Richard Roose on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard Roose (also known as Richard Rouse, Richard Cooke or Richard Rose) was accused in early 1531 of poisoning members of the household of the Englishman

The scholar Derek Wilson describes a "shock wave of horror" descending on the wealthy class of London and Westminster as news of the poisonings spread. Chapuys, writing to the Emperor in early March 1531, stated that it was as yet unknown who had provided Roose with the poison. Rex also argues that Roose was more likely a pawn in another's game, and had been unknowingly tricked into committing the crime. Chapuys believed Roose to have been Fisher's own cook, while the act of parliament noted only that he was a cook by occupation and from Rochester. Many details of both the chronology and the case against Roose have been lost in the centuries since, with the most thorough extant source being the act of parliament.

The scholar Derek Wilson describes a "shock wave of horror" descending on the wealthy class of London and Westminster as news of the poisonings spread. Chapuys, writing to the Emperor in early March 1531, stated that it was as yet unknown who had provided Roose with the poison. Rex also argues that Roose was more likely a pawn in another's game, and had been unknowingly tricked into committing the crime. Chapuys believed Roose to have been Fisher's own cook, while the act of parliament noted only that he was a cook by occupation and from Rochester. Many details of both the chronology and the case against Roose have been lost in the centuries since, with the most thorough extant source being the act of parliament.

What studied torments, tyrant, hast for me?

What wheels, racks, fires? What flaying? Boiling

In leads or oils? What old or newer torture

Must I receive...

Poison, argues Bellany, was a popular motif among Shakespeare and his contemporaries as it tapped into a basic fear of the unknown, and poisoning stories were so often about more than merely the crime itself:

Roose's attempt to poison Fisher is portrayed in the first episode of the second series of ''

John Fisher

John Fisher (c. 19 October 1469 – 22 June 1535) was an English Catholic prelate who served as Bishop of Rochester from 1504 to 1535 and as chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He is honoured as a martyr and saint by the Catholic Chu ...

, Bishop of Rochester

The Bishop of Rochester is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Rochester in the Province of Canterbury.

The town of Rochester, Kent, Rochester has the bishop's seat, at the Rochester Cathedral, Cathedral Chur ...

, for which he was boiled to death. Nothing is known of Roose (including his real name) or his life outside the case; he may have been Fisher's household cook, or less likely, a friend of the cook, at Fisher's residence in Lambeth.

Roose was accused of adding a white powder to porridge

Porridge is a food made by heating, soaking or boiling ground, crushed or chopped starchy plants, typically grain, in milk or water. It is often cooked or served with added flavourings such as sugar, honey, fruit, or syrup to make a sweet cereal ...

given to Fisher's dining guests and servants, as well as beggars to whom the food was given as charity. Two people—a member of Fisher's household, Burnet Curwen, and a beggar

Begging (also known in North America as panhandling) is the practice of imploring others to grant a favor, often a gift of money, with little or no expectation of reciprocation. A person doing such is called a beggar or panhandler. Beggars m ...

, Alice Tryppyt—died. Roose claimed that he had been given the powder by a stranger and claimed it was intended to be a joke—believing he was incapacitating his fellow servants rather than killing anyone. Fisher survived the poisoning

Poisoning is the harmful effect which occurs when Toxicity, toxic substances are introduced into the body. The term "poisoning" is a derivative of poison, a term describing any chemical substance that may harm or kill a living organism upon ...

as, for an unknown reason, he fasted that day. Roose was arrested and tortured for information. King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

—who already had a morbid fear of poisoning—addressed the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

on the case and was probably responsible for an act of parliament which attainted

In English criminal law, attainder was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditary titles, but ...

Roose and retroactively made murder by poison a treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

ous offence mandating execution by boiling. Roose was boiled to death at London's Smithfield in April 1532.

Fisher was already unpopular with the King as Henry wished to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine,

historical Spanish: , now: ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the Wives of Henry VIII, first wife of King Henry VIII from their marr ...

to marry Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the Wives of Henry VIII, second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and execution, by beheading ...

, an act the Church forbade. Fisher was vociferous both in his defence of Catherine and attacks on Boleyn, and contemporaries rumoured that the poisoning at Lambeth could have been either her or her father's responsibility, with or without the knowledge of the King. There appears to have been at least one other attempt on Fisher's life when a cannon was fired towards Fisher's residence from the direction of Anne's father, Thomas, Earl of Wiltshire's, house in London; on this occasion, no-one was hurt, but much damage was done to the roof. These two attacks, and Roose's execution, seem to have prompted Fisher to leave London before the end of the sitting parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, to the King's advantage.

Fisher was put to death in 1535 for his opposition to the Acts of Supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the En ...

that established the English monarch as head of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. Henry eventually broke with the Catholic Church and married Boleyn, but his new Act against Poisoning did not long outlive him, as it was repealed almost immediately by his son Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

. The Roose case continued to foment popular imagination and was still being cited in law into the next century. Historians often consider his execution as a watershed in the history of attainder

In English criminal law, attainder was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditary titles, but ...

, which traditionally acted as a corollary to common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

rather than replacing it. It was a direct precursor to the treason attainders that were to underpin the Tudors'—and particularly Henry's—destruction of political and religious enemies.

Position at court

King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

had become enamoured with one of his first wife's ladies-in-waiting

A lady-in-waiting (alternatively written lady in waiting) or court lady is a female personal assistant at a court, attending on a royal woman or a high-ranking noblewoman. Historically, in Europe, a lady-in-waiting was often a noblewoman but ...

since 1525, but Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the Wives of Henry VIII, second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and execution, by beheading ...

refused to sleep with the King before marriage. As a result, Henry had been trying to persuade both the Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the pope was the sovereign or head of sta ...

and the English Church to grant him a divorce in order that he might marry Boleyn. Few of the leading churchmen of the day supported Henry, and some, such as John Fisher

John Fisher (c. 19 October 1469 – 22 June 1535) was an English Catholic prelate who served as Bishop of Rochester from 1504 to 1535 and as chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He is honoured as a martyr and saint by the Catholic Chu ...

, Bishop of Rochester

The Bishop of Rochester is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Rochester in the Province of Canterbury.

The town of Rochester, Kent, Rochester has the bishop's seat, at the Rochester Cathedral, Cathedral Chur ...

, were vocal opponents of the royal plans. Fisher was not popular politically, though, and the historian J. J. Scarisbrick

John Joseph Scarisbrick is a British historian who taught at the University of Warwick. He is also noted as the co-founder with his wife Nuala Scarisbrick of Life (UK organisation), Life, a British anti-abortion movements, anti-abortion charity f ...

suggests that by 1531, Fisher could count both Henry and Boleyn—and her broader family—among his enemies.

By early 1531, the Reformation Parliament—described by the historian Stanford Lehmberg

Stanford E. Lehmberg (1931 – June 14, 2012) was an American historian and professor.

Early life and schooling

Stanford E. Lehmberg was born in McPherson, Kansas on 23 September 1931. Lehmberg's father was a Kansas dealer in farm implements, who ...

as one of England's most important ever—had been sitting for over a year. It had already passed a number of small but significant acts, both against perceived social ills—such as vagabondage—and the church, for example restricting recourse to praemunire

In English history, or ( or ) was the assertion or maintenance of papal jurisdiction, or any other foreign jurisdiction or claim of supremacy in England, against the supremacy of the monarch. The 14th-century law prohibiting this was enforced ...

. Although various laws had sought to restrict appeal to church courts since the 14th century, this was generally on limited terms against a small number of clergy in individual cases. By 1531, however, it was being used wholesale against the English clergy, who were effectively condemned for over-ruling the King's law by possessing their own jurisdictions as well as providing the right of sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred space, sacred place, such as a shrine, protected by ecclesiastical immunity. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This seconda ...

. The ambassador from the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, Eustace Chapuys

Eustace Chapuys (; c. 1489/90/92 – 21 January 1556) was a Savoyard diplomat who served as Imperial ambassador to England from 1529 until 1545 under Charles V. He is best known for his extensive and detailed correspondence.

Early life and edu ...

, wrote to his master, the Emperor Charles V

Charles V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (as Charles I) from 1516 to 1556, and Lord of the Netherlands as titular Duke of Burgundy (as Charles II) fr ...

, that Fisher was unpopular with the King prior to the deaths, and reported that parties unnamed but close to the King had threatened to throw Fisher and his followers into the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

if he continued his opposition. The historian G. W. Bernard has speculated that Fisher was deliberately intimidated, and notes that there were several suggestive incidents during these months. In January 1531, Fisher was briefly arrested for praemunire, for example, and two months later he was made physically ill at Wiltshire's boast that he could legally, and backed by scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They often feature a compilation or discussion of beliefs, ritual practices, moral commandments and ...

, disprove the theory of Papal primacy

Papal primacy, also known as the primacy of the bishop of Rome, is an ecclesiological doctrine in the Catholic Church concerning the respect and authority that is due to the pope from other bishops and their episcopal sees. While the doctri ...

.

The suspicion at court and the passion with which Fisher defended Catherine of Aragon angered both Henry and Boleyn, who, Chapuys reported, "feared no-one in England more than Fisher, because he had always defended atherinewithout respect of persons". Around this time, she advised Fisher not to attend parliament—where he was expected to condemn the King and his mistress—in case, Boleyn suggested, Fisher "caught some disease as he had before". The historian Maria Dowling classes this as a threat, albeit a veiled one. In the event, Fisher ignored her and her advice and attended parliament as intended. Attempts had been made to persuade Fisher by force of argument—the most recent had been the previous June in a disputation

Disputation is a genre of literature involving two contenders who seek to establish a resolution to a problem or establish the superiority of something. An example of the latter is in Sumerian disputation poems.

In the scholastic system of e ...

between Fisher and John Stokesley

John Stokesley (8 September 1475 – 8 September 1539) was an English clergyman who was Bishop of London during the reign of Henry VIII.

Life

Stokesley was born at Collyweston in Northamptonshire, and became a fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford ...

, Bishop of London

The bishop of London is the Ordinary (church officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury. By custom the Bishop is also Dean of the Chapel Royal since 1723.

The diocese covers of 17 boroughs o ...

but nothing had come of it. At least two historians believe that, as a result, Fisher's enemies became more proactive. Biographing Fisher in 2004, Richard Rex, argues that the failure of theological argument led to more proactive solutions being considered and Dowling agrees that Fisher's opponents moved towards physical force tactics.

Poisoning

Cases of deliberate, fatal poisoning were relatively rare in England, being known more by reputation than from experience. This was particularly so when compared with historically high-profile felonies such as rape and burglary, and it was considered an un-English crime. Although there was a genuine fear of poisoning among the upper classes—which led to elaborate food tasting rituals at formal feasts—food poisoning

Foodborne illness (also known as foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any illness resulting from the contamination of food by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites,

as well as prions (the agents of mad cow disease), and toxins such ...

from poor hygiene or misuse of natural ingredients was far more common an occurrence than deliberate poisoning with intent.

Poisonings of 18 February 1531

In the early afternoon of 18 February 1531 Fisher and guests were dining together at his episcopal London house inLambeth Marsh

Lambeth Marsh (also Lower Marsh and Lambeth Marshe) is one of the oldest settlements on the South Bank of London, England.

Until the early 19th century much of north Lambeth (now known as the South Bank) was mostly marsh. The settlement of La ...

, southwest of the city. A later act of parliament described the official account of events, stating that

It is possible that Roose was a friend of Fisher's cook, rather than the cook himself. The legal historian Krista Kesselring notes that the earliest reports of the attack—including the act of parliament, but also the letters of the Spanish and Venetian ambassadors of the day—all refer to him as being the cook. Nothing is known of his life or career until the events of 1531.

A member of Fisher's household, Benett (or possibly Burnet) Curwen, called a gentleman, and a woman who had come to the kitchens seeking alms

Alms (, ) are money, food, or other material goods donated to people living in poverty. Providing alms is often considered an act of Charity (practice), charity. The act of providing alms is called almsgiving.

Etymology

The word ''alms'' come ...

called Alice Tryppyt, had eaten a pottage

Pottage or potage (, ; ) is a term for a thick soup or stew made by boiling vegetables, grains, and, if available, meat or fish. It was a staple food for many centuries. The word ''pottage'' comes from the same Old French root as ''potage'', w ...

or porridge

Porridge is a food made by heating, soaking or boiling ground, crushed or chopped starchy plants, typically grain, in milk or water. It is often cooked or served with added flavourings such as sugar, honey, fruit, or syrup to make a sweet cereal ...

, and became "mortally enfected", the later parliamentary report said. Fisher, who had not partaken of the dish, survived, but about 17 people were violently ill. The victims included both members of his dining party that day and the poor who regularly came to beg charity from his kitchen door. The later act of parliament, from where most detail of the crime is drawn, was unclear on the precise number of people affected by the poison. It is not known why Fisher did not eat; he may have been fasting. Fisher's first biographer, Richard Hall reports that Fisher had been studying so hard in his office that he lost his appetite and instructed his household to sup without him. His abstinence may also have been due, suggests Bernard, to Fisher's well known charitable practice of not eating before the supplicants at his door had; as a result, they played the accidental role of food tasters for the Bishop. Suspicion quickly fell upon the kitchen staff, and specifically upon Roose, whom Richard Fisher—the Bishop's brother and household steward—ordered arrested immediately. Roose, who by then seems to have escaped across London, was swiftly captured. He was questioned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

, where he was tortured on the rack

Rack or racks may refer to:

Storage, support and transportation

* Amp rack, a piece of furniture in which amplifiers are mounted

* Autorack or auto carrier, for transporting vehicles in freight trains

* Baker's rack, for bread and other bake ...

.

Theories

The scholar Derek Wilson describes a "shock wave of horror" descending on the wealthy class of London and Westminster as news of the poisonings spread. Chapuys, writing to the Emperor in early March 1531, stated that it was as yet unknown who had provided Roose with the poison. Rex also argues that Roose was more likely a pawn in another's game, and had been unknowingly tricked into committing the crime. Chapuys believed Roose to have been Fisher's own cook, while the act of parliament noted only that he was a cook by occupation and from Rochester. Many details of both the chronology and the case against Roose have been lost in the centuries since, with the most thorough extant source being the act of parliament.

The scholar Derek Wilson describes a "shock wave of horror" descending on the wealthy class of London and Westminster as news of the poisonings spread. Chapuys, writing to the Emperor in early March 1531, stated that it was as yet unknown who had provided Roose with the poison. Rex also argues that Roose was more likely a pawn in another's game, and had been unknowingly tricked into committing the crime. Chapuys believed Roose to have been Fisher's own cook, while the act of parliament noted only that he was a cook by occupation and from Rochester. Many details of both the chronology and the case against Roose have been lost in the centuries since, with the most thorough extant source being the act of parliament.

Misguided prank or accident

During his racking, Roose admitted to putting what he believed to have beenlaxative

Laxatives, purgatives, or aperients are substances that loosen stools and increase bowel movements. They are used to treat and prevent constipation.

Laxatives vary as to how they work and the side effects they may have. Certain stimulant, lubri ...

—he described it as "a certain venom or poison"—in the porridge pot as a joke. Bernard argues that an accident of this nature is by no means unthinkable. Roose himself claimed that the white powder would cause discomfort and illness but would not be fatal and that the intention was merely to '' tromper'' Fisher's servants with a purgative

Laxatives, purgatives, or aperients are substances that loosen stools and increase bowel movements. They are used to treat and prevent constipation.

Laxatives vary as to how they work and the side effects they may have. Certain stimulant, lubri ...

, a theory also supported by Chapuys at the time.

Roose persuaded by another

Bernard suggests Roose's confession raises questions: "was it more sinister than that? ...And if it was more than a prank that went disastrously wrong, was Fisher its intended victim?" Dowling notes that Roose failed to provide any information as to the instigators of the crime, despite being severely tortured. Chapuys himself expressed doubts as to Roose's supposed motivation, and the extant records do not indicate the process by which Richard Fisher or the authorities settled on Roose as the culprit in the first place, the bill merely stating thatAnother culprit poisoned the food

Hall—who provides a detailed and probably reasonably accurate account of the attack, albeit written some years later—also suggests that the culprit was not Roose himself, but rather "a certeyne naughty persone of a most damnable and wicked disposition" known to Roose and who visited the cook at his workplace. Hall, notes Bridgett, also relates the story of the buttery: in this, he suggested that this acquaintance had despatched Roose to fetch him more drink and while he was out of the room, poisoned the pottage, which suggestion Bernard supports.The King's plan

Bernard has also theorised that since Fisher had been a critic of the King in his Great Matter, Henry might have wanted to frighten—or even kill—the Bishop. The scholar John Matusiak argues that "no other critic of the divorce among the kingdom's elites would, in fact, be more outspoken and no opponent of the looming breach with Rome would be treated to such levels of intimidation" as Fisher until his 1535beheading

Decapitation is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and all vertebrate animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood by way of severing through the jugular vein and common ...

.

The King, though, comments Lehmberg, was disturbed at the news of Roose's crime, not only because of his own paranoia regarding poison but also perhaps fearful that he could be implicated. Chapuys appears to have at least suspected Henry of over-dramatising Roose's crime in a Machiavellian effort to distract attention from his and the Boleyns' own poor relations with the Bishop. Henry may also have been reacting to a popular rumour of his culpability. Such a rumour seems to have gained traction in parts of the country already ill-disposed to the Queen by parties in favour of remaining in the Roman church. It is likely that although Henry was determined to bring England's clergy directly under his control—as his laws against praemunire demonstrated—the situation had not yet worsened to the extent that he wanted to be seen as an open enemy of the church or its senior echelons.

Boleyn or her father's plan

Rex has suggested that Boleyn and her family, probably through agents, were at least as likely a culprit as the King. Chapuys originally suggested this possibility to the Emperor in his March letter, telling Charles that "the king has done well to show dissatisfaction at this; nevertheless, he cannot wholly avoid some suspicion, if not against himself, whom I think too good to do such a thing, at least against the lady and her father". The ambassador seems to have believed that, while it was unlikely that the king, being above such things, had been involved in the conspiracy, Boleyn was a different matter. The medievalist Alastair Bellany argues that, to contemporaries, while the involvement of the King in such an affair would have been incredible, "poisoning was a crime perfectly suited to an upstart courtier or an ambitious whore" such as she was portrayed by her enemies. The SpanishJesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

Pedro de Ribadeneira

Pedro de Ribadeneira (born Pedro Ortiz de Cisneros; 1 November 1527 – 10 September or 22 September 1611) was a Spanish hagiographer, Jesuit priest, companion of Ignatius of Loyola, and a Spanish Golden Age ascetic writer.

Life

Pedro was b ...

—writing in the 1590s—placed the blame firmly on Boleyn herself, writing how she had hated Rochester ever since he had taken up Catherine's cause so vigorously and her hatred inspired her to hire Roose to commit murder. It was, says de Ribadeneira, only God's will

The will of God or divine will is a concept found in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and a number of other texts and worldviews, according to which God's will is the cause of everything that exists.

Thomas Aquinas

According to Thomas Aquin ...

that the Bishop did not eat as he was presumably expected to, although he also believed, mistakenly, that all who partook of the pottage died. The historian Elizabeth Norton

Elizabeth Anna Norton is a British historian specialising in the queens of England and the Tudor period. She obtained a Master of Arts in archaeology and anthropology from the University of Cambridge, being awarded a Double First Class degree, ...

argues that while Boleyn was unlikely to have been guilty, the case demonstrates her unpopularity, in that, by some, "anything could be believed of her".

Legal proceedings

Condemnation

Roose was nottried

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, wh ...

for the crime, and so was unable to defend himself. While he was imprisoned, the King addressed the lords of parliament

A Lord of Parliament () was the holder of the lowest form of peerage, entitled as of right to take part in sessions of the pre-Act of Union 1707, Union Parliament of Scotland. Since that Union in 1707, it has been the lowest rank of the Peerag ...

on 28 February for an hour and a half, mostly on the poisonings, "in a lengthy speech expounding his love of justice and his zeal to protect his subjects and to maintain good order in the realm" comments the historian William R. Stacy.

Such a highly public response based on the King's opinions rather than legal basis,—was intended to emphasise Henry's virtues, particularly his care for his subjects and upholding of "God's peace". Roose was effectively condemned on the strength of Henry's interpretation of the events of 18 February rather than on evidence.

Bill expanding the definition of treason

Instead of being condemned by his peers, as would have been usual, Roose was judged by parliament. The final Bill was probably written by Henry's councillors—although its brevity indicates to Stacy that the King may have drafted it himself—and underwent adjustments before it was finally promulgated. An earlier draft, for example, did not name Roose's victims or call the offence treason (rather it was termed "voluntary murder"). Kesselring suggests the shift in emphasis from felony to treason stemmed from Henry's political desire to restrict the privilege ofbenefit of clergy

In English law, the benefit of clergy ( Law Latin: ''privilegium clericale'') was originally a provision by which clergymen accused of a crime could claim that they were outside the jurisdiction of the secular courts and be tried instead in an ec ...

. Fisher was a staunch defender of the privilege, and, she says, would have condemned the attack on him to further weaken his church's immunities. As a result, the "celebrated" ''An Acte for Poysonyng''—an example of knee-jerk legislation, according to the historian Robert Hutchinson—was passed. Indeed, Lehmberg suggests that however barbarous it seemed, the bill

''The Bill'' is a British police procedural television series, broadcast on ITV (TV network), ITV from 16 October 1984 until 31 August 2010. The programme originated from a one-off drama, "Woodentop (The Bill), Woodentop" (part of the ''Storyb ...

sailed through both Houses. The King, in his speech, emphasised that

Henry's essentially ''ad hoc'' augmentation of the Law of Treason has led historians to question his commitment to common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

. Stacy comments that "traditionally, treason legislation protected the person of the King and his immediate family, certain members of the government, and the coinage, but the public clause in Roose's attainder offered none of these increased security". Despite its cruelty, continues Stacy, it was useful for the King and Cromwell to have a law allowing the crown to dispose of its political enemies outside the usual mechanisms of law. Henry's legislation not only created several new capital statutes, with eleven expanding treason's legal definition. It effectively announced murder by poison to be a new phenomenon for the country and for the law, further depleting access to benefit of clergy.

An attainder

In English criminal law, attainder was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditary titles, but ...

was presented against Roose, which meant that he was found guilty with no common law proceedings being necessary even though, as a prisoner of the crown, there was no impediment to placing him on jury trial. As a result of the deaths at Fisher's house, parliament—probably at the King's insistence—ensured that the ''Acte'' determined that murder by poison would henceforth be treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

, to be punished by boiling alive. The Act specified that

The ''Acte'' was thus retroactive, in that the law which condemned Roose did not exist—poisoning not being classed as treason—when the crime was committed. Through the ''Acte'', Justices of the Peace and local assize

The assizes (), or courts of assize, were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes ex ...

s were given jurisdiction over treason, although this was effectively limited to coining and poisoning until later in the decade. With Roose, boiling as a form of execution was placed on the statute book.

Execution

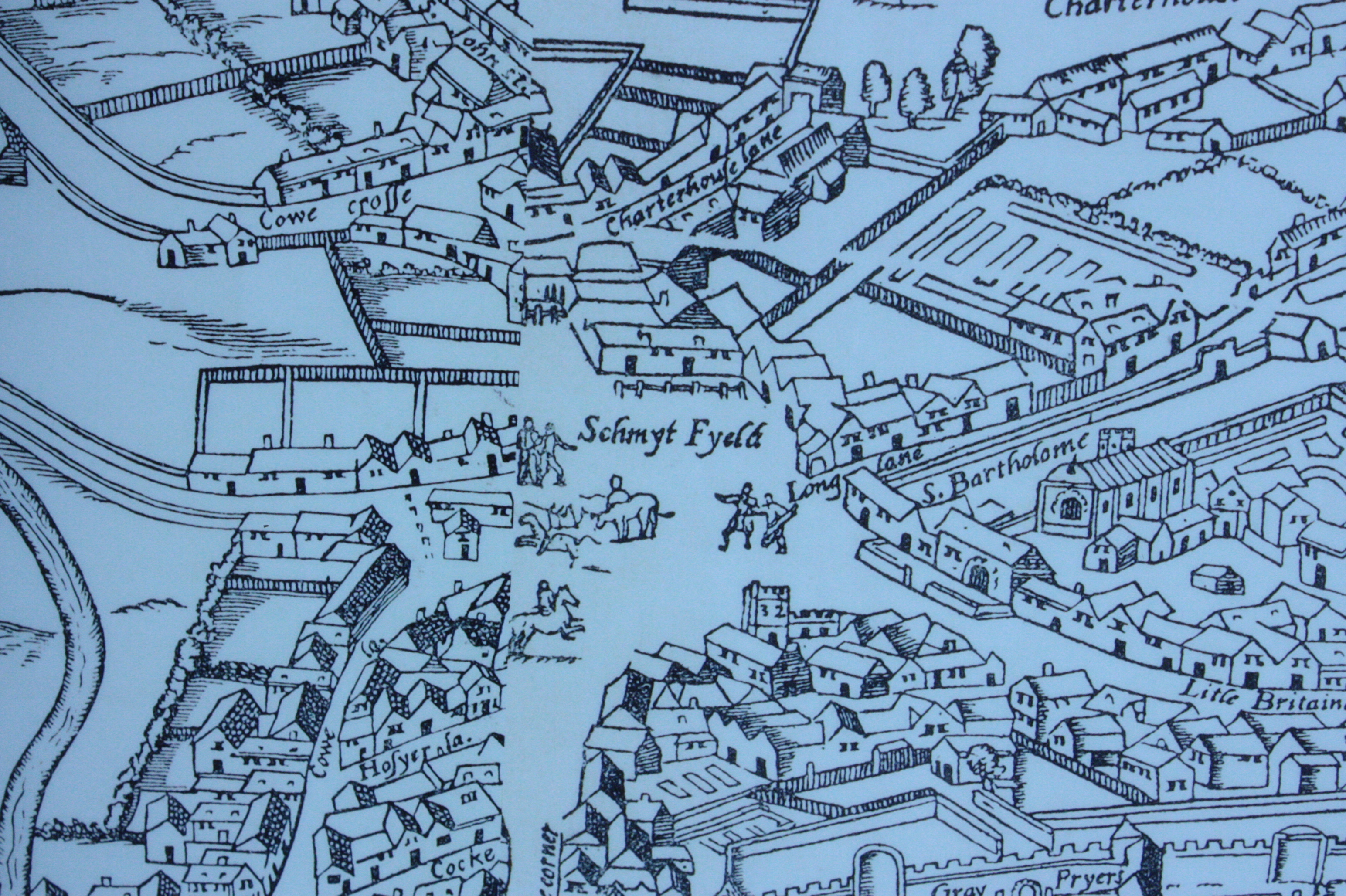

In a symbolism-laden ritual intending to publicly demonstrate the crown's commitment to law and order, Roose's boiling took place publicly at Smithfield on 15 April 1532. It took approximately two hours. The contemporary ''Chronicle of the Grey Friars of London

''The Greyfriars' Chronicle'' was a chronicle during the Tudor period. It was published in 1852 and was edited by J.G. Nichols. It documents political and religious events in and around London

London is the Capital city, capital and List ...

'' described how Roose was tied up in chains, gibbet

Gibbeting is the use of a gallows-type structure from which the dead or dying bodies of criminals were hanged on public display to deter other existing or potential criminals. Occasionally, the gibbet () was also used as a method of public ex ...

ed and then lowered in and out of the boiling water three times until he died. Stacy suggests that the symbolism of his boiling was not just a reference to Roose's trade, or out of a desire to simply cause him as much pain as possible; rather, it was carefully chosen to re-enact the crime itself, in which Roose boiled poison into the broth. This inextricably linked the crime with its punishment in the eyes of contemporaries. A Londoner described how Roose died:

Aftermath

Hall describes a curious event that took place shortly after the poisonings. Volleys of gunfire, probably from a cannon, were shot through the roof of Fisher's house, damaging rafters and slates. Fisher's study, which he was occupying at the time, was close by; Hall alleges that the shooting came from Wiltshire's Durham House almost directly across the Thames. However, it was some distance between the latter − on London'sStrand

Strand or The Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* ...

− and Fisher's house, Dowling remarks, while the Victorian antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic si ...

John Lewis calls the story "highly improbable". Scarisbrick noted the close timing between the two attacks, and suggested that the government or its agents may have been implicated in both of them, saying "we can make of that story what we will".

The main result, in Hall's words, was that Fisher "perceived that great malice was meant toward him", notes Bernard, and declared his intention to leave for Rochester immediately. Hall writes that Fisher, "callinge speedily certain of his servantes, said: 'Let us trusse up our geere and be gone from hence, for here is no place for us to tarri any longer. Chapuys reports that he departed London on 2 March.

Fisher had been ill ever since the clergy had accepted Henry's new title of Supreme Head of the Church, reported Chapuys, and was further "nauseated" by the treatment meted out to Roose. Fisher left for his diocese before the raising of the parliamentary session on 31 March. Chapuys speculated on Fisher's reasons for wishing to make such a long journey, especially as he would be closer to better medical assistance in the capital. The ambassador considered that either the Bishop no longer wished to witness the attacks on his church, or that "he fears that there is some more powder in store for him". Chapuys believed Fisher's escape from death to have been an act of God, who, he wrote, "no doubt considers ishervery useful and necessary in this world"; Hall also considered Fisher's survival a reflection on the Bishop's holiness. Chapuys suggested that Fisher's removal from Westminster would be harmful to his cause, writing to Charles that "if the King desired to treat of the affair of the Queen, the absence of the said Bishop ...would be unfortunate".

What Bellany calls the "English obsession" about poison continued, with hysteria over poisoning persisted for many years. Death by boiling, however, was used only once more as a method of execution, in March 1542 for another case of poisoning. On this occasion a maidservant, Margaret Davy, was executed in the same way for killing her master and mistress. The ''Acte'' was repealed in 1547 on the accession of Henry's son, Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

, whose first parliament described it as "very straight, sore, extreme, and terrible". The crime of poisoning was reclassified as a felony and thus subject to the more usual punishments: generally hanging for men and burning for women.

The scholar Miranda Wilson suggests that Roose's poison was ineffectual as a weapon in what she describes as a "botched and isolated attack". Had it succeeded though, argues Stacy, through the usual course of law, Roose could at most have been convicted of petty treason

Petty treason or petit treason was an offence under the common law of England in which a person killed or otherwise violated the authority of a social superior, other than the king. In England and Wales, petty treason ceased to be a distinct offe ...

. The King's reaction, says Bernard, was an extraordinary one, and he questions whether this indicates a guilty royal conscience, highlighting the extreme punishment. The change in the legal status of poisoning has been described by Lehmberg as the most interesting of all the adjustments to the legal code in 1531. Hutchinson has contrasted the rarity of the crime—which the ''Acte'' itself acknowledged—with the swiftness of the royal response to it.

Perception

Of contemporaries

The affair made a significant impact on contemporaries—modern historians have described Chapuys, for example, as viewing it as a "very extraordinary case", that was "fascinating, puzzling and instructive" to observers. The scholarSuzannah Lipscomb

Suzannah Rebecca Gabriella Lipscomb (born 7 December 1978)

, Library of Congress Name Authority File is a Britis ...

has noted that, whereas attempting to kill a Bishop in 1531 was punishable by a painful death, it was "an irony perhaps not lost on others four years later", when Fisher was sent to the block, also under the new treason laws. The case remained a ''cause celebre'' into the next century, and remained influential in , Library of Congress Name Authority File is a Britis ...

case law

Case law, also used interchangeably with common law, is a law that is based on precedents, that is the judicial decisions from previous cases, rather than law based on constitutions, statutes, or regulations. Case law uses the detailed facts of ...

, when Edward Coke

Sir Edward Coke ( , formerly ; 1 February 1552 – 3 September 1634) was an English barrister, judge, and politician. He is often considered the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan and Jacobean era, Jacobean eras.

Born into a ...

, Chief Justice under King James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

* James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

* James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

* James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334� ...

, said that the Poisoning Act was "too severe to live long".

In 1615, both Coke and Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

, during their prosecution of Robert Carr

Leonard Robert Carr, Baron Carr of Hadley, (11 November 1916 – 17 February 2012) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Home Secretary from 1972 to 1974. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for 26 years, and later s ...

and Frances Howard for the poisoning of Thomas Overbury, referred to the case several times. As Bellany notes, while the statute "had long been repealed, Bacon could still describe poisoning as a kind of treason" on account of his view that it was an attack on the body politic, charging that it was "grievous beyond other matters". Bacon argued that—as the Roose case demonstrated—poison can easily affect the innocent, and that often "men die other men's deaths". He also emphasised that the crime was not just against the person, but against society. Wilson suggests that "for Bacon, the 16th-century story of Roose retains both cultural currency and argumentative relevance in Jacobean England". Roose's attainder was also cited in the 1641 attainder of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford (13 April 1593 ( N.S.)12 May 1641), was an English statesman and a major figure in the period leading up to the English Civil War. He served in Parliament and was a supporter of King Charles I. From 16 ...

.

Poisoning was seen as an innovative form of crime to the English political class—A. F. Pollard

Albert Frederick Pollard (16 December 1869 – 3 August 1948) was a British historian who specialised in the Tudor period. He was one of the founders of the Historical Association in 1906.

Life and career

Pollard was born in Ryde on the ...

says that "however familiar poisoning might be at Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, it was a novel method in England"—while Wilson argues that the case "transformed oisoningfrom a bit part to a star performer". While contemporaries saw all murder as a crime against God and King, there was something about poisoning that made it worse, for it was against the social order ordained by God. Poison was seen as infecting not just the bodies of its victims, but the body politic

The body politic is a polity—such as a city, realm, or state—considered metaphorically as a physical body. Historically, the sovereign is typically portrayed as the body's head, and the analogy may also be extended to other anatomical part ...

generally. Stacy has argued that it was less the target of the attempted murder than the method used in doing so that worried contemporaries, and that it was this that accounts for both the elevation of Roose's crime to treason and the brutality with which it was punished. The cultural historian

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, attitudes, and habits of the individuals in these gr ...

Alison Sim comments that poison did not differentiate between rich or poor once ingested. The crime was also linked to the supernatural

Supernatural phenomena or entities are those beyond the Scientific law, laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin 'above, beyond, outside of' + 'nature'. Although the corollary term "nature" has had multiple meanin ...

in contemporary imagination: the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

'' veneficum'' translated both as poisoning and sorcery

Sorcery commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), the application of beliefs, rituals or actions employed to manipulate natural or supernatural beings and forces

** Goetia, ''Goetia'', magic involving the evocation of spirits

** Witchcraft, the ...

.

Of historians

Wilson argues that historians have under-examined Roose's case, except in the context of broader historiographies, such as that of attainder, law or the Henrician Reformation, while Stacy suggests that it has been overlooked in light of the great attainders that followed. It is also significant, Wilson says, as being the point where poisoning—both legally and in the popular imagination—"does acquire a vigorous cultural presence missing in earlier treatments". For example, he comments, the death of King John, popularly supposed to have been poisoned by a disgruntledfriar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders in the Catholic Church. There are also friars outside of the Catholic Church, such as within the Anglican Communion. The term, first used in the 12th or 13th century, distinguishes the mendi ...

, or the attempted poisoning in Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He ...

's '' Pardoner's Tale'' indicate how, in medieval England, the literature rarely "tend to dwell for long on the uses and dangers of poison in the world". Until Roose's execution, that is, when poison begins to become part of the cultural imagination. Bellany suggests that the case "starkly revealed the poisoner's unnerving power to subvert the order and betray the intimacies that bound household and community together", the former being viewed simply as a microcosm of the latter. The secrecy with which the lower-class could subvert their superior's authority, and the wider damage this was seen to do, explains why the ''Acte'' directly compares poisoning as a crime with that of coining, which harmed not just the individuals subject to the con, but the economy generally. The historian Penry Williams

Penry Williams (5 September 1866 – 26 June 1945) was a Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician in England, born in Middlesbrough, a son of Edward Williams, a Cleveland ironmaster, and brother of Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Me ...

suggests that the Roose case, and particularly the elevation of poisoning to a crime of high treason, is an example of a broader, more endemic, extension of capital offences under Henry VIII.

The Tudor historian Geoffrey Elton

Sir Geoffrey Rudolph Elton (born Gottfried Rudolf Otto Ehrenberg; 17 August 1921 – 4 December 1994) was a German-born British political and constitutional historian, specialising in the Tudor period. He taught at Clare College, Cambridge, and ...

suggested that the 1531 act "was in fact the dying echo of an older common law attitude which could at times be negligent of the real meaning" of attainder. Kesselring disputes this interpretation, arguing that, far from being an accidental throwback, the act deliberately intended to circumvent common law, so avoiding politically sensitive cases becoming dealt with by judges. She also questions why—notwithstanding pressure from the King to attaint Roose—parliament so easily agreed to his demand, or broadened the definition of treason as they did. It was not as if the change brought profit to Henry, as the act stipulated that forfeitures would go to the attainted man's lord, as was already the case with felony. This, the legal scholar John Bellamy suggests, may have been Henry's means of persuading the Lords to support the measure, as in most cases they could expect to receive the goods and chattels of the convicted. Bellamy considers, that although the act was an innovation in statute law, it still "managed to contain all the most obnoxious features of its varied predecessors". Elton argues that, in spite of its perceived brutality, Cromwell—and therefore Henry—had a firm belief in the mechanisms and formalities of the common law", except in "a few exceptional cases...where politics or he King'spersonal feelings played a major role". If the Roose attainder had been the only example of its kind, argues Stacy, it may only be seen, with hindsight, as an abnormal legal curiosity. But it was the first of several such circumventions of common law in Henry's reign, and calls into question, he says, whether the period should be seen as the age of legalism and due process

Due process of law is application by the state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to a case so all legal rights that are owed to a person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual p ...

, as Elton advocates.

Stacy, arguing that the Roose case is the first example of an attainder intended to avoid dependency on common law, states that although it has been overshadowed by subsequent higher profile individuals, it remained the legal precedent for those prosecutions. Although attainder was already a common parliamentary weapon for late-medieval English Kings, it was effectively a form of outlawry, usually used to supplement a common law verdict with the confiscation of land and wealth as its intended result. Lipscomb has argued though that not only were attainders increasingly used from the 1530s but that the decade shows the heaviest use of the mechanism in the whole of English history, while Stacy suggests that Henrician ministers resorted to the parliamentary attainder as a matter of routine rather than last resort. Attainders were popular with the King because they could take the place of common law rather than merely augment it, and thus avoided the necessity for evidential precision. The Roose attainder laid the groundwork for the famous treason attainders—from supposed heretics such as Elizabeth Barton

Elizabeth Barton (1506 – 20 April 1534), known as "The Nun of Kent", "The Holy Maid of London", "The Holy Maid of Kent" and later "The Mad Maid of Kent", was an English Catholic nun. She was executed as a result of her prophecies against the ...

to the "great state offenders" such as Fisher, Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

, Cromwell, Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

and two of Henry's own wives—that punctuated Henry's later reign.

Cultural depiction

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

referenced Roose's execution in ''The Winter's Tale

''The Winter's Tale'' is a play by William Shakespeare originally published in the First Folio of 1623. Although it was grouped among the comedies, many modern editors have relabelled the play as one of Shakespeare's late romances. Some criti ...

'' when the character of Paulina demands of King Leontes:

The Tudors

''The Tudors'' is a historical fiction television series set primarily in 16th-century England, created and written by Michael Hirst and produced for the American premium cable television channel Showtime. The series was a collaboration among ...

'', "Everything Is Beautiful", in 2008. Roose is played by Gary Murphy

Gary Murphy (born 15 October 1972) is an Irish professional golfer.

Career

Murphy was born in Kilkenny and began playing golf aged 11, after caddying for his father, Jim, who has played an instrumental role in the development of young golfers ...

in a "highly fictionalised" account of the case, in which the ultimate blame is placed on Wiltshire, played by Nick Dunning

Nick Dunning (born 1957 in London) is an English actor. His credits include '' The Young Ones'' (1982), ''Minder'' (1993), '' Boon'' (1995), ''Coronation Street'' (1998), ''Midsomer Murders'' episode '' Death's Shadow'' (1999), ''Kavanagh QC'' ...

—who provides the poison—with Roose his catspaw. The episode suggests that Roose is susceptible to bribery because he has three daughters for whom he wants good marriages. Having paid Roose to poison the soup, Wiltshire then threatens to exterminate the cook's family if he ever speaks of it again. Sir Thomas More takes the news of the poisoning to Henry, who becomes angry at the suggestion of Boleyn's involvement. Both Wiltshire and Cromwell witness what the critics Sue Parrill and William B. Robison have called the "particularly gruesome scene" where Roose is executed. Cromwell—despite having been shown the planner of the event—walks out halfway through. Hilary Mantel

Dame Hilary Mary Mantel ( ; born Thompson; 6 July 1952 – 22 September 2022) was a British writer whose work includes historical fiction, personal memoirs and short stories. Her first published novel, ''Every Day Is Mother's Day'', was releas ...

includes the poisoning in her fictional life of Thomas Cromwell, ''Wolf Hall

''Wolf Hall'' is a 2009 historical novel by English author Hilary Mantel, published by Fourth Estate, named after the Seymour family's seat of Wolfhall, or Wulfhall, in Wiltshire. Set in the period from 1500 to 1535, ''Wolf Hall'' is a sym ...

'', from whose perspective events are related. Without naming Roose personally, Mantel covers the poisoning and its environs in some detail. She has Cromwell discover that the broth was poisoned and realise it was the only dish that the victims had had in common that night, which is then confirmed by the serving boys. Cromwell, while understanding that "there are poisons nature herself brews", is in no doubt that a crime had been committed from the start. The cook, when captured, explains that "a man. A stranger who had said it would be a good joke" had given the cook the poison.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Roose, Richard Year of birth missing 1531 deaths Poisoners 16th-century English people British people executed for murder People executed under Henry VIII People executed by boiling Executed English people