reign of terror on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

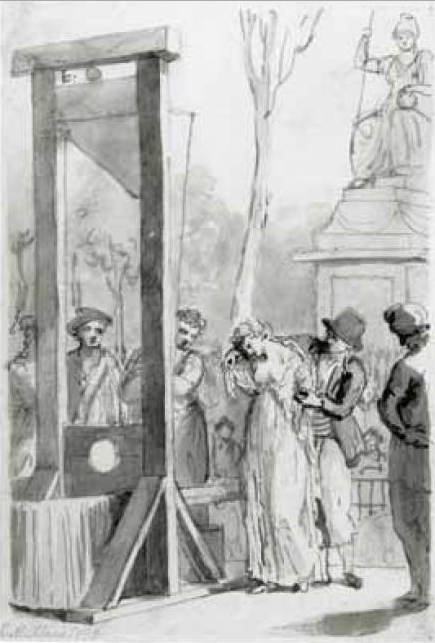

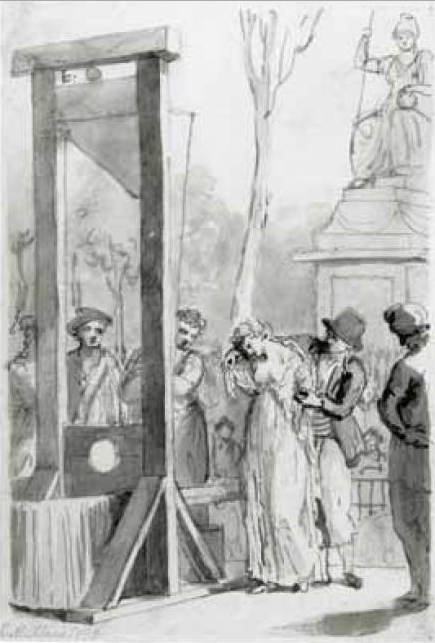

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public executions took place in response to the

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public executions took place in response to the

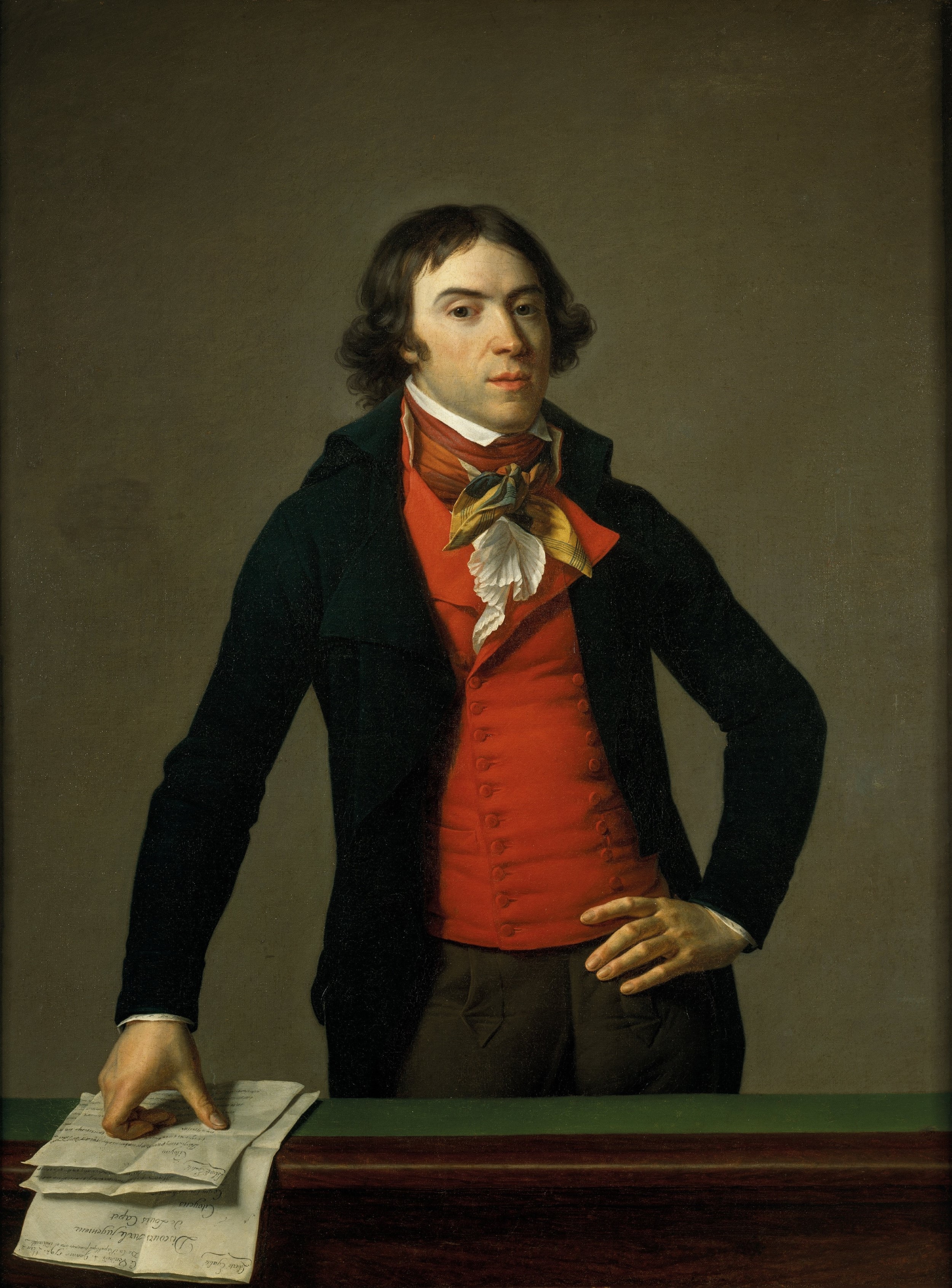

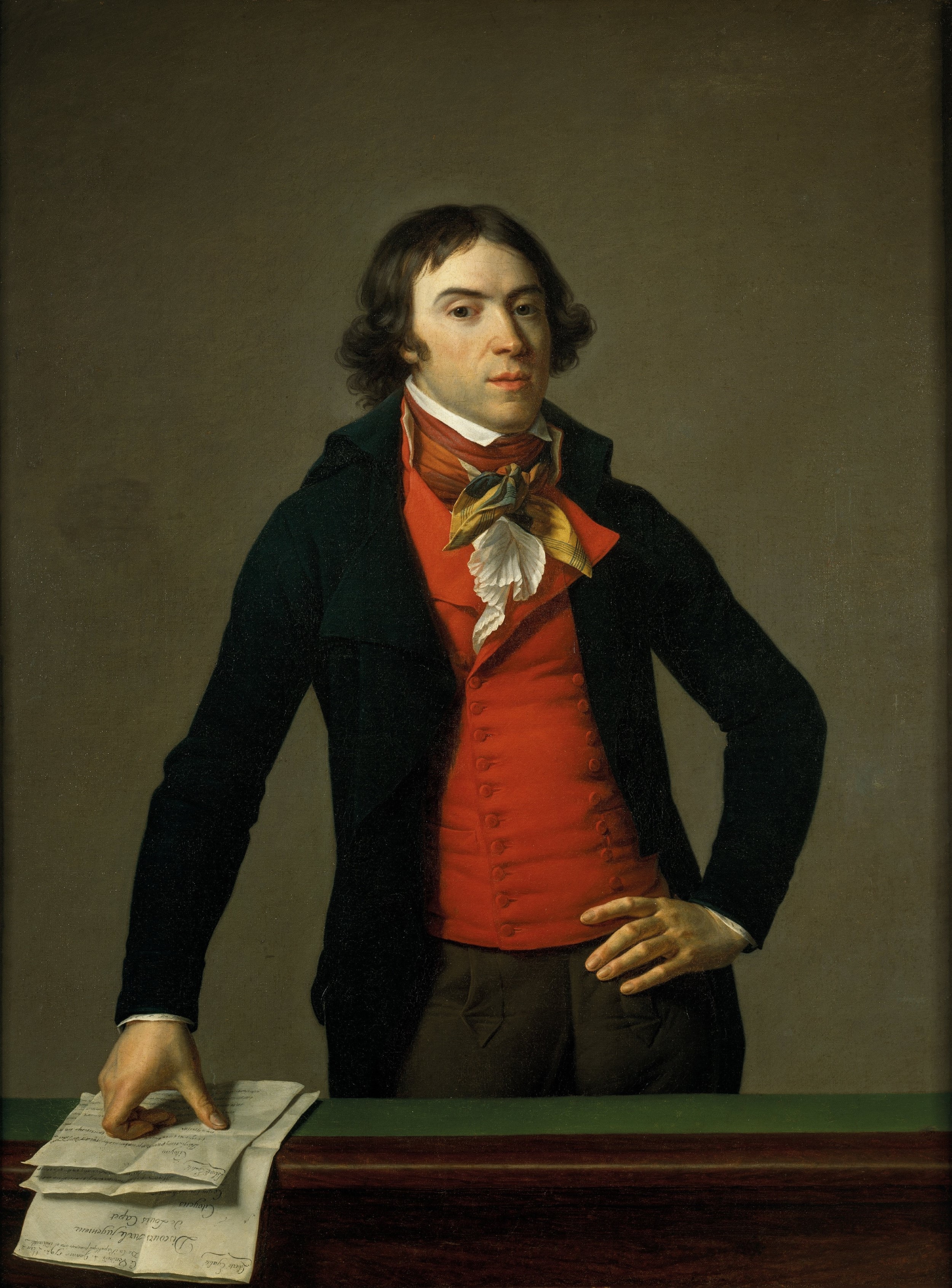

Maximilien Robespierre: Justification of the Use of Terror

."

At the beginning of the French Revolution, the surrounding monarchies did not show great hostility towards the rebellion. Though mostly ignored,

At the beginning of the French Revolution, the surrounding monarchies did not show great hostility towards the rebellion. Though mostly ignored,

During the Reign of Terror, the ''

During the Reign of Terror, the ''

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public executions took place in response to the

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public executions took place in response to the Federalist revolts

The Federalist revolts were uprisings that broke out in various parts of France in the summer of 1793, during the French Revolution. They were prompted by resentments in France's provincial cities about increasing centralisation of power in Pa ...

, revolutionary fervour, anticlerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, ...

sentiment, and accusations of treason by the Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety () was a committee of the National Convention which formed the provisional government and war cabinet during the Reign of Terror, a violent phase of the French Revolution. Supplementing the Committee of General D ...

. While terror was never formally instituted as a legal policy by the Convention, it was more often employed as a concept.

Historians disagree when exactly "the Terror" began. Some consider it to have begun in 1793, often giving the date as 5 September or 10 March, when the Revolutionary Tribunal

The Revolutionary Tribunal (; unofficially Popular Tribunal) was a court instituted by the National Convention during the French Revolution for the trial of political offenders. In October 1793, it became one of the most powerful engines of ...

came into existence. Others cite the earlier September Massacres

The September Massacres were a series of killings and summary executions of prisoners in Paris that occurred in 1792 from 2 September to 6 September during the French Revolution. Between 1,176 and 1,614 people were killed by ''sans-culottes'' ...

in 1792, or even July 1789 when the first killing of the revolution occurred. Will Durant stated that "strictly, it should be dated from the Law of Suspects

:''Note: This decree should not be confused with the Law of General Security (), also known as the "Law of Suspects," adopted by Napoleon III in 1858 that allowed punishment for any prison action, and permitted the arrest and deportation, without ...

, September 17, 1793, to the execution of Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; ; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman, widely recognised as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. Robespierre ferv ...

, July 28, 1794."

The Terror concluded with the fall of Robespierre and his alleged allies in July 1794, in what is known as the Thermidorian Reaction

In the historiography of the French Revolution, the Thermidorian Reaction ( or ''Convention thermidorienne'', "Thermidorian Convention") is the common term for the period between the ousting of Maximilien Robespierre on 9 Thermidor II, or 27 J ...

. By then, 16,594 official death sentences had been dispensed throughout France since June 1793, of which 2,639 were in Paris alone. An additional 10,000 to 12,000 people had been executed without trial, and 10,000 had died in prison.

Background

Enlightenment thought

Enlightenment thought emphasized the importance ofrational thinking

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reason. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do, or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ab ...

and began challenging legal and moral foundations of society, providing the leaders of the Reign of Terror with new ideas about the role and structure of government. Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

's ''Social Contract'' argues that each person was born with rights, and they would come together in forming a government that would then protect those rights. Under the social contract, the government was required to act for the general will

In political philosophy, the general will () is the will of the people as a whole. The term was made famous by 18th-century Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It can be considered as an early, informal predecessor to the idea of a social ...

, which represented the interests of everyone rather than a few factions. Drawing from the idea of a general will, Robespierre felt that the French Revolution could result in a republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

built for the general will but only once those who fought against this ideal were expelled.Halsall, Paul. 9972020.Maximilien Robespierre: Justification of the Use of Terror

."

Internet Modern History Sourcebook

The Internet History Sourcebooks Project is located at the Fordham University History Department and Center for Medieval Studies. It is a web site with modern, medieval and ancient primary source documents, maps, secondary sources, bibliographies, ...

. US: Fordham University

Fordham University is a Private university, private Society of Jesus, Jesuit research university in New York City, United States. Established in 1841, it is named after the Fordham, Bronx, Fordham neighborhood of the Bronx in which its origina ...

, Retrieved 25 June 2020. Those who resisted the government were deemed "tyrants" fighting against the virtue and honor of the general will. The leaders felt that their ideal version of government was threatened from the inside and outside of France, and terror was the only way to preserve the dignity of the republic created from French Revolution.

The writings of Baron de Montesquieu, another Enlightenment thinker of the time, also greatly influenced Robespierre. Montesquieu's ''The Spirit of Law

''The Spirit of Law'' (French: ''De l'esprit des lois'', originally spelled ''De l'esprit des loix''), also known in English as ''The Spirit of heLaws'', is a treatise on political theory, as well as a pioneering work in comparative law by Mont ...

'' defines a core principle of a democratic government: virtue

A virtue () is a trait of excellence, including traits that may be morality, moral, social, or intellectual. The cultivation and refinement of virtue is held to be the "good of humanity" and thus is Value (ethics), valued as an Telos, end purpos ...

—described as "the love of laws and of our country." In Robespierre's speech to the National Convention

The National Convention () was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the ...

on 5 February 1794, he regards virtue as being the "fundamental principle of popular or democratic government." This was, in fact, the same virtue defined by Montesquieu almost 50 years prior. Robespierre believed the virtue needed for any democratic government was extremely lacking in the French people. As a result, he decided to weed out those he believed could never possess this virtue. The result was a continual push towards Terror. The Convention used this as justification for the course of action to "crush the enemies of the revolution…let the laws be executed…and let liberty be saved."

Threats of foreign invasion

At the beginning of the French Revolution, the surrounding monarchies did not show great hostility towards the rebellion. Though mostly ignored,

At the beginning of the French Revolution, the surrounding monarchies did not show great hostility towards the rebellion. Though mostly ignored, Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

was later able to find support in Leopold II of Austria (brother of Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

) and Frederick William II of Prussia

Frederick William II (; 25 September 1744 – 16 November 1797) was King of Prussia from 1786 until his death in 1797. He was also the prince-elector of Brandenburg and (through the Orange-Nassau inheritance of his grandfather) sovereign princ ...

. On 27 August 1791, these foreign leaders made the Pillnitz Declaration, saying they would restore the French monarch if other European rulers joined. In response to what they viewed to be the meddling of foreign powers, France declared war on 20 April 1792. However, at this point, the war was only Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

and Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

against France.

Massive reforms of military institutions, while very effective in the long run, presented the initial problems of inexperienced forces and leaders of questionable political loyalty. In the time it took for officers of merit to use their new freedoms to climb the chain of command, France suffered. Many of the early battles were definitive losses for the French. There was the constant threat of the Austro-Prussian forces which were advancing easily toward the capital, threatening to destroy Paris if the monarch was harmed. This series of defeats, coupled with militant uprisings and protests within the borders of France, pushed the government to resort to drastic measures to ensure the loyalty of every citizen, not only to France but more importantly to the revolution.

While this series of losses was eventually broken, the reality of what might have happened if they persisted hung over France. In September 1792 the French won a critical victory at Valmy, preventing an Austro-Prussian invasion. While the French military had stabilized and was producing victories by the time the Reign of Terror officially began, the pressure to succeed in this international struggle acted as justification for the government to pursue its actions. It was not until after the execution of Louis XVI

Louis XVI, former Bourbon King of France since the Proclamation of the abolition of the monarchy, abolition of the monarchy, was publicly executed on 21 January 1793 during the French Revolution at the ''Place de la Révolution'' in Paris. At Tr ...

and the annexation of the Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

that the other monarchies began to feel threatened enough to form the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition () was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797, initially against the constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French Republic that succeeded it. They were only loosely allied ...

. The coalition, consisting of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, Austria, Prussia, Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

, and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

began attacking France from all directions, besieging and capturing ports and retaking ground lost to France. With so many similarities to the first days of the Revolutionary Wars for the French government, with threats on all sides, unification of the country became a top priority. As the war continued and the Reign of Terror began, leaders saw a correlation between using terror and achieving victory. Well phrased by Albert Soboul, "terror, at first an improvised response to defeat, once organized became an instrument of victory." The threat of defeat and foreign invasion may have helped spur the origins of the Terror, but the timely coincidence of the Terror with French victories added justification to its growth.

Popular pressure

During the Reign of Terror, the ''

During the Reign of Terror, the ''sans-culottes

The (; ) were the working class, common people of the social class in France, lower classes in late 18th-century history of France, France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their ...

—the urban workers of France—''and the Hébertists put pressure on the National Convention delegates and contributed to the overall instability of France. The National Convention was bitterly split between the Montagnards and the Girondins

The Girondins (, ), also called Girondists, were a political group during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnards, they initiall ...

. The Girondins were more conservative leaders of the National Convention, while the Montagnards supported radical violence and pressures of the lower classes. Once the Montagnards gained control of the National Convention, they began demanding radical measures.

Moreover, the ''sans-culottes'' agitated leaders to inflict punishments on those who opposed the interests of the poor. The ''sans-culottes'' violently demonstrated, pushing their demands and creating constant pressure for the Montagnards to enact reform. They fed the frenzy of instability and chaos by utilizing popular pressure during the Revolution. For example, they sent letters and petitions to the Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety () was a committee of the National Convention which formed the provisional government and war cabinet during the Reign of Terror, a violent phase of the French Revolution. Supplementing the Committee of General D ...

urging them to protect their interests and rights with measures such as taxation of foodstuffs that favored workers over the rich. They advocated for arrests of those deemed to oppose reforms against those with privilege, and the more militant members would advocate pillage in order to achieve the desired equality. The resulting instability caused problems that made forming the new republic and achieving full political support critical.

Religious upheaval

The Reign of Terror was characterized by a dramatic rejection of long-held religious authority, its hierarchical structure, and the corrupt and intolerant influence of thearistocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

and clergy. Religious elements that long stood as symbols of stability for the French people, were replaced by views on reason and scientific thought. The radical revolutionaries and their supporters desired a cultural revolution that would rid the French state of all Christian influence. This process began with the fall of the monarchy, an event that effectively defrocked the state of its sanctification by the clergy via the doctrine of Divine Right and ushered in an era of reason.

Many long-held rights and powers were stripped from the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and given to the state. In 1789, church lands were expropriated and priests killed or forced to leave France. Later in 1792, "refractory priests" were targeted and replaced with their secular counterpart from the Jacobin club

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution (), renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality () after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club () or simply the Jacobins (; ), was the most influential List of polit ...

. Not all religions experienced equal aggression; the Jewish community, on the contrary, received admittance into French citizenship in 1791. A Festival of Reason was held in the Notre Dame Cathedral

Notre-Dame de Paris ( ; meaning "Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris"), often referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the River Seine), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, France. It ...

, which was renamed "The Temple of Reason", and the traditional calendar was replaced with a new revolutionary one. The leaders of the Terror tried to address the call for these radical, revolutionary aspirations, while at the same time trying to maintain tight control on the de-Christianization movement that was threatening to the clear majority of the still devoted Catholic population of France. Robespierre used the event as a means to combat the "moral counterrevolution" taking place among his rivals. Additionally, he hoped to stem "the monster atheism" that was a result of the radical secularization in philosophical and social circles. The tension sparked by these conflicting objectives laid a foundation for the "justified" use of terror to achieve revolutionary ideals and rid France of the religiosity that revolutionaries believed was standing in the way.

Terror of the day

In the summer of 1793, leading politicians in France felt a sense of emergency between the widespread civil war and counter-revolution.Bertrand Barère

Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac (, 10 September 175513 January 1841) was a French politician, freemason, journalist, and one of the most prominent members of the National Convention, representing the Plain (a moderate political faction) during the ...

exclaimed on 5 September 1793 in the National Convention: "Let's make terror the order of the day!" This quote has frequently been interpreted as the beginning of a supposed "system of Terror", an interpretation no longer retained by historians today. Under the pressure of the radical ''sans-culottes'', the Convention agreed to institute a revolutionary army but refused to make terror the order of the day. According to French historian Jean-Clément Martin, there was no "system of terror" instated by the Convention between 1793 and 1794, despite the pressure from some of its members and the ''sans-culottes''. The members of the Convention were determined to avoid street violence such as the September Massacres

The September Massacres were a series of killings and summary executions of prisoners in Paris that occurred in 1792 from 2 September to 6 September during the French Revolution. Between 1,176 and 1,614 people were killed by ''sans-culottes'' ...

of 1792 by taking violence into their own hands as an instrument of government. The monarchist Jacques Cazotte who predicted the Terror was guillotined at the end of the month.

What Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; ; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman, widely recognised as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. Robespierre ferv ...

called "terror" was the fear that the "justice of exception" would inspire the enemies of the French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (), was founded on 21 September 1792 during the French Revolution. The First Republic lasted un ...

. He opposed the idea of terror as the order of the day, defending instead "justice" as the order of the day. In February 1794 in a speech he explains why this "terror" was necessary as a form of exceptional justice in the context of the revolutionary government:

Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

historian Albert Mathiez argues that such terror was a necessary reaction to the circumstances. Others suggest there were additional causes, including ideological and emotional.

Major events

On 10 March 1793 the National Convention set up theRevolutionary Tribunal

The Revolutionary Tribunal (; unofficially Popular Tribunal) was a court instituted by the National Convention during the French Revolution for the trial of political offenders. In October 1793, it became one of the most powerful engines of ...

. Among those charged by the tribunal, initially, about half of those arrested were acquitted, but the number dropped to about a quarter after the enactment of the Law of 22 Prairial

The Law of 22 Prairial, also known as the ''loi de la Grande Terreur'', the law of the Great Terror, was enacted on 10 June 1794 (22 Prairial of the Year II under the French Revolutionary Calendar). It was proposed by Georges Auguste Couthon bu ...

on 10 June 1794. In March, rebellion broke out in the Vendée

Vendée () is a department in the Pays de la Loire region in Western France, on the Atlantic coast. In 2019, it had a population of 685,442.de facto'' war-time government of France. The Committee oversaw the Reign of Terror. "During the Reign of Terror, at least 300,000 suspects were arrested; 17,000 were officially executed, and perhaps 10,000 died in prison or without trial."

On 2 June the Parisian ''sans-culottes'' surrounded the National Convention, calling for administrative and political purges, a fixed low price for bread, and a limitation of the electoral franchise to ''sans-culottes'' alone. With the backing of the  In early December, Robespierre accused Danton in the Jacobin Club of "too often showing his vices and not his virtue".

In early December, Robespierre accused Danton in the Jacobin Club of "too often showing his vices and not his virtue".

Maximilien Robespierre, Master of the Terror

" Maximilien Robespierre, Master of the Terror. Accessed 23 October 2018. . * * * * * * * * *

by Adam Thorpe in ''

Reviewed

by Ruth Scurr in ''The Guardian'', 17 August 2012 *

"The Terror"

from '' In Our Time'' (BBC Radio 4) {{DEFAULTSORT:Reign Of Terror 1793 events of the French Revolution 1794 events of the French Revolution Anti-Catholicism in France Persecution of Christians Police brutality in France Political and cultural purges Political repression in France Terrorism committed by France People killed in the French Revolution Revolution terminology Politicides Terrorist incidents in France Massacres committed by the French First Republic Massacres of the French Revolution Left-wing terrorism Revolutionary terror

national guard

National guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

...

, they persuaded the Convention to arrest 29 Girondist leaders. In reaction to the imprisonment of the Girondin deputies, some 13 departments started the Federalist revolts

The Federalist revolts were uprisings that broke out in various parts of France in the summer of 1793, during the French Revolution. They were prompted by resentments in France's provincial cities about increasing centralisation of power in Pa ...

against Convention, which were ultimately crushed.

On 24 June the Convention adopted the first republican constitution of France, the French Constitution of 1793

The Constitution of 1793 (), also known as the Constitution of the Year I or the Montagnard Constitution, was the second constitution ratified for use during the French Revolution under the First Republic. Designed by the Montagnards, princip ...

. It was ratified by public referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

, but never put into force. On 13 July the assassination of Jean-Paul Marat

Jean-Paul Marat (, , ; born Jean-Paul Mara; 24 May 1743 – 13 July 1793) was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist. A journalist and politician during the French Revolution, he was a vigorous defender of the ''sans-culottes ...

—a Jacobin leader and journalist—resulted in a further increase in Jacobin political influence. Georges Danton

Georges Jacques Danton (; ; 26 October 1759 – 5 April 1794) was a leading figure of the French Revolution. A modest and unknown lawyer on the eve of the Revolution, Danton became a famous orator of the Cordeliers Club and was raised to gove ...

, the leader of the August 1792 uprising against the king, was removed from the Committee of Public Safety on 10 July. On 27 July Robespierre became part of the Committee of Public Safety.

On 23 August the National Convention decreed the ''levée en masse

''Levée en masse'' ( or, in English, ''mass levy'') is a French term used for a policy of mass national conscription, often in the face of invasion.

The concept originated during the French Revolutionary Wars, particularly for the period fo ...

'':

On 5 September on the proposal of Barère, the Convention was supposed to have declared by vote that "terror is the order of the day". On that day's session, the Convention, upon a proposal by Pierre Gaspard Chaumette and supported by Billaud and Danton, decided to form a revolutionary army of 6,000 men in Paris.Richard T. Bienvenu (1968) ''The Ninth of Thermidor'', p. 22; R.R. Palmer (1970) ''The Twelve who Ruled'', pp. 47–51 Barère, representing the Committee of Public Safety, introduced a decree that was promptly passed, establishing a paid armed force of 6,000 men and 1,200 gunners "tasked with crushing counter-revolutionaries, enforcing revolutionary laws and public safety measures decreed by the National Convention, and safeguarding provisions." This allowed the government to form "revolutionary armies" designed to force French citizens into compliance with Maximilian rule. These armies were also used to enforce "the law of the General Maximum

The Law of the General Maximum () was instituted during the French Revolution on 29 September 1793, setting price limits and punishing price gouging to attempt to ensure the continued supply of food to the French capital. It was enacted as an ...

", which controlled the distribution and pricing of food. Addressing the Convention, Robespierre claimed that the "weight and willpower" of the people loyal to the republic would be used to oppress those who would turn "political gatherings into gladiatorial arenas". The policy change unleashed a newfound military power in France, which was used to defend against the future coalitions formed by rival nations. The event also solidified Robespierre's rise to power as president of the Committee of Public Safety earlier in July.

On 8 September banks and exchange offices were shuttered to curb the circulation of counterfeit ''assignats'' and the outflow of capital, with investments in foreign countries punishable by death. The following day, the extremists Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois

Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois (; 19 June 1749 – 8 June 1796) was a French actor, dramatist, essayist, and revolutionary. He was a member of the Committee of Public Safety during the Reign of Terror and, while he saved Madame Tussaud from the ...

and Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne

Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne (; 23 April 1756 – 3 June 1819), also known as Jean Nicolas or by his nicknames, the Righteous Patriot or the Tiger, was a French lawyer and a major figure in the French Revolution. A close associate of Georges ...

were elected in the Committee of Public Safety. On 9 September the convention established paramilitary forces, the "revolutionary armies", to force farmers to surrender grain demanded by the government. On 17 September the Law of Suspects

:''Note: This decree should not be confused with the Law of General Security (), also known as the "Law of Suspects," adopted by Napoleon III in 1858 that allowed punishment for any prison action, and permitted the arrest and deportation, without ...

was passed, which authorized the imprisonment of vaguely defined "suspects". This created a mass overflow in the prison systems. On 29 September the Convention extended price fixing

Price fixing is an anticompetitive agreement between participants on the same side in a market to buy or sell a product, service, or commodity only at a fixed price, or maintain the market conditions such that the price is maintained at a given ...

from grain and bread to other essential goods and also fixed wages.

On 10 October the Convention decreed "the provisional government shall be revolutionary until peace." On 16 October Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

was executed. The trial of the Girondins started on the same day; they were executed on 31 October in just over half an hour by Charles-Henri Sanson. Joseph Fouché

Joseph Fouché, 1st Duc d'Otrante, 1st Comte Fouché (; 21 May 1759 – 26 December 1820) was a French statesman, revolutionary, and Minister of Police under First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte, who later became a subordinate of Emperor Napoleon. H ...

and Collot d'Herbois suppressed the revolt of Lyon against the National Convention

The revolt of Lyon against the National Convention was a counter-revolutionary movement in the city of Lyon during the time of the French Revolution. It was a revolt of moderates against the more radical National Convention, the third government ...

, while Jean-Baptiste Carrier

Jean-Baptiste Carrier (; 16 March 1756 – 16 December 1794) was a French Revolutionary and politician most notable for his actions in the War in the Vendée during the Reign of Terror. While under orders to suppress a Royalist counter-revoluti ...

ordered the drownings at Nantes. Jean-Lambert Tallien

Jean-Lambert Tallien (, 23 January 1767 – 16 November 1820) was a French politician of the revolutionary period. Though initially an active agent of the Reign of Terror, he eventually clashed with its leader, Maximilien Robespierre, and is bes ...

ensured the operation of the guillotine in Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

, while Barras and Fréron addressed issues in Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

and Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

. Joseph Le Bon

Joseph Le Bon (29 September 1765 – 10 October 1795) was a French politician.

Biography

He was born at Arras. He became a priest in the order of the Oratory, and professor of rhetoric at Beaune. He adopted revolutionary ideas, and became a cu ...

was sent to the Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

* Somme, Queensland, Australia

* Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), ...

and Pas-de-Calais

The Pas-de-Calais (, ' strait of Calais'; ; ) is a department in northern France named after the French designation of the Strait of Dover, which it borders. It has the most communes of all the departments of France, with 890, and is the ...

regions.Richard T. Bienvenu (1968) ''The Ninth of Thermidor'', p. 23

On 8 November, the director of the ''assignats'' manufacture, and Manon Roland were executed. On 13 November the Convention shut down the Paris Bourse

Euronext Paris, formerly known as the Paris Bourse (), is a regulated securities trading venue in France. It is Europe's second largest stock exchange by market capitalization, behind the London Stock Exchange, as of December 2023. As of 2022, th ...

and banned all commerce in precious metals, under penalties. Anti-clerical sentiments increased and a campaign of dechristianization occurred at the end of 1793. Eventually, Robespierre denounced the "de-Christianisers" as foreign enemies.

In early December, Robespierre accused Danton in the Jacobin Club of "too often showing his vices and not his virtue".

In early December, Robespierre accused Danton in the Jacobin Club of "too often showing his vices and not his virtue". Camille Desmoulins

Lucie-Simplice-Camille-Benoît Desmoulins (; 2 March 17605 April 1794) was a French journalist, politician and a prominent figure of the French Revolution. He is best known for playing an instrumental role in the events that led to the Stormin ...

defended Danton and warned Robespierre not to exaggerate the revolution. On 5 December the National Convention passed the Law of Frimaire, which gave the central government more control over the actions of the representatives on mission

Representative may refer to:

Politics

*Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

*House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

*Legislator, someon ...

. The Commune of Paris and the revolutionary committees in the sections had to obey the law, the two Committees, and the Convention. Desmoulins argued that the Revolution should return to its original ideas en vogue around 10 August 1792. A Committee of Grace had to be established. On 8 December, Madame du Barry

Jeanne Bécu, comtesse du Barry (; 28 August 1744 – 8 December 1793) was the last ''maîtresse-en-titre'' of King Louis XV of France. She was executed by guillotine during the French Revolution on accusations of treason—particularly being ...

was guillotined. On receiving notice that he was to appear on the next day before the Revolutionary Tribunal, Étienne Clavière committed suicide. American Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

lost his seat in the Convention, was arrested, and locked up for his association with the Girondins, as well as being a foreign national. By the end of 1793, two major factions had emerged, both threatening the revolutionary government: the Hébertists, who called for an intensification of the Terror and threatened insurrection, and the Dantonists, led by Danton, who demanded moderation and clemency. The Committee of Public Safety took actions against both.

On 8 February 1794 Carrier was recalled from Nantes after a member of the Committee of Public Safety wrote to Robespierre with information about the atrocities being carried out, although Carrier was not put on trial. On 26 February and 3 March Louis Antoine de Saint-Just

Louis Antoine Léon de Saint-Just (; 25 August 176710 Thermidor, Year II 8 July 1794, sometimes nicknamed the Archangel of Terror, was a French revolutionary, political philosopher, member and president of the National Convention, French ...

proposed decrees to confiscate the property of exiles and opponents of the revolution, known as the Ventôse Decrees.

In March the major Hébertists were tried before the Revolutionary Tribunal and executed on 24 March. On 30 March the two committees decided to arrest Danton and Desmoulins after Saint-Just became uncharacteristically angry. The Dantonists were tried on 3 to 5 April and executed on 5 April. In mid-April it was decreed to centralise the investigation of court records and to bring all the political suspects in France to the Revolutionary Tribunal to Paris. Saint-Just and Philippe-François-Joseph Le Bas journeyed the Rhine Army to oversee the generals and punish officers for perceived treasonous timidity or lack of initiative. The two committees received the power to interrogate them immediately. A special police bureau inside the Comité de salut public was created, whose task was to monitor public servants, competing with both the Committee of General Security and the Committee of Public Safety. Foreigners were no longer allowed to travel through France or visit a Jacobin club; Dutch patriots who had fled to France before 1790 were excluded.

On 22 April Guillaume-Chrétien de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, Isaac René Guy le Chapelier

Isaac René Guy Le Chapelier (12 June 1754 – 22 April 1794) was a French jurist and politician of the Revolutionary period.

Biography

Le Chapelier was born in Rennes in Brittany, where his father was ''bâtonnier'' of the corporation of lawy ...

, Jacques Guillaume Thouret were taken to be executed.A. Jourdan (2018) Le tribunal révolutionnaire. Saint-Just and Le Bas left Paris at the end of the month for the army in the north. On 21 May the revolutionary government decided that the Terror would be centralised, with almost all

the tribunals

A tribunal, generally, is any person or institution with authority to judge, adjudicate on, or determine claims or disputes—whether or not it is called a tribunal in its title. For example, an advocate who appears before a court with a singl ...

in the provinces closed and all the trials held in Paris. On 20 May Robespierre signed Theresa Cabarrus's arrest warrant, and on 23 May, following an attempted assassination on d'Herbois. Cécile Renault was arrested near Robespierre's residence with two penknives and a change of underwear claiming the fresh linen was for her execution. She was executed on 17 June.

On 10 June the National Convention passed a law proposed by Georges Couthon, known as the Law of 22 Prairial

The Law of 22 Prairial, also known as the ''loi de la Grande Terreur'', the law of the Great Terror, was enacted on 10 June 1794 (22 Prairial of the Year II under the French Revolutionary Calendar). It was proposed by Georges Auguste Couthon bu ...

, which simplified the judicial process and greatly accelerated the work of the Revolutionary Tribunal. With the enactment of the law, the number of executions greatly increased, and the period became known as "The Great Terror" (). Between 10 June and 27 July, another 1,366 were executed, causing fear among d'Herbois, Fouché and Tallien due to their past actions. Like Brissot, Madame Roland, Pétion, Hébert and Danton, Tallien was accused of participating in conspicuous dinners. On 18 June Pétion de Villeneuve and François Buzot committed suicide, and Joachim Vilate was arrested on 21 June.

On 26 June the French army won the Battle of Fleurus, which marked a turning point in France's military campaign and undermined the necessity of wartime measures and the legitimacy of the revolutionary government. In early July about 60 individuals were arrested as "enemies of the people

The terms enemy of the people and enemy of the nation are designations for the political opponents and the social-class opponents of the power group within a larger social unit, who, thus identified, can be subjected to political repression. ...

" and accused of conspiring against liberty. The total of death sentences in Paris in July was more than double the number in June, with two new mass graves dug at Picpus Cemetery

Picpus Cemetery (, ) is the largest private cemetery in Paris, France, and is located in the 12th arrondissement of Paris, 12th arrondissement. It was created from land seized from the Coignard, convent of the Chanoinesses de St-Augustin, during ...

by mid-July. There was widespread agreement among deputies that their parliamentary immunity

Parliamentary immunity, also known as legislative immunity, is a system in which politicians or other political leaders are granted full immunity from legal prosecution, both civil prosecution and criminal prosecution, in the course of the exe ...

, in place since 1 April 1793, had become perilous. On 14 July Robespierre had Fouché expelled. To evade arrest about 50 deputies avoided staying at home.

Thermidorian Reaction

The fall of Robespierre was brought about by a combination of those who wanted more power for the Committee of Public Safety (and a more radical policy than he was willing to allow) and the moderates who completely opposed the revolutionary government. They had, between them, made the Law of 22 Prairial one of the charges against him, so that after his fall, to advocate terror would be seen as adopting the policy of a convicted enemy of the republic, putting the advocate's own head at risk. Between his arrest and his execution, Robespierre may have tried to commit suicide by shooting himself, although the bullet wound he sustained, whatever its origin, only shattered his jaw. Alternatively, he may have been shot by the gendarme Charles-André Merda. A change in orientation might explain how Robespierre, sitting in a chair, got wounded from the upper right in the lower left jaw.) According to Bourdon, Méda then hit Couthon's adjutant in his leg. Couthon was found lying at the bottom of a staircase in a corner, having fallen from the back of his adjutant. Saint-Just gave himself up without a word. According to Méda, Hanriot tried to escape by a concealed staircase to the third floor and his apartment. The great confusion that arose during the storming of the municipal Hall of Paris, where Robespierre and his friends had found refuge, makes it impossible to be sure of the wound's origin. A group of 15 to 20 conspirators were locked up in a room inside the Hôtel de Ville. In any case, Robespierre was guillotined the next day, together with Saint-Just, Couthon and his brotherAugustin Robespierre

Augustin Bon Joseph de Robespierre (21 January 1763 – 28 July 1794), known as Robespierre the Younger, was a French lawyer, politician and the younger brother of French Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre. His political views were sim ...

. The day following his demise, approximately half of the Paris Commune (70 members) met their fate at the guillotine.

According to Barère, who just like Robespierre never went on mission: "We did not deceive ourselves that Saint-Just, cut out as a more dictatorial boss, would have finished by overthrowing obespierreto put himself in his place; we also knew that we who stood in the way of his projects, he would have us guillotined; we overthrew him."

See also

* Bals des victimes * Infernal columns *Revolutionary terror

Revolutionary terror, also referred to as revolutionary terrorism or reign of terror, refers to the institutionalized application of force to counter-revolutionaries, particularly during the French Revolution from the years 1793 to 1795 (see t ...

* State terrorism

State terrorism is terrorism conducted by a state against its own citizens or another state's citizens.

It contrasts with '' state-sponsored terrorism'', in which a violent non-state actor conducts an act of terror under sponsorship of a state. ...

* Terrorism in France

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Terrorism in France

, partof = the Opération Sentinelle, War on terror, Islamic terrorism in Europe

, image = Lieu de l'attentat du 14 juillet 2016 à Nice cropped.jpg

...

* Tricoteuse

''Tricoteuse'' () is French for a knitting woman. The term is most often used in its historical sense as a nickname for the women in the French Revolution who sat in the gallery supporting the left-wing politicians in the National Convention, a ...

Notes

References

Citations

Works cited

* Bloy, Marjorie. "The First Coalition 1793–1797." A Web of English History. Accessed 21 October 2018. http://www.historyhome.co.uk/c-eight/france/coalit1.htm . * * Leopold, II, and Frederick William. "The Declaration of Pillnitz (1791)." French Revolution. 27 February 2018. Accessed 26 October 2018. https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/declaration-of-pillnitz-1791/ . * * McLetchie, Scott. "Maximilien Robespierre, Master of the Terror." Maximilien Robespierre, Master of the Terror. Accessed 23 October 2018. http://people.loyno.edu/~history/journal/1983-4/mcletchie.htm#22 . * Montesquieu. "Modern History Sourcebook: Montesquieu: The Spirit of the Laws, 1748." Internet History Sourcebooks. Accessed 23 October 2018. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/montesquieu-spirit.asp . * * "Robespierre, "On Political Morality"," Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, accessed 19 October 2018, http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/413 . * * Voltaire. "Voltaire, Selections from the Philosophical Dictionary." Omeka RSS. Accessed 23 October 2018. http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/273/ .Further reading

Primary sources

*Secondary sources

* * * * Baker, Keith M. François Furet, and Colin Lucas, eds. (1987) ''The French Revolution and the Creation of Modern Political Culture, vol. 4, The Terror'' (London: Pergamon Press, 1987) * * Biard, Michel and Linton, Marisa, ''Terror: The French Revolution and its Demons'' (Polity Press, 2021). * * * * Gough, Hugh. ''The Terror in the French Revolution'' (London: Macmillan, 1998) * * * * * McLetchie, Scott.Maximilien Robespierre, Master of the Terror

" Maximilien Robespierre, Master of the Terror. Accessed 23 October 2018. . * * * * * * * * *

by Adam Thorpe in ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', 23 December 2006.

* Sutherland, D.M.G. (2003) ''The French Revolution and Empire: The Quest for a Civic Order'' pp 174–253

*

*

*Reviewed

by Ruth Scurr in ''The Guardian'', 17 August 2012 *

Historiography

* * A Marxist political portrait of Robespierre, examining his changing image among historians and the different aspects of Robespierre as an 'ideologue', as a political democrat, as a social democrat, as a practitioner of revolution, as a politician and as a popular leader/leader of revolution, it also touches on his legacy for the future revolutionary leadersLenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

and Mao.

External links

"The Terror"

from '' In Our Time'' (BBC Radio 4) {{DEFAULTSORT:Reign Of Terror 1793 events of the French Revolution 1794 events of the French Revolution Anti-Catholicism in France Persecution of Christians Police brutality in France Political and cultural purges Political repression in France Terrorism committed by France People killed in the French Revolution Revolution terminology Politicides Terrorist incidents in France Massacres committed by the French First Republic Massacres of the French Revolution Left-wing terrorism Revolutionary terror