Philip Of Swabia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

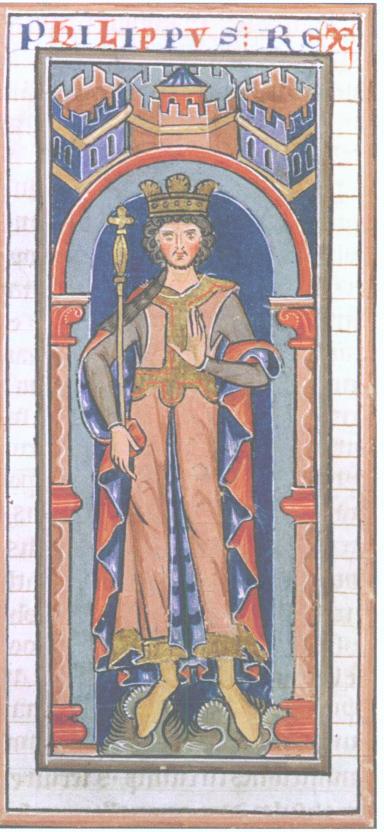

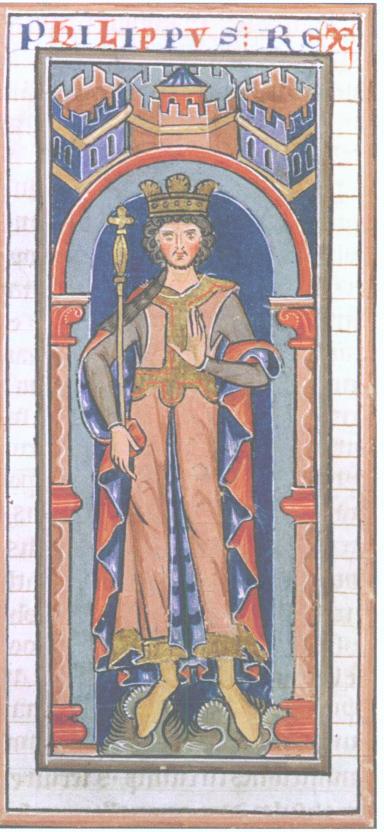

Philip of Swabia (February/March 1177 – 21 June 1208), styled Philip II in his charters, was a member of the

As a child, Philip was initially prepared for an ecclesiastical career. He learned to read and also learned Latin, and was placed at the Premonstratensian Monastery in Adelberg for his further education. From April 1189 to July 1193 Philip was provost at the

As a child, Philip was initially prepared for an ecclesiastical career. He learned to read and also learned Latin, and was placed at the Premonstratensian Monastery in Adelberg for his further education. From April 1189 to July 1193 Philip was provost at the

From then on, both kings tried to win over the undecided or opponents. In order to achieve this goal, there were fewer major decisive battles, but personal bonds between rulers and greats had to be strengthened. This happened because faithful, relatives and friends were favored by gifts or the transfer of imperial property, or by a marriage policy that was supposed to strengthen partisanship or promote a change of party. In an aristocratic society both rivals for the German throne this had regard for the rank and reputation of the great, on their honor take.

In the next few years of the controversy for the throne, the acts of representation of power were of immense importance, because in them not only the kingship was on display, but the role of the great in the respective system of rule was revealed. Philip did little to symbolically represent his kingship. In 1199, Philip and Irene-Maria celebrated

From then on, both kings tried to win over the undecided or opponents. In order to achieve this goal, there were fewer major decisive battles, but personal bonds between rulers and greats had to be strengthened. This happened because faithful, relatives and friends were favored by gifts or the transfer of imperial property, or by a marriage policy that was supposed to strengthen partisanship or promote a change of party. In an aristocratic society both rivals for the German throne this had regard for the rank and reputation of the great, on their honor take.

In the next few years of the controversy for the throne, the acts of representation of power were of immense importance, because in them not only the kingship was on display, but the role of the great in the respective system of rule was revealed. Philip did little to symbolically represent his kingship. In 1199, Philip and Irene-Maria celebrated  In contrast to his father Frederick Barbarossa, marriage projects with foreign royal families were out of the question for Philip; his marriage policy was exclusively related to the dispute for the German throne. In 1203 he tried to find a balance with the

In contrast to his father Frederick Barbarossa, marriage projects with foreign royal families were out of the question for Philip; his marriage policy was exclusively related to the dispute for the German throne. In 1203 he tried to find a balance with the

Since the end of May 1208, Philip had been preparing for a campaign against Otto IV and his allies. He interrupted the planning to attend the wedding of his niece Countess Beatrice II of Burgundy with Duke Otto of Merania on 21 June in

Since the end of May 1208, Philip had been preparing for a campaign against Otto IV and his allies. He interrupted the planning to attend the wedding of his niece Countess Beatrice II of Burgundy with Duke Otto of Merania on 21 June in

online

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Philip (of Swabia) – Encyclopædia Britannica

{{DEFAULTSORT:Philip of Swabia 1177 births 1208 deaths 12th-century Kings of the Romans 13th-century Kings of the Romans 13th-century murdered monarchs Dukes of Swabia Hohenstaufen family Burials at Speyer Cathedral 13th-century nobility from the Holy Roman Empire Sons of emperors Children of Frederick Barbarossa Sons of counts Sons of countesses regnant

House of Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynasty ...

and King of Germany

This is a list of monarchs who ruled over East Francia, and the Kingdom of Germany (), from Treaty of Verdun, the division of the Francia, Frankish Empire in 843 and Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire in ...

from 1198 until his assassination.

The death of Philip's older brother Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry VI (German language, German: ''Heinrich VI.''; November 1165 – 28 September 1197), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was King of Germany (King of the Romans) from 1169 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1191 until his death. From 1194 he was ...

, in 1197 meant that the Hohenstaufen rule (which reached as far as the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

) collapsed in imperial Italy and created a power vacuum to the north of the Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

. Reservations about the kingship of Henry's underage son, Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Given name

Nobility

= Anhalt-Harzgerode =

* Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

= Austria =

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria fro ...

, led to two royal elections in 1198, which resulted in the German throne dispute

The German throne dispute or German throne controversy () was a political conflict in the Holy Roman Empire from 1198 to 1215. This dispute, between the House of Hohenstaufen and the House of Welf, was over the successor to Emperor Henry VI, wh ...

: the two elected kings, Philip of Swabia and Otto of Brunswick, claimed the throne for themselves. Both opponents tried in the following years through European and papal support, with the help of money and gifts, through demonstrative public appearances and rituals, to decide the conflict for oneself by raising ranks or by military and diplomatic measures. Philip was able to increasingly assert his kingship against Otto in the north part of the Alps. However, at the height of his power, he was assassinated in 1208. This ended the dispute for the throne; his opponent Otto quickly found recognition. Philip was the first German king to be murdered during his reign. In posterity, Philip is one of the little-noticed Hohenstaufen rulers.

Life

Early years

Philip was born in or nearPavia

Pavia ( , ; ; ; ; ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy, in Northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino (river), Ticino near its confluence with the Po (river), Po. It has a population of c. 73,086.

The city was a major polit ...

in the Imperial Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

as the tenth child and eighth (but fifth and youngest surviving) son of Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (; ), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death in 1190. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen on 9 March 115 ...

, King of Germany

This is a list of monarchs who ruled over East Francia, and the Kingdom of Germany (), from Treaty of Verdun, the division of the Francia, Frankish Empire in 843 and Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire in ...

and Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

and his second wife Beatrice I, Countess of Burgundy

Beatrice I (1143 – 15 November 1184) was countess of Burgundy from 1148 until her death, and was also Holy Roman Empress by marriage to Frederick Barbarossa. She was crowned empress by Antipope Paschal III in Rome on 1 August 1167, an ...

. His paternal family was the noble House of Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynasty ...

, the name given to the dynasty by historians since the 15th century. The origins of the family are still unclear today; the ancestors on the paternal side were minor nobles and their names have not been preserved. All that is known about Barbarossa's great-grandfather Frederick of Büren

Frederick of Büren ( 1053) was a count in northern Duchy of Swabia, Swabia and an ancestor of the imperial Hohenstaufen, Staufer dynasty., nn. 8 & 9.

The name Frederick of Büren is known only from the ''Tabula Consanguinitatis'', a Staufer gene ...

is that he married a woman named Hildegard (whose own parentage was disputed: she was a member of either the Comital family of Egisheim–Dagsburg or the obscure Schlettstadt family). A few years ago it was assumed that the Schlettstadt property did not belong to Hildegard but to her husband himself and the Hohenstaufen were therefore not a Swabian but an Alsatian family. It wasn't until around 1100 that the family under Duke Frederick I of Swabia located into the East Swabian Rems valley.

Much more important for the Hohenstaufen family was the prestigious connection with the Salian dynasty

The Salian dynasty or Salic dynasty () was a dynasty in the High Middle Ages. The dynasty provided four kings of Germany (1024–1125), all of whom went on to be crowned Holy Roman emperors (1027–1125).

After the death of the last Ottonia ...

. Frederick Barbarossa's grandmother was Agnes, a daughter of Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry IV (; 11 November 1050 – 7 August 1106) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1084 to 1105, King of Germany from 1054 to 1105, King of Italy and List of kings of Burgundy, Burgundy from 1056 to 1105, and Duke of Bavaria from 1052 to 1054. He was t ...

. Philip's father saw himself as a direct descendant of the first Salian ruler Conrad II, to whom he referred several times as his ancestor in documents. After the extinction of the Salian dynasty in the male line in 1125 firstly Frederick II, Duke of Swabia (Barbarossa's father) and then his brother Conrad tried in vain to claim the royal dignity invoking his descent from the Salians. In 1138, Conrad III was finally elected King of Germany, being the first scion of the Swabian Hohenstaufen dynasty to be elected King of the Romans

King of the Romans (; ) was the title used by the king of East Francia following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002–1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German king between his election and coronatio ...

, against the fierce resistance of the rival House of Welf

The House of Welf (also Guelf or Guelph) is a European dynasty that has included many German and British monarchs from the 11th to 20th century and Emperor Ivan VI of Russia in the 18th century. The originally Franconian family from the Meuse-Mo ...

. In 1152 the royal dignity passed smoothly to Conrad III's nephew, Frederick Barbarossa, who was also Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 onwards. Barbarossa became embroiled in a conflict with Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland (), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a Papal election, ...

. It was not until 1177 that the long standing conflict of the Emperor with the Pope and the Italian cities of the Lombard League

The Lombard League (; ) was an alliance of cities formed in 1167, and supported by the popes, to counter the attempts by the Hohenstaufen Holy Roman emperors to establish direct royal administrative control over the cities of the Kingdom of It ...

could be resolved in the Treaty of Venice.

The Hohenstaufen had never used the name Philip before. The prince was named after the Archbishop Philip of Cologne, who was an important helper and confidante of Barbarossa at this time. The name of the Archbishop of Cologne was thus accepted into a royal family. For historian Gerd Althoff, this demonstrative honor makes "Barbarossa's preparations for the confrontation with Henry the Lion tangible". A little later, the Archbishop of Cologne played a key role in the overthrow of the powerful Duke of Bavaria and Saxony.

As a child, Philip was initially prepared for an ecclesiastical career. He learned to read and also learned Latin, and was placed at the Premonstratensian Monastery in Adelberg for his further education. From April 1189 to July 1193 Philip was provost at the

As a child, Philip was initially prepared for an ecclesiastical career. He learned to read and also learned Latin, and was placed at the Premonstratensian Monastery in Adelberg for his further education. From April 1189 to July 1193 Philip was provost at the collegiate church

In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons, a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, headed by a dignitary bearing ...

of Aachen Cathedral

Aachen Cathedral () is a Catholic Church, Catholic church in Aachen, Germany and the cathedral of the Diocese of Aachen.

One of the oldest cathedral buildings in Europe, it was constructed as the royal chapel of the Palace of Aachen of Holy Rom ...

, while his father left Germany for the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt led by King Philip II of France, King Richard I of England and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by the Ayyubid sultan Saladin in 1187. F ...

in 1189, but he drowned in the Göksu

The Göksu River (), known in antiquity as the Calycadnus and in the Middle Ages as the Saleph, is a river on the Taşeli Plateau in southern Turkey. Its two sources arise in the Taurus Mountains—the northern in the Geyik Mountains and the s ...

(Saleph) River in Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

the next year. In 1190 or 1191 Philip was elected Prince-bishop

A prince-bishop is a bishop who is also the civil ruler of some secular principality and sovereignty, as opposed to '' Prince of the Church'' itself, a title associated with cardinals. Since 1951, the sole extant prince-bishop has been the ...

of Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is, after Nuremberg and Fürth, the Franconia#Towns and cities, third-largest city in Franconia located in the north of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Lower Franconia. It sp ...

, though without being consecrated, probably due to intervention of his brother Henry VI. In 1186 Henry VI married with Constance, the aunt of the reigning King William II of Sicily

William II (December 115311 November 1189), called the Good, was king of Sicily from 1166 to 1189. From surviving sources William's character is indistinct. Lacking in military enterprise, secluded and pleasure-loving, he seldom emerged from hi ...

; this gave the Hohenstaufen the possibility of a union of the Kingdom of Sicily with the Holy Roman Empire (''unio regni ad imperium''). As a result, however, the relationship with the Pope deteriorated, because the Holy See wanted to maintain the feudal claim over the Kingdom of Sicily. In the spring of 1193 Philip forsook his ecclesiastical calling, perhaps because of the childlessness of the imperial couple; also, Philip's three other brothers were also without male heirs: Duke Frederick VI of Swabia had already died in 1191 and Conrad of Rothenburg, who succeeded him as Duke of Swabia, was unmarried. In addition, Otto I, Count Palatine of Burgundy, although already married, had no male descendants yet. However, the concerns of the imperial couple turned out to be unfounded. Empress Constance gave birth to a son on 26 December 1194 in Jesi

Jesi () is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the province of Ancona, in the Italian region of Marche.

It is an important industrial and artistic center in the floodplain on the left (north) bank of the Esino river, before its mouth on the Adria ...

, the later Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor

Frederick II (, , , ; 26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 and King of Jerusalem from 1225. He was the son of Emperor Henry VI, Holy Roman ...

. While the Emperor was absent, the princes elected his two-year-old son Frederick as King of the Romans in Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

at the end of 1196; with this move, Henry VI wanted to see his succession secured before he prepared for the Crusade of 1197.

To improve relationships with the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

, in April 1195 Henry VI betrothed Philip to Irene Angelina, a daughter of Emperor Isaac II and the widow of junior King Roger III of Sicily, a lady who was described by Walther von der Vogelweide

Walther von der Vogelweide (; ) was a Minnesänger who composed and performed love-songs and political songs ('' Sprüche'') in Middle High German. Walther has been described as the greatest German lyrical poet before Goethe; his hundred or s ...

as "the rose without a thorn, the dove without guile": she was among those taken prisoner by Henry VI when he invaded Sicily in 1194. In early 1195, Philip accompanied his imperial brother on his journey to Sicily and at Easter

Easter, also called Pascha ( Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in t ...

1195 he was made Margrave of Tuscany

The March of Tuscany (; Modern ) was a march of the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages. Located in northwestern central Italy, it bordered the Papal States to the south, the Ligurian Sea to the west and Lombardy to ...

, receiving the disputed Matildine lands; in his retinue in Italy was the Minnesinger

(; "love song") was a tradition of German lyric- and song-writing that flourished in the Middle High German period (12th to 14th centuries). The name derives from '' minne'', the Middle High German word for love, as that was ''Minnesangs m ...

Bernger von Horheim

Bernger von Horheim was a Rhenish Minnesänger of the late twelfth century. He wrote in the tradition of courtly love and was influenced by Friedrich von Hausen.

Bernger may originate from Horrheim in Vaihingen an der Enz. Another possibili ...

. Philip's rule in Tuscany there earned him the enmity of Pope Celestine III

Pope Celestine III (; c. 1105 – 8 January 1198), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 March or 10 April 1191 to his death in 1198. He had a tense relationship with several monarchs, including Emperor ...

, who excommunicated him. On 3 May 1196, Philip was documented for the last time as Margrave of Tuscany. After the murder of his brother Conrad in August 1196, Philip succeeded him as Duke of Swabia

The Dukes of Swabia were the rulers of the Duchy of Swabia during the Middle Ages. Swabia was one of the five stem duchy, stem duchies of the medieval German kingdom, and its dukes were thus among the most powerful magnates of Germany. The most no ...

. The marriage of Philip and Irene Angelina (renamed Maria upon her wedding) probably took place at Pentecost

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christianity, Christian holiday which takes place on the 49th day (50th day when inclusive counting is used) after Easter Day, Easter. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spiri ...

(25 May) 1197 in the Gunzenle hill near Augsburg

Augsburg ( , ; ; ) is a city in the Bavaria, Bavarian part of Swabia, Germany, around west of the Bavarian capital Munich. It is a College town, university town and the regional seat of the Swabia (administrative region), Swabia with a well ...

. Five daughters were certainly born from the union:

* Beatrix

Beatrix is a Latin feminine given name, most likely derived from ''Viatrix'', a feminine form of the Late Latin name ''Viator'' which meant "voyager, traveller" and later influenced in spelling by association with the Latin word ''beatus'' or "ble ...

(April/June 1198 – 11 August 1212), who married her father's rival, Emperor Otto IV on 22 July 1212 and died three weeks later without issue.

* Maria (1199/1200 – 29 March 1235), who married the future Duke Henry II of Brabant before 22 August 1215 and had issue.

* Kunigunde (February/March 1202 – 13 September 1248), who married King Wenceslaus I of Bohemia

Wenceslaus I (; c. 1205 – 23 September 1253), called One-Eyed, was King of Bohemia from 1230 to 1253.

Wenceslaus was a son of Ottokar I of Bohemia and his second wife Constance of Hungary.

Marriage and children

In 1224, Wenceslaus married ...

in 1224 and had issue.

* Elisabeth (March/May 1205 – 5 November 1235), who married King Ferdinand III of Castile

Ferdinand III (; 1199/120130 May 1252), called the Saint (''el Santo''), was King of Castile from 1217 and King of León from 1230 as well as King of Galicia from 1231. He was the son of Alfonso IX of León and Berengaria of Castile. Through his ...

on 30 November 1219 and had issue.

* Daughter (posthumously born and died 20/27 August 1208). She and her mother died following childbirth complications.

Sources identified two short-lived sons, Reinald and Frederick, also born from the union of Philip and Irene-Maria Angelina, being both buried at Lorch Abbey alongside their mother. However, there were no contemporary sources who could ascertain their existence without doubt.

Struggle for the throne

Outbreak of the conflict

Philip enjoyed his brother Henry VI's confidence to a very great extent, and appears to have been designated as guardian for the king's minor son, in the event of his early death. In September 1197 Philip had set out to fetch Frederick fromApulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

for his coronation as King of the Romans in Aachen

Aachen is the List of cities in North Rhine-Westphalia by population, 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, 27th-largest city of Germany, with around 261,000 inhabitants.

Aachen is locat ...

. While staying in Montefiascone

Montefiascone is a town and ''comune'' of the province of Viterbo, in Lazio, central Italy. It stands on a hill on the southeast side of Lake Bolsena, about north of Rome.

History

The name of the city derives from that of the Falisci (''Mons Fa ...

, he heard of Henry VI's sudden death in Messina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

on 28 September 1197 and returned at once to Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. He appears to have desired to protect the interests of his nephew and to quell the disorder which arose on Henry VI's death: On 21 January 1198, Philip issued a charter for the citizens of Speyer

Speyer (, older spelling ; ; ), historically known in English as Spires, is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate in the western part of the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located on the left bank of the r ...

, in which he indicated that he was acting in the name of King Frederick; however, he was overtaken by events.

Meanwhile, a number of Princes of the Holy Roman Empire

Prince of the Holy Roman Empire (, , cf. ''Fürst'') was a title attributed to a hereditary ruler, nobleman or prelate recognised by the Holy Roman Emperor.

Definition

Originally, possessors of the princely title bore it as immediate vassal ...

hostile to the ruling Hohenstaufen dynasty under the leadership of Prince-Archbishop Adolph of Cologne took the occasion to elect a German anti-king

An anti-king, anti king or antiking (; ) is a would-be king who, due to succession disputes or simple political opposition, declares himself king in opposition to a reigning monarch. OED "Anti-, 2" The OED does not give "anti-king" its own entry ...

in the person of the Welf Otto of Brunswick, the second surviving son of the former Saxon

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

duke Henry the Lion and a nephew of King Richard I of England

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199), known as Richard the Lionheart or Richard Cœur de Lion () because of his reputation as a great military leader and warrior, was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ru ...

. He was by no means Adolph's preferred candidate, because the Archdiocese of Cologne had benefited considerably from the fall of the powerful Duke Henry the Lion. Rather, a group of financially strong citizens ran Otto's election. In exchange for his support, the Archbishop was able to reduce the high debt burden of his diocese. The hostility to the kingship of a child was growing, so Philip was chosen by Ghibellines as defender of the empire during Frederick's minority, and Otto I of Burgundy, the only living elder brother of Philip who was passed over for being considered inefficient and busy solving problems in his own fief, also supported him. He finally consented to his own election at Nordhausen. On 6 March 1198, in front of the ecclesiastical and secular greats present in Ichtershausen, he declared his willingness to be elected king. Two days later (8 March) Philip was elected German King at Mühlhausen

Mühlhausen () is a town in the north-west of Thuringia, Germany, north of Niederdorla, the country's Central Germany (geography)#Geographical centre, geographical centre, north-west of Erfurt, east of Kassel and south-east of Göttingen ...

in Thuringia

Thuringia (; officially the Free State of Thuringia, ) is one of Germany, Germany's 16 States of Germany, states. With 2.1 million people, it is 12th-largest by population, and with 16,171 square kilometers, it is 11th-largest in area.

Er ...

. The election took place on Laetare Sunday, a day that was of considerable symbolic importance in the Hohenstaufen royal tradition. Otherwise there were a number of symbolic deficits: Although backed in the election by Duke Leopold VI of Austria

Leopold may refer to:

People

* Leopold (given name), including a list of people named Leopold or Léopold

* Leopold (surname)

Fictional characters

* Leopold (The Simpsons), Leopold (''The Simpsons''), Superintendent Chalmers' assistant on ''The ...

, Duke Ottokar I of Bohemia

Ottokar I (; 1155 – 1230) was Duke of Bohemia periodically beginning in 1192, then acquired the title of King of Bohemia, first in 1198 from Philip of Swabia, later in 1203 from Otto IV of Brunswick and in 1212 (as hereditary) from ...

, Duke Berthold V of Zähringen, and Landgrave Hermann I of Thuringia, all the three Rhenish Archbishops (Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

, Mainz

Mainz (; #Names and etymology, see below) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, and with around 223,000 inhabitants, it is List of cities in Germany by population, Germany's 35th-largest city. It lies in ...

and Trier

Trier ( , ; ), formerly and traditionally known in English as Trèves ( , ) and Triers (see also Names of Trier in different languages, names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle (river), Moselle in Germany. It lies in a v ...

), who traditionally performed an important ceremonial act of institution, were absent from Philip's election, and Mühlhausen was an unusual location for a king's election. For Mühlhausen, in the Hohenstaufen period up to Philip's election as king, only one single residence as a ruler can be proven. With this choice of location, Philip may have wanted to symbolically erase the humiliation that his great-uncle Conrad III suffered in autumn 1135 in Mühlhausen during his submission to Lothair III. Instead, the Imperial Regalia

The Imperial Regalia, also called Imperial Insignia (in German ''Reichskleinodien'', ''Reichsinsignien'' or ''Reichsschatz''), are regalia of the Holy Roman Emperor. The most important parts are the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire, C ...

(crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, parti ...

, sword

A sword is an edged and bladed weapons, edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter ...

and orb) were in Philip's possession. His rival Otto was only elected on 9 June 1198 in Cologne by Archbishop Adolph (who had bought the votes of the absent archbishops). Only the Bishop of Paderborn

The Metropolitan Archdiocese of Paderborn () is a Latin Church archdiocese of the Catholic Church in Germany; its seat is Paderborn.

, Bishop Thietmar of Minden, and three Prince-Provosts took part in the election of the Welf. After his election, Philip failed to make up for the coronation quickly. Rather, he moved to Worms

The World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) is a taxonomic database that aims to provide an authoritative and comprehensive catalogue and list of names of marine organisms.

Content

The content of the registry is edited and maintained by scien ...

next to his confidant, Bishop Luitpold. The hesitant behavior of Philip gave Otto the opportunity to be crowned by the rightful coronator ("''Königskröner''") Adolph of Cologne on 12 July 1198 at the traditional royal place in Aachen

Aachen is the List of cities in North Rhine-Westphalia by population, 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, 27th-largest city of Germany, with around 261,000 inhabitants.

Aachen is locat ...

, which had to be captured before against the resistance of loyal Hohenstaufen liensmen.

In an empire without a written constitution, a solution had to be found under the conditions of a consensual system of rule where there were competing claims. These habits were agreed upon through consultation at court meetings, synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the Ancient Greek () ; the term is analogous with the Latin word . Originally, ...

s, or other gatherings. The consensus thus established was the most important process for establishing order in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. In the controversy for the German throne, one of the rivals was only able to prevail in the long term if the other side was offered noticeable compensation. With inferior opponent a balance had to be found of him to abandon the kingship while preserving his honor easier.

In the first few months after his election as king, Philip failed to issue documents and thereby assert his kingship. His first surviving royal document, issued to Bishop Bertram of Metz, dated from Worms on 27 June 1198. Two days later, Philip forged an alliance with King Philip II of France

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), also known as Philip Augustus (), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks (Latin: ''rex Francorum''), but from 1190 onward, Philip became the firs ...

. In Mainz Cathedral

Mainz Cathedral or St. Martin's Cathedral ( or, officially, ') is located near the historical center and pedestrianized market square of the city of Mainz, Germany. This 1000-year-old Roman Catholic cathedral is the site of the episcopal see of th ...

on 8 September 1198, it wasn't the Archbishop of Cologne, as usual, but Archbishop Aymon II of Tarentaise who crowned Philip as German King. It is uncertain whether his wife was also crowned alongside him. Despite these violations of the ''consuetudines'' (Customs) when he was elected and crowned as King, Philip was able to unite the majority of the princes behind him. For the princes, property, ancestry and origins were essential for their support of Philip. Nevertheless, he knew that he had to settle the conflict with Otto and his supporters. A first attempt to mediate by Archbishop Conrad of Mainz in 1199 was rejected by the Welf.

Both sides strived for the coronation as Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

by Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

and with it the recognition of their rule. The pontiff himself acted tactically before decided on one of the conflicting parties; this gave the opportunity to contact the Holy See several times through letters and embassies. Pope Innocent III wanted to prevent by all means the ''unio regni ad imperium'' (the reunification of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

and the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

, whose liege lord he was and wanted to remain) and he was also concerned about the Hohenstaufen claims to central Italy. For the pontiff, the question of obedience was a decisive factor in determining which candidate would have the papal recognition (''favor apostolicus''). In contrast to Otto, Philip expressed himself much more cautiously towards the Pope on this question.

In the first months of 1199, the Welf party asked for confirmation of the decision and for an invitation from the Pope for Otto IV to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor. On 28 May 1199, the supporters of the Hohenstaufen drew the Speyer Prince Declaration (''Speyerer Fürstenerklärung''), whereby they rejected any papal exertion of influence on the Imperial line of succession. At this point in time, Philip could have 4 archbishops, 23 imperial bishops, 4 imperial abbots and 18 secular imperial princes behind him; they confidently appealed to the princely majority and announced the march to Rome for the imperial coronation.

At the turn of the year 1200/01, the Pope subjected the candidates for the imperial coronation to a critical examination. In the Bull ''Deliberatio domni pape Innocentii super facto imperii de tribus electis'', the Pope set out the reasons for and against the suitability of the respective candidates: Philip's nephew Frederick II was put aside due to his youth, and Philip himself was in the eyes of the Pope as "the son of a race of persecutors" of the church (''genus persecutorum'') because his father Frederick Barbarossa had fought against the Papacy for years. In contrast, Otto's ancestors were always loyal followers of the church. Otto had also sworn extensive concessions to the Holy See in the Neuss oath on 8 June 1201, assuring him that he would not strive for a union of the Holy Roman Empire with the Kingdom of Sicily. Thus, the Pope chose the Welf and excommunicated Philip and his associates. The papal judgment for Otto had no major effect in the empire.

Consolidation of rule

From then on, both kings tried to win over the undecided or opponents. In order to achieve this goal, there were fewer major decisive battles, but personal bonds between rulers and greats had to be strengthened. This happened because faithful, relatives and friends were favored by gifts or the transfer of imperial property, or by a marriage policy that was supposed to strengthen partisanship or promote a change of party. In an aristocratic society both rivals for the German throne this had regard for the rank and reputation of the great, on their honor take.

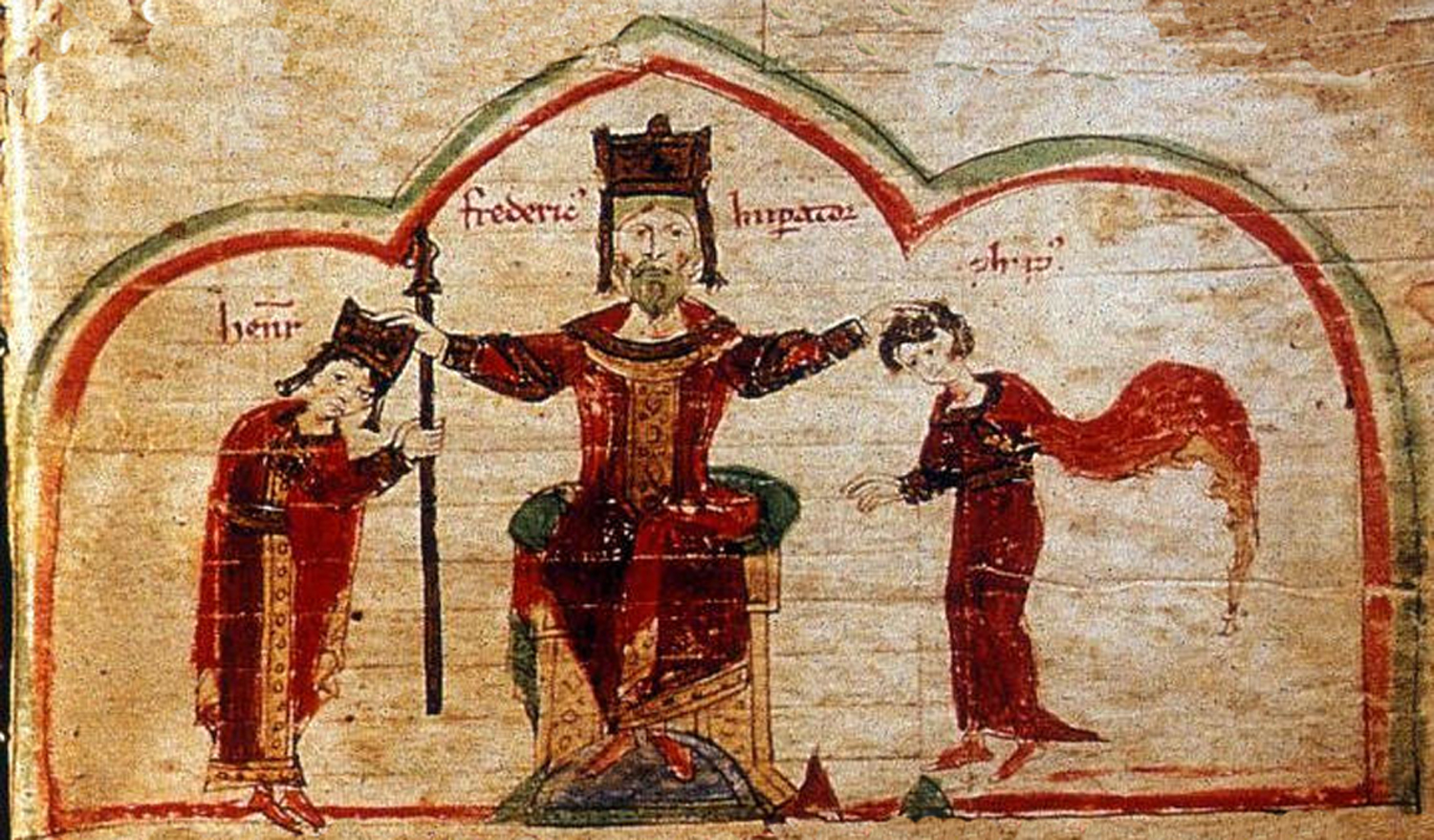

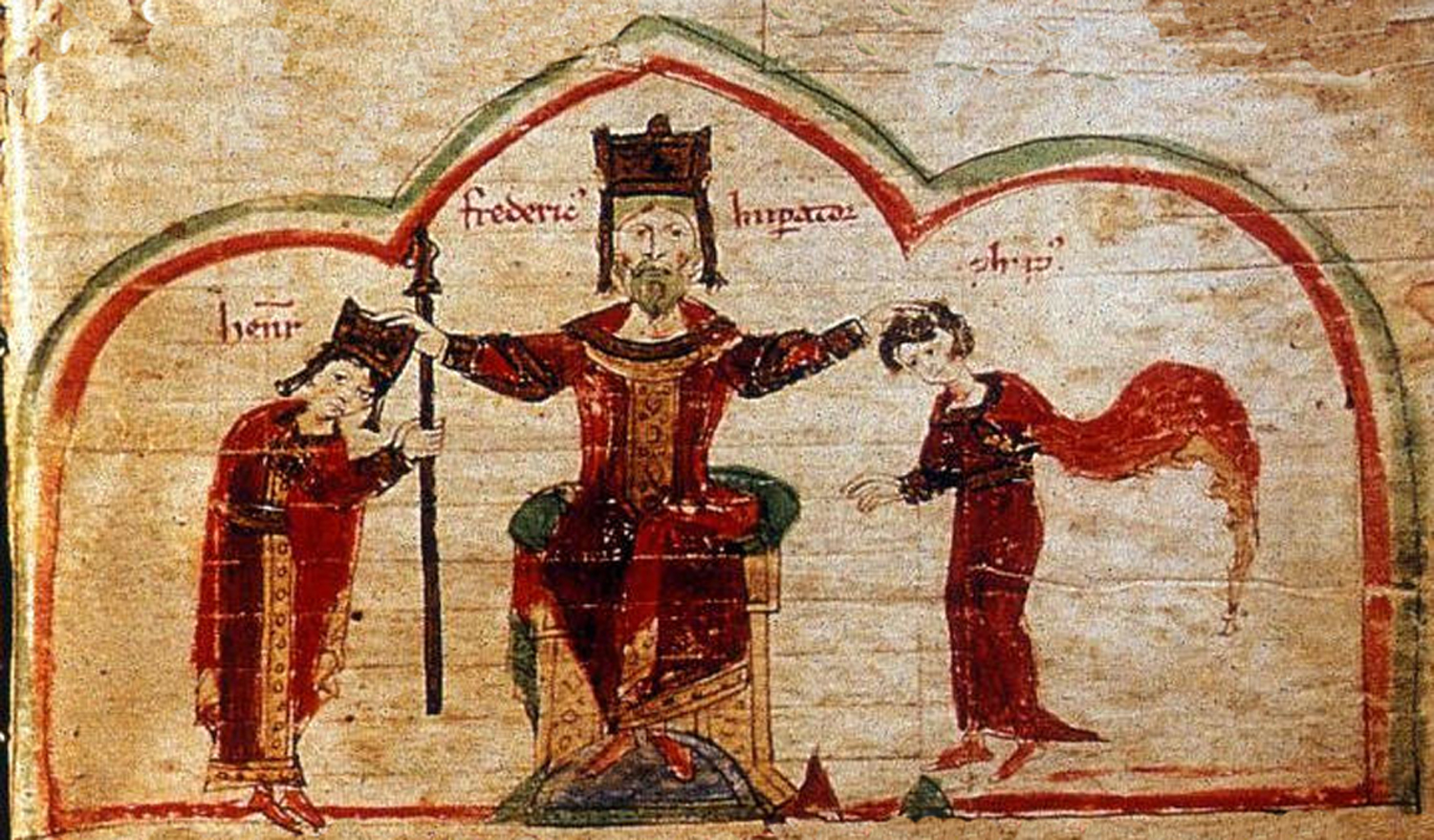

In the next few years of the controversy for the throne, the acts of representation of power were of immense importance, because in them not only the kingship was on display, but the role of the great in the respective system of rule was revealed. Philip did little to symbolically represent his kingship. In 1199, Philip and Irene-Maria celebrated

From then on, both kings tried to win over the undecided or opponents. In order to achieve this goal, there were fewer major decisive battles, but personal bonds between rulers and greats had to be strengthened. This happened because faithful, relatives and friends were favored by gifts or the transfer of imperial property, or by a marriage policy that was supposed to strengthen partisanship or promote a change of party. In an aristocratic society both rivals for the German throne this had regard for the rank and reputation of the great, on their honor take.

In the next few years of the controversy for the throne, the acts of representation of power were of immense importance, because in them not only the kingship was on display, but the role of the great in the respective system of rule was revealed. Philip did little to symbolically represent his kingship. In 1199, Philip and Irene-Maria celebrated Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a Religion, religious and Culture, cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by coun ...

with tremendous splendor (''cum ingenti magnificentia'') in Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; ) is the Capital city, capital of the Germany, German States of Germany, state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is on the Elbe river.

Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archbishopric of Mag ...

—close to Otto's residence in Brunswick—in the presence of the Ascanian Duke Bernard of Saxony and numerous Saxon and Thuringian nobles. Contemporary sources had criticized the large expenditures on farm days as a waste, assuming a consistent modernization and more effective rulership; more recent studies, however, see the expenses of the court festival less as useless expenditure, but as a result of the goal of acquiring fame and honor. The Magdeburg Court Day at Christmas is considered to be the first high point in the fight for royal dignity. Some of the princes present expressed their first public support for the Hohenstaufen by participating. The chronicler of the ''Gesta'' of the Bishops of Halberstadt and the poet ( ''Minnesänger'') Walther von der Vogelweide

Walther von der Vogelweide (; ) was a Minnesänger who composed and performed love-songs and political songs ('' Sprüche'') in Middle High German. Walther has been described as the greatest German lyrical poet before Goethe; his hundred or s ...

were present. Walther's description of the great splendor of Magdeburg Court festivities in a series of poems and songs called "The Saying for Christmas in Magdeburg" (''Spruch zur Magdeburger Weihnacht'') in order to spread the reputation of Philip as a capable ruler. Philip's ability to rule as a king should be demonstrated by the rich clothing and the stately appearance of the participants in the festival. On Christmas Day the king went in a solemn procession with his splendidly dressed wife to the service under the crown. The Saxon Duke Bernard carried the king's sword in front of him and showed his support for the Hohenstaufen. The sword bearer service was not only an honorable distinction, as research has long assumed, but according to historian Gerd Althoff was also a sign of demonstrative subordination. In such event, personal ties were emphasized, because Bernard himself had intended in 1197 to fight for royal dignity. In addition, Bernard saw himself best protected against the possible expropriation of his Duchy of Saxony by the Welf through his support of the Hohenstaufen. The elevation

The elevation of a geographic location (geography), ''location'' is its height above or below a fixed reference point, most commonly a reference geoid, a mathematical model of the Earth's sea level as an equipotential gravitational equipotenti ...

of the bones of the Empress Cunigunde of Luxembourg, who was canonized by the Pope in 1200, was solemnly celebrated in Magdeburg Cathedral

Magdeburg Cathedral (), officially called the Cathedral of Saints Maurice and Catherine (), is a Protestant Church in Germany, Lutheran cathedral in Germany and the oldest Gothic architecture, Gothic cathedral in the country. It is the proto-cat ...

on 9 September 1201 in Philip's presence.

Also in 1201, Philip was visited by his cousin Boniface of Montferrat, the leader of the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

. Although Boniface's exact reasons for meeting with Philip are unknown, while at Philip's court he also met Alexius Angelus, Philip's brother-in-law. Some historians have suggested that it was here that Alexius convinced Boniface, and later the Venetians, to divert the Crusade to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

and restore Isaac II to the throne, as he had recently been deposed by his brother Alexius III, Alexius and Irene-Maria's uncle.

In contrast to his father Frederick Barbarossa, marriage projects with foreign royal families were out of the question for Philip; his marriage policy was exclusively related to the dispute for the German throne. In 1203 he tried to find a balance with the

In contrast to his father Frederick Barbarossa, marriage projects with foreign royal families were out of the question for Philip; his marriage policy was exclusively related to the dispute for the German throne. In 1203 he tried to find a balance with the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

through a marriage project, in which Philip wanted to arrange the betrothal of one of his daughters with a nephew of Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

. However, Philip did not agree with important points required by the Pope, such as carrying out a crusade, returning unlawfully confiscated goods to the Roman Church or concession to canonical elections, which was why the marriage negotiations with the Pope failed.

In contrast to Otto, Philip was ready to honor the achievements of his loyal followers. The Hohenstaufen was able to attract high-ranking Welf supporters to his side through gifts and rewards. Rewarding the faithful was one of the most important duties of the ruler. Duke Ottokar I of Bohemia

Ottokar I (; 1155 – 1230) was Duke of Bohemia periodically beginning in 1192, then acquired the title of King of Bohemia, first in 1198 from Philip of Swabia, later in 1203 from Otto IV of Brunswick and in 1212 (as hereditary) from ...

received the royal dignity in 1198 for his support. Philip rewarded Count Wilhelm II of Jülich with valuable gifts for his expressed will to win over all of Otto's important supporters for the Hohenstaufen. Otto, however, refused to give his brother Henry

Henry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Henry (given name), including lists of people and fictional characters

* Henry (surname)

* Henry, a stage name of François-Louis Henry (1786–1855), French baritone

Arts and entertainmen ...

, the city of Braunschweig

Braunschweig () or Brunswick ( ; from Low German , local dialect: ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Lower Saxony, Germany, north of the Harz Mountains at the farthest navigable point of the river Oker, which connects it to the ...

and Lichtenberg Castle in the spring of 1204. Henry then went over to the Hohenstaufen side. For his change of loyalty, not only was the County Palatine of the Rhine

This article lists counts palatine of Lotharingia, counts palatine of the Rhine, and electors of the Palatinate (), the titles of three counts palatine who ruled some part of the Rhine region in the Kingdom of Germany and the Holy Roman Empire bet ...

restored to him by Philip, but he was also enfeoffed with the ''Vogtei'' over Goslar

Goslar (; Eastphalian dialect, Eastphalian: ''Goslär'') is a historic town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is the administrative centre of the Goslar (district), district of Goslar and is located on the northwestern wikt:slope, slopes of the Harz ...

and rewarded with monetary payments. The change of the Count Palatine was decisive for a broad movement away from the Welf.

During the siege of Weißensee on 17 September 1204, Landgrave Hermann of Thuringia humbly submitted to the Hohenstaufen. It is the only case of submission ('' deditio'') through which the historical source

A historical source encompasses "every kind of evidence that human beings have left of their past activities — the written word and spoken word, the shape of the landscape and the material artefact, the fine arts as well as photography and film." ...

s provide detailed information. According to chronicler Arnold of Lübeck, Philip held up to the Landgrave "while he was lying on the ground for so long" about his "disloyalty and stupidity". Only after the intercession of those present was he lifted from the floor and received the peace kiss from the King. Hermann had initially supported Otto, switched to Philip in 1199 and then again joined Otto in 1203/04. The Landgrave was able to retain his title and property after his submission and stayed in the Hohenstaufen side until Philip was murdered.

In November 1204 Archbishop Adolph of Cologne and Duke Henry I of Brabant also switched to Philip's side in Koblenz

Koblenz ( , , ; Moselle Franconian language, Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz'') is a German city on the banks of the Rhine (Middle Rhine) and the Moselle, a multinational tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman Empire, Roman military p ...

. The Duke of Brabant received Maastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; ; ; ) is a city and a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital city, capital and largest city of the province of Limburg (Netherlands), Limburg. Maastricht is loca ...

and Duisburg

Duisburg (; , ) is a city in the Ruhr metropolitan area of the western States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Lying on the confluence of the Rhine (Lower Rhine) and the Ruhr (river), Ruhr rivers in the center of the Rhine-Ruh ...

and the Archbishop of Cologne was able to retain his position in the election and ordination of a King and was rewarded with 5,000 marks for siding with Philip. The growing money traffic in the High Middle Ages influenced the princes in their decisions for military support or in the question of their partisanship. With the transfer of the Archbishop of Cologne to his side, Philip's documentary production also increased considerably. However, the majority of Cologne's citizens remained on the Welf's side. The support commitments of Archbishop Adolph and Henry I of Brabant were the first one documented since the Hohenstaufen- Zähringen agreement from 1152. The double election is therefore also seen as a turning point, as it marked the beginning of written alliances in the northern Alpine empire. The number of contracts concluded also rose during the controversy for the throne. However, these written agreements were regularly broken for political reasons. The nobles tried to use the political situation to expand their regional principalities. Landgrave Hermann of Thuringia, Philip's cousin, changed sides five times between the outbreak of the controversy and the election of Frederick II in September 1211. According to historian Stefan Weinfurter, the relativization of the oath by the Pope was also essential for the breach of contract. Pope Innocent III advised the spiritual and secular princes to submit to his judgment only. With the Duke of Brabant, Philip strengthens ties in 1207 with the betrothal of his daughter Maria with Henry

Henry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Henry (given name), including lists of people and fictional characters

* Henry (surname)

* Henry, a stage name of François-Louis Henry (1786–1855), French baritone

Arts and entertainmen ...

, heir of the Duchy of Brabant. As a result, Henry I should be closely tied to the Hohenstaufen monarchy.

After the protracted conflicts between the Archbishop of Cologne and Philip, order had to be restored in a demonstrative way. Philip moved into Cologne on the symbolic Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is the Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Its name originates from the palm bran ...

. The ''adventus'' (formally entry to a city) had "the function of a homage, a solemn recognition of the rule of the king". In addition, numerous Welf supporters on the Lower Rhine and from Westphalia had joined the Hohenstaufen side. Philip has now been able to unite a large number of supporters in the Holy Roman Empire behind him. The basis for Philip's success against Otto's followers was “a mixture of threats, promises and gifts”. On the occasion of the renewed coronation in Aachen, the Archbishop of Cologne went to meet Philip with “the greatest display of splendor and service” in front of the walls. In this way the Archbishop publicly recognized Philip as monarch. On 6 January 1205, Philip was crowned again with great ceremony at the traditional coronation site in Aachen

Aachen is the List of cities in North Rhine-Westphalia by population, 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, 27th-largest city of Germany, with around 261,000 inhabitants.

Aachen is locat ...

by the correct coronator ("''Königskröner''"), the Archbishop of Cologne. With this measure Philip took the honor of the Archbishop into consideration and, by safeguarding his coronation right in Aachen, made submission to the long-fought king acceptable to him. The repetition of the coronation also cleared up the taint of his first coronation in 1198.

On 27 July 1206, Philip defeated a Cologne army loyal to Otto in Wassenberg. This was the only time that the armies of the two kings met. After the battle, the two kings met for the first time. It took place in an atmosphere of confidentiality (''colloquium familiare'') and offered the necessary consideration for the honor of the two kings. Direct negotiations in public were rather unusual at the time. However, the negotiations failed. Pope Innocent III also noticed Otto's decline in the empire and a month or two later Philip was loosed from the papal ban. In 1207/08 the Pope approached Philip and negotiations about the imperial coronation began, and also it seemed probable that a treaty was concluded by which were renewed the marriage negotiations of the nephew of the Pope with one of Philip's daughters and to receive the disputed territory of Tuscany.

Court

From the 12th century thecourt

A court is an institution, often a government entity, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between Party (law), parties and Administration of justice, administer justice in Civil law (common law), civil, Criminal law, criminal, an ...

developed into a central institution of royal and princely rule. It was a “decision-making center and theater of power, consumer and entertainment center, distribution center, broker's seat for and for power, money and goods and social opportunities, for tastes, ideas and fashions of all kinds”. Medieval kingship was exercised in an empire without a capital through outpatient rulership practice. Philip had to go through the kingdom and thereby give his rule validity and authority. The greats of the empire gathered for deliberations on the court days. For Philip's reign, 28 ''Hoftag

A ''Hoftag'' (, pl. ''Hoftage'') was the name given to an informal and irregular assembly convened by the King of the Romans, the Holy Roman Emperor or one of the Princes of the Empire, with selected chief princes within the empire. Early schola ...

'' are known, of which only 12 took place within the Hohenstaufen sphere of influence. Somewhat more than 630 people can be found at Philip's court between 1198 and 1208, of whom around 100 belonged to the King's inner court, being "attested in a somewhat more noticeable density in the Hohenstaufen circle". The Bishops Konrad of Hildesheim, Hartwig of Eichstätt and Konrad IV of Regensburg and especially Konrad of Speyer joined to Philip's court. By contrast, none of the secular princes is as closely and frequently attested to at court as Bishop Konrad of Speyer. Duke Bernhard of Saxony, Duke Louis I of Bavaria and Margrave Theodoric I of Meissen probably had the most intensive contact within the court. They had profited significantly from the fall of Henry the Lion and feared that his son Otto IV would gain access to the Welf inheritance. The '' ministeriales'' had in Henry of Kalden their most outstanding representant: he was not only a military leader, but also influenced Philip's politics by arranging a personal encounter with Otto. He is mentioned in more than 30 charters and also in narrative sources.

The most important part of the court was the Chancery

Chancery may refer to:

Offices and administration

* Court of Chancery, the chief court of equity in England and Wales until 1873

** Equity (law), also called chancery, the body of jurisprudence originating in the Court of Chancery

** Courts of e ...

. Philip's Chancery was in the personal tradition of Henry VI. In other ways, too, Philip's document system does not differ from that of his Hohenstaufen predecessors. In contrast to his predecessors, his rival Otto IV and his nephew Frederick II, Philip had few seals. The ducal seals for Tuscany and Swabia as well as a wax seal and a gold bull for the royal period are verifiable. This is probably due to the fact that he did not obtain the imperial crown, because it would have led to a change in title. With his awarding of charters, Philip reached considerably further north, north-west (Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (, ), is the capital of the States of Germany, German state of the Bremen (state), Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (), a two-city-state consisting of the c ...

, Utrecht

Utrecht ( ; ; ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city of the Netherlands, as well as the capital and the most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of Utrecht (province), Utrecht. The ...

, Zutphen

Zutphen () is a city and municipality located in the province of Gelderland, Netherlands. It lies some northeast of Arnhem, on the eastern bank of the river IJssel at the point where it is joined by the Berkel. First mentioned in the 11th centur ...

) and south-west (Savoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

, Valence) to assert his kingship. With the issuing of charters, Philip wanted to bind his followers more closely to himself in these areas as well. His ''itinerarium

An ''itinerarium'' (plural: ''itineraria'') was an ancient Roman travel guide in the form of a listing of cities, villages ( ''vici'') and other stops on the way, including the distances between each stop and the next. Surviving examples include ...

'' is shaped like no other ruling rulers from the Hohenstaufen era by the political situation of the controversy for the throne. An almost orderly move through the empire with continuous notarial activity did not take place. Rather, a regionalization of itinerary, awarding of charters and visits to the court can be identified, which historian Bernd Schütte interpreted as a “withdrawal of the royal central authority”.

Philip is considered to be the "first Roman-German ruler whose court can be shown to have courtly poetry and who himself became the subject of courtly poetry." Walther von der Vogelweide

Walther von der Vogelweide (; ) was a Minnesänger who composed and performed love-songs and political songs ('' Sprüche'') in Middle High German. Walther has been described as the greatest German lyrical poet before Goethe; his hundred or s ...

dedicated a special song to the Magdeburg Court Day of 1199, in which he honored Philip as ruler. During his short reign, Philip didn't have the opportunity to promote art or build buildings. Spiritual institutions were not particularly promoted by him.

Death

Since the end of May 1208, Philip had been preparing for a campaign against Otto IV and his allies. He interrupted the planning to attend the wedding of his niece Countess Beatrice II of Burgundy with Duke Otto of Merania on 21 June in

Since the end of May 1208, Philip had been preparing for a campaign against Otto IV and his allies. He interrupted the planning to attend the wedding of his niece Countess Beatrice II of Burgundy with Duke Otto of Merania on 21 June in Bamberg

Bamberg (, , ; East Franconian German, East Franconian: ''Bambärch'') is a town in Upper Franconia district in Bavaria, Germany, on the river Regnitz close to its confluence with the river Main (river), Main. Bamberg had 79,000 inhabitants in ...

. After the marriage, the King retired to his private apartments. In the afternoon he was murdered by Count Otto VIII of Wittelsbach. After the murder, Count Otto VIII was able to flee with his followers. Bishop Ekbert of Bamberg and his brother, Margrave Henry II of Istria, were suspected of having known about the plans. Other medieval historians expressed doubts about complicity or ignored other possible perpetrators.

For the first time since the end of the Merovingian dynasty

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from around the middle of the 5th century until Pepin the Short in 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the ...

a king had been murdered. Besides Albert I of Habsburg (1308), Philip is the only Roman-German ruler to be assassinated. No chronicler witnessed the murder. In contemporary sources there is little agreement about the course of the murder. Most medieval chroniclers saw the withdrawal of the promise of marriage as a motive for murder. Even in distant Piacenza

Piacenza (; ; ) is a city and (municipality) in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Piacenza, eponymous province. As of 2022, Piacenza is the ninth largest city in the region by population, with more ...

, Philip's murder was still associated with a failed marriage project. Allegedly the Wittelsbach scion, already known for his unstable character, had fallen into a rage when he learned of the dissolution of his betrothal to Gertrude of Silesia by her father, the Piast

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of King Casimir III the Great.

Branches of ...

Duke Henry I the Bearded

Henry the Bearded (, ; c. 1165/70 – 19 March 1238) was a Polish duke from the Piast dynasty.

He was Dukes of Silesia, Duke of Silesia at Wrocław from 1201, Seniorate Province, Duke of Kraków and List of Polish monarchs, High Duke of all Kin ...

, who was apparently informed of Count Otto VIII's cruel tendencies and in an act of concern for his young daughter decided to terminate the marriage agreement. Later, after an unfortunate campaign to Thuringia, Philip had betrothed his third daughter Kunigunde to Count Otto VIII in the summer of 1203 in order to make him a reliable ally in the fight against Landgrave Hermann I of Thuringia. In the following years Philip increasingly succeeded in gaining acceptance for his kingship, so the betrothal with the Wittelsbach became without purpose to him; in November 1207 the King engaged Kunigunde to Wenceslaus

Wenceslaus, Wenceslas, Wenzeslaus and Wenzslaus (and other similar names) are Latinized forms of the Slavic names#In Slovakia and Czech_Republic, Czech name Václav. The other language versions of the name are , , , , , , among others. It origina ...

, son and heir of King Ottokar I of Bohemia, on the ''Hoftag'' in Augsburg

Augsburg ( , ; ; ) is a city in the Bavaria, Bavarian part of Swabia, Germany, around west of the Bavarian capital Munich. It is a College town, university town and the regional seat of the Swabia (administrative region), Swabia with a well ...

. Philip hoped that this alliance would gain permanent support from Bohemia. For Count Otto VIII this behavior was an act of treason and also felt that his social status was threatened; he swore revenge on the German King, whom he blame for both spurned betrothals, culminating in the murder at Bamberg.

Since historian Eduard Winkelmann's careful analysis in the 19th century, research has assumed that Otto VIII of Wittelsbach acted as a lone perpetrator. In contrast, historian Bernd Ulrich Hucker made a “comprehensive conspiratorial plan” in 1998 and suspected a “coup d'état”. The Andechs

Andechs is a municipality in the district of Starnberg in Bavaria in Germany. It is renowned in Germany and beyond for Andechs Abbey, a Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB ...

Dukes of Merania, King Philip II of France and Duke Henry I of Brabant should have been involved in this comprehensive plot; allegedly, the conspirators had planned to put the Duke of Brabant on the German throne. But Hucker's coup hypothesis did not prevail. It remains to be seen what use the French king would have had from the removal of Philip and his replacement by the Duke of Brabant. The House of Andechs, as loyal followers of Philip, who often stayed at his court and were protected by him, had no interest in his death.

Aftermath

Philip was initially buried inBamberg Cathedral

Bamberg Cathedral (, official name Bamberger Dom St. Peter und St. Georg) is a church in Bamberg, Germany, completed in the 13th century. The cathedral is under the administration of the Archdiocese of Bamberg and is the seat of Archbishop of ...

, the burial place of Emperor Henry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...

and King Conrad III. His rival Otto IV let the assassins be persecuted relentlessly and wanted to prove his innocence. Only the ''Annales Pegaviensis'' (chronicle of the Pegau Abbey) held Otto IV's supporters responsible for the murder. Philip's widow, Irene-Maria, pregnant at that time, took refuge in Hohenstaufen Castle

Hohenstaufen Castle () is a ruined castle in Göppingen in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The hill castle was built in the 11th century, on a conical hill between the Rems and Fils rivers (both tributaries of the Neckar) in what was then the Duch ...

, dying only two months after the Bamberg regicide as a result of a miscarriage. After Philip's death, Otto IV quickly prevailed against the remaining Hohenstaufen supporters, was acknowledged as German monarch at an Imperial Diet in Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

in November 1208 and crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Innocent III the next year. For the new fully recognized German King, the most important goal was to restore order in the realm. A ''Landfrieden

Under the law of the Holy Roman Empire, a ''Landfrieden'' or ''Landfriede'' (Latin: ''constitutio pacis'', ''pax instituta'' or ''pax jurata'', variously translated as "land peace", or "public peace") was a contractual waiver of the use of legiti ...

'' was established for this purpose and the Imperial ban

The imperial ban () was a form of outlawry in the Holy Roman Empire. At different times, it could be declared by the Holy Roman Emperor, by the Imperial Diet, or by courts like the League of the Holy Court (''Vehmgericht'') or the '' Reichskammerg ...

on Philip's murderer and alleged accomplices, the Andechs brothers Bishop Ekbert of Bamberg and Margrave Henry II of Istria, was imposed. As a result, they lost all offices, rights and property. In addition, Otto IV's engagement to Beatrix, Philip's eldest daughter, was agreed. Philip's murderer Otto VIII of Wittelsbach (now condemned as '' vogelfrei'') was found in March 1209 by ''Reichsmarschall'' Henry of Kalden in a granary on the Danube near Regensburg and beheaded. The Andechs brothers, however, were politically rehabilitated three years later.

However, Otto IV soon entered into conflict with Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

when he tried to conquer the Kingdom of Sicily in 1210, which led to his excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in Koinonia, communion with other members o ...

. The Welf lost the consensus on his rule in the part of the empire north of the Alps, and part of the princes renounced to their vow of obedience to Otto IV and chose Philip's nephew Frederick II as a rival emperor (''alium imperatorem''). In 1212 Frederick II moved to the northern part of the empire. At the turn of the year 1213/14, Frederick II's rule in the empire north of the Alps was not yet secured. In this situation, Frederick II had Philip's remains transferred from Bamberg to Speyer

Speyer (, older spelling ; ; ), historically known in English as Spires, is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate in the western part of the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located on the left bank of the r ...

. Personally, Frederick II does not seem to have come to Bamberg for the transfer of the body. Bamberg was possibly avoided by the later Hohenstaufen rulers because of Philip's murder. At Christmas 1213 Philip's mortal remains were re-interred in Speyer Cathedral

Speyer Cathedral, officially ''the Imperial Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption and St Stephen'', in Latin: Domus sanctae Mariae Spirae (German: ''Dom zu Unserer lieben Frau in Speyer'') in Speyer, Germany, is the seat of the Roman Catholic Bish ...

, which was considered a memorial of the Salian-Staufen dynasty and was the most important burial place of the Roman-German kingship. By transferring there his uncle Philip's remains, Frederick II was able to gain the trust of the Hohenstaufen partisans and strengthened his position against his opponents. From the mid-13th century, the death anniversary of Philip was celebrated in Speyer in a way similar to that of the Salian Emperor Henry IV. Philip is the last Roman-German king who is listed in both medieval dead books of the Speyer Cathedral. The Bamberg Horseman, a figure carved in stone on Bamberg Cathedral around 1235, has repeatedly been referred to as Philip; so historian Hans Martin Schaller sees in him the attempt to maintain Philip's memory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembe ...

. But the figure was also mistaken for either the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

, King Saint Stephen I of Hungary

Stephen I, also known as King Saint Stephen ( ; ; ; 975 – 15 August 1038), was the last grand prince of the Hungarians between 997 and 1000 or 1001, and the first king of Hungary from 1000 or 1001 until his death in 1038. The year of his bi ...

, or Emperors Henry II and Frederick II.

Medieval judgements

Many chroniclers saw the divine order represented by the ruler as a result of the conflict between the two kings for the throne. Philip is described in detail in the chronicle of thepremonstratensian

The Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré (), also known as the Premonstratensians, the Norbertines and, in Britain and Ireland, as the White Canons (from the colour of their habit), is a religious order of canons regular in the Catholic Chur ...

priest Burchard of Ursperg. Burchard wrote a continuation of the World Chronicle (''Chronicon universale'') of Ekkehard of Aura and Frutolf of Michelsberg in 1229/30. The chronicle is one of the most important sources for the history of the empire at the beginning of the 13th century. For the chronicler (who was loyal to the Hohenstaufen), Philip was of a meek and mild disposition, of affable speech, kind and quite generous, while Otto IV was not named with the title of king until Philip was murdered. Despite great physical strength, the Welf lacked all the important virtues of rulership; for Burchard, he was “haughty and stupid, but brave and tall” (''superbus et stultus, sed fortis videbatur viribus et statura procerus''). The chronicler Arnold of Lübeck, despite being loyal to the Welf dynasty, called Philip an "ornament of virtues". Arnold portrayed Otto IV's rule through the murder of Philip as being cursed by God. The image of Philip in posterity had a major impact on Walther von der Vogelweide

Walther von der Vogelweide (; ) was a Minnesänger who composed and performed love-songs and political songs ('' Sprüche'') in Middle High German. Walther has been described as the greatest German lyrical poet before Goethe; his hundred or s ...

, who referred to him in an honorable short form as "young and brave man".

The Bamberg regicide had no major impact on the further history of the empire. Later chroniclers and annals describe the transition of the royal rule from Philip to Otto IV as smooth. However, after the experience of the dynastic dispute over in the empire, a considerable development spurt began, which led to a rethink in writing down the customs. The ''Sachsenspiegel

The (; ; modern ; all literally "Saxon Mirror") is one of the most important law books and custumals compiled during the Holy Roman Empire. Originating between 1220 and 1235 as a record of existing local traditional customary laws and ruling ...

'' of Eike of Repgow

Eike of Repgow (, also ''von Repkow'', ''von Repko'', ''von Repchow'' or ''von Repchau''; – ) was a medieval German administrator who compiled the ''Sachsenspiegel'' code of law in the 13th century.

Life

Little is known about Eike of Repgow, b ...

is an important testimony to this.

Artistic reception

In modern times, little was remembered of Philip of Swabia. He fell significantly behind the other Hohenstaufen rulersFrederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (; ), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death in 1190. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen on 9 March 115 ...

and Frederick II. His reign, which was limited to a few years, was never undisputed, and he was never crowned Holy Roman Emperor. In addition, he hadn't fought a major conflict with the Pope, in which the alleged failure of the medieval central authority could have been exemplified. In addition, his name cannot be associated with any extraordinary conception of power. Furthermore, his murder could not be instrumentalized for sectarian disputes or for the establishment of a German nation-state in the 19th century.

Representations of the Bamberg regicide are rarely found in history painting

History painting is a genre in painting defined by its subject matter rather than any artistic style or specific period. History paintings depict a moment in a narrative story, most often (but not exclusively) Greek and Roman mythology and B ...

. Alexander Zick

Alexander Zick (born 20 December 1845, Koblenz, Germany – 10 November 1907, Berlin, Germany) was a German painter and illustrator.

The Zick family included multiple generations of painters. Alexander was the son of Gustav Zick, a painter ...

made a drawing of the murder in 1890, and Karl Friedrich Lessing made a draft without converting it into a painting. On 4 July 1998, Rainer Lewandowski's play “The King's Murder in Bamberg” was premiered at the E.T.A.-Hoffmann-Theater in Bamberg.

Historical research

Historical research of the 19th and early 20th century was hampered by historians anachronistically projecting their contemporary political preferences backwards in time. Due to the contemporaryKulturkampf

In the history of Germany, the ''Kulturkampf'' (Cultural Struggle) was the seven-year political conflict (1871–1878) between the Catholic Church in Germany led by Pope Pius IX and the Kingdom of Prussia led by chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Th ...

, nationalist Protestant historians viewed the Catholic church or anything that smacked of ultramontanism