Pullman Strike on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Pullman Strike comprised two interrelated strikes in 1894 that shaped national labor policy in the United States during a period of deep economic depression. First came a strike by the

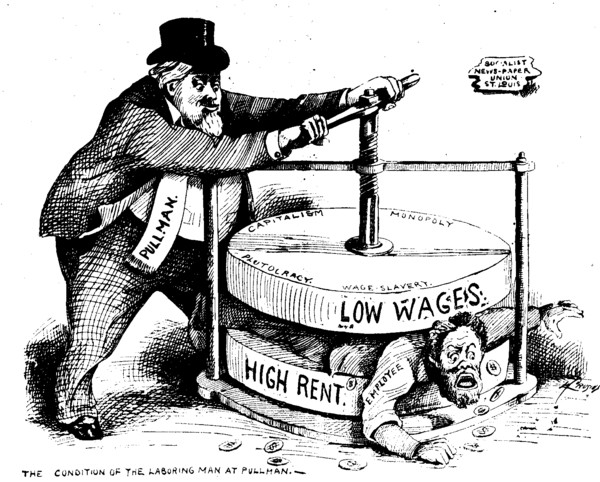

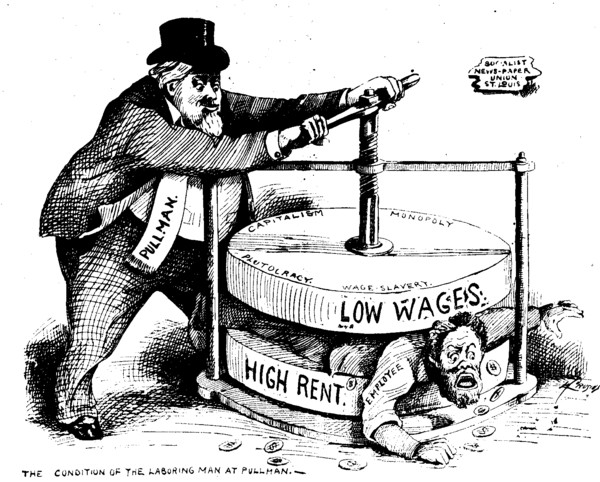

Low wage, expensive rent, and the failing ideal of a utopian workers settlement were already a problem for the Pullman workers.

Low wage, expensive rent, and the failing ideal of a utopian workers settlement were already a problem for the Pullman workers.

Following his release from prison in 1895, ARU President Debs became a committed advocate of

Following his release from prison in 1895, ARU President Debs became a committed advocate of

''The Periodical Press and the Pullman Strike: An Analysis of the Coverage and Interpretation of the Railroad Strike of 1894 by Eight Journals of Opinion and Reportage''

MA thesis. University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1973. * Eggert, Gerald G. ''Railroad labor disputes: the beginnings of federal strike policy'' (U of Michigan Press, 1967). * Ginger, Ray. ''The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene V. Debs.'' (1949)

online

* Hirsch, Susan Eleanor. ''After the Strike: A Century of Labor Struggle at Pullman.'' (U of Illinois Press, 2003). * Kelly, Jack. ''The Edge of Anarchy: The Railroad Barons, the Gilded Age, and the Greatest Labor Uprising in America''. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2019. * Laughlin, Rosemary. ''The Pullman strike of 1894'' (2006

online

for high schools * Lindsey, Almont. ''The Pullman Strike: The Story of a Unique Experiment and of a Great Labor Upheaval.'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1943

online

a standard history * Lindsey, Almont. "Paternalism and the Pullman Strike," ''American Historical Review,'' Vol. 44, No. 2 (Jan., 1939), pp. 272–289 * Nevins, Allan Nevins. ''Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage.'' (1933) pp. 611–628 * Novak, Matt. "Blood on the Tracks in Pullman: Chicagoland's Failed Capitalist Utopia" (2014) ''Gizmodo.com'

online

* Papke, David Ray. ''The Pullman Case: The Clash of Labor and Capital in Industrial America.'' Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1999. * Reiff, Janice L. "Rethinking Pullman: Urban Space and Working-Class Activism" ''Social Science History'' (2000) 24#1 pp. 7–3

online

* Rondinone, Troy. "Guarding the Switch: Cultivating Nationalism During the Pullman Strike," ''Journal of the Gilded Age & Progressive Era'' (2009) 8(1): 83–109. * Salvatore, Nick. ''Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist.'' Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1984

online

* Schneirov, Richard, et al. (eds.) ''The Pullman Strike and the Crisis of the 1890s: Essays on Labor and Politics.'' (U of Illinois Press, 1999)

online

* Smith, Carl. ''Urban Disorder and the Shape of Belief: The Great Chicago Fire, the Haymarket Bomb, and the Model Town of Pullman.'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. * White, Richard. ''Railroaded: the transcontinentals and the making of modern America'' (WW Norton, 2011), pp 429–450. * Winston, A.P. "The Significance of the Pullman Strike," ''Journal of Political Economy,'' vol. 9, no. 4 (Sept. 1901), pp. 540–561. * Wish, Harvey. "The Pullman Strike: A Study in Industrial Warfare," ''Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society'' (1939) 32#3 pp. 288–312

''The Government and the Chicago Strike of 1894''

904 Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1913. * Manning, Thomas G. and David M. Potter, eds. ''Government and the American Economy, 1870 to the Present'' (1950) pp 117–160. * United States Strike Commission

''Report on the Chicago Strike of June–July, 1894.''

Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895. 54pp of history and 680pp of documents, testimony and recommendations * Warne, Colston E. ed. ''The Pullman Boycott 1894: The problem of Federal Intervention'' (1955) 113pp.

{{Authority control History of labor relations in the United States Labor-related violence in the United States Riots and civil disorder in Illinois 1894 in Illinois 1894 labor disputes and strikes History of rail transportation in the United States Labor disputes in Illinois Transportation labor disputes in the United States Socialism in Illinois 1894 riots Rail transportation labor disputes in the United States 1894 in rail transport Progressive Era in the United States Pullman Company May 1894 Labor relations by company 1890s strikes in the United States Wildcat strikes June 1894 July 1894

American Railway Union

The American Railway Union (ARU) was briefly among the largest labor unions of its time and one of the first Industrial unionism, industrial unions in the United States. Launched at a meeting held in Chicago in February 1893, the ARU won an early ...

(ARU) against the Pullman Company

The Pullman Company, founded by George Pullman, was a manufacturer of railroad cars in the mid-to-late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century, during the boom of railroads in the United States. Through rapid late-19th century d ...

's factory in Chicago in spring 1894. When it failed, the ARU launched a national boycott against all trains that carried Pullman passenger cars. The nationwide railroad boycott that lasted from May 11 to July 20, 1894, was a turning point for US labor law

United States labor law sets the rights and duties for employees, labor unions, and employers in the US. Labor law's basic aim is to remedy the " inequality of bargaining power" between employees and employers, especially employers "organized in ...

. It pitted the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman Company, the main railroads, the main labor unions, and the federal government of the United States under President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

. The strike and boycott shut down much of the nation's freight and passenger traffic west of Detroit

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

, Michigan. The conflict began in Chicago, on May 11 when nearly 4,000 factory employees of the Pullman Company began a wildcat strike

A wildcat strike is a strike action undertaken by unionised workers without union leadership's authorization, support, or approval; this is sometimes termed an unofficial industrial action. The legality of wildcat strikes varies between countries ...

in response to recent reductions in wages. Most of the factory workers who built Pullman cars lived in the "company town

A company town is a place where all or most of the stores and housing in the town are owned by the same company that is also the main employer. Company towns are often planned with a suite of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schoo ...

" of Pullman just outside of Chicago. Pullman was designed as a model community by its namesake founder and owner George Pullman

George Mortimer Pullman (March 3, 1831 – October 19, 1897) was an American engineer and industrialist. He designed and manufactured the Pullman (car or coach), Pullman sleeping car and founded a Pullman, Chicago, company town in Chicago for t ...

. Jennie Curtis who lived in Pullman was president of seamstress union ARU LOCAL 269 gave a speech at the ARU convention urging people to strike.

As the Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States. It began in February 1893 and officially ended eight months later. The Panic of 1896 followed. It was the most serious economic depression in history until the Great Depression of ...

weakened much of the economy, railroad companies ceased purchasing new passenger cars made by Pullman. The company laid off workers and reduced the wages of retained workers. Among the reasons for the strike were the absence of democracy within the town of Pullman and its politics, the rigid paternalistic control of the workers by the company, excessive water and gas rates, and a refusal by the company to allow workers to buy and own houses. They had not yet formed a union. Founded in 1893 by Eugene V. Debs, the ARU was an organization of railroad workers. Debs brought in ARU organizers to Pullman and signed up many of the disgruntled factory workers. When the Pullman Company

The Pullman Company, founded by George Pullman, was a manufacturer of railroad cars in the mid-to-late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century, during the boom of railroads in the United States. Through rapid late-19th century d ...

refused recognition of the ARU or any negotiations, ARU called a strike against the factory, but it showed no sign of success. To win the strike, Debs decided to stop the movement of Pullman cars on railroads. The over-the-rail Pullman employees (such as conductors and porters) did not go on strike.

Debs and the ARU called a massive boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

against all trains that carried a Pullman car. It affected most rail lines west of Detroit and at its peak involved some 250,000 workers in 27 states. The American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

(AFL) opposed the boycott because the ARU was trying to take its membership. The high prestige railroad brotherhoods of Conductors and Engineers were opposed to the boycott. The Fireman brotherhood—of which Debs had been a prominent leader—was split. The General Managers' Association of the railroads coordinated the opposition. Thirty people were killed in riots in Chicago alone. Historian David Ray Papke, building on the work of Almont Lindsey published in 1942, estimated that another 40 were killed in other states. Property damage exceeded $80 million.

The federal government obtained an injunction against the union, Debs, and other boycott leaders, ordering them to stop interfering with trains that carried mail cars. After the strikers refused, Grover Cleveland ordered in the Army to stop the strikers from obstructing the trains. Violence broke out in many cities, and the strike collapsed. Defended by a team including Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the 19th century for high-profile representations of trade union causes, and in the 20th century for several criminal matters, including the ...

, Debs was convicted of violating a court order and sentenced to prison; the ARU then dissolved.

Background

Low wage, expensive rent, and the failing ideal of a utopian workers settlement were already a problem for the Pullman workers.

Low wage, expensive rent, and the failing ideal of a utopian workers settlement were already a problem for the Pullman workers. Company town

A company town is a place where all or most of the stores and housing in the town are owned by the same company that is also the main employer. Company towns are often planned with a suite of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schoo ...

s, like Pullman, were constructed with a plan to keep everything within a small vicinity to keep workers from having to move far. Using company-run shops and housing took away competition leaving areas open to exploitation, monopolization, and high prices. These conditions were exacerbated by the Panic of 1893. George Pullman

George Mortimer Pullman (March 3, 1831 – October 19, 1897) was an American engineer and industrialist. He designed and manufactured the Pullman (car or coach), Pullman sleeping car and founded a Pullman, Chicago, company town in Chicago for t ...

had reduced wages 20 to 30% on account of falling sales. However, he did not cut rents nor lower prices at his company stores, nor did he give any indication of a commensurate cost of living adjustment. The employees filed a complaint with the company's owner, George Pullman. Pullman refused to reconsider and even dismissed the workers who were protesting. The strike began on May 11, 1894, when the rest of his staff went on strike. This strike would end by the president sending U.S. troops to break up the scene.

Boycott

Many of the Pullman factory workers joined theAmerican Railway Union

The American Railway Union (ARU) was briefly among the largest labor unions of its time and one of the first Industrial unionism, industrial unions in the United States. Launched at a meeting held in Chicago in February 1893, the ARU won an early ...

(ARU), led by Eugene V. Debs, which supported their strike by launching a boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

in which ARU members refused to run trains containing Pullman cars. At the time of the strike approximately 35% of Pullman workers were members of the ARU. The plan was to force the railroads to bring Pullman to compromise. Debs began the boycott on June 26, 1894. Within four days, 125,000 workers on twenty-nine railroads had " walked off" the job rather than handle Pullman cars. The railroads coordinated their response through the General Managers' Association, which had been formed in 1886 and included 24 lines linked to Chicago. The railroads began hiring replacement workers ( strikebreakers), which increased hostilities. Many African Americans were recruited as strikebreakers and crossed picket lines, as they feared that the racism expressed by the American Railway Union would lock them out of another labor market. This added racial tension to the union's predicament.

In Chicago, where the railroads found it difficult to continue operating without striking employees, the boycott had the greatest effect. The pressure put on by the population at the time on Pullman increased as ARU members used "unity" to shut down rail networks. But, by refusing to engage in negotiations and receiving federal court orders to put an end to the strike, the railroads, who were unified under the General Managers' Association, showed all of its corporate power. Conflict broke out between strikers and replacement workers that often turned violent in Chicago alone, and federal troops were eventually called in to bring the peace back. Strikers had been separated more from public sympathy by the media, which often than not supported industrialists, portraying them as disruptive. The boycott revealed the amount of racial and economic divides while showing the growing influence of industrial labor unions. Debs's arrest afterward stamped the Pullman Strike as a turning point in labor history by showing the federal government's preference for corporate interests over workers' rights.

On June 29, 1894, Debs hosted a peaceful meeting to rally support for the strike from railroad workers at Blue Island, Illinois

Blue Island is a city in Cook County, Illinois, United States, south of Chicago Loop, Chicago's Loop. Blue Island is adjacent to the city of Chicago and shares its northern boundary with that city's Morgan Park, Chicago, Morgan Park neighborho ...

. Afterward, groups within the crowd became enraged and set fire to nearby buildings and derailed a locomotive.Harvey Wish, "The Pullman Strike: A Study in Industrial Warfare," ''Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society'' (1939) 32#3, pp. 288–312 Elsewhere in the western states, sympathy strikers prevented transportation of goods by walking off the job, obstructing railroad tracks, or threatening and attacking strikebreakers. This increased national attention and the demand for federal action.

Federal intervention

The strike was handled by US Attorney General Richard Olney, who was appointed by PresidentGrover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

. A majority of the president's cabinet in Washington, D.C., backed Olney's proposal for federal troops to be dispatched to Chicago to put an end to the "rule of terror." In comparison to his $8,000 compensation as Attorney General, Olney had been a railroad attorney and had a $10,000 retainer from the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad. Olney got an injunction from circuit court justices Peter S. Grosscup and William Allen Woods (both anti-union) prohibiting ARU officials from "compelling or encouraging" any impacted railroad employees "to refuse or fail to perform any of their duties". Grosscup later remarked that he opposed the involvement of the judiciary system as he believed labor disputes to be a “partisan action.” After hearing the injunction was put in place, railway operators telegrammed Olney to request their own injunction in anticipation of strikes. The injunction was disobeyed by Debs and other ARU leaders, in a telegraph to the western ARU branch, Debs responded "It will take more than injunctions to move trains, get everybody out. We are gaining ground everywhere." After injunctions were issued to other states, federal forces were dispatched to enforce them. Debs had been hesitant to start the strike, because he worried that violence would undermine the progress of the strike as well as provide reason for military intervention. Despite these concerns, Debs decided to put all of his efforts into the strike. He called on ARU members to ignore the federal court injunctions and the U.S. Army:

Strong men and broad minds only can resist the plutocracy and arrogant monopoly. Do not be frightened at troops, injunctions, or a subsidized press. Quit and remain firm. Commit no violence. American Railway Union will protect all, whether member or not when strike is off.Debs wanted a general strike of all union members in Chicago, but this was opposed by Samuel Gompers, head of the AFL, and other established unions, and it failed. United States Marshall John W. Arnold told those in Washington that “no force less than regular troops could procure the passage of mail trains or enforce the orders of federal court”. Federal troops were dispatched and arrived in Chicago the night of July 3. Debs first welcomed the military, believing that they would help to keep the peace and allow the strike and boycott to continue peacefully. The military was not, however, impartial; they were there to ensure that the trains ran, which would eventually weaken the boycott. Federal forces broke the ARU's attempts to shut down the national transportation system city by city. Thousands of US Marshals and 12,000 US Army troops, led by Brigadier General Nelson Miles, took part in the operation. After learning that President Cleveland had sent troops without the permission of local or state authorities, Illinois Governor John Altgeld requested an immediate withdrawal of federal troops. President Cleveland claimed that he had a legal, constitutional responsibility for the mail; however, getting the trains moving again also helped further his fiscally conservative economic interests and protect capital, which was far more significant than the mail disruption. His lawyers argued that the boycott violated the

Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce and consequently prohibits unfair monopolies. It was passed by Congress and is named for S ...

, and represented a threat to public safety. The arrival of the military and the subsequent deaths of workers in violence led to further outbreaks of violence. During the course of the strike, 30 strikers were killed and 57 were wounded. Property damage exceeded $80 million.

Local responses

The strike affected hundreds of towns and cities across the country. Railroad workers were divided, for the old established Brotherhoods, which included the skilled workers such as engineers, firemen and conductors, did not support the labor action. ARU members did support the action, and often comprised unskilled ground crews. In many areas, townspeople and businessmen generally supported the railroads, while farmers—many affiliated with the Populists—supported the ARU. InBillings, Montana

Billings is the most populous Lists of populated places in the United States, city in the U.S. state of Montana, with a population of 117,116 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located in the south-central portion of the state, i ...

, an important rail center, a local Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

minister, J. W. Jennings, supported the ARU. In a sermon, he compared the Pullman boycott to the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was a seminal American protest, political and Mercantilism, mercantile protest on December 16, 1773, during the American Revolution. Initiated by Sons of Liberty activists in Boston in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colo ...

, and attacked Montana state officials and President Cleveland for abandoning "the faith of the Jacksonian fathers." Rather than defending "the rights of the people against aggression and oppressive corporations," he said party leaders were "the pliant tools of the codfish monied aristocracy who seek to dominate this country."Carroll Van West, ''Capitalism on the Frontier: Billings and the Yellowstone Valley in the Nineteenth Century'' (1993) p 200 Billings remained quiet but, on July 10, soldiers reached Lockwood, Montana

Lockwood is a census-designated place (CDP) in Yellowstone County, Montana, Yellowstone County, Montana, United States. It is not an organized city or town. The population was 7,195 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census.The population was ...

, a small rail center, where the troop train was surrounded by hundreds of angry strikers. Narrowly averting violence, the army opened the lines through Montana. When the strike ended, the railroads fired and blacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list; if people are on a blacklist, then they are considere ...

ed all the employees who had supported it.

In California, the boycott was effective in Sacramento

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of California and the seat of Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers in Northern California's Sacramento Valley, Sacramento's 2020 p ...

, a labor stronghold, but weak in the Bay Area and minimal in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

. The strike lingered as strikers expressed longstanding grievances over wage reductions, and indicated how unpopular the Southern Pacific Railroad

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials) was an American Railroad classes#Class I, Class I Rail transport, railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was oper ...

was. Strikers engaged in violence and sabotage; the companies saw it as civil war, while the ARU proclaimed it was a crusade for the rights of unskilled workers.

Public opinion

President Cleveland did not think Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld could manage the strike as it continued to cause more and more physical and economic damage. Altgeld's pro-labor mindset and social reformist sympathies were viewed by outsiders as being a form of "German Socialism". Critics of Altgeld worried that he was usually on the side of the workers. Outsiders also believed that the strike would get progressively worse since Altgeld "knew nothing about the problem of American evolution." Public opinion was mostly opposed to the strike and supported Cleveland's actions. Republicans and eastern Democrats supported Cleveland (the leader of the northeastern pro-business wing of the party), but southern and western Democrats as well as Populists generally denounced him. Chicago Mayor John Patrick Hopkins supported the strikers and stopped the Chicago Police from interfering before the strike turned violent. Governor Altgeld, a Democrat, denounced Cleveland and said he could handle all disturbances in his state without federal intervention. The press took the side of Cleveland and framed strikers as villains, while Mayor Hopkins took the side of strikers and Altgeld. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' and ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is an American daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1847, it was formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper", a slogan from which its once integrated WGN (AM), WGN radio and ...

'' placed much of the blame for the strikes on Altgeld.

Media coverage was extensive and generally negative. News reports and editorials commonly depicted the strikers as foreigners who contested the patriotism expressed by the militias and troops involved, as numerous recent immigrants

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as permanent residents. Commuters, tourists, and other short- ...

worked in the factories and on the railroads. The editors warned of mobs, aliens, anarchy

Anarchy is a form of society without rulers. As a type of stateless society, it is commonly contrasted with states, which are centralized polities that claim a monopoly on violence over a permanent territory. Beyond a lack of government, it can ...

, and defiance of the law. The ''New York Times'' called it "a struggle between the greatest and most important labor organization and the entire railroad capital." President Cleveland and the press feared that the strike would foment anarchy and social unrest. Cleveland demonized the ARU for encouraging an uprising against federal authority and endangering the public. The large numbers of immigrant workers who participated in the strike further stoked the fears of anarchy. In Chicago, some established church leaders denounced the boycott, most notably Reverend Englebert C. Oggel pastor of the Presbyterian church in Pullman. Oggel voiced his opposition to the strikes and supported the recent actions of George Pullman. In response, members of the congregation left in large numbers. Conversely, Reverend William H. Cawardine, pastor of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Pullman, was a well-known supporter of the ARU and the striking workers. A number of lesser-known ministers also voiced support for workers and claimed that Christ would not neglect those who were suffering.

Aftermath

Debs was arrested on federal charges, including conspiracy to obstruct the mail as well as disobeying an order directed to him by the Supreme Court to stop the obstruction of railways and to dissolve the boycott. He was defended byClarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the 19th century for high-profile representations of trade union causes, and in the 20th century for several criminal matters, including the ...

, a prominent attorney, as well as Lyman Trumbull. At the conspiracy trial Darrow argued that it was the railways, not Debs and his union, that met in secret and conspired against their opponents. Sensing that Debs would be acquitted, the prosecution dropped the charge when a juror took ill. Although Darrow also represented Debs at the United States Supreme Court for violating the federal injunction, Debs was sentenced to six months in prison.

Early in 1895, General Graham erected a memorial obelisk in the San Francisco National Cemetery at the Presidio in honor of four soldiers of the 5th Artillery killed in a Sacramento train crash of July 11, 1894, during the strike. The train wrecked crossing a trestle bridge

A trestle bridge is a bridge composed of a number of short spans supported by closely spaced frames usually carrying a railroad line. A trestle (sometimes tressel) is a rigid frame used as a support, historically a tripod used to support a st ...

purportedly dynamited by union members. Graham's monument included the inscription "Murdered by Strikers", a description he hotly defended. The obelisk remains in place.

In the aftermath of the Pullman Strike, the ARU was disbanded and the state ordered the company to sell off its residential holdings. Many Pullman workers joined the AFL after the collapse of the ARU. Following the death of George Pullman (1897), the Pullman company would be led by Robert Todd Lincoln, and Thomas Wickes would become the company's vice president. With this change the company would shift its focus away from its environmental strategy of having superior living and recreational accommodations to keep workers loyal, and would instead use the town of Pullman for more industrial purposes, building storage and repair shops in place of fields. While the Pullman company continued to grow, monopolizing the train car industry, the town of Pullman struggled with deteriorating housing and cramped living spaces. The company remained the area's largest employer before closing in the 1950s.

The area is both a National Historic Landmark and a Chicago Landmark District. Because of the significance of the strike, many state agencies and non-profit groups are hoping for many revivals of the Pullman neighborhoods, starting with Pullman Park, one of the largest projects. It was to be a $350 million mixed-use development on the site of an old steel plant. The plan was for 670,000 square feet of new retail space, a 125,000 square foot neighborhood recreation center, and 1,100 housing units.

Politics

Following his release from prison in 1895, ARU President Debs became a committed advocate of

Following his release from prison in 1895, ARU President Debs became a committed advocate of socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, helping in 1897 to launch the Social Democracy of America, a forerunner of the Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of America ...

. He ran for president in 1900 for the first of five times as head of the Socialist Party ticket.

Civil as well as criminal charges were brought against the organizers of the strike and Debs in particular, and the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

issued a unanimous decision, ''In re Debs

''In re Debs'', 158 U.S. 564 (1895), was a labor law case of the United States Supreme Court, which upheld a contempt of court conviction against Eugene V. Debs. Debs had the American Railway Union continue its 1894 Pullman Strike in violatio ...

,'' that rejected Debs' actions. The Illinois Governor John P. Altgeld was incensed at Cleveland for putting the federal government at the service of the employers, and for rejecting Altgeld's plan to use his state militia rather than federal troops to keep order.

Cleveland's administration appointed a national commission to study the causes of the 1894 strike; it found George Pullman's paternalism

Paternalism is action that limits a person's or group's liberty or autonomy against their will and is intended to promote their own good. It has been defended in a variety of contexts as a means of protecting individuals from significant harm, s ...

partly to blame and described the operations of his company town

A company town is a place where all or most of the stores and housing in the town are owned by the same company that is also the main employer. Company towns are often planned with a suite of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schoo ...

to be "un-American". The report condemned Pullman for refusing to negotiate and for the economic hardships he created for workers in the town of Pullman. "The aesthetic features are admired by visitors, but have little money value to employees, especially when they lack bread." The State of Illinois filed suit, and in 1898 the Illinois Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Illinois is the state supreme court, the highest court of the judiciary of Illinois. The court's authority is granted in Article VI of the current Illinois Constitution, which provides for seven justices elected from the fiv ...

forced the Pullman Company to divest ownership in the town, as its company charter did not authorize such operations. The town was annexed to Chicago. Much of it is now designated as an historic district, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

.

Labor Day

In 1894, in an effort to conciliate organized labor after the strike, President Grover Cleveland and Congress designatedLabor Day

Labor Day is a Federal holidays in the United States, federal holiday in the United States celebrated on the first Monday of September to honor and recognize the Labor history of the United States, American labor movement and the works and con ...

as a federal holiday in contrast with the more radical May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the Northern Hemisphere's March equinox, spring equinox and midsummer June solstice, solstice. Festivities ma ...

. Legislation for the holiday was pushed through Congress six days after the strike ended. Samuel Gompers, who had sided with the federal government in its effort to end the strike by the American Railway Union, spoke out in favor of the holiday.Bill Haywood, ''The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood,'' 1929, p. 78 ppbk.

See also

*United States labor law

United States labor law sets the rights and duties for employees, labor unions, and employers in the US. Labor law's basic aim is to remedy the " inequality of bargaining power" between employees and employers, especially employers "organized in ...

* History of rail transport in the United States

Railroads played a large role in the development of the United States from the Industrial Revolution in the Northeast (1820s–1850s) to the settlement of the West (1850s–1890s). The American railroad mania began with the founding of the first ...

* Murder of workers in labor disputes in the United States

* List of US labor strikes by size

References

Sources and further reading

* Bassett, Johnathan "The Pullman Strike of 1894," ''OAH Magazine of History'', Volume 11, Issue 2, Winter 1997, pp. 34–41, a lesson plan for high schools * Cooper, Jerry M. "The army as strikebreakerthe railroad strikes of 1877 and 1894." ''Labor History'' 18.2 (1977): 179–196. * DeForest, Walter S''The Periodical Press and the Pullman Strike: An Analysis of the Coverage and Interpretation of the Railroad Strike of 1894 by Eight Journals of Opinion and Reportage''

MA thesis. University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1973. * Eggert, Gerald G. ''Railroad labor disputes: the beginnings of federal strike policy'' (U of Michigan Press, 1967). * Ginger, Ray. ''The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene V. Debs.'' (1949)

online

* Hirsch, Susan Eleanor. ''After the Strike: A Century of Labor Struggle at Pullman.'' (U of Illinois Press, 2003). * Kelly, Jack. ''The Edge of Anarchy: The Railroad Barons, the Gilded Age, and the Greatest Labor Uprising in America''. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2019. * Laughlin, Rosemary. ''The Pullman strike of 1894'' (2006

online

for high schools * Lindsey, Almont. ''The Pullman Strike: The Story of a Unique Experiment and of a Great Labor Upheaval.'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1943

online

a standard history * Lindsey, Almont. "Paternalism and the Pullman Strike," ''American Historical Review,'' Vol. 44, No. 2 (Jan., 1939), pp. 272–289 * Nevins, Allan Nevins. ''Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage.'' (1933) pp. 611–628 * Novak, Matt. "Blood on the Tracks in Pullman: Chicagoland's Failed Capitalist Utopia" (2014) ''Gizmodo.com'

online

* Papke, David Ray. ''The Pullman Case: The Clash of Labor and Capital in Industrial America.'' Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1999. * Reiff, Janice L. "Rethinking Pullman: Urban Space and Working-Class Activism" ''Social Science History'' (2000) 24#1 pp. 7–3

online

* Rondinone, Troy. "Guarding the Switch: Cultivating Nationalism During the Pullman Strike," ''Journal of the Gilded Age & Progressive Era'' (2009) 8(1): 83–109. * Salvatore, Nick. ''Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist.'' Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1984

online

* Schneirov, Richard, et al. (eds.) ''The Pullman Strike and the Crisis of the 1890s: Essays on Labor and Politics.'' (U of Illinois Press, 1999)

online

* Smith, Carl. ''Urban Disorder and the Shape of Belief: The Great Chicago Fire, the Haymarket Bomb, and the Model Town of Pullman.'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. * White, Richard. ''Railroaded: the transcontinentals and the making of modern America'' (WW Norton, 2011), pp 429–450. * Winston, A.P. "The Significance of the Pullman Strike," ''Journal of Political Economy,'' vol. 9, no. 4 (Sept. 1901), pp. 540–561. * Wish, Harvey. "The Pullman Strike: A Study in Industrial Warfare," ''Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society'' (1939) 32#3 pp. 288–312

Primary sources

* Cleveland, Grover''The Government and the Chicago Strike of 1894''

904 Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1913. * Manning, Thomas G. and David M. Potter, eds. ''Government and the American Economy, 1870 to the Present'' (1950) pp 117–160. * United States Strike Commission

''Report on the Chicago Strike of June–July, 1894.''

Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895. 54pp of history and 680pp of documents, testimony and recommendations * Warne, Colston E. ed. ''The Pullman Boycott 1894: The problem of Federal Intervention'' (1955) 113pp.

External links

{{Authority control History of labor relations in the United States Labor-related violence in the United States Riots and civil disorder in Illinois 1894 in Illinois 1894 labor disputes and strikes History of rail transportation in the United States Labor disputes in Illinois Transportation labor disputes in the United States Socialism in Illinois 1894 riots Rail transportation labor disputes in the United States 1894 in rail transport Progressive Era in the United States Pullman Company May 1894 Labor relations by company 1890s strikes in the United States Wildcat strikes June 1894 July 1894