Rhodesia And Nyasaland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

By the time Macmillan went on his famous 1960 African tour leading to his ''Wind of Change'' speech to

By the time Macmillan went on his famous 1960 African tour leading to his ''Wind of Change'' speech to

The Federation issued its first postage stamps in 1954, all with a portrait of

The Federation issued its first postage stamps in 1954, all with a portrait of

Window on Rhodesia

an archive of the history and life of Rhodesia * {{DEFAULTSORT:Federation of Rhodesia And Nyasaland 1950s in Northern Rhodesia 1950s in Nyasaland 1950s in Southern Rhodesia 1953 establishments in Africa 1953 establishments in Nyasaland 1953 establishments in Southern Rhodesia 1953 establishments in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland 1960s in Northern Rhodesia 1960s in Nyasaland 1960s in Rhodesia 1960s in Southern Rhodesia 1963 disestablishments in Africa 1963 disestablishments in Nyasaland 1963 disestablishments in Southern Rhodesia 1963 disestablishments in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland 20th century in Malawi 20th century in Rhodesia 20th century in Zambia 20th century in Zimbabwe English-speaking countries and territories Former British colonies and protectorates in Africa Former confederations Malawi–United Kingdom relations Northern Rhodesia Nyasaland Rhodesia–United Kingdom relations Southern Rhodesia States and territories disestablished in 1963 States and territories established in 1953 United Kingdom–Zambia relations United Kingdom–Zimbabwe relations

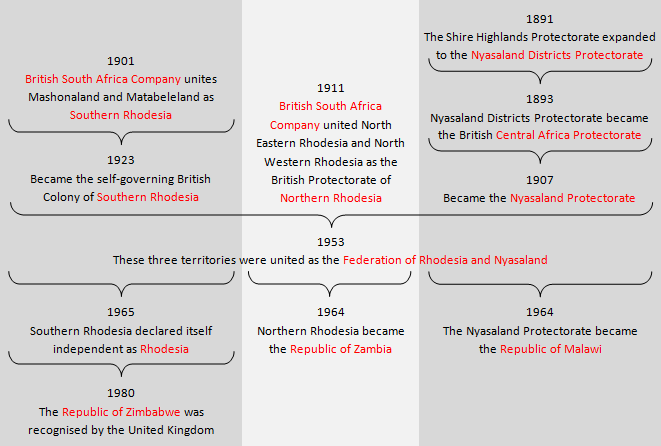

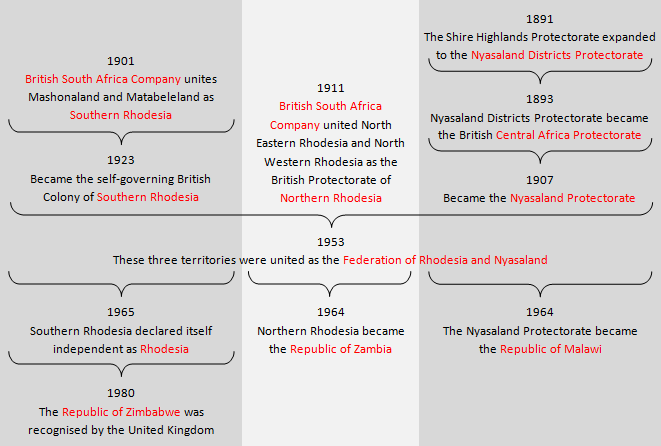

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also known as the Central African Federation (CAF), was a colonial

It was commonly understood that Southern Rhodesia would be the dominant territory in the federation economically, electorally, and militarily. How much so defined much of the lengthy constitutional negotiations and modifications that followed. African political opposition and

It was commonly understood that Southern Rhodesia would be the dominant territory in the federation economically, electorally, and militarily. How much so defined much of the lengthy constitutional negotiations and modifications that followed. African political opposition and

African dissent in the CAF grew, and at the same time British Government circles expressed objections to its structure and purpose full Commonwealth of Nations">Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

African dissent in the CAF grew, and at the same time British Government circles expressed objections to its structure and purpose full Commonwealth of Nations">Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

membership leading to independence as a dominion.

In June 1956, Northern Rhodesia's Governor of Northern Rhodesia, Governor, Arthur Benson, Sir Arthur Benson, wrote a highly confidential letter heavily criticising the federation in general (and the new constitution planned for it) and Federal Prime Minister, Roy Welensky, in particular. Nearly two years later, Lord Malvern (as Sir Godfrey Huggins had become in February 1955) somehow obtained a copy of it and disclosed its contents to Welensky.

Relations between federation

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

that consisted of three southern African territories: the self-governing British colony of Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South ...

and the British protectorate

British protectorates were protectorates under the jurisdiction of the British government. Many territories which became British protectorates already had local rulers with whom the Crown negotiated through treaty, acknowledging their status wh ...

s of Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in Southern Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by Amalgamation (politics), amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North ...

and Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. After ...

. It existed between 1953 and 1963. Rhodesia and Nyasaland bordered Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

(Portuguese province), Bechuanaland (British protectorate), Congo-Léopoldville ( Belgian colony before 1960), Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

(Portuguese province), South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, South West Africa

South West Africa was a territory under Union of South Africa, South African administration from 1915 to 1990. Renamed ''Namibia'' by the United Nations in 1968, Independence of Namibia, it became independent under this name on 21 March 1990. ...

(South African mandate) and Tanganyika ( British mandate before 1961).

The Federation was established on 1 August 1953, with a Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

as the Queen's representative at the centre. The constitutional status of the three territories a self-governing Colony and two Protectorates was not affected, though certain enactments applied to the Federation as a whole as if it were part of Her Majesty's dominions and a Colony. A novel feature was the African Affairs Board, set up to safeguard the interests of Africans and endowed with statutory powers for that purpose, particularly in regard to discriminatory legislation. The economic advantages to the Federation were never seriously called into question, and the causes of the Federation's failure were purely political: the strong and growing opposition of the African inhabitants. The rulers of the new black African states were united in wanting to end colonialism in Africa. With most of the world moving away from colonialism during the late 1950s and early 1960s, the United Kingdom was subjected to pressure to decolonise from both the United Nations and the Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; , OUA) was an African intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 33 signatory governments. Some of the key aims of the OAU were to encourage political and ec ...

(OAU). These groups supported the aspirations of the black African nationalists and accepted their claims to speak on behalf of the people.

The federation ended on 31 December 1963. In 1964, shortly after the dissolution, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland became independent under the names Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

and Malawi

Malawi, officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over and ...

, respectively. In November 1965, Southern Rhodesia unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom as the state of Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

.

History

Central African Council

In 1929, theHilton Young Commission

The Hilton Young Commission (complete title: Royal Commission on Indian Currency and Finance) was a Commission of Inquiry appointed in 1926 to look into the possible closer union of the British territories in East and Central Africa. These were in ...

concluded that "in the present state of communications the main interests of Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia, economic and political, lie not in association with the Eastern African Territories, but rather one another and with the self-governing Colony of Southern Rhodesia". In 1938, the Bledisloe Commission concluded that the territories would become interdependent in all their activities, but stopped short of recommending federation. Instead, it advised the creation of an inter-territorial council to coordinate government services and survey the development needs of the region. The Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

delayed the creation of this institution until 1945, when the Central African Council was established to promote coordination of policy and action between the territories. The Governor of Southern Rhodesia

The governor of Southern Rhodesia was the representative of the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British monarch in the self-governing colony of Southern Rhodesia from 1923 to 1980. The governor was appointed by the Crown and acted as the local ...

presided over the council and was joined by the leaders of the other two territories. The Council only had consultative, and not binding, powers.

Negotiations

In November 1950, Jim Griffiths, theSecretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

, informed the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

that the government had decided that there should be another examination of the possibility of a closer union between the Central African territories, and that a conference of the respective governments and the Central African Council was being arranged for March 1951. The conference concluded that there was a need for closer association, pointing to the economic interdependence of the three territories. It was argued that individually the territories were vulnerable and would benefit from becoming a single unit with a more broadly based economy. It was also said that unification of certain public services would promote greater efficiency. It was decided to recommend a federation under which the central government would have certain specific powers, with the residual powers being left with the territorial governments. Another conference was held in September 1951 at Victoria Falls

Victoria Falls (Lozi language, Lozi: ''Mosi-oa-Tunya'', "Thundering Smoke/Smoke that Rises"; Tonga language (Zambia and Zimbabwe), Tonga: ''Shungu Namutitima'', "Boiling Water") is a waterfall on the Zambezi River, located on the border betwe ...

, also attended by Griffiths and Patrick Gordon Walker

Patrick Chrestien Gordon Walker, Baron Gordon-Walker, (7 April 1907 – 2 December 1980) was a British Labour Party politician. He was a Member of Parliament for nearly 30 years and twice a cabinet minister. He lost his Smethwick parliamenta ...

. Another two conferences would be held in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

in 1952 and 1953 respectively, where the federal structure was prepared in detail.

While many points of contention were worked out in the conferences that followed, several proved to be acute, and some, seemingly insurmountable. The negotiations and conferences were arduous. Southern Rhodesia and the Northern Territories had very different traditions for the 'Native Question' (black Africans) and the roles they were designed to play in civil society. Sir Andrew Cohen, CO Assistant Undersecretary for African Affairs (and a later Governor of Uganda). He became one of the central architects and driving forces behind the creation of the Federation, often seemingly singlehandedly untangling deadlocks and outright walkouts on the part of the respective parties. Cohen, who was Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

ish and traumatised by The Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

, was an anti-racialist and an advocate of African rights. But he compromised his ideals to avoid what he saw as an even greater risk than the continuation of the paternalistic white ascendancy system of Southern Rhodesia – its becoming an even less flexible, radical white supremacy, like the National Party government in South Africa. Lord Blake, the Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

-based historian, wrote: "In that sense, Apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

can be regarded as the father of Federation". The Commons approved the conferences' proposals on 24 March 1953, and in April passed motions in favour of federating the territories of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. A referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

was held in Southern Rhodesia on 9 April. Following the insistence and reassurances of the Southern Rhodesian prime minister, Sir Godfrey Huggins, a little more than 25,000 white Southern Rhodesians voted in the referendum for a federal government, versus nearly 15,000 against. A majority of Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a Southern African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers who first arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting''. Encyclopæd ...

s and black Africans in all three territories were resolutely against it. The Federation came into being when the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace ...

enacted the Rhodesia and Nyasaland Federation Act, 1953. The Act authorised the Queen, by way of an Order in Council

An Order in Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom, this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' ...

, to provide for the federation of the three constituent territories. This order was made on 1 August 1953, bringing certain provisions of the Constitution into operation. The first Governor-General, Lord Llewellin, assumed office on 4 September. On 23 October 1953, Llewellin issued a proclamation bringing the remainder of the provisions of the Constitution into operation.

Constitution

The semi-independent federation was finally established, with five branches of government: one Federal, three Territorial, and one British. This often translated into confusion and jurisdictional rivalry among various levels of government. According to Lord Blake, it proved to be "one of the most elaborately governed countries in the world." The Constitution provided for a federal government with enumerated powers, consisting of an executive government, a unicameral Federal Assembly (which included a standing committee known as the African Affairs Board), and a Supreme Court, among other authorities. Provision was made for the division of powers and duties between the federal and territorial governments. Article 97 of the Constitution empowered the Federal Assembly to amend the Constitution, which included a power to establish a second legislative chamber. The Governor-General would be the representative of the Queen in the Federation. Federal authority extended only to those powers assigned to the federal government and to matters incidental to them. The enumerated federal powers were divided into a "Federal Legislative List" for which the federal legislature could make laws, and a "Concurrent Legislative List" for which both the federal and territorial legislatures could make law. Federal laws prevailed over territorial laws in all cases where the federal legislature was empowered to legislate, including the concurrent list. The executive government consisted of theGovernor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

, who would represent the Queen, an Executive Council consisting of the prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

and nine other ministers appointed by the Governor-General on recommendation from the Prime Minister, and a Cabinet of ministers appointed by the Prime Minister. The judiciary consisted of a Supreme Court, later regulated by the Federal Supreme Court Act, 1955, which consisted of the Chief Justice, two federal justices, and the chief justices of each of the three constituent territories of the Federation. The court was inaugurated on 1 July 1955, when the Governor-General swore in the Chief Justice and the other judges. The ceremony was also attended by the Lord High Chancellor and the Chief Justice of the Union of South Africa. The Chief Justices were Sir Robert Tredgold, previously Chief Justice of Southern Rhodesia, who was Chief Justice of the Federation from 1953 to 1961, and Sir John Clayden, from 1961 to 1963. The Supreme Court's jurisdiction was limited chiefly to hearing appeals from the high courts of the constituent territories. The court, however, had original jurisdiction over the following:

* Disputes between the federal government and territorial governments, or between territorial governments ''inter se'', if such disputes involved questions (of law or fact) on which the existence or extent of a legal right depended;

* Matters affecting vacancies in the Federal Assembly and election petitions; and

* Matters in which a writ or order of mandamus

A writ of (; ) is a judicial remedy in the English and American common law system consisting of a court order that commands a government official or entity to perform an act it is legally required to perform as part of its official duties, o ...

, or prohibition or an injunction

An injunction is an equitable remedy in the form of a special court order compelling a party to do or refrain from doing certain acts. It was developed by the English courts of equity but its origins go back to Roman law and the equitable rem ...

, is sought against an officer or authority of the federal government.

In 1958, the Prime Minister established an Office of Race Affairs which reviewed policies, practices and activities which may have hampered or adversely affected a climate favourable to the federal government's equal "partnership" policy. On 1 April 1959, the Prime Minister appointed the Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Home Affairs, who held the status of a full minister, to assume responsibility for racial affairs.

It was commonly understood that Southern Rhodesia would be the dominant territory in the federation economically, electorally, and militarily. How much so defined much of the lengthy constitutional negotiations and modifications that followed. African political opposition and

It was commonly understood that Southern Rhodesia would be the dominant territory in the federation economically, electorally, and militarily. How much so defined much of the lengthy constitutional negotiations and modifications that followed. African political opposition and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

aspirations, for the time, were moot.

Decisive factors in both the creation and dissolution of the Federation were the significant difference between the number of Africans and Europeans in the Federation, and the difference between the number of Europeans in Southern Rhodesia compared to the Northern Protectorates. Compounding this was the significant growth in Southern Rhodesia's European settler population (overwhelmingly British migrants), unlike in the Northern Protectorates. This was to greatly shape future developments in the Federation. In 1939, approximately 60,000 Europeans resided in Southern Rhodesia; shortly before the Federation was established there were 135,000; by the time the Federation was dissolved they had reached 223,000 (though newcomers could only vote after three years of residency). Nyasaland showed the least European and greatest African population growth. /sup> The dominant role played by the Southern Rhodesian European population within the CAF is reflected in that played by its first leader, Sir Godfrey Huggins (created Viscount Malvern in February 1955), Prime Minister of the Federation for its first three years and, before that, Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia for an uninterrupted 23 years. Huggins resigned the premiership of Southern Rhodesia to take office as the federal prime minister, and was joined by most United Rhodesia Party cabinet members. There was a marked exodus to the more prestigious realm of federal politics. The position of Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia was once again, as under Britain's Ministerial Titles Act of 1933, reduced to a Premier and taken by The Rev. Garfield Todd, the soon-to-be controversial centre-left

Centre-left politics is the range of left-wing political ideologies that lean closer to the political centre. Ideologies commonly associated with it include social democracy, social liberalism, progressivism, and green politics. Ideas commo ...

politician. It was considered that Todd's position and territorial politics in general had become relatively unimportant, a place for the less ambitious politician. In fact, it was to prove decisive both to the future demise of the CAF, and to the later rise of the Rhodesian Front.

Rather than a federation, Prime Minister Huggins favoured an amalgamation, creating a unitary state. However, after the Second World War, Britain opposed this because Southern Rhodesia would dominate the property and income franchise (which excluded the vast majority of Africans) owing to its much larger European population. A federation was intended to curtail this.[ Huggins was thus the first prime minister from 1953 to 1956, and was followed by Roy Welensky">Sir Roy Welensky, a prominent Northern Rhodesian politician, from 1956 to the Federation's dissolution in December 1963.

The fate of the Federation was contested within the British Government by two principal Ministry (government department), Ministries of British Crown, the Crown in deep ideological, personal and professional rivalry – the Colonial Office (CO) and the Commonwealth Relations Office (CRO) (and previously with it the Dominion Office

The position of secretary of state for dominion affairs was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for British relations with the Empire’s dominions – Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundl ...

, abolished in 1947). The CO ruled the northern territories of Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia, while the CRO was formally but indirectly in charge of Southern Rhodesia. The northern territories opposed a Southern Rhodesian hegemony, one that the CRO promoted. Significantly, the CO tended to be more sympathetic to African rights than the CRO, which tended to promote the interests of the Southern Rhodesian (and to a lesser extent, Northern Rhodesian) European settler populations.[ In 1957, this led to calls by Welensky for the creation of a single department with responsibility for all three territories, with Macmillan also favouring the CRO assuming sole responsibility for them, but was persuaded by the Cabinet Secretary that this would face opposition from both Africans and members of the colonial service in the northern territories. Consequently, in 1962, the Federation's affairs were transferred to a new department, known as the Central Africa Office, with Rab Butler the minister responsible. However, this was to be short lived, as following the succession of Macmillan as prime minister by Alec Douglas-Home, responsibility for the Federation was returned to the CRO and CO, with Duncan Sandys

Duncan Edwin Duncan-Sandys, Baron Duncan-Sandys (; 24 January 1908 – 26 November 1987), was a British politician and minister in successive Conservative governments in the 1950s and 1960s. He was a son-in-law of Winston Churchill and played a ...

responsible for both.

It was convenient to have all three territories colonised by Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

under one constitution. But, for Huggins and the Rhodesian establishment, the central economic motive behind the CAF (or amalgamation) was the abundant copper deposits of Northern Rhodesia. Unlike the Rhodesias, Nyasaland had no sizeable deposits of minerals and its tiny community of Europeans, largely Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

, was relatively sympathetic to African aspirations. Its inclusion in the Federation was more a symbolic gesture than a practical necessity. This inclusion would eventually work against the CAF: Nyasaland and its African population was where the impetus for destabilisation of the CAF arose, leading to its dissolution. Kariba hydroelectricity">hydro-electric power station was announced. It was a remarkable feat of engineering creating the largest man-made dam on the planet at the time and costing £78 million. Its location highlighted the rivalry among Southern and Northern Rhodesia, with the former attaining its favoured location for the dam.

The CAF brought a decade of liberalism with respect to African rights. There were African junior ministers in the Southern Rhodesia-dominated CAF, while a decade earlier only 70 Africans qualified to vote in the Southern Rhodesian elections.

The property and income-qualified franchise of the CAF was, therefore, now much looser. While this troubled many whites, they continued to follow Huggins with the CAF's current structure, largely owing to the economic growth. But to Africans, this increasingly proved unsatisfactory and their leaders began to voice demands for majority rule.

Rise of African nationalism

Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

and the CAF cabinet were never to recover. These events, for the first time, brought the attention of British Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

, to a crisis emerging in the CAF, but apparently he did not fully comprehend the gravity of the situation, attributing the row to the old CO-CRO rivalry and to Welensky taking personal offence to the letter's contents.

The issues of this specific row were in the immediate sense resolved quietly with some constitutional amendments, but it is now known that Welensky was seriously considering contingencies for a Unilateral Declaration of Independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) or "unilateral secession" is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the ...

(UDI) for the federation, though he ended up opting against it.

Meanwhile, towards the end of the decade, in the Northern Territories, Africans protested against the white minority rule of the CAF. In July 1958, Hastings Banda

Hastings Kamuzu Banda ( – 25 November 1997) was a Malawian politician and statesman who served as the leader of Malawi from 1964 to 1994. He served as Prime Minister of Malawi, Prime Minister from independence in 1964 to 1966, when Malawi was ...

, the leader of the Nyasaland African Congress

The Nyasaland African Congress (NAC) was an organisation that evolved into a political party in Nyasaland during the colonial period. The NAC was suppressed in 1959, but was succeeded in 1960 by the Malawi Congress Party, which went to on decisiv ...

(NAC) (later Malawi Congress Party

The Malawi Congress Party (MCP) is a political party in Malawi. It was formed as a successor party to the banned Nyasaland African Congress when the country, then known as Nyasaland, was under British rule. The MCP, under Hastings Banda, pre ...

), returned from Great Britain to Nyasaland, and in October Kenneth Kaunda

Kenneth Kaunda (28 April 1924 – 17 June 2021), also known as KK, was a Zambian politician who served as the first president of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He was at the forefront of the struggle for independence from Northern Rhodesia, British ...

became the leader of the Zambian African National Congress (ZANC), a split from the Northern Rhodesian ANC. The increasingly rattled CAF authorities banned ZANC in March 1959, and in June imprisoned Kaunda for nine months. While Kaunda was in jail, his loyal lieutenant Mainza Chona

Mainza Mathias Chona (21 January 1930 – 11 December 2001) was a Zambian politician and founder of UNIP who served as the third vice-president of Zambia from 1970 to 1973 and Prime Minister on two occasions: from 25 August 1973 to 27 May 1 ...

worked with other African nationalists to create the United National Independence Party

The United National Independence Party (UNIP) is a political party in Zambia. It governed the country from 1964 to 1991 under the socialist President (government title), presidency of Kenneth Kaunda, and was the sole legal party in the country ...

(UNIP), a successor to ZANC. In early 1959, unrest broke out in Nyasaland, which, according to historian Lord Blake, was "economically the poorest, politically the most advanced and numerically the least Europeanized of the three Territories."

The CAF government declared a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state before, during, o ...

. Banda and the rest of Nyasaland's NAC leadership were arrested and their party outlawed. Southern Rhodesian troops were deployed to bring order. The controversial British Labour MP John Stonehouse

John Thomson Stonehouse (28 July 192514 April 1988) was a British Labour and Co-operative Party politician, businessman and minister who was a member of the Cabinet under Prime Minister Harold Wilson. He is remembered for his unsuccessful atte ...

was expelled from Southern Rhodesia shortly before the state of emergency was proclaimed in Nyasaland, which outraged the British Labour Party

The Labour Party, often referred to as Labour, is a List of political parties in the United Kingdom, political party in the United Kingdom that sits on the Centre-left politics, centre-left of the political spectrum. The party has been describe ...

.

The affair drew the whole concept of the federation into question and even Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Macmillan began to express misgivings about its political viability, although economically he felt it was sound. A Royal Commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

to advise Macmillan on the future of the CAF, to be led by The 1st Viscount Monckton of Brenchley, QC, the former Paymaster General

His Majesty's Paymaster General or HM Paymaster General is a ministerial position in the Cabinet Office of the United Kingdom. The position is currently held by Nick Thomas-Symonds of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party.

History

The post was ...

, was in the works. The Commonwealth Secretary, The 14th Earl of Home, was sent to prepare Prime Minister Welensky, who was distinctly displeased about the arrival of the commission.

Welensky at least found Lord Home in support of the existence of the CAF. By contrast, Lord Home's rival, and fellow Scot

Scottish people or Scots (; ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Scotland. Historically, they emerged in the early Middle Ages from an amalgamation of two Celtic peoples, the Picts and Gaels, who founded the Kingdom of Scotland (or ...

, the Colonial Secretary, Iain Macleod

Iain Norman Macleod (11 November 1913 – 20 July 1970) was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politician.

A playboy and professional Contract bridge, bridge player in his twenties, after war service Macleod worked for the ...

, favoured African rights and dissolving the federation. Although Macmillan at the time supported Lord Home, the changes were already on the horizon. In Britain, Macmillan said that it was essential "to keep the Tory party on modern and progressive lines", noting electoral developments and especially the rise of the Labour Party.

Dissolution

By the time Macmillan went on his famous 1960 African tour leading to his ''Wind of Change'' speech to

By the time Macmillan went on his famous 1960 African tour leading to his ''Wind of Change'' speech to Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

in Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, change was well underway. By 1960, French African colonies had already become independent. Belgium more hastily vacated its colony and thousands of European refugees fled the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

from the brutalities of the civil war and into Southern Rhodesia.

During the Congolese crisis, Africans increasingly viewed Welensky as an arch-reactionary and his support for Katanga separatism added to this. Welensky was disliked by the right and the left, though: a few years later, in his by-election campaign against Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 191920 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1979. He w ...

's Rhodesian Front, RF supporters heckled the comparatively moderate Welensky as a 'bloody Jew', 'Communist', 'traitor' and 'coward'.

The new Commonwealth Secretary, Duncan Sandys

Duncan Edwin Duncan-Sandys, Baron Duncan-Sandys (; 24 January 1908 – 26 November 1987), was a British politician and minister in successive Conservative governments in the 1950s and 1960s. He was a son-in-law of Winston Churchill and played a ...

, negotiated the '1961 Constitution', a new constitution for the CAF which greatly reduced Britain's powers over it: however, by 1962, the British and the CAF cabinet had agreed that Nyasaland should be allowed to secede, though Southern Rhodesian Premier Sir Edgar Whitehead committed the British to keep this secret until after the 1962 elections in the territory. A year later, the same status was given to Northern Rhodesia, decisively ending the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in the immediate future.

In 1963, the Victoria Falls

Victoria Falls (Lozi language, Lozi: ''Mosi-oa-Tunya'', "Thundering Smoke/Smoke that Rises"; Tonga language (Zambia and Zimbabwe), Tonga: ''Shungu Namutitima'', "Boiling Water") is a waterfall on the Zambezi River, located on the border betwe ...

Conference was held, partly as a last effort to save the CAF, and partly as a forum to dissolve it. On 5 June 1963, the leaders of Kenya, Tanganyika, and Uganda expressed their intention to unite as the federation of East Africa. By late June 1963, a federation was nearly seen as inevitable, but within months the prospect of creating a federation dissipated.

Various explanations have been offered for the failure to establish a federation, including Ugandan concerns about its own weakness within such a federation, ideological objections to plans by Kwame Nkrumah's push for a larger East African federation, the hostility of the Buganda kingdom (within Uganda) to union, tensions over the uneven distribution of benefits from economic integration, lack of clarity on the function or form of federation, a lack of popular engagement with the process, and bad timing." Scholars such as Joseph Nye and Thomas Franck wrote about the failure of the federation, with Franck characterizing it as a tragedy. All three territories had slipped into recession with the end of the federation.

On 31 December 1963, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was formally dissolved, and its assets distributed among the territorial governments. Southern Rhodesia obtained the vast majority of these including the assets of the Federal army, to which it had overwhelmingly contributed. In July 1964, the Nyasaland Protectorate became independent as Malawi

Malawi, officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over and ...

, led by Banda, and that October, Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in Southern Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by Amalgamation (politics), amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North ...

gained independence as the Republic of Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

- being led by Kaunda.

On 11 November 1965, Southern Rhodesia's government, led by Prime Minister Ian Smith, proclaimed a Unilateral Declaration of Independence from the United Kingdom. This attracted the world's attention and created outrage in Britain.

Military

The Minister of Defence was the President of the Defence Council, which consisted of military and civilian members, and considered all matters related to defense policy. The Army, in 1960, consisted of three training formations: * The School of Infantry, based in Gwelo, was responsible for extra-regimental training. It was organized into tactical and regimental wings, with courses ranging from command and weapons training. * The Regular Army Depot, based in Salisbury, handled all basic training for black recruits. * The Depot, The Royal Rhodesia Regiment, trained recruits for the Territorial Force battalions. Corps training was handled by the Rhodesia and Nyasaland Corps of Engineers, Corps of Signals, and the Army Service Corps. In May 1958, three installations were named after "three of the most famous soldiers in the military history of Central Africa". The RAR camp in Llewellin was named Methuen Camp afterColonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

J.A. Methuen. The Zomba Cantonment was named Cobbe Barracks after Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Cobbe

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Alexander Stanhope Cobbe (6 June 1870 – 29 June 1931) was a senior British Indian Army officer and a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be a ...

. The Lusaka

Lusaka ( ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Zambia. It is one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa. Lusaka is in the southern part of the central plateau at an elevation of about . , the city's population was abo ...

military area was named Stephenson Barracks after Lieutenant-Colonel A. Stephenson.

Llewellin Barracks in Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; ) is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council claimed it to be about ...

commemorated the first Governor-General of the Federation. The Battle of Tug Argan was commemorated in the name of Tug Argan Barracks in Ndola

Ndola is the third largest city in Zambia in terms of size and population, with a population of 627,503 (''2022 census''), after the capital, Lusaka, and Kitwe, and the second largest in terms of infrastructure development after Lusaka. It is the I ...

.

The Army consisted of four African battalions: the 1st and 2nd Battalion, King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles (KAR) was a British Colonial Auxiliary Forces regiment raised from Britain's East African colonies in 1902. It primarily carried out internal security duties within these colonies along with military service elsewher ...

; the Northern Rhodesia Regiment

The Northern Rhodesia Regiment (NRR) was a British Colonial Auxiliary Forces regiment raised from the protectorate of Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in Southern Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. ...

; and the Rhodesian African Rifles.1961, the all-White 1st Battalion of the Rhodesian Light Infantry regiment was added.

The Rhodesia and Nyasaland Women's Military Air Service (known popularly as the "WAMS") was the Federation's women's auxiliary unit. In 1957 a policy change led to the unit being gradually scaled down until its work was taken over by civilian staff.

Legacy

Although the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland only lasted for ten years, it had an important effect on Central Africa. Its White minority rule, where a couple of hundred thousand Europeans primarily in Southern Rhodesia ruled over millions of Black Africans, was largely driven by paternalistic reformism, that collided with rising African self-confidence andnationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

.

The British influenced and affiliated federation and its institutions and racial relations differed from the only other regional power, the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

. The dissolution of the CAF highlighted the discrepancy between the independent African-led nations of Zambia and Malawi, and Southern Rhodesia (which remained ruled by a White minority government until the Internal Settlement

The Internal Settlement (also called the Salisbury Agreement HC Deb 04 May 1978 vol 949 cc 455–592) was an agreement which was signed on 3 March 1978 between Prime Minister of Rhodesia Ian Smith and the moderate African nationalist leaders comp ...

in 1978). Southern Rhodesia soon found itself embroiled in a civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

between the Government and African nationalist and Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

guerrillas, where as both Malawi and Zambia developed into authoritarian one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

s dictatorship

A dictatorship is an autocratic form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, who hold governmental powers with few to no Limited government, limitations. Politics in a dictatorship are controlled by a dictator, ...

s and remained so up until the post-Cold War era in the mid 1990's.

Following Southern Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) or "unilateral secession" is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the ...

(UDI), a growing conflict emerged between two of the former CAF territories Zambia (supporting African nationalist and Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

guerrillas) and Southern Rhodesia (supported by South Africa and Portugal until 1974) with much heated diplomatic rhetoric, and, at times, outright military hostility.

Postage and revenue stamps

The Federation issued its first postage stamps in 1954, all with a portrait of

The Federation issued its first postage stamps in 1954, all with a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

. See main article at Postage stamps of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Revenue stamps were also issued, see Revenue stamps of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

Coins and banknotes

The Federation also issued its own bank notes and coinage to replace theSouthern Rhodesian pound

The pound was the currency of Southern Rhodesia. It also circulated in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. The pound was subdivided into 20 ''shillings'', each of 12 ''penny, pence''.

History

From 1896, private banks issued notes denominated in £ ...

which had been circulating in all three parts of the federation. In 1955 a full new set of coins were issued with the Mary Gillick obverse of the Queen and various African animals on the reverse. The denominations followed those of sterling, namely halfpennies and pennies, which had a hole in them, threepences (known as tickeys), sixpences, shillings, a two shilling piece and a half crown. There were further full issues of all these coins in 1956 and 1957, but thereafter only pennies and half pennies were produced until some further issues of sixpences in 1962 and 1963, and threepences in 1963 and 1964. The higher denomination coins, though not particularly rare, are very popular with collectors because of their attractive reverse designs. Threepences and halfpennies were struck in 1964 despite the fact the Federation ended on 31 December 1963.

See also

*1953 Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland election

Federal elections were held in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland on 15 December 1953. They were the first elections to the Legislative Assembly of the federation, which had been formed a few months before. The elections saw a landslide vi ...

* 1958 Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland election

Federal elections were held in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland on 12 November 1958. The result was a victory for the ruling United Federal Party, with Roy Welensky remaining Prime Minister.Kenneth Janda (1980) Political Parties: A Cross ...

* 1962 Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland election

Federal elections were held in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland on 27 April 1962. Due to a boycott by all opposition parties,Kenneth Janda (1980) Political Parties: A Cross-National Survey' New York: The Free Press, pp281–282 the ruling ...

* Government of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

The Government of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was established in 1953 and ran the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Federation until its dissolution at the end of 1963. The members of the government were accountable to, and drawn ...

*

Notes

References

* Cohen, Andrew. ''The Politics and Economics of Decolonization in Africa: The Failed Experiment of the Central African Federation'' (I. B. Tauris, London, 2017). * Franklin, Henry. ''Unholy wedlock: the failure of the Central African Federation'' (G. Allen & Unwin, London, 1963). * Blake, Robert. ''A History of Rhodesia'' (Eyre Methuen, London 1977). * Hancock, Ian. ''White Liberals, Moderates, and Radicals in Rhodesia, 1953–1980'' (Croom Helm, Sydney, Australia, 1984). * Mason, Phillip. ''Year of Decision: Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1960'' (Oxford University Press, 1961). * Phillips, C. E. Lucas. ''The vision splendid: the future of the Central African Federation'' (Heinemann, London, 1960). * Leys, Colin and Pratt Cranford (eds.). ''A new deal in Central Africa'' (Heinemann, London, 1960). * Clegg, Edward Marshall. ''Race and politics: partnership in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland''. (Oxford University Press, 1960). * Gray, Richard. ''The two nations: aspects of the development of race relations in the Rhodesias and Nyasaland'' (Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn., 1960). * Rogaly, Joe. ''Rhodesia: Britain's deep south''. (The Economist, London, 1962). * Hall, Richard. ''The High Price of Principles: Kaunda and the White South'' (Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1969). * Guy Clutton-Brock. ''Dawn in Nyasaland'' (Hodder and Stoughton, London 1959). * Dorien, Ray. ''Venturing to the Rhodesias and Nyasaland'' (Johnson, London, 1962) * Hanna, Alexander John. ''The story of the Rhodesias and Nyasaland.'' (Faber and Faber, 1965). * Black, Colin. ''The lands and peoples of Rhodesia and Nyasaland'' (Macmillan, NY, 1961). * Sanger, Clyde. ''Central African emergency'' (Heinemann, London 1960). * Gann, Lewis H. ''Huggins of Rhodesia: the man and his country'' (Allen & Unwin, London, 1964). * Gann, Lewis H. ''Central Africa: the former British states'' (Englewood Cliffs, N. J., Prentice-Hall, 1971). * Haw, Richard C. (fwd. by Sir Godfrey Huggins) ''No other home: Co-existence in Africa'' (S. Manning, Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia, 1960?). * Taylor, Don. ''The Rhodesian: the life of Sir Roy Welensky.'' (Museum Press, London 1965). * Wood, J.R.T. ''The Welensky papers: a history of the federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland'' (Graham Pub., Durban, 1983). * Welensky, Roy, Sir. ''Welensky's 4000 days: the life and death of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland'' (Collins, London, 1964). * Allighan, Garry. ''The Welensky story'' (Macdonald, London, 1962). * Alport, Cuthbert James McCall, Lord. ''The sudden assignment: being a record of service in central Africa during the last controversial years of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, 1961–1963.'' (Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1965). * Thompson, Cecil Harry. ''Economic development in Rhodesia and Nyasaland'' (D. Dobson, Publisher London, 1954) * Walker, Audrey A. ''The Rhodesias and Nyasaland: a guide to official publications'' (General Reference and Bibliography Division, Reference Dept., Library of Congress: for sale by the Superintendent of Documents, US Govt. Print. Off., 1965). * Irvine, Alexander George. ''The balance of payments of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, 1945–1954.'' (Oxford University Press, 1959.) * United States Bureau of Foreign Commerce, Near Eastern and African Division. ''Investment in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland: basic information for United States businessmen.'' (U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign Commerce, 1956) * Standard Bank of South Africa, Ltd. ''The federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland: general information for business organisations.'' (London, 1958). * Sowelem, R. A. ''Toward financial independence in a developing economy: an analysis of the monetary experience of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, 1952–63.'' (Allen & Unwin, London, 1967). * Shutt, Allison K. ''Manners Make A Nation: Racial Etiquette in Southern Rhodesia, 1910–1963''. (University of Rochester Press, 2015). * Wood, J. R. T. ''So far and no further!: Rhodesia's bid for independence during the retreat from empire, 1959–1965''. (Trafford, 2004).External links

* Rhodesia and Nyasaland Army http://www.rhodesia.nl/ceremonialparade.pdfWindow on Rhodesia

an archive of the history and life of Rhodesia * {{DEFAULTSORT:Federation of Rhodesia And Nyasaland 1950s in Northern Rhodesia 1950s in Nyasaland 1950s in Southern Rhodesia 1953 establishments in Africa 1953 establishments in Nyasaland 1953 establishments in Southern Rhodesia 1953 establishments in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland 1960s in Northern Rhodesia 1960s in Nyasaland 1960s in Rhodesia 1960s in Southern Rhodesia 1963 disestablishments in Africa 1963 disestablishments in Nyasaland 1963 disestablishments in Southern Rhodesia 1963 disestablishments in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland 20th century in Malawi 20th century in Rhodesia 20th century in Zambia 20th century in Zimbabwe English-speaking countries and territories Former British colonies and protectorates in Africa Former confederations Malawi–United Kingdom relations Northern Rhodesia Nyasaland Rhodesia–United Kingdom relations Southern Rhodesia States and territories disestablished in 1963 States and territories established in 1953 United Kingdom–Zambia relations United Kingdom–Zimbabwe relations