Plan W on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Plan W, during

Plan W, during

Irish preparations for defence of the island included protecting against the possibility of British or German attack. The Irish Army drew up contingency plans for an invasion from across the border although only two of its eight brigades were normally based in the northern half of the country. The Second Division did prepare two lines of defence against British invasion, placing explosives beneath bridges along rivers and canals in County Donegal to County Louth. The first line of defence, through Leitrim and Cavan, was centred on the

Irish preparations for defence of the island included protecting against the possibility of British or German attack. The Irish Army drew up contingency plans for an invasion from across the border although only two of its eight brigades were normally based in the northern half of the country. The Second Division did prepare two lines of defence against British invasion, placing explosives beneath bridges along rivers and canals in County Donegal to County Louth. The first line of defence, through Leitrim and Cavan, was centred on the

Irish Army Air Corps use of the Gloster Gladiator during the Second World War

{{World War II Western European theatre of World War II Cancelled military operations involving the United Kingdom Cancelled military operations of World War II United Kingdom in World War II Independent Ireland in World War II Ireland–United Kingdom relations

Plan W, during

Plan W, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, was a plan of joint military operations between the governments of Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

devised between 1940 and 1942, to be executed in the event of an invasion of Ireland by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

.

Although Ireland was officially neutral, after the German Blitzkrieg

''Blitzkrieg'(Lightning/Flash Warfare)'' is a word used to describe a combined arms surprise attack, using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with ...

s of 1939–40 that resulted in the defeat of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, the British recognised that Germany planned an invasion of Britain (Operation Sea Lion

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (), was Nazi Germany's code name for their planned invasion of the United Kingdom. It was to have taken place during the Battle of Britain, nine months after the start of the Second World ...

) and were also concerned about the possibility of a German invasion of Ireland. German planning for Operation Green began in May 1940 and the British began intercepting communications about it in June. The British were interested in securing Ireland, as its capture by German forces would expose their western flank and provide a base of operations for the Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

in the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

and in any operations launched to invade Great Britain as part of Operation Sea Lion.

Irish-British co-operation was a controversial proposal for both sides, as most members of the Irish political establishment had been combatants in the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

between 1919 and 1921. However, because of the threat of German occupation and seizure of Ireland and especially the valuable Irish ports, Plan W was developed. Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

was to serve as the base of a new British Expeditionary Force that would move across the Irish border

Irish commonly refers to:

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the island and the sovereign state

***Erse (disambiguatio ...

to repel the invaders from any beach-head established by German paratrooper

A paratrooper or military parachutist is a soldier trained to conduct military operations by parachuting directly into an area of operations, usually as part of a large airborne forces unit. Traditionally paratroopers fight only as light infa ...

s. In addition, coordinated actions of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

and Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

were planned to repel German air and sea invasion. According to a restricted file prepared by the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

's "Q" Movements Transport Control in Belfast, the British would not have crossed the border "until invited to do so by the Irish Government," and it is not clear who would have had the operational authority over the British troops invited into the State by Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

.de Valera had agreed to the plan "wholeheartedly" although was more reluctant in private about which would be worse – a German or a British occupying force. The document added that most people in Ireland probably would have helped the British Army, but "there would have been a small disaffected element capable of considerable guerrilla activities against the British."Fisk pp. 237–238. This is certainly true. While the IRA of the time considered de Valera and the rest of those who had accepted partition of the island as traitors, the act of extending an invitation to British troops back into the 26 counties would have emboldened them even further.

By April 1941 the new British Troops in Northern Ireland (BTNI) commander, General Sir Henry Pownall

Lieutenant General Sir Henry Royds Pownall, (19 November 1887 – 10 June 1961) was a senior British Army officer who held several command and staff positions during the Second World War. In particular, he was chief of staff to the British Expe ...

, extended his planning for a German invasion to cover fifty percent of the entire Irish coastline. He believed that German troops were likely to land in Cork

"Cork" or "CORK" may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Stopper (plug), or "cork", a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

*** Wine cork an item to seal or reseal wine

Places Ireland

* ...

, Limerick

Limerick ( ; ) is a city in western Ireland, in County Limerick. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and is in the Mid-West Region, Ireland, Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. W ...

, Waterford

Waterford ( ) is a City status in Ireland, city in County Waterford in the South-East Region, Ireland, south-east of Ireland. It is located within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster. The city is situated at the head of Waterford H ...

, Westport, Galway

Galway ( ; , ) is a City status in Ireland, city in (and the county town of) County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lough Corrib and Galway Bay. It is the most populous settlement in the province of Connacht, the List of settleme ...

, Sligo

Sligo ( ; , meaning 'abounding in shells') is a coastal seaport and the county town of County Sligo, Ireland, within the western province of Connacht. With a population of 20,608 in 2022, it is the county's largest urban centre (constituting 2 ...

, and County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county of the Republic of Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is the northernmost county of Ireland. The county mostly borders Northern Ireland, sharing only a small b ...

, i.e. on the southern or western coasts. British Army personnel also carried out secret intelligence-gathering trips to glean information on the rail system south of the border.

Context

Political context and early planning

Discussions over the possible German invasion of Ireland had been ongoing in Britain since the beginning of 1939. In June 1940, Britain's political and military establishment had witnessed the seemingly invincible GermanBlitzkrieg

''Blitzkrieg'(Lightning/Flash Warfare)'' is a word used to describe a combined arms surprise attack, using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with ...

which led to the defeat of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

, and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and the retreat of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

. The British suspected that, following their defeat in France, the next step would be a German invasion of Britain – Operation Sea Lion

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (), was Nazi Germany's code name for their planned invasion of the United Kingdom. It was to have taken place during the Battle of Britain, nine months after the start of the Second World ...

. They did not know, but also suspected, that there was a plan to invade neutral Ireland – Operation Green.

In this context, they embarked on the policy of planning, together with the Irish authorities, for the defence of the island. This was a controversial proposal as most of the Irish political establishment had been combatants in the Anglo-Irish War

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along wi ...

against the British between 1916 and 1921. For instance, the Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil ( ; ; meaning "Soldiers of Destiny" or "Warriors of Fál"), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party (), is a centre to centre-right political party in Ireland.

Founded as a republican party in 1926 by Éamon de ...

politicians in the Irish government included Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

, Seán T. O'Kelly

Seán Thomas O'Kelly (; 25 June 1882 – 23 November 1966), originally John T. O'Kelly, was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as the second president of Ireland from June 1945 to June 1959. He also served as deputy prime minister of Ir ...

, Seán Lemass

Seán Francis Lemass (born John Francis Lemass; 15 July 1899 – 11 May 1971) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach and Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1959 to 1966. He also served as Tánaiste from 1957 to 1959, 1951 to 1954 ...

, Gerald Boland

Gerald Boland (25 May 1885 – 5 January 1973) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Minister for Justice (Ireland), Minister for Justice from 1939 to 1948 and 1951 to 1954, Minister for the Environment, Climate and Communications, ...

, Oscar Traynor

Oscar Traynor (21 March 1886 – 14 December 1963) was an Irish republican and Fianna Fáil politician who served as Minister for Justice from 1957 to 1961, Minister for Defence from 1939 to 1948 and 1951 to 1954, Minister for Posts and Telegr ...

, Frank Aiken

Francis Thomas Aiken (13 February 1898 – 18 May 1983) was an Irish revolutionary and politician. He was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army, chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army (1922–1969), Anti-Treaty IRA at the end of the I ...

, Seán MacEntee

Seán Francis MacEntee (; 23 August 1889 – 9 January 1984) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Tánaiste from 1959 to 1965, Minister for Social Welfare from 1957 to 1961, Minister for Health from 1957 to 1965, Minister for Lo ...

, and Thomas Derrig

Thomas Derrig (; 26 November 1897 – 19 November 1956) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Minister for Lands from 1939 to 1943 and 1951 to 1954, Minister for Education from 1932 to 1939 and 1940 to 1948 and Minister for Posts ...

, all of whom had been active against the British. On the British side, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, and many senior members of his administration had forcibly opposed their bid for an independent Irish state, including setting up the controversial Black and Tans

The Black and Tans () were constables recruited into the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) as reinforcements during the Irish War of Independence. Recruitment began in Great Britain in January 1920, and about 10,000 men enlisted during the conflic ...

to oppose militant separatism.

However it was not so different from de Valera's position in 1921. During the debates on the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

in late 1921, de Valera had submitted his ideal draft, known as "Document No.2" which included:

* ''2. That, for purposes of common concern, Ireland shall be associated with the States of the British Commonwealth, viz: the Kingdom of Great Britain, the Dominion of Canada, the Commonwealth of Australia, the Dominion of New Zealand, and the Union of South Africa.''

* ''4. That the matters of "common concern" shall include Defence, Peace and War, Political Treaties, and all matters now treated as of common concern amongst the States of the British Commonwealth, and that in these matters there shall be between Ireland and the States of the British commonwealth "such concerted action founded on consultation as the several Governments may determine".''

* ''8. That for five years, pending the establishment of Irish coastal defence forces, or for such other period as the Governments of the two countries may later agree upon, facilities for the coastal defence of Ireland shall be given to the British Government as follows:''

*: ''(a) In time of peace such harbour and other facilities as are indicated in the Annex hereto, or such other facilities as may from time to time be agreed upon between the British Government and the Government of Ireland.''

*: ''(b) In time of war such harbour and other Naval facilities as the British Government may reasonably require for the purposes of such defence as aforesaid.''

* ''9. That within five years from the date of exchange of ratifications of this treaty a conference between the British and Irish Governments shall be held to arrange for the handing over of the coastal defence of Ireland to the Irish Government unless some other arrangement for naval defence be agreed by both Governments to be desirable in the common interest of Ireland, Great Britain, and the other associated States.''

De Valera had proposed that a final settlement between Ireland and Britain would give regard to Britain's future maritime defence, in recognition of Britain's longstanding fear of invasion from the west.

Among the Irish opposition party's Fine Gael

Fine Gael ( ; ; ) is a centre-right, liberal-conservative, Christian democratic political party in Ireland. Fine Gael is currently the third-largest party in the Republic of Ireland in terms of members of Dáil Éireann. The party had a member ...

leadership, W. T. Cosgrave

William Thomas Cosgrave (5 June 1880 – 16 November 1965) was an Irish politician who served as the President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1932, Leader of the Opposition from 1932 to 1944, Leader of Fine Gael ...

, Desmond Fitzgerald, Richard Mulcahy

Richard James Mulcahy (10 May 1886 – 16 December 1971) was an Irish Fine Gael politician and army general who served as Minister for Education from 1948 to 1951 and 1954 to 1957, Minister for the Gaeltacht from June 1956 to October 1956, L ...

and several others had also fought in the previous Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

and the Irish Army

The Irish Army () is the land component of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Defence Forces of Republic of Ireland, Ireland.The Defence Forces are made up of the Permanent Defence Forces – the standing branches – and the Reserve Defence Forces. ...

had thousands of veterans from that conflict. Major General Joseph McSweeney, General Officer Commanding

General officer commanding (GOC) is the usual title given in the armies of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth (and some other nations, such as Ireland) to a general officer who holds a command appointment.

Thus, a general might be the GOC ...

(GOC) of Irish Army's Western Command in 1940, had been in the GPO during the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

. Colonels Archer and Bryan of Military Intelligence G2 had also fought in the conflicts. The IRA member Tom Barry volunteered his services to the Irish Army in 1939 and became operations officer in the 1st Division.

British strategic assessment

After the invasion of Belgium andthe Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, the British were convinced that an invasion of Ireland would come from the air, via paratrooper

A paratrooper or military parachutist is a soldier trained to conduct military operations by parachuting directly into an area of operations, usually as part of a large airborne forces unit. Traditionally paratroopers fight only as light infa ...

s. They were not satisfied with the Irish government's defence capability, particularly against airborne troops. The topic of reoccupying the 26 counties of Ireland had been a matter of political conversation in Britain since the beginning of the war. In June 1940, Malcolm MacDonald

Malcolm John MacDonald (17 August 1901 – 11 January 1981) was a British politician and diplomat. He was initially a Labour Party (UK), Labour Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP), but in 1931 followed his father ...

offered to "give back" the six counties comprising Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

– an offer of Irish unity – if Ireland would join with the Allies, but the offer was not taken seriously. The same month Major General Bernard "Monty" Montgomery was busy planning the seizure of what he referred to as "Cork and Queenstown (Cobh

Cobh ( ,), known from 1849 until 1920 as Queenstown, is a seaport town on the south coast of County Cork, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. With a population of 14,148 inhabitants at the 2022 census of Ireland, 2022 census, Cobh is on the south si ...

) in Southern Ireland" ''(sic)''. Winston Churchill was to also refer to the "... most heavy and grievous burden placed upon Britain by the Royal Navy's exclusion from the three Treaty Ports

Treaty ports (; ) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Qing dynasty of China (before th ...

n Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

"Fisk p. 242 ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British newspaper published weekly in printed magazine format and daily on Electronic publishing, digital platforms. It publishes stories on topics that include economics, business, geopolitics, technology and culture. M ...

'' reported that Britain should seize the ports if they become "a matter of life and death". The remarks were made in the face of mounting losses in the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

.

Attempts were also made on 26 June 1940 to split the consensus in Ireland over the neutrality policy via a possible coup attempt. An approach was made to Richard Mulcahy (leader of Fine Gael

The Leader of Fine Gael is the most senior politician within the Fine Gael political party in Ireland. The party leader is Simon Harris, who took up the role on 24 March 2024 after the resignation of Leo Varadkar.

The deputy leader of Fine Gael ...

at the time) by an Irish-born ex-British Army lieutenant colonel who was a city councillor in the State. Mulcahy recorded that the ex-officer:

"...called to say that 'the people in the North are prepared to make a military convention with this countryThis was in effect a proposal for a joint military command of all of Ireland, which the unidentified ex-British Army lieutenant colonel said had been stimulated after discussion with "important members of the British Army in the North of Ireland." It is possible that the simultaneous discussions could have been an attempt to pressure de Valera, thereland Adriaan Reland (also known as ''Adriaen Reeland/Reelant'', ''Hadrianus Relandus''; 17 July 1676 – 5 February 1718)John Gorton, ''A General Biographical Dictionary'', 1838, Whittaker & Co. was a Dutch Orientalist scholar, cartographer and philo ...without reference to the Northern Government... He wanted someone to go up there from here unofficially, to speak to someone in authority and say how the land lay. In reply to questioning, he stated that the people he referred to were the British Army authorities in the North."

Taoiseach

The Taoiseach (, ) is the head of government or prime minister of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the President of Ireland upon nomination by Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

. Unionist politician Sir Emerson Herdman also called to speak with de Valera about obtaining "unity of command" and to ask if Ireland would enter the war in return for an end to partition. Herdman appears to have been acting on behalf of Craigavon

Craigavon ( ) is a town in north County Armagh, Northern Ireland. It was a planned settlement, begun in 1965, and named after the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland: James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon. It was intended to be the heart of ...

, but when de Valera rebuffed him, he was of the view that:

"the only thing to do now for Britain is to send in powerful forces here, and prevent this country being seized, or prevent them he Britishhaving to use and lose large numbers of troops in putting the Germans out if they got here."Fisk pp. 243–244.Therefore the W-Plan had a dual purpose: * a joint plan of action in the event of a compliant Ireland, * an invasion plan in the event of a German invasion and subsequent resistance.

Knowledge of German planning

Planning began for Operation Green in May 1940, and the British had intelligence about it beginning in around June of that year. The British were interested in securing Ireland as its capture by German forces would expose their western flank, and provide a base of operations for the Luftwaffe in the Battle of the Atlantic and in any operations launched to conquer Britain as part of Operation Sea Lion. The British suspected that the Germans target for an invasion attempt would be Cork, particularlyCork Harbour

Cork Harbour () is a natural harbour and river estuary at the mouth of the River Lee (Ireland), River Lee in County Cork, Ireland. It is one of several which lay claim to the title of "second largest natural harbour in the world by navigational ...

with the naval base at Cobh because it was the nearest to Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

bases in north west France.

Irish defence status

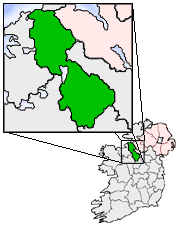

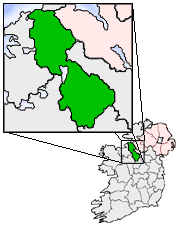

Irish preparations for defence of the island included protecting against the possibility of British or German attack. The Irish Army drew up contingency plans for an invasion from across the border although only two of its eight brigades were normally based in the northern half of the country. The Second Division did prepare two lines of defence against British invasion, placing explosives beneath bridges along rivers and canals in County Donegal to County Louth. The first line of defence, through Leitrim and Cavan, was centred on the

Irish preparations for defence of the island included protecting against the possibility of British or German attack. The Irish Army drew up contingency plans for an invasion from across the border although only two of its eight brigades were normally based in the northern half of the country. The Second Division did prepare two lines of defence against British invasion, placing explosives beneath bridges along rivers and canals in County Donegal to County Louth. The first line of defence, through Leitrim and Cavan, was centred on the Ballinamore

Ballinamore (, meaning "mouth of the big ford") is a small town in the south-east of County Leitrim in Ireland.

Etymology

, corrupted ''Bellanamore'', means "town at the mouth of the big ford", so named because it was a main crossing (ford) o ...

-Ballyconnell

Ballyconnell () is a town in County Cavan, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is situated on the N87 road (Ireland), N87 national secondary road at the junction of four townlands: Annagh, County Cavan, Annagh, Cullyleenan, Doon (Tomregan) and Der ...

canal. The second line chosen was the River Boyne

The River Boyne ( or ''Abhainn na Bóinne'') is a river in Leinster, Ireland, the course of which is about long. It rises at Trinity Well, Newberry Hall, near Carbury, County Kildare, and flows north-east through County Meath to reach the ...

. After a delaying action with a conventional static defence, the 2nd Division was to "split up into smaller groups and start guerrilla resistance against the British."Fisk p. 247

More detailed defence plans were drawn up for local areas. In Cork city, any seaborne invaders would be engaged by motor torpedo boats and the 9.2 inch and six-inch guns of the Treaty Ports

Treaty ports (; ) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Qing dynasty of China (before th ...

. If the enemy were able to effect a landing in strength, the forts would be demolished by explosives (as would the harbour quays and railway), a blockship would be sunk in the harbour channel and the Haulbowline oil refinery set on fire. The defence of the city itself would be undertaken by the local defence force (LDF) and a regular army battalion, while the First Division would carry out operations in the surrounding countryside.

Development of Plan W

The first meetings, 1940

The first meeting on establishing a joint action plan in the event of a German invasion was on 24 May 1940. The meeting was held in London and had been convened to explore every conceivable way in which the German forces may attempt an invasion of Ireland. At the meeting were Joseph Walshe, Irish secretary of External Affairs, Colonel Liam Archer of Irish Military Intelligence (G2), and officers from theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

, and the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

. The War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

wanted direct liaisons between the Irish military authorities in Dublin and the British General Officer Commanding in Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

. Walshe and Archer therefore agreed to fly in secret to Belfast with Lieutenant Colonel Dudley Clarke

Brigadier Dudley Wrangel Clarke, ( – ) was an officer in the British Army, known as a pioneer of military deception operations during the Second World War. His ideas for combining fictional orders of battle, visual deception and doubl ...

. In Belfast, two British Army staff officers were collected and the group travelled back to Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

by rail. This meeting was held underneath Government buildings in Kildare Street

Kildare Street () is a street in Dublin, Ireland.

Location

Kildare Street is close to the principal shopping area of Grafton Street and Dawson Street, to which it is joined by Molesworth Street. Trinity College lies at the north end of t ...

and included a number of Irish Army officers. The meeting was informed that General Sir Hubert Huddleston, the General Officer Commanding (GOC.) Northern Ireland, was already under orders to take a mobile column south of the border to help the Irish Army if the Germans invaded.

Clarke also met with the Irish Army Chief of Staff, General Daniel McKenna, who explained that the British would not be allowed into the south of Ireland before the Germans arrived. Clarke also met with the Irish Minister for Co-ordination of Defensive Measures, Frank Aiken, and discussed "new ideas for the mechanical improvement of the war."Fisk p. 235 The point of these meetings was to secure an understanding on the threat faced by both Britain and Ireland, and the benefit of joint action – the details would later be worked out by the respective armed services.

Clarke returned to London on 28 May 1940, where he reported that the Irish Army had given him full details of their organisation and equipment "without reservation" and had in return requested information on British troop strength in Northern Ireland. It had been agreed that in the event of a German invasion, the Irish would call for assistance from Huddleston in Belfast. The British Army's advance from Northern Ireland into neutral Ireland was to be called Plan W.

Operational details

As noted, Cork was the suspected target of an invasion because it was the nearest landfall between Luftwaffe bases in north-western France and the island of Ireland. Northern Ireland was to serve as the base of a new British Expeditionary Force, that would move into the State to repel the invaders from any beach-head that was established. Troops of the 53rd Division in Belfast were held in readiness for the advance. A brigade ofRoyal Marines

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

stationed at Milford Haven

Milford Haven ( ) is a town and community (Wales), community in Pembrokeshire, Wales. It is on the north side of the Milford Haven Waterway, an estuary forming a natural harbour that has been used as a port since the Middle Ages.

The town was ...

were also prepared to seize a bridge-head in Wexford the moment the Germans landed. Officers at the headquarters (HQ) of British troops in Northern Ireland, Thiepval Barracks

Thiepval Barracks is a British Army barracks and headquarters in Lisburn, County Antrim. It is also the site of the stone frigate HMS ''Hibernia'', Headquarters of the Royal Naval Reserve in Northern Ireland.

History

The barracks were built in 19 ...

, Lisburn

Lisburn ( ; ) is a city in Northern Ireland. It is southwest of Belfast city centre, on the River Lagan, which forms the boundary between County Antrim and County Down. First laid out in the 17th century by English and Welsh settlers, with t ...

, County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, County Antrim, Antrim, ) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, located within the historic Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the c ...

estimated that the Germans could embark five divisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

by sea to Ireland although "not more than 2 to 3 would reach land".Fisk p. 237 Up to 8,000 German airborne troops could be flown into the State, some of them by seaplanes which would land on the lakes. The British striking force of 53 Division, later augmented by the 5th Battalion, Cheshire Regiment

The Cheshire Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Prince of Wales' Division. The 22nd Regiment of Foot was raised by the Henry Howard, 7th Duke of Norfolk in 1689 and was able to boast an independent existence ...

, were to concentrate on the west of Down and Armagh borders, then drive across the border and race towards Dublin along three main roads – the Belfast – Dublin coastal road through Dundalk

Dundalk ( ; ) is the county town of County Louth, Ireland. The town is situated on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the north-east coast of Ireland, and is halfway between Dublin and Belfast, close to and south of the bor ...

, Drogheda

Drogheda ( , ; , meaning "bridge at the ford") is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin. It is located on the Dublin–Belfast corridor on the east coast of Ireland, mostly in County Louth ...

and Balbriggan

Balbriggan (; , ) is a suburban coastal town in Fingal, in the northern part of County Dublin, Ireland. It is approximately 34 km north of the city of Dublin, for which it is a commuter town. The 2022 census population was 24,322 for Bal ...

, the inland road through Ardee

Ardee (; , ) is a town and townland in County Louth, Ireland. It is located at the intersection of the N2, N52, and N33 roads. The town shows evidence of development from the thirteenth century onward but as a result of the continued develo ...

and Slane

Slane () is a village in County Meath, in Ireland. The village stands on a steep hillside on the left bank of the River Boyne at the intersection of the N2 (Dublin to Monaghan road) and the N51 (Drogheda to Navan road). As of the 2022 census ...

, and the Castleblayney

Castleblayney (; ) is a town in County Monaghan, Ireland. The town had a population of 3,926 as of the 2022 census. Castleblayney is near the border with County Armagh in Northern Ireland, and lies on the N2 road from Dublin to Derry and L ...

— Carrickmacross

Carrickmacross () is a town in County Monaghan, Ireland. The population was 5,745 at the 2022 census of Ireland, 2022 census, making it the second-largest town in the county. Carrickmacross is a market town which developed around a castle buil ...

— Navan

Navan ( ; , meaning "the Cave") is the county town and largest town of County Meath, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is at the confluence of the River Boyne and Leinster Blackwater, Blackwater, around 50 km northwest of Dublin. At the ...

road. It is not clear who would have had the operational authority over the British troops invited into Ireland by de Valera, but it is assumed the British would retain command.

By December 1940 the plan had been extended. While the first British striking force headed for Dublin, the British 61st Division, in a separate operation, would move across the border into County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county of the Republic of Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is the northernmost county of Ireland. The county mostly borders Northern Ireland, sharing only a small b ...

and secure the Treaty port of Lough Swilly

Lough Swilly () in Ireland is a glacial fjord or sea inlet lying between the western side of the Inishowen Peninsula and the Fanad Peninsula, in County Donegal. Along with Carlingford Lough and Killary Harbour it is one of three glacial fjords ...

for the Royal Navy, providing the British Government with a third of the naval defence requirements that they had been requesting from de Valera for more than a year. The British Troops in Northern Ireland (BTNI) war diary of the time lists 278 Irish troops at Lough Swilly and only 976 Irish troops in the rest of Donegal.

The diary goes on to say that in the event of an invasion "close co-operation is to be maintained with Éire forces including Local Security Force if friendly". It is a feature of other British documents from the time; for example one reads "If Éire be hostile it may be necessary for Royal Signals

The Royal Corps of Signals (often simply known as the Royal Signals – abbreviated to R SIGNALS) is one of the combat support arms of the British Army. Signals units are among the first into action, providing the battlefield communications an ...

units to take over the civil telephone system".

According to a restricted file prepared by the British Army's 'Q' Movements Transport Control in Belfast, the British would not have crossed the border "until invited to do so by the Éire Government", but the document added that although most people in the State probably would have helped the British Army, "there would have been a small disaffected element capable of considerable guerrilla activities against us."

Sir John Loader Maffey, the British representative to Ireland since 1939, was to transmit the code word "Pumpkins" (later replaced by "Measure") to begin the troop movement of the 53rd Division onto Irish soil. This codeword would be received by Huddleston and Lieutenant General Harold Franklyn, the BTNI commander.

Elaborate plans were made in Belfast to supply the BEF with guns, ammunition, petrol, and medical equipment by rail. The British marshalling yards

A classification yard (American English, as well as the Canadian National Railway), marshalling yard (British, Hong Kong, Indian, and Australian English, and the former Canadian Pacific Railway) or shunting yard (Central Europe) is a railway y ...

at Balmoral, south of Belfast, were extended to take long ammunition and fuel trains which were loaded and ready on new sidings. In addition three ambulance trains were equipped and positioned around Belfast and an ambulance railhead established to take the wounded returning from the south of Ireland. British soldiers stripped the sides from dozens of coal trucks transforming them into flat cars for armoured vehicles and tanks that would be sent southwards. Once the 53rd Division was committed in Ireland, the British military authorities planned to run thirty-eight supply trains on the two railway lines to Dublin every day – thirty down the main line through Drogheda (if the viaduct over the River Boyne remained undamaged), and the remainder along the track which cut through County Cavan

County Cavan ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is part of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Cavan and is based on the hi ...

. The Port of Belfast was estimated to have needed to handle 10,000 tons of stores a week and could receive up to 5,000 troops every day for the battle-front.

The RAF were to fly three Hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system with a low-pressure area, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depending on its ...

fighter squadrons into Baldonnel Airfield southwest of Dublin and two Fairey Battle

The Fairey Battle is a British single-engine light bomber that was designed and manufactured by the Fairey Aviation Company. It was developed during the mid-1930s for the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a monoplane successor to the Hawker Hart and Ha ...

light bomber squadrons into Collinstown to attack German troops in Cork. The British 1st Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment was to be moved into the State to defend the Drogheda viaduct, Collinstown, and Baldonnel. The Royal Navy was to issue instructions that all British and foreign ships depart from Irish ports. Vessels in Londonderry were to head for the Clyde and boats in Belfast were to head for Holyhead

Holyhead (; , "Cybi's fort") is a historic port town, and is the list of Anglesey towns by population, largest town and a Community (Wales), community in the county of Isle of Anglesey, Wales. Holyhead is on Holy Island, Anglesey, Holy Island ...

and Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

. As many ships as possible would be cleared from Irish ports and taken to the Clyde, Holyhead and Fishguard. Royal Navy officers in Dublin were to direct this exodus and the taking on of refugees was not to be encouraged. British submarines were to patrol off Cork and the Shannon in readiness for an invasion, and should one occur, the Royal Navy was to declare a "sink on sight" zone in the western approaches and off the south and west coasts of Ireland.

By April 1941, the new BTNI commander, General Sir Henry Pownall

Lieutenant General Sir Henry Royds Pownall, (19 November 1887 – 10 June 1961) was a senior British Army officer who held several command and staff positions during the Second World War. In particular, he was chief of staff to the British Expe ...

extended his planning for a German invasion to cover fifty percent of the entire Irish coastline. He believed that German troops were likely to land in Cork, Limerick

Limerick ( ; ) is a city in western Ireland, in County Limerick. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and is in the Mid-West Region, Ireland, Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. W ...

, Waterford

Waterford ( ) is a City status in Ireland, city in County Waterford in the South-East Region, Ireland, south-east of Ireland. It is located within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster. The city is situated at the head of Waterford H ...

, Westport, Galway

Galway ( ; , ) is a City status in Ireland, city in (and the county town of) County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lough Corrib and Galway Bay. It is the most populous settlement in the province of Connacht, the List of settleme ...

, Sligo

Sligo ( ; , meaning 'abounding in shells') is a coastal seaport and the county town of County Sligo, Ireland, within the western province of Connacht. With a population of 20,608 in 2022, it is the county's largest urban centre (constituting 2 ...

, and Donegal. British Army personnel also carried out secret intelligence gathering trips to glean information on the rail system south of the border.

Irish planning

By May 1940 Irish troops were already organised in mobile columns to deal with parachute landings.Fisk p. 234 By October 1940, four more regular army brigades had been raised in the State and LSF recruiting figures were increasing. The German style helmets of the army had been replaced by the pale green uniforms and rimmed style helmets of the British Army. They had a total of sixteen medium armoured cars, and thirty Ford andRolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

light armoured cars. By early 1941, two infantry divisions had been activated. First Division was headquartered in Cork and included:

1st Brigade (HQ Clonmel: 10th, 13th, 21st Battalions), 3rd Brigade (HQ Cork: 4th, 19th, 31st Battalions), 7th Brigade (HQ Limerick: 9th, 12th, 15th Battalions)

Second Division was headquartered in Dublin and comprised:

2nd Brigade (HQ Dublin 2nd, 5th, 11th Battalions), 4th Brigade (HQ Mullingar 6th, 8th, 20th Battalions), 6th Brigade (HQ Dublin 7th, 18th, 22nd Battalions)

There were also two independent brigades:

5th Brigade (southeast Ireland 3rd, 16th, 25th Battalions)

8th Brigade: (Rineanna 1st, 23rd Battalions)

There were also three garrison battalions and the Coastal Defence Artillery forts at Cork, Bere Island, Donegal, Shannon and Waterford. The Irish Defence Forces, regular and reserve, were an all-volunteer force.

If the Germans had landed where the British and Irish expected them to, they would have been engaged by the Irish Army's Fifth Brigade who had primary responsibility for the defence of Waterford and Wexford. They would have been soon supported by General Michael Joe Costello

Michael Joseph Costello (4 July 1904 – 20 October 1986) was an Ireland, Irish rebel and military leader during the Irish War of Independence.

Biography

Michael Joseph Costello was born on 4 July 1904 in Cloughjordan, County Tipperary, son o ...

's 1st Irish Division from Cork and General Hugo MacNeill's 2nd Division. The British would establish their railhead near the Fairyhouse

Fairyhouse Racecourse is a horse racing venue in Ireland. It is situated in the parish of Ratoath in County Meath, on the R155 regional road, off the N3. It hosted its first race in 1848 and since 1870 has been the home of the Irish Grand ...

race course and be given billets at Lusk, Howth

Howth ( ; ; ) is a peninsular village and outer suburb of Dublin, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The district as a whole occupies the greater part of the peninsula of Howth Head, which forms the northern boundary of Dublin Bay, and includes the ...

, and Portmarnock

Portmarnock () is a coastal town in County Dublin, Ireland, north of the city of Dublin, with significant beaches, a modest commercial core and inland residential estates, and two golf courses, including one of Ireland's best-known golf clubs. , ...

north of Dublin.

The Irish Air Corps

The Air Corps () is the air force of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Organisationally a military branch of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Defence Forces of Ireland, the Air Corps utilises a fleet of fixed-wing aircraft and rotorcraft to carry out ...

consisted largely of nine Avro Anson

The Avro Anson is a British twin-engine, multi-role aircraft built by the aircraft manufacturer Avro. Large numbers of the type served in a variety of roles for the Royal Air Force (RAF), Fleet Air Arm (FAA), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), R ...

light bombers and four Gloster Gladiator

The Gloster Gladiator is a British biplane fighter. It was used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) (as the Sea Gladiator variant) and was exported to a number of other air forces during the late 1930s.

Developed privat ...

s, which provided the only fighter defence for the country. However, in 1940 six second-hand Hawker Hind

The Hawker Hind is a British light bomber of the inter-war years produced by Hawker Aircraft for the Royal Air Force. It was developed from the Hawker Hart day bomber introduced in 1931 in aviation, 1931.

Design and development

An improved Ha ...

s were added to the Air Corps and later in the war the Irish cannibalised and repaired several Allied aircraft that had crash landed in their territory, eventually putting two RAF Hurricanes, a Fairey Battle and an American-built Lockheed Hudson

The Lockheed Hudson is a light bomber and coastal reconnaissance aircraft built by the American Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. It was initially put into service by the Royal Air Force shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War and ...

into service. From 1942 onwards a total of twenty Hawker Hurricanes

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

entered Irish Air Corps service.

The Marine Service only acquired its first Motor Torpedo Boat in January 1940, increasing to a total of six by 1942. However, the only patrol vessels were the ''"Muirchu"'' and the ''"Fort Rannoch"'', two former British gunboats.The ''"Muirchu"'' had shelled Pearse and his colleagues in the Dublin GPO during the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

in 1916. Besides these vessels there was one "mine planter" and a barge. The Marine Service did not acquire any other ships during the war.

The Local Security Force was intended to harass and delay enemy forces by dynamiting bridges (already chambered for the purpose) and organising small ambushes and sniping attacks. Armament was paltry at first, with many units making do with requisitioned shotguns, but from 1941 on, American M1917 Enfield

The M1917 Enfield, the "American Enfield", formally named "United States Rifle, cal .30, Model of 1917" is an American modification and production of the .303-inch (7.7 mm) Pattern 1914 Enfield (P14) rifle (listed in British Service as Rifle No ...

rifles became available. In January 1941, the LSF was split into two, the 'A' force moving from police to military control and taking the new title Local Defence Force. The B Group retained the title LSF and functioned essentially as an unarmed police reserve throughout the Emergency. In general, those aged under forty went with the LDF, those older remained with the LSF.

See also

*Operation Dove (Ireland)

Operation Dove (''"Unternehmen Taube"'' in German) also sometimes known as Operation Pigeon, was an ''Abwehr'' sanctioned mission devised in early 1940. The plan envisioned the transport of IRA Chief of Staff Seán Russell to Ireland, and on the ...

* Operation Mainau

Operation Mainau (German: Unternehmen „Mainau“) was a German espionage mission during the Second World War. It was sanctioned and planned by the German secret service (''Abwehr'') and executed successfully in May 1940. The mission plan involve ...

* Plan Kathleen

Plan Kathleen, sometimes referred to as the Artus Plan, was a military plan for the invasion of Northern Ireland by Nazi Germany, sanctioned in 1940 by Stephen Hayes (Irish republican), Stephen Hayes, Acting Irish Republican Army (1922–1969), I ...

References

Further reading

*Robert Fisk

Robert William Fisk (12 July 194630 October 2020) was an English writer and journalist. He was critical of United States foreign policy in the Middle East, and the Israeli government's treatment of Palestinians.

As an international correspo ...

, ''In Time of War'' (Gill and Macmillan) 1983

External links

Irish Army Air Corps use of the Gloster Gladiator during the Second World War

{{World War II Western European theatre of World War II Cancelled military operations involving the United Kingdom Cancelled military operations of World War II United Kingdom in World War II Independent Ireland in World War II Ireland–United Kingdom relations