Protocols Of Zion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated text purporting to detail a Jewish plot for global domination. Largely plagiarized from several earlier sources, it was first published in

Resentment towards Jews, for the aforementioned reasons, existed in Russian society, but the idea of a ''Protocols''-esque

Resentment towards Jews, for the aforementioned reasons, existed in Russian society, but the idea of a ''Protocols''-esque

In the United States, ''The Protocols'' are to be understood in the context of the

In the United States, ''The Protocols'' are to be understood in the context of the

In 1920–1921, the history of the concepts found in the ''Protocols'' was traced back to the works of Goedsche and Jacques Crétineau-Joly by

In 1920–1921, the history of the concepts found in the ''Protocols'' was traced back to the works of Goedsche and Jacques Crétineau-Joly by

Evidence presented at the trial, which strongly influenced later accounts up to the present, was that the ''Protocols'' were originally written in French by agents of the Tzarist secret police (the Okhrana). However, this version has been questioned by several modern scholars. Michael Hagemeister discovered that the primary witness Alexandre du Chayla had previously written in support of the

Evidence presented at the trial, which strongly influenced later accounts up to the present, was that the ''Protocols'' were originally written in French by agents of the Tzarist secret police (the Okhrana). However, this version has been questioned by several modern scholars. Michael Hagemeister discovered that the primary witness Alexandre du Chayla had previously written in support of the

Print

Masami Uno's book ''If You Understand Judea You Can Comprehend the World: 1990 Scenario for the 'Final Economic War became popular in Japan around 1987 and was based upon the ''Protocols''.

Protocols of the Elders of Zion: Key Dates

– The Holocaust Encyclopedia (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

''The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion''

translated by Victor E. Marsden at archive.org

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (Original Russian Edition)''

at archive.org

FBI historical documents

{{DEFAULTSORT:Protocols of the Elders of Zion, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, 1903 documents 1905 books 1920 books 1900s hoaxes Antisemitic forgeries Antisemitic books Conspiracist books Conspiracy theories involving Jews Document forgeries Antisemitism in the Russian Empire Literary forgeries Religious hoaxes Political forgery Works of unknown authorship Books involved in plagiarism controversies Censored books Books adapted into television series Propaganda in Russia

Imperial Russia

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor/empress, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* ...

in 1903, translated into multiple languages, and disseminated internationally in the early part of the 20th century. It played a key part in popularizing belief in an international Jewish conspiracy

The international Jewish conspiracy or the world Jewish conspiracy is an antisemitic trope that has been described as "one of the most widespread and long-running conspiracy theories". Although it typically claims that a malevolent, usually gl ...

.

The text was exposed as fraudulent by the British newspaper ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' in 1921 and by the German newspaper ''Frankfurter Zeitung

The ''Frankfurter Zeitung'' (, ) was a German-language newspaper that appeared from 1856 to 1943. It emerged from a market letter that was published in Frankfurt. In Nazi Germany, it was considered the only mass publication not completely control ...

'' in 1924. Beginning in 1933, distillations of the work were assigned by some German teachers, as if they were factual, to be read by German schoolchildren throughout Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. It remains widely available in numerous languages, in print and on the Internet, and continues to be presented by antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

groups as a genuine document. It has been described as "probably the most influential work of antisemitism ever written".

Creation

The ''Protocols'' is a fabricated document purporting to be factual. Textual evidence shows that it could not have been produced prior to 1901: the document alludes to the assassinations ofUmberto I

Umberto I (; 14 March 1844 – 29 July 1900) was King of Italy from 9 January 1878 until his assassination in 1900. His reign saw Italy's expansion into the Horn of Africa, as well as the creation of the Triple Alliance among Italy, Germany an ...

(d. 1900) and William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

(d. 1901), for example, as though these events were plotted out in advance. The title of Sergei Nilus

Sergei Aleksandrovich Nilus (also ''Sergius'', and variants; ; – 14 January 1929) was a Russian religious writer, self-described mystic, and prolific antisemite.

His book ''Velikoe v malom i antikhrist, kak blizkaja politicheskaja vozmozh ...

' widely distributed first edition contains the dates "1902–1903", and it is likely that the document was actually written at this time in Russia. Cesare G. De Michelis

Cesare G. De Michelis (born 20 April 1944 in Rome) is a scholar and professor of Russian literature at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy.

Biography

He is also an authority on the notorious plagiarism, hoax, and literary forgery known as ...

argues that it was manufactured in the months after a Russian Zionist congress in September 1902, and that it was originally a parody of Jewish idealism meant for internal circulation among antisemites until it was decided to clean it up and publish it as if it were real. Self-contradictions in various testimonies show that the individuals involved—including the text's initial publisher, Pavel Krushevan—deliberately obscured the origins of the text and lied about it in the decades afterwards.

Political conspiracy background

Towards the end of the 18th century, following thePartitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partition (politics), partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place between 1772 and 1795, toward the end of the 18th century. They ended the existence of the state, resulting in the eli ...

, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

conquered the world's largest Jewish population. The Jews lived in ''shtetl

or ( ; , ; Grammatical number#Overview, pl. ''shtetelekh'') is a Yiddish term for small towns with predominantly Ashkenazi Jews, Ashkenazi Jewish populations which Eastern European Jewry, existed in Eastern Europe before the Holocaust. The t ...

s'' in the West of the Empire, in the Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement was a western region of the Russian Empire with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 1917 (''de facto'' until 1915) in which permanent settlement by Jews was allowed and beyond which the creation of new Jewish settlem ...

and until the 1840s, local Jewish affairs were organised through the ''qahal

The ''qahal'' (), sometimes spelled ''kahal'', was a theocratic organizational structure in ancient Israelite society according to the Hebrew Bible, See column345-6 and an Ashkenazi Jewish system of a self-governing community or kehila from ...

'', the semi-autonomous Jewish local government, including for purposes of taxation and conscription into the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army () was the army of the Russian Empire, active from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was organized into a standing army and a state militia. The standing army consisted of Regular army, regular troops and ...

. Following the ascent of liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

in Europe and among the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

in Russia, the Tsarist civil service became more hardline in its reactionary policies, upholding Tsar Nicholas I

Nicholas I, group=pron (Russian language, Russian: Николай I Павлович; – ) was Emperor of Russia, List of rulers of Partitioned Poland#Kings of the Kingdom of Poland, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 18 ...

's slogan of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality

Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality (; Transliteration, transliterated: Pravoslávie, samoderzhávie, naródnost'), also known as Official Nationalism,Riasanovsky, p. 132 was the dominant Imperial ideological doctrine of Russian Emperor Nichol ...

, whereby non-Orthodox and non-Russian subjects, including Jews, Catholics, and Protestants, were viewed as a subversive fifth column

A fifth column is a group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. The activities of a fifth column can be overt or clandestine. Forces gathered in secret can mobilize ...

who needed to be forcibly converted and assimilated; but even Jews like the composer Maximilian Steinberg

Maximilian Osseyevich Steinberg (; – 6 December 1946) was a Russian composer of classical music.

Though once considered the hope of Russian music, Steinberg is far less well known today than his mentor (and father-in-law) Nikolai Rimsky-Korsa ...

who attempted to assimilate by converting to Orthodoxy were still regarded with suspicion as potential "infiltrators" supposedly trying to "take over society", while Jews who remained attached to their traditional religion and culture were resented as undesirable aliens.

Resentment towards Jews, for the aforementioned reasons, existed in Russian society, but the idea of a ''Protocols''-esque

Resentment towards Jews, for the aforementioned reasons, existed in Russian society, but the idea of a ''Protocols''-esque international Jewish conspiracy

The international Jewish conspiracy or the world Jewish conspiracy is an antisemitic trope that has been described as "one of the most widespread and long-running conspiracy theories". Although it typically claims that a malevolent, usually gl ...

for world domination was minted in the 1860s. Jacob Brafman

Iakov Aleksandrovich Brafman (; 1825 – 28 December 1879), commonly known as Jacob Brafman, was a Lithuanian Jew from near Minsk, who became notable for converting first to Lutheranism and then the Russian Orthodox Church. He advanced conspir ...

, a Lithuanian Jew from Minsk

Minsk (, ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach (Berezina), Svislach and the now subterranean Nyamiha, Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the administra ...

, had a falling out with agents of the local ''qahal'' and consequently converted to the Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

and authored polemics against the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

and the ''qahal''. Brafman claimed in his books ''The Local and Universal Jewish Brotherhoods'' (1868) and ''The Book of the Kahal'' (1869), published in Vilna

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

, that the ''qahal'' continued to exist in secret and that its principal aim was undermining Orthodox Christian entrepreneurs, taking over their property and ultimately seizing political power. He also claimed that it was an international conspiratorial network, under the central control of the ''Alliance Israélite Universelle

The Alliance israélite universelle (AIU; ; ) is a Paris-based international Jewish organization founded in 1860 with the purpose of safeguarding human rights for Jews around the world. It promotes the ideals of Jewish self-defense and self-suffi ...

'', which was based in Paris and then under the leadership of Adolphe Crémieux

Isaac-Jacob Adolphe Crémieux (; 30 April 1796 – 10 February 1880) was a French lawyer and politician who served as Minister of Justice under the Second Republic (1848) and Government of National Defense (1870–1871). Raised Jewish, he ...

, a prominent freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

. The Vilna Talmudist, Jacob Barit, attempted to refute Brafman's claim.

The impact of Brafman's work took on an international aspect when it was translated into English, French, German and other languages. The image of the "''qahal''" as a secret international Jewish shadow government working as a state within a state

Deep state is a term used for (real or imagined) potential, unauthorized and often secret networks of power operating independently of a state's political leadership in pursuit of their own agendas and goals.

Although the term originated in Turke ...

was picked up by anti-Jewish publications in Russia and was taken seriously by some Russian officials such as P. A. Cherevin and Nikolay Pavlovich Ignatyev who in the 1880s urged governors-general

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

of provinces to seek out the supposed ''qahal''. This was around the time of the Nihilist

Nihilism () encompasses various views that reject certain aspects of existence. There have been different nihilist positions, including the views that life is meaningless, that moral values are baseless, and that knowledge is impossible. Thes ...

Narodnaya Volya

Narodnaya Volya () was a late 19th-century revolutionary socialist political organization operating in the Russian Empire, which conducted assassinations of government officials in an attempt to overthrow the autocratic Tsarist system. The org ...

's assassination of Tsar Alexander II of Russia

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, Congress Poland, King of Poland and Grand Du ...

by bombing and the subsequent pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s. In France, it was translated by Monsignor Ernest Jouin in 1925, who later supported the Protocols. In 1928, Siegfried Passarge, a Far Right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and Nativism (politics), nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on ...

geographer who later gave his support to the Nazis

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

, translated it into German.

Aside from Brafman, there were other early writings which posited a similar concept to the ''Protocols''. This includes ''The Conquest of the World by the Jews'' (1873), published in Basel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

and authored by Osman Bey (born Frederick van Millingen). Millingen was a British subject and son of English physician Julius Michael Millingen, but served as an officer in the army of the Ottoman Empire where he was born. He converted to Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, but later became a Russian Orthodox Christian. Bey's work was followed up by Hippolytus Lutostansky

Hippolytus Lutostansky (1835–1915), also transliterated as Lutostanski, Liutostanskii, J. J. Ljutostanski, Ippolit Iosifovich Lutostanskiĭ; Polish language, Polish: Hipolit Lutostański, was a former Priesthood in the Catholic Church, Catholic ...

's ''The Talmud and the Jews'' (1879) which claimed that Jews wanted to divide Russia among themselves.

Sources employed

Source material for the forgery consisted jointly of '' Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu'' (''Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli andMontesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal so ...

''), an 1864 political satire

Political satire is a type of satire that specializes in gaining entertainment from politics. Political satire can also act as a tool for advancing political arguments in conditions where political speech and dissent are banned.

Political satir ...

by Maurice Joly

Maurice Joly (; 22 September 1829 – 15 July 1878) was a French political writer and lawyer known for '' The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu'', a political satire of Napoleon III.

Known life

Most of the known informat ...

; and a chapter from ''Biarritz'', an 1868 novel by the antisemitic German novelist Hermann Goedsche

Hermann Ottomar Friedrich Goedsche (12 February 1815 – 8 November 1878), also known by his pseudonym Sir John Retcliffe, was a German government employee and author who is remembered mainly for his antisemitism.

Life and work

Goedsche was ...

, which had been translated into Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

in 1872.

Literary forgery

''The Protocols'' is one of the best-known and most-discussed examples ofliterary forgery

Literary forgery (also known as literary mystification, literary fraud or literary hoax) is writing, such as a manuscript or a literary work, which is either deliberately misattributed to a historical or invented author, or is a purported memoir ...

, with analysis and proof of its fraudulent origin dating as far back as 1921. The forgery is an early example of conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

* ...

literature.. Written mainly in the first person plural, the text includes generalization

A generalization is a form of abstraction whereby common properties of specific instances are formulated as general concepts or claims. Generalizations posit the existence of a domain or set of elements, as well as one or more common characteri ...

s, truism

A truism is a claim that is so obvious or self-evident as to be hardly worth mentioning, except as a reminder or as a rhetorical or literary device, and is the opposite of a falsism.

In philosophy, a sentence which asserts incomplete truth con ...

s, and platitude

A platitude is a statement that is seen as trite, meaningless, or prosaic, aimed at quelling social, emotional, or cognitive unease. The statement may be true, but its meaning has been lost due to its excessive use as a thought-terminating clich ...

s on how to take over the world: take control of the media and the financial institutions, change the traditional social order, etc. It does not contain specifics.

Maurice Joly

Numerous parts in the ''Protocols'', in one calculation, some 160 passages, were plagiarized from Joly's political satire ''Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu''. This book was a thinly veiled attack on the political ambitions ofNapoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

, who, represented by Machiavelli,. plots to rule the world. Joly, a republican who later served in the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

, was sentenced to 15 months as a direct result of his book's publication. Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco (5 January 1932 – 19 February 2016) was an Italian Medieval studies, medievalist, philosopher, Semiotics, semiotician, novelist, cultural critic, and political and social commentator. In English, he is best known for his popular ...

considered that ''Dialogue in Hell'' was itself plagiarised in part from a novel by Eugène Sue

Marie-Joseph "Eugène" Sue (; 26 January 18043 August 1857) was a French novelist. He was one of several authors who popularized the genre of the serial novel in France with his very popular and widely imitated '' The Mysteries of Paris'', whi ...

, ''Les Mystères du Peuple'' (1849–56).

Identifiable phrases from Joly constitute 4% of the first half of the first edition, and 12% of the second half; later editions, including most translations, have longer quotes from Joly.

''The Protocols'' 1–19 closely follow the order of Maurice Joly's ''Dialogues'' 1–17. For example:

Philip Graves

Philip Perceval Graves (25 February 1876 – 3 June 1953) was an Anglo-Irish journalist and writer. While working as a foreign correspondent of ''The Times'' in Constantinople, he exposed ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' as an antisemi ...

brought this plagiarism to light in a series of articles in ''The Times'' in 1921, being the first to expose the ''Protocols'' as a forgery to the public.

Hermann Goedsche

Hermann Goedsche was a spy for thePrussian Secret Police

The Prussian Secret Police () was the secret police of Prussia in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In 1851 the Police Union of German States was set up by the police forces of Austria, Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover, Baden, and Württem ...

who was fired from his job as a postal clerk for helping to forge evidence against the democratic leader Benedict Waldeck in 1849. Following his dismissal, Goedsche began a career as a conservative columnist, and wrote literary fiction under the pen name Sir John Retcliffe.. His 1868 novel ''Biarritz'' (''To Sedan'') contains a chapter called " The Jewish Cemetery in Prague and the Council of Representatives of the Twelve Tribes of Israel

The Twelve Tribes of Israel ( , ) are described in the Hebrew Bible as being the descendants of Jacob, a Patriarchs (Bible), Hebrew patriarch who was a son of Isaac and thereby a grandson of Abraham. Jacob, later known as Israel (name), Israel, ...

." In it, Goedsche (who was unaware that only two of the original twelve Biblical "tribes" remained) depicts a clandestine nocturnal meeting of members of a mysterious rabbi

A rabbi (; ) is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi—known as ''semikha''—following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of t ...

nical cabal

A cabal is a group of people who are united in some close design, usually to promote their private views or interests in an ideology, a state (polity), state, or another community, often by Wiktionary:intrigue, intrigue and usually without the kn ...

that is planning a diabolical "Jewish conspiracy." At midnight, the Devil appears to contribute his opinions and insight. The chapter closely resembles a scene in Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

' ''Giuseppe Balsamo'' (1848), in which Joseph Balsamo a.k.a. Alessandro Cagliostro

Giuseppe Balsamo (; 2 June 1743 – 26 August 1795), known by the alias Count Alessandro di Cagliostro ( , ), was an Italian occultist and confidence trickster.

Cagliostro was an Italian adventurer and self-styled magician. He became a gl ...

and company plot the Affair of the Diamond Necklace

The Affair of the Diamond Necklace (, "Affair of the Queen's Necklace") was an incident from 1784 to 1785 at the court of King Louis XVI of France that involved his wife, Queen Marie Antoinette.

The queen's reputation, already tarnished by gossi ...

.

In 1872, a Russian translation of " The Jewish Cemetery in Prague" appeared in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

as a separate pamphlet of purported non-fiction. François Bournand, in his ''Les Juifs et nos Contemporains'' (1896), reproduced the soliloquy at the end of the chapter, in which the character Levit expresses as factual the wish that Jews be "kings of the world in 100 years"—crediting a "Chief Rabbi John Readcliff." Perpetuation of the myth of the authenticity of Goedsche's story, in particular the "Rabbi's speech", facilitated later accounts of the equally mythical authenticity of the ''Protocols''. Like the ''Protocols'', many asserted that the fictional "rabbi's speech" had a ring of authenticity, regardless of its origin: "This speech was published in our time, eighteen years ago," read an 1898 report in '' La Croix'', "and all the events occurring before our eyes were anticipated in it with truly frightening accuracy."

Fictional events in Joly's ''Dialogue aux enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu'', which appeared four years before ''Biarritz'', may well have been the inspiration for Goedsche's fictional midnight meeting, and details of the outcome of the supposed plot. Goedsche's chapter may have been an outright plagiarism of Joly, Dumas père, or both.This complex relationship was originally exposed by . The exposé has since been elaborated in many sources.

Structure and content

The ''Protocols'' purports to document the minutes of a late-19th-century meeting attended by world Jewish leaders, the "Elders of Zion", who are conspiring to control the world. The forgery places in the mouths of the Jewish leaders a variety of plans, most of which derive from older antisemitic canards. For example, the ''Protocols'' includes plans to subvert the morals of the non-Jewish world, plans for Jewish bankers to control the world's economies, plans for Jewish control of the press, and – ultimately – plans for the destruction of civilization. The document consists of 24 "protocols", which have been analyzed by Steven Jacobs and Mark Weitzman, who documented several recurrent themes that appear repeatedly in the 24 protocols, as shown in the following table:Conspiracy references

According toDaniel Pipes

Daniel Pipes (born September 9, 1949) is an American former professor and commentator on foreign policy and the Middle East. He is the president of the Middle East Forum, and publisher of its ''Middle East Quarterly'' journal. His writing focus ...

,

Pipes notes that the ''Protocols'' emphasizes recurring themes of conspiratorial antisemitism: "Jews always scheme", "Jews are everywhere", "Jews are behind every institution", "Jews obey a central authority, the shadowy 'Elders'", and "Jews are close to success."

As fiction in the genre of literature, the tract was analyzed by Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco (5 January 1932 – 19 February 2016) was an Italian Medieval studies, medievalist, philosopher, Semiotics, semiotician, novelist, cultural critic, and political and social commentator. In English, he is best known for his popular ...

in his novel ''Foucault's Pendulum

''Foucault's Pendulum'' (original title: ''Il pendolo di Foucault'' ) is a novel by Italian writer and philosopher Umberto Eco. It was first published in 1988, with an English translation by William Weaver being published a year later.

The bo ...

'' (1988):

Eco also dealt with the ''Protocols'' in 1994 in chapter 6, "Fictional Protocols", of his '' Six Walks in the Fictional Woods'' and in his 2010 novel '' The Cemetery of Prague''.

History

Publication history

The first known mention of ''The Protocols'' was in a 1902 article inSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

's conservative newspaper '' Novoye Vremya'' by journalist Mikhail Osipovich Menshikov. He wrote that a venerable lady of the upper class had suggested he read a small booklet, ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'', which denounced "a conspiracy against the world". Menshikov was strongly skeptical over the authenticity of ''The Protocols'', dismissing their authors and spreaders as "people with brain fever". In 1903, ''The Protocols'' was published as a series of articles in '' Znamya'', a Black Hundreds

The Black Hundreds were reactionary, monarchist, and ultra-nationalist groups in Russia in the early 20th century. They were staunch supporters of the House of Romanov, and opposed any retreat from the autocracy of the reigning monarch. Their na ...

newspaper owned by Pavel Krushevan. It appeared again in 1905 as the final chapter (Chapter XII) of the second edition of ''Velikoe v malom i antikhrist'' ("The Great in the Small & Antichrist

In Christian eschatology, Antichrist (or in broader eschatology, Anti-Messiah) refers to a kind of entity prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ and falsely substitute themselves as a savior in Christ's place before ...

"), a book by Sergei Nilus

Sergei Aleksandrovich Nilus (also ''Sergius'', and variants; ; – 14 January 1929) was a Russian religious writer, self-described mystic, and prolific antisemite.

His book ''Velikoe v malom i antikhrist, kak blizkaja politicheskaja vozmozh ...

. In 1906, it appeared in pamphlet form edited by Georgy Butmi de Katzman.

These first Russian language imprints were used as a tool for scapegoating

Scapegoating is the practice of singling out a person or group for unmerited blame and consequent negative treatment. Scapegoating may be conducted by individuals against individuals (e.g., "he did it, not me!"), individuals against groups (e.g ...

Jews, blamed by the monarchists for the defeat in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

and the Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

. Common to all the texts is the idea that Jews aim for world domination

World domination (also called global domination, world conquest, global conquest, or cosmocracy) is a hypothetical power structure, either achieved or aspired to, in which a single political authority holds power over all or virtually all the i ...

. Since ''The Protocols'' are presented as merely a document

A document is a writing, written, drawing, drawn, presented, or memorialized representation of thought, often the manifestation of nonfiction, non-fictional, as well as fictional, content. The word originates from the Latin ', which denotes ...

, the front matter

Book design is the graphic art of determining the visual and physical characteristics of a book. The design process begins after an author and editor finalize the manuscript, at which point it is passed to the production stage. During productio ...

and back matter

Book design is the graphic art of determining the visual and physical characteristics of a book. The design process begins after an author and editor finalize the manuscript, at which point it is passed to the production stage. During production ...

are needed to explain its alleged origin. The diverse imprints, however, are mutually inconsistent. The general claim is that the document was stolen from a secret Jewish organization. Since the alleged original stolen manuscript does not exist, one is forced to restore a purported original edition. This has been done by the Italian scholar, Cesare G. De Michelis

Cesare G. De Michelis (born 20 April 1944 in Rome) is a scholar and professor of Russian literature at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy.

Biography

He is also an authority on the notorious plagiarism, hoax, and literary forgery known as ...

in 1998, in a work which was translated into English and published in 2004, where he treats his subject as apocrypha

Apocrypha () are biblical or related writings not forming part of the accepted canon of scripture, some of which might be of doubtful authorship or authenticity. In Christianity, the word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to ...

.

In 2020, the Russian historian Ljubov’ Vladimirovna Ul’Janova-Bibikova found a typescript version of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in the manuscripts collections of the Moscow Central Library. The copy included manuscript additions of terms and corrections found in the 1906 version edited by Georgy Butmi. The handwriting is similar to other manuscripts written by Butmi. This typescript copy confirms that the Protocols were written at least in part in Russia, and were not completely written or translated in France. Cesare G. De Michelis

Cesare G. De Michelis (born 20 April 1944 in Rome) is a scholar and professor of Russian literature at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy.

Biography

He is also an authority on the notorious plagiarism, hoax, and literary forgery known as ...

has signalled the importance of the discovery of this typescript.

As the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

unfolded, causing White movement

The White movement,. The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds. also known as the Whites, was one of the main factions of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. It was led mainly by the Right-wing politics, right- ...

–affiliated Russians to flee to the West, this text was carried along and assumed a new purpose. Until then, ''The Protocols'' had remained obscure; it now became an instrument for blaming Jews for the Russian Revolution. It became a tool, a political weapon, used against the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

who were depicted as overwhelmingly Jewish, allegedly executing the "plan" embodied in ''The Protocols''. The purpose was to discredit the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, prevent the West from recognizing the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, and bring about the downfall of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

's regime.

First Russian language editions

The chapter "In the Jewish Cemetery in Prague" from Goedsche's ''Biarritz'', with its strong antisemitic theme containing the alleged rabbinical plot against the European civilization, was translated into Russian as a separate pamphlet in 1872. However, in 1921, PrincessCatherine Radziwill

Princess Catherine Radziwiłł (; 30 March 1858 – 12 May 1941)Schreiner’s book ''Trooper Peter Halkett of Mashonaland'' (1897)

* ''My Recollections'', 1904

* ''Behind the Veil at the Russian Court'', 1914.

* ''The Royal Marriage Market ...

gave a private lecture in New York in which she claimed that the ''Protocols'' were a forgery compiled in 1904–05 by Russian journalists Matvei Golovinski

Matvei Vasilyevich Golovinski (alternatively, Mathieu) () (6 March 1865 – 1920) was a Russian-French writer, journalist and political activist. Critics studying ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' have argued that he was the author of the w ...

and Manasevich-Manuilov at the direction of Pyotr Rachkovsky

Pyotr Ivanovich Rachkovsky (; 1853 – 1 November 1910) was chief of the Okhrana, the secret police of the Russian Empire. He was based in Paris from 1885 to 1902.

Activities in 1880s–1890s

After the assassination of Alexander II of Russia i ...

, Chief of the Russian secret service in Paris.

In 1944, German writer Konrad Heiden identified Golovinski as an author of the ''Protocols''.. Radziwill's account was supported by Russian historian Mikhail Lepekhine, whose claims were published in November 1999 in the French newsweekly ''L'Express

(, stylized in all caps) is a French weekly news magazine headquartered in Paris. The weekly stands at the political centre-right in the French media landscape, and has a lifestyle supplement, ''L'Express Styles'', and a job supplement, ''R� ...

''. Lepekhine considers the ''Protocols'' a part of a scheme to persuade Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II (Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov; 186817 July 1918) or Nikolai II was the last reigning Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 1 November 1894 until his abdication on 15 March 1917. He married ...

that the modernization of Russia was really a Jewish plot to control the world.. Ukrainian scholar Vadim Skuratovsky offers extensive literary, historical and linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

analysis of the original text of the ''Protocols'' and traces the influences of Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian literature, Russian and world literature, and many of his works are consider ...

's prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

(in particular, ''The Grand Inquisitor

"The Grand Inquisitor" (Russian: "Вели́кий инквизи́тор") is a story within a story (called a poem by its fictional author) contained within Fyodor Dostoevsky's 1880 novel ''The Brothers Karamazov.'' It is recited by Ivan Fyodor ...

'' and '' The Possessed'') on Golovinski's writings, including the ''Protocols''.

Golovinski's role in the writing of the ''Protocols'' is disputed by Cesare G. De Michelis

Cesare G. De Michelis (born 20 April 1944 in Rome) is a scholar and professor of Russian literature at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy.

Biography

He is also an authority on the notorious plagiarism, hoax, and literary forgery known as ...

, Michael Hagemeister, and Richard Levy, who each write that the account which involves him is historically unverifiable and to a large extent provably wrong.

In his book ''The Non-Existent Manuscript'', Italian scholar Cesare G. De Michelis

Cesare G. De Michelis (born 20 April 1944 in Rome) is a scholar and professor of Russian literature at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy.

Biography

He is also an authority on the notorious plagiarism, hoax, and literary forgery known as ...

studies early Russian publications of the ''Protocols''. The ''Protocols'' were first mentioned in the Russian press in April 1902, by the Saint Petersburg newspaper ''Novoye Vremya'' ( – ''The New Times''). The article was written by famous conservative publicist as a part of his regular series "Letters to Neighbors" ("Письма к ближним") and was titled "Plots against Humanity". The author described his meeting with a lady ( Yuliana Glinka, as it is known now) who, after telling him about her mystical revelations, implored him to get familiar with the documents later known as the ''Protocols''; but after reading some excerpts, Menshikov became quite skeptical about their origin and did not publish them.

Krushevan and Nilus editions

The ''Protocols'' were published at the earliest, in serialized form, from August 28 to September 7 ( O.S.) 1903, in '' Znamya'', a Saint Petersburg daily newspaper, under Pavel Krushevan. Krushevan had initiated theKishinev pogrom

The Kishinev pogrom or Kishinev massacre was an anti-Jewish riot that took place in Kishinev (modern Chișinău, Moldova), then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate in the Russian Empire, on . During the pogrom, which began on Easter Day, ...

four months earlier..

In 1905, Sergei Nilus published the full text of the ''Protocols'' in ''Chapter XII'', the final chapter (pp. 305–417), of the second edition (or third, according to some sources) of his book, '' Velikoe v malom i antikhrist'', which translates as "The Great within the Small and the Antichrist". He claimed it was the work of the First Zionist Congress

The First Zionist Congress () was the inaugural congress of the Zionist Organization, Zionist Organization (ZO) held in the Stadtcasino Basel in the city of Basel on August 29–31, 1897. Two hundred and eight delegates from 17 countries and 2 ...

, held in 1897 in Basel, Switzerland

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's third-most-populous city (after Zurich and Geneva), with ...

. When it was pointed out that the First Zionist Congress had been open to the public and was attended by many non-Jews, Nilus changed his story, saying the Protocols were the work of the 1902–03 meetings of the Elders, but contradicting his own prior statement that he had received his copy in 1901:

Stolypin's fraud investigation, 1905

A subsequent secret investigation ordered byPyotr Stolypin

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, Пётр Аркадьевич Столыпин, p=pʲɵtr ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn; – ) was a Russian statesman who served as the third Prime Minister of Russia, prime minister and the Ministry ...

, the newly appointed chairman of the Council of Ministers, came to the conclusion that the ''Protocols'' first appeared in Paris in antisemitic circles around 1897–98. When Nicholas II

Nicholas II (Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov; 186817 July 1918) or Nikolai II was the last reigning Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 1 November 1894 until his abdication on 15 March 1917. He married ...

learned of the results of this investigation, he requested, "The Protocols should be confiscated, a good cause cannot be defended by dirty means.". Despite the order, or because of the "good cause", numerous reprints proliferated. Nicholas later read the ''Protocols'' to his family during their imprisonment.

''The Protocols'' in the West

In January 1920,Eyre & Spottiswoode

Eyre & Spottiswoode was the London-based printing firm established in 1739 that was the King's Printer, and subsequently, a publisher prior to being incorporated; it once went by the name of Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & co. ltd. In April 1929, it ...

published the first English translation of ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' in Britain. According to a letter written by art historian Robert Hobart Cust, the pamphlet had been translated, prepared, and paid for by George Shanks

George Shanks (1896–1957) was an expatriate British people, Briton born in Moscow and was the first translator of ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Protocols of Zion'' from Russian into English. He was also a founding member of Radio Norma ...

and their mutual friend, Major Edward Griffiths George Burdon, who was serving as Secretary of the ''United Russia Societies Association'' at that time. In an edition of Lord Alfred Douglas

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 1870 – 20 March 1945), also known as Bosie Douglas, was an English poet and journalist, and a lover of Oscar Wilde. At Oxford University he edited an undergraduate journal, ''The Spirit Lamp'', that carr ...

’ ''Plain English'' journal dated January 1921, it is claimed that Shanks, a former officer in the Royal Navy Air Service and the Russian Government Committee in Kingsway, London, had found post-war employment in the Chief Whip's Office at 12 Downing Street, before being offered a position as Personal Secretary to Sir Philip Sassoon

Sir Philip Albert Gustave David Sassoon, 3rd Baronet (4 December 1888 – 3 June 1939) was a British politician and aristocrat. He served as a staff officer during the First World War, from July 1914 to November 1918.

Family

Sassoon was a member ...

, at that time serving as Private Secretary to British Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

in Britain's Coalition Government.

In the United States, ''The Protocols'' are to be understood in the context of the

In the United States, ''The Protocols'' are to be understood in the context of the First Red Scare

The first Red Scare was a period during History of the United States (1918–1945), the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of Far-left politics, far-left movements, including Bolsheviks, Bolshevism a ...

(1917–20). The text was purportedly brought to the United States by a Russian Army officer in 1917; it was translated into English by Natalie de Bogory (personal assistant of Harris A. Houghton, an officer of the Department of War) in June 1918, and Russian expatriate Boris Brasol soon circulated it in American government circles, specifically diplomatic and military, in typescript form, a copy of which is archived by the Hoover Institute.

On October 27 and 28, 1919, the Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

'' Public Ledger'' published excerpts of an English language translation as the "Red Bible," deleting all references to the purported Jewish authorship and re-casting the document as a Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

manifesto

A manifesto is a written declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party, or government. A manifesto can accept a previously published opinion or public consensus, but many prominent ...

. The author of the articles was the paper's correspondent

A correspondent or on-the-scene reporter is usually a journalist or commentator for a magazine, or an agent who contributes reports to a newspaper, or radio or television news, or another type of company, from a remote, often distant, locati ...

at the time, Carl W. Ackerman

Carl William Ackerman (January 16, 1890 in Richmond, Indiana – October 9, 1970 in New York City) was an American journalist, author and educational administrator, the first dean of the Columbia School of Journalism. In 1919, as a correspondent ...

, who later became the head of the journalism department at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

.

In 1923, there appeared an anonymously edited pamphlet by the Britons Publishing Society

Britons Publishing Society, founded in 1923, was an offshoot of The Britons. According to scholar Gisela C. Lebzelter, The Britons split because:

... internal disagreements proved paralysing. Seven members were excluded in November 1923, and ...

, a successor to The Britons

The Britons was an English anti-Semitic and anti-immigration organisation founded in July 1919 by Henry Hamilton Beamish and John Henry Clarke. The organisation published pamphlets and propaganda under the names Judaic Publishing Co. and late ...

, an entity created and headed by Henry Hamilton Beamish

Henry Hamilton Beamish (2 June 1873 – 27 March 1948) was a leading British antisemitic journalist and the founder of The Britons in 1919, the first organisation set up in Britain for the express purpose of diffusing antisemitic propaganda. Af ...

. This imprint was allegedly a translation by Victor E. Marsden, who had died in October 1920.

On May 8, 1920, an article in ''The Times'' followed German translation and appealed for an inquiry into what it called an "uncanny note of prophecy". In the leader (editorial) titled "The Jewish Peril, a Disturbing Pamphlet: Call for Inquiry", Wickham Steed

Henry Wickham Steed (10 October 1871 – 13 January 1956) was an English journalist and historian. He was editor of ''The Times'' from 1919 to 1922.

Early life

Born in Long Melford, England, Steed was educated at Sudbury Grammar School ...

wrote about ''The Protocols'':

Steed retracted his endorsement of ''The Protocols'' after they were exposed as a forgery.

United States

For nearly two years starting in 1920, the American industrialistHenry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

published in a newspaper he owned—'' The Dearborn Independent''—a series of antisemitic articles that quoted liberally from the Protocols. The actual author of the articles is generally believed to have been the newspaper's editor William J. Cameron. During 1922, the circulation of the Dearborn Independent grew to almost 270,000 paid copies. Ford later published a compilation of the articles in book form as " The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem". In 1921, Ford cited evidence of a Jewish threat: "The only statement I care to make about the ''Protocols'' is that they fit in with what is going on. They are 16 years old, and they have fitted the world situation up to this time.". Robert A. Rosenbaum wrote that "In 1927, bowing to legal and economic pressure, Ford issued a retraction and apology—while disclaiming personal responsibility—for the anti-Semitic articles and closed the ''Dearborn Independent''". Ford was an admirer of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

..

In 1934, an anonymous editor expanded the compilation with "Text and Commentary" (pp 136–141). The production of this uncredited compilation was a 300-page book, an inauthentic expanded edition of the twelfth chapter of Nilus's 1905 book on the coming of the anti-Christ

In Christian eschatology, Antichrist (or in broader eschatology, Anti-Messiah) refers to a kind of entity prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ and falsely substitute themselves as a savior in Christ's place before ...

. It consists of substantial liftings of excerpts of articles from Ford's antisemitic periodical ''The Dearborn Independent''. This 1934 text circulates most widely in the English-speaking world, as well as on the internet. The "Text and Commentary" concludes with a comment on Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( ; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born Israeli statesman, biochemist, and Zionist leader who served as president of the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organization and later as the first pre ...

's October 6, 1920, remark at a banquet: "A beneficent protection which God has instituted in the life of the Jew is that He has dispersed him all over the world". Marsden, who was dead by then, is credited with the following assertion:

''The Times'' exposes a forgery, 1921

In 1920–1921, the history of the concepts found in the ''Protocols'' was traced back to the works of Goedsche and Jacques Crétineau-Joly by

In 1920–1921, the history of the concepts found in the ''Protocols'' was traced back to the works of Goedsche and Jacques Crétineau-Joly by Lucien Wolf

Lucien Wolf (20 January 1857 in London23 August 1930) was an English Jewish journalist, diplomat, historian, and advocate of rights for Jews and other minorities. While Wolf was devoted to minority rights, he opposed Jewish nationalism as expres ...

(an English Jewish journalist), and published in London in August 1921. Then an exposé occurred in the series of articles in ''The Times'' by its Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

reporter, Philip Graves

Philip Perceval Graves (25 February 1876 – 3 June 1953) was an Anglo-Irish journalist and writer. While working as a foreign correspondent of ''The Times'' in Constantinople, he exposed ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' as an antisemi ...

, who discovered the plagiarism from the work of Maurice Joly

Maurice Joly (; 22 September 1829 – 15 July 1878) was a French political writer and lawyer known for '' The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu'', a political satire of Napoleon III.

Known life

Most of the known informat ...

.

According to writer Peter Grose, Allen Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles ( ; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was an American lawyer who was the first civilian director of central intelligence (DCI), and its longest serving director. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the ea ...

, who was in Constantinople developing relationships in post- Ottoman political structures, discovered "the source" of the documentation and ultimately provided him to ''The Times''. Grose writes that ''The Times'' extended a loan to the source, a Russian émigré who refused to be identified, with the understanding the loan would not be repaid. Colin Holmes, a lecturer in economic history at Sheffield University

The University of Sheffield (informally Sheffield University or TUOS) is a public research university in Sheffield, South Yorkshire, England. Its history traces back to the foundation of Sheffield Medical School in 1828, Firth College in 1879 ...

, identified the émigré as Mikhail Raslovlev, a self-identified antisemite, who gave the information to Graves so as not to "give a weapon of any kind to the Jews, whose friend I have never been."

In the first article of Graves' series, titled "A Literary Forgery", the editors of ''The Times'' wrote, "our Constantinople Correspondent presents for the first time conclusive proof that the document is in the main a clumsy plagiarism. He has forwarded us a copy of the French book from which the plagiarism is made." In the same year, an entire book documenting the hoax was published in the United States by Herman Bernstein

Herman Bernstein (, September 21, 1876 – August 31, 1935) was an American journalist, poet, novelist, playwright, translator, Jewish activist, and diplomat. He was the United States Ambassador to Albania and was the founder of '' Der Tog'', th ...

. Despite this widespread and extensive debunking, the ''Protocols'' continued to be regarded as important factual evidence by antisemites. Dulles, a successful lawyer and career diplomat, attempted to persuade the US State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

to publicly denounce the forgery, but without success.

Switzerland

Berne Trial, 1934–35

The selling of the ''Protocols'' (edited by German antisemiteTheodor Fritsch

Theodor Fritsch (born Emil Theodor Fritsche; 28 October 1852 – 8 September 1933) was a German publisher and journalist. His antisemitic writings did much to influence popular German opinion against Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centur ...

) by the National Front during a political meeting in the Casino of Bern on June 13, 1933, led to the Berne Trial in the ''Amtsgericht'' (district court) of Bern

Bern (), or Berne (), ; ; ; . is the ''de facto'' Capital city, capital of Switzerland, referred to as the "federal city".; ; ; . According to the Swiss constitution, the Swiss Confederation intentionally has no "capital", but Bern has gov ...

, the capital of Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, on October 29, 1934. The plaintiffs (the Swiss Jewish Association and the Jewish Community of Bern) were represented by Hans Matti and Georges Brunschvig, helped by Emil Raas. Working on behalf of the defense was German antisemitic propagandist Ulrich Fleischhauer

Ulrich Fleischhauer (14 July 1876 – 20 October 1960) (Pseudonyms ''Ulrich Bodung'', and ''Israel Fryman'') was a leading publisher of antisemitic books and news articles reporting on a perceived Judeo-Masonic conspiracy theory and "nefarious ...

. On May 19, 1935, two defendants (Theodore Fischer and Silvio Schnell) were convicted of violating a Bernese statute prohibiting the distribution of "immoral, obscene or brutalizing" texts while three other defendants were acquitted. The court declared the ''Protocols'' to be forgeries, plagiarisms, and obscene literature. Judge Walter Meyer, a Christian who had not previously heard of the ''Protocols'', said in conclusion,

Vladimir Burtsev, a Russian émigré, anti-Bolshevik and anti-Fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

who exposed numerous Okhrana

The Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order (), usually called the Guard Department () and commonly abbreviated in modern English sources as the Okhrana ( rus , Охрана, p=ɐˈxranə, a=Ru-охрана.ogg, t= The Guard) w ...

agents provocateurs

An is a person who actively entices another person to commit a crime that would not otherwise have been committed and then reports the person to the authorities. They may target individuals or groups.

In jurisdictions in which conspiracy is a ...

in the early 1900s, served as a witness at the Berne Trial. In 1938 in Paris he published a book, ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: A Proved Forgery'', based on his testimony.

On November 1, 1937, the defendants appealed the verdict to the ''Obergericht'' (Cantonal Supreme Court) of Bern. A panel of three judges acquitted them, holding that the ''Protocols'', while false, did not violate the statute at issue because they were "political publications" and not "immoral (obscene) publications (Schundliteratur)" in the strict sense of the law. The presiding judge's opinion stated, though, that the forgery of the ''Protocols'' was not questionable and expressed regret that the law did not provide adequate protection for Jews from this sort of literature. The court refused to impose the fees of defense of the acquitted defendants to the plaintiffs, and the acquitted Theodor Fischer had to pay 100 Fr. to the total state costs of the trial (Fr. 28,000) that were eventually paid by the canton of Bern

The canton of Bern, or Berne (; ; ; ), is one of the Canton of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. Its capital city, Bern, is also the ''de facto'' capital of Switzerland. The bear is the heraldic symbol of the c ...

. This decision gave grounds for later allegations that the appeal court "confirmed authenticity of the Protocols" which is contrary to the facts.

Evidence presented at the trial, which strongly influenced later accounts up to the present, was that the ''Protocols'' were originally written in French by agents of the Tzarist secret police (the Okhrana). However, this version has been questioned by several modern scholars. Michael Hagemeister discovered that the primary witness Alexandre du Chayla had previously written in support of the

Evidence presented at the trial, which strongly influenced later accounts up to the present, was that the ''Protocols'' were originally written in French by agents of the Tzarist secret police (the Okhrana). However, this version has been questioned by several modern scholars. Michael Hagemeister discovered that the primary witness Alexandre du Chayla had previously written in support of the blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mu ...

, had received four thousand Swiss francs for his testimony, and was secretly doubted even by the plaintiffs. Charles Ruud and Sergei Stepanov concluded that there is no substantial evidence of Okhrana involvement and strong circumstantial evidence against it.

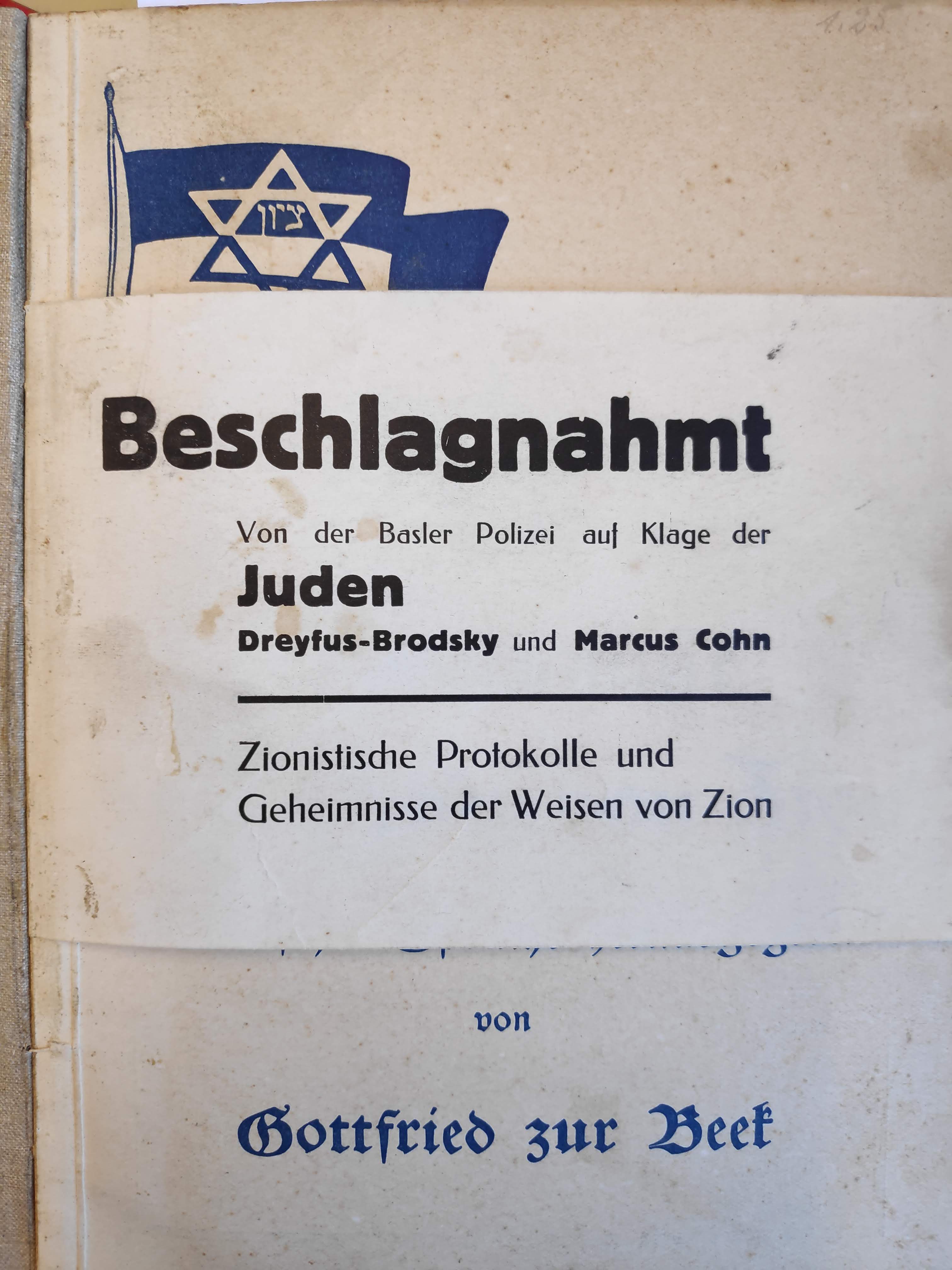

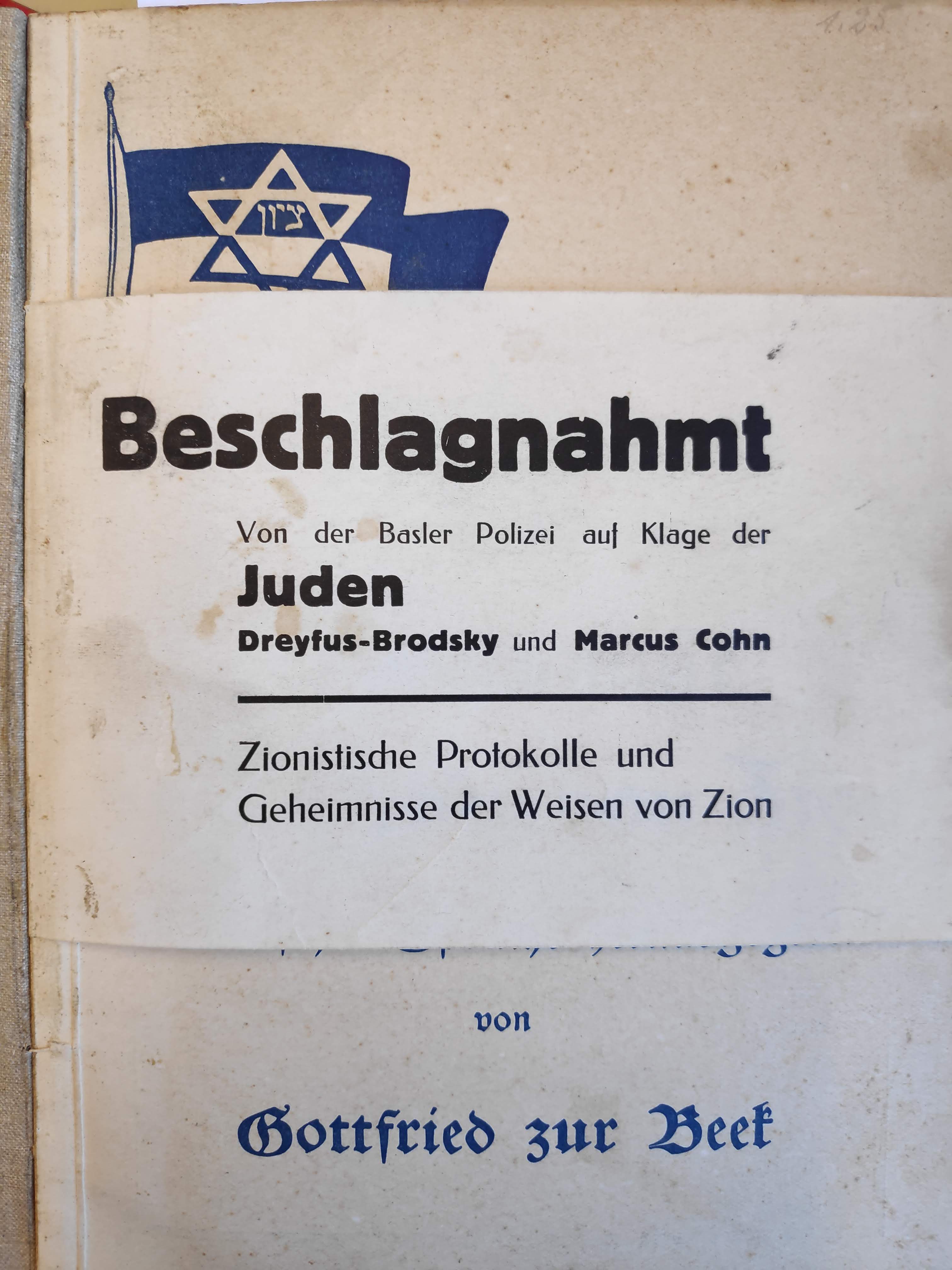

Basel Trial

A similar trial in Switzerland took place inBasel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

. The Swiss Frontists Alfred Zander and Eduard Rüegsegger distributed the ''Protocols'' (edited by the German Gottfried zur Beek) in Switzerland. Jules Dreyfus-Brodsky and Marcus Cohen sued them for insult to Jewish honour. At the same time, chief rabbi Marcus Ehrenpreis of Stockholm (who also witnessed at the Berne Trial) sued Alfred Zander who contended that Ehrenpreis himself had said that the ''Protocols'' were authentic (referring to the foreword of the edition of the ''Protocols'' by the German antisemite Theodor Fritsch). On June 5, 1936, these proceedings ended with a settlement.

Finland

The first Finnish edition of the Protocols was published in Swedish in 1919. In 1920, the protocols were published in Finnish as "''The Jewish Secret Program''“. Four additional editions of the Swedish edition were quickly published, and the Finnish edition was re-released in 1933 under the title "''The Scourge of Nations''“. Another edition of the Protocols was published by the Nazi group Blue Cross in 1943. The Party of Finnish Labor also published their edition of the Protocols translated by party secretary Taavi Vanhanen. Pekka Siitoin's Patriotic Popular Front published a new edition in the 1970s.Fasismia, terrorismia vai nallipyssynatsien leikkiä? Julkinen keskustelu Isänmaallisen Kansanrintaman toiminnasta loppuvuodesta 1977 Piipponen, Marko ; Yhteiskuntatieteiden ja kauppatieteiden tiedekunta, Historia- ja maantieteiden laitos ; Faculty of Social Sciences and Business, Department of Geographical and Historical Sciences In the 2000s, the Protocols has been published by theMagneettimedia

''Magneettimedia'' is a Finnish free newspaper, free and online newspaper. It was initially published by retail chain J. Kärkkäinen but currently it is published by Pohjoinen perinne, a society linked with the Finnish Resistance Movement.Leppävu ...

. In the 2020s, the Protocols have been republished by a pseudonymous individual suspected of being a researcher in University of Helsinki

The University of Helsinki (, ; UH) is a public university in Helsinki, Finland. The university was founded in Turku in 1640 as the Royal Academy of Åbo under the Swedish Empire, and moved to Helsinki in 1828 under the sponsorship of Alexander ...

according to Demokraatti.

The State Police

State police, provincial police or regional police are a type of sub-national territorial police force found in nations organized as federations, typically in North America, South Asia, and Oceania. These forces typically have jurisdiction o ...

had copies of the Protocols in its libraries available to those wishing to read them, along with other antisemitic books. It is unknown if the Protocols was officially considered legitimate, but the chief of the State Police Ossi Holmström subscribed to the Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy theory.

Germany

According to historianNorman Cohn

Norman Rufus Colin Cohn FBA (12 January 1915 – 31 July 2007) was a British academic, historian and writer who spent 14 years as a professorial fellow and as Astor-Wolfson Professor at the University of Sussex.

Life

Cohn was born in London, ...

, the assassins of German Jewish politician Walther Rathenau

Walther Rathenau (; 29 September 1867 – 24 June 1922) was a German industrialist, writer and politician who served as foreign minister of Germany from February 1922 until his assassination in June 1922.

Rathenau was one of Germany's leading ...

(1867–1922) were convinced that Rathenau was a literal "Elder of Zion".

It seems likely Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

first became aware of the ''Protocols'' after hearing about it from ethnic German white émigrés

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wavelen ...

, such as Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ...

and Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter

Ludwig Maximilian Erwin von Scheubner-Richter ( Latvian: ''Ludvigs Rihters'') ( – 9 November 1923) was a Baltic German chemist, officer, political activist and an influential early member of the Nazi Party.

Scheubner-Richter was a Balt ...

. Rosenberg and Scheubner-Richter were also members of the early Aufbau Vereinigung

The Wirtschaftliche Aufbau-Vereinigung (Economic Reconstruction Organization) was a Munich-based counterrevolutionary conspiratorial group formed in the aftermath of the German occupation of Ukraine in 1918 and of the Latvian Intervention of 19 ...

counterrevolutionary group, which according to historian Michael Kellogg, influenced the Nazis in promulgating a ''Protocols''-like myth.

Hitler refers to the ''Protocols'' in ''Mein Kampf

(; ) is a 1925 Autobiography, autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The book outlines many of Political views of Adolf Hitler, Hitler's political beliefs, his political ideology and future plans for Nazi Germany, Ge ...

'':

The ''Protocols'' also became a part of the Nazi propaganda effort to justify persecution of the Jews. In ''The Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

: The Destruction of European Jewry 1933–1945'', Nora Levin states that "Hitler used the Protocols as a manual in his war to exterminate the Jews":

Hitler did not mention the Protocols in his speeches after his defense of it in ''Mein Kampf''. "Distillations of the text appeared in German classrooms, indoctrinated the Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth ( , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth wing of the German Nazi Party. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. From 1936 until 1945, it was th ...

, and invaded the USSR along with German soldiers." Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and philologist who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief Propaganda in Nazi Germany, propagandist for the Nazi Party, and ...

proclaimed: "The Zionist Protocols are as up-to-date today as they were the day they were first published."

Richard S. Levy criticizes the claim that the ''Protocols'' had a large effect on Hitler's thinking, writing that it is based mostly on suspect testimony and lacks hard evidence. Randall Bytwerk agrees, writing that most leading Nazis did not believe it was genuine despite having an "inner truth" suitable for propaganda.

Publication of the ''Protocols'' was stopped in Germany in 1939 for unknown reasons. An edition that was ready for printing was blocked by censorship laws.

German-language publications

Having fled Ukraine in 1918–19, Piotr Shabelsky-Bork brought the ''Protocols'' to Ludwig Müller von Hausen who then published them in German. Under the pseudonym Gottfried zur Beek he produced the first and "by far the most important" German translation. It appeared in January 1920 as a part of a larger antisemitic tract dated 1919. After ''The Times'' discussed the book respectfully in May 1920 it became a bestseller. Alfred Rosenberg's 1923 analysis "gave a forgery a huge boost".Italy

Fascist politicianGiovanni Preziosi

Giovanni Preziosi (24 October 1881 – 26 April 1945) was an Italian fascist politician noted for his contributions to Fascist Italy.

Early life and career

Preziosi was born on 24 October 1881 in Torella dei Lombardi into a middle-class fami ...

published the first Italian edition of the ''Protocols'' in 1921. The book however had little impact until the mid-1930s. A new 1937 edition had a much higher impact, and three further editions in the following months sold 60,000 copies total. The fifth edition had an introduction by Julius Evola

Giulio Cesare Andrea "Julius" Evola (; 19 May 1898 – 11 June 1974) was an Italian far-right philosopher and writer. Evola regarded his values as Traditionalist conservatism, traditionalist, Aristocracy, aristocratic, War, martial and Empire, im ...

, which argued around the issue of forgery, stating: "The problem of the authenticity of this document is secondary and has to be replaced by the much more serious and essential problem of its truthfulness".

Post–World War II

Middle East

Neither governments nor political leaders in most parts of the world have referred to the ''Protocols'' sinceWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The exception to this is the Middle East, where a large number of Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

and Muslim regimes and leaders have endorsed them as authentic, including endorsements from Presidents Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

and Anwar Sadat

Muhammad Anwar es-Sadat (25 December 1918 – 6 October 1981) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the third president of Egypt, from 15 October 1970 until Assassination of Anwar Sadat, his assassination by fundame ...

of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, President Abdul Salam Arif

Abdul Salam Mohammed ʿArif Al-Jumaili ('; 21 March 1921 – 13 April 1966) was an Iraqi military officer and politician who served as the second president of Iraq from 1963 until his death in a plane crash in 1966. He played a leading role in ...

of Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, King Faisal of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

, and Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi