Puddling Furnace on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Puddling is the process of converting

Puddling is the process of converting

The puddling process began to be displaced with the introduction of the

The puddling process began to be displaced with the introduction of the

The process begins by preparing the puddling furnace. This involves bringing the furnace to a low temperature and then ''fettling'' it. Fettling is the process of painting the grate and walls around it with iron oxides, typically

The process begins by preparing the puddling furnace. This involves bringing the furnace to a low temperature and then ''fettling'' it. Fettling is the process of painting the grate and walls around it with iron oxides, typically

'The Development of the Early Steelmaking Processes – An Essay in the History of Technology' by Kenneth Charles Barraclough. Thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, May 1981

/ref>

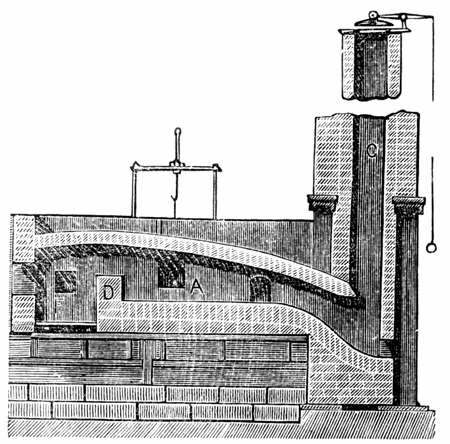

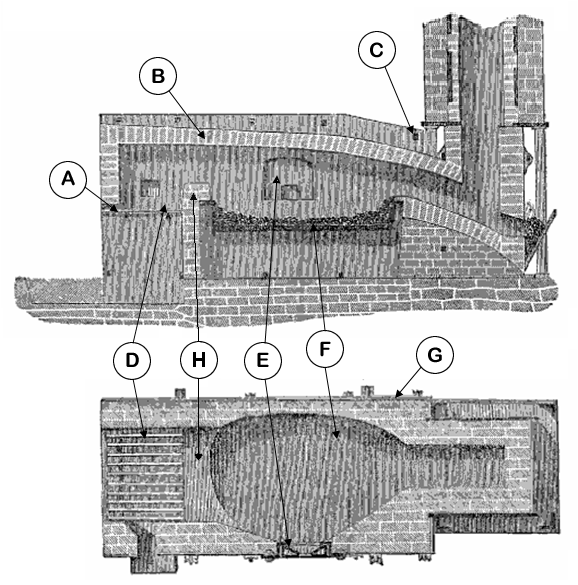

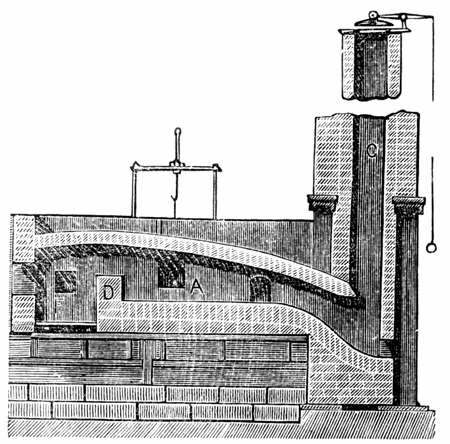

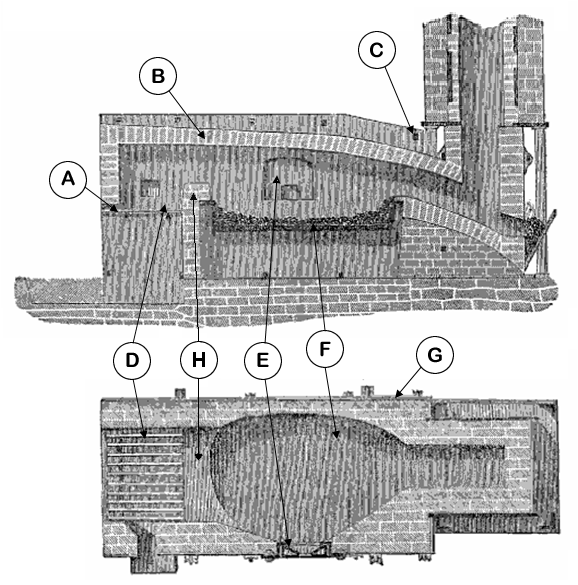

The puddling furnace is a metalmaking technology used to create

The puddling furnace is a metalmaking technology used to create  The hearth is where the iron is charged, melted and puddled. The hearth's shape is usually elliptical; in length and wide. If the furnace is designed to puddle white iron then the hearth depth is never more than . If the furnace is designed to boil gray iron then the average hearth depth is .

The fireplace, where the fuel is burned, used a cast iron grate which varied in size depending on the fuel used. If bituminous

The hearth is where the iron is charged, melted and puddled. The hearth's shape is usually elliptical; in length and wide. If the furnace is designed to puddle white iron then the hearth depth is never more than . If the furnace is designed to boil gray iron then the average hearth depth is .

The fireplace, where the fuel is burned, used a cast iron grate which varied in size depending on the fuel used. If bituminous

Paul Belford's paper

on N. Hingley & Sons Ltd * ''The Iron Puddler: My Life in the Rolling Mills and What Came of It''. by James J. Davis. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1922. (ghostwritten by C. L. Edson) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Puddling (Metallurgy) Steelmaking Chinese inventions English inventions Metallurgical processes

Puddling is the process of converting

Puddling is the process of converting pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

to bar (wrought) iron in a coal fired reverberatory furnace

A reverberatory furnace is a metallurgy, metallurgical or process Metallurgical furnace, furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term ''reverberation'' is use ...

. It was developed in England during the 1780s. The molten pig iron was stirred in a reverberatory furnace, in an oxidizing

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

environment to burn the carbon, resulting in wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

. It was one of the most important processes for making the first appreciable volumes of valuable and useful bar iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

(malleable wrought iron) without the use of charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

. Eventually, the furnace would be used to make small quantities of specialty steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

s.

Though it was not the first process to produce bar iron without charcoal, puddling was by far the most successful, and replaced the earlier potting and stamping processes, as well as the much older charcoal finery and bloomery

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its iron oxides, oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called ...

processes. This enabled a great expansion of iron production to take place in Great Britain, and shortly afterwards, in North America. That expansion constitutes the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

so far as the iron industry is concerned. Most 19th century applications of wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

, including the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower from 1887 to 1889.

Locally nicknamed "''La dame de fe ...

, bridges, and the original framework of the Statue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty (''Liberty Enlightening the World''; ) is a colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor, within New York City. The copper-clad statue, a gift to the United States from the people of French Thir ...

, used puddled iron.

History

Modern puddling was one of several processes developed in the second half of the 18th century in Great Britain for producingbar iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

from pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

without the use of charcoal. It gradually replaced the earlier charcoal-fueled process, conducted in a finery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and decarburization, removing carbon from the molten cast iron through Redo ...

.

The need for puddling

Pig iron contains much freecarbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

and is brittle

A material is brittle if, when subjected to stress, it fractures with little elastic deformation and without significant plastic deformation. Brittle materials absorb relatively little energy prior to fracture, even those of high strength. ...

. Before it can be used, and before it can be worked by a blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

, it must be converted to a more malleable form as bar iron, the early stage of wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

.

Abraham Darby's successful use of coke for his blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

In a ...

at Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a town in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called The Gorge, Shro ...

in 1709 reduced the price of iron, but this coke-fuelled pig iron was not initially accepted as it could not be converted to bar iron by the existing methods. Sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

impurities from the coke made it 'red short

Red-short, hot-short refers to brittleness of steels at red-hot temperatures. It is often caused by high sulfur levels, in which case it is also known as sulfur embrittlement.

Iron or steel, when heated to above 460 °C (900 °F), glows ...

', or brittle when heated, and so the finery process was unworkable for it. It was not until around 1750, when steam powered blowing increased furnace temperatures enough to allow sufficient lime to be added to remove the sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

, that coke pig iron began to be adopted. Also, better processes were developed to refine it.

Invention

Abraham Darby II

Abraham Darby, in his lifetime called Abraham Darby the Younger, referred to for convenience as Abraham Darby II (12 May 1711 – 31 March 1763) was the second man of that name in an English Quaker family that played an important role in the ea ...

, son of the blast furnace innovator, managed to convert pig iron to bar iron in 1749, but no details are known of his process. The Cranage brothers

Thomas and George Cranege (also spelled ''Cranage''), who worked in the ironworking industry in England in the 1760s, are notable for introducing a new method of producing wrought iron from pig iron.

Experiment of 1766

The process of converting p ...

, also working alongside the River Severn

The River Severn (, ), at long, is the longest river in Great Britain. It is also the river with the most voluminous flow of water by far in all of England and Wales, with an average flow rate of at Apperley, Gloucestershire. It rises in t ...

, allegedly achieved this experimentally by using a coal-fired reverbatory furnace

A reverberatory furnace is a metallurgy, metallurgical or process Metallurgical furnace, furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term ''reverberation'' is use ...

, in which the iron and the sulphurous coal could be kept separate but it was never used commercially. They were the first to hypothesise that iron could be converted from pig iron to bar iron by the action of heat alone. Although they were unaware of the necessary effects of the oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

supplied by the air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

, they had at least abandoned the previous misapprehension that mixture with materials from the fuel were needed. Their experiments were successful and they were granted patent Nº851 in 1766, but no commercial adoption seems to have been made of their process.

In 1783, Peter Onions

Peter Onions (1724 – 1798) was an English ironmaster and the inventor of an early puddling process used for the refining of pig iron into wrought iron.

Biography

Onions was born in Broseley, Shropshire, later moving to Merthyr Tydfil in Wal ...

at Dowlais constructed a larger reverbatory furnace. He began successful commercial puddling with this and was granted patent Nº1370. The furnace was improved by Henry Cort

Henry Cort (c. 1740 – 23 May 1800) was an English ironware producer who was formerly a Navy pay agent. During the Industrial Revolution in England, Cort began refining iron from pig iron to wrought iron (or bar iron) using innovative productio ...

at Fontley in Hampshire in 1783–84 and patented in 1784. Cort added dampers to the chimney, avoiding some of the risk of overheating and 'burning' the iron. Cort's process consisted of stirring molten pig iron in a reverberatory furnace in an oxidising atmosphere, thus decarburising it. When the iron "came to nature", that is, to a pasty consistency, it was gathered into a puddled ball, shingled, and rolled (as described below). This application of grooved rollers to the rolling mill

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through one or more pairs of rolls to reduce the thickness, to make the thickness uniform, and/or to impart a desired mechanical property. The concept is simi ...

, to roll narrow bars, was also Cort's adoption of existing rolling mills on the Continent. Cort's efforts to license this process were unsuccessful as it only worked with charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

smelted pig iron. Modifications were made by Richard Crawshay at his ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloome ...

at Cyfarthfa in Merthyr Tydfil, which incorporated an initial refining process developed at their neighbours at Dowlais.

Ninety years after Cort's invention, an American labor newspaper recalled the advantages of his system:

"When iron is simply melted and run into any mold, its texture is granular, and it is so brittle as to be quite unreliable for any use requiring muchCort's process (as patented) only worked for whitetensile strength Ultimate tensile strength (also called UTS, tensile strength, TS, ultimate strength or F_\text in notation) is the maximum stress that a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before breaking. In brittle materials, the ultimate .... The process of puddling consisted in stirring the molten iron run out in a puddle, and had the effect of so changing its anotomic arrangement as to render the process of rolling more efficacious."

cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

, not grey cast iron, which was the usual feedstock for forges of the period. This problem was resolved probably at Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil () is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydfil, daughter of K ...

by combining puddling with one element of a slightly earlier process. This involved another kind of hearth known as a 'refinery' or 'running out fire'. The pig iron was melted in this and run out into a trough. The slag separated, and floated on the molten iron, and was removed by lowering a dam at the end of the trough. The effect of this process was to desiliconise the metal, leaving a white brittle metal, known as 'finers metal'. This was the ideal material to charge to the puddling furnace. This version of the process was known as 'dry puddling' and continued in use in some places as late as 1890.

An additional development in refining gray iron was known as 'wet puddling', also known as 'boiling' or 'pig boiling'. This was invented by a puddler named Joseph Hall at Tipton

Tipton is an industrial town in the metropolitan borough of Sandwell, in the county of the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. It had a population of 38,777 at the 2011 UK Census. It is located northwest of Birmingham and southeas ...

. He began adding scrap iron to the charge. Later, he tried adding iron scale (in effect, iron oxide

An iron oxide is a chemical compound composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Ferric oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of which is rust.

Iron ...

s such as FeO, , or ). The result was spectacular in that the furnace boiled violently, producing carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

bubbles. This was due to a chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemistry, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. When chemical reactions occur, the atoms are rearranged and the reaction is accompanied by an Gibbs free energy, ...

between the iron oxide

An iron oxide is a chemical compound composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Ferric oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of which is rust.

Iron ...

s in the scale and the carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

dissolved in the pig iron: . To his surprise, the resultant puddle ball produced good iron.

One big problem with puddling was that up to 15% of the iron was drawn off with the slag because sand was used for the bed. Hall substituted roasted tap cinder for the bed, which cut this waste to 8%, declining to 5% by the end of the century.

Hall subsequently became a partner in establishing the Bloomfield Iron Works at Tipton in 1830, the firm becoming Bradley, Barrows and Hall from 1834. This is the version of the process most commonly used in the mid to late 19th century. Wet puddling had the advantage that it was much more efficient than dry puddling (or any earlier process). The best yield of iron achievable from dry puddling is one ton of iron from 1.3 tons of pig iron (a yield of 77%), but the yield from wet puddling was nearly 100%.

The production of mild steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobalt ...

in the puddling furnace was achieved circa 1850 in Westphalia

Westphalia (; ; ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the region is almost identical with the h ...

, Germany and was patented in Great Britain on behalf of Lohage, Bremme and Lehrkind. It worked only with pig iron made from certain kinds of ore. The cast iron had to be melted quickly and the slag to be rich in manganese

Manganese is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese was first isolated in the 1770s. It is a transition m ...

. When the metal came to nature, it had to be removed quickly and shingled before further decarburization

Decarburization (or decarbonization) is the process of decreasing carbon content, which is the opposite of carburization.

The term is typically used in metallurgy, describing the decrease of the content of carbon in metals (usually steel). Decar ...

occurred. The process was taken up at the Low Moor Ironworks at Bradford

Bradford is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in West Yorkshire, England. It became a municipal borough in 1847, received a city charter in 1897 and, since the Local Government Act 1972, 1974 reform, the city status in the United Kingdo ...

in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

(England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

) in 1851 and in the Loire

The Loire ( , , ; ; ; ; ) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône.

It rises in the so ...

valley in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

in 1855. It was widely used.

Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is steelmaking, removal of impurities and undesired eleme ...

, which produced steel. This could be converted into wrought iron using the Aston process for a fraction of the cost and time. For comparison, an average size charge for a puddling furnace was while a Bessemer converter charge was (13,600 kg). The puddling process could not be scaled up, being limited by the amount that the puddler could handle. It could only be expanded by building more furnaces.

Process

The process begins by preparing the puddling furnace. This involves bringing the furnace to a low temperature and then ''fettling'' it. Fettling is the process of painting the grate and walls around it with iron oxides, typically

The process begins by preparing the puddling furnace. This involves bringing the furnace to a low temperature and then ''fettling'' it. Fettling is the process of painting the grate and walls around it with iron oxides, typically hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of . ...

; this acts as a protective coating keeping the melted metal from burning through the furnace. Sometimes finely pounded cinder was used instead of hematite. In this case the furnace must be heated for 4–5 hours to melt the cinder and then cooled before charging.

Either white cast iron or refined iron is then placed in hearth of the furnace, a process known as ''charging''. For wet puddling, scrap iron and/or iron oxide is also charged. This mixture is then heated until the top melts, allowing for the oxides to begin mixing; this usually takes 30 minutes. This mixture is subjected to a strong current of air and stirred by long bars with hooks on one end, called ''puddling bars'' or ''rabbles'', through doors in the furnace.R. F. Tylecote, 'Iron in the Industrial Revolution' in R. F. Tylecote, ''The Industrial Revolution in Metals'' (Institute of Metals, London 1991), 236-40. This helps the iron-III (the species acting as an oxidiser

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ''electron donor''). In ot ...

) from the oxides to react with impurities in the pig iron, notably silicon

Silicon is a chemical element; it has symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic lustre, and is a tetravalent metalloid (sometimes considered a non-metal) and semiconductor. It is a membe ...

, manganese (to form slag) and to some degree sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

and phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

, which form gases that escape with the exhaust of the furnace.

More fuel is then added and the temperature is raised. The iron completely melts and the carbon starts to burn off. When wet puddling, the formation of carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

(CO) and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

() due to reactions with the added iron oxide will cause bubbles to form that cause the mass to appear to boil. This process causes the slag

The general term slag may be a by-product or co-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and recycled metals depending on the type of material being produced. Slag is mainly a mixture of metal oxides and silicon dioxide. Broadly, it can be c ...

to puff up on top, giving the rabbler a visual indication of the progress of the combustion. As the carbon burns off, the melting temperature of the mixture rises from , so the furnace has to be continually fed during this process. The melting point

The melting point (or, rarely, liquefaction point) of a substance is the temperature at which it changes state of matter, state from solid to liquid. At the melting point the solid and liquid phase (matter), phase exist in Thermodynamic equilib ...

increases since the carbon atoms within the mixture act as a solute in solution which lowers the melting point of the iron mixture (like road salt on ice).

Working as a two-man crew, a puddler and helper could produce about 1500 kg of iron in a 12-hour shift. The strenuous labour, heat and fumes caused puddlers to have a very short life expectancy, with most dying in their 30s. Puddling was never able to be automated because the puddler had to sense when the balls had "come to nature".

Puddled steel

In the late 1840s, the German chemist developed a modification of the puddling process to produce notiron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

but steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

at the Haspe Iron Works in Hagen; it was subsequently commercialized in Germany, France and the UK in the 1850s, and puddled steel was the main raw material for Krupp

Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp (formerly Fried. Krupp AG and Friedrich Krupp GmbH), trade name, trading as Krupp, was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century as well as Germany's premier weapons manufacturer dur ...

cast steel even in the 1870s. Before the development of the basic refractory lining (with magnesium oxide

Magnesium oxide (MgO), or magnesia, is a white hygroscopic solid mineral that occurs naturally as periclase and is a source of magnesium (see also oxide). It has an empirical formula of MgO and consists of a lattice of Mg2+ ions and O2− ions ...

, MgO) and the wide-scale adoption of the Gilchrist–Thomas process

The Gilchrist–Thomas process or Thomas process is a historical process for refining (metallurgy), refining pig iron, derived from the Bessemer converter. It is named after its inventors who patented it in 1877: Percy Gilchrist, Percy Carlyle Gi ...

ca. 1880 it complemented acidic Bessemer converter

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is removal of impurities and undesired elements, primar ...

s (with a refractory material made of ) and open hearths because unlike them, the puddling furnace could utilize phosphorous ores abundant in Continental Europe./ref>

Puddling furnace

The puddling furnace is a metalmaking technology used to create

The puddling furnace is a metalmaking technology used to create wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

or steel from the pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

produced in a blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

In a ...

. The furnace is constructed to pull the hot air over the iron without the fuel coming into direct contact with the iron, a system generally known as a reverberatory furnace

A reverberatory furnace is a metallurgy, metallurgical or process Metallurgical furnace, furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term ''reverberation'' is use ...

or open hearth furnace

An open-hearth furnace or open hearth furnace is any of several kinds of industrial Industrial furnace, furnace in which excess carbon and other impurities are burnt out of pig iron to Steelmaking, produce steel. Because steel is difficult to ma ...

. The major advantage of this system is keeping the impurities of the fuel separated from the charge.

The hearth is where the iron is charged, melted and puddled. The hearth's shape is usually elliptical; in length and wide. If the furnace is designed to puddle white iron then the hearth depth is never more than . If the furnace is designed to boil gray iron then the average hearth depth is .

The fireplace, where the fuel is burned, used a cast iron grate which varied in size depending on the fuel used. If bituminous

The hearth is where the iron is charged, melted and puddled. The hearth's shape is usually elliptical; in length and wide. If the furnace is designed to puddle white iron then the hearth depth is never more than . If the furnace is designed to boil gray iron then the average hearth depth is .

The fireplace, where the fuel is burned, used a cast iron grate which varied in size depending on the fuel used. If bituminous coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

is used then an average grate size is and is loaded with of coal. If anthracite

Anthracite, also known as hard coal and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a lustre (mineralogy)#Submetallic lustre, submetallic lustre. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy densit ...

coal is used then the grate is and is loaded with of coal. Due to the great heat required to melt the charge the grate had to be cooled, lest it melt with the charge. This was done by running a constant flow of cool air on it, or by throwing water on the bottom of the grate.

A double puddling furnace is similar to a single puddling furnace, with the major difference being there are two work doors allowing two puddlers to work the furnace at the same time. The biggest advantage of this setup is that it produces twice as much wrought iron. It is also more economical and fuel efficient compared to a single furnace.

See also

*Crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron, cast iron, iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. Crucible steel was first developed in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE in Sout ...

* Double hammer

* Steelmaking

Steelmaking is the process of producing steel from iron ore and/or scrap. Steel has been made for millennia, and was commercialized on a massive scale in the 1850s and 1860s, using the Bessemer process, Bessemer and open hearth furnace, Siemens-M ...

Footnotes

;Sources * *Further reading

* W. K. V. Gale, ''Iron and Steel'' (Longmans, London 1969), 55ff. * W. K. V. Gale, ''The British Iron and Steel Industry: a technical history'' (David & Charles, Newton Abbot 1967), 62–66. * R. A. Mott, 'Dry and Wet Puddling' ''Trans. Newcomen Soc.'' 49 (1977–78), 153–58. * R. A. Mott (ed. P. Singer), ''Henry Cort: the great finer'' (The Metals Society, London 1983). * K. Barraclough, ''Steelmaking: 1850–1900'' (Institute of Materials, London 1990), 27–35. *Paul Belford's paper

on N. Hingley & Sons Ltd * ''The Iron Puddler: My Life in the Rolling Mills and What Came of It''. by James J. Davis. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1922. (ghostwritten by C. L. Edson) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Puddling (Metallurgy) Steelmaking Chinese inventions English inventions Metallurgical processes