Personality cultism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an idealized and heroic image of a admirable leader, often through unquestioning

Throughout human history, monarchs and other

Throughout human history, monarchs and other

Jan Plamper argues while

Jan Plamper argues while

Mao Zedong's cult of personality was a prominent part of

Mao Zedong's cult of personality was a prominent part of

Russian President

Russian President

In December 1929, Stalin celebrated his 50th birthday, which featured prominently in the

In December 1929, Stalin celebrated his 50th birthday, which featured prominently in the

'' ''Al-Abad'''' means "forever, infinite and immortality" and religious clerics use this term in relation to Divine Attributes. By designating Assad as "''Al-Abad''", Syrian Ba'ath Movement ideologically elevated Hafez al-Assad as its "Immortal", "god-like figure" who is supposed to represent the state as well as the Syrian nation itself. Another meaning of ''Al-Abad'' is "permanent", which is used in state propaganda to denote the perpetual ''status quo'' of an "eternal political order" created by Hafez al-Assad, who continues to live in Assadist ideology. The term's verbal form "''Abada''" means "to commit

''Country Reports on Human Rights Practices''. U.S. State Department. March 4, 2002.International Crisis Group. July 2003. ''Central Asia: Islam and the State.'' ICG Asia Report No. 59. Available on-line at http://www.crisisgroup.org/

Alt URL

* * * * * * * * * * *

Why Dictators Love Kitsch

by Eric Gibson, ''

flattery

Flattery, also called adulation or blandishment, is the act of giving excessive compliments, generally for the purpose of Ingratiation, ingratiating oneself with the subject. It is also used in pick-up lines when attempting to initiate sexual or ...

and praise. Historically, it has been developed through techniques such as the manipulation of the mass media, the dissemination of propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

, the staging of spectacle

In general, spectacle refers to an event that is memorable for the appearance it creates. Derived in Middle English from c. 1340 as "specially prepared or arranged display" it was borrowed from Old French ''spectacle'', itself a reflection of the ...

s, the manipulation of the arts

The arts or creative arts are a vast range of human practices involving creative expression, storytelling, and cultural participation. The arts encompass diverse and plural modes of thought, deeds, and existence in an extensive range of m ...

, the instilling of patriotism, and government-organized demonstrations and rallies. A cult

Cults are social groups which have unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals. Extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or goal is another characteristic often ascribed to cults. The term ...

of personality is similar to apotheosis

Apotheosis (, ), also called divinization or deification (), is the glorification of a subject to divine levels and, commonly, the treatment of a human being, any other living thing, or an abstract idea in the likeness of a deity.

The origina ...

, except that it is established through the use of modern social engineering techniques, it is usually established by the state or the party in one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

s and dominant-party states. Cults of personality often accompany the leaders of totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

or authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

governments. They can also be seen in some monarchies

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

, theocracies, failed democracies, and even in liberal democracies

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal democracy are: ...

.

Background

Throughout human history, monarchs and other

Throughout human history, monarchs and other heads of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "

were frequently treated with enormous reverence and they were also thought to be endowed with super-human qualities. Through the principle of the divine right of kings, notably in medieval Europe, rulers were said to hold office by the will of God or the will of the gods. he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

, Imperial Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

, the Inca

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The History of the Incas, Inca ...

, the Aztecs

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the ...

, Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

, Siam (now Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

), and the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

are especially noted for their redefinition of monarchs as "god-kings". Furthermore, the Imperial cult of ancient Rome

The Roman imperial cult () identified Roman emperor, emperors and some members of their families with the Divine right of kings, divinely sanctioned authority (''auctoritas'') of the Roman State. Its framework was based on Roman and Greek preced ...

identified emperors

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/ grand empress dowager), or a woman who rule ...

and some members of their families with the divinely sanctioned authority (auctoritas

is a Latin word that is the origin of the English word "authority". While historically its use in English was restricted to discussions of the political history of Rome, the beginning of Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenological philosophy ...

) of the Roman State

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman civilisation from the founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingd ...

.

The spread of democratic and secular ideas in Europe and North America in the 18th and 19th centuries made it increasingly difficult for monarchs to preserve this aura, though Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

, and Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

appreciated its perpetuation in their ''carte-de-visite

The ''carte de visite'' (, English: ' visiting card', abbr. 'CdV', pl. ''cartes de visite'') was a format of small photograph which was patented in Paris by photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri in 1854, although first used by Louis Dod ...

'' portraits which proliferated, circulated and were collected in the 19th century.

The subsequent development of mass media, such as radio, enabled political leaders to project a positive image of themselves onto the masses as never before. It was from these circumstances in the 20th century that the most notorious personality cults arose. Frequently, these cults are a form of political religion

A secular religion is a communal belief system that often rejects or neglects the metaphysical aspects of the supernatural, commonly associated with traditional religion, instead placing typical religious qualities in earthly, or material, entitie ...

.

The advent of the Internet

The Internet (or internet) is the Global network, global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a internetworking, network of networks ...

and the World Wide Web

The World Wide Web (WWW or simply the Web) is an information system that enables Content (media), content sharing over the Internet through user-friendly ways meant to appeal to users beyond Information technology, IT specialists and hobbyis ...

in the 21st century has renewed the personality cult phenomenon. Disinformation

Disinformation is misleading content deliberately spread to deceive people, or to secure economic or political gain and which may cause public harm. Disinformation is an orchestrated adversarial activity in which actors employ strategic dece ...

via social media platforms and the twenty-four hour news cycle has enabled the widespread dissemination and acceptance of deceptive information and propaganda. As a result, personality cults have grown and remained popular in many places, corresponding with a marked rise in authoritarian government across the world.

The term "cult of personality" likely appeared in English around 1800–1850, along with the French and German versions of the term. It initially had no political connotations, but was instead closely related to the Romanticist "cult of genius". The first known political use of the phrase appeared in a letter from Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

to German political worker Wilhelm Blos dated to November 10, 1877:

Characteristics

There are various views about what constitutes a cult of personality in aleader

Leadership, is defined as the ability of an individual, group, or organization to "", influence, or guide other individuals, teams, or organizations.

"Leadership" is a contested term. Specialist literature debates various viewpoints on the co ...

. Historian Jan Plamper wrote that modern-day personality cults display five characteristics that set them apart from "their predecessors": The cults are secular and "anchored in popular sovereignty"; their objects are all males; they target the entire population, not only the well-to-do or just the ruling class; they use mass media; they exist where the mass media can be controlled enough to inhibit the introduction of "rival cults".

In his 2013 paper, "''What is character and why it really does matter''", Thomas A. Wright stated, "The cult of personality phenomenon refers to the idealized, even god-like, public image of an individual consciously shaped and molded through constant propaganda and media exposure. As a result, one is able to manipulate others based entirely on the influence of public personality ... the cult of personality perspective focuses on the often shallow, external images that many public figures cultivate to create an idealized and heroic image."

Adrian Teodor Popan defined a cult of personality as a "quantitatively exaggerated and qualitatively extravagant public demonstration of praise of the leader." He also identified three causal "necessary, but not sufficient, structural conditions, and a path-dependent chain of events which, together, lead to the cult formation: a particular combination of patrimonialism

Patrimonialism is a form of governance in which the ruler governs on the basis of personal loyalties which are derived from patron-client relations, personal allegiances, kin ties and combinations thereof. Patrimonialism is closely related to corr ...

and clientelism

Clientelism or client politics is the exchange of goods and services for political support, often involving an implicit or explicit ''quid-pro-quo''. It is closely related to patronage politics and vote buying.

Clientelism involves an asymmetri ...

, lack of dissidence, and systematic falsification pervading the society's culture."

One underlying characteristic, as explained by John Pittman, is the nature of the cult of personalities to be a patriarch. The idea of the cult of personalities that coincides with the Marxist movements gains popular footing among the men in power with the idea that they would be the "fathers of the people". By the end of the 1920s, the male features of the cults became more extreme. Pittman identifies that these features became roles including the "formal role for a ale

Ale is a style of beer, brewed using a warm fermentation method. In medieval England, the term referred to a drink brewed without hops.

As with most beers, ale typically has a bittering agent to balance the malt and act as a preservative. Ale ...

'great leader' as a cultural focus of the apparatus of the regime: reliance on top-down 'administrative measures': and a pyramidal structure of authority" which was created by a single ideal.

Role of mass media

The twentieth century brought technological advancements that made it possible for regimes to package propaganda in the form of radio broadcasts,film

A film, also known as a movie or motion picture, is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, emotions, or atmosphere through the use of moving images that are generally, sinc ...

s, and later content on the internet.

Writing in 2013, Thomas A. Wright observed that " is becoming evident that the charisma

() is a personal quality of magnetic charm, persuasion, or appeal.

In the fields of sociology and political science, psychology, and management, the term ''charismatic'' describes a type of leadership.

In Christian theology, the term ''chari ...

tic leader, especially in politics, has increasingly become the product of media and self-exposure." Focusing on the media in the United States, Robert N. Bellah added, "It is hard to determine the extent to which the media reflect the cult of personality in American politics and to what extent they have created it. Surely they did not create it all alone, but just as surely they have contributed to it. In any case, American politics is dominated by the personalities of political leaders to an extent rare in the modern world ... in the personalized politics of recent years the 'charisma' of the leader may be almost entirely a product of media exposure."

Purpose

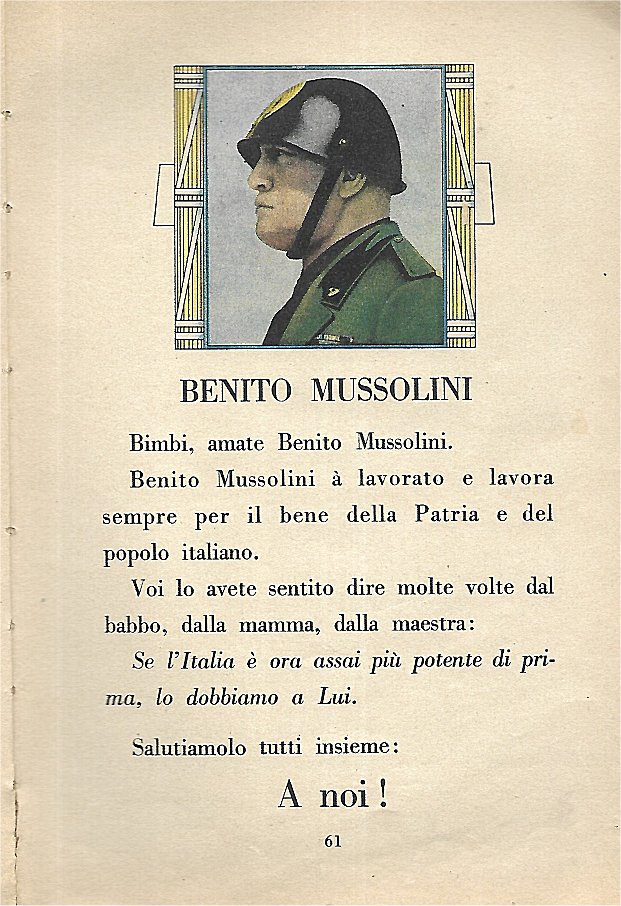

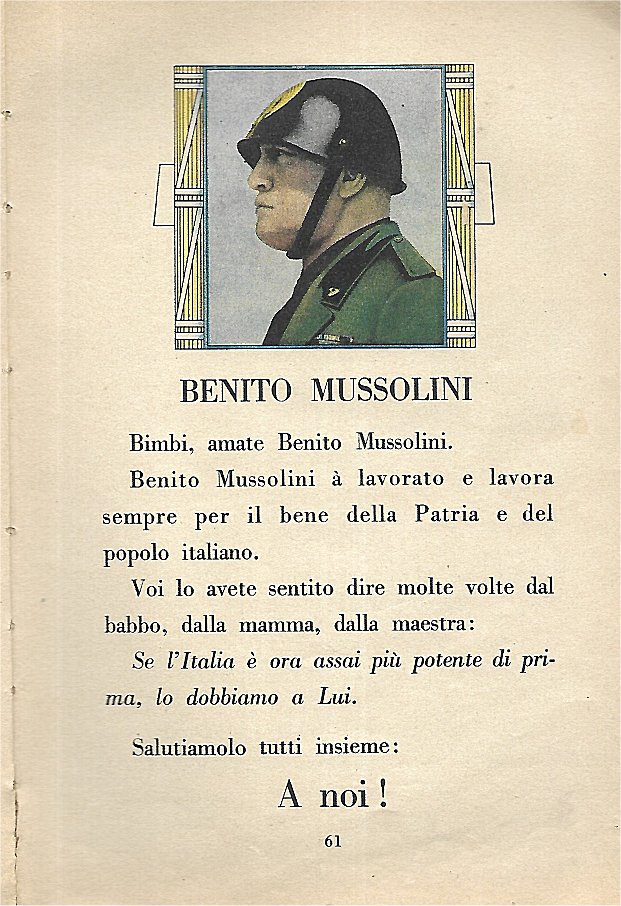

Jan Plamper argues while

Jan Plamper argues while Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

made some innovations in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, it was Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

in Italy in the 1920s who originated the model of dictator-as-cult-figure that was emulated by Hitler, Stalin and the others, using the propaganda powers of a totalitarian state

Totalitarianism is a political system and a Government#Forms, form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely contr ...

.

Pierre du Bois de Dunilac argues that the Stalin cult was elaborately constructed to legitimize his rule. Many deliberate distortions and falsehoods were used. The Kremlin

The Moscow Kremlin (also the Kremlin) is a fortified complex in Moscow, Russia. Located in the centre of the country's capital city, the Moscow Kremlin (fortification), Kremlin comprises five palaces, four cathedrals, and the enclosing Mosco ...

refused access to archival records that might reveal the truth, and key documents were destroyed. Photographs were altered and documents were invented. People who knew Stalin were forced to provide "official" accounts to meet the ideological demands of the cult, especially as Stalin himself presented it in 1938 in '' Short Course on the History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)'', which became the official history.

Historian David L. Hoffmann states "The Stalin cult was a central element of Stalinism

Stalinism (, ) is the Totalitarianism, totalitarian means of governing and Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953), 1927 to 1953 by dictator Jose ...

, and as such it was one of the most salient features of Soviet rule ... Many scholars of Stalinism cite the cult as integral to Stalin's power or as evidence of Stalin's megalomania."

In Latin America, Cas Mudde

Cas Mudde (born 3 June 1967) is a Dutch political science, political scientist who focuses on Extremism, political extremism and populism in Europe and the United States. His research includes the areas of political parties, extremism, democracy, ...

and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser link the "cult of the leader" to the concept of the ''caudillo

A ''caudillo'' ( , ; , from Latin language, Latin , diminutive of ''caput'' "head") is a type of Personalist dictatorship, personalist leader wielding military and political power. There is no precise English translation for the term, though it ...

'', a strong leader "who exercises a power that is independent of any office and free of any constraint." These populist

Populism is a contested concept used to refer to a variety of political stances that emphasize the idea of the " common people" and often position this group in opposition to a perceived elite. It is frequently associated with anti-establis ...

strongmen are portrayed as "masculine and potentially violent" and enhance their authority through the use of the cult of personality. Mudde and Kaltwasser trace the linkage back to Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine military officer and Statesman (politician), statesman who served as the History of Argentina (1946-1955), 29th president of Argentina from 1946 to Revolución Libertad ...

of Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

.

States and systems with personality cults

Argentina

Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine military officer and Statesman (politician), statesman who served as the History of Argentina (1946-1955), 29th president of Argentina from 1946 to Revolución Libertad ...

, who was elected three times as President of Argentina

The president of Argentina, officially known as the president of the Argentine Nation, is both head of state and head of government of Argentina. Under Constitution of Argentina, the national constitution, the president is also the Head of go ...

, and his second wife, Eva "Evita" Perón, were immensely popular among many of the Argentine people, and to this day they are still considered icons by the leading Justicialist Party

The Justicialist Party (, ; abbr. PJ) is a major political party in Argentina, and the largest branch within Peronism. Following the 2023 presidential election, it has been the largest party in the opposition against President Javier Milei.

Fo ...

. In contrast, academics and detractors often considered him a demagogue

A demagogue (; ; ), or rabble-rouser, is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, especially through oratory that whips up the passions of crowds, Appeal to emotion, appealing to emo ...

and a dictator. Perón sympathised with the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

when he was a colonel and Minister of War and even served as a diplomatic envoy to Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

. During his regime he kept close ties with Francoist Spain

Francoist Spain (), also known as the Francoist dictatorship (), or Nationalist Spain () was the period of Spanish history between 1936 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death i ...

. He ferociously persecuted dissents and potential political rivals, as political arrests were common during his first two terms. He eroded the republican principles of the country as a way to stay in power and forced statewide censorship on most media. Following his election, he built a personality cult around both himself and his wife so pervasive it is still a part of Argentina's current political life.

During Perón's regime, schools were forced to read Evita's biography '' La Razón de mi Vida'', union and government jobs were only given to those who could prove themselves to be a fervent Peronist, newspapers were censored and television and radio networks were nationalized, and only state media was allowed. He often showed contempt for any opponents, regularly characterizing them as traitors and agents of foreign powers. Those who did not fall in line or were perceived as a threat to Perón's political power were subject to losing their jobs, threats, violence and harassment. Perón dismissed over 20,000 university professors and faculty members from all major public education institutions. Universities were then intervened, the faculty was pressured to get in line and those who resisted were blacklisted

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list; if people are on a blacklist, then they are considere ...

, dismissed or exiled. Numerous prominent cultural and intellectual figures were imprisoned. Thousands of artists, scientists, writers and academics left the country, migrated to North America or Europe. Union leaders and political rivals were arrested and tortured for years and were only released after Perón was deposed.

Azerbaijan

Brazil

Bangladesh

Mujibism initially began as the political ideology ofSheikh Mujibur Rahman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (17 March 1920 – 15 August 1975), also known by the honorific Bangabandhu, was a Bangladeshi politician, revolutionary, statesman and activist who was the founding president of Bangladesh. As the leader of Bangl ...

, which was gradually converted into a cult of personality around him by his daughter Sheikh Hasina

Sheikh Hasina (''née'' Wazed; born 28 September 1947) is a Bangladeshi politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Bangladesh from June 1996 to July 2001 and again from January 2009 to August 2024. Premiership of Sheikh Hasina, Her ...

, leader of the Awami League

The Awami League, officially known as Bangladesh Awami League, is a major List of political parties in Bangladesh, political party in Bangladesh. The oldest existing political party in the country, the party played the leading role in achievin ...

, the party which under the leadership of Mujib, led Bangladesh's secession from Pakistan. After being pushed to the sidelines by 2 successive military dictators Ziaur Rehman (who founded the Bangladesh Nationalist Party

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (), popularly abbreviated as BNP (), is a major List of political parties in Bangladesh, political party in Bangladesh. It was founded on 1 September 1978 by President of Bangladesh, President Ziaur Rahman, wit ...

) & Hussain Muhammad Ershad

Hussain Muhammad Ershad (1 February 1930 – 14 July 2019) was a Bangladeshi military officer, dictator and politician who served as President of Bangladesh, the president of Bangladesh from 1982 to 1990.

He seized power as a result of a 1982 ...

(who founded the Bangladesh National Party), Mujib came back to dominate public consciousness from 2008

2008 was designated as:

*International Year of Languages

*International Year of Planet Earth

*International Year of the Potato

*International Year of Sanitation

The Great Recession, a worldwide recession which began in 2007, continued throu ...

under the Awami League government led by Hasina. Hasina has been criticised for overemphasising the role of her father & the Awami League in securing Bangladeshi independence at the cost of sidelining other prominent figures & political parties of the time. Hasina had amended the constitution to make the presence of Mujib's portrait mandatory in every school, government office & diplomatic missions of the country & made it illegal to criticise Mujib, his ideals & his deeds, especially the one-party BAKSAL regime (1972–75) headed by him, through writing, speech or electronic media. Many events commemorating the birth-centenary of ''Bangabandhu'' ('Friend of Bengal' in Bengali, the honorific unofficial title given to Mujib in his lifetime) were launched by the Hasina administration, including an official biopic

A biographical film or biopic () is a film that dramatizes the life of an actual person or group of people. Such films show the life of a historical person and the central character's real name is used. They differ from docudrama films and histo ...

in collaboration with the Indian government. The Hasina government converted Mujib's residence in the capital city of Dhaka

Dhaka ( or ; , ), List of renamed places in Bangladesh, formerly known as Dacca, is the capital city, capital and list of cities and towns in Bangladesh, largest city of Bangladesh. It is one of the list of largest cities, largest and list o ...

, where he & his family was assassinated by mutinous military personnel in 1975, into a memorial museum. Hasina designated the day of Mujib's assassination as the National Day of Mourning

A national day of mourning is a day, or one of several days, marked by mourning and memorial activities observed among the majority of a country's populace. They are designated by the national government. Such days include those marking the deat ...

. The Hasina government also made the birthdays of Mujib, his wife Sheikh Fazilatunessa, eldest son Sheikh Kamal & youngest son Sheikh Russel as official government holidays, alongside March 7 (on that day in 1971, Mujib declared Bangladesh's secession at a speech in Dhaka). Under Hasina's rule, the country was dotted with numerous statues of Mujib alongside several roads & prominent institutions named after him. Critics state that Hasina utilises the personality cult around her father to justify her own authoritarianism, crackdown on political dissent & democratic backsliding

Democratic backsliding or autocratization is a process of regime change toward autocracy in which the exercise of political power becomes more arbitrary and repressive. The process typically restricts the space for public contest and politi ...

of the country. Following the violent overthrow of Sheikh Hasina in 2024, the cult of personality around Mujib is being systematically dismantled.

China

Mao Zedong's cult of personality was a prominent part of

Mao Zedong's cult of personality was a prominent part of Chairman

The chair, also chairman, chairwoman, or chairperson, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the gro ...

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

's rule over the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

from his rise in 1949 until his death in 1976. Mass media

Mass media include the diverse arrays of media that reach a large audience via mass communication.

Broadcast media transmit information electronically via media such as films, radio, recorded music, or television. Digital media comprises b ...

, propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

and a series of other techniques were used by the state to elevate Mao Zedong's status to that of an infallible heroic leader, who could stand up against The West

West is a cardinal direction or compass point.

West or The West may also refer to:

Geography and locations

Global context

* The Western world

* Western culture and Western civilization in general

* The Western Bloc, countries allied with NAT ...

, and guide China to become a beacon of Communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

. Mao himself, however, publicly criticized the personality cult which was formed around him.

During the period of the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a Social movement, sociopolitical movement in the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). It was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 and lasted until his de ...

, Mao's personality cult soared to an unprecedented height. Mao's face was firmly established on the front page of ''People's Daily

The ''People's Daily'' ( zh, s=人民日报, p=Rénmín Rìbào) is the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It provides direct information on the policies and viewpoints of the CCP in multiple lan ...

'', where a column of his quotes was also printed every day. Mao's Selected Works were later printed in even greater circulation; the number of his portraits (1.2 billion) was more than the inhabitants in China. And soon Chairman Mao badge

Chairman Mao badge () is the name given to a type of Badge, pin badge displaying an image of Mao Zedong that was ubiquitous in the People's Republic of China during the active phase of the Cultural Revolution, from 1966 to 1971. The term is also ...

s began to appear; in total, about 4.8 billion were manufactured. Every Chinese citizen was presented with the ''Little Red Book

''Quotations from Chairman Mao'' ( zh, s=毛主席语录, t=毛主席語錄, p=Máo Zhǔxí Yǔlù, commonly known as the "红宝书" zh, p=hóng bǎo shū during the Cultural Revolution), colloquially referred to in the English-speaking world ...

'' – a selection of quotes from Mao. It was prescribed to be carried everywhere and displayed at all public events, and citizens were expected to quote the contents of the book daily. Mao himself believed that the situation had gone out of hand, and in a conversation with Edgar Snow

Edgar Parks Snow (July 19, 1905 – February 15, 1972) was an American journalist known for his books and articles on communism in China and the Chinese Communist Revolution. He was the first Western journalist to give an account of the history of ...

in 1970, he denounced the titles of "Great Leader, Great Supreme Commander, Great Helmsman" and insisted on only being called "teacher". Admiration for Mao Zedong has remained widespread in China in spite of somewhat general knowledge of his actions. In December 2013, a ''Global Times

The ''Global Times'' is a daily Chinese Tabloid (newspaper format), tabloid under the auspices of the Chinese Communist Party's flagship newspaper, the ''People's Daily'', commenting on international issues from a Chinese nationalistic pers ...

'' poll revealed that over 85% of Chinese viewed Mao's achievements as outweighing his mistakes.

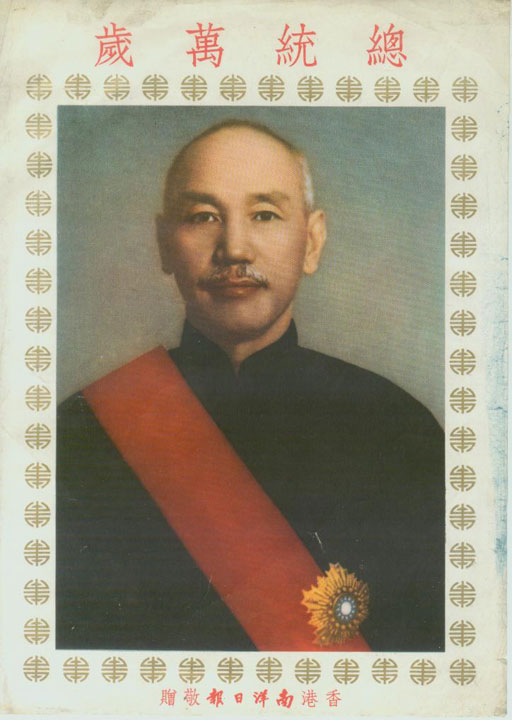

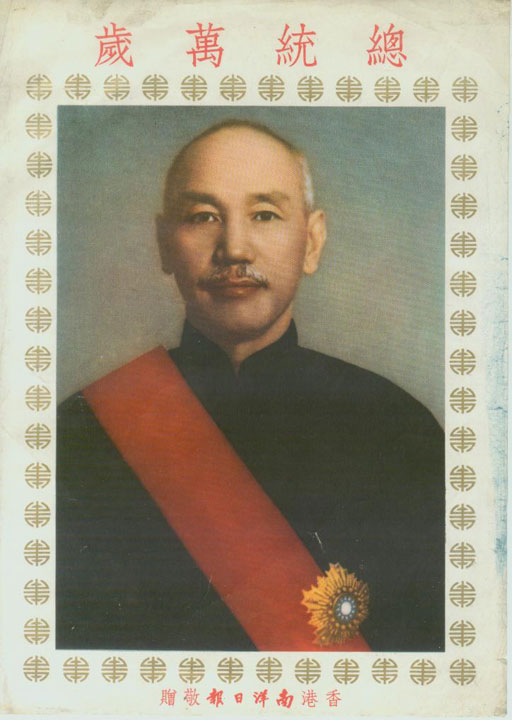

Chiang Kai-shek had a cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

. His portraits were commonly displayed in private homes and they were also commonly displayed in public on the streets. When the Muslim general and warlord Ma Lin was interviewed, he was described as having "high admiration for and unwavering loyalty to Chiang Kai-shek".

After the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

and others launched the "Boluan Fanzheng

''Boluan Fanzheng'' () refers to a period of significant sociopolitical reforms starting with the accession of Deng Xiaoping to the paramount leader of China, paramount leadership in China, replacing Hua Guofeng, who had been appointed as Mao Z ...

" program which invalidated the Cultural Revolution and abandoned (and forbade) the use of a personality cult.

A cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

has been developing around Xi Jinping

Xi Jinping, pronounced (born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician who has been the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (China), chairman of the Central Military Commission ...

since he became General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

of the ruling Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

and the regime's paramount leader

Paramount leader () is an informal term for the most important Supreme leader, political figure in the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The paramount leader typically controls the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People's Liberatio ...

in 2012.

Dominican Republic

Longtime dictator of theDominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. It shares a Maritime boundary, maritime border with Puerto Rico to the east and ...

Rafael Trujillo

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina ( ; ; 24 October 1891 – 30 May 1961), nicknamed ''El Jefe'' (; "the boss"), was a Dominican military officer and dictator who ruled the Dominican Republic from August 1930 until Rafael Trujillo#Assassination, ...

(ruled 1930–1961) was the center of a large personality cult. The nation's capital city, its highest peak, and a province were renamed for him. Statues of "El Jefe" were mass-produced and erected across the country, and bridges and public buildings were named in his honor. Automobile license plates included slogans such as "¡Viva Trujillo!" and "Año Del Benefactor De La Patria" (Year of the Benefactor of the Nation). An electric sign was erected in Ciudad Trujillo so that "Dios y Trujillo" could be seen at night as well as in the day. Eventually, even churches were required to post the slogan "Dios en el cielo, Trujillo en la tierra" (God in Heaven, Trujillo on Earth). As time went on, the order of the phrases was reversed (Trujillo on Earth, God in Heaven).

Haiti

François Duvalier, also known as Papa Doc, was a Haitian politician who served as thepresident of Haiti

The president of Haiti (, ), officially called the president of the Republic of Haiti (, , ), is the head of state of Haiti. Executive power in Haiti is divided between the president and the government, which is headed by the prime minister of ...

from 1957 until his death in 1971. He was elected president in the 1957 general election on a populist

Populism is a contested concept used to refer to a variety of political stances that emphasize the idea of the " common people" and often position this group in opposition to a perceived elite. It is frequently associated with anti-establis ...

and black nationalist

Black nationalism is a nationalist movement which seeks representation for Black people as a distinct national identity, especially in racialized, colonial and postcolonial societies. Its earliest proponents saw it as a way to advocate for ...

platform. After thwarting a military coup d'état in 1958, his regime rapidly became more autocratic

Autocracy is a form of government in which absolute power is held by the head of state and Head of government, government, known as an autocrat. It includes some forms of monarchy and all forms of dictatorship, while it is contrasted with demo ...

and despotic. An undercover government death squad

A death squad is an armed group whose primary activity is carrying out extrajudicial killings, massacres, or enforced disappearances as part of political repression, genocide, ethnic cleansing, or revolutionary terror. Except in rare cases in w ...

, the Tonton Macoute

The Tonton Macoute () or simply the Macoute, was a Haitian paramilitary and secret police force created in 1959 by dictator François "Papa Doc" Duvalier. Haitians named this force after the Haitian mythological bogeyman, (" Uncle Gunnysa ...

(), indiscriminately tortured or killed Duvalier's opponents; the Tonton Macoute was thought to be so pervasive that Haitians became highly fearful of expressing any form of dissent, even in private. Duvalier further sought to solidify his rule by incorporating elements of Haitian mythology into a personality cult.

Italy

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

was portrayed as the embodiment of Italian Fascism

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

and as a result, he was keen to be seen as such. Mussolini was styled by other Italian fascists as Il Duce ("The Leader"). Since Mussolini was represented as an almost omniscient leader, a common saying in Italy during Mussolini's rule was "The Duce is always right" (Italian: ''Il Duce ha sempre ragione''). Mussolini became a unifying force in Italy in order for ordinary Italians to put their difference to one side with local officials. The personality cult surrounding Mussolini became a way for him to justify his personal rule and it acted as a way to enable social and political integration.

Mussolini's military service in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and survival of failed assassination attempts were used to convey a mysterious aura around him. Fascist propaganda stated that Mussolini's body had been pierced by shrapnel just like St. Sebastian had been pierced by arrows, the difference being that Mussolini had survived this ordeal. Mussolini was also compared to St. Francis of Assisi, who had, like Mussolini, "suffered and sacrificed himself for others".

The press were given instructions on what and what not to write about Mussolini. Mussolini himself authorized which photographs of him were allowed to be published and rejected any photographs which made him appear weak or less prominent than he wanted to be portrayed as in a particular group.

Italy's war against Ethiopia (1935–37) was portrayed in propaganda as a revival of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, with Mussolini as the first Roman emperor Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

. To improve his own image, as well as the image of Fascism in the Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

, Mussolini declared himself to be the "Protector of Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

" during an official visit to Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

in 1937.

India

During the days of the freedom struggle,Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

had a cult-like following amongst the people of India. Congress leaders like Chittaranjan Das

Chittaranjan Das (5 November 1870 – 16 June 1925), popularly called ''Deshbandhu'' (friend of the country), was a Bengali freedom fighter, political activist and lawyer during the Indian Independence Movement and the political guru of Indi ...

and Subhash Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose (23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945) was an Indian independence movement, Indian nationalist whose defiance of British raj, British authority in India made him a hero among many Indians, but his wartime alliances with ...

who opposed Gandhi's methods, found themselves sidelined within the party. The assassination of Gandhi in 1948 led to widespread violence against Marathi Brahmins by his followers. After Gandhi's death, his cult was eclipsed by another personality cult that had developed around India's first prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

. C Rajagopalachari criticized the personality cult surrounding Nehru, saying that there should be an opposition group within the Congress. Rajagopalachari later formed the economically right-wing Swatantra Party

The Swatantra Party was an Indian classical liberal political party that existed from 1959 to 1974. It was founded by C. Rajagopalachari in reaction to what he felt was the Jawaharlal Nehru-dominated Indian National Congress's increasingly so ...

in opposition to Nehru's socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

economic view. The expression ' Nehruvian consensus' reflects the dominance of Nehruvian ideals, a product of Nehru's personality cult and the associated statism, i.e. the overarching faith in the state and the leadership. However, Nehru himself actively discouraged the creation of a cult of personality around him. He wrote an essay titled 'Rashtrapati' in 1937 published in the '' Modern Review'' warning people about dictatorship and emphasizing the value of questioning leaders.

The Congress party has been accused of promoting a personality cult centered around Nehru, his daughter Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

and the Nehru-Gandhi family. Indira Gandhi has also been described as having a cult of personality during her administration. Following India's victory in the 1971 Indo-Pak war, Gandhi was hailed by many as a manifestation of the Hindu goddess Durga

Durga (, ) is a major Hindu goddess, worshipped as a principal aspect of the mother goddess Mahadevi. She is associated with protection, strength, motherhood, destruction, and wars.

Durga's legend centres around combating evils and demonic ...

. In that year, Gandhi nominated herself as a recipient for the Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ) is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest order", without distin ...

, the highest civilian award of the country. During the Emergency period the then Congress party president Devakanta Barooah, had remarked India is Indira, Indira is India''Rajiv Gandhi

Rajiv Gandhi (20 August 1944 – 21 May 1991) was an Indian statesman and pilot who served as the prime minister of India from 1984 to 1989. He took office after the Assassination of Indira Gandhi, assassination of his mother, then–prime ...

utilised her death to win the general elections shortly held after. His assassination while campaigning in the 1991 general elections also led to widespread public grief, which was utilised by the Congress to win the elections despite unfavorable circumstances.

Current Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi

Narendra Damodardas Modi (born 17 September 1950) is an Indian politician who has served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India since 2014. Modi was the chief minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014 and is the Member of Par ...

is often criticized for creating a personality cult around him. Despite some setbacks and criticism, Modi's charisma and popularity was a key factor that helped the Bharatiya Janata Party

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; , ) is a political party in India and one of the two major List of political parties in India, Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. BJP emerged out from Syama Prasad Mukherjee's ...

(BJP) return to power in the 2019 general elections. Shivraj Singh Chouhan, the chief minister of the country's second largest state, said in 2022, "He is superhuman and has traces of God in him." The Opposition often accused Modi for spreading propaganda using popular media such as movies, television and web series. Modi is often accused of having narcissist traits. In 2015, Modi wore a suit which has his name embroidered all over it in fine letters like a Hindu ''namavali'' (A sheet of cloth printed all over with the names of Hindu gods and goddesses usually worn by Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

priests

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, ...

during puja) while greeting US president Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

during his bilateral visit to India. This suit was auctioned that year, selling at a record amount of 43.1 million Indian rupees, thereby earning the Guinness World Records

''Guinness World Records'', known from its inception in 1955 until 1999 as ''The Guinness Book of Records'' and in previous United States editions as ''The Guinness Book of World Records'', is a British reference book published annually, list ...

for the most expensive suit. In 2019, a biographical film

A biographical film or biopic () is a film that dramatizes the life of an actual person or group of people. Such films show the life of a historical person and the central character's real name is used. They differ from Docudrama, docudrama films ...

of Modi was released, which was heavily criticized for its hagiographical nature. In 2021, Modi named the world's largest cricket stadium after himself. During the 2024 general elections, Modi tried to divinise himself in an interview, in which he stated that he viewed himself to be sent directly by God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

to serve a special purpose on Earth. BJP spokesperson Sambit Patra while campaigning in the Hindu holy city of Puri

Puri, also known as Jagannath Puri, () is a coastal city and a Nagar Palika, municipality in the state of Odisha in eastern India. It is the district headquarters of Puri district and is situated on the Bay of Bengal, south of the state ca ...

stated that even Jagannath

Jagannath (; formerly ) is a Hindu deity worshipped in regional Hindu traditions in India as part of a triad along with (Krishna's) brother Balabhadra, and sister, Subhadra.

Jagannath, within Odia Hinduism, is the supreme god, '' Purushot ...

(the form of the Hindu god Vishnu

Vishnu (; , , ), also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the Hindu deities, principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism, and the god of preservation ( ...

which is venerated there) worships Modi. The BJP is also stated to have created a cult of personality around Hindu Mahasabha

Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha (), simply known as Hindu Mahasabha, is a Hindu nationalism, Hindu nationalist political party in India.

Founded in 1915 by Madan Mohan Malviya, the Mahasabha functioned mainly as a pressure group advocating th ...

leader V. D. Savarkar and Gandhi's assassin Nathuram Godse

Nathuram Vinayak Godse (19 May 1910 – 15 November 1949) () was an Indian Hindu nationalist and political activist who was the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi. He shot Gandhi in the chest three times at point blank range at a multi-faith praye ...

to oppose the dominance of Gandhian philosophy

Gandhism is a body of ideas that describes the inspiration, vision, and the life work of Mohandas K. Gandhi. It is particularly associated with his contributions to the idea of nonviolent resistance, sometimes also called civil resistance.

The ...

in Indian society.

One study claims that India's political culture since the decline of the Congress' single-handed dominance over national politics from the 1990s onwards as a fallout of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and Mandal Commission protests has paved way for personality cults centered around leaders of the small regional parties, derived from hero-worship of sportspersons and film industry celebrities and the concept of ''bhakti

''Bhakti'' (; Pali: ''bhatti'') is a term common in Indian religions which means attachment, fondness for, devotion to, trust, homage, worship, piety, faith, or love.See Monier-Williams, ''Sanskrit Dictionary'', 1899. In Indian religions, it ...

'', which in turn has fostered nepotism

Nepotism is the act of granting an In-group favoritism, advantage, privilege, or position to Kinship, relatives in an occupation or field. These fields can include business, politics, academia, entertainment, sports, religion or health care. In ...

, cronyism and sycophancy. Among these leaders, Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

Chief Minister

A chief minister is an elected or appointed head of government of – in most instances – a sub-national entity, for instance an administrative subdivision or federal constituent entity. Examples include a state (and sometimes a union ter ...

J. Jayalalitha had one of the most extensive ones. She was widely referred by leaders and members of her party as ''Amma'' ('mother' in Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

People, culture and language

* Tamils, an ethno-linguistic group native to India, Sri Lanka, and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka

** Myanmar or Burmese Tamils, Tamil people of Ind ...

, also used to refer to Hindu goddesses) and would prostrate themselves before her. She would be regularly publicly applauded with Tamil titles like ''Makkalin Mudhalvar'' (people's chief minister), ''Puratchi Thalaivi'' (revolutionary female leader), ''Thanga Thalaivi'' (golden female leader) etc by her cadres. Her government provided various kinds of subsidised goods under the brand name of ''Amma''. Widespread violence broke out throughout the state when she was arrested on charges of corruption. A huge wave of public grief swept all over the state, with some even committing suicide, following her death in 2016. Another leader, Mayawati, was also known for attempting to foster a cult of personality during her tenure as the Chief Minister of India's most populous state by getting constructed large statues of herself and the elephant (which was the electoral symbol of her party) that were installed in public parks at the cost of government exchequer.

Historical personalities are also deified to the level of cult worship long after their lifetimes which is utilised by politicians to woo their followers for electoral purposes. Prominent examples are the cult of Shivaji

Shivaji I (Shivaji Shahaji Bhonsale, ; 19 February 1630 – 3 April 1680) was an Indian ruler and a member of the Bhonsle dynasty. Shivaji carved out his own independent kingdom from the Sultanate of Bijapur that formed the genesis of the ...

in Maharashtra

Maharashtra () is a state in the western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. It is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west, the Indian states of Karnataka and Goa to the south, Telangana to th ...

and the cult of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar among Dalit

Dalit ( from meaning "broken/scattered") is a term used for untouchables and outcasts, who represented the lowest stratum of the castes in the Indian subcontinent. They are also called Harijans. Dalits were excluded from the fourfold var ...

s.

Germany

Starting in the 1920s, during the early years of theNazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

, Nazi propaganda

Propaganda was a tool of the Nazi Party in Germany from its earliest days to the end of the regime in May 1945 at the end of World War II. As the party gained power, the scope and efficacy of its propaganda grew and permeated an increasing amou ...

began to depict the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

as a demagogue

A demagogue (; ; ), or rabble-rouser, is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, especially through oratory that whips up the passions of crowds, Appeal to emotion, appealing to emo ...

figure who was the almighty defender and savior of Germany. After the end of World War I (1918) and the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

(1919), the German people experienced turmoil under the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

, and, according to Nazi propaganda, only Hitler could save them and restore Germany's greatness, which in turn gave rise to the "Führer

( , spelled ''Fuehrer'' when the umlaut is unavailable) is a German word meaning "leader" or " guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with Adolf Hitler, the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. Hitler officially cal ...

-cult". During the five election campaigns in 1932, the Nazi newspaper ''Völkischer Beobachter

The ''Völkischer Beobachter'' (; "'' Völkisch'' Observer") was the newspaper of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) from 25 December 1920. It first appeared weekly, then daily from 8 February 1923. For twenty-four years it formed part of the official pub ...

'' portrayed Hitler as a man who had a mass movement united behind him, a man with one mission to solely save Germany as the 'Leader of the coming Germany'. The Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (, ), also called the Röhm purge or Operation Hummingbird (), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Adolf Hitler, urged on by Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler, ord ...

in 1934 – after which Hitler referred to himself as being single-handedly "responsible for the fate of the German people" – also helped to reinforce the myth that Hitler was the sole protector of the ''Volksgemeinschaft

''Volksgemeinschaft'' () is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community", Richard Grunberger, ''A Social History of the Third Reich'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 44. "national community", or "racial community" ...

'', the ethnic community of the German people.

Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and philologist who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief Propaganda in Nazi Germany, propagandist for the Nazi Party, and ...

cultivated an image of Hitler as a "heroic genius". The myth also gave rise to the saying and concept, "If only the Führer knew". Germans thought that problems which they ascribed to the Nazi hierarchy would not have occurred if Hitler had been aware of the situation; thus Nazi bigwigs were blamed, and Hitler escaped criticism.

British historian Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's foremost experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is ...

published his book '' The "Hitler Myth": Image and Reality in the Third Reich'' in 1987 and wrote:

During the early 1930s, the myth was given credence due to Hitler's perceived ability to revive the German economy during the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. However, Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as Reich Ministry of Armaments and War Production, Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of W ...

wrote that by 1939, the myth was under threat and the Nazis had to organize cheering crowds to turn up to events. Speer wrote:

The myth helped to unite the German people during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, especially against the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and the Western Allies

Western Allies was a political and geographic grouping among the Allied Powers of the Second World War. It primarily refers to the leading Anglo-American Allied powers, namely the United States and the United Kingdom, although the term has also be ...

. During Hitler's early victories against Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

the myth was at its peak, but when it became obvious to most Germans that the war was lost then the myth was exposed and Hitler's popularity declined.

A report is given in the little Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

n town of Markt Schellenberg on March 11, 1945:

North Korea

The cult of personality which surroundsNorth Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

's ruling family, the Kim family, has existed for decades and it can be found in many aspects of North Korean culture. Although not acknowledged by the North Korean government

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

, many defectors and Western visitors state there are often stiff penalties for those who criticize or do not show "proper" respect for the regime. The personality cult began soon after Kim Il Sung

Kim Il Sung (born Kim Song Ju; 15 April 1912 – 8 July 1994) was a North Korean politician and the founder of North Korea, which he led as its first Supreme Leader (North Korean title), supreme leader from North Korea#Founding, its establishm ...

took power in 1948, and was greatly expanded after his death in 1994.

The pervasiveness and the extreme nature of North Korea's personality cult surpasses those of Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

. The cult is also marked by the intensity of the people's feelings for and devotion to their leaders, and the key role played by a Confucianized ideology of familism both in maintaining the cult and thereby in sustaining the regime itself. The North Korean cult of personality is a large part of Juche

''Juche'', officially the ''Juche'' idea, is a component of Ideology of the Workers' Party of Korea#Kimilsungism–Kimjongilism, Kimilsungism–Kimjongilism, the state ideology of North Korea and the official ideology of the Workers' Party o ...

and totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public s ...

.

Yakov Novichenko, a Soviet military officer who saved Kim Il Sung's life on 1 May 1946, is reported to also have developed a cult of personality around 1984. He is considered the only non-Korean to have developed a cult of personality there.

Peru

Philippines

Nowadays both conservative and liberal groups have developed cult of personalities around their political frontman, most notably supporters ofLeni Robredo

Maria Leonor "Leni" Gerona Robredo (; Gerona; born April 23, 1965) is a Filipino lawyer and politician who served as the 14th vice president of the Philippines from 2016 to 2022. She is the mayor-elect of Naga, Camarines Sur, having won the ...

who are dubbed as '' 'kakampinks' '' or less commonly '' 'pinklawan' '', both a play on her affiliation with the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

and her branding of pink/magenta colors, Bongbong Marcos

Ferdinand "Bongbong" Romualdez Marcos Jr. (, , ; born September 13, 1957), commonly referred to by the initials BBM or PBBM, is a Filipino politician who has served as the 17th president of the Philippines since 2022. He is the second child ...

and his family, mostly surrounding his father's legacy, and Rodrigo Duterte

Rodrigo Roa Duterte (, ; born March 28, 1945) is a Filipino lawyer and politician who served as the 16th president of the Philippines from 2016 to 2022. He is the first Philippine president from Mindanao, and is the oldest person to assum ...

and his family dubbed '' ' Diehard Duterte Supporters' '', a play on the acronym of Rodrigo Duterte's Davao Death Squad

The Davao Death Squad (DDS) is a death squad group in Davao City, Philippines. The group is alleged to have conducted summary executions of street children and individuals suspected of petty crimes and drug dealing. It has been estimated that ...

.

Poland

Romania

Russia

Russian President

Russian President Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

has created a cult of personality for himself as an outdoorsy, sporty, tough guy public image, demonstrating his physical capabilities and taking part in unusual or dangerous acts, such as extreme sports and interaction with wild animals.

Soviet Union

The first cult of personality to take shape in the USSR was that ofVladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

. Up until the dissolution of the USSR

Dissolution may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Dissolution'', a 2002 novel by Richard Lee Byers in the War of the Spider Queen series

* Dissolution (Sansom novel), ''Dissolution'' (Sansom novel), by C. J. Sansom, 2003

* Dissolution (Binge no ...

in 1991, Lenin's portrait and quotes were a ubiquitous part of the culture. However, during his lifetime, Lenin vehemently denounced any effort to build a cult of personality, as (in his eyes) the cult of personality was antithetical to Marxism. Despite this, members of the Communist Party used Lenin's image as the all-knowing revolutionary who would liberate the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian or a . Marxist ph ...

. Lenin attempted to take action against this; however it was halted after Lenin was nearly assassinated in August 1918. His health would only further decline as he suffered numerous severe strokes, with the worst in May 1922 and March 1923. In this state Lenin would lose the ability to walk and speak. During this time the Bolshevik Party began to promote the accomplishments of Lenin as the basis for a cult of personality, using him as an image of morality and of revolutionary ideas.

After Vladimir Lenin's death in 1924 and the exile of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

in 1928, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

came to embody the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Once Lenin's cult of personality had grown, creating enough influence, Stalin integrated Lenin's ideals into his own cult. Unlike other cults of personalities, the Lenin and Stalin cults were not created to give the leaders power, they were created to give power and validation to the Communist Party. Stalin initially spoke out against the cult and other outrageous and false claims centered around him. However Stalin's attitude began to shift in favor of the cult in the 1930s, and he began to encourage it following the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

of 1936 to 1938. Seldom did Stalin object to state actions that furthered his cult of personality, however he did oppose some initiatives from Soviet propagandists. When Nikolai Yezhov

Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov ( rus, Николай Иванович Ежов, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ (j)ɪˈʐof; 1 May 1895 – 4 February 1940), also spelt Ezhov, was a Soviet Chekism, secret police official under Joseph Stalin who ...

proposed to rename Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

to , which translates as "gift of Stalin", Stalin objected. To merge the Lenin and Stalin cults together, Stalin changed aspects of Lenin's life in the public's eye in order to place himself in power. This kept the two cults in a line that showed that both Lenin and Stalin had the same ideas and that Stalin was the rightful successor of Lenin, leading the USSR in the fashion Lenin would have done.

In December 1929, Stalin celebrated his 50th birthday, which featured prominently in the

In December 1929, Stalin celebrated his 50th birthday, which featured prominently in the Soviet press

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...