Placozoan Range Map on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Placozoa ( ; ) is a

Placozoans do not have well-defined body plans, much like

Placozoans do not have well-defined body plans, much like

On the basis of their simple structure, the Placozoa were frequently viewed as a model organism for the transition from unicellular organisms to the multicellular animals (

On the basis of their simple structure, the Placozoa were frequently viewed as a model organism for the transition from unicellular organisms to the multicellular animals ( While the probability of encountering food, potential sexual partners, or predators is the same in all directions for animals floating freely in the water, there is a clear difference on the seafloor between the functions useful on body sides facing toward and away from the

While the probability of encountering food, potential sexual partners, or predators is the same in all directions for animals floating freely in the water, there is a clear difference on the seafloor between the functions useful on body sides facing toward and away from the

The ''Trichoplax adhaerens'' Grell-BS-1999 v1.0 Genome Portal at the DOE Joint Genome Institute

The ''Trichoplax'' Genome Project at the Yale Peabody Museum

Research articles from the ITZ, TiHo Hannover

* –

Historical overview of ''Trichoplax'' research

* [https://archive.today/20130415130142/http://icb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/icm015v1 Vicki Buchsbaum Pearse, and Oliver Voigt, 2007. "Field biology of placozoans (Trichoplax): distribution, diversity, biotic interactions. Integrative and Comparative Biology"], . {{Taxonbar, from=Q131040 Placozoa, ParaHoxozoa Animal phyla Parazoa Ediacaran first appearances

phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

of free-living (non-parasitic) marine invertebrate

Marine invertebrates are invertebrate animals that live in marine habitats, and make up most of the macroscopic life in the oceans. It is a polyphyletic blanket term that contains all marine animals except the marine vertebrates, including the ...

s. They are blob-like animals composed of aggregations of cells. Moving in water by ciliary motion, eating food by engulfment, reproducing by fission or budding

Budding or blastogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction in which a new organism develops from an outgrowth or bud due to cell division at one particular site. For example, the small bulb-like projection coming out from the yeast cell is kno ...

, placozoans are described as "the simplest animals on Earth." Structural and molecular analyses have supported them as among the most basal animals, thus, constituting a primitive metazoan

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, have myocytes and are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and grow from a ho ...

phylum.

The first known placozoan, ''Trichoplax adhaerens

''Trichoplax adhaerens'' is one of the four named species in the phylum Placozoa. The others are ''Hoilungia hongkongensis'', ''Polyplacotoma mediterranea'' and ''Cladtertia collaboinventa''. Placozoa is a basal group of multicellular animals, p ...

'', was discovered in 1883 by the German zoologist Franz Eilhard Schulze

Franz Eilhard Schulze (22 March 1840 – 2 November 1921) was a German anatomist and zoologist born in Eldena, near Greifswald.

Biography

He studied at the Universities of Bonn and Rostock. In 1863, he received his doctorate from Rostock, wher ...

(1840–1921).F. E. Schulze "''Trichoplax adhaerens'' n. g., n. s.", ''Zoologischer Anzeiger'' (Elsevier, Amsterdam and Jena) 6 (1883), p. 92. Describing the uniqueness, another German, Karl Gottlieb Grell

Karl Gottlieb Grell (28 December 1912, Burg an der Wupper – 4 October 1994) was a German zoologist and protistologist, known for his work on '' Trichoplax''.

Karl Grell received his doctorate ( Promotion) in 1934 from the University of Bonn ...

(1912–1994), erected a new phylum, Placozoa, for it in 1971. Remaining a monotypic

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unisp ...

phylum for over a century, new species began to be added since 2018. So far, three other extant species have been described, in two distinct classes: Uniplacotomia (''Hoilungia hongkongensis

''Hoilungia'' is a genus that contains one of the simplest animals and belongs to the phylum Placozoa. Described in 2018, it has only Monotypic taxon, one named species, ''H. hongkongensis'', although there are possible other species. The animal ...

'' in 2018 and ''Cladtertia collaboinventa

''Cladtertia'' is a genus of placozoan discovered in 2022. The genus contains a single described species, ''Cladtertia collaboinventa'', although several other undescribed lineages are known. Its closest described relative is '' Hoilungia hongkon ...

'' in 2022) and Polyplacotomia (''Polyplacotoma mediterranea

''Polyplacotoma mediterranea'' is a species in the phylum Placozoa, only representative of the genus ''Polyplacotoma'', and was discovered in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surro ...

'', the most basal, in 2019). A single putative fossil species is known, the Middle Triassic

In the geologic timescale, the Middle Triassic is the second of three epoch (geology), epochs of the Triassic period (geology), period or the middle of three series (stratigraphy), series in which the Triassic system (stratigraphy), system is di ...

''Maculicorpus microbialis

''Maculicorpus'' is a genus of fossil placozoan from the Middle Triassic of Germany, and the first placozoan known from the fossil record. It comprises a single known species, ''Maculicorpus microbialis''.

Discovery

''Maculicorpus'' is known fr ...

''.

History

''Trichoplax'' was discovered in 1883 by the German zoologistFranz Eilhard Schulze

Franz Eilhard Schulze (22 March 1840 – 2 November 1921) was a German anatomist and zoologist born in Eldena, near Greifswald.

Biography

He studied at the Universities of Bonn and Rostock. In 1863, he received his doctorate from Rostock, wher ...

, in a seawater aquarium at the Zoological Institute in Graz, Austria

Graz () is the capital of the Austrian federal state of Styria and the second-largest city in Austria, after Vienna. On 1 January 2025, Graz had a population of 306,068 (343,461 including secondary residence). In 2023, the population of the Gra ...

. The generic name is derived from the classical Greek ('), meaning "hair", and ('), "plate". The specific epithet ''adhaerens'' is Latin meaning "adherent", reflecting its propensity to stick to the glass slides and pipettes used in its examination. Schulze realized that the animal could not be a member of any existing phyla, and based on the simple structure and behaviour, concluded in 1891 that it must be an early metazoan. He also observed the reproduction by fission, cell layers and locomotion.

In 1893, Italian zoologist Francesco Saverio Monticelli described another animal which he named ''Treptoplax'', the specimens of which he collected from Naples. He gave the species name ''T. reptans'' in 1896. Monticelli did not preserve them and no other specimens were found again, as a result of which the identification is ruled as doubtful, and the species rejected.

Schulze's description was opposed by other zoologists. For instance, in 1890, F.C. Noll argued that the animal was a flat worm (Turbellaria). In 1907, Thilo Krumbach published a hypothesis that ''Trichoplax'' is not a distinct animal but that it is a form of the planula larva of the anemone

''Anemone'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the buttercup family Ranunculaceae. Plants of the genus are commonly called windflowers. They are native to the temperate and subtropical regions of all regions except Australia, New Zealand, and ...

-like hydrozoan

Hydrozoa (hydrozoans; from Ancient Greek ('; "water") and ('; "animals")) is a taxonomic class of individually very small, predatory animals, some solitary and some colonial, most of which inhabit saline water. The colonies of the colonial sp ...

''Eleutheria krohni''. Although this was refuted in print by Schulze and others, Krumbach's analysis became the standard textbook explanation, and nothing was printed in zoological journals about ''Trichoplax'' until the 1960s.

The development of electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of electrons as a source of illumination. It uses electron optics that are analogous to the glass lenses of an optical light microscope to control the electron beam, for instance focusing i ...

in the mid-20th century allowed in-depth observation of the cellular components of organisms, following which there was renewed interest in ''Trichoplax'' starting in 1966. The most important descriptions were made by Karl Gottlieb Grell

Karl Gottlieb Grell (28 December 1912, Burg an der Wupper – 4 October 1994) was a German zoologist and protistologist, known for his work on '' Trichoplax''.

Karl Grell received his doctorate ( Promotion) in 1934 from the University of Bonn ...

at the University of Tübingen since 1971. That year, Grell revived Schulze's interpretation that the animals are unique and created a new phylum Placozoa. Grell derived the name from the placula hypothesis, Otto Bütschli

Johann Adam Otto Bütschli (3 May 1848 – 2 February 1920) was a German zoologist and professor at the University of Heidelberg. He specialized in invertebrates and insect development. Many of the groups of protists were first recognized by him.

...

's notion on the origin of metazoans.

Biology

Anatomy

amoebas

An amoeba (; less commonly spelled ameba or amœba; : amoebas (less commonly, amebas) or amoebae (amebae) ), often called an amoeboid, is a type of cell or unicellular organism with the ability to alter its shape, primarily by extending and re ...

, unicellular eukaryotes. As Andrew Masterson reported: "they are as close as it is possible to get to being simply a little living blob." An individual body measures about 0.55 mm in diameter. There are no body parts; as one of the researchers Michael Eitel described: "There's no mouth, there's no back, no nerve cells, nothing." Animals studied in laboratories have bodies consisting of everything from hundreds to millions of cells.

Placozoans have only three anatomical parts as tissue layers inside its body: the upper, intermediate (middle) and lower epithelia

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial ( mesothelial) tissues line the outer surfaces of many ...

. There are at least six different cell types. (A 2023 analysis of 4 species across 3 genera found 8, one with an unknown role.) The upper epithelium is the thinnest portion and essentially comprises flat cells with their cell body hanging underneath the surface, and each cell having a cilium

The cilium (: cilia; ; in Medieval Latin and in anatomy, ''cilium'') is a short hair-like membrane protrusion from many types of eukaryotic cell. (Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea.) The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike pr ...

. Crystal cells are sparsely distributed near the marginal edge. A few cells have unusually large number of mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

. The middle layer is the thickest made up of numerous fiber cells, which contain mitochondrial complexes, vacuoles and endosymbiotic bacteria in the endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a part of a transportation system of the eukaryote, eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. The word endoplasmic means "within the cytoplasm", and reticulum is Latin for ...

. The lower epithelium consists of numerous monociliated cylinder cells along with a few endocrine-like gland cells and lipophil cells. Each lipophil cell contains numerous middle-sized granules, one of which is a secretory granule

Secretion is the movement of material from one point to another, such as a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast, excretion is the removal of certain substances or waste products from a cell or organism. The classical mech ...

.

The body axes of ''Hoilungia'' and ''Trichoplax'' are overtly similar to the oral–aboral axis of cnidarians

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

, animals from another phylum with which they are most closely related. Structurally, they can not be distinguished from other placozoans, so that identification is purely on genetic (mitochondrial DNA) differences. Genome sequencing has shown that each species has a set of unique genes and several uniquely missing genes.

''Trichoplax'' is a small, flattened, animal around across. An amorphous multi-celled body, analogous to a single-celled ''amoeba

An amoeba (; less commonly spelled ameba or amœba; : amoebas (less commonly, amebas) or amoebae (amebae) ), often called an amoeboid, is a type of Cell (biology), cell or unicellular organism with the ability to alter its shape, primarily by ...

'', it has no regular outline, although the lower surface is somewhat concave, and the upper surface is always flattened. The body consists of an outer layer of simple epithelium

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial ( mesothelial) tissues line the outer surfaces of man ...

enclosing a loose sheet of stellate cells resembling the mesenchyme

Mesenchyme () is a type of loosely organized animal embryonic connective tissue of undifferentiated cells that give rise to most tissues, such as skin, blood, or bone. The interactions between mesenchyme and epithelium help to form nearly ever ...

of some more complex animals. The epithelial cells bear cilia

The cilium (: cilia; ; in Medieval Latin and in anatomy, ''cilium'') is a short hair-like membrane protrusion from many types of eukaryotic cell. (Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea.) The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike proj ...

, which the animal uses to help it creep along the seafloor.

The lower surface engulfs small particles of organic detritus, on which the animal feeds.

Studies suggest that aragonite

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral and one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate (), the others being calcite and vaterite. It is formed by biological and physical processes, including precipitation fr ...

crystals in crystal cells have the same function as statoliths, allowing it to use gravity for spatial orientation

In geometry, the orientation, attitude, bearing, direction, or angular position of an object – such as a line, plane or rigid body – is part of the description of how it is placed in the space it occupies.

More specifically, it refers to t ...

.

Located in the dorsal epithelium there are lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

granules which release a cocktail of toxins

A toxin is a naturally occurring poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. They occur especially as proteins, often conjugated. The term was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919), derived ...

as a means of defense, and can induce paralysis or death in some predators. Genes encoding for proteins which make up the poisonous secretions of ''Trichoplax'' have been found to strongly resemble venom-associated genes present in the genomes of certain snakes, like the American copperhead and the West African carpet viper.

Proto-nervous system

The Placozoa have a very primitive analogue of the nervous system. It has peptideric cells that resemble neurons in that they haveG protein-coupled receptor

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also known as seven-(pass)-transmembrane domain receptors, 7TM receptors, heptahelical receptors, serpentine receptors, and G protein-linked receptors (GPLR), form a large group of evolutionarily related ...

s and release vesicles and neuropeptides. They are descended from progenitor cells with an expression pattern similar to that of neuron progenitor cells and themselves express genes associated with the pre-synaptic scaffold. Still, they differ from Cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

n neurons by having no projections and not expressing genes of the post-synptic scaffold. There are a total of 14 types of these "peptideric cells".

Reproduction

All placozoans can reproduce asexually, budding off smaller individuals, and the lower surface may also bud off eggs into themesenchyme

Mesenchyme () is a type of loosely organized animal embryonic connective tissue of undifferentiated cells that give rise to most tissues, such as skin, blood, or bone. The interactions between mesenchyme and epithelium help to form nearly ever ...

.

Sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

has been reported to occur in one clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

of placozoans,

whose strain H8 was later found to belong to genus '' Cladtertia'', where intergenic recombination was observed as well as other hallmarks of sexual reproduction.

In addition to fission, representatives of all species produced “swarmers” (a separate vegetative reproduction stage), which could also be formed from the lower epithelium with greater cell-type diversity.

Endosymbioants

Some ''Trichoplax'' species contain ''Rickettsiales

The Rickettsiales, informally called rickettsias, are an order of small Alphaproteobacteria. They are obligate intracellular parasites, and some are notable pathogens, including '' Rickettsia'', which causes a variety of diseases in humans, and ...

'' bacteria as endosymbiont

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

s.

One of the at least 20 described species turned out to have two bacterial endosymbionts; '' Grellia'' which lives in the animal's endoplasmic reticulum and is assumed to play a role in the protein and membrane production. The other endosymbiont is the first described '' Margulisbacteria'', that lives inside cells used for algal digestion. It appears to eat the fats and other lipids of the algae and provide its host with vitamins and amino acids in return.

Evolution and population dynamics

The Placozoa show substantial evolutionary radiation in regard tosodium channel

Sodium channels are integral membrane proteins that form ion channels, conducting sodium ions (Na+) through a cell (biology), cell's cell membrane, membrane. They belong to the Cation channel superfamily, superfamily of cation channels.

Classific ...

s, of which they have 5–7 different types, more than any other invertebrate species studied to date.

Three modes of population dynamics depended upon feeding sources, including induction of social behaviors, morphogenesis, and reproductive strategies.

Distribution

Evolutionary relationships

There is no convincing fossil record of the Placozoa, although theEdiacaran biota

The Ediacaran (; formerly Vendian) biota is a taxonomic period classification that consists of all life forms that were present on Earth during the Ediacaran Period (). These were enigmatic tubular and frond-shaped, mostly sessile, organis ...

(Precambrian, ) organism ''Dickinsonia

''Dickinsonia'' is a genus of extinct organism that lived during the late Ediacaran period in what is now Australia, China, Russia, and Ukraine. It had a round, bilaterally symmetric body with multiple segments running along it. It could range f ...

'' appears somewhat similar to placozoans.

Knaust (2021) reported preservation of placozoan fossils in a microbialite bed from the Middle Triassic

In the geologic timescale, the Middle Triassic is the second of three epoch (geology), epochs of the Triassic period (geology), period or the middle of three series (stratigraphy), series in which the Triassic system (stratigraphy), system is di ...

Muschelkalk

The Muschelkalk (German for "shell-bearing limestone"; ) is a sequence of sedimentary rock, sedimentary rock strata (a lithostratigraphy, lithostratigraphic unit) in the geology of central and western Europe. It has a Middle Triassic (240 to 230 m ...

(Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

).

Traditionally, classification was based on their level of organization, i.e., they possess no tissues or organs. However this may be as a result of secondary loss and thus is inadequate to exclude them from relationships with more complex animals. More recent work has attempted to classify them based on the DNA sequences in their genome; this has placed the phylum between the sponge

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and a ...

s and the Eumetazoa

Eumetazoa (), also known as Epitheliozoa or Histozoa, is a proposed basal animal subkingdom as a sister group of Porifera (sponges). The basal eumetazoan clades are the Ctenophora and the ParaHoxozoa. Placozoa is now also seen as a eumetazoan ...

.

In such a feature-poor phylum, molecular data are considered to provide the most reliable approximation of the placozoans' phylogeny.

Their exact position on the phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA. In ...

would give important information about the origin of neurons and muscles. If the absence of these features is an original trait of the Placozoa, it would mean that a nervous system and muscles evolved three times should placozoans and cnidarians be a sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

; once in the Ctenophora

Ctenophora (; : ctenophore ) is a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and they are ...

, once in the Cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

and once in the Bilateria

Bilateria () is a large clade of animals characterised by bilateral symmetry during embryonic development. This means their body plans are laid around a longitudinal axis with a front (or "head") and a rear (or "tail") end, as well as a left� ...

. If they branched off before the Cnidaria and Bilateria split, the neurons and muscles would have the same origin in the two latter groups.

Functional-morphology hypothesis: sister to Sponges and Eumetazoa

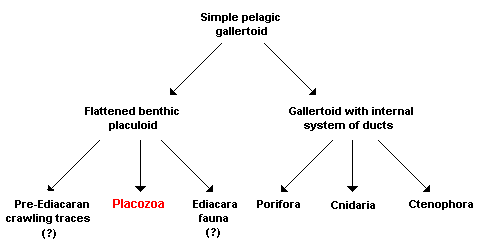

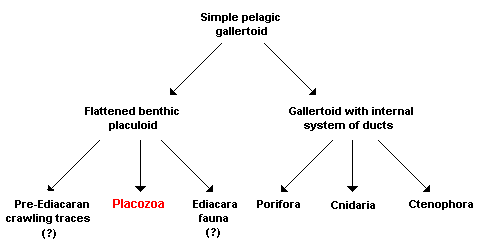

On the basis of their simple structure, the Placozoa were frequently viewed as a model organism for the transition from unicellular organisms to the multicellular animals (

On the basis of their simple structure, the Placozoa were frequently viewed as a model organism for the transition from unicellular organisms to the multicellular animals (Metazoa

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, have myocytes and are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and grow from a hol ...

) and are thus considered a sister taxon to all other metazoans:

According to a functional-morphology model, all or most animals are descended from a '' gallertoid'', a free-living (pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean and can be further divided into regions by depth. The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or water column between the sur ...

) sphere in seawater, consisting of a single ciliated

The cilium (: cilia; ; in Medieval Latin and in anatomy, ''cilium'') is a short hair-like membrane protrusion from many types of eukaryotic cell. (Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea.) The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike pr ...

layer of cells supported by a thin, noncellular separating layer, the basal lamina

The basal lamina is a layer of extracellular matrix secreted by the epithelial cells, on which the epithelium sits. It is often incorrectly referred to as the basement membrane, though it does constitute a portion of the basement membrane. The b ...

. The interior of the sphere

A sphere (from Ancient Greek, Greek , ) is a surface (mathematics), surface analogous to the circle, a curve. In solid geometry, a sphere is the Locus (mathematics), set of points that are all at the same distance from a given point in three ...

is filled with contractile fibrous cells and a gelatinous extracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix (ICM), is a network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide structural and bio ...

. Both the modern Placozoa and all other animals then descended from this multicellular beginning stage via two different processes:

* Infolding of the epithelium

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial ( mesothelial) tissues line the outer surfaces of man ...

led to the formation of an internal system of ducts and thus to the development of a modified gallertoid from which the sponges (Porifera

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a Basal (phylogenetics) , basal clade and a sister taxon of the Eumetazoa , diploblasts. They are sessility (motility) , sessile ...

), Cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

and Ctenophora

Ctenophora (; : ctenophore ) is a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and they are ...

subsequently developed.

* Other gallertoids, according to this model, made the transition over time to a benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

mode of life; that is, their habitat has shifted from the open ocean to the floor (benthic zone). This results naturally in a selective advantage for flattening of the body, as of course can be seen in many benthic species.

While the probability of encountering food, potential sexual partners, or predators is the same in all directions for animals floating freely in the water, there is a clear difference on the seafloor between the functions useful on body sides facing toward and away from the

While the probability of encountering food, potential sexual partners, or predators is the same in all directions for animals floating freely in the water, there is a clear difference on the seafloor between the functions useful on body sides facing toward and away from the substrate

Substrate may refer to:

Physical layers

*Substrate (biology), the natural environment in which an organism lives, or the surface or medium on which an organism grows or is attached

** Substrate (aquatic environment), the earthy material that exi ...

, leading their sensory, defensive, and food-gathering cells to differentiate and orient according to the vertical – the direction perpendicular to the substrate. In the proposed functional-morphology model, the Placozoa, and possibly several similar organisms only known from the fossils, are descended from such a life form, which is now termed ''placuloid''.

Three different life strategies have accordingly led to three different possible lines of development:

# Animals that live interstitially in the sand of the ocean floor were responsible for the fossil crawling traces that are considered the earliest evidence of animals; and are detectable even prior to the dawn of the Ediacaran Period

The Ediacaran ( ) is a geological period of the Neoproterozoic Era that spans 96 million years from the end of the Cryogenian Period at 635 Mya to the beginning of the Cambrian Period at 538.8 Mya. It is the last period of the Proterozoic Eo ...

in geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

. These are usually attributed to bilaterally symmetrical

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, the face of a human being has a plane of symme ...

worms, but the hypothesis presented here views animals derived from placuloids, and thus close relatives of ''Trichoplax adhaerens'', to be the producers of the traces.

# Animals that incorporated algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

as photosynthetically active endosymbionts

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), which live in the root ...

, i.e. primarily obtaining their nutrients from their partners in symbiosis

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction, between two organisms of different species. The two organisms, termed symbionts, can fo ...

, were accordingly responsible for the mysterious creatures of the Ediacara fauna that are not assigned to any modern animal taxon and lived during the Ediacaran Period, before the start of the Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

. However, recent work has shown that some of the Ediacaran assemblages (e.g. Mistaken Point

Mistaken Point Ecological Reserve is a wilderness area and a UNESCO World Heritage Site located at the southeastern tip of Newfoundland's Avalon Peninsula in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. The reserve is home to the namesake ...

) were in deep water, below the photic zone

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological ...

, and hence those individuals could not dependent on endosymbiotic photosynthesisers.

# Animals that grazed on algal mats would ultimately have been the direct ancestors of the Placozoa. The advantages of an amoeboid multiplicity of shapes thus allowed a previously present basal lamina and a gelatinous extracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix (ICM), is a network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide structural and bio ...

to be lost ''secondarily''. Pronounced differentiation between the surface facing the substrate (ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

) and the surface facing away from it (dorsal

Dorsal (from Latin ''dorsum'' ‘back’) may refer to:

* Dorsal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location referring to the back or upper side of an organism or parts of an organism

* Dorsal, positioned on top of an aircraft's fuselage

The fus ...

) accordingly led to the physiologically distinct cell layers of ''Trichoplax adhaerens'' that can still be seen today. Consequently, these are ''analogous'', but not ''homologous'', to ectoderm

The ectoderm is one of the three primary germ layers formed in early embryonic development. It is the outermost layer, and is superficial to the mesoderm (the middle layer) and endoderm (the innermost layer). It emerges and originates from the o ...

and endoderm

Endoderm is the innermost of the three primary germ layers in the very early embryo. The other two layers are the ectoderm (outside layer) and mesoderm (middle layer). Cells migrating inward along the archenteron form the inner layer of the gastr ...

– the "external" and "internal" cell layers in eumetazoans – i.e. the structures corresponding functionally to one another have, according to the proposed hypothesis, no common evolutionary origin.

Should any of the analyses presented above turn out to be correct, ''Trichoplax adhaerens'' would be the oldest branch of the multicellular animals, and a relic of the Ediacaran fauna, or even the pre-Ediacara fauna. Although very successful in their ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of Resource (biology), resources an ...

, due to the absence of extracellular matrix and basal lamina

The basal lamina is a layer of extracellular matrix secreted by the epithelial cells, on which the epithelium sits. It is often incorrectly referred to as the basement membrane, though it does constitute a portion of the basement membrane. The b ...

, the development potential of these animals was of course limited, which would explain the low rate of evolution of their phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

(their outward form as adults) – referred to as ''bradytely''.

This hypothesis was supported by a recent analysis of the ''Trichoplax adhaerens'' mitochondrial

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used ...

genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

in comparison to those of other animals. The hypothesis was, however, rejected in a statistical analysis of the ''Trichoplax adhaerens'' whole genome sequence in comparison to the whole genome sequences of six other animals and two related non-animal species, but only at which indicates a marginal level of statistical significance.

Epitheliozoa hypothesis: sister to Eumetazoa

A concept based on purely morphological characteristics pictures the Placozoa as the nearest relative of the animals with true tissues (Eumetazoa

Eumetazoa (), also known as Epitheliozoa or Histozoa, is a proposed basal animal subkingdom as a sister group of Porifera (sponges). The basal eumetazoan clades are the Ctenophora and the ParaHoxozoa. Placozoa is now also seen as a eumetazoan ...

). The taxon they share, called the Epitheliozoa, is itself construed to be a sister group to the sponges (Porifera

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a Basal (phylogenetics) , basal clade and a sister taxon of the Eumetazoa , diploblasts. They are sessility (motility) , sessile ...

):

The above view could be correct, although there is some evidence that the ctenophore

Ctenophora (; : ctenophore ) is a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and they ar ...

s, traditionally seen as Eumetazoa

Eumetazoa (), also known as Epitheliozoa or Histozoa, is a proposed basal animal subkingdom as a sister group of Porifera (sponges). The basal eumetazoan clades are the Ctenophora and the ParaHoxozoa. Placozoa is now also seen as a eumetazoan ...

, may be the sister to all other animals.

This is now a disputed classification. Placozoans are estimated to have emerged 750–800 million years ago, and the first modern neuron to have originated in the common ancestor of cnidarians and bilaterians about 650 million years ago (many of the genes expressed in modern neurons are absent in ctenophores, although some of these missing genes are present in placozoans).

The principal support for such a relationship comes from special cell to cell junctions – belt desmosomes

A desmosome (; "binding body"), also known as a macula adherens (plural: maculae adherentes) (Latin for ''adhering spot''), is a cell structure specialized for cell-to-cell adhesion. A type of junctional complex, they are localized spot-like ad ...

– that occur not just in the Placozoa but in all animals ''except'' the sponges: They enable the cells to join in an unbroken layer like the epitheloid of the Placozoa. ''Trichoplax adhaerens

''Trichoplax adhaerens'' is one of the four named species in the phylum Placozoa. The others are ''Hoilungia hongkongensis'', ''Polyplacotoma mediterranea'' and ''Cladtertia collaboinventa''. Placozoa is a basal group of multicellular animals, p ...

'' also shares the ventral gland cells with most eumetazoans. Both characteristics can be considered evolutionarily derived features (apomorphies

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to hav ...

), and thus form the basis of a common taxon for all animals that possess them.

One possible scenario inspired by the proposed hypothesis starts with the idea that the monociliated cells of the epitheloid in ''Trichoplax adhaerens

''Trichoplax adhaerens'' is one of the four named species in the phylum Placozoa. The others are ''Hoilungia hongkongensis'', ''Polyplacotoma mediterranea'' and ''Cladtertia collaboinventa''. Placozoa is a basal group of multicellular animals, p ...

'' evolved by reduction of the collars in the collar cells (choanocytes

Choanocytes (also known as "collar cells") are cells that line the interior of asconoid, syconoid and leuconoid body types of sponges that contain a central flagellum, or ''cilium,'' surrounded by a collar of microvilli which are connected by ...

) of sponges as the hypothesized ancestors of the Placozoa abandoned a filtering mode of life. The epitheloid would then have served as the precursor to the true epithelial tissue of the eumetazoans.

In contrast to the model based on functional morphology described earlier, in the Epitheliozoa hypothesis, the ventral and dorsal cell layers of the Placozoa are homologs of endoderm and ectoderm — the two basic embryonic cell layers of the eumetazoans. The digestive ''gastrodermis

Gastrodermis (from Ancient Greek: , , "stomach"; , , "skin") is the inner layer of Cell (biology), cells that serves as a lining membrane of the gastrovascular cavity in cnidarians. It is distinct from the outer epidermis and the inner dermis and ...

'' in the Cnidaria or the gut epithelium in the bilaterally symmetrical animals (Bilateria

Bilateria () is a large clade of animals characterised by bilateral symmetry during embryonic development. This means their body plans are laid around a longitudinal axis with a front (or "head") and a rear (or "tail") end, as well as a left� ...

) may have developed from endoderm, whereas ectoderm is the precursor to the external skin layer (epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermal layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

), among other things. The interior space pervaded by a fiber syncytium in the Placozoa would then correspond to connective tissue in the other animals. It is unclear whether the calcium ions stored in the syncytium would be related to the lime skeletons of many cnidarians.

As noted above, this hypothesis was supported in a statistical analysis of the ''Trichoplax adhaerens'' whole genome sequence, as compared to the whole-genome sequences of six other animals and two related non-animal species.

Eumetazoa/ParaHoxozoa hypotheses

A third hypothesis, based primarily on molecular genetics, views the Placozoa as highly simplified eumetazoans. According to this, ''Trichoplax adhaerens'' is descended from considerably more complex animals that already had muscles and nerve tissues. Both tissue types, as well as the basal lamina of theepithelium

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial ( mesothelial) tissues line the outer surfaces of man ...

, were accordingly lost more recently by radical secondary simplification.

Various studies in this regard so far yield differing results for identifying the exact sister group: In one case, the Placozoa would qualify as the nearest relatives of the Cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

, while in another they would be a sister group to the Ctenophora

Ctenophora (; : ctenophore ) is a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and they are ...

, and occasionally they are placed directly next to the Bilateria

Bilateria () is a large clade of animals characterised by bilateral symmetry during embryonic development. This means their body plans are laid around a longitudinal axis with a front (or "head") and a rear (or "tail") end, as well as a left� ...

.

Sister to Planulozoa

In 2018, they are typically placed according to the cladogram below: In this cladogram the Epitheliozoa and Eumetazoa are synonyms to each other and to theDiploblast

Diploblasty is a condition of the blastula in which there are two primary germ layers: the ectoderm and endoderm.

Diploblastic organisms are organisms which develop from such a blastula, and include Cnidaria and Ctenophora, formerly grouped t ...

s, and the Ctenophora

Ctenophora (; : ctenophore ) is a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and they are ...

are basal to them.

An argument raised against the proposed scenario is that it leaves morphological features of the animals completely out of consideration. The extreme degree of simplification that would have to be postulated for the Placozoa in this model, moreover, is only known for parasitic organisms, but would be difficult to explain functionally in a free-living species like ''Trichoplax adhaerens''.

This version is supported by statistical analysis of the ''Trichoplax adhaerens'' whole genome sequence in comparison to the whole genome sequences of six other animals and two related non-animal species. However, Ctenophora was not included in the analyses, placing the placozoans outside of the sampled Eumetazoans.

This version is more strongly supported by a 2023 analysis using 209 marker genes, Bayesian inference, and a sophisticated substitution model (CAT + GTR + Г4). A few other variations (other gene-sets, recoding) produce the same result. Single-cell genomics performed in the study indicate that the Placozoa do have a primitive version of neurons called peptideric cells. These cells can receive information through GPCRs and release information through vesicles and neuropeptides. They express the pre-synaptic program. Features present in Planulozoan neurons but absent in Placozoan peptideric cells are the post-synaptic program, cell projections, and ion channels; these are believed to have evolved in the Planulozoa ancestor. The Bilaterian neuron build on top of these features by the evolution of specialized synapses, neuronal cytoskeleton, and neuronal cell adhesion.

Sister to Cnidaria

DNA comparisons suggest that placozoans are related toCnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

, derived from planula

A planula is the free-swimming, flattened, ciliated, bilaterally symmetric larval form of various cnidarian species and also in some species of Ctenophores, which are not related to cnidarians at all. Some groups of Nemerteans also produce larva ...

larva (as seen in some Cnidaria). The Bilateria

Bilateria () is a large clade of animals characterised by bilateral symmetry during embryonic development. This means their body plans are laid around a longitudinal axis with a front (or "head") and a rear (or "tail") end, as well as a left� ...

also are thought to be derived from planuloids. The Cnidaria and Placozoa body axis are overtly similar, and placozoan and cnidarian cells are responsive to the same neuropeptide

Neuropeptides are chemical messengers made up of small chains of amino acids that are synthesized and released by neurons. Neuropeptides typically bind to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to modulate neural activity and other tissues like the ...

antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

despite extant placozoans not developing any neurons.

Internal phylogeny

The internal relationships among placozoa has been studied usingribosomal DNA

The ribosomal DNA (rDNA) consists of a group of ribosomal RNA encoding genes and related regulatory elements, and is widespread in similar configuration in all domains of life. The ribosomal DNA encodes the non-coding ribosomal RNA, integral struc ...

, mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

, and phylogenomics

Phylogenomics is the intersection of the fields of evolution and genomics. The term has been used in multiple ways to refer to analysis that involves genome data and evolutionary reconstructions. It is a group of techniques within the larger fields ...

(gene content comparison). The latter methods require the sequencing of more DNA but produce more reliable results.

References

External links

The ''Trichoplax adhaerens'' Grell-BS-1999 v1.0 Genome Portal at the DOE Joint Genome Institute

The ''Trichoplax'' Genome Project at the Yale Peabody Museum

Research articles from the ITZ, TiHo Hannover

* –

Mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

and 16S rRNA

16S ribosomal RNA (or 16Svedberg, S rRNA) is the RNA component of the 30S subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome (SSU rRNA). It binds to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and provides most of the SSU structure.

The genes coding for it are referred to as ...

analysis and phylogeny of ''Trichoplax adhaerens''

Historical overview of ''Trichoplax'' research

* [https://archive.today/20130415130142/http://icb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/icm015v1 Vicki Buchsbaum Pearse, and Oliver Voigt, 2007. "Field biology of placozoans (Trichoplax): distribution, diversity, biotic interactions. Integrative and Comparative Biology"], . {{Taxonbar, from=Q131040 Placozoa, ParaHoxozoa Animal phyla Parazoa Ediacaran first appearances