Peter Heywood on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Bounty's'' mission was to collect

''Bounty's'' mission was to collect

''Bounty'' sailed from Cape Town on 1 July 1788, reached

''Bounty'' sailed from Cape Town on 1 July 1788, reached

For three weeks, ''Bounty'' sailed westward, and early on 28 April 1789 was lying off the island of

For three weeks, ''Bounty'' sailed westward, and early on 28 April 1789 was lying off the island of  Members of the crew would later provide conflicting accounts of Heywood's actions during the mutiny.

Members of the crew would later provide conflicting accounts of Heywood's actions during the mutiny.

''Pandora'' left Tahiti on 8 May 1791 to search for Christian and the ''Bounty'' among the thousands of southern Pacific islands. Apart from a few spars—which had probably floated from Tubuai—discovered at Palmerston Island (Avarau), no traces of the ship could be found.Alexander, pp. 15–18. Physical attacks from natives were frequent; early in August Edwards abandoned the search and headed for the Dutch East Indies via the Torres Strait. Knowledge of these waters and the surrounding reefs was minimal; on 29 August 1791, the ship ran aground on the outer

''Pandora'' left Tahiti on 8 May 1791 to search for Christian and the ''Bounty'' among the thousands of southern Pacific islands. Apart from a few spars—which had probably floated from Tubuai—discovered at Palmerston Island (Avarau), no traces of the ship could be found.Alexander, pp. 15–18. Physical attacks from natives were frequent; early in August Edwards abandoned the search and headed for the Dutch East Indies via the Torres Strait. Knowledge of these waters and the surrounding reefs was minimal; on 29 August 1791, the ship ran aground on the outer

The court martial opened on 12 September 1792 aboard in Portsmouth Harbour. Accused with Heywood were Joseph Coleman, Thomas McIntosh and Charles Norman, all of whom had been exonerated in Bligh's account and could confidently expect acquittal, as could Michael Byrne, the nearly blind ship's fiddler. The other accused were James Morrison, Thomas Burkitt,

The court martial opened on 12 September 1792 aboard in Portsmouth Harbour. Accused with Heywood were Joseph Coleman, Thomas McIntosh and Charles Norman, all of whom had been exonerated in Bligh's account and could confidently expect acquittal, as could Michael Byrne, the nearly blind ship's fiddler. The other accused were James Morrison, Thomas Burkitt,

Heywood served on ''Queen Charlotte'' until March 1795, and was aboard her when the French fleet was defeated at

Heywood served on ''Queen Charlotte'' until March 1795, and was aboard her when the French fleet was defeated at

On 16 July 1816, ''Montagu'' was paid off in Chatham and Heywood finally retired from the sea. Two weeks later he married Frances Joliffe, a widow whom he had met ten years earlier, and settled with her at

On 16 July 1816, ''Montagu'' was paid off in Chatham and Heywood finally retired from the sea. Two weeks later he married Frances Joliffe, a widow whom he had met ten years earlier, and settled with her at

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

Peter Heywood (6 June 1772 – 10 February 1831) was a British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

officer who was on board during the mutiny of 28 April 1789. He was later captured in Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

, tried and condemned to death as a mutineer, but subsequently pardoned. He resumed his naval career and eventually retired with the rank of post-captain

Post-captain or post captain is an obsolete alternative form of the rank of captain in the Royal Navy. The term "post-captain" was descriptive only; it was never used as a title in the form "Post-Captain John Smith".

The term served to dis ...

, after 29 years of honourable service.

The son of a prominent Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

family with strong naval connections, Heywood joined ''Bounty'' under Lieutenant William Bligh

William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was a Vice-admiral (Royal Navy), Royal Navy vice-admiral and colonial administrator who served as the governor of New South Wales from 1806 to 1808. He is best known for his role in the Muti ...

at the age of 15. Although unranked, he was granted the privileges of a junior officer. ''Bounty'' left England in 1787 on a mission to collect and transport breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to have been selectively bred in Polynesia from the breadnut ('' Artocarpus camansi''). Breadfruit was spread into ...

from the Pacific, and arrived in Tahiti late in 1788. Relations between Bligh and certain of his officers, notably Fletcher Christian

Fletcher Christian (25 September 1764 – 20 September 1793) was an English sailor who led the mutiny on the ''Bounty'' in 1789, during which he seized command of the Royal Navy vessel from Lieutenant William Bligh.

In 1787, Christian was ap ...

, became strained, and worsened during the five months that ''Bounty'' remained in Tahiti.

Shortly after the ship began its homeward voyage, Christian and his discontented followers seized Bligh and took control of the vessel. Bligh and 18 loyalists were set adrift in an open boat; Heywood was among those who remained with ''Bounty''. Later, he and 15 others left the ship and settled in Tahiti, while ''Bounty'' sailed on, ending its voyage at Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, in the southern Pacific Ocean, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff ...

. Bligh, after an epic open-boat journey, eventually reached England, where he implicated Heywood as one of the mutiny's prime instigators. In 1791, Heywood and his companions were met in Tahiti by the search vessel . Heywood and one other sailor welcomed the ''Pandora'' in canoes, relieved to be rescued. However, they were arrested; the captain, Edward Edwards, had them and 12 others fettered and handcuffed in an box built for the purpose on deck. During their subsequent journey, ''Pandora'' was wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system, composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

, and four of Heywood's fellow prisoners drowned.

In September 1792, Heywood was court-martialed and with five others was sentenced to hang. However, the court recommended mercy for Heywood, and King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

pardoned him. In a rapid change of fortune, he found himself favoured by senior officers, and after the resumption of his career, received a series of promotions that gave him his first command at the age of 27 and made him a post-captain at 31. He remained in the navy until 1816, building a respectable career as a hydrographer, and then enjoyed a long and peaceful retirement.

The extent of Heywood's true guilt in the mutiny has been clouded by contradictory statements and possible false testimony. During his trial powerful family connections worked on his behalf, and he later benefited from the Christian family's generally fruitful efforts to demean Bligh's character and present the mutiny as an understandable reaction to an unbearable tyranny. Contemporary press reports and more recent commentators have contrasted Heywood's pardon with the fate of his fellow prisoners who were hanged, all lower-deck sailors without wealth or family influence and who lacked legal counsel.

Family background and early life

Peter Heywood was born in 1772 at the Nunnery, in Douglas,Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

. He was the fifth of the 11 children (six boys and five girls) of Peter John Heywood and his wife Elizabeth Spedding. The Heywood ancestry can be traced back to the 12th century; a prominent forebear was Peter "Powderplot" Heywood, who arrested Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes (; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial English Catholics involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was born and educate ...

after the 1605 plot to blow up the English parliament.Alexander, pp. 64–65. On his mother's side, Peter was distantly related to Fletcher Christian

Fletcher Christian (25 September 1764 – 20 September 1793) was an English sailor who led the mutiny on the ''Bounty'' in 1789, during which he seized command of the Royal Navy vessel from Lieutenant William Bligh.

In 1787, Christian was ap ...

's family, which had been established on the Isle of Man for centuries. In 1773, when Peter was a year old, Peter John Heywood was forced by a financial crisis to sell The Nunnery and leave the island. The family lived for several years in Whitehaven

Whitehaven is a town and civil parish in the Cumberland (unitary authority), Cumberland district of Cumbria, England. It is a port on the north-west coast, and lies outside the Lake District National parks of England and Wales, National Park. ...

, England before the father's appointment as agent for the Duke of Atholl's Manx properties brought them back to Douglas.

Heywood's family had a tradition of naval and military service. In 1786, at the age of 14, Heywood left St Bees School

St Bees School is a co-educational fee-charging school, located in the West Cumbrian village of St Bees, England.

In 1583, it was founded by Edmund Grindal, the Archbishop of Canterbury, as a free grammar school for boys. The school remain ...

in England to join , a harbour-bound training vessel at Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

. In August 1787, Heywood was offered a berth on the ''Bounty'' for an extended cruise to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

under the command of Lieutenant William Bligh. Heywood's recommendation came from Richard Betham, a family friend who was also Bligh's father-in-law. The Heywood family at this time was in deep financial trouble, Peter John Heywood having been dismissed by the Duke for gross mismanagement and embezzlement of funds. Betham wrote to Bligh: "his Family have fallen into a great deal of Distress on account of their father losing the Duke of Atholl's business", and urged Bligh not to desert them in their adversity. Bligh was happy to oblige his father-in-law, and invited the young Heywood to stay with him in Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, in the Royal Borough of Greenwich and London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a Ford (crossing), ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century ...

while the ship was prepared for the forthcoming voyage.

On HMS ''Bounty''

Outward journey

''Bounty's'' mission was to collect

''Bounty's'' mission was to collect breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to have been selectively bred in Polynesia from the breadnut ('' Artocarpus camansi''). Breadfruit was spread into ...

plants from Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

for transportation to the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

as a new source of food for the slave plantations. Bligh, a skilled navigator, had travelled to Tahiti in 1776, as Captain James Cook

Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 1768 and 1779. He complet ...

's sailing master

The master, or sailing master, is a historical rank for a naval Officer (armed forces), officer trained in and responsible for the navigation of a sailing ship, sailing vessel.

In the Royal Navy, the master was originally a warrant officer who ...

during the explorer's final voyage. ''Bounty'' was a small vessel, in overall length, with a complement of 46 men crammed into limited accommodation. Heywood was one of several " young gentlemen" aboard ship who were mustered as able seamen but ate and slept with their social equals in the cockpit

A cockpit or flight deck is the area, on the front part of an aircraft, spacecraft, or submersible, from which a pilot controls the vehicle.

The cockpit of an aircraft contains flight instruments on an instrument panel, and the controls th ...

.Alexander, pp. 44–46. His distant kinsman, Fletcher Christian, served as master's mate

Master's mate is an obsolete rating which was used by the British Royal Navy, Royal Navy, United States Navy and merchant services in both countries for a senior petty officer who assisted the sailing master, master. Master's mates evolved into th ...

on the voyage. Bligh's orders were to enter the Pacific by rounding Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

. After collecting sufficient breadfruit plants from the Tahitian islands he was to sail westward, through the Endeavour Strait and across the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

. Entering the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

he would continue on to the West Indies, incidentally completing a circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first circumnaviga ...

.Bligh, Ch. 1.

''Bounty'' left London on 15 October 1787, and after being held at Spithead

Spithead is an eastern area of the Solent and a roadstead for vessels off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast, with the Isle of Wight lying to the south-west. Spithead and the ch ...

awaiting final sailing orders was further delayed by bad weather; it was 23 December before the ship was finally away. This long hiatus caused ''Bounty'' to arrive at Cape Horn much later in the season than planned and to encounter very severe weather. Unable to make progress against westerly gales and enormous seas, Bligh finally turned the ship and headed east. He would now have to take the alternative, much longer route to the Pacific, sailing first to Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

and then south of Australia and New Zealand, before working northwards to Tahiti.

Following its new route, ''Bounty'' reached Cape Town on 24 May 1788. Here, Heywood wrote a long letter to his family describing the voyage to date, with vivid descriptions of life at sea. Initially, Heywood relates, sailing had been "in the most pleasurable weather imaginable". In describing the attempts to round Cape Horn he writes: "I suppose there never were seas, in any part of the known world, to compare with those we met ... for height, and length of swell; the oldest seamen on board never saw anything to equal that ..." Bligh's decision to turn east was, Heywood records, "to the great joy of everyone on board". Historian Greg Dening records a story, unmentioned in Heywood's letter, that at the height of the Cape Horn storms Bligh had punished Heywood for some minor wrongdoing by ordering him to climb the mast and to "stay there beyond the point of all endurance"; this, Dening concedes, was possibly a later fabrication to discredit Bligh.

In Tahiti

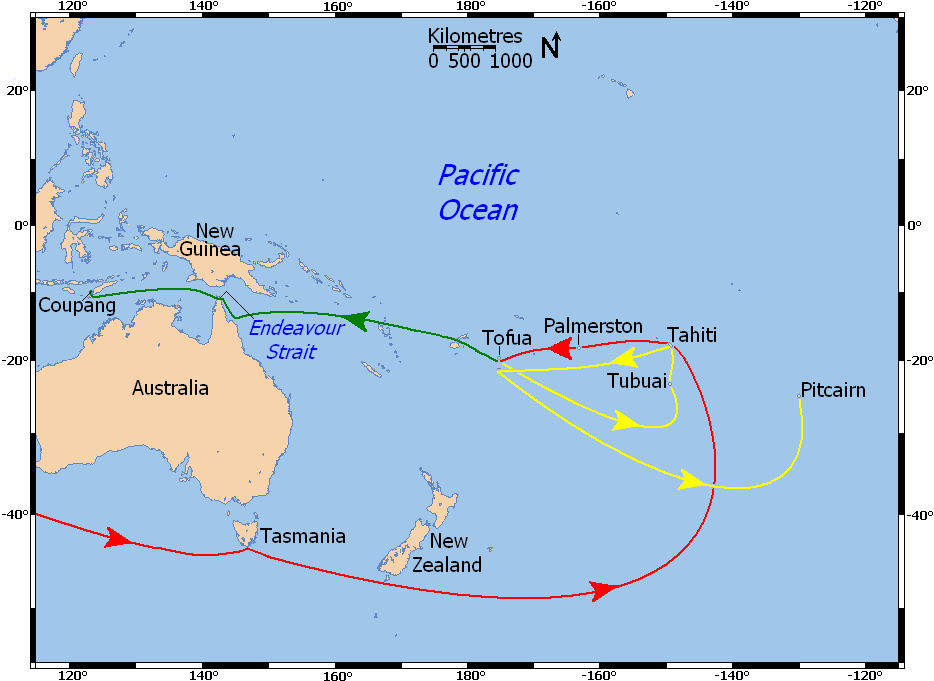

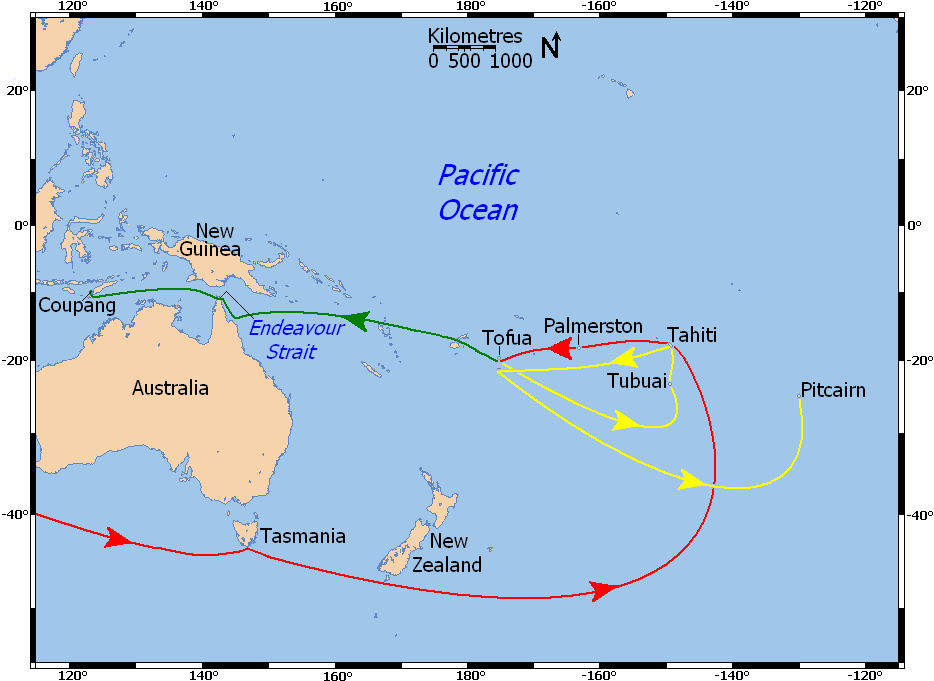

''Bounty'' sailed from Cape Town on 1 July 1788, reached

''Bounty'' sailed from Cape Town on 1 July 1788, reached Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

on 19 August, and arrived at Matavai Bay Matavai Bay is a bay on the north coast of Tahiti, the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia. It is in the commune of Mahina, approximately 8 km east of the capital Pape'ete.

Early European voyages

The bay was visited by E ...

, Tahiti, on 26 October. The latter stages of this voyage, however, saw signs of trouble between Bligh and his officers and crew; rows and disagreements grew steadily more frequent. On arrival, Heywood and Christian were assigned to a shore camp which would act as a nursery for the breadfruit plants. They would live here throughout the Tahiti sojourn, a "situation of comfort and privilege" which, according to historian Richard Hough, was much envied by those required to spend their nights on the ship. Whether crew were ashore or on board, however, duties during ''Bounty's'' five months' stay in Tahiti were relatively light. Some men took regular partners from the native women, while others led promiscuous lives; both Christian and Heywood are listed among the officers and men treated for venereal infections.Hough, pp. 122–25.

Despite the relaxed atmosphere, relations between Bligh and his men, and particularly between Bligh and Christian, continued to deteriorate. Christian was routinely humiliated by the captain—often in front of the crew and the native Tahitians—for real or imagined slackness, while severe punishments were handed out to men whose carelessness had led to the loss or theft of equipment.Alexander, pp. 115–20. Flogging

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed ...

s, rarely administered during the outward voyage, now became a common occurrence; as a consequence, three men deserted the ship. They were quickly recaptured, and a search of their belongings revealed a list of names which included those of Christian and Heywood. Bligh confronted the pair and accused them of complicity in the desertion plot, which they strenuously denied; without further corroboration, Bligh could not act against them.

As the date for departure from Tahiti grew closer, Bligh's outbursts against his officers became more frequent.Alexander, pp. 124–25. One witness reported that "Whatever fault was found, Mr Christian was sure to bear the brunt." Tensions rose among the men, who faced the prospect of a long and dangerous voyage that would take them through the uncharted Endeavour Strait, followed by many months of hard sailing. Bligh was impatient to be away, but in Hough's words he "failed to anticipate how his company would react to the severity and austerity of life at sea ... after five dissolute, hedonistic months at Tahiti". On 5 April 1789, ''Bounty'' finally weighed anchor and made for the open sea.

Mutiny

Seizure of ''Bounty''

For three weeks, ''Bounty'' sailed westward, and early on 28 April 1789 was lying off the island of

For three weeks, ''Bounty'' sailed westward, and early on 28 April 1789 was lying off the island of Tofua

Tofua is a volcanic island in Tonga. Located in the Haʻapai island group, it is a steep-sided composite cone with a summit caldera. It is part of the highly active Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone and its associated volcanic arc, which extends ...

in the Friendly Islands (Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

). Christian was officer of the watch; Bligh's behaviour towards him had grown increasingly hostile, and Christian was now prepared to take over the ship, with the help of a group of armed seamen who were willing to follow him. Shortly after 5:15 am local time, Bligh was seized and brought on deck, naked from the waist down, wearing only his nightshirt, and with his hands bound. There followed hours of confusion as the majority of the crew sought to grasp the situation and decide how they should react. Finally, at about 10 am, Bligh and 18 loyalists were placed in the ship's launch, a open boat, with minimal supplies and navigation instruments, and cast adrift. Heywood was among those who remained on board.

Not all the 25 men who remained on ''Bounty'' were mutineers; Bligh's launch was overloaded, and some who stayed with the ship did so under duress. "Never fear, lads, I'll do you justice if ever I reach England", Bligh is reported as saying. With regard to Heywood, however, Bligh was convinced that the young man was as guilty as Christian. Bligh's first detailed comments on the mutiny are in a letter to his wife Betsy, in which he names Heywood (a mere boy not yet 17) as "one of the ringleaders", adding: "I have now reason to curse the day I ever knew a Christian or a Heywood or indeed a Manks man. Bligh's later official account to the Admiralty lists Heywood with Christian, Edward Young

Edward Young ( – 5 April 1765) was an English poet, best remembered for ''Night-Thoughts'', a series of philosophical writings in blank verse, reflecting his state of mind following several bereavements. It was one of the most popular poem ...

and George Stewart as the mutiny's leaders, describing Heywood as a young man of abilities for whom he had felt a particular regard. To the Heywood family Bligh wrote: "His baseness is beyond all description." Stewart was never able to refute Bligh charge of mutiny as he drowned when the Pandora sank in 1791; Edward Young actually slept through the mutiny although ironically enough he chose to be with the mutineers ex post facto.

Members of the crew would later provide conflicting accounts of Heywood's actions during the mutiny.

Members of the crew would later provide conflicting accounts of Heywood's actions during the mutiny. Boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, or the third hand on a fishing vessel, is the most senior Naval rating, rate of the deck department and is responsible for the ...

William Cole testified that Heywood had been detained on the ship against his will.Hough, p. 279. Ship's carpenter William Purcell thought that Heywood's ambiguous behaviour during the critical hours—he had been seen unwittingly resting his hand on top of a cutlass

A cutlass is a short, broad sabre or slashing sword with a straight or slightly curved blade sharpened on the cutting edge and a hilt often featuring a solid cupped or basket-shaped guard. It was a common naval weapon during the early Age of ...

—was due to his youth and the excitement of the moment, and that he had no hand in the uprising itself.Alexander, pp. 244–46. On the other hand, Midshipman John Hallett claimed that Bligh, with a bayonet at his breast and his hands tied, had addressed a remark to Heywood who had "laughed, turned round and walked away". Yet Bligh himself although convived Heyward was a mutiny's leaders never mentioned in his official account of Heywood laughing in his face. Another midshipman, Thomas Hayward, claimed he had asked Heywood his intentions and been told by the latter that he would remain with the ship, from which Hayward assumed that his messmate had sided with the mutineers.

After the departure of Bligh's launch, Christian turned ''Bounty'' eastward in search of a remote haven on which he and the mutineers could settle. He had in mind the island of Tubuai

Tupuai ( ) is the main island of the Austral Island group, located south of Tahiti. In addition to Tubuai, the group of islands include Rimatara, Rurutu, Raivavae, Rapa and the uninhabited Îles Maria. They are part of the Austral Islands ...

, south of Tahiti, partly mapped by Cook. Christian intended to pick up women, male servants and livestock from Tahiti, to help establish the settlement. As ''Bounty'' sailed slowly towards Tubuai, Bligh's launch, overcoming many dangers and hardships, made its way steadily towards civilisation and reached Coupang

Coupang, Inc. () is a US-based technology company headquartered in Seattle, Seattle, Washington and incorporated under the Delaware General Corporation Law. Founded in 2010 by Bom Kim, the company operates a retail business, food delivery se ...

(now Kupang), on Timor

Timor (, , ) is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is Indonesia–Timor-Leste border, divided between the sovereign states of Timor-Leste in the eastern part and Indonesia in the ...

, on 14 June 1789. Here Bligh gave his first report of the mutiny, while awaiting a ship to take him back to England.Alexander, pp. 152–56.

Fugitive

A month's sailing brought ''Bounty'' to Tubuai on 28 May 1789. Despite a hostile reception from the island's natives Christian spent several days surveying the land and selecting a site for a fort before taking ''Bounty'' on to Tahiti. When they reached Matavai Bay Christian concocted a story that he, Bligh and Captain Cook were founding a new settlement atAitutaki

Aitutaki, also traditionally known as Araura and Utataki, is the second most-populated island in the Cook Islands, after Rarotonga. It is an "almost atoll", with fifteen islets in a lagoon adjacent to the main island. Total land area is , and the ...

. Cook's name ensured generous gifts of livestock and other goods, and on 16 June the well-provisioned ''Bounty'' sailed back to Tubuai with nearly 30 Tahitians, some of whom had been taken aboard by deception. The attempt to establish a colony on Tubuai was unsuccessful; the repeated raids by the mutineers for "wives" and the near-mutinous dissatisfaction of the duped Tahitians wrecked Christian's plans.

On 18 September 1789, ''Bounty'' sailed back to Matavai Bay for the final time. Heywood and 15 others now decided that they would remain in Tahiti and risk the consequences of discovery, while Christian, with eight mutineers and many Tahitian men and women, took off in ''Bounty'' for an unrevealed destination. Before departing, Christian left messages for his family with Heywood, recounting the story of the mutiny and emphasising that he alone was responsible.

On Tahiti, Heywood and his companions set about organising their lives. The largest group, led by James Morrison, began building a schooner, to be named ''Resolution'' after Cook's ship. Matthew Thompson and former master-at-arms Charles Churchill chose to lead drunken and generally dissolute lives which ended in the violent deaths of both.Hough, pp. 219–22. Heywood preferred quiet domesticity in a small house with a Tahitian wife, studying the Tahitian language and fathering a daughter. Over a period of 18 months (from September 1789 through 1790 to March 1791), he gradually adopted native manners of dress, and was heavily tattooed around the body. Heywood later explained: "I was tattooed not to gratify my own desires, but theirs", adding that in Tahiti a man without tattoos was an outcast. "I always made it a maxim when I was in Rome to act as Rome did."Tagart, pp. 81–84 (letter from Heywood to his mother, 15 August 1792).

What Dening describes as an "arcadian existence" ended on 23 March 1791, with the arrival of the search ship . Heywood's first reaction to the ship's appearance was, he later wrote, "the utmost joy". As the ship anchored, he rode out in a canoe to identify himself. However, his reception, like that of the others who came aboard voluntarily, was frosty. Captain Edward Edwards, ''Pandora's'' commander, made no distinctions among the former ''Bounty'' men; all became prisoners, and were manacled and taken below.

Prisoner

''Pandora'' voyage

Within a few days, all of the 14 surviving fugitives in Tahiti had surrendered or been captured. Among ''Pandora's'' officers was former ''Bounty'' midshipman Thomas Hayward. Heywood's hopes that his former shipmate would verify his innocence were quickly dashed. Hayward, "... like all worldlings raised a little in life, received us very coolly, and pretended ignorance of our affairs." ''Pandora'' remained at Tahiti for five weeks while Captain Edwards tried without success to obtain information on ''Bounty's'' whereabouts. A cell was built on ''Pandora's'' quarterdeck, a structure known as "Pandora's Box" where the prisoners, legs in irons and wrists in handcuffs, were to be confined for almost five months. Heywood wrote: "The heat ... was so intense that the sweat frequently ran in streams to the scuppers, and produced maggots in a short time ... and the two necessary tubs which were constantly kept in place helped to render our situation truly disagreeable." ''Pandora'' left Tahiti on 8 May 1791 to search for Christian and the ''Bounty'' among the thousands of southern Pacific islands. Apart from a few spars—which had probably floated from Tubuai—discovered at Palmerston Island (Avarau), no traces of the ship could be found.Alexander, pp. 15–18. Physical attacks from natives were frequent; early in August Edwards abandoned the search and headed for the Dutch East Indies via the Torres Strait. Knowledge of these waters and the surrounding reefs was minimal; on 29 August 1791, the ship ran aground on the outer

''Pandora'' left Tahiti on 8 May 1791 to search for Christian and the ''Bounty'' among the thousands of southern Pacific islands. Apart from a few spars—which had probably floated from Tubuai—discovered at Palmerston Island (Avarau), no traces of the ship could be found.Alexander, pp. 15–18. Physical attacks from natives were frequent; early in August Edwards abandoned the search and headed for the Dutch East Indies via the Torres Strait. Knowledge of these waters and the surrounding reefs was minimal; on 29 August 1791, the ship ran aground on the outer Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system, composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

and began to fill with water. Three of the prisoners in "Pandora's Box" were let out and ordered to assist the crew at the pumps. In the subsequent struggle to save the ship, the rest of the men in "Pandora's Box" were ignored as the regular crew went about their efforts to prevent the ship from foundering. At dawn it was clear that their efforts were in vain; the officers agreed that the vessel could not be saved and orders were then given to abandon ship. The armourer was ordered into the "box" to knock off the remaining prisoners' leg irons and shackles; however, the ship sank before he had finished. Heywood, stripped naked, was one of the last to get out of the cell; four prisoners, including Heywood's best friend George Stewart, were drowned, as were 31 of the regular crew. The 99 survivors, including ten prisoners, recovered on a nearby island where they stayed for two nights before embarking on an open-boat journey which largely followed Bligh's course of two years earlier. The prisoners were mostly kept bound hand and foot on the slow passage to Coupang, which they reached on 17 September 1791.Hough, pp. 227–30.

Throughout this long ordeal Heywood somehow managed to hang on to his prayer book, and used it to jot down details of dates, places and events during his captivity.Alexander, p. 35. He recorded that at Coupang he and his fellow-prisoners were placed in the stocks

Stocks are feet and hand restraining devices that were used as a form of corporal punishment and public humiliation. The use of stocks is seen as early as Ancient Greece, where they are described as being in use in Solon's law code. The law de ...

and confined in the fortress before being sent to Batavia (now Jakarta) on the first leg of the voyage back to England. During a seven-week stay in Batavia confined aboard a Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

ship, most of the prisoners, including Heywood, were allowed on deck only twice. On 25 December 1791 they were taken aboard a Dutch ship, ''Vreedenberg'', for passage to Europe via Cape Town. Still in the charge of Captain Edwards, the prisoners were kept in irons for most of the way. At the Cape they were eventually transferred to a British warship, , which set sail for England on 5 April 1792. On 19 June the ship arrived in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

where the prisoners were moved to the guardship .

Portsmouth

Bligh had landed in England on 14 March 1790 to public acclaim, and was quickly promoted to post-captain. In the following months he wrote his account of the mutiny, and on 22 October was honourably acquitted atcourt martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the mili ...

of responsibility for the ''Bounty's'' loss. Early in 1791 he was appointed to command a new breadfruit expedition, which left London on 3 August of that year, before any news of the capture of Heywood and the others had reached London. Bligh would be gone for more than two years, and would thus be absent from the court martial proceedings that awaited the returned mutineers.

Following Heywood's arrival in Portsmouth his family sought help from their wide circle of influential friends, and set out to secure the best available legal counsel. Most active on Heywood's behalf was his older sister Hester ("Nessy"), who gave her brother unqualified support, writing to him on 3 June: "If the transactions of that day were as Mr. Bligh represented them, such is my conviction of your worth and honor that I will without hesitation stake my life on your innocence. If on the contrary you were concerned in such a conspiracy against your commander, I shall be firmly convinced that his conduct was the occasion of it." Heywood sent his personal narrative of the mutiny to the Earl of Chatham

Earl of Chatham, of Chatham in the County of Kent, was a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1766 for William Pitt the Elder on his appointment as Lord Privy Seal, along with the subsidiary title of Viscount Pitt, of Burton ...

, who was First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

and brother to the prime minister, William Pitt. This was a step Heywood subsequently regretted; he had not consulted his lawyers, and his narrative contained statements that Heywood later rescinded on the grounds that they were "the errors of an imperfect recollection". On 8 June Nessy was advised by her and Heywood's uncle, Captain Thomas Pasley, that on the basis of information from the returned ''Pandora'' crew "...your brother appears by all account to be the greatest culprit of all, Christian alone excepted ... I have no hope of his not being condemned." Later, however, Pasley was able to offer some comfort; Captain George Montagu of ''Hector'', where Heywood was held, was Pasley's "particular friend". By chance another Heywood naval relative by marriage, Captain Albemarle Bertie, was in Portsmouth Harbour with his ship , moored alongside ''Hector''. Mrs Bertie and ''Edgar's'' officers were frequent visitors to Heywood, bringing gifts of food, clothing and other comforts.

Pasley secured the services of Aaron Graham, an experienced and clever advocate, to direct Heywood's legal strategy. Between June and September Heywood and his sister exchanged a stream of letters and ardent poems; Nessy's final letter, just before the court martial, exhorted: "May the Almighty Providence, whose tender care has hitherto preserved you, be still your bountiful Protector! May he instil into the hearts of your judges every sentiment of justice, generosity and compassion ... and may you at length be restored to us."

Court martial

The court martial opened on 12 September 1792 aboard in Portsmouth Harbour. Accused with Heywood were Joseph Coleman, Thomas McIntosh and Charles Norman, all of whom had been exonerated in Bligh's account and could confidently expect acquittal, as could Michael Byrne, the nearly blind ship's fiddler. The other accused were James Morrison, Thomas Burkitt,

The court martial opened on 12 September 1792 aboard in Portsmouth Harbour. Accused with Heywood were Joseph Coleman, Thomas McIntosh and Charles Norman, all of whom had been exonerated in Bligh's account and could confidently expect acquittal, as could Michael Byrne, the nearly blind ship's fiddler. The other accused were James Morrison, Thomas Burkitt, Thomas Ellison

Thomas Rangiwahia Ellison (11 November 1867 – 2 October 1904), also known as Tamati Erihana, was a New Zealand rugby union player and lawyer. He led the first New Zealand national rugby union team, New Zealand representative rugby team o ...

, John Millward and William Muspratt. The court martial board was presided over by Lord Hood, naval commander-in-chief at Portsmouth, and included Pasley's friend George Montagu and Heywood's relative by marriage, Albemarle Bertie.

The testimonies of the boatswain Cole, the carpenter Purcell, and the sailing master John Fryer were not unfavourable towards Heywood. However, Thomas Hayward's declared belief that Heywood was with the mutineers was damaging, as was the evidence of John Hallett concerning Heywood's alleged insolence in laughing and turning away from the captive Bligh—though Hallett had previously written to Nessy Heywood professing total ignorance of the part Heywood had played in the mutiny.

Heywood opened his defence on 17 September 1792 with a long prepared statement read by one of his lawyers. It began with a frank acknowledgement of his predicament: to be even accused of mutiny was to "appear at once the object of unpardonable guilt and exemplary vengeance". His case rested on a series of arguments which, as historian Caroline Alexander points out, are not wholly consistent. First, Heywood pleaded his "extreme youth and inexperience" as the cause of his failure to join Bligh and the loyalists in the open boat, insisting that "...I was influenced in my Conduct by the Example of my Messmates, Mr. Hallet and Mr. Hayward ... the latter, tho' he had been many years at Sea, yet, when Christian ordered him into the Boat he was ... so much overcome by the harsh Command, that he actually shed tears." Heywood then cited a different reason for staying aboard ''Bounty'': Bligh's launch was overloaded, and its destruction would be assured "by the least addition to their Number". Finally, Heywood maintained he had intended to join Bligh but had been stopped: "...on hearing it suggested that I should be deem'd Guilty if I staid in the Ship, I went down directly, and in passing Mr. Cole told him in a low tone of voice that I would fetch a few necessaries in a Bag and follow him into the Boat, which at that time I meant to do but was afterwards prevented."

Under further questioning, Cole confirmed his belief that Heywood had been detained against his will. William Peckover, ''Bounty's'' gunnery officer, affirmed that if he had stayed aboard the ship in the hope of retaking her, he would have looked to Heywood for assistance. Witnesses from the ''Pandora'' attested that Heywood had surrendered himself voluntarily, and that he had been fully cooperative in providing information. On the issue of his alleged laughing at Bligh's predicament, Heywood managed to cast doubts on Hallett's testimony, asking how Hallett had managed "to particularise the muscles of a man's countenance" at some distance and during the hurly-burly of a mutiny. Heywood concluded his defence with what Alexander terms an "audacious" assertion that had Bligh been present in court he would have "exculpated me from the least disrespect".

Verdict and sentences

On 18 September 1792, Lord Hood announced the court's verdicts. As expected, Coleman, McIntosh, Norman, and Byrne were acquitted. Heywood and the other five were found guilty of the charge of mutiny, and were ordered to suffer death by hanging. Lord Hood added: "In consideration of various circumstances, the court did humbly and most earnestly recommend the said Peter Heywood and James Morrison to His Majesty's Royal Mercy." Heywood's family were quickly reassured by the lawyer Aaron Graham that the young man's life was safe and that he would soon be free.Alexander, pp. 284–94. As the weeks passed, Heywood calmly occupied himself by resuming his studies of the Tahitian language. Meanwhile the family—Nessy in particular—busied itself on his behalf, and another plea was made to the Earl of Chatham, in heart-rending terms. Shortly afterwards came the first indication that a royal pardon was in the offing, and on 26 October 1792, on ''Hector's'' quarterdeck, this was formally read to Heywood and Morrison by Captain Montagu. Heywood responded with a short statement that ended: "I receive with gratitude my Sovereign's mercy, for which my future life will be faithfully devoted to his service." According to a Dutch newspaper which reported the case, his contrition was accompanied by a "flood of tears". William Muspratt, the only other of the accused to employ legal counsel, was reprieved on a legal technicality and pardoned in February 1793. Three days later, aboard , Millward, Burkitt and Ellison were hanged from theyardarms

A yard is a spar on a mast from which sails are set. It may be constructed of timber or steel or from more modern materials such as aluminium or carbon fibre. Although some types of fore and aft rigs have yards, the term is usually used to de ...

. Dening calls them "a humble remnant on which to wreak vengeance".Dening, pp. 37–42. There was some unease expressed in the press, a suspicion that "money had bought the lives of some, and others fell sacrifice to their poverty." A report that Heywood was heir to a large fortune was unfounded; nevertheless, Dening asserts that "in the end it was class or relations or patronage that made the difference." Some accounts claim that the condemned trio continued to protest their innocence until the last moment,Alexander, pp. 300–02. while others speak of their "manly firmness that ... was the admiration of all".

Aftermath

On the specific recommendation of Lord Hood, who had offered the young man his personal patronage, Heywood resumed his naval career as a midshipman aboard his uncle Thomas Pasley's ship .Tagart, pp. 164–71. In September 1793, he was summoned by Lord Howe, commander of theChannel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history th ...

, to serve on , the fleet's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

. Hough observes that a pardon, followed by promotion, for one of Bligh's chief targets was "a public rebuke to the absent captain, and everyone recognised it as such".Hough, p. 282. Although Bligh had departed on his second breadfruit expedition in August 1791 as a national hero, the court martial had revealed damaging evidence of his erratic and overbearing behaviour. The families of Heywood and Christian, noting the leniency that had acquitted four and pardoned three of the ten accused, began their own campaigns for vindication, and for revenge on Bligh. When Bligh returned in August 1793 he found that opinion had turned sharply against him. Lord Chatham, at the Admiralty, refused to receive his report or even see him—although Nathaniel Portlock

Nathaniel Portlock (c. 1748 – 12 September 1817) was a British ship's captain, maritime fur trader, and author.

He entered the Royal Navy in 1772 as an able seaman, serving in . In 1776 he joined as master's mate and served on the third Pac ...

, Bligh's lieutenant, was given a meeting. Bligh was then left unemployed, on half-pay, for 19 months before his next assignment.

Shortly after his release, Heywood had written to Edward Christian, Fletcher's older brother, that he would "endeavour to prove that your brother was not that vile wretch, void of all gratitude ... but, on the contrary, a most worthy character ... beloved by all (except one, whose ill report is his greatest praise)". This statement, published immediately after Heywood's pardon in a local Whitehaven newspaper as an open letter to Edward Christian, contradicted the respect Heywood had accorded Bligh in the courtroom, and, in turn, it led to the publication in late 1794 of Edward Christian's ''Appendix'' to the court martial proceedings. Presented as an account of the "real causes and circumstances of that Unhappy Transaction", the ''Appendix'' was said by the press to "palliate the behaviour of Christian and the Mutineers, and to criminate Captain Bligh". In the controversy that followed, Bligh's rebuttals could not silence doubts as to his own conduct, and his position was further undermined when William Peckover, a Bligh loyalist, confirmed that the allegations in the ''Appendix'' were substantially accurate.

Subsequent career

Early stages

Heywood served on ''Queen Charlotte'' until March 1795, and was aboard her when the French fleet was defeated at

Heywood served on ''Queen Charlotte'' until March 1795, and was aboard her when the French fleet was defeated at Ushant

Ushant (; , ; , ) is a French island at the southwestern end of the English Channel which marks the westernmost point of metropolitan France. It belongs to Brittany and in medieval times, Léon. In lower tiers of government, it is a commune in t ...

on 1 June 1794, the occasion known as the "Glorious First of June

The Glorious First of June, also known as the Fourth Battle of Ushant, (known in France as the or ) was fought on 1 June 1794 between the British and French navies during the War of the First Coalition. It was the first and largest fleet a ...

".Alexander, pp. 389–92. In August 1794 he was promoted acting lieutenant. In March 1795, doubts about his eligibility as a convicted mutineer for further promotion were set aside and his advancement to full lieutenant's rank was approved, despite his lacking the stated minimum of six years' service at sea. Among those who supported the promotion was Captain Hugh Cloberry Christian, a relative of Fletcher Christian.

In January 1796, Heywood was appointed third lieutenant to and sailed with her to the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

. He was to remain in this station for nine years. By the end of 1796 he was ''Fox's'' first lieutenant, and remained so until mid-1798 when he transferred to . On 17 May 1799, Heywood was given his first command, , a brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the l ...

-of-war. In August 1800, Heywood was appointed commander of a bomb ship, the ''Vulcan'', in which he visited Coupang where he had been held prisoner eight years earlier. At this time he began the hydrographic work that would mark the remainder of his naval career.

Hydrographer

In 1803, after a succession of commands, Heywood was promoted topost-captain

Post-captain or post captain is an obsolete alternative form of the rank of captain in the Royal Navy. The term "post-captain" was descriptive only; it was never used as a title in the form "Post-Captain John Smith".

The term served to dis ...

. In command of , Heywood conducted a series of surveys of the eastern coasts of Ceylon and India, areas that had not been studied previously, and produced what Caroline Alexander describes as "beautifully drafted charts". In later years he was to produce similar charts for the north coast of Morocco, the River Plate area of South America, parts of the coasts of Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

and north-west Australia, and other channels and coastlines. His skill in this area may well have developed from Bligh's tutelage in the earlier stages of the ''Bounty'' voyage. Bligh, an accomplished draughtsman, had written of Christian and Heywood: "These two had been objects of my particular regard and attention, and I had taken great pains to instruct them." James Horsburgh, who was hydrographer to the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

, wrote that Heywood's work had "essentially contributed to making my Sailing Directory for the Indian navigation much more perfect than it would otherwise have been." The extent of Heywood's professional reputation was demonstrated when the position of Admiralty Hydrographer was offered to him in 1818, after he had retired from the sea. He declined, and the appointment went to Francis Beaufort

Sir Francis Beaufort ( ; 27 May 1774 – 17 December 1857) was an Irish hydrographer and naval officer who created the Beaufort cipher and the Beaufort scale.

Early life

Francis Beaufort was descended from French Protestant Hugu ...

on Heywood's recommendation.

Captain Heywood took command of HMS ''Dedaigneuse'' in April 1803 in the East Indies. On 14 December she captured the two (or four-gun) French privateer ''Espiegle''. Because of his poor health and the death of his elder brother, Captain Heywood resigned his command on 24 January 1805. He then returned to the United Kingdom as a passenger on the East Indiaman

East Indiamen were merchant ships that operated under charter or licence for European trading companies which traded with the East Indies between the 17th and 19th centuries. The term was commonly used to refer to vessels belonging to the Bri ...

.

Later service

After a brief period ashore in 1805–06 Heywood was appointedflag captain

In the Royal Navy, a flag captain was the captain of an admiral's flagship. During the 18th and 19th centuries, this ship might also have a " captain of the fleet", who would be ranked between the admiral and the "flag captain" as the ship's "Firs ...

to Rear-Admiral Sir George Murray, aboard . In March 1802 Murray's squadron was employed in the transportation of troops from the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

to South America, in support of a failed British attempt to capture Buenos Aires from the Spanish, who were allied to the French during the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. ''Polyphemus'' remained in the River Plate area, carrying out surveying and merchant vessel protection duties. 1808 saw Heywood back in England, in command of , which in the following year was part of a squadron that attacked and destroyed three French frigates in the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay ( ) is a gulf of the northeast Atlantic Ocean located south of the Celtic Sea. It lies along the western coast of France from Point Penmarc'h to the Spanish border, and along the northern coast of Spain, extending westward ...

, an action for which he received the Admiralty's thanks. After taking command of HMS ''Nereus'' in May 1809, Heywood served briefly in the Mediterranean under Admiral Lord Collingwood; after Collingwood's death in March 1810 Heywood brought his commander's body back to England. He then took ''Nereus'' to South America where he remained for three years, earning the gratitude of the British merchants in that region for his work in protecting trade routes. Heywood's last command was , in which he acted as escort to King Louis XVIII on the latter's return to France in May 1814. He remained with ''Montagu'' for the rest of his naval service.

Caroline Alexander suggests that throughout his later career Heywood suffered a sense of guilt over his pardon,Alexander, pp. 397–98. knowing that he had "perjured himself" in saying that he was kept below and therefore prevented from joining Bligh. She believes that Pasley and Graham may have bribed William Cole to testify that Heywood had been held against his will, echoing Thomas Bond, Bligh's nephew, who had asserted in 1792 that "Heywood's friends have bribed through thick and thin to save him". John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

, the last survivor of Christian's ''Bounty'' party that sailed to Pitcairn Island, was discovered in 1808. In 1825, interviewed by Captain Edward Belcher, Adams maintained that Heywood was on the gangway, not below, and "might have gone n the open boatif he pleased."

Retirement and death

On 16 July 1816, ''Montagu'' was paid off in Chatham and Heywood finally retired from the sea. Two weeks later he married Frances Joliffe, a widow whom he had met ten years earlier, and settled with her at

On 16 July 1816, ''Montagu'' was paid off in Chatham and Heywood finally retired from the sea. Two weeks later he married Frances Joliffe, a widow whom he had met ten years earlier, and settled with her at Highgate

Highgate is a suburban area of N postcode area, north London in the London Borough of Camden, London Boroughs of Camden, London Borough of Islington, Islington and London Borough of Haringey, Haringey. The area is at the north-eastern corner ...

, near London. The couple had no children but, apart from his daughter in Tahiti, there is a suggestion in a will which he signed in 1810 that Heywood had also fathered a British child—the will makes provision for one Mary Gray, "an infant under my care and protection".

In May 1818, Heywood declined command of the Canadian Lakes with the rank of commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (India), in India

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ' ...

. As he had become content with shore life, he said he would only accept another appointment in the event of war. In retirement Heywood published his dictionary of the Tahitian language, wrote papers relating to his profession, and corresponded widely. He enjoyed a circle of acquaintances which included the writer Charles Lamb

Charles Lamb (10 February 1775 – 27 December 1834) was an English essayist, poet, and antiquarian, best known for his '' Essays of Elia'' and for the children's book '' Tales from Shakespeare'', co-authored with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764� ...

, and was a particular friend of the hydrographer Francis Beaufort. He destroyed much of his writing shortly before his death, but a document from 1829 survives, in which he expresses his views on the unfitness for self-government of Greeks, Turks, Spaniards and Portuguese, the iniquities of the Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

and Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

churches, and the doubtful benefits of Catholic emancipation in Ireland. Of strong religious convictions, Heywood was increasingly interested in spiritual matters during the last years of his life. His health began to fail in 1828, and he died after suffering a stroke, aged 58, in February 1831. He was interred in the vault of Highgate School

Highgate School, formally Sir Roger Cholmeley's School at Highgate, is a co-educational, fee-charging, private day school, founded in 1565 in Highgate, London, England. It educates over 1,400 pupils in three sections – Highgate Pre-Preparato ...

chapel, where a memorial plaque was dedicated on 8 December 2008, and is also memorialised on the grave of his widow Frances on the west side of Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in North London, England, designed by architect Stephen Geary. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East sides. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for so ...

.

Nessy Heywood had died on 25 August 1793, less than a year after Heywood's pardon. Heywood's Bounty adversaries John Hallett and Thomas Hayward both died at sea within three years of the court martial; William Bligh served in the battles of Camperdown and Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

before, in 1806, he was appointed Governor of New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

. He returned to London in 1810 having suffered a further rebellion

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

by local army officers who opposed Bligh's attempts to reform local practices, as well as his rule by ''fiat''; Bligh was again court-martialed and acquitted. On his retirement he was promoted to rear admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

; he died in 1817. Likewise his ''Pandora'' adversaries Edward Edwards died in 1816 and Lt John Larkin died in 1830. William Muspratt died in Royal Navy service in 1797 as did James Morrison in 1807. Sir John Barrow

Sir John Barrow, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1764 – 23 November 1848) was an English geographer, linguist, writer and civil servant best known for serving as the Second Secretary to the Admiralty from 1804 until 1845.

Early life

Barrow was b ...

's book published in 1831, instigated the legend that Fletcher Christian had not died on Pitcairn, but had somehow returned to England and been recognised by Heywood in Plymouth, around 1808–1809. It is generally accepted that Christian, who had taken the ''Bounty'' to Pitcairn Island and founded a colony there with a group of hard core mutineers and conscripted Tahitians, was killed in 1793 during a feud. Christian's last recorded words, supposedly, were "Oh, dear!"Hough, p. 257.

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Related reading

* * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Heywood, Peter 19th-century Royal Navy personnel 1772 births 1831 deaths Royal Navy captains HMS Bounty mutineers 18th-century Manx people 19th-century Manx people Manx prisoners sentenced to death People educated at St Bees School Prisoners sentenced to death by the British military Recipients of British royal pardons Royal Navy officers who were court-martialled Royal Navy personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars