Religious tolerance or religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". Historically, most incidents and writings pertaining to toleration involve the status of

minority and dissenting viewpoints in relation to a dominant

state religion. However, religion is also sociological, and the practice of toleration has always had a political aspect as well.

An overview of the history of toleration and different cultures in which toleration has been practiced, and the ways in which such a paradoxical concept has developed into a guiding one, illuminates its contemporary use as political, social, religious, and ethnic, applying to

LGBT

LGBTQ people are individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning. Many variants of the initialism are used; LGBTQIA+ people incorporates intersex, asexual, aromantic, agender, and other individuals. The gro ...

individuals and other minorities, and other connected concepts such as

human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

.

Definition

The term "tolerance" derives from the Latin ''tolerantia'', meaning "endurance" or "the ability to bear." For Cicero, ''tolerantia'' was a personal virtue—the capacity to endure hardship, injustice, or misfortune with composure. By the sixteenth century the notion of tolerance began to take on a more political dimension, associated with maintaining peace and social concord amid religious conflict. This is seen in developments like the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, even though the term itself was not explicitly invoked. Over time, the concept evolved from mere forbearance—what John Horton describes as "putting up with" disapproved beliefs—toward a broader commitment to recognizing and respecting diversity.

The concept of tolerance is multifaceted, shaped by various academic disciplines including philosophy, sociology, political science, religious studies, and law. Tolerance research reveals a plurality of interpretations, each contingent upon specific social, political, and cultural contexts. In antiquity, Cicero’s notion of ''tolerantia'' emphasized endurance in the face of adversity. Early modern thinkers such as Baruch Spinoza, Pierre Bayle, and John Locke explored tolerance primarily in political terms.

By the 18th century, Moses Mendelssohn advocated for religious tolerance as a fundamental human right, a position later expanded by figures such as John Rawls, who framed tolerance as a virtue of justice, and Michael Walzer, who linked it to the necessity of pluralism.

Scholars such as John Horton, David Heyd, and Anna Galeotti have further debated whether tolerance inherently involves disapproval or can be redefined as recognition. Key conditions for the emergence of tolerance include power dynamics, social conflict, and normative disagreement. As Karl Popper famously asserted, tolerance must have limits to prevent its self-destruction, particularly in the face of intolerance. Contemporary research emphasizes that tolerance involves both rejection and acceptance, underscoring its normative and complex nature. Thus, the ambiguity and contextuality of tolerance present significant challenges in arriving at a unified definition.

Renaissance humanism emphasized individual dignity, critical thinking, and ethical living over religious dogma. Thinkers such as Erasmus and Jean Bodin promoted tolerance by valuing personal conscience and diversity of belief. Their approach resisted both Catholic and Protestant intolerance, favoring persuasion over coercion and rejecting harsh condemnations of heresy. Humanist ideals later influenced Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who argued that a humane society must support “the positive welcoming and prizing of human individuality”.

Liberalism, particularly through John Stuart Mill, expanded the idea of tolerance beyond religion to include political and cultural pluralism. Mill defended the necessity of free expression, even of offensive ideas, as a path to truth and societal benefit. John Rawls later developed the theory of political liberalism, grounding it in equality, fairness, and a shared public reason that all citizens could endorse regardless of personal beliefs. However, critics like Adam Seligman caution that liberal tolerance sometimes becomes “principled indifference,” privatizing difference rather than engaging with it. Together, humanism and liberalism created philosophical foundations for modern notions of tolerance by emphasizing respect, equality, and freedom of conscience.

Religious tolerance has deep historical roots within religious and metaphysical traditions predating Enlightenment liberalism. In Jewish thought, Moses is depicted as an exemplar of tolerance (Numbers 12:3), a virtue further emphasized by Maimonides as essential for wise and just political leadership. Moses Mendelssohn articulated a metaphysical defense of religious diversity, viewing it as part of divine providence and necessary for spiritual and social perfection. Christian mysticism also contributed to early notions of tolerance by recognizing multiple paths to the divine, minimizing dogmatic authority. Figures such as Dionysios the Areopagite and Meister Eckhart highlighted individual spiritual experience and unity with the divine, allowing for varied approaches to ultimate reality. These traditions laid the groundwork for later concepts of tolerance by emphasizing respect for difference and the legitimacy of diverse religious expressions within a shared spiritual framework.

Contemporary scholarship has adopted an inclusive and active approach to defining religious tolerance. Twenty-first century definitions of religious tolerance have drawn upon sociological, anthropological, and psychological perspectives. Religious tolerance is now commonly understood as:

“people’s capacity or willingness to accept, respect, and coexist with differing viewpoints, beliefs, practices, or behaviours without resorting to aggression, discrimination, or conflict.”

Sociologist Charles Taylor emphasizes the importance of balancing “the autonomy of religious groups and the overarching principles of civic life” for a tolerant society. In a keynote speech, Ambassador Maurizio Massari stated that “tolerance is a key ingredient of democracy.” Recent studies indicate that individuals who feel accepted in inclusive societies are more likely to engage in civic and political life.Education and media literacy programs are seen as vital for cultivating tolerance. Psychological research by Hook and colleagues finds that intellectual humility in relation to religious beliefs encourages greater religious tolerance. This humility fosters openness to other perspectives, strengthens mutual understanding, and reduces defensiveness. Suryani and Muslim advocate incorporating religious tolerance into religious education curricula to address pluralism, social cohesion, interfaith respect, and open-mindedness. Research from Indonesia suggests that religious education in schools can promote interfaith understanding and tolerance.

The expanded concept of religious tolerance is increasingly linked to human rights, education, and LGBTQ+ rights. It is now seen as an evolving process of dialogue and active engagement, valuing all religious traditions within a pluralistic society. Modern conceptions of tolerance advocate not just coexistence, but the broader framework of religious freedom. Some scholars argue that "religious freedom" better expresses the commitment to equal dignity and personal growth, integrating with human rights and encouraging active respect over passive acceptance.

In Antiquity

Religious toleration has been described as a "remarkable feature" of the

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

of Persia.

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

assisted in the restoration of the sacred places of various cities.

In the

Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

, Cyrus was said to have released the Jews from the

Babylonian captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile was the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were forcibly relocated to Babylonia by the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The deportations occurred ...

in 539–530 BCE, and permitted their return to their homeland.

The

Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

city of

Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, founded 331 BCE, contained a large Jewish community which lived in peace with equivalently sized Greek and Egyptian populations. According to

Michael Walzer

Michael Laban Walzer (born March 3, 1935) is an American Political theory, political theorist and public intellectual. A professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey, he is editor emeritus of the left-win ...

, the city provided "a useful example of what we might think of as the imperial version of multiculturalism."

Before

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

became the

state church of the Roman Empire

In the year before the First Council of Constantinople in 381, Nicene Christianity, Nicean Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Theodosius I, emperor of the East, Gratian, emperor of the West, and Gratian's junior co-r ...

, it encouraged conquered peoples to continue worshipping their own gods. "An important part of Roman propaganda was its invitation to the gods of conquered territories to enjoy the benefits of worship within the ''imperium''."

Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

were singled out for persecution because of their own rejection of Roman pantheism and refusal to honor the emperor as a god. There were some other groups that found themselves to be exceptions to Roman tolerance, such as the

Druids

A druid was a member of the high-ranking priestly class in ancient Celtic cultures. The druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no wr ...

, the early followers of the cult of

Isis

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom () as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her sla ...

, the

Bacchanals, the

Manichaens and the

priests of Cybele, and

Temple Judaism was also suppressed.

In the early 3rd century,

Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history of ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

outlined the Roman imperial policy towards religious tolerance:

In 311 CE, Roman Emperor

Galerius

Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; Greek: Γαλέριος; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. He participated in the system of government later known as the Tetrarchy, first acting as '' caesar'' under Emperor Diocletian. In th ...

issued a general

edict of toleration of Christianity, in his own name and in those of

Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (; Ancient Greek, Greek: Λικίνιος; c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign, he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan that ...

and

Constantine I

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

(who converted to Christianity the following year).

Saint Catherine's Monastery

Saint Catherine's Monastery ( , ), officially the Sacred Autonomous Royal Monastery of Saint Catherine of the Holy and God-Trodden Mount Sinai, is a Christian monastery located in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. Located at the foot of Mount Sinai ...

of the

Sinai region of Egypt claims to have once had possession of an original letter of protection from

Mohammed, known as the

Ashtiname of Muhammad and traditionally dated to 623 CE. The monastery's tradition holds that a Christian delegation from the Sinai requested for the continued activity of the monastery, and regional Christianity ''per se''. The original no longer exists, but a claimed 16th century copy of it remains on display in the monastery. While several twentieth century scholars accepted the document as a legitimate original, some modern scholars now question the documentary's authenticity.

Buddhism

Since the 19th century, Western intellectuals and spiritualists have viewed Buddhism as an unusually tolerant faith.

James Freeman Clarke

James Freeman Clarke (April 4, 1810 – June 8, 1888) was an American minister, theologian and author.

Biography

Born in Hanover, New Hampshire, on April 4, 1810, James Freeman Clarke was the son of Samuel Clarke and Rebecca Parker Hull, though ...

said in ''Ten Great Religions'' (1871) that "Buddhists have founded no Inquisition; they have combined the zeal which converted kingdoms with a toleration almost inexplicable to our Western experience."

Bhikkhu Bodhi

Bhikkhu Bodhi (born December 10, 1944) () born Jeffrey Block, is an American Theravada Buddhist monk ordained in Sri Lanka. He teaches in the New York and New Jersey area. He was appointed the second president of the Buddhist Publication Soci ...

, an American-born Buddhist convert, stated:

The

Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire who ruled most of the Indian subcontinent from 268 BCE to 2 ...

issued by King

Ashoka the Great

Ashoka, also known as Asoka or Aśoka ( ; , ; – 232 BCE), and popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was List of Mauryan emperors, Emperor of Magadha from until #Death, his death in 232 BCE, and the third ruler from the Mauryan dynast ...

(269–231 BCE), a Buddhist, declared ethnic and religious tolerance. His Edict in the 12th main stone writing of Girnar on the third century BCE which state that "Kings accepted religious tolerance and that Emperor Ashoka maintained that no one would consider his / her is to be superior to other and rather would follow a path of unity by accuring the essence of other religions".

However, Buddhism has also had controversies regarding toleration. In addition, the question of possible intolerance among Buddhists in Sri Lanka and Myanmar has been raised by Paul Fuller.

Christianity

The books of

Exodus,

Leviticus and

Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy (; ) is the fifth book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called () which makes it the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament.

Chapters 1–30 of the book consist of three sermons or speeches delivered to ...

make similar statements about the treatment of strangers. For example, Exodus 22:21 says: "Thou shalt neither vex a stranger, nor oppress him: for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt". These texts are frequently used in sermons to plead for compassion and tolerance of those who are different from us and less powerful.

Julia Kristeva elucidated a philosophy of political and religious toleration based on all of our mutual identities as strangers.

The New Testament

Parable of the Tares, which speaks of the difficulty of distinguishing wheat from weeds before harvest time, has also been invoked in support of religious toleration. In his "Letter to Bishop Roger of Chalons", Bishop

Wazo of Liege (c. 985–1048) relied on the parable to argue that "the church should let dissent grow with orthodoxy until the Lord comes to separate and judge them".

Roger Williams

Roger Williams (March 1683) was an English-born New England minister, theologian, author, and founder of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Pl ...

used this parable to support government toleration of all of the "weeds" (heretics) in the world, because civil persecution often inadvertently hurts the "wheat" (believers) too. Instead, Williams believed it was God's duty to judge in the end, not man's. This parable lent further support to Williams' belief in a

wall of separation between church and state as described in his 1644 book, ''

The Bloody Tenent of Persecution''.

Middle Ages

In the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, there were instances of toleration of particular groups. The Latin concept ''tolerantia'' was a "highly-developed political and judicial concept in medieval scholastic theology and canon law."

[Walsham 2006: 234.] ''Tolerantia'' was used to "denote the self-restraint of a civil power in the face of" outsiders, like infidels, Muslims or Jews, but also in the face of social groups like prostitutes and lepers.

Heretics such as the

Cathari,

Waldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

,

Jan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1369 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czechs, Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and t ...

, and his followers, the

Hussites, were persecuted. Later theologians belonging or reacting to the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

began discussion of the circumstances under which dissenting religious thought should be permitted. Toleration "as a government-sanctioned practice" in Christian countries, "the sense on which most discussion of the phenomenon relies—is not attested before the sixteenth century".

Unam sanctam and Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus

Centuries of Roman Catholic intoleration of other faiths was exemplified by ''

Unam sanctam'', a

papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

issued by

Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII (; born Benedetto Caetani; – 11 October 1303) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 until his death in 1303. The Caetani, Caetani family was of baronial origin with connections t ...

on 18 November 1302. The bull laid down dogmatic propositions on the unity of the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, the necessity of belonging to it for eternal salvation (''

Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus''), the position of the Pope as supreme head of the Church, and the duty thence arising of submission to the Pope in order to belong to the Church and thus to attain salvation. The bull ends, "Furthermore, we declare, we proclaim, we define that it is absolutely necessary for salvation that every human creature be subject to the Roman Pontiff."

Tolerance of the Jews

In Poland in 1264, the

Statute of Kalisz

The General Charter of Jewish rights known as the Statute of Kalisz, and the Kalisz Privilege, granted Jews in the Middle Ages some protection against discrimination in Poland compared to other places in Europe. These rights included exclusive ...

was issued, guaranteeing freedom of religion for the Jews in the country.

In 1348,

Pope Clement VI (1291–1352) issued a

bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not Castration, castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e. cows proper), bulls have long been an important symbol cattle in r ...

pleading with Catholics not to murder Jews, whom they blamed for the

Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

. He noted that Jews died of the plague like anyone else, and that the disease also flourished in areas where there were no Jews. Christians who blamed and killed Jews had been "seduced by that liar, the Devil". He took Jews under his personal protection at

Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

, but his calls for other clergy to do so failed to be heeded.

Johann Reuchlin (1455–1522) was a German humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew who opposed efforts by

Johannes Pfefferkorn, backed by the Dominicans of Cologne, to confiscate all religious texts from the Jews as a first step towards their forcible conversion to the Catholic religion.

Despite occasional spontaneous episodes of

pogroms and killings, as during the Black Death,

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

was a relatively tolerant

home for the Jews in the medieval period. In 1264, the

Statute of Kalisz

The General Charter of Jewish rights known as the Statute of Kalisz, and the Kalisz Privilege, granted Jews in the Middle Ages some protection against discrimination in Poland compared to other places in Europe. These rights included exclusive ...

guaranteed safety, personal liberties,

freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

, trade, and travel to Jews. By the mid-16th century, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was home to 80% of the world's Jewish population. Jewish worship was officially recognized, with a Chief Rabbi originally appointed by the monarch. Jewish property ownership was also protected for much of the period, and Jews entered into business partnerships with members of the nobility.

Vladimiri

Paulus Vladimiri (c. 1370–1435) was a Polish scholar and rector who at the

Council of Constance

The Council of Constance (; ) was an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church that was held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance (Konstanz) in present-day Germany. This was the first time that an ecumenical council was convened in ...

in 1414, presented a thesis, ''Tractatus de potestate papae et respectu infidelium'' (Treatise on the Power of the Pope and the Emperor Respecting Infidels). In it he argued that

pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

and Christian nations could coexist in peace and criticized the

Teutonic Order

The Teutonic Order is a religious order (Catholic), Catholic religious institution founded as a military order (religious society), military society in Acre, Israel, Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Sa ...

for its wars of conquest of native non-Christian peoples in Prussia and Lithuania. Vladimiri strongly supported the idea of conciliarism and pioneered the notion of peaceful coexistence among nations—a forerunner of modern theories of

human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

. Throughout his political, diplomatic and university career, he expressed the view that a world guided by the principles of peace and mutual respect among nations was possible and that pagan nations had a right to peace and to possession of their own lands.

Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

Roterodamus (1466–1536), was a Dutch Renaissance humanist and Catholic whose works laid a foundation for religious toleration. For example, in ''De libero arbitrio'', opposing certain views of

Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

, Erasmus noted that religious disputants should be temperate in their language, "because in this way the truth, which is often lost amidst too much wrangling may be more surely perceived." Gary Remer writes, "Like

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

, Erasmus concludes that truth is furthered by a more harmonious relationship between interlocutors." Although Erasmus did not oppose the punishment of heretics, in individual cases he generally argued for moderation and against the death penalty. He wrote, "It is better to cure a sick man than to kill him."

More

Saint Thomas More (1478–1535), Catholic Lord Chancellor of

King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

and author, described a world of almost complete religious toleration in

Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

(1516), in which the Utopians "can hold various religious beliefs without persecution from the authorities." However, More's work is subject to various interpretations, and it is not clear that he felt that earthly society should be conducted the same way as in Utopia. Thus, in his three years as Lord Chancellor, More actively approved of the persecution of those who sought to undermine the Catholic faith in England.

Reformation

At the

Diet of Worms (1521),

Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

refused to recant his beliefs citing

freedom of conscience as his justification. According to Historian Hermann August Winkler, the individual's freedom of conscience became the hallmark of

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

. Luther was convinced that faith in

Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

was the free gift of the

Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit, otherwise known as the Holy Ghost, is a concept within the Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is understood as the divine quality or force of God manifesting in the world, particularly in acts of prophecy, creati ...

and could therefore not be forced on a person. Heresies could not be met with force, but with preaching the

gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

revealed in the Bible. Luther: "Heretics should not be overcome with fire, but with written sermons." In Luther's view, the worldly authorities were entitled to expel heretics. Only if they undermine the public order, should they be executed. Later proponents of tolerance such as

Sebastian Franck and Sebastian Castellio cited Luther's position. He had overcome, at least for the Protestant territories and countries, the violent medieval criminal procedures of dealing with heretics. But Luther remained rooted in the Middle Ages insofar as he considered the

Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. The term (tra ...

' refusal to take oaths, do military service, and the rejection of private property by some Anabaptist groups to be a ''political'' threat to the public order which would inevitably lead to anarchy and chaos. So Anabaptists were persecuted not only in Catholic but also in Lutheran and Reformed territories. However, a number of Protestant theologians such as

John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

,

Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer (; Early German: ; 11 November 1491– 28 February 1551) was a German Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Anglican doctrines and practices as well as Reformed Theology. Bucer was originally a memb ...

,

Wolfgang Capito, and

Johannes Brenz as well as

Landgrave Philip of Hesse opposed the execution of Anabaptists.

Ulrich Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a Swiss Christian theologian, musician, and leader of the Reformation in Switzerland. Born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swis ...

demanded the expulsion of persons who did not accept the Reformed beliefs, in some cases the execution of Anabaptist leaders. The young

Michael Servetus also defended tolerance since 1531, in his letters to

Johannes Oecolampadius, but during those years some Protestant theologians such as Bucer and Capito publicly expressed they thought he should be persecuted. The trial against Servetus, an

Antitrinitarian, in Geneva was not a case of church discipline but a criminal procedure based on the legal code of the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. Denying the Trinity doctrine was long considered to be the same as

atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the Existence of God, existence of Deity, deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the ...

in all churches. The Anabaptists made a considerable contribution to the development of tolerance in the early-modern era by incessantly demanding freedom of conscience and standing up for it with their patient suffering.

Castellio

Sebastian Castellio

Sebastian Castellio (1515–1563) was a French Protestant theologian who in 1554 published under a pseudonym the pamphlet ''Whether heretics should be persecuted (De haereticis, an sint persequendi)'' criticizing

John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

's execution of

Michael Servetus: "When Servetus fought with reasons and writings, he should have been repulsed by reasons and writings." Castellio concluded: "We can live together peacefully only when we control our intolerance. Even though there will always be differences of opinion from time to time, we can at any rate come to general understandings, can love one another, and can enter the bonds of peace, pending the day when we shall attain unity of faith." Castellio is remembered for the often quoted statement, "To kill a man is not to protect a doctrine, but it is to kill a man.

Bodin

Jean Bodin

Jean Bodin (; ; – 1596) was a French jurist and political philosopher, member of the Parlement of Paris and professor of law in Toulouse. Bodin lived during the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation and wrote against the background of reli ...

(1530–1596) was a French Catholic jurist and political philosopher. His Latin work ''Colloquium heptaplomeres de rerum sublimium arcanis abditis'' ("The Colloqium of the Seven") portrays a conversation about the nature of truth between seven cultivated men from diverse religious or philosophical backgrounds: a natural philosopher, a Calvinist, a Muslim, a Roman Catholic, a Lutheran, a Jew, and a skeptic. All agree to live in mutual respect and tolerance.

Montaigne

Michel de Montaigne

Michel Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne ( ; ; ; 28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592), commonly known as Michel de Montaigne, was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularising the the essay ...

(1533–1592), French Catholic essayist and statesman, moderated between the Catholic and Protestant sides in the

Wars of Religion. Montaigne's theory of skepticism led to the conclusion that we cannot precipitously decide the error of others' views. Montaigne wrote in his famous "Essais": "It is putting a very high value on one's conjectures, to have a man roasted alive because of them...To kill people, there must be sharp and brilliant clarity."

Edict of Torda

In 1568, King

John II Sigismund of Hungary, encouraged by his Unitarian Minister Francis David (Dávid Ferenc), issued the

Edict of Torda

The Edict of Torda (, , ) was a decree that authorized local communities to freely elect their preachers in the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom of John Sigismund Zápolya. The delegates of the Three Nations of Transylvaniathe Hungarian nobility, Hungari ...

decreeing religious toleration of all Christian denominations except

Romanian Orthodoxy. It did not apply to Jews or Muslims but was nevertheless an extraordinary achievement of religious tolerance by the standards of 16th-century Europe.

Maximilian II

In 1571, Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian II granted religious toleration to the nobles of Lower Austria, their families and workers.

The Warsaw Confederation, 1573

The

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

had a long tradition of religious freedom. The right to worship freely was a basic right given to all inhabitants of the Commonwealth throughout the 15th and early 16th centuries, however complete freedom of religion was officially recognized in the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

in 1573 in the

Warsaw Confederation. The Commonwealth kept religious-freedom laws during an era when religious persecution was an everyday occurrence in the rest of Europe.

The Warsaw Confederation was a private compact signed by representatives of all the major religions in Polish and Lithuanian society, in which they pledged each other mutual support and tolerance. The confederation was incorporated into the

Henrican articles, which constituted a virtual Polish–Lithuanian constitution.

Edict of Nantes

The

Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

, issued on April 13, 1598, by

Henry IV of France

Henry IV (; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry (''le Bon Roi Henri'') or Henry the Great (''Henri le Grand''), was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 16 ...

, granted Protestants—notably

Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

—substantial rights in a nation where Catholicism was the state religion. The main concern was civil unity—the edict separated civil law from religious rights, treated non-Catholics as more than mere schismatics and heretics for the first time, and opened a path for secularism and tolerance. In offering general freedom of conscience to individuals, the edict offered many specific concessions to the Protestants, such as amnesty and the reinstatement of their civil rights, including the right to work in any field or for the State, and to bring grievances directly to the king. The edict marked the end of the religious wars in France that tore apart the population during the second half of the 16th century.

The Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1685 by

King Louis XIV with the

Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (18 October 1685, published 22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to prac ...

, leading to renewed persecution of Protestants in France. Although strict enforcement of the revocation was relaxed during the reign of

Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

, it was not until 102 years later, in 1787, when

Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

signed the

Edict of Versailles

The Edict of Versailles, also known as the Edict of Tolerance, was an official act that gave non-Catholics in France the access to civil rights formerly denied to them, which included the right to contract marriages without having to convert to t ...

—known as the

Edict of Tolerance—that civil status and rights to form congregations by Protestants were restored.

The Enlightenment

Beginning in the

Enlightenment commencing in the 1600s, politicians and commentators began formulating theories of religious toleration and basing legal codes on the concept. A distinction began to develop between ''civil tolerance'', concerned with "the policy of the state towards religious dissent"., and ''ecclesiastical tolerance'', concerned with the degree of diversity tolerated within a particular church.

Milton

John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

(1608–1674), English Protestant poet and essayist, called in the ''

Areopagitica'' for "the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties" (applied, however, only to the conflicting Protestant denominations, and not to atheists, Jews, Muslims or even Catholics). "Milton argued for

disestablishment as the only effective way of achieving broad toleration. Rather than force a man's conscience, government should recognize the persuasive force of the gospel."

Rudolph II

In 1609,

Rudolph II decreed religious toleration in

Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

.

In the American colonies

In 1636,

Roger Williams

Roger Williams (March 1683) was an English-born New England minister, theologian, author, and founder of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Pl ...

and companions at the foundation of

Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

entered into a compact binding themselves "to be obedient to the majority only in civil things". Williams spoke of "democracie or popular government." Lucian Johnston writes, "Williams' intention was to grant an infinitely greater religious liberty than what existed anywhere in the world outside of the Colony of Maryland." In 1663, Charles II granted the colony a charter guaranteeing complete religious toleration.

Also in 1636,

Congregationalist Thomas Hooker and a group of companions founded

Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

. They combined the

democratic form of government that had been developed by the

Separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, regional, governmental, or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seekin ...

Congregationalists in

Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes spelled Plimouth) was the first permanent English colony in New England from 1620 and the third permanent English colony in America, after Newfoundland and the Jamestown Colony. It was settled by the passengers on t ...

(

Pilgrim Fathers) with unlimited freedom of conscience. Like Martin Luther, Hooker argued that as faith in Jesus Christ was the free gift of the Holy Spirit it could not be forced on a person.

In 1649 Maryland passed the

Maryland Toleration Act

The Maryland Toleration Act, also known as the Act Concerning Religion, was the first law in North America requiring religious tolerance for Christians. It was passed on April 21, 1649, by the assembly of the Province of Maryland, Maryland colon ...

, also known as the Act Concerning Religion, a law mandating religious tolerance for Trinitarian Christians only (excluding

Nontrinitarian

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the orthodox Christian theology of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essence ( ...

faiths). Passed on September 21, 1649 by the assembly of the Maryland colony, it was the first law requiring religious tolerance in the British North American colonies. The

Calvert family sought enactment of the law to protect Catholic settlers and some of the other denominations that did not conform to the dominant

Anglicanism

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

of England and her colonies.

In 1657,

New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam (, ) was a 17th-century Dutch Empire, Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''Factory (trading post), fac ...

, governed by Dutch

Calvinists, granted religious toleration to Jews. They had fled from Portuguese persecution in Brazil.

In the

Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn, who received the land through a grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania was derived from ...

,

William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer, religious thinker, and influential Quakers, Quaker who founded the Province of Pennsylvania during the British colonization of the Americas, British colonial era. An advocate of democracy and religi ...

and his fellow

Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

heavily imprinted their religious values of toleration on the Pennsylvania government. The Pennsylvania 170

Charter of Privilegesextended religious freedom to all monotheists, and government was open to all Christians.

Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

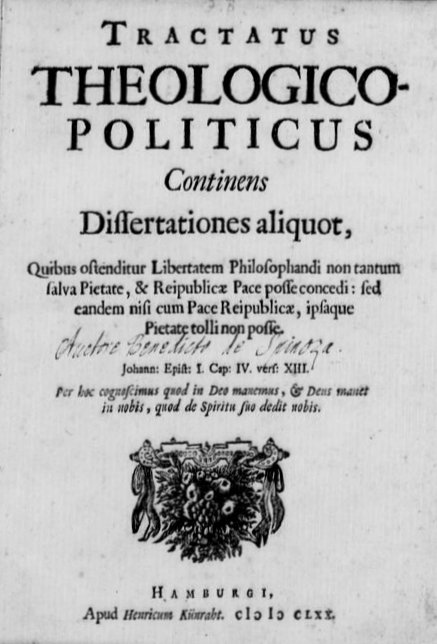

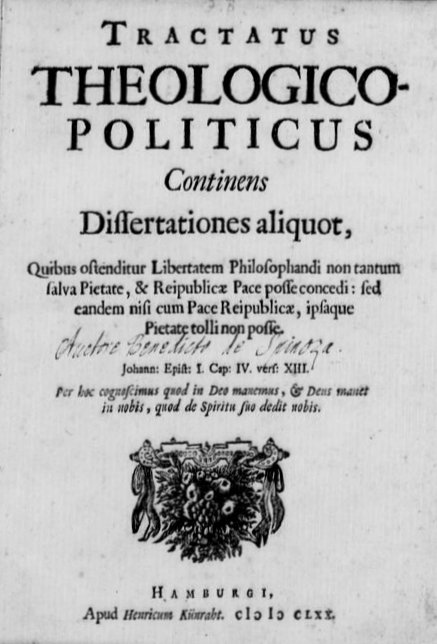

(1632–1677) was a Dutch Jewish philosopher. He published the

Theological-Political Treatise anonymously in 1670, arguing (according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) that "the freedom to philosophize can not only be granted without injury to piety and the peace of the Commonwealth, but that the peace of the Commonwealth and Piety are endangered by the suppression of this freedom", and defending, "as a political ideal, the tolerant, secular, and democratic polity". After

interpreting certain Biblical texts, Spinoza opted for tolerance and freedom of thought in his conclusion that "every person is in duty bound to adapt these religious dogmas to his own understanding and to interpret them for himself in whatever way makes him feel that he can the more readily accept them with full confidence and conviction."

Locke

English philosopher

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

(1632–1704) published

A Letter Concerning Toleration in 1689. Locke's work appeared amidst a fear that Catholicism might be taking over England, and responds to the problem of religion and government by proposing religious toleration as the answer.

Unlike

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

, who saw uniformity of religion as the key to a well-functioning civil society, Locke argued that more religious groups actually prevent civil unrest. In his opinion, civil unrest results from confrontations caused by any magistrate's attempt to prevent different religions from being practiced, rather than tolerating their proliferation. However, Locke denies religious tolerance for Catholics, for political reasons, and also for atheists because "Promises, covenants, and oaths, which are the bonds of human society, can have no hold upon an atheist". A passage Locke later added to ''

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding'' is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 (although dated 1690) with the printed title ''An Essay Concerning Humane Understand ...

'' questioned whether atheism was necessarily inimical to political obedience.

Bayle

Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle (; 18 November 1647 – 28 December 1706) was a French philosopher, author, and lexicographer. He is best known for his '' Historical and Critical Dictionary'', whose publication began in 1697. Many of the more controversial ideas ...

(1647–1706) was a French Protestant scholar and philosopher who went into exile in Holland. In his "

Dictionnaire Historique et Critique" and "Commentaire Philosophique" he advanced arguments for religious toleration (though, like some others of his time, he was not anxious to extend the same protection to Catholics he would to differing Protestant sects). Among his arguments were that every church believes it is the right one so "a heretical church would be in a position to persecute the true church". Bayle wrote that "the erroneous conscience procures for error the same rights and privileges that the orthodox conscience procures for truth."

Bayle was repelled by the use of scripture to justify coercion and violence: "One must transcribe almost the whole New Testament to collect all the Proofs it affords us of that Gentleness and Long-suffering, which constitute the distinguishing and essential Character of the Gospel." He did not regard toleration as a danger to the state, but to the contrary: "If the Multiplicity of Religions prejudices the State, it proceeds from their not bearing with one another but on the contrary endeavoring each to crush and destroy the other by methods of Persecution. In a word, all the Mischief arises not from Toleration, but from the want of it."

English Toleration Act 1688

Following the

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

, when the Dutch king

William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

came to the English throne, the

Toleration Act 1688 adopted by the English Parliament allowed freedom of worship to Nonconformists who had pledged to the oaths of Allegiance and Supremacy and rejected

transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (; Greek language, Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of sacramental bread, bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and ...

. The Nonconformists were Protestants who dissented from the Church of England such as Baptists and Congregationalists. They were allowed their own places of worship and their own teachers, if they accepted certain oaths of allegiance. The Act, however, did not apply to Catholics and non-trinitarians, and continued the existing social and political disabilities of Dissenters, including their exclusion from political office and from the universities of

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

and

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

.

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet, the French writer, historian and philosopher known as

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

(1694–1778) published his ''

Treatise on Toleration'' in 1763. In it he attacked religious views, but also said, "It does not require great art, or magnificently trained eloquence, to prove that Christians should tolerate each other. I, however, am going further: I say that we should regard all men as our brothers. What? The Turk my brother? The Chinaman my brother? The Jew? The Siam? Yes, without doubt; are we not all children of the same father and creatures of the same God?" On the other hand, Voltaire in his writings on religion was spiteful and intolerant of the practice of the Christian religion, and Orthodox rabbi

Joseph Telushkin has claimed that the most significant of Enlightenment hostility against Judaism was found in Voltaire.

[ Prager, D; Telushkin, J. ''Why the Jews?: The Reason for Antisemitism''. New York: ]Simon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster LLC (, ) is an American publishing house owned by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts since 2023. It was founded in New York City in 1924, by Richard L. Simon and M. Lincoln Schuster. Along with Penguin Random House, Hachette Book Group US ...

, 1983. pp. 128–29.

Lessing

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (; ; 22 January 1729 – 15 February 1781) was a German philosopher, dramatist, publicist and art critic, and a representative of the Enlightenment era. His plays and theoretical writings substantially influenced the dev ...

(1729–1781), German dramatist and philosopher, trusted in a "Christianity of Reason", in which human reason (initiated by criticism and dissent) would develop, even without help by divine revelation. His plays about Jewish characters and themes, such as "Die Juden" and "

Nathan der Weise", "have usually been considered impressive pleas for social and religious toleration". The latter work contains the famous parable of the three rings, in which three sons represent the three Abrahamic religions, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Each son believes he has the one true ring passed down by their father, but judgment on which is correct is reserved to God.

French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

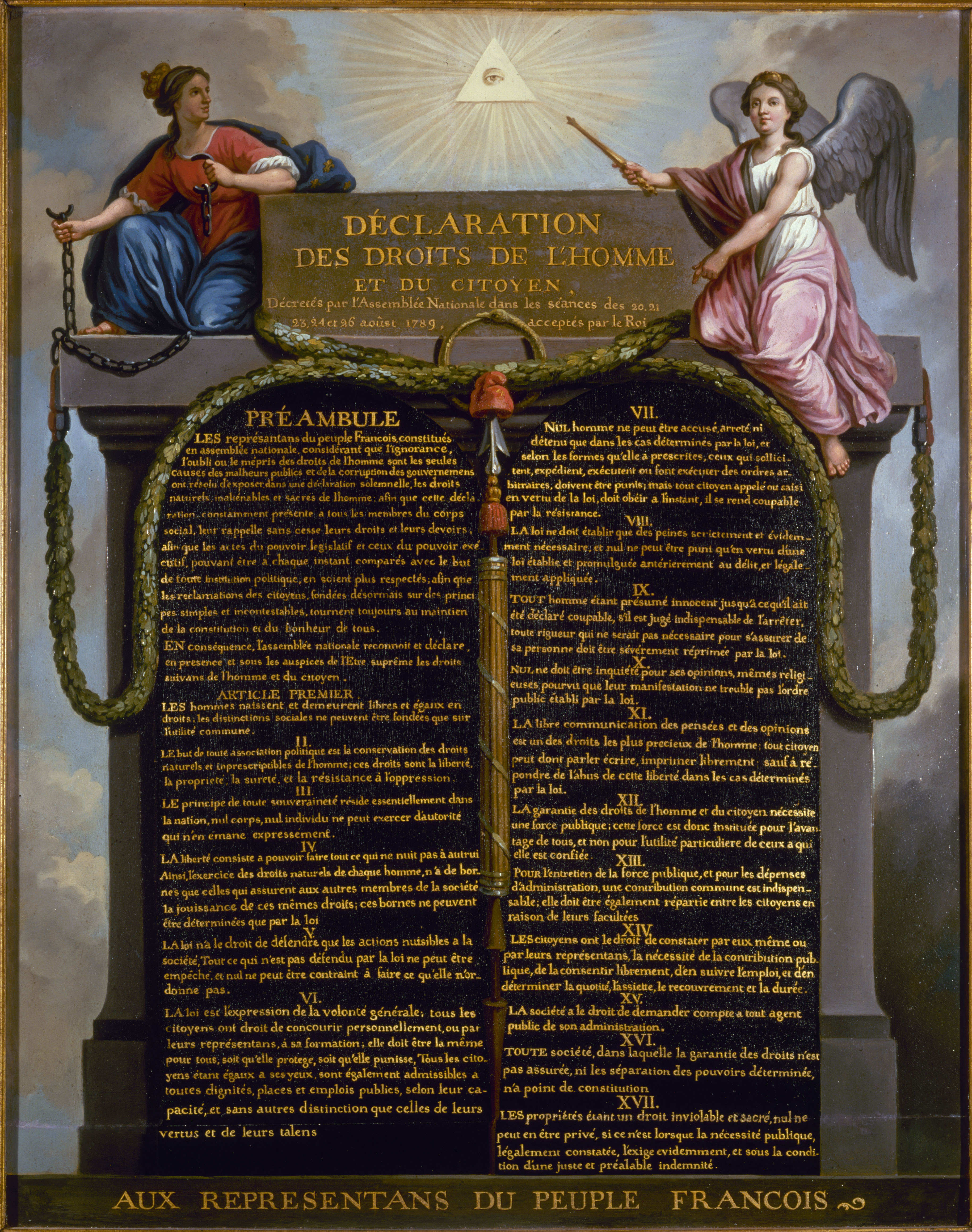

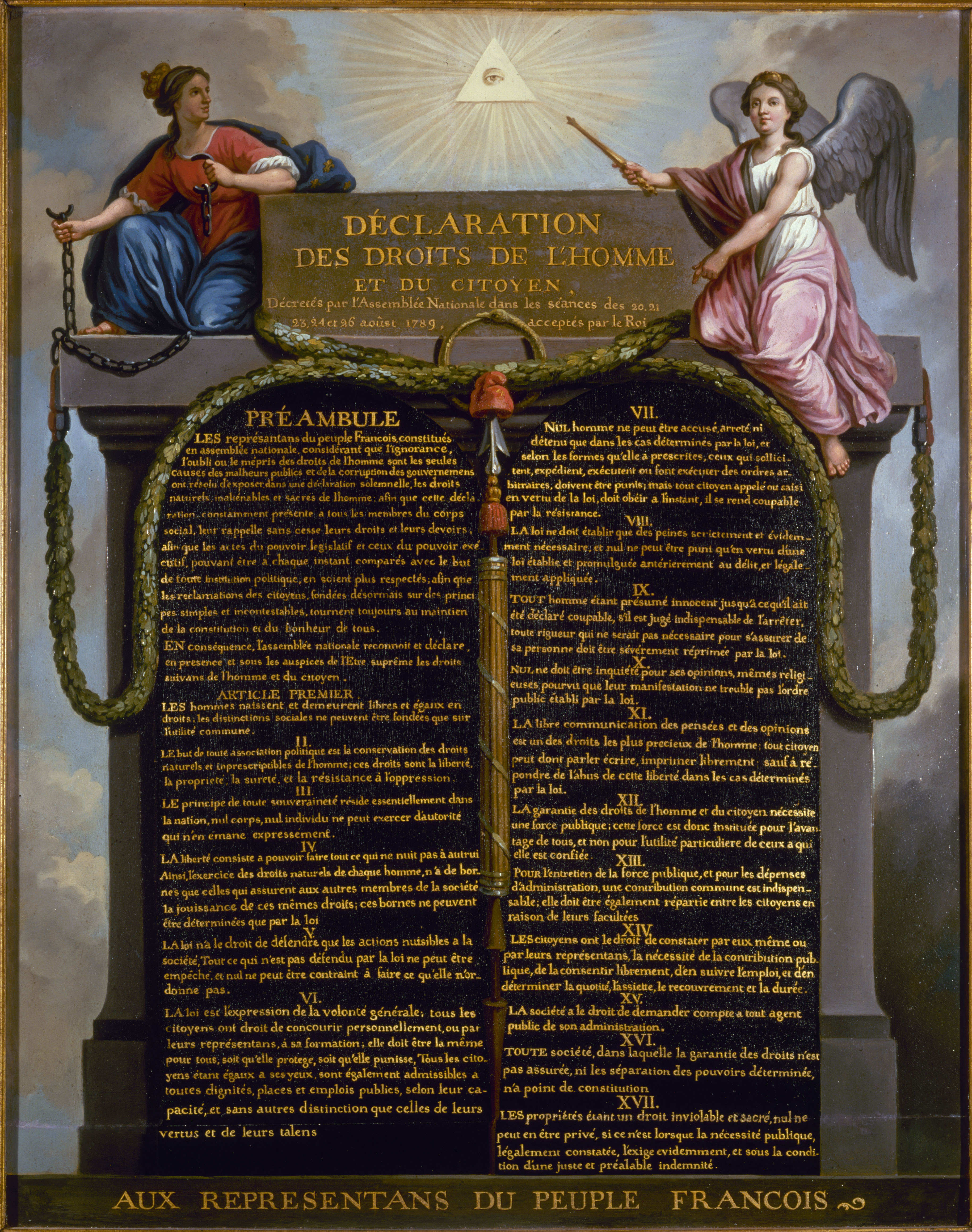

The

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human and civil rights document from the French Revolution; the French title can be translated in the modern era as "Decl ...

(1789), adopted by the

National Constituent Assembly during the

French Revolution, states in Article 10: "No-one shall be interfered with for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their practice does not disturb public order as established by the law." ("Nul ne doit être inquiété pour ses opinions, mêmes religieuses, pourvu que leur manifestation ne trouble pas l'ordre public établi par la loi.")

Napoleon emancipated the Jews in countries his imperial army conquered, expanding the impact of the French Declaration of Rights of Man.

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution

The

First Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution prevents Federal government of the United States, Congress from making laws respecting an Establishment Clause, establishment of religion; prohibiting the Free Exercise Cla ...

, ratified along with the rest of the

Bill of Rights on December 15, 1791, included the following words: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..."

In 1802, Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to the

Danbury Baptists Association in which he said:

"...I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should 'make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,' thus building a wall of separation between Church & State."

In the nineteenth century

The process of legislating religious toleration went unevenly forward, while philosophers continued to discuss the underlying rationale.

Roman Catholic Relief Act

The

Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 adopted by the Parliament in 1829 repealed the last of the civil restrictions aimed at Catholic citizens of the United Kingdom.

Mill

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

's arguments in "

On Liberty

''On Liberty'' is an essay published in 1859 by the English philosopher John Stuart Mill. It applied Mill's ethical system of utilitarianism to society and state. Mill suggested standards for the relationship between authority and liberty. H ...

" (1859) in support of the freedom of speech were phrased to include a defense of religious toleration:

Let the opinions impugned be the belief of God and in a future state, or any of the commonly received doctrines of morality... But I must be permitted to observe that it is not the feeling sure of a doctrine (be it what it may) which I call an assumption of infallibility. It is the undertaking to decide that question ''for others'', without allowing them to hear what can be said on the contrary side. And I denounce and reprobate this pretension not the less if it is put forth on the side of my most solemn convictions.

Syllabus of Errors

The

Syllabus of Errors was issued by

Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX (; born Giovanni Maria Battista Pietro Pellegrino Isidoro Mastai-Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878. His reign of nearly 32 years is the longest verified of any pope in hist ...

in 1864. It condemns 80 errors or

heresies, including the following propositions regarding religious toleration:

Renan

In his 1882 essay "

What is a Nation?", French historian and philosopher

Ernest Renan proposed a definition of nationhood based on "a spiritual principle" involving shared memories, rather than a common religious, racial or linguistic heritage. Thus members of any religious group could participate fully in the life of the nation. "You can be French, English, German, yet Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, or practicing no religion".

In the twentieth century

In 1948, the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

General Assembly adopted Article 18 of the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal D ...

, which states:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance

Even though not formally legally binding, the Declaration has been adopted in or influenced many national constitutions since 1948. It also serves as the foundation for a growing number of international treaties and national laws and international, regional, national and sub-national institutions protecting and promoting human rights including the

freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

.

In 1965, the Catholic

Vatican II

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilic ...

Council issued the decree ''

Dignitatis humanae'' (Religious Freedom) that states that all people must have the right to religious freedom. The Catholic

1983 Code of Canon Law

The 1983 ''Code of Canon Law'' (abbreviated 1983 CIC from its Latin title ''Codex Iuris Canonici''), also called the Johanno-Pauline Code, is the "fundamental body of Ecclesiastical Law, ecclesiastical laws for the Latin Church". It is the sec ...

states:

In 1986, the first

World Day of Prayer for Peace was held in Assisi. Representatives of one hundred and twenty different religions came together for prayer.

In 1988, in the spirit of

Glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

,

Soviet general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

promised increased religious toleration.

UN Declaration on Religious Tolerance (1981)—critique

The landmark document '

Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief,' proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly on 25 November 1981, has faced substantial criticism for scope, non-effective implementation, and conceptual clarity.

Article 1(1) outlines that "UN declarations are not international treaties; rather, they are statements of agreed standards of action and moral obligation." This non-binding nature means a lack of legal enforceability, and as a result, signatory states are neither under the legal obligations to take concrete actions nor face accountability mechanisms.

Although religious minorities suffer most from such religious discrimination, the UN Declaration notably omits explicit reference to

religious minorities. While the needs of religious communities or congregations are contemplated, religious minorities are not recognized.

In article 2 of the Declaration, the definitions of the terms “intolerance and discrimination” appear to be equating with each other. Making a distinction between “intolerance” and “discrimination,” Natan Lerner has underscored the frequent application of the term “discrimination” in international treaties with its definite legal meaning, while the term “intolerance” is marked by impreciseness and ambiguity.

Hinduism

The

Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' (, , from wikt:ऋच्, ऋच्, "praise" and wikt:वेद, वेद, "knowledge") is an ancient Indian Miscellany, collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canoni ...

says ''Ekam Sath Viprah Bahudha Vadanti'' which translates to "The truth is One, but sages call it by different Names". Consistent with this tradition,

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

chose to be a secular country even though it was divided by

partitioning on religious lines. Whatever intolerance Hindu scholars displayed towards other religions was subtle and symbolic and most likely was done to present a superior argument in defence of their own faith. Traditionally, Hindus showed their intolerance by withdrawing and avoiding contact with those whom they held in contempt, instead of using violence and aggression to strike fear in their hearts.

Pluralism and tolerance of diversity are built into

Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

theology. India's long history is a testimony to its tolerance of religious diversity.

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

came to

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

with

St. Thomas in the first century CE, long before it became popular in the West.

Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

came to India after the

Jewish temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE and the Jews were expelled from their homeland. In a recent book titled "Who are the Jews of India?" (University of California Press, 2000), author

Nathan Katz observes that India is the only country where the

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

were not persecuted. The

Indian chapter is one of the happiest of the

Jewish Diaspora

The Jewish diaspora ( ), alternatively the dispersion ( ) or the exile ( ; ), consists of Jews who reside outside of the Land of Israel. Historically, it refers to the expansive scattering of the Israelites out of their homeland in the Southe ...

. Both Christians and Jews have existed in a predominant Hindu India for centuries without being persecuted. Zoroastrians from

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

(present day

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

) entered India in the 7th century to flee Islamic conquest. They are known as

Parsis

The Parsis or Parsees () are a Zoroastrian ethnic group in the Indian subcontinent. They are descended from Persian refugees who migrated to the Indian subcontinent during and after the Arab-Islamic conquest of Iran in the 7th century, w ...

in India. The

Parsis

The Parsis or Parsees () are a Zoroastrian ethnic group in the Indian subcontinent. They are descended from Persian refugees who migrated to the Indian subcontinent during and after the Arab-Islamic conquest of Iran in the 7th century, w ...

are an affluent community in the city of

Mumbai

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial capital and the most populous city proper of India with an estimated population of 12 ...

. Once treated as foreigners, they remain a minority community, yet still housing the richest business families in India; for example, the

Tata family controls a huge industrial empire in various parts of the country.

Mrs. Indira Gandhi, the powerful Prime Minister of

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

(1966–77; 1980–84), was married to

Feroz Gandhi, a Parsi (no relation to

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

).

Daoism

Daoism is the only indigenous religion rooted in the land of China, and it constitutes a vital component of Chinese civilization. Throughout its development over more than two millennia, Daoism has demonstrated remarkable inclusiveness—embracing not only religious and cultural traditions within the Chinese world but also those originating beyond it. This openness has enabled Daoism to endure through dynastic transitions, foreign invasions, and periods of social upheaval, continually adapting while preserving its core values.

The highest object of Daoist belief is the Dao, which, as “that from which all things arise,” is regarded as the primordial origin, the fundamental force, and the underlying principle that governs the ceaseless transformation and movement of the cosmos. The Dao is understood as the ontological ground of all beings. Accordingly, Daoism venerates the “Great Dao,” a formless, indeterminate source—often described as ''wu'' (無), meaning “non-being” or “non-differentiation.” This conception of the Dao as inherently undivided and without fixed characteristics provides a profound philosophical foundation for Daoism’s religious tolerance. Since the Dao encompasses all things without exclusion, Daoist cosmology naturally resists rigid binaries and dogmatic boundaries. In a world rooted in fluid transformation, coexistence is not just ideal—it is ontological.

Doctrinally, Daoism advocates non-contention (''wu zheng'' 無爭) and harmonious coexistence with others. These values are clearly articulated in the ''Daodejing'' (《道德经》), particularly in Chapter 16:

“To know eternity is to embrace whatever comes;

To embrace whatever comes is to be just;

To be just is to be complete;

To be complete is to be like Heaven;

To be like Heaven is to return to Tao.”

This passage expresses a cascading ethical progression: when individuals come to understand the eternal and unchanging principles of the universe (''chang'' 常, “constancy”), they develop a heart of tolerance and acceptance (''rong'' 容) toward all things. From this tolerance arises a sense of impartiality and fairness (''gong'' 公). Impartiality fosters completeness and thoroughness (''quan'' 全) in one’s conduct. Acting with such wholeness aligns a person with the natural order (''tian'' 天, “Heaven”). To live in accordance with the principles of Heaven is to be in harmony with the Dao—the Way. And to follow the Dao is to enter a state of lasting stability and peace, where one remains free from harm throughout life. This sequence illustrates a core Daoist vision of tolerance, peace, generativity, and balance—values that support engagement with other religious traditions in a spirit of concord and moderation. Rather than viewing diversity as a threat, Daoism frames it as a reflection of the Dao’s boundless creativity.

Historically, this inclusive and adaptive spirit enabled Daoism to engage in mutual exchange and synthesis with Confucianism and Buddhism. While each tradition retained its distinctive doctrines, they also influenced one another profoundly. One illustrative example is the Daoist adoption of Confucian moral values; the ''Taishang Ganying Pian'' (《太上感應篇》), compiled during the Song dynasty, is a seminal text that integrates Daoist metaphysics with Confucian ethics. The work emphasizes virtue, retribution, and moral responsibility, demonstrating how Daoism can incorporate external frameworks while maintaining its spiritual essence.

Through centuries of interaction, the three traditions—Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism—gradually converged to form a syncretic paradigm often described as “the unity of the Three Teachings” (''san jiao he yi'' 三教合一). This triadic model became deeply embedded in Chinese culture, shaping rituals, education, governance, and everyday ethics. Rather than competing for dominance, these traditions found ways to coexist, offering the Chinese people a multifaceted yet coherent spiritual worldview. This model of integration rather than exclusion is a testament to the Daoist ethos of accommodation and harmony.

In today’s world, marked by religious pluralism, rising fundamentalism, and frequent intercultural tensions, Daoism’s example remains highly relevant. Its commitment to coexistence, openness to diversity, and refusal to impose rigid doctrinal boundaries offer valuable insights for contemporary discussions about religious tolerance and interfaith dialogue. By cultivating inward balance and outward harmony, Daoism reminds us that true peace begins with recognizing the interconnectedness of all beings. In this sense, the Dao is not merely a metaphysical principle—it is a lived ethic, guiding individuals and societies toward a more inclusive, compassionate world.

Islam

Religious tolerance in Quran