Phaedo (dialogue) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Phaedo'' (; , ''Phaidōn'') is a

The Phaedo is Plato's fourth and last

The Phaedo is Plato's fourth and last

Perseus

*Plato. ''Opera'', volume I. Oxford Classical Texts. *Plato. ''Phaedo''. Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics. Greek text with introduction and commentary by C. J. Rowe. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Perseus

*''Plato: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo.'' Greek with translation by Chris Emlyn-Jones and William Preddy. Loeb Classical Library 36. Harvard Univ. Press, 2017.

HUP listing

h2>

BBC radio play

in 1986. *''Plato: Phaedo.'' Hackett Classics, 2nd edition. Hackett Publishing Company, 1977. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. *Plato. ''Complete Works.'' Hackett, 1997. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. *''Plato: Meno and Phaedo.'' Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy. By David Sedley (Editor) and Alex Long (Translator). Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Approaching Plato: A Guide to the Early and Middle Dialogues

a beginner's guide

* * ;Online versions *

full text

* George Theodoridis, 2016

full text

{{Authority control Afterlife Dialogues of Plato Works about philosophy of death he:פאידון

dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American and British English spelling differences, American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literature, literary and theatrical form that depicts suc ...

written by Plato, in which Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

discusses the immortality of the soul and the nature of the afterlife

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's Stream of consciousness (psychology), stream of consciousness or Personal identity, identity continues to exist after the death of their ...

with his friends in the hours leading up to his death. Socrates explores various arguments for the soul's immortality with the Pythagorean philosophers Simmias and Cebes of Thebes in order to show that there is an afterlife in which the soul will dwell following death. The dialogue concludes with a mythological narrative of the descent into Tarturus and an account of Socrates' final moments before his execution.

Background

The dialogue is set in 399 BCE, in an Athenian prison, during the last hours prior to the death ofSocrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

. It is presented within a frame story

A frame story (also known as a frame tale, frame narrative, sandwich narrative, or intercalation) is a literary technique that serves as a companion piece to a story within a story, where an introductory or main narrative sets the stage either fo ...

by Phaedo of Elis

Phaedo of Elis (; also, ''Phaedon''; , ''gen''.: Φαίδωνος; fl. 4th century BCE) was a Greek philosopher. A native of Elis, he was captured in war as a boy and sold into slavery. He subsequently came into contact with Socrates at A ...

, who is recounting the events to Echecrates, a Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

. Characters

Speakers in the frame story: *Phaedo

''Phaedo'' (; , ''Phaidōn'') is a dialogue written by Plato, in which Socrates discusses the immortality of the soul and the nature of the afterlife with his friends in the hours leading up to his death. Socrates explores various arguments fo ...

of Elis

Elis also known as Ellis or Ilia (, ''Eleia'') is a historic region in the western part of the Peloponnese peninsula of Greece. It is administered as a regional unit of the modern region of Western Greece. Its capital is Pyrgos. Until 2011 it ...

: a follower of Socrates, a youth allegedly enslaved as a prisoner of war, whose freedom was purchased at Socrates' request. He later founded a school of philosophy.

* Echecrates of Phlius

Phlius (; ) or Phleius () was an independent polis (city-state) in the northeastern part of Peloponnesus. Phlius' territory, called Phliasia (), was bounded on the north by Sicyonia, on the west by Arcadia, on the east by Cleonae, and on the ...

: A Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

philosopher about whom little else is known.

Speakers in the main part of the dialogue:

* Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

of Alopece

Alopece (), also spelt as Alopecae, was an asty-deme of the city of Athens, but located exterior to the city wall of Athens. Alopece belonged to the tribal group (''phyle'') of Antiochis. It was situated only eleven or twelve stadia from the c ...

: a philosopher in his 70s, sentenced to death by the Athenians for impiety.

* Simmias and Cebes of Thebes: followers of Socrates and students of the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus of Croton

Philolaus (; , ''Philólaos''; )

was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pythagorean tradition and t ...

. As relayed in the ''Crito

''Crito'' ( or ; ) is a dialogue written by the ancient Greece, ancient Greek philosopher Plato. It depicts a conversation between Socrates and his wealthy friend Crito of Alopece regarding justice (''δικαιοσύνη''), injustice (''ἀ ...

'', which takes place a day or two earlier, they had arranged a plan to help Socrates escape from prison and live in exile, which he had declined.

* Crito

''Crito'' ( or ; ) is a dialogue written by the ancient Greece, ancient Greek philosopher Plato. It depicts a conversation between Socrates and his wealthy friend Crito of Alopece regarding justice (''δικαιοσύνη''), injustice (''ἀ ...

of Alopece: a childhood friend of Socrates, who unsuccessfully attempts to convince him to escape from prison in the ''Crito''. In the ''Phaedo'', he takes responsibility for Socrates' body after his death and sacrifices a rooster to Asclepius

Asclepius (; ''Asklēpiós'' ; ) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of Apollo), Coronis, or Arsinoe (Greek myth), Ars ...

on his behalf.

Other people present:

* Xanthippe

Xanthippe (; ; fl. 5th–4th century BCE) was an Classical Athens, ancient Athenian, the wife of Socrates and mother of their three sons: Lamprocles, Sophroniscus, and Menexenus. She was likely much younger than Socrates, perhaps by as much as ...

, wife of Socrates: early in the dialogue, she becomes distressed, and Socrates has her taken away. Plato's portrayal of her is generally sympathetic, unlike Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

and later biographers, who portray her as inter-personally difficult and unpleasant.

* Lamprocles

Lamprocles () was Socrates' and Xanthippe's eldest son. His two brothers were Menexenus and Sophroniscus. Lamprocles was a youth (μειράκιον ''meirakion'') at the time of Socrates' trial and death. According to Aristotle, Socrates' desc ...

, Sophroniscus

Sophroniscus (Greek: Σωφρονίσκος, ''Sophroniskos''), husband of Phaenarete, was the father of the philosopher Socrates.

Occupation

Little is known about Sophroniscus and his relationship with his son Socrates. According to tradition, ...

, Menexenus

Menexenus (; ) was one of the three sons of Socrates and Xanthippe. His two brothers were Lamprocles and Sophroniscus. Menexenus is not to be confused with the character of the same name who appears in Plato's dialogues ''Menexenus'' and ''Ly ...

, sons of Socrates: aged roughly 17, 11, and 3 respectively.

* Apollodorus

Apollodorus ( Greek: Ἀπολλόδωρος ''Apollodoros'') was a popular name in ancient Greece. It is the masculine gender of a noun compounded from Apollo, the deity, and doron, "gift"; that is, "Gift of Apollo." It may refer to:

:''Note: A ...

of Phaleron: A follower of Socrates who is unable to stop weeping, he is frequently portrayed by others as flamboyant and manic. He also appears in the ''Symposium

In Ancient Greece, the symposium (, ''sympósion'', from συμπίνειν, ''sympínein'', 'to drink together') was the part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was accompanied by music, dancing, recitals, o ...

'', where he relates the narrative of the dialogue to a friend, and in the ''Apology

Apology, The Apology, apologize/apologise, apologist, apologetics, or apologetic may refer to:

Common uses

* Apology (act), an expression of remorse or regret

* Apologia, a formal defense of an opinion, position, or action

Arts, entertainment ...

'', where he offers up funds to pay Socrates' fine.

* Critobulus of Alopece, son of Crito

* Hermogenes of Alopece: a follower of Socrates. He is also one of the main speakers in Plato's ''Cratylus

Cratylus ( ; , ''Kratylos'') was an ancient Athenian philosopher from the mid-late 5th century BC, known mostly through his portrayal in Plato's dialogue '' Cratylus''. He was a radical proponent of Heraclitean philosophy and influenced the you ...

''.

* Epigenes, son of Antiphon: A follower of Socrates, about whom nothing else is known.

* Aeschines of Sphettus: a Socratic philosopher who wrote dialogues, some fragments of which survive.

* Antisthenes

Antisthenes (; , ; 446 366 BCE) was a Greek philosopher and a pupil of Socrates. Antisthenes first learned rhetoric under Gorgias before becoming an ardent disciple of Socrates. He adopted and developed the ethical side of Socrates' teachings, ...

: a Socratic philosopher and student of Gorgias

Gorgias ( ; ; – ) was an ancient Greek sophist, pre-Socratic philosopher, and rhetorician who was a native of Leontinoi in Sicily. Several doxographers report that he was a pupil of Empedocles, although he would only have been a few years ...

, he wrote philosophical dialogues and speeches, none of which have survive. Later members of the Cynic school of philosophy saw him as their founder.

* Ctesippus of Paeania: A follower of Socrates, about whom little is known outside his appearance in the ''Lysis

Lysis ( ; from Greek 'loosening') is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ...

'' and '' Euthydemus''.

* Menexenus, son of Demophon: A follower of Socrates, he is a speaker in the ''Lysis

Lysis ( ; from Greek 'loosening') is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ...

'' and in the ''Menexenus

Menexenus (; ) was one of the three sons of Socrates and Xanthippe. His two brothers were Lamprocles and Sophroniscus. Menexenus is not to be confused with the character of the same name who appears in Plato's dialogues ''Menexenus'' and ''Ly ...

'', which is named after him.

* Phaedondas of Thebes: According to Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

, Phaedondas was a member of Socrates' inner circle along with Crito, Simmias, and Cebes. However, nothing else about him is known.

* Euclid

Euclid (; ; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of geometry that largely domina ...

of Megara

Megara (; , ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis Island, Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken ...

: a Socratic philosopher, founder of the Megarian school

The Megarian school of philosophy, which flourished in the 4th century BC, was founded by Euclides of Megara, one of the pupils of Socrates. Its ethical teachings were derived from Socrates, recognizing a single good, which was apparently combine ...

. He appears in the prologue of the '' Theaetetus''.

* Terpsion of Megara: A friend of Euclid, about whom little else is known. He also appears with Euclid in the ''Theaetetus'' prologue.

Historical context

The Phaedo is Plato's fourth and last

The Phaedo is Plato's fourth and last dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American and British English spelling differences, American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literature, literary and theatrical form that depicts suc ...

to detail the philosopher's final days, following ''Euthyphro

''Euthyphro'' (; ), is a philosophical work by Plato written in the form of a Socratic dialogue set during the weeks before the trial of Socrates in 399 BC. In the dialogue, Socrates and Euthyphro attempt to establish a definition of '' piet ...

'', ''Apology

Apology, The Apology, apologize/apologise, apologist, apologetics, or apologetic may refer to:

Common uses

* Apology (act), an expression of remorse or regret

* Apologia, a formal defense of an opinion, position, or action

Arts, entertainment ...

'', and ''Crito

''Crito'' ( or ; ) is a dialogue written by the ancient Greece, ancient Greek philosopher Plato. It depicts a conversation between Socrates and his wealthy friend Crito of Alopece regarding justice (''δικαιοσύνη''), injustice (''ἀ ...

''. According to the dialogues, Socrates has been imprisoned and sentenced to death by an Athenian

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

jury for impiety.

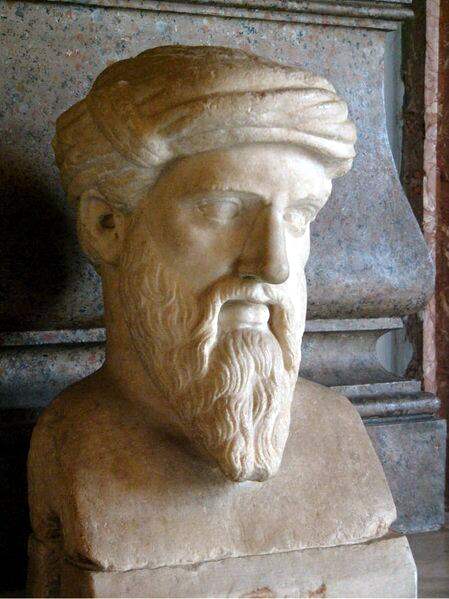

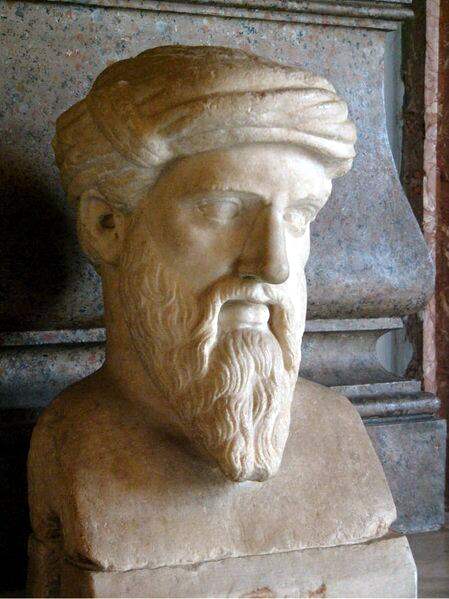

Many of the key characters in the dialogue are associated with Pythagoreanism

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek co ...

, a religious and philosophical doctrine that flourished early 5th century BCE, which taught the immortality and reincarnation of the soul after death. Simmias and Cebes are both stated in the dialogue to have studied under Philolaus of Croton

Philolaus (; , ''Philólaos''; )

was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pythagorean tradition and t ...

, one of the most prominent Pythagorean philosophers, and Echecrates, who is hearing the dialogue from Phaedo, is a Pythagorean from Phlius, which was a stronghold of Pythagoreanism well into the 4th century BCE, when the dialogue is set. Many of the topics that are discussed in the dialogue are thought to derive from the doctrines of Philolaus, including the discussion of suicide, the alternation of opposites, and the harmonic attunement of the soul. Plato himself likely learned Pythagorean doctrines from his close friendship with Archytas of Tarentum, a philosopher and statesman from Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

who made contributions to mechanics, number theory, and acoustics.

Style, dating, and authorship

The ''Phaedo'' is one of thedialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American and British English spelling differences, American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literature, literary and theatrical form that depicts suc ...

s of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's middle period, along with the ''Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

'' and the ''Symposium

In Ancient Greece, the symposium (, ''sympósion'', from συμπίνειν, ''sympínein'', 'to drink together') was the part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was accompanied by music, dancing, recitals, o ...

.''

Summary

The dialogue is told from the perspective of one of Socrates's students,Phaedo of Elis

Phaedo of Elis (; also, ''Phaedon''; , ''gen''.: Φαίδωνος; fl. 4th century BCE) was a Greek philosopher. A native of Elis, he was captured in war as a boy and sold into slavery. He subsequently came into contact with Socrates at A ...

, who was present at Socrates's death bed. Phaedo relates the dialogue from that day to Echecrates, a Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

.

Phaedo explains that a delay occurred between Socrates' trial and his death, because the trial had occurred during the annual voyage of the Ship of Theseus

The Ship of Theseus, also known as Theseus's Paradox, is a paradox and a common thought experiment about whether an object is the same object after having all of its original components replaced over time, typically one after the other.

In Gre ...

to Delos

Delos (; ; ''Dêlos'', ''Dâlos''), is a small Greek island near Mykonos, close to the centre of the Cyclades archipelago. Though only in area, it is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. ...

, during which time the city is kept "pure" and no executions are performed. Phaedo then tells Echecrates who else was present on the day of the execution, and how Socrates's wife Xanthippe

Xanthippe (; ; fl. 5th–4th century BCE) was an Classical Athens, ancient Athenian, the wife of Socrates and mother of their three sons: Lamprocles, Sophroniscus, and Menexenus. She was likely much younger than Socrates, perhaps by as much as ...

was there, but was very distressed and Socrates asked that she be taken away.

Introduction

Socrates, who has just been released from his chains, remarks on the irony that pleasure and pain, while opposites, are frequently encountered one after the other; people who pursue pleasure often find themselves in pain soon after, while he is experiencing pleasure having been removed from bonds that were causing pains in his leg. Cebes, on behalf of Socrates' friend Evenus, asks Socrates about the poetry he has been writing while in prison, and Socrates relates how, bidden by a recurring dream to "make and cultivate music", he wrote a hymn and then began writing poetry based onAesop's Fables

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a Slavery in ancient Greece, slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 Before the Common Era, BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stor ...

.

Socrates tells Cebes to "bid Evenus farewell from me; say that I would have him come after me if he be a wise man." Simmias expresses confusion as to why they ought hasten to follow Socrates to death. Socrates then states "... he, who has the spirit of philosophy, will be willing to die; but he will not take his own life." Cebes raises his doubts as to why we should be eager to die, if suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

is prohibited. Socrates replies that while death is the ideal home of the soul, to commit suicide is prohibited as man is not sole possessor of his body, he is actually the property of the gods

A deity or god is a supernatural being considered to be sacred and worthy of worship due to having authority over some aspect of the universe and/or life. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines ''deity'' as a God (male deity), god or god ...

. But the philosopher always to rid himself of the body even in life, to focus solely on things concerning the soul, because the body is an impediment to the attainment of truth.

Of the senses' failings, Socrates says to Simmias in the ''Phaedo'':

Did you ever reach them (truths) with any bodily sense? – and I speak not of these alone, but of absolute greatness, and health, and strength, and, in short, of the reality or true nature of everything. Is the truth of them ever perceived through the bodily organs? Or rather, is not the nearest approach to the knowledge of their several natures made by him who so orders his intellectual vision as to have the most exact conception of the essence of each thing he considers?The philosopher, if he loves true wisdom and not the passions and appetites of the body, accepts that he can come closest to true knowledge and wisdom in death, as he is no longer confused by the body and the senses. In life, the rational and intelligent functions of the soul are restricted by bodily senses of pleasure, pain, sight, and sound. Death, however, is a rite of purification from the "infection" of the body. As the philosopher prepares for death his entire life, he should greet it amicably and not be discouraged upon its arrival, for since the universe the gods created for us in life is essentially "good", why would death be anything but a continuation of this goodness? Death is a place where better and wiser gods rule and where the most noble souls serve in their presence: "And therefore, so far as that is concerned, I not only do not grieve, but I have great hopes that there is something in store for the dead ... something better for the good than for the wicked." The soul attains virtue when it is purified from the body: "He who has got rid, as far as he can, of eyes and ears and, so to speak, of the whole body, these being in his opinion distracting elements when they associate with the soul hinder her from acquiring truth and knowledge – who, if not he, is likely to attain to the knowledge of true being?" Cebes voices his fear of death to Socrates: "... they fear that when she he soulhas left the body her place may be nowhere, and that on the very day of death she may perish and come to an end immediately on her release from the body ... dispersing and vanishing away into nothingness in her flight." In order to alleviate Cebes's worry that the soul might perish at death, Socrates introduces four arguments for the soul's immortality:

Cyclical argument

The first argument for the immortality of the soul, often called the ''Cyclical Argument'', supposes that the soul must be immortal since the living come from the dead. Socrates says: "Now if it be true that the living come from the dead, then our souls must exist in the other world, for if not, how could they have been born again?". He goes on to show, using examples of relationships, such as asleep-awake and hot-cold, that things that have opposites come to be from their opposite. One falls asleep after having been awake. And after being asleep, he awakens. Things that are hot came from being cold and vice versa. Socrates then gets Cebes to conclude that the dead are generated from the living, through life, and that the living are generated from the dead, through death. The souls of the dead must exist in some place for them to be able to return to life. Socrates further emphasizes the cyclical argument by pointing out that if opposites did not regenerate one another, all living organisms on Earth would eventually die off, never to return to life.Recollection argument

Cebes realizes the relationship between the ''Cyclical Argument'' and Socrates' ''Theory of Recollection''. He interrupts Socrates to point this out, saying:... your favorite doctrine, Socrates, that our learning is simply recollection, if true, also necessarily implies a previous time in which we have learned that which we now recollect. But this would be impossible unless our soul had been somewhere before existing in this form of man; here then is another proof of the soul's immortality.Socrates' second argument, which is based Plato's based on the '' theory of recollection'' at outlined in the ''

Meno

''Meno'' (; , ''Ménōn'') is a Socratic dialogue written by Plato around 385 BC., but set at an earlier date around 402 BC. Meno begins the dialogue by asking Socrates whether virtue (in , '' aretē'') can be taught, acquired by practice, o ...

'', posits that, since it is possible to draw information out of a person who seems not to have any knowledge of a subject prior to his being questioned about it, that implies that the soul existed before birth to carry that knowledge, and is now merely recalling it from memory.

Affinity argument

Socrates presents his third argument for the immortality of the soul, the so-called ''Affinity Argument'', where he shows that the soul most resembles that which is invisible and divine, and the body resembles that which is visible and mortal. From this, it is concluded that while the body may be seen to exist after death in the form of a corpse, as the body is mortal and the soul is divine, the soul must outlast the body. As to be truly virtuous during life is the quality of a great man who will perpetually dwell as a soul in the underworld. However, regarding those who were not virtuous during life, and so favored the body and pleasures pertaining exclusively to it, Socrates also speaks. He says that such a soul is:... polluted, is impure at the time of her departure, and is the companion and servant of the body always and is in love with and bewitched by the body and by the desires and pleasures of the body, until she is led to believe that the truth only exists in a bodily form, which a man may touch and see, and drink and eat, and use for the purposes of his lusts, the soul, I mean, accustomed to hate and fear and avoid that which to the bodily eye is dark and invisible, but is the object of mind and can be attained by philosophy; do you suppose that such a soul will depart pure and unalloyed?Persons of such a constitution will be dragged back into corporeal life, according to Socrates. These persons will even be punished while in Hades. Their punishment will be of their own doing, as they will be unable to enjoy the singular existence of the soul in death because of their constant craving for the body. These souls are finally "imprisoned in another body". Socrates concludes that the soul of the virtuous man is immortal, and the course of its passing into the underworld is determined by the way he lived his life. The philosopher, and indeed any man similarly virtuous, in neither fearing death, nor cherishing corporeal life as something idyllic, but by loving truth and wisdom, his soul will be eternally unperturbed after the death of the body, and the afterlife will be full of goodness. Simmias confesses that he does not wish to disturb Socrates during his final hours by unsettling his belief in the immortality of the soul, and those present are reluctant to voice their

skepticism

Skepticism ( US) or scepticism ( UK) is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the p ...

. Socrates grows aware of their doubt and assures his interlocutors that he does indeed believe in the soul's immortality, regardless of whether or not he has succeeded in showing it as yet. For this reason, he is not upset facing death and assures them that they ought to express their concerns regarding the arguments. Simmias then presents his case that the soul resembles the harmony of the lyre

The lyre () (from Greek λύρα and Latin ''lyra)'' is a string instrument, stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the History of lute-family instruments, lute family of instruments. In organology, a ...

. It may be, then, that as the soul resembles the harmony in its being invisible and divine, once the lyre has been destroyed, the harmony too vanishes, therefore when the body dies, the soul too vanishes. Once the harmony is dissipated, we may infer that so too will the soul dissipate once the body has been broken, through death.

Socrates pauses, and asks Cebes to voice his objection as well. He says, "I am ready to admit that the existence of the soul before entering into the bodily form has been ... proven; but the existence of the soul after death is in my judgment unproven." While admitting that the soul is the better part of a man, and the body the weaker, Cebes is not ready to infer that because the body may be perceived as existing after death, the soul must therefore continue to exist as well. Cebes gives the example of a weaver. When the weaver's cloak wears out, he makes a new one. However, when he dies, his more freshly woven cloaks continue to exist. Cebes continues that though the soul may outlast certain bodies, and so continue to exist after certain deaths, it may eventually grow so weak as to dissolve entirely at some point. He then concludes that the soul's immortality has yet to be shown and that we may still doubt the soul's existence after death. For, it may be that the next death is the one under which the soul ultimately collapses and exists no more. Cebes would then, "... rather not rely on the argument from superior strength to prove the continued existence of the soul after death."

Seeing that the Affinity Argument has possibly failed to show the immortality of the soul, Phaedo pauses his narration. Phaedo remarks to Echecrates that, because of this objection, those present had their "faith shaken", and that there was introduced "a confusion and uncertainty". Socrates too pauses following this objection and then warns against misology, the hatred of argument.

Final argument

Socrates then proceeds to give his final proof of theimmortality

Immortality is the concept of eternal life. Some species possess "biological immortality" due to an apparent lack of the Hayflick limit.

From at least the time of the Ancient Mesopotamian religion, ancient Mesopotamians, there has been a con ...

of the soul by showing that the soul is immortal as it is the cause of life. He begins by showing that "if there is anything beautiful other than absolute beauty it is beautiful only insofar as it partakes of absolute beauty".

Consequently, as absolute beauty is a ''Form,'' and so is life, then anything which has the property of being animated with life, participates in the Form. As an example he says, "will not the number three endure annihilation or anything sooner than be converted into an even number, while remaining three?". Forms, then, will never become their opposite. As the soul is that which renders the body living, and that the opposite of life is death, it so follows that, "... the soul will never admit the opposite of what she always brings." That which does not admit death is said to be immortal.

Legacy

Plato's ''Phaedo'' had a significant readership throughout antiquity, and was commented on by a number of ancient philosophers, such as Harpocration of Argos, Porphyry,Iamblichus

Iamblichus ( ; ; ; ) was a Neoplatonist philosopher who determined a direction later taken by Neoplatonism. Iamblichus was also the biographer of the Greek mystic, philosopher, and mathematician Pythagoras. In addition to his philosophical co ...

, Paterius, Plutarch of Athens

Plutarch of Athens (; c. 350 – 430 AD) was a Greek philosopher and Neoplatonist who taught in Athens at the beginning of the 5th century. He reestablished the Platonic Academy there and became its leader. He wrote commentaries on Aristotle and ...

, Syrianus

Syrianus (, ''Syrianos''; died c. 437 A.D.) was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, and head of Plato's Academy in Athens, succeeding his teacher Plutarch of Athens in 431/432 A.D. He is important as the teacher of Proclus, and, like Plutarch an ...

and Proclus

Proclus Lycius (; 8 February 412 – 17 April 485), called Proclus the Successor (, ''Próklos ho Diádokhos''), was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophers of late antiquity. He set forth one of th ...

.

''Phaedo'' was the literary model of Saint Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen ( or Γρηγόριος Νυσσηνός; c. 335 – c. 394), was an early Roman Christian prelate who served as Bishop of Nyssa from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death in 394. He is ve ...

's ''Dialogue on the Soul and Resurrection

Resurrection or anastasis is the concept of coming back to life after death. Reincarnation is a similar process hypothesized by other religions involving the same person or deity returning to another body. The disappearance of a body is anothe ...

''(''(peri psyches kai anastaseos)''), which he dedicated to the memory of his sister Saint Macrina the Younger

Macrina the Younger (; c. 327 – 19 July 379) was an early Christian consecrated virgin and deaconess. Macrina was elder sister of Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, Naucratius and Peter of Sebaste. Gregory of Nyssa wrote a work entitled ''Li ...

.

The two most important commentaries on the '' Phaedo'' that have come down to us from the ancient world are those by Olympiodorus of Alexandria and Damascius

Damascius (; ; 462 – after 538), known as "the last of the Athenian Neoplatonists", was the last scholarch of the neoplatonic Athenian school. He was one of the neoplatonic philosophers who left Athens after laws confirmed by emperor Jus ...

of Athens.

The ''Phaedo'' was first translated into Latin from Greek by Apuleius

Apuleius ( ), also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis (c. 124 – after 170), was a Numidians, Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He was born in the Roman Empire, Roman Numidia (Roman province), province ...

Fletcher R., ''Platonizing Latin: Apuleius’s Phaedo'' in G. Williams and K. Volk, eds.,''Roman Reflections: Studies in Latin Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 238–259 but no copy survived, so Henry Aristippus

Henry Aristippus of Calabria (born in Santa Severina in 1105–10; died in Palermo in 1162), sometimes known as Enericus or Henricus Aristippus, was a religious scholar and the archdeacon of Catania (from c. 1155) and later chief '' familiaris'' ...

produced a new translation in 1160.

The ''Phaedo'' has come to be considered a seminal formulation, from which "a whole range of dualities, which have become deeply ingrained in Western philosophy, theology, and psychology over two millennia, received their classic formulation: soul and body, mind and matter, intellect and sense, reason and emotion, reality and appearance, unity and plurality, perfection and imperfection, immortal and mortal, permanence and change, eternal and temporal, divine and human, heaven and earth."

Texts and translations

Original texts

*Greek text aPerseus

*Plato. ''Opera'', volume I. Oxford Classical Texts. *Plato. ''Phaedo''. Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics. Greek text with introduction and commentary by C. J. Rowe. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Original texts with translation

*''Plato: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo, Phaedrus.'' Greek with translation by Harold N. Fowler. Loeb Classical Library 36. Harvard Univ. Press (originally published 1914). ** Fowler translation aPerseus

*''Plato: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo.'' Greek with translation by Chris Emlyn-Jones and William Preddy. Loeb Classical Library 36. Harvard Univ. Press, 2017.

HUP listing

h2>

Translations

*''The Last Days of Socrates'', translation of Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo. Hugh Tredennick, 1954. . Made intoBBC radio play

in 1986. *''Plato: Phaedo.'' Hackett Classics, 2nd edition. Hackett Publishing Company, 1977. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. *Plato. ''Complete Works.'' Hackett, 1997. Translated by G. M. A. Grube. *''Plato: Meno and Phaedo.'' Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy. By David Sedley (Editor) and Alex Long (Translator). Cambridge University Press, 2010.

See also

* Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 229 *Rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the Epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to ot ...

* Allegory of the Cave

Notes

References

* * * *Further reading

* Bobonich, Christopher. 2002. "Philosophers and Non-Philosophers in the Phaedo and the Republic." In ''Plato's Utopia Recast: His Later Ethics and Politics'', 1–88. Oxford: Clarendon. * Brill, Sara. 2013. ''Plato on the Limits of Human Life''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. * Dorter, Kenneth. 1982. ''Plato's Phaedo: An Interpretation''. Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press. * Frede, Dorothea. 1978. "The Final Proof of the Immortality of the Soul in Plato's Phaedo 102a–107a". ''Phronesis'', 23.1: 27–41. * Futter, D. 2014. "The Myth of Theseus in Plato's Phaedo". ''Akroterion'', 59: 88–104. * Gosling, J. C. B., and C. C. W. Taylor. 1982. "Phaedo" n''The Greeks on Pleasure'', 83–95. Oxford, UK: Clarendon. * Holmes, Daniel. 2008. "Practicing Death in Petronius' Cena Trimalchionis and Plato's Phaedo". ''Classical Journal'', 104(1): 43–57. * Irwin, Terence. 1999. "The Theory of Forms". n''Plato 1: Metaphysics and Epistemology'', 143–170. Edited by Gail Fine. Oxford Readings in Philosophy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. * Long, Anthony A. 2005. “Platonic Souls as Persons.” In ''Metaphysics, Soul, and Ethics in Ancient Thought: Themes from the Work of Richard Sorabji'', edited by R. Salles, 173–191. Oxford: Oxford University Press. * Most, Glenn W. 1993. "A Cock for Asclepius". ''Classical Quarterly'', 43(1): 96–111. * Nakagawa, Sumio. 2000. "Recollection and Forms in Plato's Phaedo." ''Hermathena'', 169: 57–68. * * Sedley, David. 1995. "The Dramatis Personae of Plato's Phaedo." n''Philosophical Dialogues: Plato, Hume, and Wittgenstein'', 3–26 Edited by Timothy J. Smiley. Proceedings of the British Academy 85. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. *External links

* * * *Approaching Plato: A Guide to the Early and Middle Dialogues

a beginner's guide

* * ;Online versions *

Benjamin Jowett

Benjamin Jowett (, modern variant ; 15 April 1817 – 1 October 1893) was an English writer and classical scholar. Additionally, he was an administrative reformer in the University of Oxford, theologian, Anglican cleric, and translator of Plato ...

, 1892full text

* George Theodoridis, 2016

full text

{{Authority control Afterlife Dialogues of Plato Works about philosophy of death he:פאידון