Potsdam Agreements on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Potsdam Agreement () was the agreement among three of the

The Potsdam Agreement () was the agreement among three of the

Cornerstone of Steel

Monday, January 21, 1946

Time Magazine, Monday, September 8, 1947

Protocol of the Proceedings of the Berlin Conference

Official US text of the Potsdam protocols; annotated with editing variants and variant readings from the official Soviet and British texts. {{Authority control Politics of World War II Aftermath of World War II

The Potsdam Agreement () was the agreement among three of the

The Potsdam Agreement () was the agreement among three of the Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international Coalition#Military, military coalition formed during World War II (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers. Its principal members were the "Four Policeme ...

: the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

after the war ended in Europe that was signed on 1 August 1945 and published the following day. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned the military occupation and reconstruction of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, its border

Borders are generally defined as geography, geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by polity, political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other administrative divisio ...

, and the entire European Theatre of War territory. It also addressed Germany's demilitarisation

Demilitarisation or demilitarization may mean the reduction of state armed forces; it is the opposite of militarisation in many respects. For instance, the demilitarisation of Northern Ireland entailed the reduction of British security and milita ...

, reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Reparation (theology), the theological concept of corrective response to God and the associated prayers for repairing the damages of sin

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for re ...

, the prosecution of war criminal

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostage ...

s and the mass expulsion of ethnic Germans from various parts of Europe. France was not invited to the conference but formally remained one of the powers occupying Germany.

Executed as a communiqué, the agreement was not a peace treaty

A peace treaty is an treaty, agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually country, countries or governments, which formally ends a declaration of war, state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an ag ...

according to international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

, although it created accomplished facts. It was superseded by the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany

The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany (),

more commonly referred to as the Two Plus Four Agreement (),

is an international agreement that allowed the reunification of Germany in October 1990. It was negotiated in 1990 betwee ...

signed on 12 September 1990.

As De Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

had not been invited to the Conference, the French resisted implementing the Potsdam Agreement within their occupation zone. In particular, the French refused to resettle any expelled Germans from the east. Moreover, the French did not accept any obligation to abide by the Potsdam Agreement in the proceedings of the Allied Control Council; in particular resisting all proposals to establish common policies and institutions across Germany as a whole (for example, France separated Saarland from Germany to establish its protectorate on 17 December 1947), and anything that they feared might lead to the emergence of an eventual unified German government.

Overview

After theend of World War II in Europe

The end of World War II in Europe occurred in May 1945. Following the Death of Adolf Hitler, suicide of Adolf Hitler on 30 April, leadership of Nazi Germany passed to Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz and the Flensburg Government. Soviet Union, Soviet t ...

(1939–1945), and the decisions of the earlier Tehran

Tehran (; , ''Tehrân'') is the capital and largest city of Iran. It is the capital of Tehran province, and the administrative center for Tehran County and its Central District (Tehran County), Central District. With a population of around 9. ...

, Casablanca

Casablanca (, ) is the largest city in Morocco and the country's economic and business centre. Located on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Chaouia (Morocco), Chaouia plain in the central-western part of Morocco, the city has a populatio ...

and Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (), held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. The three sta ...

s, the Allies assumed supreme authority over Germany by the Berlin Declaration of June 5, 1945.

At the Potsdam Conference the Western Allies were presented with Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's ''fait accompli'' awarding Soviet-occupied Poland the river Oder

The Oder ( ; Czech and ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and its largest tributary the Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows through wes ...

as its western border, placing the entire Soviet Occupation Zone east of it (with the exception of the Kaliningrad

Kaliningrad,. known as Königsberg; ; . until 1946, is the largest city and administrative centre of Kaliningrad Oblast, an Enclave and exclave, exclave of Russia between Lithuania and Poland ( west of the bulk of Russia), located on the Prego ...

enclave), including Pomerania

Pomerania ( ; ; ; ) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The central and eastern part belongs to the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, West Pomeranian, Pomeranian Voivod ...

, most of East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

, and Danzig, under Polish administration. The German population who had not fled were expelled and their properties acquisitioned by the state. President Truman and the British delegations protested at these actions.

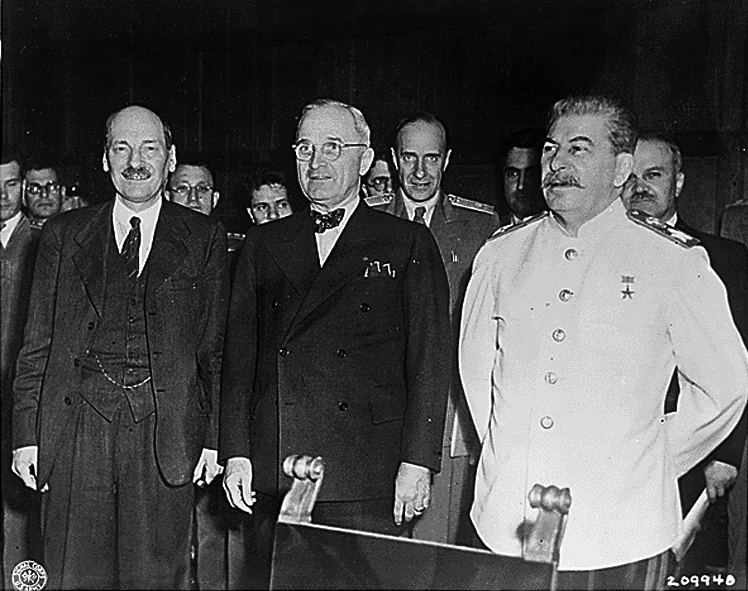

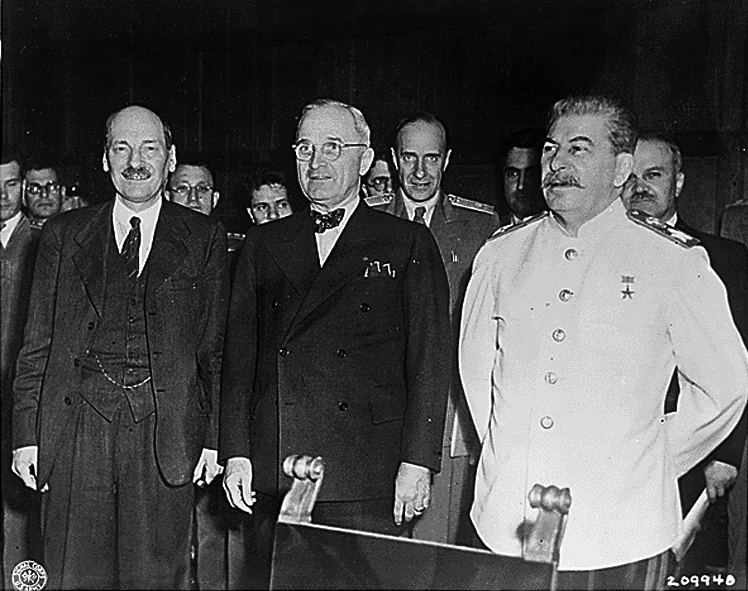

The Three Power Conference took place from 17 July to 2 August 1945, in which they adopted the ''Protocol of the Proceedings, August 1, 1945'', signed at Cecilienhof

Cecilienhof Palace () is a palace in Potsdam, Brandenburg, Germany, built from 1914 to 1917 in the layout of an English Tudor manor house. Cecilienhof was the last palace built by the House of Hohenzollern that ruled the Kingdom of Prussia and t ...

Palace in Potsdam

Potsdam () is the capital and largest city of the Germany, German States of Germany, state of Brandenburg. It is part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. Potsdam sits on the Havel, River Havel, a tributary of the Elbe, downstream of B ...

. The signatories were General Secretary Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

, and Prime Minister Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. At ...

, who, as a result of the British general election of 1945, had replaced Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

as the UK's representative. The three powers also agreed to invite France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

to participate as members of the Council of Foreign Ministers established to oversee the agreement. The Provisional Government of the French Republic

The Provisional Government of the French Republic (PGFR; , GPRF) was the provisional government of Free France between 3 June 1944 and 27 October 1946, following the liberation of continental France after Operations ''Overlord'' and ''Drago ...

accepted the invitation on August 7, with the key reservation that it would not accept ''a priori'' any commitment to the eventual reconstitution of a central government in Germany.

James F. Byrnes

James Francis Byrnes ( ; May 2, 1882 – April 9, 1972) was an American judge and politician from South Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in the U.S. Congress and on the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as in the executive branch ...

wrote "we specifically refrained from promising to support at the German Peace Conference any particular line as the western frontier of Poland". The Berlin Protocol declared: "The three heads of government reaffirm their opinion that the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the inalpeace settlement." Byrnes continues: "In the light of this history, it is difficult to credit with good faith any person who asserts that Poland's western boundary was fixed by the conferences, or that there was a promise that it would be established at some particular place." Despite this, the Oder–Neisse Line

The Oder–Neisse line (, ) is an unofficial term for the Germany–Poland border, modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion ...

was set as Poland's provisional (and therefore theoretically subject to change) western frontier in Article 8 of the Agreement but was not finalized as Poland's permanent western frontier until the 1990 German–Polish Border Treaty

The German–Polish Border Treaty of 1990 finally settled the issue of the Polish–German border, which in terms of international law had been pending since 1945. It was signed by the foreign ministers of Poland and Germany, Krzysztof Skubis ...

, having been recognized by East Germany in 1950 (in the Treaty of Zgorzelec

The Treaty of Zgorzelec (Full title ''The Agreement Concerning the Demarcation of the Established and the Existing Polish-German State Frontier'', also known as the ''Treaty of Görlitz'' and ''Treaty of Zgorzelic'') between the People's Repub ...

) and acquiesced to by West Germany in 1970 (in the Treaty of Moscow (1970)

The Treaty of Moscow was signed on 12 August 1970 between the Soviet Union and West Germany. It was signed by Willy Brandt and Walter Scheel for West Germany's side and by Alexei Kosygin and Andrei Gromyko for the Soviet Union.

Description

In the ...

and the Treaty of Warsaw (1970)

The Treaty of Warsaw (, ) was a treaty between the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) and the Polish People’s Republic. It was signed by Chancellor Willy Brandt and Prime Minister Józef Cyrankiewicz at the Presidential Palace on 7 ...

).

Protocol

In the Potsdam Agreement (Berlin Conference) the Allies (UK, USSR, US) agreed on the following matters: # Establishment of aCouncil of Foreign Ministers

Council of Foreign Ministers was an organisation agreed upon at the Potsdam Conference in 1945 and announced in the Potsdam Agreement and dissolved upon the entry into force of the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany in 1991.

...

, also including France and China; tasked the preparation of a peace settlement for Germany, to be accepted by the Government of Germany once a government adequate for the purpose had been established.

#:See the London Conference of Foreign Ministers and the Moscow Conference which took place later in 1945.

#The principles to govern the treatment of Germany in the initial control period.

#:See European Advisory Commission

The formation of the European Advisory Commission (EAC) was agreed on at the Moscow Conference (1943), Moscow Conference on 30 October 1943 between the foreign ministers of the United Kingdom, Anthony Eden, the United States, Cordell Hull, and ...

and Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council (ACC) or Allied Control Authority (), also referred to as the Four Powers (), was the governing body of the Allies of World War II, Allied Allied-occupied Germany, occupation zones in Germany (1945–1949/1991) and Al ...

.

#*A. Political principles.

#: Post-war Germany to be divided into four Occupation Zones under the control of Britain, the Soviet Union, the United States and France; with the Commanders-in-chief of each country's forces exercising sovereign authority over matters within their own zones, while exercising authority jointly through the Allied Control Council for 'Germany as a whole'.

#:Democratization

Democratization, or democratisation, is the structural government transition from an democratic transition, authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction ...

. Treatment of Germany as a single unit. Disarmament and Demilitarization

Demilitarisation or demilitarization may mean the reduction of state armed forces; it is the opposite of militarisation in many respects. For instance, the demilitarisation of Northern Ireland entailed the reduction of British security and milita ...

. Elimination of all Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

influence.

#*B. Economic principles.

#:Reduction or destruction of all civilian heavy industry with war potential, such as shipbuilding, machine production and chemical factories. Restructuring of German economy towards agriculture and light industry.

# Reparations from Germany.

#:This section covered reparation claims of the USSR from the Soviet occupation zone in Germany

The Soviet occupation zone in Germany ( or , ; ) was an area of Germany that was occupied by the Soviet Union as a communist area, established as a result of the Potsdam Agreement on 2 August 1945. On 7 October 1949 the German Democratic Republ ...

. The section also agreed that 10% of the industrial capacity of the western zones unnecessary for the German peace economy should be transferred to the Soviet Union within two years. The Soviet Union withdrew its previous objections to French membership of the Allied Reparations Commission, which had been established in Moscow following the Yalta conference.

# Disposal of the German Navy

The German Navy (, ) is part of the unified (Federal Defense), the German Armed Forces. The German Navy was originally known as the ''Bundesmarine'' (Federal Navy) from 1956 to 1995, when ''Deutsche Marine'' (German Navy) became the official ...

and merchant marine.

#:All but thirty submarines to be sunk and the rest of the German Navy was to be divided equally between the three powers.

#:The German merchant marine was to be divided equally between the three powers, and they would distribute some of those ships to the other Allies. But until the end of the war with the Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

all the ships would remain under the authority of the Combined Shipping Adjustment Board and the United Maritime Authority.

# City of Königsberg

Königsberg (; ; ; ; ; ; , ) is the historic Germany, German and Prussian name of the city now called Kaliningrad, Russia. The city was founded in 1255 on the site of the small Old Prussians, Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teuton ...

and the adjacent area (then East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

, now Kaliningrad Oblast

Kaliningrad Oblast () is the westernmost federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of the Russian Federation. It is a Enclave and exclave, semi-exclave on the Baltic Sea within the Baltic region of Prussia (region), Prussia, surrounded by Pola ...

).

#:The United States and Britain declared that they would support the transfer of Königsberg and the adjacent area to the Soviet Union at the peace conference.

#War criminals

#: This was a short paragraph and covered the creation of the London Charter #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

and the subsequent Nuremberg trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

:

#:The Three Governments have taken note of the discussions which have been proceeding in recent weeks in London between British, United States, Soviet and French representatives with a view to reaching agreement on the methods of trial of those major war criminals whose crimes under the#Moscow Declaration The Moscow Declarations were four declarations signed during the Moscow Conference (1943), Moscow Conference on October 30, 1943. The declarations are distinct from the communique that was issued following the Moscow Conference (1945), Moscow Confe ...of October 1943 have no particular geographical localization. The Three Governments reaffirm their intention to bring these criminals to swift and sure justice. They hope that the negotiations in London will result in speedy agreement being reached for this purpose, and they regard it as a matter of great importance that the trial of these major criminals should begin at the earliest possible date. The first list of defendants will be published before 1st September.

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

:

#:The government of Austria was to be decided after British and American forces entered Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, and that Austria should not pay any reparations.

#Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

#:There should be a Provisional Government of National Unity

The Provisional Government of National Unity (, TRJN) was a puppet government formed by the decree of the State National Council (, KRN) on 28 June 1945 as a result of reshuffling the Soviet-backed Provisional Government of the Republic of Pola ...

recognised by all three powers, and that those Poles who were serving in British Army formations should be free to return to Poland. The provisional western border should be the Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (, ) is an unofficial term for the Germany–Poland border, modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion ...

, with territories to the east of this excluded from the Soviet Occupation zone and placed under Polish and Soviet civil administration. Poland would receive former German territories in the north and west, but the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement; which eventually took place as the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany

The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany (),

more commonly referred to as the Two Plus Four Agreement (),

is an international agreement that allowed the reunification of Germany in October 1990. It was negotiated in 1990 betwee ...

in 1990.

# Conclusion on peace treaties and admission to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

organization.

#:See Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers which took place later in 1945.

#:It was noted that Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

had fought on the side of the Allies and was making good progress towards establishment of a democratic government and institutions and that after the peace treaty the three Allies would support an application from a democratic Italian government for membership of the United Nations. Further,

#:e three Governments have also charged the Council of Foreign Ministers with the task of preparing peace treaties for#:The details were discussed later that year at the Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers and the treaties were signed in 1947 at theBulgaria Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...,Finland Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...,Hungary Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...andRomania Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to .... The conclusion of Peace Treaties with recognized democratic governments in these States will also enable the three Governments to support applications from them for membership of the United Nations. The three Governments agree to examine each separately in the near future in the light of the conditions then prevailing, the establishment of diplomatic relations with Finland, Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary to the extent possible prior to the conclusion of peace treaties with those countries.

Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

.

#:By that time the governments of Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary were Communist.

#Territorial Trusteeship

#:Italian former colonies would be decided in connection with the preparation of a peace treaty for Italy. Like most of the other former European Axis powers the Italian peace treaty was signed at the 1947 Paris Peace Conference.

#Revised Allied Control Commission

Following the termination of hostilities in World War II, the Allies were in control of the defeated Axis countries. Anticipating the defeat of Germany, Italy and Japan, they had already set up the European Advisory Commission and a proposed Far ...

procedure in Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary

#:Now that hostilities in Europe were at an end the Western Allies should have a greater input into the Control Commissions of Central and Eastern Europe, the Annex to this agreement included detailed changes to the workings of the Hungarian Control Commission.

#Orderly transfer of German Populations

#:

#:The Three Governments, having considered the question in all its aspects, recognize that the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland,#:"German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland" refers to Germans living within the 1937 boundaries of Poland up to the Curzon Line going East. In theory, that German ethnic population could have been expelled to the Polish temporarily administered territories ofCzechoslovakia Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...and Hungary, will have to be undertaken. They agree that any transfers that take place should be effected in an orderly and humane manner.

Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

, Farther Pomerania

Farther Pomerania, Hinder Pomerania, Rear Pomerania or Eastern Pomerania (; ), is a subregion of the historic region of Pomerania in north-western Poland, mostly within the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, while its easternmost parts are within the Po ...

, East Prussia and eastern Brandenburg

Brandenburg, officially the State of Brandenburg, is a States of Germany, state in northeastern Germany. Brandenburg borders Poland and the states of Berlin, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony. It is the List of Ger ...

.

#:Because Allied-occupied Germany

The entirety of Germany was occupied and administered by the Allies of World War II, from the Berlin Declaration on 5 June 1945 to the establishment of West Germany on 23 May 1949. Unlike occupied Japan, Nazi Germany was stripped of its sov ...

was under great strain, the Czechoslovak government, the Polish provisional government and the control council in Hungary were asked to submit an estimate of the time and rate at which further transfers could be carried out having regard to the present situation in Germany and suspend further expulsions until these estimates were integrated into plans for an equitable distribution of these "removed" Germans among the several zones of occupation.

#Oil equipment in Romania

#Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

#:Allied troops were to withdraw immediately from Tehran

Tehran (; , ''Tehrân'') is the capital and largest city of Iran. It is the capital of Tehran province, and the administrative center for Tehran County and its Central District (Tehran County), Central District. With a population of around 9. ...

and that further stages of the withdrawal of troops from Iran should be considered at the meeting of the Council of Foreign Ministers to be held in London in September 1945.

#The international zone of Tangier

Tangier ( ; , , ) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The city is the capital city, capital of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region, as well as the Tangier-Assilah Prefecture of Moroc ...

.

#:The city of Tangier and the area around it should remain international and discussed further.

#The Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

straits

#:The Montreux Convention should be revised and that this should be discussed with the Turkish government.

#International inland waterways

#European inland transport conference

#Directives to the military commanders on allied control council for Germany

#Use of Allied property for satellite reparations or war trophies

#:These were detailed in Annex II.

#Military Talks

*Annex I

*Annex II

Moreover, towards concluding the Pacific Theatre of War, the Potsdam Conference issued the Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, ...

, the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender (26 July 1945) wherein the Western Allies (UK, US, USSR) and the Nationalist China of General Chiang Kai-shek asked Japan to surrender or be destroyed.

Aftermath

Already during the Potsdam Conference, on 30 July 1945, theAllied Control Council

The Allied Control Council (ACC) or Allied Control Authority (), also referred to as the Four Powers (), was the governing body of the Allies of World War II, Allied Allied-occupied Germany, occupation zones in Germany (1945–1949/1991) and Al ...

was constituted in Berlin to execute the Allied resolutions (the "Four Ds"):

*Denazification

Denazification () was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by removing those who had been Nazi Par ...

of the German society to eradicate Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

influence

*Demilitarization

Demilitarisation or demilitarization may mean the reduction of state armed forces; it is the opposite of militarisation in many respects. For instance, the demilitarisation of Northern Ireland entailed the reduction of British security and milita ...

of the former Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

forces and the German arms industry; however, the circumstances of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

soon led to Germany's ''Wiederbewaffnung

West German rearmament () began in the decades after World War II. Fears of another rise of German militarism caused the new military to operate within an alliance framework, under NATO command. The events led to the establishment of the ''Bund ...

'' including the re-establishment of both the Bundeswehr

The (, ''Federal Defence'') are the armed forces of the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany. The is divided into a military part (armed forces or ''Streitkräfte'') and a civil part, the military part consists of the four armed forces: Germ ...

and the National People's Army

The National People's Army (, ; NVA ) were the armed forces of the East Germany, German Democratic Republic (DDR) from 1956 until 1990.

The NVA was organized into four branches: the (Ground Forces), the (Navy), the (Air Force) and the (Bord ...

*Democratization

Democratization, or democratisation, is the structural government transition from an democratic transition, authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction ...

, including the formation of political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular area's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

and trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

s, freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

, of the press

Press may refer to:

Media

* Publisher

* News media

* Printing press, commonly called "the press"

* Press TV, an Iranian television network

Newspapers United States

* ''The Press'', a former name of ''The Press-Enterprise'', Riverside, California

...

and religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

*Decentralization

Decentralization or decentralisation is the process by which the activities of an organization, particularly those related to planning and decision-making, are distributed or delegated away from a central, authoritative location or group and gi ...

resulting in the re-establishment of German federalism, along with disassemblement as part of the industrial plans for Germany. Dismantling was stopped in West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

in 1951 according to the Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is a Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy that pledges American support for democratic nations against Authoritarianism, authoritarian threats. The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering ...

, whereafter East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

had to cope with the impact alone.

Territorial changes

The northern half of the German province ofEast Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

, occupied by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

during its East Prussian Offensive followed by its evacuation in winter 1945, had already been incorporated into Soviet territory as the Kaliningrad Oblast

Kaliningrad Oblast () is the westernmost federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of the Russian Federation. It is a Enclave and exclave, semi-exclave on the Baltic Sea within the Baltic region of Prussia (region), Prussia, surrounded by Pola ...

. The Western Allies promised to support the annexation of the territory north of the Braunsberg

Braniewo () (, , Old Prussian: ''Brus''), is a town in northern Poland, in Warmia, in the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, with a population of 16,907 as of June 2021. It is the capital of Braniewo County.

Braniewo is the second biggest city of ...

– Goldap line when a Final German Peace Treaty was held.

The Allies had acknowledged the legitimacy of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity

The Provisional Government of National Unity (, TRJN) was a puppet government formed by the decree of the State National Council (, KRN) on 28 June 1945 as a result of reshuffling the Soviet-backed Provisional Government of the Republic of Pola ...

, which was about to form a Soviet satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting a larger ob ...

. Urged by Stalin, the UK and the US gave in to put the German territories east of the Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (, ) is an unofficial term for the Germany–Poland border, modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion ...

from the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

coast west of Świnoujście

Świnoujście (; ; ; meaning " Świna ivermouth"; ) is a city in Western Pomerania and seaport on the Baltic Sea and Szczecin Lagoon, in the extreme north-west of Poland, mainly on the islands of Usedom and Wolin, and Karsibór island, once ...

up to the Czechoslovak

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

** Fourth Czechoslovak Repu ...

border "under Polish administration"; allegedly confusing the Lusatian Neisse

The Lusatian Neisse (; ; ; Upper Sorbian: ''Łužiska Nysa''; Lower Sorbian: ''Łužyska Nysa''), or Western Neisse, is a river in northern Central Europe.

and the Glatzer Neisse rivers. The proposal of an Oder– Bober–Queis

The Kwisa (, , ) is a river in south-western Poland, a left tributary of the Bóbr, which itself is a left tributary of the Oder river.

It rises in the Jizera Mountains, part of the Western Sudetes range, where it runs along the border with the ...

line was rejected by the Soviet delegation. The cession included the former Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (; ) was a city-state under the protection and oversight of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland) and nearly 200 other small localities in the surrou ...

and the seaport of Stettin

Szczecin ( , , ; ; ; or ) is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major seaport, the largest city of northwestern Poland, and se ...

on the mouth of the Oder

The Oder ( ; Czech and ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and its largest tributary the Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows through wes ...

River (Szczecin Lagoon

Szczecin Lagoon (, ), also known as Oder Lagoon (), and Pomeranian Lagoon (), is a lagoon in the Oder estuary, shared by Germany and Poland. It is separated from the Pomeranian Bay of the Baltic Sea by the islands of Usedom and Wolin. The la ...

), vital for the Upper Silesian Industrial Region

The Upper Silesian Industrial Region (, , Polish abbreviation: ''GOP'' ; ) is a large industrial region in Poland.

.

Post-war, 'Germany as a whole' would consist solely of aggregate territories of the respective zones of occupation. As all former German territories east of the Oder–Neisse line were excluded from the Soviet Occupation Zone, they were consequently excluded from 'Germany as a whole'.Expulsions

In the course of the proceedings, and after the German state killed around 5-6 million Polish citizens during the war,Polish communists

Communism in Poland can trace its origins to the late 19th century: the Marxist First Proletariat party was founded in 1882. Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919) of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (''Socjaldemokracja Króle ...

had begun to suppress the German population west of the Bóbr river to underline their demand for a border on the Lusatian Neisse. The Allied resolution on the "orderly transfer" of German population became the legitimation of the expulsion of Germans from the nebulous parts of Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

, if they had not already fled from the advancing Red Army.

The expulsion of ethnic Germans by the Poles concerned, in addition to Germans within areas behind the 1937 Polish border in the West (such as in most of the old Prussian province of West Prussia), the territories placed "under Polish administration" pending a Final German Peace Treaty, i.e. southern East Prussia (Masuria

Masuria ( ; ; ) is an ethnographic and geographic region in northern and northeastern Poland, known for its 2,000 lakes. Masuria occupies much of the Masurian Lake District. Administratively, it is part of the Warmian–Masurian Voivodeship (ad ...

), Farther Pomerania

Farther Pomerania, Hinder Pomerania, Rear Pomerania or Eastern Pomerania (; ), is a subregion of the historic region of Pomerania in north-western Poland, mostly within the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, while its easternmost parts are within the Po ...

, the New March

The Neumark (), also known as the New March () or as East Brandenburg (), was a region of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and its successors located east of the Oder River in territory which became part of Poland in 1945 except some villages of ...

region of the former Province of Brandenburg

The Province of Brandenburg () was a province of Prussia from 1815 to 1947. Brandenburg was established in 1815 from the Kingdom of Prussia's core territory, comprised the bulk of the historic Margraviate of Brandenburg (excluding Altmark) and ...

, the districts of the ''Grenzmark'' Posen-West Prussia, Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ( ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ) is a historical and geographical region mostly located in Poland with small portions in the Czech Republic and Germany. It is the western part of the region of Silesia. Its largest city is Wrocław.

The first ...

and those parts of Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( ; ; ; ; Silesian German: ; ) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located today mostly in Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic. The area is predominantly known for its heav ...

that had remained with Germany after the 1921 Upper Silesia plebiscite

The Upper Silesia plebiscite was a plebiscite mandated by the Versailles Treaty and carried out on 20 March 1921 to determine ownership of the province of Upper Silesia between Weimar Germany and the Second Polish Republic. The region was ethni ...

. It further affected the German minority living within the territory of the former Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

in Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; ), is a Polish Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest city in Poland.

The bound ...

, eastern Upper Silesia, Chełmno Land

Chełmno land (, or Kulmerland) is a part of the historical region of Pomerelia, located in central-northern Poland.

Chełmno land is named after the city of Chełmno. The largest city in the region is Toruń; another bigger city is Grudziąd ...

and the Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor (; ), also known as the Pomeranian Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia (Pomeranian Voivodeship, Eastern Pomerania), which provided the Second Polish Republic with access to the Baltic Sea, thus d ...

with Danzig.

The Germans in Czechoslovakia

German Bohemians ( ; ), later known as Sudeten Germans ( ; ), were ethnic Germans living in the Czech lands of the Bohemian Crown, which later became an integral part of Czechoslovakia. Before 1945, over three million German Bohemians constitu ...

(34% of the population of the territory of what is now the Czech Republic), known as Sudeten Germans

German Bohemians ( ; ), later known as Sudeten Germans ( ; ), were ethnic Germans living in the Czech lands of the Bohemian Crown, which later became an integral part of Czechoslovakia. Before 1945, over three million German Bohemians constitute ...

but also Carpathian Germans

Carpathian Germans (, or ''felvidéki németek'', , , ) are a group of Germans, ethnic Germans in Central and Eastern Europe. The term was coined by the historian :de:Raimund Friedrich Kaindl, Raimund Friederich Kaindl (1866–1930), originally ...

, were expelled from the ''Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and ) is a German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohe ...

'' region where they formed a majority, from linguistic enclaves in central Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

and Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

, as well as from the city of Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

.

Though the Potsdam Agreement referred only to Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, expulsions also occurred in Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, where the Transylvanian Saxons

The Transylvanian Saxons (; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjer Såksen'' or simply ''Soxen'', singularly ''Sox'' or ''Soax''; Transylvanian Landler dialect, Transylvanian Landler: ''Soxn'' or ''Soxisch''; ; seldom ''sa ...

were deported

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people by a state from its Sovereignty, sovereign territory. The actual definition changes depending on the place and context, and it also changes over time. A person who has been deported or ...

and their property seized, and in Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

. In the Soviet territories, Germans were expelled from northern East Prussia ( Oblast Kaliningrad) but also from the adjacent Lithuanian Klaipėda Region

The Klaipėda Region () or Memel Territory ( or ''Memelgebiet'') was defined by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles in 1920 and refers to the northernmost part of the German province of East Prussia, when, as Memelland, it was put under the administr ...

and other lands settled by Baltic Germans

Baltic Germans ( or , later ) are ethnic German inhabitants of the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, in what today are Estonia and Latvia. Since their resettlement in 1945 after the end of World War II, Baltic Germans have drastically decli ...

.

See also

*Territorial changes of Poland immediately after World War II

At the end of World War II, Poland underwent major changes to the location of its international border. In 1945, after the defeat of Nazi Germany, the Oder–Neisse line became its western border, resulting in gaining the Recovered Territories ...

*History of Germany (1945–1990)

From 1945 to 1990. the divided Germany began with the Berlin Declaration (1945), Berlin Declaration, marking the abolition of the Nazi Germany, German Reich and Allied-occupied Germany, Allied-occupied period in Germany on 5 June 1945, and ende ...

*Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (, ) is an unofficial term for the Germany–Poland border, modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion ...

References

External links

Cornerstone of Steel

Monday, January 21, 1946

Time Magazine, Monday, September 8, 1947

Protocol of the Proceedings of the Berlin Conference

Official US text of the Potsdam protocols; annotated with editing variants and variant readings from the official Soviet and British texts. {{Authority control Politics of World War II Aftermath of World War II

Agreement

Agreement may refer to:

Agreements between people and organizations

* Gentlemen's agreement, not enforceable by law

* Trade agreement, between countries

* Consensus (disambiguation), a decision-making process

* Contract, enforceable in a court of ...

1945 in the United States

Allied occupation of Germany

Germany–Soviet Union relations

History of East Germany

Treaties concluded in 1945

Treaties entered into force in 1945

Treaties of the Soviet Union

Treaties of the United Kingdom

Treaties of the United States

World War II treaties

Soviet Union–United States treaties

1945 in the United Kingdom

1945 in the Soviet Union

1945 in Germany