Pyotr Grigorenko on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

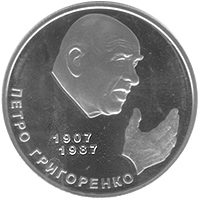

Petro Grigorenko or Petro Hryhorovych Hryhorenko (, – 21 February 1987) was a high-ranking

; Soviet Union

; Ukraine

In

; Soviet Union

; Ukraine

In Kharkiv City Council returned Zhukov Avenue to Hryhorenko Avenue for the third time

LB.ua (24 February 2021)

publicly available unabridged Russian text

*

* *

* * * * * * * * * *

publicly available unabridged Russian text

* * * *

A Chronicle of Current Events (1968-1982): tagged references to Grigorenko (abuse of psychiatry, Crimean Tatar movement, Ukrainian Helsinki Group, expulsion from the USSR, etc.)

General Petro Grigorenko Foundation - English, Russian, Ukrainian

''Pyotr Grigorenko''

International Marxist Group. * (The biography of Grigorenko on the website of the Moscow Helsinki Group) * (The biography of Grigorenko on the website of the Online Library of Alexander Belousenko) * (The biography of Grigorenko on the website of the Andrei Sakharov Museum and Public Center) {{DEFAULTSORT:Grigorenko, Pyotr 1907 births 1987 deaths People from Zaporizhzhia Oblast People from Berdyansky Uyezd Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Soviet major generals Cyberneticists Soviet dissidents Ukrainian dissidents Moscow Helsinki Group Ukrainian Helsinki Group Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes Ukrainian human rights activists Soviet human rights activists Soviet prisoners and detainees Amnesty International prisoners of conscience held by the Soviet Union Denaturalized citizens of the Soviet Union Soviet expellees Soviet emigrants to the United States Soviet psychiatric abuse whistleblowers Psychiatric survivor activists Russian military writers 20th-century Russian memoirists Russian-language writers Ukrainian writers in Russian Stalinism-era scholars and writers Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute alumni Military Engineering-Technical University alumni Academic staff of the Frunze Military Academy Soviet military personnel of World War II from Ukraine Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner Chevaliers of the Order For Courage, 1st class Ukrainian prisoners and detainees Burials at Ukrainian Orthodox Church Cemetery, South Bound Brook

Soviet Army

The Soviet Ground Forces () was the land warfare service branch of the Soviet Armed Forces from 1946 to 1992. It was preceded by the Red Army.

After the Soviet Union ceased to exist in December 1991, the Ground Forces remained under th ...

commander of Ukrainian descent, who in his fifties became a dissident

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 2 ...

and a writer, one of the founders of the human rights movement

Human rights movement refers to a nongovernmental social movement engaged in activism related to the issues of human rights. The foundations of the global human rights movement involve resistance to: colonialism, imperialism, slavery, racism, segre ...

in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

For 16 years, he was a professor of cybernetics

Cybernetics is the transdisciplinary study of circular causal processes such as feedback and recursion, where the effects of a system's actions (its outputs) return as inputs to that system, influencing subsequent action. It is concerned with ...

at the Frunze Military Academy

The M. V. Frunze Military Academy (), or in full the Military Order of Lenin and the October Revolution, Red Banner, Order of Suvorov Academy in the name of M. V. Frunze (), was a military academy of the Soviet and later the Russian Armed Forces ...

and chairman of its cybernetic section before joining the ranks of the early dissidents. In the mid-1970s Grigorenko helped to found the Moscow Helsinki Group

The Moscow Helsinki Group (also known as the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group, ) was one of Russia's leading human rights organisations. It was originally set up in 1976 to monitor Soviet compliance with the Helsinki Accords and to report to the West ...

and the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, before leaving the USSR for medical treatment in the United States. The Soviet government barred his return, and he never again returned to the Soviet Union. In the words of Joseph Alsop, Grigorenko publicly denounced the "totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public s ...

that hides behind the mask of so-called Soviet democracy

Soviet democracy, also called council democracy, is a type of democracy in Marxism, in which the rule of a population is exercised by directly elected '' soviets'' ( workers' councils). Soviets are directly responsible to their electors and boun ...

."

Early life

Petro Grigorenko was born in Borysivka village inTaurida Governorate

Taurida Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit ('' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire. It included the territory of the Crimean Peninsula and the mainland between the lower Dnieper River with the coasts of the Black Sea and Sea o ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

(in present-day

Zaporizhzhia Oblast

Zaporizhzhia Oblast (), commonly referred to as Zaporizhzhia (), is an oblast (region) in south-east Ukraine. Its administrative centre is the city of Zaporizhzhia. The oblast covers an area of , and has a population of The oblast is an import ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

).

In 1939, he graduated with honors from the Kuybyshev Military Engineering Academy and the Military Academy of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia

The Military Academy of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation () is the senior staff college of the Russian Armed Forces.

The academy is located in Moscow, on 14 Kholzunova Lane. It was founded in 1936 as a Soviet inst ...

. He took part in the battles of Khalkhin Gol

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (; ) were the decisive engagements of the undeclared Soviet–Japanese border conflicts involving the Soviet Union, Mongolian People's Republic, Mongolia, Empire of Japan, Japan and Manchukuo in 1939. The conflict wa ...

, against the Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

ese on the Manchurian border in 1939, and in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. He commanded troops in initial battles following 22 June 1941. During the war, he also commanded an infantry division

A division is a large military unit or Formation (military), formation, usually consisting of between 10,000 and 25,000 soldiers. In most armies, a division is composed of several regiments or brigades; in turn, several divisions typically mak ...

in the Baltic for three years.

He went on a military career and reached high ranks during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. After the war, being a decorated veteran

A veteran () is a person who has significant experience (and is usually adept and esteemed) and expertise in an job, occupation or Craft, field.

A military veteran is a person who is no longer serving in the military, armed forces.

A topic o ...

, he left active career and taught at the Frunze Military Academy

The M. V. Frunze Military Academy (), or in full the Military Order of Lenin and the October Revolution, Red Banner, Order of Suvorov Academy in the name of M. V. Frunze (), was a military academy of the Soviet and later the Russian Armed Forces ...

, reaching the rank of a Major General.

In 1949, Grigorenko defended his Ph.D. thesis on the theme "Features of the organization and conduct of combined offensive battle in the mountains."

In 1960, he completed work on his doctoral thesis. (The biography of Grigorenko on the website of the Andrei Sakharov Museum and Public Center) Over 70 of his scientific works on military science

Military science is the study of military processes, institutions, and behavior, along with the study of warfare, and the theory and application of organized coercive force. It is mainly focused on theory, method, and practice of producing mi ...

were published.

Dissident activities

In 1961, Petro Grigorenko started to openly criticize what he considered the excesses of theKhrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

regime. He maintained that the special privileges of the political elite did not comply with the principles laid down by Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

. Grigorenko formed a dissident group—The Group for the Struggle to Revive Leninism. Soviet psychiatrists sitting as legally constituted commissions to inquire into his sanity diagnosed him at least three times—in April 1964, August 1969, and November 1969. When arrested, Grigorenko was sent to Moscow's Lubyanka prison, and from there for psychiatric examination to the Serbsky Institute where the first commission, which included Snezhnevsky and Lunts, diagnosed him as suffering from the mental disease in the form of a paranoid delusional development of his personality, accompanied by early signs of cerebral arteriosclerosis. Lunts, reporting later on this diagnosis, mentioned that the symptoms of paranoid development were "an overestimation of his own personality reaching messianic proportions" and "reformist ideas." Grigorenko was not responsible for his actions and was thereby forcibly committed to a special psychiatric hospital. While there, the government deprived him of his pension despite the fact that, by law, a mentally sick military officer was entitled to a pension. After six months, Grigorenko was found to be in remission and was released for outpatient follow-up. He required that his pension be restored. Although he began to draw pension again, it was severely reduced.

Grigorenko took part in the defense of Andrei Sinyavsky

Andrei Donatovich Sinyavsky (; 8 October 1925 – 25 February 1997) was a Russian writer and Soviet dissident known as a defendant in the Sinyavsky–Daniel trial of 1965.

Sinyavsky was a literary critic for ''Novy Mir'' and wrote works critic ...

and Yuli Daniel

Yuli Markovich Daniel ( rus, Ю́лий Ма́ркович Даниэ́ль, p=ˈjʉlʲɪj ˈmarkəvʲɪtɕ dənʲɪˈelʲ, a=Yuliy Markovich Daniel'.ru.vorb.oga; 15 November 1925 – 30 December 1988) was a Russian writer and Soviet disside ...

and sharply protested against the arrests of young writers Alexander Ginzburg

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg ( rus, Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Ги́нзбург, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈɡʲinzbʊrk, a=Alyeksandr Il'yich Ginzburg.ru.vorb.oga; 21 November 1936 – 19 July 2002), was a Russian journalist ...

, Yuri Galanskov

Yuri Timofeyevich Galanskov (; 19 June 1939 – 4 November 1972) was a Russian poet, historian, human rights activist and dissident. For his political activities, such as founding and editing samizdat almanac '' Phoenix'', he was incarcerated i ...

, Alexey Dobrovolsky

Alexey Alexandrovich Dobrovolsky (; 13 October 1938 – 19 May 2013), also known as Dobroslav (), was a Soviet-Russian ideologue of Slavic neopaganism, a founder of Russian Rodnoverie, national anarchist, and Neo-Nazism, neo-Nazi.

Dobrovolsky ...

, and others. During the closed political trials of 1965–1969, he was often present at the courthouses, demanding to open the doors of the courtrooms for everyone, explained to the people gathered around the goals of the defendants, expressed his dissatisfaction with the distortions in the internal political life of the country, a demanded a return to "true Leninism".

He became much more active in his dissidence, stirred other people to protest some of the State's actions and received several warnings from the KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

. In 1968, after Grigorenko protested the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, he was expelled from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

, arrested and ultimately committed to a mental hospital until being freed on 26 June 1974 after 5 years of detention. As Grigorenko had followers in Moscow, he was lured to the far-away Tashkent

Tashkent (), also known as Toshkent, is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uzbekistan, largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of more than 3 million people as of April 1, 2024. I ...

. While there, he was again arrested and examined by a psychiatric team. None of the manifestations or symptoms cited by the Lunts commission were found there by the second examination conducted under the chairmanship of Fyodor Detengof. The diagnosis and evaluation made by the commission was that "Grigorenko's riminalactivity had a purposeful character, it was related to concrete events and facts... It did not reveal any signs of illness or delusions." The psychiatrists reported that he was not mentally sick, but responsible for his actions. He had firm convictions which were shared by many of his colleagues and were not delusional. Having evaluated the records of his preceding hospitalization, they concluded that he had not been sick at that time either. The KGB brought Grigorenko back to Moscow and, three months later, arranged a second examination at the Serbsky Institute. Once again, these psychiatrists found that he had "a paranoid development of the personality" manifested by reformist ideas. The commission, which included Lunts and was chaired by Morozov, recommended that he be recommitted to a special psychiatric hospital for the socially dangerous. Eventually, after almost four years, he was transferred to a regular mental hospital. On 17 January 1971 Grigorenko was asked whether he had changed his convictions and replied that "Convictions are not like gloves, one cannot easily change them".

In 1971, Dr. Semen Hluzman wrote an in-absentia psychiatric report on Grigorenko. Hluzman came to the conclusion that Grigorenko was mentally sane and had been taken to mental hospitals for political reasons. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hluzman was forced to serve seven years in labor camp for defending Grigorenko against the charge of insanity. Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members a ...

declared Grigorenko a prisoner of conscience

A prisoner of conscience (POC) is anyone imprisoned because of their race, sexual orientation, religion, or political views. The term also refers to those who have been imprisoned or persecuted for the nonviolent expression of their conscienti ...

.

Grigorenko became the key defender of Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

deported to Soviet Central Asia

Soviet Central Asia () was the part of Central Asia administered by the Russian SFSR and then the Soviet Union between 1918 and 1991, when the Central Asian Soviet republics declared independence. It is nearly synonymous with Russian Turkest ...

. He advised the Tatar activists not to confine their protests to the USSR, but to appeal also to international organizations including the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

.

Grigorenko was one of the first who questioned the official Soviet version of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

history. He pointed out that just prior to the German attack on June 22, 1941, vast Soviet troops were concentrated in the area west of Białystok

Białystok is the largest city in northeastern Poland and the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is the List of cities and towns in Poland, tenth-largest city in Poland, second in terms of population density, and thirteenth in area.

Biał ...

, deep in occupied Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, getting ready for a surprise offensive, which made them vulnerable to be encircled in case of surprise German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

attack. His ideas were later advanced by Viktor Suvorov

Vladimir Bogdanovich Rezun (; ; born 20 April 1947), known by his pseudonym of Viktor Suvorov (), is a former Soviet GRU officer who is the author of non-fiction books about World War II, the GRU and the Soviet Army, as well as fictional books ...

.

After publishing Abdurakhman Avtorkhanov's book ''Stalin and the Soviet Communist Party: A Study in the Technology of Power'', Grigorenko made and distributed its copies by photographing and typewriting. In 1976, Grigorenko helped found the Moscow Helsinki Group

The Moscow Helsinki Group (also known as the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group, ) was one of Russia's leading human rights organisations. It was originally set up in 1976 to monitor Soviet compliance with the Helsinki Accords and to report to the West ...

and the Ukrainian Helsinki Group.

In the United States

On 20 December 1977, Grigorenko was allowed to go abroad for medical treatment. His health was ruined during forcible confinement in KGB-run mental hospitals. On 30 November 1977, Grigorenko arrived in theUnited States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and was stripped of his Soviet citizenship. In Grigorenko's words, Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

signed the decree of depriving Grigorenko of Soviet citizenship on the ground that he was undermining the prestige of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. The 1970s marked a peak in the use of external exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

as a punitive measure by the Soviet Union (as opposed to the internal type, which was highest between the mid-1930s and early 1950s); often the pattern was that a trip abroad for work or medical treatment was transformed into permanent exile. In the same year, Grigorenko became a U.S. citizen.

Being in USA since 1977, Grigorenko took an active part in the activities of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group foreign affiliate. On 23 July 1978, Grigorenko made a statement condemning the trials of Soviet dissidents Anatoliy Shcharanskyi, Alexander Ginzburg

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg ( rus, Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Ги́нзбург, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈɡʲinzbʊrk, a=Alyeksandr Il'yich Ginzburg.ru.vorb.oga; 21 November 1936 – 19 July 2002), was a Russian journalist ...

and Viktoras Petkus.

In 1979 in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, Grigorenko was examined by the team of psychologists and psychiatrists including Alan A. Stone, the then President of American Psychiatric Association

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the main professional organization of psychiatrists and trainee psychiatrists in the United States, and the largest psychiatric organization in the world. It has more than 39,200 members who are in ...

. The team could find no evidence of mental disease in Grigorenko and his history consistent with mental disease in the past. Their findings were drawn up and publicized by Walter Reich. Grigorenko's case confirmed accusations, Stone wrote, that psychiatry in the Soviet Union was at times a tool of political repression.

Petro Grigorenko described his life and views, and his assessment by Soviet psychiatrists and periods of incarceration in prison hospitals in his 1981 memoirs ''V Podpolye Mozhno Vstretit Tolko Krys…'' (''In the Underground One Can Meet Only Rats…''). In 1982, the book was translated into English by Thomas P. Whitney under the title ''Memoirs'' and reviewed by Alexander J. Motyl, Raymond L. Garthoff

Raymond Leonard "Ray" Garthoff (born March 26, 1929) is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a specialist on arms control, intelligence, the Cold War, NATO, and the former Soviet Union. He is a former United States Ambassadors to Bulga ...

, John C. Campbell, Adam Ulam, Raisa Orlova and Lev Kopelev.

In 1983, he said he considered the American political-economic system to be "the best that mankind has found to date." In 1983, a stroke he suffered left him partially paralyzed. Grigorenko died on 21 February 1987 in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

.

In 1991, a commission, composed of psychiatrists from all over the Soviet Union and led by Modest Kabanov, then director of the Bekhterev Psychoneurological Institute in St Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

, spent six months reviewing Grigorenko's patient files. They drew up 29 thick volumes of legal proceedings, and in October 1991 reversed the official Soviet diagnosis of Grigorenko's psychiatric condition. In 1992, an official post-mortem forensic psychiatric commission of experts met in Ukraine. They removed the stigma of being a mental patient and confirmed that there were no grounds for the debilitating treatment he underwent in high security psychiatric hospitals for many years. The 1992 psychiatric examination of Grigorenko was described by the '' Nezavisimiy Psikhiatricheskiy Zhurnal'' in its numbers 1–4 of 1992.

Family

Petro Grigorenko was married to Zinaida Mikhailovna Grigorenko and they had five sons: Anatoliy, Heorhiy, Oleh, Viktor and Andrew. Two of them died as children. In 1975, Andrew, anelectrical engineer

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems that use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

, was declared to have inherited his father's insanity. He was expelled from the USSR to the US, two years before Petro and Zinaida Hryhorenko themselves travelled to the United States. Andrew was repeatedly told that since his father was mentally ill, then he was also mad. If he did not stop speaking out in defense of human rights and his father, they told him, he would also be sent to the psikhushka

Psikhushka (; ) is a Russian ironic diminutive for psychiatric hospital. In Russia, the word entered everyday vocabulary. This word has been occasionally used in English, since the Soviet dissident movement and diaspora community in the West use ...

. Subsequently, Andrew Grigorenko became the founder and president of General Petro Grigorenko Foundation, dedicated to the study of his father's legacy.

Name spelling versions

The different Latin spellings of Grigorenko's name exist due to the lack of uniform transliteration rules for the Ukrainian names in the middle of the 20th century, when he became internationally known. The correct modern transliteration would be ''Petro Hryhorenko''. However, according to the American identification documents of the late general the official spelling of his name was established as ''Petro Grigorenko''. The same spelling is engraved on his gravestone at the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of St. Andrew in South Bound Brook, New Jersey, USA. The same spelling is also retained by his surviving American descendants: son Andrew and granddaughters Tetiana and Olga.Honours and awards

; Soviet Union

; Ukraine

In

; Soviet Union

; Ukraine

In Kharkiv

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

the local Georgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( 189618 June 1974) was a Soviet military leader who served as a top commander during World War II and achieved the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union. During World War II, Zhukov served as deputy commander-in-ch ...

Avenue was renamed to Petro Hryhorenko Avenue to comply with decommunization laws (this was several times undone by the Kharkiv City Council

Kharkiv City Council () is the city council for the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, and is elected every five years to run the city's local government.

History

Until 1870, members of the city council were elected according to the estate order, and ...

).LB.ua (24 February 2021)

Books, interviews, letters

* * * * * * *publicly available unabridged Russian text

*

* *

* * * * * * * * * *

publicly available unabridged Russian text

* * * *

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * *Video

* *References

External links

A Chronicle of Current Events (1968-1982): tagged references to Grigorenko (abuse of psychiatry, Crimean Tatar movement, Ukrainian Helsinki Group, expulsion from the USSR, etc.)

General Petro Grigorenko Foundation - English, Russian, Ukrainian

''Pyotr Grigorenko''

International Marxist Group. * (The biography of Grigorenko on the website of the Moscow Helsinki Group) * (The biography of Grigorenko on the website of the Online Library of Alexander Belousenko) * (The biography of Grigorenko on the website of the Andrei Sakharov Museum and Public Center) {{DEFAULTSORT:Grigorenko, Pyotr 1907 births 1987 deaths People from Zaporizhzhia Oblast People from Berdyansky Uyezd Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Soviet major generals Cyberneticists Soviet dissidents Ukrainian dissidents Moscow Helsinki Group Ukrainian Helsinki Group Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes Ukrainian human rights activists Soviet human rights activists Soviet prisoners and detainees Amnesty International prisoners of conscience held by the Soviet Union Denaturalized citizens of the Soviet Union Soviet expellees Soviet emigrants to the United States Soviet psychiatric abuse whistleblowers Psychiatric survivor activists Russian military writers 20th-century Russian memoirists Russian-language writers Ukrainian writers in Russian Stalinism-era scholars and writers Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute alumni Military Engineering-Technical University alumni Academic staff of the Frunze Military Academy Soviet military personnel of World War II from Ukraine Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner Chevaliers of the Order For Courage, 1st class Ukrainian prisoners and detainees Burials at Ukrainian Orthodox Church Cemetery, South Bound Brook