorđević, Patriarch Athenagoras I of Constantinople, Romanian metropolitan Andrei Şaguna etc.

Following the establishment of independent Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

and the autocephaly

Autocephaly (; ) is the status of a hierarchical Christian church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches. The status has been compared with t ...

of the Romanian Orthodox Church

The Romanian Orthodox Church (ROC; , ), or Romanian Patriarchate, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox Christian denomination, Christian churches, and one of the nine patriarchates in the East ...

in the 1860s, the Aromanians increasingly began to come under the influence of the Romanian national movement. Although vehemently opposed by the Greek church, the Romanians established an extensive state-sponsored cultural and educative network in the southern Balkans: the first Romanian school was established in 1864 by the Aromanian Dimitri Atanasescu, and by the early 20th century there were 100 Romanian churches and 106 schools with 4,000 pupils and 300 teachers. As a result, Aromanians divided into two main factions, one pro-Greek, the other pro-Romanian, plus a smaller focusing exclusively on its Aromanian identity.

With the support of the Great Powers, and especially Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, the "Aromanian-Romanian movement" culminated in the recognition of the Aromanians as a distinct ''millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most millets belong to the tribe Paniceae.

Millets are important crops in the Semi-arid climate, ...

'' (the Ullah millet) by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

on 22 May 1905, with corresponding freedoms of worship and education in their own language. Nevertheless, due to the advanced assimilation of the Aromanians, this came too late to lead to the creation of a distinct Aromanian national identity; indeed, as Gustav Weigand noted in 1897, most Aromanians were not only indifferent, but actively hostile to their own national movement.

Assyrians

Under the millet system of the Ottoman Empire, each sect of the Assyrian nation was represented by their respective patriarch. Under the Church of the East sect, the patriarch was the temporal leader of the millet which then had a number of "maliks" beneath the patriarch who would govern each of their own tribes. The rise of modern Assyrian nationalism began with intellectuals such as Ashur Yousif, Naum Faiq and Farid Nazha who pushed for a united Assyrian nation comprising the Jacobite, Nestorian and Chaldean sects.Bosniaks

The Ottoman Sultans attempted to implement various economic reforms in the early 19th century in order to address the grave issues mostly caused by the border wars. The reforms, however, were usually met with resistance by the military captaincies of Bosnia. The most famous of these insurrections was the one by captain Husein Gradaščević in 1831. Gradaščević felt that giving autonomy to the eastern lands of Serbia, Greece and Albania would weaken the position of the Bosnian state, and the Bosniak peoples. The situation worsened when the Ottomans took 2 Bosnian provinces and gave them to Serbia, as a friendly gift to the Serbs. Outraged, Gradaščević raised a full-scale rebellion in the province, joined by thousands of native Bosnian soldiers who believed in the captain's prudence and courage, calling him ''Zmaj od Bosne'' (dragon

A dragon is a Magic (supernatural), magical legendary creature that appears in the folklore of multiple cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but European dragon, dragons in Western cultures since the Hi ...

of Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

). Despite winning several notable victories, notably at the famous Battle of Kosovo, the rebels were eventually defeated in a battle near Sarajevo in 1832 after Herzegovinian nobility which supported the Sultan, broke stalemate. Husein-kapetan was banned from ever entering the country again, and was eventually poisoned in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

. Bosnia and Herzegovina would remain part of the Ottoman Empire until 1878. Before it was formally occupied by Austria-Hungary, the region was de facto independent for several months. The aim of the movement of Husein Gradaščević was to keep status quo in Bosnia. Bosniak nationalism in the modern sense would emerge under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Bulgarians

The rise of national conscience in Bulgaria led to the Bulgarian revival movement. Unlike Greece and

The rise of national conscience in Bulgaria led to the Bulgarian revival movement. Unlike Greece and Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

, the nationalist movement in Bulgaria did not concentrate initially on armed resistance against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

but on peaceful struggle for cultural and religious autonomy, the result of which was the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (; ) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) ...

on February 28, 1870. A large-scale armed struggle movement started to develop as late as the beginning of the 1870s with the establishment of the Internal Revolutionary Organisation

The Internal Revolutionary Organisation (IRO; ) was a Bulgarians, Bulgarian revolutionary organisation founded and built up by Bulgarian revolutionary Vasil Levski between 1869 and 1871. The organisation represented a network of regional revolution ...

and the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee, as well as the active involvement of Vasil Levski

Vasil Levski (, spelled in Reforms of Bulgarian orthography, old Bulgarian orthography as , ), born Vasil Ivanov Kunchev (; 18 July 1837 – 18 February 1873), was a Bulgarians, Bulgarian revolutionary who is, today, a Folk hero, national ...

in both organisations. The struggle reached its peak with the April Uprising which broke out in April 1876 in several Bulgarian districts in Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia. The harsh suppression of the uprising and the atrocities committed against the civilian population increased the Bulgarian desire for independence. They also caused a tremendous indignation in Europe, where they became known as the Bulgarian Horrors. Consequently, at the 1876–1877 Constantinople Conference, also known as the Shipyard Conference, European statesmen proposed a series of reforms. Russia threatened the Sultan with Cyprus if he did not agree to the conditions. However, the sultan refused to implement them, as the terms were very harsh, and Russia declared war. During the war Bulgarian volunteer forces (in Bulgarian опълченци) fought alongside the Russian army. They earned particular distinction in the battle for the Shipka Pass. Upon the end of the war Russia and Turkey signed the Treaty of San Stefano, which granted Bulgaria autonomy from the Sultan. The Treaty of Berlin, signed in 1878, essentially nullified the Treaty of San Stefano. Instead, Bulgaria was divided into two provinces. The northern province was granted political autonomy, and was called Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria () was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ended with a Russian victory, the Treaty of San Stefano was signed ...

, while the southern province of Eastern Rumelia was placed under direct political and military control of the Sultan.

Greeks

With the decline of the

With the decline of the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

, the pre-eminent role of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

culture, literature and language became more apparent. From the 13th century onwards, with the territorial reduction of the Empire to strictly Greek-speaking areas, the old multiethnic tradition, already weakened, gave way to a self-consciously national Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

consciousness, and a greater interest in Hellenic culture evolved. Byzantines began to refer to themselves not just as Romans ''( Rhomaioi)'' but as Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

''( Hellenes).'' With the political extinction of the Empire, it was the Greek Orthodox Church

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Christianity in Greece, Greek Christianity, Antiochian Greek Christians, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christian ...

, and the Greek-speaking communities in the areas of Greek colonization and emigration, that continued to cultivate this identity, through schooling as well as the ideology of a Byzantine imperial heritage rooted both in the classical Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archa ...

past and in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

.

The position of educated and privileged Greeks within the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

improved in the 17th and 18th centuries. As the empire became more settled, and began to feel its increasing backwardness in relation to the European powers, it increasingly recruited Greeks who had the kind of academic, administrative, technical and financial skills which the larger Ottoman population lacked. Greeks made up the majority of the Empire's translators, financiers, doctors and scholars. From the late 1600s, Greeks began to fill some of the highest offices of the Ottoman state. The Phanariotes, a class of wealthy Greeks who lived in the Phanar district of Constantinople, became increasingly powerful. Their travels to other parts of Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, as merchants or diplomats, brought them into contact with advanced ideas of the Enlightenment notably liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

, radicalism and nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

, and it was among the Phanariotes that the modern Greek nationalist movement matured. However, the dominant form of Greek nationalism (that later developed into the Megali Idea) was a messianic ideology of imperial Byzantine restoration, that specifically looked down upon ''Frankish'' culture, and enjoyed the patronage of the Orthodox Church.

Ideas of nationalism began to develop in Europe long before they reached the Ottoman Empire. Some of the first effects nationalism had on the Ottomans had much to do with the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

. The war began as an uprising against the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. At the time, Mehmet Ali Mehmet Ali, Memet Ali or Mehmed Ali ("Ali"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.) is a Turkish language, Turkish ...

, a former Albanian mercenary, was ruling Egypt quite successfully. One of his biggest projects was creating a modern army of conscripted peasants. The Sultan commanded him to lead his army to Greece and put a stop to these uprisings. At the time, nationalism had become an established concept in Europe and certain Greek intellectuals began to embrace the idea of a purely Greek state. Most of Europe greatly supported this notion, partly because ideas of ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.) is a Turkish language, Turkish ...

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

's mythology were being greatly romanticized in the Western world. Though the Greece at the time of the revolution looked very little like the European view, most supported it blindly based on this notion.

Mehmet Ali Mehmet Ali, Memet Ali or Mehmed Ali ("Ali"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.) is a Turkish language, Turkish ...

had his own motives for agreeing to invade Greece. The Sultan promised Ali that he would make him Governor of Crete, which would increase Ali's status. Ali's army had considerable success in putting down the Christian revolts at first, however before too long the European Powers intervened. They endorsed Greek nationalism and pushed both Ali's army and the rest of the Ottoman forces out of Greece.

The instance of Greek Nationalism was a major factor in introducing the concept to the Ottomans. Because of their failure in Greece, the Ottomans were forced to acknowledge the changes taking place in the West, in favor of Nationalism. The result would be the beginning of a defensive ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.) is a Turkish language, Turkish ...

developmentalism

Developmentalism is an economic theory which states that the best way for less developed economies to develop is through fostering a strong and varied internal market and imposing high tariffs on imported goods.

Developmentalism is a cross-disci ...

period of Ottoman history in which they attempted to modernize to avoid the Empire falling to foreign powers. The idea of nationalism that develops out of this is called Ottomanism

Ottomanism or ''Osmanlılık'' (, . ) was a concept which developed prior to the 1876–1878 First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Its proponents believed that it could create the Unity of the Peoples, , needed to keep religion-based ...

, and would result in many political, legal, and social changes in the Empire.

* In 1821 the Greek revolution, striving to create an independent Greece, broke out on Romanian ground, briefly supported by the princes of Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

and Muntenia

Muntenia (, also known in English as Greater Wallachia) is a historical region of Romania, part of Wallachia (also, sometimes considered Wallachia proper, as ''Muntenia'', ''Țara Românească'', and the rarely used ''Valahia'' are synonyms in Ro ...

.

* A secret Greek nationalist organization called the Friendly Society (Filiki Eteria

Filiki Eteria () or Society of Friends () was a secret political and revolutionary organization founded in 1814 in Odesa, Odessa, whose purpose was to overthrow Ottoman Empire, Ottoman rule in Ottoman Greece, Greece and establish an Independenc ...

) was formed in Odesa

Odesa, also spelled Odessa, is the third most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern ...

during 1814. On March 25 (now Greek Independence Day) 1821 of the Julian Calendar

The Julian calendar is a solar calendar of 365 days in every year with an additional leap day every fourth year (without exception). The Julian calendar is still used as a religious calendar in parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church and in parts ...

/6 April 1821 of the Gregorian Calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It went into effect in October 1582 following the papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XIII, which introduced it as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian cale ...

the Orthodox Metropolitan Germanos of Patras proclaimed the national uprising. Simultaneous risings were planned across Greece, including in Macedonia, Crete and Cyprus. The revolt began in March 1821 when Alexandros Ypsilantis, the leader of the Etairists, crossed the Prut River into Turkish-held Moldavia with a small force of troops. With the initial advantage of surprise, the Greeks succeeded in liberating the Peloponnese and some other areas.

Kurds

The system of administration introduced by Idris remained unchanged until the close of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29. But the Kurds, owing to the remoteness of their country from the capital and the decline of Ottoman Empire, had greatly increased in influence and power, and had spread westwards over the country as far asAnkara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

.

After the war the Kurds attempted to free themselves from Ottoman control , and in 1834, after the Bedirkhan clan uprising, it became necessary to reduce them to subjection. This was done by Reshid Pasha. The principal towns were strongly garrisoned, and many of the Kurd bey

Bey, also spelled as Baig, Bayg, Beigh, Beig, Bek, Baeg, Begh, or Beg, is a Turkic title for a chieftain, and a royal, aristocratic title traditionally applied to people with special lineages to the leaders or rulers of variously sized areas in ...

s were replaced by Turkish governors. A rising under Bedr Khan Bey in 1843 was firmly repressed, and after the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

the Turks strengthened their hold on the country.

The Ottoman Empire, faced with challenges from their European counterparts, started a centralisation campaign, intending to have more direct authority over resources and population. After beating Kurdish autonomy, namely the principality of Bohtan, also known as Cizira Bohtan, in present-day Cizre

Cizre () is a city in the Cizre District of Şırnak Province in Turkey. It is located on the river Tigris by the Syria–Turkey border and close to the Iraq–Turkey border. Cizre is in the historical region of Upper Mesopotamia and the cultura ...

, the Sultan had hoped that the region would now be more manageable and under Ottoman control. However, the opposite was true. The Empire did not gain any authority because of a lack of local institutions and not actively creating them. Instead, by removing the Mirs and thus the local power structure, the area became more chaotic. Local tribes sought to exploit the situation and advance their own interests. Unable to directly confront Istanbul, the emergence of the Russian Empire’s advances on the Anatolian plateau posed an opportunity.

By this time, the Kurdish revolts in the Ottoman Empire were still not seen as a part of nationalism, but rather as attempts of local leaders to increase influence. This mostly changed during Şêx Ubeydullah's and Abdurezzak's involvements in the late eighteenth-century Russo-Turkish conflicts.

The Sultan attempted to assert his influence in the Kurdish areas by installing the Hamidiye regiments. The commanders were selected on the basis of loyalty to the Sultan, and were awarded with several privileges, mainly the right to form militias, and gifted these tribal leaders with titles, arms and money in the hopes that this would lead to a new class of ruling elites. The rise of intellectualism and activism amongst the population of Kurds brought critique to this new elitist class. Some of the most well-known opponents of Sultan Abdulhamid II were descendants of the Mir of Bohtan, claiming that these policies were stagnating Kurdish progress and well-being. They called for modern educational reforms. The Naqshbandi Şêx Bediüzzaman Said-i Kurdi even travelled to Istanbul to address the need for education in Kurdish areas to the Sultan.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 was followed by the attempt of Sheikh Obaidullah in 1880–1881 to found an independent Kurd principality

A principality (or sometimes princedom) is a type of monarchy, monarchical state or feudalism, feudal territory ruled by a prince or princess. It can be either a sovereign state or a constituent part of a larger political entity. The term "prin ...

under the protection of the Ottoman Empire. The attempt, at first encouraged by the Porte, as a reply to the projected creation of an Armenian state under the suzerainty of Russia, collapsed after Obaidullah's raid into Persia, when various circumstances led the central government to reassert its supreme authority. Until the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 there had been little hostile feeling between the Kurds and the Armenians, and as late as 1877–1878 the mountaineers of both races had co-existed fairly well together.

In 1891 the activity of the Armenian Committees induced the Porte to strengthen the position of the Kurds by raising a body of Kurdish irregular cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

, which was well-armed and called Hamidieh after the Sultan Abd-ul-Hamid II. Minor disturbances constantly occurred, and were soon followed by the massacre of Armenians at Sasun and other places, 1894–1896, in which the Kurds took an active part. Some of the Kurds, like the nationalist Armenians, aimed to establish a Kurdish country.

A major development for Kurdish nationalism in the late Ottoman Empire was the foundation of the "Kurdistan" newspaper in 1898, based in Cairo. With the aim of spreading Kurdish cultural and nationalist ideas, seeking to unify Kurds and foster a national consciousness. Additionally, as a result of the successes of the Young Turk movement in 1908, many minorities in the Empire were, initially, allowed to create their own political organizations. Some notable Kurdish organizations were the Kurdish Society for Cooperation and Progress (KTTC), Hewa, and the Society for the Rise of Kurdistan (SAK). These groups fostered the growth of an educated elite for Kurdish nationalism. However, the majority of the Kurds did not support these aspirations, as many tribal leaders saw it as a threat to their own authority.

Jews

Early Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II established the Hakham Bashi, as the Rabbi of a particular region, with theHakham Bashi

''Hakham Bashi - חכם באשי'' (, , ; ; translated into French as: khakham-bachi) is the Turkish name for the Chief Rabbi of the nation's History of the Jews in Turkey, Jewish community. In the time of the Ottoman Empire it was also used for ...

of Constantinople being the most powerful.

In 1492, Sultan Bayezeid II ordered governors of Ottoman provinces to accept Jewish immigration and to do so cordially. This order was in response to the Alhambra Decree

The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Decreto de la Alhambra'', ''Edicto de Granada'') was an edict issued on 31 March 1492 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdi ...

, that ordered for the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

. This resulted in many Jewish refugees, and due to the high level of freedom enjoyed by Ottoman Jews, many looked to immigrate to Ottoman territory. In 1492 alone, roughly 60,000 Jews arrived in the Ottoman Empire.

The Ottomans took control of Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

from the Mamluk Empire in 1516, though during this time, there was no entity called "Palestine." There was a continuous Jewish population in the area due to the religious significance and significant holy sites to all Abrahamic religion

The term Abrahamic religions is used to group together monotheistic religions revering the Biblical figure Abraham, namely Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The religions share doctrinal, historical, and geographic overlap that contrasts them wit ...

s. Aliyah

''Aliyah'' (, ; ''ʿălīyyā'', ) is the immigration of Jews from Jewish diaspora, the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel or the Palestine (region), Palestine region, which is today chiefly represented by the Israel ...

, or Jewish immigration to Palestine, accelerated with the First Aliyah

The First Aliyah (), also known as the agriculture Aliyah, was a major wave of Jewish immigration (''aliyah'') to History of Israel#Ottoman period , Ottoman Palestine (region) , Palestine between 1881 and 1903. Jews who migrated in this wave cam ...

in 1882, largely triggered by pogroms

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century attacks on Jews i ...

in Tsarist Russia.

Zionist Movement

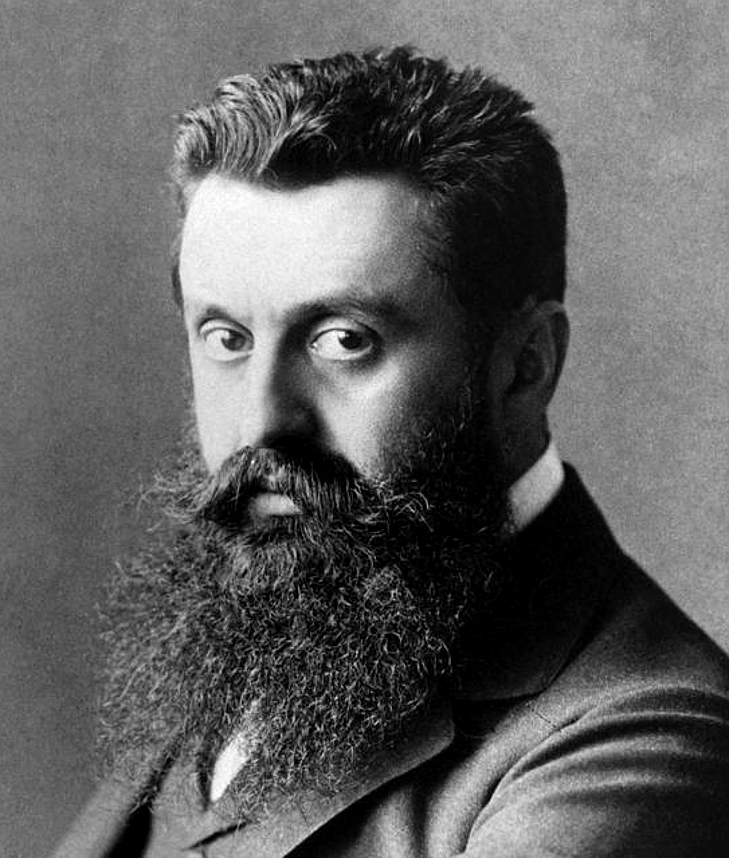

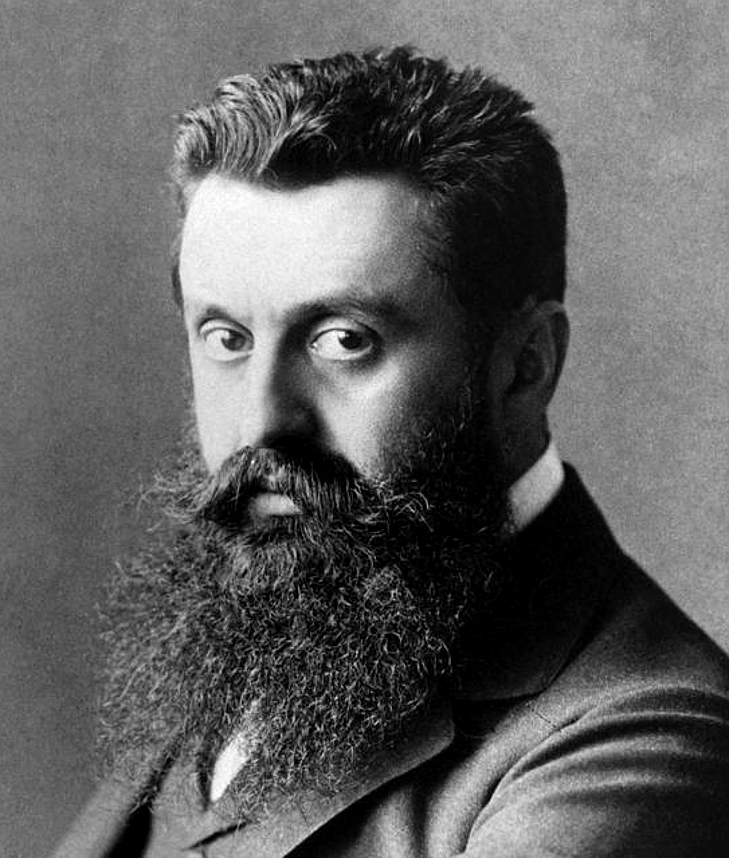

While the Ottoman Empire became a safe space for Jews, parts of Europe saw increased violence and anti-semitism against Jews. Violent uprisings against Jews took place all over Eastern Europe in the Late 19th century, and the civil rights of Jews were extremely limited.

Zionism is an international

While the Ottoman Empire became a safe space for Jews, parts of Europe saw increased violence and anti-semitism against Jews. Violent uprisings against Jews took place all over Eastern Europe in the Late 19th century, and the civil rights of Jews were extremely limited.

Zionism is an international political movement

A political movement is a collective attempt by a group of people to change government policy or social values. Political movements are usually in opposition to an element of the status quo, and are often associated with a certain ideology. Some t ...

; although started outside the Ottoman Empire, Zionism regards the Jews as a national entity and seeks to preserve that entity. This has primarily focused on the creation of a homeland for the Jewish People in the Promised Land

In the Abrahamic religions, the "Promised Land" ( ) refers to a swath of territory in the Levant that was bestowed upon Abraham and his descendants by God in Abrahamic religions, God. In the context of the Bible, these descendants are originally ...

, and (having achieved this goal) continues as support for the modern state of Israel.

Although its origins are earlier, the movement became better organized and more closely linked with the imperial powers of the day following the involvement of the late 19th century Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

Jewish journalist Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

, who is often credited as the father of the Zionist movement. Herzl He formed the World Zionist Organization and called for the First Zionist Congress

The First Zionist Congress () was the inaugural congress of the Zionist Organization, Zionist Organization (ZO) held in the Stadtcasino Basel in the city of Basel on August 29–31, 1897. Two hundred and eight delegates from 17 countries and 2 ...

in 1897. The movement was eventually successful in establishing Israel in 1948, as the world's first and only modern Jewish State

In world politics, Jewish state is a characterization of Israel as the nation-state and sovereign homeland for the Jewish people.

Overview

Modern Israel came into existence on 14 May 1948 as a polity to serve as the homeland for the Jewi ...

. Described as a "diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of birth, place of origin. The word is used in reference to people who identify with a specific geographic location, but currently resi ...

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

," its proponents regard it as a national liberation movement

A liberation movement is an organization or political movement leading a rebellion, or a non-violent social movement, against a colonial power or national government, often seeking independence based on a nationalist identity and an anti-imperiali ...

whose aim is the self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

of the Jewish people.

The objective of Zionism grew into the desire to form a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Early in the movement, there were many competing theories regarding the best avenue to achieve Jewish autonomy. The Jewish Territorial Organization represented a popular proposal. The organization supported finding a location, besides Palestine, for Jewish settlement.

Non-territorial autonomy was another popular theory. This was a principle that allowed for groups to self govern themselves without their own state. The Millet system in the Ottoman Empire allowed for this and was used by Orthodox Christians, Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

, and even Jews. This gave Jews significant legislative and governing powers in the Ottoman Empire. Jews weren't on the same social hierarchy as Muslims in the Ottoman Empire, however, they still enjoyed many protections as they were considered people of the book. This relative autonomy allowed for the formation of many Jewish ideas and practices, increasing the common identity.

As the goal of the Zionist movement grew, many Jews already living in the Ottoman Empire wanted to leverage their relative autonomy into settlement of Palestine. Eventually, the form of Zionism with Palestine as the intended homeland prevailed among the competing theories. Palestine was chosen due to the religious and historical significance of the region. Also, the declining power and financial struggles of the Ottoman Empire were seen as an opportunity. Wealthy and powerful Jews began to put their ideas into action.

Jewish Settling of Palestine

''See Also'':First Aliyah

The First Aliyah (), also known as the agriculture Aliyah, was a major wave of Jewish immigration (''aliyah'') to History of Israel#Ottoman period , Ottoman Palestine (region) , Palestine between 1881 and 1903. Jews who migrated in this wave cam ...

, Second Aliyah

The Second Aliyah () was an aliyah (Jewish immigration to the Land of Israel) that took place between 1904 and 1914, during which approximately 35,000 Jews, mostly from Russia, with some from Yemen, immigrated into Ottoman Palestine.

The Sec ...

Herzl founded the Jewish-Ottoman Land Company. Its objective was to acquire land in Palestine, for the settlement of Jews, through political channels with the Ottoman Empire. Herzl repeatedly visited Istanbul and engaged in negotiations and meetings with Ottoman officials. In 1901, Herzl was able to have a meeting with Sultan Abdul Hamid and insinuated that he had access to Jewish credit and that he could help the Ottoman Empire pay off debt. The company was initially successful, however, it eventually faced opposition from Arabs and the government.

The Jewish National Fund functioned similarly. It was a fund directed for land purchasing in Palestine. By 1921, around 25,000 acres had been purchased by the Fund in Palestine. Immigration of Jewish people into Palestine in 4 periods or Aliyahs. The first took place between 1881 and 1903, resulting in around 25,000 immigrating. The second took place between 1904 and 1914, resulting in around 35,000 Jews immigrating.

The increased Jewish population and Jewish land in Israel furthered the formation of a Jewish national identity. As the population and property owned by Jews increased in Palestine, support and backing continued to grow. However, so did tensions with other groups, especially Muslim Arabs. Arabs saw the massive Jewish immigration and financial interest in the region as threatening.

The Jewish National Fund functioned similarly. It was a fund directed for land purchasing in Palestine. By 1921, around 25,000 acres had been purchased by the Fund in Palestine. Immigration of Jewish people into Palestine in 4 periods or Aliyahs. The first took place between 1881 and 1903, resulting in around 25,000 immigrating. The second took place between 1904 and 1914, resulting in around 35,000 Jews immigrating.

The increased Jewish population and Jewish land in Israel furthered the formation of a Jewish national identity. As the population and property owned by Jews increased in Palestine, support and backing continued to grow. However, so did tensions with other groups, especially Muslim Arabs. Arabs saw the massive Jewish immigration and financial interest in the region as threatening.

Revival of Hebrew

Part of this movement included the revival of theHebrew Language

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and remained in regular use as a first language unti ...

. Hebrew had been spoken traditionally by the Israelites but was estimated to die out at as a spoken language around 200 CE. However, Jewish people continued to use the language for writing and prayer purposes. Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, an early member of the Zionist movement, immigrated to Ottoman controlled Palestine in 1881. Ben-Yehuda believed that the modern development of Hebrew wasn't feasible unless it was linked to Zionism. Hebrew quickly was picked up among the Jewish community in Palestine and became a part of the Jewish identity.

Outside of Palestine

Areas in the Ottoman Empire, besides Palestine, contained significant Jewish presence. Iraq, Tunisia, Turkey, Greece, and Egypt all had large and formidable Jewish populations. Most of these populations could trace their lineage in these areas back thousands of years to biblical times.Turkey

Bursa

Bursa () is a city in northwestern Turkey and the administrative center of Bursa Province. The fourth-most populous city in Turkey and second-most populous in the Marmara Region, Bursa is one of the industrial centers of the country. Most of ...

was one of the first cities with a Jewish population conquered by the Ottomans when it was conquered in 1324. The Jewish inhabitants helped the Ottoman army, and they were allowed to return to the city. The Ottomans then granted the Jewish people a certain level of autonomy. This early interaction helped set the standard for Ottoman-Jewish interaction throughout the remainder of Ottoman rule.

Istanbul quickly became a cultural center for Jews in the Near East. Jews were able to prosper in many high-skill fields, such as the medical field. This elevated social status resulted in even more freedom and the ability to solidify Jewish identities.

Iraq

The Siege of Baghdad in 1258 by the Mongols led to the ruin ofBaghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

and end of the Abbasid Dynasty

The Abbasid dynasty or Abbasids () were an Arab dynasty that ruled the Abbasid Caliphate between 750 and 1258. They were from the Qurayshi Hashimid clan of Banu Abbas, descended from Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib. The Abbasid Caliphate is divid ...

. Baghdad was left depopulated and many surviving residents left and moved elsewhere. In 1534, the Ottomans captured Baghdad from the Persians. Baghdad had not seen a strong Jewish population since before the Mongol raid. Many Jewish communities existed in small, isolated areas around Mesopotamia at the time. However, a resurgence in the Jewish population was seen in Baghdad after the Ottoman capture. Jews from Kurdistan, Syria, and Persia began to migrate back into Baghdad. Zvi Yehuda refers to this as the "new Babylonian Diaspora." Jewish population and strength continued to grow in Iraq in the following centuries. In 1900, around 50,000 Jews lived in Baghdad, making up nearly a quarter of its population. Jews played very important roles in Iraqi life and culture. The first Minister of Finance in Iraq, Sassoon Eskell

Sir Sassoon Eskell, Order of the British Empire, KBE (; ; 17 March 1860 – 31 August 1932), also known as Sassoon Effendi was an Iraqi statesman, politician and financier. He is regarded in Iraq as the Father of Parliament. Eskell was the first ...

, was even Jewish. Baghdad and other Iraqi cities were able to function as a Jewish cultural and religious hub throughout Ottoman rule. This freedom and autonomy helped for the development of a strong national Jewish ideology.

Syria

Jewish roots in Syria can date back to Biblical times, and strong Jewish communities have been present in the region since Roman rule. An influx of Jewish settlers came to Syria after the Alhambra Decree in 1492. Aleppo and Damascus were two main centers. Qamishli, a Kurdish town, also became a popular destination. The Aleppo Codex, a manuscript of the Hebrew Bible written inTiberias

Tiberias ( ; , ; ) is a city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in northern Israel. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Heb ...

, was kept at the Central Synagogue of Aleppo for nearly 600 years of Ottoman Rule. The synagogue was believed by some to have initially been constructed around 1000 BCE by Joab ben Zeruiah, the nephew and General of King David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Damas ...

's army. Inscriptions in the Synagogue date back to 834 CE. The heavy migration of Spanish and Italian Jews into Syria resulted in tension between Jewish groups already in the country. This tension was caused by differences in practices and languages. Many of the new residents spoke different languages, especially the Spanish. However, as generations passed, the descendants of Spanish and Italian settlers began to use these languages less and less. Jews continued to rise in status and power in Syria during Ottoman rule. Many Christians held angst against the rapidly increasing Jewish class causing poor relations between the two groups.

Greece

Salonika, or Thessaloniki, was a major Jewish center known as the "Jerusalem of the Balkans," "Mother of Israel" and a "Sephardic Metropolis," a site of Jewish refuge for Sephardim and Ashkenazim alike. ManySephardic

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

Jews came to Thessaloniki after their expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492. The vast Sephardic immigration allowed Thessaloniki to be a hub for diverse Jewish ideas. This large presence and advancement of Jews served as a strong national symbol of Jewish prosperity. Jews in Thessaloniki enjoyed a strategic and important location as a port in the Trans-Mediterranean trade network. 19th and 20th century Thessaloniki is commonly referred to as the "Golden Age", especially for its Jewish inhabitants. The success and prosperity enjoyed by Thessaloniki began to be used as an example of a Jewish state and proof that the concept would succeed.

Synagogues

An important aspect of forming a national Jewish identity, especially based on religion, was the construction of Synagogues. The Jewish houses of worship allowed Jews to congregate in worship and share their ideas and beliefs. Many synagogues were constructed or rebuilt during Ottoman rule. The Bet Yaakov Synagogue was constructed in Istanbul in 1878. The Ahrida Synagogue is an extremely notable one built in Istanbul in the 1430s. It is located in the Balat area of Istanbul, a formerly vibrant Jewish area. These synagogues were able to function as the cultural center within their own communities.

An important aspect of forming a national Jewish identity, especially based on religion, was the construction of Synagogues. The Jewish houses of worship allowed Jews to congregate in worship and share their ideas and beliefs. Many synagogues were constructed or rebuilt during Ottoman rule. The Bet Yaakov Synagogue was constructed in Istanbul in 1878. The Ahrida Synagogue is an extremely notable one built in Istanbul in the 1430s. It is located in the Balat area of Istanbul, a formerly vibrant Jewish area. These synagogues were able to function as the cultural center within their own communities.

Macedonians

The national awakening of the Macedonians can be said to have begun in the late 19th century; this is the time of the first expressions ofethnic nationalism

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric (and in some cases an ethnostate/ethnocratic) approach to variou ...

by limited groups of intellectuals in Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

, Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

, Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

and St. Petersburg. The " Macedonian Question" became especially prominent after the Balkan wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

in 1912–1913 and the subsequent division of the Ottoman Macedonia between three neighboring Christian states, followed by tensions between them over its possession. In order to legitimize their claims, each of these countries tried to 'persuade' the population into allegiance. The Macedonist ideas grew in significance after the First World War, both in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and among the left-leaning diaspora in the Kingdom of Bulgaria, and were endorsed by the Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

.

Montenegrins