Ramsses II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ramesses II (sometimes written Ramses or Rameses) (; , , ; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was an Egyptian pharaoh. He was the third ruler of the

After Ramesses I died, his son,

After Ramesses I died, his son,

Announcement of the Passing of Ramesses II

JEOL 46 (2016), p. 125. As the Egyptologist Robert J. Demarée notes in a 2016 paper: : The feast called ẖnw – ‘Sailing’ – was clearly observed in Thebes or at

The immediate antecedents to the Battle of Kadesh were the early campaigns of Ramesses II into

The immediate antecedents to the Battle of Kadesh were the early campaigns of Ramesses II into

.100 Battles, ''Decisive Battles that Shaped the World'', Dougherty, Martin, J., Parragon, pp. 10–11. While Ramesses claimed a great victory, and this was technically true in terms of the actual battle, it is generally considered that the Hittites were the ultimate victors as far as the overall campaign was concerned, since the Egyptians retreated after the battle, and Hittite forces invaded and briefly occupied the Egyptian possessions in the region of

Ramesses extended his military successes in his eighth and ninth years. He crossed the Dog River (

Ramesses extended his military successes in his eighth and ninth years. He crossed the Dog River (

In Year 21 of Ramesses's reign, he concluded a peace treaty with the Hittites known to modern scholars as the ''Treaty of Kadesh''. Though this treaty settled the disputes over Canaan, its immediate impetus seems to have been a diplomatic crisis that occurred following

In Year 21 of Ramesses's reign, he concluded a peace treaty with the Hittites known to modern scholars as the ''Treaty of Kadesh''. Though this treaty settled the disputes over Canaan, its immediate impetus seems to have been a diplomatic crisis that occurred following

Ramesses II also campaigned south of the first cataract of the Nile into

Ramesses II also campaigned south of the first cataract of the Nile into

As of Year 28 of his reign, Ramesses II favored the god

As of Year 28 of his reign, Ramesses II favored the god

The temple complex built by Ramesses II between Qurna and the desert has been known as the

The temple complex built by Ramesses II between Qurna and the desert has been known as the

Nineteenth Dynasty

The Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XIX), also known as the Ramessid dynasty, is classified as the second Dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1292 BC to 1189 BC. The 19th Dynasty and the 20th Dynasty fu ...

. Along with Thutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, (1479–1425 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. He is regarded as one of the greatest warriors, military commanders, and milita ...

of the Eighteenth Dynasty

The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XVIII, alternatively 18th Dynasty or Dynasty 18) is classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty ...

, he is often regarded as the greatest, most celebrated, and most powerful pharaoh of the New Kingdom

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

** "New" (Paul McCartney song), 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, 1995

* "New" (Daya song), 2017

* "New" (No Doubt song), 1 ...

, which itself was the most powerful period of ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

. He is also widely considered one of ancient Egypt's most successful warrior pharaohs, conducting no fewer than 15 military campaigns, all resulting in victories, excluding the Battle of Kadesh

The Battle of Kadesh took place in the 13th century BC between the New Kingdom of Egypt, Egyptian Empire led by pharaoh Ramesses II and the Hittites, Hittite Empire led by king Muwatalli II. Their armies engaged each other at the Orontes River, ...

, generally considered a stalemate.

In ancient Greek sources, he is called Ozymandias, derived from the first part of his Egyptian-language regnal name: . Ramesses was also referred to as the "Great Ancestor" by successor pharaohs and the Egyptian people.

For the early part of his reign, he focused on building cities, temples, and monuments. After establishing the city of Pi-Ramesses

Pi-Ramesses (; Ancient Egyptian: , meaning "House of Ramesses") was the new capital built by the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Nineteenth Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) at Qantir, near the old site of Avaris. The city had served as a ...

in the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

, he designated it as Egypt's new capital and used it as the main staging point for his campaigns in Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

. Ramesses led several military expeditions into the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, where he reasserted Egyptian control over Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

and Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

; he also led a number of expeditions into Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

, all commemorated in inscriptions at Beit el-Wali and Gerf Hussein. He celebrated an unprecedented thirteen or fourteen Sed festival

The Sed festival (''ḥb-sd'', Egyptian language#Egyptological pronunciation, conventional pronunciation ; also known as Heb Sed or Feast of the Tail) was an ancient Egyptian ceremony that celebrated the continued rule of a pharaoh. The name is ...

s—more than any other pharaoh.

Estimates of his age at death vary, although 90 or 91 is considered to be the most likely figure. Upon his death, he was buried in a tomb (KV7

Tomb KV7 was the tomb of Ramesses II ("Ramesses the Great"), an ancient Egyptian pharaoh during the Nineteenth Dynasty.

It is located in the Valley of the Kings opposite the tomb of his sons, KV5, and near to the tomb of his son and successor M ...

) in the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is an area in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the Eighteenth Dynasty to the Twentieth Dynasty, rock-cut tombs were excavated for pharaohs and power ...

; his body was later moved to the Royal Cache

The Royal Cache, technically known as TT320 (previously referred to as DB320), is an Ancient Egyptian Hypogeum, tomb located next to Deir el-Bahari, in the Theban Necropolis, opposite the modern city of Luxor.

It contains an extraordinary collect ...

, where it was discovered by archaeologists in 1881. Ramesses' mummy

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and Organ (biology), organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to Chemical substance, chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the ...

is now on display at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization

The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC) is a large museum located in Old Cairo, a district of Cairo, Egypt.

Partially opened in 2017, the museum was officially inaugurated on 3 April 2021, with the moving of 22 mummies, including 1 ...

, located in the city of Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

.

Ramesses II was one of the few pharoahs who was worshipped as a deity during his lifetime.

Early life

Ramesses II was not born a prince. His grandfatherRamesses I

Menpehtyre Ramesses I (or Ramses) was the founding pharaoh of ancient Egypt's Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, 19th Dynasty. The dates for his short reign are not completely known but the timeline of late 1290s BC, 1292–1290 BC is frequently cited ...

was a vizier (''tjaty'') and military officer during the reign of pharaoh Horemheb

Horemheb, also spelled Horemhab, Haremheb or Haremhab (, meaning "Horus is in Jubilation"), was the last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, 18th Dynasty of Egypt (1550–1292 BC). He ruled for at least 14 years between 1319 ...

, who appointed Ramesses I as his successor; at that time, Ramesses II was about eleven years old.

After Ramesses I died, his son,

After Ramesses I died, his son, Seti I

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek language, Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom of Egypt, New Kingdom period, ruling or 1290 BC to 1279 BC. He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and th ...

became king, and designated his son Ramesses II as prince regent at about the age of fourteen.

Reign length

Ramesses date of accession to the throne is recorded as III Shemu, day 27, which mostEgyptologists

This is a partial list of Egyptologists. An Egyptologist is any archaeologist, historian, linguist, or art historian who specializes in Egyptology, the scientific study of Ancient Egypt and its antiquities. Demotists are Egyptologists who speciali ...

believe to be 31 May 1279 BC.

The Jewish historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

, in his book ''Contra Apionem

''Against Apion'' ( ''Peri Archaiotētos Ioudaiōn Logos''; Latin ''Contra Apionem'' or ''In Apionem'') is a work written by Flavius Josephus (c. 37 CE – c. 100 CE ) as a defense of Judaism against criticism by the Egyptian author Apion. J ...

'' which included material from Manetho

Manetho (; ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος, ''fl''. 290–260 BCE) was an Egyptian priest of the Ptolemaic Kingdom who lived in the early third century BCE, at the very beginning of the Hellenistic period. Little is certain about his ...

's ''Aegyptiaca'', assigned Ramesses II ("Armesses Miamun") a reign of 66 years, 2 months. This is essentially confirmed by the calendar of Papyrus Gurob fragment L, where Year 67, I Akhet day 18 of Ramesses II is immediately followed by Year 1, II Akhet day 19 of Merneptah

Merneptah () or Merenptah (reigned July or August 1213–2 May 1203 BCE) was the fourth pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Nineteenth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. According to contemporary historical records, he ruled Egypt for almost ten y ...

(Ramesses II's son), meaning Ramesses II died about 2 months into his 67th Regnal year.

In 1994, A. J. Peden proposed that Ramesses II died between II Akhet day 3 and II Akhet day 13 on the basis of Theban graffito 854+855, equated to Merneptah's Year 1 II Akhet day 2. The workman's village of Deir el-Medina

Deir el-Medina (), or Dayr al-Madīnah, is an ancient Egyptian workmen's village which was home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom of Egypt (ca. 1550–1080 BC). ...

preserves a fragment of a mid-20th dynasty necropolis journal (P. Turin prov. nr. 8538 recto I, 5; unpublished) which records that the date II Akhet day 6 was a Free feast day for the "Sailing of UsimaRe-Setepenre." (for Ramesses II).R. J. DemaréeAnnouncement of the Passing of Ramesses II

JEOL 46 (2016), p. 125. As the Egyptologist Robert J. Demarée notes in a 2016 paper: : The feast called ẖnw – ‘Sailing’ – was clearly observed in Thebes or at

Deir el-Medina

Deir el-Medina (), or Dayr al-Madīnah, is an ancient Egyptian workmen's village which was home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom of Egypt (ca. 1550–1080 BC). ...

during the Ramesside Period in remembrance of the passing of deified royals. The ‘Sailing’ of Ahmose-Nefertari

Ahmose-Nefertari (Ancient Egyptian: '' Jꜥḥ ms Nfr trj'') was the first Great Royal Wife of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. She was a daughter of Seqenenre Tao and Ahhotep I, and royal sister and wife to Ahmose I. Her son Amenhotep I beca ...

was celebrated on II Shemu 15; the ‘Sailing’ of Seti I on III Shemu 24; and the ‘Sailing’ of Ramesses II on II Akhet 6.

The date of Ramesses II's recorded death on II Akhet day 6 falls perfectly within A. J. Peden's estimated timeline for the king's death in the interval between II Akhet day 3 and II Akhet day 13. This means that Ramesses II died on Year 67, II Akhet day 6 of his reign after ruling Egypt for 66 years 2 months and 9 days.

Military campaigns

Early in his life, Ramesses II embarked on numerous campaigns to restore possession of previously held territories lost to theNubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

ns and Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian peoples, Anatolian Proto-Indo-Europeans, Indo-European people who formed one of the first major civilizations of the Bronze Age in West Asia. Possibly originating from beyond the Black Sea, they settled in mo ...

and to secure Egypt's borders. He was also responsible for suppressing some Nubian revolts and carrying out a campaign in Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

. Though the Battle of Kadesh

The Battle of Kadesh took place in the 13th century BC between the New Kingdom of Egypt, Egyptian Empire led by pharaoh Ramesses II and the Hittites, Hittite Empire led by king Muwatalli II. Their armies engaged each other at the Orontes River, ...

often dominates the scholarly view of Ramesses II's military prowess and power, he nevertheless enjoyed more than a few outright victories over Egypt's enemies. During his reign, the Egyptian army is estimated to have totaled some 100,000 men: a formidable force that he used to strengthen Egyptian influence.

Battle against Sherden pirates

In his second year, Ramesses II decisively defeated theSherden

The Sherden (Egyptian: ''šrdn'', ''šꜣrdꜣnꜣ'' or ''šꜣrdynꜣ''; Ugaritic: ''šrdnn(m)'' and ''trtn(m)''; possibly Akkadian: ''šêrtânnu''; also glossed "Shardana" or "Sherdanu") are one of the several ethnic groups the Sea Peoples wer ...

sea pirates who were wreaking havoc along Egypt's Mediterranean coast by attacking cargo-laden vessels travelling the sea routes to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. The Sherden people probably came from the coast of Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

, from southwest Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

or perhaps, also from the island of Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

. Ramesses posted troops and ships at strategic points along the coast and patiently allowed the pirates to attack their perceived prey before skillfully catching them by surprise in a sea battle and capturing them all in a single action. A stele

A stele ( ) or stela ( )The plural in English is sometimes stelai ( ) based on direct transliteration of the Greek, sometimes stelae or stelæ ( ) based on the inflection of Greek nouns in Latin, and sometimes anglicized to steles ( ) or stela ...

from Tanis

Tanis ( ; ; ) or San al-Hagar (; ; ; or or ; ) is the Greek name for ancient Egyptian ''ḏꜥn.t'', an important archaeological site in the northeastern Nile Delta of ancient Egypt, Egypt, and the location of a city of the same name. Tanis ...

speaks of their having come "in their war-ships from the midst of the sea, and none were able to stand before them". There probably was a naval battle somewhere near the mouth of the Nile, as shortly afterward, many Sherden are seen among the pharaoh's body-guard where they are conspicuous by their horned helmets having a ball projecting from the middle, their round shields, and the great Naue II swords with which they are depicted in inscriptions of the Battle of Kadesh. In that sea battle, together with the Sherden, the pharaoh also defeated the Lukka

The Lukka lands (sometimes Luqqa lands), were an ancient region of Anatolia. They are known from Hittite and Egyptian texts, which viewed them as hostile. It is commonly accepted that the Bronze Age toponym Lukka is cognate with the Lycia of cl ...

(L'kkw, possibly the people later known as the Lycians

Lycians () is the name of various peoples who lived, at different times, in Lycia, a geopolitical area in Anatolia (also known as Asia Minor).

History

The earliest known inhabitants of the area were the ''Solymoi'' (or ''Solymi''), also kn ...

), and the Šqrsšw (Shekelesh

The Shekelesh (Egyptian language: ''šꜣkrwšꜣꜣ'' or ''šꜣꜣkrwšꜣꜣ'') were one of the several ethnic groups the Sea Peoples were said to be composed of, appearing in fragmentary historical and iconographic records in ancient Egyptian f ...

) peoples.

Syrian campaigns

First Syrian campaign

The immediate antecedents to the Battle of Kadesh were the early campaigns of Ramesses II into

The immediate antecedents to the Battle of Kadesh were the early campaigns of Ramesses II into Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

. His first campaign seems to have taken place in the fourth year of his reign and was commemorated by the erection of what became the first of the Commemorative stelae of Nahr el-Kalb

The commemorative stelae of Nahr el-Kalb are a group of over 20 inscriptions and rock reliefs carved into the limestone rocks around the estuary of the Nahr al-Kalb (Dog River) in Lebanon, just north of Beirut.

The inscriptions include three Egyp ...

near what is now Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

. The inscription is almost totally illegible due to weathering.

In the fourth year of his reign, he captured the Hittite vassal state of the Amurru during his campaign in Syria.

Second Syrian campaign

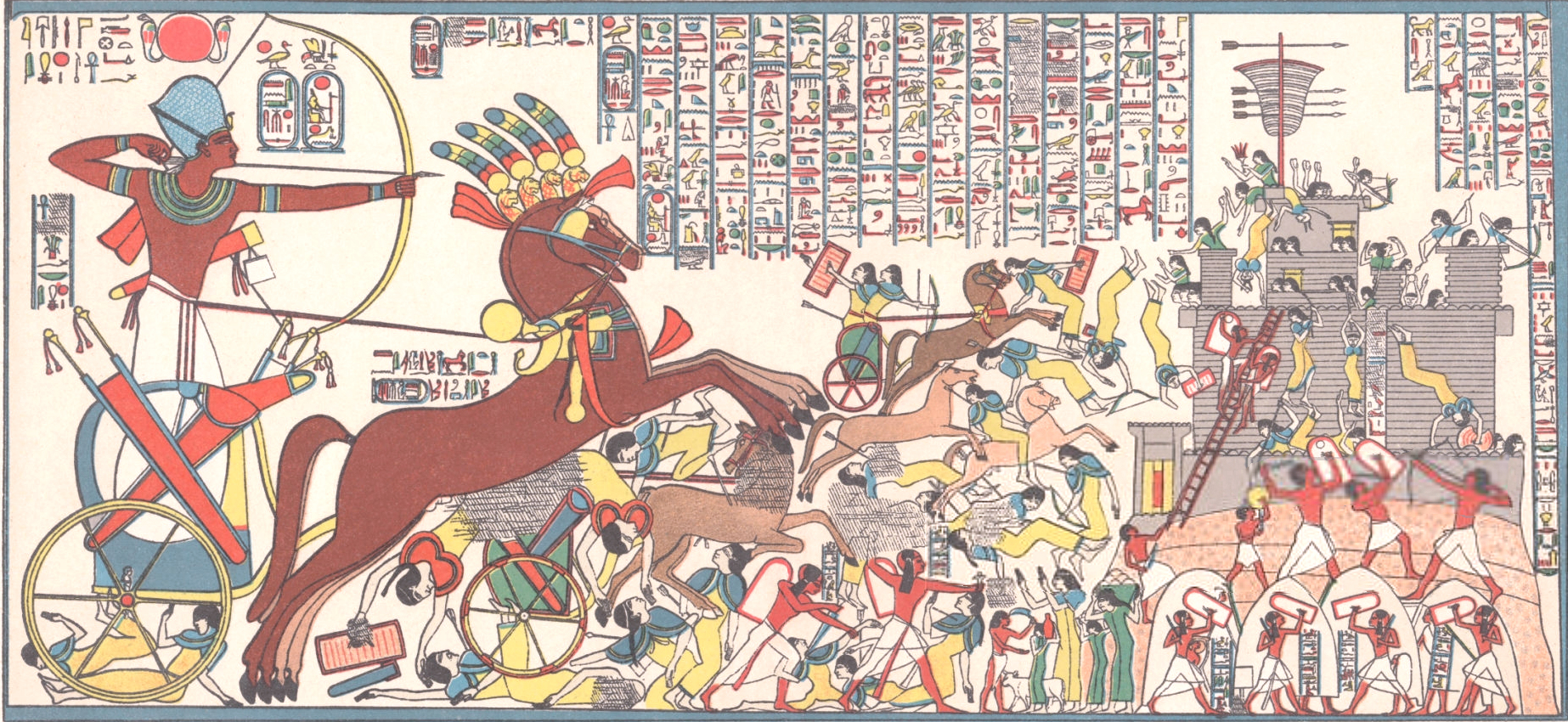

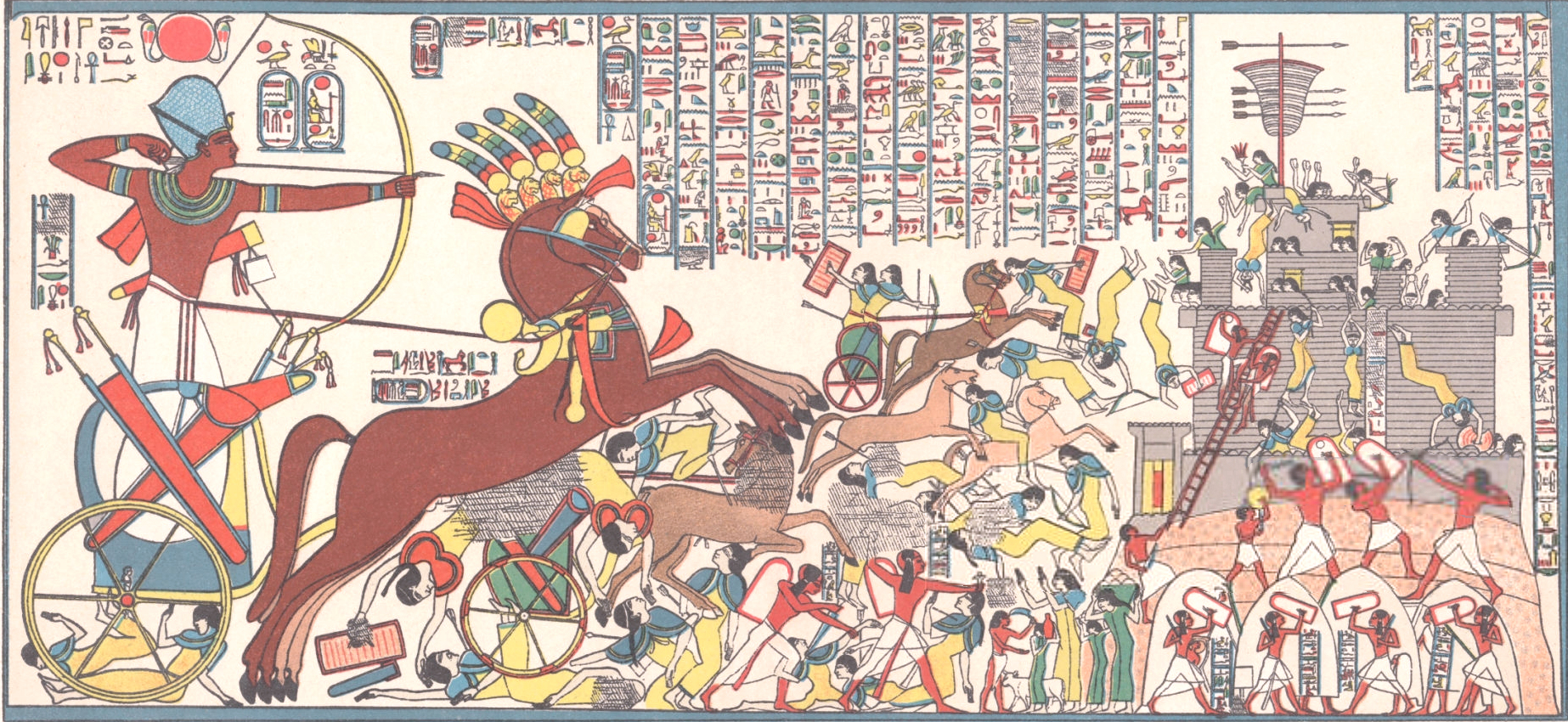

The Battle of Kadesh in his fifth regnal year was the climactic engagement in a campaign that Ramesses fought in Syria, against the resurgent Hittite forces ofMuwatalli II

Muwatalli II (also Muwatallis, or Muwatallish; meaning "mighty") was a king of the New Kingdom of the Hittite empire c. 1295–1282 ( middle chronology) and 1295–1272 BC in the short chronology.

Biography

He was the eldest son of Mursili II ...

. The pharaoh wanted a victory at Kadesh

Qadesh, Qedesh, Qetesh, Kadesh, Kedesh, Kadeš and Qades come from the common Semitic root "Q-D-Š", which means "sacred."

Kadesh and variations may refer to:

Ancient/biblical places

* Kadesh (Syria) or Qadesh, an ancient city of the Levant, on ...

both to expand Egypt's frontiers into Syria, and to emulate his father Seti I's triumphal entry into the city just a decade or so earlier.

He also constructed his new capital, Pi-Ramesses

Pi-Ramesses (; Ancient Egyptian: , meaning "House of Ramesses") was the new capital built by the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Nineteenth Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) at Qantir, near the old site of Avaris. The city had served as a ...

. There he built factories to manufacture weapons, chariots, and shields, supposedly producing some 1,000 weapons in a week, about 250 chariots in two weeks, and 1,000 shields in a week and a half. After these preparations, Ramesses moved to attack territory in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, which belonged to a more substantial enemy than any he had ever faced in war: the Hittite Empire

The Hittites () were an Anatolian peoples, Anatolian Proto-Indo-Europeans, Indo-European people who formed one of the first major civilizations of the Bronze Age in West Asia. Possibly originating from beyond the Black Sea, they settled in mo ...

.

After advancing through Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

for exactly a month, according to the Egyptian sources, Ramesses arrived at Kadesh on 1 May 1274 BC. Here, Ramesses' troops were caught in a Hittite ambush and were initially outnumbered by the enemy, whose chariotry smashed through the second division of Ramesses' forces and attacked his camp. Receiving reinforcements from other Egyptian divisions arriving on the battlefield, the Egyptians counterattacked and routed the Hittites, whose survivors abandoned their chariots and swam the Orontes River

The Orontes (; from Ancient Greek , ) or Nahr al-ʿĀṣī, or simply Asi (, ; ) is a long river in Western Asia that begins in Lebanon, flowing northwards through Syria before entering the Mediterranean Sea near Samandağ in Hatay Province, Turk ...

to reach the safe city walls. Although left in possession of the battlefield, Ramesses, logistically unable to sustain a long siege, returned to Egypt.The Battle of Kadesh in the context of Hittite history.100 Battles, ''Decisive Battles that Shaped the World'', Dougherty, Martin, J., Parragon, pp. 10–11. While Ramesses claimed a great victory, and this was technically true in terms of the actual battle, it is generally considered that the Hittites were the ultimate victors as far as the overall campaign was concerned, since the Egyptians retreated after the battle, and Hittite forces invaded and briefly occupied the Egyptian possessions in the region of

Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

.

Third Syrian campaign

Egypt's sphere of influence was now restricted to Canaan whileSyria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

fell into Hittite hands. Canaanite princes, seemingly encouraged by the Egyptian incapacity to impose their will and goaded on by the Hittites, began revolts against Egypt. Ramesses II was not willing to let this stand, and prepared to contest the Hittite advance with new military campaigns. Because they are recorded on his monuments with few indications of precise dates or the regnal year, the precise chronology of the subsequent campaigns is not clear. Late in the seventh year of his reign (April/May 1272 BCObsomer 2012: 530.), Ramesses II returned to Syria again. This time he proved more successful against his Hittite foes. During this campaign he split his army into two forces. One force was led by his son, Amun-her-khepeshef

Amun-her-khepeshef (died c. 1254 BC; also Amonhirkhopshef, Amun-her-wenemef and Amun-her-khepeshef A) was the firstborn son of Pharaoh Ramesses II and Queen Nefertari.

Name

He was born when his father was still a co-regent with Seti I ...

, and it chased warriors of the Šhasu tribes across the Negev

The Negev ( ; ) or Naqab (), is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its southern end is the Gulf of Aqaba and the resort town, resort city ...

as far as the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea (; or ; ), also known by #Names, other names, is a landlocked salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east, the Israeli-occupied West Bank to the west and Israel to the southwest. It lies in the endorheic basin of the Jordan Rift Valle ...

, capturing Edom

Edom (; Edomite language, Edomite: ; , lit.: "red"; Akkadian language, Akkadian: , ; Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom that stretched across areas in the south of present-day Jordan and Israel. Edom and the Edomi ...

-Seir

Seir or SEIR may refer to:

*Mount Seir, a mountainous region stretching between the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba

*Seir the Horite, chief of the Horites, a people mentioned in the Torah

*Sa'ir, also Seir, a Palestinian town in the Hebron Governor ...

. It then marched on to capture Moab

Moab () was an ancient Levant, Levantine kingdom whose territory is today located in southern Jordan. The land is mountainous and lies alongside much of the eastern shore of the Dead Sea. The existence of the Kingdom of Moab is attested to by ...

. The other force, led by Ramesses himself, attacked Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

and Jericho

Jericho ( ; , ) is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, and the capital of the Jericho Governorate. Jericho is located in the Jordan Valley, with the Jordan River to the east and Jerusalem to the west. It had a population of 20,907 in 2017.

F ...

. He, too, then entered Moab, where he rejoined his son. The reunited army then marched on Hesbon, Damascus, on to Kumidi, and finally, recaptured Upi (the land around Damascus), reestablishing Egypt's former sphere of influence.

Later Syrian campaigns

Ramesses extended his military successes in his eighth and ninth years. He crossed the Dog River (

Ramesses extended his military successes in his eighth and ninth years. He crossed the Dog River (Nahr al-Kalb

The Nahr al-Kalb (, meaning ''Dog River'') is a river in Lebanon. It runs for from a spring in Jeita near the Jeita Grotto to the Mediterranean Sea.

Historical significance

The Nahr al-Kalb is the ancient Lycus River. The river mouth is reno ...

) and pushed north into Amurru. His armies managed to march as far north as Dapur, where he had a statue of himself erected. The Egyptian pharaoh thus found himself in northern Amurru, well past Kadesh, in Tunip

Tunip (probably modern Tell 'Acharneh) was a city-state along the Orontes River in western Syria in the Late Bronze Age. It was large enough to be an urban center, but too small to be a dominant regional power. It was under the influence of var ...

, where no Egyptian soldier had been seen since the time of Thutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, (1479–1425 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. He is regarded as one of the greatest warriors, military commanders, and milita ...

, almost 120 years earlier. He laid siege to Dapur before capturing it, and returning to Egypt. By November 1272 BC, Ramesses was back in Egypt, at Heliopolis. His victory in the north proved ephemeral. After having reasserted his power over Canaan, Ramesses led his army north. A mostly illegible stele at the Dog River near Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

, (Lebanon), which appears to be dated to the king's second year, was probably set up there in his tenth year (1269 BC). The thin strip of territory pinched between Amurru and Kadesh did not make for a stable possession. Within a year, they had returned to the Hittite fold, so that Ramesses had to march against Dapur once more in his tenth year. This time he claimed to have fought the battle without even bothering to put on his corslet

A corslet or corselet is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as "a piece of defensive armour covering the body" and is first attested around 1500.

Such pieces of armour have existed in various forms under various names throughout much of hi ...

, until two hours after the fighting began. Six of Ramesses's youthful sons, still wearing their side locks, took part in this conquest. He took towns in Retjenu

Retjenu (''wiktionary:rṯnw, rṯnw; Reṯenu, Retenu''), later known as Khor, was the Ancient Egyptian name for the wider Syria (region), Syrian region, where the Semitic languages, Semitic-speaking Canaanites lived.Georg Steindorff, Steindorff, ...

, and Tunip in Naharin

Naharin, MdC transliteration ''nhrn'', was the ancient Egyptian term for the kingdom of Mitanni during the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt. The 18th dynasty was in conflict with the kingdom of Mitanni for control of the Levant from the ...

, later recorded on the walls of the Ramesseum

The Ramesseum is the Temples of a Million years, memorial temple (or mortuary temple) of Pharaoh Ramesses II ("Ramesses the Great", also spelled "Ramses" and "Rameses"). It is located in the Theban Necropolis in Upper Egypt, on the west of the Ni ...

. This second success at the location was equally as meaningless as his first, as neither power could decisively defeat the other in battle. In year eighteen, Ramesses erected a stele at Beth Shean

Beit She'an ( '), also known as Beisan ( '), or Beth-shean, is a town in the Northern District of Israel. The town lies at the Beit She'an Valley about 120 m (394 feet) below sea level.

Beit She'an is believed to be one of the oldest citie ...

, on 19 January 1261 BC.

Peace treaty with the Hittites

In Year 21 of Ramesses's reign, he concluded a peace treaty with the Hittites known to modern scholars as the ''Treaty of Kadesh''. Though this treaty settled the disputes over Canaan, its immediate impetus seems to have been a diplomatic crisis that occurred following

In Year 21 of Ramesses's reign, he concluded a peace treaty with the Hittites known to modern scholars as the ''Treaty of Kadesh''. Though this treaty settled the disputes over Canaan, its immediate impetus seems to have been a diplomatic crisis that occurred following Ḫattušili III

Hattusili III (Hittite language, Hittite: "from Hattusa") was king of the Hittite empire (New Kingdom) –1245 BC (middle chronology) or 1267–1237 BC (short chronology timeline)., pp.xiii-xiv

Early life and family

Much of what is known about ...

's accession to the Hittite throne. Ḫattušili had come to power by deposing his nephew Muršili III in the brief and bitter Hittite Civil War. Though the deposed king was initially sent into exile in Syria, he subsequently attempted to regain power and fled to Egypt once these attempts were discovered.

When Ḫattušili demanded his extradition, Ramesses II denied any knowledge of his whereabouts. When Ḫattušili insisted that Muršili was in Egypt, Ramesses's response suggested that Ḫattušili was being deceived by his subjects. This demand precipitated a crisis, and the two empires came close to war. Eventually, in the twenty-first year of his reign (1259 BCKitchen 1982: 75; Obsomer 2012: 195, 531.), Ramesses concluded an agreement at Kadesh to end the conflict.

The peace treaty was recorded in two versions, one in Egyptian hieroglyphs

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined Ideogram, ideographic, logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 1,000 distinct char ...

, the other in Hittite, using cuneiform script

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

; both versions survive. Such dual-language recording is common to many subsequent treaties. This treaty differs from others, in that the two language versions are worded differently. While the majority of the text is identical, the Hittite version says the Egyptians came suing for peace and the Egyptian version says the reverse. The treaty was given to the Egyptians in the form of a silver plaque, and this "pocket-book" version was taken back to Egypt and carved into the temple at Karnak

The Karnak Temple Complex, commonly known as Karnak (), comprises a vast mix of temples, pylons, chapels, and other buildings near Luxor, Egypt. Construction at the complex began during the reign of Senusret I (reigned 1971–1926 BC) in the ...

. The Egyptian account records Ramesses II's receipt of the Hittite peace treaty tablets on I Peret 21 of Year 21, corresponding to 10 November 1259 BC, according to the standard "Low Chronology" used by Egyptologists.

The treaty was concluded between Ramesses II and Ḫattušili III in year 21 of Ramesses's reign (c. 1259 BC). Its 18 articles call for peace between Egypt and Hatti and then proceeds to maintain that their respective deities also demand peace. The frontiers are not laid down in this treaty, but may be inferred from other documents. The Anastasy A papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, ''Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'' or ''papyruses'') can a ...

describes Canaan during the latter part of the reign of Ramesses II and enumerates and names the Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

n coastal towns under Egyptian control. The harbour town of Sumur, north of Byblos

Byblos ( ; ), also known as Jebeil, Jbeil or Jubayl (, Lebanese Arabic, locally ), is an ancient city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. The area is believed to have been first settled between 8800 and 7000BC and continuously inhabited ...

, is mentioned as the northernmost town belonging to Egypt, suggesting it contained an Egyptian garrison.

No further Egyptian campaigns in Canaan are mentioned after the conclusion of the peace treaty. The northern border seems to have been safe and quiet, so the rule of the pharaoh was strong until Ramesses II's death, and the subsequent waning of the dynasty. When the King of Mira attempted to involve Ramesses in a hostile act against the Hittites, the Egyptian responded that the times of intrigue in support of Mursili III, had passed. Ḫattušili III wrote to Kadashman-Enlil II

Kadašman-Enlil II, typically rendered d''ka-dáš-man-''dEN.LÍLThe replacement of the masculine determinative m by the divine one d is a distinction of Kassite monarchs after Nazi-Maruttaš. in contemporary inscriptions, meaning “he believes i ...

, Kassite

The Kassites () were a people of the ancient Near East. They controlled Babylonia after the fall of the Old Babylonian Empire from until (short chronology).

The Kassites gained control of Babylonia after the Hittite sack of Babylon in 1531 B ...

king of Karduniaš

Karduniaš (also transcribed Kurduniash, Karduniash or Karaduniše) is a Kassite term used for the kingdom centered on Babylonia and founded by the Kassite dynasty. It is used in the 1350-1335 BC Amarna letters correspondence, and is also used ...

(Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

) in the same spirit, reminding him of the time when his father, Kadashman-Turgu

Kadašman-Turgu, inscribed ''Ka-da-aš-ma-an Túr-gu'' and meaning ''he believes in Turgu'', a Kassite deity, (1281–1264 BC short chronology) was the 24th king of the Kassite or 3rd dynasty of Babylon. He succeeded his father, Nazi-Maruttaš, ...

, had offered to fight Ramesses II, the king of Egypt. The Hittite king encouraged the Babylonian to oppose another enemy, which must have been the king of Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

, whose allies had killed the messenger of the Egyptian king. Ḫattušili encouraged Kadashman-Enlil to come to his aid and prevent the Assyrians from cutting the link between the Canaanite province of Egypt and Mursili III, the ally of Ramesses.

Nubian campaigns

Ramesses II also campaigned south of the first cataract of the Nile into

Ramesses II also campaigned south of the first cataract of the Nile into Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

. When Ramesses was about 22 years old, two of his own sons, including Amun-her-khepeshef

Amun-her-khepeshef (died c. 1254 BC; also Amonhirkhopshef, Amun-her-wenemef and Amun-her-khepeshef A) was the firstborn son of Pharaoh Ramesses II and Queen Nefertari.

Name

He was born when his father was still a co-regent with Seti I ...

, accompanied him in at least one of those campaigns. By the time of Ramesses, Nubia had been a colony for 200 years, but its conquest was recalled in decoration from the temples Ramesses II built at Beit el-Wali (which was the subject of epigraphic work by the Oriental Institute during the Nubian salvage campaign of the 1960s), Gerf Hussein and Kalabsha

New Kalabsha is a promontory located near Aswan in Egypt.

Created during the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, it houses several important temples, structures, and other remains that have been relocated here from the sit ...

in northern Nubia. On the south wall of the Beit el-Wali temple, Ramesses II is depicted charging into battle against tribes south of Egypt in a war chariot, while his two young sons, Amun-her-khepsef and Khaemwaset, are shown behind him, also in war chariots. A wall in one of Ramesses's temples says he had to fight one battle with those tribes without help from his soldiers.

Libyan campaigns

During the reign of Ramesses II, the Egyptians were evidently active on a stretch along theMediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

coast, at least as far as Zawyet Umm El Rakham, where remains of a fortress described by its texts as built on Libyans land have been found. Although the exact events surrounding the foundation of the coastal forts and fortresses is not clear, some degree of political and military control must have been held over the region to allow their construction.

There are no detailed accounts of Ramesses II's undertaking large military actions against the Libyans

Demographics of Libya is the demography of Libya, specifically covering population density, Ethnic group, ethnicity, and Religion in Libya, religious affiliations, as well as other aspects of the Libyan population. All figures are from the Uni ...

, only generalised records of his conquering and crushing them, which may or may not refer to specific events that were otherwise unrecorded. It may be that some of the records, such as the Aswan

Aswan (, also ; ) is a city in Southern Egypt, and is the capital of the Aswan Governorate.

Aswan is a busy market and tourist centre located just north of the Aswan Dam on the east bank of the Nile at the first cataract. The modern city ha ...

Stele of his year 2, are harking back to Ramesses's presence on his father's Libyan campaigns. Perhaps it was Seti I

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek language, Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom of Egypt, New Kingdom period, ruling or 1290 BC to 1279 BC. He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and th ...

who achieved this supposed control over the region, and who planned to establish the defensive system, in a manner similar to how he rebuilt those to the east, the Ways of Horus across Northern Sinai.

Sed festivals

As of Year 28 of his reign, Ramesses II favored the god

As of Year 28 of his reign, Ramesses II favored the god Amun

Amun was a major ancient Egyptian deity who appears as a member of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad. Amun was attested from the Old Kingdom together with his wife Amunet. His oracle in Siwa Oasis, located in Western Egypt near the Libyan Desert, r ...

above all other divinities, as evidenced in the texts of two separate ostraca

An ostracon (Greek language, Greek: ''ostrakon'', plural ''ostraka'') is a piece of pottery, usually broken off from a vase or other earthenware vessel. In an archaeology, archaeological or epigraphy, epigraphical context, ''ostraca'' refer ...

discovered at Deir el-Medina.

By tradition, in the 30th year of his reign, Ramesses celebrated a jubilee called the Sed festival

The Sed festival (''ḥb-sd'', Egyptian language#Egyptological pronunciation, conventional pronunciation ; also known as Heb Sed or Feast of the Tail) was an ancient Egyptian ceremony that celebrated the continued rule of a pharaoh. The name is ...

. These were held to honour and rejuvenate the pharaoh's strength. Only halfway through what would be a 66-year reign, Ramesses had already eclipsed all but a few of his greatest predecessors in his achievements. He had brought peace, maintained Egyptian borders, and built numerous monuments across the empire. His country was more prosperous and powerful than it had been in nearly a century.

Sed festivals traditionally were held again every three years after the 30th year; Ramesses II, who sometimes held them after two years, eventually celebrated an unprecedented thirteen or fourteen.

Building projects and monuments

In the third year of his reign, Ramesses started the most ambitious building project after thepyramids

A pyramid () is a Nonbuilding structure, structure whose visible surfaces are triangular in broad outline and converge toward the top, making the appearance roughly a Pyramid (geometry), pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid ca ...

, which were built almost 1,500 years earlier. Ramesses built extensively from the Delta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), the fourth letter of the Greek alphabet

* D (NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta"), the fourth letter in the Latin alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* Delta Air Lines, a major US carrier ...

to Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

, "covering the land with buildings in a way no monarch before him had."

Some of the activities undertaken were focused on remodeling or usurping existing works, improving masonry techniques, and using art as propaganda.

*In Thebes, the ancient temples

A temple (from the Latin ) is a place of worship, a building used for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. By convention, the specially built places of worship of some religions are commonly called "temples" in Engli ...

were transformed, so that each of them reflected honour to Ramesses as a symbol of his putative divine nature and power.

*The elegant but shallow reliefs of previous pharaohs were easily transformed, and so their images and words could easily be obliterated by their successors. Ramesses insisted that his carvings be deeply engraved into the stone, which made them not only less susceptible to later alteration, but also made them more prominent in the Egyptian sun, reflecting his relationship with the sun deity, Ra.

*Ramesses used art as a means of propaganda for his victories over foreigners, which are depicted on numerous temple reliefs.

*His cartouche

upalt=A stone face carved with coloured hieroglyphics. Two cartouches - ovoid shapes with hieroglyphics inside - are visible at the bottom., Birth and throne cartouches of Pharaoh KV17.html" ;"title="Seti I, from KV17">Seti I, from KV17 at the ...

s are prominently displayed even in buildings that he did not construct.

* He founded a new capital city in the Delta during his reign, called Pi-Ramesses

Pi-Ramesses (; Ancient Egyptian: , meaning "House of Ramesses") was the new capital built by the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Nineteenth Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) at Qantir, near the old site of Avaris. The city had served as a ...

. It previously had served as a summer palace during Seti I's reign.

* Ramesses II expanded gold mining operations in Akuyati (modern day Wadi Allaqi).

Ramesses also undertook many new construction projects. Two of his biggest works, besides Pi-Ramesses

Pi-Ramesses (; Ancient Egyptian: , meaning "House of Ramesses") was the new capital built by the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Nineteenth Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) at Qantir, near the old site of Avaris. The city had served as a ...

, were the temple complex of Abu Simbel

Abu Simbel is a historic site comprising two massive Rock-cut architecture, rock-cut Egyptian temple, temples in the village of Abu Simbel (village), Abu Simbel (), Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt, near the border with Sudan. It is located on t ...

and the Ramesseum

The Ramesseum is the Temples of a Million years, memorial temple (or mortuary temple) of Pharaoh Ramesses II ("Ramesses the Great", also spelled "Ramses" and "Rameses"). It is located in the Theban Necropolis in Upper Egypt, on the west of the Ni ...

, a mortuary temple

Mortuary temples (or funerary temples) were temples that were erected adjacent to, or in the vicinity of, royal tombs in Ancient Egypt. The temples were designed to commemorate the reign of the Pharaoh under whom they were constructed, as well as f ...

in western Thebes.

Pi-Ramesses

Ramesses II moved the capital of his kingdom from Thebes in the Nile valley to a new site in the eastern Delta. His motives are uncertain, although he possibly wished to be closer to his territories in Canaan and Syria. The new city of Pi-Ramesses (or to give the full name, '' Pi-Ramesses Aa-nakhtu'', meaning "Domain of Ramesses, Great in Victory") was dominated by huge temples and his vast residential palace, complete with its own zoo. In the 10th century AD, the Bible exegete RabbiSaadia Gaon

Saʿadia ben Yosef Gaon (892–942) was a prominent rabbi, Geonim, gaon, Jews, Jewish philosopher, and exegesis, exegete who was active in the Abbasid Caliphate.

Saadia is the first important rabbinic figure to write extensively in Judeo-Arabic ...

believed that the biblical site of Ramesses had to be identified with Ain Shams

Ain Shams (also spelled Ayn or Ein - , , ) is a district in the Eastern Area of Cairo, Egypt. The name means "Eye of the Sun" in Arabic, referring to the fact that the district contained the ruins of the ancient city of Heliopolis, once the spir ...

. For a time, during the early 20th century, the site was misidentified as that of Tanis

Tanis ( ; ; ) or San al-Hagar (; ; ; or or ; ) is the Greek name for ancient Egyptian ''ḏꜥn.t'', an important archaeological site in the northeastern Nile Delta of ancient Egypt, Egypt, and the location of a city of the same name. Tanis ...

, due to the amount of statuary and other material from Pi-Ramesses found there, but it now is recognized that the Ramesside remains at Tanis were brought there from elsewhere, and the real Pi-Ramesses lies about 30 km (18.6 mi) south, near modern Qantir

Qantir () is a village in Egypt. Qantir is believed to mark what was probably the ancient site of the 19th Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II's capital, Pi-Ramesses or Per-Ramesses ("House or Domain of Ramesses"). It is situated around north of Faqous ...

. The colossal feet of the statue of Ramesses are almost all that remains above ground today. The rest is buried in the fields.

Ramesseum

The temple complex built by Ramesses II between Qurna and the desert has been known as the

The temple complex built by Ramesses II between Qurna and the desert has been known as the Ramesseum

The Ramesseum is the Temples of a Million years, memorial temple (or mortuary temple) of Pharaoh Ramesses II ("Ramesses the Great", also spelled "Ramses" and "Rameses"). It is located in the Theban Necropolis in Upper Egypt, on the west of the Ni ...

since the 19th century. The Greek historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human species; as well as the ...

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

marveled at the gigantic temple, now no more than a few ruins.

Oriented northwest and southeast, the temple was preceded by two courts. An enormous pylon stood before the first court, with the royal palace at the left and the gigantic statue of the king at the back. Only fragments of the base and torso remain of the syenite

Syenite is a coarse-grained intrusive igneous rock with a general composition similar to that of granite, but deficient in quartz, which, if present at all, occurs in relatively small concentrations (< 5%). It is considered a registers, feast and honour of the phallic deity Min, god of fertility.

On the opposite side of the court, the few Osiride pillars and columns still remaining may furnish an idea of the original grandeur. Scattered remains of the two statues of the seated king also may be seen, one in pink granite and the other in black granite, which once flanked the entrance to the temple. Thirty-nine out of the forty-eight columns in the great hypostyle hall (41 × 31 m) still stand in the central rows. They are decorated with the usual scenes of the king before various deities. Part of the ceiling, decorated with gold stars on a blue ground, also has been preserved. Ramesses's children appear in the procession on the few walls left. The sanctuary was composed of three consecutive rooms, with eight columns and the

During the examination, scientific analysis revealed battle-wounds, old fractures,

During the examination, scientific analysis revealed battle-wounds, old fractures,

The tomb of the most important

The tomb of the most important

Though scholars generally do not recognize the biblical portrayal of the Exodus as an actual historical event, various historical pharaohs have been proposed as the corresponding ruler at the time the story takes place, with Ramesses II as the most popular candidate for

Though scholars generally do not recognize the biblical portrayal of the Exodus as an actual historical event, various historical pharaohs have been proposed as the corresponding ruler at the time the story takes place, with Ramesses II as the most popular candidate for

Egypt's Golden Empire: Ramesses II

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ramesses 02 13th-century BC pharaohs Pharaohs of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt 13th-century BC deaths 14th-century BC births Ancient Egyptian mummies Egyptian Museum Seti I Book of Exodus

tetrastyle

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cultu ...

cell. Part of the first room, with the ceiling decorated with astral scenes, and few remains of the second room are all that is left. Vast storerooms built of mud bricks stretched out around the temple. Traces of a school for scribes were found among the ruins.

A temple of Seti I

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek language, Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom of Egypt, New Kingdom period, ruling or 1290 BC to 1279 BC. He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and th ...

, of which nothing remains beside the foundations, once stood to the right of the hypostyle hall.

Abu Simbel

In 1255 BC, Ramesses and his queenNefertari

Nefertari, also known as Nefertari Meritmut, was an Egyptian queen and the first of the Great Royal Wife, Great Royal Wives (or principal wives) of Ramesses II, Ramesses the Great. She is one of the best known Egyptian queens, among such women ...

had traveled into Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

to inaugurate a new temple, Abu Simbel

Abu Simbel is a historic site comprising two massive Rock-cut architecture, rock-cut Egyptian temple, temples in the village of Abu Simbel (village), Abu Simbel (), Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt, near the border with Sudan. It is located on t ...

. It is said to be ego cast into stone; the man who built it intended not only to become Egypt's greatest pharaoh, but also one of its deities.

The temple at Abu Simbel was discovered in 1813 by the Swiss Orientalist and traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt

Johann Ludwig (also known as John Lewis, Jean Louis) Burckhardt (24 November 1784 – 15 October 1817) was a Swiss traveller, geographer and Orientalist. Burckhardt assumed the alias ''Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah'' during his travels in Arabia ...

. An enormous pile of sand almost completely covered the facade and its colossal statues, blocking the entrance for four more years. The Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

n explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni

Giovanni Battista Belzoni (; 5 November 1778 – 3 December 1823), sometimes known as The Great Belzoni, was a prolific Italian explorer and pioneer archaeologist of Egyptian antiquities. He is known for his removal to England of the seven-tonn ...

reached the interior on 4 August 1817.

Other Nubian monuments

As well as the temples of Abu Simbel, Ramesses left other monuments to himself in Nubia. His early campaigns are illustrated on the walls of theTemple of Beit el-Wali

The Temple of Beit el-Wali is a rock-cut ancient Egyptian temple in Nubia which was built by Pharaoh Ramesses II and dedicated to the deities of Amun-Re, Re-Horakhti, Khnum and Anuket.Arnold & Strudwick (2003), p.29 It was the first in a series ...

(now relocated to New Kalabsha

New Kalabsha is a promontory located near Aswan in Egypt.

Created during the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, it houses several important temples, structures, and other remains that have been relocated here from the site o ...

). Other temples dedicated to Ramesses are Derr and Gerf Hussein (also relocated to New Kalabsha). For the temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal

Jebel Barkal or Gebel Barkal () is a mesa or large rock outcrop located 400 km north of Khartoum, next to Karima in Northern State in Sudan, on the Nile River, in the region that is sometimes called Nubia. The jebel is 104 m tall, has a f ...

, the temple's foundation probably dates during the reign of Thutmose III, while the temple was shaped during his reign and that of Ramesses II.

Other archeological discoveries

The colossal statue of Ramesses II dates back 3,200 years, and was originally discovered in six pieces in a temple near Memphis, Egypt. Weighing some , it was transported, reconstructed, and erected in Ramesses Square in Cairo in 1955. In August 2006, contractors relocated it to save it from exhaust fumes that were causing it to deteriorate. The new site is near theGrand Egyptian Museum

The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM; ''al-Matḥaf al-Maṣriyy al-Kabīr''), also known as the Giza Museum, is an archaeological museum in Giza, Egypt, about from the Giza pyramid complex. The Museum hosts over 100,000 artifacts from ancient E ...

.

In 2018, a group of archeologists in Cairo's Matariya neighborhood discovered pieces of a booth with a seat that, based on its structure and age, may have been used by Ramesses. "The royal compartment consists of four steps leading to a cubic platform, which is believed to be the base of the king's seat during celebrations or public gatherings," such as Ramesses' inauguration and Sed festivals. It may have also gone on to be used by others in the Ramesside Period

The New Kingdom, also called the Egyptian Empire, refers to ancient Egypt between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC. This period of ancient Egyptian history covers the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth dynasties. Through radioc ...

, according to the mission's head. The excavation mission also unearthed "a collection of scarabs, amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word , which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects a perso ...

s, clay pots and blocks engraved with hieroglyphic

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined ideographic, logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 1,000 distinct characters. ...

text."

In December 2019, a red granite royal bust of Ramesses II was unearthed by an Egyptian archaeological mission in the village of Mit Rahina in Giza. The bust depicted Ramesses II wearing a wig with the symbol "Ka" on his head. Its measurements were 55 cm (21.65 in) wide, 45 cm (17.71 in) thick and 105 cm (41.33 in) long. Alongside the bust, limestone blocks appeared showing Ramesses II during the Heb-Sed religious ritual. "This discovery is considered one of the rarest archaeological discoveries. It is the first-ever Ka statue made of granite to be discovered. The only Ka statue that was previously found is made of wood and it belongs to one of the kings of the 13th dynasty of ancient Egypt which is displayed at the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square

Tahrir Square (, ; ), also known as Martyr Square, is a public town square in downtown Cairo, Egypt. The square has been the location and focus for political demonstrations. The 2011 Egyptian revolution and the resignation of President of Egypt, ...

," said archaeologist Mostafa Waziri

Mostafa Waziri (, occasionally cited as Mostafa Waziry) is an Egyptians, Egyptian archaeology, archaeologist, Egyptology, Egyptologist, and the former secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities of Egypt.

He received his PhD from Soh ...

.

In September 2024, it was published that during an archaeological excavation of a 3,200 year old fort along the Nile, researches found a golden sword with Ramses II signature on it.

Death and burial

The Egyptian scholarManetho

Manetho (; ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος, ''fl''. 290–260 BCE) was an Egyptian priest of the Ptolemaic Kingdom who lived in the early third century BCE, at the very beginning of the Hellenistic period. Little is certain about his ...

(third century BC) attributed Ramesses a reign of 66 years and 2 months.

By the time of his death, aged about 90 years, Ramesses was suffering from severe dental problems and was plagued by arthritis

Arthritis is a general medical term used to describe a disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, Joint effusion, swelling, and decreased range of motion of ...

, hardening of the arteries and heart disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is any disease involving the heart or blood vessels. CVDs constitute a class of diseases that includes: coronary artery diseases (e.g. angina pectoris, angina, myocardial infarction, heart attack), heart failure, ...

. According to Maurice Bucaille, he died from drowning, while other researchers say he died of the various diseases he had. He had made Egypt rich from all the supplies and bounty he had collected from other empires, outliving many of his wives and children and leaving great memorials all over Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. Nine more pharaohs took the name Ramesses in his honour.

The Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

states that Firawn, who is normally identified to have represented Ramses, died from drowning

Drowning is a type of Asphyxia, suffocation induced by the submersion of the mouth and nose in a liquid. Submersion injury refers to both drowning and near-miss incidents. Most instances of fatal drowning occur alone or in situations where othe ...

. Maurice Bucaille supported this claim from the research he had done on the body, which eventually lead to his conversion to Islam. Ali Gomaa

Ali Gomaa (, Egyptian Arabic: ; born 3 March 1952) is an Egyptian Islamic scholar, jurist, and public figure who has taken a number of controversial political stances. He specializes in Islamic Legal Theory. He follows the Shafi`i school of Isl ...

also announced in 2020 that when there were tests run on the body of Ramses, the reason of death was found to be suffocation

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects all the tissues and organs, some more rapidly than others. There are m ...

. Egyptian archaelogist Zahi Hawass

Zahi Abass Hawass (; born May 28, 1947) is an Egyptians, Egyptian archaeology, archaeologist, Egyptology, Egyptologist, and former Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (Egypt), Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, a position he held twice. He has ...

however states that it's not possible to know whether he died of drowning or not, as the lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of the heart. Their function in the respiratory syste ...

are not present in the mummy

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and Organ (biology), organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to Chemical substance, chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the ...

.

Mummy

Originally Ramesses II was buried in tombKV7

Tomb KV7 was the tomb of Ramesses II ("Ramesses the Great"), an ancient Egyptian pharaoh during the Nineteenth Dynasty.

It is located in the Valley of the Kings opposite the tomb of his sons, KV5, and near to the tomb of his son and successor M ...

in the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is an area in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the Eighteenth Dynasty to the Twentieth Dynasty, rock-cut tombs were excavated for pharaohs and power ...

, but because of looting in the valley, priests later transferred the body to a holding area, re-wrapped it, and placed it inside the tomb of queen Ahmose Inhapy. Seventy-two hours later it was again moved, to the tomb

A tomb ( ''tumbos'') or sepulchre () is a repository for the remains of the dead. It is generally any structurally enclosed interment space or burial chamber, of varying sizes. Placing a corpse into a tomb can be called '' immurement'', alth ...

of the high priest Pinedjem II

Pinedjem II was a High Priest of Amun at Thebes in Ancient Egypt from 990 BC to 969 BC and was the ''de facto'' ruler of the south of the country.

Life

He was married to his full sister Isetemkheb D (both children of Menkheperre, the High ...

. All of this is recorded in hieroglyphics on the linen covering the body of his coffin. His mummy

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and Organ (biology), organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to Chemical substance, chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the ...

was eventually discovered in 1881 in TT320

The Royal Cache, technically known as TT320 (previously referred to as DB320), is an Ancient Egyptian tomb located next to Deir el-Bahari, in the Theban Necropolis, opposite the modern city of Luxor.

It contains an extraordinary collection of mu ...

inside an ordinary wooden coffin and is now in Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

's National Museum of Egyptian Civilization

The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC) is a large museum located in Old Cairo, a district of Cairo, Egypt.

Partially opened in 2017, the museum was officially inaugurated on 3 April 2021, with the moving of 22 mummies, including 1 ...

(until 3 April 2021 it was in the Egyptian Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, commonly known as the Egyptian Museum (, Egyptian Arabic: ) (also called the Cairo Museum), located in Cairo, Egypt, houses the largest collection of Ancient Egypt, Egyptian antiquities in the world. It hou ...

).

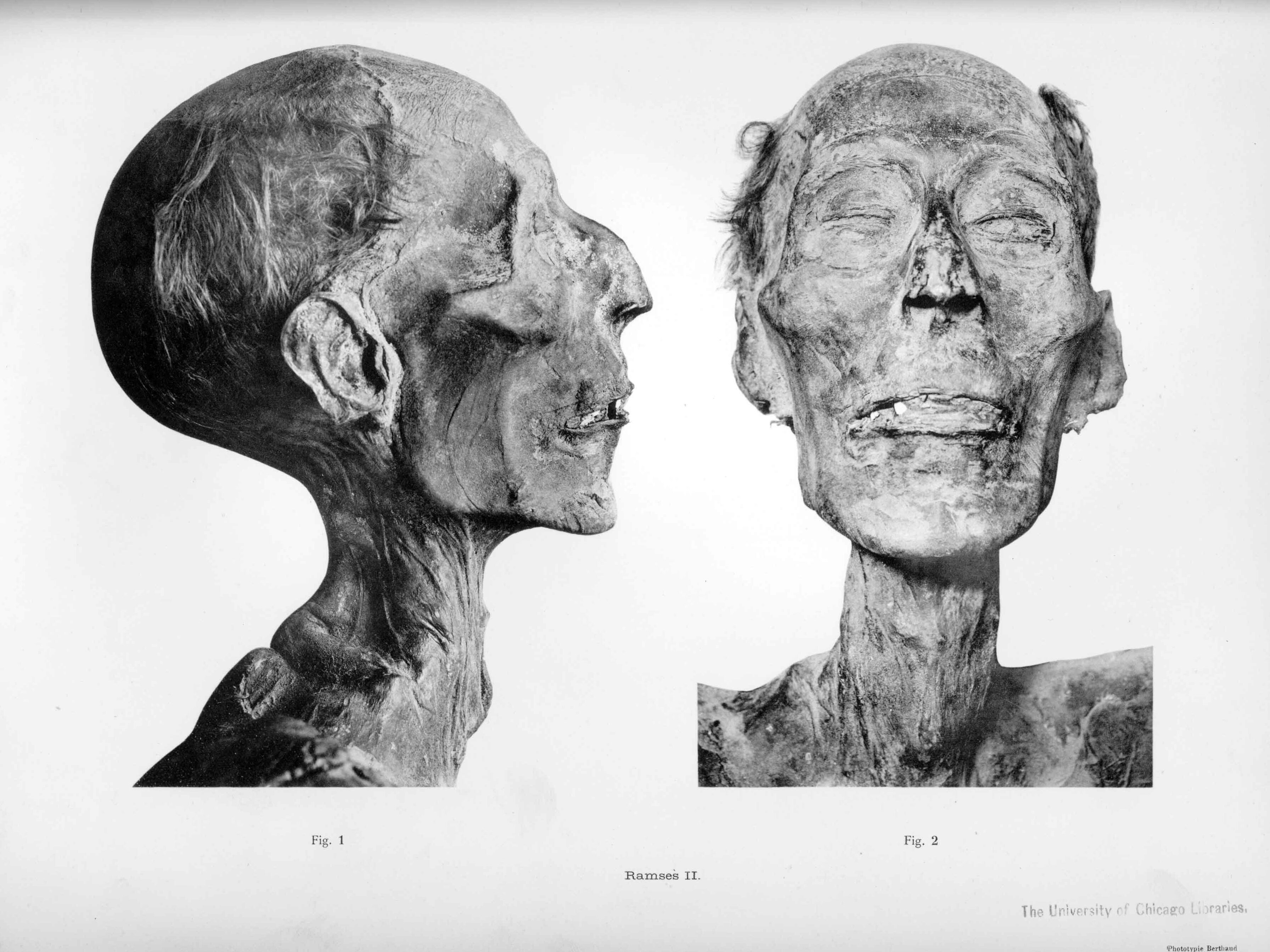

The pharaoh's mummy reveals an aquiline nose

An aquiline nose is a human nose with a prominent bridge, giving it the appearance of being curved or slightly bent. The word ''aquiline'' comes from the Latin word ' ("eagle-like"), an allusion to the curved beak of an eagle. While some have ...

and strong jaw. It stands at about . Gaston Maspero

Sir Gaston Camille Charles Maspero (23 June 1846 – 30 June 1916) was a French Egyptologist and director general of excavations and antiquities for the Egyptian government. Widely regarded as the foremost Egyptologist of his generation, he be ...

, who first unwrapped the mummy of Ramesses II, writes, "on the temples there are a few sparse hairs, but at the poll the hair is quite thick, forming smooth, straight locks about five centimeters in length. White at the time of death, and possibly auburn during life, they have been dyed a light red by the spices (henna) used in embalming ... the moustache and beard are thin. ... The hairs are white, like those of the head and eyebrows ... the skin is of earthy brown, splotched with black ... the face of the mummy gives a fair idea of the face of the living king."

In 1975, Maurice Bucaille, a French doctor, examined the mummy at the Cairo Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, commonly known as the Egyptian Museum (, Egyptian Arabic: ) (also called the Cairo Museum), located in Cairo, Egypt, houses the largest collection of Egyptian antiquities in the world. It houses over 120, ...

and found it in poor condition. French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, ; ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as simply Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Ministry of the Economy ...

succeeded in convincing Egyptian authorities to send the mummy to France for treatment. In September 1976, it was greeted at Paris–Le Bourget Airport

Paris–Le Bourget Airport () is an airport located within portions of the communes of Le Bourget, Bonneuil-en-France, Dugny and Gonesse, north-northeast of Paris, France.

Once Paris's principal airport, it is now used only for general a ...

with full military honours befitting a king, then taken to a laboratory at the Musée de l'Homme

The Musée de l'Homme (; literally "Museum of Mankind" or "Museum of Humanity") is an anthropology museum in Paris, France. It was established in 1937 by Paul Rivet for the 1937 ''Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moder ...

. Persistent claims that the mummy was issued with a passport

A passport is an official travel document issued by a government that certifies a person's identity and nationality for international travel. A passport allows its bearer to enter and temporarily reside in a foreign country, access local aid ...

for the journey are incorrect, but may be based on the French word being used to describe the extensive documentation required.

The mummy was forensically tested in 1976 by Pierre-Fernand Ceccaldi, the chief forensic

Forensic science combines principles of law and science to investigate criminal activity. Through crime scene investigations and laboratory analysis, forensic scientists are able to link suspects to evidence. An example is determining the time and ...

scientist at the Criminal Identification Laboratory of Paris. Ceccaldi observed that the mummy had slightly wavy, red hair; from this trait combined with cranial features, he concluded that Ramesses II was of a "Berber type" and hence – according to Ceccaldi's analysis – fair-skinned. Subsequent microscopic inspection of the roots of Ramesses II's hair proved that the king's hair originally was red, which suggests that he came from a family of redheads. This has more than just cosmetic significance: in ancient Egypt people with red hair were associated with the deity Set

Set, The Set, SET or SETS may refer to:

Science, technology, and mathematics Mathematics

*Set (mathematics), a collection of elements

*Category of sets, the category whose objects and morphisms are sets and total functions, respectively

Electro ...

, the slayer of Osiris

Osiris (, from Egyptian ''wikt:wsjr, wsjr'') was the ancient Egyptian deities, god of fertility, agriculture, the Ancient Egyptian religion#Afterlife, afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation in ancient Egyptian religion. He was ...

, and the name of Ramesses II's father, Seti I, means "follower of Seth". Cheikh Anta Diop

Cheikh Anta Diop (29 December 1923 – 7 February 1986) was a Senegalese historian, anthropologist, physicist, and politician who studied the human race's origins and pre-colonial African culture. Diop's work is considered foundational to the the ...

disputed the results of the study, arguing that the structure of hair morphology cannot determine the ethnicity of a mummy and that a comparative study should have featured Nubians

Nubians () ( Nobiin: ''Nobī,'' ) are a Nilo-Saharan speaking ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of th ...

in Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ', shortened to , , locally: ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the Nile River valley south of the delta and the 30th parallel North. It thus consists of the entire Nile River valley from Cairo south to Lake N ...

before a conclusive judgement was reached.

In 2006, French police arrested a man who tried to sell several tufts of Ramesses' hair on the Internet. Jean-Michel Diebolt said he had got the relics from his late father, who had been on the analysis team in the 1970s. They were returned to Egypt the following year.

arthritis

Arthritis is a general medical term used to describe a disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, Joint effusion, swelling, and decreased range of motion of ...

and poor circulation. Ramesses II's arthritis is believed to have made him walk with a hunched back for the last decades of his life. A 2004 study excluded ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a type of arthritis from the disease spectrum of axial spondyloarthritis. It is characterized by long-term inflammation of the joints of the spine, typically where the spine joins the pelvis. With AS, eye and bow ...

as a possible cause and proposed diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a condition characterized by abnormal calcification/bone formation (hyperostosis) of the soft tissues surrounding the joints of the spine, and also of the peripheral or appendicular skeleton. In ...

as a possible alternative, which was confirmed by more recent work. A significant hole in the pharaoh's mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

was detected. Researchers observed "an abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body, usually caused by bacterial infection. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pre ...

by his teeth (which) was serious enough to have caused death by infection, although this cannot be determined with certainty".

After being irradiated in an attempt to eliminate fungi and insects, the mummy was returned from Paris to Egypt in May 1977.

In April 2021, his mummy was moved from the old Egyptian Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, commonly known as the Egyptian Museum (, Egyptian Arabic: ) (also called the Cairo Museum), located in Cairo, Egypt, houses the largest collection of Ancient Egypt, Egyptian antiquities in the world. It hou ...

to the new National Museum of Egyptian Civilization

The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC) is a large museum located in Old Cairo, a district of Cairo, Egypt.

Partially opened in 2017, the museum was officially inaugurated on 3 April 2021, with the moving of 22 mummies, including 1 ...