Pol I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

DNA polymerase I (or Pol I) is an

DNA polymerase I obtained from ''E. coli'' is used extensively for

DNA polymerase I obtained from ''E. coli'' is used extensively for

enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

that participates in the process of prokaryotic DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all life, living organisms, acting as the most essential part of heredity, biolog ...

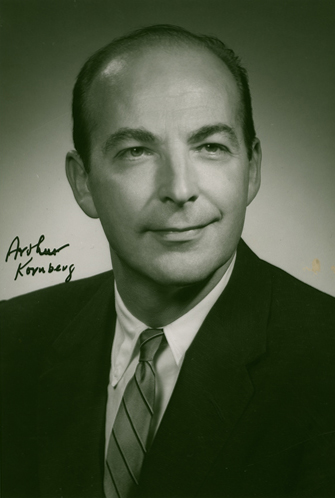

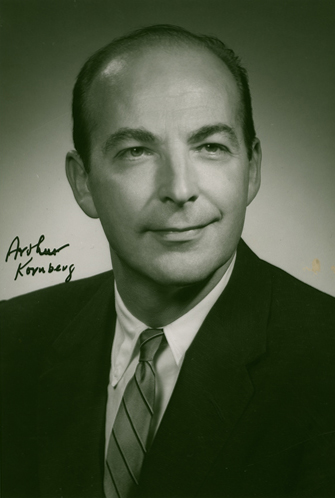

. Discovered by Arthur Kornberg

Arthur Kornberg (March 3, 1918 – October 26, 2007) was an American biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1959 for the discovery of "the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of ribonucleic acid and deoxyribonucleic a ...

in 1956, it was the first known DNA polymerase

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create t ...

(and the first known of any kind of polymerase

In biochemistry, a polymerase is an enzyme (Enzyme Commission number, EC 2.7.7.6/7/19/48/49) that synthesizes long chains of polymers or nucleic acids. DNA polymerase and RNA polymerase are used to assemble DNA and RNA molecules, respectively, by ...

). It was initially characterized in ''E. coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escherichia'' that is commonly foun ...

'' and is ubiquitous in prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s. In ''E. coli'' and many other bacteria, the gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

that encodes Pol I is known as ''polA''. The ''E. coli'' Pol I enzyme is composed of 928 amino acids, and is an example of a processive enzyme — it can sequentially catalyze multiple polymerisation steps without releasing the single-stranded template. The physiological function of Pol I is mainly to support repair of damaged DNA, but it also contributes to connecting Okazaki fragments

Okazaki fragments are short sequences of DNA nucleotides (approximately 150 to 200 base pairs long in eukaryotes) which are synthesized discontinuously and later linked together by the enzyme DNA ligase to create the lagging strand during DN ...

by deleting RNA primers and replacing the ribonucleotides with DNA.

Discovery

In 1956,Arthur Kornberg

Arthur Kornberg (March 3, 1918 – October 26, 2007) was an American biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1959 for the discovery of "the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of ribonucleic acid and deoxyribonucleic a ...

and colleagues discovered Pol I by using ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Escherichia'' that is commonly fo ...

'' (''E. coli'') extracts to develop a DNA synthesis assay. The scientists added 14C-labeled thymidine so that a radioactive polymer of DNA, not RNA, could be retrieved. To initiate the purification of DNA polymerase, the researchers added streptomycin sulfate to the ''E. coli'' extract. This separated the extract into a nucleic acid-free supernatant (S-fraction) and nucleic acid-containing precipitate (P-fraction). The P-fraction also contained Pol I and heat-stable factors essential for the DNA synthesis reactions. These factors were identified as nucleoside triphosphate

A nucleoside triphosphate is a nucleoside containing a nitrogenous base bound to a 5-carbon sugar (either ribose or deoxyribose), with three phosphate groups bound to the sugar. They are the molecular precursors of both DNA and RNA, which are chai ...

s, the building blocks of nucleic acids. The S-fraction contained multiple deoxynucleoside kinases. In 1959, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Arthur Kornberg and Severo Ochoa

Severo Ochoa de Albornoz (; 24 September 1905 – 1 November 1993) was a Spanish physician and biochemist, and winner of the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine together with Arthur Kornberg for their discovery of "the mechanisms in the ...

"for their discovery of the mechanisms involved in the biological synthesis of Ribonucleic acid

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins ( messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyr ...

and Deoxyribonucleic Acid

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of a ...

."

Structure and function

General structure

Pol I mainly functions in the repair of damaged DNA. Structurally, Pol I is a member of the alpha/beta protein superfamily, which encompasses proteins in which α-helices and β-strands occur in irregular sequences. ''E. coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escherichia'' that is commonly foun ...

'' DNA Pol I consists of multiple domains with three distinct enzymatic activities. Three domains, often referred to as thumb, finger and palm domain work together to sustain DNA polymerase activity. A fourth domain next to the palm domain contains an exonuclease

Exonucleases are enzymes that work by cleaving nucleotides one at a time from the end (exo) of a polynucleotide chain. A hydrolyzing reaction that breaks phosphodiester bonds at either the 3′ or the 5′ end occurs. Its close relative is th ...

active site that removes incorrectly incorporated nucleotides in a 3' to 5' direction in a process known as proofreading. A fifth domain contains another exonuclease

Exonucleases are enzymes that work by cleaving nucleotides one at a time from the end (exo) of a polynucleotide chain. A hydrolyzing reaction that breaks phosphodiester bonds at either the 3′ or the 5′ end occurs. Its close relative is th ...

active site that removes DNA or RNA in a 5' to 3' direction and is essential for RNA primer removal during DNA replication or DNA during DNA repair processes.

''E. coli'' bacteria produces 5 different DNA polymerases: DNA Pol I, DNA Pol II, DNA Pol III, DNA Pol IV, and DNA Pol V.

Structural and functional similarity to other polymerases

In DNA replication, the leading DNA strand is continuously extended in the direction of replication fork movement, whereas the DNA lagging strand runs discontinuously in the opposite direction asOkazaki fragments

Okazaki fragments are short sequences of DNA nucleotides (approximately 150 to 200 base pairs long in eukaryotes) which are synthesized discontinuously and later linked together by the enzyme DNA ligase to create the lagging strand during DN ...

. DNA polymerases also cannot initiate DNA chains so they must be initiated by short RNA or DNA segments known as primers. In order for DNA polymerization to take place, two requirements must be met. First of all, all DNA polymerases must have both a template strand and a primer strand. Unlike RNA, DNA polymerases cannot synthesize DNA from a template strand. Synthesis must be initiated by a short RNA segment, known as RNA primer, synthesized by Primase

DNA primase is an enzyme involved in the replication of DNA and is a type of RNA polymerase. Primase catalyzes the synthesis of a short RNA (or DNA in some

living organisms) segment called a primer complementary to a ssDNA (single-stranded ...

in the 5' to 3' direction. DNA synthesis then occurs by the addition of a dNTP to the 3' hydroxyl group at the end of the preexisting DNA strand or RNA primer. Secondly, DNA polymerases can only add new nucleotides to the preexisting strand through hydrogen bonding. Since all DNA polymerases have a similar structure, they all share a two-metal ion-catalyzed polymerase mechanism. One of the metal ions activates the primer 3' hydroxyl group, which then attacks the primary 5' phosphate of the dNTP. The second metal ion will stabilize the leaving oxygen's negative charge, and subsequently chelates the two exiting phosphate groups.

The X-ray crystal structures of polymerase domains of DNA polymerases are described in analogy to human right hands. All DNA polymerases contain three domains. The first domain, which is known as the "fingers domain", interacts with the dNTP and the paired template base. The "fingers domain" also interacts with the template to position it correctly at the active site. Known as the "palm domain", the second domain catalyses the reaction of the transfer of the phosphoryl group. Lastly, the third domain, which is known as the "thumb domain", interacts with double stranded DNA. The exonuclease domain contains its own catalytic site and removes mispaired bases. Among the seven different DNA polymerase families, the "palm domain" is conserved in five of these families. The "finger domain" and "thumb domain" are not consistent in each family due to varying secondary structure elements from different sequences.

Function

Pol I possesses four enzymatic activities: # A 5'→3' (forward) DNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity, requiring a 3' primer site and a template strand # A 3'→5' (reverse)exonuclease

Exonucleases are enzymes that work by cleaving nucleotides one at a time from the end (exo) of a polynucleotide chain. A hydrolyzing reaction that breaks phosphodiester bonds at either the 3′ or the 5′ end occurs. Its close relative is th ...

activity that mediates proofreading

Proofreading is a phase in the process of publishing where galley proofs are compared against the original manuscripts or graphic artworks, to identify transcription errors in the typesetting process. In the past, proofreaders would place corr ...

# A 5'→3' (forward) exonuclease activity mediating nick translation

Nick translation (or head translation), developed in 1977 by Peter Rigby and Paul Berg, is a tagging technique in molecular biology in which DNA polymerase I is used to replace some of the nucleotides of a DNA sequence with their labeled analogue ...

during DNA repair

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell (biology), cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is cons ...

.

# A 5'→3' (forward) RNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity. Pol I operates on RNA templates with considerably lower efficiency (0.1–0.4%) than it does DNA templates, and this activity is probably of only limited biological significance.

In order to determine whether Pol I was primarily used for DNA replication or in the repair of DNA damage, an experiment was conducted with a deficient Pol I mutant strain of ''E. coli''. The mutant strain that lacked Pol I was isolated and treated with a mutagen. The mutant strain developed bacterial colonies that continued to grow normally and that also lacked Pol I. This confirmed that Pol I was not required for DNA replication. However, the mutant strain also displayed characteristics which involved extreme sensitivity to certain factors that damaged DNA, like UV light

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of t ...

. Thus, this reaffirmed that Pol I was more likely to be involved in repairing DNA damage rather than DNA replication.

Mechanism

In the replication process,RNase H

Ribonuclease H (abbreviated RNase H or RNH) is a family of non-nucleotide sequence, sequence-specific endonuclease enzymes that catalysis, catalyze the cleavage of RNA in an RNA/DNA substrate (chemistry), substrate via a hydrolysis, hydrolytic c ...

removes the RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

primer (created by primase

DNA primase is an enzyme involved in the replication of DNA and is a type of RNA polymerase. Primase catalyzes the synthesis of a short RNA (or DNA in some

living organisms) segment called a primer complementary to a ssDNA (single-stranded ...

) from the lagging strand and then polymerase I fills in the necessary nucleotides

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

between the Okazaki fragments

Okazaki fragments are short sequences of DNA nucleotides (approximately 150 to 200 base pairs long in eukaryotes) which are synthesized discontinuously and later linked together by the enzyme DNA ligase to create the lagging strand during DN ...

(see ''DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all life, living organisms, acting as the most essential part of heredity, biolog ...

'') in a 5'→3' direction, proofreading for mistakes as it goes. It is a template-dependent enzyme—it only adds nucleotides that correctly base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

with an existing DNA strand acting as a template. It is crucial that these nucleotides are in the proper orientation and geometry to base pair with the DNA template strand so that DNA ligase

DNA ligase is a type of enzyme that facilitates the joining of DNA strands together by catalyzing the formation of a phosphodiester bond. It plays a role in repairing single-strand breaks in duplex DNA in living organisms, but some forms (such ...

can join the various fragments together into a continuous strand of DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

. Studies of polymerase I have confirmed that different dNTPs can bind to the same active site on polymerase I. Polymerase I is able to actively discriminate between the different dNTPs only after it undergoes a conformational change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or othe ...

. Once this change has occurred, Pol I checks for proper geometry and proper alignment of the base pair, formed between bound dNTP and a matching base on the template strand. The correct geometry of A=T and G≡C base pairs are the only ones that can fit in the active site

In biology and biochemistry, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of amino acid residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate, the ''binding s ...

. However, it is important to know that one in every 104 to 105 nucleotides is added incorrectly. Nevertheless, Pol I can fix this error in DNA replication using its selective method of active discrimination.

Despite its early characterization, it quickly became apparent that polymerase I was not the enzyme responsible for most DNA synthesis—DNA replication in ''E. coli'' proceeds at approximately 1,000 nucleotides/second, while the rate of base pair synthesis by polymerase I averages only between 10 and 20 nucleotides/second. Moreover, its cellular abundance of approximately 400 molecules per cell did not correlate with the fact that there are typically only two replication fork

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms, acting as the most essential part of biological inheritanc ...

s in ''E. coli''. Additionally, it is insufficiently processive to copy an entire genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

, as it falls off after incorporating only 25–50 nucleotides

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

. Its role in replication was proven when, in 1969, John Cairns isolated a viable polymerase I mutant

In biology, and especially in genetics, a mutant is an organism or a new genetic character arising or resulting from an instance of mutation, which is generally an alteration of the DNA sequence of the genome or chromosome of an organism. It i ...

that lacked the polymerase activity. Cairns' lab assistant, Paula De Lucia, created thousands of cell free extracts from ''E. coli'' colonies and assayed them for DNA-polymerase activity. The 3,478th clone contained the polA mutant, which was named by Cairns to credit "Paula" e Lucia It was not until the discovery of DNA polymerase III that the main replicative DNA polymerase was finally identified.

Research applications

DNA polymerase I obtained from ''E. coli'' is used extensively for

DNA polymerase I obtained from ''E. coli'' is used extensively for molecular biology

Molecular biology is a branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecule, molecular basis of biological activity in and between Cell (biology), cells, including biomolecule, biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactio ...

research. However, the 5'→3' exonuclease activity makes it unsuitable for many applications. This undesirable enzymatic activity can be simply removed from the holoenzyme to leave a useful molecule called the Klenow fragment

The Klenow fragment is a large protein fragment produced when DNA polymerase I from '' E. coli'' is enzymatically cleaved by the protease subtilisin. First reported in 1970, it retains the 5' → 3' polymerase activity and the 3’ → 5’ ...

, widely used in molecular biology

Molecular biology is a branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecule, molecular basis of biological activity in and between Cell (biology), cells, including biomolecule, biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactio ...

. In fact, the Klenow fragment was used during the first protocols of polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample rapidly, allowing scientists to amplify a very small sample of DNA (or a part of it) sufficiently to enable detailed st ...

(PCR) amplification until ''Thermus aquaticus

''Thermus aquaticus'' is a species of bacteria that can tolerate high temperatures, one of several thermophile, thermophilic bacteria that belong to the ''Deinococcota'' phylum. It is the source of the heat-resistant enzyme Taq polymerase, ''Taq' ...

'', the source of a heat-tolerant ''Taq'' Polymerase I, was discovered in 1976. Exposure of DNA polymerase I to the protease subtilisin

Subtilisin is a protease (a protein-digesting enzyme) initially obtained from ''Bacillus subtilis''.

Subtilisins belong to subtilases, a group of serine proteases that – like all serine proteases – initiate the nucleophilic attack on the ...

cleaves the molecule into a smaller fragment, which retains only the DNA polymerase and proofreading activities.

See also

*DNA polymerase II

DNA polymerase II (also known as DNA Pol II or Pol II) is a prokaryote, prokaryotic DNA-dependent DNA polymerase encoded by the PolB gene.

DNA Polymerase II is an 89.9-kDa protein and is a member of the B family of DNA polymerases. It was origin ...

* DNA polymerase III

* DNA polymerase V

DNA Polymerase V (Pol V) is a polymerase enzyme involved in DNA repair mechanisms in bacteria, such as ''Escherichia coli''. It is composed of a UmuD' homodimer and a UmuC monomer, forming the UmuD'2C protein complex. It is part of the Y-family ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dna Polymerase I EC 2.7.7 DNA replication Enzymes 1956 in biology