Proto SF on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

Ancient

Ancient  One frequently cited text is the Syrian-Greek writer

One frequently cited text is the Syrian-Greek writer  The early Japanese tale of involves traveling forwards in time to a distant future, and was first described in the ''

The early Japanese tale of involves traveling forwards in time to a distant future, and was first described in the ''

"The Ebony Horse" features a robot in the form of a flying mechanical horse controlled using keys, that could fly into outer space and towards the Sun, while the "Third Qalandar's Tale" also features a robot in the form of an uncanny

"The Ebony Horse" features a robot in the form of a flying mechanical horse controlled using keys, that could fly into outer space and towards the Sun, while the "Third Qalandar's Tale" also features a robot in the form of an uncanny

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the so-called "

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the so-called "

literary genre

A literary genre is a category of literature. Genres may be determined by List of narrative techniques, literary technique, Tone (literature), tone, Media (communication), content, or length (especially for fiction). They generally move from mor ...

of science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may include information technology and robotics, biological manipulations, space ...

is diverse, and its exact definition remains a contested question among both scholars and devotees. This lack of consensus is reflected in debates about the genre's history, particularly over determining its exact origins. There are two broad camps of thought, one that identifies the genre's roots in early fantastical works such as the Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

ian ''Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poetry, epic from ancient Mesopotamia. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with five Sumerian language, Sumerian poems about Gilgamesh (formerly read as Sumerian "Bilgames"), king of Uruk, some of ...

'' (earliest Sumerian text versions c. 2150–2000 BCE). A second approach argues that science fiction only became possible sometime between the 17th and early 19th centuries, following the scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

and major discoveries in astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, and mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

.

Science fiction developed and boomed in the 20th century, as the deep integration of science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

and invention

An invention is a unique or novelty (patent), novel machine, device, Method_(patent), method, composition, idea, or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It m ...

s into daily life encouraged a greater interest in literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

that explores the relationship between technology

Technology is the application of Conceptual model, conceptual knowledge to achieve practical goals, especially in a reproducible way. The word ''technology'' can also mean the products resulting from such efforts, including both tangible too ...

, society, and the individual. Scholar Robert Scholes

Robert E. Scholes (1929 – December 9, 2016) was an American literary critic and theorist. He is known for his ideas on fabulation and metafiction.

Education and career

Robert Scholes was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1929. After taking h ...

calls the history of science fiction "the history of humanity's changing attitudes toward space and time ... the history of our growing understanding of the universe and the position of our species in that universe". In recent decades, the genre has diversified and become firmly established as a major influence on global culture and thought.

Early science fiction

Ancient and early modern precursors

One of the earliest and most commonly-cited texts for those looking for early precursors to science fiction is the ancient Mesopotamian ''Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poetry, epic from ancient Mesopotamia. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with five Sumerian language, Sumerian poems about Gilgamesh (formerly read as Sumerian "Bilgames"), king of Uruk, some of ...

'', with the earliest text versions identified as being from about 2000 BCE. American science fiction author Lester del Rey

Lester del Rey (June 2, 1915 – May 10, 1993) was an American science fiction author and editor. He was the author of many books in the juvenile Winston Science Fiction series, and the fantasy editor at Del Rey Books, the fantasy an ...

was one such supporter of using Gilgamesh as an origin point, arguing that "science fiction is precisely as old as the first recorded fiction. That is ''The Epic of Gilgamesh''." French science fiction writer Pierre Versins also argued that ''Gilgamesh'' was the first science fiction work due to its treatment of human reason and the quest for immortality. In addition, ''Gilgamesh'' features a flood scene that in some ways resembles a work of apocalyptic science fiction. However, the lack of explicit science or technology in the work has led some to argue that it is better categorized as fantastic literature.

Ancient

Ancient Indian poetry

Indian poetry and Indian literature in general, has a long history dating back to Vedic times. They were written in various Indian languages such as Vedic Sanskrit, Classical Sanskrit, Ancient Meitei, Modern Meitei, Telugu, Tamil, Odia ...

such as the Hindu epic the ''Ramayana

The ''Ramayana'' (; ), also known as ''Valmiki Ramayana'', as traditionally attributed to Valmiki, is a smriti text (also described as a Sanskrit literature, Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epic) from ancient India, one of the two important epics ...

'' (5th to 4th century BCE) includes Vimana

Vimāna are mythological flying palaces or chariots described in Hindu texts and Sanskrit epics. The "Pushpaka Vimana" of Ravana (who took it from Kubera; Rama returned it to Kubera) is the most quoted example of a vimana. Vimanas are also menti ...

, flying machines able to travel into space or under water, and destroy entire cities using advanced weapons. In the first book of the ''Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' (, , from wikt:ऋच्, ऋच्, "praise" and wikt:वेद, वेद, "knowledge") is an ancient Indian Miscellany, collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canoni ...

'' collection of Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

hymns (1700–1100 BCE), there is a description of "mechanical birds" that are seen "jumping into space speedily with a craft using fire and water ... containing twelve stamghas (pillars), one wheel, three machines, 300 pivots, and 60 instruments".

The ancient Hindu mythological epic the ''Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; , , ) is one of the two major Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epics of ancient India revered as Smriti texts in Hinduism, the other being the ''Ramayana, Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the events and aftermath of the Kuru ...

'' (8th and 9th centuries BCE) includes the story of King Kakudmi

Kakudmi (), also called Raivata ( meaning ''son of Revata''), is a king featured in Hindu literature. Kakudmi is described to be the king of Kushasthali. He is the son of Revata, and the father of Revati, the consort of the deity Balarama. Hi ...

, who travels to heaven to meet the creator Brahma

Brahma (, ) is a Hindu god, referred to as "the Creator" within the Trimurti, the triple deity, trinity of Para Brahman, supreme divinity that includes Vishnu and Shiva.Jan Gonda (1969)The Hindu Trinity, Anthropos, Bd 63/64, H 1/2, pp. 212– ...

and is shocked to learn that many ages have passed when he returns to Earth, anticipating the concept of time travel

Time travel is the hypothetical activity of traveling into the past or future. Time travel is a concept in philosophy and fiction, particularly science fiction. In fiction, time travel is typically achieved through the use of a device known a ...

.

One frequently cited text is the Syrian-Greek writer

One frequently cited text is the Syrian-Greek writer Lucian of Samosata

Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανὸς ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syria (region), Syrian satire, satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with whi ...

's 2nd-century satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of exposin ...

''True History

''A True Story'' (, ''Alēthē diēgēmata''; or ), also translated as ''True History'', is a long novella or short novel written in the second century AD by the Syrian author Lucian of Samosata. The novel is a satire of outlandish tales that h ...

'', which uses a voyage to outer space and conversations with alien life forms to comment on the use of exaggeration

Exaggeration is the representation of something as more extreme or dramatic than it is, intentionally or unintentionally. It can be a rhetorical device or figure of speech, used to evoke strong feelings or to create a strong impression.

Ampl ...

within travel literature

The genre of travel literature or travelogue encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

History

Early examples of travel literature include the '' Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' (generally considered a ...

and debate

Debate is a process that involves formal discourse, discussion, and oral addresses on a particular topic or collection of topics, often with a moderator and an audience. In a debate, arguments are put forward for opposing viewpoints. Historica ...

s. Typical science fiction themes and topoi

In mathematics, a topos (, ; plural topoi or , or toposes) is a category that behaves like the category of sheaves of sets on a topological space (or more generally, on a site). Topoi behave much like the category of sets and possess a notion ...

in ''True History'' include travel to outer space, encounter with alien life-forms (including the experience of a first encounter event), interplanetary warfare and planetary imperialism, motif of , creatures as products of human technology, worlds working by a set of alternative physical laws

Scientific laws or laws of science are statements, based on reproducibility, repeated experiments or observations, that describe or prediction, predict a range of natural phenomena. The term ''law'' has diverse usage in many cases (approximate, a ...

, and an explicit desire of the protagonist for exploration and adventure. In witnessing one interplanetary battle between the People of the Moon and the People of the Sun as the fight for the right to colonize the Morning Star

Morning Star, morning star, or Morningstar may refer to:

Astronomy

* Morning star, most commonly used as a name for the planet Venus when it appears in the east before sunrise

** See also Venus in culture

* Morning star, a name for the star Siri ...

, Lucian describes giant space spiders who were "appointed to spin a web in the air between the Moon and the Morning Star, which was done in an instant, and made a plain campaign upon which the foot forces were planted". L. Sprague de Camp

Lyon Sprague de Camp (; November 27, 1907 – November 6, 2000) was an American author of science fiction, Fantasy literature, fantasy and non-fiction literature. In a career spanning 60 years, he wrote over 100 books, both novels and works of ...

and a number of other authors argue this to be one of the earliest if not the earliest example of science fiction or proto-science fiction. However, since the text was intended to be explicitly satirical and hyperbolic, other critics are ambivalent about its rightful place as a science fiction precursor. For example, English critic Kingsley Amis

Sir Kingsley William Amis (16 April 1922 – 22 October 1995) was an English novelist, poet, critic and teacher. He wrote more than 20 novels, six volumes of poetry, a memoir, short stories, radio and television scripts, and works of social crit ...

wrote that "It is hardly science-fiction, since it deliberately piles extravagance upon extravagance for comic effect" yet he implicitly acknowledged its SF character by comparing its plot to early 20th-century space opera

Space opera is a subgenre of science fiction that emphasizes Space warfare in science fiction, space warfare, with use of melodramatic, risk-taking space adventures, relationships, and chivalric romance. Set mainly or entirely in outer space, i ...

s: "I will merely remark that the sprightliness and sophistication of ''True History'' make it read like a joke at the expense of nearly all early-modern science fiction, that written between, say, 1910 and 1940." Lucian translator Bryan Reardon is more explicit, describing the work as "an account of a fantastic journey – to the moon, the underworld, the belly of a whale, and so forth. It is not really science fiction, although it has sometimes been called that; there is no 'science' in it."

The early Japanese tale of involves traveling forwards in time to a distant future, and was first described in the ''

The early Japanese tale of involves traveling forwards in time to a distant future, and was first described in the ''Nihongi

The or , sometimes translated as ''The Chronicles of Japan'', is the second-oldest book of classical Japanese history. It is more elaborate and detailed than the , the oldest, and has proven to be an important tool for historians and archaeol ...

'' (written in 720). It was about a young fisherman named Urashima Tarō who visits an undersea palace and stays there for three days. After returning home to his village, he finds himself 300 years in the future, where he is long forgotten, his house is in ruins, and his family long dead. The 10th-century Japanese narrative ''The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter

is a (fictional prose narrative) containing elements of Japanese folklore. Written by an unknown author in the late 9th or early 10th century during the Heian period, it is considered the oldest surviving work in the form.

The story details ...

'' may also be considered proto-science fiction. The protagonist of the story, Kaguya-hime

is the Japanese word for princess or a lady of higher birth. Daughters of a monarch are actually referred to by other terms, e.g. , literally king's daughter, even though ''Hime'' can be used to address ''Ōjo''.

The word ''Hime'' initially ...

, is a princess from the Moon who is sent to Earth for safety during a celestial war, and is found and raised by a bamboo cutter in Japan. She is later taken back to the Moon by her real extraterrestrial family. A manuscript illustration depicts a round flying machine similar to a flying saucer

A flying saucer, or flying disc, is a purported type of disc-shaped unidentified flying object (UFO). The term was coined in 1947 by the United States (US) news media for the objects pilot Kenneth Arnold UFO sighting, Kenneth Arnold claimed fl ...

.

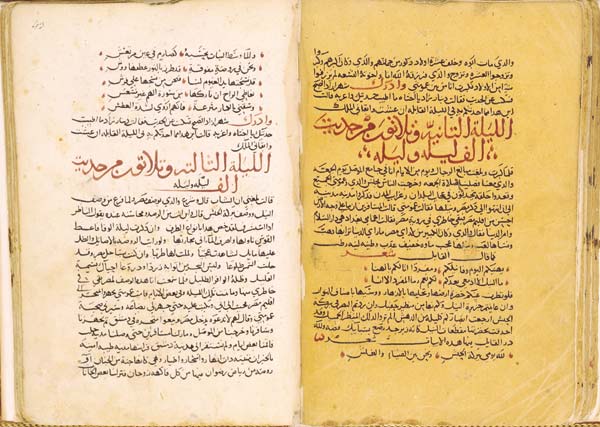

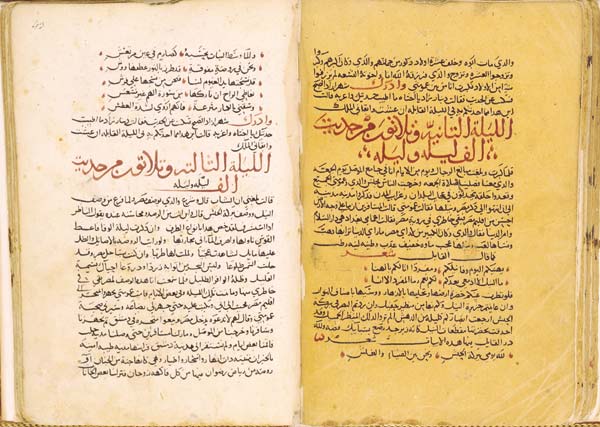

''One Thousand and One Nights''

Several stories within the ''One Thousand and One Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' (, ), is a collection of Middle Eastern folktales compiled in the Arabic language during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as ''The Arabian Nights'', from the first English-language edition ( ...

'' (''Arabian Nights'', 8th–10th centuries CE) also feature science fiction elements. One example is "The Adventures of Bulukiya", where the protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a ...

Bulukiya's quest for the herb of immortality leads him to explore the seas, journey to the Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden (; ; ) or Garden of God ( and ), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2–3 and Ezekiel 28 and 31..

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Ge ...

and to Jahannam

In Islam, Jahannam () is the place of punishment for Islamic views on sin, evildoers in the afterlife, or hell. This notion is an integral part of Islamic theology,#ETISN2009, Thomassen, "Islamic Hell", ''Numen'', 56, 2009: p.401 and has occupied ...

(Islamic hell), and travel across the cosmos

The cosmos (, ; ) is an alternative name for the universe or its nature or order. Usage of the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos is studied in cosmologya broad discipline covering ...

to different worlds much larger than his own world, anticipating elements of galactic

Galactic is an American funk band from New Orleans, Louisiana.

Origins and background

Formed in 1994 as an octet (under the name Galactic Prophylactic) and including singer Chris Lane and guitarist Rob Gowen, the group was soon pared down to a ...

science fiction; along the way, he encounters societies of jinn

Jinn or djinn (), alternatively genies, are supernatural beings in pre-Islamic Arabian religion and Islam.

Their existence is generally defined as parallel to humans, as they have free will, are accountable for their deeds, and can be either ...

, mermaid

In folklore, a mermaid is an aquatic creature with the head and upper body of a female human and the tail of a fish. Mermaids appear in the folklore of many cultures worldwide, including Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

Mermaids are ...

s, talking serpents, talking tree

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, e.g., including only woody plants with secondary growth, only ...

s, and other forms of life.

In "Abdullah the Fisherman and Abdullah the Merman", the protagonist gains the ability to breathe underwater and discovers an underwater submarine society that is portrayed as an inverted reflection of society on land, in that the underwater society follows a form of primitive communism

Primitive communism is a way of describing the gift economies of hunter-gatherers throughout history, where resources and property hunted or gathered are shared with all members of a group in accordance with individual needs. In political sociolo ...

where concepts like money and clothing do not exist.

Other ''Arabian Nights'' tales deal with lost ancient technologies, advanced ancient civilizations that went astray, and catastrophes which overwhelmed them. "The City of Brass" features a group of travellers on an archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

expedition across the Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

to find an ancient lost city and attempt to recover a brass vessel that the biblical King Solomon

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a constitutional monarch if his power is restrained by f ...

once used to trap a jinn, and, along the way, encounter a mummified queen, petrified

In geology, petrifaction or petrification () is the process by which organic material becomes a fossil through the replacement of the original material and the filling of the original pore spaces with minerals. Petrified wood typifies this proce ...

inhabitants, lifelike humanoid robot

A humanoid robot is a robot resembling the human body in shape. The design may be for functional purposes, such as interacting with human tools and environments and working alongside humans, for experimental purposes, such as the study of bipeda ...

s and automata

An automaton (; : automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions. Some automata, such as bellstrikers i ...

, seductive marionette

A marionette ( ; ) is a puppet controlled from above using wires or strings depending on regional variations. A marionette's puppeteer is called a marionettist. Marionettes are operated with the puppeteer hidden or revealed to an audience by ...

s dancing without strings, and a brass robot

A robot is a machine—especially one Computer program, programmable by a computer—capable of carrying out a complex series of actions Automation, automatically. A robot can be guided by an external control device, or the robot control, co ...

horseman who directs the party towards the ancient city.

"The Ebony Horse" features a robot in the form of a flying mechanical horse controlled using keys, that could fly into outer space and towards the Sun, while the "Third Qalandar's Tale" also features a robot in the form of an uncanny

"The Ebony Horse" features a robot in the form of a flying mechanical horse controlled using keys, that could fly into outer space and towards the Sun, while the "Third Qalandar's Tale" also features a robot in the form of an uncanny sailor

A sailor, seaman, mariner, or seafarer is a person who works aboard a watercraft as part of its crew, and may work in any one of a number of different fields that are related to the operation and maintenance of a ship. While the term ''sailor'' ...

. "The City of Brass" and "The Ebony Horse" can be considered early examples of proto-science fiction. (cf.

The abbreviation cf. (short for either Latin or , both meaning 'compare') is generally used in writing to refer the reader to other material to make a comparison with the topic being discussed. However some sources offer differing or even contr ...

) Other examples of early Arabic proto-science fiction include al-Farabi

file:A21-133 grande.webp, thumbnail, 200px, Postage stamp of the USSR, issued on the 1100th anniversary of the birth of Al-Farabi (1975)

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (; – 14 December 950–12 January 951), known in the Greek East and Latin West ...

's ''Opinions of the Residents of a Splendid City'' about a utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

n society, and certain ''Arabian Nights'' elements such as the flying carpet.

Other medieval literature

According to Dr. Abu Shadi al-Roubi, the final two chapters of the Arabic theological novel ''Fādil ibn Nātiq'' (c. 1270), also known as ''Theologus Autodidactus

''Theologus Autodidactus'' (English: "The Self-taught Theologian") is an Arabic novel written by Ibn al-Nafis, originally titled ''The Treatise of Kāmil on the Prophet's Biography'' (), and also known as ''Risālat Fādil ibn Nātiq'' ("The Book ...

'', by the Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

ian polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

writer Ibn al-Nafis

ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Abī Ḥazm al-Qarashī (Arabic: علاء الدين أبو الحسن عليّ بن أبي حزم القرشي ), known as Ibn al-Nafīs (Arabic: ابن النفيس), was an Arab polymath whose area ...

(1213–1288) can be described as science fiction. The theological novel deals with various science fiction elements such as spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from non-living matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could ...

, futurology

Futures studies, futures research or futurology is the systematic, interdisciplinary and holistic study of social and technological advancement, and other environmental trends, often for the purpose of exploring how people will live and wor ...

, apocalyptic themes, eschatology

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of Contemporary era, present age, human history, or the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic and non-Abrah ...

, resurrection

Resurrection or anastasis is the concept of coming back to life after death. Reincarnation is a similar process hypothesized by other religions involving the same person or deity returning to another body. The disappearance of a body is anothe ...

and the afterlife

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's Stream of consciousness (psychology), stream of consciousness or Personal identity, identity continues to exist after the death of their ...

, but rather than giving supernatural or mythological explanations for these events, Ibn al-Nafis attempted to explain these plot elements using his own extensive scientific knowledge

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

in anatomy, biology, physiology, astronomy, cosmology and geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

. For example, it was through this novel

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ...

that Ibn al-Nafis introduces his scientific theory of metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

, and he makes references to his own scientific discovery of pulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulation is a division of the circulatory system in all vertebrates. The circuit begins with deoxygenated blood returned from the body to the right atrium of the heart where it is pumped out from the right ventricle to the lun ...

in order to explain bodily resurrection. The novel was later translated into English as in the early 20th century.

During the European Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, science fictional themes appeared within many chivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of high medieval and early modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalri ...

and legends. Robot

A robot is a machine—especially one Computer program, programmable by a computer—capable of carrying out a complex series of actions Automation, automatically. A robot can be guided by an external control device, or the robot control, co ...

s and automata

An automaton (; : automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions. Some automata, such as bellstrikers i ...

featured in romances starting in the twelfth century, with and Enéas among the first. The , another twelfth-century work, features the famous Chambre de Beautes, which contained four automata, one of which held a magic mirror, one of which performed somersaults, one of which played musical instruments, and one which showed people what they most needed. Automata in these works were often ambivalently associated with necromancy

Necromancy () is the practice of Magic (paranormal), magic involving communication with the Death, dead by Evocation, summoning their spirits as Ghost, apparitions or Vision (spirituality), visions for the purpose of divination; imparting the ...

, and frequently guarded entrances or provided warning of intruders. This association with necromancy often leads to the appearance of automata guarding tombs, as they do in ''Eneas'', '' Floris and Blancheflour'', and , while in Lancelot

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), alternatively written as Launcelot and other variants, is a popular character in the Matter of Britain, Arthurian legend's chivalric romance tradition. He is typically depicted as King Arthu ...

they appear in an underground palace. Automata did not have to be human, however. A brass horse is among the marvelous gifts given to the Cambyuskan in Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

's " The Squire's Tale". This metal horse is reminiscent of similar metal horses in middle eastern literature, and could take its rider anywhere in the world at extraordinary speed by turning a peg in its ear and whispering certain words into it. The brass horse is only one of the technological marvels which appears in "The Squire's Tale": the Cambyuskan, or Khan

Khan may refer to:

* Khan (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Khan (title), a royal title for a ruler in Mongol and Turkic languages and used by various ethnicities

Art and entertainment

* Khan (band), an English progressiv ...

, also receives a mirror which reveals distant places, which the witnessing crowd explains as operating by the manipulation of angles and optics, and a sword which deals and heals deadly wounds, which the crowd explains as being possible using advanced smithing

A metalsmith or simply smith is a craftsperson fashioning useful items (for example, tools, kitchenware, tableware, jewelry, armor and weapons) out of various metals. Smithing is one of the oldest metalworking occupations. Shaping metal with a ...

techniques.

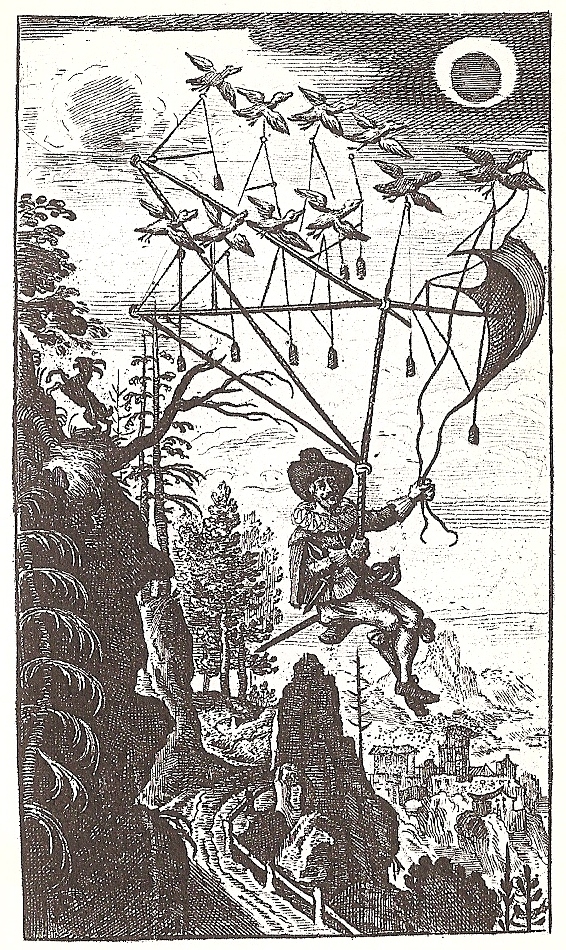

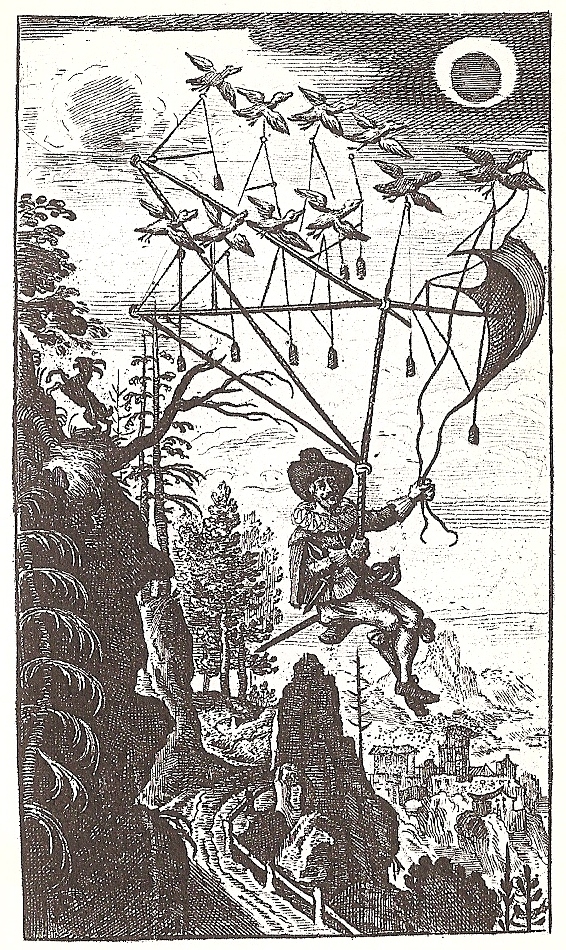

Technological inventions are also rife in the Alexander romances. In John Gower

John Gower (; c. 1330 – October 1408) was an English poet, a contemporary of William Langland and the Pearl Poet, and a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer. He is remembered primarily for three major works—the ''Mirour de l'Omme'', ''Vox ...

's , for example, Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

constructs a flying machine by tying two griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (; Classical Latin: ''gryps'' or ''grypus''; Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk ...

s to a platform and dangling meat above them on a pole. This adventure is ended only by the direct intervention of God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

, who destroys the device and throws Alexander back to the ground. This does not, however, stop the legendary Alexander, who proceeds to construct a gigantic orb of glass which he uses to travel beneath the water. There, he sees extraordinary marvels which eventually exceed his comprehension.

States similar to suspended animation

Suspended animation is the slowing or stopping of biological function so that physiological capabilities are preserved. States of suspended animation are common in micro-organisms and some plant tissue, such as seeds. Many animals, including l ...

also appear in medieval romances, such as the and the . In the former, King Priam

In Greek mythology, Priam (; , ) was the legendary and last king of Troy during the Trojan War. He was the son of Laomedon. His many children included notable characters such as Hector, Paris, and Cassandra.

Etymology

Most scholars take the e ...

has the body of the hero Hector

In Greek mythology, Hector (; , ) was a Trojan prince, a hero and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. He is a major character in Homer's ''Iliad'', where he leads the Trojans and their allies in the defense of Troy, killing c ...

entombed in a network of golden tubes that run through his body. Through these tubes ran the semi-legendary fluid balsam

Balsam is the resinous exudate (or sap) which forms on certain kinds of trees and shrubs. Balsam (from Latin ''balsamum'' "gum of the balsam tree," ultimately from a Semitic source such as ) owes its name to the biblical Balm of Gilead.

Ch ...

which was then reputed to have the power to preserve life. This fluid kept the corpse of Hector preserved as if he was still alive, maintaining him in a persistent vegetative state

A vegetative state (VS) or post-coma unresponsiveness (PCU) is a disorder of consciousness in which patients with severe brain damage are in a state of partial arousal rather than true awareness. After four weeks in a vegetative state, the patie ...

during which autonomic processes such as the growth of facial hair continued.

The boundaries between medieval fiction with scientific elements and medieval science can be fuzzy at best. In works such as Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

's "The House of Fame

''The House of Fame'' (''Hous of Fame'' in the original spelling) is a Middle English poem by Geoffrey Chaucer, probably written between 1374 and 1385, making it one of his earlier works. It was most likely written after ''The Book of the Duchess ...

", it is proposed that the titular House of Fame is the natural home of sound

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the ''reception'' of such waves and their ''perception'' by the br ...

, described as a ripping in the air, towards which all sound is eventually attracted, in the same way that the Earth was believed to be the natural home of earth to which it was all eventually attracted. Likewise, medieval travel narratives often contained science-fictional themes and elements. Works such as '' Mandeville's Travels'' included automata

An automaton (; : automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions. Some automata, such as bellstrikers i ...

, alternate species and sub-species of humans, including Cynoencephali and Giants

A giant is a being of human appearance, sometimes of prodigious size and strength, common in folklore.

Giant(s) or The Giant(s) may also refer to:

Mythology and religion

*Giants (Greek mythology)

* Jötunn, a Germanic term often translated as 'g ...

, and information about the sexual reproduction of diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

s. However, '' Mandeville's Travels'' and other travel narratives in its genre mix real geographical

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

knowledge with knowledge now known to be fictional, and it is therefore difficult to distinguish which portions should be considered science fictional or would have been seen as such in the Middle Ages.

Proto-science fiction in the Enlightenment and Age of Reason

In the wake of scientific discoveries that characterized theEnlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, several new types of literature began to take shape in 16th-century Europe. The humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

thinker Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

's 1516 work of fiction and political philosophy entitled ''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

'' describes a fictional island whose inhabitants have perfected every aspect of their society. The name of the society stuck, giving rise to the Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

motif that would become so widespread in later science fiction to describe a world that is seemingly perfect but either ultimately unattainable or perversely flawed. The Faust

Faust ( , ) is the protagonist of a classic German folklore, German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust (). The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a deal with the Devil at a ...

legend (1587) contains an early prototype for the mad scientist

The mad scientist (also mad doctor or mad professor) is a stock character of a scientist who is perceived as "mad, bad and dangerous to know" or "insanity, insane" owing to a combination of unusual or unsettling personality traits and the unabas ...

story.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the so-called "

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the so-called "Age of Reason

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empiric ...

" and widespread interest in scientific discovery fueled the creation of speculative fiction that anticipated many of the tropes of more recent science fiction. Several works expanded on imaginary voyages to the Moon, first in Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

's '' Somnium'' (''The Dream'', 1634), which both Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is his research on the possibility of extraterrestrial life, including e ...

and Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov ( ; – April 6, 1992) was an Russian-born American writer and professor of biochemistry at Boston University. During his lifetime, Asimov was considered one of the "Big Three" science fiction writers, along with Robert A. H ...

have referred to as the first work of science fiction. Similarly, some identify Francis Godwin

Francis Godwin (1562–1633) was an English historian, science fiction author and priest, who was Bishop of Llandaff and of Hereford.

Life

He was the son of Thomas Godwin, Bishop of Bath and Wells, born at Hannington, Northamptonshire. He wa ...

's ''The Man in the Moone

''The Man in the Moone'' is a book by the English Divine (noun), divine and Church of England bishop Francis Godwin (1562–1633), describing a "voyage of utopian discovery". Long considered to be one of his early works, it is now generally tho ...

'' (1638) as the first work of science fiction in English, and Cyrano de Bergerac

Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac ( , ; 6 March 1619 – 28 July 1655) was a French novelist, playwright, epistolarian, and duelist.

A bold and innovative author, his work was part of the libertine literature of the first half of the 17th ce ...

's ''Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon

''The Other World: Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon'' () was the first of three satirical novels written by Cyrano de Bergerac. It was published posthumously in 1657 and, along with its companion work '' The States and Empir ...

'' (1656). Space travel also figures prominently in Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

's (1752), which is also notable for the suggestion that people of other worlds may be in some ways more advanced than those of Earth.

Other works containing proto-science-fiction elements from the Age of Reason

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empiric ...

of the 17th and 18th centuries include (in chronological order):

*Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's ''The Tempest

''The Tempest'' is a Shakespeare's plays, play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1610–1611, and thought to be one of the last plays that he wrote alone. After the first scene, which takes place on a ship at sea during a tempest, th ...

'' (1610–11) contains a prototype for the "mad scientist

The mad scientist (also mad doctor or mad professor) is a stock character of a scientist who is perceived as "mad, bad and dangerous to know" or "insanity, insane" owing to a combination of unusual or unsettling personality traits and the unabas ...

story".

*Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

's ''New Atlantis

''New Atlantis'' is a utopian novel by Sir Francis Bacon, published posthumously in 1626. It appeared unheralded and tucked into the back of a longer work of natural history, ''Sylva Sylvarum'' (forest of materials). In ''New Atlantis'', Bac ...

'' (1627), an incomplete utopian novel.

*Margaret Cavendish

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (; 1623 er exact birth date is unknown– 16 December 1673) was an English philosopher, poet, scientist, fiction writer, and playwright. She was a prolific writer, publishing over 12 original ...

's '' The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing-World'' (1666), a novel that describes another world (with different stars in the sky) that can be reached via the North Pole.

*Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

's ''The Consolidator

''The Consolidator; or, Memoirs of Sundry Transactions from the World in the Moon'' is a fictional adventure by Daniel Defoe published in 1705. It is a satirical novel that mixes fantasy, political satire, and social satire.

Plot summary

The ...

'' (1705) revolves around a voyage to the Moon.

*Simon Tyssot de Patot

Simon Tyssot de Patot (1655–1738) was a French writer and poet during the Age of Enlightenment who penned two very important, seminal works in fantastic literature. Tyssot was born in London of French Huguenot parents. He was brought up in Roua ...

's (1710) features a Lost World (genre), Lost World.

*Simon Tyssot de Patot

Simon Tyssot de Patot (1655–1738) was a French writer and poet during the Age of Enlightenment who penned two very important, seminal works in fantastic literature. Tyssot was born in London of French Huguenot parents. He was brought up in Roua ...

's (1720) features a Hollow Earth.

*Jonathan Swift's ''Gulliver's Travels'' (1726) contains descriptions of alien cultures and "weird science".

*Samuel Madden (author), Samuel Madden's ''Memoirs of the Twentieth Century'' (1733) in which a narrator from 1728 is given a series of state documents from 1997 to 1998 by his guardian angel, a plot device which is reminiscent of later Time travel in fiction, time travel novels. However, the story does not explain how the angel obtained these documents.

*Ludvig Holberg's ''Niels Klim's Underground Travels'' (1741) is an early example of the Hollow Earth genre.

*Louis-Sébastien Mercier's (1771) gives a predictive account of life in the 25th century.

*Nicolas-Edme Rétif, Nicolas-Edmé Restif de la Bretonne's (1781) features prophetic inventions.

*Giacomo Casanova's ''Icosameron'' (1788) is a novel that makes use of the hollow Earth device.

19th-century transitions

Shelley and Europe in the early 19th century

The 19th century saw a major acceleration of these trends and features, most clearly seen in the groundbreaking publication of Mary Shelley's ''Frankenstein, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' in 1818. The short novel features the archetypal "mad scientist

The mad scientist (also mad doctor or mad professor) is a stock character of a scientist who is perceived as "mad, bad and dangerous to know" or "insanity, insane" owing to a combination of unusual or unsettling personality traits and the unabas ...

" experimenting with advanced technology. In his book ''Billion Year Spree'', Brian Aldiss claims ''Frankenstein'' represents "the first seminal work to which the label SF can be logically attached". It is also the first of the "mad scientist

The mad scientist (also mad doctor or mad professor) is a stock character of a scientist who is perceived as "mad, bad and dangerous to know" or "insanity, insane" owing to a combination of unusual or unsettling personality traits and the unabas ...

" subgenre. Although normally associated with the gothic horror genre, the novel introduces science fiction themes such as the use of technology for achievements beyond the scope of science at the time, and the alien as antagonist, furnishing a view of the human condition from an outside perspective. Aldiss argues that science fiction in general derives its conventions from the gothic novel. Mary Shelley's short story "Roger Dodsworth (story), Roger Dodsworth: The Reanimated Englishman" (1826) sees a man frozen in ice revived in the present day, incorporating the now common science fiction theme of cryonics whilst also exemplifying Shelley's use of science as a conceit to drive her stories. Another futuristic Shelley novel, ''The Last Man (Mary Shelley novel), The Last Man'', has been cited as the first dystopian novel.

In 1836 Alexander Veltman published ''Predki Kalimerosa': Aleksandr Filippovich Makedonskii'' (The forebears of Kalimeros: Alexander, son of Philip of Macedon), which has been called the first original Russian science fiction and fantasy, Russian science fiction novel and the first novel to use time travel

Time travel is the hypothetical activity of traveling into the past or future. Time travel is a concept in philosophy and fiction, particularly science fiction. In fiction, time travel is typically achieved through the use of a device known a ...

. Albeit time travel achieved via a magical hippogriff rather than technological means. The narrator meets Aristotle, and goes on a voyage with Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

before returning to the 19th century.

Somehow influenced by the scientific theories of the 19th century, but most certainly by the idea of human progress, Victor Hugo wrote in ''La Légende des siècles, The Legend of the Centuries'' (1859) a long poem in two parts that can be viewed like a dystopia/utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

fiction, called ''20th century''. It shows in a first scene the body of a broken huge ship, the greatest product of the prideful and foolish mankind that called it ''Leviathan'', wandering in a desert world where the winds blow and the anger of the wounded Nature is; humanity, finally reunited and pacified, has gone toward the stars in a starship, to look for and to bring liberty into the light.

Other notable proto-science fiction authors and works of the early 19th century include:

* Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville's ''Le Dernier Homme'' (1805, ''The Last Man'').

* Historian Félix Bodin's ''Le Roman de l'Avenir'' (1834) and Emile Souvestre's ''Le Monde Tel Qu'il Sera'' (1846), two novels which try to predict what the next century will be like.

* Jane C. Loudon's ''The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century'' (1827), in which Cheops is revived by scientific means into a world in political crisis, where technology has advanced to gas-flame jewelry and houses that migrate on rails, etc.

* Louis Geoffroy's ''Napoleon et la Conquête du Monde'' (1836), an Alternate history (fiction), alternate history of a world conquered by Napoleon.

* C.I. Defontenay's ''Star ou Psi de Cassiopée'' (1854), an Olaf Stapledon-like chronicle of an alien world and civilization.

* Slovak author Gustáv Reuss's :sk:Gustáv Reuss, Gustáv Reuss ''Hviezdoveda alebo životopis Krutohlava, čo na Zemi, okolo Mesiaca a Slnka skúsil a čo o obežniciach, vlasaticiach, pôvode a konci sveta vedel ("The Science of the Stars or The Life of Krutohlav who Visited the Moon and the Sun and Knew about Planets, Comets and the Beginning and the End of the World" )'' (1856). In this book Gustáv Reuss sends his hero named Krutohlav, a scholar from the Gemer region, right to the Moon... in a balloon. When the hero comes back, he builds a sort of a dragon-like interstellar ship, in which the characters travel around the whole known Solar System and eventually visit all the countries of the Earth.

* Astronomer Camille Flammarion's ''La Pluralité des Mondes Habités'' (1862) which speculated on extraterrestrial life.

* Edward S. Ellis's ''The Steam Man of the Prairies'' (1868) The first novel starts when Ethan Hopkins and Mickey McSquizzle—a "Yankee" and an "Irishman"—encounter a colossal, steam-powered man in the American prairies. This steam-man was constructed by Johnny Brainerd, a teenaged boy, who uses the steam-man to carry him in a carriage on various adventures.

* Edward Bulwer-Lytton's ''The Coming Race'' (1871), a novel where the main character discovers a highly evolved subterranean civilization. PSI-powers are given a logical and scientific explanation, achieved through biological evolution and technological progress, rather than something magical or supernatural.

Verne and Wells

The European brand of science fiction proper began later in the 19th century with the scientific romances of H. G. Wells, H.G. Wells and the science-oriented, socially critical novels of Jules Verne. Verne's adventure stories, notably ''Journey to the Center of the Earth'' (1864), ''From the Earth to the Moon'' (1865), and ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' (1869) mixed daring romantic adventure with technology that was either up to the minute or logically extrapolated into the future. They were tremendous commercial successes and established that an author could make a career out of such whimsical material. L. Sprague de Camp calls Verne "the world's first full-time List of science fiction authors, science fiction novelist." Wells's stories, on the other hand, use science fiction devices to make didactic points about his society. In ''The Time Machine'' (1895), for example, the technical details of the machine are glossed over quickly so that the Time Traveller can tell a story that criticizes the stratification of English society. The story also uses Darwinian evolution (as would be expected in a former student of Darwin's champion, Thomas Henry Huxley, Huxley), and shows an awareness of Marxism. In ''The War of the Worlds (novel), The War of the Worlds'' (1898), the Martians' technology is not explained as it would have been in a Verne story, and the story is resolved by a deus ex machina, albeit a scientifically explained one. The differences between Verne and Wells highlight a tension that has existed in science fiction throughout its history. The question of whether to present realistic technology or to focus on characters and ideas has been ever-present, as has the question of whether to tell an exciting story or make a didactic point.Late 19th-century expansion

Wells and Verne had quite a few rivals in early science fiction. Short stories and novelettes with themes of fantastic imagining appeared in journals throughout the late 19th century and many of these employed scientific ideas as the springboard to the imagination. ''Erewhon'' is a novel by Samuel Butler (1835–1902), Samuel Butler published in 1872 and dealing with the concept that machines could one day become sentience, sentient and supplant the human race. In 1886 the novel ''The Future Eve'' by French author Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam was published, where Thomas Edison builds an artificial woman. Although better known for Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle also wrote early science fiction, particularly using the character of Professor Challenger. Rudyard Kipling's contributions to the genre in the early 1900s made John W. Campbell, Campbell describe him as "the first modern science fiction writer". Other writers in the field were Bengali science fiction authors such as Sukumar Ray and Roquia Sakhawat Hussain, Begum Roquia Sakhawat Hussain, who wrote the earliest known feminist science fiction work, ''Sultana's Dream''. Another early feminist science fiction work at the time was Charlotte Perkins Gilman' ''Herland (novel), Herland''. Wells and Verne both had an international readership and influenced writers in America, especially. Soon a home-grown American science fiction was thriving. European writers found more readers by selling to the American market and writing in an Americanised style.American proto-science fiction in the 19th century

In the last decades of the 19th century, works of science fiction for adults and children were numerous in America, though it was not yet given the name "science fiction." There were science-fiction elements in the stories of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Fitz-James O'Brien. Edgar Allan Poe is often mentioned with Verne and Wells as the founders of science fiction (although Mary Shelley's ''Frankenstein'' predates these). A number of Poe's short stories and the novel ''The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket'' are science fictional. An 1827 satiric novel by philosopher George Tucker (American politician), George Tucker ''A Voyage to the Moon'' is sometimes cited as the first American science fiction novel. In 1835 Edgar Allan Poe published a short story, "The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall" in which a flight to the Moon in a balloon is described. It has an account of the launch, the construction of the cabin, descriptions of strata and many more science-like aspects. In addition to Poe's account the story written in 1813 by the Dutch Willem Bilderdijk is remarkable. In his novel ''Kort verhaal van eene aanmerkelijke luchtreis en nieuwe planeetontdekking'' (Short account of a remarkable journey into the skies and discovery of a new planet) Bilderdijk tells of a European somewhat stranded in an Arabic country where he boasts he is able to build a balloon that can lift people and let them fly through the air. The gasses used turn out to be far more powerful than expected and after a while he lands on a planet positioned between Earth and Moon. The writer uses the story to portray an overview of scientific knowledge concerning the Moon in all sorts of aspects the traveller to that place would encounter. Quite a few similarities can be found in the story Poe published some twenty years later. John Leonard Riddell, a Professor of Chemistry in New Orleans, published the short story ''Orrin Lindsay's plan of aerial navigation, with a narrative of his explorations in the higher regions of the atmosphere, and his wonderful voyage round the moon!'' in 1847 on a pamphlet. It tells the story of the student Orrin Lindsay who invents an alloy that prevents gravitational attraction, and in a spherical craft leaves Earth and travel to the Moon. The story contains algebra and scientific footnotes, which makes it an early example of hard science fiction. Unitarianism, Unitarian minister and writer Edward Everett Hale wrote ''The Brick Moon'', a Verne-inspired novella, first published serially in 1869 in ''The Atlantic Monthy,'' notable as the first work to describe an artificial satellite. Written in much the same style as his other work, it employs pseudo-journalistic realism to tell an adventure story with little basis in reality. William Henry Rhodes published in 1871 the tale ''The Case of Summerfield'' in the Sacramento Union newspaper, and introduced weapon of mass destruction. A mad scientist and villain called Black Bart makes an attempt to blackmail the world with a powder made of potassium, able to destroy the planet by turning its waters into fire. The newspaperman Edward Page Mitchell would publish his innovative science fiction short stories in ''The Sun (New York), The Sun'' for more than a decade, except for his first story which was published in ''Scribner's Monthly'' in 1874. His stories included invisibility, faster than light travels, teleportation, time travel, cryogenics, mind transfer, mutants, cyborgs and mechanical brains. One of the most successful works of early American science fiction was the second-best selling novel in the U.S. in the 19th century: Edward Bellamy's ''Looking Backward'' (1888), its effects extending far beyond the field of literature. ''Looking Backward'' extrapolates a future society based on observation of the current society. Mark Twain explored themes of science in his novel ''A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court''. By means of ''"transmigration of souls", "transposition of epochs – and bodies"'' Twain's Yankee is transported back in time and his knowledge of 19th-century technology with him. Written in 1889, ''A Connecticut Yankee'' seems to predict the events of World War I, when Europe's old ideas of chivalry in warfare were shattered by new weapons and tactics. Charles Curtis Dail, a Kentucky lawyer, published in 1890 the novel ''Willmoth the Wanderer, or The Man from Saturn'', had his protagonist travel through the Solar System by covering his body with an anti-gravity ointment. In 1894, Will Harben published "Land of the Changing Sun," a dystopian fantasy set at the center of the Earth. In Harben's tale, the Earth's core is populated by a scientifically advanced civilization, living beneath the glow of a mechanical sun.Early 20th century

American author L. Frank Baum's series of 14 books (1900–1920) based in his outlandish Land of Oz setting, contained depictions of strange weapons (Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, Glinda of Oz), mechanical men (Tik-Tok of Oz) and a bevy of not-yet-realized technological inventions and devices including perhaps the first literary appearance of handheld wireless communicators (Tik-Tok of Oz). Jack London wrote several science fiction stories, including "The Red One" (a story involving extraterrestrials), ''The Iron Heel'' (set in the future from London's point of view) and "The Unparalleled Invasion" (a story involving future germ warfare and ethnic cleansing). He also wrote a story about invisibility and a story about an irresistible Directed-energy weapon, energy weapon. These stories began to change the features of science fiction. Rudyard Kipling's contributions to science fiction go beyond their direct impact at the start of the 20th century. The Aerial Board of Control stories and his critique of the British military, ''The Army of a Dream'', were not only very modern in style, but strongly influenced authors like John W. Campbell and Rober A. Heinlein, the latter of whom wrote a novel, ''Starship Troopers'' (1959), that contains all of the elements of The Army of a Dream, and whose 1961 novel ''Stranger in a Strange Land'' can be compared to ''The Jungle Book'', with the human child raised by Martians instead of wolves. Heinlein's technique of indirect exposition first appears in Kiplings' writing. Heinlein, a major influence on science fiction from the 1930s forward, has also described himself as influenced by George Bernard Shaw, whose longest work ''Back to Methuselah'' (1921) was itself science fiction. Robert Hugh Benson wrote one of the first modern dystopias, Lord of the World (1907), partially in reaction to Wells' atheistic utopian writing, which Benson rejected as Christian. Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875–1950) began writing science fiction for pulp magazine, pulp magazines just before World War I, getting his first story ''Under the Moons of Mars'' published in 1912. He continued to publish adventure stories, many of them science fiction, throughout the rest of his life. The pulps published adventure stories of all kinds. Science fiction stories had to fit in alongside murder mystery, murder mysteries, horror fiction, horror, fantasy and Edgar Rice Burroughs' own Tarzan. The next great science fiction writers after H. G. Wells were Olaf Stapledon (1886–1950), whose four major works ''Last and First Men'' (1930), ''Odd John'' (1935), ''Star Maker'' (1937), and ''Sirius (novel), Sirius'' (1944), introduced a myriad of ideas that writers have since adopted, and J.-H. Rosny aîné, born in Belgium, the father of "modern" French science fiction, a writer also comparable to H. G. Wells, who wrote the classic ''Les Xipehuz'' (1887) and ''La Mort de la Terre'' (1910). However, the Twenties and Thirties would see the genre represented in a new format.Birth of the pulps

The development of American science fiction as a self-conscious genre dates in part from 1926, when Hugo Gernsback founded ''Amazing Stories'' magazine, which was devoted exclusively to science fiction stories. Though science fiction magazines had been published in Germany before, ''Amazing Stories'' was the first English language magazine to solely publish science fiction. Since he is notable for having chosen the variant term ''scientifiction'' to describe this incipient genre, the stage in the genre's development, his name and the term "scientifiction" are often thought to be inextricably linked. Though Gernsback encouraged stories featuring scientific realism to educate his readers about scientific principles, such stories shared the pages with exciting stories with little basis in reality. Much of what Gernsback published was referred to as "gadget fiction", about what happens when someone makes a technological invention. Published in this and other pulp magazines with great and growing success, such scientifiction stories were not viewed as serious literature but as sensationalism. Nevertheless, a magazine devoted entirely to science fiction was a great boost to the public awareness of the scientific speculation story. ''Amazing Stories'' competed with several other pulp magazines, including ''Weird Tales'' (which primarily published fantasy stories), ''Astounding Stories'', and ''Wonder Stories'', throughout the 1930s. It was in the Gernsback era that science fiction fandom arose through the medium of the "Letters to the Editor" columns of ''Amazing'' and its competitors. In August 1928, Amazing Stories published Skylark of Space and Armageddon 2419 A.D., while Weird Tales published Edmond Hamilton's ''Crashing Suns'', all of which represented the birth ofspace opera

Space opera is a subgenre of science fiction that emphasizes Space warfare in science fiction, space warfare, with use of melodramatic, risk-taking space adventures, relationships, and chivalric romance. Set mainly or entirely in outer space, i ...

.

Fritz Lang's movie ''Metropolis (1927 movie), Metropolis'' (1927), in which the first cinematic humanoid robot

A robot is a machine—especially one Computer program, programmable by a computer—capable of carrying out a complex series of actions Automation, automatically. A robot can be guided by an external control device, or the robot control, co ...

was seen, and the Italian Futurism (art), Futurists' love of machines are indicative of both the hopes and fears of the world between the world wars.

''Metropolis'' was an extremely successful film and its art-deco inspired aesthetic became the guiding aesthetic of the science fiction pulps for some time.

In the late 1930s, John W. Campbell became editor of ''Astounding Science Fiction'', the second magazine devoted to science fiction, originally published as ''Astounding Stories of Super-Science'' in 1930. Campbell's tenure at ''Astounding'' is considered to be the beginning of the Golden Age of science fiction, as he helped shift the focus away from pulpy adventure stories, to those characterized by hard science fiction stories celebrating scientific achievement and progress.

Modernist writing

Writers attempted to respond to the new world in the post-World War I era. In the 1920s and 30s writers entirely unconnected with science fiction were exploring new ways of telling a story and new ways of treating time, space and experience in the narrative form. The posthumously published works of Franz Kafka (who died in 1924) and the works of modernism, modernist writers such as James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf and others featured stories in which time and individual identity could be expanded, contracted, looped and otherwise distorted. While this work was unconnected to science fiction as a genre, it did deal with the impact of modernity (technology, science, and change) upon people's lives, and decades later, during the New Wave (science fiction), New Wave movement, some modernist literary techniques entered science fiction. Czech playwright Karel Čapek's plays ''The Makropulos Affair'', ''R.U.R.'', ''The Life of the Insects'', and the novel ''War with the Newts'' were modernist literature which invented important science fiction motifs. ''R.U.R.'' in particular is noted for introducing the wordrobot

A robot is a machine—especially one Computer program, programmable by a computer—capable of carrying out a complex series of actions Automation, automatically. A robot can be guided by an external control device, or the robot control, co ...

to the world's vocabulary.

A strong theme in modernist writing was ''Social alienation, alienation'', the making strange of familiar surroundings so that settings and behaviour usually regarded as "normality (behavior), normal" are seen as though they were the seemingly bizarre practices of an alien culture. The audience of modernist plays or the readership of modern novels is often led to question everything.

At the same time, a tradition of more literary science fiction novels, treating with a dissonance between perceived Utopian conditions and the full expression of human desires, began to develop: the Dystopia, dystopian novel. For some time, the science fictional elements of these works were ignored by mainstream literary critics, though they owe a much greater debt to the science fiction genre than the modernists do. Sincerely Utopian writing, including much of Wells, has also deeply influenced science fiction, beginning with Hugo Gernsback's ''Ralph 124C 41+''.

Yevgeny Zamyatin's 1920 novel ''We (novel), We'' depicts a totalitarian attempt to create a utopia that results in a dystopic state where free will is lost. Aldous Huxley bridged the gap between the literary establishment and the world of science fiction with ''Brave New World'' (1932), an ironic portrait of a stable and ostensibly happy society built by human mastery of genetic manipulation.

George Orwell wrote perhaps the most highly regarded of these literary dystopias, ''Nineteen Eighty-Four'', in 1948. He envisions a technologically governed totalitarian regime that dominates society through total information control. Zamyatin's ''We'' is recognized as an influence on both Huxley and Orwell; Orwell published a book review of ''We'' shortly after it was first published in English, several years before writing ''1984''.

Ray Bradbury, Ray Bradbury's ''Fahrenheit 451'', Ursula K. Le Guin, Ursula K. Le Guin's ''The Dispossessed, The Dispossessed:An Ambiguous Utopia'', much of Kurt Vonnegut, Kurt Vonnegut's writing, and many other works of later science fiction continue this dialogue between utopia and dystopia.

Science fiction's impact on the public

Orson Welles, Orson Welles's ''The Mercury Theatre on the Air, Mercury Theatre'' produced a radio version of ''The War of the Worlds (1938 radio drama), The War of the Worlds'' which, according to urban myth, panicked large numbers of people who believed the program to be a real newscast. However, there is doubt as to how much anecdotes of mass panic had any reflection in reality, and the myth may have originated among newspapers, jealous of the upstart new medium of radio. Inarguably, though, the idea of visitors or invaders from outer space became embedded in the consciousness of everyday people. During World War II, American military planners studied science fiction for ideas. The British did the same, and also asked authors to submit outlandish ideas which the government leaked to the Axis as real plans. Pilots speculated as to the origins of the "Foo fighters" they saw around them in the air. Meanwhile, the Germans had developed flying bombs known as V1s and V2s reminiscent of the "rocket ships" ever-present in pulp science fiction, presaging space flight. Jet planes and the atom bomb were developed. "Deadline (science fiction story), Deadline", a Cleve Cartmill short story about a fictional atomic bomb project, prompted the FBI to visit the offices of ''Astounding Science Fiction''. Asimov said that "The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, dropping of the atom bomb in 1945 made science fiction respectable. Once the horror at Hiroshima took place, anyone could see that science fiction writers were not merely dreamers and crackpots after all, and that many of the motifs of that class of literature were now permanently part of the newspaper headlines". With the story of a Roswell crash, flying saucer crash in Roswell, New Mexico in 1947, science fiction had become modern folklore.The Golden Age

The period of the 1940s and 1950s is often referred to as the Golden Age of Science Fiction.''Astounding'' Magazine

With the emergence in 1937 of a demanding editor, John W. Campbell, John W. Campbell, Jr., at ''Astounding (magazine), Astounding Science Fiction'', and with the publication of stories and novels by such writers asIsaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov ( ; – April 6, 1992) was an Russian-born American writer and professor of biochemistry at Boston University. During his lifetime, Asimov was considered one of the "Big Three" science fiction writers, along with Robert A. H ...

, Arthur C. Clarke, and Robert A. Heinlein, science fiction began to gain status as serious fiction.

Campbell exercised an extraordinary influence over the work of his stable of writers, thus shaping the direction of science fiction. Asimov wrote, "We were extensions of himself; we were his literary clones." Under Campbell's direction, the years from 1938–1950 would become known as the Golden Age of Science Fiction, "Golden Age of science fiction", though Asimov points out that the term Golden Age has been used more loosely to refer to other periods in science fiction's history.

Campbell's guidance to his writers included his famous dictum, "Write me a creature that thinks as well as a man, or better than a man, but not like a man." He emphasized a higher quality of writing than editors before him, giving special attention to developing the group of young writers who attached themselves to him.

Ventures into the genre by writers who were not devoted exclusively to science fiction also added respectability. Magazine covers of bug-eyed monsters and scantily clad women, however, preserved the image of a sensational genre appealing only to adolescents. There was a public desire for sensation, a desire of people to be taken out of their dull lives to the worlds of space travel and adventure.

An interesting footnote to Campbell's regime is his contribution to the rise of L. Ron Hubbard, L. Ron Hubbard's religion Scientology. Hubbard was considered a promising science fiction writer and a protégé of Campbell, who published Hubbard's first articles about Dianetics and his new religion. As Campbell's reign as editor of ''Astounding'' progressed, Campbell gave more attention to ideas like Hubbard's, writing editorials in support of Dianetics. Though ''Astounding'' continued to have a loyal fanbase, readers started turning to other magazines to find science fiction stories.

The Golden Age in other media