Race And Intelligence Controversy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the race and intelligence controversy concerns the historical development of a debate about possible explanations of group differences encountered in the study of

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the idea that there are differences in the brain structures and brain sizes of different races, and that this implied differences in intelligence, was a popular topic, inspiring numerous typological studies. Samuel Morton's ''Crania Americana'', published in 1839, was one such study, arguing that intelligence was correlated with brain size and that both of these metrics varied between racial groups.

Through the publication of his book ''

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the idea that there are differences in the brain structures and brain sizes of different races, and that this implied differences in intelligence, was a popular topic, inspiring numerous typological studies. Samuel Morton's ''Crania Americana'', published in 1839, was one such study, arguing that intelligence was correlated with brain size and that both of these metrics varied between racial groups.

Through the publication of his book ''

The first practical intelligence test was developed between 1905 and 1908 by

The first practical intelligence test was developed between 1905 and 1908 by

In the 1930s, the English psychologist

In the 1930s, the English psychologist  In 1935,

In 1935,

The

The  In a 1968 article published in ''Disadvantaged Child'', Jensen questioned the effectiveness of child development and antipoverty programs, writing: "As a social policy, avoidance of the issue could be harmful to everyone in the long run, especially to future generations of Negroes, who could suffer the most from well-meaning but misguided and ineffective attempts to improve their lot." In 1969 Jensen wrote a long article in the

In a 1968 article published in ''Disadvantaged Child'', Jensen questioned the effectiveness of child development and antipoverty programs, writing: "As a social policy, avoidance of the issue could be harmful to everyone in the long run, especially to future generations of Negroes, who could suffer the most from well-meaning but misguided and ineffective attempts to improve their lot." In 1969 Jensen wrote a long article in the  Jensen and Herrnstein's articles were widely discussed.

Jensen and Herrnstein's articles were widely discussed.  The academic debate also became entangled with the so-called "Burt Affair", because Jensen's article had partially relied on the 1966

The academic debate also became entangled with the so-called "Burt Affair", because Jensen's article had partially relied on the 1966

race and intelligence

Discussions of race and intelligence—specifically regarding claims of differences in intelligence along racial lines—have appeared in both popular science and academic research since the modern concept of race was first introduced. With th ...

. Since the beginning of IQ testing

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardized tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence. Originally, IQ was a score obtained by dividing a person's mental age score, obtained by administering ...

around the time of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, there have been observed differences between the average scores of different population groups, and there have been debates over whether this is mainly due to environmental and cultural factors, or mainly due to some as yet undiscovered genetic factor, or whether such a dichotomy between environmental and genetic factors is the appropriate framing of the debate. Today, the scientific consensus is that genetics does not explain differences in IQ test performance between racial groups.

Pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

claims of inherent differences in intelligence between races have played a central role in the history of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

. In the late 19th and early 20th century, group differences in intelligence were often assumed to be racial in nature. Apart from intelligence tests, research relied on measurements such as brain size or reaction times. By the mid-1940s most psychologists had adopted the view that environmental and cultural factors predominated.

In the mid-1960s, physicist William Shockley

William Bradford Shockley ( ; February 13, 1910 – August 12, 1989) was an American solid-state physicist, electrical engineer, and inventor. He was the manager of a research group at Bell Labs that included John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brat ...

sparked controversy by claiming there might be genetic reasons that black people

Black is a racial classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid- to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin and often additional phenotypical ...

in the United States tended to score lower on IQ tests than white people

White is a Race (human categorization), racial classification of people generally used for those of predominantly Ethnic groups in Europe, European ancestry. It is also a Human skin color, skin color specifier, although the definition can var ...

. In 1969 the educational psychologist Arthur Jensen

Arthur Robert Jensen (August 24, 1923 – October 22, 2012) was an American psychologist and writer. He was a professor of educational psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. Jensen was known for his work in psychometrics an ...

published a long article with the suggestion that compensatory education could have failed to that date because of genetic group differences. A similar debate among academics followed the publication in 1994 of ''The Bell Curve

''The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life'' is a 1994 book by the psychologist Richard J. Herrnstein and the political scientist Charles Murray in which the authors argue that human intelligence is substantially influe ...

'' by Richard Herrnstein

Richard Julius Herrnstein (May 20, 1930 – September 13, 1994) was an American psychologist at Harvard University. He was an active researcher in animal learning in the Skinnerian tradition. Herrnstein was the Edgar Pierce Professor of Psycho ...

and Charles Murray. Their book prompted a renewal of debate on the issue and the publication of several interdisciplinary books on the issue. A 1995 report from the American Psychological Association

The American Psychological Association (APA) is the main professional organization of psychologists in the United States, and the largest psychological association in the world. It has over 170,000 members, including scientists, educators, clin ...

responded to the controversy, finding no conclusive explanation for the observed differences between average IQ scores of racial groups. More recent work by James Flynn, William Dickens

William Theodore Dickens (born December 31, 1953) is an American economist. He is a University Distinguished Professor of Economics and Social Policy at Northeastern University.

Career

Dickens was on the faculty of the University of California, ...

and Richard Nisbett

Richard Eugene Nisbett (born June 1, 1941) is an American social psychologist and writer. He is the Theodore M. Newcomb Distinguished Professor of social psychology and co-director of the Culture and Cognition program at the University of Michig ...

has highlighted the narrowing gap between racial groups in IQ test performance, along with other corroborating evidence that environmental rather than genetic factors are the cause of these differences.

History

Early history

In the 18th century, debates surrounding the institution ofslavery in the Americas

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and religions from ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The social, economic, and legal positions ...

hinged on the question of whether innate differences in intellectual capacity existed between races, in particular between black people and white people. Some European philosophers and scientists, such as Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

, David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

, Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

, and Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

, either argued or simply presupposed that white people were intellectually superior.

Others, such as Henri Gregoire

Henri is the French form of the masculine given name Henry, also in Estonian, Finnish, German and Luxembourgish. Bearers of the given name include:

People French nobles

* Henri I de Montmorency (1534–1614), Marshal and Constable of France

* H ...

and Constantin de Chasseboeuf, argued that ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

had been a black civilization, and that it was therefore black people who had "discovered the elements of science and art, at a time when all other men were barbarous." During the French Revolution, Jean-Baptiste Belley

Jean-Baptiste Belley ( – 6 August 1805) was a Saint Dominican and French politician. A native of Senegal and formerly enslaved in the colony of Saint-Domingue, in the French West Indies, he was an elected member of the Estates General, the ...

, an elected member of the National Convention

The National Convention () was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the ...

and the Council of Five Hundred

The Council of Five Hundred () was the lower house of the legislature of the French First Republic under the Constitution of the Year III. It operated from 31 October 1795 to 9 November 1799 during the French Directory, Directory () period of t ...

who had been born in Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

, became a leading proponent of the idea of racial intellectual equality.

In 1785, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

wrote of his "suspicion" that black people were "inferior to... whites in endowments both of body and mind." However, in 1791, after corresponding with the free African-American polymath Benjamin Banneker

Benjamin Banneker (November 9, 1731October 19, 1806) was an American Natural history, naturalist, mathematician, astronomer and almanac author. A Land tenure, landowner, he also worked as a surveying, surveyor and farmer.

Born in Baltimore Co ...

, Jefferson wrote that he hoped to see such "instances of moral eminence so multiplied as to prove that the want of talents observed in them is merely the effect of their degraded condition, and not proceeding from any difference in the structure of the parts on which intellect depends."

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the idea that there are differences in the brain structures and brain sizes of different races, and that this implied differences in intelligence, was a popular topic, inspiring numerous typological studies. Samuel Morton's ''Crania Americana'', published in 1839, was one such study, arguing that intelligence was correlated with brain size and that both of these metrics varied between racial groups.

Through the publication of his book ''

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the idea that there are differences in the brain structures and brain sizes of different races, and that this implied differences in intelligence, was a popular topic, inspiring numerous typological studies. Samuel Morton's ''Crania Americana'', published in 1839, was one such study, arguing that intelligence was correlated with brain size and that both of these metrics varied between racial groups.

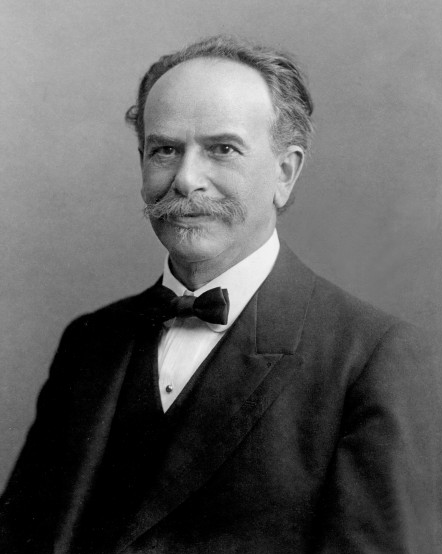

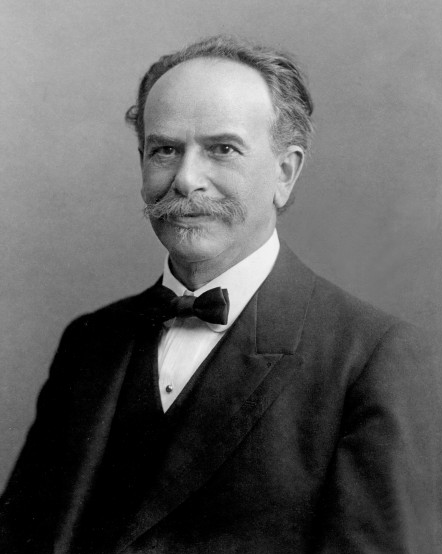

Through the publication of his book ''Hereditary Genius

''Hereditary Genius: An Inquiry Into Its Laws and Consequences'' is a book by Francis Galton about the genetic inheritance of intelligence. It was first published in 1869 by Macmillan Publishers. The first American edition was published by D. A ...

'' in 1869, polymath Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911) was an English polymath and the originator of eugenics during the Victorian era; his ideas later became the basis of behavioural genetics.

Galton produced over 340 papers and b ...

spurred interest in the study of mental abilities, particularly as they relate to heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic infor ...

and eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

. Lacking the means to directly measure intellectual ability, Galton attempted to estimate the intelligence of various racial and ethnic groups. He based his estimations on observations from his and others' travels, the number and quality of intellectual achievements of different groups, and on the percentage of "eminent men" in each of these groups. Galton hypothesized that intelligence was normally distributed in all racial and ethnic groups, and that the means of these distributions varied between the groups. In Galton's estimation, ancient Attic Greeks had been the people with the highest incidence of genius

Genius is a characteristic of original and exceptional insight in the performance of some art or endeavor that surpasses expectations, sets new standards for the future, establishes better methods of operation, or remains outside the capabiliti ...

intelligence, followed by contemporary Englishmen, with black Africans at a lower level, and Australian Aborigines lower still. He did not specifically study Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, but remarked that "they appear to be rich in families of high intellectual breeds".

Meanwhile, the American abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

and escaped slave Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

had gained fame for his oratory and incisive writings, despite having learned to read as a child largely through surreptitious observation. Accordingly, he had been described by abolitionists as a living counter-example to slaveholders' arguments that people of African descent lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens.Stewart, Roderick M. 1999. "The Claims of Frederick Douglass Philosophically Considered." Pp. 155–56 in ''Frederick Douglass: A Critical Reader'', edited by B. E. Lawson and F. M. Kirkland. Wiley-Blackwell. . "Moreover, though he does not make the point explicitly, again the very fact that Douglass is ably disputing this argument on this occasion celebrating a select few's intellect and will (or moral character)—this fact constitutes a living counterexample to the narrowness of the pro-slavery definition of humans." His eloquence was so notable that some found it hard to believe he had once been a slave.Matlack, James. 1979. "The Autobiographies of Frederick Douglass." ''Phylon (1960–)'' 40(1):15–28. . . p. 16: "He spoke too well.… Since he did not talk, look, or act like a slave (in the eyes of Northern audiences), Douglass was denounced as an imposter." In the later years of his life, one newspaper described him as "a bright example of the capability of the colored race, even under the blighting influence of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, from which he emerged and became one of the distinguished citizens of the country."

Other abolitionists of the 19th century continued to advance the theme of ancient Egypt as a black civilization as an argument against racism. On this basis, scholar and diplomat Alexander Hill Everett

Alexander Hill Everett (March 19, 1792 – June 28, 1847) was an American diplomat, politician, and Boston man of letters. Everett held diplomatic posts in the Netherlands, Spain, Cuba, and China. His translations of European literature, publish ...

argued in his 1927 book ''America'': "With regard to the intellectual capabilities of the African race, it may be observed that Africa was once the nursery of science and literature, and it was from thence that they were disseminated among the Greeks and Romans." Similarly, the philosopher John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

posited in his 1849 essay "On the Negro Question" that "it was from Negroes, therefore, that the Greeks learnt their first lessons in civilization."

In 1895, R. Meade Bache of the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

published an article in ''Psychological Review

''Psychological Review'' is a bimonthly peer-reviewed academic journal that covers psychological theory. It was established by James Mark Baldwin (Princeton University) and James McKeen Cattell (Columbia University) in 1894 as a publication vehic ...

'' claiming that reaction time increases with evolution. Bache supported this claim with data showing slower reaction times among White Americans when compared with those of Native Americans and African Americans, with Native Americans having the quickest reaction time. He hypothesized that the slow reaction time of White Americans was to be explained by their possessing more contemplative brains which did not function well on tasks requiring automatic responses. This was one of the first examples of modern scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

, in which a veneer of science was used to bolster belief in the superiority of a particular race.

1900–1920

In 1903, the pioneering African-American sociologistW. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

published his landmark collection of essays ''The Souls of Black Folk

''The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches'' is a 1903 work of American literature by W. E. B. Du Bois. It is a seminal work in the history of sociology and a cornerstone of African-American literature.

The book contains several essays on ...

'' in defense of the inherent mental capacity and equal humanity of black people. According to Manning Marable

William Manning Marable (May 13, 1950 – April 1, 2011) was an American professor of public affairs, history and African-American Studies at Columbia University. Marable founded and directed the Institute for Research in African-American Studi ...

, this book "helped to create the intellectual argument for the black freedom struggle in the twentieth century. 'Souls' justified the pursuit of higher education for Negroes and thus contributed to the rise of the black middle class

The African-American middle class consists of African-Americans who have middle-class status within the American class structure. It is a societal level within the African-American community that primarily began to develop in the early 1960s, ...

." In contrast to other civil rights leaders like Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, and orator. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the primary leader in the African-American community and of the contemporary Black elite#United S ...

, who advocated for incremental progress and vocational education as a way for black Americans to demonstrate the virtues of "industry, thrift, intelligence and property" to the white majority, Du Bois advocated for black schools to focus more on liberal arts

Liberal arts education () is a traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term ''skill, art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically the fine arts. ''Liberal arts education'' can refe ...

and academic curriculum (including the classics, arts, and humanities), because liberal arts were required to develop a leadership elite. Du Bois argued that black populations just as much as white ones naturally give rise to what he termed a "talented tenth

The talented tenth is a term that designated a leadership class of African Americans in the early 20th century. Although the term was created by white Northern philanthropists, it is primarily associated with W. E. B. Du Bois, who used it as the ...

" of intellectually gifted individuals.

At the same time, the discourse of scientific racism was accelerating. In 1910 the sociologist Howard W. Odum

Howard Washington Odum (May 24, 1884 – November 8, 1954) was a white American sociologist and author who researched African-American life and folklore. Beginning in 1920, he served as a faculty member at the University of North Carolina, foun ...

published his book ''Mental and Social Traits of the Negro'', which described African-American students as "lacking in filial affection, strong migratory instincts, and tendencies; little sense of veneration, integrity or honor; shiftless, indolent, untidy, improvident, extravagant, lazy, lacking in persistence and initiative and unwilling to work continuously at details. Indeed, experience with the Negro in classrooms indicates that it is impossible to get the child to do anything with continued accuracy, and similarly in industrial pursuits, the Negro shows a woeful lack of power of sustained activity and constructive conduct." As the historian of psychology Ludy T. Benjamin explains, "with such prejudicial beliefs masquerading as facts," it was at this time that educational segregation on the basis of race was imposed in some states. The first practical intelligence test was developed between 1905 and 1908 by

The first practical intelligence test was developed between 1905 and 1908 by Alfred Binet

Alfred Binet (; ; 8 July 1857 – 18 October 1911), born Alfredo Binetti, was a French psychologist who together with Théodore Simon invented the first practical intelligence test, the Binet–Simon test. In 1904, Binet took part in a comm ...

in France for school placement of children. Binet warned that results from his test should not be assumed to measure innate intelligence or used to label individuals permanently. In 1916 Binet's test was translated into English and revised by Lewis Terman

Lewis Madison Terman (January 15, 1877 – December 21, 1956) was an American psychologist, academic, and proponent of eugenics. He was noted as a pioneer in educational psychology in the early 20th century at the Stanford School of Education. T ...

(who introduced IQ scoring for the test results) and published under the name Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales

The Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales (or more commonly the Stanford–Binet) is an individually administered intelligence test that was revised from the original Binet–Simon Scale by Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon. It is in its fifth e ...

. Terman wrote that Mexican-Americans, African-Americans, and Native Americans have a mental "dullness hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

seems to be racial, or at least inherent in the family stocks from which they come." He also argued for a higher frequency of so-called " morons" among non-white American racial groups, and concluded that there were "enormously significant racial differences in general intelligence" which could not be remedied by education.

In 1916 a team of psychologists, led by Robert Yerkes

Robert Mearns Yerkes (; May 26, 1876 – February 3, 1956) was an American psychologist, ethologist, eugenicist and primatologist best known for his work in intelligence testing and in the field of comparative psychology.

Yerkes was a pionee ...

and including Terman and Henry H. Goddard

Henry Herbert Goddard (August 14, 1866 – June 18, 1957) was an American psychologist, eugenicist, and segregationist during the early 20th century. He is known especially for his 1912 work '' The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Fe ...

, adapted the Stanford-Binet tests as multiple-choice group tests for use by the US army. In 1919, Yerkes devised a version of this test for civilians, the National Intelligence Test, which was used in all levels of education and in business. Like Terman, Goddard had argued in his book, ''Feeble-mindedness: Its Causes and Consequences'' (1914), that "feeble-mindedness

The term feeble-minded was used from the late 19th century in Europe, the United States, and Australasia for disorders later referred to as illnesses, deficiencies of the mind, and disabilities.

At the time, ''mental deficiency'' encompassed al ...

" was hereditary; and in 1920 Yerkes in his book with Yoakum on the ''Army Mental Tests'' described how they "were originally intended, and are now definitely known, to measure native intellectual ability". Both Goddard and Terman argued that the feeble-minded should not be allowed to reproduce. In the US, however, independently and prior to the IQ tests, there had been political pressure for such eugenic

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the ferti ...

policies to be enforced by sterilization

Sterilization may refer to:

* Sterilization (microbiology), killing or inactivation of micro-organisms

* Soil steam sterilization, a farming technique that sterilizes soil with steam in open fields or greenhouses

* Sterilization (medicine) render ...

; in due course, IQ tests were later used as justification for sterilizing the mentally retarded.

Early IQ tests were also used to argue for limits to immigration to the US. Already in 1917, Goddard reported on the low IQ scores of new arrivals at Ellis Island

Ellis Island is an island in New York Harbor, within the U.S. states of New Jersey and New York (state), New York. Owned by the U.S. government, Ellis Island was once the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United State ...

. Yerkes argued on the basis of his army test scores that there were consistently lower IQ levels among those from Southern and Eastern Europe, which he suggested could lead to a decline in the average IQ of Americans if immigration from these regions were not limited.

1920–1960

In the 1920s, psychologists started questioning underlying assumptions of racial differences in intelligence; although not discounting them, the possibility was considered that they were on a smaller scale than previously supposed and also due to factors other than heredity. In 1924,Floyd Allport

Floyd Henry Allport (August 22, 1890 – October 15, 1979) was an American psychologist who is often considered "the father of experimental social psychology", having played a key role in the creation of social psychology as a legitimate field of ...

wrote in his book ''Social Psychology'' that the French sociologist Gustave Le Bon

Charles-Marie Gustave Le Bon (7 May 1841 – 13 December 1931) was a leading French polymath whose areas of interest included anthropology, psychology, sociology, medicine, invention, and physics. He is best known for his 1895 work '' The Crowd: ...

was incorrect in asserting "a gap between inferior and superior species", and pointed to "social inheritance" and "environmental factors" as accounting for differences. Nevertheless, he suggested that: "the intelligence of the white race is of a more versatile and complex order than that of the black race. It is probably superior to that of the red or yellow races."

In 1923, in his book ''A study of American intelligence'', Carl Brigham wrote that on the basis of the Yerkes army tests: "The decline in intelligence is due to two factors, the change in races migrating to this country, and to the additional factor of sending lower and lower representatives of each race." He concluded that: "The steps that should be taken to preserve or increase our present mental capacity must, of course, be dictated by science and not by political expediency. Immigration should not only be restrictive, but highly selective." The Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from every count ...

put these recommendations into practice, introducing quotas based on the 1890 census, prior to the waves of immigration from Poland and Italy. While Gould and Kamin argued that the psychometric claims of Nordic superiority had a profound influence on the institutionalization of the 1924 immigration law, other scholars have argued that "the eventual passage of the 'racist' immigration law of 1924 was not crucially affected by the contributions of Yerkes or other psychologists".

In 1929, Robert Woodworth, in his textbook ''Psychology: A Study of Mental Life'', made no claims about innate differences in intelligence between races, pointing instead to environmental and cultural factors. He considered it advisable to "suspend judgment and keep our eyes open from year to year for fresh and more conclusive evidence that will probably be discovered". In the 1930s, the English psychologist

In the 1930s, the English psychologist Raymond Cattell

Raymond Bernard Cattell (20 March 1905 – 2 February 1998) was a British-American psychologist, known for his psychometric research into intrapersonal psychological structure.Gillis, J. (2014). ''Psychology's Secret Genius: The Lives and Works ...

wrote three tracts, ''Psychology and Social Progress'' (1933), ''The Fight for Our National Intelligence'' (1937) and ''Psychology and the Religious Quest'' (1938). The second was published by the Eugenics Society

The Adelphi Genetics Forum is a non-profit learned society based in the United Kingdom. Its aims are "to promote the public understanding of human heredity and to facilitate informed debate about the ethical issues raised by advances in reproducti ...

, of which he had been a research fellow; it predicted the disastrous consequences of not stopping the decline in the average intelligence in Britain by one point per decade. In 1933, Cattell wrote that, of all the European races, the "Nordic race was the most evolved in intelligence and stability of temperament". He argued for "no mixture of bloods between racial groups" because "the resulting re-shuffling of impulses and psychic units throws together in each individual a number of forces which may be incompatible". He rationalised the "hatred and abhorrence ... for the Jewish practice of living in other nations instead of forming an independent self-sustained group of their own", referring to them as "intruders" with a "crafty spirit of calculation". He recommended a rigid division of races, referring to those suggesting that individuals be judged on their merits, irrespective of racial background, as "race-slumpers". He wrote that in the past, "the backward branches of the tree of mankind" had been lopped off as "the American Indians, the Black Australians, the Mauris and the negroes had been driven by bloodshed from their lands", unaware of "the biological rationality of that destiny". He advocated what he saw as a more enlightened solution: by birth control, by sterilization, and by "life in adapted reserves and asylums", where the "races which have served their turn houldbe brought to euthanasia." He considered blacks to be naturally inferior, on account of their supposedly "small skull capacity". In 1937, he praised the Third Reich

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

for their eugenic laws and for "being the first to adopt sterilization together with a policy of racial improvement". In 1938, after newspapers had reported on the segregation of Jews into ghettos and concentration camps, he commented that the rise of Germany "should be welcomed by the religious man as reassuring evidence that in spite of modern wealth and ease, we shall not be allowed ... to adopt foolish social practices in fatal detachment from the stream of evolution". In late 1937, Cattell moved to the US on the invitation of the psychologist Edward Thorndike

Edward Lee Thorndike ( – ) was an American psychologist who spent nearly his entire career at Teachers College, Columbia University. His work on comparative psychology and the learning process led to his " theory of connectionism" and helped ...

of Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

, also involved in eugenics. He spent the rest of his life there as a research psychologist, devoting himself after retirement to devising and publicising a refined version of his ideology from the 1930s that he called ''beyondism''.  In 1935,

In 1935, Otto Klineberg

Otto Klineberg (2 November 1899, in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada – 6 March 1992, in Bethesda, Maryland) was a Canadian born psychologist.

He held professorships in social psychology at Columbia University and the University of Paris. His pioneer ...

wrote two books, ''Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration'' and ''Race Differences'', dismissing claims that African Americans in the northern states were more intelligent than those in the south. He argued that there was no scientific proof of racial differences in intelligence and that this should not therefore be used as a justification for policies in education or employment.

The hereditarian view began to change in the 1920s in reaction to excessive eugenicist claims regarding abilities and moral character, and also due to the development of convincing environmental arguments. In the 1940s many psychologists, particularly social psychologists, began to argue that environmental and cultural factors, as well as discrimination and prejudice, provided a more probable explanation of disparities in intelligence. According to Franz Samelson

Franz Samelson (September 23, 1923 – March 16, 2015) was a German-American social psychologist and historian of psychology.

Samelson was born on September 23, 1923, in Breslau, German Reich (today Wrocław, Poland). Prohibited by the laws of N ...

, this change in attitude had become widespread by then, with very few studies in race differences in intelligence, a change brought out by an increase in the number of psychologists not from a "lily-white ... Anglo-Saxon" background but from Jewish backgrounds. Other factors that influenced American psychologists were the economic changes brought about by the depression and the reluctance of psychologists to risk being associated with the Nazi claims of a master race. The 1950 race statement of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

, prepared in consultation with scientists including Klineberg, created a further taboo

A taboo is a social group's ban, prohibition or avoidance of something (usually an utterance or behavior) based on the group's sense that it is excessively repulsive, offensive, sacred or allowed only for certain people.''Encyclopædia Britannica ...

against conducting scientific research on issues related to race. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

banned IQ testing for being "Jewish" as did Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

for being "bourgeois".

1960–1980

In 1965William Shockley

William Bradford Shockley ( ; February 13, 1910 – August 12, 1989) was an American solid-state physicist, electrical engineer, and inventor. He was the manager of a research group at Bell Labs that included John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brat ...

, Nobel laureate in physics and professor at Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

, made a public statement at the Nobel conference on "Genetics and the Future of Man" about the problems of "genetic deterioration" in humans caused by "evolution in reverse". He claimed social support systems designed to help the disadvantaged had a regressive effect. Shockley subsequently claimed the most competent American population group were the descendants of original European settlers, because of the extreme selective pressures imposed by the harsh conditions of early colonialism. Speaking of the "genetic enslavement" of African Americans, owing to an abnormally high birth rate, Shockley discouraged improved education as a remedy, suggesting instead sterilization and birth control. In the following ten years he continued to argue in favor of this position, claiming it was not based on prejudice but "on sound statistics". Shockley's outspoken public statements and lobbying brought him into contact with those running the Pioneer Fund

The Pioneer Fund is an American non-profit foundation established in 1937 "to advance the scientific study of heredity and human differences". The organization has been described as racist and white supremacist in nature. The Southern Pover ...

who subsequently, through the intermediary Carleton Putnam

Carleton Putnam (December 19, 1901 – March 5, 1998) was an American businessman, writer and advocate for racial segregation. He graduated from Princeton University in 1924 and received a Bachelor of Laws (LL.B.) from Columbia Law School in 1932 ...

, provided financial support for his extensive lobbying activities in this area, reported widely in the press. With the psychologist and segregationist

Racial segregation is the separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, such as schools and hospitals by peopl ...

R. Travis Osborne as adviser, he formed the Foundation for Research and Education on Eugenics and Dysgenics (FREED). Although its stated purpose was "solely for scientific and educational purposes related to human population and quality problems", FREED mostly acted as a lobbying agency for spreading Shockley's ideas on eugenics.

The

The Pioneer Fund

The Pioneer Fund is an American non-profit foundation established in 1937 "to advance the scientific study of heredity and human differences". The organization has been described as racist and white supremacist in nature. The Southern Pover ...

had been set up by Wickliffe Draper

Wickliffe Preston Draper (August 9, 1891 – March 11, 1972) was an American political activist. He was an ardent eugenicist and lifelong advocate of strict racial segregation. In 1937, he founded the Pioneer Fund for eugenics and heredity rese ...

in 1937 with one of its two charitable purposes being to provide aid for "study and research into the problems of heredity and eugenics in the human race" and "into the problems of race betterment with special reference to the people of the United States". From the late fifties onwards, following the 1954 Supreme Court decision on segregation in schools, it supported psychologists and other scientists in favour of segregation. All of these ultimately held academic positions in the Southern states, notably Henry E. Garrett (head of psychology at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

until 1955), Wesley Critz George, Frank C.J. McGurk

Frank C. J. McGurk (1910–1995) was an American psychologist who was noted for his claims about race and intelligence. McGurk taught at Lehigh University, Villanova University, West Point, and Alabama College.Winston AScience in the service of ...

, R. Travis Osborne and Audrey Shuey, who in 1958 wrote ''The Testing of Negro Intelligence'', demonstrating "the presence of native differences between Negroes and whites as determined by intelligence tests". In 1959 Garrett helped to found the International Association for the Advancement of Ethnology and Eugenics

The International Association for the Advancement of Ethnology and Eugenics (IAAEE) was an organisation that promoted eugenics and segregation, and the first publisher of ''Mankind Quarterly''.

History

IAAEE was founded in 1959 and has headquart ...

, an organisation promoting segregation. In 1961 he blamed the shift away from hereditarianism, which he described as the "scientific hoax of the century", on the school of thought –the "Boas cult" – promoted by his former colleagues at Columbia, notably Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the mov ...

and Otto Klineberg

Otto Klineberg (2 November 1899, in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada – 6 March 1992, in Bethesda, Maryland) was a Canadian born psychologist.

He held professorships in social psychology at Columbia University and the University of Paris. His pioneer ...

, and more generally "Jewish organizations", most of whom "belligerently support the egalitarian dogma which they accept as having been 'scientifically' proved". He also pointed to Marxist origins in this shift, writing in a pamphlet, ''Desegregation: Fact and hokum'', that: "It is certain that the Communists have aided in the acceptance and spread of egalitarianism although the extent and method of their help is difficult to assess. Egalitarianism is good Marxist doctrine, not likely to change with gyrations in the Kremlin line." In 1951 Garrett had even gone as far as reporting Klineberg to the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

for advocating "many Communistic theories", including the idea that "there are no differences in the races of mankind".

One of Shockley's lobbying campaigns involved the educational psychologist

An educational psychologist is a psychologist whose differentiating functions may include diagnostic and psycho-educational assessment, psychological counseling in educational communities ( students, teachers, parents, and academic authorit ...

, Arthur Jensen

Arthur Robert Jensen (August 24, 1923 – October 22, 2012) was an American psychologist and writer. He was a professor of educational psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. Jensen was known for his work in psychometrics an ...

, of the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

(UC Berkeley). Although earlier in his career Jensen had favored environmental rather than genetic factors as the explanation of race differences in intelligence, he had changed his mind during 1966-1967 when he was at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences

The Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) is an interdisciplinary research institution at Stanford University designed to advance the frontiers of knowledge about human behavior and society, and contribute to the resoluti ...

at Stanford. Here Jensen met Shockley and through him received support for his research from the Pioneer Fund. Although Shockley and Jensen's names were later to become linked in the media, Jensen does not mention Shockley as an important influence on his thought in his subsequent writings; rather he describes as decisive his work with Hans Eysenck

Hans Jürgen Eysenck ( ; 4 March 1916 – 4 September 1997) was a German-born British psychologist. He is best remembered for his work on intelligence and personality psychology, personality, although he worked on other issues in psychology. At t ...

. He also mentions his interest in the behaviorist

Behaviorism is a systematic approach to understand the behavior of humans and other animals. It assumes that behavior is either a reflex elicited by the pairing of certain antecedent stimuli in the environment, or a consequence of that indivi ...

theories of Clark L. Hull which he says he abandoned largely because he found them to be incompatible with experimental findings during his years at Berkeley.

In a 1968 article published in ''Disadvantaged Child'', Jensen questioned the effectiveness of child development and antipoverty programs, writing: "As a social policy, avoidance of the issue could be harmful to everyone in the long run, especially to future generations of Negroes, who could suffer the most from well-meaning but misguided and ineffective attempts to improve their lot." In 1969 Jensen wrote a long article in the

In a 1968 article published in ''Disadvantaged Child'', Jensen questioned the effectiveness of child development and antipoverty programs, writing: "As a social policy, avoidance of the issue could be harmful to everyone in the long run, especially to future generations of Negroes, who could suffer the most from well-meaning but misguided and ineffective attempts to improve their lot." In 1969 Jensen wrote a long article in the Harvard Educational Review

The ''Harvard Educational Review'' is an academic journal of opinion and research dealing with education, associated with the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and published by the Harvard Education Publishing Group. The journal was established ...

, " How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?"

In his article, 123 pages long, Jensen insisted on the accuracy and lack of bias in intelligence tests, stating that the absolute quantity ''g'' that they measured, the general intelligence factor

The ''g'' factor is a construct developed in psychometric investigations of cognitive abilities and human intelligence. It is a variable that summarizes positive correlations among different cognitive tasks, reflecting the assertion that an ind ...

, first introduced by the English psychologist Charles Spearman

Charles Edward Spearman, FRS (10 September 1863 – 17 September 1945) was an English psychologist known for work in statistics, as a pioneer of factor analysis, and for Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. He also did seminal work on mod ...

in 1904, "stood like a Rock of Gibraltar in psychometrics". He stressed the importance of biological considerations in intelligence, commenting that "the belief in the almost infinite plasticity of intellect, the ostrich-like denial of biological factors in individual differences, and the slighting of the role of genetics in the study of intelligence can only hinder investigation and understanding of the conditions, processes, and limits through which the social environment influences human behavior." He argued at length that, contrary to environmentalist orthodoxy, intelligence was partly dependent on the same genetic factors that influence other physical attributes. More controversially, he briefly speculated that the difference in performance at school between blacks and whites might have a partly genetic explanation, commenting that there were "various lines of evidence, no one of which is definitive alone, but which, viewed all together, make it a not unreasonable hypothesis that genetic factors are strongly implicated in the average Negro-white

intelligence difference. The preponderance of the evidence is, in my opinion, less consistent with a strictly environmental hypothesis than with a genetic hypothesis, which, of course, does not exclude the influence of environment or its interaction with genetic factors." He advocated the allocation of educational resources according to merit and insisted on the close correlation between intelligence and occupational status, arguing that "in a society that values and rewards individual talent and merit, genetic factors inevitably take on considerable importance." Concerned that the average IQ in the US was inadequate to answer the increasing needs of an industrialised society, he predicted that people with lower IQs would become unemployable while at the same time there would be an insufficient number with higher IQs to fill professional posts. He felt that eugenic reform would prevent this more effectively than compensatory education, surmising that "the technique for raising intelligence ''per se'' in the sense of ''g'', probably lie more in the province of biological science than in psychology or education". He pointed out that intelligence and family size were inversely correlated, particularly amongst the black population, so that the current trend in average national intelligence was dysgenic

Dysgenics refers to any decrease in the prevalence of traits deemed to be either socially desirable or generally adaptive to their environment due to selective pressure disfavouring their reproduction.

In 1915 the term was used by David Starr J ...

rather than eugenic. As he wrote, "Is there a danger that current welfare policies, unaided by eugenic foresight, could lead to the genetic enslavement of a substantial segment of our population? The fuller consequences of our failure seriously to study these questions may well be judged by future generations as our society's greatest injustice to Negro Americans." He concluded by emphasizing the importance of child-centered education. Although a tradition had developed for the exclusive use of cognitive learning in schools, Jensen argued that it was not suited to "these children's genetic and cultural heritage": although capable of associative learning and memorization ("Level I" ability), they had difficulties with abstract conceptual reasoning ("Level II" ability). He felt that in these circumstances the success of education depended on exploiting "the actual potential learning that is latent in these children's patterns of abilities". He suggested that, in order to ensure equality of opportunity, "schools and society must provide a range and diversity of educational methods, programs and goals, and of occupational opportunities, just as wide as the range of human abilities."

Later, writing about how the article came into being, Jensen said that the editors of the Review had specifically asked him to include his view on the heritability of race differences, which he had not previously published. He also maintains that only five percent of the article touched on the topic of race difference in IQ. also gave a detailed account of how the student editors of ''Harvard Educational Review'' commissioned and negotiated the content of Jensen's article.

Many academics have given commentaries on what they considered to be the main points of Jensen's article and the subsequent books in the early 1970s that expanded on its content. According to , in his article Jensen had argued "that educational programs for disadvantaged children initiated as the War on Poverty had failed, and the black-white race gap probably had a substantial genetic component." They summarised Jensen's argument as follows:

# "Most of the variation in black-white scores is genetic"

# "No one has advanced a plausible environmental explanation for the black-white gap"

# "Therefore it is more reasonable to assume that part of the black-white gap is genetic in origin"

According to , Jensen's article defended 3 claims:

# IQ tests

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardized tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence. Originally, IQ was a score obtained by dividing a person's mental age score, obtained by administering ...

provide accurate measurements of a real human ability that is relevant in many aspects of life.

# Intelligence, as measured by IQ tests, is highly (about 80%) heritable

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of Phenotypic trait, traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cell (biology), cells or orga ...

and parents with low IQs are much more likely to have children with low IQs

# Educational programs have been unable to significantly change the intelligence of individuals or groups.

According to , the article claimed "a correlation between intelligence, measured by IQ tests, and racial genes". He wrote that Jensen, based on empirical evidence, had concluded that "black intelligence was congenitally inferior to that of whites"; that "this partly explains unequal educational achievements"; and that, "because a certain level of underachievement was due to the inferior genetic attributes of blacks, compensatory and enrichment programs are bound to be ineffective in closing the racial gap in educational achievements." Several commentators mention Jensen's recommendations for schooling: according to Barry Nurcombe,

Jensen had already suggested in the article that initiatives like the Head Start Program

Head Start is a program of the United States Department of Health and Human Services that provides comprehensive early childhood education, health, nutrition, and parent involvement services to low-income children and families. It is the olde ...

were ineffective, writing in the opening sentence, "Compensatory education has been tried and it apparently has failed." Other experts in psychometrics

Psychometrics is a field of study within psychology concerned with the theory and technique of measurement. Psychometrics generally covers specialized fields within psychology and education devoted to testing, measurement, assessment, and rela ...

, such as and , have given accounts of Jensen's theory of Level I and Level II abilities, which originated in this and earlier articles. As the historian of psychology William H. Tucker William Tucker may refer to:

* William Tooker or Tucker (1557/58–1621), English churchman

* William Tucker (musician) (1961–1999), guitar player

* William Tucker (politician) (1843–1919), member of the New Zealand Legislative Council

* Wi ...

commented, Jensen's question is leading: "Is there a danger that current welfare policies, unaided by eugenic foresight, could lead to the genetic enslavement of a substantial segment of our population? The fuller consequences of our failure seriously to study these questions may well be judged by future generations as our society's greatest injustice to Negro Americans". Tucker noted that it repeats Shockley's phrase "genetic enslavement", which proved later to be one of the most inflammatory statements in the article.

Shockley conducted a widespread publicity campaign for Jensen's article, supported by the Pioneer Fund. Jensen's views became widely known in many spheres. As a result, there was renewed academic interest in the hereditarian viewpoint and in intelligence tests. Jensen's original article was widely circulated and often cited; the material was taught in university courses over a range of academic disciplines. In response to his critics, Jensen wrote a series of books on all aspects of psychometrics. There was also a widespread positive response from the popular press — with ''The New York Times Magazine

''The New York Times Magazine'' is an American Sunday magazine included with the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times''. It features articles longer than those typically in the newspaper and has attracted many notable contributors. The magazi ...

'' dubbing the topic " Jensenism" — and amongst politicians and policy makers.

In 1971 Richard Herrnstein

Richard Julius Herrnstein (May 20, 1930 – September 13, 1994) was an American psychologist at Harvard University. He was an active researcher in animal learning in the Skinnerian tradition. Herrnstein was the Edgar Pierce Professor of Psycho ...

wrote a long article on intelligence tests in The Atlantic

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher based in Washington, D.C. It features articles on politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 185 ...

for a general readership. Undecided on the issues of race and intelligence, he discussed instead score differences between social classes. Like Jensen he took a firmly hereditarian point of view. He also commented that the policy of equal opportunity would result in making social classes more rigid, separated by biological differences, resulting in a downward trend in average intelligence that would conflict with the growing needs of a technological society.

Jensen and Herrnstein's articles were widely discussed.

Jensen and Herrnstein's articles were widely discussed. Hans Eysenck

Hans Jürgen Eysenck ( ; 4 March 1916 – 4 September 1997) was a German-born British psychologist. He is best remembered for his work on intelligence and personality psychology, personality, although he worked on other issues in psychology. At t ...

defended the hereditarian point of view and the use of intelligence tests in "Race, Intelligence and Education" (1971), a pamphlet presenting Jensenism to a popular audience, and "The Inequality of Man" (1973). He was severely critical of anti-hereditarians whose policies he blamed for many of the problems in society. In the first book he wrote that, "All the evidence to date suggests the strong and indeed overwhelming importance of genetic factors in producing the great variety of intellectual differences which reobserved between certain racial groups", adding in the second, that "for anyone wishing to perpetuate class or caste differences, genetics is the real foe". "Race, Intelligence and Education" was immediately criticized in strong terms by IQ researcher Sandra Scarr

Sandra Wood Scarr (August 8, 1936 – October 8, 2021) was an American psychologist and writer. She was the first female full professor in psychology in the history of Yale University. She established core resources for the study of development, ...

as an "uncritical popularization of Jensen's ideas without the nuances and qualifiers that make much of Jensen's writing credible or at least responsible." article previously published in ''Science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

'', 1971, ''174'', 1223–1228. Later scholars have identified errors and suspected data manipulation in Eysenck's work. An inquiry on behalf of King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

found 26 of his papers to be "incompatible with modern clinical science". Rod Buchanan, a biographer of Eysenck, has argued that 87 publications by Eysenck should be retracted.

Student groups and faculty at Berkeley and Harvard protested Jensen and Herrnstein with charges of racism. Two weeks after the appearance of Jensen's article, Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s and was one of the principal representations of the New Left. Disdaining permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships a ...

staged protests against Arthur Jensen on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, chanting "Fight racism. Fire Jensen!" Jensen himself states that he even lost his employment at Berkeley because of the controversy. Similar campaigns were waged in London against Eysenck and in Boston against sociobiologist

Sociobiology is a field of biology that aims to explain social behavior in terms of evolution. It draws from disciplines including psychology, ethology, anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics. Within the study of ...

Edward Wilson. The attacks on Wilson were orchestrated by the Sociobiology Study Group The Sociobiology Study Group was an academic organization formed to specifically counter sociobiological explanations of human behavior, particularly those expounded by the Harvard entomologist E. O. Wilson in '' Sociobiology: The New Synthesis'' ( ...

, part of the left wing organization Science for the People

Science for the People (SftP) is an organization that emerged from the Peace movement, antiwar culture of the United States in the late 1960s. Since 2014 it has experienced a revival focusing primarily on the dual nature of science. The organizat ...

, formed of 35 scientists and students, including the Harvard biologists Stephen J. Gould and Richard Lewontin

Richard Charles Lewontin (March 29, 1929 – July 4, 2021) was an American evolutionary biologist, mathematician, geneticist, and social commentator. A leader in developing the mathematical basis of population genetics and evolutionary theory, ...

, who both became prominent critics of hereditarian research in race and intelligence. In 1972 50 academics, including the psychologists Jensen, Eysenck, and Herrnstein as well as five Nobel laureates, signed a statement entitled "Resolution on Scientific Freedom Regarding Human Behavior and Heredity", criticizing the climate of "suppression, punishment and defamation of scientists who emphasized the role of heredity in human behavior". In October 1973 a half-page advertisement entitled "Resolution Against Racism" appeared in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

''. With over 1000 academic signatories, including Lewontin, it condemned "racist research", denouncing in particular Jensen, Shockley and Herrnstein.

This was accompanied by commentaries, criticisms and denouncements from the academic community. Two issues of the Harvard Educational Review

The ''Harvard Educational Review'' is an academic journal of opinion and research dealing with education, associated with the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and published by the Harvard Education Publishing Group. The journal was established ...

were devoted to critiques of Jensen's work by psychologists, biologists and educationalists. As documented by , the main commentaries involved: population genetics

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and among populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as Adaptation (biology), adaptation, s ...

(Richard Lewontin, Luigi Cavalli-Sforza

Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza (; 25 January 1922 – 31 August 2018) was an Italian geneticist. He was a population geneticist who taught at the University of Parma, the University of Pavia and then at Stanford University.

Works

Schooling and po ...

, Walter Bodmer); the heritability of intelligence

Research on the heritability of intelligence quotient (IQ) inquires into the degree of variation in IQ within a population that is due to genetic variation between individuals in that population. There has been significant controversy in the academ ...

(Christopher Jencks

Christopher Sandy Jencks (October 22, 1936 – February 8, 2025) was an American social scientist.

Background

Born in Baltimore on October 22, 1936, he graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire in 1954 and was president of the sch ...

, Mary Jo Bane

Mary Jo Bane is an American political scientist who focuses on children and welfare. She is currently the Thornton Bradshaw Professor at Harvard Kennedy School, and formerly the Malcolm Wiener Professor of Social Policy and Director of the Malco ...

, Leon Kamin

Leon J. Kamin (December 29, 1927 – December 22, 2017) was an American psychologist known for his contributions to learning theory and his critique of estimates of the heritability of IQ. He studied under Richard Solomon (psychologist), Richard S ...

, David Layzer

David Raymond Layzer (December 31, 1925 – August 16, 2019) was an American astrophysicist, cosmologist, and the Donald H. Menzel Professor Emeritus of Astronomy at Harvard University.

He is known for his cosmological theory of the expansion of ...

); the possible inaccuracy of IQ tests as measures of intelligence (summarised in ); and sociological assumptions about the relationship between intelligence and income (Jencks and Bane). More specifically, the Harvard biologist Richard Lewontin commented on Jensen's use of population genetics, writing that, "The fundamental error of Jensen's argument is to confuse heritability of character within a population with heritability between two populations." Jensen denied making such a claim, saying that his argument was that high within-group heritability increased the probability of non-zero between-group heritability. The political scientists Christopher Jencks and Mary Jo Bane, also from Harvard, recalculated the heritability of intelligence as 45% instead of Jensen's estimate of 80%; and they calculated that only about 12% of variation in income was due to IQ, so that in their view the connections between IQ and occupation were less clear than Jensen had suggested.

Ideological differences also emerged in the controversy. The circle of scientists around Lewontin and Gould rejected the research of Jensen and Herrnstein as "bad science". While not objecting to research into intelligence ''per se'', they felt that this research was politically motivated and objected to the reification of intelligence: the treatment of the numerical quantity ''g'' as a physical attribute like skin color that could be meaningfully averaged over a population group. They claimed that this was contrary to the scientific method, which required explanations at a molecular level, rather than the analysis of a statistical artifact in terms of undiscovered processes in biology or genetics. In response to this criticism, Jensen later wrote: "... what Gould has mistaken for 'reification' is neither more nor less than the common practice in every science of hypothesizing explanatory models to account for the observed relationships within a given domain. Well known examples include the heliocentric theory of planetary motion, the Bohr atom, the electromagnetic field, the kinetic theory of gases, gravitation, quarks, Mendelian genes, mass, velocity, etc. None of these constructs exists as a palpable entity occupying physical space." He asked why psychology should be denied "the common right of every science to the use of hypothetical constructs or any theoretical speculation concerning causal explanations of its observable phenomena".

The academic debate also became entangled with the so-called "Burt Affair", because Jensen's article had partially relied on the 1966

The academic debate also became entangled with the so-called "Burt Affair", because Jensen's article had partially relied on the 1966 twin studies

Twin studies are studies conducted on Identical twin, identical or Fraternal twin, fraternal twins. They aim to reveal the importance of environmental and genetics, genetic influences for traits, phenotypes, and disorders. Twin research is consid ...

of the British educational psychologist Sir Cyril Burt: shortly after Burt's death in 1971, there were allegations, prompted by research of Leon Kamin, that Burt had fabricated parts of his data, charges which have never been fully resolved. Franz Samelson documents how Jensen's views on Burt's work varied over the years: Jensen was Burt's main defender in the US during the 1970s. In 1983, following the publication in 1978 of Leslie Hearnshaw's official biography of Burt, Jensen changed his mind, "fully accept ngas valid ... Hearnshaw's biography" and stating that "of course urt

Urt (; ; )AHURTI

asa cabal of motivated opponents, avidly aided by the mass media, to bash urt'sreputation completely", a view repeated in an invited address on Burt before the Similar charges of a politically motivated campaign to stifle scientific research on racial differences, later dubbed "Neo-

Similar charges of a politically motivated campaign to stifle scientific research on racial differences, later dubbed "Neo-

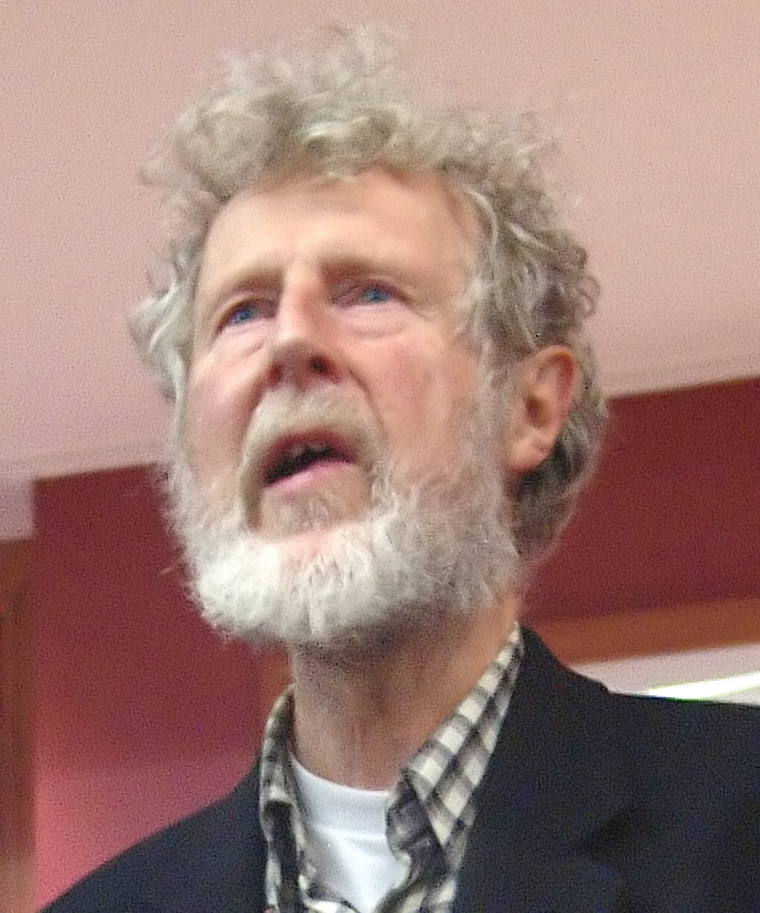

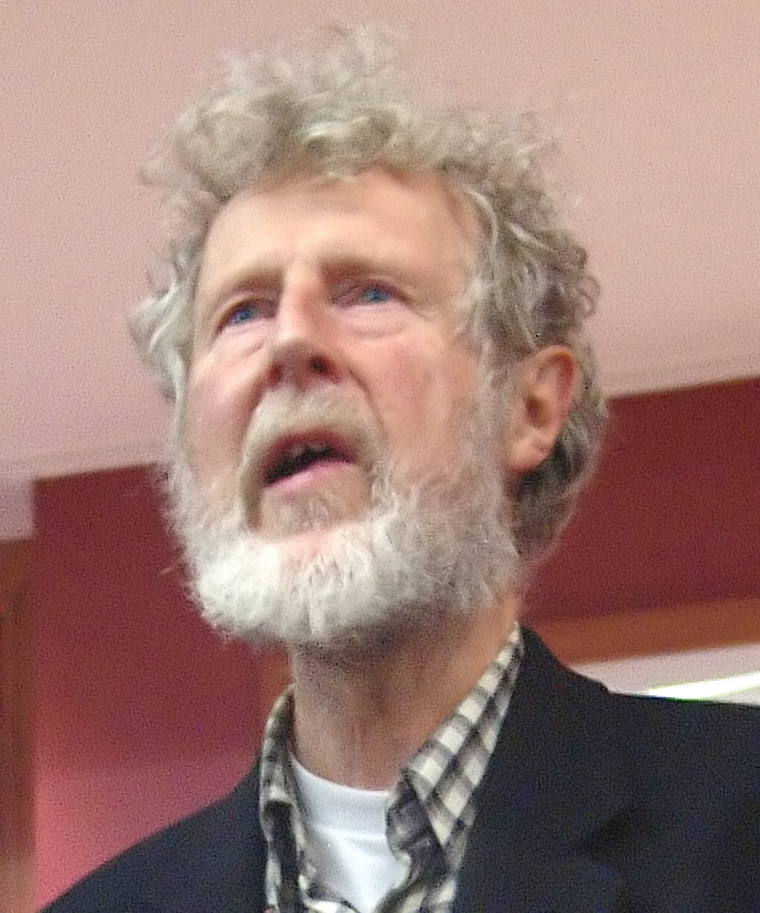

In the 1980s, political scientist James Flynn compared the results of groups who took both older and newer versions of specific IQ tests. His research led him to the discovery of what is now called the

In the 1980s, political scientist James Flynn compared the results of groups who took both older and newer versions of specific IQ tests. His research led him to the discovery of what is now called the  From the 1980s onwards, the Pioneer Fund continued to fund hereditarian research on race and intelligence, in particular the two English-born psychologists

From the 1980s onwards, the Pioneer Fund continued to fund hereditarian research on race and intelligence, in particular the two English-born psychologists

IQ and the wealth of nations

Westport, CT: Praeger. Vanhanen claimed "Whereas the average IQ of Finns is 97, in Africa it is between 60 and 70. Differences in intelligence are the most significant factor in explaining poverty." A complaint by Finland's "Ombudsman for Minorities", Mikko Puumalainen, resulted in Vanhanen being considered to be investigated for incitement of "racial hatred" by the Finnish National Bureau of Investigations. In 2004, the police stated they found no reason to suspect he incited racial hatred and decided not to launch an investigation. Several negative reviews of the book have been published in the scholarly literature. Susan Barnett and

asa cabal of motivated opponents, avidly aided by the mass media, to bash urt'sreputation completely", a view repeated in an invited address on Burt before the

American Psychological Association

The American Psychological Association (APA) is the main professional organization of psychologists in the United States, and the largest psychological association in the world. It has over 170,000 members, including scientists, educators, clin ...

, when he called into question Hearnshaw's scholarship.

Similar charges of a politically motivated campaign to stifle scientific research on racial differences, later dubbed "Neo-

Similar charges of a politically motivated campaign to stifle scientific research on racial differences, later dubbed "Neo-Lysenkoism

Lysenkoism ( ; ) was a political campaign led by the Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko against genetics and science-based agriculture in the mid-20th century, rejecting natural selection in favour of a form of Lamarckism, as well as expanding upon ...

", were frequently repeated by Jensen and his supporters. bemoaned the fact that "a block has been raised because of the obvious implications for the understanding of racial differences in ability and achievement. Serious considerations of whether genetic as well as environmental factors are involved has been taboo in academic circles", adding that: "In the bizarre racist theories of the Nazis and the disastrous Lysenkoism of the Soviet Union under Stalin, we have seen clear examples of what happens when science is corrupted by subservience to political dogma."

After the appearance of his 1969 article, Jensen was later more explicit about racial differences in intelligence, stating in 1973 "that something between one-half and three-fourths of the average IQ differences between American Negroes and whites is attributable to genetic factors." He even speculated that the underlying mechanism was a "biochemical connection between skin pigmentation and intelligence" linked to their joint development in the ectoderm

The ectoderm is one of the three primary germ layers formed in early embryonic development. It is the outermost layer, and is superficial to the mesoderm (the middle layer) and endoderm (the innermost layer). It emerges and originates from the o ...

of the embryo. Although Jensen avoided any personal involvement with segregationists in the US, he did not distance himself from the approaches of journals of the far right in Europe, many of whom viewed his research as justifying their political ends. In an interview with Nation Europa