Protofeminist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Protofeminism is a concept that anticipates modern

At the beginning of the renaissance, women's sole role and social value was held to be reproduction.

This gender role defined a woman's main identity and purpose in life.

At the beginning of the renaissance, women's sole role and social value was held to be reproduction.

This gender role defined a woman's main identity and purpose in life.

feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

in eras when the feminist concept as such was still unknown. This refers particularly to times before the 20th century, although the precise usage is disputed, as 18th-century feminism

The history of feminism comprises the narratives (chronology, chronological or thematic) of the Feminist movement, movements and Feminist theory, ideologies which have aimed at Feminism and equality, equal Women's rights, rights for women. Whil ...

and 19th-century feminism are often subsumed into "feminism". The usefulness of the term ''protofeminist'' has been questioned by some modern scholars, as has the term ''postfeminist''.

History

Ancient Greece and Rome

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, according to Elaine Hoffman Baruch, " rguedfor the total political and sexual equality of women, advocating that they be members of his highest class... those who rule and fight." Book five of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's '' The Republic'' discusses the role of women:

Are dogs divided into hes and shes, or do they both share equally in hunting and in keeping watch and in the other duties of dogs? Or do we entrust to the males the entire and exclusive care of the flocks, while we leave the females at home, under the idea that the bearing and suckling their puppies is labour enough for them?''The Republic'' states that women in Plato's ideal state should work alongside men, receive equal education, and share equally in all aspects of the state. The sole exception involved women working in capacities which required less physical strength. In the first century CE, the Roman Stoic philosopher

Gaius Musonius Rufus

Gaius Musonius Rufus (; ) was a Roman Stoicism, Stoic philosopher of the 1st century AD. He taught philosophy in Rome during the reign of Nero and so was sent into exile in 65 AD, returning to Rome only under Galba. He was allowed to stay in Rome ...

entitled one of his 21 Discourses "That Women Too Should Study Philosophy", in which he argues for equal education of women in philosophy: "If you ask me what doctrine produces such an education, I shall reply that as without philosophy no man would be properly educated, so no woman would be. Moreover, not men alone, but women too, have a natural inclination toward virtue and the capacity for acquiring it, and it is the nature of women no less than men to be pleased by good and just acts and to reject the opposite of these. If this is true, by what reasoning would it ever be appropriate for men to search out and consider how they may lead good lives, which is exactly the study of philosophy, but inappropriate for women?"

Islamic world

While in the pre-modern period there was no formal feminist movement in Islamic nations, there were a number of important figures who spoke for improving women's rights and autonomy. The medieval mystic and philosopherIbn Arabi

Ibn Arabi (July 1165–November 1240) was an Andalusian Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest com ...

argued that while men were favored over women as prophets, women were just as capable of sainthood

In Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Anglican, Oriental Orth ...

as men.

In the 12th century, the Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

scholar Ibn Asakir

Ibn Asakir (; 1105–c. 1176) was a Syrian Sunni Islamic scholar, who was one of the most prominent and renowned experts on Hadith and Islamic history in the medieval era. and a disciple of the Sufi mystic Abu al-Najib Suhrawardi. Ibn Asakir was ...

wrote that women could study and earn ''ijazah

An ''ijazah'' (, "permission", "authorization", "license"; plural: ''ijazahs'' or ''ijazat'') is a license authorizing its holder to transmit a certain text or subject, which is issued by someone already possessing such authority. It is particul ...

s'' in order to transmit religious texts like the hadiths

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

. This was especially the case for learned and scholarly families, who wanted to ensure the highest possible education for both their sons and daughters. However, some men did not approve of this practice, such as Muhammad ibn al-Hajj (died 1336), who was appalled by women speaking in loud voices and exposing their '' 'awra'' in the presence of men while listening to the recitation of books.

In the 12th century, the Islamic philosopher and ''qadi

A qadi (; ) is the magistrate or judge of a Sharia court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and minors, and supervision and auditing of public works.

History

The term '' was in use from ...

'' (judge) Ibn Rushd

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, math ...

, commenting on Plato's views in ''The Republic'' on equality between the sexes, concluded that while men were stronger, it was still possible for women to perform the same duties as men. In ''Bidayat al-mujtahid'' (The Distinguished Jurist's Primer) he added that such duties could include participation in warfare and expressed discontent with the fact that women in his society were typically limited to being mothers and wives. Several women are said to have taken part in battles or helped in them during the Muslim conquests The Muslim conquests, Muslim invasions, Islamic conquests, including Arab conquests, Arab Islamic conquests, also Iranian Muslim conquests, Turkic Muslim conquests etc.

*Early Muslim conquests

** Ridda Wars

**Muslim conquest of Persia

*** Muslim co ...

and fitnas, including Nusaybah bint Ka'ab and Aisha

Aisha bint Abi Bakr () was a seventh century Arab commander, politician, Muhaddith, muhadditha and the third and youngest wife of the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Aisha had an important role in early Islamic h ...

.

Christian medieval Europe

In Christian medieval Europe, the dominant view was that women were intellectually and morally weaker than men, having been tainted by the original sin of Eve as described in biblical tradition. This was used to justify many limits placed on women, such as not being allowed to own property, or being obliged to obey fathers or husbands at all times. This view and curbs derived from it were disputed even in medieval times. Medieval European protofeminists recognized as important to the development of feminism includeMarie de France

Marie de France (floruit, fl. 1160–1215) was a poet, likely born in France, who lived in England during the late 12th century. She lived and wrote at an unknown court, but she and her work were almost certainly known at the royal court of Kin ...

, Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine ( or ; ; , or ; – 1 April 1204) was Duchess of Aquitaine from 1137 to 1204, Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, and Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II. As ...

, Bettisia Gozzadini

Bettisia Gozzadini also known as Bitisia Biltisia and Beatrix (1209 – 2 November 1261), was a Bolognese jurist who lectured at the University of Bologna from about 1239. She is thought to be the first woman to have taught at a university.

Li ...

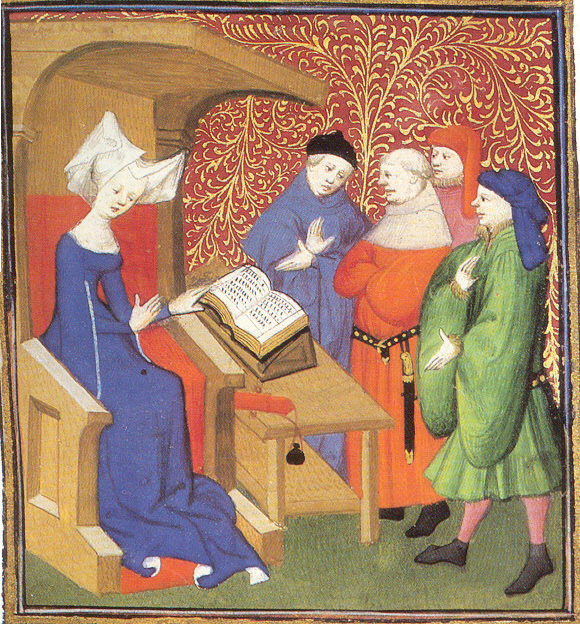

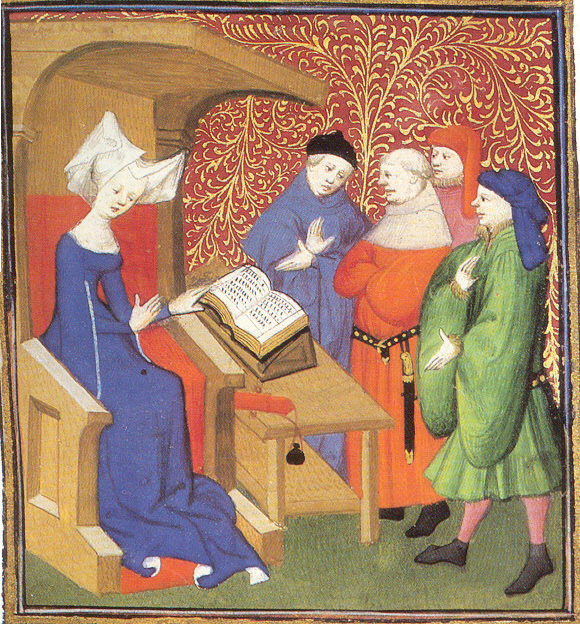

, Nicola de la Haye, Christine de Pizan

Christine de Pizan or Pisan (, ; born Cristina da Pizzano; September 1364 – ), was an Italian-born French court writer for King Charles VI of France and several French royal dukes, in both prose and poetry.

Christine de Pizan served as a cour ...

, Jadwiga of Poland

Jadwiga (; 1373 or 137417 July 1399), also known as Hedwig (from German) and in , was the first woman to be crowned as monarch of the Kingdom of Poland. She reigned from 16 October 1384 until her death. Born in Buda, she was the youngest daught ...

, and Laura Cereta.

Women in the Peasants' Revolt

The 1381Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black ...

was a peasant rebellion in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

in which English women played prominent roles. On 14 June 1381, the Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

and Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, Simon Sudbury

Simon Sudbury ( – 14 June 1381) was Bishop of London from 1361 to 1375, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1375 until his death, and in the last year of his life Lord Chancellor, Lord Chancellor of England. He met a violent death during the Peasan ...

, was dragged from the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

and beheaded by the rebels. Leading the group that executed him was Johanna Ferrour, who ordered his execution in response to Sudbury's harsh poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources. ''Poll'' is an archaic term for "head" or "top of the head". The sen ...

es. She also ordered the beheading of the Lord High Treasurer

The Lord High Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in England, below the Lord H ...

, Sir Robert Hales, for his involvement with the taxes. Ferrour also participated in the looting of the Savoy Palace by the rebels, stealing a chest of gold. The Chief Justice of the King's Bench

The Lord or Lady Chief Justice of England and Wales is the head of the judiciary of England and Wales and the president of the courts of England and Wales.

Until 2005 the lord chief justice was the second-most senior judge of the English a ...

, Sir John Cavendish, was beheaded by rebels after Katherine Gamen untied the boat he planned on escaping them in.

Bates College

Bates College () is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. Anchored by the Historic Quad, the campus of Bates totals with a small urban campus which includes 33 Victorian ...

professor Sylvia Federico argues that women often had the strongest desire to participate in revolts, including the Peasants' Revolt. They did all that men did, and were just as violent in rebelling against the government, if not more so. Ferrour was not the only female leader of the Peasants' Revolt; one Englishwoman was indicted for encouraging an attack on a prison at Maidstone in Kent, and another was responsible for robbing a multitude of mansions, which left servants too scared to return afterwards. Although there were only a small number of female leaders involved in the Peasants' Revolt, there were surprising numbers of women among the rebels, including 70 in Suffolk

Suffolk ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county ...

. The women involved had valid reasons for desiring to be so and on occasions taking a leading role. The 1380 poll tax was tougher on married women, so it is unsurprising that some women were as violent as men in their involvement. Their acts of violence signified mounting hatred for the government.

Hrotsvitha

Hrotsvitha

Hrotsvitha (–973) was a secular canoness who wrote drama and Christian poetry under the Ottonian dynasty. She was born in Bad Gandersheim to Saxon nobles and entered Gandersheim Abbey as a canoness. She is considered the first female writer ...

, a German secular canoness, was born about 935 and died about 973. Her work is still seen as important, as she was the first female writer from the German lands, the first female historian, and apparently the first person since antiquity to write dramas in the Latin West.

Since her rediscovery in the 1600s by Conrad Celtis, Hrotsvitha has become a source of particular interest and study for feminists, who have begun to place her work in a feminist context, some arguing that while Hrotsvitha was not a feminist, that she is important to the history of feminism.

European Renaissance

Restrictions on women

At the beginning of the renaissance, women's sole role and social value was held to be reproduction.

This gender role defined a woman's main identity and purpose in life.

At the beginning of the renaissance, women's sole role and social value was held to be reproduction.

This gender role defined a woman's main identity and purpose in life. Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

, a well-known exemplar of the love of wisdom to Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

humanists, said that he tolerated his first wife Xanthippe

Xanthippe (; ; fl. 5th–4th century BCE) was an Classical Athens, ancient Athenian, the wife of Socrates and mother of their three sons: Lamprocles, Sophroniscus, and Menexenus. She was likely much younger than Socrates, perhaps by as much as ...

because she bore him sons, in the same way as one tolerated the noise of geese because they produce eggs and chicks. This analogy perpetuated the claim that a woman's sole role was reproduction.

Marriage in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

defined a woman: she was whom she married. Till marriage she remained her father's property. Each had few rights beyond privileges granted by a husband or father. She was expected to be chaste, obedient, pleasant, gentle, submissive, and unless sweet-spoken, silent. In William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's 1593 play ''The Taming of the Shrew

''The Taming of the Shrew'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1590 and 1592. The play begins with a framing device, often referred to as the induction, in which a mischievous nobleman tricks a drunke ...

'', Katherina is seen as unmarriageable for her headstrong, outspoken nature, unlike her mild sister Bianca. She is seen as a wayward shrew who needs taming into submission. Once tamed, she readily goes when Petruchio summons her. Her submission is applauded; she is accepted as a proper woman, now "conformable to other household Kates."

Unsurprisingly, therefore, most women were barely educated. In a letter to Lady Baptista Maletesta of Montefeltro in 1424, the humanist Leonardo Bruni

Leonardo Bruni or Leonardo Aretino ( – March 9, 1444) was an Italian humanist, historian and statesman, often recognized as the most important humanist historian of the early Renaissance. He has been called the first modern historian. He was t ...

wrote, "While you live in these times when learning has so far decayed that it is regarded as positively miraculous to meet a learned man, let alone a woman." eonardo Bruni, "Study of Literature to Lady Baptista Maletesta of Montefeltro," 1494./ref> Bruni himself thought women had no need of education because they were not engaged in social forums for which such discourse was needed. In the same letter he wrote,For why should the subtleties of... a thousand... rhetorical conundra consume the powers of a woman, who never sees the forum? The contests of the forum, like those of warfare and battle, are the sphere of men. Hers is not the task of learning to speak for and against witnesses, for and against torture, for and against reputation.... She will, in a word, leave the rough-and-tumble of the forum entirely to men."

"Witch literature"

Starting with theMalleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise about witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic Church, Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinisation of names, Latini ...

, Renaissance Europe saw the publication of numerous treatises on witches: their essence, their features, and ways to spot, prosecute and punish them. This helped to reinforce and perpetuate the view of women as dangerous, morally corrupt sinners who sought to corrupt men, and to retain the restrictions placed on them.

Advocating women's learning

Yet not all agreed with this negative view of women and the restrictions on them.Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 – 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, nor was she ...

states, "The first time we see a woman take up her pen in defense of her sex" was when Christine de Pizan

Christine de Pizan or Pisan (, ; born Cristina da Pizzano; September 1364 – ), was an Italian-born French court writer for King Charles VI of France and several French royal dukes, in both prose and poetry.

Christine de Pizan served as a cour ...

wrote ''Épître au Dieu d'Amour'' (Epistle to the God of Love) and ''The Book of the City of Ladies

''The Book of the City of Ladies'', or ''Le Livre de la Cité des Dames'', is a book written by Christine de Pizan believed to have been finished by 1405. Perhaps Pizan's most famous literary work, it is her second work of lengthy prose. Pizan u ...

'', at the turn of the 15th century. A notable male advocate of women's superiority was Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa in ''The Superior Excellence of Women Over Men''.

Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine,

historical Spanish: , now: ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the Wives of Henry VIII, first wife of King Henry VIII from their marr ...

, commissioned a book by Juan Luis Vives

Juan Luis Vives y March (; ; ; ; 6 March 6 May 1540) was a Spaniards, Spanish (Valencian people, Valencian) scholar and Renaissance humanist who spent most of his adult life in the southern Habsburg Netherlands. His beliefs on the soul, insigh ...

arguing that women had a right to education, and encouraged and popularized education for women in England in her time as Henry VIII's wife.

Vives and fellow Renaissance humanist Agricola

Agricola, the Latin word for farmer, may also refer to:

People Cognomen or given name

:''In chronological order''

* Gnaeus Julius Agricola (40–93), Roman governor of Britannia (AD 77–85)

* Sextus Calpurnius Agricola, Roman governor of the m ...

argued that aristocratic women at least required education. Roger Ascham

Roger Ascham (; 30 December 1568)"Ascham, Roger" in '' The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 617. was an English scholar and didactic writer, famous for his prose style, his pr ...

educated Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

, who read Latin and Greek and wrote occasional poems

{{Short pages monitor